Abstract

The growing threat posed by climate change and extreme weather events necessitates the adoption of advanced solutions for crop protection, such as agrotextile nets. The use of anti-rain (AR) and anti-insect (AI) nets is essential to safeguard production, but their effectiveness varies significantly. AR nets offer rain protection but can compromise ventilation, while AI nets ensure a better microclimate but offer poor resistance to precipitation. Given the lack of a standardized index, this study aims to use the rainwater permeability index (Φrw) to provide an objective parameter for evaluating and comparing the performance of different agrotextiles. Laboratory tests were conducted on eight different nets (three AR and five AI) using a rainfall simulator. The Φrw index, defined as the ratio between the mass of water passing through the net and the total mass of water applied, was evaluated as a function of rainfall intensity (39, 80, and 170 mm/h), net inclination (10°, 20°, and 30°), and the orientation of the warp relative to the slope. The results confirmed that AR nets are most suitable in protecting crops from extreme rainfall, because it becomes clear that AI nets are much more permeable than AR nets. In this sense, the plots show that AI nets usually have a higher permeability than AR nets, between 15% and 25%, depending on rainfall intensity and net inclination. In fact, the AR1 net showed the best performance, with Φrw values stabilizing between 40% and 50% under the most common installation conditions. Conversely, AI nets generally exceed 60% permeability, with the AI1 net reaching Φrw above 90%, confirming their inadequacy for rain protection alone. In general, AR nets show Φrw between 33% and 92%, while Φrw for AI nets ranges from 45% and 98%. The research allowed for the comparison of eight agricultural nets with different characteristics and the identification of those that perform best in terms of protection against three different levels of rainfall intensity. The introduction of the Φrw index constitutes a significant contribution, providing a quantifiable standard for the selection of agrotextiles in terms of protection from rainfall, regardless of manufacturers’ claims. The data obtained underscore the need to develop future hybrid and multifunctional nets capable of balancing the low water permeability of AR nets with the high ventilation and insect protection of AI nets, thereby ensuring an optimal microclimate and comprehensive crop protection.

1. Introduction

Crop protection nets are increasingly used around the world, particularly for orchards in Mediterranean countries, because of climate change, which is placing ever greater stress on fruit production [1,2,3]. In addition to preserving crops, their use helps to maintain the quality and quantity of agricultural production by addressing the threats posed by rising temperatures and extreme weather events, which compromise productivity and the ability to meet global food needs [4,5,6,7,8]. Added to this is the increase in new species of harmful insects, a phenomenon linked to globalization and climate change itself, which has pushed the field into a new era in the use of agrotextiles. In fact, the use of agricultural nets is, in many cases, replacing or integrating the use of traditional plant protection products, especially in contexts such as organic farming, to improve production performance [9,10,11]. The market offers a wide range of nets, which, depending on their structural characteristics, weight, porosity, etc., perform different functions and are used for different tasks [12,13]. Currently, these devices, used to prevent damage caused by insects or particularly intense weather events, are playing a fundamental role in crop protection systems.

Anti-rain and anti-insect nets are essential tools in modern agriculture for safeguarding crops from an increasingly hostile environment. Newly designed nets, which have recently available on the market, are used to protect against heavy rainfall. Although essential for preventing damage from extreme precipitation, these nets can reduce ventilation and increase relative air humidity, creating ideal conditions for the development of plant diseases [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Insect nets, which constitute a multifunctional and versatile defense system, are capable of effectively blocking a wide range of pests and aphids, drastically reducing the need for insecticide treatments. This approach not only minimizes environmental impact but also promotes organic production and reduces chemical residues in fruit. Therefore, the possible integration of insect nets with other technologies, such as rain nets, emerges as a key strategy for comprehensively addressing climatic and pest challenges, optimizing protection and ensuring long-term crop quality [24,25,26].

Currently, nets are used to cover greenhouses and screen houses, often limiting ventilation and solar radiation and failing to effectively prevent hail damage and the penetration of rain precipitation. In the latter case, for open field crops, this can cause serious damage to those that are most sensitive to moisture, such as thin-skinned fruits, leading to fruit rot and compromising the microclimate essential for their growth. Recent advancements in protected cultivation have addressed the optimization of insect-proof and shade nets to improve crop microenvironments and resilience to climate change [2,27]. However, traditional solutions often present trade-offs: thinner fibers may weaken mechanical resistance, while optical additives can lead to excessive shading [2,28]. A critical challenge remains the protection of horticultural crops from high-intensity precipitation, which causes irreversible damage such as fruit cracking and increased pathogen susceptibility [29]. While chemical treatments and impermeable plastic films are common mitigation strategies, they often result in poor ventilation, increased relative humidity, and potential chemical residues [30,31]. Consequently, there is a growing need for innovative technical solutions that provide effective rainfall protection while maintaining optimal gas exchange and fruit quality. Multifunctional agricultural nets are increasingly recognized as essential instruments for bolstering crop resilience. These systems provide superior ventilation rates compared to conventional plastic films, thereby allowing growers to significantly reduce the application of phytosanitary products. Recently, the market introduction of innovative anti-rain nets has catalyzed scientific interest in assessing their efficacy as a primary mitigation strategy against rainfall-induced damage in agriculture. Such specialized netting systems offer a promising solution for shielding crops from the adverse impacts of precipitation, with particular potential for high-value fruit crops—including cherries, kiwis, grapevines, and various berries—that exhibit high vulnerability to rain-related physiological disorders and mechanical injuries [32].

The domain of agricultural nets has a considerable body of work, predominantly focused on their mechanical behavior under stress and their influence on the radiative and aerodynamic microclimate. However, while the mechanical properties and shading effects are well-documented, the hydraulic response—specifically how these textures interact with rainfall—remains less explored. This study positions its contribution by transitioning from purely structural or climatic analysis to a functional hydraulic evaluation, addressing the gap between the known porosity of nets and their actual water-shielding efficiency.

Despite their importance, there is no universally recognized index for classifying nets according to their rain protection performance. Current evaluation methods for water–material interaction are primarily standardized for the textile and civil engineering sectors. For instance, tests for hydrostatic head or water vapor permeability focus on waterproof or semi-permeable membranes. However, these methods fail to capture the complexity of agricultural net performance, where the interaction between falling raindrops and the mesh structure is influenced by the kinetic energy of the rain and the mechanical installation of the net (e.g., slope and tension). Previous studies on agricultural nets have often reported qualitative observations or fragmented data on water retention, lacking a unified and comparable metric. The introduction of the rainwater permeability index (Φrw) represents an innovation in this field, as it offers a standardized, dimensionless quantitative measure. This index allows for a direct comparison of different net technologies (AR vs. AI) and provides a practical tool for growers and engineers to predict water-shielding efficiency under diverse climatic scenarios.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the Φrw index, which can be used to compare the performance of the tested nets, thus providing a standard for comparing agrotextiles. Furthermore, the characterization of Φrw is crucial in enabling farmers to make more informed choices when selecting the most suitable material for crop protection, whether the net is used alone or in combination with other types of nets.

For this purpose, tests were carried out at the Polytechnic University of Bari to evaluate the Φrw of eight agricultural nets, three classified as anti-rain and five with an anti-insect function, to compare their ability to protect crops from the adverse effects of exposure to precipitation.

Based on the results obtained, this study stresses the need to develop hybrid solutions geared towards using the most suitable net for the specific needs of the various crops. The challenge for future research is to develop multifunctional nets that combine the best properties of anti-rain and anti-insect nets, ensuring effective protection against both risks without compromising plant health [33,34]. This will make it possible to create more efficient nets that protect crops from adverse weather conditions and help maintain an optimal microclimate. Scientific research in this field is therefore crucial to enable agriculture to adapt to new environmental challenges and ensure food security.

In conclusion, this research focuses on advancing the understanding of the structural and functional properties of agrotextiles, specifically examining their rain-sheltering efficiency to facilitate the implementation of superior and sustainable cultivation techniques. The primary goals include assessing the water permeability of nets designed for rainfall management and pest control, exploring their efficiency across diverse operational scenarios, and identifying how geometric configurations impact their overall performance. Special attention was given to evaluating how the inclination angle relative to the horizontal plane affects the hydraulic response of these materials. Such analysis seeks to establish a framework for designing next-generation agricultural covering systems tailored to specific agronomic needs and climatic variables. Ultimately, this experimental work provides a scientific foundation for the development of technical guidelines, promoting the use of specialized agrotextiles as a strategic response to the challenges posed by global climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Nets’ Features

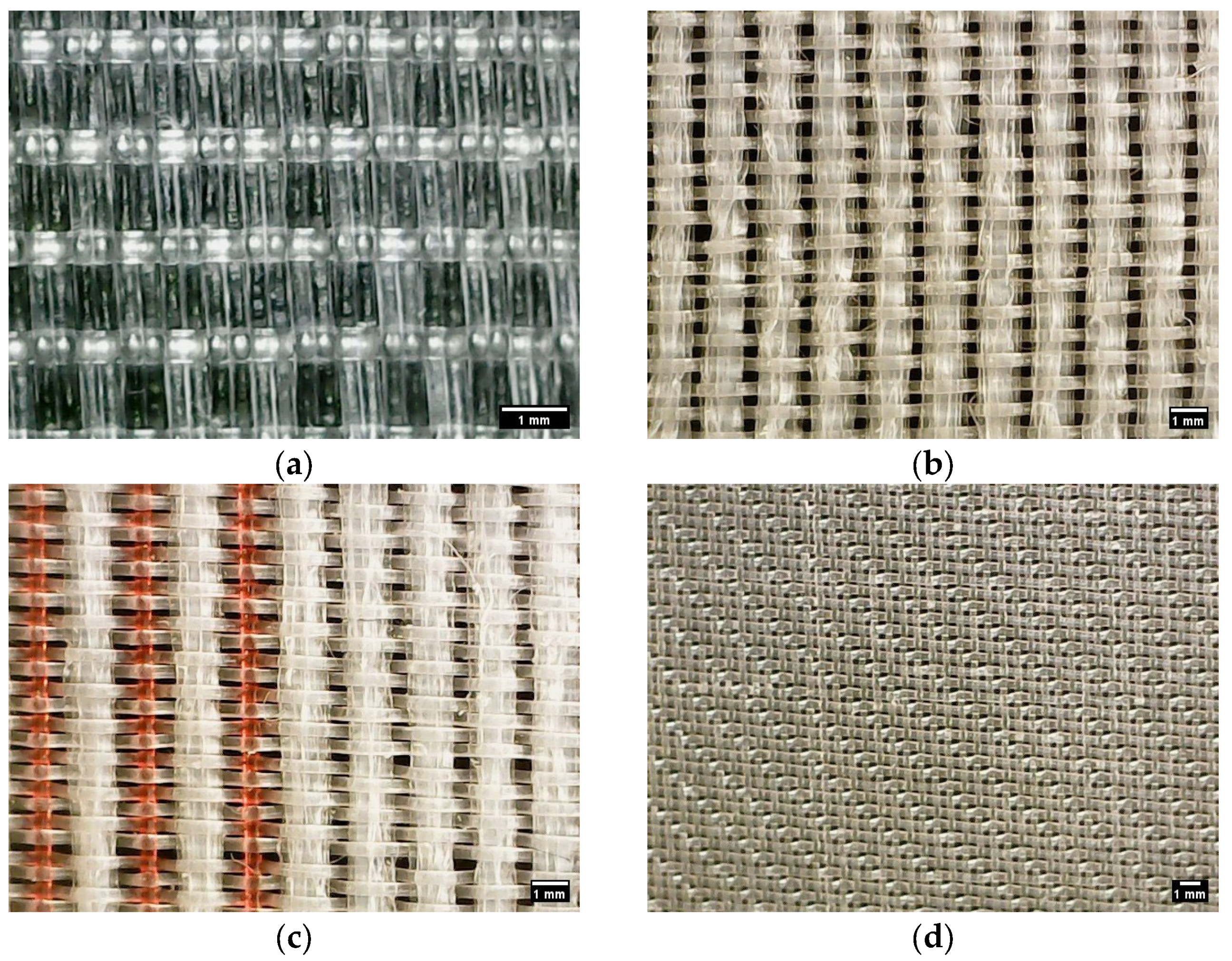

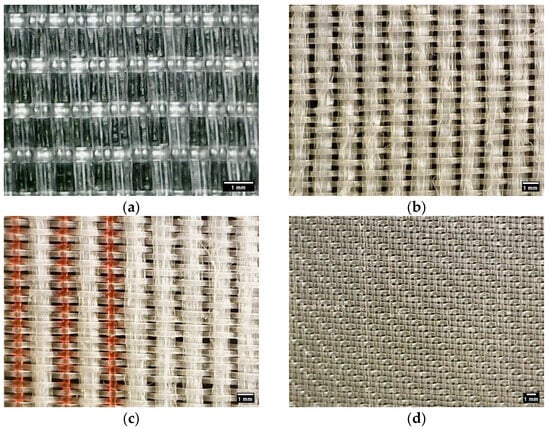

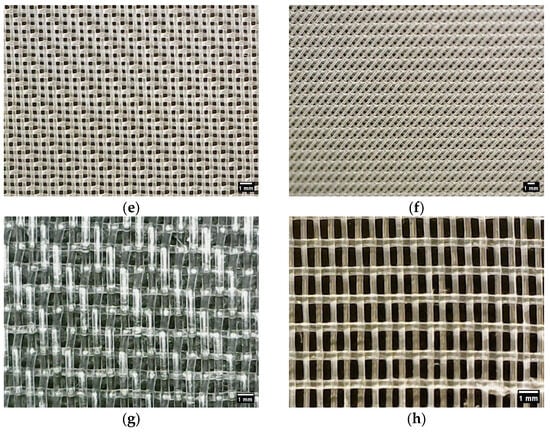

For the aims of this research, eight different types of nets (Figure 1) were tested, three anti-rain (AR) nets and five anti-insect (AI) nets. Rain protection nets are designed to limit the impact of heavy rain and hail on crops by reducing water percolation and increasing surface runoff [14,15,16]. The structural characteristics, weave and weight, which facilitate the deflection of water flow, are key elements in limiting rainfall permeability [23], thanks to a denser mesh than that of anti-insect nets. Insect nets are designed to prevent insects from damaging crops [35,36,37]. Their meshes come in different sizes depending on the type of insect to be controlled, with smaller meshes for aphids and thrips (0.2–0.4 mm nominal openings) and larger meshes for beetles and Lepidoptera (0.8–7.0 mm nominal openings) [38]. Unlike anti-rain nets, their main feature is their high porosity, which ensures better ventilation compared to anti-rain nets, minimizing microclimate alteration [9].

Figure 1.

Tested nets (magnification 40×): (a) AR1; (b) AR2; (c) AR3; (d) AI1; (e) AI2; (f) AI3; (g) AI4; (h) AI5.

Table 1 lists the main characteristics of the eight nets tested made of HDPE and neutral in color. The technical specifications and structural parameters of the nets were retrieved from the research of Mastronardi et al., 2025 [39] to ensure consistency with previously validated measurements.

Table 1.

Characteristics of tested nets.

Conversely, Table 2 contains the methodologies used to determine the characteristics of the nets tested.

Table 2.

Methods for determining the characteristics of the tested nets.

The porosity of the nets was determined using an image analysis approach [39,40,41]. Samples were acquired with a flatbed scanner at a resolution of 2400 dpi, which was previously calibrated using a precision grid (mm) to ensure dimensional accuracy. Image processing was performed via Adobe Photoshop (v. 2021), employing a binarization protocol with a neutral gray threshold (value 128) to differentiate the net structure (black) from the voids (white). Porosity was calculated as the percentage of white pixels relative to the total area within representative cm regions. The final value was calculated as the means of at least three measurements per sample. Observed parameters, including pore size and fiber thickness, showed high correlation with the manufacturers’ specifications and established reference data.

The thickness and/or diameter of the threads was measured in Mastronardi et al., 2025 [39] using a digital micrometer (Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan; model 293–240, Absolute Digimatic), with a resolution of 0.001 mm (range 0–25 mm). A ratchet clamp was used to ensure repeatable measurements by applying constant contact pressure (measuring force 5–10 N, according to the manufacturer’s specifications). For each material, five measurements were taken at different points on the sample, avoiding edges and deformed areas. The device was checked and zeroed before use.

The AR1 net is a multi-purpose shield capable of protecting crops from rain, hail, wind, and insects. It is a flat, extremely dense mesh net with very low porosity. The weft yarn has a rhomboidal shape, with a major diagonal of 0.49 mm and a minor diagonal of 0.28 mm.

The AR2 and AR3 nets represent the evolution of rain and insect nets. They feature a flat weave, using round HDPE monofilaments and fibrillated raffia tape in a neutral color. They are not waterproof, but are capable of blocking smaller raindrops. These nets are mainly used to protect the most delicate fruits, which are prone to cracking due to excessive wetness, as well as providing protection against hail, frost, and wind. Both nets have a dense mesh; its greater water resistance and the presence of red and neutral bands measuring 3.8 cm every 24.2 cm (a mix of 4.7 fibrillated bands/cm alternating with 4.7 red weft threads) distinguish the AR3 net.

The AI nets are designed to offer targeted protection against pests while ensuring the best possible airflow.

The AI1 and AI4 nets are flat fabric barriers specifically designed to protect against thrips. Because of their design, they have extremely small holes and are highly efficient due to their very thin, high-tenacity yarn. As a result, more holes per square meter can be created while maintaining the standard pore size, determining greater porosity. In addition, the use of a greater number of yarns gives the nets a more stable, uniform, and robust structure. Of the two nets, the AI1 net is the narrower of the two, with smaller meshes and holes than the AI4.

The AI2 and AI3 nets are also insect nets characterized by a flat weave. They are made with small diameter fibers to exclude even the smallest insects. These nets help to maintain a cooler and less humid climate inside greenhouses. They are produced with round monofilaments for warp and weft.

The AI5 net is a model widely used in agriculture to protect crops from the smallest categories of insects, such as aphids. It is a net with a standard flat weave and round monofilaments, characterized by about 20 weft threads and about 10 weft threads per centimeter.

The flat weave structure, particularly when combined with high mesh density as seen in the AR1 net (porosity of 7%), acts as a continuous physical barrier that facilitates the coalescence of raindrops into a surface water film. This geometry promotes surface runoff rather than individual droplet percolation, a mechanism that is significantly more effective at reducing rainwater permeability compared to the typically open and irregular gaps found in knitted or leno weave structures.

2.2. Test Protocol

To assess the water permeability of the nets, laboratory tests were carried out at the Hydraulic Models Laboratory of the Department of Civil, Environmental, Land, Construction and Chemistry (DICATECh) at the Polytechnic University of Bari, using a rainfall simulator capable of reproducing field conditions with an appropriate scale factor. The rain simulator is a tower structure approximately 5 m high, with a base measuring 1.20 m × 1.00 m, built with iron angle profiles to ensure stability. The net samples, measuring 1.00 m × 1.00 m, are assembled in metal frames and installed 1.25 m above the floor with variable inclinations of 10°, 20°, and 30°, chosen to simulate typical field conditions, based on the manufacturers’ recommendations, and with the consideration of the preferred installation methods [13]. To minimize edge effects at the frame–net interface, the water collection system was positioned centrally beneath the net samples, leaving a safety margin from the metal frame. The nets were firmly tensioned on the frame to prevent any sagging or water pooling that could artificially alter the flow paths. Furthermore, the frame design ensured that runoff water could flow freely into the collection gutter without being obstructed or redirected by the metal supports, thus ensuring that the measured Φrw reflects only the intrinsic permeability of the mesh. At the top of the tower, approximately 3.75 m from the net, there are 24 dynamic 360° micro-sprinklers with a maximum flow rate of 130 L/h and a radius of 4.50 m, hydraulically powered by a tank to ensure constant flow without pressure fluctuations. The device is completed by a pressure gauge (Spriano, Milan, Italy) with a scale between 0 and 4 kg/cm2, installed on the supply pipe, to vary the pressure and thus simulate different rainfall intensities [42].

The objective was to measure the precipitation passing through the net and that flowing over the surface of the net. The permeated water is collected in a tank measuring 1.00 m × 1.00 m; the runoff water is collected in a smaller separate tank, measuring 0.20 m × 1.00 m, positioned in a cantilevered position. The spatial uniformity of the simulated rainfall over the 1.00 m × 1.00 m test area was achieved by optimizing the pressure at the nozzles and ensuring adequate overlap of the spray patterns at the specific working height, thus minimizing spatial bias in the permeation measurements.

The laboratory test conditions were strictly controlled using a rain simulator with predefined rainfall intensity to separate and measure a specific technical index (Φrw) for water permeability. In contrast, the real-world (open field) test environment exposes the nets to dynamic and unpredictable climatic variables, such as strong winds and extreme rainfall, which were not considered in this study except for in the variations in rainfall intensity, where typical values for the Mediterranean area were assumed with the final aim of verifying the agronomic effectiveness in protecting crops and mitigating physiological disorders.

The main objective of the experiment was to evaluate the Φrw parameter [42], taken as a reference to describe the reaction of each net under simulated precipitation and to compare the different types of agrotextiles tested. The tests were carried out under controlled environmental conditions:

- Absence of direct solar radiation;

- Ambient temperature between 26 °C and 28 °C;

- Ambient relative humidity varying between 50% and 70%.

According to Martellotta et al. (2025) [42], to ensure the reliability of the results, each test was repeated three times for each rainfall intensity value, always with reference to a duration of 10 min, to ensure reproducibility. After the three repetitions of the measurements with varying rainfall intensity and with fixed net inclination and installation direction, the tested nets were replaced with new pieces of the same dimensions as indicated above. The final value of the Φrw parameter was calculated as the average of the results, considering only steady-state conditions, i.e., discarding the first five minutes of rainfall, using Equation (1). Conversely, using Equation (2), it was also possible to evaluate the quantity of water R that flows over the network.

where

Φrw is the rainwater permeability index [%];

MPB is the mass of the bin containing the total mass of water passing through the net [kg];

MB1 is the mass of the empty bin collecting the permeated water [kg];

TM is the total water mass [kg];

R is the net runoff water [%];

MRB is the mass of the bin containing the total runoff water mass [kg];

MB2 is the mass of the empty bin collecting the runoff water [kg].

Each test involved a preliminary 5 min stabilization period, which was excluded from data collection. This interval was established during the calibration phase to ensure that the hydraulic system reached a constant operating pressure and flow rate and that the net reached full saturation, overcoming the initial transient phase of water retention due to surface tension. Following this stabilization, the permeated and runoff water were collected for a continuous 10 min period, representing the steady-state performance of the net. The tests were performed on a unit area by varying the inclination of the net (10°, 20°, and 30°), the orientation of the warp in relation to the slope (perpendicular and parallel), and the pressure applied (0.04 MPa, 0.08 MPa, and 0.11 MPa), corresponding to three different rainfall intensity values: the minimum pressure corresponds to the maximum rainfall intensity of approximately 170 mm/h, the average pressure corresponds to the minimum rainfall intensity of approximately 39 mm/h, and finally, the maximum pressure corresponds to an average rainfall intensity of approximately 80 mm/h. It should be noted that the rainfall intensity was determined based on the actual water volume collected within the 1 × 1 m collection tank during each test. Although higher nozzle pressures generally correspond to higher flow rates, the observed rainfall intensity values (39, 80, and 170 mm/h) were influenced by the spray pattern and the effective fraction of water intercepting the test area. Consequently, the relationship between nominal nozzle pressure and the calculated rainfall intensity reflects the specific experimental setup and the spatial distribution of the simulated rainfall rather than a direct hydraulic correlation. The choice of these pressure values is based on the rainfall values identified, which range from 10 mm to 23 mm for a rainfall duration of 10 min; this range includes the rainfall value that characterizes the area of southern Italy for the same duration of 10 min, equal to approximately 16 mm [43].

To assess the statistical significance of the differences in Φrw values under different nets and conditions, Student’s t-test was performed [44]. The statistical analysis was carried out using R studio software v. 4.3.1 (Copyright (C) 2023 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The inclination angle affects Φrw by modifying the effective opening area of the mesh relative to the vertical trajectory of the raindrops. As the inclination increases, the projected geometry of the pores changes, and the gravitational component promoting runoff along the net surface increases. In this study, Φrw is calculated specifically for each combination of rainfall intensity and inclination angle, thereby inherently incorporating the dynamic interaction between the net’s orientation and the partitioning of water between permeation and runoff.

The observed variability between replicates was consistently low, with standard deviations generally remaining below 5% of the mean values. To further account for experimental uncertainty and to strengthen the reliability of the results, a bootstrap resampling technique with 1000 iterations was applied to the collected data, as detailed in the statistical analysis section.

The laboratory protocol and the measurement window were defined to align with established principles of polymer and textile characterization, ensuring the reliability and repeatability of the Φrw index. Following classical approaches in material testing, each test was conducted over a 10 min duration, discharging the first 5 min of rainfall to ensure steady-state conditions. This 5 min induction period is essential to overcome initial transient phenomena, such as the surface wettability of HDPE fibers and the stabilization of the water film across the net’s porous matrix, which could otherwise introduce noise in the permeability measurements. This methodological choice reflects the rigor found in specialized literature for porous polymers [45,46], which emphasizes the importance of thermal and hygrometric stability—strictly maintained here between 26 and 28 °C and 50–70% relative humidity—to prevent structural alterations in the extruded monofilaments during testing. The use of three repetitions for each condition further ensures that the results are statistically robust and representative of the material’s physical behavior.

The Φrw parameter is an essential analytical tool used to study the interaction between agricultural nets and the rainfall that impacts them, thus quantifying the ability of an agrotextile to prevent rain from passing through its structure and reaching the crops and the soil below. Therefore, for the purposes of this research, the Φrw parameter is defined as a simple and direct ratio between the total amount of water falling on the net and the amount of water penetrating it, acting as an indicator of permeability: a higher value means that a greater percentage of precipitation reaches the ground, whereas a lower value indicates that the net retains or deflects most of the water. In this sense, this parameter is fundamental for evaluating the protective (or permeative) effectiveness of each net tested.

The introduction of Φrw aims to provide a standardized metric for evaluating the hydraulic performance of agricultural nets, a field currently lacking a universally recognized classification system. Unlike qualitative assessments or producer-specific data, it offers an objective and quantifiable parameter that enables a direct comparison between different agrotextiles (e.g., anti-rain vs. anti-insect nets) under identical experimental conditions.

Furthermore, the index is preferable to static alternatives as it accounts for dynamic operational variables, such as rainfall intensity, net inclination, and textile orientation. However, some inherent limitations must be acknowledged. First, the index is derived from controlled laboratory simulations, which, while highly reproducible, may not fully capture the stochastic nature of open-field environmental factors. In addition, the current definition focuses strictly on water permeability; while this is a primary factor for crop protection, it does not account for the potential microclimatic trade-offs, such as variations in hygrometric levels or air exchange rates, which remain subjects for future multi-parametric integration.

3. Results and Discussion

Comparison Among Tested Nets Based on the Rainwater Permeability Index

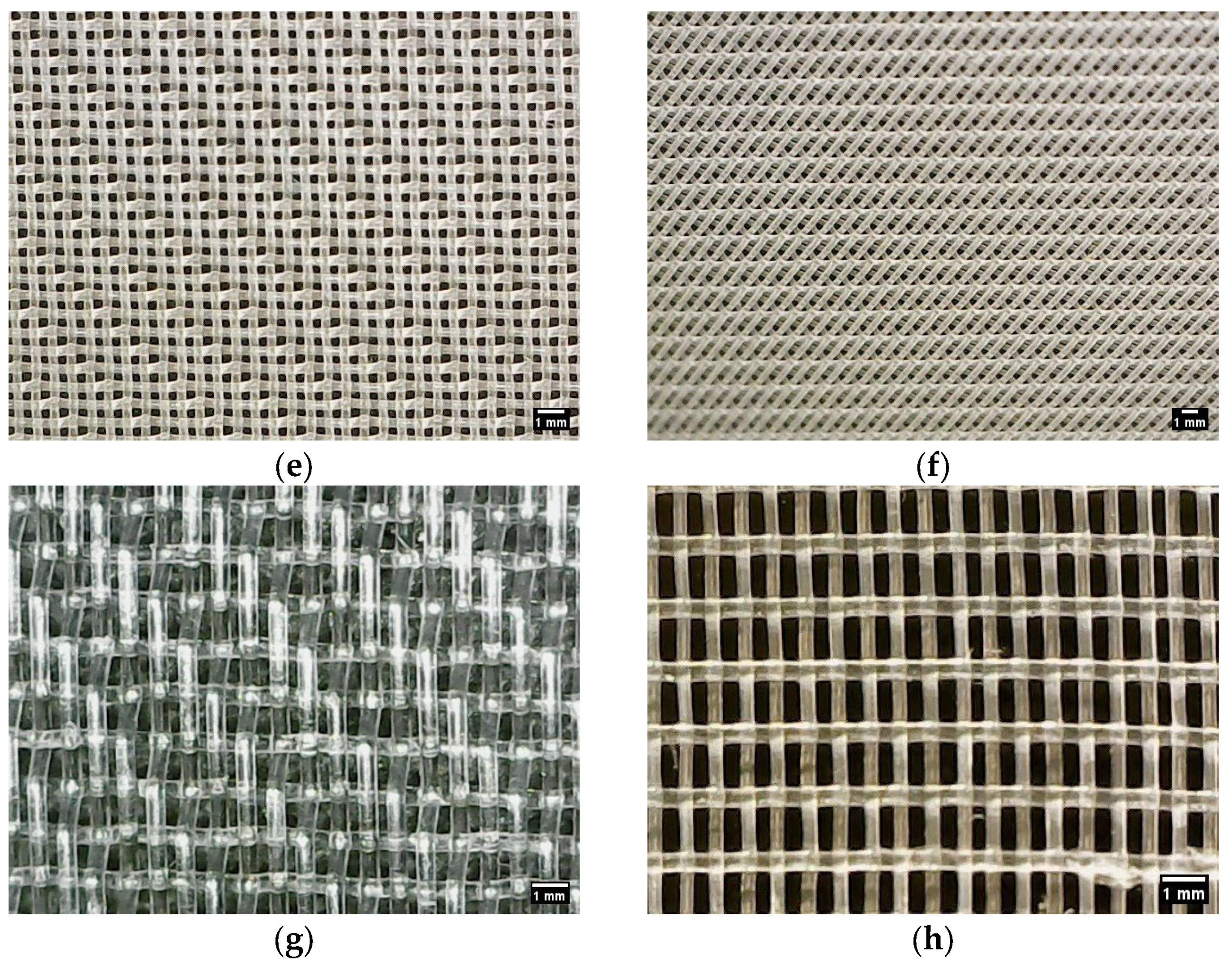

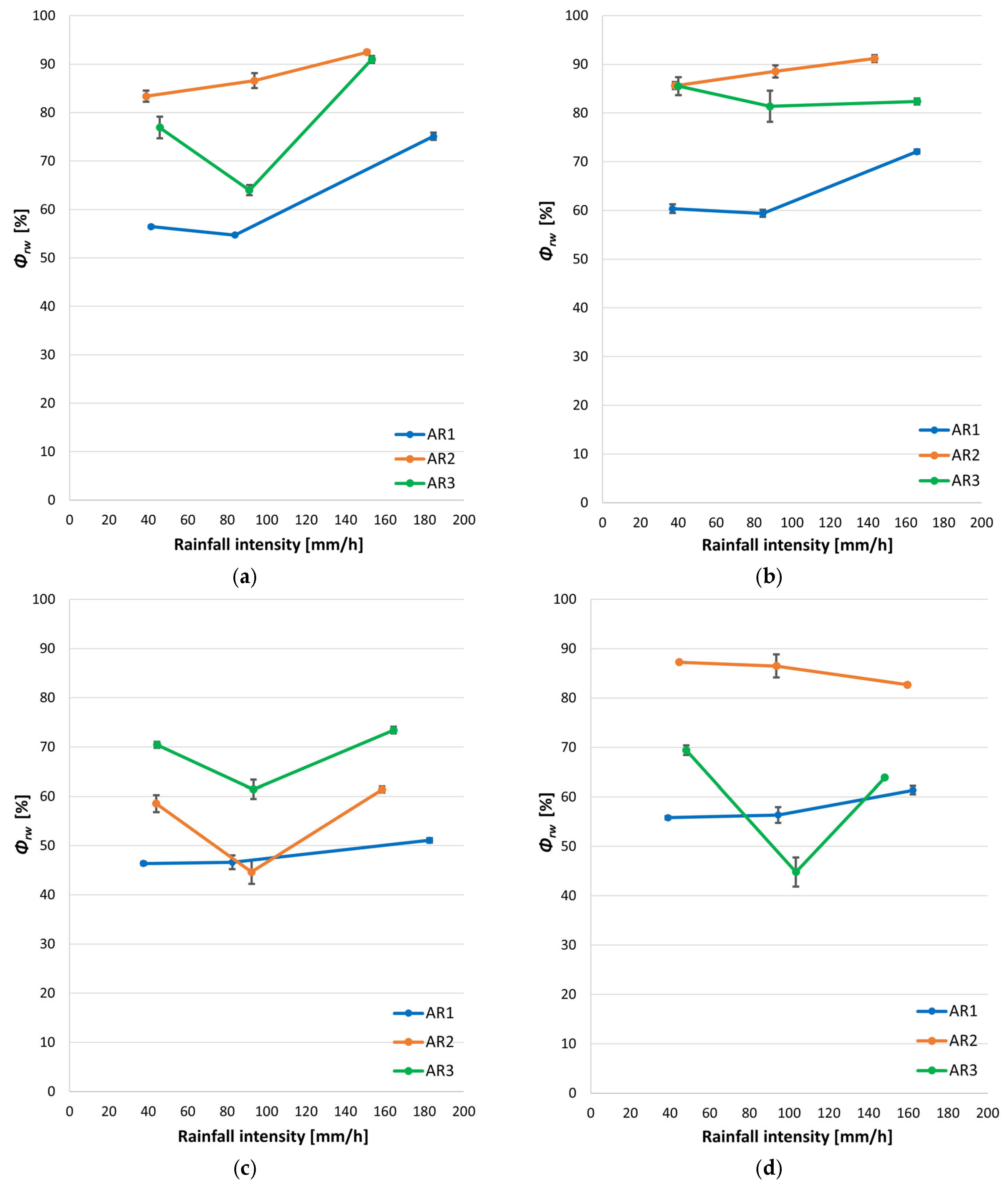

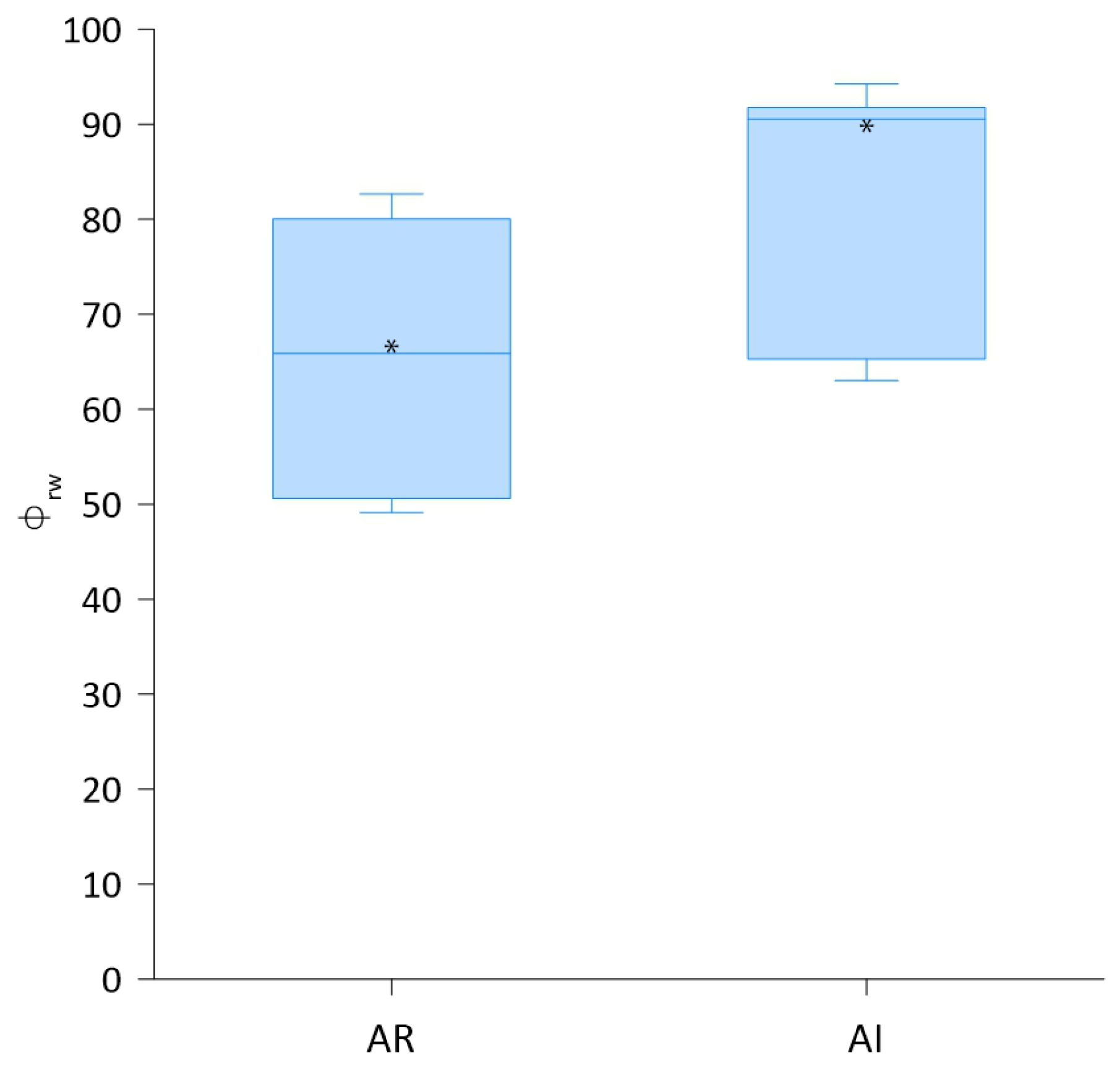

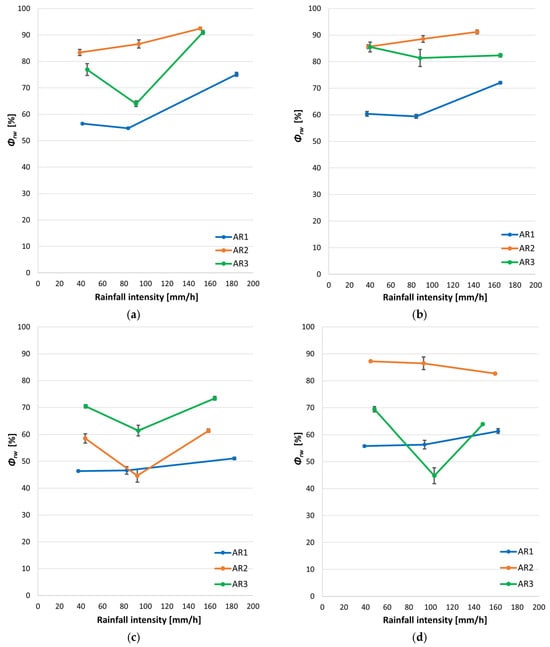

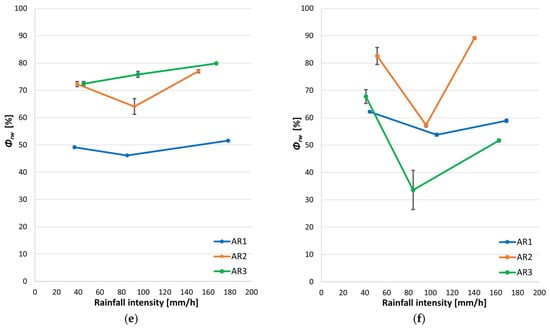

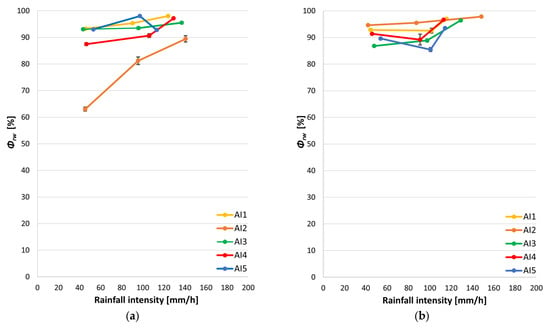

The Φrw values were determined for each of the eight nets tested using the rainfall simulator and in accordance with the procedure described in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. For each net, once the inclination and orientation of the warp relative to the slope had been set and the rainfall intensity varied, three Φrw values were determined, corresponding, respectively, to the minimum, average, and maximum rainfall intensity values (approximately 39 mm/h, 80 mm/h, and 170 mm/h). Therefore, the Φrw values were plotted as a function of the corresponding rainfall intensity, both with reference to the anti-rain nets (Figure 2) and with reference to the anti-insect nets (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Means ± standard errors (whiskers) of the Φrw values for AR1 (blue), AR2 (orange), and AR3 (green) anti-rain nets as a function of precipitation intensity: (a) 10° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (b) 10° slope and warp parallel to the slope; (c) 20° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (d) 20° slope and warp parallel to the slope; (e) 30° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (f) 30° slope and warp parallel to the slope.

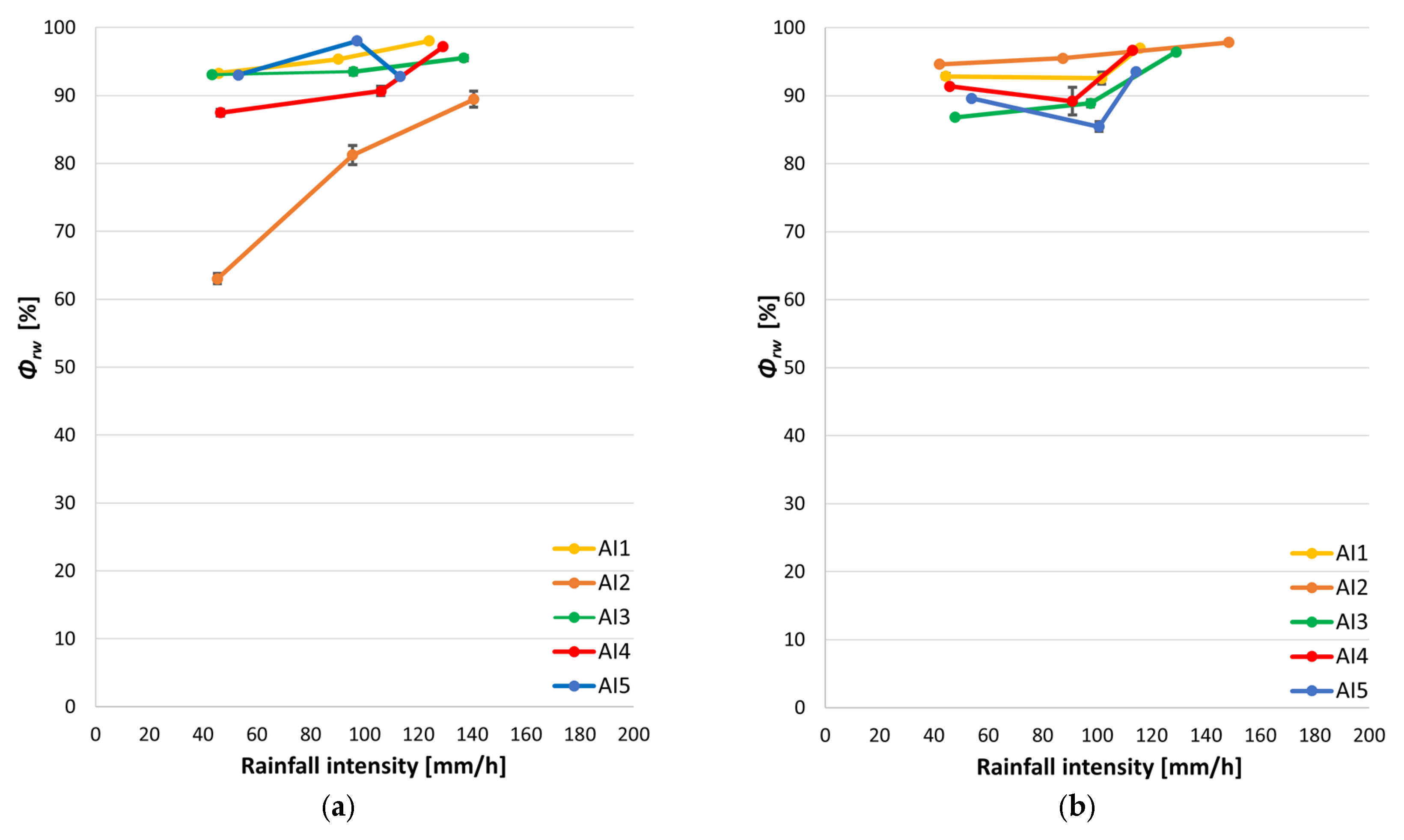

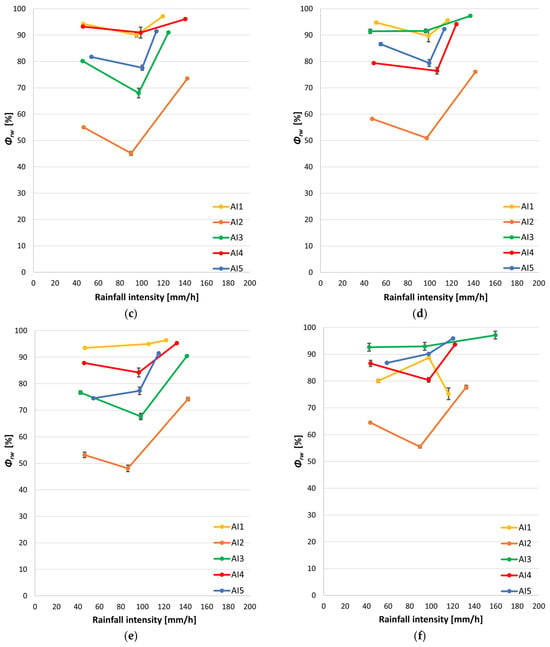

Figure 3.

Means ± standard errors (whiskers) of the Φrw values for anti-insect nets AI1 (yellow), AI2 (orange), AI3 (green), AI4 (red), and AI5 (blue) as a function of rainfall intensity: (a) 10° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (b) 10° slope and warp parallel to the slope; (c) 20° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (d) 20° slope and warp parallel to the slope; (e) 30° slope and warp perpendicular to the slope; (f) 30° slope and warp parallel to the slope.

The Φrw values for rain protection nets shown in Figure 2 highlight that, on average, the AR1 net performs best in terms of resistance to rainfall, with Φrw values for this net generally lower than those for the AR2 and AR3 nets. When the AR1 net is installed with the warp perpendicular to the slope, which is the most common installation method, the Φrw values are, with a slope of 10°, between 50% and 60% for minimum and average rainfall intensity, exceeding 70% when the rainfall intensity is approximately 170 mm/h. In this sense, the combined effect of a reduced inclination of the net with respect to the horizontal and the maximum rainfall intensity results in a greater passage of water through the mesh that makes up the AR1 net, thus correspondingly detecting a higher Φrw value. Similarly, with reference to a 20° and 30° inclination of the AR1 net with respect to the horizontal, Φrw assumes almost uniform values regardless of the rainfall intensity applied, always remaining between 40% and just above 50%, with an average tendency to increase as the rainfall intensity increases.

If the AR1 net is installed with the weft parallel to the slope, the Φrw values are always above 50%. With a slope of 10° from the horizontal, Φrw achieves between about 60% and 70%, with a low point at average rainfall and a high point when rainfall is at its strongest. With an installation characterized by a slope of 20° to the horizontal, Φrw is lowest for minimum rainfall intensity and highest when rainfall intensity is around 170 mm/h. An interesting non-linear trend was observed for the AR1 net at a 30° angle with the warp parallel. The decrease in Φrw at the intermediate intensity of 80 mm/h, compared to the values at 39 and 170 mm/h, suggests a transition in the hydraulic mechanism. This could be explained by the formation of a stable water film over the net at medium intensities, which enhances the runoff capacity of the net due to surface tension. As the intensity increases to 170 mm/h, the higher kinetic energy of the raindrops likely disrupts this film, forcing more water through the pores and thus increasing the permeability index. This threshold effect demonstrates that the protective efficiency of AR1 nets is not only a function of the mesh geometry but also of the dynamic conditions of the rainfall event. In addition, the anisotropic behavior of the AR1 net, where higher Φrw values were observed with the weft parallel to the slope, can be attributed to the specific mesh geometry. The orientation of the monofilaments influences the hydraulic resistance and the path of the water droplets.

The Φrw trends for the AR2 and AR3 nets, instead, show that their resistance to rainfall is lower than that of the AR1 net under most of the analyzed conditions, depending on the slope at which they are installed in relation to the horizontal and the direction of the warp with respect to the slope. The values measured are generally above 60%, with some exceptions generally corresponding to the average value of the applied rainfall intensity for both the AR2 and AR3 nets, in particular for the AR3 net, when the latter is installed with a slope of 20° and 30, respectively, and the warp parallel to the slope. The Φrw values are lower than those of the AR1 net when AR3 is installed at 20° and the rainfall intensity is at a medium level, and at 30° with a maximum rainfall intensity, with the warp parallel to the slope. However, in all other cases, when compared with the AR1 net, the Φrw values for the AR2 and AR3 nets are always higher, with differences up to about 60%; therefore, the performance of the AR2 and AR3 nets does not guarantee good protection against rainfall for the crops underneath.

The consistently lower Φrw values of AR1 compared to AR2 and AR3 are primarily due to its higher mesh density and lower porosity, as detailed in Table 1. Statistical analysis (Student’s t-test) confirmed that these differences are significant (p < 0.05) under most experimental conditions. However, the observed convergence in performance between AR1 and AR3 at 20–30° slopes with warp-parallel orientation can be explained by the projected geometry of the filaments, highlighting how installation parameters can sometimes equalize the performance of structurally different nets.

Figure 3 shows the Φrw values identified for the anti-insect nets as a function of rainfall intensity. In the analyzed cases, the Φrw values are almost uniform for all nets and in most cases tend to be above 60%, regardless of the precipitation intensity applied, the inclination of the net with respect to the horizontal, and the orientation of the warp with respect to the slope.

When seeking to identify the anti-insect net with the best performance in terms of rainfall resistance, Figure 3 clearly shows that the AI2 net has the lowest Φrw values, except when installed with the warp parallel to the slope and at an angle of 10° to the horizontal. In the latter condition, the AI5 net performs best, although all Φrw values exceed 80%. Again, with reference to the AI2 net, the best performance is achieved with an inclination of 20° with the warp perpendicular to the slope and an average rainfall intensity, where a Φrw value of 45% is recorded.

The worst performance in terms of rainfall resistance was found in the AI1 net, which on average showed Φrw values higher than all the other anti-insect nets examined, largely exceeding 90% and demonstrating that almost all rainfall passes through this net, meaning that it is therefore unable to offer adequate protection to crops in this regard.

Figure 2 shows that, for rain protection nets, the Φrw curves exhibit more pronounced variations with rainfall intensity and installation configuration, whereas Figure 3 highlights that, for anti-insect nets, the Φrw trends are overall more uniform across the analyzed rainfall intensity range, although differences related to the installation configuration are still observed. The balance between runoff and permeation is strongly dependent on the installation slope: for AR nets, increasing the angle from 10° to 30° systematically promotes runoff by reducing the effective pore area. Among anti-insect nets, AI2 showed the lowest Φrw due to the favorable combination of its 0.17 mm filament diameter and higher mesh density, which increases droplet interception compared to AI3 or AI5. The optimal performance of the AI2 net at a 20° slope and 80 mm/h intensity can be attributed to a hydro-dynamic equilibrium. The 20° inclination provides a sufficient gravitational component to promote laminar runoff, whereas at lower angles, water tends to accumulate and eventually drip through due to gravity overcoming surface tension. Conversely, the high permeability of AI1 (>90%) is explained by its high porosity, which allows the majority of rainfall to permeate regardless of the intensity or slope.

The superiority of the perpendicular warp orientation is attributed to the increased hydraulic resistance provided by the larger diameter filaments (0.49 mm) acting as transverse barriers, which promote film stability and runoff. Conversely, at inclinations below 20°, the reduced gravitational drainage fails to evacuate high-intensity rainfall (170 mm/h) effectively. This leads to a localized water surcharge on the mesh surface, where the hydrostatic pressure overcomes the capillary forces of the pores, significantly increasing Φrw.

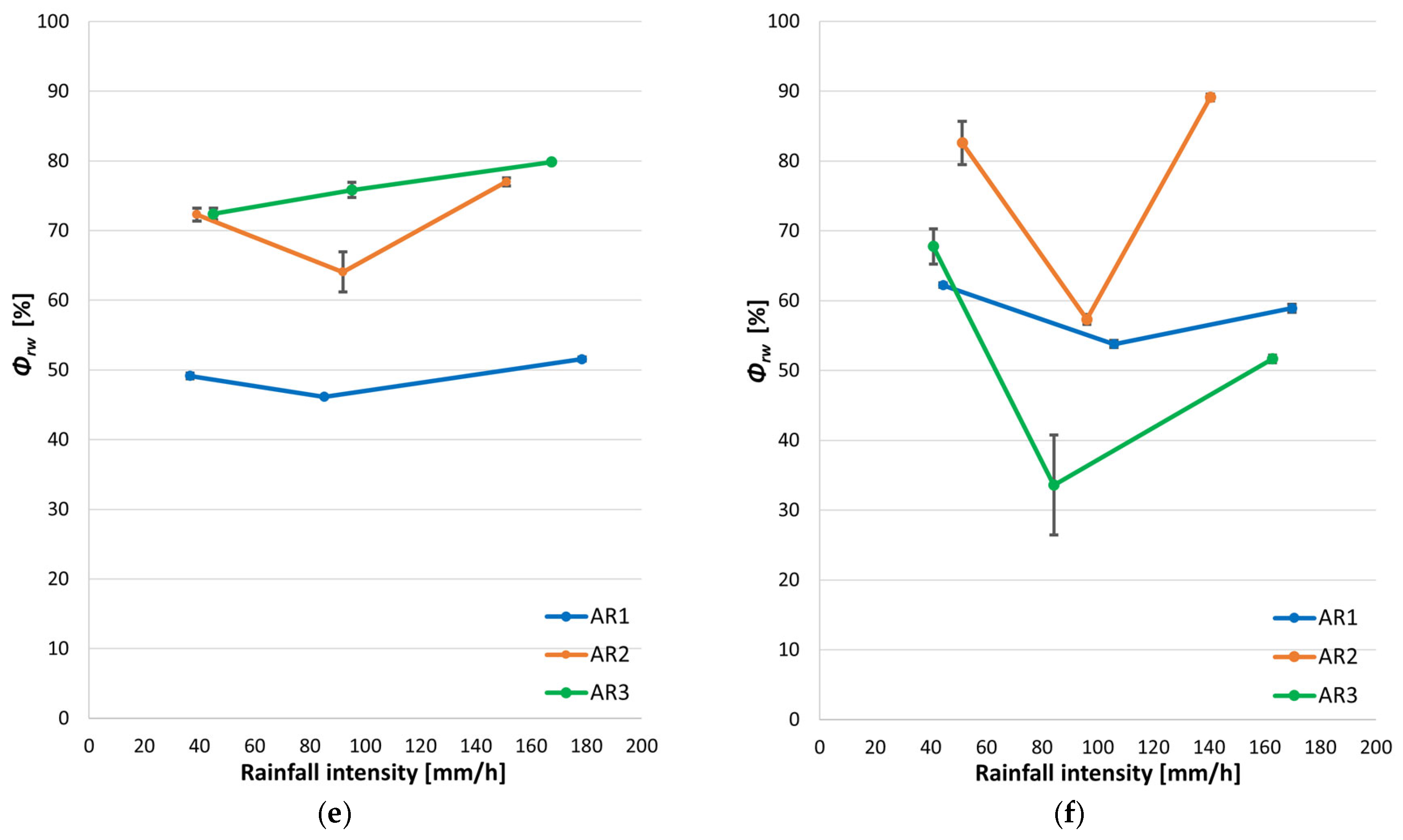

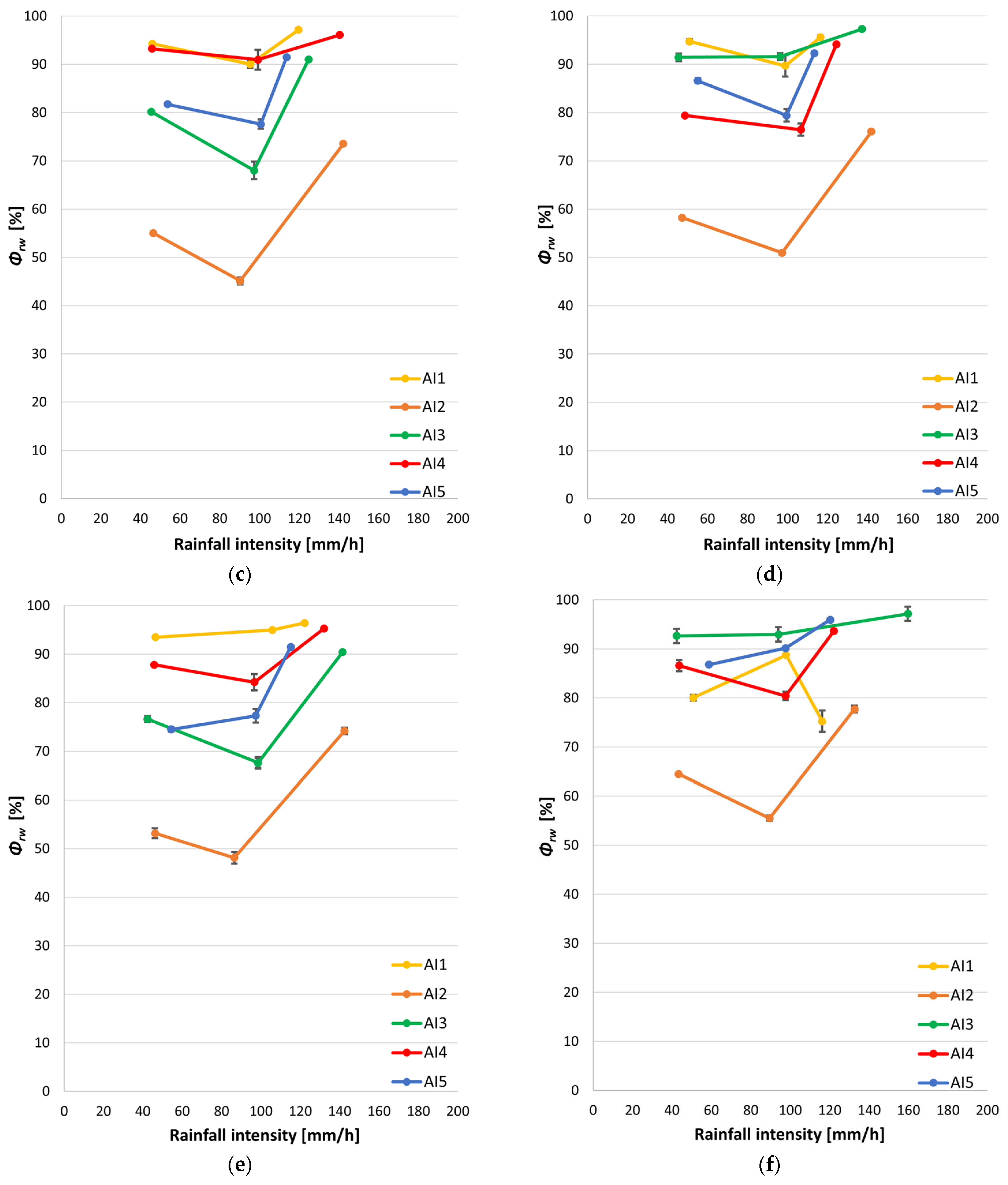

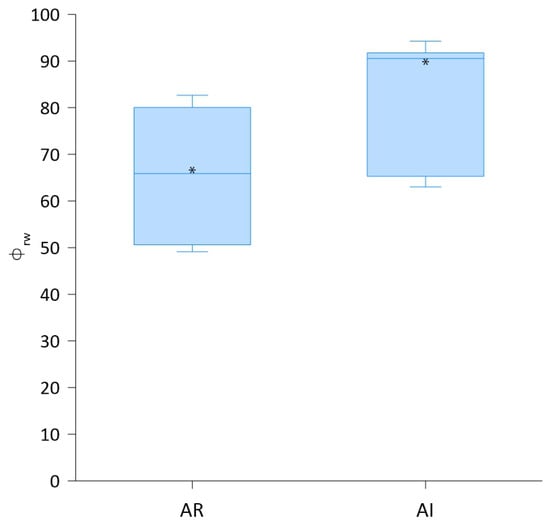

- Analysis of the variation in Φrw between anti-rain and anti-insect nets was carried out by aggregating all the data collected since rainfall intensity, net slope, and installation direction varied; this analysis shows that AI nets have, on average, a permeability that is approximately 15 percentage points higher than AR nets. To verify whether this 15% difference is statistically significant, a Student’s t-test for independent samples was applied.

The p-value from the test was lower than 0.0001, which was significantly low compared to the critical threshold of 0.05, so it is possible to state with a strong confidence level that the difference is statistically very significant (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Comparison between the range of Φrw values ± standard errors of AR and AI nets. * significance at the 0.0001 probability level (p-value < 0.05).

Therefore, the analysis demonstrates that the net type has a decisive impact on drainage or filtering capacity, with AI nets being systematically more water permeable. The internal variability within the groups (standard deviation) is low, which makes the test result very stable, and this difference stays the same no matter what the slope (10°, 20°, 30°) or installation direction (parallel or perpendicular) is.

Benchmarking our results against existing literature, the ranges identified (33% to 92% for AR nets and 45% to 98% for AI nets) reflect the functional diversity of these materials. Specifically, the AR1 net’s stabilization between 40% and 50% aligns with the operational requirements for protecting high-value crops like sweet cherries, where a drastic reduction in direct water impact is crucial. Our data suggests that the installation angle acts as a mechanical multiplier of this effect: as the inclination increases from 10° to 30°, the gravity-driven runoff speed overcomes the capillary forces that would otherwise pull droplets through the pores. This confirms that the hydraulic efficiency of a net is not an intrinsic property alone but a result of its interaction with the installation geometry, which optimizes the dissipation of the raindrops’ kinetic energy. The structural stability of the tested AR and AI nets under repeated wetting and drying cycles is primarily guaranteed by the hydrophobic nature of HDPE. Unlike natural fibers, HDPE does not exhibit significant hygroscopic swelling, ensuring that the mesh geometry and the resulting Φrw index remain stable over short-to-medium term exposure.

Regarding practical applications, the varying levels of the Φrw serve as a decision-support tool for selecting the most appropriate netting based on site-specific environmental conditions. A Φrw value approaching 100% characterizes highly permeable nets, suitable for scenarios where only moderate protection is required—such as mitigating the kinetic impact of light rainfall—while maintaining high ventilation. Conversely, lower Φrw values (e.g., 0.5) indicate nets with superior shielding capacity, ideal for regions prone to intense or prolonged precipitation where preventing fruit cracking and fungal diseases is a priority. Furthermore, the observed correlation between Φrw and the installation angle suggests that in wind-exposed sites, the structural inclination of the netting must be carefully designed to optimize water runoff and ensure the intended level of crop protection.

4. Conclusions

The need to objectively evaluate the performance of agrotextiles in terms of rainfall protection led to the development and characterization of the Φrw parameter, which was assessed through laboratory tests carried out on eight different nets (three AR and five AI) using a rain simulator. The results provided a comparative and quantitative picture of the protective capacity of the nets under a wide range of operating conditions.

The results of the tests, carried out by varying rainfall intensity, net inclination (10°, 20°, 30°), and warp orientation, led to the conclusions illustrated below.

AR nets confirmed their clear superiority in terms of protection from rainfall compared to the AI nets. In particular, the AR1 net consistently showed the best performance in terms of rain resistance, with average Φrw values around 60% for a 10° inclination and warp perpendicular to the slope, and values stabilizing between 40% and 50% in the most common installation conditions (20° and 30°, warp perpendicular to the slope). In contrast, AI nets showed average Φrw values generally above 60%, with the AI1 net allowing more than 90% of rainfall to pass through, confirming the inadequacy of the latter for rain protection alone.

The orientation of the weave and the inclination of the net tend to play a crucial role in determining the impact that rainfall intensity has on the Φrw value. In general, installation with a weave perpendicular to the slope provided better performance for AR nets; on the contrary, increased rainfall intensity and reduced inclination (10°) led to an increase in Φrw for the AR1 net, highlighting structural limitations under extreme water stress.

In addition, the data show that in areas subject to heavy rainfall, an inclination of no less than 20° is recommended, especially when AI nets are used for simultaneous protection against insects and rain.

The adoption of the Φrw index allows for a standardized comparison of net performance across varying rainfall intensities, inclination angles, and mesh orientations, representing the functional response of the material to different installation and climatic scenarios.

The introduction of the Φrw parameter, therefore, represents a significant contribution to scientific research on crop protection from precipitation and, above all, from extreme events, as it provides a quantifiable and objective index for the selection of agrotextiles, so that farmers and producers can base their choices on a verified performance standard, optimizing greenhouse and screen house coverings according to climate risk and specific crops.

Despite the relevant findings, some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the experimental tests were conducted under controlled laboratory conditions, which may not fully replicate the complexity of natural environments, particularly regarding wind effect and sudden changes in gust direction. Second, this research focused on new net samples; therefore, the effects of long-term environmental degradation, such as UV exposure, dust accumulation, and mechanical wear, on Φrw were not evaluated. In addition, while a wide range of rainfall intensities was simulated, future studies should incorporate varying drop size distributions to better mimic specific extreme weather events. Finally, while this study focuses exclusively on the Φrw index of AI and AR nets, it is important to acknowledge that the selection of an agricultural net involves a trade-off between multiple functional requirements. For AI nets, specifically, reducing pore size to enhance rain shielding may potentially impact air ventilation and pest exclusion efficiency. This study does not aim to provide a comprehensive agronomic evaluation but rather a specific hydraulic characterization. Future studies should integrate these hydraulic findings with aerodynamic and biological data to optimize net design for multifunctional crop protection.

The data obtained underscore the need to develop hybrid and multifunctional solutions that combine the high rain resistance of AR nets with the excellent ventilation and insect protection of AI nets. The challenge for future research is to create a new generation of agrotextiles that can balance low water permeability (low Φrw value) with high air permeability to ensure an optimal microclimate for the plant, prevent plant diseases, and minimize the use of chemicals. In any case, as part of the research carried out, further tests were conducted to evaluate the open-field rainfall permeability, the UV aging, and the durability of agricultural nets. This data will be implemented and compared with laboratory data for future scientific developments. In this regard, future research should focus on the development of next generation agrotextiles featuring asymmetric mesh geometries and hydrophobic coatings, specifically designed to enhance water runoff even at low installation angles. Regarding testing methodologies, a transition from controlled laboratory environments to open field monitoring via Internet of Things-based sensor networks is essential. This approach would enable the real-time assessment of net performance against natural rainfall, providing a robust field validation of the laboratory-derived rainwater permeability index.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S.M., S.C., P.P., G.S. and I.B.; methodology, G.S.M.; software, A.M.N.M.; validation, G.S.M., S.C., P.P., G.M., G.S., R.P. and I.B.; formal analysis, G.S.M. and A.M.N.M.; investigation, A.M.N.M.; resources, G.S.M.; data curation, G.S.M. and A.M.N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.N.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M.N.M., G.S.M., S.C., P.P., G.M., G.S., R.P. and I.B.; visualization, G.S.M. and A.M.N.M.; supervision, G.S.M.; project administration, G.S.M. and I.B.; funding acquisition, G.S.M., S.C., P.P. and I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union—Next-GenerationEU—National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP)—MISSION 4 COMPONENT 2, INVESTMENT N. 1.1, CALL PRIN 2022 PNRR D.D. 1409 14-09-2022—Project Title “RESCUE-NETS—RESilience to Climate change in agricultural production under multi-pUrposE NETS"—Cod. Prog. P2022YSF3K—CUP D53D23022120001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data shown in this paper are available on request to the corresponding author due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alberto Ferruccio Piccinni for his valuable and helpful suggestions during the tests and for improving the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kalcsits, L.; Musacchi, S.; Layne, D.R.; Schmidt, T.; Mupambi, G.; Serra, S.; Mendoza, M.; Asteggiano, L.; Jarolmasjed, S.; Sankaran, S.; et al. Above and Below-Ground Environmental Changes Associated with the Use of Photoselective Protective Netting to Reduce Sunburn in Apple. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 237, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, A.; Briassoulis, D.; Papardaki, N.G.; Mistriotis, A. Evaluation of insect-proof agricultural nets with enhanced functionality. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 208, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statuto, D.; Abdel-Ghany, A.M.; Starace, G.; Arrigoni, P.; Picuno, P. Comparison of the efficiency of plastic nets for shading greenhouse in different climates. In Innovative Biosystems Engineering for Sustainable Agriculture, Forestry and Food Production, Proceedings of the International Mid-Term Conference 2019 of the Italian Association of Agricultural Engineering (AIIA), Matera, Italy, 12–13 September 2020; Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 67, pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerger, V.; Bojic, D.; Bosc, P.; Clark, M.; Dale, D.; England, M.; Hoogeveen, J.; Koo-Oshima, S.; Mejias Moreno, P.; Muchoney, D.; et al. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture–Systems at Breaking Point. Synthesis Report 2021; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Action Plan for the Implementation of the FAO Strategy on Mainstreaming Biodiversity Across Agricultural Sectors 2024–2027; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2024; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jägermeyr, J.; Müller, C.; Ruane, A.C.; Elliott, J.; Balkovic, J.; Castillo, O.; Faye, B.; Foster, I.; Folberth, C.; Franke, J.A.; et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals Homepage. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Cartwright, E.D. Fifth National Climate Assessment Reveals Urgent Action Needed to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Clim. Energy 2024, 40, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formisano, L.; Ciriello, M.; El-Nakhel, C.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. Dataset on the effects of anti-insect nets of different porosity on mineral and organic acids profile of Cucurbita pepo L. fruits and leaves. Data 2021, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Han, E.J.; Shim, C.K.; Hong, S.J. Management of Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) in tomato green house by using screen nets and light traps. Korean J. Org. Agric. 2025, 33, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, M.; Jurić, S.; Vinceković, M.; Levaj, B.; Fruk, G.; Jemrić, T. Effect of yellow and Stop Drosophila Normal anti-insect photoselective nets on vegetative, generative and bioactive traits of peach (cv. Suncrest). J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 29, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Starace, G.; De Pascalis, L.; Lippolis, M.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G. Test Results and Empirical Correlations to Account for Air Permeability of Agricultural Nets. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 150, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Russo, G.; Briassoulis, D.; Mistriotis, A.; Hemming, S.; Waaijenberg, D. Plastic Nets in Agriculture: A General Review of Types and Applications. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2008, 24, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manja, K.; Aoun, M. The Use of Nets for Tree Fruit Crops and Their Impact on the Production: A Review. Sci. Horti. 2019, 246, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vox, G.; Teitel, M.; Pardossi, A.; Minuto, A.; Tinivella, F.; Schettini, E. Sustainable Greenhouse Systems. In Sustainable Agriculture: Technology, Planning and Management; Salazar, A., Rios, I., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 14, pp. 1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Serra, S.; Borghi, S.; Mupambi, G.; Camargo-Alvarez, H.; Layne, D.; Schmidt, T.; Kalcsits, L.; Musacchi, S. Photoselective Protective Netting Improves “Honeycrisp” Fruit Quality. Plants 2020, 9, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, J. Citrus Fruit-Cracking: Causes and Occurrence. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meland, M.; Skjervheim, K. Rain cover protection against cracking for sweet cherry orchards. Acta Hortic. 1998, 2, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, M.M.; Willits, D.H. Role of Excess Water in Tomato Fruit Cracking. HortScience 1995, 30, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, S.; Schouten, R.; Silva, A.P.; Gonçalves, B. Sweet Cherry Fruit Cracking Mechanisms and Prevention Strategies: A Review. Sci. Horti. 2018, 240, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitel, M. The Effect of Insect-Proof Screens in Roof Openings on Greenhouse Microclimate. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2001, 110, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Di Palma, A.; Germinara, G.S.; Lippolis, M.; Starace, G.; Scarascia-Mugnozza, G. Experimental Nets for a Protection System against the Vectors of Xylella fastidiosa Wells et Al. Agriculture 2019, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, R.; Statuto, D.; Picuno, P. Effects of Greenhouse Lime Shading on Filtering the Solar Radiation. In Proceedings of the 48th Symposium “Actual Tasks on Agricultural Engineering”, Zagreb, Croatia, 2–4 March 2021; Volume 1, pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Missaoui, R.; Bournet, P.E.; Chantoiseau, E.; Vuillermet, D. Impact of insect proof nets on the microclimate and on the risks of fungal development in a plant cover. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on New Technologies for Sustainable Greenhouse Systems: GreenSys2023, Cancun, Mexico, 22–27 October 2023; ISHS: Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2023; Volume 1426, pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, S.; Starace, G. Experimental Evaluation of the Loss Coefficient of Insect-Proof Agro-Textiles and Application to Wind Loads. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oula, P.Q.; Martin, T.; Fondio, L.; Coulibaly, N.; Koné, D.; Djézou, W.B.; Parrot, L. Benefit Cost Analysis of innovation packages to reduce the use of synthetic pesticides: The cases of combined insect-proof nets with Neem and Carapa oil for tomato protection. In Proceedings of the XXXI International Horticultural Congress (IHC2022): International Symposium on Urban Horticulture for Sustainable Food, Angers, France, 14 August 2022; ISHS: Korbeek-Lo, Belgium, 2022; Volume 1356, pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, M.Y.; Nambeesan, S.U.; Diaz-Perez, J.C. Shade Nets Improve Vegetable Performance. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghany, A.; Al-Helal, I.; Alkoaik, F.; Alsadon, A.; Shady, M.; Ibrahim, A. Predicting the Cooling Potential of Different Shading Methods for Greenhouses in Arid Regions. Energies 2019, 12, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.M.; Xu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Xu, J.; Shah, I.H.; Sabir, I.A.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Horticulture Crop under Pressure: Unraveling the Impact of Climate Change on Nutrition and Fruit Cracking. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, A.; Knoche, M. Penetration of Sweet Cherry Skin by 45Ca-Salts: Pathways and Factors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, P.; Akgül, H.; Demirtaş, I.; Sarısu, C.; Aksu, M.; Gubbuk, H. Effect of Preharvest Sprays of Calcium Chloride and Sucrose on Cracking and Quality of ‘Burlat’ Sweet Cherry Fruit. J. Plant Nutr. 2013, 36, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, S.; Lippolis, M.; De Musso, M.; Starace, G. Evaluation of Rain Permeability of Agricultural Nets: First Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 11th International AIIA Conference, Bari, Italy, 5–8 July 2017; Italian Association of Agricultural Engineering (AIIA): Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pagnotta, L. Sustainable Netting Materials for Marine and Agricultural Applications: A Perspective on Polymeric and Composite Developments. Polymers 2025, 17, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricop, F.; Scarlat, R.; Drambei, P.; Rusu, L. Multifunctional agrotextile for agriculture/horticulture. In Proceedings of the International Symposium, ISB-INMA TEH’ 2017, Agricultural and Mechanical Engineering, Bucharest, Romania, 26–28 October 2017; pp. 611–614. [Google Scholar]

- Antignus, Y. UV-blocking nets as a novel integrated pest management tool. Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 1024–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzakis, N. Effect of various UV-blocking nets on the quality of bell pepper and cucumber. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 124, 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, B.; Gysin, W.; Rusterholz, H.P. An Environmentally Friendly Method to Protect Box Trees (Buxus spp.) from Attacks by the Invasive Moth Cydalima perspectalis. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, G.; Pelletier, F.; Larose, M.; Knoch, S.; Pouchet, C.; Dumont, M.J.; Tavares, J.R. Insect netting: Effect of mesh size and shape on exclusion of some fruit pests and natural enemies under laboratory and orchard conditions. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastronardi, G.; Puglisi, R.; Castellano, S.; Picuno, P.; Martellotta, A.M.N.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Blanco, I. Experimental Evaluation of Anti-Rain Agricultural Nets: Structural Parameters and Functional Efficiency. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, A.; Valera Martínez, D.L.; Molina-Aiz, F.; Peña-Fernández, A.; Marín-Membrive, P. Microclimate Evaluation of a New Design of Insect-Proof Screens in a Mediterranean Greenhouse. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipiński, A.J.; Lipiński, S. Binarizing water sensitive papers–how to assess the coverage area properly? Crop. Prot. 2020, 127, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martellotta, A.M.N.; Castellano, S.; Blanco, I.; Mastronardi, G.; Picuno, P.; Puglisi, R.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G. Standard Procedures Proposal of Laboratory Experimental Tests Assessment for Water Permeability of Anti-Rain Agricultural Nets. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, G.; Fraschetti, P.; Lena, F.; Perconti, W.; Piervitali, E.; Pavan, V. Gli Indicatori del Clima in Italia nel 2021 Anno XVII; Rapporto ISPRA, Stato dell’Ambiente, 98/2022; ISPRA: Roma, Italy, 2022; ISBN 978-88-448-1119-8. [Google Scholar]

- Efron, B. Student’s t-test under symmetry conditions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1969, 64, 1278–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Mistriotis, A.; Eleftherakis, D. Mechanical behaviour and properties of agricultural nets—Part I: Testing methods for agricultural nets. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Mistriotis, A.; Eleftherakis, D. Mechanical behaviour and properties of agricultural nets. Part II: Analysis of the performance of the main categories of agricultural nets. Polym. Test. 2007, 26, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.