Abstract

Smart farming integrates digital technologies to optimize agricultural production and promote sustainability. Its impact depends both on technological development and adoption by farmers. Research shows significant progress, but technical and socio-behavioral gaps remain, requiring integrated approaches to strengthen its contribution to the SDGs. In this context, scientific research on smart farming has grown significantly, becoming a key axis for the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The aim of this study was to analyze the evolution, structure, and impact of scientific production in smart farming, identifying its main trends, authors, journals, and contributions to the SDGs. To this end, a bibliometric analysis was applied to 1580 articles indexed in the Web of Science (WoS) database, using productivity, citation, and impact indicators based on Price’s, Lotka’s, Bradford’s, and Zipf’s laws, as well as the Hirsch index. The results reveal important growth in scientific production between 2014 and 2024, with a strong concentration in high-impact journals and international collaboration networks. In conclusion, smart farming represents an engine of innovation and sustainability, integrating science, technology, and digital management to address the global challenges of food security, climate change, and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Smart farming has established itself as an advanced data-driven approach to agricultural management that integrates digital technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), remote sensors, wireless communication systems, cloud and edge computing, artificial intelligence, and advanced analytics. Its purpose is to optimize production processes and improve efficiency in the use of natural resources [1,2,3]. This technological paradigm is emerging in response to structural challenges in the agricultural sector, including growing food demand, resource scarcity, climate variability, and the need to move toward more sustainable production systems [4,5].

From a sustainability perspective, smart farming promotes more precise and localized management of critical inputs (water, fertilizers, energy, and agrochemicals), helping to reduce negative environmental impacts, increase production resilience, and strengthen food security [6,7]. The literature agrees that smart agriculture is not only aimed at increasing productivity, but also at simultaneously improving the environmental and economic performance of farms [8,9].

However, smart farming should be understood as a socio-technical system in which the value generated by digital technologies depends largely on the farmer’s ability to adopt, interpret, and use information in their decision-making [10,11]. Technological adoption involves processes of learning, trust, and behavioral change, positioning farmers as central actors in the transition to more sustainable and digitized agriculture [12,13].

The main characteristics of smart farming include intensive sensorization of the agricultural environment, connectivity between heterogeneous devices, real-time monitoring of production and environmental variables, and intelligent processing of large volumes of data to support decision-making [14,15]. These capabilities enable precision agriculture practices—such as site-specific irrigation, fertilization, and phytosanitary control—that reduce waste and environmental externalities, aligning this approach with the principles of agricultural sustainability [16,17].

The use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), wireless sensor networks, and deep learning algorithms—especially convolutional neural networks—has proven highly effective in the early detection of diseases, diseases, and pests, as well as in predicting yields and optimizing livestock management [18,19,20]. Likewise, low-energy communication technologies, such as LPWAN and LoRaWAN, facilitate the deployment of solutions in rural areas with limited infrastructure, expanding the potential for the adoption of smart farming [21,22].

However, the effective adoption of these technologies does not depend exclusively on their technical performance. Factors associated with farmer behavior—perceived usefulness, ease of use, trust in digital systems, technological literacy, and perceived risks related to data security and privacy—have a decisive influence on the intention to use and actual adoption of smart farming [23,24]. In this regard, theoretical frameworks such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) have been widely used to explain adoption dynamics in the agricultural sector [10].

The state of the art shows rapid growth in smart farming research, with an increasing emphasis on integrated IoT platforms, embedded artificial intelligence, edge computing, and advanced analytics to improve production efficiency and mitigate the effects of climate change [11,22]. Recent studies report significant improvements in the optimization of water, fertilizer, and pesticide use, as well as in the reduction in production losses, reinforcing the potential of smart farming as a tool for advancing toward more sustainable agricultural systems [5,19].

At the same time, significant advances have been made in the use of deep learning and computer vision for crop monitoring and early disease detection, achieving high levels of accuracy and contributing to more efficient and environmentally responsible management [25,26]. However, significant gaps remain in terms of data quality and noise, device durability and scalability, interoperability between systems, and cybersecurity risks, all of which may limit the sustained adoption of these technologies [27,28].

Studies consistently agree that the impact of smart farming on agricultural sustainability depends not only on technological development, but also on understanding farmer behavior and designing adoption strategies that integrate training, data governance, and institutional trust [29,30]. Consequently, the state of the art suggests the need for integrated approaches that articulate technological innovation, environmental sustainability, and socio-behavioral dimensions as a key condition for the consolidation of smart farming and its effective contribution to long-term sustainable agriculture.

Accordingly, this study seeks to investigate: What are the emerging trends in smart farming research? How do these most relevant studies contribute to the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals? And who are the key actors driving this knowledge production? Consequently, this study aims to understand how the field of smart farming studies has evolved and what its main internal dynamics are. To this end, it analyzes the evolution, structure, and impact of scientific production in this topic, identifying emerging trends, influential authors and journals, as well as their contribution to the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

2. Methods

2.1. General Approach

This research adopted a bibliometric approach aimed at analyzing key actors, collaboration networks, and emerging trends in scientific production on Smart Farming, emphasizing how these contributions support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Widely recognized methods and recommendations in bibliometric studies were applied to ensure rigor and reproducibility [31,32].

Unlike the various review methods (narrative, systematic, mixed, rapid, exploration, and multiple review integration approaches), bibliometric methods maximize search rigor but replace the qualitative evaluation and screening of extracted documents and their subsequent reduction (exclusion) and synthesis [33]. Through a set of eponymous laws that use subsampling, estimation, and calculation techniques to determine quantitative patterns for a comprehensive evaluation set of documents under study [34].

2.2. Data Collection

The primary data source was the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC), one of the most recognized and widely used international databases for analyzing scientific output [35]. The search was conducted on 17 October 2025, using the search vector: {TS = (Smart NEAR/O Farming)}, restricted to records containing the term in the title, abstract, keywords authors or keywords plus.

- Inclusion criteria:

- Document type: articles.

- Language: unrestricted (predominantly English).

- Time: unrestricted.

- Thematic coverage: all categories available on the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC).

2.3. Analytical Techniques Applied

The analytical process was structured into four main dimensions: scientific productivity, academic impact, scientific networks, and relation to the SDGs.

2.3.1. Scientific Growth

The Price’s Law was applied to analyze the exponential (J) or logistic (S) growth of science by evaluating the annual increase in the number of publications as an indicator of a consolidated critical mass of knowledge in the field. These laws also explain scientific obsolescence by dividing the bibliographic corpus into two semi-periods based on the chronological median, distinguishing between the contemporary and obsolete literature, and identifying classic works recognized for their lasting influence and high citation rates [36,37,38].

2.3.2. Scientific Productivity

Bradford’s law, his study concentrates on the journals, mainly in what is known as Bradford’s core, the smallest subset of journals that manages to concentrate one third of the total number of documents studied. The subsets that manage to concentrate the other thirds of documents according to their increasing order in number of journals are known as zones 1 and 2. Although all the attention is focused on the Bradford core for being the production environment that tends to congregate the most specialized authors, reviewers, and editors in a specific topic of study [39,40].

In the other hand, Authors with the highest number of publications in Smart Farming were identified which prolific authors. To estimate the concentration of production, Lotka’s Law [41] was applied, which posits that a small proportion of authors produce most published works.

2.3.3. Academic Impact

The Hirsch index (h-index) was used to measure researcher impact, allowing for the simultaneous evaluation of productivity and scientific influence [42,43]. This method helped identify the most influential authors and research groups in the field by citations of published documents. Additionally, Clarivate’s Web of Science SDG classification was used to determine the extent to which Smart Farming studies contribute to global sustainability goals, offering insights into their social, environmental, and policy relevance (classification lists that we have reported in full as Supplementary Material).

2.3.4. Relationships and Scientific Networks

Network analysis was used to explore the relational structure of the scientific community through keyword co-occurrence networks: to characterize thematic organization [44].

2.3.5. Relationship Between Academic Impact and Sustainable Development Goals

The selection of the 30 most cited articles on the topic of Smart Farming is grounded in the principles of classical bibliometrics, which recognize that the most frequently cited works represent the primary centers of influence and the consolidation of scientific knowledge. This approach enables the identification of the conceptual and methodological cores that have guided the evolution of the smart farming field, in accordance with [45], who note that the most cited articles form the foundation of the central intellectual structures of a scientific discipline. Considering the effects of Smart Farming, it is assumed that the most frequently linked SDGs are SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), and SDG 13 (Climate Action), although this relationship must be analyzed rigorously.

2.4. Analytical Procedure

Eponymous bibliometric laws were applied: Price’s Law describing exponential or logistic growth and obsolescence [36,37,38]; Lotka’s Law explaining unequal productivity distribution among authors [41]. Zipf’s Law analyzing the frequency of keyword usage [46]. Hirsch’s h-index evaluating the relationship between productivity and impact [42,43]. and Bradford’s Law [39,45,46] assessing journal dispersion. Together, these models contextualized the results, supporting the identification of epistemic communities and strategic actors in Smart Farming research.

Software tools used:

- VOSviewer (Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden, The Netherlands, v.1.6.19): for network analyses (co-authorship, keyword co-occurrence) and visualization of thematic clusters.

- Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA): for applying Price’s, Bradford’s, and Lotka’s laws and graphically representing annual publication trends.

- SPSS (IBM, New York, NY, USA, v.23): for generating adjusted models for applying Price’s, exponential fit and S fit.

Data visualization was conducted using VOSviewer [47], a tool specialized in mapping bibliometric networks, generating visual representations of authors, institutions, keywords, and emerging topics. This facilitated the identification of thematic clusters, high-knowledge density zones, and patterns of international collaboration.

2.5. Study Limitations

This analysis was limited to documents indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC). Although a high degree of overlap exists between WoS, Scopus, and Google Scholar, differences in regional coverage may affect the results. Integrating multiple sources presents methodological challenges such as duplication, inconsistent coverage, and citation discrepancies [48,49,50]. Additionally, the bibliometric approach, being quantitative and correlational, does not address the qualitative or interpretative dimensions of content, which are typically examined through systematic reviews [33].

Table 1 analyzed corpus comprises 1580 articles published between 1983 and 2025, distributed across 582 scientific sources and authored by 6244 researchers. The bibliometric analysis applied Price’s, Bradford’s, Lotka’s, and Zipf’s Laws, as well as Hirsch’s h-index, revealing classical patterns of growth, dispersion, and scientific productivity.

Table 1.

Description of the analyzed bibliographic corpus.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Scientific Growth

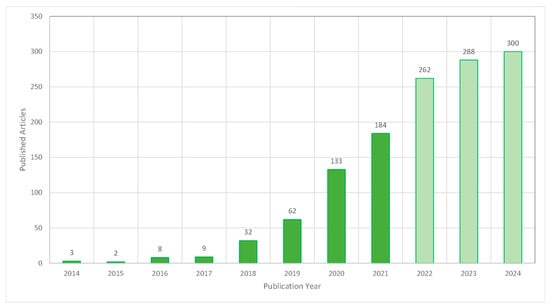

The bibliometric search identified a total of 1580 articles on smart farming published between 1983 and 2025. During the first period (1983–2013), scientific output remained limited, with only nine articles published at an irregular rate of zero to two per year. However, starting in 2014, there was a significant change, with no more years with blank results, and 1571 publications produced up to 2025, evidence of a strong boom in research in the field of smart farming (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Published articles in WoSCC on Smart Farming (1983–2025).

Consequently, scientific production exhibits exponential growth, fitting Price’s Law with an adjustment coefficient (R2) of 92.7%, confirming the rapid expansion of knowledge in Smart Farming within the broader digital transformation of agri-food systems. The contemporaneous semi period is dated between 2023 and 2025, 55% of the total studies were published, driven by post-pandemic digitalization and the widespread use of IoT, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and cyber-physical systems. Thus, knowledge about smart farming is renewed every three years.

Although publications increased from 9 in 2017 to 300 in 2024, representing growth of more than 3200%, this reflects an acceleration in the study of this topic and the renewal of current theoretical and methodological frameworks. The slowdown in the curve over the last three full years has led us to analyze the growth of the S curve, for which there is also an excellent degree of fit (R2 = 92.8%), reflecting the proximity to reaching maturity in the field and the presumed consolidation of scientific networks (See Table 2) [36,37,38].

Table 2.

Temporal trend of the analyzed bibliographic corpus.

The bars represent the total number of articles published on Smart Farming each year, with the lighter colored bars corresponding to the contemporary half-period or most recent median.

Both models presented in Table 2 show excellent fit (R2 ≈ 0.93), with very high correlations and robust statistical significance (p < 0.001). The exponential model indicates continuous growth in published articles based on the year of publication, describing a dynamic of accelerated expansion with no upper limit. In contrast, the S model introduces a saturation behavior: although initial growth is rapid, it progressively slows and tends to stabilize around a maximum value (reflected in the constant of 1120.495) suggesting that the scientific domain approaches a point of diminishing returns in publication volume. The difference in coefficients reflects this logic: the exponential depends directly on PY, while the S depends on the inverse transformation (1/PY), capturing the slowdown in growth characteristic of mature or saturated research areas. In practical terms, both models fit almost equally well, but the S model offers a more realistic interpretation in contexts where academic production naturally converges toward a structural or institutional limit.

3.2. Analysis of Scientific Productivity

These articles were published in 582 journals (See Table 3), though in low concentration. The publications are grouped primarily within nine core journals, as detailed in the Bradford Zone below.

Table 3.

Bradford’s Zones.

The percentage error between empirical and theoretical series is expressed by Equation (1).

This indicates that the theoretical value exceeds the empirical value by approximately 1.03%, showing a very small deviation between the two curves and a good fit to the theoretical model. Table 4 shows a characterization of the Bradford core, whose journals all belong to the first quartile (Q1), although with impact factors ranging from 2.7 to 15.1, with a high concentration of Gold Open Access journals from the publisher MDPI (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute), a publishing company created in 2010, and that has experienced high growth in recent years.

Table 4.

Journals in the Bradford nucleus.

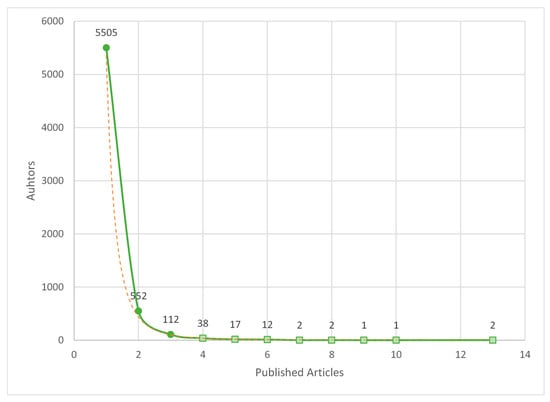

The 1580 articles analyzed were produced by 6244 authors. According to Lotka’s Law, authorship distribution follows an exponential pattern with a coefficient of determination (R2) exceeding 99%, confirming a prolific concentration of contributors. Applying Lotka’s model [41] and complementing it with the Hirsch index (h-index) [42], an approximate calculation of prolific authors ( = 80) revealed that 75 authors had published 4 or more articles, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Prolific authors in Smart Farming research. The green line represents the number of authors per number of published articles, while the light green squares above the green line show authors with four or more articles (75 authors). The segmented orange line is the fit to the potential decay curve.

The results of the adjustment to the power model show that author productivity in the field follows Lotka’s Law very closely (See Table 5). The model has an R = 0.978 and an R2 = 0.956, indicating that more than 96% of the variability in the number of authors is explained by the number of articles published, with an adjusted R2 of 0.951 confirming the stability of the model. The ANOVA supports this statistical robustness (F = 197.064; p < 0.001), demonstrating that the relationship is not random. The predictor coefficient (B = −0.265; p < 0.001) reveals the negative slope characteristic of Lotka’s Law: as the number of articles increases, the number of authors capable of producing them decreases systematically. The value of the constant (10.438) completes the logarithmic equation that describes this distribution. Taken together, these results confirm a highly unequal productivity structure, where a few authors concentrate a greater share of production, consistent with classic patterns in bibliometrics.

Table 5.

Prolific authors of the analyzed bibliographic corpus.

3.3. Analysis of Academic Impact

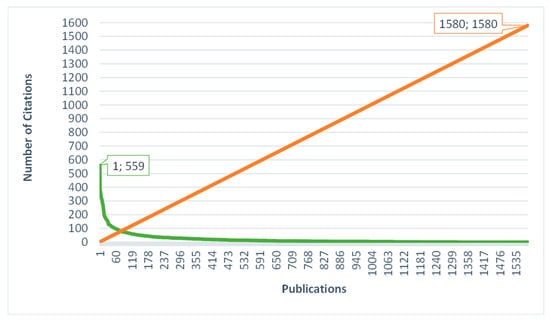

The Hirsch index (h = 79) indicates that 79 articles have received at least 79 citations each, showing a high concentration of scientific impact within a small corpus of publications (5% of 1580). Figure 3 illustrates the application of Hirsch’s law to the field of smart farming. The green curve corresponds to a Pareto distribution of citations, where a highly influential article reaches 559 citations and the rest decline sharply, reflecting that a few seminal works account for much of the academic recognition. In contrast, the orange curve represents the cumulative count of publications, which rises from 1 to 1580, showing the progressive growth of the scientific corpus. Together, both curves show a field characterized by a growing volume of production, but with an impact highly concentrated in a limited number of fundamental works [42].

Figure 3.

Prolific concentration of contributors. The green line represents the number of citations per number of published articles (from 559 to 0). The orange line is the sum of the count of articles from 1 to 1580.

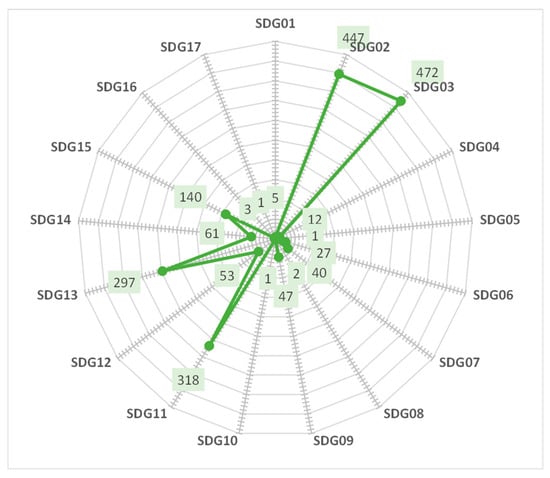

In addition to the traditional citation-based impact resulting from recognition by the international scientific community, publications on Smart Farming are catalogued by WoS according to their impact in contributing new knowledge to the advancement of the SDGs. Thus, 1217 articles (77% of 1580) are associated by WoS (Clarivate) with between one and six SDGs. These contributions, without discounting duplicate contributions in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Prolific concentration of contributors.

3.4. Analysis of Relationships and Scientific Networks

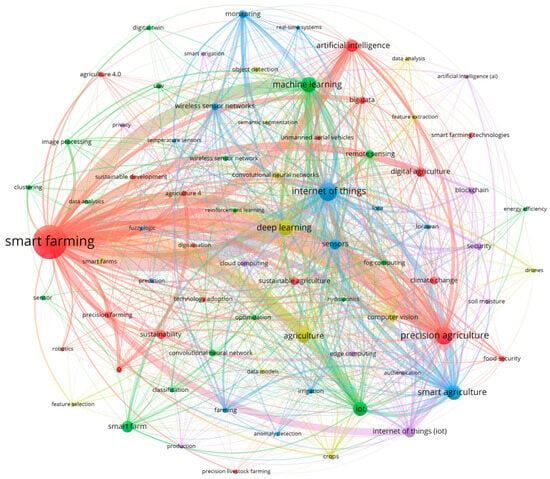

In the Keyword Co-occurrence Analysis conducted across 1580 articles, a total of 4.822 Authors Keywords (AKW) were identified. Applying the square root method (), 76 AKW with a minimum of 10 occurrences were selected for analysis. Thus, the graph in Figure 5 illustrates an interdisciplinary map showing how contemporary agriculture is being transformed through the integration of emerging technologies. Each cluster represents a complementary dimension of the agro-technological ecosystem, from physical infrastructure to digital governance and sustainability in Smart Farming research.

Figure 5.

Author keywords co-occurrence network in Smart Farming research. The colors of each node correspond to the five clusters mentioned above, while the colors of the lines depend on the color of the nodes they connect.

Five well-defined sectoral clusters have emerged, which are presented below, indicating the occurrences (O) and centrality (C) for the main AKWs (see details in Supplementary Material):

- The red cluster is clearly dominated by keywords associated with the digital transformation of farming, with “smart farming” (O:605, C:96%) and “precision agriculture” (O:165, C:88%) as central themes. The presence of concepts such as artificial intelligence, big data, digital agriculture, robotics, unmanned aerial vehicles, and digitalization shows a strong emphasis on advanced technologies applied to agricultural production. At the same time, terms related to sustainability (sustainability, sustainable agriculture, climate change, food security, sustainable development) appear, indicating that digitalization is not only analyzed as technological innovation, but also as a tool for addressing environmental and production challenges. The coexistence of precision livestock farming, technology adoption, and agriculture 4.0 reinforces the idea of a field in full transition toward intelligent, automated, and efficiency-oriented systems.

- The blue cluster is clearly structured around the technological infrastructure that enables smart farming, with a strong emphasis on the Internet of Things (O:180, C:89%) as the connecting thread. The terms smart agriculture, sensors, monitoring, and wireless sensor networks show that the cluster’s focus is on continuous data capture in the field, using distributed sensor networks and low-power communication systems. The presence of specific technologies such as LoRa and LoRaWAN reinforces the idea of solutions geared toward long-range rural connectivity, which is essential for agricultural environments. Concepts such as anomaly detection, prediction, fuzzy logic, and real-time systems indicate that it is not only about sensorization, but also about intelligent data processing, geared towards operational decision-making (irrigation, environmental monitoring, crop control). Taken together, the cluster represents the operational and technical layer that enables automation and continuous monitoring in smart agricultural systems.

- The green cluster is clearly oriented towards the use of advanced artificial intelligence and distributed computing techniques applied to smart farming systems. The dominant terms—machine learning (O:120, C:79%), IoT (O:101, C:75%), and smart farm (O:74, C:53%)—show that the cluster’s focus is on integrating machine learning models with connected infrastructures to optimize agricultural processes. The presence of remote sensing, image processing, UAV, and convolutional neural networks indicates a strong emphasis on computer vision and image analysis, especially for crop monitoring, pattern detection, and automated classification. Concepts such as fog computing, wireless sensor networks, data analytics, and digital twins suggest a more complex technological architecture, where processing is distributed between local devices and digital platforms, enabling real-time simulation, prediction, and control. In addition, terms such as optimization, clustering, reinforcement learning, and energy efficiency reveal an interest in improving operational performance, reducing costs, and increasing energy efficiency. Together, this cluster represents the algorithmic and intelligent layer of the digital agricultural ecosystem.

- The yellow cluster is clearly focused on the application of advanced deep learning and computer vision techniques to the analysis of crops and agricultural systems. The dominant term, deep learning (O:123, C:64%), together with computer vision (O:37, C:39%) and convolutional neural networks (O:24, C:31%), shows that the core theme is the use of deep neural architectures to interpret images and visual data from the agricultural environment. The presence of object detection, semantic segmentation, feature extraction, and feature selection confirms that the focus is on crop recognition, classification, and segmentation tasks, which are essential for automating processes such as pest detection, yield estimation, and phenotypic monitoring. The use of drones and data models suggests that the images come from both aerial platforms and terrestrial sensors, integrating into broader analytical models. Taking together, this cluster represents the intersection between computer vision, deep learning, and crop analysis, aimed at improving the accuracy and autonomy of intelligent agricultural systems.

- The purple cluster is organized around secure digital infrastructure for smart agriculture, with a clear emphasis on the protection, management, and reliability of data generated by IoT systems. The dominant term, Internet of Things (IoT) (O:67, C:75%), indicates that the starting point is the connectivity of agricultural devices. However, unlike the second cluster—focused on sensorization and monitoring—here concepts such as security (O:32, C:41%), blockchain (O:28, C:39%), authentication (O:12, C:17%), and privacy (O:10, C:27%) appear here, revealing an explicit concern for cybersecurity, data integrity, and trust mechanisms in digitized agricultural environments. The presence of cloud computing (O:27, C:45%) and edge computing (O:22, C:44%) shows that the cluster also addresses the hybrid computing architecture needed to process agricultural data efficiently, balancing latency, storage, and security. Terms such as soil moisture and smart irrigation connect this infrastructure with specific applications, especially in water management, where data reliability is critical for decision-making. Taken together, this cluster represents the security, data governance, and computational architecture that supports modern smart agriculture.

This distribution demonstrates the interdisciplinary nature of Smart Farming research, integrating management, technology, and sustainability perspectives. Figure 5 shows the keyword co-occurrence network generated with VOSviewer using a full count method of the 4822 AKWs, selecting the 76 with 10 or more occurrences, and spatial normalization with an association method whose layout was adjusted to an attraction of 4 and a repulsion of −10. The lines (arcs) are total 1066 and represented with a variation in maximum line thickness and a minimum representation value (link strength) of 1.

In addition to observing the 76 AKWs organized into five colors by cluster, the strongest link strengths (LS) between AKW dyads are visualized: Smart farming—Precision agriculture (LS:101), Smart farming—Internet of things (LS:81), Smart farming—Machine Learning (LS:56), Smart farming—Deep learning (LS:54), Smart farming—Artificial intelligence (LS:46), Smart farming—Digital agriculture (38), among others.

3.5. Analysis of Relationship Between Academic Impact and Sustainable Development Goals

Finally, the connection between Smart Farming research and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was evaluated (See Table 6). The results show that the most strongly impacted SDGs are:

Table 6.

Distribution of Smart Farming research according to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

- SDG 2: Zero Hunger (447 articles), demonstrating Smart Farming’s contribution to productivity, food security, and agricultural sustainability.

- SDG 3: Good Health (472 articles) is strongly represented, driven by research reducing chemical inputs, improving food quality and traceability, and enhancing safety through automation.

- SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities (318) where Smart Farming technologies such as vertical farming, urban agriculture systems, and controlled environment agriculture support sustainable urban development and resilient food systems.

- SDG 13: Climate Action (297 articles), reflecting the growing interest in mitigating climate change through resilient, low-emission agricultural practices.

- SDG 15: Life on Land (140 articles), highlighting the field’s strong orientation toward digitalization, automation, and technological innovation in agriculture.

The data presented in Table 6 illustrate the comprehensive contribution of Smart Farming to the SDGs, confirming its interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral nature in promoting global sustainability and digital innovation in agriculture.

The analysis of the thirty most cited papers (See Table 7) shows a pattern that is consistent with the overall distribution of the 1580 articles analyzed. These highly influential publications reveal a strong alignment with the most impacted SDGs. A substantial portion of the studies highlight Smart Farming’s contribution to SDG 2 (Zero Hunger, 447 articles) through advances in yield prediction, detection of pests and diseases, precision irrigation, and resource-efficient production systems.

Table 7.

Characterization of Smart Agriculture and its relationship with the Sustainable Development Goals.

These innovations strengthen food security, enhance productivity, and support sustainable agroecosystems particularly for smallholder farmers. Likewise, SDG 3 (Good Health 472 articles) emerges strongly due to research focused on reducing chemical inputs, improving food traceability, and enhancing occupational safety through automation, sensing technologies, and early warning systems. A significant contribution is also observed in SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities, 318 articles), where technologies such as urban agriculture, vertical farming, and controlled environment agriculture support resilient food systems and sustainable urban development. Although less frequent, SDG 13 (Climate Action, 297 articles) reflects growing scientific interest in climate-smart agriculture, emissions reduction, and adaptive technologies designed to strengthen resilience to climate variability.

Finally, SDG 15 (Life on Land, 140 articles) captures research linked to biodiversity protection, soil conservation, and sustainable land-use practices supported by sensor networks, monitoring systems, and precision management tools. Overall, these findings demonstrate that Smart Farming research not only accelerates agricultural digitalization but also positions sustainability, food security, public health, and climate resilience as interconnected pillars of global agricultural development.

4. Discussion

The bibliometric analysis of 1580 articles confirms that Smart Farming has established itself as a strategic scientific topic within the digital transformation of the agri-food sector. Scientific output shows sustained exponential growth, with more than 90% of studies published between 2017 and 2025, a pattern that coincides with that reported by Armenta-Medina et al. [80], Sott et al. [81], and Latino et al. [82], who also document an accelerated increase in publications on digital agriculture over the last two decades. This behavior, consistent with Price’s Law [36,37], suggests that the field has evolved from an emerging phase to a scientific maturity stage, characterized by the consolidation of theoretical, methodological, and technological frameworks.

The study results confirm the centrality of technologies like IoT, artificial intelligence, machine learning, computer vision, big data, and cyber-physical systems, which is in line with the findings of Kamran et al. [83], Bhardwaj et al. [84], Patil et al. [85], Gamage et al. [86], and García-Vázquez et al. [87]. In particular, the identification of thematic clusters associated with IoT, sensors, UAVs, machine learning, and precision agriculture reflects the same conceptual structure described by Sott et al. [81] and Kushartadi et al. [88], who highlight that these domains constitute the technological drivers of the digital agricultural ecosystem. The presence of terms such as remote sensing, wireless sensor networks, climate-smart agriculture, and digital twins also coincides with the evolutionary patterns described by Armenta-Medina et al. [80], who document the transition from immature georeferenced techniques to advanced systems based on aerial and terrestrial sensorization.

Likewise, the results of this study are in line with the recent literature on new technological frontiers, such as blockchain and agriculture 5.0. Apeh and Nwulu [89] show that blockchain has experienced exponential growth in applications for traceability, food safety, and trust in the supply chain, which coincides with the presence of this term in the clusters of our analysis. Similarly, Ragazou et al. [90] and Corallo et al. [91] highlight the transition towards energy-efficient and socio-technical models characteristic of Agriculture 5.0, which is reflected in the growing presence of concepts such as energy efficiency, renewable energy, and sustainable development in our corpus of articles.

In terms of scientific productivity, the author’s distribution adjusted to Lotka’s Law reveals a highly concentrated structure, where a small core of researchers produces a significant proportion of the articles. This pattern coincides with that noted by Bhardwaj et al. [84] and García-Vázquez et al. [87], who highlight that agricultural digitization is characterized by consolidated collaboration networks and the presence of highly specialized research groups, especially in China, the United States, India, and Brazil. The strong concentration of publications in Q1 journals—such as Sensors, Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, and IEEE Access—reinforces this idea, showing that the field has achieved a level of visibility and specialization comparable to that reported in previous studies on digital agriculture [82].

Citation patterns, reflected in an h-index of 79, show a highly influential scientific community, with seminal works that far exceed 500 citations. This behavior is consistent with that observed by Sott et al. [81] and Latino et al. [82], who identify a small set of articles that act as conceptual pillars of the field. The Pareto distribution observed in this study confirms that scientific production in Smart Farming is structured around a central intellectual core of prolific authors, from which new lines of research are articulated, especially in applied AI, predictive models, agriculture 4.0 and 5.0, and decision support systems.

In relation to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the results show strong alignment with global sustainability priorities. The predominance of SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) coincides with the findings reported by Patil et al. [85] and Gamage et al. [86], who highlight the role of sensorization and automation in reducing health risks and improving food quality. SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), with 447 articles, is in line with the findings of Kushartadi et al. [88] and Dutta et al. [92], who emphasize the contribution of precision agriculture, predictive models, and automated irrigation systems to food security, especially in contexts of soilless agriculture and urban agriculture. Finally, the relevance of SDG 13 (Climate Action) coincides with the studies by Ragazou et al. [90] and Corallo et al. [91], which highlight the role of emerging technologies in emissions mitigation, energy efficiency, and climate-smart agriculture.

An emerging aspect in the recent literature, also reflected in this study, is the transition from a technocentric approach to a more socio-technical vision, where adoption depends as much on technological availability as on human, institutional, and cultural factors. Gamage et al. [86] and Luque-Reyes et al. [93] emphasize that agricultural digitization faces barriers related to digital literacy, data privacy, adoption costs, and regional inequalities. Our results confirm these gaps, showing that although scientific production is global, practical adoption remains uneven and requires public policies, simplified solutions, and data governance models that strengthen the trust of farmers.

Taken together, these findings show that Smart Farming acts as a multidimensional driver of sustainability, integrating technological innovation, production efficiency, and environmental resilience. The coincidence between the patterns observed and those reported in the international literature reinforces the validity of the results and positions this study as a solid contribution to the global understanding of scientific developments in the field. Therefore, the findings of this study highlight the need for decision-makers to adopt a strategic and coordinated approach to digital transformation in agriculture. Public policies should prioritize equitable access to smart technologies, strengthen digital literacy programs for farmers, and promote interoperable and trustworthy data governance frameworks that enhance adoption and reduce technological skepticism. Investments in rural connectivity, incentives for low-cost sensorization, and support for collaborative innovation ecosystems are essential to bridge the gap between scientific advances and real-world implementation. Moreover, regulatory frameworks must evolve to address emerging challenges related to cybersecurity, data privacy, and the ethical use of artificial intelligence, ensuring that digital agriculture contributes to inclusive, resilient, and sustainable agri-food systems.

This study is subject to same limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the analysis relies exclusively on documents indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection, which, despite its high academic rigor, may underrepresent regional publications, emerging journals, or non-indexed research relevant to Smart Farming. Second, bibliometric methods provide a quantitative overview of scientific production but do not capture the qualitative depth, contextual nuances, or practical effectiveness of the technologies analyzed. Third, the rapid evolution of digital agriculture implies that publication trends may shift quickly, potentially leaving out very recent innovations not yet reflected in the database. Finally, the interpretation of keyword co-occurrence networks and thematic clusters depends on algorithmic grouping, which may oversimplify complex interdisciplinary relationships. Future studies could address these limitations by integrating multiple databases, incorporating qualitative analyses, and combining bibliometrics with case studies or field data.

Future research should deepen the understanding of sociotechnical barriers that limit the adoption of smart farming, particularly in developing regions where economic constraints and digital divides remain significant. Studies integrating mixed methods could explore how farmers perceive and interact with digital tools, while longitudinal analyses may reveal how adoption patterns evolve over time. Additionally, there is a need to advance research on interoperable architectures, energy-efficient IoT systems, and context-adapted AI models capable of operating under resource-limited conditions. Emerging areas such as blockchain-enabled traceability, digital twins for crop management, and controlled-environment agriculture also offer promising avenues for innovation. Finally, future work should examine the environmental and social impacts of digital agriculture to ensure that technological progress aligns with sustainability and equity goals.

5. Conclusions

This bibliometric study offers a comprehensive and integrative view of the evolution, structure, and scientific influence of Smart Farming, situating its development within the broader framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The results confirm an exponential expansion of the field, consistent with Price’s Law, together with a highly concentrated authorship structure aligned with Lotka’s Law, reflecting the consolidation of specialized research communities and increasingly dense international collaboration networks.

The evidence shows that Smart Farming has transitioned from an exploratory and descriptive phase to a transformative scientific domain, where digitalization, automation, artificial intelligence, and data-driven decision-making underpin a new paradigm of agricultural sustainability. The strong association with SDG 3 highlights the contribution of digital technologies to safer and healthier food systems, while the links with SDGs 2, 11, and 13 underscore the field of relevance for food security, sustainable urban development, and climate resilience. These findings align with global research trends that position Smart Farming as a cornerstone of Agriculture 4.0 and 5.0.

The high concentration of publications in Q1 journals, together with the robust citation performance and the presence of seminal works with substantial scientific influence, confirms the maturity, visibility, and global relevance of the field. However, the literature and our findings also reveal persistent asymmetries in adoption, particularly in developing regions, where economic, technical, and institutional barriers limit the effective deployment of smart technologies.

Based on these insights, this study suggests that public policies, capacity-building initiatives, and international cooperation should prioritize equitable access to digital tools, promote user-centered and context-adapted technological solutions, and strengthen data governance frameworks that enhance trust and interoperability. Addressing these challenges is essential to bridge the gap between scientific innovation and real-world implementation.

In conclusion, Smart Farming emerges as a strategic interface between data science, technological innovation, and sustainability, playing a pivotal role in the transition toward resilient, inclusive, and environmentally responsible agri-food systems. Its continued development will be fundamental for advancing global sustainability agendas and ensuring the long-term viability of food production in an increasingly complex and uncertain world.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010081/s1, SFdata-2025-10-17.xlsx.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.-B., A.V.-M. and J.M.-L.; methodology, A.V.-M.; validation, A.V.-M.; formal analysis, C.B.-B., A.V.-M. and J.M.-L.; investigation, R.C.-S. and G.S.-S.; resources, A.V.-M. and G.S.-S.; data curation, J.M.-L. and R.C.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.-B., A.V.-M., G.S.-S., R.C.-S. and J.M.-L.; writing—review and editing, C.B.-B., A.V.-M., G.S.-S., R.C.-S. and J.M.-L.; visualization, A.V.-M. and J.M.-L.; supervision, A.V.-M.; project administration, C.B.-B., A.V.-M. and J.M.-L.; funding acquisition, C.B.-B., A.V.-M., G.S.-S., R.C.-S. and J.M.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article has received partial funding for the article processing charge (APC) from: Universidad Arturo Prat (Code: APC2025), Universidad Autónoma de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad Católica de la Santísima Concepción (Code: APC2025), Universidad Central de Chile (Code: APC2025), Universidad de Las Américas (Code: APC2025), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras (Code: APC2025), and Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana (Code: APC2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kruize, J.W.; Wolfert, J.; Scholten, H.; Verdouw, C.N.; Kassahun, A.; Beulens, A.J.M. A reference architecture for farm software ecosystems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 125, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, G.; Hsu, C.-H.; Rawal, B.S.; Muthu, B.; Mavromoustakis, C.X.; Mastorakis, G. ISOF: Information scheduling and optimization framework for improving the performance of agriculture systems aided by Industry 4.0. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 3120–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramya, U.; Soundarya, C.; Shivadharshini, M.; Sneha, S. A methodical and best doable line of attack of smart agricultural commotion by means of IoT. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharma Res. 2022, 12, 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, D.Y.; Malik, A.W.; Ravana, S.D.; Rahman, A.U.; Ahmedy, I. Mapping smart farming: Addressing agricultural challenges in the data-driven era. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2024, 189, 113858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Razzaq, A.; Altaf, A.; Qadri, S.; Hussain, A.; Khan, A.N.; Sarfraz, Z. Indoor smart farming by inducing artificial climate for high value-added crops in optimal duration. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2023, 16, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Xu, K.G.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Luo, G.X.; Xing, M.; Zhong, W. Self-powered and plant-wearable hydrogel as LED power supply and sensor for promoting and monitoring plant growth in smart farming. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 129499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faid, A.; Sadik, M.; Sabir, E. An agile AI and IoT-augmented smart farming: A cost-effective cognitive weather station. Agriculture 2022, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.W.; Chen, Y.F.; Wang, D.F. Convolution network enlightened transformer for regional crop disease classification. Electronics 2022, 11, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-García, J.; Bueno-Crespo, A.; Martínez-España, R.; Cecilia, J.M. Data-driven evaluation of machine learning models for climate control in operational smart greenhouses. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2023, 15, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaghi, M.H.; Forouharfar, A. A contextualized study of the usage of the Internet of Things (IoT) in smart farming within the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT). Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.M.Z.A.; Tahir, M.N.; Raghavan, V.; Awais, M.; Hu, J.D.; Said, Y.; Othman, N.A.; Ashurov, M.; Khan, M.I. AI-enhanced IoT sensors for real-time crop monitoring: An era towards self-monitored agriculture. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Kaushik, A.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, S. Disruptive technologies in smart farming: An expanded view with sentiment analysis. Agriengineering 2022, 4, 424–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, I.; Neef, N.E.; Moghayedi, A.; Owoade, F.M.; Kapanji-Kakoma, K.; Sheena, F.; Ewon, K. Willing to be the change: Perceived drivers and barriers to participation in urban smart farming projects. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 1540–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, Ö.; Tekiner-dogan, B. Architecture design approach for IoT-based farm management information systems. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 926–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manogaran, G.; Alazab, M.; Muhammad, K.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Smart sensing-based functional control for reducing uncertainties in agricultural farm data analysis. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17469–17478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacco, M.; Berton, A.; Gotta, A.; Caviglione, L. IEEE 802.15.4 air–ground UAV communications in smart farming scenarios. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2018, 22, 1910–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arago, N.M.; Alvarez, C.; Mabale, A.G.; Legista, C.G.; Repiso, N.E.; Amado, T.M.; Jorda, R.L., Jr.; Thio-ac, A.C.; Tolentino, L.K.S.; Velasco, J.S. Smart dairy cattle farming and in-heat detection through the Internet of Things (IoT). Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2022, 14, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevavuori, P.; Narra, N.; Lipping, T. Crop yield prediction with deep convolutional neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, H.M.; Aqib, M.; Mahmood, K.; Safran, M.; Alfarhood, S.; Ashraf, I. A customized convolutional neural network-based approach for weeds identification in cotton crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1435301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sujadi, H.; Budiman, B.; Nurdiana, N.; Susandi, D.; Fitriasina, E.G.; Handayani, T. Chili plant monitoring system using YOLO object detection technology. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025, 20, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, B.; Johnson, T.; Kanjo, E. Internetless low-cost sensing system for real-time livestock monitoring. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 7500504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchemal, N.; Chollet, N.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. Intelligent IoT platform for agroecology: Testbed. J. Sens. Actuat. Netw. 2024, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harisudin, M.; Kusnandar; Riptanti, E.W.; Setyowati, N.; Khomah, I. Determinants of the Internet of Things adoption by millennial farmers. AIMS Agric. Food 2023, 8, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Nyangaresi, V.O.; Jasim, H.M.; Ma, J.C.; Hussain, M.A.; Hussien, Z.A.; Aldarwish, A.J.Y. Elliptic curve cryptography-based scheme for secure signaling and data exchanges in precision agriculture. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, O.; Saha, H.N. An IoT-based intelligent farming using CNN for early disease detection in rice paddy. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 94, 104631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Xue, J.X.; Zhang, M.Y.; Yin, J.Y.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, X.D.; Zheng, D.C.; Li, Z.Z. YOLOv5-ASFF: A multistage strawberry detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv5. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangala, A.; Das, A.K.; Chamola, V.; Korotaev, V.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Security in IoT-enabled smart agriculture: Architecture, security solutions and challenges. Clust. Comput. 2023, 26, 879–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Choi, J.; Son, S.; Kwon, D.; Park, Y. Provably secure and privacy-preserving authentication scheme for IoT-based smart farm monitoring environment. Electronics 2025, 14, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataramanan, C.; Ramalingam, S.; Manikandan, A. LWBA: Lévy-walk bat algorithm-based data prediction for precision agriculture in wireless sensor networks. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 41, 2891–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piancharoenwong, A.; Badir, Y.F. IoT smart farming adoption intention under climate change: The gain and loss perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Org. Res. Meth 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Lim, W.M.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valderrama-Zurian, J.C.; Melero-Fuentes, D.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R. Origin, characteristics, predominance and conceptual networks of eponyms in the bibliometric literature. J. Informetr. 2019, 13, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. Web of Science. 2025. Available online: https://www.webofknowledge.com (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Price, D. A general theory of bibliometric and other cumulative advantage processes. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. 1976, 27, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrov, G.; Randolph, R.; Rauch, W. New options for team research via international computer networks. Scientometrics 1979, 1, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, P. Price’s square root law: Empirical validity and relation to Lotka’s law. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulik, S. Book use as a Bradford-Zipf phenomenon. Coll. Res. Libr. 1978, 39, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Veras, L.; Gosain, A. Using Bradford’s law of scattering to identify the core journals of pediatric surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2018, 229, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. J. Wash. Acad. Sci. 1926, 16, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.; Simoes, N. Publication performance through the lens of the h-index: How can we solve the problem of the ties? Soc. Sci. Q. 2019, 100, 2495–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H. Knowledge management vs. data mining: Research trend, forecast and citation approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3160–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.U. Growth of Literature on Bradford’s Law. Investig. Bibl. Arch. Bibliotecol. Inf. 2016, 30, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E. Citation Analysis as a Tool in Journal Evaluation. Science 1972, 178, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harzing, A.W.; Alakangas, S. Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Quirós, L.; Ortega, J.L. Citation counts and inclusion of references in seven free-access scholarly databases: A comparative analysis. J. Inf. 2025, 19, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asubiaro, T.; Onaolapo, S.; Mills, D. Regional disparities in Web of Science and Scopus journal coverage. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 1469–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.; van der Heijden, M.G.A.; Wittwer, R.A.; Banerjee, S.; Walser, J.C.; Schlaeppi, K. Cropping practices manipulate abundance patterns of root and soil microbiome members paving the way to smart farming. Microbiome 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, T.M.; Brisolara, L.B.; Paulo, R.F. Survey on Coverage Path Planning with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2019, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Riaz, S.; Abid, A.; Abid, K.; Naeem, M.A. A Survey on the Role of IoT in Agriculture for the Implementation of Smart Farming. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 156237–156271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangprathub, J.; Boonnam, N.; Kajornkasirat, S.; Lekbangpong, N.; Wanichsombat, A.; Nillaor, P. IoT and agriculture data analysis for smart farm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Hakak, S.; Alazab, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Khan, W.Z.; Pham, Q.-V. Unmanned aerial vehicles in smart agriculture: Applications, requirements, and challenges. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 17608–17619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Chilvers, J. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening Responsible Innovation in an Era of Smart Farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.H.; Goudos, S. Faster R-CNN for multi-class fruit detection using a robotic vision system. Comput. Netw. 2020, 168, 107036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; De, D.; Hussain, M.I. Internet of Things (IoT) for Smart Precision Agriculture and Farming in Rural Areas. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 4890–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Beulens, A.; Wolfert, S. Digital Twins in Smart Farming. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Odelu, V.; Kumar, N.; Conti, M.; Jo, M. Design of Secure User Authenticated Key Management Protocol for Generic IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, R.; Swinton, S.M.; El Benni, N.; Walter, A. Precision Farming at the Nexus of Agricultural Production and the Environment. In Annual Reviews of Resources Economics; Rausser, G.C., Zilberman, D., Eds.; Annual Reviews: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 11, pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Khorsandroo, S.; Mittal, S. Security and privacy in smart farming: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 34564–34584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Izquierdo, M.A.; Santa, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Martínez, V.; Skarmeta, A.F. Smart farming IoT platform based on edge and cloud computing. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 177, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, I.; Chen, Z.T.; Popovic, M.; Khanna, R.; Liebisch, F.; Nieto, J.; Siegwart, R. weedNet: Dense Semantic Weed Classification Using Multispectral Images and MAV for Smart Farming. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakku, E.; Taylor, B.; Fleming, A.; Mason, C.; Fielke, S.; Sounness, C.; Thorburn, P. If they don’t tell us what they do with it, why would we trust them? Trust, transparency and benefit-sharing in Smart Farming. NJAS Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffaro, F.; Micheletti Cremasco, M.; Roccato, M.; Cavallo, E. Drivers of Farmers’ Intention to Adopt Technological Innovations in Italy: The Role of Information Sources, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease of Use. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, P.P.; Yavari, A.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Morshed, A.; Zaslavsky, A. Internet of Things Platform for Smart Farming: Experiences and Lessons Learnt. Sensors 2016, 16, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L.; Sanderson, J.; Zhang, A.R.; Jakku, E. Farmers and their data: An examination of farmers’ reluctance to share their data through the lens of the laws impacting smart farming. NJAS Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkech, M.; Hafiane, A.; Canals, R. Vine Disease Detection in UAV Multispectral Images Using Optimized Image Registration and Deep Learning Segmentation Approach. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Qiao, Y.L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.J.; Song, C.Q. CNN feature based graph convolutional network for weed and crop recognition in smart farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggi, M.K.; Jain, S. Reference evapotranspiration estimation and modeling of the Punjab Northern India using deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 156, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernecker, M.; Knierim, A.; Wurbs, A.; Kraus, T.; Borges, F. Experience versus Expectation: Farmers’ Perceptions of Smart Farming Technologies for Cropping Systems across Europe. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R.S.; Sittón-Candanedo, I.; García, Ó.; Prieto, J.; Rodríguez-González, S. An Intelligent Edge-IoT Platform for Monitoring Livestock and Crops in a Dairy Farming Scenario. Ad Hoc Netw. 2020, 98, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Sanchez-Gomez, J.; Ballesta-Viñas, J.; Cano, M.D.; Skarmeta, A.F. Performance Evaluation of LoRa Considering Scenario Conditions. Sensors 2018, 18, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozzi, M.; Cantalamessa, S.; Cogato, A.; Kayad, A.; Marinello, F. Automatic Bunch Detection in White Grape Varieties Using YOLOv3, YOLOv4, and YOLOv5 Deep Learning Algorithms. Agronomy 2022, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Huang, N.-F. Big data and AI revolution in precision agriculture: Survey and challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 110209–110222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subeesh, A.; Mehta, C.R. Automation and digitization of agriculture using artificial intelligence and internet of things. Artif. Intell. Agric. 2021, 5, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M. Automated agrifood futures: Robotics, labor and the distributive politics of digital agriculture. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 47, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; Klerkx, L.; Ayre, M.; Dela Rue, B. Managing Socio-Ethical Challenges in the Development of Smart Farming: From a Fragmented to a Comprehensive Approach for Responsible Research and Innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Medina, D.; Ramirez-delReal, T.A.; Villanueva-Vásquez, D.; Mejia-Aguirre, C. Trends on Advanced Information and Communication Technologies for Improving Agricultural Productivities: A Bibliometric Analysis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sott, M.K.; Nascimento, L.d.S.; Foguesatto, C.R.; Furstenau, L.B.; Faccin, K.; Zawislak, P.A.; Mellado, B.; Kong, J.D.; Bragazzi, N.L. A Bibliometric Network Analysis of Recent Publications on Digital Agriculture to Depict Strategic Themes and Evolution Structure. Sensors 2021, 21, 7889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, M.E.; Menegoli, M.; Corallo, A. Agriculture digitalization: A global examination based on bibliometric analysis. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 1330–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Khan, H.U.; Nisar, W.; Farooq, M.; Rehman, S.-U. Blockchain and Internet of Things: A Bibliometric Study. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2020, 81, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A. Bibliometric Review of Digital Transformation in Agriculture: Innovations, Trends and Sustainable Futures. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2025; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.R.; Kumar, S.; Rani, R.; Agrawal, P.; Pippal, S.K. A Bibliometric and Word Cloud Analysis on the Role of the Internet of Things in Agricultural Plant Disease Detection. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Subasinghe, S.; Gamage, J.; Guruge, C.; Senaratne, S.; Randika, T.; Rathnayake, C.; Hameed, Z.; Madhujith, T.; et al. Advancing Sustainability: The Impact of Emerging Technologies in Agriculture. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 40, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vázquez, J.P.; Torres, R.S.; Pérez-Peréz, D.B. Scientometric Analysis of the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture. J. Scientometr. Res. 2021, 10, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushartadi, T.; Mulyono, A.E.; Al Hamdi, A.H.; Rizki, M.A.; Sadat Faidar, M.A.; Harsanto, W.D.; Suryanegara, M.; Asvial, M. Theme Mapping and Bibliometric Analysis of Two Decades of Smart Farming. Information 2023, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeh, O.O.; Nwulu, N.I. Improving Traceability and Sustainability in the Agri-Food Industry through Blockchain Technology: A Bibliometric Approach, Benefits and Challenges. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazou, K.; Garefalakis, A.; Zafeiriou, E.; Passas, I. Agriculture 5.0: A New Strategic Management Mode for a Cut Cost and an Energy Efficient Agriculture Sector. Energies 2022, 15, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corallo, A.; Latino, M.E.; Menegoli, M.; Signore, F. Digital Technologies for Sustainable Development of Agri-Food: Implementation Guidelines Toward Industry 5.0. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 10699–10715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Gupta, D.; Tharewal, S.; Goyal, D.; Kaur Sandhu, J.; Kaur, M.; Ali Alzubi, A.; Mutared Alanazi, J. Internet of things-based smart precision farming in soilless agriculture: Opportunities and challenges for global food security. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 34238–34268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque-Reyes, J.R.; Zidi, A.; Peña-Acevedo, A.; Gallardo-Cobos, R. Assessing Agri-Food Digitalization: Insights from Bibliometric and Survey Analysis in Andalusia. World 2025, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.