Research on Water and Fertilizer Diagnosis of Maize Using Visible–Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

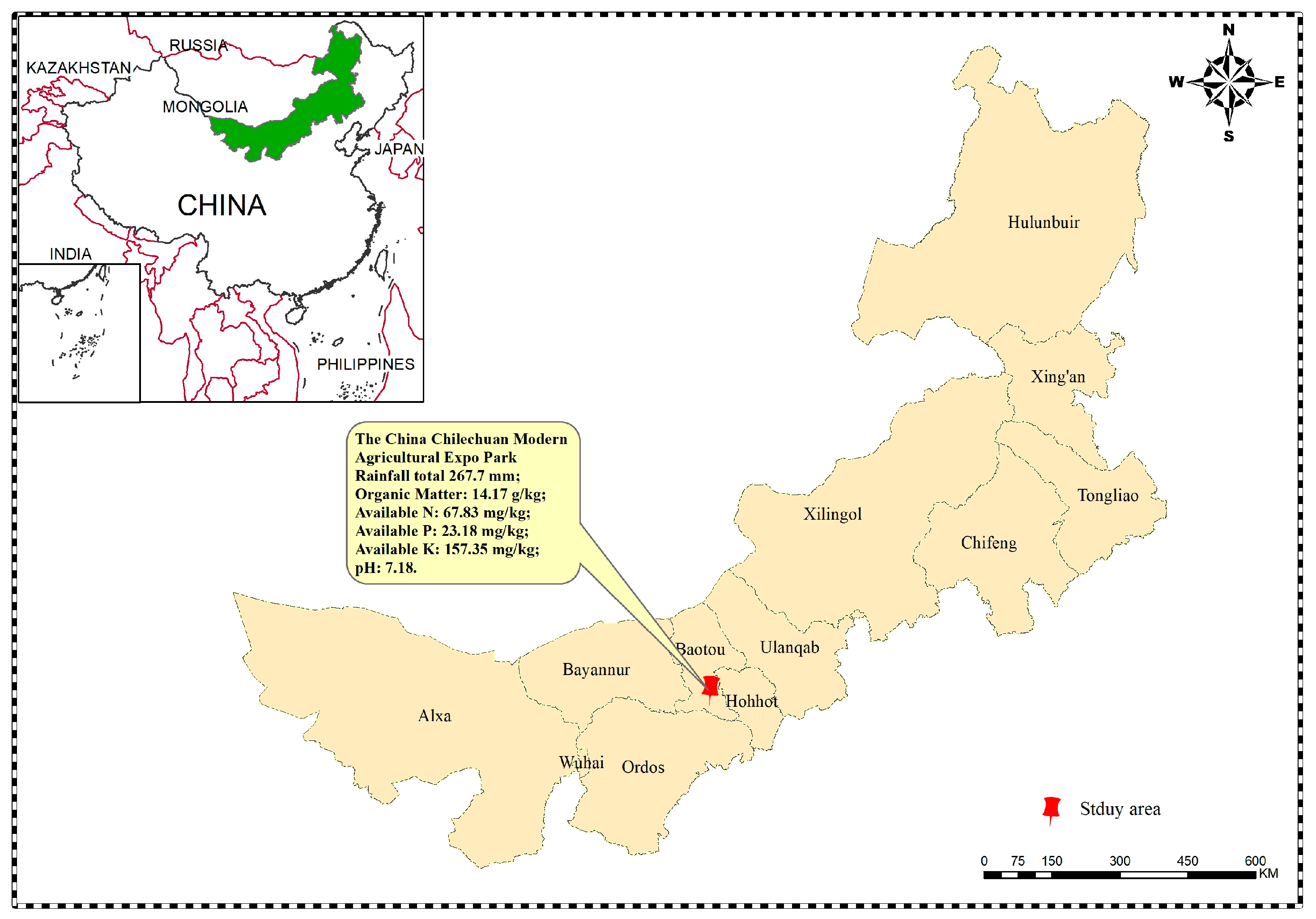

2.1. Experimental Site Overview

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurement Indicators and Methods

2.3.1. Measurement Indicators

2.3.2. Hyperspectral Data Acquisition

2.3.3. Spectral Preprocessing

2.3.4. Spectral Index Extraction

2.3.5. Model Construction and Validation

2.3.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Spectral Characteristics Analysis of Maize Leaves

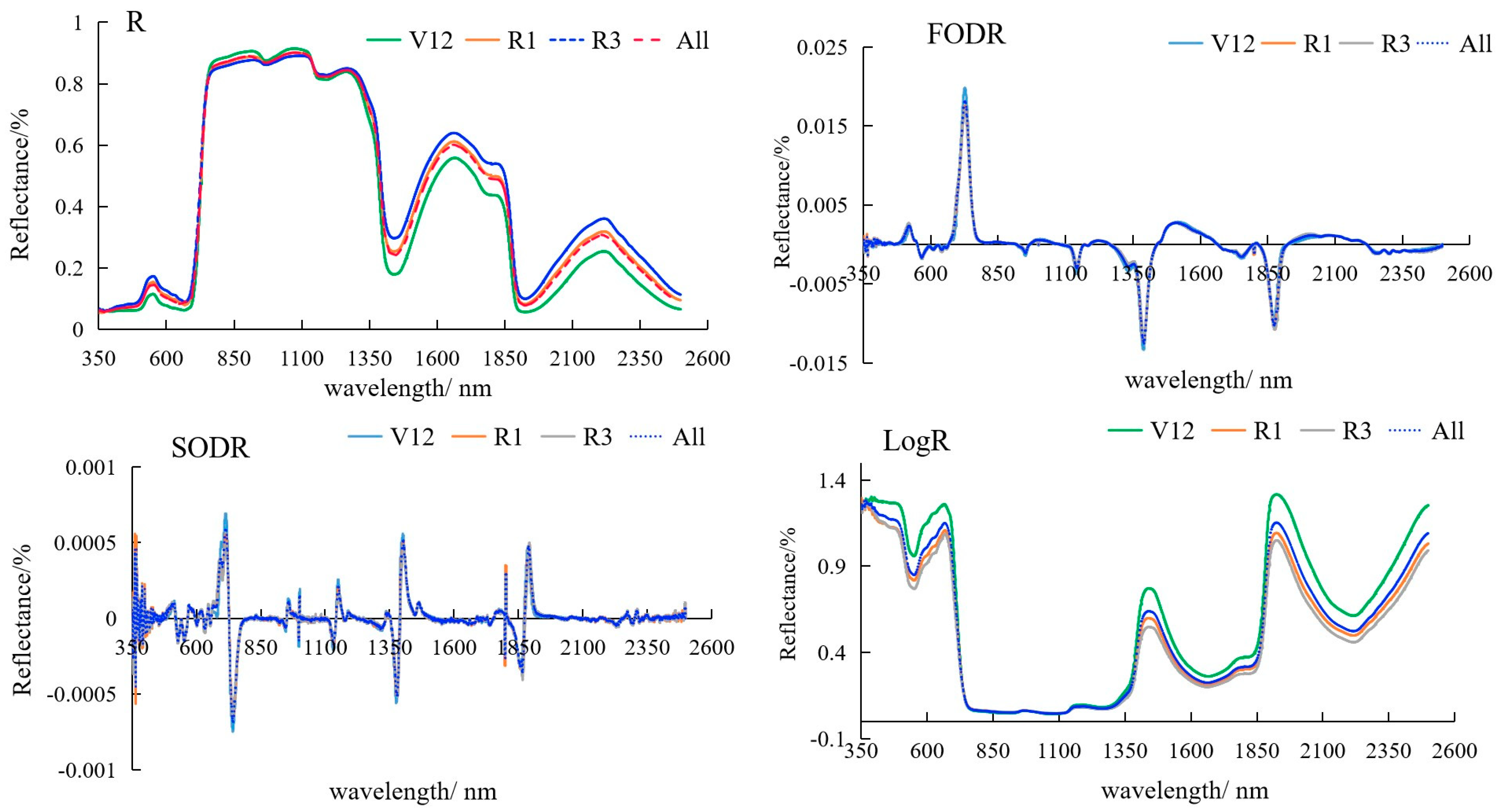

3.1.1. Spectral Characteristics of Maize Leaves at the Different Spectral Transformations

3.1.2. Spectral Characteristics of Maize Leaves Under Water–Nitrogen Coupling Conditions

3.1.3. Spectral Characteristics of SPAD Value in Different Spectral Transformations

3.1.4. Spectral Characteristics of Maize Leaves at Different Moisture Contents

3.1.5. Spectral Characteristics of Maize Leaves with Varying Nitrogen Content

3.2. Variation Patterns in Phenotypic Parameters of Maize Leaf Agronomic Traits

3.3. Screening Optimal Spectral Indices

3.3.1. Correlation Analysis Between Spectral Indices and SPAD Values of Maize Leaves

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis Between LWC and Spectral Index

3.3.3. Correlation Analysis of LNC and Spectral Indices

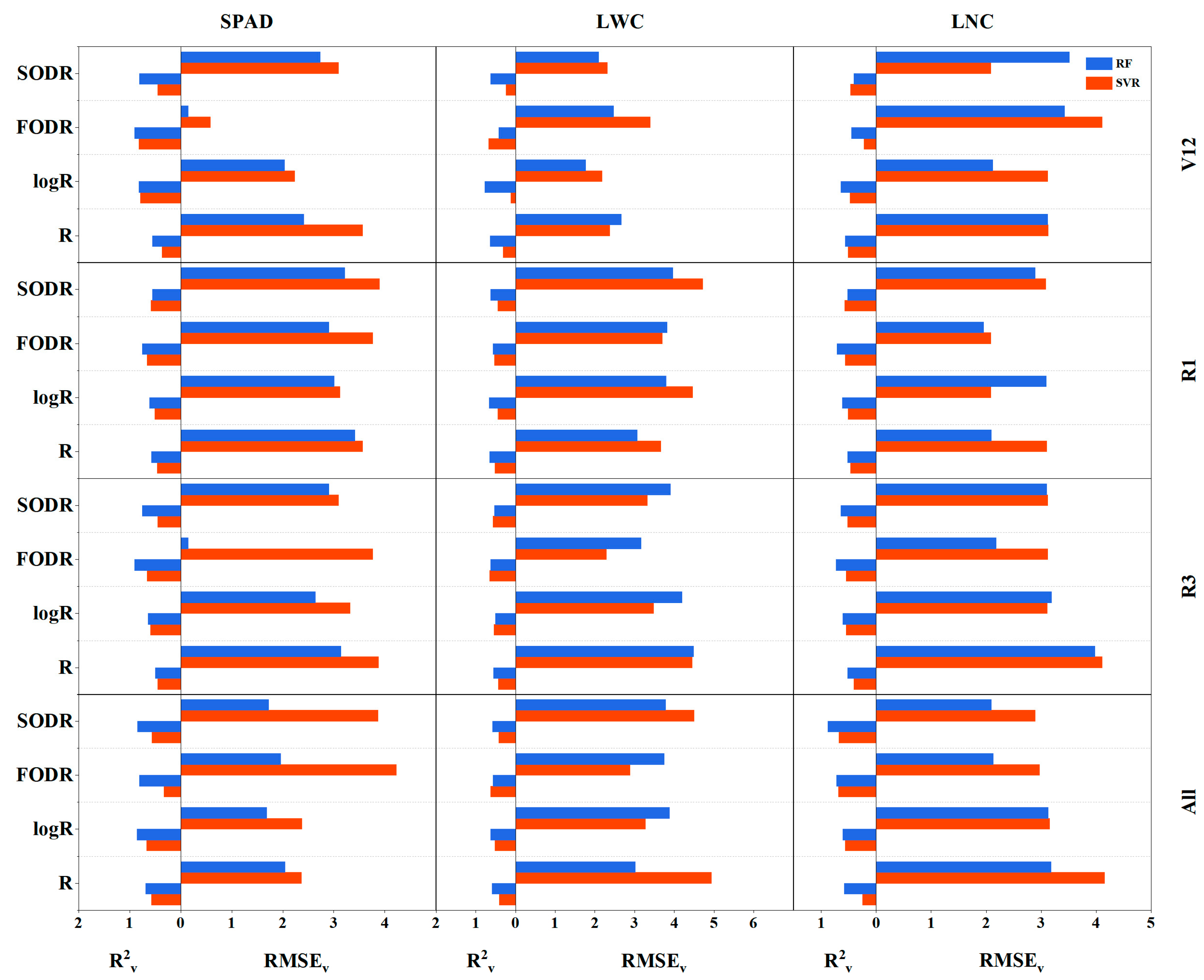

3.4. Development of Hyperspectral Estimation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Water–Nitrogen Coupling Reduction on Agronomic Trait Parameters of Maize Leaves

4.2. The Impact of Spectral Processing on Machine Learning Model Estimation of Corn Leaf Agronomic Parameters

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Bureau of Statistics Announcement on 2023 Grain Production Data. China Information Daily. 12 December 2023.

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, J.; Dong, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xue, J.; Wang, L.; et al. Progress and Prospects in Maize Cultivation Research in China. Chin. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 50, 1941–1959. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, N. Monitoring Maize Growth Using UAV-Based Visible Spectral Remote Sensing. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2021, 41, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xue, Z.C.; Wang, X.R.; Dai, H.L. Monitoring the Effect of Cadmium on the Photosynthetic Apparatus of Ulmus pumila Leaves by Spectral Reflection Technology. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2024, 52, 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, H.; Fan, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Jin, C.; Chen, Y.; Pan, H. Comprehensive Evaluation of Tomato Growth Status under Aerated Drip Irrigation Based on Critical Nitrogen Concentration and Nitrogen Nutrient Diagnosis. Plants 2024, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, F.; Liu, A.; Wang, X. The prediction model of nitrogen nutrition in cotton canopy leaves based on hyperspectral visible-near infrared band feature fusion. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 18, e2200623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldwairi, M.; Gafoor, F.A.; Alcibahy, M.; Alsaleh, A.R.; AlMahdouri, A.; Alyounis, S.; AlMomani, D.E.; Zhang, T.; AlShehhi, M.R. Hyperspectral spectroscopy and machine learning for non-destructive monitoring of leaf water and chlorophyll content under greenhouse lighting conditions. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 40, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, M.R.; Zhang, S.H.; Guan, H.-W.; Wang, C.-Y.; Feng, W.; Guo, T.-C. Remote estimation of leaf water concentration in winter wheat under different nitrogen treatments and plant growth stages. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 986–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W.; Li, D.; Kou, W.; Lu, N.; Wu, F.; Sun, S.; Liu, Z. A Multi-Feature Estimation Model for Olive Canopy Chlorophyll Combining XGBoost with UAV Imagery. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Tao, W.; Lin, S.; Su, L.; Deng, M.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhu, T.; Ma, L. The Synergistic Production Effect of Water and Nitrogen on Winter Wheat in Southern Xinjiang. Plants 2024, 13, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, X.D. Estimating insect pest density using the physiological index of crop leaf. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1152698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, H.; Xiao, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Different Nitrogen Application Rates and Planting Densities on Chlorophyll Fluorescence Properties in Maize. Mol. Plant Breed. 2024, 22, 6411–6419. [Google Scholar]

- Boisseaux, M.; Nemetschek, D.; Baraloto, C.; Burban, B.; Casado-Garcia, A.; Cazal, J.; Clément, J.; Derroire, G.; Fortunel, C.; Goret, J.; et al. Shifting trait coordination along a soil-moisture-nutrient gradient in tropical forests. Funct. Ecol. 2025, 39, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Feng, H.; Qin, F.; Zhang, G.; Ding, H. Effects of nitrogen allocation and photosynthetic proteins response in peanut leaves on photosynthesis under conditions of water scarcity and nitrogen deficiency. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Gao, Z.W.; Wang, Z.J. Prediction of Leaf Nitrogen Content of Rice in Cold Region Based on Spectral Reflectance. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2024, 44, 2582–2593. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. Third ERTS Symp. 1974, 1, 309–317. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, A.J.; Wiegand, C.L. Distinguishing vegetation from soil background information. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1977, 43, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of Leaf-Area Index from Quality of Light on the Forest Floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A soil-adjusted vegetation index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppelt, N.; Mauser, W. Hyperspectral monitoring of physiological parameters of wheat during a vegetation period using AVIS data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuelas, J.; Amaro, T.; Araus, J.L.; Filella, I. Relationship between photosynthetic radiation-use efficiency of barley canopies and the photochemical reflectance index (PRI). Physiol. Plant. 2010, 96, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, G.A. Spectral indices for estimating photosynthetic pigment concentrations: A test using senescent tree leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1998, 19, 657–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Gritz, Y.; Merzlyak, M.N. Relationships between leaf chlorophyll content and spectral reflectance and algorithms for non-destructive chlorophyll assessment in higher plant leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelmann, J.E.; Rock, B.N.; Moss, D.M. Red edge spectral measurements from sugar maple leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1993, 14, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, B. A New Reflectance Index for Remote Sensing of Chlorophyll Content in Higher Plants: Tests using Eucalyptus Leaves. J. Plant Physiol. 1999, 154, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Griffin, K.L.; Field, C.B. Assessing community type, plant biomass, pigment composition, and photosynthetic efficiency of aquatic vegetation from spectral reflectance. Remote Sens. Environ. 1993, 46, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. Interdiscip. J. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.M.; Huang, J.F.; Tang, Y.L.; Wang, X.Z. New Vegetation Index and Its Application in Estimating Leaf Area Index of Rice. Rice Sci. Engl. Ed. 2007, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboudane, D.; Miller, J.R.; Pattey, E.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Strachan, I.B. Hyperspectral vegetation indices and novel algorithms for predicting green LAI of crop canopies: Modeling and validation in the context of precision agriculture. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.D.; Balaguer, L.; Manrique, E.; Elvira, S.; Davison, A.W. A reappraisal of the use of DMSO for the extraction and determination of chlorophylls a and b in lichens and higher plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 1992, 32, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, L.; Leuven, R.S.E.W.; Wehrens, R.; Nienhuis, P.H.; Buydens, L.M.C. A comparison of methods to relate grass reflectance to soil metal contamination. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 4995–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Quantitative estimation of chlorophyll-a using reflectance spectra: Experiments with autumn chestnut and maple leaves. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 1994, 22, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L.; Ustin, L.S.; Roberts, A.D.; Gamon, J.A.; Penuelas, J. Deriving Water Content of Chaparral Vegetation from AVIRIS Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2000, 74, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.E.; Ustin, L.S.; Riaño, D. Estimating canopy water content from spectroscopy. Isr. J. Plant Sci. 2012, 60, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.-C. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for remote sensing of vegetation liquid water from space. Remote Sens. Environ. Imaging 1995, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuelas, J.; Gamon, J.A.; Fredeen, A.L.; Merino, J.; Field, C. Reflectance indices associated with physiological changes in nitrogen- and water-limited sunflower leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 48, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.A.; Duigan, P.S.; Berlyn, P.G. An Evaluation of Noninvasive Methods to Estimate Foliar Chlorophyll Content. New Phytol. 2002, 153, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, P.; Gobron, N.; Flasse, S.; Pinty, B.; Tarantola, S. Designing a spectral index to estimate vegetation water content from remote sensing data: Part 1: Theoretical approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 82, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Pedregosa, F.; Eickenberg, M.; Gervais, P.; Mueller, A.; Kossaifi, J.; Gramfort, A.; Thirion, B.; Varoquaux, G. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquax, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualotto, N.; Delegido, J.; Van Wittenberghe, S.; Verrelst, J.; Rivera, J.P.; Moreno, J. Retrieval of canopy water content of different crop types with two new hyperspectral indices: Water Absorption Area Index and Depth Water Index. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2018, 67, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, P.R.; Silva, C.A.A.C.; Rizzo, R.; Demattê, J.A.M.; Luciano, A.C.D.S.; Silva, M.A.D. Prediction of leaf nitrogen in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) by Vis-NIR-SWIR spectroradiometry. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, L.B.; Dugina, K.; Saeidan, A.; Yoshicawa, G.V.; Caporaso, N.; Gapare, B.; Umer, M.J.; Bhosale, R.A.; Searle, I.R.; Foulkes, M.J.; et al. Reviving grain quality in wheat through non-destructive phenotyping techniques like hyperspectral imaging. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ali, A.M. Using Hand-Held Chlorophyll Meters and Canopy Reflectance Sensors for Fertilizer Nitrogen Management in Cereals in Small Farms in Developing Countries. Sensors 2020, 20, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Singh, S.; Khan, M.S.; Semwal, M. Non-invasive Estimation of Foliar Nitrogen Concentration Using Spectral Characteristics of Menthol Mint (Mentha arvensis L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 680282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlin, J.L.; Tisdale, S.L.; Nelson, W.L.; Beaton, J.D. Soil Fertility and Fertilizers; Pearson Education India: Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Remote estimation of chlorophyll content in higher plant leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 18, 2691–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, E.; Rinaldi, M. Yield response of corn to irrigation and nitrogen fertilization in a Mediterranean environment. Field Crops Res. 2008, 105, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Below, F.E. Nitrogen metabolism and crop productivity. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 2, pp. 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulridha, J.; Min, A.; Rouse, M.N.; Kianian, S.; Isler, V.; Yang, C. Evaluation of Stem Rust Disease in Wheat Fields by Drone Hyperspectral Imaging. Sensors 2023, 23, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.S.; Angel, Y.; Houborg, R.; Ali, S.; McCabe, M.F. A Random Forest Machine Learning Approach for the Retrieval of Leaf Chlorophyll Content in Wheat. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.L.; Ge, X.Y.; Ding, J.L.; Wang, J.Z.; Zhang, Z.H. Estimation of soil moisture content by coupling machine learning with airborne hyperspectral data. Adv. Lasers Optoelectron. 2020, 57, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Song, J. Inversion of Vegetation Leaf Water Content Using Spectral Indices. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2018, 38, 1540–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osco, L.P.; Junior, J.M.; Ramos, A.P.M.; Furuya, D.E.G.; Santana, D.C.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Gonçalves, W.N.; Baio, F.H.R.; Pistori, H.; Junior, C.A.d.S.; et al. Leaf Nitrogen Concentration and Plant Height Prediction for Maize Using UAV-Based Multispectral Imagery and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organic Matter (g/kg) | Available N (mg/kg) | Available P (mg/kg) | Available K (mg/kg) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.17 | 67.83 | 23.18 | 157.35 | 7.18 |

| Vegetation Index | Calculation Formula | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI | (Rλ1 − R670)/(Rλ1 + R670) | Rouse [16] |

| GNDVI | (Rλ1 − R550)/(Rλ1+ R550) | Gitelson et al. [17] |

| DVI | Rλ1 − R670 | Richardson and Wiegand [18] |

| RVI | Rλ1/R720 | Jordan [19] |

| SAVI | 1.5 × (Rλ1 − R670)/(Rλ1 + R670 + 0.5) | Huete [20] |

| HNDVI | (Rλ1 − R668)/(Rλ1 + R668) | Oppelt and Mauser [21] |

| PRI | (Rλ1 − R531)/(Rλ1 + R531) | Penuelas et al. [22] |

| SIPI | (Rλ1 − R450)/(Rλ1 +R450) | Penuelas et al. [22] |

| PSNDa | Rλ1 − R680)/(Rλ1 + R680) | Blackburn [23] |

| PSNDb | (Rλ1 − R635)/(Rλ1 + R635) | Blackburn [23] |

| PSSRa | Rλ1/R680 | Blackburn [23] |

| PSSRb | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Blackburn [23] |

| CIred_edge | Rλ1/Rλ2-1 | Gitelson et al. [24] |

| SR | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Jordan [19] |

| VOG1 | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Vogelmann et al. [25] |

| MRESR | (Rλ1 − R445)/(Rλ1 + R445) | Datt [26] |

| NPCI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Penuelas et al. [27] |

| GRVI | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Gitelson et al. [28] |

| RNDVI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/sqrt(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Wang et al. [29] |

| MSR | (Rλ1/Rλ2 − 1)/(sqrt(Rλ1/Rλ2) + 1) | Haboudane et al. [30] |

| NPQI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Barnes et al. [31] |

| IPVI | Rλ1/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Kooistra et al. [32] |

| RENDVI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Gitelson and Merzlyak [33] |

| NDNI | (log(1/Rλ1) − log(1/Rλ2))/(log(1/Rλ1) + log(1/Rλ2)) | Serrano et al. [34] |

| MSI | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Hunt et al. [35] |

| NDII | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 +Rλ2) | Serrano et al. [34] |

| NDWI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2li)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Gao [36] |

| WBI | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Penuelas et al. [37] |

| mSR | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Sims and Gamom [38] |

| PPR | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1 + Rλ2) | Kooistra et al. [32] |

| NDSI | (Rλ1 − Rλ2)/(Rλ1+ Rλ2) | Richardson et al. [39] |

| WI | Rλ1/Rλ2 | Penuelas et al. [37] |

| GVWI | [(Rλ1 + 0.1) − (Rλ2 + 0.02)]/[(Rλ1 + 0.1) + (Rλ2 + 0.02)] | Ceccato et al. [40] |

| Agronomic Trait Parameters | Source of Variation | V12 | R1 | R3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAD | ||||

| Nitrogen application rate(N) | 9.48 ** | 17.96 ** | 38.27 ** | |

| Main zone error | 1.99 | 5.47 | 1.71 | |

| Irrigation amount(W) | 18.32 ** | 17.59 ** | 8.86 ** | |

| Secondary zone error | 3.53 | 7.92 | 5.38 | |

| Nitrogen application rate × Irrigation amount (N × W) | 1.01 ns | 0.49 ns | 0.2 ns | |

| LWC | ||||

| Nitrogen application rate(N) | 47.12 ** | 5.8 ** | 18.11 ** | |

| Main zone error | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Irrigation amount(W) | 2.62 ns | 24.97 ** | 181.59 ** | |

| Nitrogen application rate × Irrigation amount (N × W) | 6.63 ** | 1.04 ns | 9.66 ** | |

| Secondary zone error | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| LNC | ||||

| Nitrogen application rate(N) | 282.17 ** | 45.92 ** | 50.20 ** | |

| Main zone error | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Irrigation amount(W) | 79.75 ** | 153.57 ** | 177.55 ** | |

| Nitrogen application rate × Irrigation amount (N × W) | 15.83 ** | 17.12 ** | 7.54 ** | |

| Secondary zone error | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| R | logR | FODR | SODR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V12 | NDSI | PRI, NPQI, mSR | GNDVI, PSNDb, GRVI, NPQI | PSNDa, PSSRa, NDII, NDWI, GVWI |

| R1 | SAVI, PRI, PSNDa, SR, NDSI | SAVI, PRI, SR, VOG1, RNDVI, NPQI, RENDVI, mSR | MSI, NDII, WBI, WI | MRESR, NDII, WBI, NDSI, WI |

| R3 | GNDVI, RVI, PSSRb, VOG1, MRESR, GRVI, NPQI, RENDVI, NDNI, MSI, NDWI, mSR | NPQI, NDNI, PPR | NDVI, DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, RNDVI, IPVI, NDSI | DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, SR, NPCI |

| All | NPCI, NDSI | SR, MRESR, NPCI, mSR | DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, RNDVI | DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, SR, NPCI |

| R | logR | FODR | SODR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V12 | NDVI, RVI, HNDVI, PRI, SIPI, PSNDa, PSNDb, PSSRa, SR, MSR, IPVI, PPR | DVI, PRI, VARIgreen, MRESR, NDNI, mSR, PPR | GNDVI, PSSRb, GRVI, NDSI | HNDVI, VOG1, NDSI, GVWI |

| R1 | NDVI, RVI, HNDVI, PRI, PSNDa, PSSRb, SR MSR, IPVI | DVI, PRI, VARIgreen | MSI, NDII, NDWI, PPR | NDSI, GVWI, RENDVI, PSNDa, |

| R3 | MSI, NDII, NDWI, WBI, WI, GVWI | NDNI, MSI, NDII, NDWI, WBI, WI, GVWI | GNDVI, GRVI, NDII, WBI, WI, GVWI | NDSI, RENDVI, PRI |

| All | NPCI, RENDVI, WBI, PPR, NDSI, WI, GVWI | MRESR, NPCI, Msr, PPR | DVI, SAVI, PSNDa, VARgreen, NPCI, NDSI | NDSI, SR, VARIgreen, HNDVI, SAVI, DVI |

| R | logR | FODR | SODR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V12 | NDSI, NPQI, NPCI | PRI, NPCI, NPQI | RVI, PSNDa, PSSRa, NDSI, | GVWI, PPR, HNDVI |

| R1 | NDNI, IPVI, MSR, SR, PSSRb, PSSRa, PSNDb, PSNDa, SIPI, HNDVI, SAVI, RVI, NDVI | DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, RNDVI | GRVI, NDII, WI, GVWI | GVWI, WI, NDSI, PPR, WBI, HNDVI |

| R3 | PPR, mSR, RENDVI, NPQI, GRVI, MRESR, VOG1, PSSRb, PRI, GNDVI | MRESR, NPQI, mSR, PPR | DVI, SAVI, VARIgreen, VOG1, MRESR, RNDVI, RENDVI, mSR | GVWI, RENDVI, NPCI, SR |

| All | WI, WBI, NDWI, NDII, MSI, NPCI | MRESR, NPCI, NDNI, mSR, PPR, GVWI | DVI, SAVI, PSNDa, PSSRa, PSSRb, VARIgreen, NPCI | GVWI, PPR, NPCI, SR, SIPI |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ta, N.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Gao, J.; Ma, D.; Chen, J.; Dou, X. Research on Water and Fertilizer Diagnosis of Maize Using Visible–Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Technology. Agriculture 2026, 16, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010084

Ta N, Li Y, Yu X, Gao J, Ma D, Chen J, Dou X. Research on Water and Fertilizer Diagnosis of Maize Using Visible–Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Technology. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010084

Chicago/Turabian StyleTa, Na, Yanliang Li, Xiaofang Yu, Julin Gao, Daling Ma, Jian Chen, and Xu Dou. 2026. "Research on Water and Fertilizer Diagnosis of Maize Using Visible–Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Technology" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010084

APA StyleTa, N., Li, Y., Yu, X., Gao, J., Ma, D., Chen, J., & Dou, X. (2026). Research on Water and Fertilizer Diagnosis of Maize Using Visible–Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Technology. Agriculture, 16(1), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010084