Abstract

Enhanced rock weathering is regarded as a promising carbon dioxide removal method because of its potential to sequester soil inorganic carbon (SIC). However, the influence of enhanced rock weathering on changes in soil organic carbon (SOC) content, fractions and stability remains poorly understood. A randomized block experiment design employing five basalt addition rates (0 (CK), 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2) and four replicates was designed to investigate the influences of basalt addition on SOC and SIC content and stocks, SOC fractions and SOC stability in subtropical cropland, where Zea mays L. and Brassica juncea (L.) Czern were annually rotated. Soil samples were collected from depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm one year after the addition of basalt. The results showed that enhanced rock weathering increased the total carbon content and stock by increasing both the SOC and SIC in a one-year field experiment. Compared with CK, basalt addition rates of 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2 increased the SOC stock by 16%, 23%, 21% and 19%, respectively, and the SIC stock by 37%, 30%, 35% and 32%, respectively. The labile carbon fraction was the primary organic carbon fraction, which accounted for more than 40% of the total SOC content. Enhanced rock weathering altered the content of the very labile carbon fraction due to its high sensitivity to basalt addition, but had little effect on the stable carbon fraction content in a one-year field experiment. Compared with CK, basalt addition increased the very labile carbon fraction content by 12% and 46%, respectively, according to samples from depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm. Under basalt addition rates of 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, the SOC stability index was 26%, 21%, 17% and 20%, respectively, lower than that under the 0-addition rate in a one-year field experiment, which was 1.63, indicating that enhanced rock weathering reduced the SOC stability. Our findings indicated that enhanced rock weathering increased soil carbon (both of SOC and SIC) sequestration, but reduced the SOC stability in a one-year field experiment in subtropical croplands. These observed trends in changes in soil carbon will be further tested and evaluated as the experiment continues in the future.

1. Introduction

Global warming, attributable to the sustained increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations (e.g., carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide), constitutes one of the most critical environmental challenges of the contemporary era, with far-reaching consequences for natural ecosystems and human societies [1,2]. In its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), released in 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected that the global mean surface temperature over the near-term period of 2021–2040 is likely to reach a level of approximately 1.5 °C relative to the pre-industrial level (defined as the 1850–1900 average) [3]. It is estimated that future climate warming will present considerable challenges to a wide range of sectors, including national food security, human health, water resources and major infrastructure projects [1]. Consequently, using effective methods to enhance ecosystem carbon sinks and reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations has become imperative for mitigating global warming [4,5].

Soil is the largest carbon pool in terrestrial ecosystems, and can be divided into two primary fractions: the soil organic carbon (SOC) pool and the soil inorganic carbon (SIC) pool. It is estimated that the soil carbon pool at a depth of 0–1 m (2500 PgC) is approximately 3.3 times the atmospheric carbon pool (760 PgC) and 4.5 times the vegetation carbon pool (560 PgC), meaning that it plays an extremely vital role in mitigating global warming [6,7,8]. Due to its important role in regulating soil ecosystem functions and influencing global climate warming, the SOC pool has attracted considerable attention [9,10]. Consequently, many studies have investigated changes in SOC in response to land management practices at the regional and national scales [11,12,13]. The SIC is typically associated with carbonates in soil, and it has received limited attention in previous studies due to its high stability and resistance to changes caused by land management practices [14,15]. Nevertheless, recent studies have indicated that the SIC pool may also be affected by different management practices, thereby exerting a considerable influence on the soil carbon pool [16,17,18]. Therefore, understanding the influences of land management practices on both the SOC and SIC pool are crucial for gaining deeper insights into soil carbon dynamics and their role in global climate warming [19,20].

Enhanced silicate rock weathering has been identified as a promising carbon dioxide removal method [5,21], in which carbon dioxide is converted into bicarbonate [22]. In one pathway, the formed bicarbonate is precipitated in the soil and temporarily stored as pedogenic carbonates [5,22]. Alternatively, the bicarbonate is transported out of the soil via groundwater and river runoff, and ultimately stored as dissolved bicarbonate in the ocean or is subjected to carbonate burial in marine sediments [22,23]. In addition, enhanced silicate rock weathering could promote SOC sequestration through both soil mineral carbon pumps and microbial carbon pumps [24,25]. A two-year-long experiment in tropical rubber plantations in Southeast China indicated that enhancing silicate rock weathering significantly increased the SOC and SIC content, with the increase being greater in the former than in the latter [24]. However, a 15-month mesocosm experiment at the experimental facility of Campus Drie Eiken, University of Antwerp, has demonstrated that enhancing silicate rock weathering exerts no significant influence on SOC and SIC stocks [25]. The contrasting findings across these studies can be attributed to differences in natural environmental conditions (e.g., soil moisture, temperature and soil pH) and the study designs employed (e.g., application amounts, rock particle size and treatment duration). For instance, findings of previous studies have indicated a substantial correlation between the soil water content and the weathering rate of silicate rocks, and that the ability of carbon sequestration by enhanced silicate rock weathering decreases with intensified soil aridity [5,26]. In addition, a low soil pH could promote silicate rock weathering, and the silicate rock weathering rate at a soil pH of 4.0 is 17 times that at a pH of 6.0, thereby influencing carbon sequestration by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere [5]. The climate in Southwest China, characterized by high temperatures and humidity, in conjunction with acidic soil with low pH (<6.0), creates a favorable environment for silicate rock weathering. However, the effect of enhanced silicate rock weathering on soil carbon sequestration in Southwest China remains uncertain, as indicated by the present research.

In this study, we conducted a field experiment to evaluate the influence of enhanced silicate rock (basalt) weathering on SIC and SOC sequestration in subtropical croplands. We hypothesized that enhanced rock weathering increases the content and stock of SOC and SIC by increasing the plant biomass and promoting bicarbonate formation, but reduces the SOC stability through priming effects from labile carbon inputs, microbial activity enhancement and pH-mediated desorption of protected organic matter. The objectives of this study were to (1) compare the changes in contents and stock of SOC, SIC and TC under different basalt addition rates; and (2) estimate the influences of enhanced rock weathering on SOC fractions and stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

This study was carried out at the Caoshang ecological observation sites (29.79° N, 106.45° E) in Beibei district, Chongqing, which has a subtropical monsoon climate with humid and hot summers and wet and warm winters. For the past 10 years, the average air temperature has been 18.2 °C, and the average annual precipitation has been 1160 mm. The soil type in the study area is classified as Luvisols according to the WRB soil taxonomy, and the typical natural vegetation in the study area is subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forest. The study site is an area of cropland that has been cultivated for over 50 years. Conventional tillage practices were conducted in the study site with annual rotation of maize and vegetables over one year. The initial soil properties at a depth of 0–30 cm were as follows: soil pH 5.08, bulk density 1.36 g·cm−3, SOC content 6.56 g·kg−1, SIC content 1.18 g·kg−1, total nitrogen 0.71 g·kg−1, total phosphorus 1.30 g·kg−1 and total potassium 17.5 g·kg−1.

2.2. Experimental and Sampling Design

This experiment was established in late June 2024. The experiment was conducted on the farmland of a single farmer, with a total area of only 110 m2. The application of consistent farming practices, coupled with the maintenance of diminutive plot sizes, engendered a condition of relative uniformity in soil characteristics. Consequently, the impact of soil spatial heterogeneity was effectively nullified. This experiment used a randomized block experiment design with four blocks of 2 × 11 m; in each block, five 2 × 2 m plots were designated for the experiment treatments. A barrier of bricks and concrete between adjacent plots was erected to avoid basalt, soil water and surface runoff cross-contamination. For the five treatments, basalt rock powder was applied in late June 2024 at five addition rates (0 (CK), 2.5 (XW25), 5 (XW50), 10 (XW100) and 20 kg·m−2 (XW200)) in these plots. The main chemical compositions of basalt rock powder used in this study were SiO2 45.0%, Al2O3 14.4%, Fe2O3 12.6%, CaO 8.8%, MgO 7.4%, Na2O 4.5%, TiO2 3.0%, K2O 2.5%, P2O5 1.1% and MnO 0.2%. The basalt rock powder was spread evenly over the surface (0 cm) of the cropland by hand, and then thoroughly mixed with the topsoil (0–15 cm) through two rounds of plowing spaced four days apart, with a plowing depth of 0–15 cm. After two months of fallow, leaf mustard (Brassica juncea (L.) Czern) was planted in September 2024, and harvested in March 2025 after a six-month growing period. Then, maize (Zea mays L.) was planted immediately after in these plots. Fertilizer application could affect the weathering of basalt and changes in soil carbon by altering the soil physicochemical properties and microbial communities [5,17,26]; therefore, no fertilizers were applied during the cultivation of these two seasonal crops in order to accurately assess the influences of basalt addition on soil carbon changes.

A recent review by Swoboda et al. [27] showed that the duration of agronomic trials with silicate rock powders typically ranges from several months up to two years, and the effect on soil changes decreased after the first year or after the second growing season [28,29]. In addition, the high temperatures, humidity and acidic soil with a low pH in the study area contribute to the silicate rock weathering [5]. Consequently, a short-term study lasting one year is required to investigate the impact of silicate rock weathering on soil carbon sequestration in Southwest China. Soil samples were collected in early July 2025. The basalt rock powder improved aeration of the root systems, thus facilitating the vertical migration of dissolved weathering products and dissolved organic carbon to a depth of 15–30 cm. Consequently, soil samples were collected at two depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm. Three soil cores were randomly sampled from each plot to combine one composite soil sample, eliminating the within-plot variability assessment. In total, 40 soil samples (4 blocks × 5 treatments × 2 soil depths) were collected in this study. After removing the crop roots and stones, these soil samples were air-dried and sieved with 2 mm and 0.25 mm sieves for C and soil pH analyses.

2.3. Soil Analysis

The soil pH was measured using the PHS-3C instrument (INESAS Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with 1:2.5 soil/water solutions [10]. The crop biomass was measured using the whole-plant harvesting method [30], and the soil water content was measured using the oven drying method [10]. The SOC and SIC contents were measured using a solid TOC cube (Elementar, Langenselbold, Germany) according to the ThG specification of DIN 19539 [30]. The TC content was calculated as the sum of the SIC and SOC content. Soil bulk density was measured via steel cores with a volume of 100 cm3. The TC, SOC and SIC stocks at depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm were calculated using the following equation [10]:

where Cstock is the TC, SOC or SIC stock (Mg·ha−1); Ccontent is the TC, SOC or SIC content (g·kg−1); BD is the bulk density (g·cm−3); and SD is the soil depth (cm).

The SOC content was divided into three carbon fractions according to the oxidizability using the revised Walkley–Black method [7,31]. In this method, 5 mL or 10 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (36 N H2SO4) is mixed with 10 mL of potassium dichromate (1 N K2Cr2O7), forming two acid-aqueous solutions (0.5:1 and 1:1). The addition of concentrated H2SO4 to a solution results in the release of heat, and the more concentrated H2SO4 added, the more heat released, thus leading to a higher solution temperature. Therefore, the organic carbon fractions were more oxidized with more concentrated H2SO4 added. The organic carbon that was oxidized by 5 mL 36 N H2SO4 was defined as the very labile carbon fraction (OCF1). The difference between the organic carbon oxidized by 10 mL and 5 mL 36 N H2SO4 was defined as the labile carbon fraction (OCF2). The difference between the total SOC content and the organic carbon oxidized by 10 mL H2SO4 was defined as the stable carbon fraction (OCF3). Using the organic carbon fractions with different stabilities, the SOC stability was calculated using the following equation [32]:

where SOCstability is the stability of SOC, and OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 were the very labile, labile and stable carbon fraction contents (g·kg−1), respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software. Before each analysis, normality and homoscedasticity of the data set were assessed to meet the analyses’ assumptions. One-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of basalt addition rates on the contents and stocks of TC, SOC and SIC; the contents of different organic carbon fractions (OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3); and the stability of SOC. Significant differences among means of the five addition rates were identified using the LSD test because its test sensitivity for the between-group mean is the highest. Simple linear models were used to assess the effects of TC content on SOC and SIC content, the effects of TC stock on SOC and SIC stock and the effects of SOC content on different organic carbon fraction contents. The model assumption (e.g., linearity, normality of residuals) was tested. The R2 and standard error of the estimate were used to assess the model’s goodness of fit. The significance level of all statistical analyses was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Soil pH

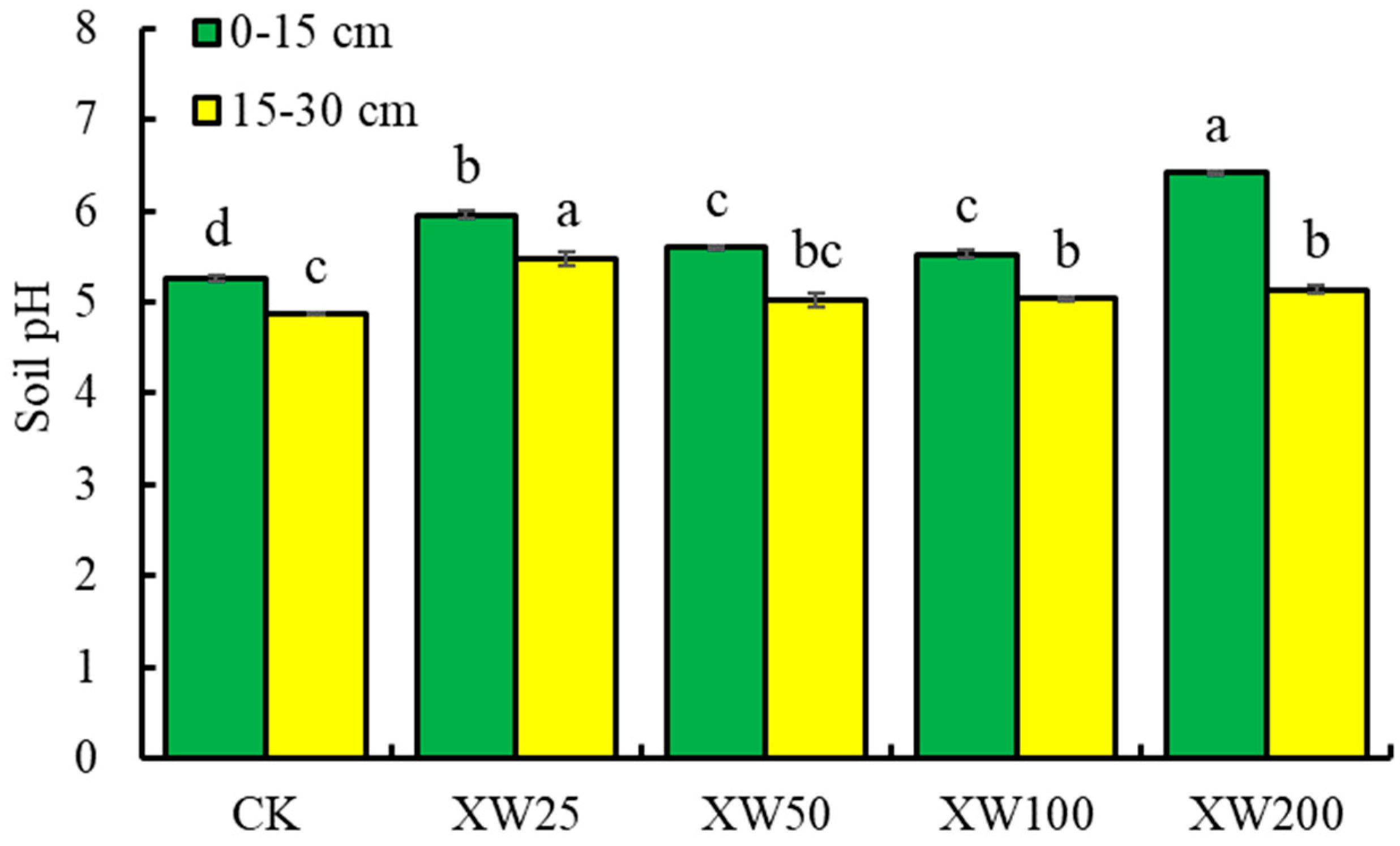

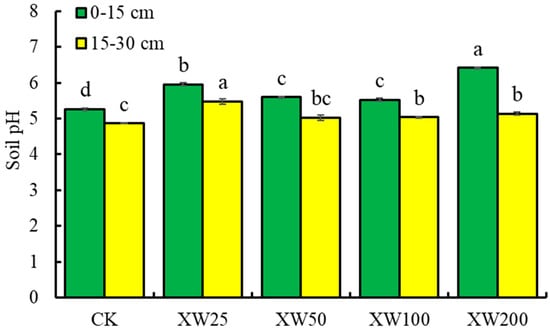

The soil pH ranged from 5.26 to 6.42 at the depth of 0–15 cm and from 4.87 to 5.48 at the depth of 15–30 cm (Figure 1), with basalt addition increasing soil pH at both depths. Compared with CK, the soil pH with XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments increased by 13.2%, 6.4%, 5.0% and 22.0%, respectively, at 0–15 cm, and by 12.5%, 3.2%, 3.4% and 5.4%, respectively, at 15–30 cm.

Figure 1.

Changes in soil pH at different basalt addition rates. Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among basalt addition rates. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively.

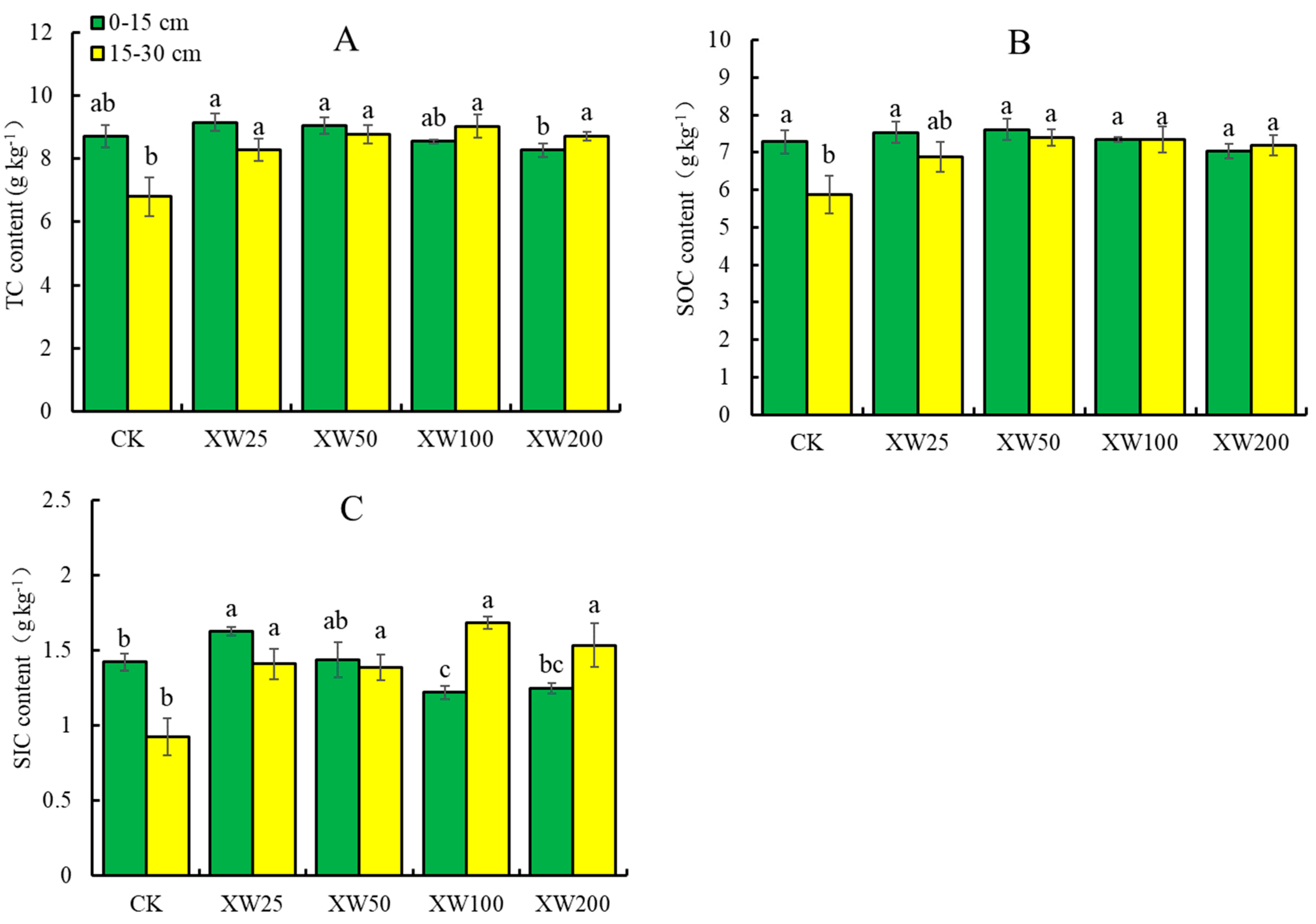

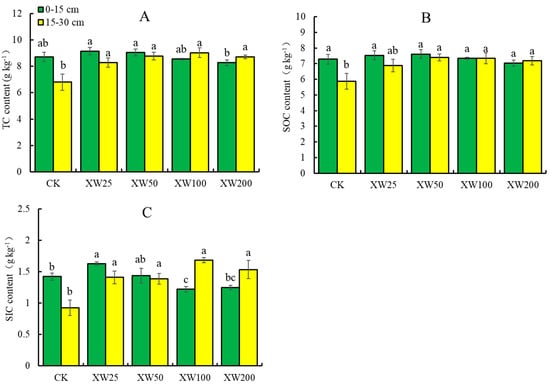

3.2. The Total Carbon, Soil Organic Carbon and Soil Inorganic Carbon Content

The TC contents ranged from 8.3 to 9.2 g·kg−1 at 0–15 cm and from 6.8 to 9.0 g·kg−1 at 15–30 cm (Figure 2A). Compared with CK, basalt addition did not affect the TC content at 0–15 cm. The TC content at 15–30 cm depth under XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments increased by 21.8%, 29.1%, 32.7% and 28.2%, respectively, compared with CK.

Figure 2.

Responses in total carbon (A), soil organic carbon (B) and soil inorganic carbon (C) content to different basalt addition rates. Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among basalt addition rates. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively. TC, total carbon; SOC, soil organic carbon; SIC, soil inorganic carbon.

The average SOC content under the five different basalt addition rates was 5.1 times the average SIC content (Figure 2B,C). Basalt addition had no significant effect on the SOC content at 0–15 cm depth, but significantly increased the SOC content at 15–30 cm depth. Compared with CK, the SOC content with the XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments increased by 17.1%, 25.9%, 24.9% and 22.3%, respectively. Basalt addition had different effects on the SIC content at depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm (Figure 2C). Compared with CK, the SIC content at 0–15 cm in SW25 increased by 14.4%, while it decreased by 14.2% and 12.1%, respectively, in XW100 and XW200. At 15–30 cm, the SIC content increased by 52.4%, 50.0%, 82.2% and 65.9%, respectively, in XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 in comparison with CK.

3.3. The Total Carbon, Soil Organic Carbon and Soil Inorganic Carbon Stocks

Basalt addition increased the TC stocks at both 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm (Figure 3A). Compared with CK, the TC stocks under the XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments increased by 11.0%, 11.7%, 6.5% and 6.7%, respectively, at 0–15 cm, and by 29.4%, 38.4%, 44.0% and 39.6%, respectively, at 15–30 cm. These results indicated that the increase in TC content at 15–30 cm was greater than that at 0–15 cm.

Figure 3.

Changes in total carbon (A), soil organic carbon (B) and soil inorganic carbon (C) stock under different basalt addition rates. Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among different basalt addition rates. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively. TC, total carbon; SOC, soil organic carbon; SIC, soil inorganic carbon.

Basalt addition did not affect the SOC stock at 0–15 cm (Figure 3B); however, the SOC stocks under the XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments at 15–30 cm increased by 24.4%, 34.9%, 35.6% and 33.4%, respectively, compared to CK. The responses of the SIC stocks to different basalt addition rates were different (Figure 3C). For example, compared with CK, the SIC stocks increased by 21.1% and 9.0%, respectively, under treatments XW25 and XW50 at 0–15 cm, but reduced by 6.9% under XW100. At 15–30 cm, the SIC stocks under treatments XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 were 61.7%, 60.9%, 97.6% and 79.7% higher than that for CK.

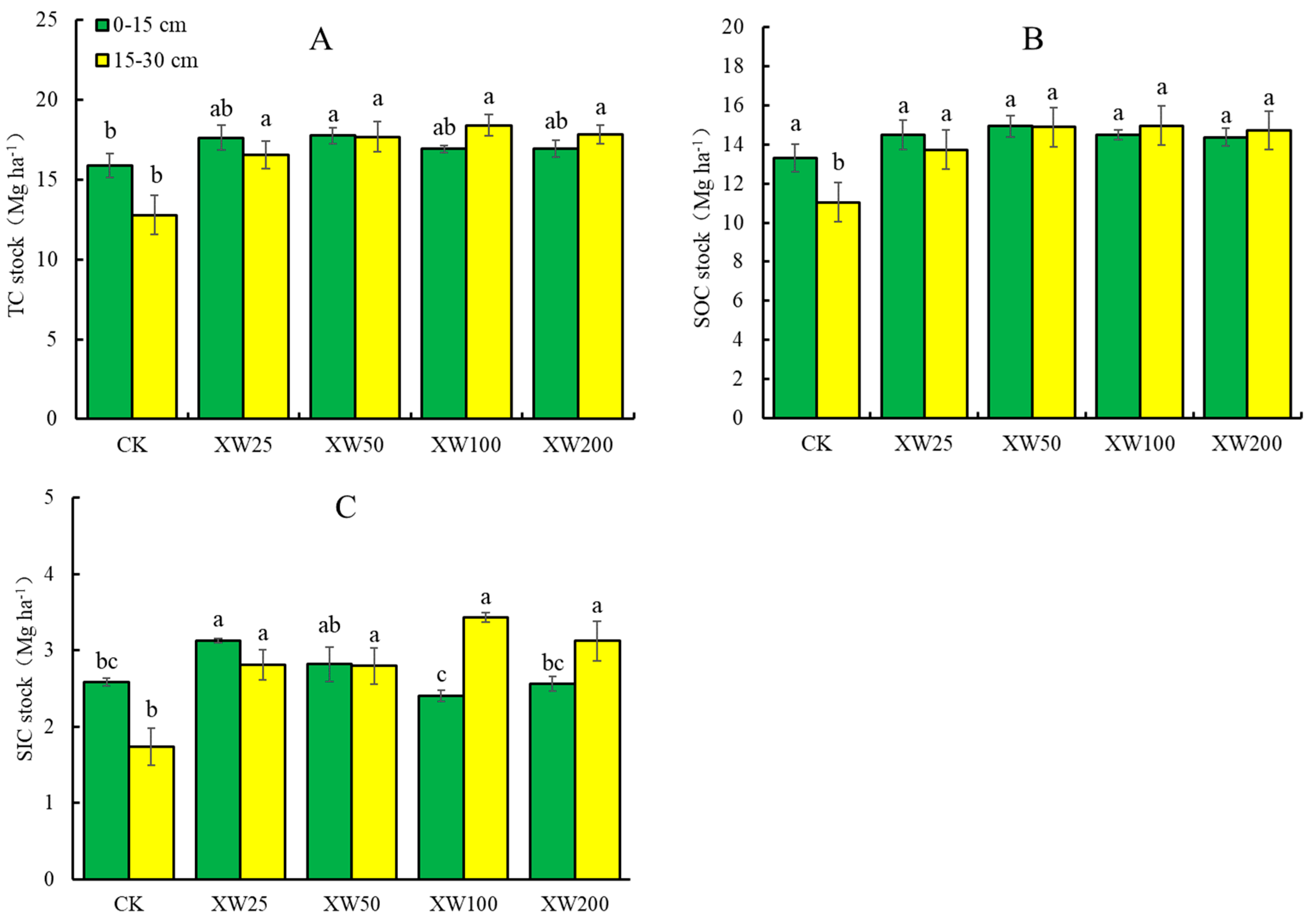

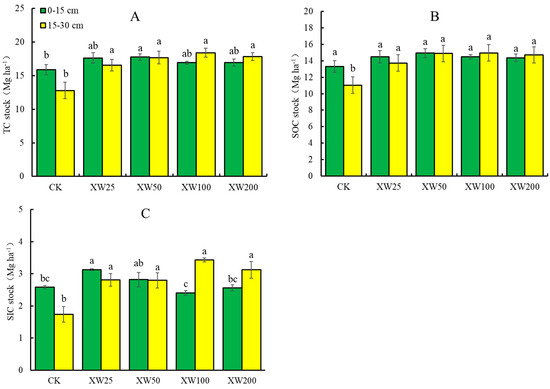

3.4. Effect of Total Carbon on Soil Organic Carbon and Soil Inorganic Carbon

The SOC and SIC content increased with greater TC content (Figure 4A). The regression coefficient values between the TC contents and the SOC and SIC contents were 0.80 and 0.20, respectively, suggesting that the proportions of SOC and SIC content in the TC content were 80% and 20%, respectively. Similarly, the SOC and SIC stocks increased with the increases in the TC stocks (Figure 4B). The regression coefficients between the TC stocks and SOC stocks (0.82) and SIC stocks (0.18) suggested that the proportional contributions of the SOC and SIC stocks to the TC stock were 82% and 18%, respectively.

Figure 4.

Linear relationships of total carbon contents with soil organic carbon or soil inorganic carbon content (A), and total carbon stocks with soil organic carbon or soil inorganic carbon stocks (B). TC, total carbon; SOC, soil organic carbon; SIC, soil inorganic carbon.

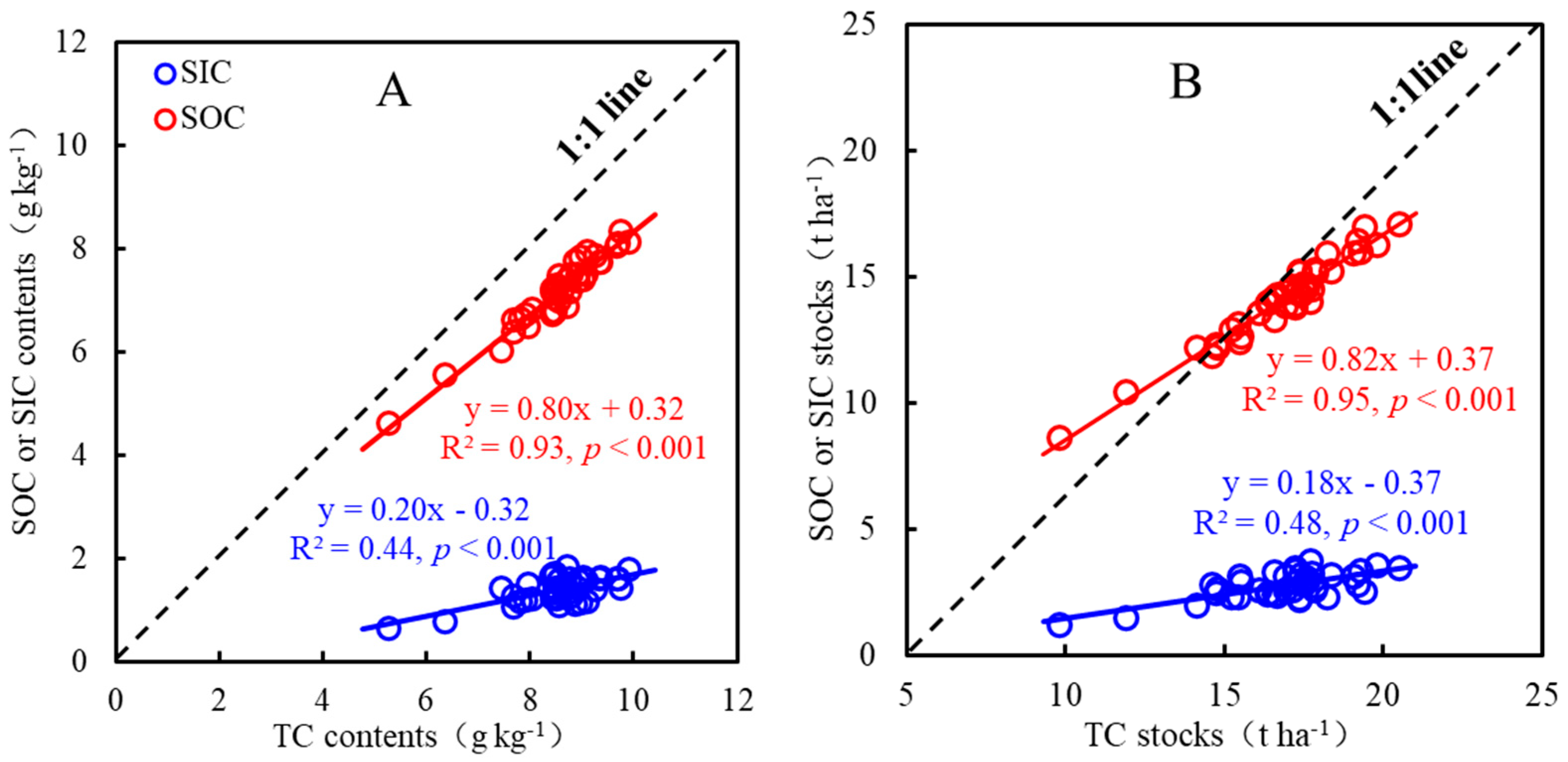

3.5. Contents of Soil Organic Carbon Fractions

Basalt addition had different effects on the soil organic carbon fractions at both soil depths (Table 1). Basalt addition increased the OCF1 content, but reduced the OCF2 content at 0–15 cm. Compared with CK, the treatments XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 increased the OCF1 content by 17.6%, 15.4%, 9.9% and 6.2%, respectively, but reduced the OCF2 content by 7.2%, 8.8%, 19.9% and 14.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Contents of soil organic carbon fractions under different basalt addition rates. Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among basalt addition rates. Values are means (±SE). OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 are the very labile, labile and stable carbon fractions, respectively. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively.

At 15–30 cm, the OCF1 and OCF2 contents all increased with basalt addition (Table 1). Compared with CK, the OCF1 content under treatments XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 increased by 45.0%, 51.1%, 43.7% and 44.1%, respectively, while the OCF2 contents increased by 50.7%, 34.3% and 26.1% with the XW50, XW100 and XW200 treatments, respectively. Basalt addition did not affect the OCF3 contents at both depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm.

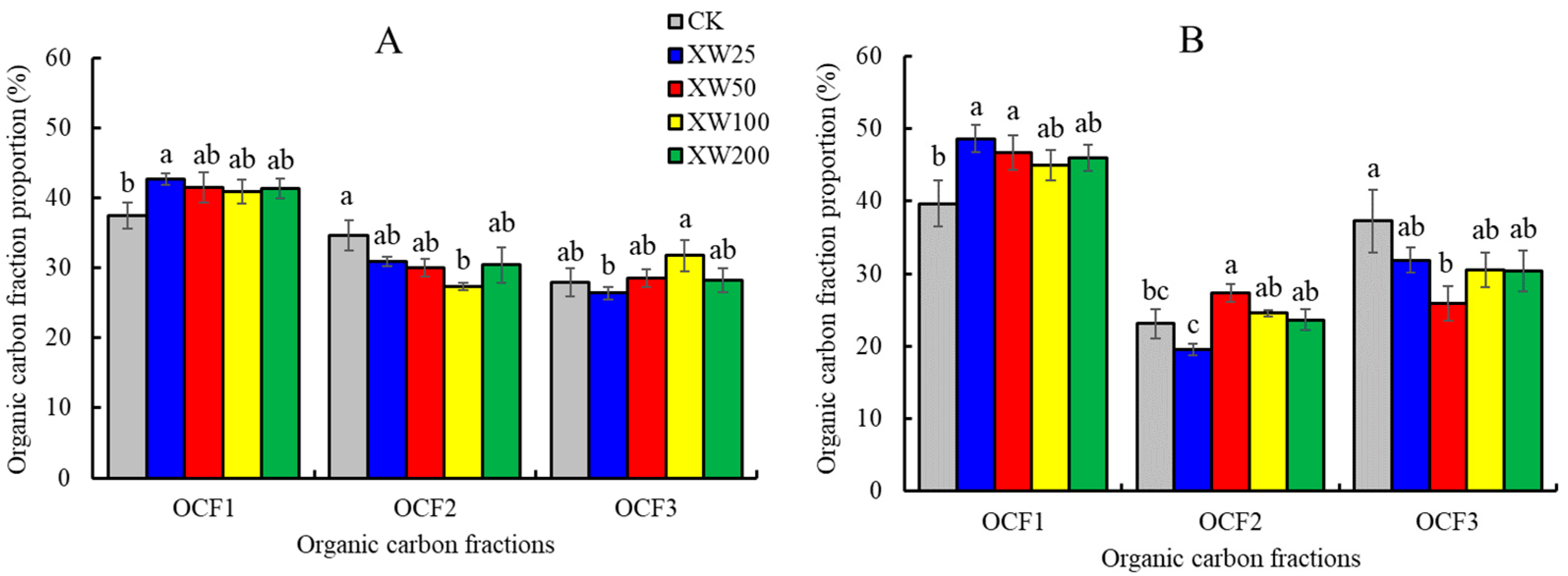

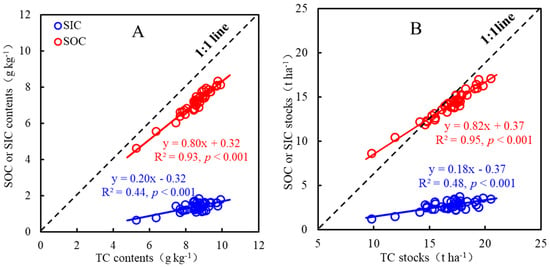

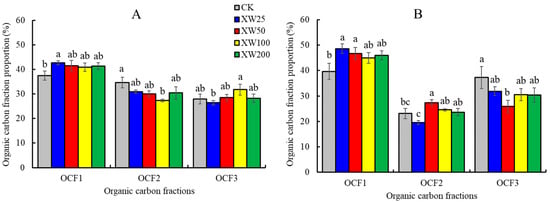

The proportions of OCF1 were higher than those of OCF2 and OCF3 under all the basalt addition rates (Figure 5). The mean proportions of OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 were 40.8%, 30.7% and 28.6%, respectively, at 0–15 cm, while the proportions were 45.2%, 23.6 and 31.2%, respectively, at 15–30 cm. Basalt addition increased the mean OCF1 proportion by 11.1% and 17.4%, respectively, at 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm in comparison with CK. Compared with CK, basalt addition reduced the mean OCF2 proportion by 14.3% at 0–15 cm, and reduced the mean OCF3 proportion by 20.3% at 15–30 cm.

Figure 5.

Proportions of soil organic carbon fractions in total soil organic carbon at the 0–15 cm (A) and 15–30 cm (B). Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among basalt addition rates. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively. OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 are the very labile, labile and stable carbon fractions, respectively.

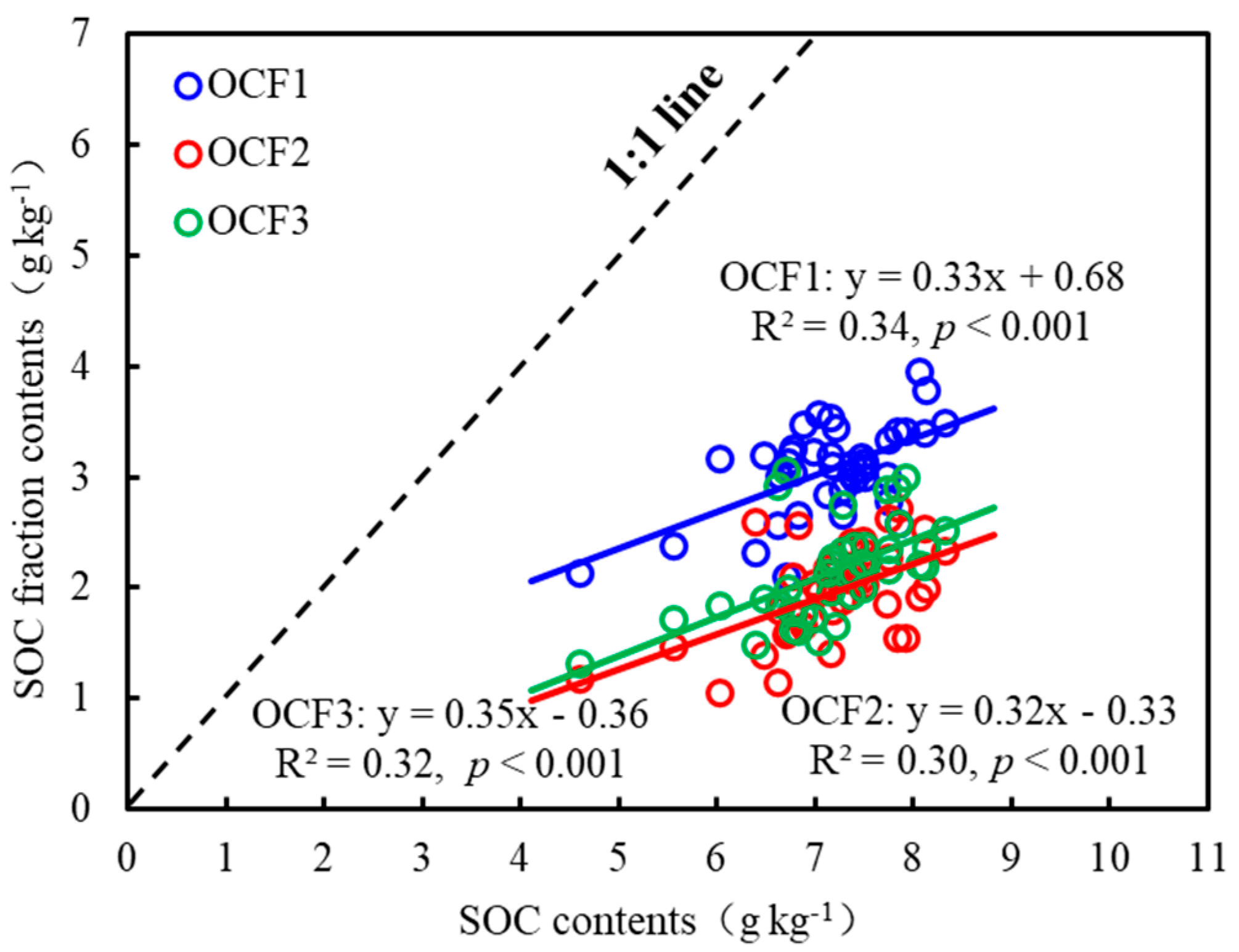

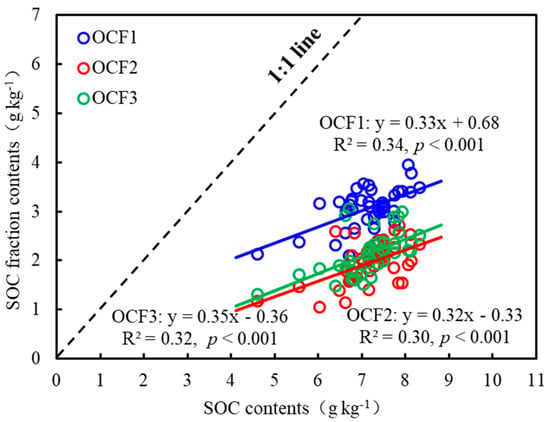

3.6. Effect of Soil Organic Carbon on Its Fractions

The OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 contents were all significantly increased with an increase in total SOC content (Figure 6). The regression coefficients between the total SOC contents and the OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 contents were 0.33, 0.32 and 0.35, respectively, suggesting that the proportional contributions of OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 to the SOC content were 33%, 32% and 35%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Linear relationships of soil organic carbon contents with different organic carbon fraction contents. OCF1, OCF2 and OCF3 are the very labile, labile and stable carbon fractions, respectively. SOC, soil organic carbon.

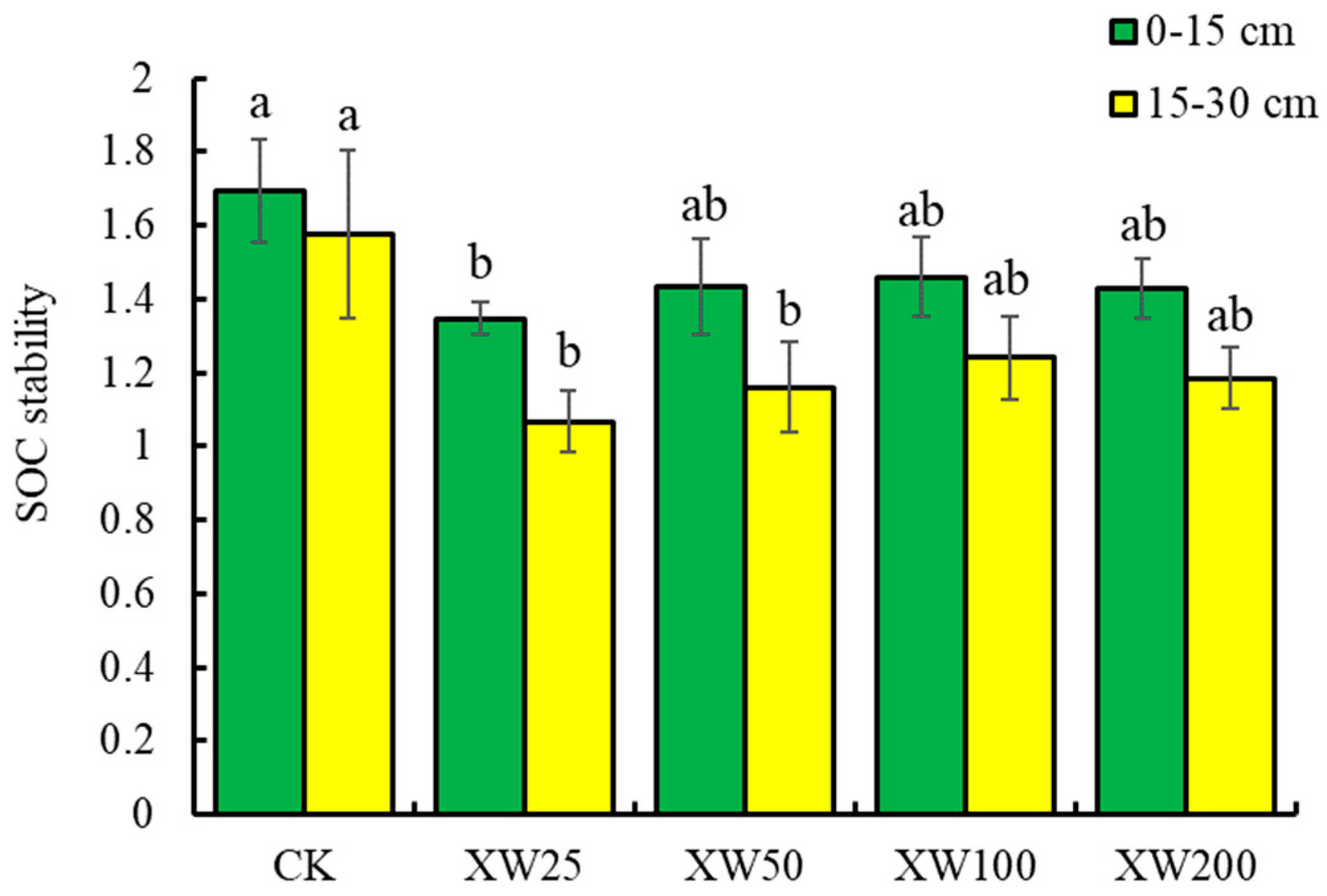

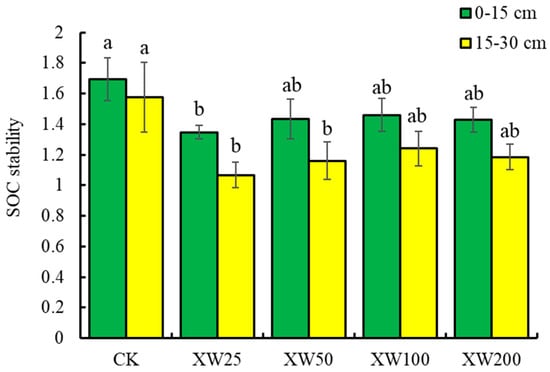

3.7. Changes in Soil Organic Carbon Stability

Basalt addition significantly reduced the SOC stability, and the reduction at 15–30 cm was greater than that at 0–15 cm (Figure 7). Compared with CK, basalt addition rates of XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 decreased the SOC stability by 24.4%, 15.4%, 13.8% and 15.6%, respectively, at 0–15 cm, and by 32.3%, 26.4%, 21.2% and 24.9%, respectively, at 15–30 cm.

Figure 7.

Responses of soil organic carbon stability to different basalt addition rates. Different lowercase letters mark significant differences at p < 0.05 among basalt addition rates. CK, XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200 indicate basalt addition rates of 0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 kg·m−2, respectively. SOC, soil organic carbon.

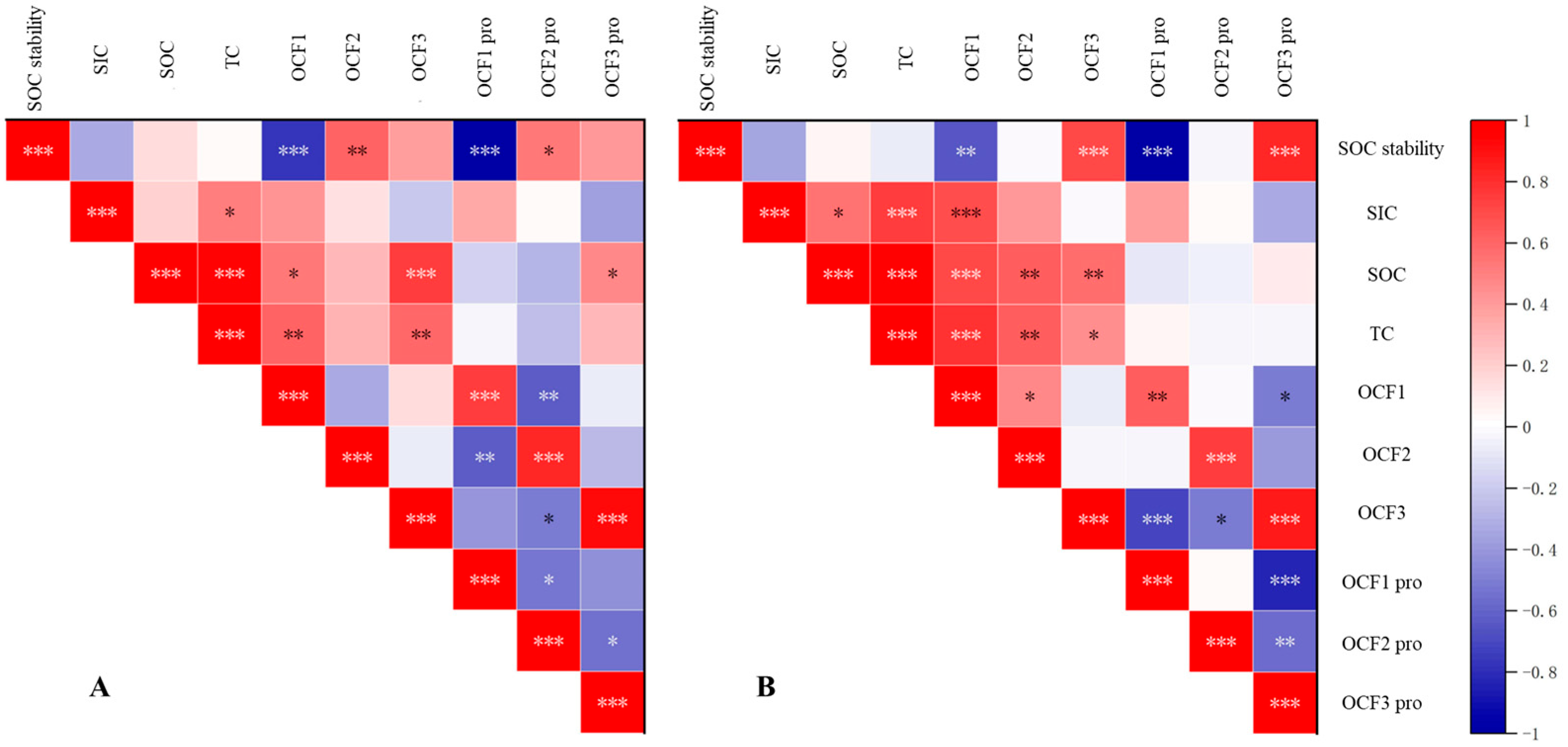

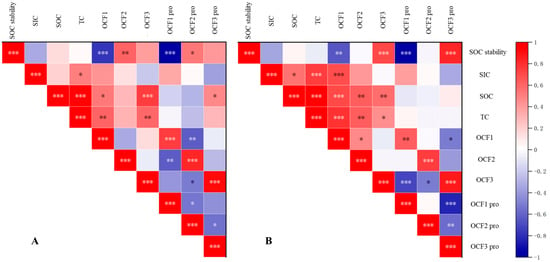

3.8. Correlations of Soil Organic Carbon Stability with Soil Carbon Fractions

Significant positive correlations were found between SOC content and TC, OCF1 or OCF3 contents at both depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm (Figure 8). The SOC stability was negatively correlated with the content and proportion of OCF1 at these two soil depths. The SOC stability was positively correlated with the content and proportion of OCF2 at 0–15 cm. However, at 15–30 cm, the SOC stability was significantly correlated with the content and proportion of OCF3.

Figure 8.

Correlations between soil organic carbon stability and different soil carbon fractions at 0–15 cm (A) and 15–30 cm (B). SOC, soil organic carbon; SIC, soil inorganic carbon; TC, total soil carbon; OCF1, very labile carbon fraction; OCF2, labile carbon fraction; OCF3, stable carbon fraction; OCF1 pro, proportion of very labile carbon fraction; OCF2 pro, proportion of labile carbon fraction; OCF3 pro, proportion of stable carbon fraction. *, **, *** indicate significant difference at p < 0.05, p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Basalt Addition Increases the Content and Stock of Soil Carbon

Our results showed that basalt addition significantly increased the soil pH by 12% (0.6 pH units) and 6% (0.3 pH units), respectively, at 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm (Figure 1). This result was consistent with the previous findings, which found the pH increase ranged from 0.4 to 2 pH units [5,27]. The increase in soil pH was mainly due to the release of silicate ions. Previous studies indicated that the silicate anion (SiO44−), released during the process of silicate rock weathering, is a highly alkaline substance, which reacts with H+ ions in aqueous solutions to form weakly acidic silicic acid (H4SiO4) [27]. The H+ ions from the water molecules are bound by the SiO44−, leaving a surplus of OH− ions, thereby increasing the soil pH. Our results indicated that the residual effect of silicate rock weathering in maintaining soil pH could last over 12 months or longer. This result was agreed with the reports that the residual effect in maintaining soil pH could take place over 24 months or longer, and the effects of basalt rock weathering on soil pH at topsoil and subsoil were similar [33]. That is, the enhanced rock weathering has a significant effect on improving acidic soils through enhancing the soil pH.

Basalt addition increased the TC content and stock by increasing both the SIC and SOC content and stock (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The increase in SIC content and stock after basalt addition confirmed the findings of Xu et al. [24] in Xishuangbanna and Steinwidder et al. [25] outside the experimental sites at the University of Antwerp. The SIC stock was increased by 1.3–1.6 Mg C·ha−1 under basalt addition treatments compared with CK (Figure 3C). The increases in SIC stocks were higher than those reported by Xu et al. [24], who found that silicate addition increased the SIC by approximately 0.7 Mg C·ha−1. The differences between these studies are mainly due to the difference in soil pH. The soil pH in the present study (around 5.5) was higher than that found by Xu et al. [24] in their study (around 4.9). It is well-known that the soil pH is an important factor influencing rock weathering, with a lower soil pH improving rock weathering [34]. However, a lower soil pH is detrimental to bicarbonate and carbonate formation, thereby preventing the sequestration of SIC. In addition, previous studies have shown that the amount of silicate added is another important factor affecting the sequestration of SIC, with a high amount of silicate addition improving this [5,25,27]. Consequently, the lower amount of silicate added (0.25 and 0.5 kg·m−2) in Xu et al.’s [24] study resulted in lower SIC sequestration. Steinwidder et al. [25] estimated that the theoretical maximum SIC sequestration of basalt addition was 23.6 Mg C·ha−1 according to the application rate (5 kg·m−2) and base cation content in basalt. This result indicated that enhanced silicate weathering has great potential to promote SIC sequestration in Southwest China. However, the theoretical maximum SIC sequestration was not achieved due to the kinetic limitations, e.g., rock particle size, soil type, plant species, climate and weather [5,27]. For example, the low soil pH improves the basalt rock weathering, but it is detrimental to bicarbonate and carbonate formation, thereby resulting in low soil carbon sequestration [5,34]. The basalt rock particle size influences weathering rates, and the small rock particle size with high reactive surface area enhances its weathering and the capacity of soil carbon sequestration [27].

Similarly, basalt additions increased the SOC content and stock in the study area (Figure 2 and Figure 3), which agreed with the findings of Xu et al. [24] in a two-year field experiment in Xishuangbanna. The SOC increase in the present study was mainly due to two important reasons. First, basalt weathering released a large amount of nutrients essential for plant growth and mitigated the influences of soil acidification on plants, thereby promoting plant growth [26,35]. Generally, the nutrients supplied by enhanced silicate rock weathering were determined by its mineralogy. Anda et al. [33] in Malaysia reported that the enhanced basalt rock weathering significantly increased the Ca, Mg, K and P both in the forms of exchangeable cations and soluble cations [33]. The silicate rock powder used in the present study contains a lot of nutrients (e.g., K2O, P2O5, CaO, MgO and SiO2), and these nutrients could be released during the enhanced rock weathering, thus enhancing the plant growth. Our results indicated that the crop biomass increased by 24%, 31%, 27% and 33%, respectively, under treatments XW25, XW50, XW100 and XW200. The increase in crop biomass improved the input of organic matter into soils, thereby increasing SOC sequestration. Second, basalt addition promoted mineral-associated organic matter and macroaggregate formation, thus reducing the decomposition of organic carbon and increasing SOC sequestration [24,25]. In our study, the SOC content increased by 11% (0.7 g·kg−1) on average with the basalt addition treatments, which was lower than the increase (22%, 3 g·kg−1) found in Xishuangbanna [24]. The lower increase in the SOC content in this study was mainly due to the lower plant biomass inputs. The tropical rubber plantation ecosystem in Xishuangbanna had a higher plant biomass than the cropland in the present study. For example, the fine root biomass and litter in Xishuangbanna were 230 and 510 g m−2, respectively [24], while the root biomass and litter were only 84 and 0 g m−2 in our study. Overall, enhanced silicate weathering has great potential to promote SOC sequestration in Southwest China.

The responses of SOC and SIC contents to basalt addition at depths of 0–15 cm and 15–30 cm were different (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A high amount of basalt addition resulted in a reduction in the SIC and SOC contents and stocks under the XW100 and XW200 treatments at 0–15 cm. Basalt was added at 0–15 cm, and at a rate of 20 kg·m−2, which increased the soil weight by approximately 10%. The added basalt powder contained virtually no carbon, and this led to the increase in soil weight exceeding the increase in soil carbon. This change resulted in a decrease in SOC and SIC at 0–15 cm. The addition of the fine basalt rock powder improved aeration of the root systems, thus facilitating the vertical migration of dissolved weathering products (e.g., bicarbonate), dissolved organic carbon, water-soluble products of plant and microbial activity to 15–30 cm [25,36,37]. Due to the long-term plowing at a depth of 0–15 cm, soil aggregates are destroyed, and the clay particles are accumulated at a depth of 15–30 cm, which enhances the adsorption of dissolved organic carbon and water-soluble products by the clay particles [10,37]. In addition, the low soil pH at 15–30 cm has been demonstrated to promote the solubility of iron and aluminum oxides and calcium ions, thereby enhancing their adsorption capacity for dissolved organic carbon and water-soluble products [27,29]. These important reasons resulted in a significant increase in SIC and SOC contents at the depth of 15–30 cm.

The SOC and SIC are two important carbon pools. Due to its pivotal role in regulating ecosystem functions and mitigating global warming, the dynamics of SOC and their underlying mechanisms under different land management practices have been thoroughly addressed [38,39,40]. However, the responses of SIC to land management practices have been largely ignored in previous studies [17,41]. The results of the present study showed that the proportion of SIC stock in the total soil carbon stock is about 18% (Figure 4), suggesting that SIC is also an important carbon pool in cropland in Southwest China. Furthermore, basalt addition significantly influenced the SIC content and stock in the study area (Figure 2 and Figure 3), as predicted by An et al. [14] in a meta-analysis and Sharififar et al. [42] in Australia, South Africa and China. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the changes in the dynamics of SIC in Southwest China in future studies.

4.2. Basalt Additions Increased the Labile Organic Carbon Contents

Our results indicated that the OCF1 was the primary SOC fraction, accounting for nearly 43% at 0–30 cm (Figure 5), which is significantly higher than the value of 22% reported by Yu et al. [7] in the Songnen Palin. The differences in the OCF1 proportion were mainly due to the different determination methods used. When using the revised Walkley–Black method to measure the oxidizable organic carbon fractions, the amount of concentrated sulfuric acid used is extremely important. This study used 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid to measure the OCF1, while Yu et al. [7] only used 2.5 mL. The high amount of concentrated sulfuric acid used in the present study may have led to the high content and proportion of OCF1. The higher proportion of OCF1 at 15–30 cm than that at 0–15 cm mainly resulted from the addition of the fine basalt rock powder, which facilitated the vertical migration of dissolved organic carbon to 15–30 cm depth.

In comparison with the total SOC, the labile carbon fraction has been shown to respond with greater sensitivity to land management practices [43,44]. Consequently, it has been utilized as a significant indicator of changes in the total SOC within soils [45]. Our results indicated that basalt addition significantly increased the OCF1 content and proportion in Southwest China (Table 1 and Figure 5). The improvement in soil environmental conditions after basalt addition was the primary reason for the higher content and proportion of OCF1. Our results showed that basalt addition significantly increased the soil pH (Figure 1). Furthermore, basalt weathering could have released some essential trace elements required for plant growth [5,24,46]. This improvement in environmental conditions engendered favorable circumstances for plant growth, resulting in a 24–33% increase in plant biomass in this study, which increased the amount of organic matter entering the soil, thereby increasing the OCF1 content.

Due to the high SOC stability, responses of the stable carbon fraction to land management practices are usually neglected [11,47]. However, with the development of recent technology, some studies have found that the stable carbon fractions could also exhibit varying degrees of change in response to land management practices [40,48]. Consequently, studies investigating the changes in total SOC should fully account for variations in the stable carbon fraction [7]. Basalt addition did not affect the OCF3 content in the present study (Table 1), and the small changes in OCF3 were mainly due to the determination method used. In our study, the OCF3 was defined as the difference between the total SOC and the organic carbon oxidized by 10 mL H2SO4. The proportion of the stable carbon fraction was only around 30% (Figure 5), which is significantly lower than the traditional definition of the stable carbon fraction (which is usually more than 80%) [38,49]. That is, the measured stable carbon fraction in the present study represented the most stable fraction of SOC. Consequently, it is logical to conclude that this stable carbon fraction remained unaffected by land management practices.

4.3. Basalt Additions Reduced the Soil Organic Carbon Stability

The SOC stability is a key factor influencing soil carbon stock, and high SOC stability is more beneficial for soil carbon stock [49,50]. Variations in SOC fractions with different stabilities can, to some extent, reflect alterations in SOC stability, and a reduction in the ratio of the labile carbon content to the stable carbon content usually indicates an increase in SOC stability [13,49]. The results of the present study indicated that basalt addition significantly reduced the SOC stability, and the reduction in SOC stability at 15–30 cm was higher than that at 0–15 cm (Figure 7). The reduction in SOC stability was mainly due to the following reasons: First, the increase in plant biomass improved the inputs of labile carbon, which enhanced SOC decomposition through the priming effects [8,11], thereby reducing the SOC stability. The significant negative correlations between the OCF1 or OCF1 proportion and SOC stability also confirmed that this is the cause of the reduction in SOC stability (Figure 8). Second, the improvement in soil microbial habitat conditions (e.g., pH, soil labile carbon, soil nutrients) resulted in high microbial activity and fast microbial growth, promoting the decomposition of SOC by soil microorganisms. In addition, pH-mediated desorption of protected organic carbon was another important cause of the reduction in SOC stability [50]. The increase in soil pH in the basalt addition treatment could reduce the solubility of iron and aluminum oxides in soils, thus reducing the chemical protection of the SOC provided by iron and aluminum oxides [5,11].

The higher reduction in SOC stability at 15–30 cm than that at 0–15 cm was mainly due to the greater increases in the labile carbon fraction at 15–30 cm. Compared with the increase (12.3%) in the mean OCF1 at 0–15 cm, the increase of 46.0% at 15–30 cm was much higher under the basalt addition treatments (Table 1). In addition, the reduction in the proportion of OCF3 after basalt addition was another reason for the high reduction in SOC stability at 15–30 cm. Our results show that basalt addition increased the proportion of OCF3 by 2.9% at 0–15 cm, but it decreased by 20.3% at 15–30 cm compared to the CK (Figure 5). The large reduction in the proportion of the stable carbon fraction inevitably resulted in a large decrease in SOC stability at 15–30 cm. Generally, although basalt addition significantly increased the SOC content, it also reduced the SOC stability. Consequently, long-term monitoring of SOC responses is required to determine whether the reduction in SOC stability caused by basalt addition will offset the increase in SOC content in future studies. The findings of the present study demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the increase in soil carbon stock among the four basalt addition rates that were employed. The similar changes in soil carbon stock suggest that a high amount of basalt addition did not result in a substantial enhancement of soil carbon sequestration in comparison to the low amount of basalt addition. Therefore, it is recommended that a low basalt addition rate of 2.5 kg·m−2 be employed in order to enhance soil carbon sequestration in Southwest China in the future.

5. Conclusions

Generally, our one-year field experiment revealed some change trends of soil carbon sequestration after the addition of basalt in subtropical croplands, indicating enhanced rock weathering increased soil carbon sequestration through enhancing the SOC and SIC content and stock. The increase in SOC content was mainly due to the increase in the very labile carbon fraction resulting from the enhanced rock weathering in a one-year field experiment. Meanwhile, the increase in very labile carbon fraction resulted in a reduction in the SOC stability index under the basalt addition treatments, which indicates that enhanced rock weathering reduced the SOC stability.

The findings of the present study highlight the increase in SOC content and stock resulting from basalt addition in a one-year field experiment, proving novel information for the promising carbon dioxide removal method of enhanced rock weathering. Considering the important role of SOC in mitigating global warming, the indirect sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide by the enhanced rock weathering provided an alternative strategy for the achievement of global climate goals. However, these observed trends in changes in soil carbon were based on a one-year field experiment, and these trends will be further tested and evaluated as the experiment continues in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., M.L., C.L., S.L. and P.Y.; methodology, L.M., M.L., C.L., S.L. and P.Y.; formal analysis, S.L. and P.Y.; investigation, H.Z., Z.M., S.Z., C.W. and C.L.; resources, L.M., M.L., C.L. and S.L.; data curation, H.Z., Z.M., S.Z., C.W. and P.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M., M.L., C.L. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., Z.M., S.Z., C.W. and P.Y.; funding acquisition, L.M., M.L., C.L., S.L. and P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number U2244216, the Performance Incentive and Guidance Projects of Chongqing Scientific Research Institution, grant number CSTB2024JXJL-YFX0053 and the Open Subjects of Chongqing Institute of Geology and Mineral Resources, grant numbers CQORS-2023-2 and CQORS-2024-1.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted with the support of the Total Nitrogen-Speciation Carbon Analyzer (25A10166) and the Continuous Flow Analyzer (23A00787) of Southwest University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kattel, G.R. Climate warming in the Himalayas threatens biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and ecosystem services in the 21st century: Is there a better solution? Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 2017–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.Y.; Chen, J.; Shi, X.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Xia, J.; Zhang, L.P. Impacts of global climate warming on meteorological and hydrological droughts and their propagations. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H.D.; Weaver, A.J. Committed climate warming. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Dai, G.; Liu, T.; Jia, J.; Zhu, E.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kang, E.; Xiao, J.; et al. Understanding the mechanisms and potential pathways of soil carbon sequestration from the biogeochemistry perspective. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2024, 67, 3386–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, S.W.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, A.C.; Tang, X.G. The quantity and stability of soil organic carbon following vegetation degradation in a salt-affected region of Northeastern China. Catena 2022, 211, 105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepetiene, A.; Belova, O.; Fastovetska, K.; Dinca, L.; Murariu, G. Advances in understanding carbon storage and stabilization in temperate agricultural soils. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, X.; Chu, Y.; Wang, X. Profile storage of organic/inorganic carbon in soil: From forest to desert. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Li, Q.; Jia, H.T.; Zheng, W.; Wang, M.L.; Zhou, D.W. Carbon stocks and storge potential as affected by vegetation in the Songnen grassland of northeast China. Quat. Int. 2013, 306, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, Z.R.; Liu, W.X.; Liu, W.S.; Lal, R.; Dang, Y.P.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.L. Mechanisms of soil organic carbon stability and its response to no-till: A global synthesis and perspective. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.W.; Wang, R.T.; Yang, Y.; Shi, W.Y.; Jiang, K.; Jia, L.Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, X.; Ma, L.; Li, C.; et al. Changes in soil aggregate stability and aggregate-associated carbon under different slope positions in a karst region of Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 928, 172534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, M.Y.; Li, C.; Mao, Z.; Wang, C.; Xu, M.Z.; Zhu, D.X.; Si, H.T.; Liu, S.W.; Yu, P.J. Responses of aggregate-associated carbon and their fractions to different positions in a karst valley of Southwest China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z. Effects of land-use change on soil inorganic carbon: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2019, 353, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostie, L.; Power, I.M.; Rausis, K. Carbon dioxide supply and scaling constraints on direct air capture using calcium oxide powder. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 527, 146635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdush, J.; Paul, V. A review on the possible factors influencing soil inorganic carbon under elevated CO2. Catena 2021, 204, 105434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.F.; Zhang, R.; Cao, H.; Huang, C.Q.; Yang, Q.K.; Wang, M.K.; Koopal, L.K. Soil inorganic carbon stock under different soil types and land uses on the Loess Plateau region of China. Catena 2014, 121, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pei, J.; Fang, C.; Li, B.; Nie, M. Drought may exacerbate dryland soil inorganic carbon loss under warming climate conditions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.J.; Wang, X.J.; Zhao, Y.J.; Xu, M.G.; Li, D.W.; Guo, Y. Relationship between soil inorganic carbon and organic carbon in the wheat-maize cropland of the North China Plain. Plant Soil 2017, 418, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naorem, A.; Jayaraman, S.; Dalal, R.C.; Patra, A.; Rao, C.S.; Lal, R. Soil inorganic carbon as a potential sink in carbon storage in dryland soils—A review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Kanzaki, Y.; Lora, J.M.; Planavsky, N.; Reinhard, C.T.; Zhang, S. Impact of climate on the global capacity for enhanced rock weathering on croplands. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2023EF003698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boito, L.; Steinwidder, S.L.; Rijnders, J.; Berwouts, J.; Janse, S.; Niron, H.; Roussard, J.; Vienne, A.; Vicca, S. Enhanced rock weathering altered soil organic carbon fluxes in a plant trial. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, C.R.; Almaraz, M.; Beerling, D.J.; Raymond, P.; Reinhard, C.T.; Suhrhoff, T.J.; Taylor, L. Enhanced rock weathering for carbon removal–monitoring and mitigating potential environmental impacts on agricultural land. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 17215–17226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.T.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Vicca, S.; Goll, D.S.; Li, G.C.; Lin, L.X.; Chen, H.; Bi, B.Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, C.L.; et al. Enhanced silicate weathering accelerates forest carbon sequestration by stimulating the soil mineral carbon pump. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinwidder, L.; Boito, L.; Frings, P.J.; Niron, H.; Rijnders, J.; Schutter, A.; Vienne, A.; Vicca, S. Beyond inorganic C: Soil organic C as a key pathway for carbon sequestration in enhanced weathering. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.R.; Xiao, K.Q.; Feng, L.S. Enhanced rock weathering aids to promote carbon sequestration and yield in China’s agricultural fields. Clim. Smart Agric. 2025, 2, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoboda, P.; Doring, T.F.; Hamer, M. Remineralizing soils? The agricultural usage of silicate rock powders: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, P.; Chen, Y.; Singer, A. Ground basalt and tuff as iron fertilizers for calcareous soils. Plant Soil 1983, 73, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezanian, A.; Dahlin, A.S.; Campbell, C.D.; Hillier, S.; Öborn, I. Assessing biogas digestate, pot ale, wood ash and rock dust as soil amendments: Effects on soil chemistry and microbial community composition. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci. 2015, 65, 383–399. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C.C.; Huang, C.H. Cow dung compost and vermicompost amendments promote soil carbon stock by enhancing labile organic carbon and residual oxidizable carbon fractions in maize field soil. Soil Use Manag. 2024, 40, e13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Wang, H.Q.; Hu, J.; Shi, W.Y.; Xia, X.Y.; Sun, X.Z.; Tang, H.Y.; Huang, Y.X. Vegetation degradation reduces aggregate associated carbon by reducing both labile and stable carbon fraction in Northeast China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 654, 176789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, M.; Shamshuddin, J.; Fauziah, C.I. Improving chemical properties of a highly weathered soil using finely ground basalt rocks. Catena 2015, 124, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantzas, E.P.; Val Martin, M.; Lomas, M.R.; Eufrasio, R.M.; Renforth, P.; Lewis, A.L.; Taylor, L.L.; Mecure, J.F.; Pollitt, H.; Vercoulen, P.V.; et al. Substantial carbon drawdown potential from enhanced rock weathering in the United Kingdom. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Soil organic matter priming: The pH effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.L.; Sarkar, B.; Wade, P.; Kemp, S.J.; Hodson, M.E.; Taylor, L.L.; Yeong, K.L.; Davies, K.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I.; et al. Effects of mineralogy, chemical and physical properties of basalts on carbon capture potential and plant -nutrient element release via enhanced weathering. Appl. Geochem. 2021, 132, 105203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelland, M.E.; Wade, P.W.; Lewis, A.L.; Taylor, L.L.; Sarkar, B.; Andrews, M.G.; Lomas, M.R.; Cotton, T.E.A.; Kemp, S.J.; James, R.H.; et al. Increased yield and CO2 sequestration potential with the C4 cereal Sorghum bicolor cultivated in basaltic rock dust-amended agricultural soil. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3658–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diederich, K.M.; Ruark, M.D.; Krishnan, K.; Arriaga, F.J.; Silva, E.M. Increasing labile soil carbon and nitrogen fractions require a change in system, rather than practice. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, N.; Mandal, B.; Datta, A.; Kundu, M.C.; Rai, A.K.; Mitran, T. Stock and stability of organic carbon in soils under major agro-ecological zones and cropping systems of sub-tropical India. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 312, 107317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.M.; Zhang, S.R.; Liu, L.; Liu, J.; Ding, X. Organic fertilization increased soil organic carbon stability and sequestration by improving aggregate stability and iron oxide transformation in saline-alkaline soil. Plant Soil 2022, 474, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicca, S.; Goll, D.S.; Hagens, M.; Hartmann, J.; Janssens, I.A.; Neubeck, A.; Penuelas, J.; Poblador, S.; Rijnders, J.; Sardans, J.; et al. Is the climate change mitigation effect of enhanced silicate weathering governed by biological processes? Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharififar, A.; Minasny, B.; Arrouays, D.; Boulonne, L.; Chevallier, T.; Van Deventer, P.; Field, D.J.; Gomez, C.; Jang, J.J.; Jeon, S.H.; et al. Soil inorganic carbon, the other and equally important soil carbon pool: Distribution, controlling factors, and the impact of climate change. Adv. Agron. 2023, 178, 165–231. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.J.; Liu, S.W.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhou, D.W. Selecting the minimum data set and quantitative soil quality indexing of alkaline soils under different land uses in northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Lavallee, J.M. Soil organic matter formation, persistence, and functioning: A synthesis of current understanding to inform its conservation and regeneration. Adv. Agron. 2022, 172, 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nyabami, P.; Weinrich, E.; Maltais-Landry, G.; Lin, Y. Three years of cover crops management increased soil organic matter and labile carbon pools in a subtropical vegetable agroecosystem. Agrosyst. Geosci. Environ. 2024, 7, e20454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, W.; Hasemer, H.; Sokol, N.W.; Rohling, E.J.; Borevitz, J. Applying minerals to soil to draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide through synergistic organic and inorganic pathways. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Mehmood, I.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Jia, R.; Gui, H.; Blagodatskaya, E.; Xu, X.L.; Smith, P.; Chen, H.Q.; Zeng, Z.H.; et al. Not all soil carbon is created equal: Labile and stable pools under nitrogen input. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Zhao, J.; Dou, Y. Fungal necromass carbon contributes more to POC and MAOC under different forest types of Qinling Mountains. Plant Soil 2025, 512, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.J.; Li, Y.X.; Liu, S.W.; Liu, J.L.; Ding, Z.; Ma, M.G.; Tang, X.G. Afforestation influences soil organic carbon and its fractions associated with aggregates in a karst region of Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 152710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; He, H.; Cheng, W.; Bai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Factors controlling soil organic carbon stability along a temperate forest altitudinal gradient. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.