Abstract

Floating offshore wind–wave hybrid systems, as a novel structural form integrating floating wind turbine foundations and WECs, can effectively enhance the efficiency of renewable energy utilization when properly designed. A numerical model is established to investigate the dynamic responses of a wind–wave hybrid system comprising a semi-submersible FOWT and PA wave energy converters. The optimal damping values of the PTO system for the wind–wave hybrid system are determined based on an NSGA-II. Subsequently, a comparative analysis of dynamic responses is carried out for the PTO system with different states: latching, fully released, and optimal damping. Under the same extreme irregular wave conditions, the pitch motion of the FOWT with optimal damping is reduced to 71% and 50% compared to the latching and fully released states, respectively. The maximum mooring line tension in the optimal damping state is similar to that in the fully released state, but nearly 40% lower than in the latching state. This optimal control strategy not only sustains power generation but also enhances structural stability and efficiency compared to traditional survival strategies, offering a promising approach for cost-effective offshore wind and wave energy utilization.

1. Introduction

With the ongoing advancement of clean energy systems, wind power has emerged as one of the most significant forms of renewable energy [1]. As the exploitation of onshore wind resources approaches saturation [2], offshore wind power, benefiting from abundant resource potential and favorable development conditions, demonstrates substantial prospects for future growth. By the end of 2024, the global cumulative installed capacity of offshore wind turbines had exceeded 83 GW [3]. However, high-quality nearshore wind resources are becoming increasingly scarce, and further development is limited by spatial competition with other maritime activities. Moreover, abundant and high-quality deep-sea wind energy resources are promoting the transition of wind power development from onshore to offshore, nearshore to deep water, and from fixed to floating foundations. Generally, the design concepts of traditional offshore oil and gas platforms have been applied to FOWT foundations. However, the additional DOF introduced by the motion responses of floating foundations increase the structural loads on components such as towers and blades, which significantly affects the fatigue life of FOWTs. In order to enhance stability and reduce loads, the integration of WECs with FOWT foundations is proposed, where restoring moments are provided to the foundations by the WECs. Furthermore, increased power generation can be achieved through the combination of multiple renewable energy devices by means of shared foundations, such as substructures and mooring systems, which thereby provide a viable pathway for reduction in the LCOE for WECs [4].

Floating offshore wind–wave hybrid systems, as a novel structural form, are still in the early stages of development [5]. Currently, various wind–wave hybrid system configurations have been proposed for different types of FOWT foundations. However, the optimal integration scheme has not yet been converged upon. Principle Power, in collaboration with the NREL, proposed the integration of OWCs, PAs, and pendulum-type WECs into the WindFloat FOWT, thereby forming a combined power generation platform known as a wind–wave hybrid system. The research results indicate that the wind–wave hybrid system can effectively reduce the motion responses of the floating platform, enhancing the stability of the FOWT [6]. As a result, important insights for further investigations have been provided. In subsequent research, various combinations of FOWTs and WECs have been primarily investigated. Specifically, the integration of Spar-type foundations with PAs [7], tension-leg foundations with PAs [8] semi-submersible platforms coupled with PAs [9,10] or Oscillating Wave Surge Converters [11], and semi-submersible platforms combined with OWCs [12], have been examined. Among these conceptual designs, integration with PAs has been most extensively adopted in wind–wave hybrid systems owing to its simple integration method and compact structure, which do not require outward extension or alteration of the original FOWT foundation design.

Regarding the motion response control of wind–wave hybrid systems integrated with PAs, the traditional control strategies of a power take-off PTO system are not suitable choices for the hybrid system. A parametric study of the size and number of PAs, as well as the PTO damping coefficient, was conducted by Ghafari et al. [10]. It was demonstrated that, through appropriate design of WECs, both optimization of energy capture and stabilization of hybrid system motion response can be achieved. Multi-objective optimization of the PTO system in a hybrid system were evaluated by Huang et al. [13] under normal operating mode, and effective suppression of the hybrid system motion response was achieved. A comparative study of various control strategies for the PTO system in hybrid systems was carried out by Si et al. [14], with an evaluation of their performance, limitations, and corresponding recommendations for optimal selection. Research on survival strategies for wind–wave hybrid systems under extreme conditions remains limited. REN et al. [15] carried out a comparative analysis of survival performance under various control strategies, and proposed a novel low-damping survival strategy, which proved effective in motion response suppression. However, regarding this approach, the determination of the optimal damping value of the PTO system remains an open issue.

Accordingly, a floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system, combining a semi-submersible FOWT with point-absorber WECs, is selected as the research object. The dynamic response characteristics of the hybrid system under survival mode are systematically analyzed. Based on the NSGA-II, the optimal PTO damping of the hybrid system under extreme conditions is determined, aiming to achieve effective suppression of dynamic responses and thereby enhance the structural survivability. The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, the structural configuration of the proposed hybrid system is presented and the numerical model is established. In Section 3, several operational modes of the hybrid system under extreme conditions are briefly introduced. Finally, in Section 4, the optimal damping of PTO system is determined based on the NSGA-II algorithm, and then the performance of the hybrid system is evaluated.

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Design of the Hybrid System

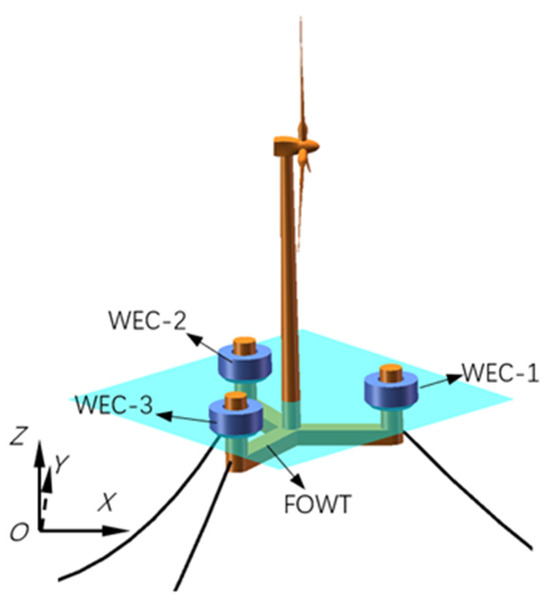

As shown in Figure 1, the floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system proposed in this paper is designed on the basis of a semi-submersible FOWT [16] equipped with the DTU 10 MW wind turbine [17], with oscillating buoy WECs [18] installed on the three outer columns of the FOWT foundation. The buoys are connected to the FOWT foundation columns through PTO systems, restricting the movement of the WECs to along the axial direction of the columns only. The specific design parameters of the hybrid system are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system.

Table 1.

Main parameters of the hybrid system.

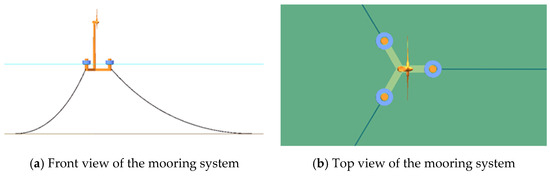

The floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system is operated at a water depth of 200 m. A catenary mooring system is employed, in which one anchor chain is connected to each of the three side columns of the FOWT foundation with 120-degree intervals. The material damping ratio is set to 0.8. Each anchor chain is designed with a length of 880 m and a diameter of 0.153 m, and a submerged mass per unit length of 0.447 t/m is considered. The axial stiffness is specified as 2.1 × 106 kN. The mooring system arrangement is illustrated in Figure 2 and Table 2.

Figure 2.

Arrangement of the mooring lines.

Table 2.

Preliminary mooring system properties.

2.2. Dynamics Model of the Hybrid System

In the numerical model, the FOWT foundation and the three WECs are regarded as separate rigid bodies, which are interconnected through the PTO system. Based on the assumption of the ideal fluid and the potential flow theory, the coupled dynamic model of the hybrid system can be established as a multi-body formulation of Cummins equation [19]. Accordingly, the time domain model of the hybrid system is governed as follows:

where the index i corresponds to WECs when i = 1, 2, 3, and to the FOWT when i = 4. denotes the mass of each floater i; is the added mass and is the retardation function; , , are the displacement, velocity, and acceleration, respectively; is the hydrostatic stiffness matrix; is the viscous damping coefficient; denotes the wave forces derived from the incident and diffraction wave potentials; and are the wind force and current force, respectively; is the mooring force; and represents the constraint-induced interaction forces between different floaters as well as the PTO forces.

The numerical model is established based on ANSYS AQWA (version number 2022R1) and the open-source WEC-Sim [20] toolbox. The frequency-domain hydrodynamic parameters, including added mass, radiation damping, hydrostatic stiffness, and first-order and second-order wave forces, are obtained through frequency-domain calculations from ANSYS AQWA. Viscous force is accounted for by applying an additional viscous damping coefficient as a correction. The wind force acting on the hybrid system is primarily from the turbine blades and could equivalently be calculated using the thrust curve of the DTU 10 MW wind turbine. The numerical model of the mooring system is formulated based on the lumped mass method and simulated using the open-source tool Moordyn. The PTO system is simplified as a spring-damper model and the constraints between floaters are implemented through the Prismatic Joint module of the WEC-Sim toolbox. This module is primarily designed to model linear motion constraints in multibody systems, restricting the relative motion between two rigid bodies to translation along a single axis, while preventing any rotation about all axes. It also allows for the flexible configuration of physical parameters such as displacement limits and friction coefficients.

3. Survival Modes

Under extreme survival modes, the wind speed usually exceeds the turbine cut-out speed, at which point the wind turbine generator is typically shut down. In this situation, the PTO system of the floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system can generally be set to one of the following three states to ensure safety:

- (1)

- Locked mode: The WECs do not generate power and are mechanically locked to remain relatively stationary with respect to the FOWT foundation. In numerical simulations, the floating offshore wind–wave hybrid system is modeled as a single rigid body. Two locking modes could be employed for the WECs: one locked directly at the still water equilibrium position; alternatively, the device may be ballasted and fully submerged. However, the latter approach may result in wave impacts on the wind turbine blades [15].

- (2)

- Free-released mode: The WECs are deactivated from power generation and permitted to move freely along the axial direction of the FOWT foundation’s column. In this condition, the PTO damping coefficient is set to zero.

- (3)

- Low damping mode: The WECs remain in the power generation state. No standardized approach has been defined for the selection of PTO damping coefficients. Consequently, the values of the PTO damping for each WECs within the hybrid system are optimized through the application of the NSGA-II algorithm in this paper.

4. Multi-Objective Optimization of PTO Damping Coefficient

4.1. NSGA-II

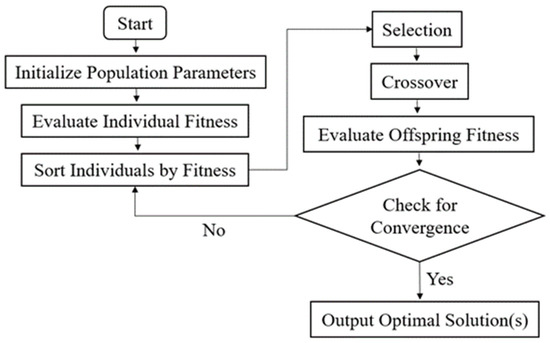

The NSGA-II algorithm, a multi-objective optimization method based on genetic algorithms, was first proposed by Deb et al. [21]. Due to the adoption of a fast non-dominated sorting approach, the computational complexity has been significantly reduced, resulting in an improved execution speed of the algorithm. Furthermore, the incorporation of a crowding distance comparison operator broadens the search space, which leads to a more uniform distribution of the generated solutions along the Pareto front, thereby enhancing the robustness of the algorithm. The flowchart of the NSGA-II algorithm is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the optimization algorithm.

4.2. Objective Function and Constraints

For wind–wave hybrid systems, the values of damping in the PTO system have a significant impact on the overall dynamic response and power generation efficiency of the entire system. Meanwhile, as a multi-body system, the wind–wave hybrid system is characterized by complex coupling interactions among its components under the combined action of wind, waves, and currents. Consequently, the control of the PTO system of a single WEC in isolation is regarded as ineffective. Therefore, the PTO systems of all three WECs are simultaneously controlled, and the optimal value of the PTO damping under extreme conditions is determined using the NSGA-II algorithm.

It is noteworthy that higher stability requirements are imposed on the pitch motion of FOWT foundations. Therefore, during the determination of the PTO damping values, emphasis should be placed on reducing the pitch motion of the FOWT foundations while ensuring power generation efficiency. Consequently, when solving this optimization problem, the motion response of the pitch of the FOWT foundations and the power generation of the WECs are adopted as objective functions for multi-objective optimization. The specific objective functions are presented as Equations (2) and (3).

where is the pitch motion of the FOWT and is the generation output of all WECs over a certain time period, calculated as follows:

where Tc is the duration of the numerical simulation and is the instantaneous power generation output of a single WEC, calculated as follows:

where is the relative velocity between the buoy and offset column and is the damping value of each PTO system.

Due to the fact that different WECs correspond to different optimal damping values, the damping coefficients of the three WECs are all treated as optimization variables. Additionally, in order to prevent excessive motion response of the WECs under survival mode while ensuring that power generation is maintained, the amplitude of the motion response is constrained not to exceed an upper limit of 5 m to avoid collisions between the buoy and the pontoon. The velocity upper limit is set to 3 m/s based on empirical estimation, as the PTO system similarly requires the avoidance of excessively rapid responses. The maximum PTO damping value is chosen to be twice the optimal damping under rated operating conditions for power generation. At this high damping level, the relative motion between the buoy and the FOWT foundation is effectively eliminated.

Therefore, additional constraints are imposed, as formulated in Equation (6).

The values of the genetic algorithm parameters are set as follows: the population size is assigned a value of 10, the maximum number of generations is limited to 100, and the crossover probability and mutation probability are set to 0.8 and 0.08, respectively.

4.3. Pareto Solutions

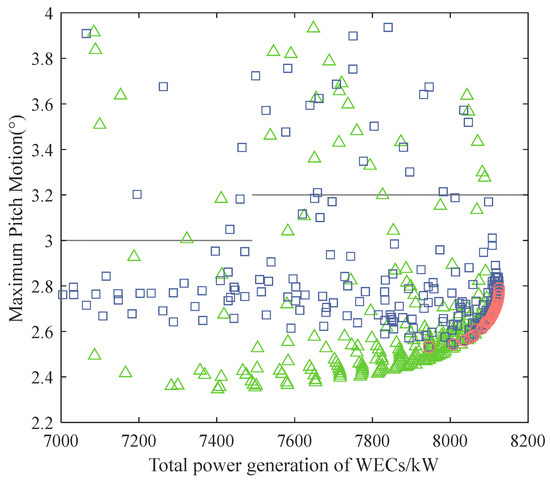

The extreme condition is selected based on the 50-year return period scenario at the Norway site 5, which is commonly used for the design of FOWT foundations. The significant wave height is taken as 15.6 m and the peak period as 14.5 s, with waves incident from a 0° direction. The wind speed is set at 40 m/s, and the wind–wave angle was 0°. The Pareto solution set is obtained through the NSGA-II genetic algorithm. The optimization results are illustrated in Figure 4, where red circles represent Pareto-optimal solutions, blue diamonds denote feasible solutions, and green triangles indicate solutions that violate the constraint conditions. A subset of the Pareto-optimal solutions is presented in Table 3, with the results sorted in descending order according to the total power output of the wave energy devices.

Figure 4.

Pareto optimal solution set.

Table 3.

Subset of Pareto-optimal solutions.

Following an evaluation of the trade-off between power generation efficiency and stability of the hybrid system, the damping values associated with the seventh Pareto-optimal solution are chosen as the PTO damping parameters for the WECs in the low-damping mode.

4.4. Performance Assessment

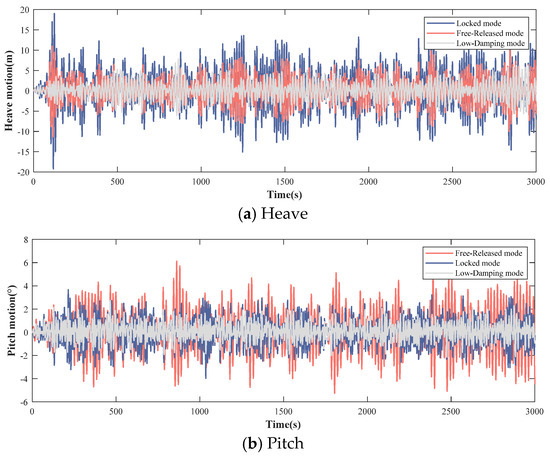

A comparative analysis has been conducted on the dynamic responses of hybrid systems with three distinct survival modes under extreme conditions. The motion responses of the FOWT under different survival modes are shown in Figure 5, while the statistical values of the motion responses are presented in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Motion responses of FOWT foundations with different survival modes.

Table 4.

The statistical values of the motion response of FOWT foundations.

As there is no relative motion between the FOWT foundation and the WECs in the locked mode, the subsequent analysis is confined to the relative motion characteristics between the FOWT foundation and the WECs under the free-released mode and the low-damping mode. The relative motion responses between the WECs and the FOWT foundation under the two survival modes are presented in Figure 5. The statistical values of these responses are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

The statistical values of the relative motion response of WECs.

It can be observed from Figure 5 and Table 4 that, among the three survival modes, the maximum relative pitch motion of the wind–wave hybrid system is lowest in the low-damping mode. The pitch motion in the low-damping mode is approximately 71% of that in the locked mode and 50% of that in the free-released mode. In the free-released mode, the FOWT demonstrates the minimum heave motion, albeit accompanied by a relatively large pitch motion. In contrast, the heave motion is highest in the locked mode.

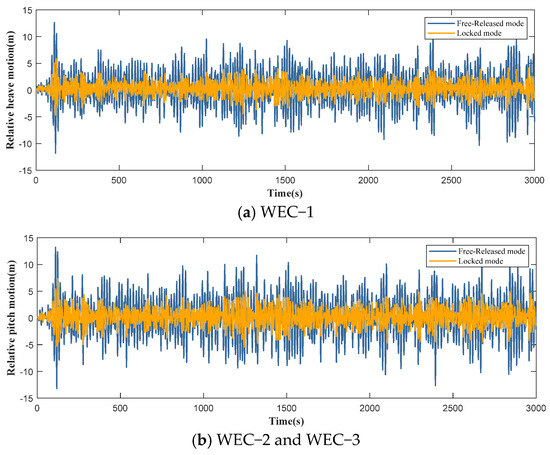

As illustrated in Figure 6 and Table 5, since the waves are incident from 0° and the hybrid system exhibits a symmetric structure, the motion responses of WEC-2 and WEC-3, as well as the mooring tensions of Mooring Line-2 and Line-3, are almost the same. Meanwhile, the relative motion between the WECs and the FOWT foundations under the free-released mode is considerably large. Therefore, a risk of collision between the WECs and the pontoons of the FOWT foundation is introduced. In contrast, under the low-damping mode, the relative motion responses are significantly suppressed due to the PTO damping, whereby the maximum motion response of WEC-1 is reduced to 65% of that observed in the free-released mode, and that of WEC-2 is decreased to 42%. As a result, the relative motion between the WECs and the FOWT foundation is effectively diminished, thereby mitigating the risk of collision between the pontoons and the WECs.

Figure 6.

The relative motion response of WECs with different survival modes.

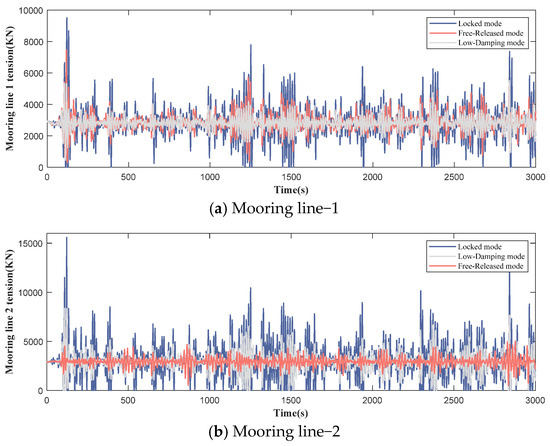

Meanwhile, the overall structural safety has been assessed through statistical analysis of the tension data recorded at the mooring fairleads. The mooring line tensions at different fairleads are presented in Figure 7, while the statistical values corresponding to various survival modes are summarized in Table 6.

Figure 7.

The mooring line tension at different fairleads with different survival modes.

Table 6.

The characteristic values of mooring line tension at different fairleads.

Compared to the free-released mode, where the mooring line tensions are minimal, the amplitude and standard deviation of tension in mooring line 1 remain nearly unchanged under the low-damping mode. Meanwhile, the maximum tensions in mooring lines 2 and 3 increase by about 1.5 times. Compared with the locked mode, which produces the highest mooring tensions, the maximum tension in mooring line 1 under the low-damping mode is reduced by 25.1%, with mooring lines 2 and 3 experiencing reductions of 39.5%.

Regarding the motion performance of the hybrid system, the free-released mode results in the optimal heave motion characteristics of the FOWT foundation, although this advantage is offset by a less favorable pitch response. Due to the free movement of the buoy, significant relative displacement between the WECs and the pontoon at the base of the FOWT foundation is observed under extreme conditions, which may lead to collision risks. Under the low-damping mode, a deterioration in heave motion is observed, but the pitch response is significantly improved. Furthermore, the additional PTO damping effectively suppresses the motion response of the buoy, thereby mitigating the risk of collision between the WECs and the pontoon.

In terms of mooring line tensions, the minimum tensions are recorded under the free-released mode, followed by the low-damping mode, where only mooring lines 2 and 3 show slight increased tensions. The locked mode, on the other hand, results in the highest mooring tensions, imposing more stringent requirements on the mooring system design. With respect to power generation, the WECs remain operational under the low-damping mode, producing a combined average power output of up to 8 MW under extreme conditions, thus ensuring continuous electricity supply from the wind–wave hybrid system.

5. Conclusions

The present study focuses on the integrated wind–wave power generation system. A multi-objective optimization of the PTO damping for each WEC is conducted under extreme conditions based on the NSGA-II. Optimal damping values for the PTO system are thus obtained. By comparison with the initial design, the following conclusions are drawn:

- (1)

- A method for determining the optimal PTO damping of WECs is proposed, based on a time-domain dynamic model coupled with a multi-objective genetic algorithm. This method provides a feasible approach for specifying the PTO damping of wind–wave hybrid systems under low-damping modes in extreme environments.

- (2)

- The dynamic response characteristics of the wind–wave hybrid system are systematically compared under three survival modes. It is found that the low-damping mode can effectively reduce the pitch motion of the FOWT foundation within the hybrid system. Although slight increases are observed in heave motion and mooring line tensions compared to the free-released mode without PTO damping, the effective suppression of relative heave motion of the WECs significantly reduces the risk of collision between the buoy and the FOWT foundation pontoon, while maintaining a high level of power generation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y. and D.Q.; Methodology, S.Y. and D.Q.; Software, F.Z.; Validation, F.Z.; Formal analysis, X.W.; Investigation, S.Z.; Resources, S.Y. and D.Q.; Data curation, X.W. and F.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; Supervision, S.Y. and D.Q.; Project administration, S.Y.; Funding acquisition: D.Q.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Projects of Liaoning Province [Grant No. 2023011352–JH1/110].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Suchun Yang was employed by the company PowerChina Beijing Engineering Corporation Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WECs | Wave Energy Converters |

| PA | Point-Absorbing |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| OWC | Oscillating Water Column |

| FOWT | Floating Offshore Wind Turbine |

| PTO | Power Take-off |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

The following symbols and units are used in this manuscript:

| M | Mass | kg |

| A | Added Mass | kg |

| D | Viscous Damping Coefficient | Ns/m |

| K | Retardation Function | N/m |

| F | Forces | N |

| P | Power | W |

| CPTO | PTO Damping | Ns/m |

| η | Displacement | m |

References

- Guo, J.; Han, B.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, B.; Guo, M.; He, B. Research on the strain response of offshore wind turbine monopile foundation through integrated fluid-structure-seabed model test. Ocean Eng. 2024, 314, 119729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Physics-constrained wind power forecasting aligned with probability distributions for noise-resilient deep learning. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, S.; Musial, W.; Jonkman, J.; Wayman, L. Engineering Challenges for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines; Technical Report; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Da-Silva, L.S.P.; Sergiienko, N.Y.; Cazzolato, B.; Ding, B. Dynamics of hybrid offshore renewable energy platforms: Heaving point absorbers connected to a semi-submersible floating offshore wind turbine. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 1424–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Collazo, C.; Greaves, D.; Iglesias, G. A review of combined wave and offshore wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.; Roddier, D.; Banister, K. Wind Wave Float (WWF): Final Scientific Report; Principle Power Inc.: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Muliawan, M.J.; Karimirad, M.; Moan, T.; Zhen, G. STC (Spar-Torus Combination): A combined spar-type floating wind turbine and large point absorber floating wave energy converter-promising and challenging. In Proceedings of the ASME 2012 31st International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1–6 July 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, N.; Wu, H.; Liu, K.; Zhuo, D.; Ou, J. Hydrodynamic analysis of a modular floating structure with tension-leg platforms and wave energy converters. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Yi, Y.; Zheng, X.; Cui, L.; Zhao, C.; Liu, M.; Rao, X. Experimental investigation of semi-submersible platform combined with point-absorber array. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafari, H.R.; Ghassemi, H.; Neisi, A. Power matrix and dynamic response of the hybrid Wavestar-DeepCwind platform under different diameters and regular wave conditions. Ocean Eng. 2022, 247, 110734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Michailides, C.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T. Modeling and analysis of a 5 MW semi-submersible wind turbine combined with three flap-type wave energy converters. In Proceedings of the ASME 2014 33rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–13 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento, J.; Iturrioz, A.; Ayllón, V.; Guanche, R.; Losada, I.J. Experimental modelling of a multi-use floating platform for wave and wind energy harvesting. Ocean Eng. 2019, 173, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, M.; Dong, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Parameter analysis and dual-objective optimization of the hydraulic power take-off system of a floating wind-wave hybrid system. Ocean Eng. 2024, 307, 118058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Ma, X.; Qian, P. The influence of power-take-off control on the dynamic response and power output of combined semi-submersible floating wind turbine and point-absorber wave energy converters. Ocean Eng. 2021, 227, 108835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T.; Wan, L. Long-term performance estimation of the spar-torus-combination (STC) system with different survival modes. Ocean Eng. 2015, 108, 716–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Design of a Steel Pontoon-Type Semi-Submersible Floater Supporting the DTU 10MW Reference Turbine. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, C.; Zahle, F.; Bitsche, R.; Kim, T.; Yde, A.; Henrikesen, L.C.; Hansen, M.H.; Gaunaa, M.; Natarajan, A. The DTU 10-MW reference wind turbine. In Proceedings of the Danish Wind Power Research 2013, Fredericia, Denmark, 27–28 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Muliawan, M.J.; Gao, Z.; Moan, T.; Babarit, A. Analysis of a two-body floating wave energy converter with particular focus on the effects of power take-off and mooring systems on energy capture. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2013, 135, 031902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, W.E. The Impulse Response Function and Ship Motions. Schiffstechnik 1962, 9, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, D.; Ruehl, K.; Yu, Y.H. Review of WEC-Sim development and applications. Int. Mar. Energy J. 2022, 5, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).