Milk Performance and Blood Biochemical Indicators of Dairy Goats Fed with Black Oat Supplements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and BW Analysis

2.2. Diet Composition and Feed Analysis

2.3. Milk Sampling and Analysis

2.4. Blood Sampling and Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

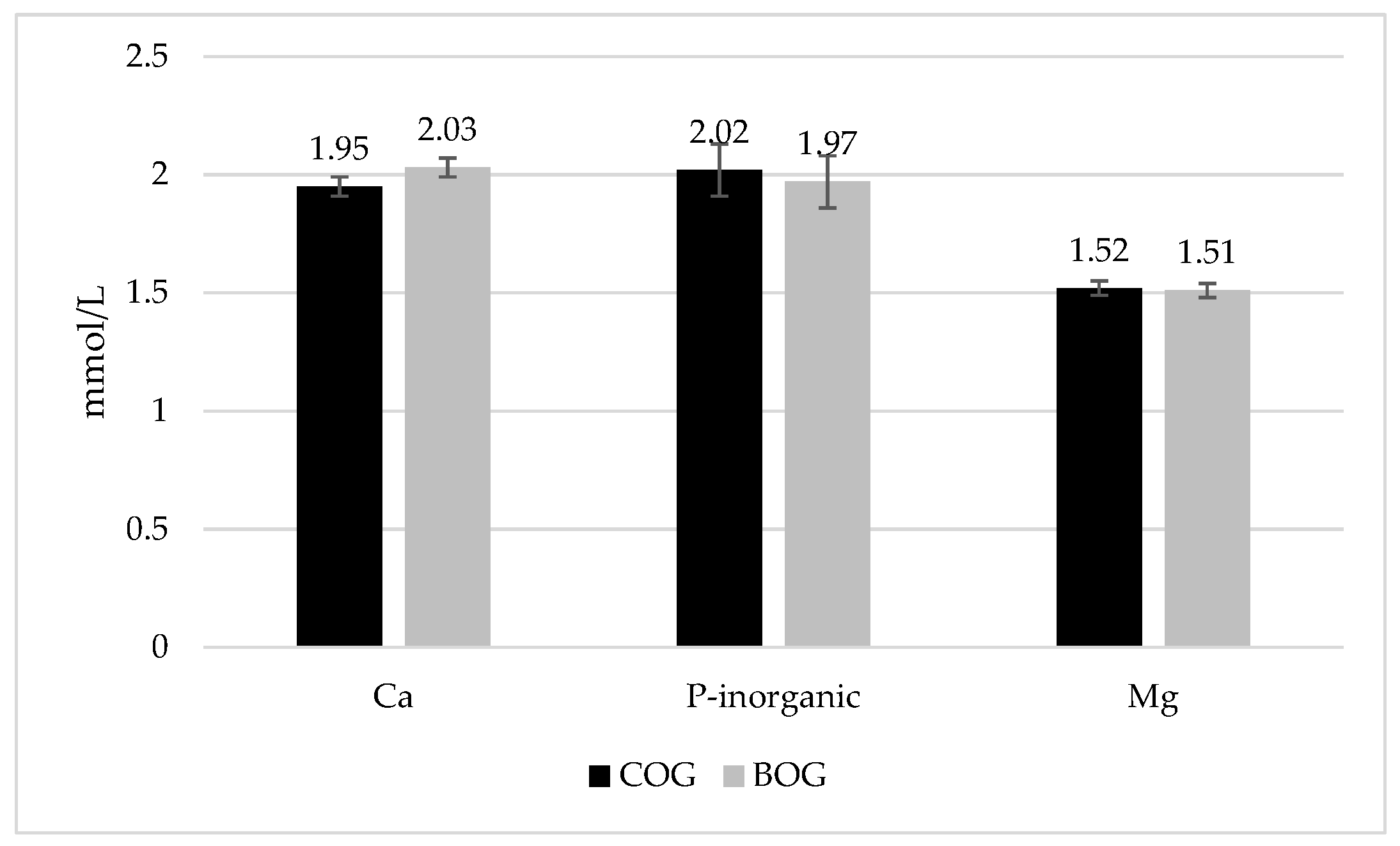

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Formato, M.; Cimmino, G.; Brahmi-Chendouh, N.; Piccolella, S.; Pacifico, S. Polyphenols for Livestock Feed: Sustainable Perspectives for Animal Husbandry? Molecules 2022, 27, 7752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Deng, L.; Chen, M.; Che, Y.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Chen, G.; Feng, T. Phytogenic feed additives as natural antibiotic alternatives in animal health and production: A review of the literature of the last decade. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 244–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediouni, M.; Diallo, A.B.; Makarenkov, V. Quantifying antimicrobial resistance in food-producing animals in North America. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1542472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.T.; Caffrey, N.P.; Nóbrega, D.B.; Cork, S.C.; Ronksley, P.E.; Barkema, H.W.; Polachek, A.J.; Sharma, H.G.N.; Kellner, J.D.; Ghali, W.A. Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2017, 1, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankic, T.; Voljc, M.; Salobir, J.; Rezar, V. Use of herbs and spices and their extracts in animal nutrition. Acta Agric. Slov. 2009, 94, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, B.; Calabrò, S.; Cutrignelli, M.I.; Barbier, E.; Haroutounian, S.; Yanza, J.R.; Jayanegara, A.; Torrent, A.; Vastolo, A.; Hoste, H.; et al. Screening of mediterranean agro-industrial by-products rich in phenolic compounds for their ability to modulate in vitro ruminal fermentation. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Functional Properties of Polyphenols in Grains and Effects of Physicochemical Processing on Polyphenols. Hindawi J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 2793973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, N.M.; Gonzalez-Bulnes, A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Polyphenols in Farm Animals: Source of Reproductive Gain or Waste? Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, C.; Schehl, B.D.; Arendt, E.K. Fundamental study on protein changes taking place during malting of oats. J. Cereal Sci. 2009, 49, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; De, S.; Belkheir, A. Avena sativa (oat) a potential nutraceutical and therapeutic agent: An overview. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrey, A.; Spain, J.N. Results of a nationwide survey to determine feedstuffs fed to lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, E.A.; Rose, D.J.; Stewart, D. Processing of oats and the impact of processing operations on nutrition and health benefits. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, R.; van Klinken, B.J.W. Oats, more than just a whole grain: An introduction. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aal, E.S.M.; Young, J.C.; Rabalski, I. Anthocyanin Composition in Black, Blue, Pink, Purple, and Red Cereal Grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4696–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, M.; Jójárt, R.; Fónad, P.; Mihály, R.; Palágyi, A. Phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of colored oats. Food Chem. 2018, 268, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaneli, R.S.; dos Santos, H.P.; Fontaneli, R.S.; Oliveira, J.T.; Lehmen, R.I.; Dreon, G. Winter forage grasses. In Forrageiras para Integração Lavoura-Pecuária-Floresta na Região Sul-Brasileira; Fontaneli, R.S., dos Santos, H.P., Fontaneli, R.S., Eds.; EMBRAPA: Brasilia, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, F.; Lei, Y.; Han, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S. Antioxidant ability of polyphenols from black rice, buckwheat and oats: In vitro and in vivo. Czech J. Food Sci. 2020, 38, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišová, E.; Czech, M.; Hozlár, P.; Zaguła, G.; Gumul, D.; Grygorieva, O.; Makowska, A.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł. Nutritional, Antioxidant and Sensory Characteristics of Bread Enriched with Whole meal Flour from Slovakian Black Oat Varieties. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Salman, M.; Sahrif, M.S. Application of polyphenolic compounds in animal nutrition and their promising effects. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2023, 32, 233–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, G.M.C.; Carvalho, S.; Pires, C.C.; Motta, J.H.; Teixeira, W.S.; Borges, L.I.; Fleig, M.; Pilecco, V.M.; Farinha, E.T.; Venturini, R.S. Consumption, performance and economic analysis of the feeding of lambs finished in feedlot as the use of high-grain diets. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2015, 67, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes, G.M.C.; Carvalho, S.; Venturini, R.S.; Teixeira, W.S.; Motta, J.H.; Borges, L.I.; Rosa, J.S.; Pesamosca, A.C.; Cocco, A.; Mello, V.L.; et al. Carcass characteristics and tissue composition of the meat of feedlot lambs fed high-grain diets. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. Lond 2018, 39, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar]

- Antunović, Z.; Klir Šalavardić, Ž.; Mioč, B.; Steiner, Z.; Ðidara, M.; Sičaja, V.; Pavić, V.; Mihajlović, L.; Jakobek, L.; Novoselec, J. Dietary Effects of Black-Oat-Rich Polyphenols on Production Traits, Metabolic Profile, Antioxidative Status, and Carcass Quality of Fattening Lambs. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derenevicz Faisca, L.; Peres, M.T.P.; Fernandes, S.R.; Bonnet, O.J.F.; Batista, R.; Deiss, L.; Monteiro, A.G. A new insight about the selection and intake of forage by ewes and lambs in different production systems on pasture. Small Rum. Res. 2023, 221, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-García, J.I.; López-González, F.; Estrada-Flores, J.G.; Flores-Calvete, G.; Prospero-Bernal, F.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Black oat (Avena strigosa Schreb.) grazing or silage for small-scale dairy systems in the highlands of central Mexico. Part I. Crop and dairy cow performance. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 80, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta, S.R.; Silveira, A.L.F.; Adami, P.F.; Pelissari, A.; Cassol, L.C.; Assmann, A.L. Effect of goat grazing of black oat with different plots and corn yield with different nitrogen levels in succession. Rev. Ciênc. Agrovet. 2019, 18, 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Adami, P.F.; Pitta, C.S.R.; da Silveira, A.L.F.; Pelissari, A.; Hill, J.A.G.; Assmann, A.L.; Ferrazza, J.M. Ingestive behavior, forage intake and performance of goats fed with different levels of supplementation. Pesq. Agropec. Bras. 2013, 48, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.B.P.; Del Valle, T.A.; Ghizzi, L.G.; Silva, G.G.; Gheller, L.S.; Marques, J.A.; Dias, M.S.S.; Nunes, A.T.; Grigoletto, N.T.S.; Takiya, C.S.; et al. Partial replacement of corn silage with whole-plant soybean and black oat silages for dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 9842–9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Miranda, A.; Estrada-Flores, J.G.; Morales-Almaraz, E.; López-González, F.; Flores-Calvete, G.; Arriaga-Jordán, C.M. Barley or black oat silages in feeding strategies for small-scale dairy systems in the highlands of Mexico. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 100, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, P.M.; Maestrini, O. Body condition of dairy goats in extensive systems of production: Method of estimation. Ann. Zotech 1985, 34, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids and New World Camelids; The National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 256.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. In Association of Analytical Communities; AOAC: Arlington, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobek, L.; Matic, P.; Ištuk, J.; Barron, A.R. Study of interactions between individual phenolics of aronia with barley β-glucan. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 71, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRN ISO 9622:2017; Milk and Liquid Milk Products—Guidelines for the Application of Mid-Infrared Spectrometry (ISO 9622:2013). Croatian Standards Institute: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017.

- Pulina, G.; Cannas, A.; Serra, A.; Vallebella, R. Determination and estimation of the energy value in Sardinian goat milk. In Proceedings of the Congress of Società Italiana Scienze Veterinarie (SISVet), Altavilla Milicia, Italy, 25–28 September 1991; pp. 1779–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Wiggans, G.R.; Shook, G.E. A lactation measure of somatic cell count. J. Dairy Sci. 1987, 70, 2666–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS 9.4 Copyright © 2002–2012; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2013.

- Olagaray, K.E.; Brouk, M.J.; Mamedova, L.K.; Sivinski, S.E.; Liu, H.; Robert, F.; Dupuis, E.; Zachut, M.; Bradford, B.J.; Loor, J.J. Dietary supplementation of Scutellaria baicalensis extract during early lactation decreases milk somatic cells and increases whole lactation milk yield in dairy cattle. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholif, A.E.; Hassan, A.A.; El Ashry, G.M.; Bakr, M.H.; El-Zaiat, H.M.; Olafadehan, O.A.; Matloup, O.H. Phytogenic feed additives mixture enhances the lactational performance, feed utilization and ruminal fermentation of Friesian cows. Anim. Biotechn. 2020, 32, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholif, A.E.; Matloup, O.H.; Morsy, T.A.; Abdo, M.M.; Elella, A.A.A.; Anele, U.Y.; Swanson, K.C. Rosemary and lemongrass herbs as phytogenic feed additives to improve efficient feed utilization, manipulate rumen fermentation and elevate milk production of Damascus goats. Livest. Sci. 2017, 204, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.Z.M.; Kholif, A.E.; Elghandour, M.M.Y.; Buendía, G.; Mariezcurrena, M.D.; Hernandez, S.R.; Camacho, L.M. Influence of oral administration of Salix babylonica extract on milk production and composition in dairy cows. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 13, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunović, Z.; Šperanda, M.; Novoselec, J.; Ðidara, M.; Mioč, B.; Klir, Ž.; Samac, D. Blood Metabolic Profile and Acid-Base Balance of Dairy Goats and Their Kids during Lactation. Vet. Arh. 2017, 87, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, J.; Harvey, J.; Bruss, M. Clinical Biochemistry of Domestic Animals; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 963. [Google Scholar]

- Antunović, Z.; Mioč, B.; Lončarić, Z.; Klir Šalavardić, Ž.; Širić, I.; Držaić, V.; Novoselec, J. Changes of macromineral and trace element concentration in the blood of ewes during lactation period. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 66, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.M.; Aljumaah, R.S. Metabolic blood profiles and milk compositions of peri-parturient and early lactation periods in sheep. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2012, 7, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunović, Z.; Novoselec, J.; Klir Šalavardić, Ž.; Steiner, Z.; Drenjančević, M.; Pavić, V.; Ðidara, M.; Ronta, M.; Jakobek Barron, L.; Mioč, B. The Effect of Grape Seed Cake as a Dietary Supplement Rich in Polyphenols on the Quantity and Quality of Milk, Metabolic Profile of Blood, and Antioxidative Status of Lactating Dairy Goats. Agriculture 2024, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunović, Z.; Novoselec, J.; Mioč, B.; Širić, I.; Držaić, V.; Klir Šalavardić, Ž. Macroelements in the Milk of the Lacaune Dairy Sheep Depending on the Stage of Lactation. Poljoprivreda 2024, 30, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcells, J.; Aris, A.; Serrano, A.; Seradj, A.R.; Crespo, J.; Devant, M. Effects of an extract of plant flavonoids (Bioflavex) on rumen fermentation and performance in heifers fed high-concentrate diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 90, 4975–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuh, J.V.; Mbwaye, J. Serological changes in goats experimentally infected with Fasciola gigantica in Buea sub-division of S.W.P. Cameroon. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 131, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannenas, I.; Skoufos, J.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Wiemann, M.; Gortzi, O.; Lalas, S.; Kyriazakis, I. Effects of essential oils on milk production, milk composition, and rumen microbiota in Chios dairy ewes. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5569–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.R.; Ramos, E.; De la Tore, H.R.; Extremera, F.G.; Sanz Sampelayo, M.R. Blood metabolites as indicators of energy status in goats. Option Mediterr. Ser. A 2006, 74, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Ling, W.; Ma, J.; Xia, M.; Hou, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Tang, Z. An anthocyanin-rich extract from black rice enhances atherosclerotic plaque stabilization in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 2220–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, J.F.; Monteiro, V.V.S.; Souza Gomes, R.; Carmo, M.M.; Costa, G.V.; Ribera, P.C.; Monteiro, M.C. Action mechanism and cardiovascular e_ect of anthocyanins: A systematic review of animal and human studies. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francavilla, A.; Joye, I.J. Anthocyanins in Whole Grain Cereals and Their Potential effect on Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, Y. Dietary Supplementation of Black Rice Anthocyanin Extract Regulates Cholesterol Metabolism and Improves Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in C57BL/6J Mice Fed a High-Fat and Cholesterol Diet. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Khare, P.; Kumar, A.; Chunduri, V.; Kumar, A.; Kapoor, P.; Mangal, P.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Bishnoi, M.; Garg, M. Anthocyanin-Biofortified Colored Wheat Prevents High Fat Diet–Induced Alterations in Mice: Nutrigenomics Studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, 1900999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Tiomokin, D. Toxicity induced by poultry litter consumption: Effect on parameters reflecting liver function in beef cows. Anim. Prod. 1992, 54, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredient (% DM) | Group | Black Oats | Hay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG | BOG | |||

| Ingredients composition | ||||

| Corn | 42.30 | 42.30 | ||

| Oats | 15.00 | - | ||

| Black oats | - | 15.00 | ||

| Barley | 19.00 | 19.00 | ||

| Soybean meal | 9.00 | 9.00 | ||

| Soybean, toasted | 11.00 | 11.00 | ||

| Limestone | 0.30 | 0.30 | ||

| Cattle salt | 0.40 | 0.40 | ||

| Mineral premix * | 3.00 | 3.00 | ||

| Chemical composition (g/kg DM) | ||||

| Dry matter | 948.80 | 951.00 | 952.00 | 951.15 |

| Crude proteins | 143.64 | 150.40 | 84.50 | 75.90 |

| Ether extract | 48.60 | 48.80 | 47.50 | 11.20 |

| Crude fiber | 50.18 | 50.50 | 101.10 | 328.60 |

| Ash | 65.04 | 65.10 | 28.60 | 47.40 |

| NEL, MJ/kg | 7.18 | 7.19 | - | 4.45 |

| Polyphenols (total), mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/kg | 1582.61 | 2054.63 | 1416.52 | 5650.61 |

| Diets | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG | BOG | Diet | P | D × P | ||

| Live BW, kg | 52.79 | 51.09 | 0.97 | 0.314 | 0.353 | 0.929 |

| BCS, point | 2.17 | 2.43 | 0.10 | 0.205 | 0.493 | 0.694 |

| Milk yield, g/day | 1264.94 | 1542.10 | 93.18 | 0.098 | 0.837 | 0.649 |

| Fat, % | 3.32 | 3.40 | 0.18 | 0.718 | 0.906 | 0.574 |

| Protein, % | 2.91 | 2.84 | 0.06 | 0.572 | 0.976 | 0.875 |

| Lactose, % | 4.45 | 4.38 | 0.03 | 0.245 | 0.169 | 0.661 |

| Log SCC, log | 6.13 | 6.14 | 0.09 | 0.929 | 0.834 | 0.533 |

| Log CFU, log | 3.97 | 3.96 | 0.12 | 0.980 | 0.725 | 0.365 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 7.90 | 7.05 | 0.27 | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.149 |

| Ca, mmol/L | 34.82 | 37.90 | 2.18 | 0.497 | 0.418 | 0.381 |

| P, mmol/L | 24.16 | 24.03 | 0.82 | 0.939 | 0.757 | 0.525 |

| TP, g/L | 24.18 | 23.58 | 0.78 | 0.715 | 0.784 | 0.512 |

| ALB, g/L | 19.02 | 19.82 | 0.61 | 0.530 | 0.504 | 0.337 |

| GLOB, g/L | 5.16 | 3.96 | 0.32 | 0.091 | 0.936 | 0.869 |

| AST, U/L | 51.90 | 79.23 | 10.56 | 0.202 | 0.355 | 0.116 |

| ALT, U/L | 58.87 | 64.12 | 9.54 | 0.769 | 0.823 | 0.524 |

| ALP, U/L | 66.20 | 49.24 | 10.26 | 0.370 | 0.315 | 0.859 |

| GGT, U/L | 421.90 | 414.55 | 19.90 | 0.933 | 0.105 | 0.576 |

| GPx, U/L | 45.96 | 43.67 | 3.03 | 0.670 | 0.001 | 0.765 |

| Diets | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG | BOG | D | P | D × P | ||

| Urea, mmol/L | 8.75 | 7.03 | 0.32 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.184 |

| GUK, mmol/L | 4.40 | 4.77 | 0.15 | 0.223 | 0.121 | 0.458 |

| TP, g/L | 66.15 | 69.62 | 1.68 | 0.307 | 0.129 | 0.750 |

| ALB, g/L | 23.30 | 24.60 | 0.63 | 0.312 | 0.311 | 0.643 |

| GLOB, g/L | 42.85 | 45.03 | 1.21 | 0.378 | 0.133 | 0.853 |

| CHOL, mmol/L | 2.35 | 2.19 | 0.09 | 0.341 | 0.374 | 0.680 |

| HDL-CHOL, mmol/L | 1.43 | 1.34 | 0.04 | 0.327 | 0.599 | 0.718 |

| LDL-CHOL, mmol/L | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.390 | 0.255 | 0.582 |

| TGC, mmol/L | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.747 | 0.001 | 0.013 |

| NEFA, mmol/L | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.901 | 0.011 | 0.212 |

| BHB, mmol/L | 0.78 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.976 | 0.207 | 0.726 |

| Diets | SEM | p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COB | BOG | D | P | D × P | ||

| AST, U/L | 131.30 | 122.17 | 5.01 | 0.395 | 0.902 | 0.486 |

| ALT, U/L | 20.22 | 20.61 | 1.13 | 0.865 | 0.092 | 0.989 |

| GGT, U/L | 43.76 | 45.41 | 1.63 | 0.610 | 0.041 | 0.967 |

| CK, U/L | 184.95 | 197.76 | 12.50 | 0.577 | 0.186 | 0.496 |

| GPx, U/L | 1029.83 | 1023.76 | 55.25 | 0.955 | 0.023 | 0.669 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Antunović, Z.; Novoselec, J.; Steiner, Z.; Didara, M.; Ronta, M.; Klir Šalavardić, Ž. Milk Performance and Blood Biochemical Indicators of Dairy Goats Fed with Black Oat Supplements. Agriculture 2026, 16, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010068

Antunović Z, Novoselec J, Steiner Z, Didara M, Ronta M, Klir Šalavardić Ž. Milk Performance and Blood Biochemical Indicators of Dairy Goats Fed with Black Oat Supplements. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntunović, Zvonko, Josip Novoselec, Zvonimir Steiner, Mislav Didara, Mario Ronta, and Željka Klir Šalavardić. 2026. "Milk Performance and Blood Biochemical Indicators of Dairy Goats Fed with Black Oat Supplements" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010068

APA StyleAntunović, Z., Novoselec, J., Steiner, Z., Didara, M., Ronta, M., & Klir Šalavardić, Ž. (2026). Milk Performance and Blood Biochemical Indicators of Dairy Goats Fed with Black Oat Supplements. Agriculture, 16(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010068