Abstract

Tomato production is a strategic horticultural sector in Europe, yet it is increasingly exposed to climate variability, input-price volatility, and structural heterogeneity among national production models. This study provides a macro-level, cross-country assessment to benchmark structural performance and derive country typologies of tomato systems in 15 European countries over 2015–2024 using harmonized public statistics on cultivated area, production, and derived yields. A Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE)—informed interpretive lens is used to frame yield level and interannual yield variability as transition-relevant performance signals, while acknowledging that farm- and territory-level TAPE scoring cannot be replicated with aggregated national data. The analysis combines descriptive benchmarking, trend-adjusted yield stability metrics, area–production relationship diagnostics, and multivariate classification (principal component analysis and Ward hierarchical clustering) to identify coherent national performance profiles. Results show pronounced cross-country contrasts and three recurring macro-patterns: (i) high-yield, low-dispersion systems with stable trajectories; (ii) transitional systems with lower yields and broader distributions; and (iii) high-dispersion systems indicating structural or climatic instability. The resulting typology supports differentiated policy discussion on adaptation, modernization priorities, and transition enabling conditions, and highlights the need to link macro-statistics with comparable agroecological indicators at farm and regional scale for stronger inference on transition pathways.

1. Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) production systems are among the most widespread and economically relevant horticultural sectors in Europe and neighbouring regions, supplying fresh and processed commodities to domestic and export markets and supporting regional and national economies, employment and regional value chains [1,2,3]. In addition to their economic relevance, tomatoes are among Europe’s most important vegetable crops in terms of harvested area and production volume; according to Eurostat, annual tomato production is on the order of 16.8 million tonnes on 208.43 thousand ha, in recent years [4]. Across Europe, tomato cultivation and production contexts are heterogeneous, spanning open-field systems, unheated protected structures, climate-controlled greenhouses, and soilless/hydroponic systems, each characterized by distinct microclimate management, nutrient regimes, planting densities, input profiles, and risk exposure, which collectively shape yield levels, stability outcomes, and cost structures [5,6,7]. Beyond production volume, tomatoes have high relevance for food systems through their nutritional and market value, which further increases the need for continuity of supply and stability of production under climate stress and market volatility. These considerations are especially important when linking production performance to sustainable food systems objectives and transition-oriented policy discussions [8,9,10,11]. This diversity also implies that simple yield rankings can mask structurally different production models; therefore, performance assessment should be interpreted alongside indicators of yield variability and structural coupling between area and output [12]. The contrast between technologically intensive protected systems (e.g., greenhouse-dominant profiles in Western Europe) and more open-field or transitional profiles (e.g., parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, including Romania) is especially relevant for cross-country interpretation and policy design [13].

Climate variability and intensifying extreme events, e.g., heat stress, water scarcity, irregular precipitation, heavy rain, extreme hail events, etc., increasingly challenge tomato productivity and yield stability, particularly in water-limited regions and in systems with high dependence on microclimate control. This motivates cross-country evidence on not only average yields but also interannual dispersion as an early warning signal of instability at national scale [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Because tomatoes contribute substantially to the continuity of fresh supply and processing chains, increased yield instability can translate into price volatility, supply disruptions, and higher dependence on imports, outcomes that directly affect food-system resilience and affordability [21]. At the same time, conventional intensification, often relying on synthetic fertilizers, pesticide-dependent protection, and energy-intensive climate control, raises concerns regarding environmental impact and long-term sustainability, especially under climate stress and volatile input prices. This creates a policy-relevant tension between short-term productivity goals and longer-term sustainability objectives in horticultural value chains [22,23,24,25,26,27]. If yield growth stagnates while demand remains stable or increases, maintaining supply would require either expanding cultivated area (often constrained by land and water availability) or increasing external sourcing, both of which can amplify environmental pressures and economic vulnerability.

Agroecology has emerged as a scientific, practical, and policy framework for redesigning agricultural systems to enhance resilience, resource-use efficiency, biodiversity and ecosystem services, and social well-being while maintaining viable production. In Europe, agroecological transition is also increasingly framed as a governance and policy challenge, not only a technical one [28,29,30,31]. FAO frames agroecology through the “10 Elements of Agroecology” as a structured entry point for guiding and assessing transition trajectories, while the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE-FSN) emphasizes agroecological approaches as pathways to sustainable food systems that integrate biophysical and socio-economic dimensions. The framing is relevant for horticultural value chains because resilience and input-use efficiency must be addressed alongside market continuity and environmental performance [32]. This framing is especially relevant for tomatoes, where pest and disease pressures, input intensity, and climate sensitivity make transition options strongly context-dependent [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. To support evidence-informed transition pathways, FAO developed the Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE), a framework intended to characterize agroecological transitions and assess performance in a multidimensional way across production, environment, social, and economic dimensions. Even if TAPE cannot be applied in full to country-level datasets, it provides a useful way to interpret performance patterns by considering the broader production context.

In this study, we apply a TAPE-informed lens at national scale: we do not compute a standardized TAPE score, but interpret yield level, interannual yield variability (as a partial stability/resilience proxy), and structural typologies as macro performance signals that can guide hypotheses about transition-relevant configurations and policy needs, while explicitly avoiding causal claims based on ecological (country-level) data [42,43,44,45]. This approach is designed to improve interpretability beyond simple yield rankings, by distinguishing between high performance associated with structurally different production configurations and by flagging instability as a potential risk signal, including for transitional contexts such as Romania. On the European scale, tomato systems are heterogeneous, and cross-country comparisons often remain limited to descriptive rankings without a transition-oriented interpretation. Conversely, many agroecology assessments focus on local practice measurement and participatory processes with limited comparability across countries. This creates a gap for EU-scale evidence that is both comparable and interpretable through a transition framework, with direct relevance for differentiated policy targeting and rural development instruments [46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Romania is relevant in this context as a representative transitional profile within the European tomato sector, where competitiveness and profitability in tomato cultivation depend strongly on structural conditions, support schemes, and modernization constraints that interact with both transition opportunities and vulnerabilities. Importantly, such transitional contexts contrast with more technologically stabilized systems, where protected cultivation and integrated value chains can buffer climatic and market shocks, and with highly specialized open-field systems where scale, irrigation infrastructure, and market integration shape performance and stability [53]. Therefore, Romania provides a useful reference point for interpreting transitional profiles within the EU macro typology [53,54,55,56,57,58].

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to provide a TAPE-informed, cross-country assessment of European tomato production systems over 2015–2024, focusing on (i) cultivated area and production dynamics, (ii) mean yield performance and yield distribution structure, (iii) interannual yield variability as a stability signal, (iv) the coupling between cultivated area and production as a structural proxy, and (v) multivariate typologies summarizing coherent performance profiles. By combining these dimensions, the study moves beyond descriptive rankings to support a transition-oriented interpretation of macro performance signals, while remaining within the limits of country-level data and avoiding causal inference. The contribution is policy-relevant in the context of differentiated support needs: systems characterized by stable high yields may require transition instruments oriented toward resource efficiency and sustainability, while systems with high variability may require targeted adaptation, risk management, and transition-enabling measures [22,24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and TAPE-Informed Analytical Lens

This study conducts a macro-level, cross-country assessment of European tomato production systems over 2015–2024, combining productivity and stability metrics with contextual descriptors of farming-system orientation. We use FAO’s agroecology framework and TAPE to help interpret country-level trends in yield and yield variability. We do not calculate full TAPE scores because we work with national statistics rather than farm-level data. Therefore, no standardized farm-level TAPE scoring was performed; instead, transition-relevant descriptors (where available) are treated as contextual proxies to support interpretation. Accordingly, the analysis is explicitly descriptive and comparative, and the reported associations are not interpreted causally at the country level.

2.2. Data Sources, Country Coverage, and Variable Construction

The dataset covers 15 countries (Albania, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Spain, and Türkiye, Figure 1) for the period between 2015 and 2024. Annual tomato cultivated area (ha) and production (tonnes) were extracted primarily from Eurostat and complemented, where necessary, with FAOSTAT and national statistical reports to address missing values or reporting gaps [59]. The period 2015–2024 was selected to maximize cross-country completeness within a consistent post-2015 reporting window while capturing recent variability under increasing climatic and market pressures. The country set reflects the intersection of (i) data availability for the full period and (ii) representation of contrasting production orientations, including open-field and protected cultivation profiles across Europe and neighboring countries (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of countries included in the agroecology cross-country analysis (2015–2024).

Table 1.

Data sources and variables included in the analysis.

Tomato yield was computed as production per unit area (Y = P/A), using consistent units across countries and years. When national reporting used kg/m2 as measuring units, values were harmonized to t/ha for comparability (conversion details are provided in Supplementary Materials S1). All calculations were performed on annual national aggregates; therefore, within-country heterogeneity (e.g., open-field versus protected cultivation shares) is not directly observed in the core yield series and is addressed only through contextual descriptors where available.

To support the TAPE-informed interpretation, additional descriptors were compiled where consistently available (e.g., irrigation coverage, protected cultivation indicators, and transition-related descriptors such as organic area share or documented IPM/rotation/soil-health measures). Because these descriptors are not uniformly reported across all countries and years, they are treated explicitly as contextual variables and not interpreted to generalize conclusions. Where descriptors were unavailable or not comparable, they were not imputed, and interpretation remains anchored in the harmonized area–production–yield series.

2.3. Analytical Workflow and Alignment with Research Questions

The analytical workflow follows five steps: (i) descriptive cross-country profiling of area, production, and yield; (ii) yield distribution, dispersion, and stability assessment; (iii) association between cultivated area and production (area–output coupling); (iv) multivariate classification of structural performance models (PCA and clustering); and (v) exploratory analysis of yield-related correlates using available techno-environmental proxies. The correspondence between research objectives and analytical methods is summarized in Table 2. To improve transparency, step (ii) includes both conventional dispersion metrics and trend-adjusted instability indices, and step (iii) includes both parametric and non-parametric correlation together with formal specification checks.

Table 2.

Research objectives and corresponding analytical methods.

The workflow is designed for cross-country comparability while acknowledging the constraints of ecological (country-level) inference and heterogeneous production contexts.

2.4. Statistical Environment and Reporting Conventions

Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics (v29.0) and Microsoft Excel 365. Summary statistics and visualizations are reported to support descriptive comparison across countries and years. Where p-values are reported (e.g., correlations, regressions), they are interpreted as supportive statistical evidence rather than strict hypothesis testing, given the country-level design, potential unobserved confounding, and heterogeneous production models. Where alternative specifications were compared (e.g., linear vs. quadratic), model selection was guided by formal specification testing (RESET) and information criteria (AIC/BIC), reported to support transparency rather than model “truth” claims.

2.5. Descriptive Profiling and Yield Distribution Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize cultivated area, production, and yield by country and year (means, ranges, standard deviations, and confidence intervals). Yield distributions were examined using histograms to characterize dispersion patterns, identify extreme values, and support later interpretation of structural typologies (e.g., compact vs. highly dispersed yield regimes). Distribution diagnostics were interpreted descriptively; the primary stability assessment is reported through complementary variability and instability indices (Section 2.6).

2.6. Yield Variability and Stability Indicators

To evaluate yield variability and stability, we first computed the coefficient of variation (CV%) as a descriptive measure of relative dispersion in annual yields. Because CV% does not separate random variability from long-term deterministic trends, we complemented it with two agricultural time-series instability metrics: the Cuddy–Della Valle (CDV) index (trend-adjusted instability) and the Coppock Instability Index (CII) (year-to-year volatility based on logarithmic changes). Together, CV%, CDV, and CII provide a more robust characterization of yield stability than CV% alone, supporting interpretation of structural instability and short-term shocks under national aggregation. Full definitions and mathematical expressions are provided in Supplementary Materials S1. In the TAPE-informed interpretation, lower yield dispersion and more stable trajectories are treated as transition-relevant performance signals (as partial proxies for resilience), acknowledging that resilience is multidimensional and not fully captured by yield statistics alone. The CV%, CDV and CII definitions are provided in Supplementary Materials S1.

2.7. Area–Production Association (Area–Output Coupling)

To provide a comprehensive assessment of the relationship between total tomato production and total cultivated area, the analysis was extended through a stepwise framework combining parametric and non-parametric association measures, together with formal model-specification testing and information-criterion comparisons across alternative model forms. In a first step, Pearson (r) and Spearman (ρ) correlation coefficients were computed for each country using the 2015–2024 time series. Whereas Pearson’s r assumes a linear relationship and approximately normal distributions, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was implemented as a non-parametric measure of monotonic association, computed on ranked values (with tied observations assigned average ranks), thereby reducing sensitivity to non-normality and to departures from strict linearity; the formal definition and computation details are provided in Supplementary Materials S1. The absolute difference between the two coefficients (|r − ρ|) was used as a preliminary indicator of the stability of the linearity assumption. Where time series were constant or exhibited insufficient temporal variation, correlation estimates, and formal specification tests were not computed and are reported as not applicable (NA).

In a second step, for countries with sufficient temporal variation, linear regression models of production as a function of area were estimated and subjected to the Ramsey RESET (Regression Specification Error Test). This test evaluates the null hypothesis of correct functional specification; rejection suggests potential nonlinearities and/or omitted variables. In parallel, to complement the specification tests, alternative nonlinear (quadratic) models were estimated, and their performance was compared against the linear models using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). A nonlinear specification was considered preferable when it yielded lower AIC/BIC values and/or when the RESET test rejected the linear specification.

Overall, this combined approach provides a formal verification of the linearity assumption and supports a differentiated interpretation of functional form according to the empirical structure of the data for each analyzed country. Because the dataset is a short country-level time series (n = 10 years per country), the Pearson–Spearman comparison, RESET, and AIC/BIC are used as robustness-oriented diagnostics rather than as a basis for estimating country-specific nonlinear production functions. The linear specification is retained as the common reference for cross-country comparability, while potential nonlinearities are discussed qualitatively and reflected in the typology and instability metrics.

In addition, a simple pooled OLS regression model (production ~ area) was fitted as a transparent descriptive scaling model to contextualize cross-country differences and highlight outliers (e.g., high output with limited area in protected-cultivation contexts). Full mathematical expressions and model specification notes are provided in Supplementary Materials S1.

2.8. Exploratory Analysis of Yield-Related Correlations

An exploratory multiple regression (OLS) was used to examine associations between yield outcomes and a limited set of macro-level explanatory proxies selected for agronomic relevance and data feasibility, including climatic descriptors (e.g., temperature/precipitation summaries or anomaly proxies where available), irrigation/protected cultivation indicators, and available transition-related descriptors (e.g., organic area share or reported IPM/rotation indicators). Given the small country sample (n = 15) and the risk of collinearity among national structural variables, the model is treated as exploratory, emphasizing coefficient direction, relative magnitude (standardized coefficients), and diagnostics (e.g., VIF) rather than causal attribution. Because the data are country-level aggregates, results are interpreted as ecological associations; robustness is limited by potential unobserved confounding and by the inability to control for within-country production-structure heterogeneity (e.g., open-field vs. protected cultivation shares). Regression equations and diagnostic definitions are provided in Supplementary Materials S1.

2.9. Multivariate Classification of Structural Performance Patterns

To identify structural patterns in tomato yields and to classify countries according to agricultural performance, technological stability, and climatic exposure, the study applied a combined framework based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering, complemented by standard statistical validation metrics. The combined PCA–clustering workflow was supported by standard adequacy and validation metrics to assess (i) dataset suitability for dimensionality reduction and (ii) the stability and structural relevance of the resulting groupings. The PCA was preceded and supported by statistical adequacy tests, which confirm the presence of meaningful correlations among variables and the appropriateness of dimensionality reduction:

- (a)

- Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index evaluates the proportion of common variance among variables relative to total variance.

- (b)

- Bartlett’s test of sphericity tests the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix. Dataset suitability for factor-type multivariate analysis was evaluated in accordance with standard methodological recommendations for agri-economic applications. Interpretation thresholds followed common guidelines (KMO > 0.60 indicates adequacy; p < 0.05 indicates statistical significance).

- (c)

- Cumulative explained variance was used to determine the proportion of overall yield variability captured by the first principal components. PCA results are reported through eigenvalues, component loadings, and cumulative explained variance for retained components, enabling interpretation of the latent axes and their contribution to cross-country yield differences.

For clustering, validation focused on internal coherence and separability of the groups. To classify countries into homogeneous groups in terms of agricultural performance, hierarchical clustering was applied using Ward’s method and squared Euclidean distance, which minimizes the increase in total within-cluster variance at each agglomeration step. The optimal number of clusters was determined by dendrogram inspection and by identifying critical thresholds in the agglomeration distance. Cluster validity was additionally assessed through consistency with the PCA score-space configuration (countries close in PCA space belonging to the same cluster) and through inspection of cluster separability in the reduced-dimensional representation.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Overview of European Tomato Production Systems (2015–2024)

Across 2015–2024, cultivated tomato area shows pronounced cross-country heterogeneity among the 15 analyzed countries. The largest cultivated areas are observed in Mediterranean producers, particularly Türkiye, Italy, and Spain, consistent with a structurally land-extensive contribution to national tomato sectors. In contrast, several Northern and Western countries (e.g., the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark) operate with very small, cultivated areas in national statistics, indicating production profiles where national output is not driven by land expansion and where protected cultivation and higher technological intensity likely play a larger role under national aggregation. An intermediate group (e.g., Romania, Portugal, Greece, Poland) shows moderate cultivated areas with mixed national profiles. For countries with extremely small and nearly constant cultivated areas (notably Denmark and Ireland), the limited time-series variability constrains the interpretability of distribution- and correlation-based diagnostics at national scale. Total production broadly follows a comparable gradient, with Türkiye and Italy remaining the largest producers and Spain also contributing substantially. The Netherlands achieves comparatively high national output relative to cultivated area, indicating a high-output structural configuration under country-level aggregation. These contrasts underline that cross-country comparisons reflect structurally different production orientations (open-field vs. protected systems) and should be interpreted accordingly. Overall, the descriptive patterns indicate a polarized European tomato sector, with marked differences in structural scale and interannual behavior across countries.

3.2. Comparative Yield Analysis (2015–2024): Mean Performance, Variability, and Area–Production Coupling

Mean yield (2015–2024), variability (standard deviation), 95% confidence intervals, and ranking across the 15 countries were calculated (Table 3). the Netherlands and Belgium present the highest mean yields, while Romania and Serbia show the lowest values. Ireland and Denmark also appear high in the ranking; however, because their cultivated areas are extremely small and nearly constant at national scale, yield ratios and dispersion diagnostics should be interpreted cautiously for cross-country comparisons and should not be treated as structurally comparable to larger-scale national sectors.

Table 3.

Mean tomato yields (t/ha), variability, confidence intervals and ranking (2015–2024).

To assess yield stability, we first used the coefficient of variation (CV%). However, CV% does not account for deterministic time trends; therefore, the analysis was extended by incorporating the Cuddy–Della Valle (CDV) index and the Coppock interannual instability index. These indices are widely used in agricultural economics to capture trend-adjusted instability and year-to-year volatility, respectively, both of which are relevant for characterizing agricultural risk.

It can be observed that for Albania, Belgium, and Türkiye, the CV% values are relatively moderate, but the CDV values are substantially lower, indicating that a substantial part of the observed variability is explained by structural trends rather than by “true” instability. Among countries with high structural instability, Romania, Poland, Greece, and Serbia—show high CDV and Coppock values, indicating yields that are sensitive to climatic and technological shocks and characterized by persistent instability. In contrast, countries with comparatively stable yields include Italy, Spain, Germany, and Albania, where low values of both indicators are consistent with more mature production systems and higher technological stabilization.

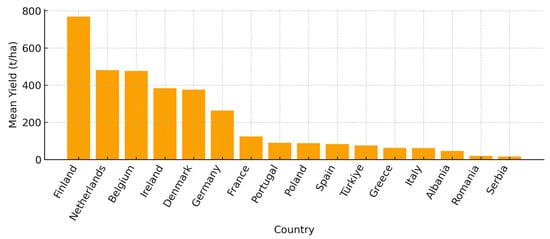

The cross-country differences in mean tomato yield (t/ha) over 2015–2024 (Figure 2) highlight the steep gradient between the highest- and lowest-performing national profiles. The distribution of mean yields is strongly heterogeneous, with a small number of countries positioned at very high values and the majority clustered at moderate-to-low values. The strong contrast between very high-yield profiles and low-yield profiles across the mentioned period supports a clear stratification of national yield levels in the dataset, while also showing that some countries display large uncertainty ranges (wide confidence intervals) relative to others.

Figure 2.

Mean tomato yield (t/ha) by country over 2015–2024 (n = 10 years), based on annual yields computed from national production and cultivated area statistics. Countries are ordered by mean yield.

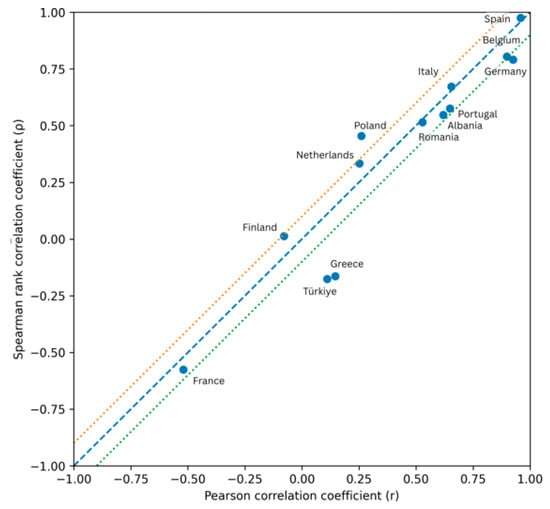

In the context of agricultural time series, production dynamics are often influenced by climatic, technological, and structural factors that may generate nonlinear or monotonic relationships rather than strictly linear ones. To address this methodological limitation and to test the robustness of the results, the analysis calculated both Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. This enabled an assessment of the nature of the relationship between variables by using the absolute difference between the two coefficients, |r − ρ|, as a preliminary indicator of the stability of the linearity assumption. When Pearson and Spearman coefficients are close in both magnitude and sign, the relationship between variables can be considered predominantly linear or, at minimum, monotonic without major structural deviations. In such cases, the use of linear regression is justified statistically and economically, providing a coherent and transparent interpretative framework. Conversely, when substantial differences between Pearson and Spearman coefficients are observed, this is interpreted as evidence of nonlinear components in the relationship under analysis. For these cases, the methodological approach requires exploring nonlinear regression models (e.g., logarithmic, polynomial, or other functional forms), selected according to the degree and shape of the identified nonlinearity. Accordingly, regression specifications are adjusted to better reflect the empirical structure of the data and the underlying agro-economic mechanisms.

To evaluate whether the relationship between cultivated area and production is adequately described by a linear model, or whether it includes significant nonlinear components, the analysis was further extended by applying formal model specification tests and information criteria to compare alternative model forms.

The results summarized in Table 4 indicate substantial heterogeneity in the production–area relationship across Europe, confirming that imposing a single functional specification for all countries would be methodologically inappropriate. For countries such as Spain, Romania, Albania, Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Portugal, Pearson and Spearman coefficients are close in both magnitude and sign, and the RESET test does not indicate systematic specification errors; therefore, linear regression is adequate—with the additional observation that Spain shows very high correlations and consistent Pearson–Spearman results, without evidence of misspecification. Moreover, linear models display AIC and BIC values that are lower than or comparable to those of the nonlinear specifications. These findings suggest that expansions or contractions in cultivated area translate in a relatively proportional manner into changes in production, supporting the use of linear regression.

Table 4.

Yield instability indicators for tomato production (2015–2024).

By contrast, for Poland, Germany, France, Greece, and Türkiye, discrepancies between Pearson and Spearman coefficients are more pronounced, and the RESET test and AIC/BIC criteria indicate a superior nonlinear specification. In these cases, production does not respond proportionally to changes in cultivated area, being influenced by factors such as technological intensity, farm structure, the role of production in protected cultivation systems, or climatic constraints. In particular, Poland exhibits a clearly nonlinear relationship, convergently confirmed by all robustness checks, which supports the use of quadratic (or, where relevant, logarithmic) specifications. For Denmark and Ireland, time series are constant or lack sufficient variability, making correlation estimation and formal testing impossible; excluding them is methodologically justified and does not affect the general conclusions of the analysis.

The comparative graphical representation of Pearson (r) and Spearman (ρ) coefficients provides a visual and analytical assessment of the robustness of the linearity assumption in the relationship between cultivated area and tomato production (Figure 3). The positioning of points relative to the reference diagonal r = ρ and to tolerance bands of ±0.10 enables identification of the dominant association type for each country. Countries located close to the diagonal and within the ±0.10 bands (e.g., Spain, Italy, Romania, Belgium) show very similar r and ρ values. This indicates that the dependence between production and area is predominantly linear and stable, and that rank ordering is consistent with linear variation. In these cases, the use of linear regression (OLS) is methodologically justified without significant information loss.

Figure 3.

Pearson vs. Spearman correlation coefficients for the production-cultivated area relationship (2015–2024).

Points located at a substantial distance from the diagonal (e.g., Poland, Greece, Türkiye) signal discrepancies between linear and rank-based correlation. This configuration suggests the presence of a monotonic but nonlinear relationship, where changes in cultivated area do not translate proportionally into changes in production. For France, r and ρ are low or negative, indicating a decoupling of production from cultivated area. This pattern is consistent with agricultural restructuring and technological intensification, where cultivated area may decline while production is maintained or optimized.

Overall, the plot confirms that the linearity assumption is not universally valid for all analyzed countries. Although Pearson–Spearman comparisons and specification tests indicate cross-country differences in the functional form of the production–area relationship, using a linear regression model as a common reference specification across all countries remains methodologically justified for the following reasons. First, linear regression provides a first-order approximation of any continuous functional relationship; even under nonlinearity, it captures the average marginal effect of area on production, offering a clear and comparable economic interpretation. Second, for most countries, Pearson–Spearman differences are moderate, indicating a stable monotonic relationship; in such settings, linear regression provides consistent estimates of the direction and average magnitude of association, even if the exact functional form varies marginally across states. Third, given the relatively short time series available (2015–2024), fitting distinct nonlinear models for each country would reduce degrees of freedom and increase coefficient instability, while complicating replication and comparability. Finally, cross-country comparability is a central objective of the analysis: using a single linear specification enables direct coefficient comparisons, avoids fragmented interpretations, and supports benchmarking across national tomato production systems. Instead of relying on heterogeneous functional forms, potential nonlinearities are captured indirectly through structural variables (e.g., protected cultivation, yield levels), climatic factors, and instability indicators—thus introducing complexity through explanatory content rather than through mathematical specification, while maintaining model transparency.

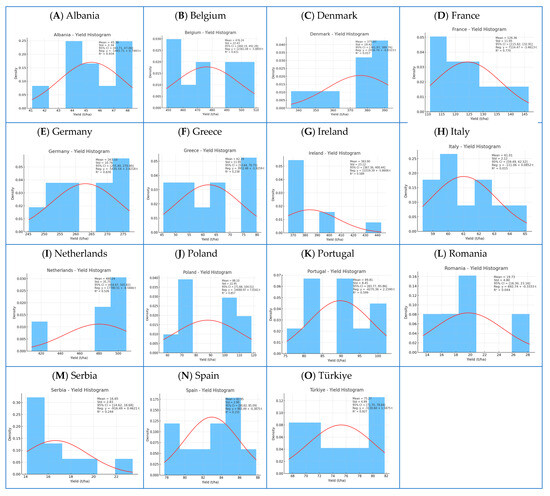

Yield histograms (Figure 4) illustrate cross-country differences in distribution shape and dispersion over 2015–2024. Several countries exhibit compact distributions (narrow interannual dispersion), whereas others show broader and/or more asymmetric distributions with longer tails, indicating higher dispersion and the presence of outlier years in the decade. For countries with extremely small or near-constant cultivated area series, histogram interpretation is limited because yield ratios can be sensitive to small denominator effects. These histograms provide an additional view of distribution shape and dispersion patterns across the decade. Several countries (e.g., Belgium, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain) exhibit compact distributions, indicating comparatively lower interannual dispersion in yield. A second set (e.g., Romania, Albania, Serbia, Poland) displays broader and less symmetric distributions, consistent with higher dispersion and/or asymmetric variation. Wider and more irregular distributions are visible for Greece, and to a degree the Netherlands, indicating greater dispersion and longer tails under national aggregation. Denmark and Ireland show flat or non-informative distributions due to extremely small and constant cultivated areas. Türkiye presents a relatively compact national distribution in this dataset, noting that national aggregation may mask internal regional variability.

Figure 4.

Yield distribution (histograms) by country for 2015–2024. Each histogram represents the distribution of annual national yields (t/ha) across the 10-year period, illustrating differences in dispersion and distribution shape across countries.

Based on the combined descriptive evidence from mean yield levels previously described dispersion patterns (SD/CI 95 and histogram structure), and area–production coupling, Table 5 summarizes a typology of structural profiles as an operational synthesis of macro-patterns. This typology is used for subsequent transition-oriented interpretation and does not imply causal attribution.

Table 5.

Structural models of European countries in the tomato cropping system.

3.3. PCA and Cluster Analysis of Yield Profiles Across Countries

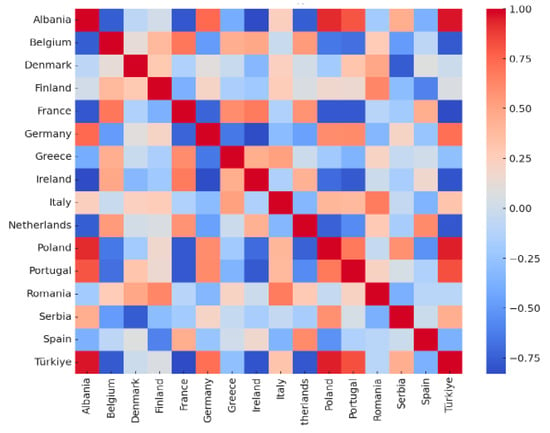

Multivariate analyses (pairwise yield-correlation heatmap, PCA, and hierarchical clustering) provide a consolidated view of similarity patterns among national yield profiles and support the differentiation suggested by descriptive outputs.

The heatmap of pairwise yield correlations (Figure 5) indicates groups of countries with similar yield trajectories over 2015–2024, as well as countries with divergent temporal behavior. Correlations were computed on annual national yields (t/ha) over the 10-year window; therefore, similarity reflects co-movement patterns in aggregated yield dynamics rather than within-country production-structure homogeneity.

Figure 5.

Heatmap, correlation of tomato yields across countries.

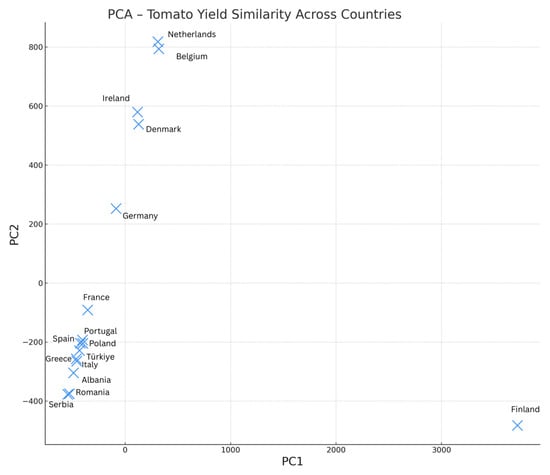

The PCA representation (Figure 6) reduces the dimensionality of the 2015–2024 yield panel and separates countries according to dominant gradients in yield behavior across the decade. Countries positioned closer to one another show higher similarity in their yield trajectories, whereas distant positions reflect contrasting profiles.

Figure 6.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA). Structural similarities in yield profiles.

PCA was applied to the standardized matrix of annual mean tomato yields (t/ha) to reduce data dimensionality and to highlight the latent factors governing structural differences among countries. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure was KMO = 0.73, indicating good sampling adequacy for factor-type analysis and supporting the appropriateness of dimensionality reduction. This result suggests that cross-country yield variability is driven by common underlying factors (technological, climatic, and structural), thereby justifying the use of PCA.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 ≈ 112.4; p < 0.001), confirming the presence of systematic correlations among tomato yields across the analyzed countries. Accordingly, inter-country differences are not random, but reflect distinct production structures that can be summarized through latent components.

Based on the Kaiser criterion, PCA revealed a clear factorial structure dominated by two principal components that together explain 78.6% of total variance, capturing the fundamental mechanisms underlying yield differences across countries.

Principal Component 1 (PC1), explaining approximately 52.4% of total variance, is strongly and positively associated with high and stable yield levels and reflects technological development and agricultural intensification. Countries with high scores on this axis are typically characterized by extensive use of protected production systems (greenhouses and plastic tunnels), advanced irrigation infrastructure, standardized production inputs (high-performing hybrids, controlled fertilization), integrated value chains, and a strong commercial orientation.

Principal Component 2 (PC2), explaining approximately 26.2% of variance, is associated with climatic variability and structural instability. High or extreme scores on this axis are linked to pronounced interannual yield volatility, exposure to heat stress, drought, or limiting seasonality, dependence on external climatic conditions, or fluctuating energy costs. Countries positioned at the extremes of PC2 reflect production systems that are vulnerable to climatic or structural shocks, even when technological levels are relatively high. This separation confirms that agricultural performance is not determined solely by technology, but also by the climatic resilience of the production system, and supports the interpretation of PCA as a tool for distinguishing between mature, transitional, and vulnerable agricultural systems.

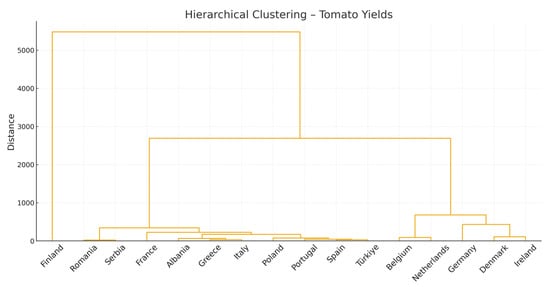

Ward hierarchical clustering (Figure 7) groups countries based on similarity in yield profiles and interannual dispersion and indicates a limited number of coherent clusters.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical clustering. Grouping countries by agricultural performance.

The clusters identified through hierarchical classification show high internal homogeneity, confirming that grouped countries share similar profiles in terms of yield level and variability. Dendrogram inspection indicates a pronounced jump in agglomeration distance at approximately 11–14, which supports the allocation into three distinct clusters. Below this threshold, clusters remain compact and homogeneous, whereas above it, aggregations become forced and lose structural meaning. The three clusters correspond to: high-performing and stable agricultural systems, systems undergoing technological transition, and systems that are climatically or structurally vulnerable. The validity of this classification is further supported by the convergence between the PCA and clustering results. Countries positioned close to each other in the PCA space belong to the same hierarchical cluster, and structural outliers, as Greece, are consistently identified by both methods. This convergent validation indicates that the resulting typologies are not statistical artefacts, but reflect real structural differences among the analyzed agricultural systems.

An additional validation criterion is the conceptual overlap between countries’ positioning in the PCA space and their membership in hierarchical clusters. Based on Figure 4 and Figure 5, high-performing Western European countries cluster compactly in the PCA space and belong to the same hierarchical group, transitional Eastern European countries occupy intermediate positions, while Greece emerges as a structural outlier; these are patterns that confirm the interpretative validity of the multivariate analyses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpreting National Yield Patterns Through a TAPE-Informed Lens

This study provides a macro-level benchmarking of European tomato production systems (2015–2024) and interprets cross-country performance patterns using a TAPE-informed lens. Consistent with the FAO agroecology framing (10 Elements) and TAPE’s emphasis on multidimensional performance, the results highlight that tomato systems differ not only in mean yield levels, but also in the structure of yield distributions, interannual dispersion, including trend-adjusted instability signals and the degree of coupling between cultivated area and national output. These complementary signals are important because variability may reflect both short-term shocks and longer-term structural dynamics, which have different implications for resilience-oriented transition strategies. At national scale, these performance signals do not constitute a full TAPE assessment; nevertheless, they offer a structured way to interpret transition-relevant contrasts in productivity and stability outcomes and to formulate policy-relevant hypotheses about where and why differentiated support may be needed [24,28,29,30,34,37].

A key contribution of this work is the separation between (i) descriptive performance signals observed in national statistics (yield levels, dispersion metrics, area–production coupling), and (ii) transition-oriented interpretation grounded in agroecology. This separation is important because national aggregates are shaped by heterogeneous internal regions and production models (open field, protected cultivation, mixed marketing channels) and because country-level data do not allow strong causal attribution to specific practices. In addition, countries with extremely small and near-constant cultivated areas may generate yield ratios that are sensitive to denominator effects; therefore, high rankings based on national aggregates should be interpreted cautiously in such cases. Therefore, the discussion below uses cautious language and frames observed differences as patterns consistent with certain structural configurations, rather than direct evidence of specific drivers [27,29,34,37,39].

4.2. Structural Stratification of Yield Levels and “Stability Signals”

The cross-country ranking of mean yields (Table 3) shows strong stratification, with a small number of very high-yield national profiles and a broader group of moderate-to-low yield profiles. In a TAPE-informed interpretation, mean yield is only one performance dimension; interannual dispersion (SD/CV%) and distribution shape add a complementary perspective by indicating whether performance is stable or highly variable over time. To strengthen robustness, the stability assessment also incorporates trend-adjusted and interannual instability indices (Cuddy–Della Valle and Coppock), which help distinguish volatility from deterministic yield trends. Countries with compact yield distributions and relatively narrow dispersion ranges may be interpreted as exhibiting higher stability under national aggregation, whereas broader distributions and longer tails indicate greater interannual fluctuation and higher sensitivity to episodic deviations during the decade [11,29,30]. Where CV% is moderate but CDV is substantially lower, a larger share of variability is attributable to underlying trends rather than to “true” instability; conversely, high CDV and Coppock values indicate persistent structural instability and elevated agricultural risk.

At macro level, these differences may reflect combinations of climate exposure, production infrastructure, and management orientation, including access to irrigation, the prevalence of protected cultivation and technology intensity, and the presence of transition-supportive management and governance conditions. Importantly, because this study does not compute farm-level TAPE indicators, these are framed as plausible structural correlates rather than measured drivers. From an agroecology perspective, stability signals are particularly relevant because resilience is a core agroecology element and a central aim of transition pathways under climate variability [4,11,12,30].

4.3. Area–Production Coupling as a Structural Proxy (Not a Causal Indicator)

The area–production correlations (Table 4) show that countries differ substantially in the alignment between cultivated area and national output over time. Very strong positive correlations suggest that fluctuations in national production co-vary with cultivated area within the decade, which is consistent with national profiles where land allocation changes are a major observable component of output variation. Weak or negative correlations suggest that national output changes are less aligned with area changes, pointing to structural profiles where output dynamics are more influenced by factors not captured by area variation alone (e.g., shifting yield levels, changing shares of production contexts, or other unobserved structural adjustments). These interpretations remain descriptive: correlations at country level do not identify mechanisms, but they help characterize national production “signatures” under aggregation [1,54]. In addition, where Pearson and Spearman coefficients diverge and/or specification tests (RESET) and information criteria (AIC/BIC) favor nonlinear forms, coupling should be interpreted as indicative of monotonic but non-proportional relationships rather than linear scaling.

From a transition-oriented perspective, weak coupling may also be consistent with systems where output is less dependent on extensive land allocation and more dependent on the performance of a relatively constrained land base, which can be relevant when interpreting intensification profiles or controlled-environment configurations. Conversely, strong coupling may be consistent with profiles where land base dynamics are a dominant national signal. These patterns can guide future, more granular assessments where TAPE indicators can be measured at farm/territory level [12,15,36]. Because the analysis is based on national aggregates and a short time series, the coupling diagnostics are used to support structural interpretation and typology building, not to infer behavioral responses or policy effects.

4.4. Typologies and Multivariate Groupings: Linking Performance Profiles to Transition Narratives

The PCA and hierarchical clustering results illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, support the existence of coherent groupings among national yield profiles and dispersion patterns. Importantly, these groupings reinforce the correlations summarized in Table 6: countries cluster not only by mean yield level but also by the shape and stability of yield trajectories. The multivariate validation (KMO, Bartlett, explained variance, and Ward clustering coherence) supports that these groupings reflect consistent structural patterns rather than arbitrary aggregation artefacts. In a TAPE-informed narrative, these clusters can be viewed as representing distinct “performance regimes” that may correspond to different transition needs: for example, regimes characterized by compact distributions may prioritize resource efficiency and environmental performance improvements without compromising stability, whereas regimes characterized by broad distributions and low yields may prioritize transition-enabling investments and risk-reduction measures [24,27,39].

Table 6.

Pearson vs. Spearman correlations and formal non-linearity tests.

However, typologies derived from national statistics should not be interpreted as labels of “agroecological” vs. “non-agroecological” systems. Agroecological transition is multi-dimensional and includes governance, social values, knowledge co-creation, and circularity dimensions that are not captured by yield data alone [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Therefore, the typology is best interpreted as a macro-level starting point for differentiated policy questions and for prioritizing where deeper farm-level TAPE application could be most informative [18,19,28,29,30]. This is particularly relevant for transitional contexts (e.g., Romania), where macro profiles may reflect mixtures of production models and uneven modernization, underscoring the need for finer-grained evidence when designing transition support.

4.5. Interpreting Romania in the Macro Typology

Romania appears among the lowest mean yield profiles (Table 3) and shows broader dispersion relative to compact high-performing profiles. In addition, Romania’s instability indicators (CDV and Coppock) are comparatively high, reinforcing the interpretation of persistent structural instability and elevated year-to-year volatility under national aggregation. In the macro-level framework adopted here, this positioning can be interpreted as a transitional profile where production outcomes are more sensitive to interannual variability under national aggregation and where stability signals are comparatively weaker. This does not imply that Romanian tomato farming is uniformly low-performing; rather, it indicates that at national scale the sector may contain heterogeneous sub-systems, and that constraints such as infrastructure, investment capacity, and market conditions may influence aggregated performance. Accordingly, policy interpretation should focus on enabling conditions (e.g., irrigation reliability, protected-cultivation access where appropriate, risk-management tools, and knowledge/innovation support) rather than on yield levels alone. The results therefore support Romania’s relevance as a case for targeted transition strategies and for future disaggregated studies linking performance to specific management and territorial contexts [26,40,47,49,53].

4.6. Data Artefacts and Analytical Outliers

Denmark and Ireland present near-constant cultivated area series and very small national values, limiting the reliability of correlation and distribution diagnostics. In such cases, yield ratios can be highly sensitive to minor changes in the denominator and may produce inflated or unstable comparative indicators. These countries were therefore treated as analytical outliers in interpretation, and conclusions about performance regimes are drawn primarily from countries with sufficiently variable time series for robust comparison. Where reported, “not applicable (NA)” values reflect this insufficient variability, and these cases are excluded from formal correlation/specification testing.

4.7. Implications for Agroecological Transition and Policy Targeting

While this study does not quantify farm-level agroecological practices, the observed macro performance regimes are relevant for transition-oriented policy discussion. In TAPE terms, performance evaluation should integrate productivity with environmental and socio-economic dimensions; therefore, countries with stable high yields should not be assumed to be “sustainable” without complementary evidence on resource use, externalities, and social outcomes. Conversely, low-yield/high-dispersion profiles may face compounded vulnerabilities under climate variability and market shocks and may benefit from integrated transition support that combines risk reduction, enabling infrastructure, and knowledge systems, elements consistent with FAO’s agroecology framing (resilience, efficiency, recycling, responsible governance, co-creation of knowledge) [19,28,29,30,34,37].

At EU level, these findings support differentiated approaches rather than uniform prescriptions. Macro typologies can help frame questions about where support mechanisms should prioritize stability and risk management, where they should prioritize efficiency and environmental performance, and where deeper territorial/farm-level TAPE application could be strategically deployed to monitor transition progress. Importantly, the results should be read as comparative signals, not as evidence of the effectiveness of specific interventions [27,35,39].

4.8. Limitations

This study is based on aggregated national statistics (cultivated area, production, and derived yields), which enables harmonized cross-country benchmarking but imposes important limitations on inference. First, country-level indicators mask heterogeneity within-country in production systems (e.g., open-field vs. protected cultivation, heated vs. unheated structures, regional climatic gradients, and heterogeneous farm structures). As a result, observed differences in yield levels, dispersion, and area–production coupling should be interpreted as macro-level performance signatures rather than as evidence of homogeneous national “performance” or of specific farm-level practices.

Second, the use of ratio-based indicators (yield = production/area) can be sensitive to very small denominators. For countries with extremely small or near-constant cultivated areas in official statistics, small fluctuations in reported area may translate into disproportionately large changes in computed yields and related diagnostics. We therefore treat such cases as analytical outliers in interpretation and avoid drawing strong comparative conclusions from distribution- or correlation-based metrics when time-series variation is insufficient.

Third, the available time series (2015–2024; n = 10 observations per country) supports descriptive comparisons and robustness-oriented diagnostics, but limits the stability and power of more complex econometric specifications. In particular, regression-based outputs are interpreted as exploratory/descriptive rather than causal, and reported significance levels are treated as supportive evidence only. Where functional-form concerns arise, the Pearson–Spearman comparison and specification-oriented diagnostics provide useful indications, but they do not substitute for structural estimation using richer data.

Finally, while the analysis is framed through a TAPE-informed lens, full TAPE assessment cannot be implemented with national aggregates because TAPE requires farm- and territory-level measurement of multidimensional indicators (environmental, social, and governance components). Consequently, the present results should be viewed as a macro-level screening and typology-building step that can guide where and how future research could apply TAPE more directly using comparable microdata at farm or regional scale.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a TAPE-informed, macro-level benchmarking of European tomato production systems across 15 European countries (EU Member States and neighboring countries) over 2015–2024, combining yield level, yield distribution structure, interannual dispersion, area–production coupling, and multivariate typologies. The results confirm pronounced cross-country heterogeneity in both average performance and stability signals under national aggregation, indicating that European tomato sectors operate within distinct structural regimes rather than a single continuum.

Mean yield rankings identify a small group of very high-yield national profiles and a broader set of moderate-to-low yield profiles. Yield histograms and dispersion metrics further differentiate countries by distribution compactness versus broad or asymmetric dispersion, highlighting that stability-related signals vary substantially across the decade. Trend-adjusted instability and interannual volatility indices complement CV% and help distinguish deterministic trends from persistent instability relevant to agricultural risk. Area–production correlations provide an additional structural descriptor, showing that some countries exhibit strong coupling between cultivated area and output over time, whereas others show weaker alignment, consistent with different national production signatures and, in some cases, non-proportional (nonlinear) coupling patterns.

PCA and hierarchical clustering reinforce these contrasts by grouping countries with similar yield trajectories and dispersion patterns and by highlighting outlier behavior. Denmark and Ireland also present near-constant, very small cultivated-area series that limit the interpretability of correlation and distribution diagnostics.

From an agroecological transition perspective, these macro-level performance regimes can be used as comparative signals to support differentiated policy questions and to prioritize where deeper, farm- or territory-level TAPE assessment could be most informative. Countries characterized by compact yield distributions may warrant transition instruments that emphasize resource efficiency and environmental performance monitoring, while countries with broader distributions and low yield profiles may benefit from transition-enabling measures that strengthen stability and adaptive capacity. Overall, the study supports the value of combining cross-country statistical benchmarking with a TAPE-informed interpretation to frame agroecological transition narratives at EU scale, while maintaining caution about causal attribution from aggregated national data.

These findings support a differentiated policy interpretation, relevant to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP): where the area–production relationship is stable and approximately linear, area-linked instruments are more likely to translate into proportional output changes under national aggregation; where coupling is weak or nonlinear, improving performance is more likely to depend on targeted modernization (e.g., irrigation reliability, protected-cultivation infrastructure where appropriate, technological upgrading, and innovation support) rather than area expansion alone.

Multivariate results (PCA and Ward clustering) provide a coherent structural synthesis of national yield profiles, supporting the interpretation of recurring performance regimes and associated transition narratives.

In practical terms, systems positioned toward high technological performance may benefit most from instruments focused on sustainability, input-use efficiency, and energy efficiency (particularly in controlled-environment contexts), while systems characterized by higher climatic/structural vulnerability require targeted interventions in irrigation, climate-risk management, and transition-enabling support (infrastructure, advisory/knowledge systems, and risk reduction).

Future work should link national macro-statistics with farm- and regional-scale datasets enabling TAPE measurement (including environmental and socio-economic dimensions) and should explicitly disaggregate open-field versus protected cultivation shares to strengthen inference on transition pathways and policy levers.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16020263/s1, Mathematical formulas and model specifications cited in Section 2 are reported in Supplementary Materials S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and E.C.; methodology, E.C.; software, E.C.; formal analysis, E.C.; investigation, R.C.; resources, F.-D.N.; data curation, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, R.C.; project administration, R.C.; funding acquisition, R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitalisation CNCS/CCCDI-UEFISCDI, project number COFUND-AGROECOLOGY-AllEcoSys, within PNCDI IV.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created. The dataset supporting this study is based on publicly available Eurostat and FAOSTAT records.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (version 5.1) to assist with English language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kaymak, H.Ç.; Aksoy, A. Tomato Production and Price in the European Union. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2025, 25, 537–548. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M.F.; Antonio-Ordoñez, E.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Gallegos-Robles, M.A.; Vázquez-Vázquez, C.; Reyes-Gonzales, A.; Esparza-Rivera, J.R. Effect of Substrates Formulated with Organic Materials on Yielding, Commercial and Phytochemical Quality, and Benefit-Cost Ratio of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Produced under Greenhouse Conditions. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, E.E.V. An Overview of Recent Studies of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum spp.) from a Social, Biochemical and Genetic Perspective on Quality Parameters. Alnarp. Swed. Sver. Lantbruksuniversitet. 2018, 2018, 3. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. How Much Fruit and Vegetables Does the EU Harvest? Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250825-1 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Panno, S.; Davino, S.; Caruso, A.G.; Bertacca, S.; Crnogorac, A.; Mandić, A.; Noris, E.; Matić, S. A Review of the Most Common and Economically Important Diseases That Undermine the Cultivation of Tomato Crop in the Mediterranean Basin. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, V.C.; Odagiu, A.C.M.; Borsai, O.; Negrușier, C.; Maxim, A. Control Methods of the Late Blight Attack (Phytophthora infestans) in Tomatoes, in the Organic Culture System. AgroLife Sci. J. 2025, 14, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Naika, S.; Lidth de Jeude, J.V.; de Goffau, M.; Hilmi, M.; van Dam, B. Cultivation of Tomato: Production, Processing and Marketing; Agromisa Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands; CTA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Four Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) Farmer’ Varieties in Northeastern Portugal Homegardens. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2012, 50, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, L. Consumer Interest in Information Provided by Food Traceability Systems in Japan. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandage, K.; Badia-Melis, R.; Ruiz-García, L. Indian Perspective in Food Traceability: A Review. Food Control 2017, 71, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiadis, F.; Apostolidou, I.; Michailidis, A. Food Traceability: A Consumer-Centric Supply Chain Approach on Sustainable Tomato. Foods 2021, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. The Fruit and Vegetable Sector in the EU—A Statistical Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=The_fruit_and_vegetable_sector_in_the_EU_-_a_statistical_overview (accessed on 6 January 2026).

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy Use in Greenhouses in the EU: A Review Recommending Energy Efficiency Measures and Renewable Energy Sources Adoption. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, T.B.; Ribas, A.F.; de Souza, S.G.H.; Budzinski, I.G.F.; Domingues, D.S. Physiological Responses to Drought, Salinity, and Heat Stress in Plants: A Review. Stresses 2022, 2, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Duan, L.; Zhong, H.; Cai, H.; Xu, J.; Li, Z. Effects of Irrigation-Fertilization-Aeration Coupling on Yield and Quality of Greenhouse Tomatoes. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 299, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Singh, L.P.; Singh, G.; Kumar, A.; Pattnayak, K.C. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Environmental Impacts and Economic Feasibility of Tomato Cultivation Systems in Northern Plains of India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jensen, E.S.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.; Dimitrova Mårtensson, L.-M. Species Interactions and Nitrogen Use during Early Intercropping of Intermediate Wheatgrass with a White Clover Service Crop. Agronomy 2021, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, R.; Wu, S.; Miao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, X. Construction of a Tomato Seedling Growth Model and Economic Benefit Analysis under Different Photoperiod Strategies in Plant Factories. Hortic. Plant J. 2025; in press, corrected proof. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Di Fonzo, A.; Gaito, M.; Giuca, S.; Lupia, F.; Bonati, G.; De Leo, S. Climate Change Impact on Yield and Income of Italian Agriculture System: A Scoping Review. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulah, A.; Rajadurai, K.R.; Anitha, T.; Rajangam, J.; Maanchi, S. Postharvest Handling and Value Added Products of Tomato to Enhance the Profitability of Farmers. Plant Sci. Today 2025, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-García, I.; Davizón, Y.A.; Hernandez-Santos, C.; de la Cruz, N.; Hernandez, A.; Quiñonez-Ruiz, A.; Smith, E.D.; Sánchez-Leal, J.; Smith, N.R.; Benítez-García, I.; et al. Mathematical Modeling and Stability Analysis of Agri-Food Tomato Supply Chains via Compartmental Analysis. World 2025, 6, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner Kerr, R. Agroecology as a Means to Transform the Food System. Landbauforsch. J. Sustain. Org. Agric. Syst. 2020, 70, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezner Kerr, R.; Postigo, J.C.; Smith, P.; Cowie, A.; Singh, P.K.; Rivera-Ferre, M.; Tirado-von der Pahlen, M.C.; Campbell, D.; Neufeldt, H. Agroecology as a Transformative Approach to Tackle Climatic, Food, and Ecosystemic Crises. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 62, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francaviglia, R.; Almagro, M.; Vicente-Vicente, J.L. Conservation Agriculture and Soil Organic Carbon: Principles, Processes, Practices and Policy Options. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreinemachers, P.; Simmons, E.B.; Wopereis, M.C.S. Tapping the Economic and Nutritional Power of Vegetables. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzan, M.V.; Bocci, G.; Moonen, A.-C. Augmenting Flower Trait Diversity in Wildflower Strips to Optimise the Conservation of Arthropod Functional Groups for Multiple Agroecosystem Services. J. Insect Conserv. 2014, 18, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capobianco-Uriarte, M.D.L.M.; Aparicio, J.; Pablo-Valenciano, J.D.; Casado-Belmonte, M.D.P. The European Tomato Market. An Approach by Export Competitiveness Maps. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezel, A.; Bellon, S.; Doré, T.; Francis, C.; Vallod, D.; David, C. Agroecology as a Science, a Movement and a Practice. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, P.; Gkisakis, V.; Gonzalvez, V.; Raigón, M.D.; Bàrberi, P. Agroecology in Mediterranean Europe: Genesis, State and Perspectives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudrý, J.; Bernas, J.; Moudrý, J.; Konvalina, P.; Ujj, A.; Manolov, I.; Stoeva, A.; Rembiałkowska, E.; Stalenga, J.; Toncea, I.; et al. Agroecology Development in Eastern Europe—Cases in Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawalinska, K.; Smyrniotopoulou, A.; Balázs, K.; Böhm, M.; Chitea, M.; Florian, V.; Fratila, M.; Gradziuk, P.; Henderson, S.; Irvine, K.; et al. Advancing the Contributions of European Stakeholders in Farming Systems to Transitions to Agroecology. EuroChoices 2022, 21, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroegindewey, R.; Hodbod, J.; Vroegindewey, R.; Hodbod, J. Resilience of Agricultural Value Chains in Developing Country Contexts: A Framework and Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 10 Elements|Agroecology Knowledge Hub|Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/agroecology/overview/overview10elements/en/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- HLPE-FSN (High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security). Agroecological and Other Innovative Approaches for Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems That Enhance Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, E.; Gemmill-Herren, B.; Bicksler, A.; Siliprandi, E.; Brathwaite, R.; Moller, S.; Batello, C.; Tittonell, P. The 10 Elements of Agroecology: Enabling Transitions towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems through Visual Narratives. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficiciyan, A.M.; Loos, J.; Tscharntke, T. Better Performance of Organic than Conventional Tomato Varieties in Single and Mixed Cropping. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-López, V.; Granados-Echegoyen, C.A.; Pérez-Pacheco, R.; Robles, C.; Álvarez-Lopeztello, J.; Morales, I.; Bastidas-Orrego, L.M.; García-Pérez, F.; Dorantes-Jiménez, J.; Landero-Valenzuela, N. Plant Diversity as a Sustainable Strategy for Mitigating Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Tomato Cultivation. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1336810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidawanyika, F.; Omuse, E.R.; Agutu, L.O.; Pittchar, J.O.; Nyagol, D.; Khan, Z.R. An Intensified Cereal Push-Pull System Reduces Pest Infestation and Confers Yield Advantages in High-Value Vegetables. J. Crop Health 2025, 77, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, I.; Aribi, F.; Abdelhafidh, H.; Ferchichi, N.; Lajnef, L.; Toukabri, W.; Jaouad, M. Assessment of the Agroecological Transition of Farms in Central Tunisia Using the TAPE Framework. Resources 2025, 14, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, G.; Licciardo, F.; Verrascina, M.; Zanetti, B. The Agroecological Approach as a Model for Multifunctional Agriculture and Farming towards the European Green Deal 2030—Some Evidence from the Italian Experience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürkenbeck, K.; Spiller, A.; Meyerding, S.G.H. Tomato Attributes and Consumer Preferences—A Consumer Segmentation Approach. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pereira, I.; Aguiar, A.A.R.M.; Delgado, F.; Costa, C.A. A Methodological Framework for Assessing the Agroecological Performance of Farms in Portugal: Integrating TAPE and ACT Approaches. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejri, S.; Ghinet, A.; Magnin-Robert, M.; Randoux, B.; Abuhaie, C.-M.; Tisserant, B.; Gautret, P.; Benoit, R.; Halama, P.; Reignault, P.; et al. New Plant Immunity Elicitors from a Sugar Beet Byproduct Protect Wheat against Zymoseptoria Tritici. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gava, O.; Vanni, F.; Schwarz, G.; Guisepelli, E.; Vincent, A.; Prazan, J.; Weisshaidinger, R.; Frick, R.; Hrabalová, A.; Carolus, J.; et al. Governance Networks for Agroecology Transitions in Rural Europe. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havadi-Nagy, K.X. Alternative Food Networks in Romania—Effective Instrument for Rural Development? J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2021, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finatto, R.A.; Eduardo, M.F. Agroecological territorial system (SITA): A theoretical-methodological proposal for the construction and analysis of agroecology. Bol. Goiano Geogr. 2021, 41, 20220104901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merca, N.; Teodor, R.; Merca, I.; Ona, A. Agroecology: A Real Opportunity to Fight Against the Climate Challenges. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21, 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Seremesic, S.; Jovović, Z.; Jug, D.; Djikic, M.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Bavec, F.; Jordanovska, S.; Bavec, M.; Đurđević, B.; Jug, I. Agroecology in the West Balkans: Pathway of Development and Future Perspectives. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 45, 1213–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujj, A.; Ramos-Diaz, F.; Jancsovszka, P. Potential of Including Social Farming Initiatives within Agroecological Transition in Hungarian Farms. Eur. Countrys. 2022, 14, 456–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubov, A.; Zubova, L.; Zubov, A. Assessing the Possibility of Use Waste Rock Dumps as Elements of Ecological Network to Deter Agricultural Land Degradation and Promote Biodiversity in Mining Regions. J. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 25, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusch, A. Nature-Based Solutions to Increase Sustainability and Resilience of Vineyard-Dominated Landscapes. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2025, 82, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gătejel, A.-M.; Maiello, A. Commoning, Access, and Sovereignty: Disentangling Land–Food Relations in the Case of Peasant Livestock Farmers in Romania. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2024, 12, 00060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, D.M.; Berevoianu, R.L.; Giucă, A.-D. The Economic Efficiency of Tomato Cultivation and the Impact of the “De Minimis” Scheme on the Profitability and Competitiveness of Romanian Farmers. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2025, 19, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, G.; Toader, M.; Patrikakis, C.; Manouelis, M. Current Status Regarding the Use of Digital Educational Material and Internet Tools About Organic Agriculture and Agroecology in the European Agricultural Universities. Sci. Pap. Ser. A 2010, LIII, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M.; Burny, P.; Azadi, H. A New Wave in Romania: Organic Food. Consumers’ Motivations, Perceptions, and Habits. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2017, 41, 46–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcu, V.; Bubueanu, C.; Casarica, A.; Săvoiu, G.; Stoica, R.; Bazdoaca, C.; Lazăr, D.A.; Iordan, H.L.; Horhocea, D. Efficacy of Trichoderma Harzianum and Bacillus Subtilis as Seed and Vegetation Application Combined with Integrated Agroecology Measures on Maize. Rom. Agric. Res. 2023, 40, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, A.; Velicu, I.; Delibas, H.-I.; Pedro, S. “We Grow Earth”: Performing Eco-Agrarian Citizenship at the Semi-Periphery of Europe. Environ. Polit. 2024, 33, 778–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezeanu, P.M.; Brezeanu, C.; Tremurici, A.A.; Bute, A. Effects of Organic Inputs Application on Yield and Qualitative Parameters of Tomatoes and Peppers. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2022, LXVI, 429–437. [Google Scholar]

- EUROSTAT. Crop Production in EU Standard Humidity. Tomato. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/apro_cpsh1__custom_17693045/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=60fa40ea-dda7-4031-8f79-5d80237bc0c6&c=1754643083822 (accessed on 6 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.