Abstract

Rural e-commerce has spurred profound changes in rural production and living patterns. Taking the policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas as a quasi-natural experiment, based on the data from fixed observation points in rural China, this paper examines how rural e-commerce development affects rural households’ green production practices. The results show that (1) while rural e-commerce has generally led to a 5% increase in farmers’ chemical fertilizer use, its promoting effect on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input has been gradually weakening over time. (2) Crop planting types moderate the relationship between rural e-commerce and farmers’ fertilizer input behaviors. For farmers mainly planting food crops, rural e-commerce increases their chemical fertilizer use by 6.87%, while for those mainly planting cash crops, rural e-commerce reduces their chemical fertilizer use by 4.25%. (3) Mechanism analysis reveals that service outlet construction and e-commerce training for farmers are the main channels through which rural e-commerce drives farmers to increase fertilizer input, while brand cultivation is a channel through which rural e-commerce inhibits farmers’ fertilizer input, and this influence channel only exists among farmers mainly planting cash crops.

1. Introduction

Lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets, and rural areas have now become a central domain for implementing this green development concept; so, promoting green agricultural development is an essential path for agricultural and rural modernization. Notably, reducing the use of chemical fertilizers is a key component of agricultural green transformation. As a key agricultural production input, chemical fertilizers (as defined by China’s National Bureau of Statistics, specifically including nitrogen fertilizers, phosphorus fertilizers, potassium fertilizers, and compound fertilizers) have greatly boosted China’s agricultural economic growth. However, current fertilizer usage has exceeded the reasonable threshold, and their application cost now outweighs the resulting output benefits [1,2,3]. Long-term excessive application of chemical fertilizers not only threatens ecological security but also endangers the quality and safety of agricultural products [4,5,6,7]. Therefore, the Chinese government has formulated a series of special action plans for chemical fertilizer reduction, aiming to promote green agricultural production [8,9].

Many factors affect farmers’ chemical fertilizer application behavior, and relevant studies fall into two categories. One is internal factors related to farmers themselves. These include individual traits of farmers such as gender, education level, and risk preference [10,11], agricultural land operation traits such as cultivated land scale and land fragmentation degree [4,12,13], agricultural labor time constraints from part-time work and aging [14,15], and farmers’ financial constraints [16]. The other is external factors driven by the market and government. Existing research finds that the more agricultural products farmers sell on the market, the more chemical inputs they use; specifically, a one-unit increase in the sales proportion is associated with increases in chemical input intensity of 0.091, 0.074, 0.074, and 0.151 kg per mu for wheat, rice, corn, and fruits, respectively [17]. For policy guidance, government-initiated policies, such as the high-standard farmland construction policy and the chemical fertilizer zero-growth policy, can prompt farmers to cut down on their fertilizer inputs [18]. Among them, the highly targeted Chemical Fertilizer Zero-Growth Policy has steadily reduced fertilizer application, but it has not reversed the situation of China’s high chemical fertilizer input [19].

With the growing use of digital technology in rural areas, the digital economy led by e-commerce has gradually become a new engine for agricultural and rural development [20,21]. In 2014, the Chinese government launched the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas. It made it easier for farmers to engage in e-commerce by improving the county-township-village three-level logistics network, providing e-commerce operation training, and offering other forms of support. By the end of 2023, the online retail sales of agricultural products had reached CNY 587.03 billion (about USD 85.0 billion, based on the 2023 average annual exchange rate of USD 1 = CNY 6.9041), nearly 4 times higher than that in 2014. E-commerce is widely recognized to have greatly changed rural production and living patterns. It can not only alter the external market constraints on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input through reforms in the agricultural product sale sector but also reshape the internal resource allocation in farm production by creating non-agricultural employment opportunities, thereby triggering changes in chemical fertilizer usage. On the one hand, rural e-commerce has shortened the production–sale distance through supply chain flattening, letting producers accurately grasp consumers’ demand for high-quality agricultural products. The consumer evaluation and feedback mechanism has also formed an external constraint on reducing chemical agricultural input [22]. On the other hand, according to the New Economics of Labor Migration theory, farmers will optimize labor allocation through local labor migration based on considerations of household income and risk control [23]. Shorter labor migration distances mean a higher chance of part-time farming. Rural e-commerce has created many job opportunities (such as live streaming marketing and logistics distribution), promoting “labor migration without leaving the countryside” [24]. This makes the “farm-plus-nonfarm” part-time model a rational choice for farmers to fully utilize labor resources and maximize income [25]. However, the reduced agricultural labor input resulting from part-time work may lead farmers to use more chemical fertilizers to offset labor shortages [26], creating a countervailing force against the green production incentives driven by market demand. These two opposing effects mean the overall impact of rural e-commerce on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input, the determinants of its direction, and its underlying mechanisms remain theoretically ambiguous and require empirical research.

However, systematic empirical evidence on the relationship between rural e-commerce and farmers’ chemical fertilizer input remains relatively scarce. The research gaps primarily manifest in three aspects: First, existing studies focus on macro environmental impacts and lack precise analysis at the household micro-level. Most examine rural e-commerce’s overall effect on regional chemical fertilizer reduction [27] or only verify the reverse incentive effect of sale-side reforms on green production at the industrial level [28]. They fail to delve into the farm households as decision-making units, overlooking the direct influence of micro-factors such as household labor allocation and agricultural input purchase behavior on chemical fertilizer use. Second, heterogeneity analysis lacks targeted focus and neglects the moderating role of crop types. Current studies mainly group heterogeneous samples by geographical location or informatization level [29,30]. Yet, crop type is more likely to shape rural e-commerce’s impact direction on chemical fertilizer input. Cash crops and food crops differ in e-commerce adaptability, labor intensity, and quality requirements. These differences may lead to vastly different responses in farmers’ chemical fertilizer input to e-commerce development—but this critical moderating variable has been overlooked in existing research. Third, there are shortcomings in causal identification and mechanism analysis. Most existing studies are descriptive of correlations and fail to address endogeneity issues through causal identification methods like quasi-natural experiments. Furthermore, they do not link policy fund allocation to mechanism analysis. For instance, the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas provides each pilot site with CNY 20 million in central fiscal grants, designated for service network construction, logistics improvement, brand cultivation, and other uses. The specific channels through which rural e-commerce transmits these policy funds to farmers’ chemical fertilizer input decisions remain unexplored.

Based on these gaps, this paper focuses on three core research objectives: first, to explore the overall effect of rural e-commerce on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input; second, to examine whether crop type modifies the direction of this impact; and third, to identify the specific channels through which the fiscal funds of the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas affect farmers’ chemical fertilizer input decisions.

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Rural E-Commerce and Farmers’ Chemical Fertilizer Application

In agricultural production, farmers maximize their own utility by weighing various factors such as the amount of labor supply, the amount of fertilizer input, and the development of rural e-commerce. In this paper, the total utility of farmers can be decomposed into positive utility and negative utility.

Assuming ceteris paribus (other things being equal), farmers’ positive utility is determined by agricultural output , and the output depends on two agricultural production factors, namely, the labor supply and the fertilizer input . Then, the positive utility function of farmers can be expressed as follows:

With the increase in labor supply and chemical fertilizer input, crop output rises, and farmers’ positive utility increases accordingly; this is manifested as and . However, it should be noted that the marginal increment in crop output tends to decline. Consequently, the marginal positive utility that labor supply and chemical fertilizer input bring to farmers also diminishes, that is, and . Since the production function follows the concave rule, the positive utility of farmers exhibits concave characteristics, that is, ; here, , signifying that the influence of fertilizer input on the marginal positive utility of labor is positive.

Assume that the negative utility of farmers is determined by the labor supply and rural e-commerce development level . Then, the negative utility function of farmers can be expressed as follows:

As the amount of labor supply increases, the negative utility resulting from farmers’ labor input also increases. Moreover, the marginal negative utility that labor supply brings to farmers is on the rise, that is, and . In addition, , the impact of rural e-commerce on the marginal disutility of labor supply is uncertain. On the one hand, rural e-commerce can improve the efficiency of agricultural input procurement and popularize modern agricultural technologies such as agricultural machinery, thereby reducing farmers’ physical exertion. On the other hand, e-commerce market requirements for agricultural product quality force farmers to engage in refined labor to enhance market competitiveness, thus increasing their labor burden. Therefore, can take two values: one is , meaning rural e-commerce reduces the marginal disutility of labor; the other is , indicating rural e-commerce increases the marginal disutility of labor.

According to the above settings, the total utility function of farmers is as follows:

The development of rural e-commerce is an exogenous factor; farmers mainly maximize their own utility by adjusting the labor supply and the amount of fertilizer input. Therefore, we take the first-order derivatives of and in Equation (3) to obtain the conditions for maximizing the total utility: ; , and taking the total differential of these equations gives:

By rearranging Equations (4) and (5), we get:

After further rearrangement, the marginal impact of the development of rural e-commerce on farmers’ fertilizer input is obtained:

Based on the preceding analysis, for the right-hand side of Equation (7), the denominator is negative, and in the numerator is positive. Thus, when , then ; when , then . Based on this, the following two possible hypotheses are proposed:

H1:

Rural e-commerce development can increase farmers’ chemical fertilizer input.

H2:

Rural e-commerce development can reduce farmers’ chemical fertilizer input.

2.2. Heterogeneous Effect of Crop Planting Structure

Crop attributes determine the basic logic of chemical fertilizer input. Cash crops are more susceptible to market signals; so, farmers’ demand for chemical fertilizers focuses more on quality regulation; grain crops are dominated by yield; so, farmers focus more on chemical fertilizer prices, with market fluctuations exerting less influence on their chemical fertilizer input decisions. Thus, these two groups of farmers have distinct decision-making logics. We need to distinguish farmers’ crop planting types to conduct a heterogeneous discussion; otherwise, it may obscure key issues related to rural e-commerce’s impact on fertilizer input.

Suppose that there are two types of farmers in agricultural production, cash crop farmers and grain crop farmers. The farming income of both types of farmers is determined by output and the unit market price (assumed to be a constant). Thus, the farmers’ income function is as follows:

The output function follows the concave rule. Therefore, the income function satisfies the concave characteristic, that is, , , , , .

It is assumed that the costs include production costs and transaction costs incurred from the sale of agricultural products. Among these, production costs consist of the factor input costs of labor supply and chemical fertilizer input , and transaction costs depend on output and rural e-commerce development level . Thus, the total cost function of farmers’ crop cultivation can be expressed as follows:

It is assumed that the total cost of labor supply and fertilizer input is linear, that is, , , , . In addition, , the impact of rural e-commerce on the marginal cost of chemical fertilizer input exhibits significant differences across different crop types [31,32]. On the one hand, rural e-commerce can reduce farmers’ chemical fertilizer procurement costs by smoothing access to information channels and product circulation channels, thereby generating a procurement cost-saving effect on chemical fertilizer input. On the other hand, rural e-commerce possesses functions of product quality traceability and reputation accumulation [33,34]. High chemical fertilizer input will reduce the market competitiveness of agricultural products and increase transaction difficulty, resulting in a transaction cost-increasing effect.

Grain crops are bulk agricultural products, and grain crop farmers aim primarily at increasing yield. They rarely face cost fluctuations on the sale side due to quality differences. Therefore, for grain crop farmers, the procurement cost-saving effect of chemical fertilizer input brought by rural e-commerce is greater than the transaction cost-increasing effect of chemical fertilizer input, resulting in a negative impact on the total marginal cost of chemical fertilizer input, that is, . Cash crops focus on the quality regulation function of chemical fertilizers. Excessive fertilization may lead to deteriorated taste, damaged appearance, and other issues. Especially under the condition that rural e-commerce has continuously improved the agricultural product traceability system, high chemical fertilizer input will increase the risk of unsold agricultural products [35]. Furthermore, the transparent evaluation system constructed by e-commerce will amplify the quality defects of agricultural products, resulting in returns, compensation, and other problems, which leads to a sharp surge in transaction costs. Therefore, under the impact of rural e-commerce, for cash crop farmers, the transaction cost-increasing effect brought by chemical fertilizer input is far greater than the procurement cost-saving effect. Consequently, the impact of rural e-commerce on the total marginal cost of chemical fertilizer input is positive, that is, .

Based on the above assumptions, farmers’ profit function is as follows:

Farmers maximize the profit of cash crops by adjusting the labor supply and the amount of fertilizer input. Thus, according to the first-order conditions for profit maximization satisfied by the labor supply and the amount of chemical fertilizer input, ; ; taking the total differentials, respectively, we obtain:

Integrate Equations (11) and (12) to get:

After further integration, we obtain the marginal impact of rural e-commerce on the chemical fertilizer input:

Based on the preceding analysis, for grain crop farmers, on the right-hand side of Equation (14), the denominator is positive and the numerator is positive; thus, , meaning rural e-commerce promotes farmers’ chemical fertilizer input. For cash crop farmers, on the right-hand side of Equation (14), the denominator is positive while the numerator is negative; therefore, , indicating rural e-commerce helps inhibit farmers’ chemical fertilizer input. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H3:

For grain crop farmers, rural e-commerce will increase their chemical fertilizer input.

H4:

For cash crop farmers, rural e-commerce can reduce their chemical fertilizer input.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Setting

In this paper, the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas is regarded as a quasi-natural experiment to examine the impact of rural e-commerce development on farmers’ green production behaviors. The Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas is a national-level strategic initiative jointly launched by China’s Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Finance, and other relevant departments in 2014. Its core objective is to accelerate the construction of a county–township–village three-level e-commerce public service system and logistics distribution network, and promote the in-depth integration of e-commerce with rural characteristic industries. The pilot implementation adopts a “phased rollout” model: the first batch of pilot counties was approved in 2014, with new batches added annually thereafter. As of 2022, the policy has covered 1489 counties nationwide. Since this demonstration policy was piloted in counties in batches, a multi-period difference-in-differences model is constructed as follows:

Among them, i and t represent individual farmers and the year, respectively. Fertilizer represents the explained variable, which is the green production behavior of farmers; DID is the explanatory variable, representing the development of rural e-commerce; represents a series of control variables; represents the individual fixed effect; represents the year fixed effect; and represents the error term. This paper uses Stata software (Stata 15, StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for regression analysis.

3.2. Variable Selection

Chemical fertilizer input intensity (Fertilizer): This paper characterizes farmers’ green production behaviors from the perspective of fertilizer usage. Specifically, it is measured by the natural logarithm of the amount of fertilizer used per unit area.

Rural e-commerce development (DID): Based on the quasi-natural experiment of E-commerce in Rural Areas Demonstration Project, we gauge the development of rural e-commerce by means of setting a dummy variable (DID). If the area where the farmer is located belongs to the Demonstration County for E-commerce in Rural Areas, and the time is the year of becoming a demonstration county and later, set the DID to 1; otherwise, set it to 0.

Control variables (Control): The control variables at the farmer household level include the following: (1) the age of the household head (Age), which is represented by the natural logarithm of the household head’s age; (2) the educational level of the household head (Edu), which is represented by the natural logarithm of the number of education years of the household head; (3) the number of family labor force (Labor), expressed as the natural logarithm of the number of family labor force; (4) family income level (Income), which is represented by the natural logarithm of the year-end family income; (5) the proportion of non-agricultural income (Income), which is measured by the ratio of the family’s non-agricultural income to the total income; (6) productive fixed assets (Capital), which are represented by the natural logarithm of the original value of productive fixed assets; (7) the number of cultivated land plots (Block), which is represented by the natural logarithm of the number of cultivated land plots under operation; and (8) dummy variable for rural cadre households (Carder): if the household head is a rural cadre, take 1; otherwise, take 0. The control variables at the county level include the following: (9) regional economic development level (Pgdp), which is measured by the natural logarithm of the per capita gross domestic product; (10) industrial structure (Struc), which is measured by the ratio of the added value of the tertiary industry to that of the secondary industry; (11) fiscal situation (Fina), which is measured by the ratio of general public budget expenditure to general public budget revenue; and (12) financial development level (Loan), which is measured by the ratio of the loan balance of financial institutions at the end of the year to the regional gross domestic product (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistical analysis of the variables.

3.3. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This paper conducts research based on the data of China’s rural fixed observation points. This data system covers 23,000 sample farmer households and 370 sample villages, involving 31 provinces (municipalities) across the country excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. The data content includes the land situation of farmer households, agricultural production and operation, household income and expenditure, and the basic situation of family members. In particular, compared with county-level data, these records in detail the input of production materials such as chemical fertilizers, providing a good data foundation for this study. Considering the data update situation of the selected variables, this paper takes the national rural fixed observation point data from 2009 to 2017 as the research object, retains the farmer household samples that appear seven or more times during the sample period, and finally obtains a nine-period unbalanced panel data containing 20034 observations after collation.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Regression Analysis

Table 2 shows the benchmark regression results of the impact of rural e-commerce development on the amount of chemical fertilizer input. In Column (1) and Column (2), the regression results are shown with and without control variables, respectively. It can be found that under both conditions, the coefficient of DID is significantly positive at the 1% level. Specifically, in Column (2), the DID coefficient is 0.0499, indicating that rural e-commerce increases farmers’ chemical fertilizer application by approximately 5% on average, thereby exerting an adverse effect on green agricultural production.

Table 2.

Benchmark regression results.

4.2. Parallel Trend and Dynamic Effect Analysis

The prerequisite for using the difference-in-differences method is that the experimental group and the control group need to meet the parallel trend assumption. To examine whether there are differences in the chemical fertilizer input of the treatment group and the control group before the implementation of the policy project, the following cross-period dynamic effect model is constructed for testing:

Among them, and are dummy variables, which represent the kth year before and after county i where the farmer household is located is selected as the rural e-commerce demonstration county at time t, respectively. If the regression coefficient of is not significant, the parallel trend hypothesis is satisfied. As shown in Table 3, the regression coefficients of are not significant, indicating that the development trends of the treatment group and the control group are consistent before the implementation of the rural e-commerce promotion policy, which satisfies the parallel trend hypothesis. Similarly, by leveraging the approach of the event study method to observe the dynamic impact of the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce in Rural Areas on chemical fertilizer input each year, it is found that the coefficients of are all positive but decrease year by year. Until the third year after policy implementation, this positive impact becomes insignificant, suggesting that as time goes by, the demonstration policy has an increasingly weaker effect in boosting the amount of chemical fertilizer input by farmer households.

Table 3.

Parallel trend and dynamic effect test.

4.3. Robustness Analysis

4.3.1. Replace the Explained Variable

The previous text mainly measured the situation of chemical fertilizer input from the aspect of intensity. To conduct a robustness test, the situation of farmers’ chemical fertilizer input is reflected in terms of total quantity. Specifically, it is measured by the natural logarithm of the total amount of chemical fertilizer applied. As shown in Column (1) of Table 4, the coefficient of DID is 0.1562, which is significant at the 1% level. This further verifies that the development of rural e-commerce has increased the amount of chemical fertilizer used.

Table 4.

Robustness test results.

4.3.2. PSM-DID Estimation

To avoid the endogeneity problem caused by sample selection bias, the PSM-DID method is further employed for regression analysis. Firstly, the logit model is used to estimate the propensity scores of each sample. Secondly, the treatment group and the control group with close propensity scores are subjected to nearest-neighbor matching at a ratio of 1:1. The results show that the standardized deviation of the variables after matching is significantly reduced, indicating a satisfactory matching outcome. Based on the new samples, this paper re-examines the relationship between the development of rural e-commerce and the amount of chemical fertilizer input. The regression results demonstrate that the coefficient of DID remains significantly positive, as presented in Column (2) of Table 4.

4.3.3. Eliminate Other Policy Interferences

In 2014, China launched the “Broadband China” policy, and in 2015, the “Bringing Information to Rural Households” policy was implemented. To eliminate the interference of such policies, this paper sets up dummy variables for whether a region is a “Broadband China” pilot city and a “Bringing Information to Rural Households” pilot county. Additionally, in 2015, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs launched the “Action Plan for Zero Growth in Chemical Fertilizer Use by 2020”; therefore, this paper also sets up a dummy variable for whether a region is a key area for chemical fertilizer reduction work so as to exclude the impact of concurrent policies on the research results. The regression results in Column (3) of Table 4 show that the coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains significantly positive.

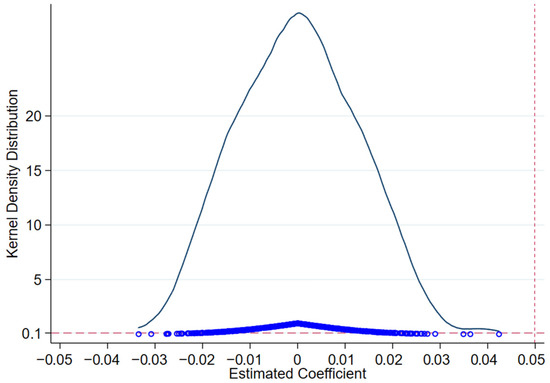

4.3.4. Placebo Test

To rule out the interference of other random factors, in this paper, the pilot sites of the Demonstration Project for E-commerce in Rural Areas are randomly set in arbitrary counties or districts. In this way, a randomly generated set of pseudo-treatment groups is obtained, and the remaining farmer household samples serve as the control group for conducting a placebo test. After 500 random and repeated samplings, as shown in Figure 1, the curve represents the kernel density distribution of the estimated coefficients; these coefficients are all concentrated around 0 and follow a normal distribution. The hollow dots represent the p-values corresponding to the estimated coefficients, and most of them are greater than 0.1. The vertical dashed line indicates the true estimated value of 0.0499, which appears as a prominent outlier in the figure; this shows that the above research results are indeed influenced by the demonstration policy, rather than being obtained accidentally.

Figure 1.

The result of placebo test.

5. Heterogeneity Analysis

According to the theoretical analysis, crop commercialization degree will influence the relationship between rural e-commerce and agricultural green production. Cash crops have a higher commercialization degree than food crops. When cash crop planting accounts for a large proportion, farmers’ chemical fertilizer input will not increase significantly with rural e-commerce development; instead, it may decrease. To test this, first, the proportion of cash crop planting (Econo) is measured by the ratio of cash crop sown area to total crop sown area. Second, based on the average proportion of cash crop planting of all farmers, those with a proportion lower than the average are classified into the low-proportion cash crop planting group, and those with a proportion higher than the average are classified into the high-proportion cash crop planting group. As shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5, in the sample of farmers with a low proportion of cash crop planting, the coefficient of DID is 0.0687 and is significant at the 1% level. However, in the sample of farmers with a high proportion of cash crop planting, the coefficient of DID is −0.0425 and is significantly negative at the 10% level. This indicates that the positive promoting effect of rural e-commerce on chemical fertilizer input only exists in the sample of farmers with a low proportion of cash crop planting. Conversely, in the sample of farmers with a high proportion of cash crop planting, the development of rural e-commerce helps to restrain farmers’ chemical fertilizer input.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity test results.

We also added the interaction term of rural e-commerce development and cash crop planting proportion to the benchmark model. The regression results show the interaction term’s coefficient is significantly negative at the 1% level. That is, a higher cash crop planting proportion weakens rural e-commerce’s promoting effect on chemical fertilizer input, further validating the theoretical hypothesis.

6. Mechanism Analysis

Previous studies mentioned in this paper have confirmed that rural e-commerce generally promotes farmers’ chemical fertilizer input; however, for cash crop farmers, it facilitates chemical fertilizer reduction. We need to analyze the underlying mechanisms for these conclusions. Due to the lack of micro-level farmer data, it is hard to capture how rural e-commerce affects individual farmers’ chemical fertilizer input; thus, this paper adopts a government perspective. The Demonstration Project of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas is a comprehensive policy with multiple development channels. From the planned uses of policy funds in demonstration counties, network outlet construction, service center development, logistics system improvement, brand cultivation, and talent training are the main targets of financial investment and key development channels for rural e-commerce. Following the study by Moser and Voena (2012) [36], this paper constructs the following continuous DID model to test the relationship between the planned uses of funds under the rural e-commerce policy and farmers’ chemical fertilizer input behavior:

Among them, , , , , respectively, represent the service outlet construction intensity, service center construction intensity, logistics construction intensity, brand cultivation intensity, and e-commerce training intensity in the county-level region where farmer resides in year . The development intensity of each policy channel is measured by the proportion of capital investment in each item. The specific capital investment data are sourced from documents such as the implementation plans for e-commerce in rural areas and the project fund plans announced on the websites of county-level governments.

After quantifying the policy implementation with continuous variables, as shown in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, whether control variables are added or not, the coefficients of and are both significantly positive, the coefficient of is significantly negative, and the coefficients of and are negative but not significant. This indicates that in the process of rural e-commerce affecting chemical fertilizer input, service outlet construction and e-commerce training are the main underlying mechanisms promoting the increase in chemical fertilizer input, while brand marketing helps inhibit farmers’ chemical fertilizer input. Although service center construction and logistics construction are conducive to reducing chemical fertilizer input, their current policy effects are not yet significant.

Table 6.

Mechanism test results.

The above results can be explained from the following aspects: The construction of service outlets is not only about establishing commodity circulation hubs but also about fostering a local e-commerce employment ecosystem. On one hand, service outlet construction serves to lower the information search, transportation, and bargaining costs incurred by farmers in chemical fertilizer procurement, rendering fertilizer more readily available and cost-efficient. On the other hand, the local non-agricultural positions generated by these outlets cater to farmers’ part-time employment preferences, that is, retaining land management rights while supplementing their income with non-agricultural earnings. However, rigid labor constraints stemming from part-time operations, combined with chemical fertilizer’s role as a “high-efficiency and low-operational-cost” capital input in agricultural production, position it as farmers’ optimal short-term substitute to mitigate labor shortages. E-commerce training helps enrich farmers’ e-commerce knowledge and strengthens their tendency towards part-time farming, but it further results in insufficient labor input in agricultural production, causing the excessive application of chemical fertilizers.

Brand cultivation aims to promote specialty products and establish a product traceability system and a supply chain system; this sets high requirements for the quality of agricultural products and thus has a significant inhibitory effect on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input. It is worth noting that brand cultivation emphasizes the commercialized attributes of crops, and non-cash crops such as grains have a relatively low commercialization degree and small differentiation, making them less likely to be the promotion targets for specialty agricultural products; therefore, brand cultivation will not play a chemical fertilizer reduction effect on crops with a low commercialization degree. In combination with the previous research, we test whether the impact of brand cultivation on chemical fertilizer input differs between the samples with a low proportion of cash crop planting and those with a high proportion of cash crop planting. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 6 present the regression results based on the samples with a low proportion of cash crop planting and the samples with a high proportion of cash crop planting, respectively. It can be observed that the coefficient of is only significantly negative in the sample with a high proportion of cash crop planting. Given the rigid consumer demand, high degree of standardization, and significant policy floor effect of food crops, there is a weak correlation between their market prices and quality. Consumers are less sensitive to quality signals conveyed by branding, making it difficult for brand cultivation to incentivize farmers to reduce chemical fertilizer input. By contrast, the diversified demand and differentiated characteristics of cash crops enable e-commerce branding to effectively convey quality signals and convert them into brand premiums. To secure higher returns, farmers will proactively reduce chemical fertilizer use to meet the quality requirements of branding. This not only validates the above analysis but also discloses that the reason why rural e-commerce promotes farmers with a high proportion of cash crop planting to reduce chemical fertilizer input lies in the brand-building channel.

In addition, service center construction and logistics construction focus on macro-level and long-term transformation. Service center construction aims to build county-level e-commerce service centers and e-commerce industrial parks, which has little direct correlation with farmers’ individual production and operation decisions in the short term. Logistics construction, for its part, is designed to establish warehousing and logistics centers and a three-level (county–township–village) logistics service system, which can alleviate the transportation challenges of agricultural products. However, it is a long-term project; so, its short-term impact on farmers’ agricultural production behaviors remains limited.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper takes the Demonstration Policy of E-commerce Entering Rural Areas as a quasi-natural experiment and uses data from the National Rural Fixed Observation Points spanning 2009 to 2017 to examine the impact of rural e-commerce development on farmers’ chemical fertilizer input, a key green production behavior. This study finds that rural e-commerce generally promotes farmers’ increased chemical fertilizer input, but this promotional effect gradually weakens over time. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that for grain-crop-dominated farmers, rural e-commerce promotes chemical fertilizer input, while for cash-crop-dominated farmers, rural e-commerce effectively facilitates chemical fertilizer reduction. Mechanism analysis indicates that service outlet construction and e-commerce training are the main channels through which rural e-commerce promotes farmers’ chemical fertilizer input, whereas brand cultivation is the primary channel inhibiting such input. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of brand cultivation on chemical fertilizer input only exists in the sample of cash-crop-dominated farmers. Based on the above conclusions, the implications are as follows:

First, targeting the core demand differences among farmers cultivating different crops, targeted classification-based interventions should be implemented to curb excessive chemical fertilizer application. For grain-crop-dominant farmers, priority should be given to mitigating agricultural labor constraints arising from non-agricultural employment. Specifically, subsidies may be allocated to agricultural socialized service organizations to deliver customized services to farmers, including mechanized plowing, precision fertilization, and unified field management. For cash-crop-dominant farmers who stand to benefit from e-commerce-driven fertilizer reduction, e-commerce participation barriers should be lowered through targeted subsidies (e.g., logistics cost subsidies for new cash crop farmers engaging in e-commerce) and preferential placement on platform homepages.

Second, e-commerce platforms should tailor their service offerings to the distinct production characteristics of grain and cash crops. For grain-crop-focused scenarios, platforms should launch a dedicated “Green Grain Fertilizer Zone” and give priority to listing low-toxic, slow-release chemical fertilizers that meet national green agricultural standards. By partnering with local governments, platforms should co-finance price subsidies to bridge the cost differential between green fertilizers and conventional chemical fertilizers, thereby improving farmers’ access to scientific fertilization practices. For cash-crop-focused scenarios, building on efforts to reduce e-commerce participation barriers, platforms should further intensify guidance on green production practices. Specifically, platforms may offer smallholder farmers complimentary services including brand strategy development, packaging design, and quality certification, and roll out “Economic Crop Brand Incubation Programs”. Furthermore, platforms should conduct regular online training programs on “Brand Building and Green Production” for cash crop farmers, equipping them to forge deep links between product quality and brand value.

Third, establish a long-term policy mechanism for the in-depth integration of rural e-commerce and green agricultural development. First, leverage annual survey data from rural fixed observation points to track the long-term trends of rural e-commerce’s impact on fertilizer application, updating policy tools (e.g., adjusting subsidy ratios, optimizing platform guidance content) every 2–3 years based on monitoring results. Second, build a sustainable agricultural brand cultivation system, develop regional public brands, support farmers in registering individual brands for characteristic products, and form an incentive mechanism where “brand premium drives green production.” Third, allocate long-term funding support to service centers to ensure the permanent presence of scientific research institutions, enabling continuous agricultural technical services. Furthermore, expand the coverage of cold chain logistics networks to provide quality-oriented logistics support for high-value agricultural products.

8. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

This study employs data from the China Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey covering the period of 2009–2017, which is subject to the limitation of a relatively early data cutoff. Constrained by data availability, this research fails to cover the phase of drastic evolution of the rural e-commerce ecosystem after 2018, making it impossible to fully capture the dynamic impact of e-commerce model iterations on chemical fertilizer application.

Nevertheless, this study’s conclusion that the promoting effect of rural e-commerce on chemical fertilizer input weakens over time establishes an indispensable preliminary reference framework for subsequent comparative analyses of changes in rural e-commerce’s impacts. Furthermore, this result can, to some extent, reflect the trend of rural e-commerce’s influence on chemical fertilizer input after 2018: as rural e-commerce transforms towards standardization, branding, and high-quality development, the driving role of brand cultivation in chemical fertilizer reduction will become increasingly prominent. Consequently, the promoting effect of rural e-commerce on chemical fertilizer input will show a dynamic downward trend year by year, and even chemical fertilizer reduction may be achieved in a later stage.

In the future, the data timespan can be expanded by actively collecting newly added data from the China Rural Fixed Observation Point Survey after 2018, extending the research period to around 2025. This expansion will serve two purposes: first, to verify the long-term validity of the “weakening effect trend” identified in this study; and second, to explore new pathways for promoting chemical fertilizer reduction through rural e-commerce.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D. and H.C.; methodology, Y.D. and H.C.; software, Y.D.; validation, Y.D., H.C. and M.C.; formal analysis, Y.D.; investigation, Y.D. and H.C.; resources, Y.D. and M.C.; data curation, Y.D., H.C. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D.; writing—review and editing, Y.D., H.C. and M.C.; visualization, H.C. and M.C.; supervision, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the authors. The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleges. All support and assistance are sincerely appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, X.; Shao, S.; Li, L. Agricultural Inputs, Urbanization, and Urban-rural Income Disparity: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2019, 55, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.L.; Luo, B.L.; Hu, X.Y. The Determinants of Farmers’ Fertilizers and Pesticides Use Behavior in China: An Explanation Based on Label Effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 123054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.K.; Tu, T.T.; Li, X. Will the Substitution of Capital for Labor Increase the Use of Chemical Fertilizer in Agriculture? Analysis Based on Provincial Panel Data in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 21052–21071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xi, X.; Tang, X.; Luo, D.; Gu, B.; Lam, S.K.; Vitousek, P.M.; Chen, D. Policy Distortions, Farm Size, and the Overuse of Agricultural Chemicals in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 7010–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahalvi, H.N.; Rafiya, L.; Rashid, S.; Kamili, A.N. Chemical Fertilizers and Their Impact on Soil Health. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.; Kang, J. Research on the Impact of Internet Use on Fertilizer and Pesticide Inputs: Empirical Evidence from China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrana, J.; Nazrana, A.; Mishra, A.K. Input Subsidies, Fertilizer Intensity and Imbalances Amidst Climate Change: Evidence from Bangladesh. Food Policy 2025, 133, 102825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.R.; Li, T.Y.; Cao, H.B.; Zhang, W.F. Research on the Driving Factors of Fertilizer Reduction in China. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2020, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ding, W.C. Strategic Researches of Reducing Fertilizer Use and Increasing Use Efficiency in China in the New Era. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2023, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Baylis, K.; Kozak, R. Farmers’ Risk Preferences and Pesticide Use Decisions: Evidence from Field Experiments in China. Agric. Econ. 2016, 47, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X.; Hao, H.T.; Lei, H.Z.; Ge, Y. Farm Size, Risk Aversion and Overuse of Fertilizer: The Heterogeneity of Large-Scale and Small-Scale Wheat Farmers in Northern China. Land 2021, 10, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.W. Influence of Transfer Plot Area and Location on Chemical Input Reduction in Agricultural Production: Evidence from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhong, Y. Plot Scale and Fertilizer Input: Logic and Evidence of Reduced Consumption. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2024, 43, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drall, A.; Mandal, S.K. Non-farm income and environmental efficiency of the farmers: Evidence from India. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, J.L.; Lv, W.Q.; Xie, H.L.; Xu, X.D. Towards Low-Carbon Agricultural Production: Evidence from China’s Main Grain-Producing Areas. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 60, 104952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Ji, H. The Impact of Cost-of-Production Insurance on Input Expense of Fruit Growing in Ecologically Vulnerable Areas: Evidence from Shaanxi Province of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.J.; Shi, Q.H. The Impacts of Rural Households’ Productive Characteristics on Pesticide Application: Mechanism and Evidence. Chin. Rural Econ. 2019, 11, 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.T.; Zhang, L.J.; Wang, Z.H. The Impact of Well-Facilitated Farmland Construction on Agricultural Production: From the Perspectives of Agricultural Factor Elasticity and Agricultural Total Factor Productivity. China Rural Surv. 2023, 4, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Chen, H.L.; Li, Z.S.; Ruan, Y.; Yang, Q. Temporal and Spatial Analysis of Fertilizer Application Intensity and its Environmental Risks in China from 1978 to 2022. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shi, M.; Ma, W.L.; Liu, T.J. The Adoption and Impact of E-commerce in Rural China: Application of an Endogenous Switching Regression Model. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 83, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, M. Can Rural E-commerce Narrow the Urban–rural Income Gap? Evidence from Coverage of Taobao Villages in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.D.; Lv, H.Z.; Wang, Z.M. Enhancing Environmental Sustainability in Transferred Farmlands through Rural E-commerce: Insights from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 25388–25405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, O.; Bloom, D.E. The New Economics of Labor Migration. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.M.; Zheng, J.; Li, T.W. Does E-commerce Offer a Solution to Rural Depopulation? Evidence from China. Cities 2024, 152, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Zhou, L. E-commerce Development, Time Allocation and the Gender Division of Labour: Evidence from Rural China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 32, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.N.; Long, H.L.; Li, Y.R.; Ge, D.; Tu, S. How does Off-farm Work Affect Chemical Fertilizer Application? Evidence from China’s Mountainous and Plain areas. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Xu, J.W.; Zhang, H.X. Environmental Effects of Rural E-commerce: A Case Study of Chemical Fertilizer Reduction in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.Z.; Wang, X.P.; Zhang, S.X. Can Rural E-commerce Contribute to Carbon Reduction? A Quasi-natural Experiment Based on China’s E-commerce Demonstration Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 104336–104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Tang, K.; Shi, Q.H. Does Internet Use Reduce Chemical Fertilizer Use? Evidence from Rural Households in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 6005–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.K.; He, B.; Yuan, R.; Wang, Z. E-commerce Operation Empowers Green Agriculture: Implication for the Reduction of Farmers’ Fertilizer Usage. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1557224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Xia, C.; Ali, A. Does E-commerce Participation Increase the Use Intensity of Organic Fertilizers in Fruit Production? Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Tang, B.J. The Impact and Mechanism of E-commerce on Rural Agriculture: Evidence from China. NJAS Impact Agric. Life Sci. 2025, 97, 2523380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilali, H.E.; Allahyari, M.S. Transition towards Sustainability in Agriculture and Food Systems: Role of Information and Communication Technologies. Inf. Process. Agric. 2018, 5, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zeng, Y.W.; Liu, M. Policy Interventions and Market Innovation in Rural China: Empirical Evidence from Taobao Villages. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1411–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.Y.; Wang, C. Effect of Taobao Village Certification on Agricultural Fertilizers and Pesticides Usage in China. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, P.; Voena, A. Compulsory Licensing: Evidence from the Trading with the Enemy Act. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 396–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.