Abstract

The latest climate change predictions indicate that the sea level will accelerate in the coming decades as a direct consequence of global warming. This is expected to seriously threaten low-lying coastal areas worldwide, resulting in severe coastal flooding with significant socio-economic impacts, leading to the loss of coastal settlements, exploitable land, and natural ecosystems. The main objective of this study is to provide a first-order preliminary estimation of potential inundation extents along the northern coastline of the Amvrakikos Gulf, a deltaic complex formed by the Arachthos, Louros, and Vouvos rivers in Western Greece, resulting from long-term sea-level rise induced by climate change, using the integrated Bathtub and Hydraulic Connectivity (HC) inundation method. A 2 m resolution Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was used, along with local long-term sea-level projections, for the years 2050 and 2100. Additionally, subsidence rates due to the compaction of deltaic sediments were taken into account. To assess the area’s proneness to inundation caused or enhanced by sea-level rise, the extent of each land cover type, the Natura 2000 Network protected area, the settlements, the total length of the road network, and the cultural assets located within the inundation zones under each climate change scenario were considered. The analysis revealed that under the optimistic SSP1-1.9 scenario of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), areas of 40.81 km2 (min 20.34 km2, max 63.55 km2) and 69.10 km2 (min 41.75 km2, max 88.02 km2) could potentially be inundated by 2050 and 2100, respectively. Under the pessimistic SSP5-8.5 scenario, the inundation zone expands to 42.56 km2 (min 37.05 km2, max 66.31 km2) by 2050 and 84.55 km2 (min 67.54 km2, max 116.86 km2) by 2100, affecting a significant portion of ecologically valuable wetlands and water bodies within the Natura 2000 protected area. Specifically, the inundated Natura 2000 area is projected to range from 37.77 km2 (min 20.30 km2, max 46.82 km2) by 2050 to 50.74 km2 (min 38.71 km2, max 62.84 km2) by 2100 under the SSP1-1.9 scenario, and from 39.34 km2 (min 34.53 km2, max 49.09 km2) by 2050 to 60.48 km2 (min 49.73 km2, max 82.5 km2) by 2100 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Four settlements with a total population of approximately 800 people, as well as 32 economic facilities most of which operate in the secondary and tertiary sectors and are small to medium-sized economic units, such as olive mills, farms, gas stations, spare parts stores, construction companies, and food service establishments, are expected to experience significant exposure to coastal flooding and operational disruptions in the near future due to sea-level rise.

1. Introduction

Climate change poses a significant and escalating threat to coastal communities worldwide, with sea-level rise standing out as one of its most pressing consequences. Over the past century, global sea levels have risen due to a combination of thermal expansion, glacial melt, and ice sheet disintegration [1].

Analyses of tide gauge records spanning from the late 19th to the early 21st century unequivocally demonstrate a persistent global mean sea-level rise, with rates between 1.6 to 1.9 mm/yr [1,2,3,4,5]. Since 1992, high-precision satellite altimetry has revealed a clear and significant acceleration, with global sea levels rising at 3.1 mm/yr from 1993 to 2017 [6,7]. The pace has quickened still further, reaching an alarming 3.7 mm/yr between 2006 and 2018 [8], reflecting the intensifying nature of contemporary sea-level rise. Human influence was very likely the main driver of these increases since at least 1971 [1]. The latest projections indicate that, under the most extreme Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP5-8.5) for climate change, global mean sea-level could increase by as much as 0.77 m by 2100, with an estimated range of 0.63 to 1.01 m [1]. Furthermore, climate model simulations suggest that this upward trend in global mean sea levels will persist for millennia, even in a scenario where CO2 emissions are reduced to net zero and global warming is halted [9]. This is due to the continued melting of glaciers and ice sheets, processes that will remain active long after greenhouse gas concentrations stabilize [1,8]. Satellite and model data analysis for the period 1993–2021 led to the assessment of sea level anomaly trends and coastal inundation across the Aegean, Ionian, and Cretan Seas. The results indicate a rising trend of 3.6 mm/yr, pronounced spatial and seasonal variability, and distinct hazard levels [10]. In addition, trend analysis of Italian seas from 1979–2018 shows significant positive increases in wave height, energy period, and wave power, particularly in the Ionian Sea and western Sardinia. These rising wave conditions are expected to enhance coastal vulnerability, drive shoreline retreat, increase flooding risk, and influence offshore operations and wave energy exploitation [11].

Vertical land movements arising from isostatic adjustment [12], tectonic activity [13,14], and subsidence driven by both natural sediment compaction and human interventions [15,16] can significantly amplify the apparent rate of sea-level rise and intensify its coastal impacts. Compelling evidence from recent decades shows that anthropogenic activities, most notably groundwater exploitation, hydraulic land reclamation and rapid urban expansion, have, in some cases, dramatically accelerated natural subsidence processes, resulting in downward land movement rates of up to 10 mm/yr [16,17,18,19]. The gradual, long-term rise in sea-level, often enhanced by land subsidence, has profound implications for low-lying coastal areas [20,21]. Over time, this rise can lead to the irreversible inundation of economically valuable coastal land and ecologically significant wetlands, accelerated shoreline erosion [22,23], degradation of cultural and historical sites, and the intrusion of saltwater into freshwater systems [24,25,26,27,28]. Recent research highlights the compounded effects of land subsidence, tectonic activity, and projected sea-level rise on coastal vulnerability in many places in Italy. Anzidei et al. [29] showed that long-term volcanic and tectonic subsidence on Lipari, combined with future sea-level rise, could cause significant coastal flooding by 2100, with relative sea-level increases up to 1.6 m. Similarly, high-resolution modeling of the Maddalena Peninsula (Sicily) by Anzidei et al. [30] indicates that regional subsidence and rising seas could submerge coastal areas by up to 0.65 m, leading to beach retreat and land loss. Complementing these findings, Antonioli et al. [31] projected relative sea-level rises up to 1.4 m for four Italian coastal regions, flooding approximately 5500 km2 of coastal plains. Collectively, these studies indicate that the interaction of tectonics, subsidence, and climate-driven sea-level rise poses substantial environmental, economic, and safety risks for coastal communities.

The potential impacts of this long-term climate change-induced coastal hazards make it imperative to develop strategies to assess and mitigate its negative effects [32,33]. Greece’s 16,000 km coastline hosts critical infrastructure, tourism, and population centers but faces increasing risks from climate change. Long-term sea-level rise and extreme storms threaten beaches, ecosystems, and coastal assets, with up to 89% of beaches projected to retreat under high-emission scenarios [34]. A recent socio-economic risk assessment of 15 beaches in the Peloponnese (Greece), applying a 100 m ICZM setback buffer, found that two-thirds are highly vulnerable to sea-level rise [35]. The study emphasizes that while sea-level rise drives physical beach retreat, high socio-economic value amplifies overall risks, revealing the need for targeted adaptation strategies that integrate environmental and socio-economic priorities.

One critical component of coastal resilience planning is the accurate identification of inundation zones under various long-term sea-level rise scenarios [36,37]. These zones delineate areas that are prone to gradual sea-level rise-induced flooding. Precise mapping of these zones allows policymakers, urban planners, and emergency response teams to implement risk mitigation strategies such as land-use planning, and infrastructure reinforcement. Without precise delineation, coastal communities remain highly vulnerable to the destructive impacts of climate change-induced flooding.

Various methods have been developed for the delineation and mapping of areas potentially subject to inundation as a result of sea-level rise, each with its own advantages and limitations [38]. The majority of these methods integrate geospatial analysis, elevation datasets, and sea-level projections to evaluate prospective coastal flood hazards. Recent advances in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), remote sensing technologies, and hydrodynamic modeling have significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of coastal inundation and flood mapping simulation [36,39] as well as the assessment of long-term trends and variability in sea level, wave dynamics, and related coastal hazards due to climate forcing [40]. Using 2D hydrodynamic models combined with DEMs and storm-track analysis, Kresteritis et al. [41] performed storm surge simulations for the NE Mediterranean (2000–2004) identifying high-risk coastal areas, particularly the northern Adriatic and SE Turkey, where sea-level rises exceeded 1 m. Makris et al. (2016) [42] employed RegCM3 (Regional Climate Model version 3), a numerical climate model designed to simulate climate at a regional scale, and provided higher-resolution projections than global models. The approach integrates downscaling and wave/storm surge models to assess the impacts of climate change on the Aegean and Ionian Seas. It projects increased storminess and extreme waves during the first half of the 21st century, followed by attenuation in the latter half, with northern coasts appearing more vulnerable to flooding and greater uncertainty in predictions. To leverage parallel computing capabilities for high-speed simulations and enable rapid mapping of coastal flooding hazards at a regional scale, Favaretto et al. [43] developed a Graphic Processing Unit (GPU)-accelerated 2D shallow-water model for the Venetian littoral. The approach combines high-resolution inundation modeling with Level II reliability analysis, producing hazard maps that identify vulnerable areas. Androulidakis et al. [44] investigated the 2020 IANOS Medicane using coupled hydrodynamic, meteorological, and coastal flooding simulations along with field and satellite data. Results revealed storm surges up to 30 cm and inundation extending 200 m inland. This integrated modeling framework effectively reproduced the observed storm impacts. Recently, Makris et al. [45] presented CoastFLOOD, a high-resolution 2D model for storm surge-induced coastal inundation in the Ionian Sea. Validated with satellite and hydraulic data, the model accurately predicts flood extent and timing highlighting the importance of terrain roughness in delineating inundated areas.

A widely used approach for estimating inundation extent is the “Bathtub” method, which overlays projected sea-level rise scenarios onto high-resolution DEMs to identify low-lying prone to inundation areas [46,47]. A simple (threshold) Bathtub approach classifies every DEM cell with an elevation ≤ a scenario water level as “inundated”, regardless of how water would actually reach the location. While this method alone offers computational efficiency and is well suited for large-scale assessments, it assumes a uniform water surface and does not account for dynamic processes such as wave action or storm surge [48,49]. The Bathtub-HC (Hydraulic-Connectivity) approach retains only the cells that are connected to the sea through a path whose elevation never exceeds the scenario water level. It is implemented using a flood-fill algorithm with either a 4-neighbor (rook) or 8-neighbor (queen) connectivity rule. Wherever possible, Bathtub-HC should be supplemented with more sophisticated approaches that incorporate hydrodynamic and hydrological modeling to more accurately simulate the complex interactions among sea-level rise, tidal dynamics, and coastal morphology [50,51].

In every methodological approach, vertical land motion, particularly subsidence, must be considered, as it can substantially amplify local relative sea-level rise, especially in deltaic environments and tectonically active regions [52]. The datasets used for such analyses typically combine sea-level projections from global climate models, most commonly those provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [8], with satellite-derived elevation data (e.g., LiDAR, SRTM) [53], and region-specific ground motion measurements obtained through InSAR techniques or services such as the Copernicus European Ground Motion Service (EGMS) [54].

This paper aims to evaluate future coastline changes for 2050 and 2100 in the northern sector of the shallow, semi-enclosed Amvrakikos Gulf in northwestern Greece, as a consequence of long-term sea-level rise under the optimistic (SSP1-1.9) and pessimistic (SSP5-8.5) scenarios, using a Bathtub-HC inundation model. Projected inundation areas are delineated and mapped using a 2 m-resolution DEM. Furthermore, as the study area is one of the most important ecosystems in Greece and hosts significant economic activities in agriculture, fishing, aquaculture, and tourism, a preliminary assessment of its proneness to climate change-induced coastal hazards is conducted. Within the projected inundation zones, the analysis evaluates the extent of land cover and Natura 2000 sites, the length of the road network, and the number of settlements, economic facilities (including olive mills, farms, gas stations, spare parts stores, construction companies, and food service establishments), and cultural monuments.

2. Study Area

The Amvrakikos Gulf, located in the northwestern part of Greece (eastern Mediterranean Sea), is a shallow, semi-enclosed marine embayment with a coastline length of 256 km and an area of 405 km2 (Figure 1). Depths in the gulf generally do not exceed 65 m. It is connected to the open Ionian Sea via a narrow (approximately 600 m wide) and shallow (<5 m, water depth) channel of 5 km in length [55,56,57,58].

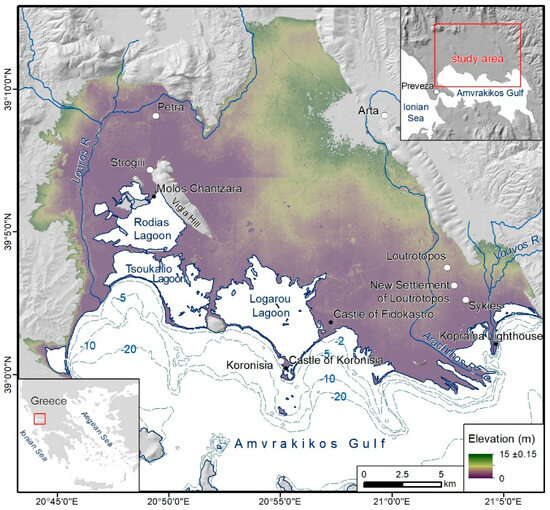

Figure 1.

DEM of the study area, obtained from the Hellenic Cadastre (Ktimatologio S.A.). The inset maps show the location of the study area within the Amvrakikos Gulf and within Greece.

The Amvrakikos Gulf, along with the Gulfs of Corinth and Patras and Lake Trichonis, form a series of late Plio-Quaternary extensional basins formed by back arc extensional faulting in onshore western Greece [59,60,61]. These geotectonically active basins evolved in a late phase of crustal extension associated with the broader Aegean marginal basin system. Oriented along a WNW-ESE structural trend, they are directly linked to active subduction processes along the western Hellenic Arc [62]. They are superimposed upon pre-existing Oligo-Miocene compressional structures, intersecting them rather than resulting from their reactivation [62].

The Amvrakikos Gulf has undergone major morphological changes throughout the Upper Quaternary, primarily driven by fluctuations in sea-level and neotectonic activity since it is a graben affected by active E or ESE-trending normal faults [59]. High-resolution 3.5-kHz seismic reflection profiling [57] reveals that during the last glacial low-stand, a lake occupied the eastern part of the Gulf, while the central and western Gulf were exposed subaerially, crossed by a network of incised river channels [63]. With the onset of the last post-glacial marine transgression, prior to 10 ka BP, seawater from the open Ionian Sea had already begun to inundate the area that now forms the present-day Gulf [58,64]. The main transgressive phase occurred between 11 ka and 10 ka, when seawater from the open Ionian Sea had already entered into the Gulf [58,64], ultimately culminating in the development of a maximum flooding surface around 6 ka. Subsequently, sea-level continued to rise gradually until approximately 2 ka BP. Over the last 2 ka, it has remained relatively stable, oscillating within a range of 1–2 m [58].

The northern margin of the Amvrakikos Gulf comprises a broad low-lying plain interspersed with isolated bedrock outcrops. The Gulf receives freshwater and sediment inputs from numerous rivers and streams (Figure 1). However, the sediment contribution from small rivers and seasonal streams draining the western, southern and eastern catchments of the Gulf is minimal and does not significantly influence the geomorphic development of the Gulf [65]. The Arachthos (2202 × 106 m3/yr) and Louros (609 × 106 m3/yr) rivers, discharging into the Gulf along its northern shoreline, are the primary contributors of both water and sediment [66], while the contribution of Vouvos River, which discharges into the northeastern shoreline of the Gulf, is much smaller. The Arachthos River is the most significant contributor in terms of both water and sediment fluxes, as it drains a substantially larger catchment (1894 km2) characterized by highly erodible lithologies and relatively high rainfall, resulting in high sediment loads exceeding 7 × 106 tonnes/yr [67]. In contrast, the Louros River drains a smaller catchment (785 km2), composed primarily of carbonate rocks, which generate comparatively lower sediment yields [68]. Consequently, the entire northern margin of the Amvrakikos Gulf, which is the focus of this study, comprises the joint low-lying deltaic plain of the Arachthos, Louros and Vouvos rivers (Figure 2), covering an area of approximately 350 km2 [69]. Archeological evidence and aerial photo analysis indicate rapid deltaic progradation during historical times, particularly in the case of the Arachthos River. This is further evidenced by the eastward migration of the Arachthos River mouth and a shift in the course of the Louros River, which once flowed east of Vigla Hill and now enters the Gulf to its west [69].

Figure 2.

Drone image of the northern coast of the Amvrakikos Gulf.

The hydrodynamic regime of the Amvrakikos Gulf is characterized by a predominantly quiescent wave environment, largely attributed to its limited fetch (<30 km) [70]. The gulf is characterized by a low-energy wind-wave environment, typical of semi-enclosed, fetch-limited Mediterranean embayments. Mean significant wave heights are generally below 1 m within the central gulf, with slightly higher values near the Preveza/Aktion Strait entrance (approaching ~1 m), reflecting partial exposure to the open Ionian Sea. According to the HNHS 2015 version of the Sea Level Statistics of Greek Ports the tidal range at the Preveza port tide-gauge (for the 1990–2012 period) varies from a maximum of 0.41 m to a mid-range of 0.15 m and a low range of 0.01 m [71], so wave energy is predominantly controlled by local wind forcing rather than tidal currents. These estimates are based on the Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS) Mediterranean Sea Waves Reanalysis [72] and represent typical conditions derived from modeled wave data for the region. Despite the generally weak water circulation, the gulf exhibits a remarkably complex pattern governed by prevailing winds directions and the complex coastal morphology. The dominant wind directions in the region are western and northwestern, often associated with the prevailing westerlies over the Ionian Sea. These winds can influence local weather conditions in the gulf. Wind patterns can exhibit seasonal changes, with variations in wind speed and direction affecting the gulf’s microclimate and hydrodynamics [73]. In the eastern sector, surface waters follow a predominantly clockwise circulation pattern, whereas in the western sector, the flow reverses, forming an anticlockwise gyre [74]. In the narrow Preveza/Aktion Strait, strong, oscillating currents reaching velocities of up to 1 m/s, present alternating directions, in response to tidal fluctuations.

The Amvrakikos Gulf is one of the most important ecosystems in Greece, bearing exceptional ecological value both nationally and internationally [75]. This significance was formally recognized in 1975, when its northern coastal zone, including the lagoons of Logarou, Rodia, Tsoukalio, Platanaki, Plamataris, Agrilos, the Arachthos delta, and the areas of Kommeno, Kopraina, Koronisia, Saloura, and Psathotopi, was collectively listed under the Ramsar Convention. However, extensive development projects during the 1980s altered the ecological character of the wetland, leading to the site’s inclusion in the Montreux Record in 1990 [76]. Subsequent conservation measures progressively strengthened its protection status. In 2006, the gulf and its wetlands were designated as Sites of Community Importance (SCI—code GR2110001). Two years later, the entire gulf, together with the surrounding lagoons, was officially declared the “Amvrakikos Wetlands National Park” (Government Gazette 123/D/21-03-2008). In 2011 the lagoons were further recognized as Special Protection Areas (SPA, code GR2110004) for birds, under national legislation (Law No. 3937/11—Government Gazette 60A/31-3-2011). Most notably, its northern sector, the focal point of this study, has been classified as a Core Biodiversity Area [76].

3. Materials and Methods

The primary objective of this study is to assess the shoreline displacement along the northern coast of Amvrakikos Gulf resulting from the projected rise in mean sea-level due to climate change, and to map the associated inundation zones. To this end, long-term sea-level rise is considered for 2050 and 2100 under the optimistic and pessimistic SSP scenarios (Figure 3). SSP1-1.9 reflects an ambitious low-emissions pathway consistent with the Paris Agreement objective of restricting global temperature increase to no more than 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, while SSP5-8.5 corresponds to a high-emission, fossil fuel-intensive scenario, characterized by continued economic growth with minimal climate mitigation or adaptation measures throughout the 21st century [8,77,78].

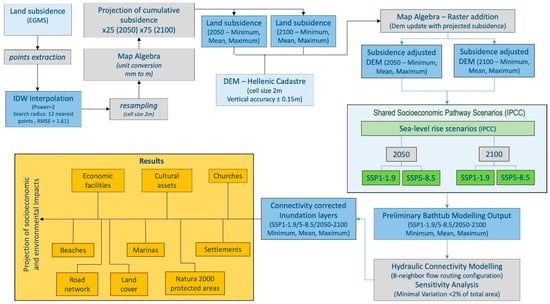

Figure 3.

Workflow diagram of the methodological approach applied in this study.

The datasets used in this study, along with their sources, spatial and temporal resolution, and specific application, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets used in the study.

Local sea-level rise predictions are obtained from the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool [79], which offers the latest up-to-date global and site-specific sea-level rise estimates spanning the period 2020 to 2150, relative to the 1995–2014 baseline period, in accordance with projections [8]. For this study, we used sea-level rise projection data from the Preveza tide gauge, the station nearest to the study area.

The delineation and mapping of the potentially inundated zones are carried out by identifying areas with topographic elevations lower than the projected future sea levels, thereby designating them as potentially prone to marine inundation [32,33,36]. This approach required the integration of topographic data with local sea-level projections. The coastal inundation analysis was based on the official 2 m-resolution DTM provided by the Hellenic Cadastre (National Cadastre and Mapping Agency S.A.). The dataset is referenced to the Greek Geodetic Reference System 1987 (GGRS87) and orthometric heights defined by the EGM96 geoid model. According to the Cadastre’s technical specifications, the DEM exhibits a vertical accuracy of ±0.15 m Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), which was propagated through the inundation mapping as an error band.

Particular emphasis is placed on the contribution of vertical ground movements to the evaluation of mean sea-level rise in the study area. As previously noted, the study area comprises the deltaic complex of the Arachthos, Louros, and Vouvos rivers. Subsidence resulting from the compaction of deltaic deposits is a factor that significantly contributes to mean sea-level rise in deltaic plains [15,39,80], where sediment accumulation is considerable. Subsidence rates are obtained from the Copernicus European Ground Motion Service (EGMS) [54], a product developed and operated by the European Environment Agency (EEA), under the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service (CLMS). EGMS measures and monitors millimetric-scale ground displacements, such as subsidence, using radar satellite images and Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) techniques, and provides free, high-resolution ground motion data across Europe. It should be noted that the ground motion data cover a relatively short period of almost four years (from 2019 to 2023). However, these are the only available vertical land motion data for the study area, as no other interferometric studies covering a longer period have been conducted.

To more accurately assess the contribution of vertical land motion across the study area, its value is removed from the “Individual Contributions” in the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool’s sea-level rise estimates for the Preveza station [79]. Additionally, projected subsidence for the years 2050 and 2100, derived from vertical land motion rates obtained from the EGMS, is incorporated into the DEM of the study area. Vertical land motion data are initially obtained as a vector map (EGMS Ortho) containing point-based estimates of average subsidence rates (in mm/yr) for the broader region, from which a shapefile was extracted to isolate only the points located within the study area. To produce a spatially continuous representation of subsidence, the Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation method is applied to the EGMS point data, generating a gridded surface that extends across the entire area, including areas without direct measurements. IDW is chosen as a simple yet effective deterministic method for interpolating spatially smooth variables, as it preserves local gradients while avoiding excessive smoothing [81]. A power parameter of 2 and a variable search radius including the 12 nearest observations is used to balance local detail and surface smoothness, preventing the influence of single extreme values on the interpolated surface. The interpolated subsidence data are then resampled to a spatial resolution of 2 × 2 m to match the cell size of the study area’s DEM. Using the “Raster Calculator,” pixel values are first divided by 1000 to convert vertical land motion rates from mm/yr to m/yr, and then multiplied by 26 and 76 to estimate cumulative subsidence by the years 2050 and 2100, respectively, relative to a 2024 baseline. This process produced two new raster layers representing projected subsidence for 2050 and 2100. Finally, the estimated subsidence raster layers for 2050 and 2100 are added to the original DEM using raster algebra, resulting in two projected DEMs that reflect anticipated topographic changes in the study area due to vertical land motion.

To account for uncertainties associated with the EGMS vertical land motion data and the original DEM, which have RMSE values of 1.61 mm and 0.15 m, respectively, the effect of these errors is included in the analysis. For each projection period (26 and 76 years), both the cumulative EGMS uncertainty and the vertical DEM error are subtracted from the projected elevation values to generate a “minimum elevation” surface, while both errors are added to produce a “maximum elevation” surface, by using the “Raster Calculator” tool. This process results in four additional DEMs representing minimum and maximum topographic conditions for the years 2050 and 2100, which define the plausible range of elevation changes due to vertical land motion and DEM uncertainty.

For each projection period (2050 and 2100), three DEMs are used. One representing the baseline projected elevation, one with minimum elevation, and one with maximum elevation. Similarly, for each SSP scenario (SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5), the mean, minimum, and maximum values of projected sea-level rise are considered. The inundation extent was first estimated using the mean sea-level rise in combination with the baseline DEM. To define the range of possible inundation, the lowest projected sea-level rise is combined with the DEM of maximum elevation, while the highest projected sea-level rise is combined with the DEM of minimum elevation. This approach provides a comprehensive assessment of potential inundation under both projection periods and SSP scenarios, accounting for the combined uncertainties of vertical land motion, DEM accuracy, and sea-level rise projections.

To calculate the inundation extent, the Bathtub-HC approach is applied by first identifying areas with elevation values lower than the projected sea-level rise for each scenario. To ensure realistic coastal inundation mapping and avoid overprediction of flood extent due to inclusion of isolated inland “blue puddles” [82,83,84], the preliminary Bathtub inundation raster is post-processed to enforce hydraulic connectivity with the sea. The procedure follows a standard 8-neighbor flow routing configuration [47,53,85,86], whereby only grid cells connected to the open sea through continuous low-elevation pathways are retained. The analysis is conducted using the “Region Group” tool in ArcGIS Pro V3.5. This tool identifies contiguous regions within the raster and allows the selection and extraction of only those cells that are directly connected to the sea. The resulting connectivity mask is applied to each scenario (SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5; 2050 and 2100) to remove unconnected low-lying depressions. A sensitivity check using both 4- and 8-neighbor rules indicated minimal variation (<2%) in total inundated area.

To provide a preliminary assessment of the socio-economic and environmental impacts, as well as the area’s proneness to sea-level rise due to climate change, the potentially inundated areas are analyzed for each sea-level rise scenario based on land cover types. Land cover information is sourced from two authoritative datasets. The first is the CORINE Land Cover (CLC 2018), provided by the European Union’s Copernicus Land Monitoring Service, offering comprehensive, freely accessible data at a spatial resolution of 100 m. The second dataset comprises Agricultural Block (ILOTS 2012) boundaries, derived from high-resolution orthophoto maps at a 1:5000 scale and supplied by the Hellenic Ministry of Rural Development and Food. Even though these land cover sources are coarser and older than the 2 m DEM and may misclassify narrow features such as levees and roads in low-lying wetlands (as in the study area), we consider them appropriate for a preliminary estimation of the land cover types occupying the potentially inundation zones. In addition, the spatial distribution of potentially affected settlements, critical infrastructure and cultural heritage assets (including road networks, cultural monuments, churches, and economic facilities), and critical natural assets (such as beaches and environmentally valuable Natura 2000 protected areas) is compared with the potential inundation zones identified and mapped in this study.

To organize, manage, and support the geospatial analysis conducted in this study, a spatial database was developed within the open-source Geographic Information System (GIS) software QGIS 3.44.3 ‘Solothurn’. All primary calculations and map preparations were performed using QGIS, while ArcGIS Pro V3.5 was also utilized for complementary spatial analysis and data management tasks.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sea-Level Rise and Inundation Projections

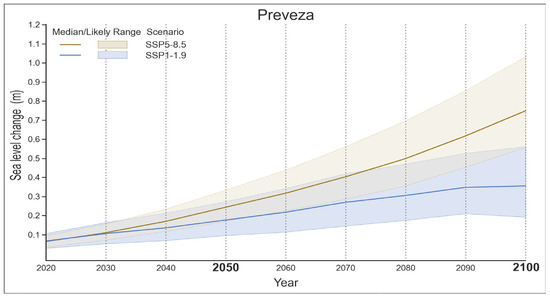

The sea-level values used to delineate the inundation zones across the study area are presented in Table 2 and visualized in Figure 4. The chart displays future sea-level projections for the Preveza tide gauge station, based on data from the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool [79].

Table 2.

Mean sea-level projections used to evaluate potential coastal inundation under the considered scenarios. The mean sea-level projections correspond to the Preveza tide gauge station and are acquired from the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool [79].

Figure 4.

Sea-level rise projections for the Preveza tide gauge station under the SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, based on data from the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool [79].

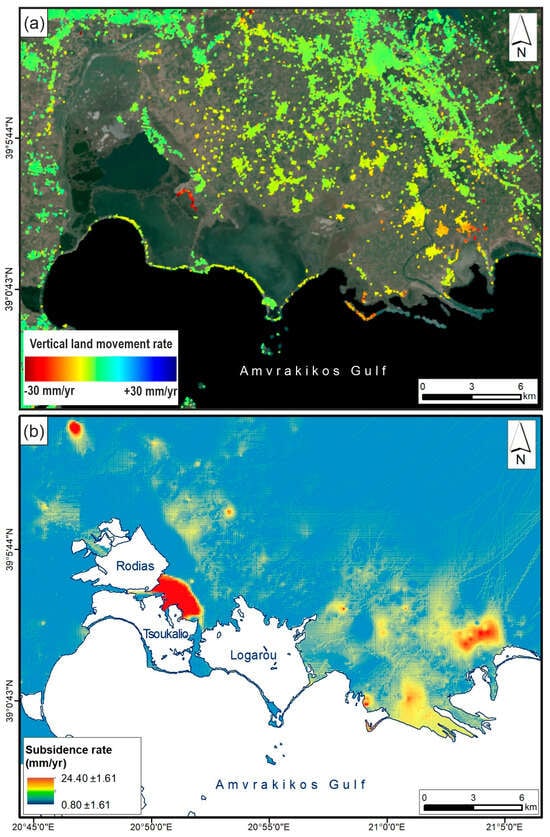

The total vertical land motion, valued at 0.01 m, is excluded from the “Individual Contributions” in the projections as the vertical displacement is acquired by the Copernicus European Ground Motion Service [54]. Hence, under the SSP1-1.9 scenario, the projected sea-level rise (excluding vertical land motion) is 0.17 m (min 0.09 m, max 0.27 m) by 2050 and 0.34 m (min 0.19 m, max 0.56 m) by 2100, while for the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the corresponding values are 0.24 m (min 0.17 m, max 0.33 m) and 0.74 m (min 0.56 m, max 1.03 m), respectively. In the final estimation of sea-level rise values, the spatial distribution of vertical ground motion is also taken into account Figure 5a. The map in Figure 5b displays the locations of subsidence rate measurements within the study area. These rates correspond to the period 2019–2023 and are used to calculate the total projected subsidence at each point for the years 2050 and 2100. In total, 9004 points were taken into account, all of which exhibit subsidence, with rates ranging from −0.8 ± 0.5 mm/yr up to −26.40 ± 3.30 mm/yr. High vertical displacement values are observed along the sandbars that define the lagoons, as well as along parts of the inner shoreline of the Tsoukalio Lagoon, the elongated spit west of the Arachthos River estuary, and the section of the delta plain north-northwest of the Vouvos River mouth.

Figure 5.

(a) Vertical ground motion map of the coastal area along the northern shore of Amvrakikos Gulf, acquired from the Copernicus European Ground Motion Service [54]. (b) Vertical ground motion map after the application of the Inverse Distance Weighted (IDW) interpolation method.

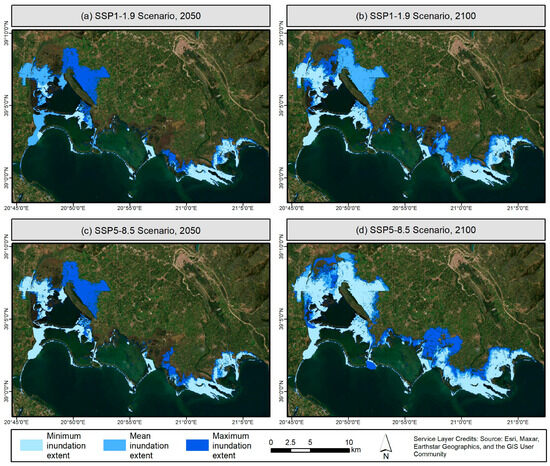

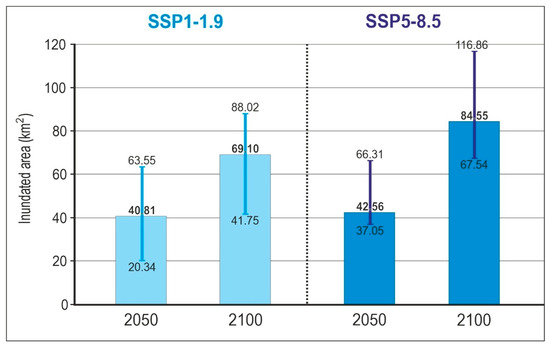

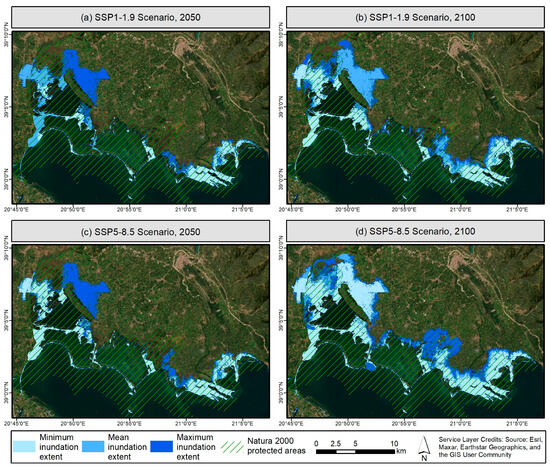

The analyses identify coastal areas that lie below projected future sea levels, revealing locations significantly prone to inundation under the two considered sea-level rise scenarios for both the medium term (2050) and the long term (2100). The results of our analysis are presented in Figure 6 and Figure 7, providing detailed visualization of the areas projected to be inundated under both the optimistic and pessimistic sea-level rise scenarios in the medium- (2050) and long-term (2100) periods. Assuming the SSP1-1.9 scenario, the area projected to be affected by sea-level rise is estimated at 40.81 km2 (min 20.34 km2, max 63.55 km2) and 69.10 km2 (min 41.75 km2, max 88.02 km2) by 2050, increasing to 69.10 km2 (min 41.75 km2, max 88.02 km2) by 2100. Under the more pessimistic SSP5-8.5 scenario, inundation-prone areas are projected to reach 42.56 km2 (min 37.05 km2, max 66.31 km2) by 2050 and 84.55 km2 (min 67.54 km2, max 116.86 km2) by 2100. The areas most prone to inundation are concentrated around the mouth of the Louros River, the northwestern and southeastern shores of the Rodia Lagoon, the southeastern shores of the Logarou Lagoon, and the broader estuarine regions of the Arachthos and Vouvos Rivers (Figure 6). In all scenarios, except for the mean and minimum inundation extents under both the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios by 2050, the inundation zones also include a substantial low-lying area extending north and east of the elongated NW–SE trending Vigla Hill (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Maps showing projected mean, minimum and maximum inundation extents of low-lying areas by 2050 and 2100 under SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Figure 7.

Projected mean, minimum, and maximum extents of inundated low-lying areas by 2050 and 2100 under the SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

It is noteworthy that, under all considered sea-level rise scenarios, the sandy barriers, barrier islands, and spits along the northern shores of the Amvrakikos Gulf are projected to undergo profound morphological adjustment and possible transgression. Sediment redistribution processes are expected to maintain the geomorphological expression of these features in modified forms.

4.2. Projected Socioeconomic and Environmental Impacts of Sea-Level Rise

4.2.1. Prone to Inundation Settlements and Road Network

The analysis shows that Strogili and Koronisia, two settlements in the study area with permanent populations of 136 and 134, respectively (according to the 2021 census) [87], are expected to be directly affected by sea-level rise even under the optimistic SSP1-1.9 scenario by 2050. Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, two additional settlements Petra, and Loutrotopos, with populations of 308 and 194 residents, respectively, are projected to fall within the maximum extent inundation zone and face potential impacts [87]. Thus, approximately 800 inhabitants (according to the 2021 census) along the northern shore of the Amvrakikos Gulf are exposed to climate change-induced coastal hazards as they live in settlements located in areas highly susceptible to inundation. This number corresponds to 7% of the population of the settlements located on the delta plain.

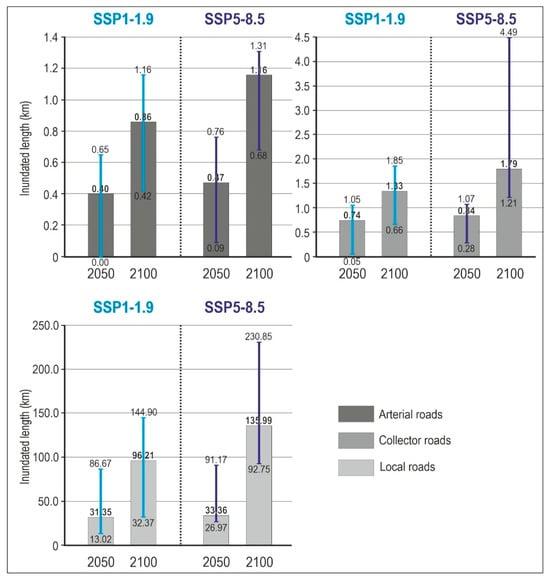

Three types of roads are considered in this study, based on their function, importance, design, and connectivity (Figure 8). These include arterial roads, which refers to the main roads or highways that form the backbone of the region’s transportation system; collector roads, which connects smaller towns or regional centers to the arterial roads; and local roads, comprising those that serve villages, settlements, agricultural areas, and remote locations. The projected lengths of each road category prone to inundation under medium- and long-term scenarios, are shown in Figure 8. It is important to note that while the length of the road network within potentially inundated areas was estimated, this does not necessarily indicate a functional disruption. Among the road categories, the local roads network is expected to be the most severely affected, with 31.35 km (min 20.30 km, max 46.82 km) projected to fall within the potentially inundated zone by 2050 under the SSP1-1.9 scenario. This estimation increases significantly to 96.21 km (min 32.37 km, max 144.90 km) by 2100 under the same scenario. For the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the corresponding lengths are projected to be 33.36 km (min 26.97 km, max 91.17 km) by 2050 and 135.99 km (min 92.75 km, max 230.85 km) by 2100. In contrast, the projected lengths for the other road categories remain significantly lower. Under the pessimistic SSP5-8.5 scenario, up to 1.79 km (min 1.21 km, max 4.49 km) of the collector roads is projected to be affected by 2100. The arterial road, part of the National Road Preveza–Filippiada (E21), is expected to be inundated along approximately 1.16 km (min 0.68 km, max 1.31 km) of its length.

Figure 8.

Projected mean, minimum, and maximum lengths of potentially inundated arterial, collector, and local road networks by 2050 and 2100 under the SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Even for the local road network, it is certain that realignment of segments expected to be inundated is necessary. Although the maintenance and reconstruction of road infrastructure is particularly costly, it remains unavoidable, as it is directly linked to a region’s accessibility [88]. If even a small section of the E21 is flooded, a detour would be required, entailing the construction of a significantly longer road segment and resulting in disproportionately higher cost. According to the European Court of Auditors (2013) [89], the construction cost of major road arteries amounts to € 4,159,281 per km. This value is indicative, as each project is specific and actual costs depend on local conditions.

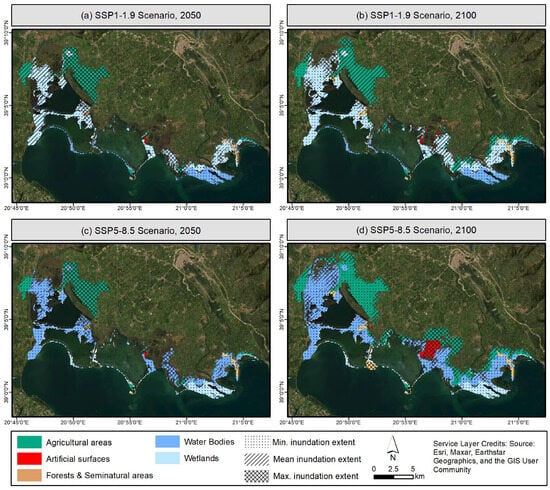

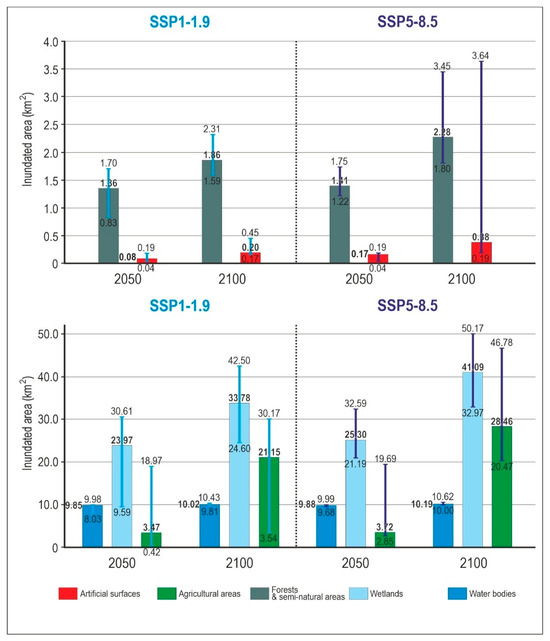

4.2.2. Land Cover Types Within Inundation Zones

By delineating potential future shoreline positions, this study effectively identifies the land cover types most prone within the study area (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Approximately 58.73% (min 47.15%, max 48.16%) of the area projected to be affected by mid-term sea-level rise (2050) under the optimistic SSP1-1.9 scenario, equivalent to 23.97 km2 (min 9.59 km2, max 30.61 km2), is occupied by wetlands. This proportion remains nearly unchanged at 59.45% (min 57.19%, max 49.15%) under the pessimistic SSP5-8.5 scenario by the same year. The affected wetland area increases to 33.78 km2 (min 24.60 km2, max 42.50 km2) and 41.09 km2 (min 32.97 km2, max 50.17 km2) under the SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, respectively, by 2100. A much smaller portion of the inundation zones consists of open water surfaces, covering approximately 9.85 km2 (min 8.03 km2, max 9.98 km2), which are projected to be affected under all sea-level rise scenarios. Both wetlands and open water bodies are of exceptional ecological importance, serving as vital habitats for numerous threatened bird species and support high levels of biodiversity in both fauna and flora [90,91].

Figure 9.

Maps showing land cover types of low-lying areas projected to be inundated by 2050 and 2100 under SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Figure 10.

Projected mean, minimum, and maximum inundated area by land cover type by 2050 and 2100 under the SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Agricultural land, which holds significant socioeconomic value for the study area, is relatively limited within the inundation zones of both the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios up to 2050, covering approximately 3.47 km2 (min 0.42 km2, max 18.97 km2) and 3.72 km2 (min 2.85 km2, max 19.69 km2), respectively. However, agricultural land is expected to comprise 30.61% (min 8.48%, max 34.28%) of the inundation zone in the optimistic scenario and 33.66% (min 30.31%, max 40.03%) in the pessimistic scenario by 2100, with the affected areas expanding to 21.15 km2 (min 3.54 km2, max 30.17 km2) and 28.46 km2 (min 20.47 km2, max 46.78 km2), respectively. The main crops in these areas include forage plants, olive groves, and citrus trees. Coastal inundation and salt-water intrusion raise soil salinity and can reduce the productivity of crops by limiting water uptake and altering nutrient balance [92]. Olive trees are moderately salt-tolerant compared to many crops, but their tolerance is variable by cultivar and declines under combined stress (salinity accompanied by drought and flooding) [93]. Citrus trees in coastal or low-lying zones are very highly vulnerable to sea-level rise driven inundation and salinization. Their tolerance to salt is low, so even moderate increases in soil/irrigation salinity or periodic inundation can cause substantial yield/health declines [94]. Forage crops in low-lying coastal zones are highly vulnerable to inundation and salinization, leading to significant productivity losses unless salt-tolerant varieties or adaptive management practices are employed [92]. Finally, forests and semi-natural areas occupy a very small portion of the inundation zones, amounting to 2.28 km2 (min 1.80 km2, max 3.45 km2) under the SSP5-8.5 scenario by 2100.

The analysis clearly indicates that, in addition to the impacts of sea-level rise on the natural environment, the primary sector, representing the main economic activity in the study area, will also be significantly affected.

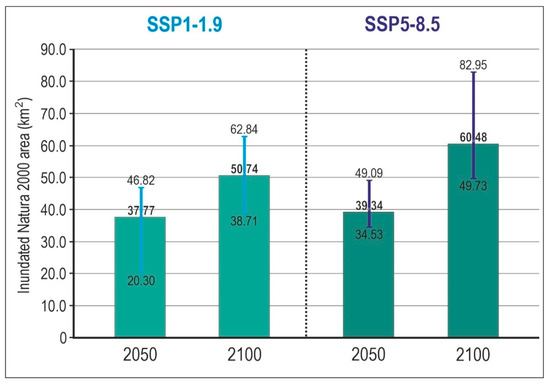

4.2.3. Prone to Inundation Natura 2000 Areas

The extent of Natura 2000 protected areas within the low-lying inundation zones, identified under both sea-level rise scenarios (SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5) was also assessed (Figure 11 and Figure 12). The results indicate that the degradation and landward shift in these environmentally valuable areas could be substantial, even under the most optimistic mid-term (2050) scenario. However, it should be acknowledged that in some locations, this change may represent a spatial redistribution rather than a permanent disappearance, as coastal landforms and associated habitats may migrate landward in response to sea-level rise. In such cases, the extent of impact will depend on the availability of accommodation space and the absence of physical barriers that could restrict this natural transgression. Under this optimistic scenario, Natura 2000 areas cover approximately 37.77 km2 (min 20.30 km2, max 46.82 km2) of the inundation zone, corresponding to 82.75% (min 99.80%, max 73.67%) of the total potentially inundated area by 2050. By 2100, under the long-term pessimistic scenario, the extent of the inundation-prone Natura 2000 area increases to 60.48 km2 (min 49.73 km2, max 82.95 km2) (71.53%—min 73.63%, max 70.98%—of the projected totally inundated area).

Figure 11.

Maps showing mean, minimum and maximum extents of Natura 2000 areas projected to be inundated by 2050 and 2100 under SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios.

Figure 12.

Projected mean, minimum, and maximum extents of Natura 2000 potentially inundated areas under different climate scenarios (SSP1-1.9 and SSP5-8.5) for 2050 and 2100.

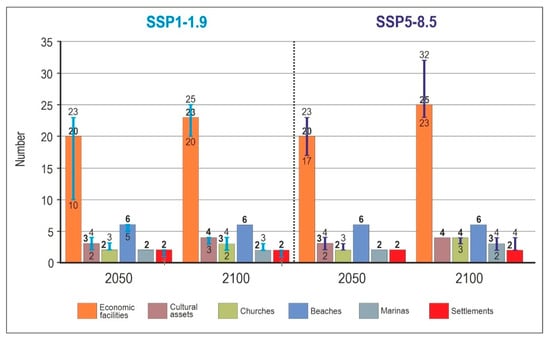

4.2.4. Cultural and Socioeconomic Impacts of Projected Sea-Level Rise

A crucial component in evaluating the study area’s proneness to sea-level rise is the identification and documentation of exposed to inundation monuments and key infrastructure under the scenarios considered [95].

Among the cultural assets located within the inundation zones across all scenarios are the Molos Chantzara, the Kopraina Lighthouse, and the recently renovated Koulia Castle of Koronisia, a fortification dating back to 1807 that now occasionally hosts cultural events. Another significant cultural asset, prone to flooding, is Fidokastro Castle, which holds considerable archeological importance as a fortress believed to have been constructed during the Byzantine period, likely in the 9th century. Its walls are built upon large stone blocks from an earlier fortification, dated to 219 BC, which is believed to have been an ancient acropolis. Fidokastro Castle is projected to be affected by long-term sea-level rise by 2100 under the optimistic scenario and by both medium- and long-term sea-level rise under the pessimistic SSP5-8.5 scenario. Furthermore, both the Museum of Natural History of the Amvrakikos Gulf and the Fishing Museum are exposed to sea-level rise under all scenarios. Three churches are particularly prone to inundation under all scenarios, for both medium- and long-term projections (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Mean, minimum, and maximum number of exposed assets by category under the optimistic (SSP1-1.9) and pessimistic (SSP5-8.5) sea-level rise scenarios for 2050 and 2100.

Regarding economic facilities within the study area, 20 (min 10, max 23) are located at a lower elevation than the projected shoreline under the mid-term (up to 2050) SSP1-1.9 scenario. Under the long-term SSP5-8.5 scenario, the number of prone to coastal flooding economic facilities increases to 25 (min 23, max 32). Most of these operate in the secondary and tertiary sectors and are small to medium-sized economic units, such as olive mills, farms, gas stations, spare parts stores, construction companies, and food service establishments, primarily linked to settlements exposed to sea-level rise. Additionally, two fish farms are expected to be affected even under the optimistic mid-term scenario, while under the pessimistic scenario, three fish farms and two additional aquaculture facilities, comprising fattening units for marine fish, freshwater species, and mollusks [96], are projected to be impacted. Sea-level rise may significantly affect aquaculture operations by increasing the risk of coastal flooding, altering water quality through salinity changes, thereby compromising infrastructure integrity and operational stability [97].

Negative impacts on the beaches within the study area are expected under all sea-level rise scenarios. From a tourism perspective, the most significant are two beaches in Koronisia and one in Platanaki, located west of the Arachthos River mouth, and the Rama beach situated at the easternmost part of the study area. Another key piece of infrastructure highly prone to inundation, even under the most optimistic sea-level rise scenario, is the Koronisia marina.

To protect wetlands, water bodies, and coastal communities from sea-level rise, a mix of nature-based, structural, and planning strategies is essential [98]. Nature-based solutions such as living shorelines, wetland restoration [99], dune construction, submerged vegetation, and natural breakwaters help stabilize coasts, reduce erosion, and absorb floodwaters [100]. Hard engineering measures like seawalls, groynes, flood barriers, and elevated structures provide additional protection against flooding. Long-term adaptation requires careful planning through shoreline setbacks, updated flood zones, managed retreat, and integrating coastal resilience into community development to ensure sustainable protection for both people and ecosystems [101]. However, implementing these measures and strategies in the study area necessitates more comprehensive, multidisciplinary research and integrated approaches.

4.3. Methodological Considerations

The local sea-level rise predictions used in this study were those obtained from the NASA Sea-level Projection Tool [79] for the tide gauge station nearest to the study area, namely the Preveza station. It should be acknowledged that, although site specific, these projections represent ensemble means rather than precise physical inputs for local modeling [102,103,104].

Although this assessment is based on a Bathtub-HC inundation model, it is considered appropriate for the preliminary evaluation of sea-level rise impacts along the northern shore of the Amvrakikos Gulf. This suitability is due to the area’s sheltered nature, minimal tidal variation, low wave energy resulting from short fetch distances, and weak surface circulation, characteristics typical of a semi-enclosed, microtidal marine environment [74,105]. Furthermore, the application of the Bathtub-HC inundation model has, in many cases, proven its methodological robustness for coastal flood modeling at regional and subregional scales [49]. However, no hydrodynamic processes are represented, as the method assumes a uniform water surface. The approach neglects spatial variations in water level caused by factors such as friction, bathymetry, channelization, wind stress, Coriolis effects, atmospheric pressure, and geometric constrictions (e.g., narrow straits). As a result, the approach can overestimate inland inundation in semi-enclosed gulfs and estuaries, while underestimating it along open coasts where wave setup and runup dominate. It may also underestimate overtopping and overwash on exposed coasts and barrier systems, particularly when temporal dynamics are absent. Moreover, the method does not simulate flow routing, velocities, or momentum, and therefore cannot capture backwater effects or failures in rural or urban drainage channels.

The assessment of land subsidence in the study area is of particular importance, as it constitutes a significant factor contributing to relative sea-level rise. The extrapolation of the 2019–2023 deformation trend to 2100 is presented here as an assumption-based scenario rather than a validated projection. Given the non-stationary nature of subsidence processes, these results should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

In addition, it is important to acknowledge the vertical uncertainties associated with the datasets used, which may influence the extent of the modeled inundation zones. Although the DEM used in this study has a high spatial resolution (2 m) and a reported vertical accuracy of ±0.15 m, even small deviations can cause differences in inundation extent within the extremely low-relief coastal plain of the northern Amvrakikos Gulf, where elevation changes are often measured in decimeters. The accuracy of the DEM may decrease in coastal and wetland areas, where vertical biases can exceed the nominal RMSE, potentially affecting inundation extent estimates in the low-gradient deltaic environment of the study area. Similarly, the subsidence rates derived from the Copernicus European Ground Motion Service (EGMS) are based on InSAR measurements with a nominal precision of ±1.61 mm; when extrapolated to 2050 and 2100, this may accumulate to ±0.05–0.20 m in total vertical displacement. Combined, these uncertainties could locally approach ±0.3–0.4 m, potentially affecting the absolute extent of projected inundation, particularly across very gentle slopes. Nevertheless, because the analysis focuses on relative spatial trends and scenario-based comparisons, the overall patterns and identification of prone to inundation zones remain robust. The results should therefore be interpreted as indicative of potential inundation rather than exact predictions of future shoreline positions.

By identifying the most vulnerable zones within the study area, the results of the analysis provide critical guidance for prioritizing coastal management interventions aimed at mitigating the projected economic consequences of the anticipated sea-level rise and preserving the ecological integrity of natural assets [106,107]. However, to more accurately assess potential damage on buildings in flood-prone settlements and to evaluate the capacity for natural adaptation in dynamic coastal systems along the ecologically fragile northern shores of the gulf, the application of more advanced, high-resolution dynamic models is recommended. It should also be noted that the estimation of road length within inundated areas provides an indication of potential exposure rather than actual functional disruption. Since infrastructure elements such as embankments, bridges, and culverts may remain above floodwaters, these results should be viewed as indicative and not as confirmed service interruptions.

Future work could involve the use of reduced-complexity flood models (e.g., LISFLOOD-FP inertial/diffusion; SFINCS; CoastFLOOD; FLO2D-class solvers), or, where feasible, full 2-D shallow water equation SWE and 3-D hydrodynamic models (TELEMAC-2D, TUFLOW FV, Delft3D-FLOW in 2-D mode, SCHISM, etc.). In addition, a comprehensive assessment of vulnerability, associated damage costs, and the quantification of the exposed assets significance is planned as part of future work.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the Bathtub-HD method, applied by overlaying projected sea-level rise scenarios onto the 2 m resolution DEM, proves an effective approach for identifying low-lying areas prone to inundation from climate change-induced long-term sea-level rise along the northern shore of the Amvrakikos Gulf.

The analysis revealed that the spatial distribution of land surface subsidence rates significantly influences the extent of the potentially inundated areas. This subsidence is primarily driven by the natural compaction of sediments within the deltaic complex of the Louros, Arachthos, and Vouvos rivers and occurs at rates ranging from −0.8 ± 0.5 mm/yr to −24.40 ± 3.30 mm/yr during the period 2019–2023, contributing substantially to relative sea-level rise in the study area. Under the low-emissions SSP1-1.9 pathway, sea-level rise alone is projected to submerge approximately 40.81 km2 (min 20.34 km2, max 63.55 km2) of land by 2050, increasing to 69.10 km2 (min 41.75 km2, max 88.02 km2) by 2100. Under the high-emissions SSP5-8.5 scenario, areas prone to permanent flooding are projected to reach 42.56 km2 (min 37.05 km2, max 66.31 km2) by 2050 and 84.55 km2 (min 67.54 km2, max 116.86 km2) by 2100.

A comparison of the potentially inundated zones with the spatial distribution of land cover types, settlements, critical infrastructure, and natural assets indicates that the study area is highly prone to flooding or inundation from long-term sea-level rise. Under the long-term (by 2100) SSP5-8.5 scenario, approximately two to four settlements with approximately 300 to 800 inhabitants, along with 25 to 32 associated economic facilities, along with 138.94 km (min 94.64, max 236.65) km of roads of all types and two to four marinas are expected to be directly affected. The cultural monuments Molos Chantzara, Kopraina Lighthouse, Koulia Castle, and Fidokastro Castle are also exposed to inundation, even under the most optimistic sea-level rise projections. Furthermore, the potentially inundated areas contain 33.66% (min 30.31%, max 40.03%) of valuable agricultural land, representing a significant threat to the primary sector, which remains one of the main drivers of economic activity in the study area.

Under the worst-case scenario, a substantial portion of the projected inundation zones 60.48 km2 (min 49.73 km2, max 82.5 km2) consists of ecologically important wetlands and water bodies, which are designated Natura 2000 protected areas within the “Amvrakikos Wetlands National Park”. Based on the spatial analysis of potential inundation zones, priority areas for targeted dynamic simulations and monitoring include the Vigla Hill flank, the Arachthos and Louros river mouths, and the Rodia/Logarou inner shores, where the risk of long-term sea-level rise impacts is highest.

The delineation and mapping of inundation zones resulting from gradual sea-level rise-driven flooding, together with the identification of the most prone areas by land cover type within these zones, are essential for effective coastal resilience planning. Such mapping enables targeted land-use planning, infrastructure reinforcement, and tailored flood-risk management and mitigation strategies. Without it, coastal communities, economic activities, and natural assets remain highly exposed to the destructive impacts of climate change-induced flooding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., E.K., M.S. and K.T.; methodology, S.R., D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F., D.-V.B., M.S. and E.K.; software, S.R., D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F. and D.-V.B.; validation, S.R., D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F., D.-V.B., M.S. and E.K.; formal analysis, S.R., D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F., D.-V.B., M.S. and E.K.; resources, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R., D.K., C.P. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, S.R., D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F., D.-V.B., M.S. and E.K.; visualization, D.K., C.P., K.T., A.F., D.-V.B. and E.K.; supervision, M.S. and E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Editor-in-Chief and the reviewers for their time, insightful comments, and helpful suggestions that strengthened the final version of our manuscript. This paper and related research have been conducted during and with the support of the Italian interuniversity PhD course in sustainable development and climate change (www.phd-sdc.it).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A.; White, N.J. Sea-Level Rise from the Late 19th to the Early 21st Century. Surv. Geophys. 2011, 32, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, C.C.; Morrow, E.; Kopp, R.E.; Mitrovica, J.X. Probabilistic Reanalysis of Twentieth-Century Sea-Level Rise. Nature 2015, 517, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevrejeva, S.; Moore, J.C.; Grinsted, A.; Matthews, A.P.; Spada, G. Trends and Acceleration in Global and Regional Sea-Levels since 1807. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 113, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.D.; Domingues, C.M.; Slangen, A.B.A.; Dias, F.B. An Ensemble Approach to Quantify Global Mean Sea-Level Rise over the 20th Century from Tide Gauge Reconstructions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 044043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legeais, J.-F.; Ablain, M.; Zawadzki, L.; Zuo, H.; Johannessen, J.A.; Scharffenberg, M.G.; Fenoglio-Marc, L.; Fernandes, M.J.; Andersen, O.B.; Rudenko, S.; et al. An Improved and Homogeneous Altimeter Sea-level Record from the ESA Climate Change Initiative. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerem, R.S.; Beckley, B.D.; Fasullo, J.T.; Hamlington, B.D.; Masters, D.; Mitchum, G.T. Climate-Change Driven Accelerated Sea-Level Rise Detected in the Altimeter Era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 2022–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pirani, A., Connors, S.L., Péan, C., Berger, S., Caud, N., Chen, Y., Goldfarb, L., Gomis, M.I., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 3–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Nicholls, R.J.; Goodwin, P.; Haigh, I.D.; Lincke, D.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Hinkel, J. Quantifying Land and People Exposed to Sea-Level Rise with No Mitigation and 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C Rise in Global Temperatures to Year 2300. Earth’s Future 2018, 6, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulidakis, Y.; Makris, C.; Mallios, Z.; Krestenitis, Y. Sea level variability and coastal inundation over the northeastern Mediterranean Sea. Coast. Eng. J. 2023, 65, 514–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caloiero, T.; Aristodemo, F. Trend detection of wave parameters along the Italian Seas. Water 2021, 13, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K. Sea-Level Change and Shore-Line Evolution in Aegean Greece since Upper Palaeolithic Time. Antiquity 1996, 70, 588–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Chalkias, C.; Chalkias, G.; Grigoropoulou, E.; Manthos, G.; Ferentinou, M. Assessment of the Sensitivity of the Southern Coast of the Gulf of Corinth (Peloponnese, Greece) to Sea-Level Rise. Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. 2012, 4, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Tsanakas, K.; Tsodoulos, I.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Papanastassiou, D.; Batzakis, D.-V.; Stamoulis, K. Late Quaternary Marine Terraces and Tectonic Uplift Rates of the Broader Neapolis Area (SE Peloponnese, Greece). J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcharidis, I.; Kourkouli, P.; Karymbalis, E.; Foumelis, M.; Karathanassi, V. Time Series Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry for Ground Deformation Monitoring over a Small Scale Tectonically Active Deltaic Environment (Mornos, Central Greece). J. Coast. Res. 2012, 29, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumban-Gaol, J.; Sumantyo, J.T.S.; Tambunan, E.; Situmorang, D.; Antara, I.M.O.G.; Sinurat, M.E.; Suhita, N.P.A.R.; Osawa, T.; Arhatin, R.E. Sea-level Rise, Land Subsidence, and Flood Disaster Vulnerability Assessment: A Case Study in Medan City, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, S.M.; Mamoun, M.M.; Al-Mobark, N.M. Vulnerability Assessment of the Impact of Sea-level Rise and Land Subsidence on North Nile Delta Region. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 32, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aucelli, P.P.C.; Di Paola, G.; Incontri, P.; Rizzo, A.; Vilardo, G.; Benassai, G.; Buonocore, B.; Pappone, G. Coastal Inundation Risk Assessment Due to Subsidence and Sea-level Rise in a Mediterranean Alluvial Plain (Volturno Coastal Plain–Southern Italy). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 198, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Lio, C.; Tosi, L. Land Subsidence in the Friuli Venezia Giulia Coastal Plain, Italy: 1992–2010 Results from SAR-Based Interferometry. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Drakou, E.; Karymbalis, E.; Tragaki, A.; Gallousi, C.; Liquete, C. Modelling and mapping coastal protection: Adapting an EU-wide model to national specificities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragaki, A.; Gallousi, C.; Karymbalis, E. Coastal hazard vulnerability assessment based on geomorphic, oceanographic and demographic parameters. Land 2018, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milli, S.; Girasoli, D.E.; Tentori, D.; Tortora, P. Sedimentology and coastal dynamics of carbonate pocket beaches: The Ionian Apulia coast between Torre Colimena and Porto Cesareo (Apulia, southern Italy). J. Mediterr. Earth Sci. 2017, 9, 29–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ghionis, G.; Poulos, S.E.; Verykiou, E.; Karditsa, A.; Alexandrakis, G.; Andris, P. The impact of an extreme storm event on the barrier beach of the Lefkada Lagoon, NE Ionian Sea (Greece). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2015, 16, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science 2010, 328, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, S.; Palombo, L.; Molinaroli, E.; Brambill, W.; Conforti, A.; De Falco, G. Shoreline Response to Wave Forcing and Sea-level Rise along a Geomorphological Complex Coastline (Western Sardinia, Mediterranean Sea). Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Gallousi, C.; Cundy, A.; Tsanakas, K.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Tsodoulos, I.; Batzakis, V.-D.; Papanastassiou, D.; Liapis, I.; Maroukian, H. Long-Term Spatial and Temporal Shoreline Changes of the Evinos River Delta, Gulf of Patras, Western Greece. Z. Geomorphol. 2022, 63, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampazas, G.; Karymbalis, E.; Chalkias, C. Assessment of the sensitivity of Zakynthos Island (Ionian Sea, Western Greece) to climate change-induced coastal hazards. Z. Geomorphol. 2022, 63, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Chalkias, C.; Ferentinou, M.; Chalkias, G.; Magklara, M. Assessment of the sensitivity of Salamina and Elafonissos islands to sea-level rise. J. Coast. Res. 2014, 70 (Suppl. S1), 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzidei, M.; Bosman, A.; Carluccio, R.; Casalbore, D.; D’Ajello Caracciolo, F.; Esposito, A.; Nicolosi, I.; Pietrantonio, G.; Vecchio, A.; Carmisciano, C.; et al. Flooding scenarios due to land subsidence and sea-level rise: A case study for Lipari Island (Italy). Terra Nova 2017, 29, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzidei, M.; Scicchitano, G.; Tarascio, S.; De Guidi, G.; Monaco, C.; Barreca, G.; Mazza, G.; Serpelloni, E.; Vecchio, A. Coastal retreat and marine flooding scenario for 2100: A case study along the coast of Maddalena Peninsula (southeastern Sicily). Geogr. Fis. Din. Quat. 2018, 41, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonioli, F.; Anzidei, M.; Amorosi, A.; Lo Presti, V.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Deiana, G.; De Falco, G.; Fontana, A.; Fontolan, G.; Lisco, S.; et al. Sea-level rise and potential drowning of the Italian coastal plains: Flooding risk scenarios for 2100. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2017, 158, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paola, G.; Rizzo, A.; Benassai, G.; Corrado, G.; Matano, F.; Aucelli, P.P.C. Sea-Level Rise Impact and Future Scenarios of Inundation Risk along the Coastal Plains in Campania (Italy). Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzakis, D.-V.; Karymbalis, E.; Tsanakas, K. Assessing coastal vulnerability to climate change-induced hazards in the Eastern Mediterranean: A comparative review of methodological approaches. In Geographic Information Science: Case Studies in Earth and Environmental Monitoring; Petropoulos, G., Chalkias, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velegrakis, A.F.; Monioudi, I.; Tzoraki, O.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Tragou, E.; Hasiotis, T.; Asariotis, R.; Andreadis, O. Coastal hazards and related impacts in Greece. In The Geography of Greece: Managing Crises and Building Resilience; Darques, R., Sidiropoulos, G., Kalabokidis, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karditsa, A.; Poulos, S.E. Socio-economic risk assessment of the setback zone in beaches threatened by sea level rise-induced retreat (Peloponnese coast—Eastern Mediterranean). Anthr. Coasts 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelli, V.; Sarkar, N.; Micallef, A.S.; Soldati, M.; Rizzo, A. Coastal Inundation Scenarios in the North-Eastern Sector of the Island of Gozo (Malta, Mediterranean Sea) as a Response to Sea-level Rise. J. Maps 2023, 19, 2145918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, A.H.; Pirotti, F.; Masiero, M.; Rahman, M. Mapping inundation from sea-level rise and its interaction with land cover in the Sundarbans mangrove forest. Clim. Change 2023, 176, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarin, C.; Pantillon, F.; Davolio, S.; Bajo, M.; Miglietta, M.M.; Avolio, E.; Carrió, D.S.; Pytharoulis, I.; Sánchez, C.; Patlakas, P.; et al. Assessing the coastal hazard of Medicane Ianos through ensemble modelling. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 2273–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, K.; Karymbalis, E.; Batzakis, D.-V. Advances in geographical information science for monitoring and managing deltaic environments: Processes, parameters, and methodological insights. In Geographic Information Science: Case Studies in Earth and Environmental Monitoring; Petropoulos, G., Chalkias, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 279–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, C.; Barbaro, G.; Petrucci, O.; Besio, G.; Foti, G.; Barillà, G.C.; Puntorieri, P. Analysis of the concurrent conditions of floods and sea storms: A case study of Crotone, Italy. WIT Trans. Eng. Sci. 2020, 129, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krestenitis, Y.N.; Androulidakis, Y.S.; Kontos, Y.N.; Georgakopoulos, G. Coastal inundation in the north-eastern Mediterranean coastal zone due to storm surge events. J. Coast. Conserv. 2011, 15, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, C.; Galiatsatou, P.; Tolika, K.; Anagnostopoulou, C.; Kombiadou, K.; Prinos, P.; Velikou, K.; Kapelonis, Z.; Tragou, E.; Androulidakis, Y.; et al. Climate change effects on the marine characteristics of the Aegean and Ionian Seas. Ocean Dyn. 2016, 66, 1603–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, C.; Martinelli, L.; Ruol, P. Coastal flooding hazard due to overflow using a Level II method: Application to the Venetian littoral. Water 2019, 11, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulidakis, Y.; Makris, C.; Mallios, Z.; Pytharoulis, I.; Baltikas, V.; Krestenitis, Y. Storm surges and coastal inundation during extreme events in the Mediterranean Sea: The IANOS Medicane. Nat. Hazards 2023, 117, 939–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, C.; Mallios, Z.; Androulidakis, Y.; Krestenitis, Y. CoastFLOOD: A high-resolution model for the simulation of coastal inundation due to storm surges. Hydrology 2023, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesch, D.B. Analysis of Lidar Elevation Data for Improved Identification and Delineation of Lands Vulnerable to Sea-Level Rise. J. Coast. Res. 2009, 10053, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulter, B.; Halpin, P.N. Raster Modeling of Coastal Flooding from Sea-Level Rise. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2008, 22, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmalkar, I.; Wagenaar, D.; Bill-Weilandt, A.; Choong, J.; Manimaran, S.; Lim, T.N.; Rabonza, M.; Lallemant, D. Flow-Tub Model: A Modified Bathtub Flood Model with Hydraulic Connectivity and Path-Based Attenuation. MethodsX 2023, 12, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lück-Vogel, M.; Williams, L.L. Evaluating the enhanced bathtub model for coastal flood risk assessment in Table Bay, South Africa. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 2775–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeri, D.L.; Hagen, S.C.; Plant, N.G.; Bilskie, M.V.; Medeiros, S.C.; Alizad, K. Tidal Hydrodynamics under Future Sea-level Rise and Coastal Morphology in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Earth’s Future 2016, 4, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nienhuis, J.H.; Lorenzo-Trueba, J. Simulating Barrier Island Response to Sea-level Rise with the Barrier Island and Inlet Environment (BRIE) Model v1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2019, 12, 4013–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, R.J.; Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J.; Brown, S.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Meyssignac, B.; Hanson, S.E.; Merkens, J.; Fang, J. A Global Analysis of Subsidence, Relative Sea-Level Change and Coastal Flood Exposure. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesch, D.B. Best practices for elevation-based assessments of sea-level rise and coastal flooding exposure. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus European Ground Motion Service. Available online: https://egms.land.copernicus.eu/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Piper, D.J.W.; Panagos, A.G.; Kontopoulos, N. Some Observations on Surficial Sediments and Physical Oceanography of the Gulf of Amvrakia. Thalassographica 1982, 5, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Poulos, S.E.; Lykousis, V.; Collins, M.B. Late Quaternary Evolution of Amvrakikos Gulf, Western Greece. Geo-Mar. Lett. 1995, 15, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapsimalis, V.; Pavlakis, P.; Poulos, S.; Alexandri, S.; Tziavos, C.; Sioulas, A.; Filippas, D.; Lykousis, V. Internal Structure and Evolution of the Late Quaternary Sequence in a Shallow Embayment: The Amvrakikos Gulf, NW Greece. Mar. Geol. 2005, 222–223, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, S.E.; Kapsimalis, V.; Tziavos, C.; Pavlakis, P.; Leivaditis, G.; Collins, M. Sea-Level Stands and Holocene Geomorphological Evolution of the Northern Deltaic Margin of Amvrakikos Gulf (Western Greece). Z. Geomorphol. N.F. Suppl. 2005, 137, 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Clews, J.E. Structural Controls on Basin Evolution: Neogene to Quaternary of the Ionian Zone, Western Greece. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 1989, 146, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, R.; Meyer, B.; Hubert, A.; Barka, A. Westward Propagation of the North Anatolian Fault into the Northern Aegean: Timing and Kinematics. Geology 1999, 27, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karymbalis, E.; Ferentinou, M.; Fubelli, G.; Giles, P.; Tsanakas, K.; Valkanou, K.; Batzakis, V.D.; Karalis, S. Classification of Trichonis Lake Graben (Western Greece) Alluvial Fans and Catchments Using Geomorphometry and Artificial Intelligence. Z. Geomorphol. 2022, 63, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.; Clews, J.E.; Melis, N.S.; Underhill, R. Structural Development of Neogene Basins in Western Greece. Basin Res. 1988, 1, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasakis, G.; Piper, D.J.W.; Tziavos, C. Sedimentological Response to Neotectonics and Sea-Level Change in a Delta-Fed, Complex Graben: Gulf of Amvrakikos, Western Greece. Mar. Geol. 2007, 236, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziavos, C. Oceanographic Survey and Palaeogeographic Evolution of the Amvrakikos Gulf. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Geology, University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mertzanis, A. Geomorphological Evolution of the Amvrakikos Gulf. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Therianos, A.D. The Geographical Distribution of River Water Supply in Greece. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 1974, 11, 28–58. [Google Scholar]

- Karalis, S.; Karymbalis, E.; Mamassis, N. Models foe sediment yield in mountainous Greek catchments. Geomorphology 2018, 322, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalis, S.; Karymbalis, E.; Tsanakas, K. Mid-Term Monitoring of Suspended Sediment Plumes of Greek Rivers Using Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) Imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulos, S.; Chronis, G. The Importance of the Greek River Systems in the Evolution of the Greek Coastline. In Transformations and Evolution of the Mediterranean Coastline; Briand, F., Maldonado, A., Eds.; CIESM Science Series; Bull Inst.: Oceanogr, Monaco, 1997; Volume 18, pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Poulos, S.E.; Collins, M.B.; Ke, X. Fluvial/Wave Interaction Controls on Delta Formation for Ephemeral Rivers Discharging into Microtidal Waters. Geo-Mar. Lett. 1993, 13, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Navy Hydrographic Service (HNHS). Statistical Data of Sea Level in Greek Ports, 2nd ed.; HNHS: Athens, Greece, 2015. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service (CMEMS). Mediterranean Sea Waves Reanalysis; Copernicus Marine Data 2025. Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/MEDSEA_MULTIYEAR_WAV_006_012/description (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Georgiou, N.; Fakiris, E.; Koutsikopoulos, C.; Papatheodorou, G.; Christodoulou, D.; Dimas, X.; Geraga, M.; Kapellonis, Z.G.; Vaziourakis, K.; Noti, A.; et al. Spatio-seasonal hypoxia/anoxia dynamics and sill circulation patterns linked to natural ventilation drivers in a Mediterranean landlocked embayment: Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece. Geosciences 2021, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutsinou-Taliadouri, F.; Balopoulos, E.T. Geochemical and Physical Oceanographic Aspects of the Amvrakikos Gulf (Ionian Sea, Greece). Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1991, 31–32, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, C.; Moutopoulos, D.K.; Gonzalvo, J.; Libralato, S. Ecosystem health of a Mediterranean semi-enclosed embayment (Amvrakikos Gulf, Greece): Assessing changes using a modeling approach. Cont. Shelf Res. 2016, 121, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovos, I.; Gonzalvo, J.; Ciprian, M.; Gaentlich, M.; Gavriel, E.; Konstas, S.; Kordopatis, P.; Koutsikopoulos, C.; Mavrogiorgos, D.; Moutopoulos, D.K.; et al. Amvrakikos Gulf: Biodiversity and Threats. Project “Contributing to the Effective Management of the Amvrakikos Gulf National Park”. Greece. 2023. Available online: https://isea.com.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Amvrakikos-Gulf-Biodiversity-Threats-Laymans-Report.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Riahi, K.; Ebi, K.L.; Hallegatte, S.; Carter, T.R.; Mathur, R.; van Vuuren, D.P. A New Scenario Framework for Climate Change Research: The Concept of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Clim. Change 2014, 122, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinshausen, M.; Nicholls, Z.R.; Lewis, J.; Gidden, M.J.; Vogel, E.; Freund, M.; Beyerle, U.; Gessner, C.; Naulls, A.; Bauer, N.; et al. The Shared Socio-Economic Pathway (SSP) Greenhouse Gas Concentrations and Their Extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 3571–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC AR6 Sea-level Projection Tool. Available online: https://sealevel.nasa.gov/data_tools/17 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Karymbalis, E.; Gaki-Papanastassiou, K.; Tsanakas, K.; Ferentinou, M. Geomorphology of the Pinios River delta, Greece. J. Maps 2016, 12, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.Y.; Wong, D.W. An adaptive inverse-distance weighting spatial interpolation technique. Comput. Geosci. 2008, 34, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]