Abstract

Using reclaimed water for irrigation is an effective strategy in semi-arid regions facing water scarcity. However, this water may contain pharmaceutical residues, posing potential environmental and health risks. To ensure sustainable reuse, it is essential to study how these substances accumulate in soil and transfer to crops. The aim of this research was to develop and optimise a rapid Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction method combined with Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–tandem Mass Spectrometry for quantifying 23 pharmaceuticals in non-cultivated soil. Following optimisation, 18 compounds were successfully extracted using a MeOH:H2O ratio of 75:25. The detection and quantification limits were found to range from 0.52 to 0.5 ng·g−1 and 1.75 to 35 ng·g−1, respectively. The matrix effects and recoveries varied by compounds’ type and concentration, but most results were acceptable. The evidence suggested that some drugs underwent microbial degradation. Soil irrigated with reclaimed water via subsurface drip since 2012 occasionally contained four pharmaceuticals (caffeine, carbamazepine, tamoxifen, and venlafaxine) at low concentrations, while others were absent. This indicates the capacity of soil to act as a barrier, and highlights the importance of proper water management. The study concludes that reclaimed water reuse is safe if supported by efficient treatment and management, offering a promising approach for long-term sustainability in water-scarce regions.

1. Introduction

Water and food security are global concerns and are key to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals [1]. Agriculture accounts for more than 70% of total water consumption, and water scarcity has a direct impact on the quantity and quality of agricultural products [2].

Climate change is increasing water scarcity in arid and semi-arid areas, making food production more difficult. Non-conventional water resources are one of the alternatives to mitigate the hydrological imbalance between water use and the availability of renewable resources [3], with reuse being necessary to ensure environmental sustainability in these regions [4]. Therefore, one way to adapt to climate change’s impacts is to irrigate with recycled water, which can improve food sovereignty and create opportunities for local people, as irrigated areas increase crop productivity and generate wealth [5]. Reclaimed water (RW) reuse can be considered a reliable water supply and is relatively independent of seasonal droughts and weather variability, being able to meet peak water demand [6]. However, not only the availability of irrigation resources, but also the preservation of the environment and the quality of harvested products must be guaranteed if rural development is to be sustainable.

Perceptions of environmental and health risks, namely the mistrust of standards and products, the scepticism of scientific evidence, and a low belief that reuse can contribute to the fight against climate change, are among the factors that inhibit reuse [7]. One of the most widely recognised environmental and health risks to society is posed by emerging pharmaceutical pollutants (PhCs), which are often detected at low concentrations and are virtually ubiquitous due to their marked persistence, as they are continuously released into the environment despite their rapid degradation [8].

The European Union (EU) maintains a Watch List under the Water Framework Directive to monitor substances that may pose a risk to the aquatic environment. Since its creation in 2008 [9], this list has included various pharmaceutical compounds such as macrolide antibiotics, amoxicillin, diclofenac, sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, venlafaxine and its metabolite O-desmethyl-venlafaxine, fluconazole, clindamycin, metformin, ofloxacin, and ciprofloxacin. This list is reviewed and periodically updated every 2 years to decide whether compounds should be removed from the list, after a continuous monitoring period of 4 years for an individual substance. In the latest update in 2025 [10], the compounds included for monitoring, and therefore those currently under control, are fluoxetine, metformin, and ofloxacin.

Numerous PhCs and their metabolites have been detected in RW due to their incomplete removal by conventional treatment technologies [11,12,13]. Chen et al. [14] identified 510 chemicals in wastewater, with pharmaceuticals being the largest category. Bhattacharjee et al. [15] concluded that even after reverse osmosis treatment, eight PhCs were still detected in the reverse osmosis permeate, albeit at concentrations below 1 ng⋅L−1.

As PhCs are not regulated in the EU regulation on the minimum requirements for water reuse for agricultural irrigation [6], predicting the translocation of organic pollutants to plants is crucial to ensure the quality of agricultural products and to assess the risk of human exposure through the food web [16].

PhCs are substances for which many aspects of their behaviour and their effects on the water/soil/rhizosphere/plant/aquifer system are little known. Their behaviour in agricultural soils is complex and influenced by multiple factors, including the chemical nature of the compounds and the physicochemical properties of the soil, such as clay percent and organic matter contents [17].

In this context, the development of simplified analytical methodologies is essential to ensure routine applicability, especially when monitoring complex matrices such as soil. A multiresidue method that minimises sample handling steps, uses accessible solvents, and achieves acceptable analytical performance allows for broader implementation in environmental surveillance programmes. Moreover, methodological simplification enhances reproducibility, reduces analysis costs, and facilitates integration into regulatory frameworks aimed at monitoring contaminants that are of emerging concern. In this sense, analytical methods based on Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction UAE are usually developed for the multiresidue determination of organic contaminants in solid samples [18,19,20]. The analytical methodologies for PhCs’ determination in agricultural soils detect concentrations commonly around ng·g−1 (ng of PhCs per gram of soil) [16,17,19,21,22].

The presence of emerging compounds (ECs), which have been detected in aquifers [23] and even in aquifers as deep as those of the Macaronesian Islands [24,25,26], represents an obstacle to the reuse of reclaimed water. However, unlike other studies, this team did not detect the presence of emerging contaminants in produce irrigated with artificially contaminated water [27], where the soil acts as a barrier against the transport of these compounds.

To ensure the sustainability of irrigation with RW, the health of the soil receiving these pollutants from such waters must be guaranteed. In this respect, the ‘Soil Health and Food Mission’ aims that by 2030, 75% of soils in each EU country should be healthy soils capable of providing essential services. However, the concrete effects of ECs’ addition on soil fertility in terms of its holistic concept (which depends on the interaction of physical, chemical, and biological processes) or its ability to concentrate PhCs from treated water are still unknown [28].

The process of the root uptake of these PhCs from the soil depends on the chemical speciation of the contaminants, the plant species, the soil type, and on water management. Studies have shown the influence of the properties of micropollutants on their ability to be taken up by roots, and translocated and bioconcentrated in the rest of the plant [29]. Less structured knowledge is published on the remaining variables that condition entry into the food chain or modify environmental conditions. This is mainly due to the difficulties posed by the large number of variables involved in real growing situations. For example, Yu et al. [30] found significant variation in antibiotic accumulation among the 12 Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis cultivars. The authors also concluded that the mobility of antibiotics in the soil is an important factor affecting their bioavailability to plants. In this sense, there is no established method for the determination of many substances with different chemical properties in soils, although it is demonstrated that their adsorption or biodegradation precedes their uptake by roots. The aim of the study is to develop a simple multiresidue methodology to measure PhCs and understand what happens to them in a soil irrigated with RW, in order to distinguish biodegradation from adsorption, and to help estimate their bioavailability for uptake by plant roots and the risk of their entry into the trophic chain, from a ‘one health’ perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

The selected pharmaceuticals were chosen based on their frequent detection in reclaimed water and groundwater in previous regional studies (11–13 and 24–26, respectively), their inclusion in regulatory watch lists (9 and 10), and their diverse physicochemical properties and therapeutic classes (17). They were also chosen because they are frequently reported in the literature (19, 22, 27 and 29), which enables the evaluation of the performance of a useful multiresidue extraction combination. Table S1 lists the PhCs included in this study. Ordered alphabetically, they are Acetaminophen (ACE), Atenolol (ATE), Caffeine (CAF), Carbamazepine (CAR), Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Citalopram (CIT), Cyclophosphamide (CYC), Erythromycin (ERY), Fluoxetine (FLU), Ketoprofen (KET), Levofloxacin (LEV), Metformin (MET), Nicotine (NIC), Norfloxacin (NOR), O-desmethyl-venlafaxine (O-DE), Ofloxacin (OFL), Paraxanthine (PAR), Sertraline (SER), Sulfamethoxazole (SUL), Tamoxifen (TAM), Trimethoprim (TRI), Valsartan (VAL), and Venlafaxine (VEN). The target pharmaceutical compound standards were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain). In addition, their abbreviations, CAS number, chemical structure, and Log Kow are shown in Table S1. The solvents used as extractants and mobile phases (mass spectrometry grade water, acetonitrile, and methanol), all of them with minimum assay of 99.9%, were obtained from Panreac Quimica (Barcelona, Spain). The 0.2 μm syringe polyethylene terephthalate (PET) filters were supplied by Macherey-Nagel (Dueren, Germany). Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA), with a purity of >99%, was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (Madrid, Spain).

2.2. Equipment

The ultrasound extraction was performed using 112xx Series Advanced Ultrasonic Cleaner from Thermo Fisher Scientific and the Vacufuge® plus from Eppendorf. The freeze dryer, a LyoQuest model, was purchased from Telstar (Barcelona, Spain).

The target compounds were determined in an Xevo ACQUITY UHPLC system equipped with a binary solvent manager, a thermostatic autosampler and a tandem triple quadrupole mass spectrometer detector (MS/MS) with electrospray ionisation (ESI). All the components were controlled by the MassLynx Mass Spectrometry software, version 4.1 (Waters Chromatography, Barcelona, Spain). For the chromatographic separation, a ACQUITY BEH C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) was used.

2.3. Experimental Design

Three experiments were designed: experiment 1, aimed to optimise the methodology, using a soil that had never been cultivated or irrigated, and therefore had never previously received EC; experiment 2, intended to analyse the effect of biodegradation versus adsorption; and experiment 3, intended to measure the pharmaceutical compounds in a soil that has been cultivated and irrigated with RW since 2012, with water applied twice a day in low doses using a subsurface drip irrigation system (SDI).

2.4. Soil Characterisation

Samples for each experiment were taken randomly from the soil on the island of Gran Canaria from the surface to a depth of 0.2 m. As mentioned above, for experiment 1, the soil was taken from an undisturbed area while for experiment 2 and 3, soil was taken from a pilot plot irrigated with RW since 2012. For experiment 3, composite soil samples were taken on two dates: in November 2023 (samples 1 to 6) and in March 2024 (samples 7 and 8). More details can be found in Mendoza-Grimón et al. [31] on climate and initial soil characteristics. Soil characterisation data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Soil characterisation for experiments (Exp) 1, 2, and 3.

The total carbon (TC, %) and total nitrogen (Ntot, %) were determined by dry combustion with an LECO TruMac CN 2000 analyser (LECO Corporation, St. Joseph, MI, USA). The organic matter (OM) values were indirectly deduced by applying the ‘Van Bemmelen’ factor of 1.724 to organic carbon after subtracting inorganic carbon (measured by a soil calcimeter) from TC. Soluble salts were estimated by electrical conductivity EC 1:5 (soil:water ratio; dS·m−1). The available nitrate was determined by soil extraction at the 1:5 ratio with 0.01 M calcium chloride, and was analysed by ionic chromatography. Available soil P (mg⋅kg−1) was determined by sodium bicarbonate extraction according to the method of Olsen and Sommers [32] and the UV–spectrophotometry molybdenum blue method of Murphy and Riley [33]. Exchangeable cations (K, Ca, Mg, and Na, meq⋅100 g−1) were extracted with buffered 1 M ammonium acetate, pH 7, B in hot water (mg⋅kg−1). Metals (Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn, mg⋅kg−1) were diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-extracted, at pH 7. They were all analysed by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). The soil texture was determined by the Bouyoucos method [34]. For experiment 2, sterilised and non-sterilised soil were used. Air-dried soil was autoclaved at 121 °C at 1.1 atm for 20 min and for 3 days. Between each autoclaving cycle, the soil was incubated at 25 °C. All the analyses were carried out at the Laboratorio Agroalimentario del Cabildo de Gran Canaria.

2.5. Extraction Procedure

Four solvent ratios were evaluated to optimise the extraction of compounds: MeOH–ultrapure water (pH 3, formic acid (FA) 0.5%, 0.1%EDTA), 50:50 (v/v); MeOH–ultrapure water (pH 3, FA 0.5%), 50:50 (v/v); MeOH, 0.25% FA; and MeOH–ultrapure water (pH 3, FA 1%), 75:25 (v/v). The best extraction procedure was obtained using MeOH–ultrapure water (pH 3, FA 1%), 75:25 (v/v) to extract the compounds.

To optimise the method, triplicates of 1 g freeze-dried soil were placed in a plastic centrifuge tube (50 mL), spiked with the target compounds dissolved in MeOH (1 mL total volume), mixed carefully, and kept in contact at 4 °C overnight.

The sample was extracted three times with 20 mL of the optimised solvent ratio by vortexing for 1 min, followed by ultrasonic extraction for 15 min at 50 °C and centrifugation for 10 min at 3750 rpm and 20 °C. After the three extraction phases, the supernatant was centrifuged for 5 min (3750 rpm) and a 6 mL aliquot was collected in a glass test tube and evaporated to dryness at 45 °C.

The reconstitution of the analytes was performed with 0.7 mL ultrapure water–MeOH, 90:10 (v/v). Finally, the extract was centrifuged for 5 min at 7400 rpm (20 °C) and transferred to a glass vial for Ultra-high-performance Liquid Chromatography–MS/MS (UHPLC-MS/MS) analysis.

To distinguish biodegradation from adsorption (testing microbiological degradation), the soil samples sterilised by tyndallisation (ST) and samples not tyndallised (SNT) were processed to test microbiological degradation at different PhCs concentrations. The tyndallisation procedure involved autoclaving the samples for 20 min at 120 °C and 1 atm, followed by storage at 25 °C overnight for three days. The samples were then frozen for 24 h before being lyophilised. The effects of tyndallisation were analysed statistically using the least significant difference test in Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 29.

2.6. Determination Procedure

The mobile phase for the chromatographic separation consists of MeOH (A) and water (B) with 0.5% (v/v) acetic acid at a flow rate of 0.3 mL⋅min−1. The following gradient was employed: 90% A:10% B as initial conditions, 90% A:10% B at 0.56 min, 40% A:60% B at 3.83 min, and 10% A:90% B at 6.93 min and held until 7.42 min. At 7.91, the system returns back to its initial conditions and is allowed to equilibrate until 9 min for the next injection. The injected extract volume was 10 μL.

For detection and quantification via mass spectrometry, the ESI parameters were fixed as follows: capillary voltage at 3.5 kV, cone voltage at 60 V, extractor at 3 V, RF lens 2.5 V, source and desolvation temperature at 150 °C and 450 °C, respectively, and desolvation gas flow at 1000 L·h−1. The UAE is widely used for PhAC extraction (19, 20), with parameters selected based on referenced articles (18–20). Similarly to other authors, the extraction temperature was not used to be evaluated (20). Nitrogen was used for desolvation and argon for collision. Detailed information about the fragmentation of target analytes is showed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Conditions for the mass spectrometry detection.

2.7. Quality Control

The linearity, the limits of detection (LODs), limits of quantification (LOQs), reproducibility (relative standard deviation, RSD %), extraction efficiencies, and matrix effect were calculated. Calibration curves were prepared for the selected compounds. Eight points were plotted within a concentration range from 0.25 to 50 ng·mL−1, resulting in linear coefficients (>0.960) for each compound. LODs and LOQs were determined based on the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of individual compound responses at the lowest point of the calibration curve, assuming minimum detectable S/N levels of three and ten, respectively. Reproducibility, extraction efficiencies, and the matrix effect were assessed by adding known quantities of a standard mixture to sample to achieve a concentration of between 0.5 and 50 ng·mL−1 in the final theoretical extract.

The matrix effect was assessed by comparing the chromatographic peak area at each level of the calibration curve using the extract obtained after soil extraction against a pure methanol standard. This approach allows for the evaluation of the extent to which the matrix affects the analytical response. Matrix effect values below one indicate signal suppression due to matrix interferences, while values above one suggest signal enhancement. A ratio between 0.7 and 1.3 is considered acceptable, as it suggests minimal interference from the sample matrix on the analytical response.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Extraction Solvent Study

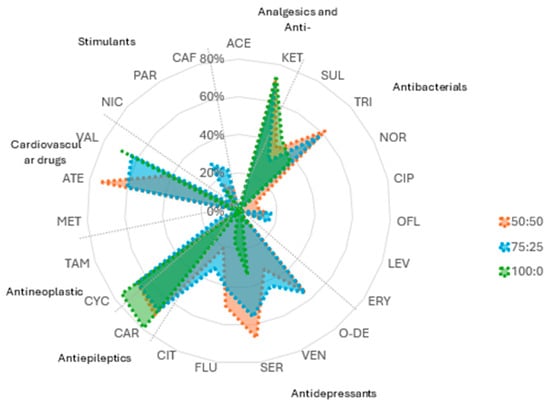

Methanol content significantly influences the solubility and desorption of pharmaceuticals from soil. To evaluate its effect, the extraction efficiency of the target pharmaceutical compounds was tested using MeOH:H2O ratios of 50:50, 75:25, and 100:0. The results highlight that hydrophobic compounds, such as CAR (79.0%), KET (73.9%), and VAL (68.5%), achieve the highest recoveries with pure methanol (100:0), confirming their strong affinity for organic solvents. In contrast, moderately polar pharmaceuticals, including ATE and VEN, were best extracted with a 75:25 MeOH:H2O mixture, where they reached recoveries of 42.9% and 36.7%, respectively. This suggests that a combination of organic and aqueous phases optimises solubilization while minimising interactions with the soil matrix. Some compounds, such as MET and ERY, showed consistent 0% recovery across all solvent conditions. The presence of ionic functional groups in these molecules reduces their desorption efficiency even further, indicating the need for alternative extraction strategies, such as adjusting the pH or using chelating agents.

A balanced solvent composition is essential for maximising analyte recovery. The 75:25 MeOH:H2O mixture proves to be the most versatile, facilitating the extraction of both moderately polar and non-polar pharmaceuticals. For example, CAR exhibited a recovery of 67.2% under this condition, while TRI reached 58.4%, indicating that this ratio effectively accommodates compounds with diverse polarities. In contrast, aqueous-rich conditions (50:50 MeOH:H2O) enhanced the recovery of some polar compounds, with ATE reaching its highest value at 74.9% and TRI at 62.0%, but remained ineffective for highly hydrophilic substances. This reinforces the effectiveness of mixed solvents in environmental extractions, where diverse chemical properties must be considered.

Figure 1 illustrates the variation in extraction efficiency across different solvent compositions, confirming that non-polar compounds are best recovered with pure methanol, whereas aqueous-rich mixtures improve the extraction of polar pharmaceuticals. The intermediate 75:25 MeOH:H2O ratio provides a suitable compromise, yielding moderate to high recoveries across a broader range of compounds. These findings underscore the importance of selecting an appropriate solvent system based on the physicochemical properties of the target analytes.

Figure 1.

Recovery efficiency of different pharmaceutical compounds across the tested MeOH:H2O ratios.

Changes in the method and experimental conditions could improve the extraction process of some pharmaceuticals from soil but worsen the determination of other compounds. The choice of polar extractant (75:25 MeOH:H2O) was made based on agronomic criteria to evaluate the absorption intensity factor of these substances by plants. Our results agree with those of Huidobro-López et al. [35], who conclude that the determination in soil, due to its complexity, requires a prior extraction treatment that affects the recovery of some analytes, making it difficult to develop a methodology that allows the determination of multiple residues. To reduce the LOQ, it may be useful to explore less polar solvents that will access the reservoirs of these less soluble substances, which could improve the extraction of some substances that may be partially bioavailable for root uptake. However, their movement in the soil will be limited due to their low solubility in water and methanol. It is therefore a compromise between obtaining good recoveries and adequately simulating the root uptake process.

3.2. Analytical Parameters

3.2.1. Linearity, Detection, and Quantification Limits and Reproducibility

Although we started by making internal calibration curves from 0.25 to 50 µg·L−1, different linear ranges were studied for each compound, and we finally chose the ones with the best possible linearities, as presented in Table 3. The LODs and LOQs were between 0.52 and 10.5 ng·g−1, and 1.75 and 35.0 ng·g−1, respectively. Regarding the reproducibility (RSD %), at five different concentrations, better results were obtained for the three highest concentrations (35, 70, and 350 ng·g−1) with all percentages below 24.7%, except for fluoxetine, which was 35 ng·g−1 with 28.3%. At lower concentrations (3.5 and 7.0 ng·g−1), percentages exceeding 25% for more compounds were obtained (CAF, CIT, and PAR). Furthermore, it was more frequent to not to be able to analyse or not to be able to extract pharmaceuticals at low concentrations. Lastly, only four compounds (CIP, LEV, NIC, and OFL) could not be determined to be reproducible because they could not be adequately extracted under the conditions for this multiresidue procedure.

Table 3.

Linearity, LODs (ng·g−1), LOQs (ng·g−1), and RSD (%) for selected pharmaceuticals.

3.2.2. Extraction Recoveries

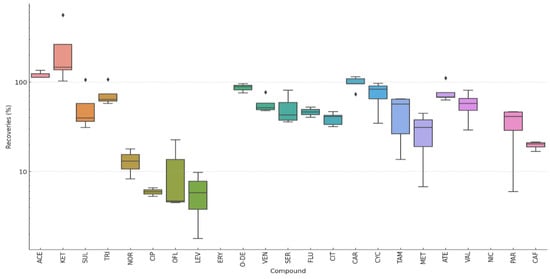

The recovery profile of the analytical method across the evaluated pharmaceuticals revealed considerable variability depending on the compound and its chemical class. As shown in Figure 2 and Table S2, compounds such as ACE, KET, and CAR exhibited high recovery rates because they are predominantly neutral (pKa > 4.5) under the acidic MeOH:H2O extraction conditions, and therefore less prone to strong ionic binding to soil components (clays/metal sites). At the same time, their log Kow value of between 0.5 and 3.1 gives them good performance in a 25:75 MeOH:H2O. In addition, KET displays a maximum value of 560.8% at the lowest tested concentration (0.5 µg·L−1), likely due to strong matrix effects or co-extraction phenomena.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of recoveries for target pharmaceuticals sorted by pharmacological families.

In contrast, very low recoveries were observed for fluoroquinolone antibiotics such as NOR, CIP, OFL, and LEV, which ranged from 1.8% to 22.7%, highlighting the poor compatibility of the method with this highly polar and zwitterionic class. The macrolide ERY showed non-detectable recovery at both 10 and 50 µg·L−1. Among the antidepressants, O-DE and VEN yielded moderate-to-high recoveries between 48% and 95.8%, whereas CIT and FLU were more variable, especially at higher concentrations. Stimulants such as NIC exhibited zero recovery across all levels tested, underscoring the critical limitations of the method for this group. Nicotine can interact with organic matter in the soil, such as humus and humic acids, through hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic interactions. Due to its basic nature (amine group), it can also bind to charged surfaces such as clays and minerals. While methanol increases the solubility of organic compounds, the water/methanol ratio may not be ideal for desorbing nicotine from soil. These results demonstrate the need for analyte-specific optimisation, particularly when targeting compounds from diverse pharmacological classes with varying physicochemical properties.

The recoveries obtained were low at the lowest concentrations. This result is explained by the variability of the characteristics of the PhCs included in this multiresidue study; the molecular weights were between 129.2 g·mol−1 (MET) and 733.94 g·mol−1 (ERY) and Kow was between −1.3 (MET) and 7.1 (TAM), from very low to high affinity for adipose tissue. However, they are similar to those reported in other scientific articles. For example, our results coincide with those obtained by García-Valverde et al. [36] in their comparative study of extraction methods in soil at 50 ng·g−1 (higher than those used in this study; see Table 3). These authors obtained the best results with a solid–liquid extraction method. They obtain average recoveries of 46% for some of the methods compared and mention the impossibility of recovering other pharmaceuticals (as in our study). For example, these authors mention recoveries of only 5% for two substances: OFL and CIP (20% and 6%, respectively, in our study). In agreement with the recovery of 25% obtained by Malvar et al. [37], with our method, CYC is not sufficiently recovered while CAR is recovered with 53%, in the range obtained in our study (40–60%). It should be noted that MET is well recovered at low concentrations, being the compound with a molecular weight and Kow close to that of CYC, although it is more soluble and polar than CYC. Similarly, NIC, which is also poorly recovered, is highly soluble; although, unlike MET, it is moderately polar and has a positive Kow. Further studies are needed to better understand this result, as among the properties of PhCs, charge and lipophilicity are the most critical for the translocation and accumulation of PhCs in soil [38].

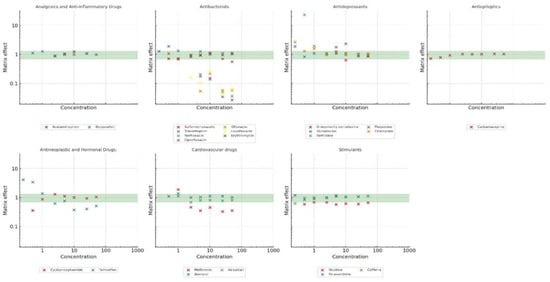

3.3. Study of Matrix Effect

The matrix effect varied across pharmaceutical families, as shown in Figure 3. While no universally accepted threshold exists, values close to one are preferred, and effects within ±30% are often considered manageable without extensive signal correction. Analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs exhibited a relatively stable response, with a mean matrix effect of 1.05 ± 0.12. Most values remained within the acceptable range, with a minimum of 0.88 and a maximum of 1.28, indicating that the extraction method is effective for this group and that matrix interferences are minimal. Antiepileptics showed a similar trend, with a mean of 0.95 ± 0.13 and values ranging from 0.72 to 1.05, suggesting a moderate but acceptable suppression effect in some cases.

Figure 3.

Analytical signal changes for the target pharmaceuticals. Values > 1 indicate signal enhancement and values < 1 indicate signal suppression.

In contrast, antibacterials exhibited the strongest matrix suppression among all groups, with an average value of 0.62 ± 0.51. The minimum recorded value was 0.027, indicating extreme suppression for some compounds, while the highest value was 1.92, showing that a few compounds also experienced enhancement. The wide variability in matrix effect suggests that individual antibacterial compounds behave very differently, likely due to differences in their physicochemical properties. Given that the lowest matrix effect values were associated with this group, it is likely that certain compounds are not being efficiently extracted, leading to the underestimation of their concentrations.

Antidepressants showed a mean matrix effect of 1.22 ± 0.47, with values ranging from 0.64 to 2.68. This suggests that most compounds in this group remain within the acceptable range, but a few show moderate signal enhancement, possibly due to interactions with matrix components that improve ionisation efficiency. Antineoplastic and hormonal drugs also showed moderate variability, with a mean of 1.21 ± 1.09, ranging from 0.35 to 4.10. While the median value (0.94) is within the acceptable range, the presence of high matrix effect values suggests that some compounds may be strongly influenced by matrix interferences. This could be related to their hydrophobic nature, which may lead to enhanced retention in the solid matrix and co-elution with endogenous interferences.

The matrix effect also varied across different concentration levels. At low concentrations (≤2.5 µg·L−1), antibacterial compounds were particularly affected, with strong signal suppression in some cases (values close to 0.027). This suggests that, at trace levels, these compounds are more prone to ion suppression effects, possibly due to co-eluting matrix components. In the intermediate concentration range (5–25 µg·L−1), the matrix effect remained more stable for most compounds, with values clustering closer to the acceptable range. At higher concentrations (50 µg·L−1), some compounds, particularly certain antineoplastic drugs, exhibited significant signal enhancement, with values exceeding 4.0 in some cases. This could be attributed to an increased availability of the analyte in the ionisation process, reducing competition effects and enhancing response.

The observed trends in the matrix effect could be influenced by the extraction protocol employed. The optimised method used methanol and ultrapure water (pH 3, FA 1%) (75:25 v/v), selected based on its ability to recover a broad range of pharmaceuticals from soil. Fluoroquinolones, for example, are known to form strong complexes with metal ions and organic matter in environmental matrices, which may limit their recovery. Alternative strategies, such as adjusting the solvent composition or pH, may be necessary to improve their extraction efficiency.

It is important to note that chelating agents like EDTA, which were considered as an option for improving recovery, were ultimately discarded due to salt precipitation, which negatively affected the extraction efficiency and reduced the recovery of several pharmaceuticals. This suggests that, although EDTA can facilitate the release of bound compounds, its incompatibility with the extraction system used in this study makes it unsuitable for soil samples with high ionic content. Thus, it is confirmed that the enhancement of recovery rates of PhCs from soil samples employing EDTA depend on the PhCs’ class and on the soil’s properties [39,40].

3.4. Effect of Biodegradation and Adsorption

Regarding the results of the recovery studies to distinguish biodegradation from adsorption (ST/SNT), the following compounds show significant differences due to tyndallisation: ACE, ATE, CAR, CYC, KET, TRI, and VAL, with no significant effect for the rest of the PhCs (Table 4). A more detailed description of these results can be found in the study by Fernández-Vera et al. [41]. As can be seen from these results, biodegradation seems to be an important factor for some pharmaceuticals, even when its effect was analysed in samples at 4 °C. On the other hand, it should also be considered that some substances may be released if some microaggregates are modified in the process of tyndallisation. Therefore, further studies are needed to better understand the possibility of the absorption of these drugs by plant roots.

Table 4.

Results of the recovery studies to distinguish biodegradation from adsorption using soil samples sterilised by tyndallisation (ST) and samples not tyndallised (SNT).

Consequently, the soil’s ability to retain and degrade emerging RW contaminants [42] provides safety for irrigated food. However, for the rhizosphere to act as a barrier to the uptake of these contaminants, it must receive low concentrations that can be inactivated as they are supplied. Thus, the water must have a sufficient level of treatment so as not to damage the soil microbiota, guaranteeing the sustainability of the reuse system. Natural purification systems, which are very well adapted to the rural environment, when well designed and operated, provide an adequate level of water treatment [12]. Treated water thus becomes a valuable resource, particularly in arid and semi-arid areas such as those that characterise, for example, many of the Macaronesian islands of West Africa. The use of this resource, as opposed to its discharge, is becoming increasingly necessary because of water scarcity, which is accentuated by climate change.

3.5. Application to Real Samples

Once the method had been optimised and validated, PhCs were measured in samples from a soil irrigated with RW for more than 10 years. As presented in Table 1, this is a basic, saline soil with high levels of OM (2.9%), N (0.19% total N), P (87 mg·kg−1 of P-Olsen) and B (7 mg·kg−1 of B in hot water). More details about this soil can be found in Mendoza-Grimón et al. [31].

Of the 18 pharmaceuticals detected in the reclaimed irrigation water (see Table S3), only three were found in the soil: CAF, CAR, and VEN, as well as TAM (Table 5). These compounds all belong to the group with the lowest LOQ value (1.75 ng·g−1) and the lowest linear concentration range (0.25–2.5 µg·L−1). As shown in Table 5, only CAR was detected in all soil samples, so it is important to plan its monitoring, even though the concentrations were all below the LOQ. CAF and VEN were quantified in three samples, while TAM was quantified in only one sample. Also, the higher detection in March 2024 may be associated with higher water dosage due to higher water demand because of evapotranspiration. Although present in the irrigation water, the rest of the pharmaceuticals analysed were not detected in any of the samples. This is a rare result, which suggests that water management is a critical factor influencing the behaviour of PhCs in the soil. Therefore, SDI is a promising way to ensure the sustainability of RW reuse.

Table 5.

Results from real soil samples (ng·g−1).

As already expressed, apart from the analytical conditions, pharmaceutical concentrations in soils are influenced by compound-specific properties, soil characteristics, water management, environmental conditions, and the release rate to the environment, and are markedly linked to agronomic management. Furthermore, it is important to consider that the study of pharmaceuticals in SDI irrigated soils is an emerging issue and there is no extensive bibliography available. The concentrations detected in this study are between 0.32 and 10.3 ng·g−1, coinciding with ranges reported by others [17,21,22]. The ubiquitous presence of the anticonvulsant CAR in the studied soils is consistent with bibliography, which reported that this compound is notably persistent in soils, with limited biodegradation observed under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions [17,43]. The detection of the stimulant CAF and the antidepressant VEN can be attributed to their high consumption, giving rise to continuous concentration from the WWTP. In fact, it has been reported that CAF has also been ubiquitous detected in groundwater of Gran Canaria [25].

4. Conclusions

The research successfully developed and validated an analytical method based on the Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction procedure combined with UHPLC-MS/MS for the multiresidue analysis of emerging pharmaceutical contaminants in agricultural soil samples.

The soil itself was found to significantly influence the extraction efficiency and recoveries of the compounds. However, the use of a 75:25 MeOH:H2O mixture (acidified with 1% FA at pH 3) provided a good compromise for analytical conditions of 23 pharmaceuticals with a wide range of physicochemical properties including predominantly neutral or weakly ionised species under acidic conditions, moderate lipophilicity, and a limited tendency to form strong ionic or metal-complex interactions with soil components.

The validated method was applied to the determination of soil samples from a plot irrigated with reclaimed water for more than 10 years. Only four compounds were detected in the soil samples: CAF, CAR, TAM, and VEN. CAR was the only compound detected in all soil samples, and it was found to be the most persistent. The quantification of CAF and VEN occurred on three occasions, while TAM was only quantified on one occasion. Its presence after a decade of irrigation with reclaimed water encourages the establishment of strategies and continuous monitoring for those compounds that may have a high environmental stability. In addition, the biodegradation study revealed that the drugs are susceptible to microbial degradation. The null detection of the remaining compounds suggests that the soil irrigated with water applied twice daily at low doses and from the subsurface is a critical factor influencing the behaviour of PhCs. Therefore, the soil irrigated with the described water management has the capacity to act as a barrier preventing the uptake of these contaminants by the crop. Therefore, the subsurface irrigation system is a promising way to ensure the sustainability of RW reuse.

The results of this research support the use of reclaimed water for agricultural irrigation in areas where water is scarce, provided that efficient water treatment and management is carried out, and the physical, chemical, and biological health of the soil is assessed. Further studies are needed to improve the extraction procedure and better simulate root absorption. This will help us understand all the variables affecting the absorption of PhCs by plant roots.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010095/s1. Table S1: Characteristics of studied pharmaceutical compounds; Table S2: Recoveries for target pharmaceuticals sorted by pharmacological families; and Table S3: Mean concentration of pharmaceuticals (ng·L−1) in the reclaimed water used for irrigation in Experiment 3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M.-G., J.R.F.-V., Z.S.-F. and M.d.P.P.-D.; methodology, V.M.-G., R.G.-A., J.R.F.-V. and S.M.-E.; validation, V.M.-G., J.P.-J., R.G.-A., J.R.F.-V. and M.d.P.P.-D.; formal analysis, R.G.-A. and M.d.P.P.-D.; investigation, V.M.-G., R.G.-A., J.R.F.-V., E.E., S.M.-E. and M.d.P.P.-D.; resources, V.M.-G. and M.d.P.P.-D.; data curation, J.P.-J., R.G.-A., J.R.F.-V., S.M.-E. and M.d.P.P.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.-G., J.P.-J., R.G.-A., E.E., S.M.-E. and M.d.P.P.-D.; writing—review and editing, V.M.-G., J.P.-J., R.G.-A., J.R.F.-V., S.M.-E., Z.S.-F. and M.d.P.P.-D.; supervision, V.M.-G. and M.d.P.P.-D.; project administration, V.M.-G. and M.d.P.P.-D.; and funding acquisition, V.M.-G. and M.d.P.P.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Gobierno de Canarias (ProID2025010013), Fundación CajaCanarias-Fundación Bancaria La Caixa (2022CLISA28), and University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (CEI2021-03) projects helped with financing.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Laboratorio Agroalimentario y Fitopatológico del Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria for collaborating in the work. Javier Pacheco-Juárez also thanks the Consejería de Universidades, Ciencia e Innovación y Cultura of the Canary Islands Government, for his predoctoral grant with reference FPI2024010005 co-funded by the European Social Funds (FSE+).

Conflicts of Interest

All the authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789213589755 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Dalezios, N.R.; Angelakis, A.N.; Eslamian, S.S. Water scarcity management: Part 1: Methodological framework. Int. J. Glob. Environ. Issues 2018, 17, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Fernández-Vera, J.; Hernández-Moreno, J.; Palacios-Díaz, M. Sustainable Irrigation Using Non-Conventional Resources: What has Happened after 30 Years Regarding Boron Phytotoxicity? Water 2019, 11, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Díaz, M.P.; Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Fernández, F.; Fernandez-Vera, J.R.; Hernandez-Moreno, J.M. Sustainable Reclaimed Water Management by Subsurface Drip Irrigation System: A study case for forage production. Water Pract. Technol. 2008, 3, wpt2008049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P.; Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Hernández-Moreno, J.M.; Amorós, R.; Mendoza-Grimón, V. Effect of Irrigation Management and Water Quality on Soil and Sorghum bicolor Payenne Yield in Cape Verde. Agriculture 2023, 13, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EU Regulation 2020/741 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 May 2020 on minimum requirements for water reuse (Text with EEA relevance). Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, 177, 32–55. [Google Scholar]

- Duckett, D.; Troldborg, M.; Hendry, S.; Cousin, H. Making waves: Promoting municipal water reuse without a prevailing scarcity driver. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapworth, D.J.; Baran, N.; Stuart, M.E.; Ward, R.S. Emerging organic contaminants in groundwater: A review of sources, fate and occurrence. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 163, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on environmental quality standards in the field of water policy, amending and subsequently repealing Council Directives 82/176/EEC, 83/513/EEC, 84/156/EEC, 84/491/EEC, 86/280/EEC and amending Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 348, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2025/439 of 28 February 2025 establishing a watch list of substances for Union-wide monitoring in the field of water policy pursuant to Directive 2008/105/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (notified under document C(2025) 1244). Off. J. Eur. Union 2025, 439. [Google Scholar]

- Guedes-Alonso, R.; Montesdeoca-Esponda, S.; Pacheco-Juárez, J.; Sosa-Ferrera, Z.; Santana-Rodríguez, J.J. A Survey of the Presence of Pharmaceutical Residues in Wastewaters. Evaluation of Their Removal using Conventional and Natural Treatment Procedures. Molecules 2020, 25, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.D.A.D.J.B.M.; Guedes-Alonso, R.; Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Montesdeoca-Esponda, S.; Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Sosa-Ferrera, Z.; Santana-Rodríguez, J.J.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P. Water quality for agricultural irrigation produced by two municipal sewage treatment plants in Santiago Island-Cape Verde: Assessment of chemical parameters and pharmaceutical residues. Water Reuse 2023, 13, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alcalá, I.; Guillén-Navarro, J.M.; Lahora, A. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals in a wastewater treatment plant from southeast of Spain and risk assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 279, 111565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xia, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, R.; Huang, M.; Tang, T.; Lu, G. Tracing contaminants of emerging concern and their transformations in the whole treatment process of a municipal wastewater treatment plant using nontarget screening and molecular networking strategies. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Oussadou, S.E.; Mousa, M.; Shabib, A.; Semerjian, L.; Semreen, M.H.; Almanassra, I.W.; Atieh, M.A.; Shanableh, A. Fate of emerging contaminants in an advanced SBR wastewater treatment and reuse facility incorporating UF, RO, and UV processes. Water Res. 2024, 267, 122518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, L. Prediction of organic contaminant uptake by plants: Modified partition-limited model based on a sequential ultrasonic extraction procedure. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gworek, B.; Kijeńska, M.; Wrzosek, J.; Graniewska, M. Pharmaceuticals in the Soil and Plant Environment: A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago-Ferrero, P.; Borova, V.; Dasenaki, M.E.; Thomaidis, Ν.S. Simultaneous determination of 148 pharmaceuticals and illicit drugs in sewage sludge based on ultrasound-assisted extraction and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 4287–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejías, C.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites in sewage sludge and soil: A review on their distribution and environmental risk assessment. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 30, e00125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.A.; Albero, B. Ultrasound-assisted extraction methods for the determination of organic contaminants in solid and liquid samples. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 166, 117204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.J.; Harris, E.; Williams, M.; Ryan, J.J.; Kookana, R.S.; Boxall, A.B.A. Fate and Uptake of Pharmaceuticals in Soil–Plant Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 816–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.; Adhikari, M.D.; Agarwal, S.M.; Samanta, P.; Sharma, A.; Kundu, D.; Kumar, S. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in soil: Sources, impacts and myco-remediation strategies. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Tan, J.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Huang, G.; Huo, Z. Assessment of the environmental health and human exposure risk of emerging contaminants in groundwater of a typical agricultural irrigation area in the North China Plain. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estevez, E.; Cabrera, M.D.C.; Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Molina-Díaz, A.; Robles-Molina, J.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P. Monitoring priority substances, other organic contaminants and heavy metals in a volcanic aquifer from different sources and hydrological processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 551–552, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, E.; Cabrera, M.D.C.; Molina-Díaz, A.; Robles-Molina, J.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P. Screening of emerging contaminants and priority substances (2008/105/EC) in reclaimed water for irrigation and groundwater in a volcanic aquifer (Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 433, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesdeoca-Esponda, S.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P.; Estévez, E.; Sosa-Ferrera, Z.; Santana-Rodríguez, J.J.; Cabrera, M.D.C. Occurrence of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Groundwater from the Gran Canaria Island (Spain). Water 2021, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Fernandez-Vera, J.R.; Hernandez-Moreno, J.M.; Guedes-Alonso, R.; Estevez, E.; Palacios-Díaz, M.D.P. Soil and Water Management Factors That Affect Plant Uptake of Pharmaceuticals: A Case Study. Water 2022, 14, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel-Maeso, M.; Corada-Fernández, C.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Removal of personal care products (PCPs) in wastewater and sludge treatment and their occurrence in receiving soils. Water Res. 2019, 150, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klampfl, C.W. Metabolization of pharmaceuticals by plants after uptake from water and soil: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 111, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y. The accumulation and distribution of five antibiotics from soil in 12 cultivars of pak choi. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Grimón, V.; Hernández-Moreno, J.M.; Palacios-Díaz, M.d.P. Improving Water Use in Fodder Production. Water 2015, 7, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommers, L.E. Phosphorus. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties; Page, A.L., Ed.; Amer Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 403–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 1962, 27, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Directions for making mechanical analysis of soils by the Hydrometer Method. Soil Sci. 1936, 42, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huidobro-López, B.; López-Heras, I.; Alonso-Alonso, C.; Martínez-Hernández, V.; Nozal, L.; De Bustamante, I. Analytical method to monitor contaminants of emerging concern in water and soil samples from a non-conventional wastewater treatment system. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1671, 463006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Valverde, M.; Martínez Bueno, M.J.; Gómez-Ramos, M.M.; Aguilera, A.; Gil García, M.D.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Determination study of contaminants of emerging concern at trace levels in agricultural soil. A pilot study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malvar, J.L.; Santos, J.L.; Martín, J.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Comparison of ultrasound-assisted extraction, QuEChERS and selective pressurized liquid extraction for the determination of metabolites of parabens and pharmaceuticals in sludge. Microchem. J. 2020, 157, 104987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Mordechay, E.; Mordehay, V.; Tarchitzky, J.; Chefetz, B. Fate of contaminants of emerging concern in the reclaimed wastewater-soil-plant continuum. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cheng, M.; Li, W.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Y.; Christie, P.; Zhang, H. Simultaneous extraction of four classes of antibiotics in soil, manure and sewage sludge and analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with the isotope-labelled internal standard method. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mravcová, L.; Amrichová, A.; Navrkalová, J.; Hamplová, M.; Sedlář, M.; Gargošová, H.Z.; Fučík, J. Optimization and validation of multiresidual extraction methods for pharmaceuticals in Soil, Lettuce, and Earthworms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 33120–33140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Vera, J.R.; Mendoza Grimón, V.; Estevez, E.; Guedes Alonso, R.; Montesdeoca Esponda, S.; Pacheco Juárez, J.; Sosa Ferrera, M.Z.; Palacios Díaz, M.D.P. ¿Qué pasa con los contaminantes emergentes que llegan al suelo cuando se riega con aguas regeneradas? Metodología multi-residuo y efectos de la esterilización de las muestras del suelo. In Proceedings of the 1st Congress Bridge to Africa, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 20–25 May 2024; Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2024; pp. 49–50. Available online: http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9601912 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Pagano, M.; Correa, E.; Duarte, N.; Yelikbayev, B.; O’Donovan, A.; Gupta, V. Advances in Eco-Efficient Agriculture: The Plant-Soil Mycobiome. Agriculture 2017, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelusmond, J.R.; Kawka, E.; Strathmann, T.J.; Cupples, A.M. Diclofenac, carbamazepine and triclocarban biodegradation in agricultural soils and the microorganisms and metabolic pathways affected. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 640–641, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.