1. Introduction

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is a severe enteric disorder affecting swine populations worldwide, and its onset is attributed to infection with porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV). This virus belongs to the

Alphacoronavirus lineage within the

Coronaviridae family and is characterized by rapid transmission and acute clinical manifestations, thereby posing a substantial threat to global pig farming and production systems [

1]. Initially recognized in the United Kingdom in 1977 and then documented in Belgium in 1978 [

2], following its emergence, PEDV disseminated extensively throughout Asia, Europe, and the American continents, leading to severe economic damage as a result of epidemics marked by high rates of illness and mortality among neonatal piglets [

1]. The viral particle is enveloped and harbors a positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome of approximately 28 kb in length. This genome directs the synthesis of seven nonstructural proteins (nsp1–nsp7) involved in viral genome replication and transcription, as well as four major structural components, namely the spike (S), membrane (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins [

3]. Viral attachment and entry are initiated by the spike (S) protein, which recognizes and engages receptors expressed on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells, ultimately facilitating membrane fusion and enabling the establishment of infection [

2]. PEDV transmission primarily occurs via the fecal-oral route, with neonatal piglets exhibiting severe clinical symptoms, including acute watery diarrhea, vomiting and dehydration [

1]. With death rates in newborn piglets (less than three days old) without lactogenic immunity reaching 70–100%, these clinical signs are especially severe in piglets [

4]. Pathologically, PEDV infection causes extensive destruction of small intestinal villi [

1], leading to enterocyte atrophy, impaired nutrient absorption, and osmotic diarrhea. Moreover, the virus infects the colon, damaging mucosal structures and disrupting colonic crypt integrity [

5]. According to research, PEDV infection lowers the amount of good bacteria in piglets’ colons while increasing the amount of dangerous bacteria [

6]. The emergence of highly virulent and transmissible variants, coupled with incomplete cross-protection from vaccines and the absence of specific antiviral drugs [

7], underscores the urgent need for novel strategies to mitigate PEDV-induced enteric damage.

Nutritional intervention, particularly with leucine (Leu), a hydrophobic branched-chain amino acid (BCAA; 2-amino-4-methylpentanoic acid, C

6H

13NO

2), has surfaced as a viable strategy to improve gut health and antiviral responses [

8,

9]. Beyond its role in protein synthesis, Leu acts as a key signaling molecule regulating metabolism, growth, and immune function [

8,

10,

11]. In weaned pigs consuming low-protein diets, the administration of dietary leucine has been shown to enhance tissue protein synthesis, significantly elevating growth rates and boosting feed efficiency [

12]. In particular, dietary inclusion at a level of 0.55% markedly promoted protein accretion in multiple tissues, including skeletal muscle, liver, and kidney, and was associated with an increase in average daily weight gain of up to 61% [

13]. Leu is essential for preserving the structure and functionality of the gastrointestinal tract. Research showed that in piglets with normal birth weights, Leu supplementation enhanced intestine development and general growth [

11]. Of relevance to viral enteritis, dietary addition of 1% L-Leu alleviated rotavirus-induced diarrhea in weaned piglets. The result suggests that activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR)-associated signaling cascade played a mediating role in the observed protective effect, which restored mucin production, specifically Mucin 1 (MUC1) and Mucin 2 (MUC2), within the jejunal region, consequently enhancing the structural robustness and functional stability of the intestinal mucus barrier [

14]. Leu markedly suppresses PEDV replication in porcine intestinal epithelial cells through the stimulation of mTOR-associated signaling mechanisms, thereby demonstrating a strong antiviral capacity. Through this mechanism, Leu alleviates the virus-induced inhibition of interferon-responsive genes and the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), both of which play pivotal roles in the host innate antiviral defense system [

9]. In addition, Leu contributes to the maintenance of redox homeostasis by stimulating the activities of key antioxidant enzymes in the serum, liver, and skeletal muscle, while concurrently reducing malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations, an established indicator of oxidative damage and lipid peroxidation [

15].

Despite these promising findings, the mechanistic understanding of Leu’s protective effects against PEDV infection in vivo remains incomplete. However, the effects of Leu on colonic tissues in piglets challenged with PEDV remain largely unexplored. Therefore, based on the reliable PEDV infection model previously established by this research team, this study is aimed at systematic examination of the protective effects of Leu against PEDV-induced colonic injury, to provide crucial theoretical support for the application of Leu to safeguard intestinal health in PEDV-infected young piglets.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Animal Models and Experimental Layout

This investigation was carried out in 2024 using eighteen healthy seven-day-old Duroc × Landrace × Large White three-way crossbred piglets (body weight [BW] = 2.58 ± 0.05 kg) from PEDV-negative farms. The farms tested sows and piglets for PEDV antigen (reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction detection) and PEDV-specific serum antibodies (inhibition enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection) prior to piglet transportation. Only piglets confirmed to be free of PEDV antigen and PEDV-specific serum antibodies were selected for transport to our experimental facility. Piglets of similar initial body mass were randomly assigned to three treatment groups using a single-variable, fully randomized experimental scheme, including an untreated control group (Control), a PEDV-challenged group (PEDV), and a group receiving Leu supplementation in combination with PEDV infection (Leu + PEDV). Each group consisted of 6 piglets (n = 6). The experimental period lasted 11 days: days 1–3 served as a pre-feeding period for environmental adaptation and acclimation to the artificial milk; days 4–10 constituted the formal experimental phase, during which all groups were fed the artificial milk. Throughout the experimental phase, piglets assigned to the Leu + PEDV group received a daily oral dose of Leu mixed with artificial milk at 19:30. At the same point, animals in both the control and PEDV-only groups were given an equivalent amount of artificial milk without Leu supplementation. Piglets in the PEDV and Leu + PEDV cohorts received a 3 mL aliquot of PEDV suspension (1 × 106 50% tissue culture infective dose [TCID50] per milliliter) at 20:30 on day 8. Meanwhile, piglets in the control group were treated with a comparable dose of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium. All piglets were denied food and water starting at 22:00 on day 10. On day 11, piglets were put to death by intramuscular injection of 0.2 mL/kg BW of Zoletil 50 (Virbac, Paris, France). Piglets were dissected to obtain samples when it was confirmed that they had completely lost consciousness. To facilitate subsequent analytical procedures, specimens were promptly cryopreserved using liquid nitrogen and then stored long-term in an ultralow freezer maintained at −80 °C.

2.2. Experimental Materials

The Yunnan isolate of PEDV was preserved and maintained at the Hubei Key Laboratory of Animal Nutrition and Feed Science laboratory. Piglets received Leu supplementation at a level of 400 mg/kg BW; Leu (Catalog number L6238; 99% purity) was sourced from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The experimental diet consisted of whole milk powder (Nouriz, imported from Auckland, New Zealand) mixed with 0.1% water-soluble vitamins (HuaLuo Universal Vitamin Premix for Poultry and Livestock, Beijing, China).

Table 1 displays the nutritional composition of the whole milk powder. The milk powder was reconstituted with water at a ratio of 1:5.

2.3. Feeding Management

The experiment was conducted within a standardized animal facility, which was equipped with an air ventilation system to facilitate indoor air circulation and maintain environmental sterility. The facility’s temperature was meticulously regulated to maintain a constant range of 27–29 °C, thereby ensuring a stable and optimal growth environment for the piglets. The piglets in the Control group, PEDV group, and Leu + PEDV group were housed in distinct, isolated pens that were identical in environmental settings. Physical barriers and separate ventilation systems were implemented between pens to mitigate the risk of viral cross-contamination. Throughout the trial, the artificial milk was provided at five consistent feeding times each day: 7:30, 11:00, 15:00, 18:00, and 21:00. Artificial milk was freshly prepared at a ratio of 1 part milk powder to 5 parts water by mass and provided to piglets for unrestricted consumption without time limitations; the supply of artificial milk was withdrawn when the piglets ceased voluntary ingestion completely. The feeding dosage was standardized as 20 g milk powder per pig for each feeding, and the total amount of artificial milk used for each group was 720 g per meal. Following the feedings at 7:30, 15:00, and 21:00, an ample supply of clean drinking water at a temperature of 25–30 °C was made available to satisfy the piglets’ normal physiological metabolic requirements. After each feeding, all feeding equipment, feeders, drinkers, and the pigpen floor and walls were thoroughly disinfected using a rotating regimen of 0.5% glutaraldehyde solution and 0.1% benzalkonium chloride solution. The area was then ventilated for 30 min post-disinfection. Upon the conclusion of the experiment, a comprehensive environmental spray disinfection of the entire facility was conducted daily to prevent bacterial contamination. Concurrently, during feeding periods and routine inspections, careful observations were made of each group of piglets’ daily feed intake, mental condition, and state of diarrhea.

2.4. Intestinal Sample Preparation

Colon tissue samples were collected separately from piglets in each group. A portion of each colon tissue sample was immediately immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde fixative solution. After fixation at room temperature for 24 h, these samples were used for subsequent intestinal paraffin section preparation and morphological observation. The remaining colon tissue was gently rinsed with pre-chilled saline to remove intestinal contents and surface impurities. Adipose tissue stuck to the tissue surface was then removed in an ice bath. After being cleansed, the intestinal tissue was divided into little pieces, labeled according to the group, covered in aluminum foil, and put inside sterile gauze bags. After rapid immersion in liquid nitrogen to achieve instant freezing, the samples were stored at −80 °C in a cryogenic freezer for later experimental evaluation.

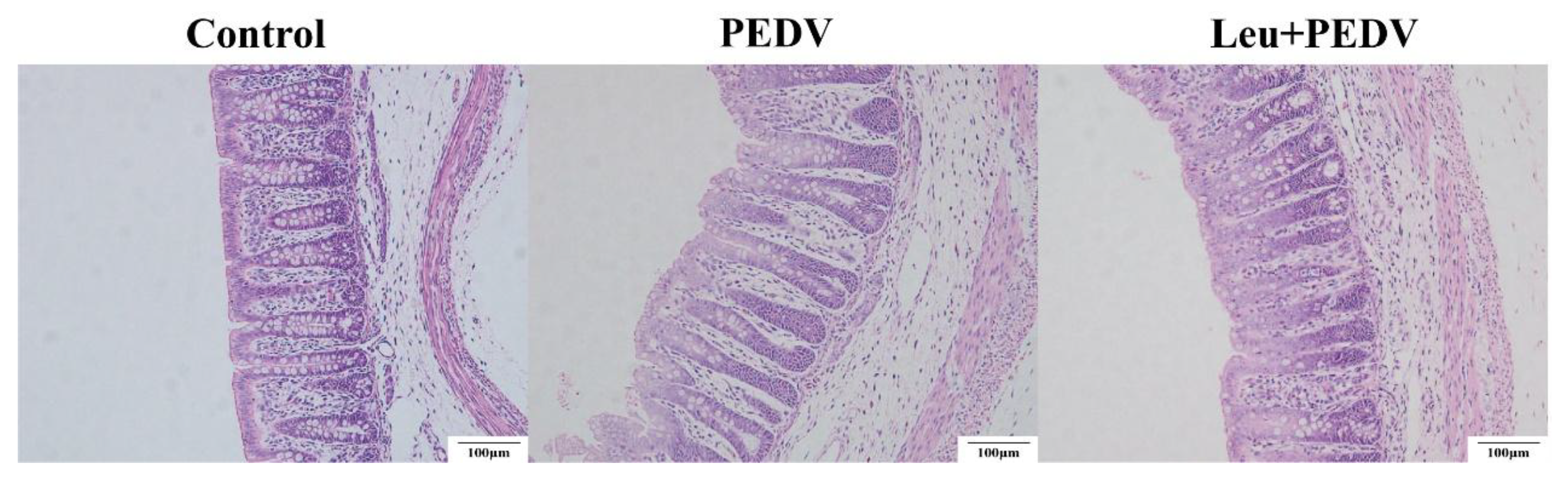

2.5. Colonic Structural Morphology Measurement

Paraffin-embedded intestinal sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) by Wuhan BOLF Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Colonic morphological observations were performed using an Olympus BX-41 TF optical microscope (Tokyo, Japan), and crypt depth (CD) was quantified via OLYMPUS cellSens Standard 1.1.8 image analysis software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). CD was defined as the vertical distance extending from the opening of the crypt to the base of the epithelial layer. For each piglet, six sections were randomly selected, and five intact crypts were measured per section. The average value was used as the CD data for that piglet.

2.6. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity in the Colon

The kits used in this study were obtained from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China): total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD; the wavelength of analysis is 550 nm; Catalog number A001-1-2), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px; the wavelength of analysis is 412 nm; Catalog number A005-1-2), catalase (CAT; the wavelength of analysis is 405 nm; Catalog number A007-1-1), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; the wavelength of analysis is 405 nm; Catalog number A064-1-1), MDA (the wavelength of analysis is 532 nm; Catalog number A003-1-2), and myeloperoxidase (MPO; Catalog number A044-1-1; the wavelength of analysis is 460 nm). All materials are diluted to a 10% (w/v) concentration for subsequent experimentation. Every assay was carried out in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7. Quantification of mRNA Expression Levels in the Colon

Colon tissues that had undergone cryopreservation were extracted from liquid nitrogen, pulverized in liquid nitrogen, and weighed at 100 mg. Total RNA was extracted using the RNAiso Plus Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized via reverse transcription with the PrimeScript

TM RT Reagent Kit containing gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed using the SYBR

® Premix Ex Taq

TM (Tli RNaseH Plus) Reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Ribosomal protein L19 (

RPL19) served as the internal reference gene. The relative expression of genes was calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method [

16].

Table 2 had a list of primer sequences.

2.8. Statistics and Analysis of Data

Microsoft 365 Excel was used to initially compile and handle all experimental measurements, after which statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS (26.0). A one-way ANOVA was applied to evaluate differences among groups, and Tukey’s post hoc procedure was used to identify pairwise differences. The significance level was set at p < 0.05, and the results are shown as mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

As a major segment of the large bowel, the colon is indispensable for the regulation and maintenance of normal physiological processes in the body. Its main functions include absorbing water and electrolytes, storing feces, preventing harmful substances from invading through the mucosal barrier, and participating in immune defense responses and the synthesis of metabolites [

17,

18]. Structurally, the colon wall comprises four layers from inner to outer: the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa [

19]. The mucosa serves as the core functional region, featuring a smooth surface devoid of villi, with crypts (also termed intestinal glands) as its defining structural element [

20]. CD serves as a key indicator for assessing intestinal epithelial regeneration capacity and nutrient absorption function [

21]. Deeper crypts may reflect increased cellular proliferation demands or suggest mucosal repair following injury [

22]. Previous research confirmed that piglets challenged with PEDV exhibited a pronounced rise in CD expression within colonic tissues. [

23]. Consistent with this finding, our study demonstrated that Leu administration significantly reduced colonic CD in PEDV-infected piglets, suggesting Leu’s mitigating effect on PEDV-induced intestinal mucosal damage in piglets.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), specifically

MMP7 and

MMP13, are pivotal molecules in tissue repair and remodeling processes [

24,

25]. Elevated levels of these enzymes are indicative of active tissue remodeling within the microenvironment, acting as critical pathobiological markers [

25,

26]. The mucus layer lining the gut constitutes a crucial interface separating nutrients and pathogens from epithelial cells, with MUC2 representing the major gel-forming mucin that underpins the structural framework of this protective barrier [

4]. Research indicates that young pigs exhibit lower

MUC2 expression levels, rendering them more susceptible to early viral infections [

4]. Downregulation of

MUC2 expression directly compromises the barrier protective capacity of the mucus layer itself [

27]. Findings from the present investigation indicated that infection with PEDV resulted in a marked reduction in the relative abundance of

MUC2 transcripts within colonic tissues. This result indicates that PEDV infection disrupts mucus barrier integrity. However, oral administration of Leu did not significantly alter the expression levels of

MUC2 in the colon of PEDV-infected piglets.

MUC5AC, a secretory mucin, primarily serves to construct and protect the mucosal epithelial mucus barrier, thereby lubricating the intestinal surface and defending against pathogens and harmful substances [

28]. In healthy animals,

MUC5AC levels are typically very low or even absent. However, under disease conditions such as tumors, its levels increase [

29]. Accumulating evidence has shown that upregulation of

MUC5AC was a characteristic feature of multiple respiratory disorders, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and plays a key role in excessive mucus production and subsequent blockage of the airways [

30,

31]. PEDV challenge is found to significantly upregulate the transcript abundance of

MMP7,

MMP13, and

MUC5AC within colonic tissues. While oral administration of Leu effectively downregulated the expression of these genes. These findings suggested that Leu can mitigate PEDV-induced intestinal injury and facilitate intestinal morphological repair. This discovery offers novel insights into Leu’s mechanism of intestinal protection. Nevertheless, the present results showed that even after leucine supplementation, PEDV-challenged piglets exhibited persistently elevated

MUC5AC expression in colonic tissues compared with the control group. Although oral Leu effectively downregulated the abnormal elevation of

MUC5AC, it failed to eliminate residual pathological microenvironments (such as gaps in barrier repair) from PEDV infection within the short term. This may be because the intestine still requires maintaining a certain level of

MUC5AC to meet barrier protection demands during the repair phase. As a result, after Leu treatment,

MUC5AC expression was maintained at a level that lay between that observed in uninfected controls and that detected in the PEDV-infected group.

Cells rely on a defense system dominated by enzymes, including GSH-Px, CAT, and T-SOD, which act to eliminate free radicals and reactive oxygen species and thus guard against damage caused by oxidative stress [

5]. Malondialdehyde (MDA), generated during lipid peroxidation processes, is widely recognized as an indicator for evaluating the extent of oxidative stress [

32]. Previous studies have confirmed that PEDV infection significantly reduces CAT activity in piglet colonic tissue [

5] while increasing MDA content [

33], findings that align with those of this study. This suggested that PEDV infection disrupted redox homeostasis in piglets, triggering a marked oxidative stress response. However, oral Leu administration alleviated PEDV-induced oxidative stress by restoring CAT activity.

The structural proteins of PEDV, including the N, M, and S proteins, play crucial roles in viral pathogenesis. The N protein, an abundant structural protein present throughout the entire infection cycle, serves as an ideal target for early PEDV diagnosis [

34] and participates in viral replication and cellular infection processes [

35]. As the major structural constituent of the viral envelope, the M protein plays a central role in virion formation and release, while simultaneously suppressing host innate immunity through interference with type III and type I interferon signaling; moreover, it is capable of inducing protective antibody responses in swine [

36]. The S protein enables viral invasion by governing receptor engagement and membrane fusion, thereby allowing the nucleocapsid to be delivered into the host cell cytosol and serving as a critical determinant of cellular entry [

37]. This work demonstrated that Leu treatment markedly diminished the mRNA expression levels of

M,

N, and

S in the colonic tissues of PEDV-infected piglets, thereby successfully suppressing viral replication in the gut. These findings indicate that Leu, an important amino acid that is both safe and readily accessible, functions as an antiviral agent, offering novel insights and strategies for the nutritional prevention and management of PEDV infection in swine production.

S100A9 and

S100A8 are calcium-binding proteins in the S100 family that typically function as heterodimers (S100A8/A9) and serve as important predictive indicators for therapeutic responses in inflammation-related diseases [

38].

IL-1β, a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine and core mediator of inflammatory responses, exhibits expression levels closely correlated with S100A8/A9. Upregulation of S100A8/A9 activates the TLR4-NLRP3-IL-1β signaling axis, resulting in a substantial release of mature IL-1β and ultimately exacerbating tissue damage [

39].

REG3G is a member of the Regenerating islet-derived (Regen) gene family, which primarily functions as an antimicrobial peptide, directly defending against pathogenic microbial invasion and maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier [

40]. Li observed that PEDV infection increases

IL-1β and

REG3G levels in piglet colon tissue, findings that are consistent with this research [

23]. In addition, the present study demonstrated a pronounced upregulation of

S100A8 and

S100A9 in colonic tissues following PEDV challenge, indicating that viral infection provoked a strong inflammatory response in the intestine. The expression levels of inflammation-related genes (

S100A8,

S100A9,

IL-1β, and

REG3G) were markedly decreased after oral Leu treatment, indicating that Leu can lessen inflammation-induced damage brought on by PEDV in porcine colon.

Normal ion transport across membranes is crucial for maintaining intestinal physiological function. The TRPV6 protein facilitates the uptake of Ca

2+ from the intestinal lumen into epithelial cells, whereas the TRPM6 protein acts as the primary Mg

2+ influx channel in the intestinal apical membrane, directly contributing to colonic mucosal Mg

2+ absorption [

41]. This study showed that PEDV infection significantly reduced

TRPV6 and

TRPM6 expression in piglet colon tissue, resulting in compromised intestinal ion transport. This finding is in line with the clinical signs of dehydration and diarrhea that are commonly seen in pigs infected with PEDV. Leu supplementation markedly increased the transcription of

TRPV6 and

TRPM6, implying that Leu supports ionic equilibrium in intestinal epithelial cells through regulation of genes involved in ion transport processes. In summary, this study systematically elucidated that Leu mitigated PEDV-induced colonic injury in piglets via a multifaceted mechanism. These include the restoration of intestinal morphological integrity by modulating CD; the reduction in tissue injury by downregulating

MMP7,

MMP13, and

MUC5AC expression; the inhibition of viral replication by decreasing the expression of PEDV structural proteins (

M,

N,

S); the mitigation of inflammatory damage by suppressing

S100A8,

S100A9,

IL-1β, and

REG3G expression; and the preservation of ionic balance through increased expression of

TRPV6 and

TRPM6. These findings not only elucidate the potential for Leu as a nutritional intervention in managing PEDV infection but also offer novel insights into the mechanisms through which essential amino acids modulate virus-induced intestinal diseases. The research has substantial practical implications for enhancing swine health and increasing production efficiency in pig farming.