Abstract

Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.), a specialty crop with ecological, medical, and economic value in Ningxia province of China, is subject to severe damage from Aphis gossypii Glover. Currently, A. gossypii populations show extremely high-level resistance to beta-cypermethrin in the major wolfberry planting areas in Ningxia. The specific resistance mechanisms, however, are still not known. In this work, we collected a field A. gossypii strain (HSP) from a wolfberry orchard in Ningxia in 2021 using a single-time sampling method, and its resistance to beta-cypermethrin was determined to be extremely high (994.74-fold) as compared with that of a susceptible strain (SS). Then we explored the potential resistance mechanisms from two aspects, namely, metabolic detoxification and target-site alterations. Bioassays of beta-cypermethrin with or without a synergist showed that piperonyl butoxide (PBO) significantly increased the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin (4.72-fold) to the HSP strain, while triphenyl phosphate (TPP) and diethyl maleate (DEM) exhibited no significant synergistic effects. Correspondingly, the O-demethylase activity of cytochrome P450s in the HSP strain was 1.68-fold higher than that in the susceptive strain (SS), whereas changes in carboxylesterases and glutathione S-transferases activities were unremarkable. Also, fifteen upregulated P450 genes were identified by both RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR technologies, containing eleven CYP6 genes, three CYP4 genes, and one CYP380 gene. Especially, five CYP6 genes with high relative expression levels (>3.00-fold) were intensively expressed by beta-cypermethrin induction in the HSP aphids. These metabolism-related results indicate the key role of P450-mediated metabolic detoxification in HSP resistance to beta-cypermethrin. Sequencing of voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) genes identified a prevalent M918L mutation and a new G1012D mutation in HSP A. gossypii. Moreover, heterozygous 918 M/L and 918 M/L + G1012D mutations were the dominant genotypes with frequencies of 60.00% and 36.67% in the HSP population, respectively. Overall, VGSC mutations along with P450-mediated metabolic resistance contributed to the extremely high resistance of the HSP wolfberry aphids to beta-cypermethrin, providing support for A. gossypii control and resistance management in the wolfberry planting areas of Ningxia using insecticides with different modes of action.

1. Introduction

Chinese wolfberry, a genus of deciduous perennial shrub (Lycium barbarum L.) of the Solanaceae family, distributed in the northwest, arid regions of China, is a crop of high ecological value with a capacity to ameliorate wind erosion and improve soil structure [1]. Moreover, the wolfberry fruits have also been widely used as a foodstuff and as an herbal medicine [2], which makes it a crop of economic importance. Currently, Ningxia wolfberry fields represent the largest cultivated area in China, due to the suitable natural conditions producing wolfberries of the best nutraceutical quality with the highest market value [3,4]. However, in recent years, Chinese wolfberry has been suffering from severe Aphis gossypii Glover damage in the Ningxia province of China [5,6]. Chemical insecticides have been intensively employed to control A. gossypii in many agricultural areas of China [7]. Beta-cypermethrin is a representative member that is also commonly used to control A. gossypii on the Chinese wolfberry plants in Ningxia. Due to long-term over-application, A. gossypii has developed different levels of resistance to beta-cypermethrin on multiple crops in China [7,8,9]. Our previous study revealed that the A. gossypii populations in eight major wolfberry planting areas of Ningxia regions had all developed extremely high-level resistance to beta-cypermethrin, with resistance ratios ranging from 2539.70 to 31,916.00 [10]. However, few studies have focused on the resistance mechanisms of A. gossypii populations to beta-cypermethrin in the Chinese wolfberry fields of Ningxia. Thus, in this study, we expand our previous study to explore the deeper molecular characterization underlying the beta-cypermethrin resistance in a field with a highly resistant population, in terms of metabolic detoxication and the discovery of new target-site mutations.

A. gossypii can be resistant to insecticides through four major ways [7,11,12], including target-site insensitivity, enhanced detoxification, reduced penetration, and behavioral avoidance or apastia. Notably, metabolic mechanisms governed by the increased activity or overexpression of detoxifying enzymes, as well as target-site mechanism in terms of insect sodium channel mutations, have been frequently reported to account for pyrethroid resistance in multiple aphid species [7,13,14,15]. Three groups of detoxifying enzymes, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s) [16,17,18,19], carboxylesterases (CarEs) [20,21,22], and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) [23,24,25], were demonstrated to play key roles in beta-cypermethrin resistance in diverse pest insects, including aphid species [7,18,26]. In addition, P450s were verified to potentially contribute to pyrethroid resistance by increased activity in A. gossypii, including that against three cypermethrin pesticides: beta-cypermethrin [7], cypermethrin [27], and alpha-cypermethrin [8]. Of note, the major mechanism responsible for pyrethroid resistance in insects is attributed to point mutations in the target protein of the voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC), which reduces sensitivity to pyrethroids [14,15,28]. There are up to now more than 50 VGSC mutations identified to be associated with pyrethroid resistance in various invertebrates, and the majority of the mutation sites are located in domain II, a potential pyrethroid-binding site within the VGSC [14,15]. Among those, the super knockdown resistance (kdr) mutation, M918L, in the linker connecting DIIS4 and DIIS5, has been widely detected in pyrethroid-resistant A. gossypii populations [7,29,30,31], producing extremely high resistance levels to beta-cypermethrin (>2000.00) [7]. Apart from existing independently, the M918L mutation also occurs in combination with other mutation sites to enhance pyrethroid resistance levels in some insect species [14,32]. It is noteworthy that the co-occurrence of M918L with other point mutations has been scarcely observed in field populations of A. gossypii. Therefore, one of the objectives of this study is to explore whether the co-occurring VGSC mutations are involved in beta-cypermethrin resistance in wolfberry A. gossypii. Yet, to our knowledge, the roles of the three detoxification enzymes and VGSC mutations remain unclear in the beta-cypermethrin resistance of the Chinese wolfberry aphids in the Ningxia region.

In the present study, we collected a beta-cypermethrin-resistant A. gossypii strain (HSP) from a Chinese wolfberry orchard in a major growing area of Ningxia wolfberry (Wuzhong city). Subsequently, to elucidate the potential roles of P450s, CarEs, and GSTs in beta-cypermethrin resistance in the A. gossypii strain, we performed synergistic bioassays, as well as enzyme activity assays to confirm their effects. Further, we carried out a comparative transcriptome analysis to identify the overexpression of detoxification enzyme genes associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance. According to the transcriptome variations, we also measured the expression levels of the upregulated P450 genes involved in beta-cypermethrin resistance in the A. gossypii resistant strain, using a quantitative real-time PCR assay. Moreover, the potential mutations in VGSC genes and their frequencies were detected to reveal the VGSC genotype of the resistant strain. Our findings provide valuable insights into the potential resistance mechanisms of Ningxia wolfberry A. gossypii to pyrethroids and will also contribute to the design of improved strategies for resistance management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Beta-cypermethrin (96.6% purity) was obtained from Shaanxi Meibang Pesticide Co., Ltd. (Xi’an, China). Piperonyl butoxide (PBO, 95.0% purity), triphenyl phosphate (TPP, 99.0% purity), and diethyl maleate (DEM, 99.0% purity) were purchased from Sun Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Tween 80 (99.0% purity), ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, 99.5% purity), dithiothreitol (DTT, ≥97.0% purity), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, ≥98.0% purity), glycerol (99.0% purity), α-naphthyl acetate (α-NA, 98.0% purity), 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB, ≥99.0% purity), and p-nitroanisole (PNOD, 98.0% purity) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Insects

The relatively susceptible colony of A. gossypii (SS) was originally collected in 2021 from wild Chinese wolfberry plants in the Yinchuan area of Ningxia (latitude 38.47 N, and longitude 106.21 E), China. This population was ascertained to be relatively susceptible to beta-cypermethrin compared with the field population by laboratory bioassays. The resistant A. gossypii field population was collected in 2021 from a Chinese wolfberry plantation in the Hongsipu district of Wuzhong City in the Ningxia province of China (termed HSP strain, latitude 37.37 N and longitude 106.07 E). These two A. gossypii populations were reared separately on Wolfberry plants in mesh cages (60 cm × 60 cm × 150 cm) without exposure to any insecticide under controlled conditions of 25 ± 1 °C and a 16:8 h light/dark photoperiod. After collection, each aphid strain was reared indoors for three generations (about 40 days) under standardized conditions without any selection pressure before being subjected to experiments.

2.3. Bioassays

The toxicity of beta-cypermethrin to A. gossypii was determined using a previously described leaf-dipping method [7]. Prior to the bioassays, beta-cypermethrin was dissolved in acetone and diluted with distilled water containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80 to prepare the stock solutions. Preliminary range-finding assays were conducted to define the concentration range of beta-cypermethrin. Five beta-cypermethrin concentrations (625, 1250, 2500, 5000, and 10,000 μg·mL−1) were used to evaluate its toxicity to the HSP A. gossypii. To determine the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin to the SS A. gossypii, the final beta-cypermethrin concentrations were set as 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, and 7.5 μg·mL−1, respectively. Wolfberry leaves of relatively identical morphology were dipped for 15 s in an insecticide solution of a desired concentration or in distilled water containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80 as a control. Treated leaves were air-dried naturally, then placed upside down in 90 mm Petri dishes (five leaves per Petri dish), with each bottom lined with a 9 cm sheet of moist filter paper. Uniform apterous A. gossypii adults were selected and transferred onto the treated leaves (five individuals per leaf). Each Petri dish was then covered with a layer of transparent plastic wrap with pinholes and incubated in a growth cabinet at 25 ± 1 °C with a 16:8 h light/dark photoperiod. Each treatment was carried out in triplicate, and at least 30 aphids were monitored for each repetition. Aphid mortality was checked after a 24 h incubation. The median lethal concentration (LC50 value) was calculated using the probit package of SPSS 23.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The confidence intervals of LC50 values were compared statistically to assess significance between the two strains at p < 0.05. The resistance ratio (RR) was estimated using the LC50 value of the SS strain as the factor divisor [16,17].

2.4. Synergistic Bioassays

To reveal the enzyme inhibitor synergism effects, stocks of PBO, TPP, and DEM were prepared in acetone and diluted with distilled water containing 0.01% (v/v) Tween 80. The maximum dose that generated no more than 10% mortality in both HSP and SS strains was utilized as the testing concentration in this study [7]. The maximum sublethal doses of PBO, TPP, and DEM for the SS strain were determined to be 50 mg·L−1, 20 mg·L−1, and 30 mg·L−1, respectively, according to the bioassay method depicted in Section 2.3. Synergistic bioassays were performed as per a previously described method [12]. Briefly, apterous A. gossypii adults were exposed to wolfberry leaves that were pretreated with desired insecticide solutions containing an enzyme inhibitor at its maximum sublethal concentration. The subsequent operations were performed as described in Section 2.3. The synergistic ratio (SR) was defined as the ratio of the LC50 value without synergist to the LC50 value with synergist [7,12].

2.5. Enzyme Activity Analysis

Aliquots of A. gossypii samples (50 mg) from different strains were separately homogenized on ice in the corresponding buffer solutions of 4 mL of 40 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) for CarE and GST assays [33,34] and 1 mL of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.6, containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 10% glycerol) for the P450 assay [33]. The obtained homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C, and then the supernatants were collected as the enzyme sources. The protein content of each enzyme source was determined according to the Bradford method [35], using a PC0010 Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China).

The CarEs’ activity was determined using α-NA as a substrate according to the procedures described by Shi et al. [33]. The GSTs’ activity was measured using CDNB as a substrate following the method described by Shi et al. [33]. Following the procedures described by Shi et al. [33], the activity of P450s was assayed by detecting the O-demethylation of PNOD. Each detoxification enzyme activity assay was performed with three biological replicates and three technical replicates.

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

Briefly, 100 mg of apterous adults of SS and HSP strains with the identical conditions were used for total RNA extraction. Total RNA samples were prepared using an RNAiso Plus kit (Takara, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The total RNA quality was monitored by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and with a Thermo Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE, USA) via the values of OD260/280 and OD260/230. Three replicates were carried out for each strain.

Library construction and sequencing were completed at Biomarker Technologies Company Ltd. (Qingdao, China) with three replicates for each strain. The cDNA library sequencing was performed by an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing platform generating paired-end reads. High-quality clean reads were obtained by removing sequencing adapters, poly-N regions, and low-quality reads from the raw sequencing data. Raw data has been deposited in the GEO database (accession no. GSE314727). The obtained high-quality sequencing data was mapped to the A. gossypii genome ASM401081v1 [36] as a reference using HISAT2 [37]. StringTie [38] was then applied to the assembly of the mapped reads to reconstruct a unigene library. To eliminate effects of gene lengths and sequencing levels, read counts were standardized with fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped fragments (RPKM). The DEseq2 package was used to remove possible batch effects prior to DEG analysis and then to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the SS and HSP strains, with false discovery rate (FDR) values ≤ 0.01 and absolute values of |log2Fold Change| ≥ 1.0 as the threshold for significantly differential expression [39]. Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were used to predict the functions and molecular pathways of the DEGs [39]. DEGs encoding cytochrome P450 enzymes were screened according to the DEG function annotations. Then the obtained P450 DEG sequences were realigned by blastx in NCBI [40]. Finally, the amino acid sequences of the P450 DEGs and their respective highly homologous protein sequences of identified families were used to construct a phylogenetic tree to determine the preliminary classification of the P450 DEGs [41], using the MEGA 12.0 program.

2.7. Reverse Transcriptase Quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

RNA extraction was carried out according to the protocols described above (Section 2.6). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with a gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR was performed in an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-Time System (Waltham, MA, USA), using the SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Ten DEGs were selected randomly for qRT-PCR to validate the transcriptome results. The relative expression of 17 upregulated P450s genes (termed as AgoCYPup1 to AgoCYPup17) was also determined by this method. Beta actin (β-ACT), a house keeping gene, was used as the internal reference gene for A. gossypii [42]. Gene primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and the optimal primers are listed in Table S1 via primer optimization. The amplification program is present in Table S2. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Three independent biological replicates were carried out for each experiment.

2.8. VGSC Mutation Analysis in A. gossypii

Total RNA was extracted from apterous adults of A. gossypii as described in Section 2.6. Full-length VGSC genes (VGSC1 and VGSC2) were amplified with the primer pairs listed in Table S3 using a Takara PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase (Dalian, China). The major mutant regions of VGSC1 (DIIS1–DIIS6) and VGSC2 (DIIIS6–DIVS4) fragments were also amplified with specific primer pairs (Table S3). The PCR amplification program for VGSC mutation analysis is listed in Table S4. PCR products were directly subjected to paired-end sequencing [15] by TSINGKE Biological Technology (Beijing, China).

2.9. Determination of VGSC Mutation Frequencies in A. gossypii

Genomic DNA was extracted from 30 individual adults of the HSP population with an Omega Bio-tek EZNA® Insect DNA Kit (Norcross, GA, USA). A specific primer (Table S3) was used to amplify the genomic DNA fragment of VGSC1 gene covering the detected mutation sites (DIIS4–DIIS6 containing intron sequences) using the Takara PrimeSTAR® GXL DNA Polymerase (Dalian, China). PCR products were obtained according to a recommended procedure in the instruction manual (Table S4) and directly subjected to sequencing in both directions by TSINGKE Biological Technology (Beijing, China).

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Significant differences were analyzed in SPSS 23.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) using the Student’s t-test, with a significance level set at p ≤ 0.05. The classification of resistance levels referred to the standards of the World Health Organization (WHO): extremely high resistance ≥ 160-fold ≥ high resistance ≥ 40-fold ≥ moderate resistance ≥ 10-fold ≥ low resistance ≥ 5-fold ≥ decreased susceptibility ≥ 3-fold ≥ susceptibility [15,43]. Nucleotide sequences were analyzed using Chromas 2.6.6 and GeneDoc 2.7.

3. Results

3.1. Resistance of the HSP A. gossypii to Beta-Cypermethrin

The susceptibilities of the field-collected A. gossypii population HSP and SS strain to beta-cypermethrin were evaluated, with results listed in Table 1. The SS strain showed a very low LC50 value of 2.33 μg·mL−1 to beta-cypermethrin. The LC50 value of the HSP strain (2317.74 μg·mL−1), however, was determined to be significantly higher than that of the SS, indicating the extremely high-level resistance of the HSP strain to beta-cypermethrin with a RR (resistance ratio) value of 994.74.

Table 1.

Resistance of HSP and SS A. gossypii populations against beta-cypermethrin and the synergistic effects of PBO, TPP, and DEM on beta-cypermethrin toxicity in resistant HSP A. gossypii.

3.2. Effect of Synergists on A. gossypii Resistance to Beta-Cypermethrin

The toxicity of beta-cypermethrin with a synergist (PBO, TPP, or DEM) to the HSP population was monitored, with results shown in Table 1. Only PBO significantly increased the beta-cypermethrin toxicity, displaying a much lower LC50 value of 491.23 μg·mL−1. The SR (synergistic ratio) value was determined to be 4.72 with PBO treatment. Nevertheless, both TPP and DEM exerted no distinct effects on the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin against the HSP A. gossypii, exhibiting equivalent LC50 values to the SS strain with 2169.48 μg·mL−1 for TPP and 2441.71 μg·mL−1 for DEM, respectively. These results indicate that metabolic resistance mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes was involved in the beta-cypermethrin resistance of the HSP A. gossypii.

3.3. Detoxification Enzyme Activities

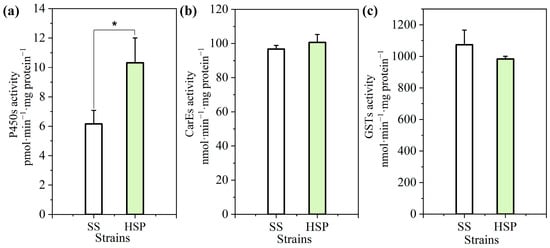

The differences in three metabolic enzyme activities were compared between the SS and HSP strains. As illustrated in Figure 1, there were no significant differences observed in both the carboxylesterases’ (CarEs’) and glutathione S-transferases’ (GSTs’) activities between the susceptible and resistant strains, whereas the cytochrome P450 O-demethylase activity of the HSP strain was 1.68-fold higher than that of the SS strain. These findings provide evidence for the key role of cytochrome P450 metabolism in the HSP A. gossypii resistance to beta-cypermethrin, consistent with the PBO synergistic effect on the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin.

Figure 1.

Detoxification enzyme activities of cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (P450s) (a), carboxylesterases (CarEs) (b), and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) (c) in the SS and HSP strains of A. gossypii. The enzyme activities were expressed as nanomoles or picomoles of substrate converted per minute per milligram of extracted protein, and 50 mg of each A. gossypii sample was used for detection. The error bars represent means ± standard deviations. The asterisk (*) in the plot represents significant difference between the SS and HSP strains at p < 0.05.

3.4. Comparative Transcriptomics of the SS and HSP Strains

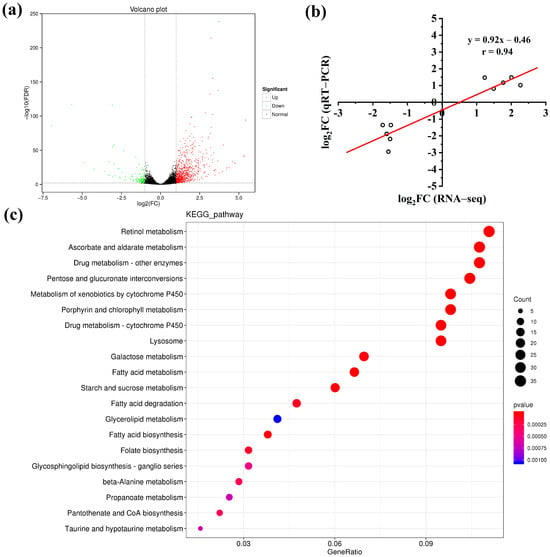

To gain insights into the molecular variations underlying the beta-cypermethrin resistance of the HSP A. gossypii, transcriptome profiling assays were performed to identify the relative differentially expressed genes (DEGs) as compared with the SS strain. Each cDNA library produced a data pool containing clean reads ranging from 39,722,998 to 63,552,688 and mapped reads ranging from 37,260,918 to 56,654,337, with mapped ratios above 88.74% (Table S5). The Q30 percentages were over 94.72% for all the sample reads, indicating that the Illumina RNA-Seq data obtained are reliable. A total of 913 DEGs were identified in the HSP strain, with 766 upregulated genes and 147 downregulated genes (Table S5). The expression level difference and statistically significant degree of all DEGs are illustrated by a volcano plot (Figure 2a). To verify the accuracy of the transcriptome sequencing results for DEGs, five upregulated and five downregulated genes were randomly selected, and their expression levels were measured by the qRT-PCR technology. As depicted in Figure 2b, the expression patterns of these ten DEGs were highly consistent by these two methods with a high correlation (r = 0.94), indicating that the RNA-Seq data are credible. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis was further performed to determine the specific biochemical pathways of the identified DEGs, with results shown in Figure 2c. Among the top 20 enriched KEGG pathways, those related to substance metabolism account for 65%. Moreover, two P450-related KEGG pathways, namely, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 and drug mentalism-cytochrome P450, were significantly enriched in the top 10 KEGG pathways. These results imply that the detoxification effect of cytochrome P450 metabolism may participate in the development of beta-cypermethrin resistance in the HSP wolfberry aphids.

Figure 2.

(a) Volcano plot of all differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the SS and HSP strains, with green spots showing downregulated DEGs and red spots showing upregulated DEGs. (b) Correlation between the logarithmic fold changes of qRT-PCR (y-axis) and RNA-Seq (x-axis) in the gene expression levels. (c) Top 20 enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. DEGs were identified using false discovery rate (FDR) values ≤ 0.01 and absolute values of |log2Fold Change| ≥ 1.0 as the cutoff thresholds. Ten DEGs were selected randomly for the correlation analysis.

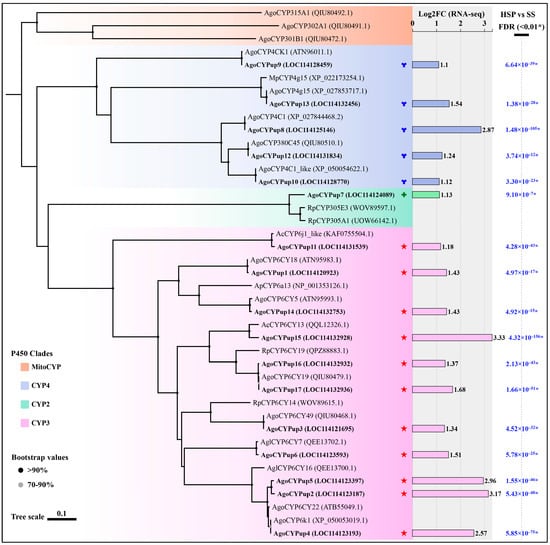

3.5. Cytochrome P450 DEGs and Phylogenetic Analysis

Given the facts of the significant synergistic effect of PBO on the beta-cypermethrin toxicity to the HSP strain, the enhancement in P450 O-demethylase activity in the HSP strain, and the two P450-related metabolism pathways enriched in the top 10 KEGG pathways, we analyzed the A. gossypii transcriptome data of the SS and HSP strains and obtained 17 upregulated cytochrome P450 genes (AgoCYPup1–AgoCYPup17) (Table S6). No downregulated cytochrome P450 DEGs were screened by the gene function annotations of Nr, Pfam, and Swiss-Prot databases. Phylogenetic analysis was further carried out using the putative amino acid sequences of these P450 DEGs and other P450 amino acid sequences from multiple insects (Myzus persicae Sulzer, Rhopalosiphum padi L., Aphis craccivora Koch, Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris, and Aphis glycines Matsumura) to determine their specific family classification. Figure 3 shows that these P450 DEGs were classified into three clades and four families of P450 genes [41]. Eleven P450 DEGs, AgoCYPup1 to AgoCYPup6, AgoCYPup11, and AgoCYPup14 to AgoCYPup17, belong to clade CYP3 family CYP6. AgoCYPup7 belongs to clade CYP2 family CYP305. Four P450 DEGs, AgoCYPup8 to AgoCYPup10 and AgoCYPup13, belong to clade CYP4 family CYP4. AgoCYPup12 belongs to clade CYP4 family CYP380.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of 17 upregulated cytochrome P450 DEGs (AgoCYPup1–AgoCYPup17) and their differential expression folds with FDR value (<0.01) from the transcriptome data. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining (NJ) method using amino acid sequences of Aphis gossypii Glover (Ago), Myzus persicae Sulzer (Mp), Rhopalosiphum padi L. (Rp), Aphis craccivora Koch (Ac), Acyrthosiphon pisum Harris (Ap), and Aphis glycines Matsumura (Agl). Bootstrap analysis was performed for the assignment of phylogeny with 1000 replications, and the values > 70% are marked on each node of the tree. Bootstrap values below 70% are simply not shown. Green, pink, blue, and orange backgrounds represent the CYP2, CYP3, CYP4, and mitochondrial clades of cytochrome P450s, respectively, according to the similarity of their amino acid sequences. Asterisk (*) represents that the false discovery rate (FDR) value is below 0.01.

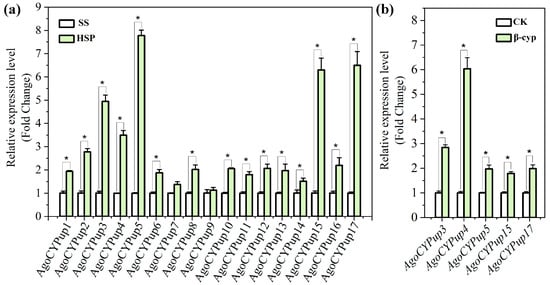

3.6. Relative Expression Levels of the Cytochrome P450 DEGs

The qRT-PCR method was employed to confirm the relative expression levels of the seventeen cytochrome P450 DEGs. As shown in Figure 4a, the expression patterns of these genes measured by qRT-PCR were equivalent to those obtained by the transcriptome data (Figure 3), in spite of the differences in the fold changes of each gene. Except for AgoCYPup7 and AgoCYPup9, fifteen other genes were significantly upregulated in the HSP strain. Of note, the expression levels of five P450 genes (AgoCYPup3 to AgoCYPup5, AgoCYPup15, and AgoCYPup17) in the HSP strain were over 3-fold higher than those in the SS strain. Thus, to further explore the relationship between the P450 genes and beta-cypermethrin resistance in the HSP A. gossypii, the expression levels of these five genes were observed under beta-cypermethrin treatment at LC50 for 12 h in the surviving HSP individuals. The mRNA in dead individuals generally degrades rapidly so that only the surviving HSP individuals were used to measure the induction of beta-cypermethrin in P450 gene expression regardless of the possible slight enhancement effect caused by the partial sampling method. As illustrated in Figure 4b, the expression levels of all the five P450 genes increased significantly in the HSP strain after beta-cypermethrin treatment. AgoCYPup4 exhibited a highest expression level (6.04-fold) in the HSP strain after the induction of beta-cypermethrin. These results show that overexpression of the 15 P450 genes is associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance in the HSP A. gossypii and that the five P450 genes of AgoCYPup3, AgoCYPup4, AgoCYPup5, AgoCYPup15, and AgoCYPup17 may play key roles in the formation of HSP A. gossypii’s resistance to beta-cypermethrin due to their high-level expressions with and without beta-cypermethrin treatment.

Figure 4.

(a) Relative expression of 17 upregulated cytochrome P450 DEGs in the HSP strain as compared with those in the SS strain. (b) Relative expression of 5 highly upregulated cytochrome P450 DEGs (over 3-fold) with (β-cyp) and without (CK) beta-cypermethrin treatment in the HSP strain. The HSP aphids were treated with beta-cypermethrin at 2317.74 μg·mL−1 (LC50 value) for 12 h, and then only the surviving individuals were used for the qRT-PCR analysis. The error bars represent means ± standard deviations. The asterisks (*) in the plots represent significant difference at p < 0.05.

3.7. Target-Site Mutations and Frequencies

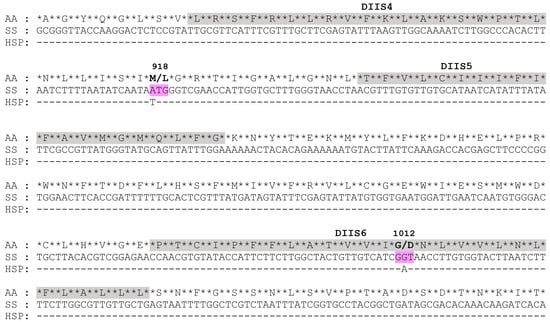

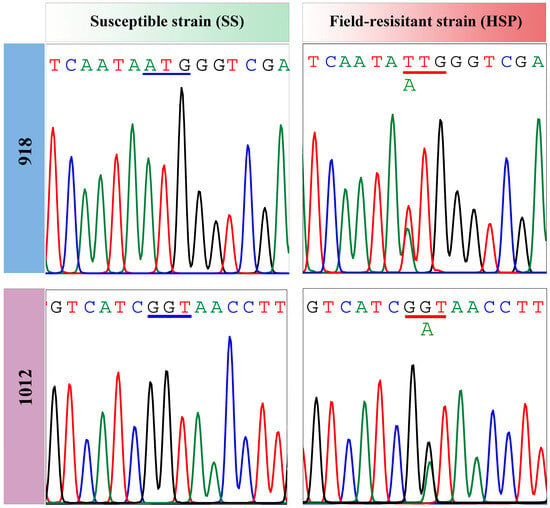

To identify non-synonymous mutations in the target VGSC gene, full-length VGSC genes (VGSC1 and VGSC2), as well as their major mutant fragments (DIIS1–DIIS6 and DIIIS6–DIVS4), were amplified and sequenced. Compared with the susceptible strain (SS), the cDNA sequences of VGSC in the HSP A. gossypii population varied at two positions, resulting in amino acid substitutions in the putative polypeptide (Figure 5). The first nucleotide point mutation was determined as M918L, a change from ATG to TTG corresponding to the non-synonymous substitution of methionine with leucine at the amino acid residue 918 (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The second nucleotide mutation was a change from GGT to GAT in terms of the replacement of 1012 glycine with aspartic acid (G1012D) (Figure 5 and Figure 6), which, to our knowledge, has not been found yet in any insect species. To further explore the genotypes and their mutation frequencies in the HSP field population, a genomic DNA fragment of VGSC covering the two mutation sites (M918L and G1012D) was amplified from individual adults. The representative nucleotide sequence chromatograms of the VGSC gene fragment covering the 918 and 1012 sites are shown in Figures S1–S3. At codon 918, only the heterozygous allele 918L mutation was observed in the HSP strain with a mutation frequency of 96.67% (Table 2). At codon 1012, a total of 36.67% of the HSP individuals had heterozygous allele 1012D mutations, whereas no homozygous 1012D mutation was detected (Table 2). Therefore, two mutation genotypes including two heterozygous mutations of 918M/L and 918M/L + 1012G/D were detected in the HSP A. gossypii strain, with frequencies of 60.00% and 36.67%, respectively, suggesting its key role in the development of the resistance of the HSP wolfberry aphids to beta-cypermethrin.

Figure 5.

Partial cDNA sequences and their deduced amino acid sequences (AAs) of VGSC in the SS and HSP strains. Two mutated codons are highlighted. The asterisks (*) in the plot represent base gaps.

Figure 6.

Partial nucleotide sequence chromatograms of the 918 and 1012 loci of VGSC in the SS and HSP strains.

Table 2.

The potential genotypes of VGSC and their frequencies in the HSP strain.

4. Discussion

A. gossypii is one of the most destructive pest insects in Chinese wolfberry fields, leading to challenges such as insecticide resistance and population management [44]. Long-term frequent insecticide applications have caused pyrethroid resistance in many field populations of A. gossypii [7,10,29,30] and many other aphid species [15,30]. Beta-cypermethrin is a major pyrethroid that has been widely used to control aphids in multiple crop fields of China in the last several decades [7,10,26,45,46], due to its low price and high efficacy. Chen et al. (2017) [7] found that A. gossypii field populations had evolved extremely high levels of resistance to beta-cypermethrin in the major cotton growing areas of China, with resistance ratios (RRs) ranging from 2159 to over 40,000. Our previous resistance monitoring data indicated that eight field populations of wolfberry aphids had all developed very high resistance to beta-cypermethrin in the major producing areas of Ningxia in China, with RRs ranging from 2539.70 to 31,916.00 [10]. Nowadays, elucidating the resistance mechanisms to pyrethroids of pest insects is particularly important for the design of appropriate management strategies. However, few studies have focused on the exploration of the resistance mechanism of wolfberry aphids to beta-cypermethrin. Thus, in the current work, we expand our previous study to investigate the beta-cypermethrin resistance mechanism of a HSP field-resistant population with a 994.74-fold resistance level as compared with the susceptible strain.

Enhanced metabolic detoxification has been reported as a direct resistance mechanism in many pyrethroid-resistant insects. Currently, two methods, i.e., the synergistic effect determination of detoxifying enzyme inhibitors and detoxifying enzyme activity assay, are commonly used to determine the metabolic capacity of detoxifying enzymes [7,40]. Cytochrome P450 enzymes are important enzymes for detoxifying exogenous toxic chemicals including insecticides, contributing to the resistance of aphids to pyrethroids [7,30,47,48]. A previous study revealed that the P450 inhibitor piperonyl butoxide (PBO) significantly increased the toxicities of both α-cypermethrin (24.47-fold) and cyfluthrin (11.06-fold) against an A. gossypii resistant strain [48]. Chen et al. (2017) found that the synergistic effect of PBO on the toxicity of beta-cypermethrin (3.50-fold) was significant to a pooled A. gossypii population comprising various field populations [7]. The activity of P450 enzymes in multiple insecticide-resistant populations has been also reported to be significantly increased compared with that in their respective susceptible strains [19,40,49]. Our results from this study show that the synergistic ratio (SR) of PBO to the HSP A. gossypii was 4.72-fold, while two other detoxifying enzyme inhibitors, TPP and DEM, showed no synergistic effects on the HSP strain, with SR values of 1.07 and 0.95, respectively. Consistently, the O-demethylase activity of the cytochrome P450s in the HSP strain was 1.68-fold higher than that in the SS strain, whereas changes in activities of the other two detoxifying enzymes of CarEs and GSTswere not remarkable. These results reveal that the activity increasing of cytochrome P450s is a very important factor in the HSP A. gossypii.

Besides the increased activity of specific P450s, it has also been widely demonstrated that overexpression of P450 genes is also an important molecular mechanism for metabolic resistance [16,19,30,40,47], because it can upregulate the amount of P450 enzymes. For instance, seven P450 genes, namely, CYP6CY19, CYP6CZ1, CYP6CY51, CYP6DA1, CYP6DC1, CYP4CH1, and CYP4CJ5, were significantly upregulated in an R. padi resistant strain to lambda-cyhalothrin [47]. In our present study, 17 upregulated cytochrome P450 genes were identified by the comparative transcriptomics analysis between the SS and HSP strains. The qRT-PCR method was also used to confirm the results of the transcriptome data. Although the expression trends of these 17 upregulated genes were identical between these two methods, the expression levels of two P450 DEGs identified by transcriptome were not statistically significant by the qRT-PCR method. These divergences in the gene expression levels may be attributed to the differences between the RPKM and 2−ΔΔCt methods [50,51]. Besides constitutive overexpression, inducible expression by insecticides can also contribute to the increased expression of P450 genes [16]. Therefore, we further detected the inducible expression of five CYP6 family genes with high relative expression levels (>3-fold), and the results showed that these five P450 genes were all significantly expressed under the induction of beta-cypermethrin in the HSP wolfberry aphids. Overall, of the 15 upregulated P450 genes identified by both RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR, especially five CYP6 family genes of high relative expression levels, may play a key role in beta-cypermethrin resistance in wolfberry aphids. The individual contributions of these genes to metabolic resistance, however, still need to be further explored by RNA interference (RNAi) or heterologous expression studies.

Target-site alteration is another major resistance mechanism to pyrethroid insecticides. Pyrethroids including beta-cypermethrin target VGSCs and then modify the gating transitions by altering the activation/inactivation kinetics of the channel, finally disrupting normal nerve function and leading to paralysis and death [15,32]. The major mechanism responsible for pyrethroid resistance in pest insects is caused by VGSC mutations that reduce sensitivity to pyrethroids [15,32]. Currently, over 50 pyrethroid resistance mutations have been identified in various insect species, with various unique and multiple substitutions [14,15,29]. In A. gossypii, however, the kdr (L1014F) and s-kdr (M918L) mutations in the target VGSC are the most studied and are widely regarded as the primary mechanism of resistance to pyrethroids. The mutation M918L in the linker connecting DIIS4 and DIIS5 was first identified in a fenvalerate-resistant strain of A. gossypii with an extremely high resistance level of 199.54-fold. Subsequently, this mutation was described in multiple pyrethroid-resistant field strains of A. gossypii [7,27,29,30]. For example, a field A. gossypii strain from Cameroon was reported to carry the heterozygous M918L mutation with extremely high resistance to cypermethrin (473.00-fold). Chen et al. (2017) found that 96.8–100% of individuals with the M918L mutation were observed in multiple A. gossypii populations that evolved extremely high resistance levels to beta-cypermethrin ranging from 2159-fold to over 40,000-fold [7]. In addition to the commonly reported M918L mutation, another substitution of M918V was also identified in A. gossypii populations collected from Xinjiang province of China [52]. However, other substitutions at M918 (T/I) have been only described in resistant populations of other aphid species [15,29,30]. In this study, only heterozygous substitution of M918L was identified in the HSP wolfberry aphids, and no L1014F was observed. These results are in line with the previous research findings that M918L and L1014F are yet to be found together in field A. gossypii populations and that the heterozygous M918L mutation is prevalent in field populations in China and Cameroon in terms of a potential fitness cost associated with this mutation in the homozygous form [29,30]. Interestingly, another new heterozygous mutation of G1012D was also found in the HSP strain which, to our best knowledge, has never been screened against existing VGSC mutation databases or aligned with VGSC sequences from related aphid species. So far, most of the mutation sites occur in domain II, forming the pyrethroid-binding site with domain I and domain III [14]. L1014F is the first reported kdr mutation in pyrethroid-resistant populations across evolutionarily divergent insect species [14,15]. In DIIS6, adjacent to the 1014 locus, mutations I1011M and V1016G were reported to reduce the sodium channel sensitivity to two pyrethroids, namely, permethrin and deltamethrin [14,53]. Since G1012 is also located at the pyrethroid receptor sites, we speculate that G1012D mutation might affect the action of pyrethroids like beta-cypermethrin. Furthermore, co-occurrence of more than one mutation often leads to a higher resistance level to pyrethroids than individual ones [14]. For instance, the double mutation L1014F + M918T almost abolished the VGSC sensitivity to deltamethrin, whereas the L1014F or M918T mutation alone only caused about a 5–10-fold reduction in the sensitivity [14,54,55]. Therefore, the double mutation M918L + G1012D may also act synergistically to increase the beta-cypermethrin resistance in the HSP wolfberry aphids with a high mutation frequency of 36.67%. Yet, the relationship between the G1012D mutation and resistance and the synergistic effect of M918L and G1012D mutations on resistance still need to be further investigated.

The development of extremely high insecticide resistance is commonly associated with multiple resistance mechanisms. Generally, resistance mechanisms to insecticides are complicated in terms of target-site variations, enhancement in detoxification, reduced transportation and penetration, and behavioral avoidance or apastia [26,30]. Among these, metabolic and target-site mechanisms have been frequently reported to account for pyrethroid resistance [26]. The combined effect of these two mechanisms can usually lead to extremely high insecticide resistance levels in insects including aphids [7,26,27,45,47]. For example, only several overexpressed P450 genes were identified in the A. gossypii strains with medium to high level of resistance to dinotefuran (74.7-fold), whereas both the target alteration and P450 gene overexpression were found in an A. gossypii strain with extremely high resistance (>2300-fold) to the same type of insecticide, thiamethoxam [47]. The target-resistance-associated VGSC mutation along with enhanced detoxification was also demonstrated to contribute to the extremely high resistances to beta-cypermethrin in A. gossypii populations from China (>2000-fold) [7] and to cypermethrin in a Burk A. gossypii population from Cameroon (473.00-fold) [27]. In our current work, the O-demethylase activity of the HSP strain was only 1.68-fold higher than that of the SS strain, and the resistance of the HSP strain to beta-cypermethrin still reached to an extremely high level (210.83-fold) with the PBO inhibition. These results cannot explain the extremely high resistance to beta-cypermethrin of the HSP wolfberry aphids (994.74-fold) thoroughly. Therefore, based on the discussion above, we can conclude that the VGSC mutations in combination with metabolic detoxification confer extremely high resistance on the HSP wolfberry aphids to beta-cypermethrin. Generally, metabolic detoxification can confer pesticide resistance ranging from low to high levels, while target-site alteration can cause extremely high-level resistance. Thus, we speculate that the VGSC mutations might be the main-acting metabolism. The specific contribution of P450-mediated metabolism and target alterations to resistance, however, still needs to be further studied to fully understand the relationship between different resistance mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a wolfberry aphid population (HSP) of extremely high-level resistance to beta-cypermethrin was collected and used as a model to uncover the potential resistance mechanisms. Cytochrome P450-mediated enhancement in metabolic detoxification follows a resistance-associated pattern. Heterozygous 918M/L and 918M/L+ G1012D mutations contribute to the beta-cypermethrin resistance of the HSP wolfberry aphids. Both the VGSC mutations and the enhanced P450 metabolism resistance were found as the mechanisms for the extremely high beta-cypermethrin resistance of the HSP aphids. These results indicate that pyrethroid insecticides should not be employed for control of A. gossypii in the wolfberry planting areas of Ningxia, and rotary application of other insecticides with different action targets will be beneficial for resistance management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010083/s1: Figure S1: Representative nucleotide sequence chromatogram of the VGSC gene fragment covering the 918 and 1012 sites without any mutations; Figure S2: Representative nucleotide sequence chromatogram of the VGSC gene fragment covering the 918 and 1012 sites with a 918M/L heterozygous mutation; Figure S3: Representative nucleotide sequence chromatogram of the VGSC gene fragment covering the 918 and 1012 sites with both 918M/L and 1012G/D heterozygous mutations. Table S1: Primers for qRT-PCR assay; Table S2: Amplification program for qRT-PCR assay; Table S3: Primers for amplifying VGSC gene of Aphis gossypii; Table S4: Amplification program for VGSC mutation analysis; Table S5: Summary RNA-Seq data of HSP and SS A. gossypii populations; Table S6: List of upregulated cytochrome P450 enzyme DEGs in the A. gossypii resistant population of HSP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and S.Z.; methodology, F.W.; software, X.H.; validation, Y.Z., S.Z., and J.Y.; formal analysis, J.C.; investigation, Y.Z., X.H., and J.C.; resources, F.W.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, S.Z. and F.W.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, F.W.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. and F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (Grant No. 2025BBF01001) and the Independent Innovation Foundation in Agricultural Science and Technology of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (Grant No. NGSB-2021-10-04).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Wang, J.; Robinson, B.H.; Zhao, X. Water-use patterns of Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum L.) on the Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 107010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Chen, X.; Jiang, T.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Insights into the improvement of bioactive phytochemicals, antioxidant activities and flavor profiles in Chinese wolfberry juice by select lactic acid bacteria. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, H.; Niu, Y.; Gao, B.; Yu, L. Partial least-squares-discriminant analysis differentiating Chinese wolfberries by UPLC–MS and Flow Injection Mass Spectrometric (FIMS) fingerprints. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9073–9080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xia, T.; Qiang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, M. Nutrition, bioactive components, and hepatoprotective activity of fruit vinegar produced from Ningxia wolfberry. Molecules 2022, 27, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wan, W.; Feng, S.; Xu, S.; Yang, J.; Duan, L. Biological activities of four components of essential oils against the wolfberry aphid (Aphis gossypii). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2019, 62, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Guo, R.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, Q.; Han, Y.; Liu, M.; Ma, X. Morphology and bionomics of Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Chinese wolfberry (Lycium barbarum). Acta Entomol. Sin. 2017, 60, 666–680. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Tie, M.; Chen, A.; Ma, K.; Li, F.; Liang, P.; Liu, Y.; Song, D.; Gao, X. Pyrethroid resistance associated with M918 L mutation and detoxifying metabolism in Aphis gossypii from Bt cotton growing regions of China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 2353–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Pan, Y.; Yang, C.; Gao, X.; Xi, J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, E.; Xin, X.; Zhan, C.; et al. Over-expression of CYP6A2 is associated with spirotetramat resistance and cross-resistance in the resistant strain of Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 126, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Guo, T.; Liang, P.; Zhen, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Establishment of toxicity and susceptibility baseline of broflanilide for Aphis gossypii Glove. Insects 2022, 13, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, C.; He, J.; Tian, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R. Resistance of wolfberry aphid in Ningxia. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 45, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xia, J.; Shang, Q.; Song, D.; Gao, X. UDP-glucosyltransferases potentially contribute to imidacloprid resistance in Aphis gossypii glover based on transcriptomic and proteomic analyses. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 159, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tang, C.; Ma, K.; Xia, J.; Song, D.; Gao, X. Overexpression of UDP-glycosyltransferase potentially involved in insecticide resistance in Aphis gossypii Glover collected from Bt cotton fields in China. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmorbida, I.; Coates, B.S.; Hodgson, E.W.; Ryan, M.; O’Neal, M.E. Evidence of enhanced reproductive performance and lack-of-fitness costs among soybean aphids, Aphis glycines, with varying levels of pyrethroid resistance. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 2000–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Du, Y.; Rinkevich, F.; Nomura, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, L.; Silver, K.; Zhorov, B.S. Molecular biology of insect sodium channels and pyrethroid resistance. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; You, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xian, W.; Song, Y.; Ge, Y.; Lu, X.; Ma, Z. Widespread resistance of the apple aphid Aphis spiraecola to pyrethroids in China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Wan, Q.; Pan, B. Transcription profiling and characterization of Dermanyssus gallinae cytochrome P450 genes involved in beta-cypermethrin resistance. Vet. Parasitol. 2020, 283, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xiang, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Yin, Y.; Cui, P.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Q. Monitoring and biochemical characterization of beta-cypermethrin resistance in Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Sichuan province, China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 146, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Pan, Y.; Bi, R.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Peng, T.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Hu, X.; Shang, Q. Elevated expression of esterase and cytochrome P450 are related with lambda–cyhalothrin resistance and lead to cross resistance in Aphis glycines Matsumura. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 118, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Nayak, B.; Xiong, L.; Xie, C.; Dong, Y.; You, M.; Yuchi, Z.; You, S. The role of insect cytochrome P450s in mediating insecticide resistance. Agriculture 2022, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Sun, X.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Characterization of carboxylesterase PxαE8 and its role in multi-insecticide resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhu, B.; Shan, J.; Li, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X. Functional analysis of a carboxylesterase gene involved in beta-cypermethrin and phoxim resistance in Plutella xylostella (L.). Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, J.; Shi, X.; Liang, P.; Gao, J.; Gao, X. Quantitative and qualitative changes of the carboxylesterase associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance in the housefly, Musca domestica (Diptera: Muscidae). Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2010, 156, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Tan, Y.; Han, H.; Guo, N.; Gao, H.; Xu, L.; Lin, K. Resistance to beta-cypermethrin, azadirachtin, and matrine, and biochemical characterization of field populations of Oedaleus asiaticus (Bey-Bienko) in Inner Mongolia, northern China. J. Insect Sci. 2022, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Wan, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Pan, B. Susceptibility of Dermanyssus gallinae from China to acaricides and functional analysis of glutathione S-transferases associated with beta-cypermethrin resistance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 171, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidi, N.; Vontas, J.; Van Leeuwen, T. The role of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in insecticide resistance in crop pests and disease vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 27, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Shi, C.; Zhu, X. Transcriptome-based identification and characterization of genes associated with resistance to beta-cypermethrin in Rhopalosiphum padi (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Agriculture 2023, 13, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletto, J.; Martin, T.; Vanlerberghe-Masutti, F.; Brévault, T. Insecticide resistance traits differ among and within host races in Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2010, 66, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.G. Life and death at the voltage-sensitive sodium channel: Evolution in response to insecticide use. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cominelli, F.; Chiesa, O.; Panini, M.; Massimino Cocuzza, G.E.; Mazzoni, E. Survey of target site mutations linked with insecticide resistance in Italian populations of Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4361–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, C.; Nauen, R. The molecular mechanisms of insecticide resistance in aphid crop pests. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 156, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gao, X.; Zheng, B. Cloning of partial sodium channel gene from strains of fenvalerate-resistant and susceptible cotton aphid (Aphis gossypii Glover). Agric. Sci. China 2003, 36, 1301–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Rinkevich, F.D.; Du, Y.; Dong, K. Diversity and convergence of sodium channel mutations involved in resistance to pyrethroids. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2013, 106, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Zhang, H.; Shan, T.; Shi, X.; Gao, X. The overexpression of three cytochrome P450 genes CYP6CY14, CYP6CY22 and CYP6UN1 contributed to metabolic resistance to dinotefuran in melon/cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 167, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Xia, X. The cross-resistance patterns and biochemical characteristics of an imidacloprid-resistant strain of the cotton aphid. J. Pestic. Sci. 2015, 40, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q.; Hu, X.; Pan, B.; Zeng, B.; Wu, N.; Fang, G.; Cao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Draft genome of the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 105, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Pan, Y.; Tian, F.; Xu, H.; Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Shang, Q. Identification and the potential roles of long non-coding RNAs in regulating acetyl-CoA carboxylase ACC transcription in spirotetramat-resistant Aphis gossypii. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 179, 104972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Dong, H. Detoxification enzymes associated with butene-fipronil resistance in Epacromius coerulipes. Pest Manag. Sci. 2020, 76, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Luo, J.; Zhu, X.; Wan, S. Characterization of P450 monooxygenase gene family in the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. J. Asia Pac. Entomol. 2022, 25, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W.; Ji, X.; Yang, Q.; Rui, C. Overexpression of ATP-binding cassette transporters associated with sulfoxaflor resistance in Aphis gossypii glover. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 4064–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiding, J. Status of resistance in houseflies, Musca domestica. In Working Paper in WHO Expert Committee on Resistance of Vectors and Reservoirs of Disease; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1980; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mollah, M.M.I.; Khatun, S. Exploring selected bioinsecticides for management of cotton aphids (Aphis gossypii Glover) of brinjal in Bangladesh. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Ullah, F.; Luo, C.; Monticelli, L.S.; Lavoir, A.-V.; Gao, X.; Song, D.; Desneux, N. Sublethal effects of beta-cypermethrin modulate interspecific interactions between specialist and generalist aphid species on soybean. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.M.I.; Rahman, M.M.; Miah, M.A.; Mala, M.; Hassan, M.Z. Efficacy of insecticides on the incidence and infestation of lablab bean aphid (Aphis craccivora Koch) under field conditions. J. Patuakhali Sci. Technol. Univ. 2013, 4, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhao, J.; Han, Z.; Chen, M. Comparative transcriptome and RNA interference reveal CYP6DC1 and CYP380C47 related to lambda-cyhalothrin resistance in Rhopalosiphum padi. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 183, 105088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Pan, Y.; Song, J.; Li, J.; Lv, Y.; Gao, X.; Tian, F.; Peng, T.; Xu, H.; Shang, Q. Resistance risk assessment of the ryanoid anthranilic diamide insecticide cyantraniliprole in Aphis gossypii Glover. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5849–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, H.; Dong, W.; Gu, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, A.; Shi, X.; Gao, X. Mutations in the nAChR β1 subunit and overexpression of P450 genes are associated with high resistance to thiamethoxam in melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Comp. Biochem. Phys. B 2022, 258, 110682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everaert, C.; Luypaert, M.; Maag, J.L.V.; Cheng, Q.X.; Dinger, M.E.; Hellemans, J.; Mestdagh, P. Benchmarking of RNA-sequencing analysis workflows using whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR expression data. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Love, M.; Davis, C.; Djebali, S.; Dobin, A.; Graveley, B.; Li, S.; Mason, C.; Olson, S.; Pervouchine, D.; et al. A benchmark for RNA-seq quantification pipelines. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munkhbayar, O.; Liu, N.; Li, M.; Qiu, X. First report of voltage-gated sodium channel M918V and molecular diagnostics of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor R81T in the cotton aphid. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 145, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.J.; Mellor, I.R.; Duce, I.R.; Davies, T.G.E.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S. Differential resistance of insect sodium channels with kdr mutations to deltamethrin, permethrin and DDT. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vais, H.; Atkinson, S.; Eldursi, N.; Devonshire, A.L.; Williamson, M.S.; Usherwood, P.N.R. A single amino acid change makes a rat neuronal sodium channel highly sensitive to pyrethroid insecticides. FEBS Lett. 2000, 470, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyeock Lee, S.; Smith, T.; C Knipple, D.; Soderlund, D. Mutations in the house fly Vssc1 sodium channel gene associated with super-kdr resistance abolish the pyrethroid sensitivity of Vssc1/tipE sodium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1999, 29, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.