Abstract

Wheat dwarf virus (WDV) is a major constraint to global wheat production, causing severe yield losses and economic disruption. Understanding the molecular basis of wheat–WDV interactions is essential for developing resistant cultivars. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), are key regulators of gene expression and defence. This study identified ncRNAs involved in wheat responses to WDV, including host lncRNAs, miRNAs, and viral small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting WDV genomic regions. High-throughput sequencing revealed extensive ncRNA reprogramming under WDV infection. A total of 437 differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) and 58 miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) were detected. Resistant genotypes displayed more DElncRNAs (204 in Svitava; 163 in Fengyou 3) than the susceptible Akteur (141). In Akteur, 66.7% of DElncRNAs were downregulated, whereas in Svitava, 56.9% were upregulated. Akteur also exhibited more DEmiRNAs (28) than resistant genotypes (15), with predominant downregulation. A co-expression network analysis revealed 391 significant DElncRNA–mRNA interactions mediated by 16 miRNAs. The lncRNA XLOC_058282 was linked to 298 transcripts in resistant genotypes, suggesting a central role in the host defence. Functional annotation showed enrichment in signalling, metabolic, and defence-related pathways. Small RNA profiling identified 1166 differentially expressed sRNAs targeting WDV, including conserved hotspots and 408 genotype-specific sites in Akteur versus Fengyou 3. Infected plants displayed longer sRNAs, a sense-strand bias, and a 5′ uridine preference, but lacked typical 21–24 nt phasing. These findings highlight the central roles of ncRNAs in orchestrating wheat antiviral defence and provide a molecular framework for breeding virus-resistant wheat.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in high-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) have revealed that a substantial proportion of the plant (eukaryotic) genome is transcribed into non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which fulfil diverse and important regulatory roles. Indeed, over 90% of eukaryotic genome sequences are transcribed into RNA, the vast majority of which comprise non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [1,2]. These ncRNAs are generally classified by their size, origin, and function into small RNAs (sRNAs, 18–30 nucleotides), medium-length ncRNAs (31–200 nucleotides), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, >200 nucleotides) [3,4]. In plants, the two most prominent classes of sRNAs are microRNAs (miRNAs) and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), which differ in their biogenesis and modes of action. miRNAs, typically 21–24 nucleotides in length, are derived from endogenous transcripts that fold into imperfectly base-paired hairpin precursors, whereas siRNAs are generated from long, fully complementary double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs), often synthesised de novo by RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs) [5].

Viruses, whether DNA- or RNA-based, also generate non-coding RNAs that mimic host ncRNAs in both structure and function. In eukaryotic cells, viral non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) interact with host proteins to modulate RNA stability and gene expression, influencing viral infection dynamics [6]. Specifically, WDV ncRNAs in Triticum aestivum likely target host RNA-binding proteins and defence pathway components to regulate viral replication, persistence, and immune evasion. Thus, viral ncRNAs serve dual functions by controlling the viral life cycle while simultaneously influencing the antiviral defence mechanisms of the host [4,7]. In addition, host-derived ncRNAs play crucial roles in RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), contributing to the epigenetic silencing of viral DNA, particularly in single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) viruses [8]. This transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) mechanism targets viral chromatin, formed by host histone-associated double-stranded DNA replication intermediates. Given that geminiviruses lack their own DNA polymerases, they rely entirely on host replication and transcriptional machineries. Their circular single-stranded DNA genomes are converted into double-stranded DNA forms that become chromatinised through association with host histones and chromatin-associated proteins. This chromatinisation not only enables recognition by the host replication complex, but also subjects the viral genome to host epigenetic regulatory mechanisms, including histone modifications and DNA methylation, which can influence both the viral gene expression and replication efficiency [9,10].

Wheat dwarf virus (WDV) represents a significant challenge to global wheat production, resulting in substantial yield losses of up to 100% and economic disruption in Europe, North Africa, and Asia, underscoring its relevance for farmers and emphasising the necessity for effective management strategies [11]. WDV, a member of the genus Mastervirus within the family Geminiviridae, possesses a circular, single-stranded DNA genome [12,13]. It encodes two replication-associated proteins: Rep and RepA [14]. Rep is a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein essential for rolling-circle replication and plays a role in regulating viral gene expression [15]. RepA promotes the transcription of viral sense genes, enhances the expression of the movement protein (MP) and coat protein (CP), and is thought to negatively regulate viral DNA replication [16]. Furthermore, Rep interacts with host cell cycle regulators and modulates host gene expression [13,17]. Both Rep and RepA have also been identified as suppressors of RNA silencing [18]. Nevertheless, while ncRNAs contribute to viral replication and silencing in some plant–virus interactions, including genimiviruses [19,20], their specific roles in the WDV infection of Triticum aestivum, particularly in modulating viral replication and RNA silencing pathways, remain insufficiently characterised [21,22].

The present study aimed to identify novel ncRNAs associated with resistance to WDV, both from the virus itself and host wheat plants, building upon our recent transcriptomic analysis of three wheat genotypes exhibiting contrasting resistance levels, specifically: the susceptible genotype, Akteur, and the two resistant genotypes, Fengyou 3 and Svitava [23]. This work further investigates the role of ncRNAs in the regulatory networks underpinning the RNA-directed defence mechanisms mounted by wheat in response to WDV infection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Growth and WDV Inoculation

Eleven seeds of each genotype (one seed per pot) under study were sown individually into 0.23 L plastic pots containing a soil mixture composed of 60% luvic chernozem and 40% arenic regosol. Prior to sowing, 0.9 g of NPK fertiliser (12.4% N, 11.4% P2O5, and 18% K2O) and 0.7 g of calcium nitrate (15.5% N) were incorporated into the soil for each plant. For each genotype, a total of six plants were used for the experiment: 3 WDV-inoculated and 3 mock-inoculated controls (Supplementary Figure S1). The infection efficiency and viral titer variability across replicates were previously characterised in Sharaf et al. (2023) [23]. All inoculated plants were confirmed to be successfully infected via qPCR-based virus titer assays, with minimal variability in viral titers within each genotype (standard deviations reported in Figure 2 of ref. (Sharaf et al., 2023) [23]). These data provide a robust foundation for the RNA-seq-based analysis of non-coding RNAs in the current study. The plants were cultivated in a greenhouse under controlled conditions: 15 °C during a 14-h photoperiod and 7 °C during 10 h of darkness, with this temperature regime specifically chosen to optimise the transmission efficiency of the vector Psammotettix alienus, which performs best at cooler temperatures, while still allowing consistent wheat development and the expression of resistance phenotypes. Near-100% infection success with low viral titer variability was achieved across all genotypes, as reported in Sharaf et al. (2023) [23]. The WDV-inoculated and mock-inoculated plants were cultivated in separate, physically separated greenhouse compartments to avoid cross-contamination. Wheat plants of the cultivars Akteur, Fengyou 3, and Svitava were each isolated using small insect-proof cages and individually inoculated with three viruliferous P. alienus leafhoppers. The insects, along with the WDV wheat strain (accession number: FJ546188, [24]), were sourced from the virus collection maintained at the Czech Agrifood Research Centre. Inoculation feeding commenced at growth stage BBCH 12–13 (2 to 3 leaves unfolded) and continued for 8 days, after which both the leafhoppers and the isolator cages were removed. On the 99th day of cultivation, when WDV symptoms were clearly visible and genotype-specific differences in response to infection were apparent, plants were carefully removed from the soil. Roots were gently washed and excess surface water was blotted using paper towels. Plants were weighed in their fresh state. The whole-plant samples were then stored at −80 °C until further laboratory analysis.

2.2. Isolation of Small RNAs, Library Preparation, and Deep Sequencing

Seventy-two individual samples comprising 3 wheat genotypes: Akteur, Fengyou 3, Svitava; 2 treatments: non-inoculated, and WDV-infected; 3 biological replicates were prepared individually for both RNA-seq (published in Sharaf et al., 2023 [23]) and sRNA sequencing (newly generated in this study); the experimental design is summarised in Supplementary Figure S1. RNA extraction was carried out using the single-step method [25]. The aqueous phase (500 μL) was mixed with 3.0 μL of GlycoBlue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) prior to RNA precipitation with 625 μL of ethanol and 250 μL of 0.8 M sodium citrate/1.2 M sodium chloride. The RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA). The RNA integrity was initially assessed via agarose gel electrophoresis using 3.0 μg of the total RNA per sample. Subsequently, RNA samples were diluted and analysed using the Agilent Bioanalyser 6000 system with RNA 6000 Nano Chips (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), yielding RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) ranging from 8.3 to 9.2. For the analysis of small RNAs, 5.0 μg of the total RNA was mixed with 2× Loading Ambion Buffer II (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), denatured for 2 min at 90 °C, and resolved on a 15% polyacrylamide/7 M urea/1× TBE gel at 300 V. Small RNAs (18–30 nucleotides) and ligation/PCR products were visualised on SYBR Gold-stained gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using 10/60 and 20/100 bp DNA ladders (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) as the size references. RNA and PCR products were eluted from the polyacrylamide gels into 300 μL of EBR buffer (50 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 M ammonium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS) for 10–16 h at 20–25 °C (300 rpm). Following phenol/chloroform and chloroform extraction, the aqueous phase was supplemented with 2.0 μL of GlycoBlue (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 900 μL of 96% ethanol, cooled at −20 °C for 2 h, and centrifuged (25 min at 16,000× g, 4 °C). The RNA pellet was washed twice with 75% ethanol and dissolved in 6.0 μL of RNase-free water.

Small RNA concentrations were quantified using the Qubit microRNA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A total of 72 small RNA libraries were prepared using the Small RNA-Seq Library Prep Kit (Lexogen, Vienna, Austria), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were generated from three wheat genotypes (Akteur, Fengyou 3, and Svitava) under two treatments (WDV-infected and non-inoculated), with three biological replicates per condition, each sequenced in four technical replicates (Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S1). The cDNA concentration of each small RNA library was measured with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Library sequencing was performed on the Illumina NextSeq 550 platform in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), at the Laboratory of Genomics and Bioinformatics, Institute of Molecular Genetics, Czech Academy of Sciences. For each condition, at least 2.9 million raw reads were generated. After quality control and cleaning, the number of reads was not significantly reduced. Small RNAs of 18–25 nucleotides in length were mapped to obtain a non-redundant set of sequences. This dataset was further enriched for wheat-specific sRNAs by mapping the non-redundant reads to the wheat reference genome. After quality filtering, we obtained an average of 3.6 million clean reads per library (range: 2.9–4.6 million), of which non-redundant reads (18–25 nucleotides) were mapped to the wheat reference genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0, retrieved on 20 March 2025), achieving an average alignment rate of 87.6% (Supplementary Table S2). This dataset was enriched for wheat-specific sRNAs, enabling the downstream analysis of virus-responsive ncRNAs.

2.3. Identification of lncRNAs and miRNAs

The transcriptomic data from our previous study [23] were analysed to identify long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) through a four-step pipeline: (i) The Cuffmerge tool, part of the Cufflinks Support Package v2.2.1, was used to merge all assembled transcripts. Transcripts with fewer than three reads in coverage retained potentially lowly expressed lncRNAs, which are often biologically relevant in plants despite low expression levels. This low threshold was chosen to maximise sensitivity, with subsequent steps ensuring specificity. (ii) Transcripts shorter than 200 base pairs were subsequently removed to eliminate small RNAs. (iii) The remaining transcripts were compared with annotated wheat mRNAs available in the Ensembl Plants database (http://plants.ensembl.org/Triticum_aestivum/Info/Index, accessed on 20 April 2024) using the Cuffcompare tool (Cufflinks Support Package v2.2.1). Transcripts overlapping with known wheat mRNAs were discarded. (iv) Transcripts with a potential coding capacity were eliminated using three tools: CPC (Coding Potential Calculator) v2 (default), CANTATAdb v2, and PFAM protein domain analysis v33.1 [26,27,28], ensuring only high-confidence lncRNAs were retained. The transcripts remaining after this filtering process were classified as lncRNAs. The same lncRNA identification pipeline was applied consistently to the current WDV wheat dataset and four public cereal RNA-seq datasets. The latter served as training data to validate the sensitivity and specificity prior to the analysis of the infection responses.

Raw small RNA sequencing data were processed using the Oasis 2 pipeline (https://oasis.ims.bio/, accessed on 20 October 2024). In this step, adapter dimers, low-quality and low-complexity reads, sequences from common RNA families (rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA), and repetitive elements were removed [29]. Following stringent quality control, unique sequences of 18–25 nucleotides in length were aligned to specific precursors in miRBase v22.1 using BLAST v2.14.1, in order to identify both known miRNAs and novel 3p- and 5p-derived miRNAs. The alignment allowed for length variations at the 3′ and 5′ ends, as well as internal mismatches.

2.4. Genotype-Specific Antiviral Responses

Host-derived reads were filtered using Bowtie2 v2.4.5 by aligning them to the wheat reference genome from the Ensembl Plants database (http://plants.ensembl.org, IWGSC RefSeq v1.0, retrieved on 20 March 2025), retaining only unmapped reads. These unmapped reads were subsequently aligned to the WDV genome (accession number: FJ546188.1) using Bowtie v1.3.1 (-v 0 -k 1 --best --strata). Genotype-specific WDV genomes (Akteur_WDV, Fengyou 3_WDV, Svitava_WDV) were reconstructed using SPAdes v3.15.5 with default parameters and annotated with Prokka v1.14.6. sRNA counts which were aggregated using the Rsamtools package in R v4.3.0, generating a counts matrix comprising 2735 genomic positions derived from mapping files. Differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 v1.40.2, with positions filtered out if they had fewer than five counts in fewer than three samples. Differential expression was determined using Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction, with significant positions defined as those with an adjusted p-value (padj < 0.05) and log2 fold change > 1. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on variance-stabilised counts, and visualisation was carried out using the ggplot2 package. Hotspot regions were identified from infected samples and overlaid with statistically significant positions (padj < 0.05, log2 fold change > 1). Size distribution and strand polarity of sRNAs were determined from sequencing and mapping files using the ShortRead and Rsamtools packages, respectively. The 5′-nucleotide preference was analysed using the Biostrings package and mapping files from infected samples. Motif discovery within hotspot regions was performed using MEME v5.5.7 (-dna -nmotifs 3 -minw 6 -maxw 12 -objfun classic), and correlations with viral genomic features were assessed using the GenomicRanges v1.62.1 package. Phasing was evaluated by calculating the distances between the start sites of sRNAs in twelve infected samples per genotype.

2.5. Differential Expression Analysis of Noncoding RNAs

The quantification of the transcript abundances of ncRNAs was conducted using Cuffdiff v2.2.1 (--library-norm-method geometric --dispersion-method per-condition) [30], thereby generating raw read counts for differential expression analysis. The DESeq2 and edgeR packages in R v4.3.0 [31,32] were applied directly to raw count matrices (no prior normalisation). The analysis was conducted using the median of ratios normalisation method implemented in the DESeq2 software, while the TMM normalisation method was used internally by edgeR. Both packages applied Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction to control for multiple testing instances, with differentially expressed non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) defined as those with an adjusted p-value (padj < 0.05) and log2 fold change > 1. Only significant transcripts in both tools (FDR < 0.05, log2FC > 1) were reported. The TPM (Transcript Per Million) values were calculated separately post-analysis for the purpose of visualisation (e.g., heatmaps) and co-expression analysis, and they were not utilised as input to DE (Differential Expression) models. Genotype-specific DElncRNAs and DEmiRNAs were further subjected to statistical enrichment testing and Gene Ontology (GO) analysis using the PANTHER classification system v19 (http://www.pantherdb.org, accessed on 25 February 2025) [33].

2.6. Prediction of ncRNA–mRNA Regulatory Network

Genes located within a 100 kb window upstream and downstream of each DElncRNA were identified as potential cis-regulated targets, following standard practices for lncRNA target prediction in plants [34]. The prediction of microRNA–target interactions was conducted utilising the psRNATarget (2017 release) [35] Schema V2, Expectation ≤ 3.0, UPE ≤ 25, seed 2–13 nt, and HSP 19–20 nt. The predicted pairs were filtered using two different methods. Firstly, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to calculate the strength of the relationship between the pairs, with a value of r > 0.8 and a p-value of < 0.05 indicating a strong correlation. Secondly, a hypergeometric enrichment test was performed, with a Bonferroni correction applied to the p-value to ensure the accuracy of the results. The cut-off value for this test was set at p ≤ 0.05.

2.7. RT-qPCR Analysis

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis was performed using three biological and four technical replicates of the total RNA. First-strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using 1.0 µg of the total RNA, RevertAid Reverse Transcriptase (200 U/µL), and oligo(dT)18 primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). RT-qPCR was conducted using the LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and the LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) in 12 µL reaction volumes. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, followed by 55 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 10 s. Fluorescence detection was performed through melting curve analysis from 60 °C to 97 °C. Specific primers for RT-qPCR were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST (RRID:SCR_003095) (see Supplementary Table S1). Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the method [36], with TubB (Beta-Tubulin B) and Gapdh (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) as reference genes [37,38]. The selection of the reference genes TubB and Gapdh was informed by prior validation under viral infection using geNorm v3.4 and NormFinder v21 [37], thereby ensuring stable expression across treatments.

3. Results

3.1. Sequencing Output and Assembly

RNA was extracted from 18 biological samples, each composed of three pooled plants, representing three wheat cultivars, Akteur (susceptible), Fengyou (resistant), and Svitava (resistant), under two treatments (non-inoculated and WDV-infected). Each biological sample was sequenced in four technical replicates, generating 72 sRNA-seq libraries in total. These libraries underwent deep sequencing using the Illumina Genome Analyser for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), previously published in [23], and small RNA (sRNA) sequencing, newly generated in this study (Supplementary Figure S1 for the experimental design). Small RNAs were sequenced from all 72 individually constructed libraries (without pooling), generating a total of 259 million raw reads on the Illumina platform (Supplementary Table S2). Small RNA sequencing yielded high-quality libraries, with an average of 3.6 million clean reads per sample mapping to the wheat reference genome (IWGSC RefSeq v1.0, retrieved on 20 March 2025). Additionally, based on lncRNA characteristics and a four-step filtering process, a total of 1708 high-confidence lncRNAs were identified. These lncRNAs were co-expressed with 1089 coding mRNAs, as determined by Pearson’s correlation analysis (Section 3.2.1), with associations reflecting adjacent (upstream or downstream) relationships. These results provide a high-quality, deeply sequenced dataset with robust replication, enabling the reliable detection of genotype- and infection-specific ncRNA responses.

3.2. Differential Expression Analysis

The differential expression analysis was performed using all 72 sequencing libraries (raw counts). For the purpose of visualisation (e.g., heatmaps, PCA), expression values were averaged across the four technical replicates per biological sample to improve the clarity; however, all statistical analyses were conducted using the full replicate set.

3.2.1. lncRNA

The number of reads corresponding to lncRNAs was quantified using a normalised TPM matrix to enable comparisons of lncRNA expression levels. Differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) were defined as those with an adjusted p-value (padj < 0.05, using Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction) and a log2 (fold change) > 1, indicating significant enrichment or depletion in WDV-infected genotypes relative to non-inoculated controls using DESeq2 and edgeR [31,32] (Supplementary Table S3). The hierarchical clustering of DElncRNAs was performed using log10TPM values from the 72 sequencing libraries to assess the overall expression patterns. In the resulting heatmaps, yellow bands indicate upregulated lncRNAs, while purple bands indicate downregulated lncRNAs (Figure 1A,B). Some genotype/treatment combinations formed separate clusters, reflecting natural biological variability among the three biological replicates; however, these clusters showed consistent expression levels, ensuring the robustness of the 437 identified DElncRNAs (141 in Akteur, 163 in Fengyou, 204 in Svitava). The use of three biological replicates (each with four technical replicates) and the statistical rigor of DESeq2 and edgeR with FDR correction accounted for this variability, maintaining significance.

Figure 1.

Summary of lncRNAs differential expression in WDV-infected and non-inoculated wheat genotypes. (A) Heatmap showing the expression levels of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and (B) the clustering of differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs) in WDV-infected and non-inoculated genotypes (Akteur, Fengyou 3, Svitava). (C) Bar chart showing the number of DElncRNAs in each genotype after WDV infection. (D) Venn diagram showing how the DElncRNAs overlap among the three genotypes after WDV infection.

The number of DElncRNAs identified in the genotypes Akteur, Fengyou 3, and Svitava were 141, 163, and 204, respectively. Among these, 94 (66.7%) DElncRNAs in Akteur, 89 (54.6%) in Fengyou 3, and 88 (43.1%) in Svitava were downregulated, while 47 (33.3%), 74 (45.4%), and 116 (56.9%) were upregulated, respectively (Figure 1C). Overall, lncRNA expression in response to WDV infection was lower in the susceptible genotype Akteur compared to the resistant genotype Svitava. Nevertheless, the total number of DElncRNAs detected in Akteur was lower than in Svitava (Figure 1A–C), a pattern that contrasts with transcript expression profiles reported in our previous study [23]. Moreover, we identified 67, 82, and 104 genotype-specific DElncRNAs unique to Akteur Fengyou 3 and Svitava, respectively, and 104 in Svitava in response to viral infection (Figure 1D and Supplementary Table S3). Notably, the resistant genotypes Fengyou 3 and Svitava shared 47 DElncRNAs, while 13 DElncRNAs were common to all three genotypes. These results indicate that resistant genotypes mount a broader and more activation-biased lncRNA response, suggesting enhanced regulatory reprogramming to counter WDV infection.

Furthermore, Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were examined between lncRNAs and their neighbouring protein-coding genes (within 100 kilobases). A total of 1245 significant correlations were identified using a threshold of r > 0.7 and p < 0.05, including 933 positive correlations (r > 0.7) involving 659 lncRNAs and 596 mRNAs, and 312 negative correlations (r < −0.7) involving 7 lncRNAs and 12 mRNAs. It is noteworthy that five lncRNAs exhibited both positive and negative correlations with different neighbours, resulting in 661 unique co-expressed lncRNAs (Supplementary Table S4). Of these, 363 DElncRNAs responsive to WDV were co-expressed with 374 neighbouring protein-coding genes (Supplementary Table S4). This finding supports the hypothesis that DElncRNAs act locally as cis-regulators of defence, metabolism, and stress genes during WDV infection. To investigate the potential biological roles of DElncRNAs, we performed functional enrichment analysis using the PANTHER Classification System v19.0 on the 374 protein-coding genes co-expressed with 363 DElncRNAs in response to WDV in Akteur, Svitava, and Fengyou 3 (Supplementary Table S4). Gene Ontology (GO) categories were summarised using Revigo v1.8.2 [39]. Significant enrichment (p < 0.05) was observed in the biological process and cellular component categories for all genotypes, though not in the molecular function category. The ten most significantly enriched GO terms in each category are presented in Supplementary Figure S1. Within the molecular function category, genes across all three genotypes were associated with conserved activities such as UFM1-conjugating enzyme activity (GO:0061657), 2-phytyl-1,4-naphthoquinone methyltransferase activity (GO:0052624), and urease activity (GO:0009039) (Supplementary Figure S2). In Akteur, DElncRNAs were linked to genes with NAD+ synthase (glutamine-hydrolysing) activity (GO:0003952), while in Fengyou 3 they were linked to genes involved in L-amino acid oxidase activity (GO:0001716) (Supplementary Figure S2).

GO enrichment analysis also revealed that DElncRNA-associated genes were involved in conserved biological processes such as ubiquinone biosynthesis (GO:0032194), protein ufmylation (GO:0071569), reticulophagy (GO:0061709), phylloquinone metabolism (GO:0042374), and vitamin K metabolism (GO:0042373) across all three genotypes. Notably, genes involved in pyridine nucleotide biosynthesis (GO:0019363) were enriched in Akteur and Svitava, while fat-soluble vitamin biosynthesis (GO:0042362) was specifically enriched in Fengyou (Supplementary Figure S2). In the cellular component category, DElncRNA-associated genes were enriched for the proton-transporting ATP synthase complex (GO:0045259), respiratory chain complex (GO:0098803), cation channel complex (GO:0034703), and transmembrane transporter complex (GO:1902495) across all genotypes (Supplementary Figure S2). Interestingly, enrichment for the photosystem I component (GO:0009522) was observed in Akteur, whereas ribosomal enrichment (GO:0005840) was specific to Fengyou 3 (Supplementary Figure S2). These enrichments suggest that lncRNAs orchestrate energy redirection and metabolic reprogramming to support antiviral defence, particularly in resistant genotypes.

3.2.2. miRNA

The yellow bands indicate upregulated miRNAs, while the purple bands correspond to downregulated miRNAs (Figure 2A,B). The systematic analysis of miRNA expression profiles identified 575, 548, and 623 differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) in Akteur, Fengyou 3, and Svitava, respectively, with significant differential expression defined as an adjusted p-value (padj < 0.05, using Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction) and log2 fold change > 1. The total number of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) meeting the criteria of padj < 0.05 and log2 fold change > 1 is summarised in Supplementary Table S5. Specifically, 28 DEmiRNAs were detected in Akteur (4 upregulated, 24 downregulated), 15 in Fengyou (5 upregulated, 10 downregulated), and 15 in Svitava (5 upregulated, 10 downregulated). Hierarchical clustering showed that some genotype/treatment combinations formed separate clusters, likely due to biological variability among the three biological replicates (Figure 2A,B). However, consistent expression levels within these clusters, combined with the statistical power of four replicates and the robust negative binomial models of DESeq2 and edgeR with FDR correction, ensured the reliability of the identified DEmiRNAs.

Figure 2.

Summary of microRNAs (miRNAs) differential expression in WDV-infected and non-inoculated wheat genotypes. (A) Heatmap showing the expression levels of microRNAs (miRNAs) and (B) the clustering of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEmiRNAs) in WDV-infected and non-inoculated genotypes (Akteur, Fengyou, Svitava). (C) Bar chart showing the number of DEmiRNAs in each genotype after WDV infection. (D) Venn diagram showing the common DEmiRNAs among the three genotypes after WDV infection.

Overall, the expression analysis indicates that the susceptible genotype Akteur exhibits a stronger tendency toward miRNA downregulation following WDV infection, with 24 downregulated and 4 upregulated DEmiRNAs, compared to the resistant.

Genotype Svitava, which shows 10 downregulated and 5 upregulated DEmiRNAs (Supplementary Table S5 and Figure 2C). Interestingly, this trend contrasts with that of lncRNA expression, where Akteur exhibited a higher number of DElncRNAs than Svitava (Figure 1A–C). Thus, miRNA and lncRNA expression patterns showed opposing trends (Figure 1 and Figure 2). In addition, we identified 17 and 6 genotype-specific DEmiRNAs in Akteur and Fengyou, respectively, while only 7 were specific to Svitava (Figure 2D). Notably, no DEmiRNAs were shared exclusively between the resistant genotypes (Fengyou 3 and Svitava), whereas five DEmiRNAs were common to all three genotypes (Figure 2D). This finding indicates that WDV suppresses host miRNAs in the susceptible genotype, while resistant genotypes maintain or activate miRNAs to restrict viral exploitation. To gain insight into the functional significance of the identified DEmiRNAs, we queried the microRNA database miRBase (https://www.mirbase.org, accessed on 25 February 2025). All 58 DEmiRNAs were classified as mature miRNAs, and most were previously annotated in miRBase as experimentally detected in wheat under biotic or abiotic stress conditions, such as viral infections or environmental stresses (Supplementary Table S5). While miRBase confirms their expression under stress, the specific differential expression patterns observed in our study may differ from prior reports due to variations in experimental conditions, genotypes, or stress types, highlighting the unique context of WDV infection in our analysis. Only four DEmiRNAs (6.9%) lacked experimental validation: tae-miR159b-a in the Akteur genotype, tae-miR-14-5p-f (insect-derived, likely from the WDV vector Psammotettix alienus) in Fengyou 3, and tae-novel-miR025-s in Svitava following WDV infection. Moreover, ten of the identified DEmiRNAs (23.26%) have been previously reported in Triticum aestivum (Supplementary Table S5). Among the 43 identified DEmiRNAs, 26 (60.46%) were previously uncharacterised, while 17 (39.53%) exhibited a sequence identity with known microRNAs listed in miRBase (https://www.mirbase.org/, accessed on 25 February 2025) (Supplemental Table S5). These findings reveal a core set of stress-responsive miRNAs, with novel DEmiRNAs potentially representing WDV-specific regulatory innovations.

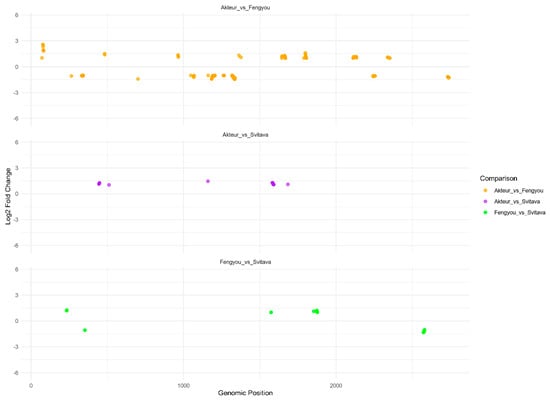

3.3. Genotype-Specific Antiviral Small RNA Responses

The principal component analysis (PCA) revealed that infected samples clustered by genotype (Akteur, Fengyou 3, Svitava) along the negative PC1 axis, while non-infected samples were more dispersed along the positive axis. This distribution indicates genotype-specific small RNA responses, likely associated with antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) pathways, to WDV infection (Figure 3). Small RNA (sRNA) sequencing identified 1166 viral genomic positions on the assembled WDV genome (~2.75 kb), based on the reference strain [24] with the significant enrichment of viral small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in WDV-inoculated wheat genotypes (Akteur, Fengyou 3, Svitava) compared to non-inoculated samples, where no viral siRNAs were detected (padj < 0.05, using Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction, log2 fold change > 1; DESeq2 and edgeR; Table S6). To rule out background contamination in non-inoculated samples, plants were grown in separate insect-proof cages, RNA extraction and library preparation were performed under sterile conditions, and sequencing reads were aligned to the WDV genome, confirming no significant alignment (fewer than five reads per sample). These WDV genomic regions, targeted by viral siRNAs, overlapped significantly with small RNA (sRNA) hotspots identified across all three genotypes (Supplementary Figure S3), indicating a robust antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) response in inoculated plants. Pairwise comparisons among the infected genotypes revealed 408 significantly different viral genomic positions between Akteur and Fengyou 3, 162 between Akteur and Svitava, and 193 between Fengyou 3 and Svitava, suggesting genotype-specific targeting patterns (Figure 4). This finding supports the hypothesis that distinct antiviral RNAi strategies exist, with resistant genotypes mounting more precise and intense vsiRNA responses. Small RNA (sRNA) sequencing revealed that differentially targeted positions in the WDV genome, defined as regions with significant sRNA read coverage (p < 0.05, log2 fold change > 1), overlapped with sRNA hotspots (regions with a high sRNA read density, identified using Rsamtools package). These hotspots were consistently detected across WDV genomes reassembled from sRNA reads for all three infected wheat genotypes (Akteur, Fengyou 3, Svitava), indicating conserved antiviral RNAi targeting (Supplementary Figure S3). The analysis of sRNA size distributions revealed a slight shift toward longer sRNAs in WDV-infected samples compared to non-infected controls, with mean read lengths of 22.4 nt (Akteur), 21.6 nt (Fengyou 3), and 21.4 nt (Svitava) in infected samples versus 21.8 nt (Akteur), 21.6 nt (Fengyou 3), and 21.2 nt (Svitava) in the controls (Supplementary Table S6). This shift was driven by an increased proportion of 22 nt sRNAs, likely virus-derived small interfering RNAs (vsiRNAs), in infected samples, consistent with antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) responses. A shared modal sRNA length of 18 nt, likely representing non-RNAi fragments (e.g., tRNA-derived), was observed across all samples (Supplementary Table S6). Strand polarity analysis revealed a moderate sense strand bias in infected genotypes (Akteur: 58.4%, Fengyou 3: 57.2%, Svitava: 57.2%) compared to the minimal strand bias in non-infected samples (Supplementary Table S7). In addition, infected samples showed a strong preference for uracil (T) at the 5′ end of sRNAs, particularly in Fengyou 3 (36.8%), followed by Akteur (29.0%) and Svitava (28.5%) (Supplementary Table S8). The hallmarks of DCL2/4-mediated primary vsiRNA production in response to WDV, including the 22 nt shift, 5′ U bias, and strand asymmetry, serve as critical indicators of activation. Motif discovery analysis, performed using MEME v5.4.1 on WDV genome hotspot regions with high sRNA read coverage, identified three significantly enriched sequence motifs per wheat genotype (Supplementary Table S7). In Akteur, the top motif was AACSYTRYWACT (E-value = 6.4), while Fengyou and Svitava showed AYCGTGRACSYY (E-value = 3.3) and CTTGTTACTGAT (E-value = 1.7), respectively. These motifs overlapped significantly with Rep/RepA CDS (positions 171–2510), suggesting sRNA-mediated targeting via antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) or RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) (Supplementary Figure S3). This finding suggests that resistant genotypes evolve structured, G/C-rich motifs to enhance Dicer recognition and the RdDM-mediated silencing of viral replication genes. A phasing analysis of sRNAs mapping to the WDV genome revealed no typical 21–24 nt periodicity, with the most common spacing being 0 nt (e.g., Akteur: 661,952 sense, 470,942 antisense reads; see also Supplementary Table S7). This phenomenon may be attributed to the WDV-mediated suppression of host RDR6 by Rep and RepA, which have been shown to inhibit secondary siRNA production. Alternatively, it may be explained by a limited sequencing depth, as evidenced by the observation of this reduced detection of low-abundance phased siRNAs. These factors suggest that primary vsiRNA-mediated RNAi is the dominant antiviral mechanism.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of non-host small RNA expression profiles in T. aestivum genotypes under WDV infection. PCA was performed on normalised non-host small RNA expression data from three T. aestivum genotypes: Akteur (susceptible), Fengyou 3 (moderately resistant), and Svitava (resistant), under two conditions (WDV-infected and non-infected controls). The analysis reveals genotype- and treatment-specific clustering patterns, highlighting variation in small RNA responses to WDV infection. PC1: 78.4%, PC2: 12.1% (total 90.5%) of variance. PC3 and PC4 (<5%) showed no treatment/genotype separation.

Figure 4.

Genotype-specific RNAi targeting of WDV genomic locations in infected Triticum aestivum genotypes. Scatter plots display log2 fold changes in viral small interfering RNA (siRNA) coverage across reassembled Wheat dwarf virus (WDV) genome regions (~2.75 kb, based on the reference strain; Sharaf et al., 2023 [23]) from pairwise comparisons between WDV-inoculated T. aestivum genotypes: Akteur vs. Fengyou 3, Akteur vs. Svitava, and Fengyou 3 vs. Svitava. Each point represents a WDV genomic position with differential siRNA targeting between genotypes, revealing distinct, genotype-specific antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) responses.

3.3.1. Genotype-Specific Targeting of Viral Genes and Regulatory Elements

The 1166 differentially expressed viral genomic positions (padj < 0.05, log2FC > 1) were mapped to the WDV genome (FJ546188.1). Genotypes exhibiting resistance (Fengyou 3 and Svitava) demonstrated heightened enrichment in the Rep/RepA coding region (positions 171–2510; 68.4% of hotspots) and the long intergenic region (LIR) (positions 1–170 and 2511–2749; 22.1%), in comparison to the susceptible Akteur (49.2% and 15.7%, respectively). These regions encode the replication initiator protein (Rep/RepA) and contain bidirectional promoters and the origin of replication. This suggests that resistant genotypes preferentially target viral replication machinery via RNAi. This pattern is consistent with lower viral titer in Fengyou 3 and Svitava (Figure 2 in ref. (Sharaf et al., 2023) [23]) and is consistent with the WDV-mediated suppression of RDR6 (Section 3.3), as the virus may prioritise silencing host amplification pathways in heavily targeted regions.

3.3.2. Sequence Motifs Underlying Differential Targeting

The identification of enriched motifs was achieved by employing the MEME v5.4.1 software on 100 nt hotspot sequences. This analysis yielded three enriched motifs per genotype (Supplementary Table S7). The top motif in resistant Svitava was CTTGTTACTGAT (E-value = 1.7), in Fengyou 3 was AYCGTGRACSYY (E-value = 3.3), and in Akteur was AACSYTRYWACT (E-value = 6.4). Lower E-values in resistant genotypes are indicative of a stronger sequence constraint and higher vsiRNA density.

Motifs enriched in resistant genotypes (Fengyou 3 and Svitava) were G/C-rich (e.g., CGT, GAC) and predicted to form stable hairpin structures (RNAfold; mean ΔG = −14.2 ± 1.8 kcal/mol), consistent with Dicer-like 2/4 (DCL2/4) cleavage preferences and primary vsiRNA hotspots. In contrast, the top motif in susceptible Akteur was A/U-rich, correlating with a reduced vsiRNA density and higher viral titer [23]. Furthermore, the analysis of the top-ranking motifs across all genotypes revealed partial sequence complementarity (seed region + 3–4 mismatches) to members of the tae-miR169 family, which have been found to be upregulated in resistant lines (log2FC > 2.0; Supplementary Table S5). This finding indicates that the formation of vsiRNA guided by miRNA may enhance the precision of targeting in the Fengyou 3 and Svitava genotypes.

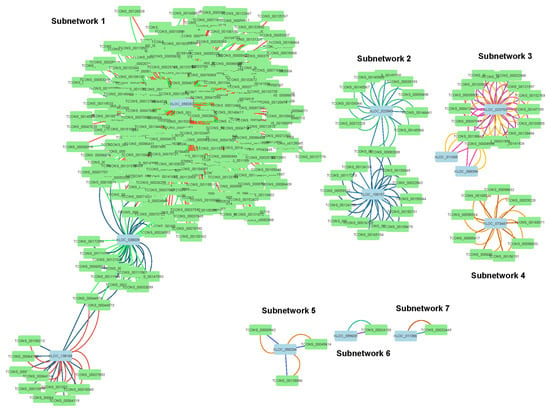

3.4. lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA Interaction Network During WVD Infection

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and mRNAs that share the same miRNA binding site act as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), sequestering miRNAs to regulate each other’s expression, a phenomenon termed ceRNA crosstalk [40]. In WDV-infected wheat genotypes, this mechanism likely modulates miRNA-mediated antiviral responses. The construction of the lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA co-expression network (Figure 5) was achieved through the utilisation of psRNATarget, followed by filtration using hypergeometric enrichment (Bonferroni p ≤ 0.05). RT-qPCR was used to validate the differential expression of five lncRNAs from the network, including three from Subnetwork 1 (XLOC_058282, XLOC_038039, XLOC_138168) (Figure 6). The central hub tae-miR169a-3p-s was found to be strongly upregulated in resistant Svitava (log2FC = 3.22; Supplementary Table S5). The GO enrichment analysis of Subnetwork 1 targets revealed a significant over-representation of DNA replication (GO:0006260, p = 1.2 × 10−6) and RNA silencing (GO:0016441). This subnetwork was found to be active exclusively in resistant genotypes (Fengyou 3, Svitava), which is consistent with the reduced viral titer (Figure 2 in ref. (Sharaf et al., 2023) [23]).

Figure 5.

lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA co-expression network of interactions in response to WDV infection. Co-expression network illustrating interactions between wheat lncRNAs and mRNAs mediated by wheat miRNAs in WDV-inoculated Triticum aestivum genotypes, visualised using Cytoscape v3.10.3. The network is divided into seven subnetworks (labeled 1–7). Nodes represent lncRNAs (light blue) and mRNAs (green), with edges indicating miRNA-mediated interactions. Edge colors represent distinct miRNA-mediated interactions. Full miRNA and target details are provided in Section 3.4.

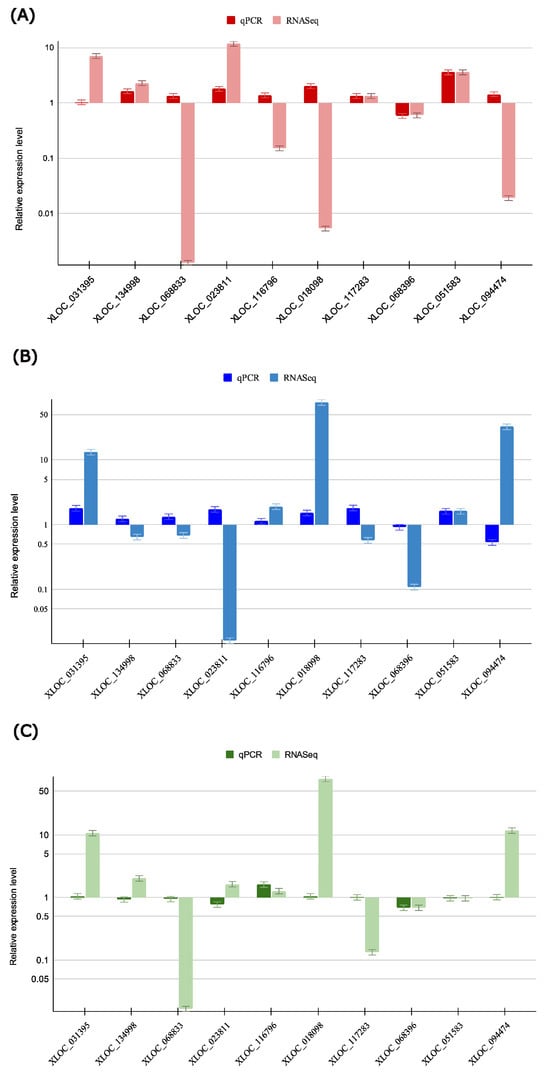

Figure 6.

RT-qPCR validation of differentially expressed lncRNAs in WDV-inoculated Triticum aestivum genotypes. Bar plots showing relative expression levels of selected differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs (DElncRNAs) in WDV-inoculated T. aestivum genotypes: (A) Akteur, (B) Svitava, and (C) Fengyou 3. For each DElncRNA and genotype, bars represent the following: (i) RT-qPCR relative expression for infected conditions; (ii) RNA-seq relative expression for infected conditions, derived from log2 fold changes. The Y-axis uses a log2 scale to display values above and below 1. Bars show mean relative expression ± standard error (SE) from four biological replicates, with SE for RNA-seq approximated from lfcSE. Of 30 comparisons, 17 (56.7%) showed directional concordance, with Pearson r = 0.41 (p = 0.025) between log2-transformed values. Discrepancies reflect biological variability and method sensitivity.

The co-expression network shows that only 16 miRNAs mediate 391 significant lncRNA-mRNA pairs organised into six subnetworks (Figure 5). We focused on Subnetwork 1, which contains the majority of interactions and is enriched in key metabolic pathways, and subnetwork 2, which includes miRNAs specifically upregulated in the resistant genotype Fengyou 3, due to their prominence and relevance to WDV resistance (Supplementary Table S5). The network comprises only 12 lncRNAs and 374 mRNAs (transcripts) (Figure 5), illustrating the complexity of RNA-regulatory interactions and highlighting the integral role that lncRNAs play in miRNA-mediated regulation. The results obtained demonstrate the presence of a highly interconnected network of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) molecules that play a crucial role in the regulation of metabolism, immunity, and viral suppression in resistant wheat. The first subnetwork comprises most interactions and contains three lncRNA nodes (XLOC_058282, XLOC_038039, and XLOC_138168). The lncRNA XLOC_058282 interacts with the largest number of transcripts (298 transcripts) in a ceRNA network, mediated by four miRNAs: two known miRNAs (tae-miR169a-3p-s, tae-miR169h-3p-s) and two novel miRNAs (tae-novel-miR024-s, tae-novel-miR026-s) identified through our analysis (Figure 5; Subnetwork 1). These novel miRNAs, detected with high-confidence criteria, alongside known miRNAs likely play a critical role in regulating multiple mRNAs via lncRNA-mediated ceRNA interactions in WDV-infected wheat, warranting further validation. Notably, all four miRNAs were differentially expressed in the resistant genotype Svitava (Supplementary Table S5). The lncRNA XLOC_038039 interacts with 21 transcripts and is mediated by two miRNAs (tae-miR827-5p-af and tae-miR169h-3p-s) (Figure 5; Subnetwork 1), both differentially expressed in the resistant genotypes Fengyou 3 and Svitava following WDV infection (Supplementary Table S5). The third lncRNA XLOC_138168 interacts with 12 transcripts and is mediated by tae-miR827-5p-af (also associated with XLOC_038039) and tae-miR397a-afs, which is downregulated in all three genotypes after WDV infection (Supplementary Table S5).

KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the 331 transcripts within this subnetwork are significantly enriched in pathways involved in carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid, and energy metabolism (Table 1), indicating the extensive regulatory potential of wheat lncRNAs and their associated miRNAs across diverse biological processes. Furthermore, the analysis showed that target transcripts of lncRNAs in this subnetwork are predominantly involved in key physiological processes, including xenobiotic degradation, signalling, growth, and development (Table 1). The second co-expression subnetwork comprises two lncRNA nodes, XLOC_023949 and XLOC_100157 (Figure 5; Subnetwork 2). XLOC_023949 interacts with eleven transcripts and is mediated by two miRNAs (tae-miR-14-5p-f and tae-novel-miR019-f), both of which were specifically upregulated in the resistant genotype Fengyou 3 after WDV infection (Supplementary Table S5). XLOC_100157 interacts with 15 transcripts and is also mediated by tae-novel-miR019-f (shared with XLOC_023949) and tae-miR827-5p-af, which also mediates lncRNAs from the first subnetwork (XLOC_038039 and XLOC_138168) (Figure 5). Mapping the transcripts in this subnetwork to the KEGG database provided insight into key metabolic pathways involved in the response to WDV. The 26 transcripts were assigned to several KEGG pathways, including signal transduction (e.g., MAPK signalling and plant hormone signalling), xenobiotic metabolism via cytochrome P450, and membrane transport (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of top metabolic pathways as revealed by KEGG enrichment analysis. Categories represent functional pathway groups, with the number of co-expressed transcripts assigned to each sub-network. KEGG IDs indicate relevant pathways.

Subnetwork 3 is highlighted for its genotype-specific miRNA regulation; it consists of three lncRNAs (XLOC_023753, XLOC_011055, and XLOC_068394) interacting with 16 transcripts, mediated by three miRNAs (tae-novel-miR005-afs, tae-novel-miR009-a, and tae-miR408-5p-as), including high-confidence novel miRNAs and the known miRNA tae-miR408-5p-as, which is implicated in stress responses (Supplementary Table S5). In this subnetwork, the lncRNA XLOC_023753 interacts with multiple messenger RNAs (mRNAs) mediated by three wheat microRNAs (miRNAs: tae-novel-miR005-afs, tae-miR408-5p-as, and tae-novel-miR009-a), with tae-miR408-5p-as and tae-novel-miR009-a each mediating a single mRNA interaction, while tae-novel-miR005-afs mediates multiple mRNA interactions (Figure 5; Subnetwork 3). Additionally, XLOC_023753 interacts with two other miRNAs in this subnetwork. The miRNAs in this subnetwork were either downregulated in all genotypes (tae-novel-miR005-afs), downregulated in Akteur and Svitava (tae-miR408-5p-as), or downregulated only in the susceptible genotype Akteur (tae-novel-miR009-a) following WDV infection (Supplementary Table S5). KEGG mapping showed that the transcripts in this subnetwork are involved exclusively in translation and transcription processes (Table 1). Another subnetwork comprises a single lncRNA (XLOC_073447), which interacts with nine transcripts mediated by tae-novel-miR002-af and tae-novel-miR025-s (Figure 5; Subnetwork 4). The miRNA tae-novel-miR002-af is upregulated in Akteur and Fengyou 3, whereas tae-novel-miR025-s is upregulated mainly in the resistant genotype Svitava after WDV infection (Supplementary Table S5). Although relatively small, this subnetwork has a substantial functional impact. KEGG analysis indicates that its transcripts participate in multiple pathways, including global and carbohydrate metabolism, signal transduction, and cell growth and death (Table 1 and Figure 5; Subnetwork 4).

Finally, three small subnetworks consist of a single lncRNA. The first, XLOC_058204, interacts with three transcripts mediated by tae-novel-miR026-s and tae-novel-miR024-s (Figure 5), both differentially expressed in the Svitava genotype (Supplementary Table S5). The remaining subnetworks comprise XLOC_099609 and XLOC_011386, each interacting with one transcript and mediated by two miRNAs (tae-novel-miR010-a and tae-miR159b-a) for the former, and tae-novel-miR023-fs and tae-novel-miR025-s for the latter (Figure 5; Subnetworks 6 and 7). Notably, three of these miRNAs (tae-novel-miR010-a, tae-miR159b-a, and tae-novel-miR023-fs) are specifically downregulated in the susceptible genotype Akteur, while tae-novel-miR025-s is upregulated in the resistant genotype Svitava (Supplementary Table S5). Due to the lack of KEGG annotations for the transcripts in these subnetworks, we used BLAST to identify orthologues in the NCBI database. Two transcripts associated with XLOC_058204 remain uncharacterised, while two others matched rust resistance kinase transcripts. The best BLAST hits for the remaining transcripts included F-box/FBD/LRR repeat proteins known to be involved in abiotic stress responses in plants [41]. The transcript TCONS_00024155, interacting with XLOC_099609, is currently uncharacterised but predicted to encode a hydrolase. Similarly, TCONS_00032449, associated with XLOC_011386, is thought to encode a receptor-like leucine-rich repeat protein kinase. In summary, the KEGG analysis of this regulatory co-expression network underscores its capacity to activate diverse signalling pathways involved in the immune response of wheat genotypes to WDV. These results highlight the potential roles of lncRNAs and miRNAs as critical regulators of the stress response and resistance mechanisms in wheat.

3.5. Validation of the DElncRNAs by Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

To assess the reliability and validity of the identified differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs), ten lncRNAs were selected for validation via RT-qPCR analysis (Supplementary Table S1). Among them, seven were confirmed to be differentially expressed, while three lncRNAs (XLOC_051583, XLOC_117283, and XLOC_116796) were not validated by RT-qPCR. This is likely to be a consequence of their low expression (TPM < 5) and moderate fold changes (1.2 ≤ log2FC ≤ 1.5), which are sensitive to the amplification efficiency and primer specificity. It is evident that these do not signify false positives; rather, they underscore the challenge of validating lowly expressed lncRNAs (Supplementary Tables S1, S3 and S4, and Figure 6). As shown in Figure 6, the selected DElncRNAs displayed differential expression between WDV-infected and non-inoculated wheat genotypes. Overall, the RT-qPCR results validated the RNA-seq-derived expression patterns of DElncRNAs, despite magnitude differences for some lncRNAs (Supplementary Table S3 and Figure 6), confirming the robustness of the in silico predicted networks in WDV-infected wheat.

Magnitude differences between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR are expected due to inherent methodological biases. RNA-seq uses global normalisation (TPM), while RT-qPCR depends on reference gene stability and primer efficiency. Despite this, 17 of 30 comparisons (56.7%) showed directional concordance, with Pearson r = 0.41 (p = 0.025) between log2-transformed fold changes, supporting the overall reliability of the RNA-seq data.

Due to this study’s focus on bioinformatic discovery and resource constraints in wheat, a non-model crop, only DElncRNA expression was validated, while RNA-seq data support differential miRNA expression (Supplementary Table S5). The functional validation of lncRNA-miRNA interactions, challenging in wheat due to its complex polyploid genome, is deferred to future studies.

4. Discussion

Wheat dwarf virus (WDV) poses a significant threat to wheat (Triticum aestivum) production, particularly in temperate regions [42]. Despite its agronomic importance, the molecular mechanisms underpinning host resistance remain poorly understood. Our previous study [23] assessed the resistance of the wheat genotypes Akteur, Fengyou 3, and Svitava to WDV by evaluating disease symptoms and quantifying virus titers using qPCR, revealing that Svitava and Fengyou 3 exhibit high resistance with mild symptoms and significantly lower viral titers compared to the susceptible genotype Akteur (Figure 2 in ref. (Sharaf et al., 2023) [23]). WDV was detected in all inoculated plants, confirming infection across the genotypes. In this study, we employed transcriptome and small RNA (sRNA) sequencing to characterise lncRNAs and miRNAs in wheat genotypes with contrasting resistance to WDV, using 72 sequencing libraries (three genotypes × two treatments × three biological replicates × four technical replicates; Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S2), contributing to the growing evidence of ncRNA regulatory roles in plant–virus interactions [4,41,42,43,44,45,46]. RNA-seq analyses were performed on three wheat cultivars: Akteur (susceptible), Fengyou 3 (resistant), and Svitava (resistant). Our findings reveal distinct expression patterns of lncRNAs and miRNAs linked to resistance phenotypes, offering insights into RNA-mediated regulatory networks in wheat antiviral defence. These results align with studies in other crops highlighting miRNA- and lncRNA-based regulation during geminivirus infections [43,44,45,46].

4.1. Genotype-Specific lncRNA and miRNA Regulation

Our analysis showed that WDV infection triggered significant alterations in the expression of both long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and microRNA (miRNA) across the three wheat genotypes. The resistant cultivar Svitava exhibits a predominance of upregulated differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs (DElncRNAs) (56.9%), whereas Akteur shows mostly downregulated DElncRNAs (66.7%) (Figure 1A–C). The lower number of DElncRNAs in Akteur (141) compared to Svitava (204) contrasts with our previous study [23], where Akteur exhibited higher mRNA differential expression, suggesting genotype-specific lncRNA-mediated regulatory networks. The KEGG analysis of mRNA targets revealed enrichment in the metabolism (e.g., carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid), MAPK signaling, and plant hormone pathways, alongside F-box proteins, resistance kinases, and ubiquitin ligases, indicating lncRNA-mediated immune metabolic reprogramming [41]. A 100 kilobase window was utilised to identify DElncRNA target genes, revealing significant regulatory interactions [42]. In terms of differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs), Akteur has 28 such miRNAs, of which 24 are downregulated, while resistant genotypes maintain a balanced profile (15 DEmiRNAs each, 5 upregulated, 10 downregulated) (Supplementary Table S5 and Figure 2C). MiRNAs such as miR168 and miR403 have been observed to target AGO1/AGO2 transcripts, which have been identified as regulators of antiviral RNA silencing. Dysregulation in Akteur has the potential to induce a state of disruption within the domain of Argonaute-dependent RNA interference (RNAi). Such a state of disruption would result in impaired viral genome targeting. Stable miRNA networks in resistant wheat likely support robust RNA silencing and hormonal defence coordination, consistent with barley studies showing miRNA profile shifts distinguishing susceptible from resistant genotypes during viral infection [46]. Several insect-conserved miRNAs (e.g., tae-miR-14-5p-f, likely from Psammotettix alienus) were detected at low levels in sRNA-seq libraries (Supplementary Table S5), possibly representing residual insect RNA or contamination from vector feeding, consistent with reports from Bemisia tabaci acquiring TYLCCNV [47].

We generated a co-expression network featuring 391 significant lncRNA-mRNA pairs mediated by 16 miRNAs, supporting a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) model where lncRNAs sequester miRNAs to modulate mRNA abundance (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S5). The lncRNA XLOC_058282 has been found to target 298 transcripts via four miRNAs, including tae-miR169a-3p-s. This targeting predominantly occurs in Svitava, suggesting a central coordinator of transcriptional defence programmes correlated with low viral titers (Figure 5; Subnetwork 1). The analysis of sRNA characteristics revealed genotype-specific antiviral silencing signatures. WDV infection induced a shift in the sRNA length within 18–25 nucleotides (e.g., 22.4 nt to 21.8 nt in Akteur, and 21.4 nt to 21.2 nt in Svitava), consistent with Dicer-like enzymes (DCL4, DCL2) processing viral dsRNA into siRNAs (Supplementary Table S7) [48]. A strong sense-strand bias in sRNA reads (e.g., 58.4% sense in Akteur) and a 5′ uracil (U) bias, particularly in Fengyou 3 (36.8% vs. 29% in Akteur, 28.5% in Svitava), were observed (Supplementary Table S8). The elevated 5′ U frequency in Fengyou 3 indicates enhanced AGO1-RISC activity, as AGO1 preferentially loads 5′ U-containing sRNAs to cleave viral RNA [49], contributing to its superior antiviral competence.

4.2. Potential Mechanisms of ncRNA-Mediated WDV Resistance

The genotype-specific lncRNA and miRNA profiles suggest multiple resistance mechanisms. The upregulation of DElncRNAs in resistant genotypes has been demonstrated to promote salicylic acid (SA) accumulation. In Arabidopsis, lncRNA SABC1 has been observed to repress SA biosynthesis under normal conditions, but is downregulated upon pathogen challenge, thus activating ICS1 and NAC3, thereby enhancing immunity [50]. Similarly, upregulated lncRNAs in Svitava and Fengyou 3 may facilitate SA-mediated systemic acquired resistance (SAR) via NPR1/TGA transcription factors [51]. LncRNAs such as SUNA1, which is induced by SA via NPR1, modulate pre-rRNA processing in order to prioritise defence protein synthesis [52], suggesting analogous roles in wheat. The ceRNA network, with hubs such as XLOC_058282, has been hypothesised to sequester microRNAs (miRNAs) to regulate defence-related mRNAs, thereby enhancing metabolic and hormonal pathways [53]. The presence of consistent miRNA profiles in resistant genotypes is indicative of robust RNAi, with miR168 and miR403 targeting AGO1/AGO2. Dysregulation in Akteur has been demonstrated to impede RNAi, thereby facilitating elevated viral titers. The 5′ U bias in vsiRNAs, particularly in Fengyou 3, has been demonstrated to enhance the AGO1–RISC efficiency, aligning with models where AGO1 coordinates resistance and growth [54]. The sense-strand bias suggests that viral suppressors of RNA silencing (VSRs) inhibit RDR6-mediated dsRNA synthesis, which is common in DNA virus infections [55]. In rice, miR444 has been shown to regulate antiviral RNAi via RDR1 [56], suggesting the presence of analogous mechanisms in wheat.

4.3. Study Constraints and Research Prospects

The reliability of the RNA-seq data was validated through RT-qPCR of selected DElncRNAs, confirming differential expression between WDV-infected and non-inoculated wheat plants (Figure 6 and Supplementary Table S3). The present study focuses on in- silico analysis with the RT-qPCR validation of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a common approach in discovery-based studies of non-model crops like wheat, where bioinformatic predictions are prioritised due to resource constraints [57]. The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of protein-coding genes co-expressed with DElncRNAs revealed enrichment in processes such as ubiquinone biosynthesis and protein ufmylation (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Figure S2), implicated in cellular homeostasis and stress responses [58]. However, the lack of RT-qPCR validation for miRNAs and mRNAs limits the direct confirmation of their expression. The hexaploid nature of T. aestivum complicates the functional validation of lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions, which was deferred [58,59]. Low-abundance insect-derived miRNAs (e.g., from Psammotettix alienus) in sRNA-seq libraries may reflect contamination, requiring further investigation. Recent advances in plant ncRNA research highlight their role in stress adaptation [60]. Further research is required to validate the expression of miRNAs and mRNA using RT-qPCR. Furthermore, CRISPR-based knockout experiments targeting lncRNA could elucidate the roles these play in resistance to Wheat dwarf virus (WDV), despite the complexity of the wheat genome [59]. Additional time points or tissues may reveal dynamic ncRNA responses, enhancing the understanding of WDV–wheat interactions. Recent work on ncRNAs in wheat defence against the Fusarium head blight suggests broader applications for ncRNA-mediated resistance strategies [61].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the pivotal roles of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), and small RNAs (sRNAs) [59] in orchestrating wheat’s defence responses to Wheat dwarf virus (WDV) infection across three contrasting genotypes: Akteur (susceptible), Fengyou 3 (resistant), and Svitava (resistant). The resistant genotypes exhibited distinct regulatory strategies, characterised by the upregulation of lncRNAs (e.g., 56.9% in Svitava) and a balanced miRNA expression profile, contributing to the formation of complex RNA-mediated networks. These were further supported by active sRNA-driven antiviral RNA interference (RNAi) responses [62,63,64]. The identification of 1166 differentially expressed sRNA viral genomic positions, including conserved hotspots and genotype-specific targets (e.g., 408 unique viral genomic positions in Akteur versus Fengyou 3), underscores the presence of tailored RNAi defence mechanisms in resistant cultivars. Barley yellow dwarf virus-GAV-derived vsiRNAs in wheat target chlorophyll synthase contribute to symptom development, suggesting similar mechanisms in WDV infection [65]. Although canonical 21–24 nt phasing was absent, likely reflecting WDV’s ability to evade systemic silencing [63,64], the sRNA data suggest a dynamic and genotype-dependent antiviral response. This work builds upon previous studies by integrating sRNA dynamics with lncRNA-miRNA regulatory interactions, thus revealing novel facets of non-coding RNA involvement in antiviral defence and potential gaps in viral genome targeting. Future research should prioritise the functional validation of key regulatory RNAs, elucidate their role in systemic RNAi responses, and explore their application in breeding programmes aimed at enhancing resistance to WDV, ultimately supporting global wheat production resilience.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010067/s1, Figure S1: Experimental design. Eighteen plants (three genotypes × two treatments × three biological replicates) were grown. Each biological sample was sequenced in four technical replicates, generating a total of 72 mRNA-seq and 72 small RNA-seq libraries; Figure S2: Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of protein-coding genes co-expressed with differentially expressed lncRNAs (DElncRNAs); Figure S3: Small RNA coverage across the reassembled WDV genomes in infected wheat genotypes; Table S1. Primers for RT-qPCR analysis; Table S2: Summary of the miRNA sequencing results; Table S3: Differentially expressed lncRNAs in the three genotypes under the WDV infection; Table S4: Pearson correlation coefficients between lncRNAs and transcripts, the correlation coefficient indicating the strength and direction of their expression relationship; Table S5: Differentially expressed miRNAs in the three genotypes under WDV infection, including their type and experimental evidence information; Table S6: Size distribution of viral sRNAs across the three genotypes under WDV infection; Table S7: Strand polarity and enriched motifs in hotspots of sRNAs in infected samples of the three genotypes under WDV infection; Table S8: 5′ nucleotide preference of sRNAs in the three genotypes under WDV infection.

Author Contributions

A.S.: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Formal analysis, Software, Data curation. J.K.K.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. E.I.: Methodology, Validation, Data curation. J.R.: Methodology, Investigation. P.N.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing—review and editing, Formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project no. MZE-RO0425 from the Ministry of Agriculture, The Czech Republic. AS is paid by the SequAna Sequencing Analysis Core Facility through the Department of Biology which made this work possible.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The 144 mRNA and miRNA sequencing datasets generated and analysed during this study are publicly available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accessed on 15 April 2024] under the accession numbers [GSE192518] (mRNA) and [GSE230156] (miRNA). Additional data supporting the findings of this study are provided in Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Glenda Alquicer for her assistance with qPCR analysis. We thank Markéta Vítámvásová for her excellent technical assistance. We also thank Xifeng Wang for providing Fengyou 3 genotype.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cheng, J.; Kapranov, P.; Drenkow, J.; Dike, S.; Brubaker, S.; Patel, S.; Long, J.; Stern, D.; Tammana, H.; Helt, G.; et al. Transcriptional maps of 10 human chromosomes at 5-nucleotide resolution. Science 2005, 308, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.D.; Sung, S. Long noncoding RNA: Unveiling hidden layer of gene regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.Q. Long noncoding RNAs: New regulators in plant development. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 436, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Viral lncRNA: A regulatory molecule for controlling virus life cycle. Noncoding RNA Res. 2017, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, F.; Martienssen, R. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tycowski, K.T.; Guo, Y.E.; Lee, N.; Moss, W.N.; Vallery, T.K.; Xie, M.; Steitz, J.A. Viral noncoding RNAs: More surprises. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 567–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.A.; Shen, R.; Staplin, W.; Kanodia, P. Noncoding RNAs of plant viruses and viroids: Sponges of host translation and RNA interference machinery. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2016, 29, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Kanno, T.; Matzke, A.J. RNA-directed DNA methylation: The evolution of a complex epigenetic pathway in flowering plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilartz, M.; Jeske, H. Mapping of Abutilon mosaic geminivirus minichromosomes. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10808–10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, R.C.; Asad, S.; Wolf, J.N.; Mohannath, G.; Bisaro, D.M. Geminivirus AL2 and L2 proteins suppress transcriptional gene silencing and cause genome-wide reductions in cytosine methylation. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5005–5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrieme, A.-K.; Will, T.; Pillen, K.; Stahl, A. The Past, Present, and Future of Wheat dwarf virus Management—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacke, J. Wheat dwarf virus disease. Biol. Plant 1961, 3, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, M.I. Functions and interactions of mastrevirus gene products. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 60, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalk, H.J.; Matzeit, V.; Schiller, B.; Schell, J.; Gronenborn, B. Wheat dwarf virus, a geminivirus of graminaceous plants, needs splicing for replication. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, C. Geminivirus DNA replication. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999, 56, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, S.; Fernandez-Lobato, M.; Gooding, P.S.; Mullineaux, P.M.; Fenoll, C. The two non-structural proteins of Wheat dwarf virus involved in viral gene expression and replication are retinoblastoma-binding proteins. Virology 1996, 219, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, C.; Ramirez-Parra, E.; Mar Castellano, M.; Sanz-Burgos, A.P.; Luque, A.; Missich, R. Geminivirus DNA replication and cell cycle interactions. Vet. Microbiol. 2004, 98, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Replication-associated proteins encoded by Wheat dwarf virus act as RNA silencing suppressors. Virus Res. 2014, 190, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Wu, Q.; Ito, T.; Cillo, F.; Li, W.X.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.-L.; Ding, S.-W. RNAi-mediated viral immunity requires amplification of virus-derived siRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, T.; Liu, T.; Ma, N.; Yang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, B. Genome-wide analysis of tomato long non-coding RNAs and identification as endogenous target mimic for microRNA in response to TYLCV infection. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Spetz, C.; Li, L.; Wang, X. Comparative transcriptome analysis in Triticum aestivum infecting Wheat dwarf virus reveals the effects of viral infection on phytohormone and photosynthesis metabolism pathways. Phytopathol. Res. 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Tholt, G.; Ivanics, M.; Várallyay, É.; Jenes, B.; Havelda, Z. Polycistronic artificial miRNA-mediated resistance to Wheat dwarf virus in barley is highly efficient at low temperature. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharaf, A.; Nuc, P.; Ripl, J.; Alquicer, G.; Ibrahim, E.; Wang, X.; Maruthi, M.N.; Kundu, J.K. Transcriptome dynamics in Triticum aestivum genotypes associated with resistance against the Wheat dwarf virus. Viruses 2023, 15, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, J.K.; Gadiou, S.; Červená, G. Discrimination and genetic diversity of Wheat dwarf virus in the Czech Republic. Virus Genes 2009, 38, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction: Twenty-something years on. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szcześniak, M.W.; Bryzghalov, O.; Ciomborowska-Basheer, J.; Makałowska, I. CANTATAdb 2.0: Expanding the collection of plant long noncoding RNAs. In Plant Long Non-Coding RNAs: Methods in Molecular Biology; Chekanova, J.A., Wang, H.L.V., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.J.; Yang, D.C.; Kong, L.; Hou, M.; Meng, Y.Q.; Wei, L.; Gao, G. CPC2: A fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W12–W16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Finn, R.D. Predicting active site residue annotations in the Pfam database. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.U.; Gautam, A.; Bethune, J.; Sattar, A.; Fiosins, M.; Magruder, D.S.; Capece, V.; Shomroni, O.; Bonn, S. Oasis 2: Improved online analysis of small RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, D.J.; Chen, Y.; Smyth, G.K. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 4288–4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; Ebert, D.; Muruganujan, A.; Mills, C.; Albou, L.P.; Mushayamaha, T.; Thomas, P.D. PANTHER version 16: A revised family classification, tree-based classification tool, enhancer regions and extensive API. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D394–D403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, C.; Liu, Z. An easy-to-follow pipeline for long noncoding RNA identification: A case study in diploid strawberry Fragaria vesca. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1933, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhao, P.X. psRNATarget: A small RNA target analysis server (2017 release). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W49–W54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Jarosová, J.; Kundu, J.K. Validation of reference genes as internal control for studying viral infections in cereals by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadiou, S.; Ripl, J.; Jaňourová, B.; Jarošová, J.; Kundu, J.K. Real-time PCR assay for the discrimination and quantification of wheat and barley strains of Wheat dwarf virus. Virus Genes 2011, 44, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supek, F.; Bošnjak, M.; Škunca, N.; Šmuc, T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.; Rinn, J.; Pandolfi, P.P. The multilayered complexity of ceRNA crosstalk and competition. Nature 2014, 505, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Nijhawan, A.; Arora, R.; Agarwal, P.; Ray, S.; Sharma, P.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. F-box proteins in rice. Genome-wide analysis, classification, temporal and spatial gene expression during panicle and seed development, and regulation by light and abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1467–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abt, I.; Jacquot, E. Wheat dwarf. In Virus Diseases of Tropical and Subtropical Crops; Tennant, P., Fermin, R., Eds.; Plant Protection Series; CAB International: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Jung, C.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Deng, S.; Bernad, L.; Arenas-Huertero, C.; Chua, N.H. Genome-wide analysis uncovers regulation of long intergenic noncoding RNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4333–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cho, W.K.; Byun, H.S.; Chavan, V.; Kil, E.J.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.W. Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNAs in tomato plants irradiated by neutrons followed by infection with Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, S.V.; Yogindran, S.; Gnanasekaran, P.; Chakraborty, S.; Winter, S.; Pappu, H.R. Virus and viroid-derived small RNAs as modulators of host gene expression: Molecular insights into pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 614231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Shen, D.; Wang, J.; Ling, X.; Hu, Z.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; Huang, J.; Yu, W.; et al. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus intergenic siRNAs target a host long noncoding RNA to modulate disease symptoms. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Yang, X.; Ding, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, S.S.; Wang, X.W.; Zhou, X. MicroRNA profiling of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci Middle East-Asia Minor I following the acquisition of Tomato yellow leaf curl China virus. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, H. Small RNAs participate in plant–virus interaction and their application in plant viral defense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]