Abstract

The bloom-forming dinoflagellates and euglenophyceae were observed in the coastal waters of Hammam-Lif (Southern Mediterranean), during a green tide event on 3 June 2023. The bloom was dominated by Lepidodinium chlorophorum, identified through ribotyping with densities reaching 2.3 × 107 cells·L−1. Euglena spp. and Eutrepsiella spp. contributed to the discoloration, with abundances up to 2.9 × 107 cells·L−1. Environmental data revealed significant depletion of nitrite and nitrate, coinciding with a rapid increase in sunlight duration, likely promoting the proliferation of L. chlorophorum and euglenophyceae. By 5 June, two days after the bloom, nutrient stocks were exhausted. Diatoms appeared limited by low silicate concentrations (<0.05 µmol·L−1), while dissolved inorganic phosphate and Nitrogen-ammonia were elevated during the bloom (0.88 and 4.8 µmol·L−1, respectively), then decreased significantly afterward (0.23 and 1.06 µmol·L−1, respectively). Low salinity (34.0) indicated substantial freshwater input from the Meliane River, likely contributing to nutrient enrichment and bloom initiation. After the event, phytoplankton abundance and chlorophyll levels declined, with a shift from dinoflagellates to diatoms. The accumulation of pigments (chlorophyll b and carotenoids) and the presence of Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) during and after the bloom suggest that UV radiation and Nitrogen-ammonia were key drivers of this green tide.

1. Introduction

Several dinoflagellate species are known to cause red tides in coastal waters, leading to the mortality of fish and other marine organisms, as well as human poisoning caused by specific toxins such as paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs), neurotoxic shellfish toxins (NSTs), diarrheic toxins (DSTs), and ciguatoxins (CTXs) [1]. In addition to the visible seawater discoloration, these blooms can threaten aquatic ecosystems by inducing hypoxic conditions that may result in high mortality among bivalves [2,3]. A variety of environmental drivers contribute to phytoplankton bloom events, including weather patterns, physico-chemical parameters, and nutrient concentrations. High nutrient inputs, often associated with upwelling systems and/or wastewater discharges, stimulate surface-level primary productivity and enhance the growth of opportunistic phytoplankton species. These dynamics frequently lead to harmful algal blooms (HABs), which are now widely acknowledged as a serious environmental issue [4]. Research has also linked green tide events to rising temperatures in certain marine regions [5,6,7]. The species Lepidodinium chlorophorum (previously known as Gymnodinium chlorophorum) is a non-toxic dinoflagellate [8,9] recognized for creating green-colored water in coastal zones. It is notable for its unique pigment profile, which includes neoxanthin, violaxanthin, chlorophylls a and b, and a dominant yet unidentified carotenoid compound [10]. In the Bay of Biscay (Atlantic Sea, France), blooms of L. chlorophorum have been recorded since 2007 with high abundance, generally occurring between April and August, with a peak in summer [11]. L. chlorophorum was detected in 2003 on the Rades coast (Tunisia) at low abundance (5280 cells·L−1) following its absence since 1994. This could indicate changes in environmental conditions affecting its presence [12]. Other studies performed in Chile, California, Australia, and across Europe revealed that the photosynthetic response of L. chlorophorum was influenced by the combined impacts of increased temperature (up to 25 °C) and high irradiance related to climate change [13,14]. It was also shown that L. chlorophorum has an affinity for summer-like environmental conditions [10]. On the other hand, in turbid waters, especially during summer, the settling of L. chlorophorum blooms may result from high ammonium loads caused by organic matter degradation [15]. Today, a better understanding of phytoplankton dynamics may benefit from the description of new phenomena occurring in specific Mediterranean ecosystems. This is of great importance for implementing management actions and predicting HABs and their impacts on marine ecosystem components.

The present work aims to highlight the occurrence of a green tide event that took place on 3 June 2023 in a southern Mediterranean marine ecosystem located on the Hammam-Lif coast, Northern Tunisia. We examined short-term meteorological and anthropogenic factors involved in trophic state changes that presumably provoked the bloom.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

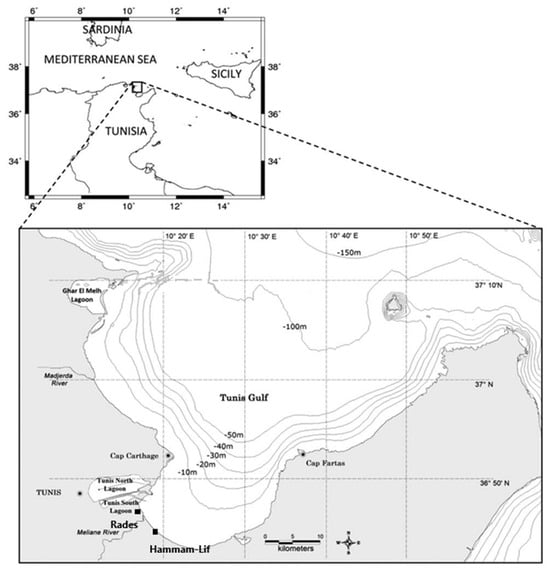

The Gulf of Tunis is located in the northeast of Tunisia in North Africa, southwestern Mediterranean Sea. The small Gulf, or Bay of Tunis, is a horseshoe-shaped sub-basin that covers an average area of 361.2 km2, representing 24% of the total area of the Gulf, and has an average depth of 15 m [15] (Figure 1). The 10 m isobath is located 5 km off the west coast and 400 m off the east coast [16]. The Hammam-Lif -Rades coastal area, extending for about 10 km along the Gulf of Tunis, is situated at the outlet of the Meliane River. This coastline is heavily influenced by the river, which flows through several urban and industrial zones and ultimately reaches the sea at Rades and Hammam-Lif [17]. As the Meliane River passes through highly populated and industrialized regions [18], it collects various contaminants, especially heavy metals, which are deposited into the sediments along its course and then into the sea [19]. The river mouth sediments function as an important reservoir for these contaminants [20]. Human activities in the surrounding areas have also led to the accumulation of solid waste and industrial residues. These pollutants often end up in the marine ecosystem, where they are first absorbed by organisms and then settle on the seabed [20].

Figure 1.

Sampling stations included in the analysis. Hammam-Lif is the main sampling station and the only station sampled on 3 and 5 June 2023. Rades has five years data used for analysis from 1994 to 2004.

2.2. Sampling Strategy and Physico-Chemical Parameters

Seawater samples were collected at the Hammam-Lif station (36.44.04.6° N, 10.20.03.9° E) from a depth of 0.5 m: once during the bloom event (3 June 2023) and once during the post-bloom phase (5 June 2023). The sea surface temperature (SST), salinity (S), pH, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen (DO) were measured in situ using a multi-parameter type Water Quality meter (Model 8603, Lohand Biological Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). Samples were then transported in a refrigerated box (4 °C) to the International Center for Environmental Technologies of Tunis (CITET). For determining chlorophyll a concentration, a volume of 250 mL of seawater was filtered using low vacuum pressure through GF/C filters (Whatman®, Cytiva, Maidstone, UK). The filter was ground manually into a glass centrifuge tube filled with 90% acetone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mixture was kept in the dark at −4 °C for 24 h to allow total extraction of chlorophyll a. Fluorescence was then measured before and after acidification with HCl (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Lambda 25, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) following the standard Lorenzen method [21,22] and as described by Aminot and Chaussepied [23]. For inorganic nutrients, water was filtered through GF/C membranes; 1 L for dissolved silicate (Si (OH)4), nitrogen (nitrate NO3−, nitrite NO2−), and phosphorus (PO43−) and 0.25 L for ammonia (NH4+) analysis (reagents from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China), using spectrophotometric methods as described by Parsons et al. [24]. For phytoplankton taxonomy analysis, a volume of 500 mL was fixed with paraformaldehyde (2% final concentration) and stored at +4 °C in the laboratory. Taxonomic identification and cell counts were performed following the Utermöhl method [25], using a Motic AE31E inverted microscope (Motic, Xiamen, China). Identification was carried out using standard taxonomic references [26,27,28,29,30,31]. A 10 mL subsample was settled for 24 h for analysis. To characterize the pigment composition of the phytoplankton community, a Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer (Cary Eclipse, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to record three-dimensional excitation–emission matrices (3D-EEMs). Fluorescence emissions were scanned across a range of 250 to 600 nm to quantify the intensity of algal pigments and discriminate among major algal groups based on specific pigment signatures.

2.3. Preparation of Nucleic Acids, PCR, Cloning, and Sequencing

From the Lepidodinium cells, total DNA was extracted using the DNA Isolation Reagent (TaKaRa) and served to amplify nucleus-encoded 18S rRNA genes. Amplification was performed using the primer pair: 5′-GAAACTGCGAATGGCTCT-3′ and 5′-CCGCAGGTTCACCTAC-3′. The PCR conditions were: 30 cycles of 96 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 20 s, and 72 °C for 3 min. Amplicons were cloned into the pGEM T-Easy vector (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA), and both strands were sequenced using Sanger techniques. The resulting rRNA gene sequences were deposited in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank.

2.4. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Evolutionary relationships of 23 taxa were inferred using the Neighbor-Joining method [32]. The optimal tree had a total branch length of 0.046. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches [33]. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths (above the branches) representing evolutionary distances based on the Maximum Composite Likelihood method [34]. Evolutionary distances were computed in units of base substitutions per site. The analysis included 23 coding nucleotide sequences and used 1st, 2nd, 3rd codon positions and non-coding sequences, with pairwise deletion for ambiguous positions, resulting in a final dataset of 808 positions. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA version 12.0.0 (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software; Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA) [35], utilizing up to 7 parallel computing threads.

2.5. Meteorological and Hydrological Data Collection and Processing

To better understand regional climate conditions and the functioning of the plankton ecosystem at Hammam-Lif coast, meteorological data from 1 March to 8 June 2023 were analyzed. Daily precipitation (mm), maximum and minimum temperatures (°C), maximum wind speed (km·h−1), East/West and South/North wind components, and daily sunshine duration (hours) were provided by the National Institute of Meteorology of Tunisia.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to assess relationships between physico-chemical parameters and biological data using Statistica software (version 64). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. To support these analyses, current data were combined with comparable datasets from a previous study on phytoplankton composition and abundance during early June in the years 1994, 1995, 2001, 2003, and 2004 at the Rades station (36°46′486″ N, 10°17′467″ E) [12] (See Appendix A, Table A1).

The coastal zones of Rades and Hammam-Lif share strong geographical and ecological similarities, as both are directly influenced by the Meliane River’s outflow into the Gulf of Tunis [15]. Rades and Hammam-Lif sites exhibit comparable hydrological dynamics, including freshwater inputs, sediment deposition, and seasonal variations [18,20]. They are also subject to similar anthropogenic pressures from nearby industrial, urban, and agricultural activities [36]. As a result, their environmental conditions, especially in terms of pollution patterns and biodiversity responses, are closely linked and can be studied using consistent methodologies.

This study applied canonical correlation analysis (CCA) to assess the associations between 14 hydrological variables (Dissolved Oxygen, nutrients, pH, Conductivity, total nitrogen, nitrates, nitrites, phosphates, silicate, temperature, salinity, sunshine, chlorophyll a, and MAA) and three major phytoplankton groups (euglenophyceae, diatoms, and dinoflagellates). Data from the 1990s, 2000s, and 2023 were analyzed to investigate temporal patterns and ecosystem shifts. Comparisons were made between the coastal systems of Rades and Hammam-Lif, revealing differences in hydrological drivers and phytoplankton community responses. Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria), with specialized CCA. In order to assess differences between the conditions recorded on 3 June and 5 June 2023, at Hammam-Lif, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was employed. Statistical significance was established at the 5% alpha level, indicating that the observed variations between the two sampling dates were significant.

3. Results

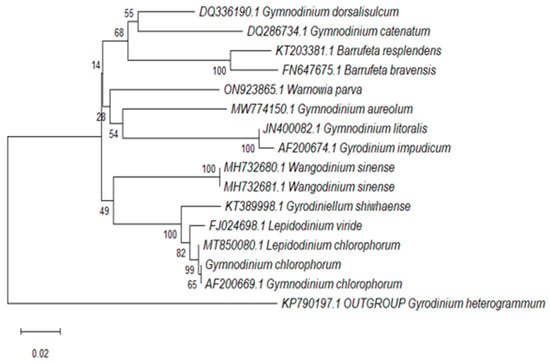

3.1. Ribotyping

We performed phylogenetic analysis of relationships among 14 close isolates/strains (Gymnodinium, Lepidodinium, Wangodinium, Gyrodinium and Barrufeta species) and the 594 bp sequence of LSU rRNA (18S) of L. chlorophorum. Sequences were obtained using an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer and aligned using a distance method. Out-group species was Gyrodinium heterogrammum. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. Bar: 0.02 divergence. Results showed the species responsible of the green tide in Hammam-Lif was L. chlorophorum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationship between L. chlorophorum isolated from the coastal waters of Hammam-Lif and related dinoflagellate species.

3.2. Meteorological and Hydrological Conditions During the Study Period

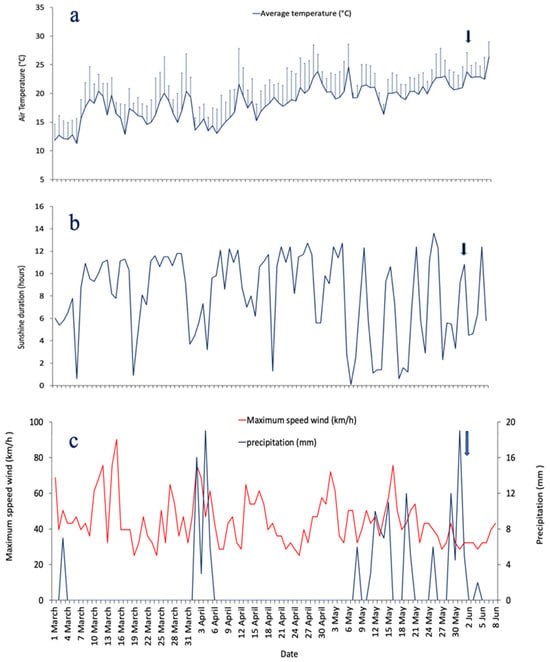

Between, 1 March and 8 June 2023, temperature and precipitation ranged from 5.1 °C (on 6 March) to 30.8 °C (on 30 April), and from 0 to 19 mm (on 31 March), respectively (Figure 3a,b). During this period, the highest sunshine duration was recorded on 27 May (13.6 h) (Figure 3c). The highest wind speed value was found on 15 March (90 km·h−1) and the lowest (28.8 km·h−1) on 8 and 24 April, 27 May, and 4 June (Figure 3b). A major precipitation event occurred from 2 to 5 April, with an average of 11 mm. Precipitation ranged from 3 mm on 3 April to 19 mm on 4 April. Just before the bloom, another important rainy event was recorded on 1 June (19 mm), followed by a high East-Southeast (ESE) dominant wind from 1 to 3 June.

Figure 3.

Daily variations of hydrological parameters from 1 March to 8 June 2023: (a) air temperature (°C, vertical lines indicate the standard error), (b) precipitation (mm) and maximum wind speed (km·h−1), (c) sunshine duration (hours). The black arrow marks the bloom event.

Sea surface temperature reached a value of 24.2 °C on 3 June. pH reached a low value (6.9) on 3 June 2023; whereas, on 5 June, a value of 8.1 was registered. Concentration of DO reached a low value of 2.2 mg·L−1 on 3 June 2023 (Table 1). Nitrite concentrations were relatively low during both date 3 and 5 June (0.016 µmol·L−1 and 0.014 µmol·L−1; respectively) suggesting nitrite limitation. Nitrate concentrations were homogenous during the two sampled days and did not exceed 0.5 µmol·L−1 (Table 1). High Nitrogen-ammonia concentrations of nearly 4.8 µmol·L−1 on 3 June and the high turbidity observed during the sampling period could be a result of the decomposition of organic matter through the microbial loop and an increased load of nutrient-rich organic matter. In fact, an increase in urban discharges (domestic effluents, sewage) towards the sea was observed expressed by the bad smell particularly during the first day of sampling. After the bloom, on 5 June, Nitrogen–ammonia appeared at 1.06 µmol·L−1. Silicate concentrations were similar in both dates, collected on 3 and 5 June 2023, with value lower than 0.05 µmol·L−1. Orthophosphate reached concentrations of 0.88 µmol·L−1 and 0.23 µmol·L−1 on 3 and 5 June, respectively.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical parameters and Chlorophyll a concentration (mg·L−1) in Hammam-Lif measured on 3 and 5 June 2023.

3.3. Chlorophyll a Concentration

An important difference in chlorophyll a concentration was noted between the two dates with a high concentration (980.42 µg·L−1) reached during the bloom (3 June), and a much lower value (2.32 µg·L−1) after the bloom event (5 June) (Table 1).

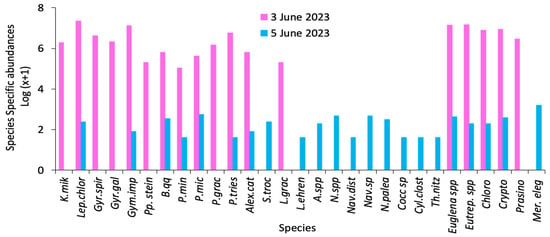

3.4. Phytoplankton Community Composition

The analysis of the phytoplankton community revealed a total of 18 species on 3 June and 22 species on 5 June 2023 (Table 2, Figure 4). The most dominant algal species were L. chlorophorum (>2.1 × 107 cells·L−1), Karenia mikimotoi (1.9 × 106 cells·L−1), Eutreptiella spp. (1.5 × 107 cells·L−1), Euglena spp. (1.4 × 107 cells·L−1), and Gymnodinium impudicum (1.3 × 107 cells·L−1). L. chlorophorum was identified as the primary specie responsible for the bloom and was likely the main cause of both the green water discoloration observed on 3 June (Figure 5(A1, A2)) and the stranding of bivalve shells (e.g., Cerastoderma edule, Venus mercenaria, Peloris spp., Murex spp.) (Figure 5B) along the coastal area a few days after the event.

Table 2.

List of phytoplankton species and abundance (cells L−1) on June 3 (bloom day) and 5 June 2023 (post-bloom) samples from Hammam-Lif.

Figure 4.

Species-specific phytoplankton abundances (log (x + 1) transformation) recorded during and after the bloom event in Hammam-Lif recorded on 3 and 5 June 2023 (where x = abundance in cells·L−1) (Karenia mikimotoi (K.mik), Gyrodinium spirale (Gyr.spir), Gymnodinium impudicum (Gym.imp), Blixaea quinquecornis (B.qq), Prorocentrum micans (P.tries), Scrippsiella trochoidea (S.troc), Licmophora ehrenbergii (L.ehren), Nitzschia sp. (N.spp.), Navicula sp. (Nav.sp.), Cocconeis sp. (Cocc.sp.), Thalassionema nitzschioides (Th.nitz), Eutreptiella sp. (Eutrep.spp.), Cryptophycae (Crypto) and Merismopedia elegans (Mer.eleg).

Figure 5.

(A1,A2) Photographs showing green seawater discoloration during the bloom event. (B) Mass mortality of bivalves caused by hypoxia at the Hammam-Lif sampling station, recorded on 3 and 5 June 2023.

The second most dominant group was euglenophyceae, with high abundances of Euglena spp. and Eutreptiella spp., both considered key contributors to the bloom event. L. chlorophorum and euglenophyceae together seem accounted for the majority of Chlorophyll a concentration during the bloom. Other potentially toxic or harmful species were also present, including Alexandrium spp., G. impudicum, K. mikimotoi, and Blixaea quinquecornis. During the post-bloom phase, the phytoplankton community shifted toward a dominance of diatoms, mainly from the family Nitzschiaceae. Nitzschia palea, Nitzschia spp., Cylindrotheca closterium, Thalassionema nitzschioides, Licmophora ehrenbergii, Amphora sp., and Navicula spp. were the main diatom species (Table 2).

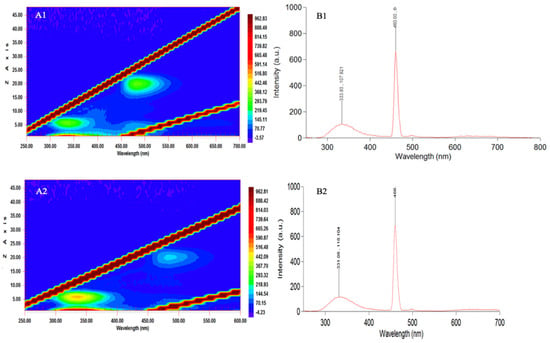

3.5. Fluorescence Spectra 15

Fluorescence spectra analysis of phytoplankton, measured under a broad excitation band ranging from 250 to 700 nm, revealed two main pigment groups, suggesting the presence of photosynthetic compounds characteristic of green photosynthetic dinoflagellates and euglenophyceae (Figure 6(A1,A2)). L. chlorophorum cells are likely associated with high fluorescence in two spectral regions: between 300–350 nm (photosynthetic compounds) and 450–470 nm (pigment type 1). The observed fluorescence peaking around 333/331 nm is consistent with the possible presence of UV-absorbing compounds such as Mycosporine-like amino acids MAAs, based on previous reports in L. chlorophorum and similar taxa, but we acknowledge that no chemical analysis of MAAs was conducted in this study. These compounds are known to confer protection against prolonged solar ultraviolet exposure and may enhance thermal stress tolerance in phytoplankton (Figure 6(B1,B2)).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence excitation-emission characteristics of seawater sampled during (A1,B1) and after (A2,B2) the green tide event in Hammam-Lif Bay. (A1,A2): Excitation-Emission Matrix (EEM) plots showing fluorescence intensity distribution: x-axis: Excitation Wavelength (nm), y-axis: Emission Wavelength (nm), Color bar: Fluorescence Intensity (a.u.). (B1,B2): Emission spectra recorded at a fixed excitation wavelength: x-axis: Wavelength (nm) and y-axis: Fluorescence Intensity (a.u.).

A secondary fluorescence maximum at 460 nm (λmax) was observed in the same species, which may be attributed to an unknown carotenoid potentially associated with chlorophyll b, as previously suggested by Zapata et al. [10] (Table 3; Figure 6(B1)). This fluorescence trend appeared consistent between bloom and post-bloom samples. However, on 5 June (post-bloom), discrimination of pigment groups in the 450–470 nm range was no longer possible, which may indicate the absence or significant reduction of the green bloom fluorescence signal (Figure 6(A2)).

Table 3.

Absorption by chlorophyll and carotenoid (1–4) from green autofluorescent algae based on literature data. Wavelengths indicative of pigments (5) and absorption by MAAs compounds during and after the bloom.

Despite this, fluorescence spectra from both sampling dates showed consistent peaks at 331 and 460 nm (Figure 6(B1,B2)), reflecting similar pigment composition. However, due to qualitative limitations of this method, precise comparisons of fluorescence intensity were not possible. These spectral analyses are intended to provide qualitative insights into pigment group presence rather than quantify pigment concentrations, thereby supporting the identification of algal taxa based on photosynthetic characteristics.

3.6. Effect of Environmental Factors on the Green Algal Bloom Event (Ancillary Data from Rades Station)

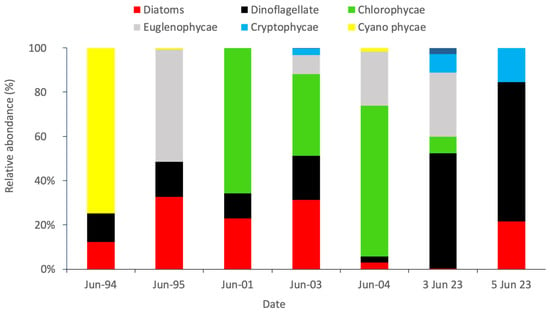

In the present study, there is only one sampling site at Hammam-Lif on two dates: 3 June 2023 (bloom day) and 5 June 2023 (post-bloom). In order to highlight potential relationships linking temporal changes to environmental factors (temperature, salinity, nutrients, sunlight duration, etc.) and analyze factors responsible for green algae event; previous study conducted in the Bay of Tunis and focused on Rades station on a long-time series prevailing from 1994 to 2008, during the summer period (with interruptions in time) was used for data treatment in combination with our data (see Methods) (See Appendix B, Table A2). Regarding taxonomic composition, a structural change in community was observed through years. The first period from the years 1994 to 2004 was dominated by Cyanophycae, Chlorophycae and diatoms mainly Nitszchiacae group. Phytoplankton taxa shifted to green dinoflagellates and euglenophycae in summer 2023, during the green tide event (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Variability in the relative abundance of algal groups during the summer periods of the years 1994, 1995, 2001, 2003, 2004, and 2023.

The highest phytoplankton abundance recorded at Hammam-Lif suggested that this site is influenced by effluents from domestic and industrial wastewater discharged by the Melian River. In fact, the seawater was turbid, and a foul odor was detected during sampling. This site received nutrients not only from anthropogenic sources but also from rainwater (Figure 3b), which may act synergistically, leading to elevated nutrient levels. These conditions provided an optimal ecological niche for the growth of certain phytoplankton species, resulting in high cell densities. Positive correlations were found between chlorophyll a and the total N: Si ratio; however, no correlation was observed between chlorophyll a and individual nutrients (NO3−, NO2−, NH4+, PO43−). This likely reflected the high uptake of these nutrients by phytoplankton. Significant relationships were found between chlorophyll a and sunshine duration, salinity, and dissolved oxygen (see Appendix C, Table A3).

The green dinoflagellate L. chlorophorum dominated at the Hammam-Lif site, occupying a temporary ecological niche and contributing significantly to the total chlorophyll a concentration (r > 0.90; p < 0.05). Its abundance was also strongly correlated with the N:Si ratio and dissolved oxygen levels. L. chlorophorum exhibited adaptation to high light conditions, as indicated by a strong correlation with sunshine duration (r > 0.90; p < 0.05). Nitrate concentration was positively correlated with dinoflagellate abundance (r = 0.91; p < 0.05). In contrast, Licmophora gracilis, the only diatom species observed during the bloom, was associated with low salinity (r = 0.99; p < 0.05) and a high N:Si ratio (r = 1.00; p < 0.05). Eutreptiella spp., a dominant euglenophyceae taxon during the bloom, was significantly correlated with chlorophyll a (r > 0.92; p < 0.05), phosphate concentration (r > 0.92; p < 0.05), and negatively correlated with salinity (r = −0.99; p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Occurrence of Gymnodinium chlorophorum and L. chlorophorum Blooms

Our study provides the first formal identification of L. chlorophorum blooms in the coastal waters of Tunisia, based on molecular approach. Despite extensive research on general bloom dynamics, surveys documenting blooms of Lepidodinium are noticeably absent. Gymondinium chlorophorum was observed in the Bay of Tunis at Rades and Sidi Raïs stations, but only at low abundances, with no bloom occurrence [12]. Existing studies mostly address more common harmful taxa, including Alexandrium [57], Prorocentrum [58], Dinophysis [59], and Pseudonitzschia [60], with no reference to Lepidodinium in Tunisian waters. Therefore, the present record seems to reflect an unusual, isolated bloom rather than a recurrent phenomenon. Since the late 20th century, L. chlorophorum blooms have become increasingly frequent worldwide, notably in the Mediterranean basin (Algerian waters, Brittany, and several lagoons) [7,61,62,63]. The earliest invasive bloom of G. chlorophorum was recorded in the Adriatic Sea in 1984 and identified using electron microscopy [64]. Lepidodinium chlorophorum has been widely described in the literature (Table 4), often identified based on morphological characteristics using photonic microscopy, or by satellite remote sensing and in culture conditions through genetic analysis [10,62]. In fact, these methods have been used essentially to study the biological and ecological properties of the species. The highest densities of L. chlorophorum have been reported in the coastal waters of Southern Brittany, reaching 8.9 × 106 cells·L−1 [7]. Our study also recorded high densities (>107 cells·L−1). As highlighted by recent works, the distribution of this species is generally confined to coastal areas and appears to be closely linked to freshwater runoff, nitrogen–ammonium enrichment [35], and stratification of the water column. These conditions often arise during river discharge periods and sea surface temperature (SST) variations, as observed during a L. chlorophorum bloom in Chile, where SSTs reached up to 25.4 °C [65]. The harmful effects of these blooms are primarily attributed to oxygen depletion resulting from the decomposition of organic matter. Fish mortality events have been reported across various ecosystems, where the decay of bloom biomass likely releases ichthyotoxic substances into the water.

Table 4.

Synthesis of existing data on G. chlorophorum and L. chlorophorum Bl.

4.2. Environmental Context of the Bloom in the Bay of Tunis

The exceptionally low pH recorded during the first sampling day was presumably due to freshwater input by the Medjerda and Meliane rivers. Daly Yahia [15] indicated that DO and pH are paradoxically inversely correlated in the Bay of Tunis. Indeed, when DO decreases due to respiration, CO2 levels rise, leading to a decrease in pH. In our study, DO reached a minimum value of 2.2 mg·L−1 during the bloom and pH dropped to 6.9.

In the Bay of Tunis, nitrite measured during the dry period reached a value of 0.04 µmol·L−1 in July 1995 [15]. The organic matter discharges in the bay’s coastal area are due to urban and industrial sewage, or to river flooding which drains numerous organic pollutants. An increasing gradient of organic matter from east to west was already reported in the Bay [15]. In our study, nitrate concentrations during the bloom and post-bloom periods were 0.5 µmol·L−1. Although the ecosystem experienced fluctuations in rainfall and was not entirely lacking in precipitation (average = 10.1 mm, SD = 6.8; from 29 May to 1 June 2023), the system could not balance the deficiency in nutrient concentrations, particularly nitrate, which was likely associated with the rapid and massive green algae bloom and the high nitrogen demand of phytoplankton. Phosphorus and nitrogen are known to be the main limiting nutrients for phytoplankton growth, with their seasonal variability influencing bloom dynamics [64]. Paerl et al. [69] demonstrated that nutrient limitation in Lake Taihu, China, shifts from phosphorus limitation during winter–spring to nitrogen limitation during summer and fall algal blooms. While the exact cause of the bloom observed in Hammam-Lif remains uncertain, several contributing factors can be identified. These include the accumulation of nutrients from river discharges, rainfall-driven nutrient inputs into the bay prior to the bloom (12 mm on 29 May, 19 mm on 31 May, and 5 mm on 1 June 2023), followed by a sustained period of low wind (maximum = 34.4 km·h−1 from 1 to 3 June 2023) and high solar radiation (sunshine duration = 10 h from 2 to 3 June 2023). Together, these conditions may have favored the development of the green water discoloration. Daly-Yahia Kéfi [16] reported a significant decrease in nitrate concentrations in the Bay of Tunis during spring and especially in summer, coinciding with phytoplankton development. In May 1994, Daly-Yahia [15] observed a marked diatom bloom, which likely contributed to a reduction in nitrate levels (0.47 µmol·L−1). In our study, ammonia–nitrogen concentrations ranged from 4.8 to 1.06 µmol·L−1 on 3 and 5 June 2023, respectively; values comparable to those recorded during the summers of 1994 and 1995 (2–6 µmol·L−1) [16]. The much lower ammonia–nitrogen concentration observed on 3 June compared to 5 June 2023, despite a short rainfall event occurring after the bloom (4 June), suggests that phytoplankton abundance and composition were influenced by this nutrient. Previous studies have shown that a decreasing nutrient gradient from the coast to the open sea highlights the dilution effect of the Bay of Tunis [16]. At the end of spring 1995 (June), the western and southwestern regions of the bay were characterized by an intense spring phytoplankton bloom, which was associated with a marked decrease in phosphate concentrations [12]. It can be hypothesized that the relatively low nutrient concentrations observed in our study are more likely the result of high uptake by blooming phytoplankton species rather than nutrient limitation per se. The Hammam-Lif ecosystem is strongly influenced by anthropogenic nutrient inputs, particularly from riverine sources.

4.3. Potential Links Between Nutrient Loading and Phytoplankton Dynamics in the Bay of Tunis

During this study, surface waters were characterized by Si:N and Si:P molar ratios lower than canonical Redfield stoichiometry (Si:N < 1; Si:P < 16), suggesting silicate limitation, which can suppress diatom growth and favor blooms of dinoflagellates and euglenophyceae [69,70]. The observed N:P ratio was also below Redfield norms (16:1), with values of 0.58 during the bloom and 2.23 post-bloom, indicating nitrogen limitation. Anthropogenic nutrient inputs, particularly from the Meliane River, as evidenced by subsurface low salinity observed by local fishermen, likely created favorable conditions for bloom development. Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong relationships between low salinity and the abundance of Euglena spp. (r = 0.88, p < 0.05), Eutrepsiella spp. (r = 0.87, p < 0.05), and the freshwater diatom Licmophora gracile (r = 0.88, p < 0.05). These results underscore the potential role of seasonal rainfall and riverine discharge from the Meliane River, which typically peaks during the summer months and coincides with increased freshwater input and nutrient loading. Such conditions, common during transitional seasons in the Mediterranean, are known to promote dinoflagellate and Euglenoid dominance under silicate-limited regimes, as diatom proliferation is suppressed [69,70,71,72]. These findings suggest that nutrient depletion during the bloom was primarily driven by biological uptake rather than by inherent nutrient scarcity. Similar patterns have been observed globally, where blooming phytoplankton rapidly deplete dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) reserves [72,73]. Although ammonium (NH4+) concentrations were higher than those of nitrate or nitrite, total nitrogen levels showed a strong correlation with NH4+ (r = 0.98), highlighting its pivotal role in bloom dynamics. As demonstrated in other systems, single-nutrient models often fall short in capturing the complexity of algal growth dynamics in natural ecosystems [74]. Following the bloom peak, L. chlorophorum abundance declined sharply, from 2.3 × 107 to 240 cells·L−1, coinciding with a drop-in ammonium concentration (from 4.8 to 1.06 µmol·L−1). Roux et al. [63] similarly attributed bloom decline to the depletion of nitrogen–ammonia.

Chlorophyll a concentration (980.4 µg·L−1) was exceptionally high compared to other marine systems [74,75], although such high biomass accumulation in dinoflagellate blooms is not unprecedented [76]. Following the peak in chlorophyll a, dissolved oxygen (DO) levels rebounded from 2.2 to 7.3 mg·L−1, likely due to both a decrease in respiratory demand and enhanced vertical mixing. The capacity to detect such high chlorophyll a concentration has been previously demonstrated [77]. The extremely high phytoplankton abundance (1.03 × 108 cells·L−1), particularly of L. chlorophorum, likely contributed to the initial low oxygen concentration (2.2 mg·L−1) as a result of elevated cellular respiration. Following this bloom peak, L. chlorophorum abundance decreased sharply to 240 cells·L−1 by 5 June, coinciding with a rapid rise in DO to 7.3 mg·L−1. Litchman [78] demonstrated that shifts in physical conditions and nutrient availability can profoundly influence phytoplankton community structure, dynamics, and diversity, patterns that were observed in our study and have also been reported in the Atlantic and southwestern Mediterranean Sea [79,80]. Overall, our findings confirm that spring phytoplankton blooms are often driven by water column stratification, yet remain vulnerable to disruption by wind-induced mixing [81]. Consistent with these observations, recent studies emphasize that the temporal dynamics and taxonomic composition of phytoplankton communities in coastal marine waters are strongly modulated by environmental fluctuations, including sea surface warming, vertical mixing, and eutrophic conditions [7].

Phytoplankton spring blooms are often favored by water column stratification under calm conditions, which enhance light availability in the upper layers and support phytoplankton growth. However, such blooms are typically unstable, as wind events can induce deep mixing, reduce light penetration, and disrupt bloom development [81]. Sudden increases in wind speed or shifts in wind direction can enhance vertical mixing, resuspend sediments, increase turbidity, and further limit light availability, ultimately altering primary production. Our analysis suggests that the abrupt decline in phytoplankton abundance following the intense green algal bloom may have been driven by changes in environmental conditions, particularly a shift in wind direction from ESE to ENE, coupled with variations in nutrient availability. The exceptionally high abundance of the phytoplankton community, particularly L. chlorophorum, likely accounts for the very low dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration (2.2 mg·L−1) observed during the bloom, primarily due to intense respiration. Following the bloom peak on 3 June 2023 (reaching 1.03 × 108 cells·L−1), L. chlorophorum abundance declined sharply to 240 cells·L−1 by 5 June. This abrupt decrease coincided with a substantial rise in DO to 7.3 mg·L−1, likely driven by a strong wind event that enhanced vertical mixing. The resulting re-oxygenation of the water column and redistribution of nutrients may have contributed to the collapse of the bloom. The end of the bloom also marked a notable shift in phytoplankton community structure. Diatoms became dominant once again, as observed during the post-bloom sampling on 5 June. The diatom assemblage, primarily from the family Nitzschiaceae, including Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Nitzschia longissima, N. palea, Nitzschia sp., C. closterium, and Lithodesmoides polymorphum, is consistent with long-term patterns previously reported in the adjacent Bay of Tunis [12], where diatoms have constituted the structural phytoplankton community since 2003. T. nitzschioides has also been historically documented as a recurrent and often dominant species in this region, particularly during the winters of 1994–1995 and throughout the period from 1995 to 2001. Additionally, the present study identified several dinoflagellate species as highly abundant during the bloom, including G. impudicum, L. chlorophorum, B. quinquecornis, P. micans, P. triestinum, Scrippsiella trochoidea, and Alexandrium catenella. Additionally, many dinoflagellates possess the unique ability to utilize dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) through enzymatic processes, providing them with a competitive advantage in phosphate-limited environments [82]. For example, K. mikimotoi, which accounted for approximately 2% of the dinoflagellate community during the bloom, appears capable of accessing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as a phosphorus source, thereby demonstrating an alternative phosphorus acquisition strategy [83]. Moreover, the mixotrophic behavior commonly exhibited by dinoflagellates enables them to fulfill their phosphorus requirements when dissolved inorganic phosphate (DIP) is scarce [84]. This flexibility in nutrient acquisition strategies allows dinoflagellates to persist, and often dominate in coastal ecosystems characterized by fluctuating nutrient regimes. Experimental studies have further demonstrated that species such as K. mikimotoi exhibit enhanced survival under both phosphorus-rich and phosphorus-deficient conditions. These findings support the observed dominance of dinoflagellate communities in the Gulf of Tunis [85]. Among cyanobacteria, Merismopedia elegans was identified as a recurrent genus in the area. Its reappearance following the bloom highlights the resilience and seasonal dynamics of the phytoplankton community in the Bay of Tunis.

4.4. Response to Sunlight (UV) on Phytoplankton Bloom

In this study, a short-term increase in ultraviolet radiation, from 3.3 to 10.8 h, was observed between 1 and 3 June 2023, coinciding with the development of the dinoflagellate L. chlorophorum and euglenophyceae species. Phytoplankton exposed to elevated UV irradiance often synthesize soluble protective compounds known as mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs), which confer UV tolerance and mitigate harmful effects [53]. These compounds absorb efficiently in the UV-A (315–400 nm) and/or UV-B (280–315 nm) ranges, dissipating the absorbed energy as heat. This mechanism prevents the formation of reactive oxygen species and protects cells from photooxidative stress [86]. Our data suggest that the phytoplankton community in Hammam-Lif is capable of producing MAAs, as indicated by absorbance maxima at λmax = 333 and 331 nm in response to increased UV radiation. Although MAAs are typically associated with fungi, red algae (Rhodophyta), and cyanobacteria [86,87,88,89], their presence in green algae has been a subject of debate [90]. However, our findings indicate that green algae, such as L. chlorophorum, Euglena spp., and/or Eutrepsiella spp., may indeed produce MAAs as a physiological response to intense natural UV exposure. Furthermore, high UV absorbance (up to 10 h of exposure) combined with significant nitrogen–ammonia inputs may have contributed to the mass proliferation of these algae. This study aligns with previous findings emphasizing the complex interplay between UV radiation and nutrient availability. Zhang et al. [91], through mesocosm experiments, demonstrated that phytoplankton biomass responded positively to UV radiation only under nutrient-enriched conditions [87], whereas no significant biomass response was observed under oligotrophic conditions. Similarly, Marcoval et al. [92] showed that, in nutrient-rich environments, dinoflagellates may outcompete diatoms due to their greater physiological tolerance to UV stress.

These findings suggest a clear interaction between nutrient status and UV radiation, reinforcing the hypothesis that both nutrient enrichment and high solar irradiance acted synergistically to promote the bloom event observed in Hammam-Lif. In this context, we propose a probabilistic hypothesis: the simultaneous occurrence of elevated ammonium concentrations and prolonged daily sunlight exposure (exceeding 10 h of UV radiation) significantly contributed to the development of the bloom.

4.5. Response of the Phytoplanktonic Community to Hydrological Variability

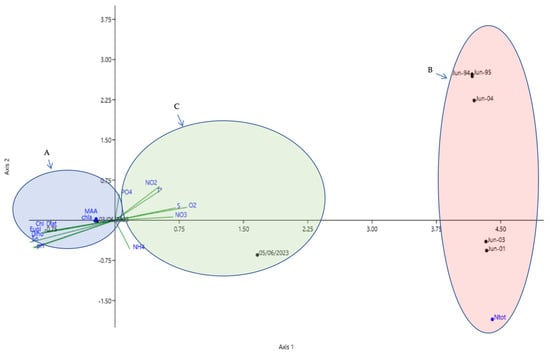

Our observations highlight the strong geographical and ecological proximity between the coastal ecosystems of Rades and Hammam-Lif. Previous studies confirm that hydrodynamic circulation, terrestrial inputs, and phytoplankton community structure share common features [15,19,20], which justifies the integration of Rades data into our comparative analysis. Both sites are under significant anthropogenic pressures, notably nutrient enrichment from urban effluents and riverine discharges, resulting in eutrophic conditions [15,16]. The pronounced bloom of 3 June 2023 at Hammam-Lif (Association A), a confirmed red tide event through both scientific records and fishermen’s reports, was dominated by euglenophyceae and dinoflagellates (Figure 8). The event extended to Rades but at lower intensity, as reported by fishermen and local residents. This difference is likely linked to hydrological variability (wind, inflows, stratification) and, importantly, to the recent establishment of a wastewater outlet at Hammam-Lif, releasing untreated effluents directly into the sea and appears to have played a decisive role in triggering the bloom at this site. This local input of nutrients provides an explanation for the observed higher intensity at Hammam-Lif compared to Rades and likely influenced site-specific phytoplankton responses, despite their overall ecological similarity. Such events have become increasingly reported along the Hammam-Lif coast and in other Tunisian lagoons and coastal areas [93,94,95]. Conversely, the conditions represented by Association (B) (late 1990s–early 2000s) are interpreted as a reference state, prior to the emergence of more frequent and intense bloom events, and indicated a regular phytoplankton dynamic and ecological stability with no reports of green tides. During this period, phytoplankton assemblages appeared to be less influenced by episodic nutrient surges, suggesting a relatively lower ecosystem reactivity to anthropogenic pressures due to reduced wastewater discharge and limited human impact. Association (C) represents transitional phases between this reference state and the current bloom-prone condition, highlighting the progressive ecological shift occurring in these coastal ecosystems. The ecological trajectory therefore moves from a relatively balanced past state through transitional conditions to the current scenario of recurrent blooms, likely driven essentially by ammonium enrichment and prolonged solar radiation. This trend highlights the urgent need for continued monitoring and integrated management to reduce nutrient inputs and restore ecological balance, consistent with other Mediterranean eutrophic systems. Thus, the temporal associations (A, B, C) outline a coherent ecological trajectory: from a relatively balanced state (B), through transitional conditions (C), to the current scenario dominated by recurrent blooms (A). This trend highlights the urgent need for continued monitoring and the implementation of integrated management strategies aimed at reducing nutrient loading and restoring ecological balance along the Tunisian coast. These findings are consistent with regional observations of phytoplankton dynamics in eutrophic Mediterranean system.

Figure 8.

Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA) illustrating three temporal situations of phytoplankton population dynamics in relation to environmental factors. Diatoms (Diat), Dinoflagellates (Dino), Euglenophyceae (Eugl), Chlorophyll a (Chl a), mycosporine-like amino acids (MAA), sunshine duration (Sn), nitrates (NO3), nitrites (NO2), ammonium (NH4), total nitrogen (Ntot), phosphate (PO4), dissolved oxygen (O2), and salinity (S).

5. Conclusions

Studies on water discoloration phenomena are scarce in the Southern Mediterranean, including Tunisia. This study reports the first confirmed occurrence of a L. chlorophorum bloom in Tunisian waters, specifically in the coastal area of Hammam-Lif, providing new insights into phytoplankton dynamics in Tunis Gulf. It also represents the first molecular identification of L. chlorophorum in the Southwestern Mediterranean Basin and documents an ecologically significant yet previously uncharacterized bloom. The bloom of the 3 June 2023 was initially dominated by L. chlorophorum and euglenophyceae, before rapidly shifting toward diatoms in the post-bloom phase. This transition was linked to changes in pigment composition, dissolved oxygen depletion, and the presence of MAAs, suggesting complex interaction between community succession and environmental stressors. Results highlight nitrogen–ammonia and increased solar radiation as key drivers of bloom initiation and development. The event caused chaotic ecological disturbances, notably damaging the bivalve community. Extending monitoring programs and establishing long-term series of key pelagic species in the Gulf of Tunis are essential to better understand phytoplankton variability and support integrated, sustainable coastal management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi), M.L. and A.H.; methodology, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi), C.F. and M.L.; software, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi); formal analysis, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi) and A.H.; investigation, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi) and I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S. (Noussaiba Salhi), M.P., C.F., I.L. and M.L., writing, review and editing, M.L., N.S. (Neila Saidi) and A.H.; validation, M.P., M.L. and N.S. (Neila Saidi); supervision, M.P., M.L. and N.S. (Neila Saidi); project administration, N.S. (Neila Saidi); funding acquisition, N.S. (Neila Saidi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (LR15CERTE04, 2022–2026 Program).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ons Daly-Yahia and Nejib Daly-Yahia for their assistance in providing access to the inverted photonic microscope. We also thank Asma Abdedayem from CERTE for her support with fluorescence spectroscopy analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

Hereby, I Noussaiba Salhi and co-authors consciously assure that for the manuscript “First record of Lepidodinium chlorophorum and the associated phytoplankton community responsible of the green tide South Western Mediterranean Sea (Hammam-Lif, Tunisia)” is fulfilled.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| L. chlorophrum | Lepidodinium chlorophorum |

| TEP | Transparent Exopolymer Particles |

| HABs | Harmful Algal Blooms |

| MAAs | Mycosporine-like amino acids |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Samples analyzed included in the statistical analysis (Phytoplankton and environmental parameters time series pooled by summer month (June) attached).

Table A1.

Samples analyzed included in the statistical analysis (Phytoplankton and environmental parameters time series pooled by summer month (June) attached).

| Years | Stations |

|---|---|

| 1994 | Rades |

| 1995 | Rades |

| 2001 | Rades |

| 2003 | Rades |

| 2004 | Rades |

| 2023 | Hammam-Lif |

| 2023 | Hammam-Lif |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Physico-chemical parameters and abundance of different phytoplankton groups recorded within the Rades Ecosystem.

Table A2.

Physico-chemical parameters and abundance of different phytoplankton groups recorded within the Rades Ecosystem.

| Period Investigated | 1994 | 1995 | 2001 | 2003 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | 26.2 | 26.2 | 26 | 24 | - |

| Salinity (psu) | 38 | 37.9 | 37.7 | 37.1 | - |

| Phosphate (µmol·L−1) | 0.22 | 1.85 | 0.06 | 0.60 | - |

| Nitrate (µmol·L−1) | 1.62 | 1.42 | 1.33 | 3.45 | - |

| Nitrite (µmol·L−1) | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.01 | - |

| Ammonium (µmol·L−1) | 1.22 | 1.85 | 16.80 | 5.467 | - |

| Silicate (µmol·L−1) | 1.89 | 2.26 | 2.30 | 1.3 | - |

| Diatoms (cells L−1) | 36,946 | 16,761 | 5090 | 29,040 | 47,520 |

| Dinoflagellates (cells L−1) | 39,780 | 6558 | 1900 | 18,480 | 36,960 |

| Chlorophycae (cells L−1) | 0 | 0 | 9420 | 34,400 | 90,816 |

| Cryptophycae (cells L−1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2640 | 0 |

| Euglenophycae (cells L−1) | 0 | 21,120 | 7920 | 324,720 | |

| Prymnesiophycae (cells L−1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 240 | 0 |

| Cyanophycae (cells L−1) | 225,720 | 320 | 0 | 130 | 21,120 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Results of STATISTICAL analysis r coefficient for selected diatoms, dinoflagellates and euglenophyceae species with physico-chemical parameters. All variables marked in red present a significant factor, t test, p < 0.05 (Correlations Marked correlations are significant at p < 0.05000 N = 6 (Casewise deletion of missing data)).

Table A3.

Results of STATISTICAL analysis r coefficient for selected diatoms, dinoflagellates and euglenophyceae species with physico-chemical parameters. All variables marked in red present a significant factor, t test, p < 0.05 (Correlations Marked correlations are significant at p < 0.05000 N = 6 (Casewise deletion of missing data)).

| Chlorophyll 0 | B. malleus | Licmophora spp. | Licmophora flabellata | Licmophora gracilis | Diatoms | P. micans | Pp.quinque Corne | Alex tamarense | Gym. chlorophorum | Dinoflagelates | Chlorophycea | Eutreptiella sp. | Euglena sp. | Euglenophyceae | Cryptophyceae | Cyanobacteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunshine | 0.91 | −0.254 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.909 | −0.431 | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.91 | −0.372 | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.909 | −0.258 | 0.909 | −0.372 |

| Wind | 0.634 | −0.254 | 0.623 | 0.335 | 0.779 | −0.431 | 0.623 | 0.335 | 0.335 | 0.335 | −0.372 | 0.623 | 0.335 | 0.335 | −0.258 | 0.335 | −0.372 |

| Max Temp | 0.664 | −0.254 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.634 | −0.431 | 0.623 | 0.623 | 0.623 | 0.623 | −0.372 | 0.623 | 0.623 | 0.634 | −0.258 | 0.335 | −0.372 |

| Min Temp | 0.625 | −0.254 | 0.623 | −0.254 | 1 | −0.431 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −0.372 | 0.997 | 1 | 1 | −0.258 | 1 | −0.372 |

| AvTemp | 0.654 | −0.454 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.159 | −0.431 | −0.26 | −0.263 | −0.263 | −0.26 | −0.372 | 0.887 | −0.26 | 0.877 | −0.258 | 0.877 | −0.372 |

| SST | 0.204 | 0.194 | 0.281 | 0.294 | 0.204 | −0.843 | 0.204 | 0.208 | 0.204 | 0.204 | −0.372 | 0.133 | 0.184 | 0.204 | −0.372 | 0.204 | 0.398 |

| Salinity | 0.999 | 0.262 | 0.281 | 0.999 | 0.159 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.159 | 0.9999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | −0.372 | 0.999 | 0.426 |

| pH | 0.588 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.588 | 0.588 | −0.431 | 0.588 | 0.588 | 0.588 | 0.588 | −0.372 | 0.588 | 0.588 | 0.779 | −0.258 | 0.779 | −0.442 |

| Conductivit y | 0.623 | 0.262 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.623 | −0.431 | 0.623 | 0.262 | 0.261 | 0.623 | −0.372 | 0.261 | 0.623 | 0.623 | −0.258 | 0.261 | −0.442 |

| Oxygene | 0.999 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 1 | 0.204 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 1000 | 0.999 | 0.261 | 0.999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −0.442 | 1 | −0.372 |

| N/P | −0.654 | −0.254 | 0.997 | 0.779 | −0.26 | −0.315 | −0.26 | 0.294 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.372 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.442 | −0.442 | 0.838 |

| N/Si | 0.959 | −0.254 | 0.958 | −0.854 | 0.958 | 0.588 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.958 | −0.426 | 0.958 | 0.958 | 0.958 | −0.26 | 0.958 | −0.372 |

| PO4 | 0.779 | 0.376 | −0.454 | −0.354 | 0.779 | −0.315 | 0.779 | 0.785 | 0.779 | 0.779 | −0.372 | 0.739 | 0.779 | 0.779 | 0.921 | 0.779 | 0.913 |

| NO3 | −0.754 | 0.904 | −0.254 | −0.254 | 0.862 | −0.015 | −0.372 | 0.779 | −0.372 | 0.91 | −0.149 | −0.418 | −0.372 | −0.372 | −0.622 | −0.372 | 0.492 |

| NO2 | −0.254 | −0.34 | 0.971 | 0.874 | −0.209 | −0.643 | −0.209 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.442 | −0.258 | −0.26 | −0.442 | −0.342 | −0.209 | 0.656 |

| NH4 | −0.072 | −0.167 | 0.937 | 0.934 | −0.007 | −0.383 | −0.072 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.442 | −0.108 | −0.372 | −0.442 | −0.442 | −0.072 | 0.899 |

| Si04 | −0.556 | 0.102 | 0.634 | 0.634 | −0.556 | −0.451 | −0.561 | −0.556 | −0.556 | −0.556 | −0.556 | −0.619 | −0.556 | −0.556 | −0.556 | −0.556 | 0.623 |

Table A4.

Results of STATISTICAL analysis Mann-Whitney test (equal medians) (p < 0.05) (N = 29) between the density levels of the two temporal situations on 3 June 2023 and 5 June 2023).

Table A4.

Results of STATISTICAL analysis Mann-Whitney test (equal medians) (p < 0.05) (N = 29) between the density levels of the two temporal situations on 3 June 2023 and 5 June 2023).

| Mann-Whitney Test for “Equal Medians” | ||

|---|---|---|

| 3 June 2023 | 5 June 2023 | |

| N | 29 | 29 |

| Mean rank | 17.164 | 12.336 |

| Mann-Whitey U | 280.5 | |

| Z | 2.2 | |

| P (same med) | 0.02 | |

References

- Caruana, A.M.; Amzil, Z. Microalgae and toxins. In Microalgae in Health and Disease Prevention; Levine, I.A., Fleurence, J., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 263–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granéli, E.; Turner, J.T. An introduction to harmful algae. In Ecology of Harmful Algae; Granéli, E., Turner, J.T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Stanisiere, J.-Y.; Mazurie, J.; Bouget, J.-F.; Langlade, A.; Gabellec, R.; Retho, M.; Meidy-Deviarni, I.; Goubert, E.; Cochet, H.; Dreano, A.; et al. Les Risques Conchylicoles en Baie de Quiberon. Troisième Partie: Risque D’hypoxie pour L’huître Creuse Crassostrea gigas. Rapport Final du Projet RISCO 2010–2013; Ifremer: Brest, France, 2013; p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, M.L.; Trainer, V.L.; Smayda, T.J.; Karlson, B.S.O.; Trick, C.G.; Kudela, R.M.; Ishikawa, A.; Bernard, S.; Wulff, A.; Anderson, D.M.; et al. Harmful algal blooms and climate change: Learning from the past and present to forecast the future. Harmful Algae 2015, 49, 68–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.J.; Liu, D.Y.; Anderson, D.M.; Valiela, I. Introduction to the special issue on green tides in the Yellow Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, R.; Chapelle, A.; Antoine, V.; Michel-Guillou, E.; Rigaut-Jalabert, F.; Guillou, L.; Curd, A. Citizen participation in monitoring phytoplankton seawater discolorations. Mar. Policy 2020, 117, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, P. Propriétés Écologiques des Efflorescences de Lepidodinium Chlorophorum: De L’écophysiologie Cellulaire à L’impact sur L’écosystème. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Brest, France, 2022; p. 330. [Google Scholar]

- Elbrächter, M.; Schnepf, E. Gymnodinium chlorophorum, a new, green, bloom-forming dinoflagellate (Gymnodinales, Dinophyceae) with a vestigial prasinophyte endosymbiont. Phycologia 1996, 35, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G.; Botes, L.; De Salas, M. Ultrastructure and large subunit rDNA sequences of Lepidodinium viride reveal a close relationship to Lepidodinium chlorophorum comb. nov. (=Gymnodinium chlorophorum). Phycol. Res. 2007, 55, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, M.; Fraga, S.; Rodríguez, F.; Garrido, J.L. Pigment-based chloroplast types in dinoflagellates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012, 465, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasiewicz, S.; Chapelle, A.; Bacher, C.; Soudant, D. Harmful algae niche responses to environmental and community variation along the French coast. Harmful Algae 2020, 93, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salhi, N. Perturbations Environnementales et Structuration du Peuplement Phytoplanctonique Côtier de la Baie de Tunis. Master’s Thesis, Université de Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia, 2009; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, P.; Schapira, M.; Mertens, K.N.; André, C.; Terre-Terrillon, A.; Schmitt, A.; Siano, R. When phytoplankton do not bloom: The case of the dinoflagellate Lepidodinium chlorophorum in southern Brittany (France) assessed by environmental DNA. Prog. Oceanogr. 2023, 212, 102999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häder, D.P.; Richter, P.R.; Villafañe, V.E.; Helbling, E.W. Influence of light history on the photosynthetic and motility responses of Gymnodinium chlorophorum exposed to UVR and different temperatures. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 138, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly Yahia, M.-N. Dynamique Saisonnière du Zooplancton de la Baie de Tunis (Systématique, Écologie Numérique et Biogéographie Méditerranéenne). Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Tunis, Tunis, Tunisia, 1998; p. 237. [Google Scholar]

- Kouki, A. Contribution à L’étude de la Dynamique Sédimentaire dans le Petit Golfe de Tunis; Thèse de 3e cycle; Faculté des Sciences de Tunis: Tunis, Tunisia, 1984; p. 167. [Google Scholar]

- Daly Yahia-Kéfi, O.; Nézan, E.; Daly Yahia, M.N. Sur la présence du genre Alexandrium Halim (Dinoflagellés) dans la Baie de Tunis (Tunisie). Oceanol. Acta 2001, 24, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Lamine, Y.; Pringault, O.; Aissi, M.; Ensibi, C.; Mahmoudi, E.; Kefi, O.D.Y.; Yahia, M.N.D. Environmental controlling factors of copepod communities in the Gulf of Tunis (South Western Mediterranean Sea). Cah. Biol. Mar. 2015, 56, 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yahyaoui, A.; Amor, R.B.; Tissaoui, C.; Chouba, L. Répartition du mercure dans les sédiments de surface de l’oued Meliane et de la frange littorale Rades-Hammam-Lif, golfe de Tunis (Tunisie). INSTM Bull. Mar. Freshwater Sci. 2020, 47, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennouri, R.; Zaaboub, N.; Fertouna-Bellakhal, M.; Chouba, L.; Aleya, L. Assessing trace metal pollution through high spatial resolution of surface sediments along the Tunis Gulf coast (Southwestern Mediterranean). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5322–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzen, C.J. Determination of chlorophylle and pheopigments: Spectrophotomètrie equations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1967, 12, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminot, A.; Kérouel, R. Hydrologie des Écosystèmes Marins. Paramètres et Analyses; Ifremer Éditions: Brest, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aminot, A.; Chaussepied, M. Manuel des Analyses Chimiques en Milieu Marin; Centre National pour l’Exploitation des Océans: Brest, France, 1983; p. 395. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T.R.; Maita, Y.; Lalli, C.M. A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods for Seawater Analysis; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1984; p. 173. [Google Scholar]

- Utermöhl, H. Zur Vervollkommnung der quantitativen Phytoplankton-Methodik. Int. Ver. Theor. Angew. Limnol. 1958, 9, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trégouboff, G.; Rose, M. Manuel de Planctonologie Méditerranéenne; CNRS: Paris, France, 1978; Volume 1, p. 587. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, J.D.; Hart-Jones, B. Marine Dinoflagellates of the British Isles; Her Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sournia, A. Atlas du Phytoplancton Marin. Volume 1: Introduction, Cyanophycées, Dictyophycées, Raphidophycées; CNRS: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ricard, M. Atlas du Phytoplancton Marin. Volume 2: Diatomophycées; CNRS: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chrétiennot-Dinet, M.J. Atlas du Phytoplancton Marin. Volume 3: Chlorarachniophycées, Prasinophycées, Eugléniophycées, Chlorophycées; CNRS: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sournia, A.; Chrétiennot-Dinet, M.J.; Ricard, M. Marine phytoplankton: How many species? J. Plankton Res. 1991, 13, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia-Kéfi, O.D.; Souissi, S.; Gomez, F.; Yahia, M.D. Spatio-temporal distribution of the dominant diatom and dinoflagellate species in the Bay of Tunis (SW Mediterranean Sea). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2005, 6, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G.; Larsen, J.; Moestrup, O. Phylogeny of some of the major genera of dinoflagellates based on ultrastructure and partial LSU rDNA sequence data, including the erection of three new genera of unarmoured dinoflagellates. Phycologia 2000, 39, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoid, C.A.; Swezy, O. The Free-Living Unarmored Dinoflagellata; Memoirs of the University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1921; Volume 5, pp. i–viii, 1–562. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J. Unarmoured dinoflagellates from Australian waters I. The genus Gymnodinium (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae). Phycologia 1994, 33, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balech, E. El género Protoperidinium Bergh 1881 (Peridinium Ehrenberg 1831, partim). Rev. Mus. Argent. Cienc. Nat. Bernardino Rivadavia Inst. Nac. Invest. Cienc. Nat. (Hidrobiología) 1974, 4, 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Abé, T.H. Report on the biological survey of Mutsu Bay. Sci. Rep. Tohoku Imp. Univ. 1927, 2, 383–438. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, J.D. Prorocentrum Cordatum (Ostenfeld) J.D. Dodge, 1976; World Register of Marine Species: Oostende, Belgium, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, C.G. Dritter Beitrag zur Erkenntniss grosser Organisation in der Richtung des kleinsten Raumes. Abh. Königl. Akad. Wiss. Berlin 1833, 1833, 145–336. [Google Scholar]

- Schütt, F. Die Peridineen der Plankton-Expedition; Ergebnisse der Plankton-Expedition der Humboldt-Stiftung: Kiel, Germany, 1895; Volume 4, pp. 1–170. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, J. Über neue Prorocentrum-und Exuviella-Arten aus der Adria. Arch. Protistenkd. 1918, 38, 250–262. [Google Scholar]

- Balech, E. The Genus Alexandrium Halim (Dinoflagellata); Sherkin Island Marine Station: Sherkin Island, Ireland, 1995; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Steidinger, K.A.; Balech, E. Scrippsiella subsalsa (Ostenfeld) comb. nov. (Dinophyceae) with a discussion on Scrippsiella. Phycologia 1977, 16, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honeywill, C. A study of British Licmophora species and a discussion of its morphological features. Diatom Res. 1998, 13, 221–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heurck, H. A Treatise on the Diatomaceae; William Wesley & Son: London, UK, 1896; p. 558, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Castracane, F. Report on the diatomaceae collected by H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–1876. Rep. Sci. Results Voyag. H.M.S. Chall. 1886, 2, 1–178. [Google Scholar]

- Manguin, E. Les Diatomées de la Terre Adélie Campagne du Commandant Charcot 1949–1950. Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. 1960, 12, 223–363. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A. Die in den Grundproben der Nordseefahrt vom 21 Juli bis 9 Sept 1872 enthaltenen Diatomaceen. Erste Folge. Jahresber. Komm. Unters. Deutsch. Meer. 1874, 2, 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cleve, P.T.; Möller, J.D. Diatoms. Part IV, No. 169–216; Esaias Edquists Boktryckeri: Upsala, Sweden, 1879; No. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Riaux-Gobin, C.; Romero, O.E.; Coste, M.; Galzin, R. A new Cocconeis (Bacillariophyceae) from Moorea Island, Society Archipelago, South Pacific Ocean with distinctive valvocopula morphology and linking system. Bot. Mar. 2013, 56, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereschkowsky, C. Liste des Diatomées de la mer Noire. Scripta Bot. (Botanisheskia Zapiski) 1902, 19, 51–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenberg, C.G. Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Berlin; Verlag der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Commission bei Georg Reimer: Berlin, Germany, 1875. [Google Scholar]

- Kützing, F.T. Species Algarum; F.A. Brockhaus: Leipzig, Germany, 1849; pp. vi–922. [Google Scholar]

- Armi, Z.; Milandri, A.; Turki, S.; Hajjem, B. Alexandrium catenella and Alexandrium tamarense in the North Lake of Tunis: Bloom characteristics and the occurrence of paralytic shellfish toxin. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 36, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, I.; Bouchouicha, D.; Mabrouk, H.H.; Hlaili, A.S. Driving factors of the potentially toxic and harmful species of Prorocentrum Ehrenberg in a semi-enclosed Mediterranean lagoon (Tunisia, SW Mediterranean). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2013, 14, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchouicha Smida, D.; Sahraoui, I.; Grami, B.; Hadj Mabrouk, H.; Sakka Hlaili, A. Population dynamics of potentially harmful algal blooms in Bizerte Lagoon, Tunisia. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 39, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illoul, H.; Masó, M.; Fortuño, J.M.; Cros, L.; Morales-Blake, A.; Seridji, R. Potentially harmful microalgae in coastal waters of the Algiers area (Southern Mediterranean Sea). Cryptogam. Algol. 2008, 29, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, P.; Siano, R.; Souchu, P.; Collin, K.; Schmitt, A.; Manach, S.; Schapira, M. Spatio-temporal dynamics and biogeochemical properties of green seawater discolorations caused by the marine dinoflagellate Lepidodinium chlorophorum along the southern Brittany coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 275, 107950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, N.; Simon, N.; Sourisseau, M. Temporal and spatial distribution of Lepidodinium chlorophorum blooms in French coastal waters. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2022, 686, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Honsell, G.; Talarico, L. First record of Gymnodinium chlorophorum (Dinophyceae) bloom in the Adriatic Sea identified by electron microscopy. Bot. Mar. 2004, 47, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrich, A.; Toro, J.E.; Navarro, J.M. Thermal stress and coastal eutrophication as drivers of Lepidodinium blooms in the Southern Hemisphere. Harmful Algae 2024, 130, 102597. [Google Scholar]

- Serre-Fredj, L.; Jacqueline, F.; Navon, M.; Izabel, G.; Chasselin, L.; Jolly, O.; Claquin, P. Coupling high frequency monitoring and bioassay experiments to investigate a harmful algal bloom in the Bay of Seine (French-English Channel). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourisseau, M.; Jegou, K.; Lunven, M.; Quere, J.; Gohin, F.; Bryere, P. Distribution and dynamics of two species of Dinophyceae producing high biomass blooms over the French Atlantic shelf. Harmful Algae 2016, 53, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sournia, A.; Belin, C.; Billard, C.; Catherine, M.; Fresnel, J.; Lassus, P.; Soulard, R. The repetitive and expanding occurrence of a green bloom-forming dinoflagellate (Dinophyceae) on the coasts of France. Cryptogam. Algol. 1992, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, H.W.; Xu, H.; McCarthy, M.J.; Zhu, G.; Qin, B.; Li, Y.; Gardner, W.S. Controlling harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a hyper-eutrophic lake (Lake Taihu, China): The need for a dual nutrient (N and P) management strategy. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Paerl, H.W.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G.; Gao, G. Nitrogen and phosphorus inputs control phytoplankton growth in eutrophic lake. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiao, J.J.; Luo, X. The dynamics of dissolved inorganic nitrogen species mediated by fresh submarine groundwater discharge and their impact on phytoplankton community structure. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chislock, M.F.; Doster, E.; Zitomer, R.A.; Wilson, A.E. Eutrophication: Causes, consequences, and controls in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2013, 4, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.S.; Newell, S.E.; McCarthy, M.J.; Hoffman, D.K.; Lu, K.; Lavrentyev, P.J.; Paerl, H.W. Community biological ammonium demand: A conceptual model for cyanobacteria blooms in eutrophic lakes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7785–7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piranti, A.S.; Wibowo, D.N.; Rahayu, D.R. Nutrient determinant factor of causing algal bloom in tropical lake (case study in Telaga Menjer Wonosobo, Indonesia). J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, L.V.; Koseff, J.R.; Monismith, S.G.; Cloern, J.E.; Thompson, J.K. Processes governing phytoplankton blooms in estuaries. II: The role of horizontal transport. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 187, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KM, G.S.; Ons, K.D.Y.; Raja, B.; Nejib, D.Y.M. Phytoplankton and zooplankton diversity and community dynamics in connected coastal wetlands’ ecosystems under anthropogenic pressure (SW Mediterranean Sea). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2025, 314, 109147. [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte, J.L.; Quiñones, R.A.; González, R.R. Relationship between biomass and enzymatic activity of a bloom-forming dinoflagellate (Dinophyceae) in southern Chile (41° S): A field approach. J. Plankton Res. 2005, 27, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchman, E.; Klausmeier, C.A.; Yoshiyama, K. Contrasting size evolution in marine and freshwater diatoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 2665–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobler, C.J.; Doherty, O.M.; Hattenrath-Lehmann, T.K.; Griffith, A.W.; Kang, Y.; Litaker, R.W. Ocean warming since 1982 has expanded the niche of toxic algal blooms in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4975–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, D.; Garcia-Gorriz, E.; Stips, A. Understanding the causes of recent warming of Mediterranean waters. How much could be attributed to climate change? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winder, M.; Sommer, U. Phytoplankton response to a changing climate. Hydrobiologia 2012, 698, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. Unveiling the impact of glycerol phosphate (DOP) in the dinoflagellate Peridinium bipes by physiological and transcriptomic analysis. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Lin, X.; Li, L.; Lin, L.; Zhang, C.; Lin, S. Transcriptomic and physiological analyses of the dinoflagellate Karenia mikimotoi reveal non-alkaline phosphatase-based molecular machinery of ATP utilization. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 4506–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalley, G.W.; Coats, D.W.; Stoecker, D.K. Feeding the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Ceratium furca is influenced by intracellular nutrient concentrations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 262, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, C.L.; Alvarez-Fernandez, S.; Cunha-Dupont, A.; Geisen, C.; Malzahn, A.M.; Boersma, M.; Wiltshire, K.H. The craving for phosphorus in heterotrophic dinoflagellates and its potential implications for biogeochemical cycles. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018, 63, 1774–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, A.T. Photoprotective physiological and biochemical responses of aquatic organisms. In UV Effects in Aquatic Organisms and Ecosystems; Helbling, E.W., Zagarese, H.E., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hutchins, D.A.; Fu, F.; Gao, K. Effects of ultraviolet radiation on photosynthetic performance and N2 fixation in Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 4455–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellyn, C.A.; Airs, R.L. Distribution and abundance of MAAs in 33 species of microalgae across 13 classes. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 1273–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Castenholz, R.W. Occurrence of UV-absorbing, mycosporine-like compounds among cyanobacterial isolates and an estimate of their screening capacity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, D.B.; Connan, S.; Popper, Z.A. Algal chemodiversity and bioactivity: Sources of natural variability and implications for commercial application. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, H. Phytoplankton responses to solar UVR and its combination with nutrient enrichment in a plateau oligotrophic Lake Fuxian: A mesocosm experiment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 23271–23285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoval, M.A.; Villafañe, V.E.; Helbling, E.W. Interactive effects of ultraviolet radiation and nutrient addition on growth and photosynthesis performance of four species of marine phytoplankton. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2007, 89, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlini, G.; Zattera, A.; Bruschi, A. Structural analysis of phytoplankton community’s variation in the Archipelago of La Maddalena (North Sardinian coast): A canonical correlation approach. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1983, 70, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feki-Sahnoun, W.; Njah, H.; Barraj, N.; Mahfoudhi, M.; Akrout, F.; Rebai, A.; Bel Hassen, M.; Hamza, A. Influence of phosphorus-contaminated sediments on the abundance of potentially toxic phytoplankton along the Sfax coasts (Gulf of Gabes, Tunisia). J. Sediment. Environ. 2019, 4, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, L.; Ben Brahim, M.; Hamza, A.; Mahfoudhi, M.; Bradai, M.N. A comparison of abundance and diversity of epiphytic microalgal assemblages on the leaves of the seagrasses Posidonia oceanica (L.) and Cymodocea nodosa (Ucria) Asch in Eastern Tunisia. J. Mar. Biol. 2014, 2014, 275305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).