Abstract

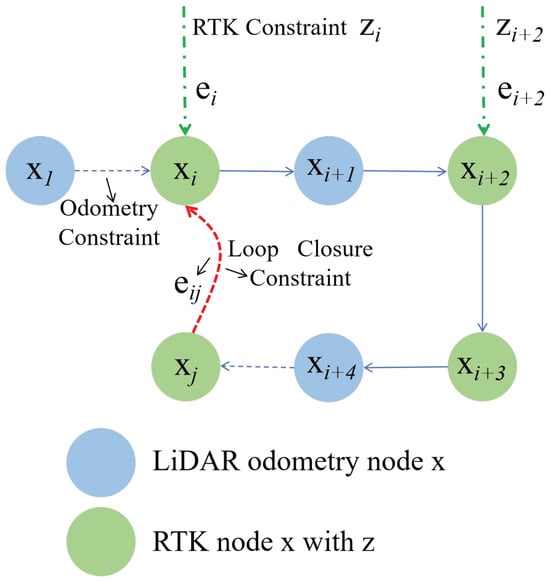

Autonomous berthing of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) requires high-precision positioning and accurate detection of navigable region in complex port environments. This paper presents an integrated LiDAR-based approach to address these challenges. A high-precision 3D point cloud map of the berth is first constructed by fusing LiDAR data with real-time kinematic (RTK) measurements. USV pose is then estimated by matching real-time LiDAR scans to the prior map, achieving robust, RTK-independent localization. For safe navigation, a novel navigable region detection algorithm is proposed, which combines point cloud projection, inner-boundary extraction, and target clustering. This method accurately identifies quay walls and obstacles, generating reliable navigable areas and ensuring collision-free berthing. Field experiments conducted in Ling Shui Port, Dalian, China, validate the proposed approach. Results show that the map-based positioning reduces absolute trajectory error (ATE) by 55.29% and relative trajectory error (RTE) by 38.71% compared to scan matching, while the navigable region detection algorithm provides precise and stable navigable regions. These outcomes demonstrate the effectiveness and practical applicability of the proposed method for autonomous USV berthing.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

With the continuous advancement of unmanned surface vehicle (USV) technology, their applications in maritime tasks such as hydrographic surveying, environmental monitoring, maritime security patrols, and search-and-rescue operations are rapidly expanding, bringing significant improvements in operational efficiency and safety assurance [1,2,3,4]. A core capability for enabling fully autonomous USVs is autonomous berthing, which refers to the complex process of safely and precisely maneuvering a USV to dock at a quay or harbor [5]. Although substantial progress has been achieved in USV navigation within open waters, autonomous berthing remains a formidable challenge due to its stringent requirements for centimeter-level accuracy, real-time responsiveness, and robust perception in cluttered near-shore environments [6].

Existing approaches typically address these challenges in isolation. Positioning methods based on Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) are vulnerable to signal blockage and multipath interference [7,8]. Vision-based approaches employing onboard cameras can provide rich environmental information but are highly sensitive to illumination conditions and require large-scale training datasets to overcome the ambiguities of the water surface [9]. Conventional marine radars, while effective over long ranges, lack the high resolution needed for fine-grained maneuvering in close-range operations [10]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a sensing solution that can simultaneously provide high resolution and all-weather capability in berthing scenarios.

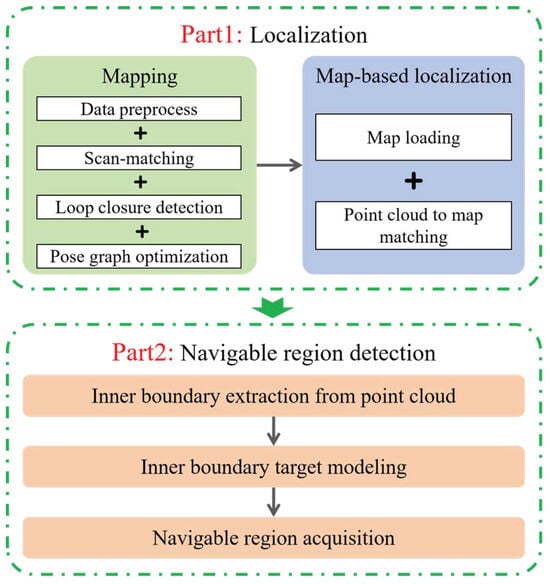

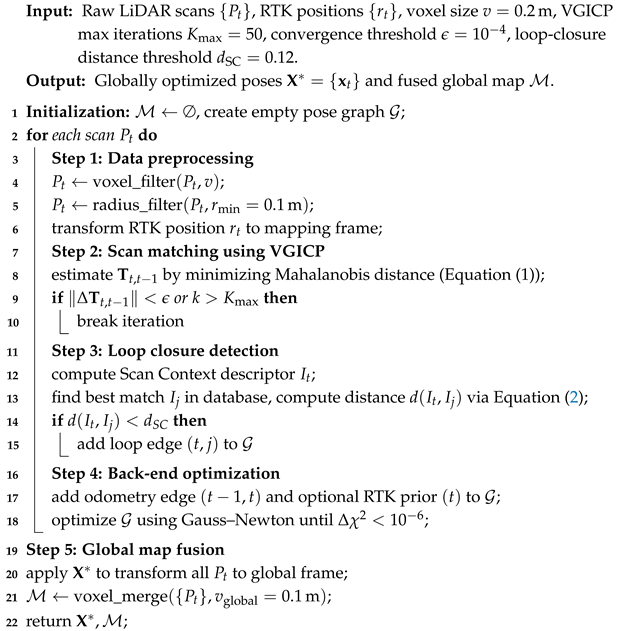

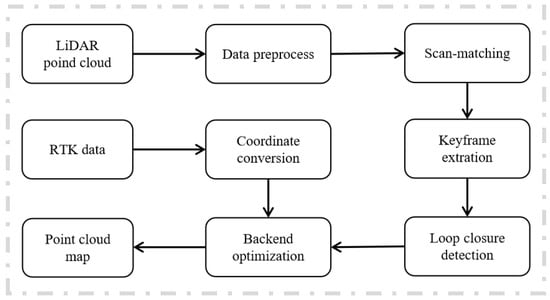

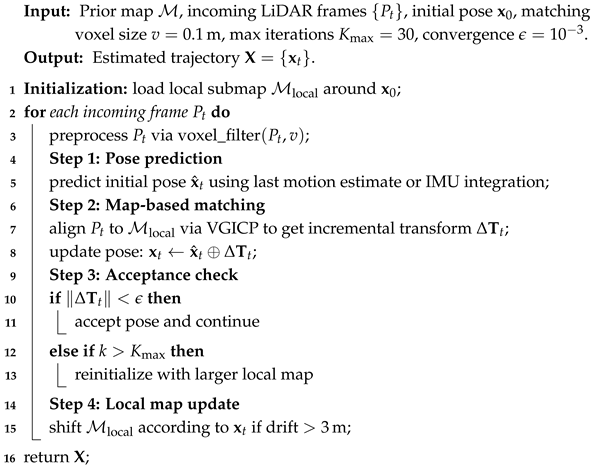

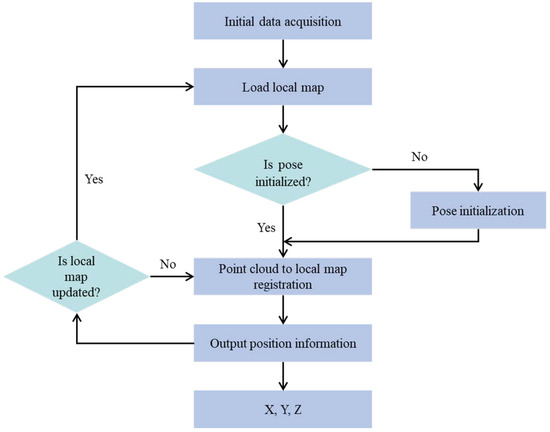

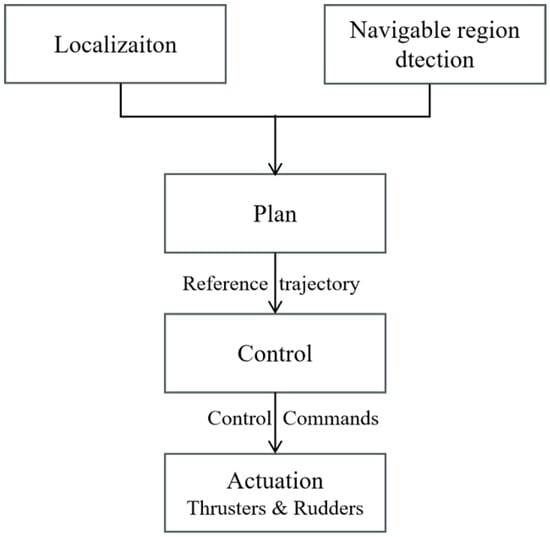

To address this issue, this paper proposes an integrated framework that employs a vessel-mounted 3D LiDAR as the primary sensor to support both localization and navigable region detection during USV autonomous berthing. LiDAR is inherently robust to illumination variations and can generate centimeter-level 3D point clouds, effectively overcoming the limitations of conventional cameras in maritime environments. Based on LiDAR point clouds, two synergistic tasks are realized. First, localization is achieved by registering real-time LiDAR scans with a pre-constructed 3D berth map, enabling robust and high-precision localization without reliance on GNSS. Second, navigable region detection is accomplished through a novel point cloud processing and obstacle segmentation algorithm, which identifies water surfaces and obstacles to construct safe navigable regions in real time, thereby providing reliable support for USV berthing.

1.2. Related Work

Accurate and reliable localization is a prerequisite for autonomous berthing of USVs. Conventional approaches primarily rely on the GNSS, often enhanced with real-time kinematic (RTK) carrier-phase differential techniques to achieve centimeter-level accuracy [11,12]. However, in crowded ports, under bridges, or near large infrastructures, GNSS signals are highly susceptible to blockage, leading to significant degradation in localization performance [13]. To address this limitation, researchers have explored various alternative solutions.

Vision-based localization methods that employ cameras with artificial markers or natural features have been proposed for short-range navigation [14,15]. While effective under favorable lighting conditions, their performance deteriorates severely at night, in rain or fog, or due to water surface reflections. LiDAR-based localization, particularly through LOAM and its variants, has demonstrated remarkable success in land-based autonomous driving applications [16,17,18]. In the maritime domain, some studies have investigated frame-to-frame LiDAR scan matching algorithms for position estimation [19,20]. However, these methods suffer from error accumulation, making them suitable only for short-range localization, with limited accuracy over extended distances.

In parallel with localization, navigable region detection is another critical component for USV autonomous berthing [21,22]. Existing studies can generally be categorized into two groups. The first group analyzes spatial variations in point cloud data to extract channel boundaries or employs curve-fitting techniques to reconstruct waterway lines [23,24]. The second group emphasizes quay wall detection through object recognition, followed by inferring navigable areas based on the distribution of detected quay structures [25,26].

Nevertheless, most of these studies have focused on relatively structured inland waterways, while the unique challenges of port berthing scenarios have received insufficient attention. Compared with inland rivers, port environments are significantly more complex, containing static obstacles such as quay infrastructures and moored vessels, as well as dynamic elements including moving ships and surface disturbances. These factors impose stricter requirements on the accuracy, robustness, and real-time capability of navigable region detection.

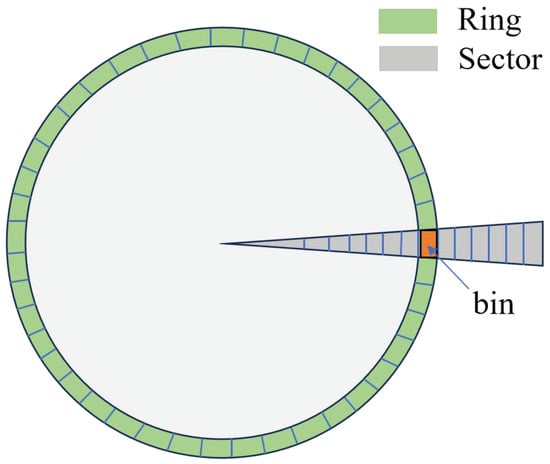

In summary, although significant progress has been made in USV localization and environmental perception, there remains a lack of integrated solutions that can simultaneously address both challenges in demanding berthing scenarios. Existing LiDAR-based approaches typically treat localization and perception as independent tasks. For example, SLAM systems often focus on map construction without actively supporting real-time obstacle avoidance, while perception modules generally assume fully known USV poses. To overcome this gap, this paper proposes a unified framework based on a single 3D LiDAR sensor. The framework enables robust map-based localization in GNSS-denied environments and simultaneously achieves real-time, high-precision detection of navigable waters and obstacles, thereby providing comprehensive support for autonomous berthing.

1.3. Contributions

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

(1) A unified LiDAR-based system framework is proposed to simultaneously address high-precision pose localization and navigable region detection during USV berthing, thereby avoiding the complexity of multi-sensor fusion.

(2) A map-based localization strategy is developed, which registers real-time point clouds with a prior berth map to provide accurate position estimates in GNSS-denied or signal-degraded environments, ensuring reliable support for autonomous berthing.

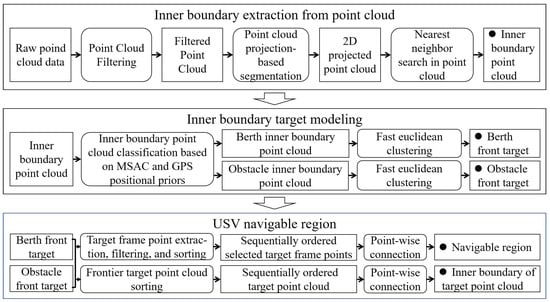

(3) A novel navigable water detection algorithm is designed, which integrates point cloud projection, inner-boundary extraction, and target clustering to accurately distinguish quay walls from obstacles and generate safe navigable regions.

(4) Full-scale field experiments are conducted to validate the proposed method. Results demonstrate that the system achieves high accuracy and robustness in complex berthing environments, providing stable and reliable information for autonomous berthing operations.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the overall framework of the proposed system, focusing on LiDAR-based localization and navigable region detection. Section 3 describes the experimental design and implementation, followed by detailed analysis of the results. Section 4 discusses the advantages, limitations, and potential applications of the proposed method. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and summarizes the main research contributions.

3. Verification Experiment

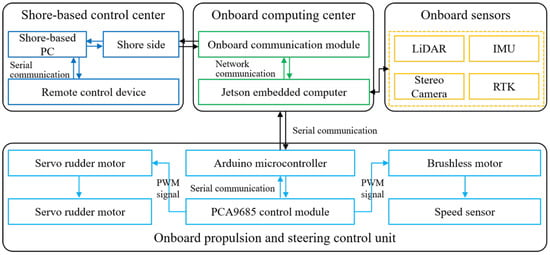

Field experiments were conducted at Lingshui Port, Dalian, China (latitude: 38°52′18.2″, longitude: 121°32′42″), as shown in Figure 13. The USV used in the experiments was Zhilong-1, with a length of 1.75 m and a width of 0.5 m. To enhance navigation stability, the hull was equipped with anti-rolling devices on both sides. The onboard sensor suite included an R-Fans-16 LiDAR (R-Fans, Shanghai, China), an RTK system (Shanghai South Surveying & Mapping Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and a stereo camera (ZED, Stereolabs, Shanghai, China). The R-Fans-16 LiDAR provides a 360° horizontal field of view, a 30° vertical field of view, and a maximum ranging distance of 200 m. Other key parameters are listed in Table 1. The experimental hardware platform was equipped with an Intel Core i5-4570 processor, 16 GB of RAM, and an NVIDIA GeForce GTX1650 GPU. The software system was implemented in C++17 and operated within the ROS framework.

Figure 13.

Harbor experiment of the “Zhilong I” USV.

Table 1.

LiDAR data specifications.

To evaluate system performance, two sets of experiments were designed: localization experiments and navigable region detection experiments.

3.1. Localization Experiment

In the localization experiment, the operator manually controlled the USV to complete a full navigation loop within the port to verify the accuracy and reliability of the proposed localization algorithm.

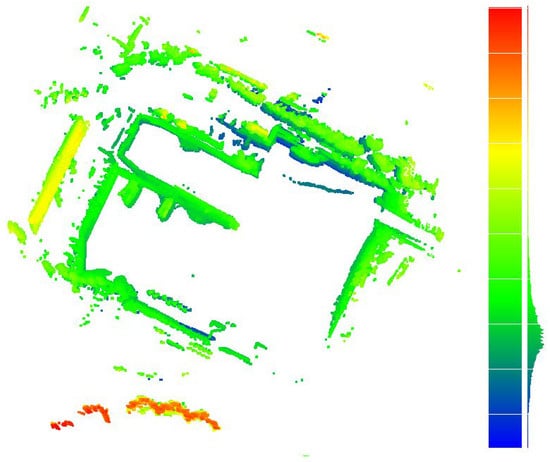

Figure 14 presents a top-down view of the point cloud map generated by the algorithm. The point cloud is color-coded to represent different elevation levels, providing both intuitive and practical visualization. The blue regions correspond to low-lying areas near the water surface; the green areas represent the port frontage and berths; the yellow tones indicate medium-height port facilities and low-rise buildings; while the orange-red areas mark the tallest structures. This color gradient enables clear differentiation of targets at varying heights and enhances the overall visualization quality of the map.

Figure 14.

Point cloud map generated by the mapping algorithm.

As shown in the figure, the generated point cloud map exhibits no ghosting or distortion. The port contours and building structures maintain good verticality and structural completeness, with fine details accurately represented. These results demonstrate that the proposed fusion algorithm achieves high precision in both data processing and map construction, effectively capturing the three-dimensional structure of the port environment. Overall, the point cloud map shows well-defined layers and clear structural features, confirming the reliability and effectiveness of the proposed mapping algorithm.

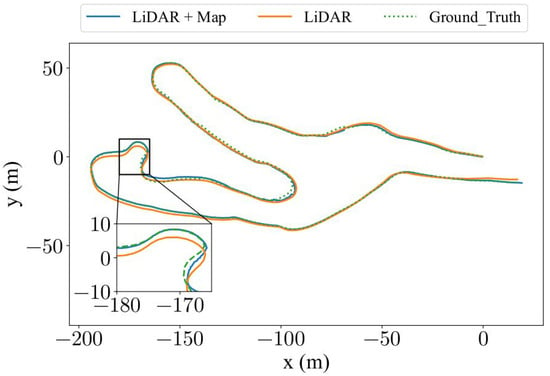

Figure 15 illustrates the trajectories obtained during the USV’s navigation within the port using two different localization methods: prior-map-based localization and frame-to-frame scan matching. These trajectories are compared against the actual navigation path. Overall, both methods exhibit good agreement with the ground truth trajectory; however, notable differences can be observed in their detailed performance.

Figure 15.

Trajectory comparison obtained using two different matching methods.

The trajectory derived from LiDAR scan matching primarily depends on real-time registration between consecutive point clouds and the surrounding environment to estimate the USV’s pose. While this method provides reasonably accurate localization results, its precision is constrained by factors such as environmental noise, dynamic object interference, and the inherent uncertainty of scanning data.

In contrast, the trajectory obtained through LiDAR matching with a prior map demonstrates a closer alignment with the actual navigation path. The prior map is preconstructed using high-precision measurement techniques, allowing real-time point clouds to be matched against a stable reference environment. This effectively mitigates the effects of environmental noise and dynamic disturbances, thereby enhancing localization accuracy. As shown in the magnified view, the trajectory obtained from prior-map matching exhibits a significantly higher degree of consistency with the actual path, clearly validating the crucial role of prior maps in improving localization precision.

To quantitatively assess the localization performance, two standard trajectory error metrics were employed: Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) and Relative Trajectory Error (RTE).

The ATE measures the global consistency of the estimated trajectory with respect to the ground truth and is defined as

where and represent the estimated and ground-truth positions at timestamp i, and N denotes the total number of trajectory samples.

The RTE evaluates the short-term drift and local consistency between consecutive poses, and is calculated as

where denotes the time interval for relative comparison and M is the number of valid pose pairs.

Both ATE and RTE were evaluated using root mean square error (RMSE), mean, and median to provide a comprehensive assessment of localization accuracy. The ground-truth trajectory was derived from RTK-GNSS measurements, and all estimated trajectories were aligned to the ground-truth frame via a rigid-body transformation prior to error computation.

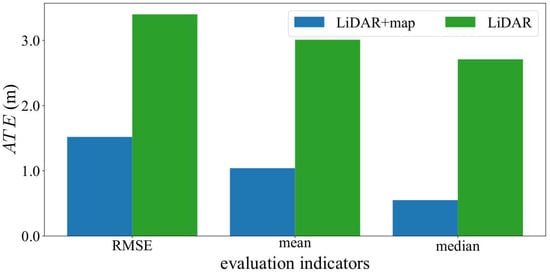

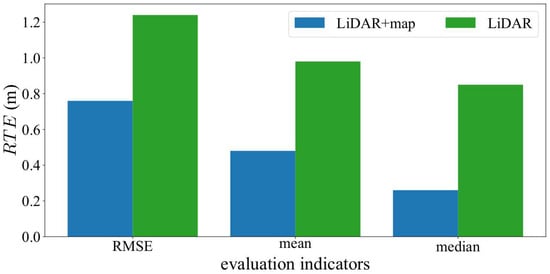

Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the comparative results of the two matching methods in terms of ATE and RTE, respectively, under the three evaluation indicators (RMSE, mean, and median). For ATE, the trajectory obtained through the LiDAR-to-prior-map matching approach exhibits substantially smaller errors in all directions compared with the LiDAR scan matching method. Similarly, for RTE, the prior-map-based matching consistently achieves lower errors, demonstrating its superiority in both local and global trajectory accuracy.

Figure 16.

Comparison of ATEs obtained from the two different matching methods.

Figure 17.

Comparison of RTEs obtained from the two different matching methods.

Quantitatively, the RMSE of the ATE for the LiDAR-to-prior-map matching method is reduced by 55.29% compared with that of the LiDAR scan matching approach, highlighting the crucial role of the prior map in enhancing global localization accuracy. Furthermore, the RTE RMSE decreases by 38.71%, indicating improved short-term consistency and smoother local motion estimation.

In summary, these experimental results clearly verify the effectiveness and robustness of the LiDAR-to-prior-map matching strategy. By integrating prior map information with real-time LiDAR scans, the proposed method achieves more accurate, stable, and consistent localization performance, offering a reliable solution for high-precision navigation of unmanned surface vessels in complex maritime environments.

3.2. Navigable Region Detection Experiment

In the navigable region experiment, the operator controlled the USV to navigate within the berth and its surrounding area to simulate operational scenarios under realistic berthing conditions. The experiment utilized real-time data acquisition from the vessel-mounted LiDAR sensor to perceive and analyze the surrounding region, aiming to verify the accuracy and stability of the proposed navigable region detection algorithm.

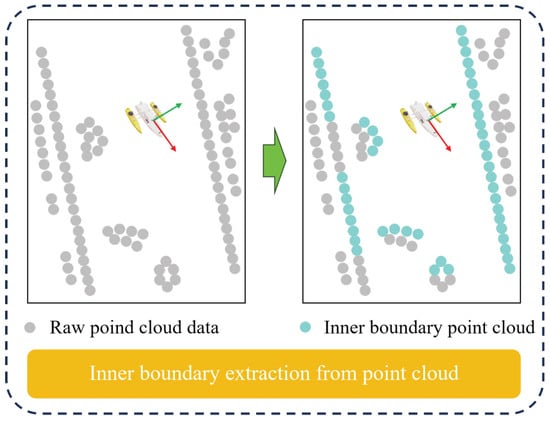

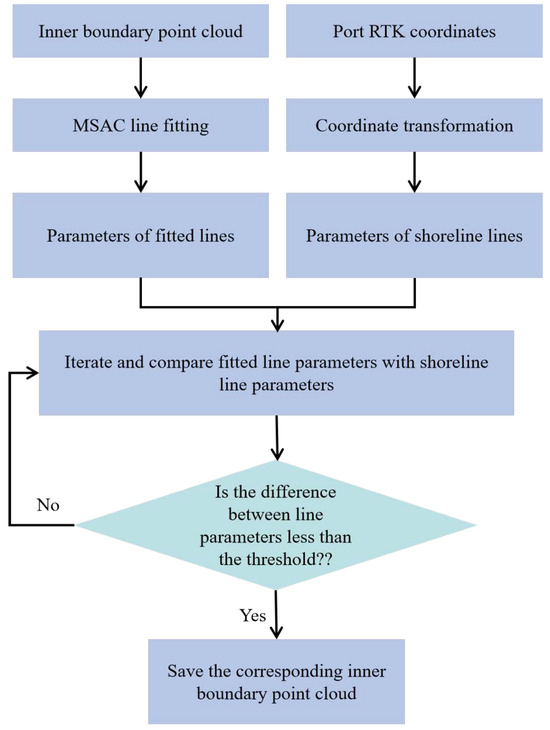

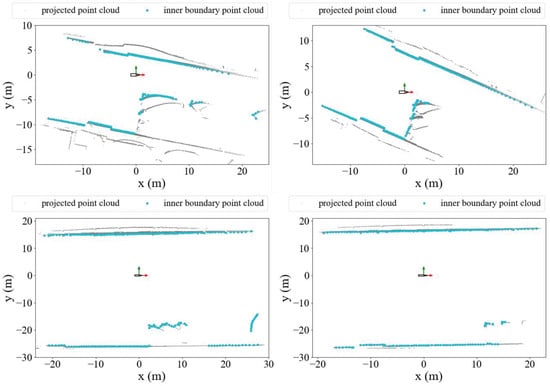

Figure 18 presents the results of the projected point cloud and the extracted inner boundary point cloud processed by the algorithm. It can be clearly observed that the inner boundaries within the point cloud have been accurately identified and extracted, forming complete inner boundary point clouds. This indicates that the proposed algorithm can effectively distinguish the inner boundaries from the surrounding point cloud while ensuring the continuity and accuracy of the boundary points. Through the projection and extraction steps, the algorithm robustly captures critical boundary information even in complex regions and berth structures. Overall, these results validate the high accuracy, robustness, and practical feasibility of the algorithm for inner boundary point cloud extraction.

Figure 18.

Result of inner boundary extraction from point cloud.

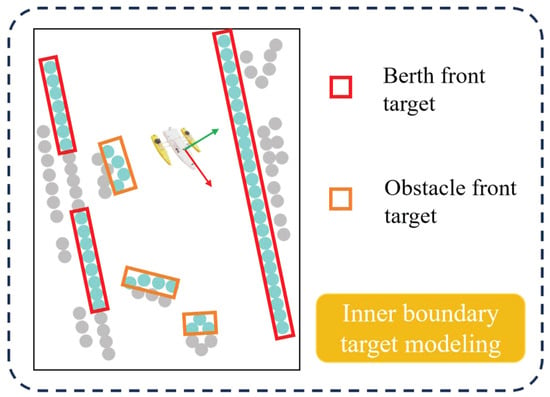

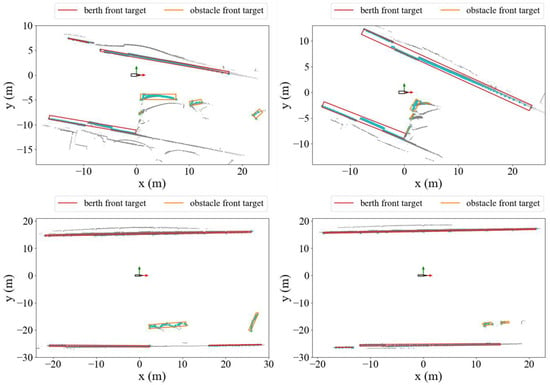

Figure 19 illustrates the results of inner boundary point cloud target classification. In the figure, red bounding boxes clearly indicate quay wall front targets, while orange bounding boxes accurately enclose obstacle front targets. The results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm can precisely classify inner boundary point clouds, effectively distinguishing between different types of boundary targets. Furthermore, the algorithm exhibits good robustness and stability in complex port environments, maintaining accurate classification even when berth boundaries are irregular or obstacles are densely distributed. This provides reliable foundational data for subsequent navigable region generation and berth analysis for the USV.

Figure 19.

Result of inner boundary target modeling.

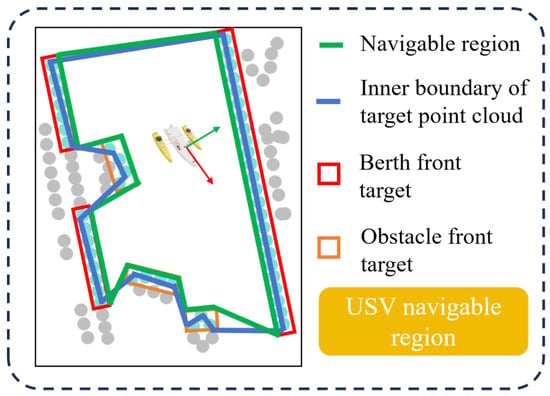

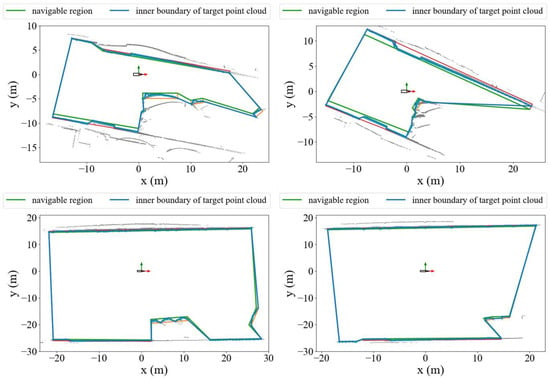

Figure 20 presents the results of the proposed algorithm, showing the target point cloud inner boundaries and the navigable region. In the figure, the area enclosed by green lines represents the USV’s navigable region, while the area enclosed by blue lines corresponds to the inner boundary of the target point clouds. As shown, the algorithm can accurately identify boundary points surrounding the USV’s path and generate a safe navigable region based on these points. These results indicate that the algorithm achieves high precision and stability in complex port environments, effectively distinguishing obstacles from navigable regions and providing reliable safety support for USV navigation.

Figure 20.

Result of navigable region generation.

To provide quantitative validation, we evaluate the algorithm using three widely adopted metrics: Precision, Recall, and Intersection over Union (IoU). The evaluation metrics are defined as:

where , , and denote the number of true positive, false positive, and false negative boundary points, respectively. Table 2 summarizes the quantitative evaluation results.

Table 2.

Quantitative evaluation of navigable region detection.

The consistently high Precision, Recall, and IoU metrics across all evaluation scenarios confirm the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed algorithm. These quantitative results substantiate the method’s capability to generate accurate, reliable, and stable navigable region boundaries even in complex and cluttered port environments.

4. Discussion

The proposed LiDAR-based system for USV localization and navigable region detection was validated through experiments conducted in a real port environment. The results demonstrate that the method exhibits high reliability and practicality in terms of both localization accuracy and environmental perception. The discussion is presented from the perspectives of experimental results, methodological advantages and limitations, and potential applications.

First, in terms of localization accuracy, the experimental results indicate that the map-based registration approach significantly outperforms pure scan matching. Specifically, the absolute trajectory error was reduced by 55.29%, while the relative trajectory error decreased by 38.71%. These findings confirm that incorporating a prior point cloud map can effectively suppress cumulative errors and enhance both global and local trajectory consistency. This validates the effectiveness of the proposed localization strategy, particularly in port scenarios where GNSS signals are heavily obstructed or completely unavailable, highlighting its significant engineering value. It should be noted, however, that the construction of the prior map relies on high-quality RTK and point cloud acquisition, and practical deployment must account for dynamic environmental changes in ports (e.g., new infrastructure or berthed vessels), which may affect the need for map updates.

Second, with respect to navigable region detection, the proposed method, which integrates point cloud inner boundary extraction and object classification, can accurately distinguish quay walls from obstacles and subsequently generate safe navigable regions. The experimental results show that the method maintains strong robustness even in complex environments characterized by irregular berth boundaries and dense obstacle distributions, thereby providing effective support for autonomous obstacle avoidance and berthing of USVs. Compared with existing approaches that rely solely on geometric fitting or object detection, the proposed combination of projection, boundary extraction, and clustering proves more capable of handling dynamic water surfaces and structurally complex port environments. The current study primarily focused on validating the navigable region detection algorithm based on LiDAR data. In future work, this framework can be integrated into a closed-loop control system for autonomous berthing. Specifically, the detected navigable region and boundary information can serve as real-time constraints or reference inputs for path tracking and motion planning modules, enabling dynamic adjustment of control commands during the berthing process.

Nevertheless, certain limitations remain. The LiDAR sensor used in the experiments was a 16-beam device, whose limited vertical resolution may lead to blind spots in detecting small-scale objects at long distances (e.g., floating debris). Future work may consider employing higher-resolution LiDAR or integrating additional sensors (e.g., millimeter-wave radar) to enhance perception capability. Furthermore, the experiments were primarily conducted in static or semi-static port environments; the impact of dynamic targets such as moving vessels and operational equipment has not yet been thoroughly evaluated and requires further validation in more complex dynamic settings. Moreover, the algorithm can be extended toward multi-sensor fusion frameworks by incorporating IMU, RTK, and marine radar data. Such fusion would further improve robustness against LiDAR occlusion, dynamic water surface interference, and environmental variability. The integration of semantic and geometric information across multiple sensing modalities represents a promising direction for achieving more comprehensive and reliable berthing perception in complex harbor environments. Finally, the construction and maintenance of the prior map remain time-consuming and rely heavily on manual efforts. Achieving dynamic map updating and ensuring long-term adaptability are pressing issues that should be addressed in future research.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a LiDAR-based integrated system for autonomous USV berthing, addressing the challenges of high-precision positioning and navigable region detection in complex port environments. The proposed method constructs a high-resolution 3D point cloud map by fusing LiDAR and RTK data, and estimates the USV’s pose through real-time map-based LiDAR scan matching. A novel navigable region detection algorithm is introduced, which extracts inner-boundaries from point clouds and classifies quay walls and obstacles to generate safe, navigable regions.

Field experiments conducted in Ling Shui Port, Dalian, demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed system. The map-based localization reduces ATE by 55.29% and RTE by 38.71% compared to conventional scan matching. The navigable region detection algorithm accurately identifies safe passage areas, even in environments with complex berth structures.

Overall, the experimental results validate that the proposed approach significantly improves positioning accuracy and navigation safety for autonomous USVs. The system provides a reliable, GNSS-independent solution, offering practical value for real-world autonomous berthing operations and laying a foundation for further development of intelligent port navigation technologies.

Author Contributions

H.W.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization. Y.Y.: Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Supervision. L.D.: Methodology, Resources, Software, Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition. H.L.: Writing—review & editing, Resources, Software, Investigation, Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 52071049); the National Key R&D Program of China (grant numbers 2022YFB4300803 and 2022YFB4301402); the Special Program of Guangzhou Maritime University (grant number K42025063); the project “Research and Industrial Application of Key Technologies for Integrated Power Systems of All-Electric Ships” (grant number K620250406); and the 2022 Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Plan (Key Project): “R&D and Application of Autonomous Navigation System for Smart Ships in Complex Waters” (grant number 2022JH1/10800096).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and security restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.; Yuan, C. Unmanned surface vehicles: An overview of developments and challenges. Annu. Rev. Control 2016, 41, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.O.; Gates, A.R.; Huvenne, V.A.; Phillips, A.B.; Bett, B.J. Autonomous marine environmental monitoring: Application in decommissioned oil fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 835–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.L.; Han, Q.L. Network-based modelling and dynamic output feedback control for unmanned marine vehicles in network environments. Automatica 2018, 91, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specht, M. Methodology for performing bathymetric and photogrammetric measurements using UAV and USV vehicles in the coastal zone. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablyakimov, I.S.; Shirokov, I.B. Operation of local positioning system for automatic ship berthing. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE East-West Design & Test Symposium (EWDTS), Novi Sad, Serbia, 27 September–2 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.S. Investigation of a multitasking system for automatic ship berthing in marine practice based on an integrated neural controller. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, H.F.; Zhang, G.; Yang, K.Y.; Yang, S.X.; Hsu, L.T. Improved weighting scheme using consumer-level GNSS L5/E5a/B2a pseudorange measurements in the urban area. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Marais, J.; Bétaille, D.; Berbineau, M. GNSS position integrity in urban environments: A review of literature. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 19, 2762–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dai, B.; Wu, T. Vision-based precision vehicle localization in urban environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 Chinese Automation Congress, Changsha, China, 7–8 November 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Vivet, D.; Gérossier, F.; Checchin, P.; Trassoudaine, L.; Chapuis, R. Mobile ground-based radar sensor for localization and mapping: An evaluation of two approaches. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, D.; Park, B.; Lee, S.M. Artificial intelligence vision-based monitoring system for ship berthing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 227014–227023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Q.; Niu, X. High-accuracy positioning in urban environments using single-frequency multi-GNSS RTK/MEMS-IMU integration. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hening, S.; Ippolito, C.A.; Krishnakumar, K.S.; Stepanyan, V.; Teodorescu, M. 3D LiDAR SLAM integration with GPS/INS for UAVs in urban GPS-degraded environments. In AIAA Information Systems-AIAA Infotech@ Aerospace; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017; p. 0448. [Google Scholar]

- Taketomi, T.; Uchiyama, H.; Ikeda, S. Visual SLAM algorithms: A survey from 2010 to 2016. IPSJ Trans. Comput. Vis. Appl. 2017, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Jurado, S.; Muñoz-Salinas, R.; Madrid-Cuevas, F.J.; Marín-Jiménez, M.J. Automatic generation and detection of highly reliable fiducial markers under occlusion. Pattern Recognit. 2014, 47, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. LOAM: Lidar odometry and mapping in real-time. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Berkeley, CA, USA, 12–16 July 2014; Volume 2, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B. Lego-loam: Lightweight and ground-optimized lidar odometry and mapping on variable terrain. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 4758–4765. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, T.; Englot, B.; Meyers, D.; Wang, W.; Ratti, C.; Rus, D. Lio-sam: Tightly-coupled lidar inertial odometry via smoothing and mapping. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–29 October 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 5135–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Yin, Y.; Jing, Q. Comparative analysis of 3D LiDAR scan-matching methods for state estimation of autonomous surface vessel. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yin, Y.; Jing, Q.; Xiao, F.; Cao, Z. A berthing state estimation pipeline based on 3D point cloud scan-matching and berth line fitting. Measurement 2024, 226, 114196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yin, Y.; Jing, Q.; Cao, Z.; Shao, Z.; Guo, D. Berthing assistance system for autonomous surface vehicles based on 3D LiDAR. Ocean Eng. 2024, 291, 116444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Xiao, C.; Zhan, W.; Zhou, C.; Xiu, S.; Yuan, H. A novel water-shore-line detection method for USV autonomous navigation. Sensors 2020, 20, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Hu, M.; Ren, F.; Bao, Y.; Shi, P.; Yu, D. River boundary detection and autonomous cruise for unmanned surface vehicles. IET Image Process. 2023, 17, 3196–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, C.; Chung, D.; Kim, J. Navigable area detection and perception-guided model predictive control for autonomous navigation in narrow waterways. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 5456–5463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, D.; Huang, K. LiDAR based navigable region detection for unmanned surface vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3 November 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 3754–3759. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, Y.; Yao, X.; Lin, H.; Zou, X.; Huang, K. LiDAR-based stable navigable region detection for unmanned surface vehicles. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, K.; Yokozuka, M.; Oishi, S.; Banno, A. Voxelized GICP for fast and accurate 3D point cloud registration. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 11054–11059. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Kim, A. Scan context: Egocentric spatial descriptor for place recognition within 3d point cloud map. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 4802–4809. [Google Scholar]

- Torr, P.; Zisserman, A. Robust computation and parametrization of multiple view relations. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Computer Vision (IEEE Cat. No. 98CH36271), Bombay, India, 4–7 January 1998; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 727–732. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lao, Y. FEC: Fast Euclidean clustering for point cloud segmentation. Drones 2022, 6, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).