Abstract

Straw return plays a pivotal role in sustaining soil fertility and crop production, but the interaction between straw return and consecutive fertilizer applications on yield sustainability and soil quality under climate change are unclear. Therefore, a long-term field experiment (2005–2022) was conducted to examine how straw return and fertilizer application improve soil properties, increase crop production, enhance the ability to resist climatic changes, and thus improve yield sustainability in a rice (Oryza sativa L.)–wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cropping system. This study established five treatments, including the control, NPK treatment, S treatment, NPK + 1/2S treatment, and NPK + S treatment. Compared with the control, the treatments involving chemical fertilization combined with straw return increased on average rice and wheat yield by 52.9% and 95.4%, respectively, with higher values of the sustainable yield index (SYI) and lower values of the coefficient of variance (CV) for the two crops. Moreover, the treatments that combined chemical fertilization with straw return improved soil quality by increasing soil organic matter (SOM), total N, total P, and available K contents and presented a higher soil quality index (SQI) value compared to the other three treatments. The crop yield, SYI, and apparent nutrient balance increased with increasing SQI. The SOM and AP were identified as the most crucial soil fertility indices, exerting a significant impact on crop yields. Meanwhile, precipitation emerged as the key meteorological factor restricting the yield of winter wheat. The PLS-SEM suggested that fertilizer application, climatic conditions, and soil properties strongly influenced crop yield, and the magnitude of this influence varies between rice and wheat. In conclusion, the long-term fertilization combined with straw return represents an effective strategy to safeguard the sustainability of crop yields under climate change.

1. Introduction

The rice (Oryza sativa L.)–wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) rotation is the most important crop rotation system in East Asia [1]. It plays a pivotal role in global food production, contributing over 20% of the world’s food supply [2]; it follows that the consistent high yields of rice–wheat rotation systems are instrumental in upholding food security from the regional to the global level [3]. In China, this typical rotation is dominant in the middle Yangtze River Basin, contributing to approximately 30% of the grain production [4]. The rice–wheat rotation is characterized by the cultivation of rice during the summer season and wheat in winter, which is highly congruent with the local climate, featuring high temperatures and abundant precipitation in summer. However, the average wheat yield in this region is only 4.66 t ha−1, which is significantly lower than that of other regions in China. Therefore, this area is a typical low-yield region for wheat in the country [5]. Exploring the underlying causes of low wheat yield in this region and proposing appropriate countermeasures is crucial for ensuring China’s food security.

Improving both crop productivity and its long-term sustainability, along with upgrading soil quality, constitutes a critical method in sustainable agriculture; such an approach is also indispensable for coping with adverse climatic conditions [6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that straw incorporation into soil shows positive effects on crop yield, yield sustainability, and soil fertility [7,8]. By improving soil’s physical, chemical, and biological traits, straw return effectively enhances soil quality. Primarily, straw return improves soil structure, improves soil aggregation structure, and increases the soil water retention capacity [9]. Further, straw decomposition releases nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, improving the supply of available nutrients in the soil [10]. Straw incorporation also increases the abundance of microorganisms, and consequently, the improved turnover of soil nutrients [11,12]. These findings suggest that straw return enhances soil fertility and is beneficial for sustainable crop production [8].

Globally, the weather conditions are intricate and unpredictable, with extreme weather events occurring frequently [13]. A previous study has indicated that weather conditions are responsible for more yield losses compared to fertilization regimes and soil fertility conditions [14]. In this regard, specific studies have demonstrated that wheat yield decreased when the precipitation exceeded a certain threshold [15,16].

In such a scenario, straw addition can optimize the soil pore structure, and this optimization can enhance the soil’s capacity to regulate water infiltration, enabling the soil to better manage the entry and movement of water within its matrix [17]. Consequently, straw addition has the potential to mitigate the yield losses induced by excessive precipitation. Previous studies have also demonstrated that crop yields are largely related to crop breeding and soil fertility, besides the climate conditions. Incorporating crop straw into the soil has the potential to boost soil organic matter accumulation and alleviate the adverse effects of climate change [18]. The study by Li et al. [19] found that straw addition improved soil quality and crop yield, while few studies have investigated the influence of long-term fertilization measures on the capacity to cope with climatic changes. The factors that contribute to the variations in the adaptability of different fertilization measures to climatic changes still remain ambiguous. Therefore, an 18-year field experiment was conducted to evaluate the effects of straw return and fertilizer application on soil properties, crop production, and the ability to resist climatic changes, all of which ultimately have a bearing on yield sustainability. The main objectives of this study were (i) to investigate yield and yield sustainability responses to straw return with fertilization in rice–wheat rotation cropping systems, especially to address the low yield of wheat in the middle Yangtze River Basin; (ii) to assess the variation in yield as affected by soil properties and climatic conditions; and (iii) to identify the key factors regulating yield in typical rice–wheat cropping systems. Through a detailed examination of the complex interactions among soil, climate, and agricultural management practices, these objectives aim to provide targeted recommendations for optimizing crop yields and promoting sustainable agricultural development in a rice–wheat system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site Description

A long-term field experiment was conducted in Liuzhou village, Qianjiang County, Hubei Province, China (30°22′55.1″ N, 112°37′15.4″ E). The study site has a temperate monsoon climate, characterized by an average annual precipitation of 1741.3 mm and a mean annual temperature of 16.6 °C. The experiment started in October 2005 and involved a rice–wheat cropping system. The soil type was fluvo–aquic, with a silty clay loam texture (15.3% sand, 52.3% silt, and 32.4% clay). Prior to start of the experiment, topsoil (0–20 cm) was collected for the analysis of physicochemical characteristics. The physicochemical characteristics of the topsoil at the beginning of the experiment were: 20.6 g kg−1 of soil organic matter (SOM), 1.53 g kg−1 of total nitrogen content, 7.1 of soil pH, 19.2 mg kg−1 of Olsen-P, 59.1 mg kg−1 of exchangeable K content, 636.0 mg kg−1 of nonexchangeable K content, 17.1 g kg−1 of total K content, and 14.9 cmol kg−1 of cation exchange capacity (CEC). Additionally, the precipitation, sunshine duration (SD), humidity, average temperature (AT), minimum temperature (MinT), and maximum temperature (MaxT) were calculated and recorded for the growing season of rice and wheat from 2005 to 2022. The weather conditions during the experiment were 635.6 mm of precipitation, 828.2 h of SD, 78.8% of humidity, 25.0 °C of AT, 21.6 °C of MinT, and 29.3 °C of MaxT on average during the rice growing season and 517.2 mm of precipitation, 782.2 h of SD, 75.2% of humidity, 11.6 °C of AT, 7.8 °C of MinT, and 16.2 °C of MaxT on average during the wheat growing season. Detailed information is presented in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Experimental Design and Field Management

The field experiment started in 2005 and lasted 18 years. Five treatments were arranged in a completely randomized block design with four replicates: (1) a control with no chemical fertilizer supply (CK); (2) a chemical fertilizer supply (NPK) treatment, with 150 kg N ha−1, 90 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 90 kg K2O ha−1 in the rice season and 120 kg N ha−1, 75 kg P2O5 ha−1, and 60 kg K2O ha−1 in the wheat season; (3) a treatment with continuous 6000 kg ha−1 straw return and without chemical fertilization each season (S); (4) a treatment with NPK supply with 3000 kg ha−1 straw return (NPK + 1/2S); and (5) a treatment with NPK supply with 6000 kg ha−1 straw return (NPK + S). The size of each plot was 20 m2 (4 m × 5 m). The fertilizers used were urea (46% N), calcium superphosphate (12% P2O5), and potassium chloride (60% K2O), and the rates of chemical fertilizer were 326 kg urea ha−1, 750 kg superphosphate ha−1, and 150 kg potassium chloride ha−1 in the rice season and 261 kg urea ha−1, 625 kg superphosphate ha−1, and 100 kg potassium chloride ha−1 in the wheat season. All fertilizers, except for the urea, were used as base fertilizers, and 40% of the urea was used as two top dressings. Regarding straw return, the straw was crushed into 2–3 cm pieces, allowed to decompose for two weeks, and then incorporated into the soil before rice transplanting or wheat sowing. Rice was bred in April, transplanted in May, and harvested in October of the same year, and wheat was sown in November and harvested in April of the following year. Rice was transplanted at a spacing of 0.17 m × 0.26 m after 30 days of seeding. One week before the rice transplanting, plots were irrigated, and a surface water depth of 2–3 cm was maintained. Wheat was planted with an equal row spacing of 0.15 m, and the sowing density was 112.5 kg ha−1. The rice and wheat varieties used were Guangliangyouxiang 5 and Zhengmai 9023, respectively. Field management practices, such as those related to pest and disease prevention, were uniform for all plots and based on local practices.

2.3. Sampling and Analysis

At crop maturity each season, six representative plants were sampled from each plot. The biomass and nutrients of each part (straw and grain) were measured. All plant samples were dried at 60 °C and then ground into powder for chemical analysis. The plant nutrient content was determined via digestion with H2SO4-H2O2, while the N, P, and K contents were tested by flow injection analyzer (SEAL Analytical GmbH, Norderstedt, Germany) and flame photometry (Cole-Parmer, Chicago, IL, USA). Crop yield was calculated by harvesting a 10 m2 portion from each plot.

After crop harvest, the topsoil (0–20 cm) was collected for soil nutrient analysis in each plot. Approximately 1 kg of soil was collected from six randomly selected spots and mixed evenly. Air-dried soil samples were ground and passed through 1 mm and 0.149 mm sieves prior to physicochemical analyses. Soil pH was determined with a pH meter in deionized water at a ratio of 2.5:1 (v/w). Soil organic matter (SOM) was measured via the Walkley–Black dichromate oxidation method, and total N (TN) and available N (AN) were determined via the Kjeldahl method and the alkaline hydrolysis method. Total P (TP) was determined by digestion with HClO4-H2SO4, AP was extracted with 0.5 mol L−1 NaHCO3, and the solutions were analyzed via the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method. Total K (TK) and available K (AK) were extracted with boiling NaOH and 1 mol L−1 neutral NH4OAc, respectively, and the extract was tested by flame photometry.

2.4. Calculations

2.4.1. Yield Sustainability

The sustainable yield index (SYI) and coefficient of variance (CV) of crop yield were adopted to evaluate the stability and sustainability of rice–wheat cropping systems, with calculations for both indices presented below following previously established methods [14,20]:

where is the average yield, Ymax is the maximum yield for rice and wheat, and represents the standard deviation of the yield.

2.4.2. Apparent Nutrient Balance

The apparent nutrient balance was calculated as the difference between inputs from the fertilizer and output from crop harvest, and the following equation was used [21]:

where F input and S input are the amounts of N/P/K input from fertilizer and straw, respectively, and H output is the amount of N/P/K output from crop harvest, including straw and grain.

Apparent N/P/K balance (kg ha−1) = F input + S input − H output

2.4.3. Method for Calculating Soil Quality Index

The soil quality index (SQI) was calculated according to the methods reported in Shang et al. [22] and Zhang et al. [23]. A three-step procedure was used to obtain the SQI: (i) select soil parameters for SQI analysis; (ii) calculate the weight of each soil parameter and obtain a score; and (iii) calculate the final SQI value by integrating all the parameter scores. In our study, 8 parameters, including soil pH, SOM, TN, TP, TK, AN, AP, and AK, were selected for SQI evaluation as the previous study suggested [23]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to obtain the weight coefficient.

The SQI was calculated via the following equation:

where Wi represents the weight coefficient of each indicator shown in Table 1, and two components of the PCA explained 92.55% of the variance. According to the weight of each parameter, the SQI equation was as follows: SQI = ∑(QpH × 0.164) + (QSOM × 0.171) + (QTN × 0.173) + (QTP × 0.104) + (QTK × 0.173) + (QAN × 0.126) + (QAP × 0.053) + (QAK × 0.176). Qi represents the parameter score calculated via Equations (3) and (4) and n is the total number of parameters. The score value of each fertility parameter was calculated by Shang et al. [22], which was used to calculate the scores for all soil parameters except for pH.

Table 1.

Communality values and total weights of the soil quality indicators based on principal component analysis.

Here, f(x) denotes the parameter score, with a value range of 0.1 to 1.0; x refers to the monitored value of the parameter; and Xmin and Xmax represent its lower and upper threshold values, respectively. Given that soil pH has an optimal range, its corresponding standard scoring function is defined as follows:

Parameters x1, x2, x3, and x4 were assigned values of 4.5, 5.5, 6.5, and 8.5, in that order [22].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 20 (IBM), and significance was determined at the 0.05 level of probability with the least significant difference (LSD) method. All figures were constructed in Origin 8.0 software (Origin Lab Corporation). Linear regression was selected to analyze the relationship among crop yield, SYI, apparent nutrient balance, and SQI. Relative importance analysis was performed to evaluate the integrative effects of the soil nutrient content and climatic parameters on crop yield via the ‘vegan’ package in R. The ‘plspm’ package was used to construct a partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) via the R statistical software platform (version 3.5.2).

3. Results

3.1. Crop Yield and Yield Sustainability

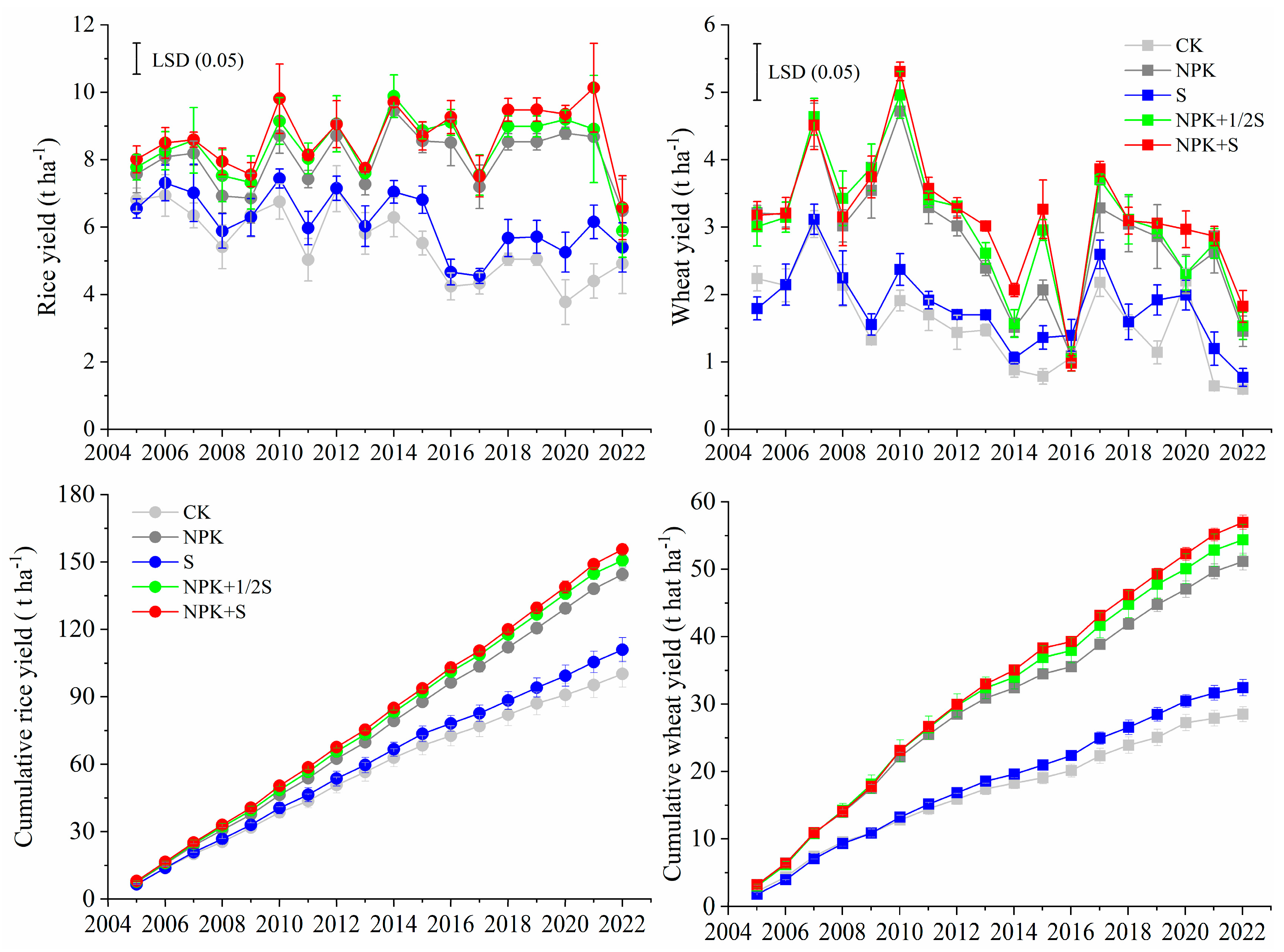

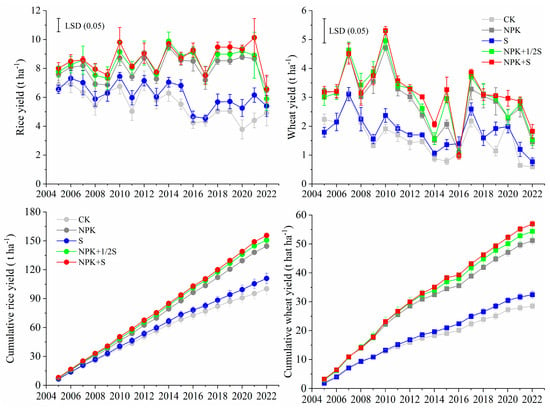

Simultaneous application of long-term fertilization and straw return increased crop yield in the rice–wheat cropping system. Crop yield clearly differed among the different treatments over the eighteen years and the NPK + S treatment resulted in a relatively high yield in the cropping system (Figure 1). Compared with those of the control (CK treatment), the rice yields of the NPK and S treatments increased by an average of 44.3% and 10.7%, respectively, and the wheat yields increased by an average of 79.5% and 13.8%, respectively. The crop yield further increased after fertilization and straw return, and the yield increased by an average of 52.9% (50.4% for NPK + 1/2S and 55.3% for NPK + S) and 95.4% (90.8% for NPK + 1/2S and 99.9% for NPK + S) for rice and wheat, respectively, compared with that of the control.

Figure 1.

Yield and cumulative yield in different treatments over the 18-year period from 2005 to 2022. Notes: Least significant difference (0.05) (LSD 0.05) is the least significant difference among treatments in a sampling year at p < 0.05.

Fertilizer application and straw return increased the SYI of rice and wheat, and the coefficient of variance (CV) of the rice and wheat yields decreased (Table 2). Compared with the control, the SYI of the NPK, S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments increased by an average of 19.8%, 12.1%, 18.2%, and 19.4% for rice yield, respectively. For wheat yield, their SYI increased by 55.4%, 29.0%, 59.4%, and 70.2%, respectively. In contrast, for rice yield, the CVs of the NPK, S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments decreased by an average of 44.2%, 24.3%, 38.5%, and 39.9%, respectively. For wheat yield, their CVs decreased by 20.3%, 24.9%, 21.5%, and 28.7%, respectively.

Table 2.

Sustainability yield index and coefficient of variance (CV) for rice (Oryza sativa L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) yields over the 18-year study period.

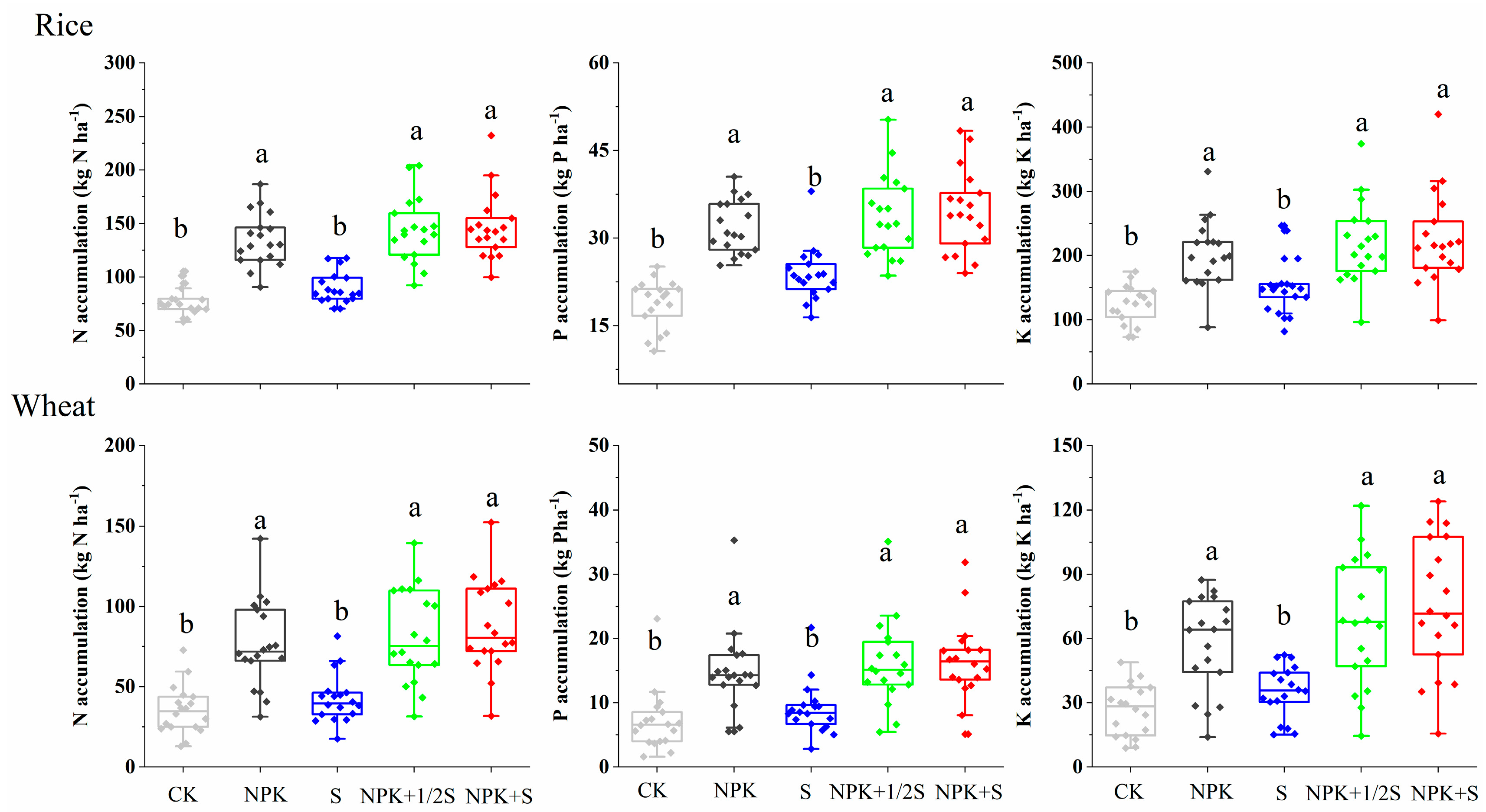

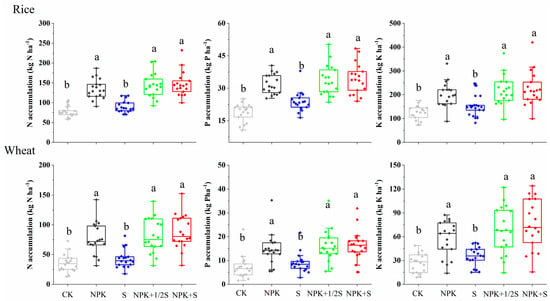

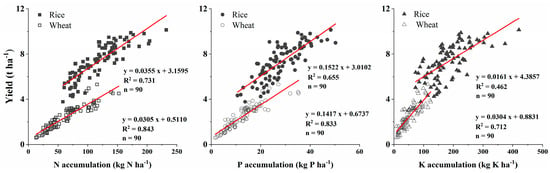

3.2. Nutrient Accumulation, Apparent Nutrient Balance, and Its Relationship with Crop Yield

The N, P, and K accumulation significantly differed after long-term fertilizer application and straw return (Figure 2). Similarly to the trends in crop yield, fertilizer application alone and fertilization and straw return significantly increased N, P, and K uptake in both rice and wheat. The NPK, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments showed the greatest N, P, and K accumulation in the rice–wheat cropping system. The S treatment performed similarly to the CK treatment. Compared with the control, the NPK, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments significantly enhanced nutrient accumulation. N accumulation in rice increased by 75.1% (NPK), 86.8% (NPK + 1/2S), and 90.8% (NPK + S), while wheat showed corresponding increases of 147.5%, 129.2%, and 147.5% for the same treatments. P accumulation in rice rose by 69.8%, 78.9%, and 83.1%, and in wheat by 110.8%, 125.5%, and 132.6%. K accumulation in rice increased by 38.8%, 43.6%, and 48.9%, with wheat exhibiting increases of 53.7%, 72.8%, and 84.1% under the NPK, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments, respectively. The relationship between crop yield and nutrient accumulation revealed that yield increased linearly with increasing N, P, and K accumulation (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

N, P, and K accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under different treatments from 2005 to 2022. Notes: The values in the figure were analyzed after each two-year rice harvest. Lowercase letters (a, b) indicate significant differences among the treatments based on the LSD test (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Linear regression analyses between the nutrient accumulation (N, P, and K) and crop yield.

The nutrient balance over an 18-year period is presented in Table 3. CK and S treatments resulted in N and P depletion, whereas treatments with chemical fertilization (i.e., NPK, NPK + 1/2S, NPK + S) resulted in N and P surpluses. The NPK, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments resulted in average N surpluses of 59.0, 82.6, and 111.0 kg ha−1 y−1, and in average P surpluses of 25.0, 27.8, and 31.8 kg ha−1 y−1 of P, respectively. In terms of the K balance, the CK, NPK, and S treatments resulted in a K depletion of 161.9, 148.7, and 51.1 kg ha−1 y−1, respectively, whereas the S and NPK + S treatments resulted in K surpluses of 49.2 and 58.3 kg ha−1 y−1, respectively. However, the highest values of N, P, and K balances were observed in the NPK + S treatment.

Table 3.

Nutrient balance of the different treatments over an 18-year period (2005–2022).

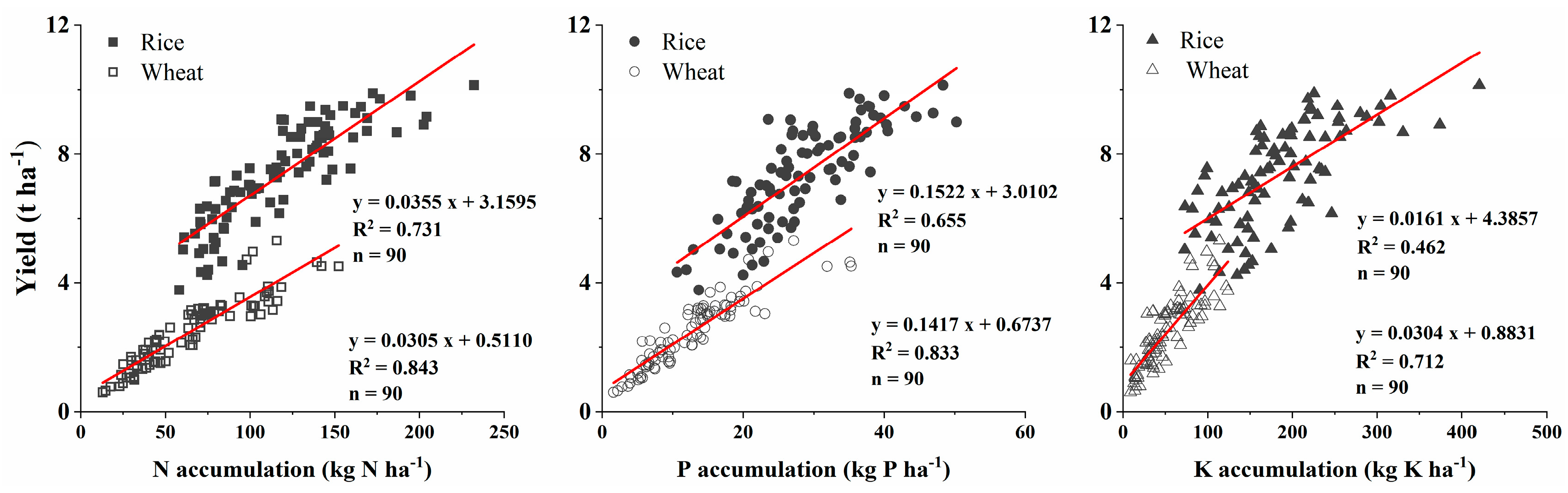

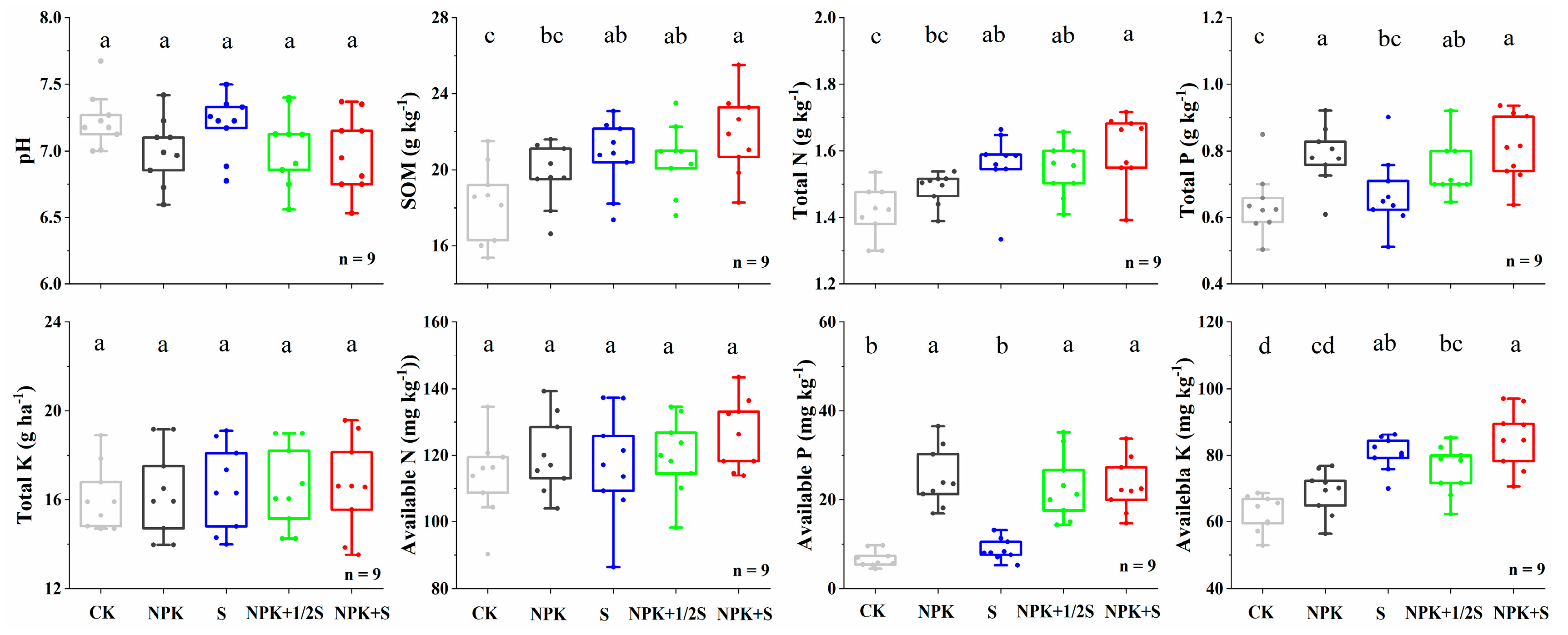

3.3. Soil Chemical Properties

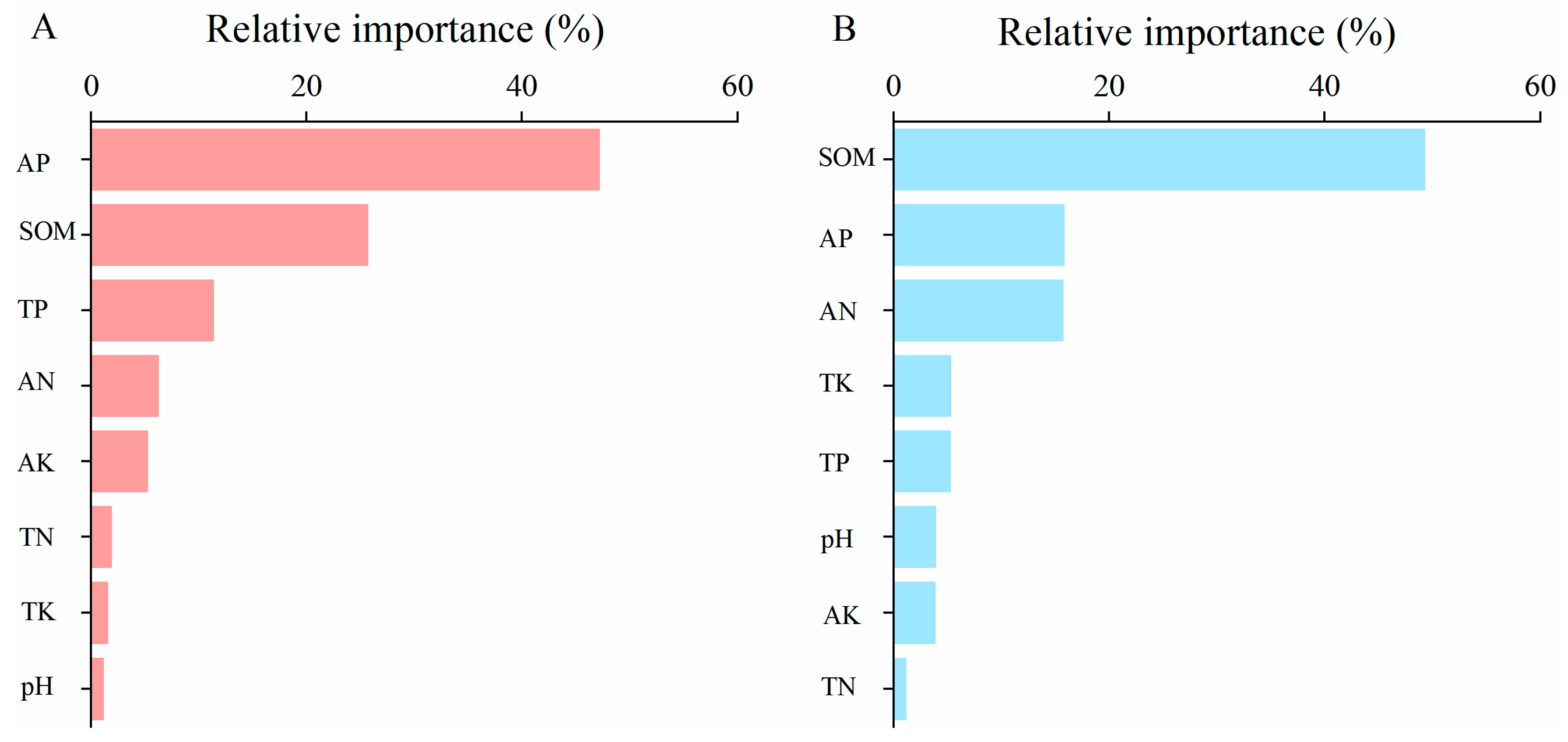

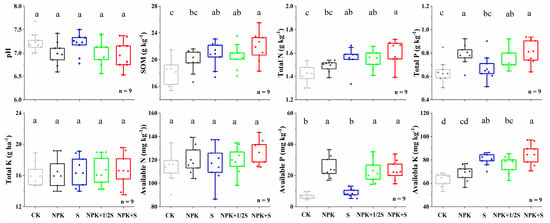

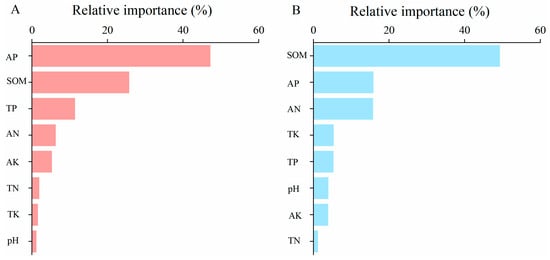

Significant differences in the soil chemical properties over an 18-year period were recorded among the treatments (Figure 4). No significant differences were detected among treatments in soil pH, total K, and available N. However, significant differences were observed in the SOM, total N, total P, available P, and available K contents, and the NPK + S treatment produced the highest values among all the treatments. Compared with the control, the SOM in the NPK, S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments increased by an average of 8.1%, 13.6%, 12.7%, and 19.7%, respectively. Consistent with the results of the SOM, the soil total N presented similar trends among the different treatments, and the control presented the lowest value among all the treatments. Additionally, TP and AP showed similar trends: the treatments with chemical fertilization (i.e., NPK + S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK) presented the highest values. Compared with the control, the TP of the NPK + S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK treatments increased by an average of 25.6%, 17.6%, and 11.3%, respectively, and the available P increased by 248.5%, 244.3%, and 275.3%, respectively. Greater differences were observed among the different treatments in terms of soil available K, and the treatments were ranked as NPK + S, S, NPK + 1/2S, NPK, and CK in ascending order. According to the relative importance analysis (Figure 5), AP and SOM had stronger effects on rice yield than the other soil chemical properties did. However, SOM, AP, and available N had greater effects on wheat yield than the other properties.

Figure 4.

Soil nutrient contents in the different fertilization treatments over the 18-year period from 2005 to 2022. Notes: Lowercase letters (a–d) indicate significant differences among the treatments based on the LSD test (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The relative importance (%) of soil chemical properties for the yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) (A) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (B) based on a relative importance model. The proportions of variance explained by the model were 78.2% for rice and 76.7% for wheat. Notes: AP, available phosphorus; SOM, soil organic matter; TP, total phosphorus; AN, available nitrogen; AK, available potassium; TN, total nitrogen; TK, total potassium.

3.4. Soil Quality Index

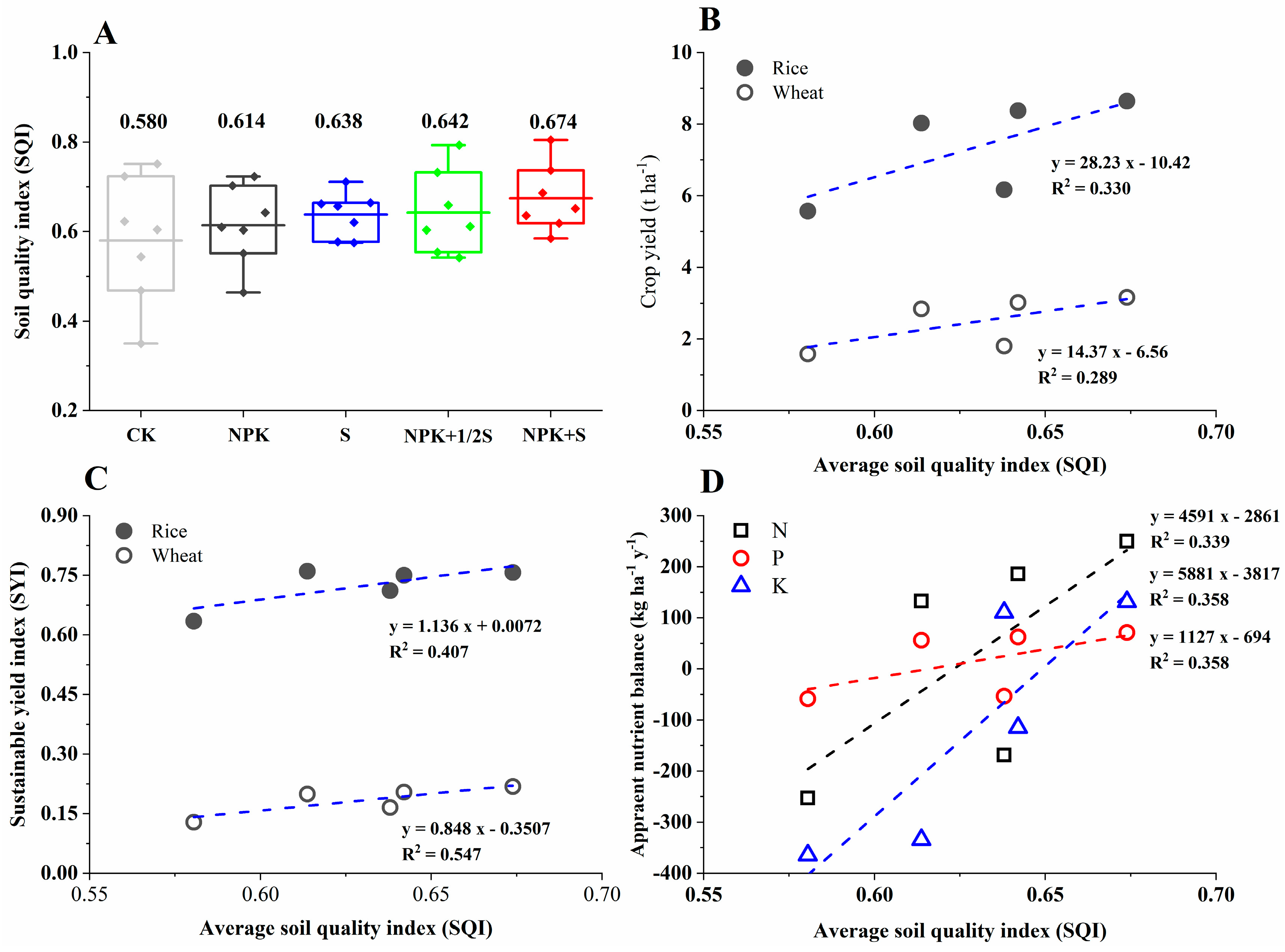

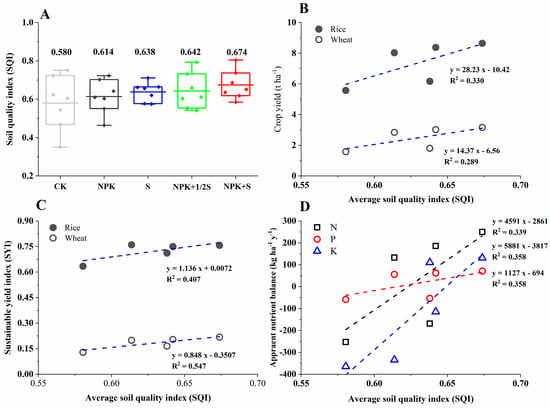

Compared with the control, the SQIs of the NPK, S, NPK + 1/2S, and NPK + S treatments increased by an average of 5.9%, 10.0%, 10.7%, and 16.2%, respectively, in response to long-term fertilization and straw return. The NPK + S treatment presented the highest SQI (Figure 6A). A linear relationship was observed between the average SQI and crop yield, which indicated that rice and wheat yields increased with increasing SQI, although at different rates (Figure 6B). Similarly, a significant linear relationship was found between SQI and SYI of rice (R2 = 0.407) and wheat (R2 = 0.547) (Figure 6C). In addition, the apparent nutrient balance linearly increased with increasing SQI (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

The average soil quality index among the different fertilization treatments (A) and its relationships with crop yield (B), the sustainable yield indices (C), and the apparent nutrient balance (D). Notes: the numbers on the box represent the means of the SQI.

3.5. Climatic Factors and Their Relationship with Crop Yield

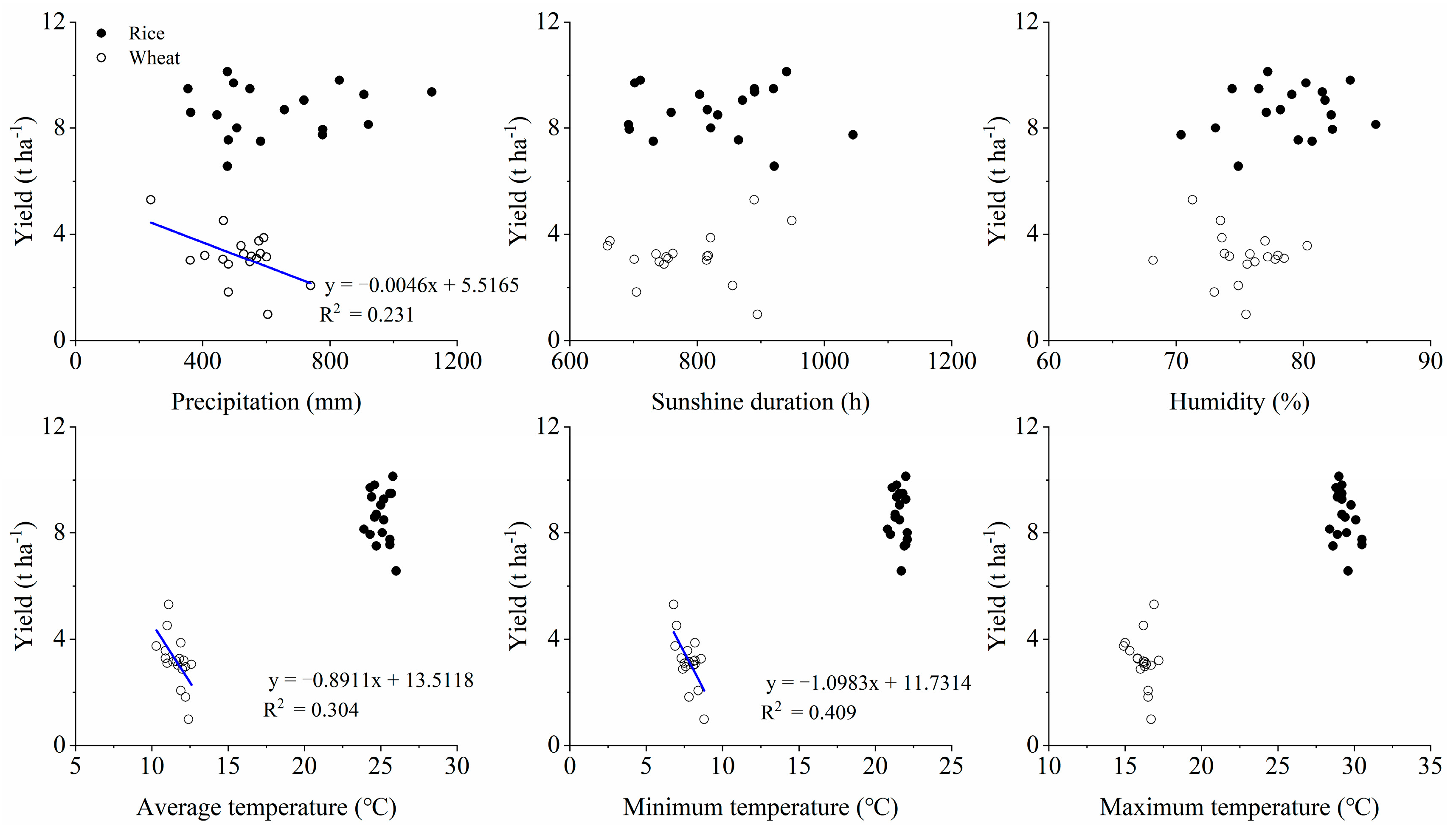

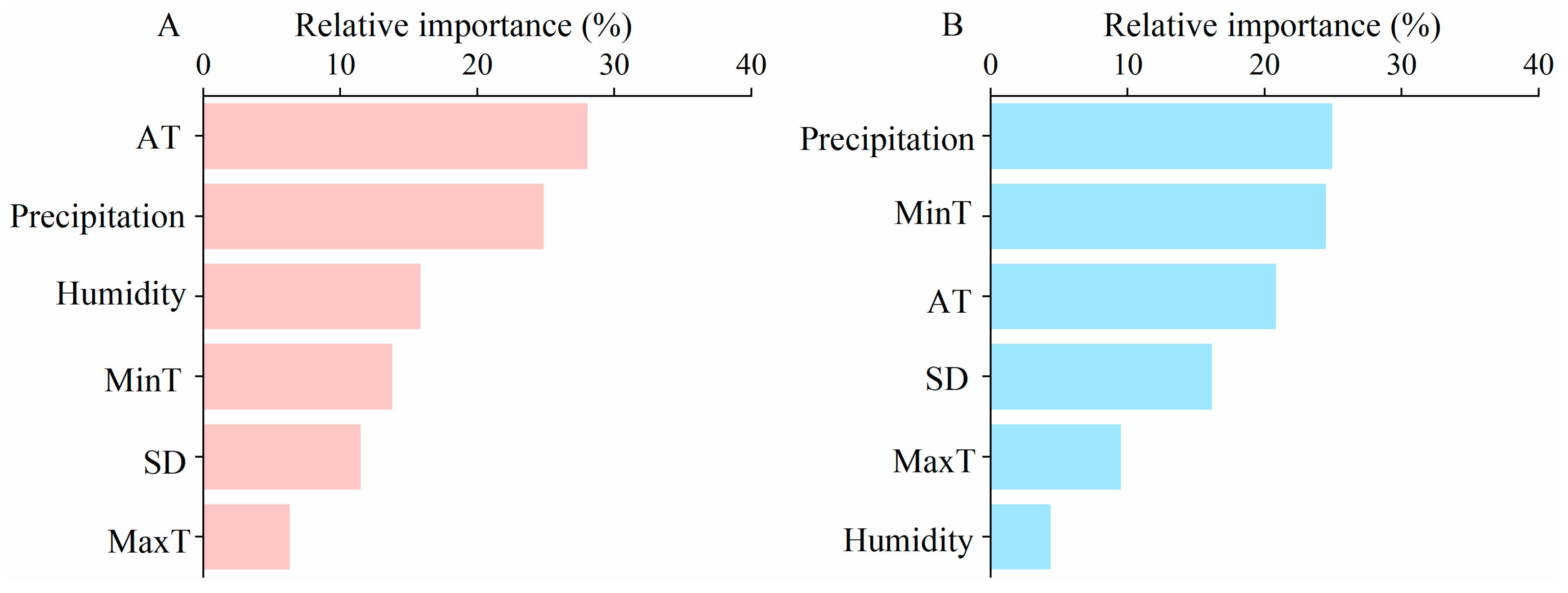

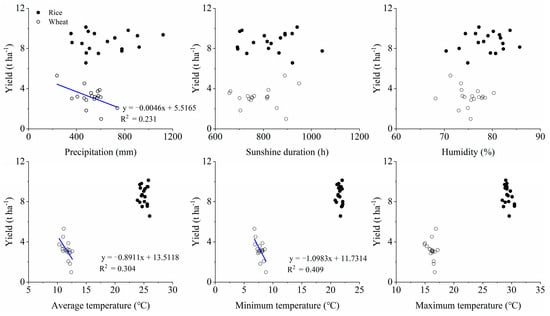

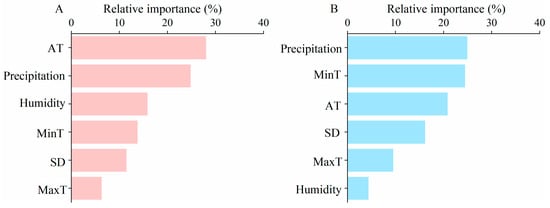

Regression correlation analyses were performed between crop yield and climatic parameters (Figure 7). The results showed a significant negative linear relationship between wheat yield and precipitation, AT, and MinT, indicating that wheat yield increased as these climatic variables decreased, within a certain threshold. However, little correlation was detected between rice yield and climatic parameters. According to the relative importance analysis (Figure 8), the proportions of variance explained by the model were 16.5% for rice and 75.5% for wheat. This is consistent with the absence of significant linear relationships between rice yield and the climatic parameters evaluated. For wheat, precipitation and MinT were the most important factors (24.9% and 24.4%, respectively) controlling yield, followed by AT (20.8%).

Figure 7.

Linear regression analyses between climatic parameters and crop yield.

Figure 8.

The relative importance (%) of climatic parameters for the yield of rice (Oryza sativa L.) (A) and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (B) based on a relative importance model. The proportions of variance explained by the model were 16.5% for rice and 75.5% for wheat. AT, MinT, SD, and MaxT represent the average temperature, minimum temperature, sunshine duration, and maximum temperature, respectively.

3.6. The Comprehensive Effects of Fertilizer, Climatic Factors, and Soil Nutrients on Crop Yield

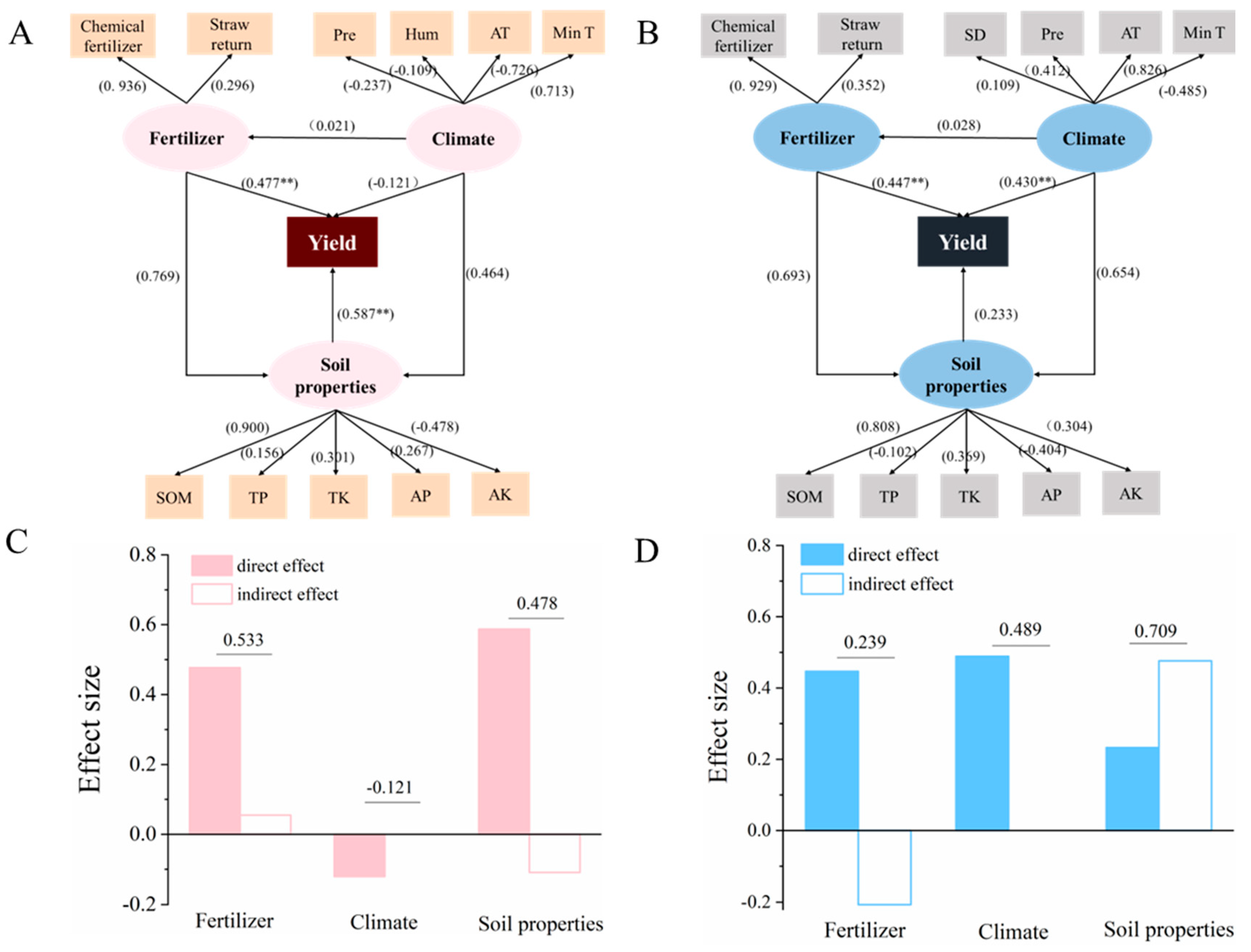

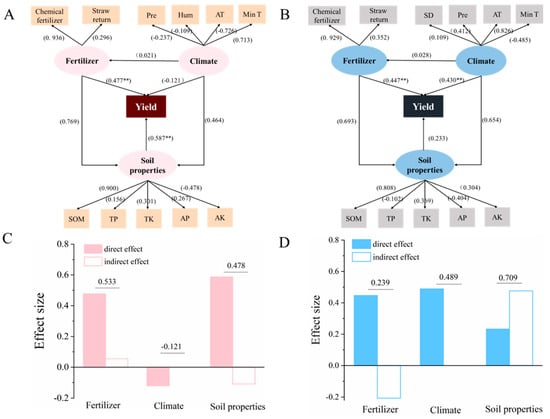

Four climatic parameters and five soil parameters were selected for PLS-SEM analysis, as these parameters were most relevant to crop yield (Figure 9). The PLS-SEM analysis results indicated that fertilization and soil properties had stronger effects than climatic factors for rice growth, according to the factor loading score. Among the variables, the direct path coefficients for the effects of fertilizer application and soil properties on rice yield were 0.477 and 0.587, respectively, while the direct impact of climate on yield was relatively weak. Chemical fertilizers (0.936) were the most representative of fertilizer management; AT and MinT (−0.726 and 0.713, respectively) were the most representative of climatic factors; and SOM was the most representative of soil properties.

Figure 9.

PLS-SEM results for the relationships between different factors and yield and effects of these factors on yield. (A) represents the path model for rice (Oryza sativa L.) (goodness-of-fit value = 0.492); (B) represents the path model for wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) (goodness-of-fit value = 0.470); (C) represents the model effect values for rice; and (D) represents the model effect values for wheat. The numbers on the solid line represent the total effect size. The arrows in figures (A,B) between climate, fertilizer, soil properties, and yield represent the path coefficients, and the other arrows represent the factor load coefficients. The ** indicates significant direct effects at the p < 0.01 level. Notes: Pre, Hum, AT, MinT, and SD represent precipitation, humidity, average temperature, minimum temperature, and sunshine duration. SOM, TP, TK, AP, and AK represent soil organic matter, total phosphorus, total potassium, available phosphorus, and available potassium.

The direct path coefficient for fertilizer application on wheat yield was 0.447, and chemical fertilizers (0.929) were more important than straw return in influencing the effects of fertilizer application (0352). The direct path coefficient for the effects of climatic factors on yield was 0.430, and precipitation, AT, and Min T (0.412, 0.826 and −0.485) were more important than the other climatic parameters were. The direct path coefficient for the effect of soil properties on yield was 0.233, and SOM (0.808) played important roles in soil properties.

The total effect was quantified by the standardized direct and indirect effects of a given latent variable, and the results demonstrated that fertilization (53.3%) had greater effects than soil properties (47.8%) and climate (12.1%) for rice, whereas for wheat, soil properties (70.9%) had greater effects than climate (48.9%) and fertilization (23.9%). These findings indicated that different factors had significant regulating effects on the yield of the two crops.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Fertilization and Straw Return on Crop Yield and Yield Sustainability

The productivity and sustainability of a cropping system depend on its yield potential and yield stability. Previous studies have shown that fertilization combined with straw return in cropping systems can promote primary crop yield, improve soil quality, reduce agricultural inputs, and improve environmental sustainability [24,25]. Chemical fertilization and straw return could improve soil nutrient content and availability, and thus improve crop nutrient uptake, increasing crop yields [26]. In this study, according to the relative importance analysis, AP and SOM played an important role in affecting rice yield, whereas SOM had a greater effect on wheat yield (Figure 5). These results are in agreement with the findings of Zhang et al. [23]. The treatments with chemical fertilization (with or without straw return) significantly improved N, P, and K accumulation in the rice–wheat cropping system. The positive linear correlations demonstrated that crop yield increased with increasing N, P, and K accumulation. Sufficient nutrient uptake directly modulates photosynthate synthesis, translocation, and partitioning [27]. Adequate and balanced absorption of N, P, and K nutrients boost leaf photosynthetic efficiency and root vitality, facilitates efficient dry matter accumulation in grains or harvestable organs, and sustains high and stable crop yields [28]. Previous studies have demonstrated that straw addition increased total plant N uptake by 2.2–12.6% for cotton [29], improved P uptake by 14.0% and 18.3% for rice and rapeseed, respectively [30], and significantly increased K uptake in rice and rapeseed [31]. The results of this study also showed that applying chemical fertilizers (with or without straw return) could increase N, P, and K uptake by crops, thereby improving crop yields.

Yield stability plays an important role in indicating agricultural sustainability [20], and the SYI was used to evaluate the stability and sustainability of crop production [32]. As reported in a previous study, straw return can substantially improve crop yield stability by increasing soil organic C storage [33]. Another study reported that straw incorporation improved the sustainability of rice yield [34]. The current long-term experiment revealed that there were large variations in the interannual yield of rice and wheat among the different treatments. Chemical fertilization was the most effective in improving the yield stability index for both crops, and in the case of wheat, this improvement was further enhanced by the addition of straw. First, fertilizer application and straw addition supplied nutrients for crop uptake, increasing the stability of crop yields. Second, these agricultural practices enhanced soil quality and thus increased crop production resilience to climate change [35].

4.2. Effect of Fertilization and Straw Return on Soil Fertility

The SQI is a quantifiable soil fertility indicator that guides sustainable land use management and yield promotion in agricultural production [22]. Several indicators including soil pH, SOM, AN, AP, AK, and other nutrients, were used to evaluate the SQI [20,23]. In our study, soil pH, SOM, TN, TP, TK, AN, AP, and AK were selected, as these indicators were crucial for soil fertility assessments. The results revealed that long-term fertilization combined with straw return increased the SOM, total N, total P, available P, and available K contents, which were consistent with previous findings [23,36]. Straw return had a positive effect on the SOC content [37]. It provides active C sources and affects soil microorganisms [27]. Such that the microorganisms promote the turnover of soil nutrients, improving soil nutrient availability, especially for N and P [38]. Straw return is widely recognized to improve soil K availability via increasing the amounts of K-containing materials, and also by increasing the adsorption of K by improving the soil aggregate structure [39].

The results revealed that, compared with the treatments without straw return, all treatments involving straw return presented higher SQI values (Figure 6A), indicating that the straw return treatments had better effects on soil fertility than the treatments with chemical fertilizer alone or with no chemical fertilizers. This is in agreement with the findings of Huo et al. [40], who reported that long-term straw return increased the SQI by improving soil biochemical properties and soil enzyme activity related to C, N, and P. Notably, the crop yield and SYI linearly increased with increasing SQI (Figure 6B,C), which indicated that soils of higher quality can ensure high and stable crop yields. In addition, there was a positive linear regression between the apparent nutrient balance and the SQI, which demonstrated that an adequate nutrient supply can improve soil fertility.

4.3. Effect of Climate Parameters on Crop Yield

Climate factors exhibit negligible impacts on rice yield, which aligns with the findings that the yield coefficient of variation (CV) and the CV of rice yield across different treatments over an 18-year period ranges from 10.4% to 18.6% (Table 2). Previous investigations have indicated that extreme climatic events significantly influence rice yield, and a rise in mean temperature leads to yield reduction, while precipitation exceeding 25% triggers yield decline. Rice yield demonstrates a unimodal response to solar radiation, increasing initially and then decreasing with its increment [41]. The wheat yield varied greatly over the years in the experiment, and the CV of wheat ranged from 30.0% to 42.1% over the 18 years (Table 2). A previous study showed that precipitation, temperature, and their interactions could explain 32–39% of yield variation in crops in major global food producing regions [42]. Changes in precipitation and temperature related to climate change can result in a severe reduction in crop production [43]. The relative importance analysis indicated that, compared with other climatic parameters, precipitation exerted a greater influence on wheat yield. Liu et al. [44] demonstrated that excessive rainfall was the key meteorological factor limiting winter wheat yield in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Notably, the minimum temperature (MinT) and the average temperature (AT) also strongly influenced wheat yield, which is in accordance with the research of Asseng et al. [45]. Figure 8 revealed that precipitation and minimum temperature have comparable importance, with average temperature closely following. Additionally, Figure 9 highlights minimum temperature as the most influential factor, as indicated by its highest loading value.

A Penman–Monteith model analysis revealed that the water requirements for winter wheat ranged from 277 mm to 477 mm in southern China during the growing season [15], whereas the average precipitation was 517.2 mm in the middle reaches of Yangtze River, exceeding the demand. As a result, there is too much precipitation in this area for winter wheat, and excessive rainfall further reduces yield [44]. In addition, the high groundwater and soil moisture levels affect the yield of wheat in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Therefore, it is crucial to dig ditches and prevent waterlogging in this region to promote wheat growth.

5. Conclusions

Fertilization combined with straw return represents a core strategy for achieving stable yields, improved soil health, and enhanced resilience in rice–wheat rotation systems under climate change. Compared to no straw return, returning straw increased rice and wheat yields by an average of 52.9% and 95.4%, and increased soil quality index by an average of 13.5%. Central to this is the identification of soil organic matter and available phosphorus as the most critical soil fertility indices driving crop yield, underscoring their indispensable role in determining agricultural productivity within the study area. Additionally, precipitation was identified as the primary meteorological factor impacting winter wheat yield, underscoring the urgency for tailored water management strategies. Beyond short-term productivity gains, this practice lays a foundation for long-term agricultural carbon neutrality and food security by systematically upgrading soil quality. Future research should prioritize technology integration and regional adaptation to facilitate its scaling from experimental plots to broader agricultural landscapes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16030380/s1, Table S1: Climate parameters for the growing season of rice and wheat from October 2005 to April 2023.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z. and X.F.; methodology, F.Z.; formal analysis, Z.Z. and Y.X.; investigation, C.N. and M.W.; data curation, D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Z., Y.X. and D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.Z.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, F.Z. and X.F.; funding acquisition, D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42407486) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M731037).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Timsina, J.; Connor, D.J. Productivity and management of rice-wheat cropping systems: Issues and challenges. Field Crops Res. 2021, 69, 93–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Shah, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Peng, S.; Nie, L. Effect of straw returning on soil organic carbon in rice-wheat rotation system: A review. Food Energy Secur. 2020, 9, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Nie, L. Energy assessment of different rice-wheat rotation systems. Food Energy Secur. 2021, 10, e284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Leach, A.M.; Ma, L.; Galloway, J.N.; Chang, S.X.; Ge, Y.; Chang, J. Nitrogen footprint in China: Food, energy, and nonfood goods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 9217–9224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, T.; Li, Y.; Qu, X.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, K.; Du, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; et al. Spatio-temporal evolutions and driving factors of wheat and maize yields in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2022, 38, 100–108, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Yadvinder-Singh; Singh, S.K.; Mishra, R.P.; Shukla, A.K.; Rathore, S.S.; Shekhawat, K.; Majumdar, K.; Jat, M.L. Effect of tillage and crop establishment, residue management and K fertilization on yield, K use efficiency and apparent K balance under rice-maize system in north-western India. Field Crops Res. 2018, 224, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shar, A.G.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, X. Effect of straw return mode on soil aggregation and aggregate carbon content in an annual maize-wheat double cropping system. Soil Tillage Res. 2018, 175, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Lal, R. Corn stover removal impacts on micro-scale soil physical properties. Geoderma 2008, 145, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozier, I.A.; Behnke, G.D.; Davis, A.S.; Nafziger, E.D.; Villamil, M.B. Tillage and Cover Cropping Effects on Soil Properties and Crop Production in Illinois. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.R.; Yadav, P.; Singh, D.; Tripathi, M.K.; Kumar, S. Cropping systems influence microbial diversity, soil quality and crop yields in Indo-Gangetic plains of India. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 212, 126152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.P.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Q.L.; Zhang, S.R.; Wei, W.L.; Ding, X.D. Changes in soil bacterial community and enzyme activity under five years straw returning in paddy soil. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2020, 100, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prein, A.F.; Rasmussen, R.M.; Ikeda, K.; Liu, C.; Clark, M.P.; Holland, G.J. The future intensification of hourly precipitation extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Hu, C.; Chen, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Fan, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z. Crop yield stability and sustainability in a rice-wheat cropping system based on 34-year field experiment. Eur. J. Agron. 2020, 113, 125965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, X.; Li, K.; Zhao, J.; Ye, Q.; Xie, W.; Dong, C.; Liu, H. Analysis of spatial and temporal characteristics of water requirement of winter wheat in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2013, 29, 72–82, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.L.; Shi, J.L.; Shen, Y.L. Climate change and its effect on winter wheat yield in the main winter wheat production areas of China. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 723−734, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.H.; Zhu, D.D.; Lu, Y.H.; Lu, J.W.; Liao, Y.L.; Ren, T.; Li, X.K. Continuous potassium fertilization combined with straw return increased soil potassium availability and risk of potassium loss in rice-upland rotation systems. Chemosphere 2023, 344, 140390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Huan, W.; Song, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, J. Effects of straw incorporation and potassium fertilizer on crop yields, soil organic carbon, and active carbon in the rice–wheat system. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Gu, J.; Yang, J. Effects of long-term straw returning on rice yield and soil properties and bacterial community in a rice-wheat rotation system. Field Crops Res. 2023, 291, 108800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.J.; Tu, S.X.; Shah, F.; Xu, C.X.; Chen, J.R.; Han, D.; Liu, G.R.; Li, H.L.; Muhammad, I.; Cao, W.D. Substitution of fertilizer-N by green manure improves the sustainability of yield in double-rice cropping system in south China. Field Crops Res. 2016, 188, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Werf, W.V.D.; Makowski, D.; Lamichhane, J.R.; Zhang, F. Cover crops promote primary crop yield in China: A meta-regression of factors affecting yield gain. Field Crops Res. 2021, 271, 108237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Ling, N.; Feng, X.; Yang, X.; Wu, P.; Zou, J.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Soil fertility and its significance to crop productivity and sustainability in typical agroecosystem: A summary of long-term fertilizer experiments in China. Plant Soil 2014, 381, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Nie, J.; Cao, W.; Gao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liao, Y. Long-term green manuring to substitute partial chemical fertilizer simultaneously improving crop productivity and soil quality in a double-rice cropping system. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 142, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ren, T.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liao, S.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Rotation with oilseed rape as the winter crop enhances rice yield and improves soil indigenous nutrient supply. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 212, 105065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.B.; Novelli, L.E.; Sterren, M.A.; Uhrich, W.G.; Benintende, S.M.; Barbagelata, P.A. Long-term fertilizer application and cover crops improve soil quality and soybean yield in the Northeastern Pampas region of Argentina. Geoderma 2021, 385, 114902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Liang, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z. Impacts of future climate change on rice yield based on crop model simulation—A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingore, S.; Adolwa, I.S.; Njoroge, S.; Johnson, J.M.; Saito, K.; Philips, S.; Kihara, J.; Mutegi, J.; Murell, S.; Dutta, S.; et al. Novel insights into factors associated with yield response and nutrient use efficiency of maize and rice in sub-Saharan Africa. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Duan, Q.; Wu, C.; He, X.; Hu, M.; Li, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Peng, L.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Optimizing rice yield, quality and nutrient use efficiency through combined application of nitrogen and potassium. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1335744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; Lv, X.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, Z. Straw returning coupled with nitrogen fertilization increases canopy photosynthetic capacity, yield and nitrogen use efficiency in cotton. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 126, 126267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ren, T.; Cong, R.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Lu, J. Reduction of chemical phosphate fertilizer application in a rice–rapeseed cropping system through continuous straw return. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Cong, R.; Ren, T.; Li, X. Optimal potassium management strategy to enhance crop yield and soil potassium fertility under paddy-upland rotation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3404–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Sun, T.; Ma, T.; Chen, C.; Ma, Q.; Wu, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Q. Higher yield sustainability and soil quality by manure amendment than straw returning under a single-rice cropping system. Field Crops Res. 2023, 292, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, H.; Ning, T.; Li, Z.; Lar, R. Long-term effects of tillage and straw management on soil organic carbon, crop yield, and yield stability in a wheat-maize system. Field Crops Res. 2019, 233, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.W.; Li, W.W.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.F.; Xu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, G.H. Long-term straw incorporation increases rice yield stability under high fertilization level conditions in the rice-wheat system. Crop J. 2021, 9, 1191–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Wang, X.H.; Smith, P.; Fan, J.L.; Lu, Y.L.; Emmett, B.; Li, R.; Dorling, S.; Chen, H.Q.; Liu, S.G.; et al. Soil quality both increases crop production and improves resilience to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yang, N.; Lu, C.; Qin, X.; Siddique, H.M.K. Soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, available nutrients, and yield under different straw returning methods. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 204, 105171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasier, I.; Noellemeyer, E.; Figuerola, E.; Erijman, L.; Permingeat, H.; Quiroga, A. High quality residues from cover crops favor changes in microbial community and enhances C and N sequestration. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 6, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, C.; An, S.; Zhu, M.; Gao, Y.; Yu, W.; Ma, Q. Microbial nutrient limitations limit carbon sequestration but promote nitrogen and phosphorus cycling: A case study in an agroecosystem with long-term straw return. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Cong, R.; Ren, T.; Lu, Z.; Lu, J.; Li, X. Straw incorporation improved the adsorption of potassium by increasing the soil humic acid in macroaggregates. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, T.; Li, X.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Corrigendum to long-term straw return enhanced crop yield by improving ecosystem multifunctionality and soil quality under triple rotation system: An evidence from a 15 years study. Field Crops Res. 2024, 312, 109395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Abalos, D.; Arthur, E.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Chen, J. Different straw return methods have divergent effects on winter wheat yield, yield stability, and soil structural properties. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 238, 105992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Gerber, J.S.; Macdonald, G.K.; West, P.C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizumi, T.; Ramankutty, N. Changes in yield variability of major crops for 1981–2010 explained by climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 034003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Sun, W.; Huang, J.; Wen, H.; Huang, R. Excessive rainfall is the key meteorological limiting Factor for winter wheat yield in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Agronomy 2022, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseng, S.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; Rötter, R.P.; Lobell, D.B.; Cammarano, D.; Kimball, B.A.; Ottman, M.J.; Wall, G.W.; White, J.W.; et al. Rising temperatures reduce global wheat production. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 143−147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.