Abstract

This study aims to investigate the ecological role of sponges as habitat formers on soft-bottom habitats of the mesophotic zone. As habitat formers, sponges significantly enhance benthic habitat complexity and establish associations with a plethora of organisms consequently augmenting local biodiversity. This role becomes particularly critical in areas subjected to intensive bottom trawling, where sponges often comprise a substantial portion of the discarded material. The examination of 114 massive sponge specimens, belonging to 10 sponge species, which were collected as bycatch from bottom trawls in the Aegean and Ionian ecoregions, revealed a total of over 4600 associated individuals of 78 invertebrate taxa, with crustaceans, mollusks, and polychaetes being the dominant groups. The composition of sponge-associated communities showed strong similarities to previously reported cases from shallow water hard substrates of the eastern Mediterranean, while displaying host-specific differences likely influenced by sponge morphology. Although depth did not significantly affect species richness, Shannon diversity, or evenness, a decrease in abundance of associated invertebrates was observed in deeper samples, suggesting a depth-related pattern that deserves further investigation. By forming stable substrate “islands” in otherwise unstable soft substrate environments, sponges play a vital role in structuring benthic communities. Their removal through bottom trawling not only results in the loss of the sponges themselves, but also disrupts the diverse communities they support. We suggest that sponge-associated fauna should be recognized as part of the discarded bycatch and emphasize the need for broader assessments of sponge-mediated biodiversity across similar Mediterranean habitats to support effective management and conservation strategies.

1. Introduction

The functional role of sponges (phylum: Porifera) in the marine environment is considered of great importance [1,2], as these organisms can significantly influence the composition of benthic communities [3,4]. Due to their complex morphology and ecological interactions, they have been characterized as “living hotels” [5,6], “ecosystem engineers” [7], and “habitat formers” [8]. These designations are based on their body structure, which provides habitat for a wide variety of associated taxa, from microorganisms to invertebrate and vertebrate animals, leading to diverse relationship types among host sponges and their associates. The complex three-dimensional structure of sponges—an intricate network of cavities and canals—provides suitable habitat for various macrobenthic species, which find protection, food, breeding space, and nursery areas [8], thus creating a community within a broader one. In some cases, the relationships are obligate, such as those of the Synalpheus shrimps which are exclusive symbionts of sponges [9].

Despite their well-documented ecological importance, sponge assemblages still remain understudied in areas subjected to fishing activity. Recent findings from trawlable soft-bottom habitats in the Aegean and Ionian ecoregions (Mediterranean Sea) revealed a remarkable diversity of sponge taxa [10], raising questions on their associated fauna. This associated fauna represents a form of “hidden biodiversity” that is removed from the mesophotic bottoms as incidental catch, augmenting the extent of fishing impact on these habitats.

Although sponge-associated communities in the eastern Mediterranean basin are well studied, research primarily focuses on shallow rocky bottoms [11,12,13,14,15,16] and on the hard substratum of submarine caves [5]. More recently, three publications appeared on the role of sponges as habitat formers in the Levantine Basin, two in the mesophotic zone of Israeli coasts [6,17] and one on the trawlable seafloors of Cyprus [18].

Recognizing this knowledge gap on the role of sponges in mesophotic soft-substrate habitats—particularly those impacted by bottom trawling—we collected sponges during field surveys with experimental and commercial bottom trawls in the Aegean and Ionian ecoregions, in the framework of three monitoring programs (mainly MEDITS Project). In this study, we explore the invertebrate diversity associated with selected sponge species, collected from soft-substrate, mesophotic habitats, most of which are exploited by bottom trawling. The following hypotheses were investigated: (a) sponges act as habitat formers in the soft bottoms of the mesophotic zone, hosting rich invertebrate communities; (b) different invertebrate communities inhabit different species of host sponges; and (c) depth influences the composition of the sponge-associated communities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

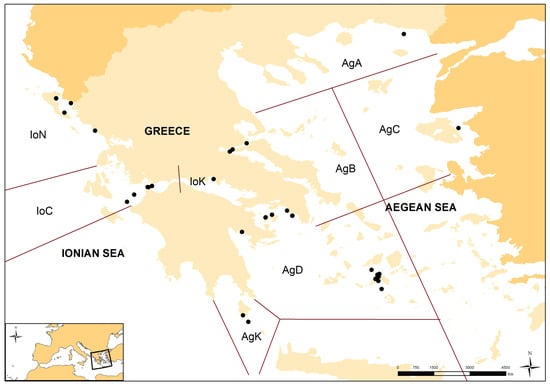

Field surveys were conducted using both experimental and commercial bottom trawls in the soft mesophotic bottoms of the Aegean Sea and the eastern Ionian Sea, at depths between 20 and 200 m (Figure 1). Sponge material was collected as part of fish-stock monitoring programs carried out between 2016 and 2018. The sampling scheme and methodology are described in detail in Stamouli et al. [10].

Figure 1.

Map of the sampling stations (black dots) from which the sponge samples were caught during bottom trawl surveys. Bottom left corner: the location of the study area (Aegean and Ionian Seas) in the Mediterranean Sea. AgA—North Aegean; AgB—Central–West Aegean; AgC—Central–East Aegean; AgD—South–West Aegean; AgK—the marine area around Kythira Isl.; IoN—North Ionian; IoC—Central Ionian; IoK—the Korinthiakos gulf.

2.2. Sampling and Sample Processing

Ten sponge species were selected for the study of their associated fauna: Aplysina aerophoba (Nardo, 1833), Dysidea avara (Schmidt, 1862), Fasciospongia cavernosa (Schmidt, 1862), (Linnaeus, 1767), Ircinia variabilis (Schmidt, 1862), Suberites domuncula (Olivi, 1792), Suberites ficus (Johnston, 1862), Spongia (Spongia) officinalis Linnaeus, 1759, Scalarispongia scalaris (Schmidt, 1862), and Sarcotragus foetidus Schmidt, 1862. These species were chosen among a total of 87 species found [10], based on their massive or tubular growth forms, characterized by a rich network of cavities and canals capable of supporting both infaunal and epifaunal organisms. In addition, most of these sponges have been documented previously as habitat formers in various marine environments, particularly on shallow rocky substrates (e.g., [12,13]). A total of 114 sponge specimens were collected from depths ranging between 20 and 200 m (Table 1). Of these, 73 specimens, representing nine species, were obtained from the 20–50 m depth zone, while 41 specimens representing eight sponge species were collected from the 50–200 m zone.

Table 1.

Sponge species examined and number of specimens collected per subarea and depth zone.

Immediately after trawl retrieval, sponge specimens were carefully isolated in plastic bags to minimize the loss of epibionts or endobionts, and were subsequently stored frozen. The recommended sampling practice to isolate sponges in bags prior to detachment from the substrate to prevent loss of associates [5,11] was not feasible in our case due to the sampling procedure employed. However, Goren et al. [6] demonstrated that no significant difference exists in the number and abundance of associated species between samples of the same sponge species collected with coverage before detachment and those isolated after transport to the vessel. Therefore, we consider that the data obtained with our sampling method can be used for analyses and comparisons, still with caution.

Before processing, sponges were kept out of the freezer to reach room temperature. Then they were wet weighted and volumetrically measured using the water displacement method [6,11,16]. Specifically, after being weighed, each sponge specimen was submerged individually in an open plastic container filled with water up to the overflow point; the water displaced by the immersion was collected in a graduated measuring cylinder and its volume was recorded.

Sponges were subsequently dissected into small pieces along their canals and cavities using a scalpel, to minimize damage of the associated organisms (Figure 2). During dissection, organisms larger than 1 mm were collected and preserved by higher taxonomic group in 70% ethanol. Additional organisms retrieved from the water used during sponge rinsing and water displacement procedures were also collected and preserved using the same method.

Figure 2.

Characteristic endobionts observed during removal from sponge specimens: (a) the shrimp Synalpheus gambarelloides (Nardo, 1847) in cavities of Fasciospongia cavernosa; (b) the crustaceans Pilumnus spinifer H. Milne Edwards, 1833 and Cymodoce truncata Leach, 1814 and a polychaete inhabiting cavities of Sarcotragus foetidus; (c) the ophiuroid Ophiothrix fragilis (Abildgaard in O.F. Müller, 1789) in cavities of Scalarispongia scalaris; and (d) the mollusk Hiatella arctica (Linnaeus, 1767) within cavities of Ircinia variabilis, (e) a polychaete in cavities of Ircinia variabilis, and (f) isopods inhabiting the internal cavity of the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus.

All the collected associated organisms were identified to the lowest possible taxonomic level. For each sponge specimen, the total abundance of associated individuals was recorded. To facilitate comparisons across sponge specimens of different size, the abundance of each associated taxon was standardized by calculating the number of individuals per liter of sponge volume. Taxonomic classification and nomenclature of associated fauna followed the World Register of Marine Species [19].

2.3. Data Analysis

To assess the composition of sponge-associated communities, we considered several community parameters. For each sponge specimen, we calculated the number of associated taxa (S), the abundance of associates per liter of sponge volume (A), the Shannon diversity index (H’), and the Pielou evenness index (J’). For each associated taxon we calculated: presence (P)—the number of sponge specimens in which the taxon occurred; frequency (F)—percentage presence of the taxa across all sponge specimens; abundance (As)—number of individuals per liter of sponge volume; and mean dominance (mDa)—the percentage of taxa abundance in relation to the total abundance of all associates.

To investigate differences in associated community composition among sponge species and depth zones, abundance data were log-transformed using the formula ((log x) + 1) to reduce the influence of dominant taxa. The transformed data were then used to construct a similarity matrix, comparing all possible pairs of samples, using the Bray–Curtis similarity index. Community patterns were visualized using Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP), performed in PRIMER v6 software.

Statistical differences in taxa richness, diversity, evenness, and abundance of associated fauna among sponge species were tested using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). To identify the key taxa contributing most to dissimilarities among sponge species, a Similarity Percentages (SIMPER) analysis was carried out. Additionally, the potential relationship between sponge volume and taxa richness, abundance, and diversity (expressed as Shannon index H’) was examined using the Spearman correlation coefficient (rho).

In order to compare the associated community composition across the same sponge species collected from different sampling subareas (Figure 1), PERMANOVA analysis was carried out for every sponge species separately. For the comparison of the associated community composition across depth zones, analysis was restricted to two sponge species, Aplysina aerophoba and Sarcotragus foetidus, for which at least five specimens were available from both the depth zones (20–50 m and 50–200 m).

3. Results

The volume of sponge specimens analyzed ranged from 8 to 7200 mL. The number of associated taxa varied among the different sponge specimens and ranged from 1 to 16. In 25.4% of the sponge specimens, only a single associated taxon was recorded, while 14.9% of the specimens hosted four taxa and 36% of the sponge specimens harbored more than five taxa each. A complete list of all sponge specimens examined along with information on depth of collection, wet weight, volume, number of associated taxa (S) and number of individuals (N) in each sample, is provided in Appendix A (Table A1).

3.1. Associated Macrofauna

A total of 4677 individuals of associated invertebrates were recorded, classified into 78 taxa (Table 2) and belonging to six higher taxonomic groups: Porifera, Crustacea, Mollusca, Polychaeta, Sipuncula, Echinodermata, and Ascidiacea.

Table 2.

Taxa associated with the studied sponge species. Aa: Aplysina aerophoba; Da: Dysidea avara; Fc: Fasciospongia cavernosa; Gc: Geodia cydonium; Iv: Ircinia variabilis; So: Spongia (Spongia) officinalis; Ss: Scalarispongia scalaris; Sfo: Sarcotragus foetidus; Sd: Suberites domuncula; and Sfi: Suberites ficus.

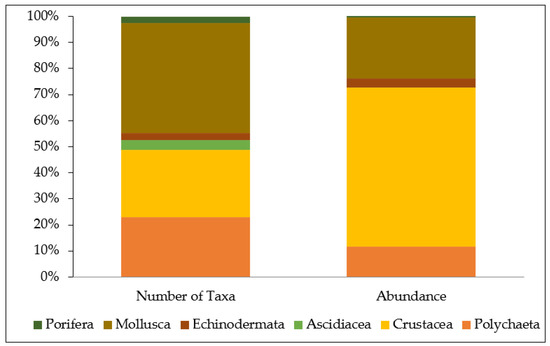

Mollusks represented the most taxa-rich group (Figure 3), accounting for 42.3% of the total taxa found (33 taxa), followed by crustaceans (25.6%, 20 taxa) and polychaetes (23.1%, 18 taxa). Ascidians accounted for 3.8% (3 taxa), while echinoderms and sponges contributed 2.6% (2 taxa) each to the total taxa pool (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage contribution of each major taxonomic group to the total number of associated taxa (left) and total abundance of individuals (right), across all sponge specimens examined.

In terms of abundance (Figure 3), crustaceans were the dominant group, comprising 60.8% of all recorded individuals across sponge specimens. They were followed by mollusks (23.6%), polychaetes (11.8%), and echinoderms (3.5%). Ascidians and sponges contributed less than 1% each to the total abundance. At the taxa level, the most abundant associates across all studied sponges were the crustaceans Synalpheus gambarelloides and Dardanus arrosor, accounting for 30.8% and 16% of the total abundance, respectively, followed by the bivalve Hiatella arctica (17.8%).

The most frequently occurring associates were the bivalve mollusk Hiatella arctica, found in 57.9% of sponge specimens, the polychaete Composetia hircinicola (49.1%), and the decapod crustaceans Pilumnus spinifer and Synalpheus gambarelloides (44.7% and 36.8%, respectively). All the remaining taxa were recorded in fewer than 17% of the sponge specimens examined.

3.2. Composition of Associated Communities

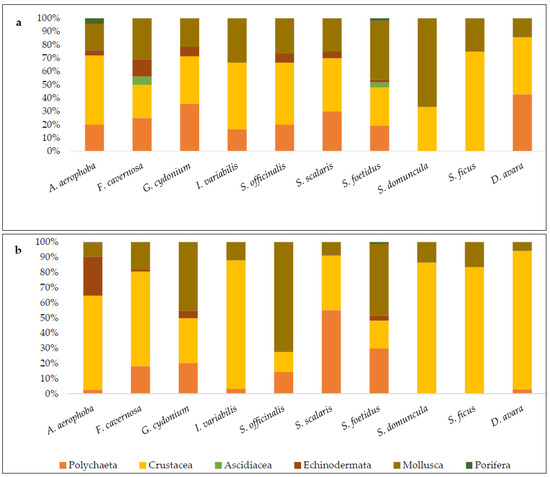

Mollusks and crustaceans were the only taxonomic groups present in the associated communities of all ten sponge species examined (Figure 4a). Polychaetes were also found in all sponge species except those of the family Suberitidae, while echinoderms were recorded in six of the ten sponge species (they were not found in Ircinia variabilis, Dysidea avara, and the two species of Suberitidae. Associated ascidians and sponges were found in only two host sponge species: ascidians were associated with Fasciospongia cavernosa and Sarcotragus foetidus, while sponges were found on Aplysina aerophoba and Sarcotragus foetidus.

Figure 4.

Percentage contribution of higher taxonomic groups to the associated communities of each sponge species in terms of (a) number of taxa and (b) abundance.

The structure of the associated communities varied across sponge species, particularly in terms of taxa richness within higher taxonomic groups (Figure 4a). Crustaceans and mollusks alternated as the most taxa-rich group among host sponges. Crustaceans exhibited the highest number of taxa in Aplysina aerophoba (52%), Ircinia variabilis (50%), Spongia (Spongia) officinalis (46.7%), Scalarispongia scalaris (40%), and Suberites ficus (75%), while mollusks dominated in Fasciospongia cavernosa (31.3%), Sarcotragus foetidus (46%), and Suberites domuncula (66.6%). In Dysidea avara and Geodia cydonium, crustaceans and polychaetes co-dominated, each representing 42.9% and 35.7%, respectively.

In terms of abundance (Figure 4b), crustaceans were the dominant group in six of the ten sponge species: Aplysina aerophoba (62%), Fasciospongia cavernosa (62.1%), Ircinia variabilis (84.6%), Suberites domuncula (85.6%), Suberites ficus (83.5%), and Ulosa digitata (91.3%). Mollusks dominated in Geodia cydonium (45.3%), Spongia (Spongia) officinalis (71.7%), and Sarcotragus foetidus (47.5%), while polychaetes were the dominant group only in Scalarispongia scalaris, where they represented 55.1% of total abundance.

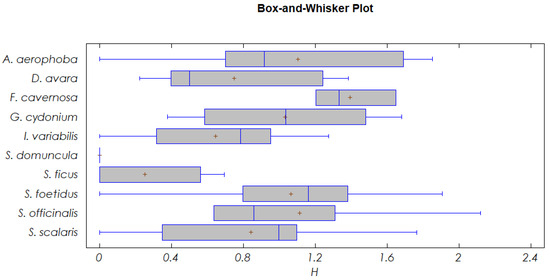

Shannon diversity index (H’) and the number of associates per liter of sponge differed significantly among host sponges (p < 0.05; Table 3). Fasciospongia cavernosa exhibited the highest diversity, followed by Spongia (Spongia) officinalis, Aplysina aerophoba, Sarcotragus foetidus, and Geodia cydonium. Intermediate diversity values were observed in Scalarispongia scalaris, Dysidea avara, and Ircinia variabilis, while the lowest values were recorded in Suberites ficus and S. domuncula (Figure 5). In contrast, Pielou evenness index (J’) did not differ significantly among sponge species (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of one-way ANOVA results testing the effect of the factor host-sponge on the Shannon diversity index (H’), Pielou species evenness (J’), and the abundance of associates per liter of sponge (N/L). Df: degrees of freedom; p: p-value. Asterisk (*) denotes statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level.

Figure 5.

Shannon diversity index (H’) values of the associated communities for each sponge species. Cross (+) denotes the median value.

The composition of the associated communities varied significantly both among the different sponge species and between the two depth zones (p < 0.05). Pairwise comparisons among sponge species revealed dissimilarity percentages ranging from 48.64% to 100%, with the highest dissimilarity observed between Suberites domuncula and all other sponges (Table 4 and Figure 6).

Table 4.

Pairwise dissimilarity (%) in the composition of associated communities among the examined sponge species. Aa: Aplysina aerophoba; Da: Dysidea avara; Fc: Fasciospongia cavernosa; Gc: Geodia cydonium; Iv: Ircinia variabilis; So: Spongia (Spongia) officinalis; Ss: Scalarispongia scalaris; Sfo: Sarcotragus foetidus; Sd: Suberites domuncula; and Sfi: Suberites ficus.

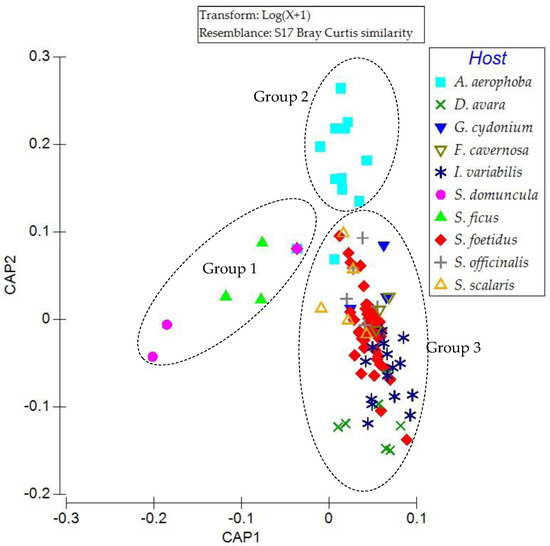

Figure 6.

Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates (CAP) plot for the associated communities of each sponge species (host), based on abundance data.

The examined sponge specimens appeared to group into three distinct clusters, based on the composition of their associated fauna (Figure 6). The sponges of the order Suberitida, characterized by monospecific associated communities, formed a clearly separated cluster (Group 1), with dissimilarity exceeding 94%. The specimens of Aplysina aerophoba, representing the order Verongiida, also formed a distinct cluster (Group 2), with dissimilarity percentages greater than 88% from all other species. A third, more heterogeneous cluster (Group 3) included species of the order Dictyoceratida, along with Geodia cydonium which belongs to the order Tetractinellida.

SIMPER analysis revealed that dissimilarity between the associated communities of Group 2 (Aplysina aerophoba specimens) (Appendix A Table A2) and those of Group 3 (Dictyoceratida and Geodia cydonium) (Appendix A Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6, Table A7, Table A8 and Table A9) was primarily due to the absence of three taxa from Group 2 specimens, which were present in high abundances in almost all specimens of Group 3. These associates were the bivalve Hiatella arctica, the decapod Synalpheus gambarelloides, and the polychaete Composetia hirsinicola. On the other hand, the associated communities of Group 2 were characterized by high abundance of the decapod Galathea intermedia and the brittle star Ophiothrix fragilis, neither of which was recorded in Group 3 specimens.

Different associated taxa dominated in each of the host sponges examined, as presented in detail in the Appendix A. The decapod Synalpheus gambarelloides dominated in terms of abundance, accounting for more than 50% in three sponge species: Dysidea avara (Appendix A, Table A3), Fasciospongia cavernosa (Appendix A, Table A4), and Ircinia variabilis (Appendix A, Table A5). The bivalve Hiatella arctica was dominant in the associated communities of Spongia (Spongia) officinalis (Appendix A, Table A6), Geodia cydonium (Appendix A, Table A7), and Sarcotragus foetidus (Appendix A, Table A8), representing nearly 70% of total abundance in the first species and more than 40% in the other two. In the sponge Scalarispongia scalaris, the polychaete Composetia hirsinicola was the most abundant associated taxa (Appendix A Table A9).

The highest taxa-per-liter ratio (S/L) of associated fauna was recorded in the sponge Suberites domuncula (S/L = 13.39), followed by Fasciospongia cavernosa (8.38), Dysidea avara (7.07), Suberites ficus (6.15), Aplysina aerophoba (5.91) and Spongia (Spongia) officinalis (5.70). All the remaining sponge species had S/L values below 3.5. Notably, although Sarcotragus foetidus hosted the highest number of associates, it exhibited the lowest taxa-per-liter ratio (S/L = 0.84).

Correlation analyses between sponge volume and community parameters (i.e., associated taxa richness, abundance, and Shannon diversity index) revealed positive relationships for all sponge species except Fasciospongia cavernosa and Dysidea avara (Table 5). In the former sponge volume was negatively correlated with all the above parameters, while in the latter sponge volume was negatively correlated with Shannon diversity index. For Suberites domuncula, correlation with the number of associates or Shannon diversity index was not applicable, since each specimen hosted one single associated taxon.

Table 5.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient between sponge volume and taxa richness (S), abundance (N) and Shannon diversity index (H’).

3.3. Effect of Subarea and Depth on Sponge-Associated Communities

As indicated by the PERMANOVA results for each sponge species (Table 6), the geographic range of the sampling area did not significantly influence the composition of the associated communities for most species, with the exception of Sarcotragus foetidus and Suberites domuncula (Table 6).

Table 6.

Statistical significance value (p-value) of the factor subarea in the composition of the associated community of each sponge species. Df: degrees of freedom. Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences at the 0.001 level.

As described in Section 2, the effect of depth on sponge-associated communities was investigated for the species Sarcotragus foetidus and Aplysina aerophoba, of which sufficient specimens were available from both depth zones (20–50 and 50–200 m).

The influence of depth varied among all parameters examined (Table 7). For Aplysina aerophoba, depth did not appear to have a statistically significant effect on any of the examined parameters (Shannon diversity index, Pielou evenness index, number of taxa, and abundance of associates per liter of sponge). In contrast, depth significantly influenced the abundance of associates in the community of Sarcotragus foetidus, with lower abundance recorded at 50–200 m compared to the 20–50 m depth zone. However, diversity and evenness indices were not significantly affected by depth.

Table 7.

Summary of one-way ANOVA results for the two examined depth zones (20–50 m and 50–200 m) for the following community parameters: Shannon diversity index (H’); Pielou species evenness (J’), taxa richness (S) and associates’ abundance per liter of sponge (N/L). Df: degrees of freedom; p: p-value. Asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences at the 0.05 level.

4. Discussion

Sponges are widely recognized as important habitat formers in various types of benthic habitats globally [1], and more specifically in the Mediterranean Sea (e.g., [5,6,12,16,20]). Understanding the ecology and structure of sponge-associated communities is crucial, as it enhances our knowledge of how these organisms contribute to the overall diversity and abundance of benthic ecosystems. This is particularly important for regions as the eastern Mediterranean, where ecological data from mesophotic and deep soft-substrate habitats remain limited. Despite its oligotrophic nature, this region has historically supported rich commercial sponge grounds in the Mediterranean basin [21,22]. Moreover, recent research has documented diverse sponge assemblages from bottom trawling grounds in the Aegean and Ionian Seas [10], further highlighting the ecological significance of these often-overlooked habitats.

The findings of this study—documenting 78 macrofaunal taxa and over 4600 individuals associated with ten sponge species—demonstrate that sponges significantly contribute to local biodiversity and structural complexity, even in trawled soft-substrate environments.

Among the associated taxa, mollusks and crustaceans alternated in dominance in terms of both taxa richness and abundance, while polychaetes consistently ranked third for both parameters. This pattern aligns with previous observations of sponge-associated communities in the eastern Mediterranean, reported for both hard [5,11,15,23,24] and soft substrates [18], as well as with studies conducted in tropical ecosystems [25].

Crustaceans have been found as the most abundant group in shallow sponge-associated communities [12,13,15,16] and in cave-dwelling sponges in the Aegean Sea [5]. The decapod Synalpheus gambarelloides, a sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp, was the most abundant crustacean in this study, dominating the associated communities in three sponge species (Dysidea avara, Fasciospongia cavernosa, and Ircinia variabilis). This pattern is consistent with previous studies from the Aegean and Levantine Seas [16,18,26]. Its dominance can be attributed to the social behavior and cooperative defense strategies typical of Synalpheus species, which are obligate sponge symbionts [27,28], as well as to their small size and high mobility that make them successful symbionts. Furthermore, the high occurrence of these snapping shrimps in these particular sponges appears to be associated with the large and spacious canals provided, which facilitate shrimp settlement. Notably, when shrimps inhabit sponges with narrower cavities and canals, such as those of Sarcotragus foetidus, they have been observed to enlarge the canals to a preferred size by consuming sponge tissue [16].

Among bivalve mollusks, Hiatella arctica was the most abundant, forming dense populations in Geodia cydonium and Sarcotragus foetidus. This bivalve has been frequently reported as a member of sponge-associated communities [5,12,29], preferring sponges with spacious canals and internal cavities [12], as observed in our study. Interestingly, while Hiatella arctica individuals are often covered with host sponge tissue [12], this was not observed in our samples, except in cases of empty, non-living shells. All living bivalves found in our study were freely located within the cavities of the sponges.

The brittle star Ophiothrix fragilis was the only echinoderm encountered. This species has been commonly documented as a sponge epibiont [5,11,12] mainly in sponges with pronounced surface relief and cavities, such as Agelas oroides and Aplysina aerophoba [12]. In our study, O. fragilis was also primarily found inhabiting the surface cavities of A. aerophoba, supporting previous findings.

While a relatively rare phenomenon [15,30,31], epibiotic sponges were also observed. In this study, two sponge species typical of hard substrates, Chondrilla nucula and Chondrosia reniformis, were found as epibionts on the surface of Aplysina aerophoba and Sarcotragus foetidus specimens. This finding supports the important role of sponges as habitat formers in soft bottoms, serving as “hard substrate islands” in extended soft sedimentary areas, thus offering settlement opportunities for species that typically inhabit hard substrates.

The composition of sponge-associated communities varied among host species. The greatest differentiation was observed between the faunal community associated with Aplysina aerophoba and those of the two examined Suberites species (S. domuncula and S. ficus). These sponges have very different morphology and structural features: Aplysina aerophoba typically has digitate projections with compact texture and few large canals—usually only one central canal per projection—while Suberites species have a dense, nearly spherical structure with a single central cavity. The external morphology of A. aerophoba, with its prominent surface cavities, favors colonization by larger and motile epibionts, such as the brittle star Ophiothrix fragilis and the anomuran decapod Galathea intermedia. Similar preferences have been reported in previous studies [12], where O. fragilis was found to prefer host sponges with strong surface relief and invaginations, like A. aerophoba.

Moreover, the associated communities of the examined sponges of the order Dictyoceratida, along with Geodia cydonium, exhibited similarities in species composition. These sponges are generally characterized by massive shapes and spacious, dense, and complex canal systems. Their associated communities were dominated by decapods (e.g., Synalpheus gambarelloides, Athanas nitescens), bivalves (Hiatella arctica), and polychaetes (Composetia hirsinicola), which is consistent with similar observations from sponges on soft substrates in the Levantine Sea [18]. These findings, coupled with the lack of statistically significant differences between the associated communities of the same sponge species across different sampling areas, further support the idea that sponge morphology is the primary factor influencing the composition of their associated communities [12]. This pattern does not appear to be restricted to the Mediterranean, as similar trends have been observed in amphipod populations associated with Dictyoceratida sponges from tropical regions [32].

Depth did not significantly affect Shannon diversity (H’), evenness, or taxa richness for the associated community of the two sponge species examined across depth gradients (A. aerophoba and S. foetidus), in line with similar findings from the Israeli coast [17]. However, S. foetidus specimens from the deeper zone (50–200 m) harbored significantly fewer individuals, echoing the general trend of declining faunal abundance with increasing depth [33,34,35,36]. Nevertheless, this depth-related variability requires further investigation to better understand its impact on sponge-associated communities.

Overall, the results of this study highlight the essential ecological role of sponges as habitat formers on mesophotic soft-substrate bottoms. Sponges provide refuge for diverse endobiotic invertebrates and function as “islands” of stable substrate within extensive muddy or sandy seafloors, on which sessile epibionts (e.g., other sponges, ascidians, and bryozoans), can settle. With this role, sponges enhance habitat complexity and benthic diversity in environments frequently disturbed by bottom-towed fishing gear. This becomes crucial in environments with limited sponge abundance, such as muddy bottoms, as it has been observed that in areas with low sponge diversity all available symbionts settle on the few sponges that are present [16]. Thus, the few available sponges accommodate disproportionately greater diversity, providing essential shelter and establishment opportunities for the associated organisms. Consequently, their removal during fishing operations not only causes direct mortality of the sponges themselves, but also destroys the complex communities they support.

In conclusion, this study highlights the need for comprehensive assessments of the functional role of sponges in the Mediterranean Sea and beyond. We also recommend that sponge-associated communities should be explicitly considered as part of the discards in trawl fisheries, since this type of fishing removes entire sections of host sponges and the diverse fauna they sustain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V., C.S. and V.G.; methodology, E.V., C.S. and V.G.; samples collection, C.S.; sample identification, E.V., C.S. and V.G.; software, C.S.; validation, C.S., V.G. and E.V.; formal analysis, C.S.; investigation, C.S.; data curation, C.S., E.V. and V.G. writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S., E.V. and V.G.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, E.V. and V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the National Fisheries Data Collection Program of Greece, funded by the Fisheries and Maritime Operational Program 2014–2020 of the Greek Ministry of Agricultural Development and Food, and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (2016SE08610004) and by the Implementation of Integrated Marine Water Monitoring Program, financed from the Financial Mechanism of the European Economic Area 2009–2014 and from the Public Investment Program of the Hellenic Republic (GR02-9XM EOX 2009–2012).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article or Appendix A.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of the first author’s PhD thesis at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. The authors would like to express their gratitude to: George Tserpes, Argyrios Kallianiotis, Emannouil Koutrakis and Stefanos Kavadas for providing the facility for marine research on board; the personnel of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research and the Fisheries Research Institute, Hellenic Agricultural Organization-DIMITRA, involved in the field work as well as captains and crews of the R/V “Philia” and the fishing vessels “Takis-Mimis” and “Megalochari” for their valuable operational support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of specimens per sponge species and information on the depth zone of collection, wet weight, volume, number of associated taxa (S) and number of individuals (N) found in each sample.

Table A1.

List of specimens per sponge species and information on the depth zone of collection, wet weight, volume, number of associated taxa (S) and number of individuals (N) found in each sample.

| Depth Zone (m) | Wet Weight (gr) | Volume (mL) | S | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aplysina aerophoba | |||||

| #2 | 50–200 | 771.3 | 510 | 9 | 73 |

| #3 | 50–200 | 781 | 600 | 9 | 107 |

| #4 | 50–200 | 307 | 152 | 3 | 17 |

| #5 | 50–200 | 369 | 200 | 6 | 29 |

| #8 | 20–50 | 670 | 640 | 6 | 11 |

| #38 | 20–50 | 305 | 180 | 2 | 3 |

| #58 | 20–50 | 1050 | 980 | 8 | 35 |

| #109 | 50–200 | 312 | 250 | 2 | 2 |

| #122 | 50–200 | 68 | 45 | 1 | 1 |

| #147 | 20–50 | 237 | 250 | 3 | 9 |

| #148 | 20–50 | 275 | 240 | 7 | 22 |

| #162 | 20–50 | 207 | 180 | 3 | 7 |

| Dysidea avara | |||||

| #47 | 20–50 | 232 | 250 | 3 | 27 |

| #130 | 20–50 | 218 | 230 | 3 | 29 |

| #139 | 20–50 | 195 | 200 | 4 | 11 |

| #140 | 20–50 | 75 | 90 | 2 | 5 |

| #166 | 50–200 | 172 | 20 | 2 | 17 |

| #189 | 20–50 | 161 | 130 | 4 | 12 |

| #228 | 20–50 | 65 | 70 | 5 | 17 |

| Fasciospongia cavernosa | |||||

| #34 | 20–50 | 594 | 480 | 10 | 74 |

| #35 | 20–50 | 714 | 980 | 8 | 35 |

| #59 | 20–50 | 445 | 450 | 7 | 33 |

| Geodia cydonium | |||||

| #1 | 20–50 | 13,100 | 6720 | 12 | 166 |

| #97 | 20–50 | 1949 | 1760 | 4 | 46 |

| #197 | 20–50 | 2840 | 3900 | 4 | 24 |

| #214 | 20–50 | 2082 | 2480 | 2 | 8 |

| Ircinia variabilis | |||||

| #17 | 20–50 | 253 | 230 | 4 | 31 |

| #19 | 20–50 | 194.5 | 180 | 3 | 32 |

| #49 | 50–200 | 1926 | 1770 | 3 | 10 |

| #136 | 20–50 | 310 | 340 | 3 | 27 |

| #137 | 20–50 | 512 | 500 | 4 | 75 |

| #149 | 20–50 | 235 | 290 | 4 | 41 |

| #150 | 20–50 | 154 | 190 | 3 | 20 |

| #151 | 20–50 | 66.5 | 70 | 1 | 11 |

| #152 | 20–50 | 50 | 25 | 2 | 8 |

| #153 | 20–50 | 50 | 25 | 1 | 6 |

| #154 | 20–50 | 86 | 50 | 1 | 2 |

| #168 | 20–50 | 378 | 380 | 4 | 40 |

| #178 | 50–200 | 999 | 950 | 4 | 9 |

| #304 | 50–200 | 1781 | 1790 | 4 | 8 |

| #306 | 20–50 | 961 | 1130 | 3 | 118 |

| Sarcotragus foetidus | |||||

| #11 | 20–50 | 73 | 30 | 2 | 7 |

| #12 | 20–50 | 281.3 | 275 | 3 | 40 |

| #13 | 20–50 | 2588.6 | 2120 | 9 | 247 |

| #28 | 50–200 | 877 | 890 | 6 | 59 |

| #29 | 20–50 | 768 | 795 | 3 | 61 |

| #33 | 20–50 | 3578 | 3120 | 8 | 104 |

| #37 | 20–50 | 2120 | 2010 | 8 | 165 |

| #39 | 50–200 | 840 | 750 | 6 | 17 |

| #43 | 20–50 | 1635 | 1500 | 6 | 95 |

| #64 | 20–50 | 770 | 680 | 11 | 92 |

| #77 | 50–200 | 2350 | 2180 | 8 | 34 |

| #78 | 50–200 | 2223 | 2210 | 5 | 76 |

| #94 | 20–50 | 517 | 450 | 6 | 26 |

| #95 | 20–50 | 440 | 350 | 6 | 39 |

| #96 | 20–50 | 325 | 225 | 4 | 9 |

| #113 | 20–50 | 7325 | 7200 | 16 | 611 |

| #115 | 50–200 | 706 | 870 | 8 | 77 |

| #116 | 50–200 | 304 | 300 | 4 | 12 |

| #117 | 50–200 | 228 | 260 | 2 | 3 |

| #131 | 50–200 | 222 | 240 | 1 | 1 |

| #142 | 20–50 | 432.4 | 400 | 5 | 22 |

| #143 | 20–50 | 269 | 305 | 4 | 14 |

| #155 | 20–50 | 1923 | 2210 | 10 | 280 |

| #156 | 50–200 | 1771 | 2610 | 6 | 21 |

| #167 | 20–50 | 662 | 670 | 12 | 103 |

| #176 | 50–200 | 1236 | 1050 | 6 | 42 |

| #177 | 50–200 | 1239 | 1150 | 6 | 30 |

| #179 | 50–200 | 3510 | 4045 | 12 | 63 |

| #183 | 20–50 | 6608 | 6450 | 16 | 304 |

| #184 | 50–200 | 851 | 950 | 5 | 30 |

| #190 | 20–50 | 459.2 | 500 | 5 | 33 |

| #195 | 20–50 | 1503 | 1500 | 11 | 49 |

| #196 | 50–200 | 2920 | 3030 | 4 | 57 |

| #210 | 50–200 | 109.5 | 80 | 4 | 9 |

| #211 | 50–200 | 393.4 | 400 | 1 | 4 |

| #212 | 50–200 | 474.8 | 450 | 1 | 1 |

| #226 | 20–50 | 535 | 640 | 2 | 18 |

| #230 | 20–50 | 461 | 470 | 4 | 23 |

| #233 | 20–50 | 2300 | 2300 | 7 | 86 |

| #305 | 50–200 | 1168 | 1710 | 3 | 11 |

| Scalarispongia scalaris | |||||

| #7 | 20–50 | 2678 | 2560 | 12 | 162 |

| #14 | 50–200 | 2060 | 1900 | 2 | 9 |

| #36 | 20–50 | 780 | 650 | 8 | 35 |

| #48 | 50–200 | 665 | 630 | 7 | 64 |

| #69 | 50–200 | 30 | 15 | 1 | 1 |

| Spongia (Spongia) officinalis | |||||

| #25 | 50–200 | 1150 | 1090 | 4 | 15 |

| #118 | 50–200 | 92 | 100 | 2 | 3 |

| #165 | 20–50 | 1173 | 1100 | 11 | 31 |

| #169 | 20–50 | 205.6 | 90 | 6 | 43 |

| #208 | 20–50 | 182.5 | 250 | 2 | 6 |

| Suberites domuncula | |||||

| #70 | 50–200 | 48 | 35 | 1 | 3 |

| #110 | 50–200 | 22 | 20 | 1 | 1 |

| #111 | 50–200 | 21 | 20 | 1 | 2 |

| #264 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #300 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #301 | 20–50 | 12 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #302 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #303 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #304 | 20–50 | 11 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #305 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #306 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #307 | 20–50 | 12 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| #308 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #309 | 20–50 | 11 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #310 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #311 | 20–50 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| #312 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #313 | 20–50 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Suberites ficus | |||||

| #107 | 50–200 | 494 | 425 | 2 | 2 |

| #108 | 50–200 | 101 | 110 | 2 | 4 |

| #290 | 50–200 | 70 | 60 | 1 | 1 |

| #555 | 50–200 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| #556 | 50–200 | 50 | 45 | 1 | 1 |

Table A2.

List of taxa comprising the community associated with the sponge Aplysina aerophoba. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A2.

List of taxa comprising the community associated with the sponge Aplysina aerophoba. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 7 | 58.3 | 25.8 | 25.8 |

| Galathea intermedia | 7 | 58.3 | 24.6 | 50.4 |

| Galathea bolivari | 4 | 33.3 | 15.6 | 65.9 |

| Pisidia bluteli | 4 | 33.3 | 6.0 | 72.0 |

| Carpias stebbingi | 3 | 25.0 | 4.5 | 76.4 |

| Hiatella arctica | 3 | 25.0 | 4.4 | 80.8 |

| Athanas nitescens | 2 | 16.7 | 3.8 | 84.6 |

| Musculus costulatus | 3 | 25.0 | 3.6 | 88.2 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 5 | 41.7 | 2.7 | 90.9 |

| Eualus cranchii | 3 | 25.0 | 1.5 | 92.4 |

| Urothoe sp. | 2 | 16.7 | 1.4 | 93.8 |

| Ceratonereis sp. | 1 | 8.3 | 1.1 | 94.9 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans | 1 | 8.3 | 0.9 | 95.8 |

| Mimachlamys varia | 1 | 8.3 | 0.9 | 96.6 |

| Munida intermedia | 1 | 8.3 | 0.6 | 97.2 |

| Isopoda unid. | 1 | 8.3 | 0.5 | 97.7 |

| Umbraculum umbraculum | 1 | 8.3 | 0.4 | 98.1 |

| Brachyura unid. | 1 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 98.5 |

| Eunice sp. | 1 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 98.8 |

| Decapoda unid. | 1 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 99.1 |

| Acasta sp. | 1 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 99.3 |

| Pteria hirundo | 1 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 99.5 |

| Phascolosoma (Phascolosoma) granulatum | 1 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 99.7 |

| Chondrilla nucula | 1 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 99.8 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 1 | 8.3 | 0.2 | 100 |

Table A3.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Dysidea avara. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A3.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Dysidea avara. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 7 | 100.0 | 81.5 | 81.5 |

| Hiatella arctica | 5 | 71.4 | 5.8 | 87.3 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 5 | 71.4 | 5.3 | 92.6 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 3 | 42.9 | 2.9 | 95.5 |

| Dardanus arrosor | 1 | 14.3 | 2.8 | 98.3 |

| Galathea intermedia | 1 | 14.3 | 1.0 | 99.3 |

| Galathea bolivari | 1 | 14.3 | 0.7 | 100.0 |

Table A4.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Fasciospongia cavernosa. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A4.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Fasciospongia cavernosa. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 3 | 100.0 | 51.4 | 51.4 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 2 | 66.7 | 15.5 | 66.9 |

| Hiatella arctica | 3 | 100.0 | 12.3 | 79.2 |

| Galathea intermedia | 1 | 33.3 | 5.5 | 84.8 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 2 | 66.7 | 3.6 | 88.3 |

| Anadara corbuloides | 2 | 66.7 | 2.5 | 90.8 |

| Musculus costulatus | 2 | 66.7 | 1.6 | 92.4 |

| Isopoda unid. | 1 | 33.3 | 1.6 | 94.0 |

| Serpula vermicularis | 2 | 66.7 | 1.2 | 95.2 |

| Aequipecten opercularis | 1 | 33.3 | 0.8 | 96.0 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans | 1 | 33.3 | 0.8 | 96.9 |

| Amphiura sp. | 1 | 33.3 | 0.8 | 97.7 |

| Mimachlamys varia | 1 | 33.3 | 0.8 | 98.4 |

| Nereididae unid. | 1 | 33.3 | 0.8 | 99.2 |

| Microcosmus vulgaris | 1 | 33.3 | 0.4 | 99.6 |

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 1 | 33.3 | 0.4 | 100.0 |

Table A5.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Ircinia variabilis. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A5.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Ircinia variabilis. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 12 | 80.0 | 78.9 | 78.9 |

| Hiatella arctica | 10 | 66.7 | 11.4 | 90.3 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 7 | 46.7 | 3.1 | 93.3 |

| Acasta sp. | 2 | 13.3 | 2.3 | 97.8 |

| Cymodoce truncata | 1 | 6.7 | 0.6 | 98.4 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 4 | 26.7 | 0.5 | 99.0 |

| Galathea intermedia | 1 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 99.3 |

| Striarca lactea | 1 | 6.7 | 0.2 | 99.6 |

| Thelopodidae unid. | 2 | 13.3 | 0.2 | 99.7 |

| Galathea bolivari | 1 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| Musculus costulatus | 1 | 6.7 | 0.1 | 100.0 |

| Calliostoma zizyphinum | 1 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

Table A6.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Spongia (Spongia) officinalis. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A6.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Spongia (Spongia) officinalis. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiatella arctica | 5 | 100 | 70.1 | 70.1 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 3 | 60 | 14 | 84.2 |

| Acasta sp. | 2 | 40 | 5.6 | 89.8 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 3 | 60 | 2.7 | 92.5 |

| Cymodoce truncata | 1 | 20 | 1.9 | 94.4 |

| Galathea bolivari | 1 | 20 | 1.9 | 96.4 |

| Athanas nitescens | 1 | 20 | 0.8 | 97.2 |

| Lima lima | 1 | 20 | 0.8 | 97.9 |

| Musculus costulatus | 1 | 20 | 0.6 | 98.6 |

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 1 | 20 | 0.6 | 99.2 |

| Galathea intermedia | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 99.4 |

| Harmothoe unid. | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 99.5 |

| Serpulidae unid. | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 99.7 |

| Striarca lactea | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 99.8 |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 100.0 |

Table A7.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Geodia cydonium. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A7.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Geodia cydonium. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geodia cydonium | ||||

| Hiatella arctica | 4 | 100.0 | 41.8 | 41.8 |

| Athanas nitescens | 1 | 25.0 | 19.5 | 61.4 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 3 | 75.0 | 17.5 | 78.9 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 2 | 50.0 | 5.0 | 83.8 |

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 2 | 50.0 | 4.3 | 88.1 |

| Pisidia bluteli | 1 | 25.0 | 4.2 | 92.3 |

| Anomia sp. | 1 | 25.0 | 2.8 | 95.2 |

| Neanthes acuminata | 1 | 25.0 | 1.2 | 96.4 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans | 1 | 25.0 | 0.9 | 97.4 |

| Mimachlamys varia | 2 | 50.0 | 0.9 | 98.3 |

| Galathea bolivari | 1 | 25.0 | 0.7 | 99.0 |

| Phascolosoma (Phascolosoma) granulatum | 1 | 25.0 | 0.5 | 99.5 |

| Oweniidae unid. | 1 | 25.0 | 0.2 | 99.8 |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 1 | 25.0 | 0.2 | 100.0 |

Table A8.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A8.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hiatella arctica | 33 | 82.5 | 38.4 | 38.4 |

| Composetia hircinicola | 31 | 77.5 | 24.3 | 62.7 |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 16 | 40.0 | 9.1 | 71.8 |

| Striarca lactea | 15 | 37.5 | 7.1 | 78.9 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 26 | 65.0 | 4.5 | 83.4 |

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 4 | 10.0 | 3.2 | 86.6 |

| Cymodoce truncata | 6 | 15.0 | 2.5 | 89.1 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans | 15 | 37.5 | 1.7 | 90.8 |

| Phascolosoma (Phascolosoma) granulatum | 8 | 20.0 | 1.3 | 92.1 |

| Composetia costae | 3 | 7.5 | 1.0 | 94.2 |

| Scoletoma funchalensis | 10 | 25.0 | 0.8 | 94.9 |

| Thelopodidae unid. | 10 | 25.0 | 0.8 | 95.7 |

| Acasta sp. | 2 | 5 | 0.7 | 96.4 |

| Galathea intermedia | 6 | 15.0 | 0.5 | 96.9 |

| Emarginula multistriata | 1 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 97.3 |

| Mimachlamys varia | 5 | 12.5 | 0.3 | 97.6 |

| Anadara corbuloides | 1 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 97.9 |

| Neopycnodonte cochlear | 2 | 5.0 | 0.3 | 98.2 |

| Athanas nitescens | 5 | 12.5 | 0.3 | 98.4 |

| Musculus costulatus | 2 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 98.6 |

| Nennalpheus sp. | 2 | 5.0 | 0.2 | 98.8 |

| Decapoda unid. | 3 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 98.9 |

| Galathea bolivari | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.1 |

| Polyplacophora unid. | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.1 |

| Brachyura unid. | 3 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 99.2 |

| Glyceridae unid. | 2 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 99.3 |

| Bittium reticulatum | 2 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 99.3 |

| Kurtiella bidentata | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.4 |

| Carpias stebbingi | 2 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 99.5 |

| Chama gryphoides | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.5 |

| Heteranomia squamula | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.6 |

| Pyura microcosmus | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.6 |

| Sternaspis scutata | 1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 99.7 |

| Eualus cranchii | 2 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 99.8 |

| Carinorbis clathrata | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.8 |

| Harmothoe sp. | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.8 |

| Didemnidae unid. | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Laetmonice hystrix | 2 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Munida sp. | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Euthria cornea | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Veneridae unid. | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Anomia ephippium | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 99.9 |

| Cyrillia linearis | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Kellia suborbicularis | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Jujubinus striatus | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Acanthocardia echinata | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Bittium latreillii | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Hexaplex trunculus | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| Tritia pygmaea | 1 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

Table A9.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Scalarispongia scalaris. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A9.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Scalarispongia scalaris. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composetia hircinicola | 5 | 100 | 53.1 | 53.1 |

| Acasta sp. | 2 | 40 | 28.0 | 81.1 |

| Hiatella arctica | 3 | 60 | 6.9 | 88.0 |

| Carpias stebbingi | 1 | 20 | 2.6 | 90.5 |

| Cymodoce truncata | 1 | 20 | 1.5 | 92.0 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 2 | 40 | 1.3 | 93.4 |

| Galathea intermedia | 1 | 20 | 1.1 | 94.4 |

| Synalpheus gambarelloides | 2 | 40 | 1.1 | 95.5 |

| Lepidasthenia elegans | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 96.0 |

| Musculus costulatus | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 96.6 |

| Ophiothrix fragilis | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 97.1 |

| Thelopodidae unid. | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 97.7 |

| Athanas nitescens | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 98.2 |

| Fusinus sp. | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 98.7 |

| Harmothoe spinifera | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | 99.3 |

| Glyceridae unid. | 1 | 20 | 0.2 | 99.5 |

| Dardanus arrosor | 1 | 20 | 0.1 | 99.6 |

| Gregariella semigranata | 1 | 20 | 0.1 | 99.7 |

| Mimachlamys varia | 1 | 20 | 0.1 | 99.9 |

| Phascolosoma (Phascolosoma) granulatum | 1 | 20 | 0.1 | 100.0 |

Table A10.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Suberites domuncula. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A10.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Suberites domuncula. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dardanus arrosor | 15 | 83.3 | 86.5 | 86.5 |

| Cerithiopsis barleei | 2 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 97.1 |

| Gracilipurpura rostrata | 1 | 5.6 | 2.9 | 100.0 |

Table A11.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Suberites ficus. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

Table A11.

List of taxa comprising the community associated of the sponge Suberites ficus. P: presence; F: frequency of appearance; mDa: mean dominant abundance (%); and cDa: cumulative abundance (%).

| P | F | mDa | cDa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pagurus prideaux | 2 | 40 | 67.9 | 67.9 |

| Cerithiopsis barleei | 2 | 40 | 16.5 | 84.4 |

| Paguridae unid. | 1 | 20 | 9.3 | 93.6 |

| Pilumnus spinifer | 2 | 40 | 6.4 | 100.0 |

References

- Bell, J.J. The functional roles of marine sponges. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2008, 79, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.J.; McGrath, E.; Biggerstaff, A.; Bates, T.; Cárdenas, C.A.; Bennett, H. Global conservation status of sponge. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.M.; Tendal, O.S.; Conway, K.W.; Pomponi, S.A.; van Soest, R.W.M.; Gutt, J.; Krautter, M.; Roberts, J.M. Deep-sea Sponge Grounds: Reservoirs of Biodiversity. In UNEP-WCMC Biodiversity Series No. 32; UNEP-WCMC: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, R.W.M.; Boury-Esnault, N.; Vacelet, J.; Dohrmann, M.; Erpenbeck, D.; De Voogd, N.J.; Santodomingo, N.; Vanhoorne, B.; Kelly, M.; A Hooper, J.N. Global Diversity of Sponges (Porifera). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerovasileiou, V.; Chintiroglou, C.C.; Konstantinou, D.; Voultsiadou, E. Sponges as “living hotels” in Mediterranean marine caves. Sci. Mar. 2016, 80, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, L.; Idan, T.; Shefer, S.; Ilan, M. Macrofauna inhabiting massive demosponges from shallow and mesophotic habitats along the Israeli Mediterranean Coast. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 612779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, D.; van de Poll, B.; Bertolino, M.; Rosso, A.; Guala, I. Massive stranding event revealed the occurrence of an overlooked and ecosystem engineer sponge. Mar. Biodivers. 2020, 50, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.J.; Strano, F.; Broadribb, M.; Wood, G.; Harris, B.; Resende, A.C.; Novak, E.; Micaroni, V. Sponge functional roles in a changing world. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2023, 95, 27–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chak, S.T.; Rubenstein, D.R. Social transitions in sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2000, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamouli, C.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Voultsiadou, E. Sponge Community Patterns in Mesophotic and Deep-Sea Habitats in the Aegean and Ionian Seas. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voultsiadou-Koukoura, E.; Koukouras, A.; Eleftheriou, A. Macrofauna Associated with the Sponge Verongia aerophoba in the North Aegean Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 1987, 24, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouras, A.; Voultsiadou-Koukoura, E.; Chintiroglou, H.; Dounas, C. Benthic Bionomy of the North Aegean Sea III. A comparison of the microbenthic animal assemblages associated with seven sponge species. Cah. Biol. Mar. 1985, 26, 301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Koukouras, A.; Russo, A.; Voultsiadou-Koukoura, E.; Dounas, C.; Chintiroglou, C. Relationship of Sponge Macrofauna with the Morphology of their Hosts in the North Aegean Sea. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 1992, 77, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çinar, M.E.; Ergen, Z. Polychaetes associated with the sponge Sarcotragus muscarum Schmidt, 1864 from the Turkish Aegean coast. Ophelia 1998, 48, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavloudi, C.; Christodoulou, M.; Mavidis, M. Macrofaunal assemblages associated with the sponge Sarcotragus foetidus Schmidt, 1862 (Porifera: Demospongiae) at the coasts of Cyprus and Greece. Biodivers. Data J. 2016, 4, e8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idan, T.; Shefer, S.; Chatzigeorgiou, G.; Gerovasileiou, V.; Goren, L. Testing the effect of host availability on endobiont diversity: Proposing the single hotel hypothesis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goren, L.; Idan, T.; Shefer, S.; Ilan, M. Sponge-Associated polychaetes: Not a random assemblage. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 695163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodoulou, M.; Jimenez, C.; Petrou, A.; Thasitis, I. Endobiotic communities of Marine Sponges in Cyprus (Levantine Sea). Heliyon 2019, 5, e01392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. VLIZ. 2025. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Bo, M.; Bertolino, M.; Bavestrello, G.; Canese, S.; Giusti, M.; Angiolillo, M.; Pansini, M.; Taviani, M. Role of deep sponge grounds in the Mediterranean Sea: A case study in southern Italy. Hydrobiologia 2012, 687, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voultsiadou, E.; Fryganiotis, C.; Porra, M.; Damianidis, P.; Chintiroglou, C.-C. Diversity of Invertebrate Discards in Small and Medium Scale Aegean Sea Fisheries. Open Mar. Biol. J. 2011, 5, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourt, M.; Faget, D.; Dailianis, T.; Koutsoubas, D.; Pérez, T. Past and present of a Mediterranean small-scale fishery: The Greek sponge fishery–its resilience and sustainability. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouras, A.; Voultsiadou, E.; Dounas, C.; Gogou, A.; Chindiroglou, H. Preliminary results on the qualitative and quantitative composition of the fauna associated with Littoral sponges at Chalkidiki Peninsula. Pascal Fr. 1979, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Çinar, M.E.; Bakir, K.; Doğan, A.S.; Kurt, G.; Katağan, T.; Öztürk, B.; Dağli, E.; Özcan, T.; Kirkim, F. Macro-benthic invertebrates associated with the black sponge Sarcotragus foetidus (Porifera) in the Levantine and Aegean Seas, with special emphasis on alien species. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 227, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.M.; Abdo, D.; Wahab, M.A.A.; Ekins, M.; Hooper, J.N.A.; Whalan, S. Cryptic biodiversity inhabiting coral reef sponges. Mar. Ecol. 2023, 44, e12747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, T.; Katağan, T. Decapod Crustaceans associated with the sponge Sarcotragus muscarum Schmidt, 1864 (Porifera: Demospongiae) from the Levantine coasts of Turkey. Iran. J. Fish. Sci. 2011, 10, 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J.E.; Morrison, C.L.; Rios, R. Multiple origins of Eusociality among sponge-dwelling shrimps (Synalpheus). Evolution 2000, 54, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultgren, K.; Duffy, E.; Rubenstein, D. Sociality in Shrimps. In Comparative Social Evolution; Rubenstein, D.R., Abbot, P., Eds.; Cambrich University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Çinar, M.E.; Katagan, T.; Ergen, Z.; Sezgin, M. Zoobenthos-inhabiting Sarcotragus muscarum (Porifera: Demospongiae) from the Aegean Sea. Hydrobiologia 2002, 482, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, S.E. Life on glass houses: Sponge stalk communities in the deep sea. Mar. Biol. 2001, 138, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, J.; Zea, S.; Powell, R.J.; Pawlik, J.R.; Hill, R.T. New epizooic symbioses between sponges of the genera Plakortis and Xestospongia in cryptic habitats of the Caribbean. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 2803–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, A.A.; Georges, A.M. Amphipoda living in sponges on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia (Crustacea, Amphipoda). Zootaxa 2017, 4365, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Ben Rais Lasram, F.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, Patterns, and Threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecchio, S.; Ramírez-Llodra, E.; Sardà, F.; Company, J.B.; Palomera, I.; Mechó, A.; Pedrosa-Pàmies, R.; Sanchez-Vidal, A. Drivers of deep Mediterranean megabenthos communities along longitudinal and bathymetric gradients. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 439, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecchio, S.; Ramírez-Llodra, E.; Sardà, F.; Company, J.B. Biodiversity of deep-sea demersal megafauna in western and central Mediterranean basins. Sci. Mar. 2011, 75, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maiorano, P.; Ricci, P.; Chimienti, G.; Calculli, C.; Mastrototaro, F.; D’oNghia, G. Deep-water species assemblages on the trawlable bottoms of the central Mediterranean: Changes or not over time? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1007671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).