Abstract

High temperature stress severely compromises plant growth and productivity by triggering chlorophyll loss. Plant protochlorophyllide-dependent translocon component of 52 kDa (PTC52) has been proven to be involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis, yet its functional role in plant high-temperature stress response remains uncharacterized. In our study, PlPTC52 was isolated and characterized from herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), an economically important ornamental species susceptible to high temperature stress. The PlPTC52 gene comprised a 1647 bp coding sequence that translates into a 548-amino-acid protein. Subcellular localization confirmed its chloroplast localization, consistent with its putative role in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Functional analyses showed that silencing of PlPTC52 in P. lactiflora accelerated chlorophyll loss, increased reactive oxygen species accumulation, and impaired photosystem II efficiency and membrane integrity under high temperature stress. Conversely, overexpression of PlPTC52 in Nicotiana tabacum decelerated chlorophyll loss, decreased reactive oxygen species accumulation, and improved photosystem II efficiency and membrane integrity under high temperature stress. Collectively, this study provides the first functional evidence implicating PTC52 in plant responses to high temperature stress and identifies PlPTC52 as a potential genetic resource for enhancing thermotolerance in horticultural crops.

1. Introduction

Global climate change intensifies high temperature stress, a major abiotic stressor that impairs plant growth and development, resulting in diminished crop yields and ornamental quality. Prolonged high temperature stress during the grain-filling phase of wheat hastened the reduction in starch synthase activity in the grains, thereby impeding nutrient accumulation and resulting in yield losses [1]. In rice, exposure to high temperatures during the flowering and grain-setting stages impaired pollen viability, significantly reducing the fertilization rate and increasing the percentage of unfilled grains [2,3]. Similarly, in chrysanthemums, extreme high temperature stress during reproductive development induced premature flower wilting and floral color fading, severely diminishing their ornamental value [4,5]. Herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), a renowned ornamental and medicinal plant belonging to the Paeoniaceae family, is widely cultivated in temperate regions worldwide for its large, vibrant flowers and high horticultural value [6]. However, similar to many other plants, P. lactiflora is highly susceptible to summer high temperature stress associated with global warming, which severely affects its growth and development, often resulting in premature leaf senescence, chlorophyll degradation, and compromised cut-flower quality in the subsequent year [7]. As a result, high temperature stress has become a critical factor limiting the production and utilization of P. lactiflora.

Studies have indicated that high temperature stress disrupts normal physiological processes in plants by impairing photosynthesis, promoting reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and causing membrane damage. These detrimental effects occur in a coordinated manner and collectively influence plant growth through multiple mechanistic pathways [8,9]. Among these effects, photosynthetic impairment directly restricts organic matter accumulation, contributing to growth retardation and premature leaf senescence, which ultimately exacerbate yield reduction [10,11,12]. Chlorophyll, the central pigment in plant photosynthesis, plays a fundamental role in light absorption, energy transfer, and photochemical conversion. However, high temperatures impair chlorophyll structure and function through various mechanisms: on the one hand, they disrupt the structural integrity of thylakoid membranes, impairing the binding sites for chlorophyll a and b within photosynthetic complexes and hindering their capacity for efficient light absorption and energy transfer [13]. On the other hand, they suppress the activities of key enzymes involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis while enhancing chlorophyll-degrading enzyme activities, accelerating pigment breakdown, and resulting in pronounced leaf chlorophyll loss, which is visually manifested as leaf chlorosis [14,15,16]. Overall, high temperature stress reduces agricultural productivity by disturbing chlorophyll metabolic balance and impairing essential physiological processes. Thus, elucidating chlorophyll protection mechanisms under high temperature stress provides a fundamental theoretical framework for formulating strategic approaches to enhance plant thermotolerance.

To mitigate high temperature stress, plants deploy regulated protective mechanisms that maintain chlorophyll metabolic balance. Specifically, they induce a coordinated antioxidant response, in which increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) activities counteract reactive oxygen species (ROS) overaccumulation. This enzymatic ROS scavenging protects chlorophyll and thylakoid membranes from oxidative damage, thereby preserving photosynthetic efficiency under stress conditions [17,18]. In addition, plants accumulate compatible solutes, such as proline and betaine, which function as osmotic protectants. These compounds can enter chloroplasts to stabilize thylakoid membrane structures, maintain an optimal binding environment for chlorophyll a and b, and indirectly support chlorophyll function under high temperature stress [19,20]. Furthermore, plants regulate the activity of enzymes related to chlorophyll biosynthesis to sustain the pathway’s continuous operation, partially offsetting the inhibitory effects of high temperatures. For example, the wheat stress-responsive protein 2-cysteine peroxiredoxin (Ta2CP) enhanced chlorophyll biosynthesis by interacting with protochlorophyllide reductase b (TaPORB) to promote the conversion of protochlorophyllide to chlorophyll, thereby contributing to improved high temperature tolerance [21]. These intrinsic protective strategies not only enable plants to adapt to prolonged high temperatures but also provide natural targets for the artificial regulation of chlorophyll metabolism. Ongoing identification and functional characterization of novel regulatory genes further enhance our insight into the molecular pathways underlying high temperature adaptation and offer key genetic resources for developing efficient thermotolerance technologies for crops.

The higher plant genome encodes a distinct five-member family of non-heme oxygenases characterized by conserved Rieske-type [2Fe-2S] and mononuclear iron-binding domains. This functionally diverse family includes chlorophyllide a oxygenase (CAO), choline monooxygenase (CMO), the plastid inner envelope protein TIC55, pheophorbide a oxygenase (PAO), and the chloroplastic 52 kDa protein (PTC52), which collectively participate in protein transport and chlorophyll metabolism. Among these, PTC52 is a key enzyme localized to the inner chloroplast membrane. It specifically catalyzes the conversion of protochlorophyllide a to protochlorophyllide b and couples this reaction with the transmembrane transport of the chloroplast precursor protein pPORA, thereby playing a dual functional role in chlorophyll biosynthesis [22,23,24]. Additionally, the C-terminal region of PTC52 contains a conserved CxxC motif that can be reduced by thioredoxin (Trx f/m), allowing the protein to respond to changes in the chloroplast redox state and participate in light-dark regulation or oxidative stress responses [25]. In summary, PTC52 is a multifunctional protein critical for chloroplast function. However, its precise roles under high temperature stress, such as its effect on chlorophyll content and potential involvement in plant heat-response pathways, remain unclear, making PTC52 a promising candidate for investigating chlorophyll protection mechanisms under heat stress.

Therefore, in this study, we employed the P. lactiflora cultivar ‘Da Fugui’ to investigate the function of the PlPTC52 gene under high temperature stress. We cloned its full-length coding sequence (CDS), analyzed its evolutionary relationships, and combined subcellular localization, gene silencing, and overexpression approaches to systematically examine its role in regulating chlorophyll metabolism and high temperature tolerance. This work provides molecular insights into the high temperature adaptation mechanisms of P. lactiflora and identifies a novel genetic target for stress-resistance breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and High Temperature Treatment

This study was performed in a greenhouse at Yangzhou University. Uniform P. lactiflora plants with 3-5 buds were selected and cultivated in pots containing a sterilized 1:1:1 (v/v/v) mixture of soil, vermiculite, and perlite. For high temperature stress, plants were placed in a growth chamber maintained at 42 °C during the day and 37 °C at night, under conditions of 60–70% relative humidity, a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod, and a light intensity of 30,000 lux. Leaf tissues were sampled at 0, 12, 24, 48, 96, and 192 h after the initiation of stress for subsequent analysis of PlPTC52 expression.

2.2. Cloning and Characterization of PlPTC52

Total RNA from P. lactiflora leaves was purified, followed by first-strand cDNA synthesis with the EasyScript RT/RI Enzyme Mix (TransGen, Beijing, China). The CDS of PlPTC52 was then amplified by PCR with gene-specific primers designed from the P. lactiflora transcriptome (NCBI SRA: PRJNA1059272; Supplementary Table S1). Following purification, the PCR fragment was ligated into the cloning vector (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), introduced into Escherichia coli for propagation, and sequence-verified by Sangon (Shanghai, China). The CDS of PlPTC52 has been deposited in the GenBank database with the accession number PX694234. Homologous sequences from other species were identified using the deduced PlPTC52 amino acid sequence through BLASTP program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 4 November 2025). searches in the NCBI database, including sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana. Sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW in MEGA 7.0 [26], followed by construction of a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree.

2.3. Real-Time Quantitative PCR for PlPTC52 Transcript Levels

Total RNA was isolated from leaf samples as described above and subsequently reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA following the instructions provided by the reagent manufacturer (TransGen, Beijing, China). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was conducted using a real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) with a SYBR Green-based chemistry (TransGen, Beijing, China) and gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). Transcript levels were normalized to the P. lactiflora Actin gene (PlActin, GenBank accession number JN105299), and relative expression was determined using the 2–ΔΔCt method [27].

2.4. Subcellular Localization

To generate the 35S::PlPTC52-eGFP fusion construct for subcellular distribution examination, the PlPTC52 CDS (stop codon omitted) was inserted into the pCAMBIA2300-eGFP vector under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter (see Supplementary Table S1 for primers). The construct and the empty vector (control) were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101, and the bacteria were infiltrated into the leaves of 40-day-old Nicotiana benthamiana. After 48 h, fluorescence signals were visualized with a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope. GFP signals were visualized using a 488 nm excitation wavelength with emission collected between 494 and 563 nm, whereas chloroplast autofluorescence was recorded under 633 nm excitation with an emission range of 637–758 nm.

2.5. Gene Silencing in P. lactiflora

To silence PlPTC52, we generated TRV-based vectors by cloning target-specific fragments (Supplementary Table S1) into pTRV2. A. tumefaciens GV3101 harboring pTRV1 was mixed 1:1 with strains containing either empty pTRV2 or pTRV2-PlPTC52 fragments (OD600 = 0.8), followed by coinfiltration into P. lactiflora root systems according to our established protocol [28]. After 3–4 weeks of culture, plants were collected for PCR and qPCR identification, with all primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Afterward, PlPTC52-silenced plants were exposed to high temperature stress in a controlled growth chamber for 12 days according to the method mentioned earlier. Subsequently, plant phenotypes were documented, and a series of physiological parameters were assessed.

2.6. Gene Overexpressing in Nicotiana tabacum

The CDS of PlPTC52 was cloned into the pCAMBIA1301 vector. Detailed information regarding the cloning strategy and primer sequences is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Transgenic N. tabacum ‘K326’ plants were subsequently produced via the leaf disk transformation method [29]. Then, the transformed plants were collected for PCR and qPCR identification, with all primers detailed in Supplementary Table S1. Following 1–2 months of culture, the resultant plants were subjected to high temperature stress. The treatment method and the indices measured were identical to those used for the P. lactiflora plants.

2.7. Physiological Indices Measurement

The maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) was measured with a PlantView 230F chlorophyll fluorometer (BLT, Guangzhou, China) after 30 min of dark adaptation. Relative electrical conductivity (REC) was determined using a DDS-307A conductivity meter (Leici, Shanghai, China). Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was quantified with commercial assay kits (Komin, Suzhou, China). Accumulation of superoxide anions (O2·−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was assessed using nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining, respectively. For both staining assays, each biological replicate included at least three leaves. After staining, representative leaves that could objectively reflect the ROS accumulation status of the corresponding group were selected for imaging. Chlorophyll a and b were extracted with 95% ethanol, and their concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the absorbance values at 665 nm and 649 nm [30].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD from a minimum of three independent biological replicates. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test (p < 0.05) in SPSS Statistics 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Graphical representations were prepared with GraphPad Prism 8 software [31].

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Sequence Analysis of PlPTC52

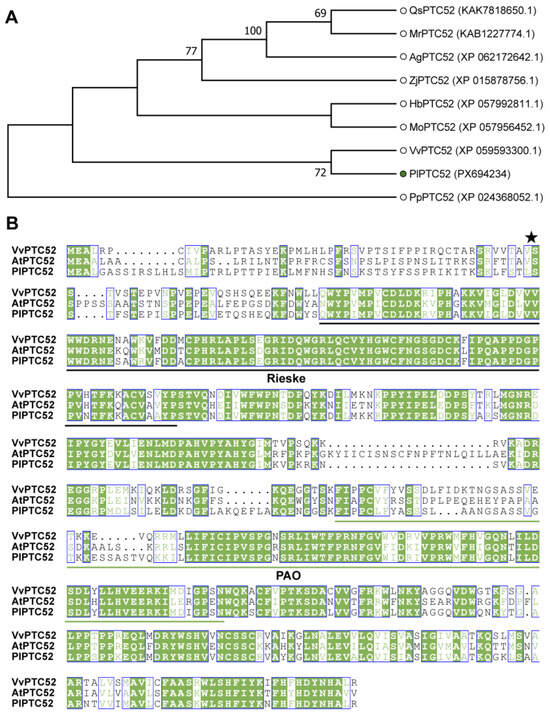

To explore how PlPTC52 contributes to high temperature resistance in P. lactiflora, we first cloned its coding sequence using transcriptomic data obtained from high-temperature-stressed P. lactiflora. The cloned CDS was 1647 bp in length, encoding a protein of 548 amino acids. Subsequently, we performed an evolutionary analysis of PlPTC52 with highly homologous sequences annotated as PTC52 proteins screened from the NCBI database, and simultaneously included the PTC52 protein from Physcomitrium patens as the outgroup. The results showed that PlPTC52 clustered with VvPTC52 from Vitis vinifera in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1A). Multiple sequence alignment confirmed high sequence conservation among PlPTC52, VvPTC52, and AtPTC52, and they all contained a conserved Rieske domain common to non-haem iron oxygenase systems and a conserved PAO domain at the C-terminal (Figure 1B). Furthermore, TargetP analysis identified a predicted chloroplast-targeting peptide comprising 59 amino acids at the N-terminal region. Collectively, these findings suggested that PlPTC52 was an evolutionarily conserved protein.

Figure 1.

Sequences analysis of PlPTC52. (A) Phylogenetic relationships of PlPTC52 with homologous proteins. VvPTC52 (Vitis vinifera), MoPTC52 (Malania oleifera), HbPTC52 (Hevea brasiliensis), ZjPTC52 (Ziziphus jujuba), QsPTC52 (Quillaja saponaria), AgPTC52 (Alnus glutinosa), MrPTC52 (Morella rubra), PpPTC52 (Physcomitrium patens), AtPTC52 (Arabidopsis thaliana). PlPTC52 is highlighted with a green dot. The phylogenetic tree was built in MEGA 7.0 using the neighbor-joining approach based on p-distance, incorporating 1000 bootstrap replicates, support values are displayed at nodes; (B) Multiple sequence alignment of PlPTC52 and other homologs. The conserved Rieske domain was marked with black solid lines, and the conserved PAO domain was marked with green solid lines. The asterisk indicates the predicted cleavage site of the chloroplast transit peptide. Conserved residues are shaded in green, and blue boxes indicate positions with identical amino acids among the aligned sequences, as generated by ESPript 3.2 (https://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/index.php, accessed on 4 November 2025).

3.2. Dynamic Expression of PlPTC52 in Response to High Temperature Stress

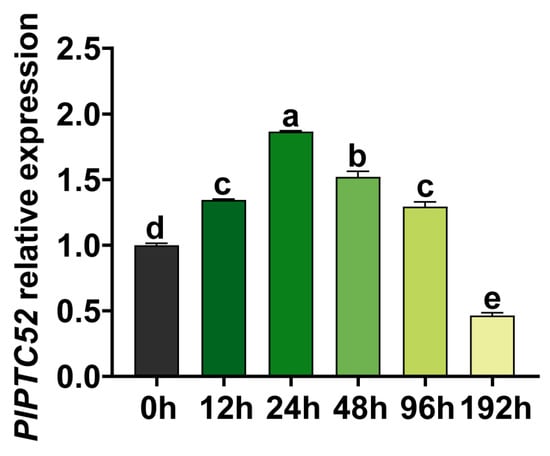

To investigate the temporal expression of the PlPTC52 gene under high temperature stress, qPCR was used to measure its transcript levels in P. lactiflora leaves sampled at 0, 12, 24, 48, 96, and 192 h following stress treatment. Our analysis revealed that PlPTC52 expression was initially low at 0 h, exhibited a significant increase at 12 h and 24 h, reached a peak at 24 h, and then declined progressively at 48 h, 96 h, and 192 h, with the minimum level recorded at 192 h (Figure 2). These findings indicated that the expression of PlPTC52 is transiently up-regulated by high temperature stress but is suppressed under prolonged exposure.

Figure 2.

Transcriptional analysis of PlPTC52 under high temperature stress. Expression levels were measured at 0, 12, 24, 48, 96, and 192 h, with the 0 h value normalized to 1. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

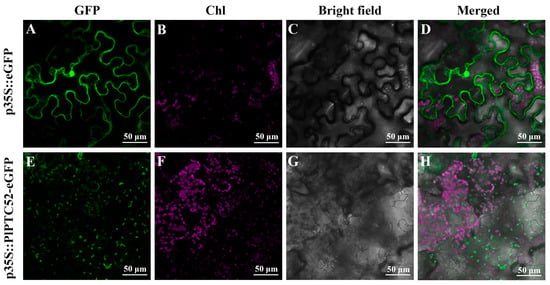

3.3. PlPTC52 Is Located in the Chloroplast

To further determine the expression characteristics of PlPTC52, it was fused with eGFP and transiently expressed in N. benthamiana leaves for subcellular localization. The 663 nm chloroplast autofluorescence was used to indicate chloroplast localization signals. Our analysis revealed that in the p35S::eGFP control, green fluorescence signal was widely distributed throughout the cells. In contrast, green fluorescence signal from the 35S::PlPTC52-eGFP fusion protein overlapped with chloroplast autofluorescence, indicating that PlPTC52 protein was specifically localized to the chloroplasts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of PlPTC52 in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. (A,E) Fluorescence signal from the 35S::eGFP and 35S::PlPTC52-eGFP constructs at 488 nm; (B,F) Chloroplast autofluorescence signal at 663 nm; (C,G) bright field images; (D) merged image of panels (A–C); (H) merged image of panels (E–G). Green fluorescence indicates GFP signals, while magenta fluorescence represents chloroplast autofluorescence. GFP; green fluorescence; Chl: chloroplast autofluorescence.

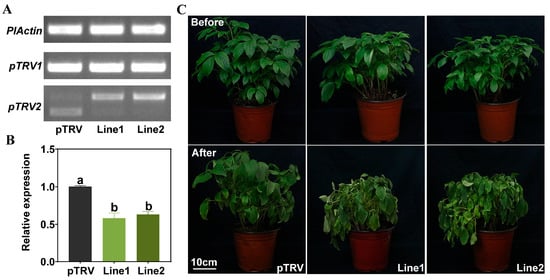

3.4. Silencing of PlPTC52 Decreases High Temperature Tolerance of P. lactiflora

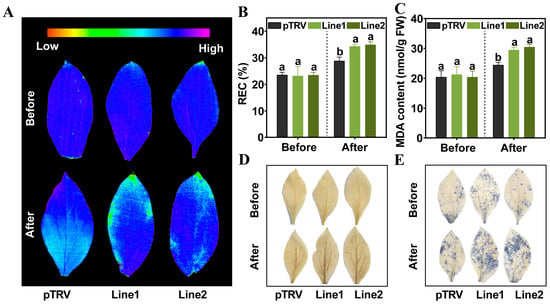

To assess the function of PlPTC52 in high temperature stress, PlPTC52 was silenced in P. lactiflora using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), with plants carrying the empty pTRV vector used as controls. Both control and silenced plants were grown until the leaf expansion stage, after which total RNA were extracted to validate transgenic lines. As shown in Figure 4A, amplification with PlActin-specific and pTRV1-specific primers produced clear bands in all plants. In contrast, amplification with pTRV2-specific primers yielded bands of different sizes in pTRV controls compared to PlPTC52-silenced lines 1 and 2. Moreover, qPCR analysis revealed that PlPTC52 expression in the two silenced lines decreased by 42% and 37%, respectively, relative to the pTRV controls (Figure 4B). Subsequently, these plants were subjected to high temperature stress and phenotype evaluation. Before high temperature treatment, all plants displayed robust, green foliage without discernible variations. Following high temperature stress, the control plants maintained relatively intact leaf morphology with minimal phenotypic alterations, while the PlPTC52-silenced plants exhibited severe stress symptoms, such as extensive wilting, leaf curling, and chlorosis (Figure 4C). Consistent with this phenotypic observation, these plants maintained lower photosystem II efficiency, reflected in decreased Fv/Fm values (Figure 5A). Concurrently, they exhibited significantly aggravated oxidative damage, with increased REC levels, elevated MDA contents, and enhanced ROS accumulation as visualized by DAB and NBT histochemical staining (Figure 5B–E). These findings indicated that silencing of PlPTC52 markedly compromised P. lactiflora’s high temperature tolerance.

Figure 4.

Positive plant identification and phenotypic observation of PlPTC52-silenced plants. (A) PCR validation of PlPTC52-silenced plants; (B) qPCR validation of PlPTC52-silenced plants. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05); (C) Phenotypic observation of PlPTC52-silenced plants after high temperature stress.

Figure 5.

Physiological indices measurement of PlPTC52-silenced plants. (A) Maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) value of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (B) Relative electrical conductivity (REC) level of the pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (C) Malondialdehyde (MDA) content of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (D) H2O2 accumulation detected by diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (E) O2·− accumulation detected by nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) staining of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.5. Overexpressing of PlPTC52 Increases High Temperature Tolerance of N. tabacum

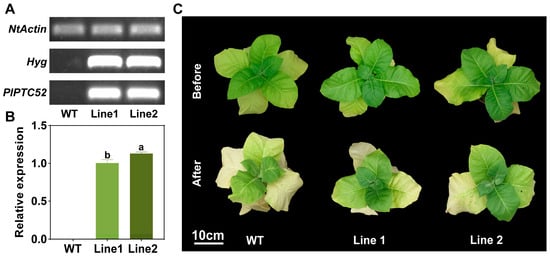

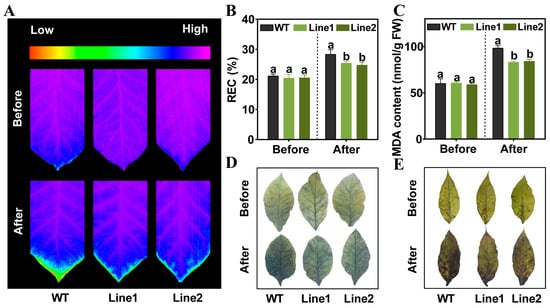

For functional validation of PlPTC52 in high temperature tolerance, two independent transgenic N. tabacum lines overexpressing PlPTC52 (lines 1 and 2) were generated. PCR analysis of genomic DNA using hygromycin-resistance and PlPTC52-specific primers confirmed transgene integration, with clear bands observed exclusively in transgenic plants (Figure 6A). Moreover, qPCR analysis revealed that PlPTC52 is highly expressed at the mRNA level in the overexpression lines, respectively (Figure 6B). Subsequently, these plants were exposed to high temperature stress, and their phenotypic traits were evaluated. Our observations indicated that prior to treatment, both the Wild-type (WT) and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants displayed robust, green foliage without discernible variations. Following high temperature stress, the WT plants exhibited pronounced stress symptoms, including wilting and chlorosis, whereas the PlPTC52-overexpressing plants retained healthier leaf morphology with minimal phenotypic alterations (Figure 6C). Consistent with the phenotypic differences, the PlPTC52-overexpressing plants exhibited higher Fv/Fm values (Figure 7A), along with reduced MDA content, decreased REC levels, and diminished ROS accumulation (Figure 7B–E). The above results confirmed that PlPTC52 could increase high temperature tolerance in plants.

Figure 6.

Confirmation and phenotypic analysis of PlPTC52-overexpressing plants. (A) PCR validation of PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (B) qPCR validation of PlPTC52-overexpressing plants. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05); (C) Phenotypic observation of PlPTC52-overexpressing plants after high temperature stress.

Figure 7.

Physiological indices of PlPTC52-overexpressing plants. (A) Fv/Fm value of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (B) REC level of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (C) MDA content of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (D) DAB staining of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (E) NBT staining of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

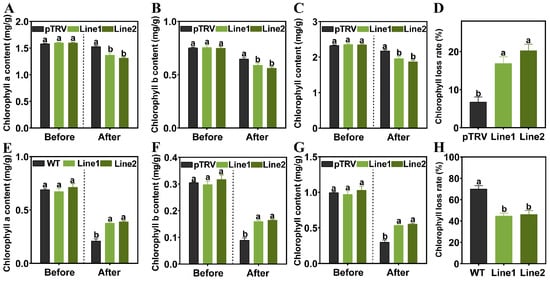

3.6. PlPTC52 Regulates High Temperature Tolerance by Reducing Chlorophyll Loss

Given the distinct phenotypic differences observed under high temperature stress, specifically, the PlPTC52-silenced plants exhibited obvious leaf chlorosis, while the PIPTC52-overexpressing plants maintained a higher degree of leaf greenness, with the pTRV and WT plants showing intermediate leaf coloration, we hypothesized that PlPTC52 regulated chlorophyll metabolism during high temperature stress. Chlorophyll contents were therefore measured in the silenced (PlPTC52-silenced P. lactiflora), overexpressing (PlPTC52-overexpressing N. tabacum), and control plants (pTRV and WT) under high temperature stress (Figure 8). While no significant differences were observed before stress imposition, high temperature stress led to a substantial decrease in chlorophyll content in all plant types, though the magnitude of reduction differed among genotypes. In the VIGS assay, the PlPTC52-silenced plants showed substantial reductions in chlorophyll a, b, and total content, accompanied by elevated loss rates, whereas the pTRV plants maintained higher chlorophyll retention with reduced chlorophyll loss (Figure 8A–D). Conversely, in overexpression assays, the WT plants suffered severe chlorophyll loss after stress, while the PlPTC52-overexpressing plants exhibited significantly preserved chlorophyll accumulation and reduced chlorophyll loss (Figure 8E–H). These findings indicated that PlPTC52 likely increased the high temperature tolerance of plants by reducing chlorophyll loss.

Figure 8.

Changes in chlorophyll content under high temperature stress. (A) Chlorophyll a content of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (B) Chlorophyll b content of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (C) Chlorophyll content of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (D) Chlorophyll degradation rate of pTRV and PlPTC52-silenced plants; (E) Chlorophyll a content of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (F) Chlorophyll b content of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (G) Chlorophyll content of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants; (H) Chlorophyll degradation rate of WT and PlPTC52-overexpressing plants. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

As the core pigment in plant photosynthesis, chlorophyll is responsible for light absorption and the conversion of light energy into carbohydrates. Maintaining chlorophyll metabolic balance is a critical physiological process that enables plants to withstand abiotic stresses and sustain photosynthetic efficiency [32,33,34]. Modulating the activity of key enzymes in chlorophyll biosynthesis and degradation pathways helps maintain chlorophyll metabolic balance and delay high-temperature-induced chlorophyll loss [35,36]. This study focused on the function of the PTC52 gene in P. lactiflora under high temperature stress, exploring its function in regulating chlorophyll metabolism and enhancing high temperature tolerance.

In the chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway, protochlorophyllide a (Pchlide a), a key chlorophyll biosynthetic intermediate, needs to be reduced to chlorophyllide under the catalysis of protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases (PORs). This step is the rate-limiting link in light-dependent chlorophyll biosynthesis [36,37]. In both A. thaliana and Hordeum vulgare, PTC52 localizes to the inner chloroplast membrane, where it associates with the translocon complex of the PORA precursor (pPORA), facilitating its transmembrane translocation. Importantly, PTC52 recognizes Pchlide a and functions as a Pchlide a oxygenase to catalyze its oxidation to Pchlide b. This structural modification substantially increases Pchlide’s affinity for PORA, thereby optimizing the chlorophyll synthesis pathway [22,24]. Consequently, once pPORA matures in the chloroplast stroma, it can immediately bind to the high-affinity substrate Pchlide b, preventing the accumulation of unmodified Pchlide a and improving light-harvesting efficiency in photosystem II. This function is similar to that of CAO, a homologous protein, which catalyzes Chlide b synthesis and regulates LHC protein import [38]. In the present study, the conserved domains of PlPTC52 from P. lactiflora showed high homology with family members from A. thaliana and V. vinifera. Subcellular localization analyses confirmed that PlPTC52 is primarily localized in chloroplasts, supporting its direct involvement in chlorophyll biosynthesis.

Research on the function of PTC52 homologs in other species has been limited but informative. For example, the tomato SIPTC52 gene, encodes a Rieske oxygenase, is induced by mycorrhizal symbiosis. Its expression is closely associated with arbuscule formation and regulated through hormone signaling pathways, thereby promoting symbiosis establishment [39]. In Ocimum basilicum, ObF8H-1, a member of the PTC52-like gene family, catalyzes the 8-hydroxylation of flavonoids, suggesting that the Rieske-type oxygenase family may have previously underappreciated roles in specialized plant metabolism [40]. In contrast, our study is the first to show that PTC52 from P. lactiflora is induced by high temperature stress, highlighting its potential role in high temperature stress.

To elucidate the role of PlPTC52 in high temperature tolerance, we generated PlPTC52-silenced P. lactiflora plants using VIGS. Silencing PlPTC52 significantly reduced the plants’ tolerance to high temperatures and caused marked physiological and metabolic disturbances. Under high temperature stress, PlPTC52-silenced plants exhibited substantial reductions in chlorophyll content, with a faster rate of chlorophyll loss compared to control plants. This evidence confirms that PTC52, similar to its function in A. thaliana and H. vulgare, is essential for chlorophyll biosynthesis in P. lactiflora, and its suppression disrupts this essential process [22,24]. Moreover, high temperature stress led to elevated accumulation of ROS products in the leaves of silenced plants. We propose that the loss of PTC52 activity blocked the conversion of Pchlide a to Pchlide b. As a key chlorophyll intermediate, Pchlide a can act as a photosensitizer under combined high temperature and light stress, generating singlet oxygen and toxic radicals upon light absorption, which contributes to excessive ROS accumulation [41]. Consistent with this, the PlPTC52-silenced plants showed increased MDA content and relative electrolyte leakage (REC), indicating aggravated membrane lipid peroxidation and compromised membrane integrity due to ROS-induced oxidative damage. In terms of photosynthetic performance, Fv/Fm values decreased significantly in silenced plants after high temperature treatment, reflecting severe impairment of photosystem II. This reduction is directly linked to the lower chlorophyll content and diminished capacity for light absorption and energy conversion. Supporting evidence comes from rice gry3 mutants, where defects in chlorophyll biosynthesis under combined high temperature and high light stress led to metabolic imbalances, excessive ROS accumulation, cell apoptosis, and compromised chloroplast integrity, ultimately reducing photosynthetic efficiency [35].

To further verify the functional conservation and application potential of PlPTC52, we constructed a PlPTC52 overexpression vector and introduced it into N. tabacum. Overexpression of PlPTC52 significantly enhanced the high temperature tolerance of transgenic plants, primarily by maintaining chlorophyll metabolic balance, reducing ROS accumulation, and protecting photosystem II efficiency and membrane integrity. Similar observations have been reported in wheat, where stay-green cultivars retain higher chlorophyll content and greater photosystem II efficiency under high temperature stress, resulting in superior yield traits compared to non-stay-green lines [3]. We propose that PlPTC52 helps maintain chlorophyll metabolic balance under high temperature stress by optimizing the supply of the chlorophyll precursor Pchlide b, while minimizing photooxidative damage caused by unconverted Pchlide a. This mechanism likely enables transgenic N. tabacum to exhibit a stay-green phenotype and improved high temperature tolerance, resembling the overexpression effects observed for CfCHLM [42].

5. Conclusions

This study establishes a clear functional link between PlPTC52 and high temperature tolerance in P. lactiflora. PlPTC52 plays a crucial role in maintaining chlorophyll metabolic balance, reducing ROS accumulation, and protecting photosystem II efficiency and membrane integrity under high temperature stress. These findings highlight PlPTC52 as a valuable genetic target for breeding strategies aimed at enhancing high temperature tolerance in plants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010082/s1, Table S1: Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Z.; methodology, D.Z.; validation, M.Z.; data curation, M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.T. and D.Z.; visualization, M.Z.; supervision, J.T. and D.Z.; project administration, J.T. and D.Z.; funding acquisition, J.T. and D.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Province Seed Industry Revitalization Unveiled Project (JBGS(2021)020), Forestry Science, Technology Innovation and Promotion Project of Jiangsu Province (LYKJ [2021]01), National Forest and Grass Science and Technology Innovation and Development Research Project (2023132012).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data can be found within the manuscript and its Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Latif, S.; Wang, L.P.; Khan, J.; Ali, Z.; Sehgal, S.K.; Babar, M.A.; Wang, J.P.; Quraishi, U.M. Deciphering the role of stay-green trait to mitigate terminal heat stress in Bread Wheat. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Krishnan, P.; Nayak, M.; Ramakrishnan, B. High temperature stress effects on pollens of rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 101, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Pan, Y.; Luo, L.H.; Zhang, G.L.; Deng, H.B.; Dai, L.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Tang, W.B.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, G.L. Quantitative trait loci associated with seed set under high temperature stress at the flowering stage in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 2011, 178, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.J.; Ding, Y.R.; Jin, J.Y.; Song, A.P.; Chen, S.M.; Chen, F.D.; Fang, W.M.; Jiang, J.F. Physiological and transcripts analyses reveal the mechanism by which melatonin alleviates heat stress in chrysanthemum seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 673236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.J.; Han, X.Y.; Wang, G.H.; Jing, Q.; Zhou, L.J.; Chen, S.M.; Fang, W.M.; Chen, F.D.; Jiang, J.F. Transcriptome analysis reveals chrysanthemum flower discoloration under high-temperature stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1003635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.M.; Jin, X.; Wang, M.S.; Liu, H.D.; Tian, W.L.; Xue, Y.D.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Wu, Y. Flower morphology, flower color, flowering and floral fragrance in Paeonia L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1467596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Chang, Q.S.; Hou, X.G.; Wang, J.Z.; Chen, S.D.; Zhang, Q.M.; Wang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J.K. The effect of high-temperature stress on the physiological indexes, chloroplast ultrastructure, and photosystems of two herbaceous peony cultivars. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 1631–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Agrawal, D.; Jajoo, A. Photosynthesis: Response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 137, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospísil, P. Production of reactive oxygen species by photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jespersen, D.; Zhang, J.; Huang, B.R. Chlorophyll loss associated with heat-induced senescence in bentgrass. Plant Sci. 2016, 249, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, X.Y.; Gu, L.M.; Liu, P.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.W.; Ren, B.Z. The effects of high temperature, drought, and their combined stresses on the photosynthesis and senescence of summer maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 289, 108525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.B.K.; Bhatt, S. Heat stress and it’s tolerance in wheat. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2413398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, S.; Burgess, P.; Jespersen, D.; Huang, B.R. Heat-induced leaf senescence associated with chlorophyll metabolism in bentgrass lines differing in heat tolerance. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, A.K.; Tripathy, B.C. Temperature-stress-induced impairment of chlorophyll biosynthetic reactions in cucumber and wheat. Plant Physiol. 1998, 117, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.K.; Chen, G.L.; He, M.M.; Wu, J.Q.; Wen, W.X.; Gu, Q.S.; Guo, S.R.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. ABI5 promotes heat stress-induced chlorophyll degradation by modulating the stability of MYB44 in cucumber. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H.; Guo, Y.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, J.L.; Dong, Y.P.; Hu, C.; Long, J.H.; Chen, Y. The superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family in perennial ryegrass: Characterization and roles in heat stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 226, 110061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, U.; Pradhan, D. High temperature-induced oxidative stress in Lens culinaris, role of antioxidants and amelioration of stress by chemical pre-treatments. J. Plant Interact. 2011, 6, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, K.L.; Zhu, F.Y.; Xie, Y.J. Advances in the biosynthetic regulation and functional mechanisms of glycine betaine for enhancing plant stress resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Y.K. Proline as a key player in heat stress tolerance: Insights from maize. Discov. Agric. 2024, 2, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Shekhar, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, N. Wheat 2-Cys peroxiredoxin plays a dual role in chlorophyll biosynthesis and adaptation to high temperature. Plant J. 2021, 105, 1374–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinbothe, S.; Bartsch, S.; Rossig, C.; Davis, M.Y.; Yuan, S.; Reinbothe, C.; Gray, J. A Protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) a oxygenase for plant viability. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boij, P.; Patel, R.; Garcia, C.; Jarvis, P.; Aronsson, H. In vivo studies on the roles of Tic55-related proteins in chloroplast protein import in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 1397–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinbothe, S.; Quigley, F.; Gray, J.; Schemenewitz, A.; Reinbothe, C. Identification of plastid envelope proteins required for import of protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase A into the chloroplast of barley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2197–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, S.; Monnet, J.; Selbach, K.; Quigley, F.; Gray, J.; von Wettstein, D.; Reinbothe, S.; Reinbothe, C. Three thioredoxin targets in the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts function in protein import and chlorophyll metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4933–4938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.T.; Chen, Z.J.; Fang, Z.W.; Meng, J.S.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D.Q. PoWRKY69-PoVQ11 module positively regulates drought tolerance by accumulating fructose in Paeonia ostii. Plant J. 2024, 119, 1782–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunilkumar, G.; Vijayachandra, K.; Veluthambi, K. Preincubation of cut tobacco leaf explants promotes Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by increasing vir gene induction. Plant Sci. 1999, 141, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, M.T.; Qiu, S.Y.; Qian, Y.; Tao, J.; Zhao, D.Q. Transcriptome sequencing provides insights into high-temperature-induced leaf senescence in herbaceous peony. Agriculture 2024, 14, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.L. GraphPad prism, data analysis, and scientific graphing. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1997, 37, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.J.; Zhao, M.J.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.X.; Yu, L.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Ma, J.F.; Cao, X.F.; Zhang, S.B.; Chi, W.; et al. LcASR enhances tolerance to abiotic stress in Leymus chinensis and Arabidopsis thaliana by improving photosynthetic performance. Plant J. 2024, 120, 2752–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanapal, A.P.; Ray, J.D.; Singh, S.K.; Hoyos-Villegas, V.; Smith, J.R.; Purcell, L.C.; Fritschi, F.B. Genome-wide association mapping of soybean chlorophyll traits based on canopy spectral reflectance and leaf extracts. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.L.; Morrison, M.J.; Voldeng, H.D. Leaf greenness and photosynthetic rates in soybean. Crop Sci. 1995, 35, 1411–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.Z.; Zhang, A.P.; Ruan, B.P.; Hu, H.T.; Guo, R.; Chen, J.G.; Qian, Q.; Gao, Z.Y. Identification of Green-Revertible Yellow 3 (GRY3), encoding a 4-hydroxy- 3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase involved in chlorophyll synthesis under high temperature and high light in rice. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1171–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Tabassum, J.; Sheng, Z.H.; Lv, Y.S.; Chen, W.; Zeb, A.; Dong, N.N.; Ali, U.; Shao, G.N.; Wei, X.J.; et al. Loss-of-function of PGL10 impairs photosynthesis and tolerance to high-temperature stress in rice. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, T.; Lima, D.; Mason, M.E.; Apel, K.; Armstrong, G.A. Arabidopsis light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase A (PORA) is essential for normal plant growth and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 78, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinbothe, C.; Bartsch, S.; Eggink, L.L.; Hoober, J.K.; Brusslan, J.; Andrade-Paz, R.; Monnet, J.; Reinbothe, S. A role for chlorophyllide a oxygenase in the regulated import and stabilization of light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 4777–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero-Rosales, N.; Martín-Rodríguez, J.A.; Ho-Plágaro, T.; García-Garrido, J.M. Identification and expression analysis of the arbuscular mycorrhiza-inducible Rieske non-heme oxygenase Ptc52 gene from tomato. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 237, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berim, A.; Park, J.J.; Gang, D.R. Unexpected roles for ancient proteins: Flavone 8-hydroxylase in sweet basil trichomes is a Rieske-type, PAO-family oxygenase. Plant J. 2014, 80, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphylidès, C.; Krischke, M.; Hoeberichts, F.A.; Ksas, B.; Gresser, G.; Havaux, M.; Van Breusegem, F.; Mueller, M.J. Singlet oxygen is the major reactive oxygen species involved in photooxidative damage to plants. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.J.; Xu, J. CfCHLM, from Cryptomeria fortunei, promotes chlorophyll synthesis and improves tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Forests 2024, 15, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.