Abstract

Subsoiling is a highly effective deep tillage method used to mitigate soil compaction in orchard rows, a condition frequently resulting from repeated passes of agricultural machinery. This compaction can reduce water infiltration into deeper soil layers, leading to excessive surface water stagnation and a subsequent reduction in soil fertility. Subsoiling restores the structure of compacted soil by creating a vertical cut and lifting the ground without inverting the soil layers. This action promotes stable soil porosity and enhanced drainage, effectively eliminating the plough sole, and consequently improving root growth and nutrient absorption. Despite its benefits, subsoiling is an energy-intensive practice. Vibrating subsoilers can significantly reduce the high traction force required by conventional subsoilers, thereby enabling the use of smaller, less powerful tractors. This study investigated the performance of a single-shank subsoiler equipped with an innovative oscillating working tool, focusing on its dynamic-energy requirements, tillage quality, and the whole-body vibrations (WBV) transmitted to the tractor driver. Comparative tests were conducted in a compacted poplar grove using two 4WD tractors of different power and mass, with the subsoiler’s oscillating tool alternately activated and deactivated. The results demonstrated that the oscillating tool reduced draft force, traction power requirement, fuel consumption, and tractor slip, while maintaining tillage efficiency, displacing a greater mass of soil. However, a comparison of the measured vibrations indicated that their level reached a hazardous condition for the driver of the lower-power, lower-mass tractor when the oscillating tool was active.

1. Introduction

Soil compaction can occur naturally, but the primary cause is the repeated passes of agricultural machinery, particularly in orchard rows [1,2]. Even in areas managed with a continuous natural grass cover, the associated long-term no-tillage practice may lead to significant compaction [3,4,5,6]. Similarly, a conventional approach to site management involving ordinary surface tillage will inevitably create a hardpan layer over the years. The physical degradation of soil reduces both porosity and permeability. This, in turn, leads to a lower water infiltration capacity [7,8], resulting in surface water stagnation and an increased risk of erosion due to accelerated surface run-off, especially in hilly environments [9].

Conventional deep tillage within the orchard aims to disrupt the compacted soil above the hardpan layer. This is achieved through a vertical cut and lifting of the ground, importantly without inverting the tilled layers [10,11,12]. Consequently, this action promotes stable soil porosity and enhanced drainage, ultimately improving root growth and nutrient absorption [13]. Subsoilers are highly energy-intensive implements and were developed in a variety of configurations and sizes. The performance of conventional subsoiling is highly dependent on multiple factors, including shank design and layout, the inclusion of side wings on the foot, and the use of coulter. All these elements significantly affect the working depth and the profile of the loosened soil [14,15]. A major constraint on deep tillage may be the limited power available from the tractors commonly employed in the orchard industry. Among existing implements, vibrating subsoilers (also known as oscillating subsoilers) are recognized for their ability to significantly reduce the high draft force required for pulling the implement through the soil compared to an equivalent rigid system operating at the same speed and depth [16,17,18]. This reduction allows for a more effective utilization of the available tractor power [19,20,21]. Consequently, tractors in a smaller power class can be employed, or alternatively, a greater working depth and soil disruption may be achieved using the same power unit [22,23].

Different management strategies, such as dual depth tillage and dual pass approach, can be used to maximize the efficiency of this machinery. In orchards, subsoiling is typically performed with a single pass along the center of the row. Deeper tillage allows for a larger volume of loosened soil, enabling roots to access greater quantities of water and nutrients [24]. Enhanced root systems provide direct benefits by reducing reliance on irrigation and improving both yield and quality.

To evaluate several aspects of using a single shank subsoiler equipped with an innovative oscillating working tool, CREA carried out specific tillage tests. This tool consists of a horizontal metal plate, hinged behind the shank. During operation, the plate is raised at regular intervals along the cultivation horizon via a connecting rod driven by a crank mechanism, thereby displacing a larger volume of soil. The subsoiler was tested to investigate its power-energy requirements, the quality of the tilled soil, and the level of whole-body vibrations transmitted to the tractor driver’s seat by the oscillating tool.

Regarding this last aspect, in the agricultural sector, risks associated with routine activities that affect the health and safety of workers may include exposure to dust particles [25,26] and physical agents, such as mechanical vibrations [27,28,29]. Considering tractor drivers’ exposure to vibration risks during common agricultural operations, the Community Directive 2002/44/CE [30], established maximum values for the mechanical vibration exposure. This Directive was implemented in Italy by Legislative Decree 197 of 19 August 2005 [31], which outlines minimum protection requirements for workers and safety and health regulations. It was later incorporated and replaced by Legislative Decree 81/2008 [32], which fully integrates the principles of the original Directive. These regulations report the “Limit Value” (1.0 m s−2) and the “Action Value” (0.5 m s−2) as reference values for drivers’ exposure to the whole-body vibrations, establishing certain obligations. When daily exposure levels are not constant, the maximum level must be considered [33,34]. The test procedures for measuring and evaluating whole-body vibrations transmitted from the tractor seat to the driver are specified in the ISO 2631-1:1997/Amd 1:2010 standard [35]. This standard estimates the effects of vibrations on the driver’s health and comfort, and it outlines the location and direction of measurements, the equipment to be used, the duration of measurements, frequency weighting, assessment methods, and the evaluation of weighted root-mean-square (RMS) acceleration [36,37]. The normal driving position in tractors during tillage operations can lead to postural overload due to repeated rotations of the lumbar spine while seated [38]. This can result in musculo-skeletal disorders (MSDs) for the drivers [39,40,41,42].

A series of tests were performed within the untilled rows of a fifteen-year-old poplar grove, using the subsoiler with and without the oscillating tool engaged, at a constant tillage speed, aiming to compare the results under the two conditions. Tillage was executed at a maximum depth of 0.45 m, depending on the soil’s workability conditions, utilizing two 4WD tractors of different power and mass. The dynamic-energy parameters were measured according to the ENAMA test protocol No. 03 (Italian Agency for Agricultural Mechanization) [43], which is based on current international reference standards (EN, ISO, ASABE). Vibration measurements followed ISO 2631-1:1997. Data on the effective accelerations (awx, awy and awz) were collected. These measurements were focused on the frequency interval from 0.5 Hz up to 80 Hz, considered the most hazardous to the human body in a sitting position [44].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of the Subsoiler and Tractors

The tested subsoiler, manufactured by ONG company (Castel Bolognese, Italy), is a tractor-mounted implement weighing 400 kg (Figure 1), designed for deep soil tillage at depths ranging from 350 to 550 mm.

Figure 1.

(a) The coupling medium-power tractor-implement utilized in the tests; (b) View of the oscillating horizontal plate.

The mainframe features a reinforced box-type steel structure with an arched shape that facilitates optimal soil disruption, allowing for close proximity between the lower beam and the soil surface. The working depth is adjusted via the tractor linkage, while stabilizer side-wheels ensure consistent working depth. The linkage frame allows the connection to tractors of various size; however, a hydraulic top link is required for smaller tractors to fully lift the shank out of the ground. The tested implement consists of a single straight shank equipped with a sharpened wear shin on the leading edge. The shank’s point is fitted with a reversible share that is 0.10 m wide. The oscillating horizontal metal plate has a triangular shape with a central cutout for insertion onto the shank’s foot. The front end of the plate is hinged behind the share, while the back end connects to a plate to a quadrangular rod that shifts on a vertical axis. This rod is driven by a crank mechanism powered by the Power Take-Off (PTO). The plate oscillates at a frequency of 9 Hz, with amplitudes of ±70 mm. Additionally, this subsoiler can be equipped with a rear cage roller, which can be mounted directly behind the shank in place of the two side stabilizer wheels. The main characteristics of the subsoiler are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the subsoiler equipped with the oscillating plate.

The subsoiler was operated using two different tractors: a medium-powered 4WD tractor (Landini Legend 145, Reggiolo, Italy), with a nominal engine power of 103 kW and a total mass of 6230 kg, and a lower-powered 4WD tractor (New Holland T4.100 F, Turin, Italy) with a nominal engine power of 73 kW and a total mass of 3100 kg. The medium-powered tractor was equipped with 480/65 R28 front tires and 600/65 R38 rear tires, both inflated to 1.6 bar. The lower-powered tractor featured 280/70 R20 front tires and 420/70 R28 rear tires, each inflated to 1.5 bar. When coupled with the medium-powered tractor, the subsoiler was tested to evaluate energy requirements, tillage quality, and whole-body vibrations (WBV) transmitted to the driver. In contrast, when coupled with the lower-powered tractor, the experimental activity was limited to vibration measurements, in order to assess the WBV exposure under reduced tractor power and mass conditions. Both tractors were equipped with standard seats featuring spring suspension systems with adjustable stiffness based on the driver’s mass. The same driver, weighing 82 kg, operated the tractors in all tests. Prior to field testing, the medium-power tractor was tested on a dynamometric brake to verify efficiency and to generate the characteristic engine performance curves. During operations, the tractors worked with a locked differential. To minimize wheel slippage, front ballast weights of 420 kg for the Landini and 360 kg for the New Holland were added, respectively. The tractors were started at minimum engine speed and allowed to warm up for half an hour before the in-field tests by engaging their rear Power Take-Off (PTO) to heat the biodegradable fluids in operation [45,46]. Preliminary tests were conducted to determine the most suitable tractor settings for the experiments, including gear ratio and working speed.

2.2. Field Site

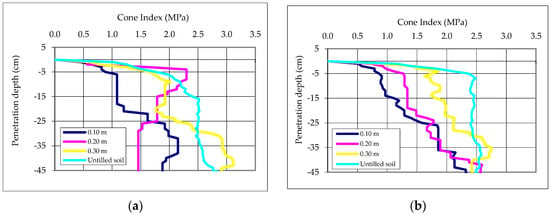

The tests were conducted at the experimental farm of CREA in Monterotondo (Rome), Italy (42°5′51.26″ N; 12°37′3.52″ E; 24 m a.s.l.), on silty-clay soil (clay 54.3%, silt 43.4%, sand 2.3%) classified according to the USDA soil system. The trials were carried out working the inter-rows of a fifteen-year-old flat poplar grove (<1% slope, planting distance: 5 × 7 m), which had not undergone deep tillage since planting and where only mowing was performed to maintain the grass cover. Prior to subsoiling, soil characteristics were measured at five randomly selected points within the test area at depths corresponding to the working layer. The parameters assessed included water content, dry bulk density, and penetration resistance (Cone Index). Water content and dry bulk density were determined from 100 cm3 soil samples collected at different depths using a manual coring tube (Eijkelkamp, Giesbeek, The Netherlands). Samples were oven-dried at 105 °C until constant mass was achieved [47]. Cone Index was measured according to ASAE standard S313.3 [48], using a hand-operated penetrologger (Eijkelkamp, Giesbeek, The Netherlands), which provided a detailed vertical profile of soil strength in undisturbed conditions. The measured soil characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average values of the physical-mechanical characteristics of the soil.

2.3. Operating and Tillage Quality Parameters

The effect of the vertical motion of the oscillating plate on soil was evaluated through two treatments:

- Treatment A: The subsoiler was used with the oscillating metal plate in action;

- Treatment B: The subsoiler was used with the oscillating metal plate inactive.

According to the ENAMA test protocol [43], the following dynamic-energy parameters of the coupling between the Landini medium-power tractor (103 kW) and the subsoiler were measured: actual time, width and depth of tillage; working speed; power transmitted by the PTO, force of traction required by the subsoiler and corresponding power under the measured working speed conditions; tractor’s slip; fuel consumption and energy required per surface unit and per volume unit of tilled soil. Each subsoiler configurations was tested with three replicates. Measurements were taken over a 100 m reference distance along each orchard row, with a single central pass to minimize branch breakage and root damage. Only a single forward speed was considered. Tillage quality was evaluated by determining the following parameters before and after the operation: cone index (soil penetration resistance), clod size distribution, and clod-breaking index.

In addition to the determination of soil cloddiness within the tilled layer, the quality of work can also be indirectly evaluated by observing the soil volume (and mass) affected by the subsoiler under different working modes [49,50]. For this purpose, a portable electronic penetrometer was employed. This instrument provides measurements of the average Cone Index of undisturbed soil along the layer affected by tillage. This parameter reflects soil resistance to shank penetration and serves as an indicator of tillage difficulty. Repeated measurements on soil disrupted by the shank pass, taken at varying distances from the furrow center, allow evaluation of the extent of subsoiler action (both width and depth) and comparison between treatments with and without the oscillating tool in action. Specifically, in each treatment, six sampling areas were identified along the furrows. Within each area, measurements were taken at 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 m from the furrow center (three replicates per depth/point, without considering outliers). The penetrometer recorded the force required to penetrate the soil with a cone tip of 60° apex angle and 10 mm2 base area, at a penetration speed of 30 mm s−1.

The cloddiness of the tilled soil was assessed by excavating a 0.5 m square trench to the working depth. Soil aggregates collected from this volume were air dried, weighed, and separated into six size classes using hand-operated standard sieves. Each class was assigned a characteristic index (Iai), ranging from 0 for the largest class to 1 for the smallest [51]. Cloddiness was then evaluated by calculating the percentage mass of each size class relative to the total sample mass. From the cloddiness, the clod-breaking index (Ia) is calculated by means of the Relation Equation (1):

where Mi·Iai is the product of the index assigned to a clod size class and the mass (kg) of soil belonging to the same class; Mt is the total mass of the sample (kg).

Following subsoiler passage, the working depth and the uniformity of the bottom of the tilled layer were measured on the same soil section, transversally to the working direction. These measurements were obtained as the standard deviations (σ) of data recorded by an in-house designed profile meter [52,53]: a laser sensor (Leica Geosystem Disto, Heerbrugg, Switzerland), mounted on a horizontal bar and moved stepwise by an electric motor. The sensor measured the distance from the soil surface at 5 mm intervals, thereby reconstructing the profile of both the soil surface and the bottom of the tilled layer.

Operating parameters of the tractor Landini-subsoiler system were collected using an integrated system composed of two units, a field unit and a support unit [54,55]. The field unit consisted of the tractor equipped with sensors and a PC (with a PCI acquisition card and LCD monitor), and a photocell system positioned along each test row indicating the start and end of tests. The support unit was a van configured as a mobile laboratory, parked at the field edge during tests. Its PC communicated with the tractor’s PC via a radio-modem system, enabling real-time monitoring of critical parameters, instrument performance, and data integrity. Transducers signals were recorded at a scan rate of 10 Hz. The support unit also housed equipment and instruments used for quality tillage evaluation, including the laser profile meter and sieves. The tractor was equipped with several sensors: a 3 kNm full scale torque-tachometer (HBM T10F/FS, Darmstadt, Germany) mounted on the PTO shaft to measure torque and rotational speed; an incremental encoder (Tekel TK510, Turin, Italy) positioned to measure peripheral velocity and rear-wheel slip over the reference distance; and a load cell (measuring range: 49 kN) (AEP Transducers TC4, Modena, Italy) installed in a drawbar to record traction force. During tests, the tractor–subsoiler system was pulled by a traction vehicle at the same speed measured during tillage. The traction vehicle, considered part of the field unit, transmitted its data to the support unit’s PC, ensuring synchronized acquisition of all parameters.

2.4. Vibrations Measurement

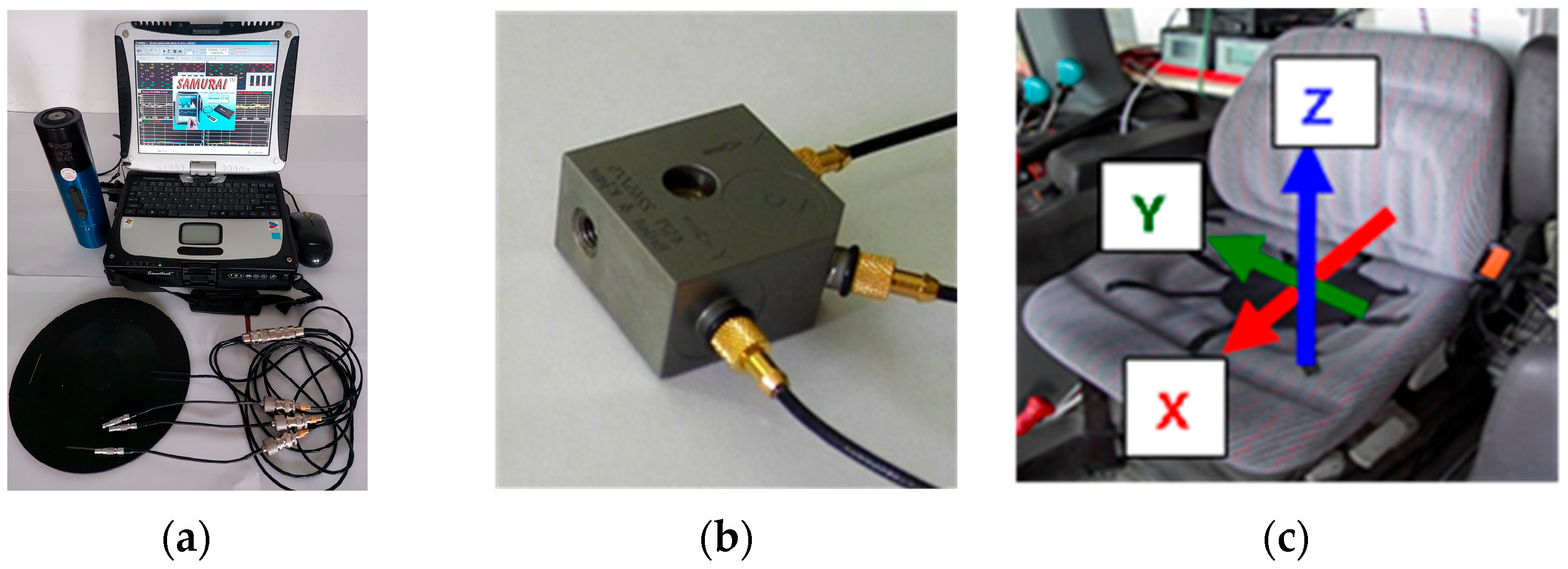

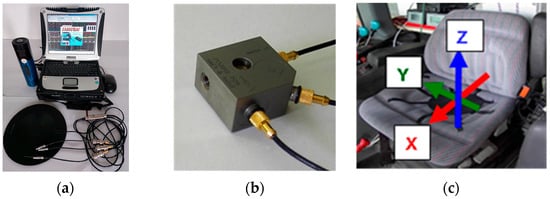

The tests were conducted to verify the level of whole-body vibration (WBV) transmitted to the tractor driver. Measurements were performed in accordance with ISO 8041-1:2017 [56], using the following instrumentation chain: (a) Triaxial seat accelerometer, mod. 4322 (Brüel & Kjær, Nærum, Copenhagen, Denmark); (b) Soundbook—eight-channel signal acquisition/processing system with “Samurai” software, version 1.7.14 (Spectra, Vimercate, Monza, Italy); (c) Triaxial accelerometer positioned on the tractor’s cab floor, mod. 4321 (Brüel & Kjær, Nærum, Copenhagen, Denmark); (d) Accelerometer calibrator, mod. 394C06 (PCB Piezotronics, Depew, NY, USA) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The instrumentation chain used in the tests. (a) Seat-mounted triaxial accelerometer, accelerometer calibrator, eight-channel soundbook-signal acquirer/processor; (b) Triaxial accelerometer positioned on the tractor’s cab floor; (c) The driver seat equipped with triaxial accelerometer and system of coordinates for the orientation of the accelerometer for seated position.

The accelerometer signal was calibrated at both the beginning and the end of the tests to ensure that deviations from the initial calibration remained within the limits established by ISO 16063-1:1998/Amd 1:2016 [57]. Measurements were carried out in compliance with the ISO 2631-1:1997/Amd 1:2010 standard, which specifies procedures for assessing vibration levels transmitted from the seat to the operator, and with Italian Legislative Decree 81/08, concerning occupational health and safety. For each treatment, three repetitions were performed with a sampling duration of 60 s, deemed sufficient to characterize the driver’s daily exposure to vibration risk and to ensure spectral stability and representativeness. The accelerometer, mod.4322, was positioned on the tractor seat according to ISO 2631, with axes oriented as follows (Figure 2c): (a) longitudinal x-axis (back—chest); (b) transverse y-axis (right side—left side); (c) vertical z-axis (pelvis—head). The triaxial accelerometer, mod. 4321, was positioned on the tractor cabin floor with the three axes x, y and z oriented like the seat accelerometer.

The measurements provided values of awx, awy and awz, i.e., the root-mean square (r.m.s.) of the frequency-weighted accelerations, expressed in m·s−2, simultaneously detected and calculated in one-third octave bands within the frequency range 0.5–80 Hz along the three axes of the acceleration vector. In accordance with ISO 2631-1:1997, the weighting filters Wd (for x and y axes) and Wk (for the z axis) were applied to the linear acceleration values. Frequency weighting is essential, as the health effects of vibration depend on the specific frequencies characterizing the stress experienced by the operator. For each axis, the frequency-weighted acceleration aw was obtained as Equation (2):

where aw(t) is the time-dependent, frequency-weighted acceleration signal, and T is the measurement duration (s).

From these values, the total acceleration av to which the whole body is exposed was calculated as Equation (3):

where awx, awy, awz are the r.m.s. frequency-weighted accelerations along the x, y, and z axes, respectively, and kx, ky, kz are correction coefficients depending on the operator’s posture. For a seated position, kx = ky = 1.4, and kz = 1.

Exposure to vibrations was quantified using the frequency-weighted equivalent acceleration over an 8-h workday, conventionally denoted as A(8) Equation (4):

where Tmax is the maximum time of exposure to av and varies depending on the value of A(8) adopted. It is calculated by making the formula explicit with respect to Tmax.

In WBV risk assessment, only the most stressed axis is typically considered. However, when the values of aw along two or more axes are comparable, A(8) is calculated using the vector sum av. ISO standards do not specify exposure limits, which are instead defined in Legislative Decree 81/08, Title VIII—Physical Agents, Chapter III—Protection of workers from the risks of exposure to vibrations. For a comprehensive evaluation, instantaneous peak levels (impulsive vibrations) were also assessed, ensuring they remained below crest factor 9, as required by ISO 2631-1:1997/Amd 1:2010.

2.5. Data Analysis

Direct vibration measurements provided the frequency analysis of linear axial accelerations which were processed in order to obtain the weighted axial accelerations (awx, awy and awz), the acceleration vectors (av), and the maximum exposure times (Tmax). As previously described, the tests compared vibration levels measured at the seat and chassis of two tractors of different mass and power during subsoiling, with the oscillating plate in action and inactive, resulting in four test conditions. Three replicates were performed for each test condition, yielding, separately for the seat and the chassis, a dataset of 12 values for each of the aforementioned parameters (awx, awy, awz and av). Each dataset was first tested for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Subsequently, multifactorial ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test was performed with R software (version 4.4.3) to assess the statistical significance of differences attributable to the factors of variation tractor type (tractor) and oscillating plate activation (treat), and to their interaction.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tillage Performance

Table 3 and Table 4 report, respectively, the results of the measurements concerning the dynamic-energy performances of the tractor–subsoiler system and the most significant parameters describing soil–machine interaction.

Table 3.

Main dynamic and energy parameters resulting from the tests and data dispersion (S.D., Standard Deviation; S.E., Standard Error).

Table 4.

Main parameters referring to the tillage quality and data dispersion (S.D., Standard Deviation; S.E., Standard Error).

The activation of the oscillating plate (Treatment A) occurs by engaging the tractor’s Power Take-Off (PTO), which transmits the power required to overcome the soil’s resistance to the oscillations. Compared to Treatment B, this results in higher values for forward speed, hourly fuel consumption, and average total engine power output, while lower values are observed for drawbar pull and wheel slip (Table 3). Given the same tractor settings (engine speed, gear ratio) in both cases, the 4.9 kW PTO power observed in Treatment A stems primarily from the transfer of a portion of the traction power (17.0 kW in Treatment A vs. 19.37 kW in Treatment B) and lower power dissipation due to slip (4.04 kW in Treatment A vs. 5.56 kW in Treatment B). This indicates that the oscillating device effectively performs a soil-shattering action within the tilled layer.

The orchard soil was highly compacted, which limited the achievable working depth during the tests to approximately 0.43 m. Table 3 also shows the fuel and energy requirements per unit area, calculated by combining the previous data with those in Table 4. It can be noted here that, while the tillage depth was nearly identical in both treatments, the working width recorded in Treatment A was 0.61 m, compared to 0.34 m in Treatment B. These figures significantly impact the calculation of the actual working time and, consequently, of fuel consumption, total energy required, and energy dissipated by slippage per hectare; in Treatment A, these are reduced by 44.6%, 45.9%, and 61.1%, respectively. Similarly, a 45% reduction is observed in the energy required per cubic meter of tilled soil.

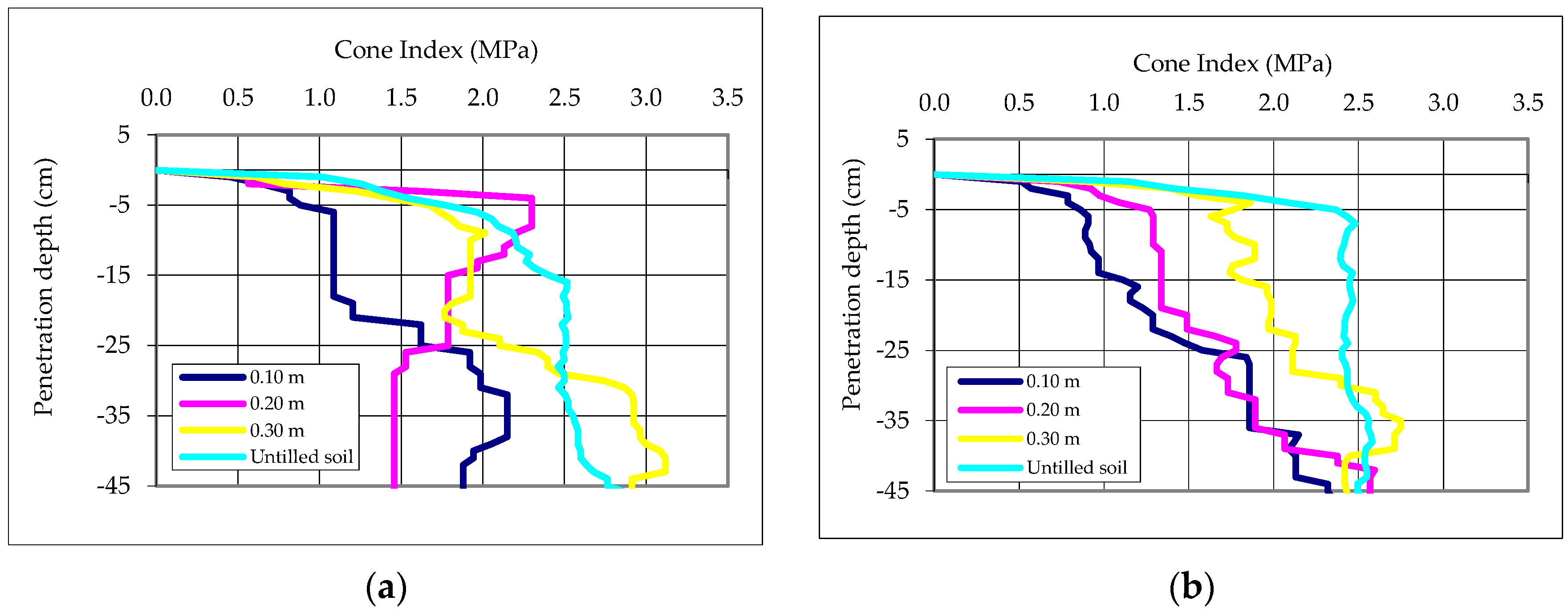

Tillage quality was evaluated through the consistency of the disrupted soil, as shown in Figure 3, which shows Cone Index (C.I.) values measured in six sampling areas before and after tillage, at 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30 m from the furrow center opened by the shank. In treatment A, the irregular trend of C.I. values indicates the presence of fissures even at greater depths, reflecting extensive soil disruption. Specifically: at 0.10 m from the furrow center, C.I. values were particularly low in the 0–0.20 m layer due to fissures and gradually increase at greater depth; at 0.20 m, C.I. values were higher at 0.10 m depth but lower at 0.30 m, revealing deep fissures created by the subsoiler; at 0.30 m, C.I. values showed an increasing trend, reaching high levels in deeper layers. This pattern confirms that the oscillating plate enhanced the shattering effect of the subsoiler, promoting deeper soil loosening. In contrast, treatment B exhibited a more regular C.I. trend, increasing with distance from the furrow center, indicating that the soil was subjected to a less disruptive action. This highlights the role of the oscillating plate in improving soil fracturing and reducing compaction beyond the immediate furrow zone.

Figure 3.

The average Cone Index in the three positions from the furrow centre. (a) Treatment A: oscillating plate in action; (b) Treatment B: oscillating plate inactive.

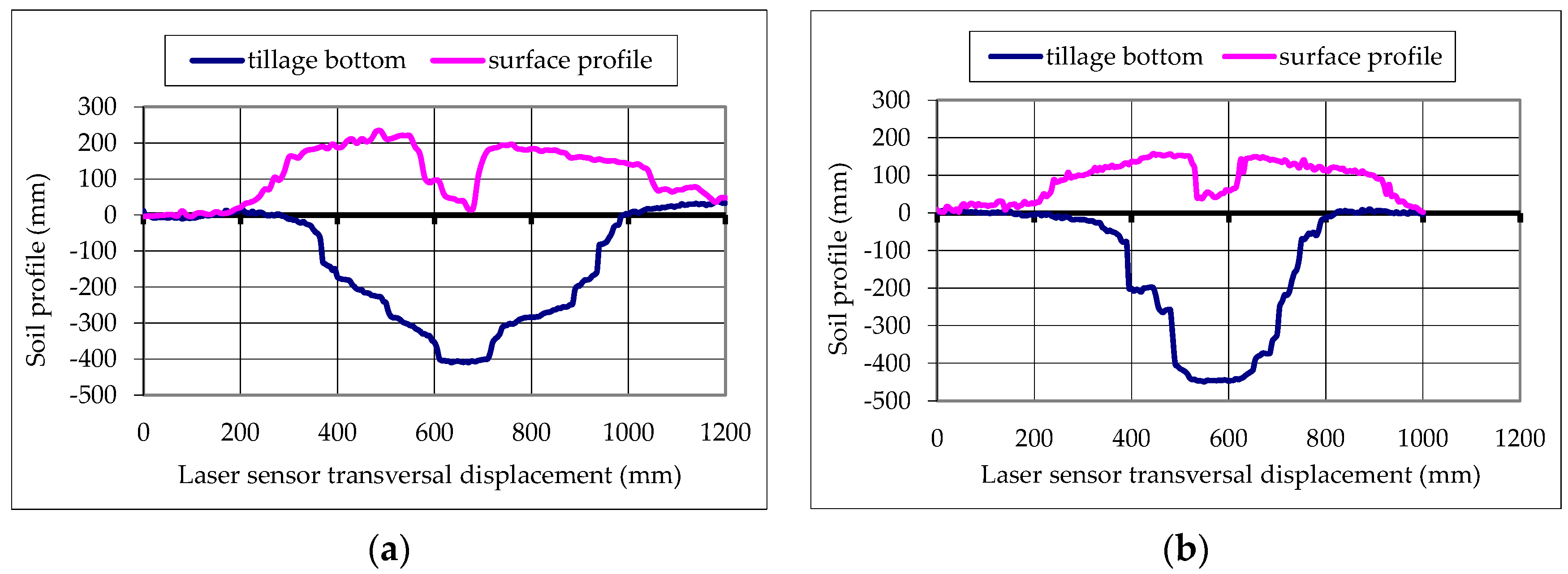

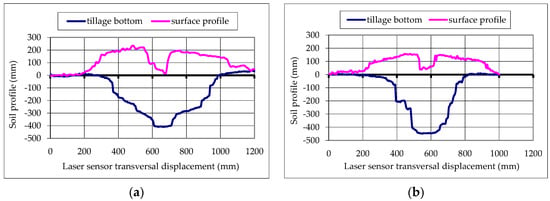

After excavation of a transversal trench, the cross-sectional area of the tillage profile, the actual tillage width, and the bottom of the tilled layer were scanned using a laser profile meter (Figure 4). The results clearly show that the tilled cross-section was larger in treatment A compared to treatment B, where the plate remained inactive. The grooves produced by the shank were more pronounced when the oscillating plate was active, confirming its contribution to widening the effective tillage profile.

Figure 4.

Soil profile after the tillage with the subsoiler. (a) Treatment A: oscillating plate in action; (b) Treatment B: oscillating plate inactive.

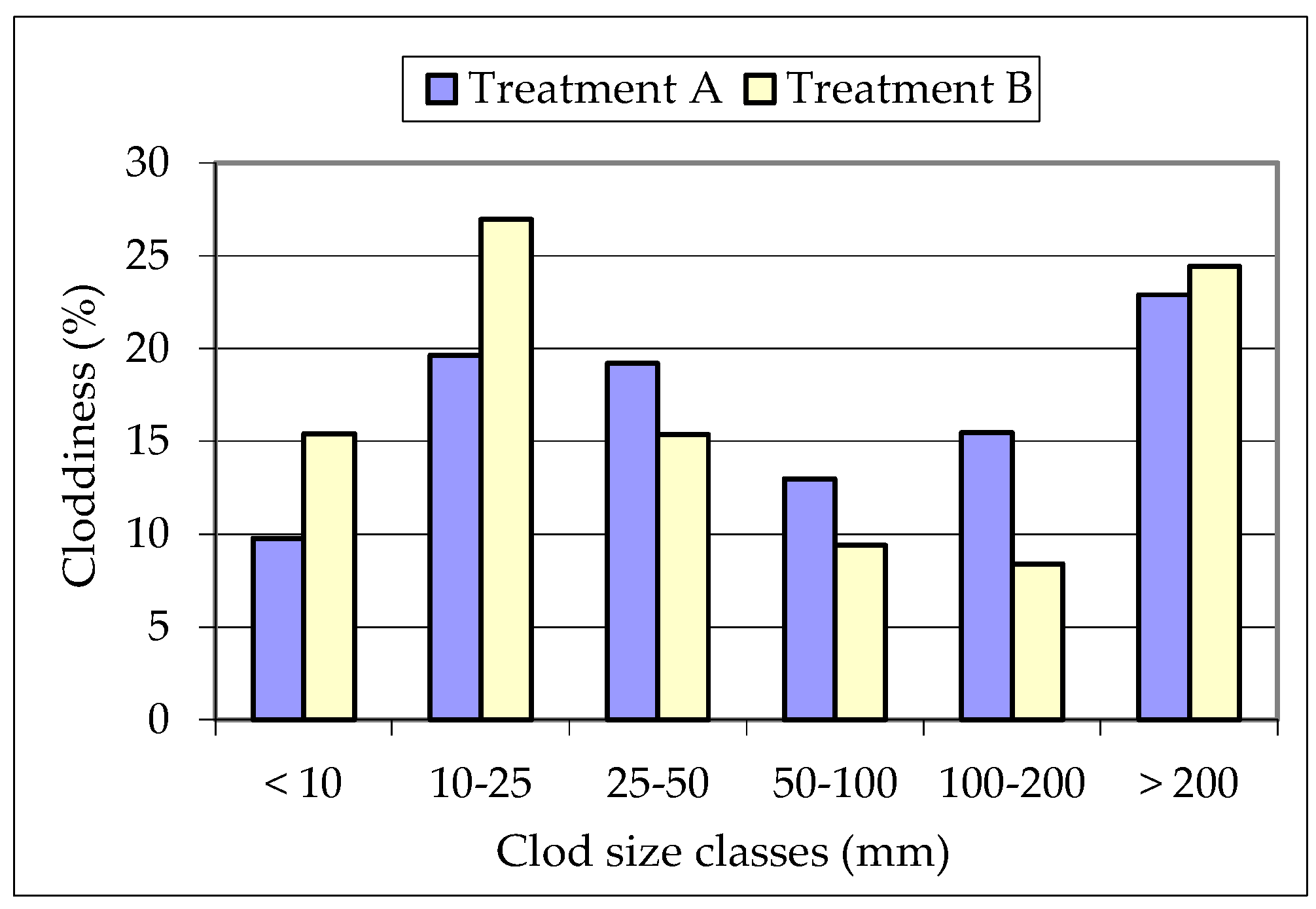

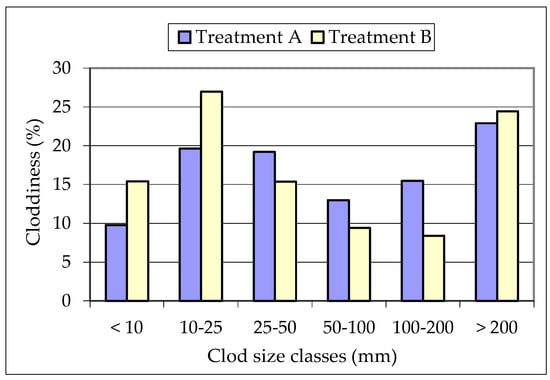

Regarding soil cloddiness, the clods produced by deep tillage were classified into six size categories (Figure 5). The results confirm that the subsoiler performs a very effective loosening and shattering action. In trials where the oscillating plate was active, approximately 71% of total clods belonged to the larger size classes (>25 mm) compared to 58% when the plate was inactive. This demonstrates that the oscillating plate enhanced soil shattering, producing larger aggregates and improving subsoil drainage capacity. The highest clod-breaking index was observed in treatment B, indicating that the inactive plate produced finer soil particles (Table 4). Soil elevation along the subsoiling line was minimal and could be further reduced by equipping the subsoiler with a cage roller, which would level the tilled soil. This improvement would promote greater stability conditions for the tractor during subsequent agricultural operations (e.g., spraying, fertilization). Furthermore, the oscillating plate provided a better balance between soil loosening and drainage improvement, which is particularly beneficial in compacted orchard soils.

Figure 5.

Soil cloddiness after the tillage tests with the oscillating subsoiler.

3.2. Measurement of Vibrations

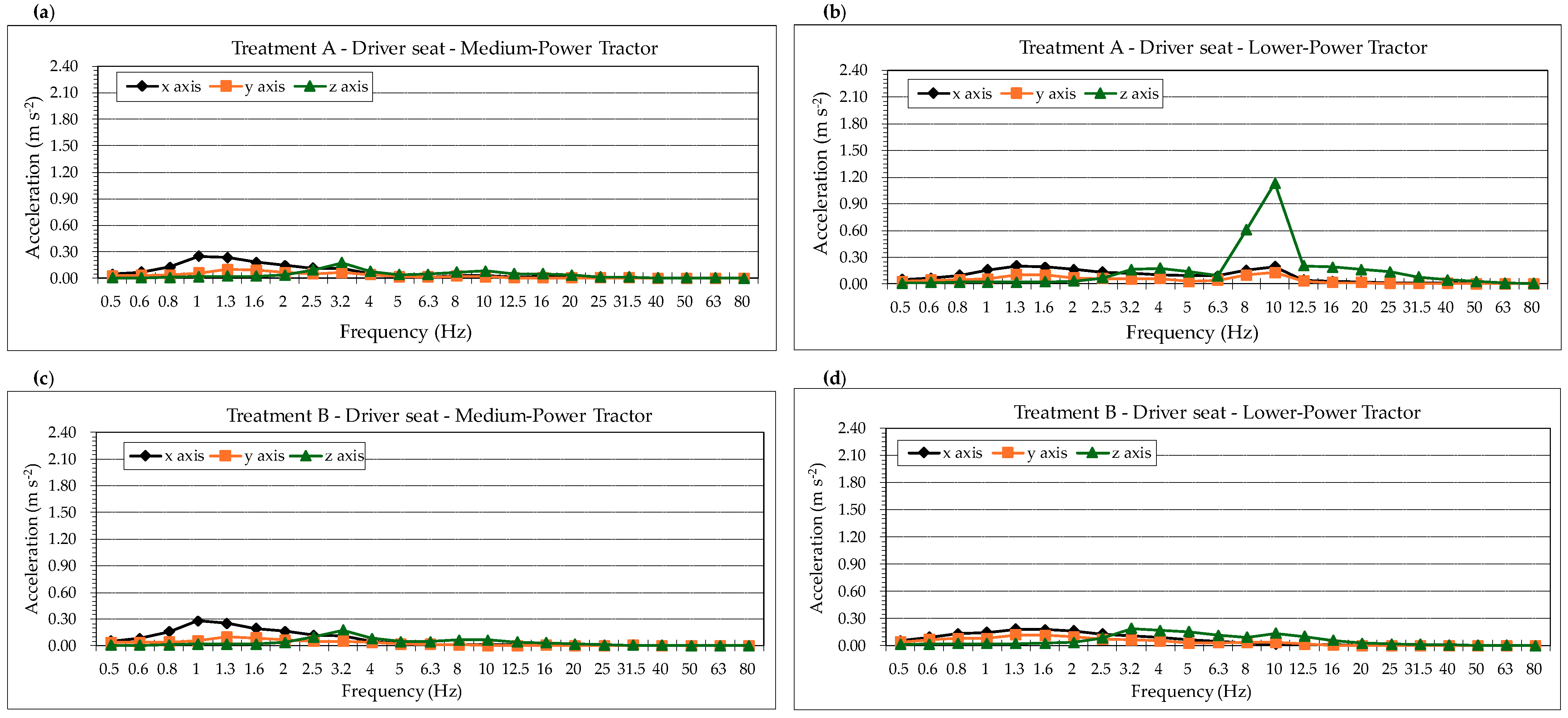

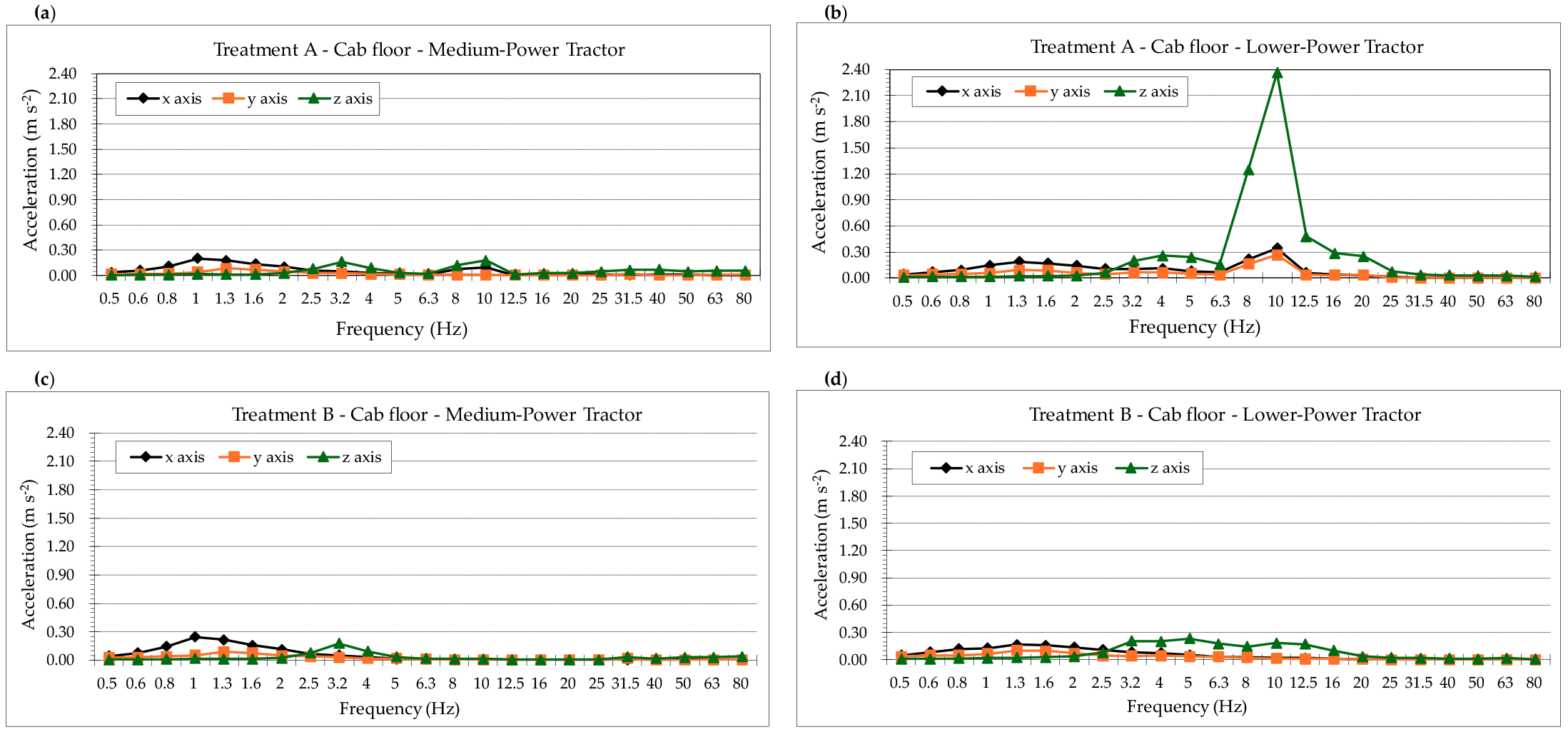

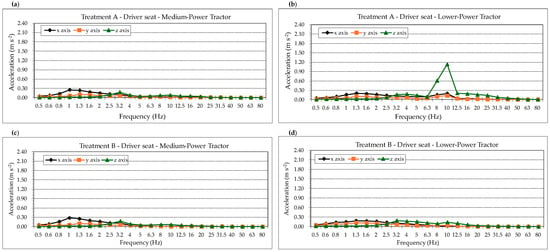

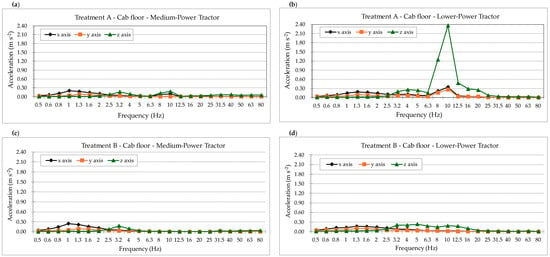

The tests were designed to evaluate the effect of the oscillating metal plate of the subsoiler on the level of vibrations transmitted to the tractor drivers whole body (WBV). To this purpose, the subsoiler was coupled with both a medium-powered and a lower-powered 4WD tractors in order to assess WBV exposure under different tractor power and mass conditions. Vibrations propagate from the soil to the driver’s seat through various tractor components, including tires and chassis [58,59], axles [33,60], cabin, and seat suspensions [61,62,63]. The measured quantity was acceleration (a, m s−2), weighted using appropriate filters in accordance with ISO 2631-1:1997. This procedure allows quantification of WBV exposure within the reference frequency band of 0.5–80 Hz, which is considered particularly harmful for the human body in a seated position. The results of the vibration level tests are summarized in Table 5 and Table 6, which report the weighted r.m.s. axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) measured both at the driver’s seat of medium- and lower-power tractors operating with the subsoiler oscillating plate active (Treatment A) or inactive (Treatment B), and at the floor of the tractor cabs. The crest factor values (CF) have not been reported, as they are all less than 9. The vibration measurements are also graphically represented in the diagrams in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 5.

Measured values of weighted r.m.s. axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) at the driver’s seat of tractors and the resulting acceleration sum vector (av). Te: time of exposure at driver seat. AV: Action Value (A(8) = 0.5 m s−2); LV: Limit Value (A(8) = 1 m s−2).

Table 6.

Measured values of weighted r.m.s. axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) at the tractor’s cab floor and the resulting acceleration sum vector (av).

Figure 6.

Weighted accelerations recorded on the driver’s seat of the tractors: (a) Subsoiler (Treatment A) coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor; (b) Subsoiler (Treatment A) coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor; (c) Subsoiler (Treatment B) coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor; (d) Subsoiler (Treatment B) coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor.

Figure 7.

Weighted accelerations recorded on the tractor’s cab floor: (a) Subsoiler (Treatment A) coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor; (b) Subsoiler (Treatment A) coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor; (c) Subsoiler (Treatment B) coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor; (d) Subsoiler (Treatment B) coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor.

In Figure 6a (Treatment A: subsoiler coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor and oscillating plate active), vibrations recorded on the driver’s seat along the z-axis (vertical axis) are very low. Consequently, the main motion perceived by the operator is pitching. The dominant curve corresponds to the x-axis (longitudinal axis), with a peak of 0.248 m s−2 at 1 Hz. As for the y-axis (transversal axis), values remain very low, confirming that tillage with the subsoiler occurs in the forward direction, in a straight line, without significant lateral shaking.

In Figure 6b (Treatment A: subsoiler coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor and oscillating plate active), the z-axis curve (vertical axis) recorded on the driver’s seat is the most critical. The peak at 10 Hz is 1.13 m·s−2, far exceeding the limit value established by Italian Legislative Decree 81/08 (1.00 m·s−2) despite the 50% reduction of the vibration levels transmitted from the cabin floor, which reached 2.364 ms−2 at the same frequency of 10 Hz (Figure 7b). This is likely not due to the tractor suspension system, which operates at lower frequencies, but rather to the specific working frequency of the oscillating subsoiler. Operating at depth with an oscillatory motion, the plate adds a significant contribution to vibrations generated by the engine and tractor movement. The plate, impacting the soil and releasing elastic energy, generates mechanical vibrations transmitted first to the tractor frame and then to the driver’s seat. At low frequencies (0.5–2 Hz), the z-axis shows values close to zero, indicating that the seat suspension system effectively compensates for bumps and soil irregularities. During tillage with the oscillating subsoiler, draft resistance varies continuously, causing slight oscillations in traction (pitching). Although present, this phenomenon produces relatively low vibrational values and does not represent a major risk, as shown by the x-axis curve with a small peak (0.201 m·s−2) at 1.3 Hz. The peak at 10 Hz (0.196 m·s−2) is a crosstalk effect of the dominant vertical vibration, which is so strong that it also affects the seat backrest horizontally.

Comparing Figure 6c,d (Treatment B: subsoiler coupled with both Medium- and Lower-Power Tractors, oscillating plate inactive) with previous tests (Figure 6a,b), it is evident that using the subsoiler with the plate inactive results in minimal or no risk for driver. The analysis confirms that, without oscillating input from the implement, exposure to seat-transmitted vibrations remains well below regulatory limits. Both tractors, when not stressed by implement-induced vibration, provide high levels of safety and comfort at the driver’s seat.

The use of a Medium-Power tractor (Figure 6a,c) markedly attenuates the vibrational response compared to the Lower-Power tractor–subsoiler system. The most evident difference is the disappearance of the 10 Hz peak observed in Figure 6b. This demonstrates the positive effect of greater tractor mass: its inertia absorbs high-frequency vibrations generated by the implement during soil tillage, preventing them from reaching the seat. In summary, the spectrum indicates that the medium-power tractor, probably thanks to an efficient suspension system (particularly at the seat and/or cabin level), manages the significant stress induced by the oscillating subsoiler, keeping most of the vibrational energy below the regulatory limit values.

Table 5 further indicates the maximum operator exposure times during an 8-h workday to avoid exceeding the Action Value (AV) and the Limit Value (LV). In all cases, the A(8) daily exposure value was calculated using the axis that exhibited the highest vibration levels. Specifically, for the medium-powered tractor, the x-axis was used for both treatments, whereas for the lower-powered tractor, the z-axis was considered. This analysis is essential for operator safety, since Legislative Decree 81/08, Title VIII—Physical Agents, Chapter III—Protection of Workers from Risks of Exposure to Vibrations, Article 201—Exposure Action Values and Limit Values, establishes that for whole-body vibrations, the daily Action Value is 0.5 m s−2, while the daily exposure Limit Value is 1.0 m s−2.

The most critical condition occurs when using a lower-power, lower-mass tractor coupled with the subsoiler and the oscillating plate active (Treatment A). In this case, the operator can work for only about one hour per day before exceeding the AV, and just over four hours before exceeding the LV. The situation improves with the medium-power tractor: here, the AV is exceeded only after approximately 4.5 h of work, while the LV is never exceeded within a standard 8-h shift. When operating with both tractors and the subsoiler with the oscillating plate inactive (Treatment B), the operator can work for about four hours without exceeding the AV, and for eight hours without ever exceeding the LV. In both treatments (A and B), care must be taken to avoid exceeding the AV. In such cases, employers are required to develop and implement technical and organizational measures to minimize exposure and associated risks. These measures include limiting the duration and intensity of vibration exposure, organizing appropriate working schedules, and ensuring adequate shifts and rest periods.

In Figure 7a (Treatment A: subsoiler coupled with the Medium-Power Tractor and oscillating plate active), the frequency spectrum analysis of the accelerations recorded on the tractor’s cab floor highlights two frequency bands with significant peaks. The first is the low-frequency band (0.5–2 Hz), where the x-axis shows a maximum peak of 0.203 m·s−2 at 1 Hz, and the y-axis shows a peak of 0.081 m·s−2 at 1.3 Hz. These bands are typically associated with rigid tractor motion (bouncing and pitching) induced by driving on uneven soil. The second is the mid-frequency band (2.5–10 Hz), where the z-axis shows two significant peaks: one at 3.2 Hz (0.163 m·s−2) and a dominant peak at 10 Hz (0.177 m·s−2). This second band is the most critical for whole-body vibration (WBV) and spinal health, as it is associated with risks of low back pain and spinal trauma. Peaks in this band are generally linked to the resonance frequency of the tractor seat and cabin, which amplify vibrations originating from the frame and the oscillating implement. The dynamic interaction of the subsoiler’s straight shank with the soil may significantly contribute to these frequencies. In Figure 7b (Treatment A: subsoiler coupled with the Lower-Power Tractor and oscillating plate active), the three curves reveal a much more critical situation compared to the previous analysis, characterized by extremely high structural resonance. The most alarming result is the 10 Hz peak in the z-axis curve, which reaches a weighted acceleration value of 2.364 m·s−2. According to ISO 2631-1, the frequency band between 2 and 20 Hz represents the zone of maximum sensitivity for the seated human body. Vibrations within this range distort the normal biological and psycho-physiological responses of the operator to mechanical stimuli, potentially leading to musculoskeletal alterations, cardiovascular disorders, and impairments of the digestive system. Resonance at 10 Hz is extremely dangerous, indicating that the excitation frequency of the tractor–subsoiler system is perfectly aligned with a critical natural frequency.

In Figure 7c,d (Treatment B: subsoiler coupled with both Medium- and Lower-Power Tractors, oscillating plate inactive) the frequency spectrum analysis showed a behavior similar to that highlighted in Figure 6c,d. Using the subsoiler with the inactive plate did not result in additional vibration peaks or significant amplifications at the cab floor level, with values remaining well below regulatory limits.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The analysis focused on the data series of weighted axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) and the resultant acceleration vector (av) recorded at the driver seat and the tractor’s cab floor, as reported in Table 5 and Table 6. The Shapiro–Wilk test consistently confirmed the normal distribution of the values. Subsequently, the dataset was subjected to multifactorial ANOVA. In cases of significant factor interaction, Tukey’s post-hoc test was applied to perform multiple mean comparisons and identify significant differences. These analyses corroborate the observations described above.

Table 7 presents the ANOVA results for the driver’s seat. Highly significant differences were observed along the Z-axis for both variation factors (tractor and treatment) and their interaction, while no significant effects were found on the X-axis. The acceleration along the Y-axis (awy) was significantly influenced by the tractor type. A similar trend to that of the Z-axis was observed for the resultant acceleration vector (av).

Table 7.

ANOVA results for weighted axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) at the driver’s seat and the resulting acceleration sum vector (av).

Tukey’s test on the data in Table 7 involved multiple mean comparisons related to factor interactions. The results are reported in Table 8, ordered by increasing adjusted p-values. No significant differences were observed for awx. For awy, although not significant in the ANOVA, three pairs showed significant differences. In 80% of the significant comparisons, the medium-power tractor versus the lower-power tractor was involved, confirming tractor type as the discriminating factor in determining whether the oscillating plate in active mode is acceptable.

Table 8.

Tukey’s pairwise test of interactions from the ANOVA reported in Table 7.

Table 9 and Table 10 show the results of the same analysis performed on the dataset from cab floor measurements. In this case, the absence of damping elements (apart from the tires) emphasized the differences in vibration levels determined by tractor type and oscillating plate activation, which became consistently significant even on the X and Y axes. However, the trend of the p-values in Table 9 indicates that significance progressively increases from awx to awy to awz, and finally to av, thus amplifying the same trend observed at the driver’s seat (Table 7).

Table 9.

ANOVA results for weighted axial accelerations (awx, awy, awz) at the tractor’s cab floor and the resulting acceleration sum vector (av).

Table 10.

Tukey’s pairwise test of interactions from the ANOVA reported in Table 9.

The same considerations discussed for Table 8 also apply to the results of Tukey’s test for the tractor’s cab floor data reported in Table 10. However, the absence of any damping effect at the mainframe level accentuates the differences between pairs, as evidenced by the higher p-adjusted values compared to those in Table 8. Notably, significant differences were also observed for awx, which were not present in the driver’s seat analysis.

4. Conclusions

The effectiveness of the subsoil tillage in orchard is strongly conditioned by soil conditions: in the presence of an extremely compacted soil, energy requirements and tractor’s slip are excessive, and the working depth had to be reduced. For this study, we tested a single-shank subsoiler equipped with an innovative oscillating working tool, to evaluate its performance across several key areas: energy requirements, tillage quality, and the level of whole-body vibrations (WBV) transmitted to the tractor driver. A series of comparative tests were conducted using two 4WD tractors with different power and mass. The subsoiler was operated with and without the oscillating tool engaged, at a constant tillage speed. Results demonstrated that in the medium-powered tractor, the oscillating plate reduced traction power requirement, tractor slip and fuel and energy requirements per hectare surface, and enhanced soil disruption, particularly at greater depths, thereby mobilizing a larger soil mass. These effects are agronomically relevant, as they promote better root penetration and water infiltration in compacted soils. Although treatment B achieved higher clod-breaking index, especially evident in the uppermost layers, treatment A (with oscillating plate active), due to the presence of bigger clods in the deeper layers, could produce a more favourable tillage profile for long-term soil health and water management. Soil elevation along the subsoiling line was minimal in both treatments and could be further reduced by equipping the ripper with a cage roller, which would level the tilled soil. This adjustment would improve tractor stability during subsequent operations such as spraying and fertilization, ensuring greater efficiency in orchard management. Overall, the oscillating plate represents a promising solution for improving the quality of subsoil tillage in orchards, combining energy efficiency with agronomic benefits. Future studies should investigate its long-term impact on crop yield and soil physical properties (perhaps by further evaluating water infiltration and changes in soil bulk density) to validate its broader applicability.

Regarding vibrational comfort, while the vibrations generated by the oscillating plate and transmitted by the medium-powered tractor are extremely low, a tractor with lower power and mass, equipped with an inadequate suspension system, can trigger a devastating resonance when operating the subsoiler with the oscillating plate active, leading to exposure to intolerable vibration levels. Spectral analysis, in fact, highlighted a specific criticality on the vertical axis (z-axis) in the frequency range at 10 Hz, particularly with the lower-power tractor, with accelerations that far exceed the Limit Value (1.00 m s−2), indicating resonance phenomena aligned with the natural frequency of the tractor–implement system. In contrast, the medium-power tractor attenuated high-frequency vibrations, suppressing the 10 Hz peak and keeping WBV exposure below action thresholds. However, regarding the awz peak observed at 10 Hz, its origin could be better identified in further study through tests based on synchronized measurements of the PTO speed/oscillation frequency and tractor-to-seat transmissibility. Alternatively, a perturbation test (varying the oscillation frequency, forward speed, or tire pressure) could be conducted to verify any peak migration. Overall, the oscillating plate improved the soil–machine interaction and energy efficiency of the medium-power tractor. Regarding its vibrational impact, test results indicate that this is closely linked to the tractor’s mass. In the case of the medium-power tractor, no significant differences were found between vibration levels with the device active versus inactive. In contrast, for the lower-power tractor, the extremely high structural vibration levels observed following the activation of the oscillating mass were not effectively reduced by the seat suspension. Given that the Whole-Body Vibration (WBV) levels rendered the equipment unsuitable for this type of tractor, the dynamic-energy performance and tillage quality assessment tests were not performed. The findings highlight the importance of matching implement design with tractor characteristics to ensure both operational sustainability and driver safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F., D.P. and L.F.; methodology, R.F. and L.F.; software, G.V. and L.F.; validation, R.F., M.P. and R.T.; formal analysis, C.C.; investigation, R.G.; resources, G.V.; data curation, L.F., R.G. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.F., D.P. and R.T.; visualization, R.G.; supervision, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special appreciation to Marco Carbonetti and Massimo Terlizzi (CREA) for their precious technical support during the realization of the field tests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WBV | Whole Body Vibration |

| ASAE | American Society of Agricultural Engineers |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| ENAMA | Italian Agency for Agricultural Mechanization |

References

- Servadio, P. Applications of empirical methods in central Italy for predicting field wheeled and tracked vehicle performance. Soil Till. Res. 2010, 110, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López De Herrera, J.; Tejedor, T.H.; Saa-Raquejo, A.; Tarquis, A.M. Effects of tillage on variability in soil penetration resistance in an olive orchard. Soil Res. 2016, 54, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, T.; Sandin, M.; Colombi, T.; Horn, R.; Or, D. Historical increase in agricultural machinery weights enhanced soil stress levels and adversely affected soil functioning. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 194, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin, K.; Kuhwald, M.; Brunotte, J.; Duttmann, R. Wheel load and wheel pass frequency as indicators for soil compaction risk: A four-year analysis of traffic intensity at field scale. Geosciences 2020, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, K.; Che, Y. Soil compaction from wheel traffic under three tillage systems. Agriculture 2022, 12, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneedse, D.; Tranchand, E.; Barbedette, M. Effect of crop covers in walnut orchard. Acta Hortic. 2025, 1, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Défossez, P.; Richard, G.; Boizard, H.; O’Sullivan, M.F. Modelling change in soil compaction due to agricultural traffic as function of soil water content. Geoderma 2003, 116, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, T.; Braun, S.; Keller, T.; Walter, A. Artificial macropores attract crop roots and enhance plant productivity on compacted soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaoui, A.; Rogger, M.; Peth, S.; Blöschl, G. Does soil compaction increase floods? A review. J. Hydrol. 2018, 557, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, R.L.; Bergtold, J.S. In-row subsoiling: A review and suggestion for reducing cost of this conservation tillage operation. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2007, 23, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanigliulo, R.; Biocca, M.; Pochi, D. Effects of six primary tillage implements on energy inputs and residue cover in Central Italy. J. Agric. Eng. 2016, 47, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongcheng, Z.; Zhongfeng, Z.; Cong, C.; Xiangkun, R. Design and experiment of subsoiling rotary tillage combined soil preparation machine in northwest arid area. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2025, 46, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; Denardin, J.E.; Pauletto, E.A.; Faganello, A.; Spinelli Pinto, L.F. Effect of soil subsoiling on soil structure and root growth for a clayey soil under no-tillage. Geoderma 2015, 259–260, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Shahgholi, G.; Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Tash-Shamsabadi, H. The effect of new wings on subsoiler performance. Appl. Eng. Agric 2016, 32, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aabagh, H.A.A.; Hilal, Y.Y.; Mahdi, K. Comparison of subsoiler performance using different vibration wings designs. Acta Technol. Agric. 2025, 28, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalan, E.P.; Salokhe, V.M.; Gupta, C.P.; Niyamapa, T. Performance of an oscillating subsoiler in breaking a hardpan. J. Terramech. 1999, 36, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; He, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, W. Optimization of structural parameters of subsoiler based on soil disturbance and traction resistance. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2017, 48, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Che, D.; Liu, G.; Yu, L.; Ding, Q. Soil tillage fragmentation efficiency for paddy soil with subsoiling. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agric. Ambient. 2025, 29, e292064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, N.B.; Drury, C.F.; Reynolds, W.D.; Yang, X.M.; Li, Y.X.; Welacky, T.W.; Stewart, G. Energy inputs for conservation and conventional primary tillage implements in a clay loam soil. Trans. ASABE 2008, 51, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Sozzi, M.; Gasparini, F.; Marinello, F.; Sartori, L. Combining simulations and field experiments: Effects of subsoiling angle and tillage depth on soil structure and energy requirements. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi-Marquez, F.; Martinez-Reyes, E.; Morales-Morales, C.; Ramos-Cantu, L.; Castro-Bello, M.; Gonzalez-Lorence, A. Subsoiler tool with bio-inspired attack edge for reducing draft force during soil tillage. AgriEngineering 2024, 6, 2678–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.D.; Park, S.U.; Kim, W.S. Development of a real-time tillage depth measurement system for agricultural tractors: Application to the effect analysis of tillage depth on draft force during plow tillage. Sensors 2020, 20, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochi, D.; Fanigliulo, R.; Pagano, M.; Grilli, R.; Fedrizzi, M.; Fornaciari, L. Dynamic-energetic balance of agricultural tractors: Active system for the measurement of the power requirements in static test and under field conditions. J. Agric. Eng. 2013, 44, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.C.; Figueiredo, G.C.; Mafra, A.L.; Rosa, J.D.; Yoon, S.W. Deep subsoiling of a subsurface-compacted typical hapludult under citrus orchard. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2013, 37, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, M.; Fanigliulo, R.; Gallo, P.; Pulcini, P.; Pochi, D. The assessment of dust drift from pneumatic drills using static tests and in-field validation. Crop Prot. 2015, 71, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biocca, M.; Pochi, D.; Fanigliulo, R.; Gallo, P.; Pulcini, P.; Marcovecchio, F.; Perrino, C. Evaluating a filtering and recirculating system to reduce dust drift in simulated sowing of dressed seed and abraded dust particle characteristics. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, A.J.; Price, J.S.; Stayner, R.M. Whole-body vibration: Evaluation of emission and exposure levels arising from agricultural tractors. J. Terramechanics 2007, 44, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Samuel, S.; Singh, H.; Kumar, Y.; Prakash, C. Evaluation and analysis of whole-body vibration exposure during soil tillage operation. Safety 2021, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncescu, T.-A.; Persu, I.C.; Bostina, S.; Biris, S.S.; Vilceleanu, M.-V.; Nenciu, F.; Matache, M.-G.; Tarnita, D. Comparative Analysis of Vibration Impact on Operator Safety for Diesel and Electric Agricultural Tractors. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 on the Minimum Health and Safety Requirements Regarding the Exposure of Workers to the Risks Arising from Physical Agents (Vibration) (Sixteenth Individual Directive Within the Meaning of Article 16(1) of Directive 89/391/EEC); Joint Statement by the European Parliament and the Council; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Legislativo 19 agosto 2005, n. 187—Attuazione della direttiva 2002/44/CE sulle prescrizioni minime di sicurezza e di salute relative all’esposizione dei lavoratori ai rischi derivanti da vibrazioni meccaniche. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, 21 September 2005; n. 220 del.

- Decreto Legislativo 9 aprile 2008, n. 81—Attuazione dell’articolo 1 della Legge 3 agosto 2007, n. 123 in materia di tutela della salute e della sicurezza nei luoghi di lavoro. Gazzetta Ufficiale della Repubblica Italiana, 30 April 2008; n. 101 del.

- Zeng, X.; Kociolek, A.M.; Khan, M.I.; Milosavljevic, S.; Bath, B.; Trask, C. Whole body vibration exposure patterns in Canadian prairie farmers. Ergonomics 2017, 60, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Dennerlein, J.; Johnson, P. The effect of a multi-axis suspension on whole body vibration exposures and physical stress in the neck and low back in agricultural tractor applications. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 2631-1:1997/Amd 1:2010; Mechanical Vibration and Shock. Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration. Part 1: General Requirements. Amendment 1. Technical Committee: ISO/TC 108/SC 4. International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- Park, M.-S.; Fukuda, T.; Kim, T.-G.; Maeda, S. Health Risk Evaluation of Whole-body Vibration by ISO 2631-5 and ISO 2631-1 for Operators of Agricultural Tractors and Recreational Vehicles. Ind. Health 2013, 51, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Samuel, S.; Dhabi, Y.K.; Singh, H. Whole-body vibration: Characterization of seat-to-head transmissibility for agricultural tractor drivers during loader operation. Smart Agric. Technol. 2023, 4, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nawayseh, N.; Doyon-Poulin, P.; Milosavljevic, S.; Dewangan, K.N.; Kumar, Y.; Samuel, S. Comparative analysis of classical and ensemble models for predicting whole body vibration induced lumbar spine stress. A case study of agricultural tractor operators. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2025, 108, 103775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, J.; Stiles, M.; Whyte, R. Whole body vibration during tractor driving. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 1995, 14, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunribido, O.O.; Magnusson, M.; Pope, M.H. Low back pain in drivers: The relative role of whole body vibration, posture and manual materials handling. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 298, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G.S.; Mansfield, N.J. Evaluation of reaction time performance and subjective workload during whole-body vibration exposure while seated in upright and twisted postures with and without armrests. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2008, 38, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, S.K.; Trask, C.; Khan, M.; Boden, C.; Bath, B. Association between whole-body vibration and low-back disorders in farmers: A scoping review. J. Agromedicine 2018, 23, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENAMA. Agricultural Machinery Functional and Safety Testing Service. In Test Protocol n. 03 rev. 2–Soil Tillage Machines; ENAMA: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pochi, D.; Fornaciari, L.; Vassalini, G.; Grilli, R.; Fanigliulo, R. Levels of whole-body vibrations transmitted to the driver of a tractor equipped with self-levelling cab during soil primary tillage. AgriEngineering 2022, 4, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochi, D.; Fanigliulo, R.; Grilli, R.; Fornaciari, L.; Bisaglia, C.; Cutini, M.; Brambilla, M.; Sagliano, A.; Capuzzi, L.; Palmieri, F.; et al. Design and assessment of a test rig for hydrodynamic tests on hydraulic fluids. In Innovative Biosystems Engineering for Sustainable Agriculture, Forestry and Food Production; “Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering” Book Series; Coppola, A., Di Renzo, G.C., Altieri, G., D’Antonio, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 67, pp. 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugolini, L.; Matteo, R.; Lazzeri, L.; Malaguti, L.; Folegatti, L.; Bondioli, P.; Pochi, D.; Grilli, R.; Fornaciari, L.; Benigni, S.; et al. Technical performance and chemical-physical property assessment of safflower oil tested in an experimental hydraulic test rig. Lubricants 2023, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tessier, S.; Rouffignat, J. Soil bulk density estimation for tillage system and soil textures. Trans. ASAE 1998, 41, 1601–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASABE 843-844; S313.3 (R2013): Soil Cone Penetrometer. ASAE Standards; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 1999.

- Raper, R.L. Force requirements and soil disruption of straight and bentleg subsoilers for conservation tillage system. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2005, 21, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obour, P.B.; Schjønnong, P.; Peng, Y.; Munkholm, L.J. Subsoil compaction assessed by visual evaluation and laboratory methods. Soil Till. Res. 2017, 173, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, R.; Anken, T.; Hilfiker, T.; Sartori, L.; Bollhalder, H. Comparison of methods for determining cloddiness in seedbed preparation. Soil Till. Res. 1998, 45, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römkens, M.J.M.; Wang, J.Y.; Darden, R.W. A laser microreliefmeter. Trans. ASAE 1988, 31, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anken, T.; Hilfiker, T.; Bollhalder, H.; Sandri, R.; Sartori, L. Digital image analysis and profile meter for defining seedbed fineness. Agrarforsch. Schweiz 1997, 4, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Suhaibani, S.A.; Al-Janobi, A.A.; Al-Majhadi, Y.N. Development and evaluation of tractors and tillage implements instrumentation system. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2010, 3, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Verma, A.; Singh, M.; Kaur, P. Multi-sensor data fusion for precise measurement of a tractor implement performance in the field. Curr. Sci. 2023, 124, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8041-1:2017; Human Response to Vibration—Measuring Instrumentation—Part 1: General Purpose Vibration Meters. International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997.

- ISO 16063-1:1998/Amd 1:2016; Methods for the Calibration of Vibration and Shock Transducers—Part 1: Basic Concepts. International Organisation for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Nguyen, V.N.; Inaba, S. Effects of tire inflation pressure and tractor velocity on dynamic wheel load and rear axle vibrations. J. Terramech. 2011, 48, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaciari, L.; Vassalini, G.; Pochi, D.; Grilli, R.; Benigni, S.; Fanigliulo, R. Evaluation of the Acceleration Transmitted to the Tractor Driver’s Whole-Body During Agricultural Operations at Different Tire Inflation Pressures. In Biosystem Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change; “Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering” Book Series; Sartori, L., Tarolli, P., Guerrini, L., Zuecco, G., Pezzuolo, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 586, pp. 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochi, D.; Fanigliulo, R.; Fornaciari, L.; Vassalini, G.; Fedrizzi, M.; Brannetti, G.; Cervellini, C. Levels of vibration transmitted to the operator of the tractor equipped with front axle suspension. J. Agric. Eng. 2013, 44, e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deboli, R.; Calvo, A.; Preti, C. Whole-body vibration: Measurement of horizontal and vertical transmissibility of an agricultural tractor seat. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 58, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, J.; D’Ambrogio, W.; Fregolent, A. Analysis of the vibrations of operators’ seats in agricultural machinery using dynamic substructuring. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, S.; Greco, C.; Catania, P.; Orlando, S.; Vallone, M. A smart integrated system in tractor seats for alerting operators to high vibration exposure. In Biosystems Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change; “Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering” Book Series; Sartori, L., Tarolli, P., Guerrini, L., Zuecco, G., Pezzuolo, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 586, pp. 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.