Abstract

Soil phosphorus (P) deficiency is an important factor limiting plant growth in the semi-arid Loess Plateau region in China. The topsoils in this area undergo repeated drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles, which can influence soil P availability, a process that may become more pronounced due to climate change. However, little is known about how soil P availability responds to DRW cycles under different land-use types. To investigate this issue, we conducted three 120-day soil culture experiments to investigate the direction and magnitude of soil available P and the responses of its influencing factors to repeated DRW cycles and their frequency and intensity under three typical land-use types (cropland, grassland, and shrubland) in Gansu Province, North-western China. The results showed that the available P concentration of cropland, grassland, and shrubland soils after repeated DRW cycles significantly decreased by 8.9%, 11.5%, and 14.2%, respectively, compared with a constant humidity control. With increasing intensity of the DRW cycles, the available P concentration of grassland and shrubland soils significantly increased by 14.3% and 15.5%, respectively, while in cropland soil P significantly decreased by 10.4%. Compared with low-frequency DRW cycles, high-frequency DRW cycles significantly reduced the available P concentration by 6.4% in grassland soil and increased it by 9.8% in shrubland soil but had no significant effect in cropland soil. Overall, the responses of soil P availability to repeated DRW cycles vary among different land-use types, and the magnitude of the soil P availability response to repeated DRW cycles depended strongly on soil microorganism biomass, phosphatase activity, and the initial soil properties, being more pronounced in grassland and shrubland soils than in cropland soils. It is therefore essential to consider land-use type when studying the effects of DRW on soil P cycling in semi-arid regions, especially in the context of climate change.

1. Introduction

The soils of the semi-arid Loess Plateau region of China are generally alkaline, rich in calcium carbonate, and have low phosphorus (P) availability, which is one of the main factors limiting the primary productivity of this ecosystem [1]. The limited availability of soil P has become an urgent issue that needs to be addressed in agricultural production and ecological restoration in this region. Soil water is an important factor affecting soil P cycling in arid areas [2,3,4]. Drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles are a common soil water fluctuation process; dry soils become moist due to discontinuous rainfall or irrigation and then dry out due to evaporation and transpiration. DRW cycles exert strong impacts on soil biogeochemical processes by changing the availability and accessibility of both the substrate [5,6] and the biomass and community structure of soil microorganisms [7,8], which can influence soil P transformation [3,9,10]. Moreover, due to the long-term droughts in this area, the soil physicochemical properties and microorganisms may be more sensitive to fluctuations in soil water, which may result in greater soil P transformation responses to DRW cycles in this area compared with other regions [4,11]. Therefore, studying the influence of DRW cycles and changing patterns of soil P availability in semi-arid areas is of great significance for regional soil P management and predicting the impact of future climate changes on ecosystem P cycling.

Changes in soil nutrient availability following a period of DRW cycles have been widely reported, particularly with regard to carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) but less so for P [2,3,12,13]. It is generally believed that DRW cycles can enhance the availability of soil P [3,9,14] through mechanisms like microbial cell lysis, releasing intracellular P [7,15,16], and the disruption of soil aggregates, freeing occluded P [17]. However, some studies have found that the amount of P released by dead soil microorganisms is limited [10,12,18] and largely depends on the composition of the soil microbial community [15]. Some studies have indicated that the quantity of P in the soil microbial biomass remains unchanged after repeated DRW cycles [7,9,19] and may even increase in certain circumstances [10,20]. Meanwhile, increases in the number of adsorption sites and the specific surface area of soil particles after the breakdown of soil aggregates during DRW cycles will also enhance the P adsorption capacity of a soil, thereby reducing P availability [20,21]. Since these opposite mechanisms could occur simultaneously, soil AP could be affected by the balance between them during repeated DRW cycles. Therefore, some studies have found that soil P availability does not change [22,23] or even decreases [20] after repeated DRW cycles. Overall, the effects of repeated DRW cycles on soil P availability remain poorly understood.

It has been shown that the differential impact of DRW cycles on soil P availability depends on soil properties such as organic matter, nutrient content, aggregation, and microorganism community composition, and that these properties regulate the sensitivity of physicochemical processes and microbes to DRW cycles [3,10,16,24]. For instance: the organic matter and aluminum/iron oxide contents of a soil have been shown to affect labile P transformation during soil DRW cycles [10,25]; nutrient leaching increased more after DRW cycles in soils with fungus-rich communities than in soils with fungus-poor communities [24]; the stability of soil aggregates largely determines the release and availability of substrate during DRW cycles [17]; the soil nutrient release response to DRW cycles is also regulated by soil microbial activity and community composition [15]; and the changes in soil microbial characteristics under DRW cycles are also regulated by soil nutritional status [26]. Land-use type is an important factor influencing soil properties. Each land-use type has its own characteristic soil physicochemical properties and microbial populations, which could influence the effects of DRW cycles on the direction and magnitude of P transformation. However, to date studies have usually only examined the effect of DRW cycles on soil P availability under a single land-use type, while the differences in soil P transformation responses to DRW cycles across various land-use types require further study.

Apart from soil properties, the pattern of DRW cycles, such as their frequency and intensity, also modulates the responses of soil P availability to repeated DRW cycles [3,18,23,27]. Climate models predict that many regions of the world can be expected to experience intensified rainfall alternating with longer drying periods in the near future, resulting in DRW cycles with increased frequency and/or intensity, especially in the Chinese semi-arid Loess Plateau region [11,28]. The intensity and frequency of DRW cycles could impact soil physical and chemical processes as well as microbial activity and community composition, thereby affecting the mineralization and immobilization of soil P [3,17]. Studies have shown that increasing the frequency of DRW cycles leads to a decrease in soil respiration, microbial biomass C, and the relative abundance of fungi [8,23]. Frequent DRW cycles can also stimulate the breakdown of soil aggregates, thereby increasing the availability of substrate [17,23]. Moreover, changes in the intensity of DRW cycles affect the movement of extracellular enzymes and the availability of substrate, altering microbial activity and community composition, which may influence nutrient transformation [11,18]. Overall, the responses of soil P availability to altered DRW patterns due to climate change under different land-use types are likely to become more complex. However, the effects of the frequency and intensity of DRW cycles on soil P availability under different land-use types have rarely been investigated.

The semi-arid Loess Plateau region is a typical ecologically fragile area in China and has been deeply affected by climate change and human activities. In recent decades, attempts have been made to improve this sensitive ecological environment, including vegetation restoration projects such as the “Grain for Green” project, and the region has become one of China’s most obvious areas of land use change, with large areas of cropland being transformed into grassland and shrubland. The surface soils of different land-use types in this region are exposed to repeated DRW cycles. Soil physicochemical properties and microorganisms exhibited significant changes after land-use conversion [29,30], which may lead to different soil P availability responses to DRW cycles in the different land-use types [3]. This will have a profound impact on soil P supply potential, plant growth, and the ecosystem P cycle. These impacts may become more prominent and complex as a result of global warming and future changes in precipitation patterns. However, little is known about how soil P availability responds to DRW cycles under different land-use types. In the current study, we experimentally analyzed the responses of soil P availability to DRW cycles and their intensity and frequency in Loess Plateau soils sampled from three typical land-use types (cropland, grassland, and shrub). Our objectives were to: (1) investigate the dynamics of soil AP in response to repeated DRW cycles, and whether this effect changes with the intensity and frequency of DRW cycles; (2) compare the response differences between different land-use types; and (3) identify the main factors affecting the differential changes in soil AP among different land-use types in response to repeated DRW cycles.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil Preparation

The soils used in this experiment were obtained from the Gansu Dryland Agro-Ecosystem Observation and Research Station of Lanzhou University (36°02′ N, 104°25′ E), in the Western Loess Plateau, China. This region has a typical medium temperate semiarid climate, with a mean annual air temperature of 6.5 °C and mean annual precipitation of 320 mm (about 60% of which occurs between June and September). The mean annual free water evaporation (1300 mm) in the region was four times that of the total precipitation, so that the soils experienced repeated DRW cycles, especially from June to September. The soil type is classified as Heima (Calcic Kastanozem) with a calcium carbonate content of 11–23%. The soil textural analysis (mean ± standard deviation, SD) consists of 25 ± 4% sand, 63 ± 3% silt and 12 ± 4% clay. The detailed properties of the soils tested are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Soil properties in the surface layer (0–20 cm) under different land-use types (mean ± standard deviation).

Soils from the three land-use types (cropland, grassland, and shrubland) were collected at the end of May 2023. The cropland had been under a rotation system, with crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), maize (Zea mays L.), and potato (Solanum tuberosum L.), following local farming management practices. The grassland had developed naturally after farmland abandonment, with Leymus secalinus (Georgi) Tzvelev, Poa annua L., and Aster altaicus Willd as the dominant plant species. The shrubland had been artificially planted with Caragana korshinskii. The selected sampling sites on the three land-use types shared similar elevation, slope, and aspect values, and had all been in their current form for over 30 years. The maximum distance between any two land-use types did not exceed 1000 m. Three representative sampling plots (10 × 10 m) were established at random in each land-use type, with a distance of more than 15 m between replicate plots. After removing the surface litter, topsoil (0–20 cm) samples were taken at random from ten points in each plot using a soil auger (20 cm depth, 5 cm diameter) and bulked to form a composite soil sample, and brought back to the laboratory. After passing through a 2 mm soil sieve, each fresh sample was divided into two parts: one was used to determine the basic soil properties (Table 1), and the other was stored at 4 °C for the different DRW cycle experiments.

Before beginning the DRW cycles, each subsample of soil (equivalent to 100 g oven-dried soil) was weighed into a 500 mL glass jar and then pre-incubated at 18 °C (the average temperature from June to September) at 60% of its water holding capacity (WHC) for one week to reduce the impact of disturbances caused by collection and sieving.

2.2. Experimental Design

Three experiments were set up to investigate the effects of DRW cycles and their intensity and frequency on the availability of soil P under the three different land-use types. The two-factor replicated randomized block design was used for each individual experiment. The specific design for each experiment is described below.

Experiment 1 (repeated DRW cycles). This experiment involved two treatments: (1) constant moisture (CM; soil moisture was kept constant at 60% WHC), and (2) DRW cycles in which soil samples were subjected to repeated drying and rewetting. According to the past 30 years’ meteorological data, the DRW cycles in this area mainly occurred from June to September, with an average of ten cycles per year. Therefore, the experiment was performed over a 120-day period, during which the DRW treatment was carried out for ten cycles in total. Each DRW cycle began with 11 days of soil drying, followed by rapid rewetting to 60% WHC, after which the soil was kept moist for one day. The soils were then slowly dried by removing the jar lid and allowing them to evaporate freely. Soil rewetting was achieved by slowly and uniformly adding sterile deionized water to the soil surface using a dropper until the soil moisture reached 60% WHC. Each treatment was independently administered three times. All the soils were incubated in a dark climate chamber at 18 °C for the course of the experiment. The soil samples were weighed daily to ensure that the soil moisture remained within the preset range.

Experiment 2 (DRW intensity). Different levels of precipitation will lead to different degrees of rewetting of dry soil, causing different DRW intensities. Our previous observations showed that the topsoil moisture in this area was approximately 50–100% WHC after different amounts of precipitation under natural conditions. Therefore, the DRW intensity levels established in this experiment were: low intensity (soil rewetted to 100% WHC) and high intensity (soil rewetted to 50% WHC), with three replicates for each treatment. The intensity in this experiment simulated the different degrees of rewetting of the dry soil caused by different amounts of precipitation under natural conditions. Each DRW cycle started with an 11-day drying period, followed by rewetting to either 100% WHC or 50% WHC for the low- and high-intensity treatments, respectively, followed by moist incubation for one day. The methods for simulating the soil DRW cycles were the same as for Experiment 1.

Experiment 3 (DRW frequency). Changes in the duration of precipitation intervals can lead to different frequencies of alternating dry and wet soil conditions. Our previous observations showed that the interval between two consecutive precipitation events in this area, between June and September in the past 30 years, was 8–24 days. Therefore, two levels of DRW frequency were established in this experiment: low frequency (24 days per cycle; with rewetting events separated by 23-day dry periods) and high frequency (eight days per cycle; with rewetting events separated by seven-day dry periods), with three independent replicates for each treatment. DRW cycles with high and low frequencies comprised 15 and five cycles during the entire culture period (120 days), respectively. Each DRW cycle for the high- and low-frequency treatments began with a drying period of seven and 23 days, respectively, after which both were rewetted to 60% WHC and kept moist for one day. The methods for simulating the soil DRW cycles were also the same as for Experiment 1.

2.3. Measurements

Soil samples were collected after the 120-day test period. Each sample was divided into two subsamples: one was used immediately to determine the soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC), inorganic N (IN), alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP), and the microbial biomass C (MBC) and P (MBP), and the other subsamples was dried naturally to measure the soil available P (AP), to characterize the availability of soil P. Soil DOC was determined using a total organic carbon analyzer (Multi N/C 3100, Analytik Jena, Jena, Germany) after extraction with 0.5 mol L−1 K2SO4. Soil IN was determined using an auto-flow injection analyzer (Skala, Breda, The Netherlands) after extraction with 2 mol L−1 KCl. Soil ALP activity was determined using the p-nitrobenzene phosphate method [31]. Soil AP was determined using the Olsen-P method [32]. Soil MBC and MBP were measured using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method with efficiency constants of 0.45 and 0.40 [33], respectively.

2.4. Calculations and Statistics

The effect size of soil AP in response to the DRW cycles, at different intensity or frequency (Etreatment) under each land-use type was calculated using the following equation:

where APtreatment is the soil AP under the DRW cycle, or the high intensity, or high frequency treatment (mg kg−1), and APck is the soil AP under CM, or the low intensity, or low frequency treatment (mg kg−1).

Two-way analysis of variance was used to analyze the effects of the DRW cycles, or their intensity or frequency, and land-use types on soil AP, MBC, MBP, ALP, DOC, and IN. Independent sample Student’s t-tests were used to examine the effects of the DRW cycles, or its intensity or frequency on soil AP, MBC, MBP, ALP, DOC, and IN under each land-use type. The effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles, or its intensity or frequency among different land-use types, was evaluated using one-way analysis of variance. The correlations between the changes in soil AP and the changes in soil MBC, MBP, ALP, DOC, and IN following DRW cycles, and their intensity and frequency, were performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Regression analyses were conducted for initial soil properties and the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles, and their intensity and frequency. All figures were drawn using Origin Pro 2021 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

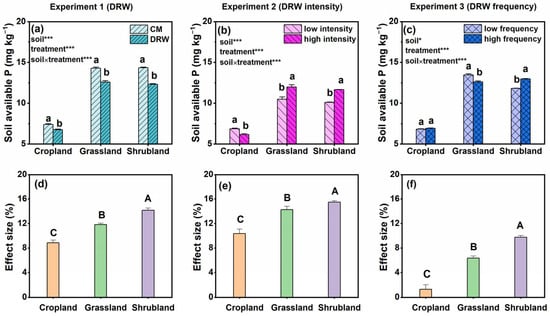

3.1. Soil AP

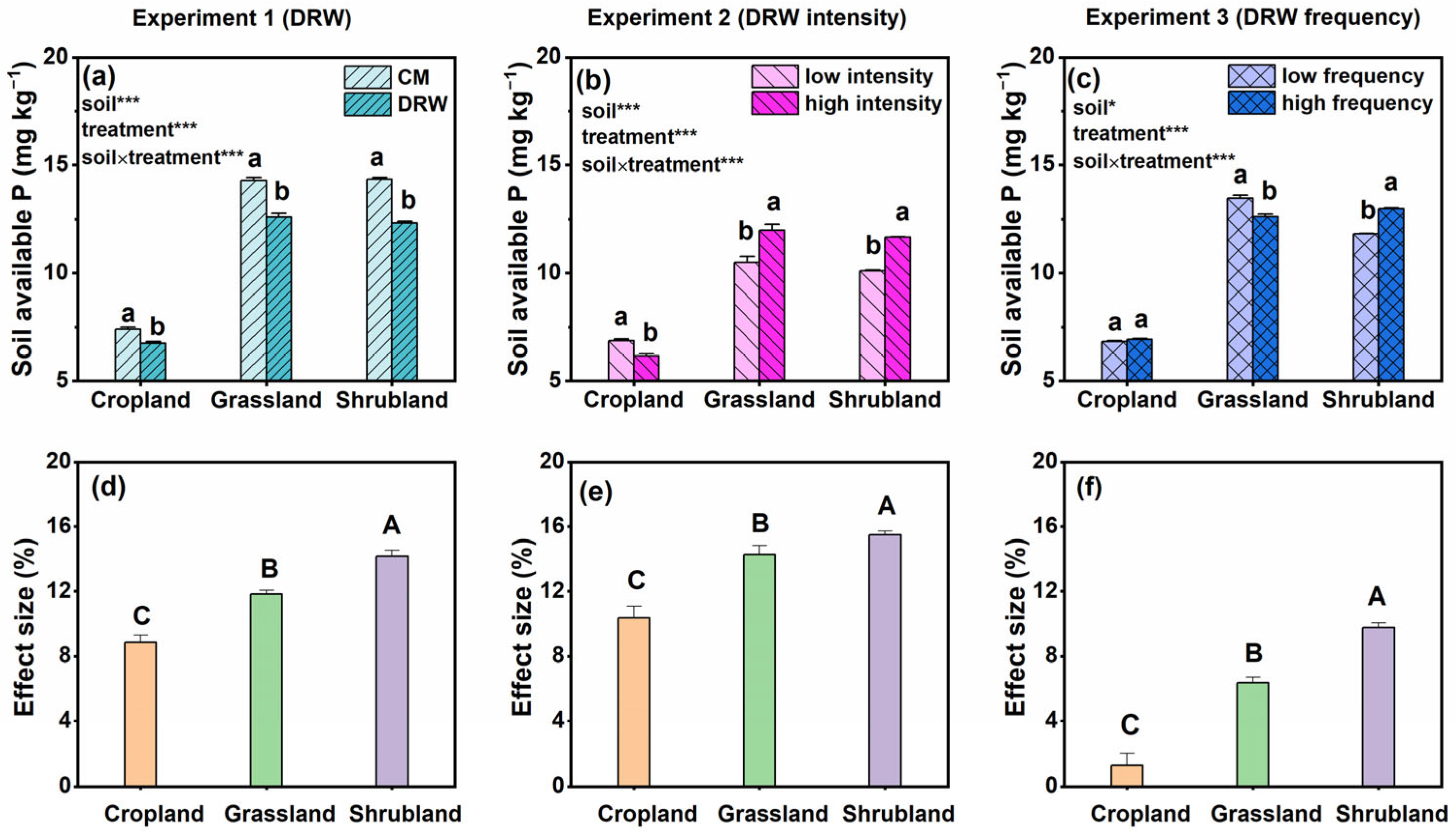

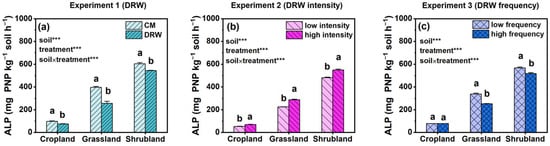

In all of the experiments, the AP concentrations in the grassland and shrubland soils were higher than those in the cropland soil. The DRW cycles caused a significant decrease in the AP concentration of all samples, this effect being most pronounced in the shrubland soil (Figure 1a). Compared with the CM treatment, the AP concentration of cropland, grassland, and shrubland soils after repeated DRW cycles decreased by 8.9%, 11.5%, and 14.2%, respectively (Figure 1a,d). With increasing intensity of DRW cycles, the AP concentration of grassland and shrubland soils significantly increased by 14.3% and 15.5%, respectively, while that in cropland soil significantly decreased by 10.4% (Figure 1b,e). Compared with the low-frequency DRW cycles, the high-frequency DRW cycles significantly reduced the AP concentration by 6.4% in grassland soil and increased it by 9.8% in shrubland soil but had no significant effect on it in cropland soil (Figure 1c,f). The order of the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycle intensity and frequency under the three land-use types was: shrubland > grassland > cropland (Figure 1e,f).

Figure 1.

The effects (a–c) and effect size (d–f) of repeated drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles and their intensity and frequency on soil available P concentration under the different land-use types. The different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the treatments in the same land-use type based on the independent sample t-test (p ≤ 0.05). The different uppercase letters indicate a significant difference among the land-use types based on the one-way analysis of variance (p ≤ 0.05). ***, p ≤ 0.001; *, p ≤ 0.05.

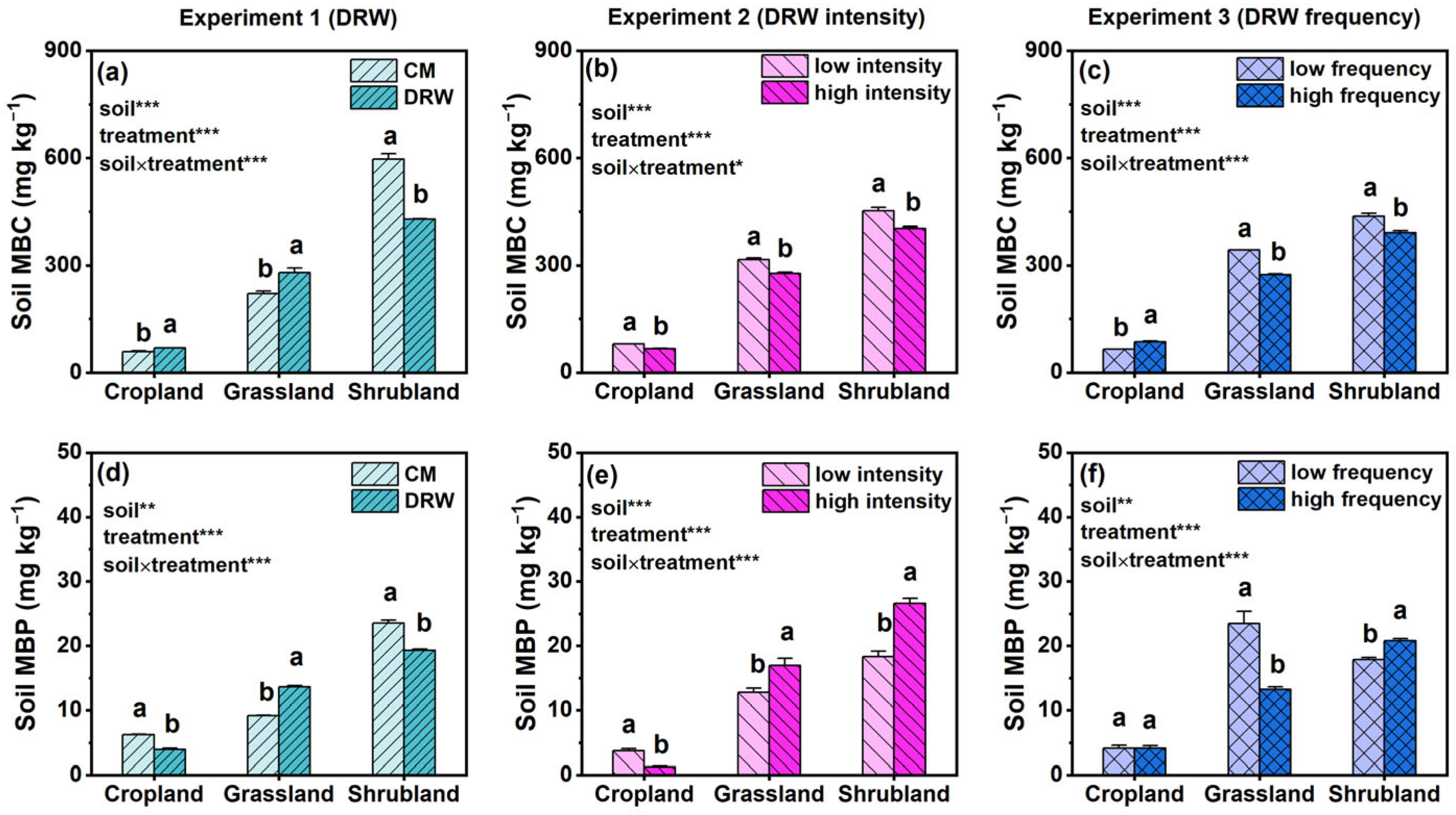

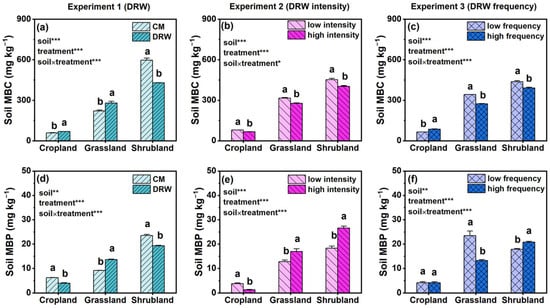

3.2. Soil Microbial Biomass

Both the different DRW cycles and land-use type significantly affected the amounts of soil MBC and MBP. The concentrations of MBC and MBP were lowest in cropland soil and highest in shrubland soil (Figure 2a). Compared with the CM treatment, repeated DRW cycles significantly increased the concentration of MBC in cropland and grassland soils but decreased it in shrubland soil (Figure 2b). High-intensity DRW cycles caused a significant decrease in the MBC concentration of all soils. Soil MBC concentration increased with increasing DRW frequency in cropland soil but decreased in grassland and shrubland soils (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Effects of repeated drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles and their intensity and frequency on (a–c) soil microbial biomass C (MBC) and (d–f) microbial biomass P (MBP) under different land-use types. The different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the treatments in the same land-use type based on the independent sample t-test (p ≤ 0.05). ***, p ≤ 0.001; **, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.05.

The MBP concentration after repeated DRW cycles increased by 48.4% in grassland soil but decreased by 37.4% in cropland soil and 17.8% shrubland soil (Figure 2d). With increasing DRW cycle intensity, the MBP concentration of grassland and shrubland soils increased significantly by 32.9% and 45.4%, respectively, while in cropland soil it decreased significantly by 66.7% (Figure 2e). Frequent DRW cycles significantly decreased the AP concentration by 43.6% in grassland soil but decreased it by 16.8% in shrubland soil, having no significant effect on it in cropland soil (Figure 2f).

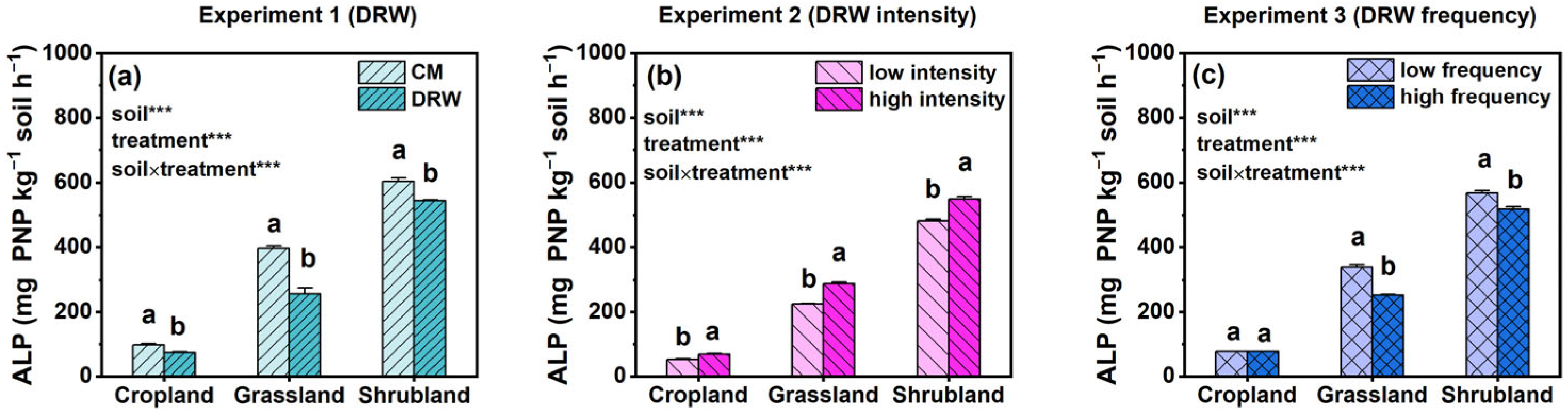

3.3. Soil ALP

Shrubland soil had higher ALP activity than the other soils in all experiments (Figure 3). ALP activity significantly decreased by 23.9% in cropland soil, by 35.3% in grassland soil, and by 10.0% in shrubland soil after repeated DRW cycles, compared with the CM treatment (Figure 3a). Intense DRW cycles significantly increased ALP activity by 34.8%, 27.5%, and 14.1% in cropland, grassland, and shrubland soils, respectively (Figure 3b). Compared with the low-frequency DRW cycles, high-frequency DRW cycles significantly reduced ALP activity by 25.3% in grassland soil and by 8.9% in shrubland soil but had no significant effect on it in cropland soil (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Effects of (a) repeated drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles and their (b) intensity and (c) frequency on soil alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity under different land-use types. The different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the treatments in the same land-use type based on the independent sample t-test (p ≤ 0.05). ***, p ≤ 0.001.

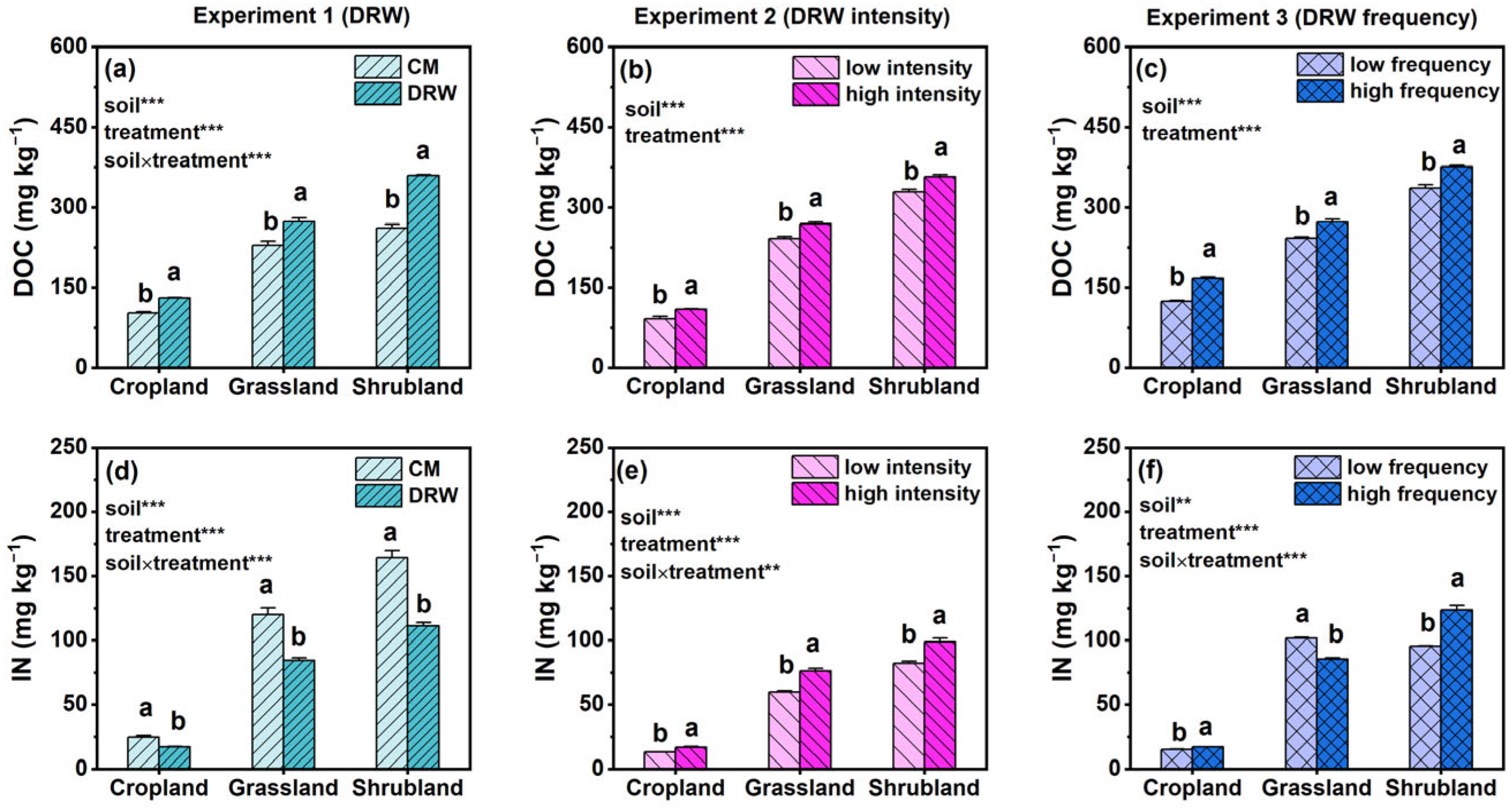

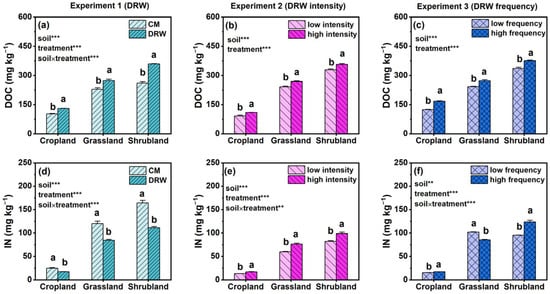

3.4. Soil Dissolved Organic C and Inorganic N

Compared with the CM treatment, the DOC concentration of cropland, grassland, and shrubland soils increased significantly after repeated DRW cycles, while the IN concentration decreased significantly (Figure 4a,d). With increasing DRW cycle intensity, the soil DOC and IN concentrations in soils of the three land-use types increased significantly (Figure 4b,e). Compared with the low-frequency DRW cycles, high-frequency DRW cycles significantly increased the DOC and IN concentrations in cropland and shrubland soils. The DOC concentration of grassland soil significantly increased after frequent DRW cycles, while soil IN concentration decreased (Figure 4c,f).

Figure 4.

Effects of repeated drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles and their intensity and frequency on (a–c) soil dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and (d–f) soil inorganic N (IN) under different land-use types. The different lowercase letters indicate a significant difference among the treatments in the same land-use type based on the independent sample t-test (p ≤ 0.05). ***, p ≤ 0.001; **, p ≤ 0.01.

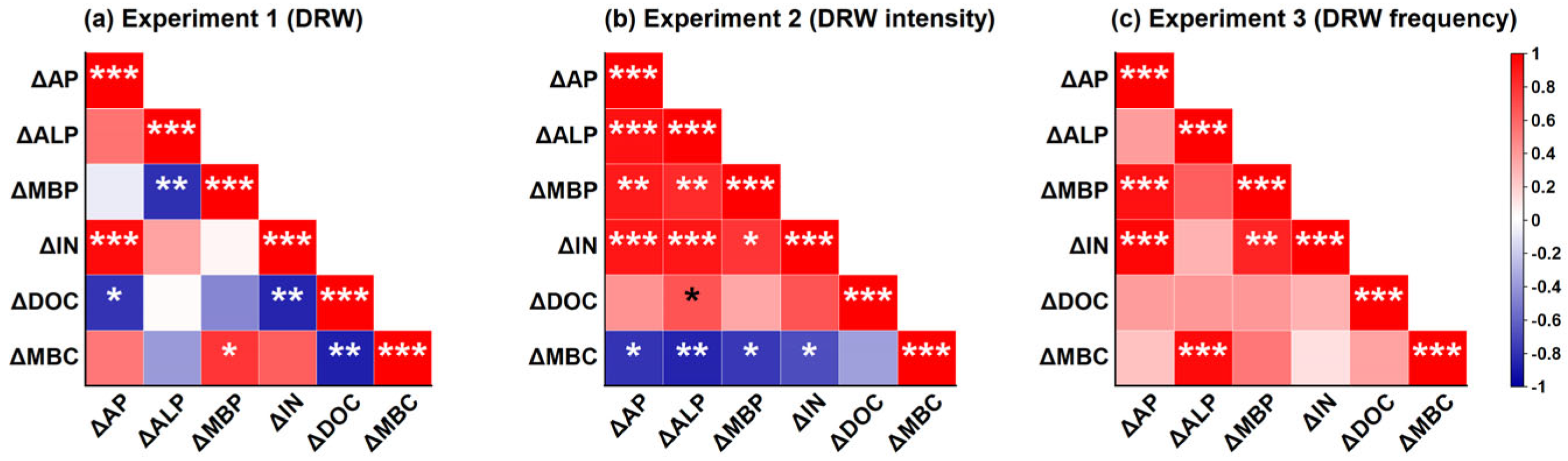

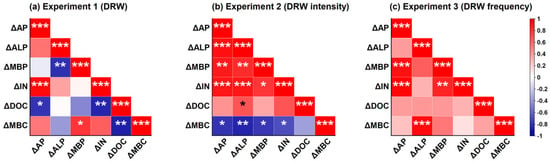

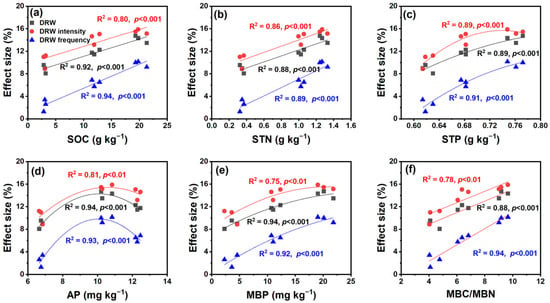

3.5. Correlations Between Soil AP and Soil Properties

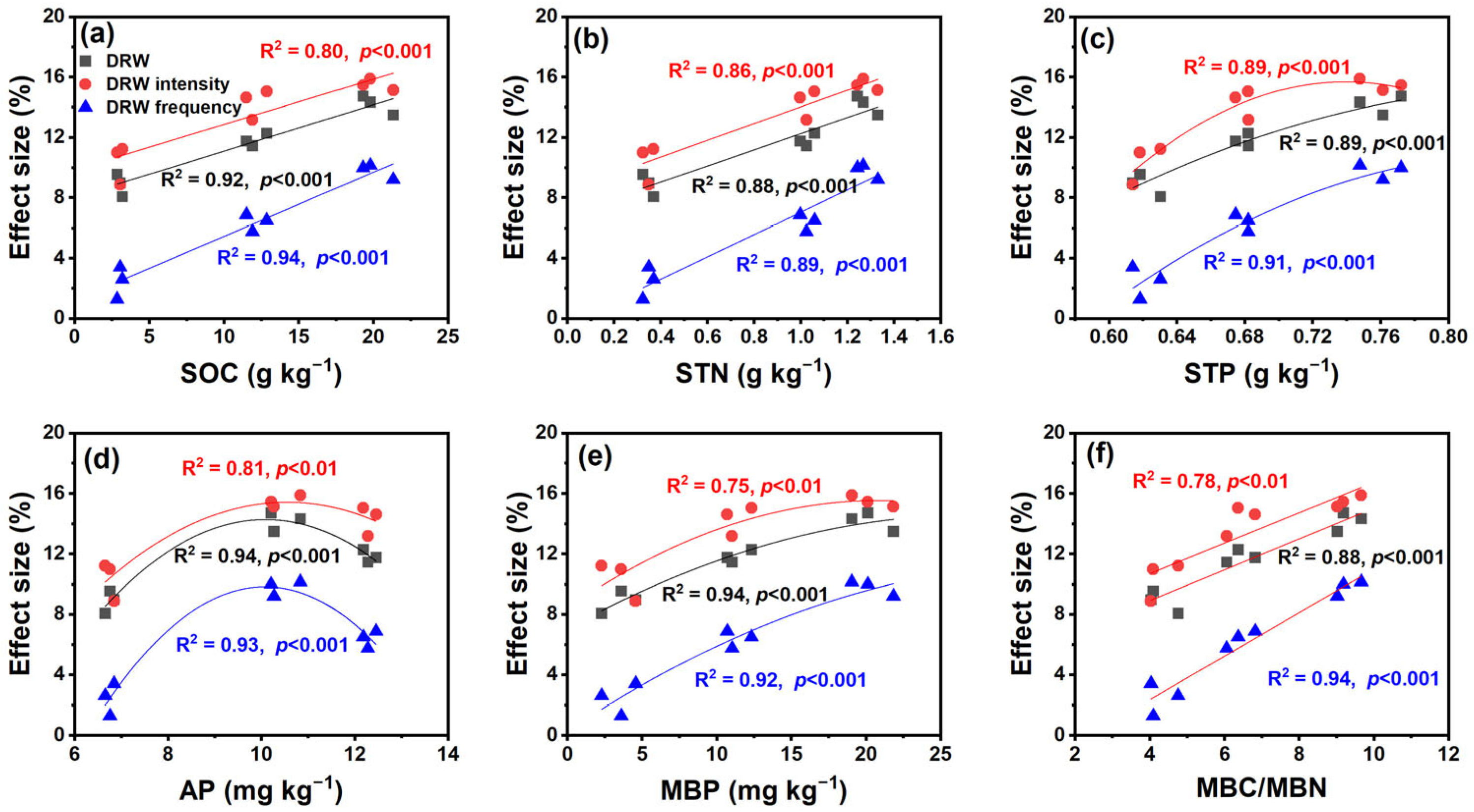

After repeated DRW cycles, the change in soil AP (ΔAP) concentration was positively correlated with the change in soil IN (ΔIN) concentration and negatively correlated with the change in soil DOC (ΔDOC) concentration, but it was not related to the changes in ALP (ΔALP), MBP (ΔMBP), or MBC (ΔMBC) (Figure 5a). In response to the increase in DRW cycle intensity, ΔAP was significantly positively correlated with the changes in ΔALP, ΔMBP, and ΔIN, and negatively correlated with the change in ΔMBC but was not related to the changes in ΔDOC (Figure 5b). After the increase in DRW cycle frequency, the changes in ΔAP were significantly positively correlated with the changes in ΔMBP or ΔIN but not with the changes in other soil properties (Figure 5c). Regression analysis showed that the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles and their intensity and frequency increased with the concentrations of SOC, TN, and the microbial biomass C/N of the initial soil, at first increasing and then decreasing with increasing TP, AP, and MBP concentrations in the initial soil (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Correlations between the changes in soil available phosphorus and changes in soil properties following (a) drying–rewetting (DRW), and its (b) intensity and (c) frequency are performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Δ represents changes in soil available phosphorus and other soil properties in response to DRW and its intensity and frequency. AP, available phosphorus; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; MBP, microbial biomass phosphorus; IN, inorganic nitrogen; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; and MBC, microbial biomass carbon. ***, p ≤ 0.001; **, p ≤ 0.01; *, p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 6.

Relationships between the initial (a) soil organic carbon (SOC), (b) total nitrogen (TN), (c) total P (TP), (d) available phosphorus (AP), (e) microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP), and (f) microbial biomass C/N (MBC/MBN) and the effect size of soil AP to various drying–rewetting (DRW) cycles and their intensity and frequency.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Influence of Repeated DRW Cycles on Soil P Availability Under Different Land-Use Types (Experiment 1)

This study found that repeated DRW cycles significantly reduced soil P availability in the semi-arid Loess Plateau region. This finding differs from the results of most previous studies, which suggested that DRW cycles could improve soil P availability by killing soil microorganisms and disrupting soil aggregate structure [7,12,13,16,34]. This difference between the current study and earlier ones could be due to many factors, such as the pattern and duration of the DRW cycles or the soil type [3]. First, soils in different regions experience different patterns of DRW cycles. Unlike other studies, the present study focused on semi-arid areas, where the average drying period during a DRW cycle under natural conditions (11 days) was much longer than that in other studies (3–7 days) [10,13,18,34]. The extension of the drying period will weaken the effect size of DRW cycles on soil aggregates and microorganisms [35,36]. Meanwhile, soil microorganisms in arid regions may be adapted to long-term drought stress and repeated DRW cycles [4,37], which may also weaken the soil microbial biomass and community structure responses to repeated DRW cycles, thus affecting the transformation of P.

Second, the total duration and number of repeated DRW cycles are also important factors determining the release of P [10,12,27]. Previous studies had suggested that the P released by soil microorganisms and aggregates may be limited after repeated DRW cycles due to the weakened effect of DRW cycles on soil microorganisms and aggregates as the number of cycles increases [10,35,36]. Chen et al. [27] reported that DRW cycles increased soil AP concentration by between 10% and 18% during the first two cycles, but these increases were only temporary as soil AP quickly decreased to the same level as the constant wet control as the DRW duration and number of DRW cycles increased. Unlike other studies (1–3 cycles, of less than 60 days duration) [12,13,16,18], this study conducted a 120-day experiment with 10 cycles to simulate natural conditions as far as possible. Increasing the number of cycles or their duration may reduce the release of soil P after repeated DRW cycles [10,27].

Third, ALP activity is an important factor affecting P transformation and can promote the mineralization of soil organic P [38]. In the present study, although the soil DOC concentration (substrate) increased significantly after repeated DRW cycles under all land-use types, ALP activity decreased significantly, indicating that the mineralization of organic P was limited, which ultimately affected the availability of soil P. A recent study confirmed that DRW cycles promoted the conversion of labile inorganic P to organic P, driving the transformation of available P to moderately available P [39]. This may be due to the reduction in soil N availability (soil IN) following repeated DRW cycles, because the phosphatase secreted by soil microorganisms requires N. This relationship was confirmed by a significant positive correlation between the change in soil IN concentration and the change in AP concentration after repeated DRW cycles (Figure 6).

Finally, the impact of DRW cycles on soil nutrient cycling was largely related to soil type [3,5,40]. The test soils from the semi-arid of the Loess Plateau region were calcareous with high free calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate concentrations, compounds which fix strongly to soluble P [1,4]. Therefore, the soluble P released by soil microorganisms and aggregates after repeated DRW cycles could be readily fixed by soil calcium and magnesium ions, resulting in a decrease in P availability. As a previous study had reported that the concentrations of Ca2-P, Al-P and Fe-P in calcareous soil significantly decreased, while the concentrations of Ca8-P and O-P increased during DRW cycles [41].

Many studies have suggested that the release of P from microbial biomass is the main cause of soil P increases after DRW cycles [7,13]. Studies have shown that DRW cycles can kill more than two-thirds of the microorganisms in some soils [2,42], and that the decrease in soil MBP was positively correlated with the increase in total soluble P after the DRW cycles [13,43]. However, in our study, although DRW cycles significantly reduced the MBP concentration of cropland and shrubland soils, they did not increase their AP concentration. This could be due to one of two factors. On one hand, the changes in soil aggregate structure in cropland and shrubland during DRW cycles may expose and increase the non-specific adsorption sites of electrostatic attraction and specific adsorption sites of ligand adsorption, resulting in more of the soluble P released from dead microorganisms being adsorbed on the soil surface [23]. On the other hand, the MBC concentrations in cropland and shrubland soils significantly increased and decreased, respectively, after DRW cycles, suggesting changes in the structure of their soil microbial communities. Changes in the soil microbial community structure may affect the P cycling process, such as the mineralization of organic P and the dissolution of inorganic P, thereby altering the availability of soil P [44]. Furthermore, our results indicated that soil MBP was not the main factor affecting P availability in cropland and shrubland soils during DRW cycles. Other research teams have made similar findings [7,9,12,18]. Unlike cropland and shrubland soils, the MBP concentration of grassland soil increased significantly after repeated DRW cycles, contrary to the change in soil AP. Moreover, the increase in soil MBP (4.43 mg kg−1) was significantly greater than the decrease in soil AP (1.69 mg kg−1). This indicated that the reduction in soil AP after repeated DRW cycles was probably mainly due to the sequestration of P by microbial organisms, suggesting that DRW cycles promote the growth and reproduction of microorganisms in grassland soil, especially P-containing microorganisms. The significant increase in MBC concentration in grassland soil after repeated DRW cycles confirmed this, to some extent.

4.2. The Influence of the Intensity of DRW Cycles on Soil P Availability Under Different Land-Use Types (Experiment 2)

According to global climate trends, increases in intensified rainfall frequency and drought intensity in the future will lead to increases in the intensity of DRW cycles [11,17], which may have an impact on the transformation and availability of soil P. In general, increasing intensity of DRW cycles would aggravate soil water changes, which could result in increasing lysis of living microbial cells, increasing the release of intracellular osmoregulatory organic solutes, and the exposure of previously protected organic matter in soil aggregates and colloids [9,11,17,36]. High-intensity DRW cycles caused a significant decrease in MBC concentration and increase in DOC and IN concentrations in all of the soils tested, in agreement with many previous studies [45,46]. The increase in DOC and IN concentrations promoted soil microbial activity and increased phosphatase secretion [9,44]. Therefore, there was a significant positive correlation between the changes in soil DOC and IN concentrations and ALP activity after intense DRW cycles. In addition, intense DRW cycles significantly increased ALP activity in all of the soils. Moreover, the decrease in soil MBC concentration suggested that the structure of the soil microbial community may have changed. Therefore, the increase in soil ALP activity under high-intensity DRW cycles may also be related to the increase in the abundance of related microorganisms in soil microbial communities. For example, the abundance of soil Pseudomonas spp. with phosphate-solubilizing effect will increase significantly after DRW cycles [18,19].

Increases in soil ALP activity can promote the mineralization of organic P, thereby improving the availability of soil P [44]. Therefore, intense DRW cycles could significantly enhance P availability in grassland and shrubland soils even when the amount of P fixed by soil microorganisms increases (i.e., MBP increases). Interestingly, unlike grassland and shrubland soils, the MBP concentration of cropland soil decreased significantly after high-intensity DRW cycles. This might be related to the different soil microbial community structures in the various land-use types, because soils with different microbial community compositions have different responses to DRW cycles [7,15,24]. Ouyang et al. [8] found that the soil microbial biomass and community composition responses to repeated DRW cycles differed in diverse arid and semi-arid ecosystems. In general, decreases in soil MBP and increases in ALP activity are both beneficial to the increase in soil P availability during DRW cycles [9]. However, in our study, the MBP concentration and ALP activity in cropland soil decreased and increased, respectively, with increasing DRW cycle intensity, while the soil AP concentration decreased. This may be because cropland soil has poor aggregate stability due to low organic matter content and frequent tillage, making it more sensitive to the intensity of DRW cycles. When the intensity increased, the degree of damage to soil aggregates increased [17,36], more calcium ions were released, and more adsorption sites were exposed, resulting in more P released from microbial mineralization and dead microorganisms being adsorbed onto the soil particle surfaces.

4.3. The Influence of the Frequency of DRW Cycles on Soil P Availability Under Different Land-Use Types (Experiment 3)

DRW events are expected to occur at higher frequencies in the near future due to the expected increasing frequency of extreme precipitation events [9]. The higher the DRW frequency, the more frequent the rewetting process, and the stronger the damage to soil microorganisms and aggregates [23,27,47]. The stability of soil aggregates decreases with the increasing frequency of DRW cycles [23], so that frequent DRW cycles may significantly decrease microbial biomass [8]. In our study, we found that the response of soil P availability to frequent DRW cycles varied among the different land-use types. In cropland soil, the frequency of DRW cycles had no significant effect on soil AP. This is because soil microorganisms were not killed by frequent DRW cycles, and P in the microbial cells was not released, because frequent DRW cycles had no significant effect on the MBP concentration. On the other hand, compared with low-frequency DRW cycles, high-frequency DRW cycles significantly increased soil DOC and IN contents, providing more substrate and nutrients for microorganisms. In addition, the MBC content increased, and ALP activity was unaffected, thus failing to promote organic P mineralization. This may be because frequent DRW cycles push the soil microbial community towards those microorganisms related to C and/or N cycling, rather than P cycling.

In grassland soil, although high-frequency DRW cycles killed a large number of microorganisms and significantly reduced the MBP concentration, they did not improve soil P availability. This may be because the change in grassland soil aggregate structure under high-frequency DRW cycles increased P adsorption sites, leading to the release of soluble P from dead microorganisms adsorbed onto the soil particle surface or encapsulated by aggregates. In addition, the decrease in soil ALP activity was also an important reason for the decrease in grassland soil P availability after frequent DRW cycles. Unlike grassland soil, although high-frequency DRW cycles increased MBP content and reduced ALP activity in shrubland soil, it did not reduce soil P availability, but rather increased AP concentration. This indicated that the source of the AP pulse in shrubland soil after frequent DRW cycles may be primarily non-microbial in origin; a large amount of active P would be released after a reduction in soil adsorption properties, releasing soluble P from broken soil aggregates and enhancing the activation of P by microorganisms as the soil microbial community structure changed. This finding was consistent with those from other studies that have shown that increases in AP were due to increased organic P solubility and released adsorbed P rather than release of P from microbial biomass [18,42]. These points require confirmation by future studies, especially the speculations regarding soil aggregates and microbial community structure.

4.4. The Effect Size of Soil AP to DRW Cycles Under Different Land-Use Types

DRW has been reported to significantly influence soil P availability, but this effect is dependent on soil properties and thus differs between soils [3,10,34,43]. We also found that the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles under different land-use types varied greatly among the different land-use types: compared with cropland, soil P availability under grassland and shrubland was more sensitive to DRW cycles and their intensity and frequency. We also found a significant positive relationship between soil SOC and TN and the effect size of DRW cycles on soil AP. This result supports previous findings that the effect of DRW cycles on P transformation was more pronounced in soils with a higher organic matter concentration than in those with lower organic matter concentrations [10,25]. This is because DRW cycles affect the release and availability of soil P mainly by changing the soil aggregate distribution, substrate accessibility, and microbial cell lysis, while soils with high organic matter content generally have good aggregate structure, more substrates, and larger microbial biomass, making them more susceptible to DRW cycles.

The soil P concentration itself was also an important factor affecting the effect size of DRW cycles on soil AP. Generally, the higher the total P and AP concentrations of a soil, the higher the concentration of dissolved P, microbial biomass P, adsorbed P, and active organic P in the soil, all of which were highly sensitive to DRW cycles, and the greater the response to DRW cycles [9,48]. However, due to the limited impact of DRW cycles on the availability of soil P—the effect did not exceed 20% in any of the soils in this study—the soil itself also needs to maintain its elemental balance [4]. When the total P and AP concentration of the soil exceeds a certain range, the changes in those P components, which are sensitive to DRW cycles, may be restricted by other factors, and their impact on P availability may also be limited. Therefore, the relationship between the initial soil TP and AP concentration and the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles showed a quadratic parabolic trend.

Microorganisms are the most active component of a soil, and their biomass is known to significantly affect the availability of P during DRW cycles [9]. Numerous studies have suggested that MBP is probably the main source of P release after DRW cycles [2,13,16]; the contribution ratio of MBP varied greatly between the different soils tested [42]. For example, in some soils with relatively low MBP concentration, the contribution of MBP to AP under DRW cycles is actually very small [12]. So, in our study, the response effects of soil AP to DRW cycles were observed to be higher in shrubland soil with its high MBP than in cropland soil with its low MBP. Moreover, the effect size of the DRW cycles on P release from microbial biomass depended largely on the microbial community composition. Soil MBC/MBN is an important indicator of microbial community composition, and the higher the MBC/MBN, the lower the ratio of bacteria to fungi [49]. We found that soil MBC/MBN was positively correlated with the effect size of soil AP to DRW cycles. This may be due to fungi having relatively thick, rigid cell walls and producing compatible solutes, which are considered to be more resistant to repeated DRW cycles than those of bacteria [15,50]. Many studies have also confirmed that repeated DRW cycles might reduce the ratio of bacteria to fungi and change the composition of microbial community [8,11,17,19]. This suggests that soil microbial community structure differences may be an important reason for the different responses of soil P availability to repeated DRW cycles under different land-use types. Unfortunately, in this study, we only measured changes in microbial biomass but did not measure the changes in the soil microbial communities. Future work on DRW cycles should utilize methods such as high-resolution sequencing or phospholipid fatty acid analysis to study the changes in soil microbial communities more deeply to reveal the underlying mechanisms. And, as the habitat of microorganisms, soil aggregates are also an important factor affecting soil P fractions transformation during DRW cycles [2,35]. Therefore, future studies need to pay more attention to the changes in soil aggregates and the P fractions at the aggregate level.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that caution must be exercised when extrapolating the changes in soil AP observed in our laboratory DRW study to natural conditions. This is because laboratory incubations are conducted under controlled environment conditions (e.g., no plants, fixed temperature, controlled drying cycles) to reduce the confounding effects of other factors, to achieve mechanistic insight. However, under natural soil and climatic conditions, DRW cycles and their environmental background are highly variable. Laboratory experiments cannot fully replicate this natural temporal variability (such as fluctuating temperatures, microbial inputs, and root activity) and thus may not accurately represent the transformation of soil P in a complex ecosystem. Additionally, in calcareous soils, the AP measured by the Olsen method in this study may underestimate the actual availability of soil P due to the very rapid reaction of P with calcium. While the Olsen method is widely used for rapidly assessing how soil P availability responds to DRW cycles [18,20,23,25], it primarily targets the most readily bioavailable fractions—such as water-soluble inorganic P and Ca2-P—and thus fails to provide a holistic evaluation of overall soil P availability. In fact, potentially labile P pools in calcareous soils, including Ca8-P, Al-P, and Fe-P, can undergo rapid transformations to become plant-available. Therefore, to more comprehensively and accurately evaluate the dynamics in P availability in calcareous soils following DRW cycles, future studies should adopt techniques such as sequential extraction or 31P nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to distinguish P fractions based on their bioavailability to plants (e.g., labile P, moderately labile P, and non-labile P).

5. Conclusions

This study showed that the responses of soil P availability to repeated DRW cycles vary among different land-use types in the semi-arid Loess Plateau of China. First, the P availability in cropland, grassland, and shrubland soils after repeated DRW cycles decreased by 8.9%, 11.5%, and 14.2%, respectively. Second, under changing intensity and frequency of DRW cycles, intense DRW cycles significantly reduced the P availability by 10.4% in cropland soil, while P availability increased by 14.3% and 15.5% in grassland and shrubland soils, respectively, and frequent DRW cycles significantly reduced P availability by 6.4% in grassland soil and decreased it by 9.8% in shrubland soil but had no significant effect in cropland soil. Third, compared with cropland, the P availability in grassland and shrubland soils was more sensitive to DRW cycles and their intensity and frequency due to their higher organic matter and P concentrations of these soils, as well as their microbial biomass C/N ratio. These results suggest that the varied response patterns of different land-use types should be considered when evaluating large-scale P cycling in the context of repeated DRW cycles, along with the likely future rainfall pattern changes in semi-arid regions. The results of this study provide a theoretical basis for ecological restoration and sustainable P management in agriculture. Furthermore, the rapid P-calcium reactions in calcareous soils may have caused underestimation of soil P availability in this study. There is a need for future research into the effects of repeated DRW cycles on soil microbial communities and P fractions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.H.; software, Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, M.K. and Y.H.; data curation, M.K. and Y.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and Y.H.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project of Shanxi Province Key Lab Construction (Z135050009017-1-5), the Doctoral Scientific Research Start-up Foundation of Shanxi Agricultural University (2021BQ47), and the Self-research Program Project for Talent Support of Shanxi Organic Dryland Farming Research Institute, Shanxi Agricultural University (yrczy202501).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kong, M.; Kang, J.; Han, C.L.; Gu, Y.J.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Li, F.M. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium resorption responses of alfalfa to increasing soil water and P availability in a semi-arid environment. Agronomy 2020, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M.S.A.; Brookes, P.C.; de la Fuente-Martinez, N.; Gordon, H.; Murray, P.J.; Snars, K.E.; Williams, J.K.; Bol, R.; Haygarth, P.M. Phosphorus solubilization and potential transfer to surface waters from the soil microbial biomass following drying-rewetting and freezing-thawing. Adv. Agron. 2010, 106, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Bai, E.; Li, M.; Zhao, C.; Yu, K.; Hagedorn, F. Responses of soil nitrogen and phosphorus cycling to drying and rewetting cycles: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 107896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de-Bashan, L.E.; Magallon-Servin, P.; Lopez, B.R.; Nannipieri, P. Biological activities affect the dynamic of P in dryland soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, Z.; Lin, J.; Zhu, B. Responses of soil carbon decomposition to drying-rewetting cycles: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2020, 361, 114069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Gao, D.; Hu, G.; Xu, W.; Zhuge, Y.; Bai, E. Drying-rewetting events enhance the priming effect on soil organic matter mineralization by maize straw addition. Catena 2024, 238, 107872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, M.-V.; Guhr, A.; Weig, A.R.; Matzner, E. Drying and rewetting of forest floors: Dynamics of soluble phosphorus, microbial biomass-phosphorus, and the composition of microbial communities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, X. Effect of repeated drying-rewetting cycles on soil extracellular enzyme activities and microbial community composition in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2020, 98, 103187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jarosch, K.A.; Mészáros, É.; Frossard, E.; Zhao, X.; Oberson, A. Repeated drying and rewetting differently affect abiotic and biotic soil phosphorus (P) dynamics in a sandy soil: A 33P soil incubation study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Nguyen, B.; Marschner, P. Effect of drying and rewetting on phosphorus transformations in red brown soils with different soil organic matter content. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 1573–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, P.; Yang, L.; Nie, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Zheng, P. Dependence of cumulative CO2 emission and microbial diversity on the wetting intensity in drying-rewetting cycles in agriculture soil on the Loess Plateau. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 220147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterly, C.R.; Bünemann, E.K.; McNeill, A.M.; Baldock, J.A.; Marschner, P. Carbon pulses but not phosphorus pulses are related to decreases in microbial biomass during repeated drying and rewetting of soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Haygarth, P.M. Phosphorus solubilization in rewetted soils. Nature 2001, 411, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brödlin, D.; Kaiser, K.; Kessler, A.; Hagedorn, F. Drying and rewetting foster phosphorus depletion of forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 128, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, M.-V.; Guhr, A.; Spohn, M.; Matzner, E. Release of phosphorus from soil bacterial and fungal biomass following drying/rewetting. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.L.; Driessen, J.P.; Haygarth, P.M.; Mckelvie, I.D. Potential contribution of lysed bacterial cells to phosphorus solubilisation in two rewetted Australian pasture soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Huo, T.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, T.; Liang, J. Response of soil organic carbon decomposition to intensified water variability co-determined by the microbial community and aggregate changes in a temperate grassland soil of northern China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 176, 108875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Bi, Q.; Li, K.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, C.; Lu, L.; Lin, X. Effect of soil drying intensity during an experimental drying-rewetting event on nutrient transformation and microbial community composition. Pedosphere 2018, 28, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Bi, Q.; Li, K.; Dai, P.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lv, T.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Significance of temperature and water availability for soil phosphorus transformation and microbial community composition as affected by fertilizer sources. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2017, 54, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri-Novair, S.; Mirseyed Hosseini, H.; Etesami, H.; Razavipour, T.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Astatkie, T. Short-term soil drying-rewetting effects on respiration rate and microbial biomass carbon and phosphorus in a 60-year paddy soil. 3 Biotech 2020, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, R.J.; Swift, R.S. Effects of air-drying on the adsorption and desorption of phosphate and levels of extractable phosphate in a group of acid soils, New Zealand. Geoderma 1985, 35, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Ge, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Ye, C.; Li, M.; Zhao, B.; Liang, A.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J. Responses of soil microbial community to drying-wetting alternation relative to tillage mode. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2020, 57, 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, M. Soil respiration, aggregate stability and nutrient availability affected by drying duration and drying-rewetting frequency. Geoderma 2022, 413, 115743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, H.; Haygarth, P.M.; Bardgett, R.D. Drying and rewetting effects on soil microbial community composition and nutrient leaching. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Bi, Q.; Xu, H.; Li, K.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, C.; Lu, L.; Lin, X. Degree of short-term drying before rewetting regulates the bicarbonate-extractable and enzymatically hydrolyzable soil phosphorus fractions. Geoderma 2017, 305, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Qin, S. Soil microbial biomass and activity response to repeated drying-rewetting cycles along a soil fertility gradient modified by long-term fertilization management practices. Geoderma 2010, 160, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lai, L.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Lin, Q. Soil microbial biomass carbon and phosphorus as affected by frequent drying-rewetting. Soil Res. 2016, 54, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisner, A.; Snoek, B.L.; Nesme, J.; Dent, E.; Jacquiod, S.; Classen, A.T.; Prieme, A. Soil microbial legacies differ following drying-rewetting and freezing-thawing cycles. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, G.; Ma, T.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Y.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Effects of vegetation restoration on soil aggregates, organic carbon, and nitrogen in the Loess Plateau of China. Catena 2023, 231, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Bing, M.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Hai, X.; Li, A.; Wang, K.; Wu, P.; et al. Effects of vegetation restoration types on soil nutrients and soil erodibility regulated by slope positions on the Loess Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Gregorich, E.G. Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, S.R.; Cole, C.V.; Watanabe, F.S.; Dean, L.A. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate. In United States Department of Agriculture Circular 939; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1954; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, D. Measuring soil microbial biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2004, 36, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, M.V.; Schramm, T.; Spohn, M.; Matzner, E. Drying-rewetting cycles release phosphorus from forest soils. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2016, 179, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denef, K.; Six, J.; Bossuyt, H.; Frey, S.D.; Elliott, E.T.; Merckx, R.; Paustian, K. Influence of dry-wet cycles on the interrelationship between aggregate, particulate organic matter, and microbial community dynamics. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, J. Effect of drying-wetting cycles on aggregate breakdown for yellow-brown earths in karst areas. Geoenviron. Disasters 2017, 4, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Funakawa, S.; Kosaki, T. Effect of repeated drying-rewetting cycles on microbial biomass carbon in soils with different climatic histories. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 120, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, S.; Green, D.M. Acid and alkaline phosphatase dynamics and their relationship to soil microclimate in a semiarid woodland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Hussain, N.; Bai, B.; Zhou, J.; Ren, Y. Effect of drying–rewetting alternation on phosphorus fractions in restored wetland. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Wei, X.; Shao, M. Soil type-dependent effects of drying-wetting sequences on aggregates and their associated OC and N. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2022, 10, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.M.; Cao, C.Y. Transformation and availability of inorganic phosphorus in calcareous soil during flooding and draining alternating process. Acta Pedol. Sin. 1997, 34, 382–391. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, M.S.A.; Brookes, P.C.; de la Fuente-Martinez, N.; Murray, P.J.; Snars, K.E.; Williams, J.K.; Haygarth, P.M. Effects of soil drying and rate of re-wetting on concentrations and forms of phosphorus in leachate. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2009, 45, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Bing, H.; Sun, H.; Luo, J.; Pu, S. Air-drying changes the distribution of Hedley phosphorus pools in forest soils. Pedosphere 2020, 30, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Zhang, G.; Li, T.; He, B. Fertilization and cultivation management promotes soil phosphorus availability by enhancing soil P-cycling enzymes and the phosphatase encoding genes in bulk and rhizosphere soil of a maize crop in sloping cropland. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Safe 2023, 264, 115441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.T.; Wang, J.J.; Zeng, D.H.; Zhao, S.Y.; Huang, W.L.; Sun, X.K.; Hu, Y.L. The influence of drought intensity on soil respiration during and after multiple drying-rewetting cycles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 127, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wei, X.; Shao, M. Drying-wetting cycles consistently increase net nitrogen mineralization in 25 agricultural soils across intensity and number of drying-wetting cycles. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 135574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.-R.; Doyle, A.; Holden, P.A.; Schimel, J.P. Drying and rewetting effects on C and N mineralization and microbial activity in surface and subsurface California grassland soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 2281–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erinle, K.O.; Li, J.; Doolette, A.; Marschner, P. Soil phosphorus pools in the detritusphere of plant residues with different C/P ratio—Influence of drying and rewetting. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2018, 54, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.J.; Han, C.L.; Kong, M.; Shi, X.Y.; Zdruli, P.; Li, F.M. Plastic film mulch promotes high alfalfa production with phosphorus-saving and low risk of soil nitrogen loss. Field Crops Res. 2018, 229, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.E.; Wallenstein, M.D. Soil microbial community response to drying and rewetting stress: Does historical precipitation regime matter? Biogeochemistry 2011, 109, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.