Abstract

Antagonistic endophytes are one of the most effective methods for crop disease biocontrol. This study reports on a convenient method termed ‘Targeted Identification of Disease-resistant Endophytes’ (TIDRE), which combines the isolation of culturable endophytic isolates from plant tissues with the screening of phytopathogen-antagonistic microbes. In addition to the direct discovery of endophytes with resistance to specific phytopathogens, the TIDRE method also facilitates the screening of endophyte-based disease-resistant crop lines. Using the TIDRE protocol, we successfully isolated endophytic bacterial strains with antagonistic activity against the pathogenic fungus Fusarium oxysporum from a traditional Chinese medicinal herb Panax notoginseng. These candidate bacteria included three Bacillus subtilis strains, a Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain, a Pantoea brenneri strain, and a Bacillus sp. strain. Furthermore, we identified grapevine cutting clones with strong resistance to three fungal pathogens: Botrytis cinerea, F. solani, and F. graminearum, by using the TIDRE protocol. The endophytic bacterial strains (Bacillus) isolated from the highly resistant grapevine clones confer significant antagonistic effects against the fungal pathogens. Compared to existing methods, TIDRE offers superior speed and efficiency, and great potential for advancing the development and utilization of beneficial endophytic resources in sustainable agriculture.

1. Introduction

The escalating global population has intensified demands for both the quantity and quality of agricultural production. In recent years, the increasing frequency and severity of plant diseases driven by climate change, agricultural intensification, and crop monoculture trends have posed significant threats to food security and sustainable agriculture [1,2]. Plant diseases cause estimated annual yield losses of 20–40% worldwide, with fungal and bacterial infections being particularly prominent [3]. While chemical pesticides have partially mitigated disease spread, their overuse has led to unintended consequences, including pathogen resistance, soil microbiome disruption, environmental contamination, and hazardous pesticide residues in crops [4,5,6]. Consequently, the development of eco-friendly and sustainable disease control strategies has become a priority in modern agriculture.

Plant endophytes, microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes) that colonize internal plant tissues without causing overt disease symptoms, have emerged as promising biocontrol agents [7,8]. Certain endophytes suppress pathogens through niche competition, antimicrobial metabolite production (e.g., chitinases and antibiotics), and induced systemic resistance (ISR) [8,9,10,11]. Compared to chemical pesticides, endophyte-based biocontrol offers targeted, environmentally benign, and resistance-resistant advantages [12,13]. However, conventional isolation methods (e.g., the large-scale isolation of endophytes, and screening and validation of target functional strains) suffer from inefficiency, lengthy procedures, and poor specificity in screening strains antagonistic to target pathogens [14]. In particular, methods like tissue imprinting primarily capture microorganisms adherent to tissue surfaces with limited access to the internal endophytic community, while enrichment-based isolation often lacks the specificity required to selectively enrich for antagonists against a particular pathogen. Moreover, endophytic community composition varies with host genotype, growth environment, and cultivation practices, complicating targeted strain discovery [15].

The origin of endophytes within a plant can be vertically transmitted and horizontally transmitted. Vertically transmitted endophytes (VTEs) refer to endophytes inherited from maternal plants via seeds or vegetative propagation, whereas horizontally transmitted endophytes refer to endophytes recruited from the environment during plant growth [8]. VTEs represents acquired heritable traits in plants and can be exploited in plant endophytic modification (PEM) practices for crop improvement [16,17]. However, the key components, include(1) the effective isolation of functional VTE strains with desired host traits and (2) the discovery and evaluation of plant resources harboring beneficial VTEs (or consortia) with specific functions, which have limited the widespread application of PEM technology.

To address these limitations, we have developed Targeted Identification of Plant Disease Resistant Endophytes (TIDRE), an innovative method system that integrates cultured endophyte isolation from plant tissues with pathogen-specific antagonism screening. Distinct from conventional tissue-based screening or dual-culture assays that often test isolated strains against pathogens after initial cultivation, the TIDRE protocol embeds the pathogen-specific selection pressure much earlier in the process. It achieves this by incorporating a direct plant tissue–pathogen confrontation assay, thereby enabling a more targeted and efficient enrichment of antagonistic endophytes right from the initial isolation stage. The TIDRE protocol optimizes key steps, including selective culture media, the plant tissue–pathogen confrontation assay, and pathogen–endophyte confrontation validation, thereby improving both isolation efficiency and screening accuracy. Key advantages over traditional methods include (1) reduced time and labor costs; (2) the rapid screening of highly active antagonistic strains against specific pathogens; and (3) the efficient screening of disease-resistant plant germplasm against defined pathogens. This study not only provides a novel tool for plant disease biocontrol but also lays a methodological foundation for exploiting endophytic resources and for future exploration of endophyte-based strategies in disease-resistant crop breeding or PEM technology.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pathogen Strains and Culture Media

The tested fungal pathogens included (1) Fusarium oxysporum (associated with Panax notoginseng root rot [18]), provided by the College of Plant Protection, Yunnan Agricultural University, and Botrytis cinerea, F. solani, and F. graminearum (causing gray mold [19] and root rot [20] in multiple crops), previously isolated and identified by our laboratory.

Fungal pathogens were cultured on potato dextrose agar medium (PDA): 200 g potato, 20 g dextrose, 15–20 g agar, and 1000 mL distilled water (natural pH). Bacterial endophytes were cultured on beef extract peptone agar medium (BEPA): 3 g beef extract, 10 g peptone, 5 g NaCl, 15–25 g agar, and 1000 mL distilled water (pH adjusted to 7.4–7.6).

2.2. Plant Materials

Pseudo-ginseng [Panax notoginseng (Burkill) F. H. Chen ex C. H.] leaf samples were collected from 3-year-old plants grown in the experimental field at Chenggong Campus of Yunnan University (24°49′54″ N, 102°51′8″ E). Fully expanded leaves were randomly sampled from the selected plants.

Grapevine materials were obtained from 2-year-old cuttings of the ‘Rose Honey’ cultivar (Vitis vinifera L. × V. labrusca L.), grown in the same experimental field. Leaves were sampled from 60-day-old grapevine cuttings. Specifically, fully expanded, intact young leaves were collected from the upper portion of cuttings at a consistent nodal position across multiple individual plants and different branches, with each cutting treated as an independent biological unit for analysis.

2.3. Sample Collection and Surface Sterilization

Healthy (showing vigorous growth without disease symptom) and weakened (showing vigorous growth without disease symptoms) 3-year-old pseudo-ginseng (Pg) plants were selected from the experimental field (3 plants per group, 6 plants total). One mature leaf per plant was randomly collected using sterile sampling bags, immediately placed on ice, and transported to the laboratory for processing.

The surface sterilization protocol consisted of the following [21]:

Rinsing leaves under running tap water for 10 min to remove debris;

Sequential treatment in Ultra-clean workbench (Shanghai, China);

70% ethanol (v/v) for 30 s;

Three rinses with sterile distilled water;

Disinfection with 3% NaClO for 1 min;

Rinsing five times with sterile distilled water to remove any residual sterilant;

Blotting on sterile filter paper to remove residual moisture.

Sterilization efficacy was verified by plating 100 μL of the final rinse water onto PDA medium, followed by 48 h incubation at 28 °C to confirm microbial absence.

To comprehensively isolate endophytic fungi from the leaf tissues, two distinct methods, the tissue segment method and the homogenate method, were employed. For the tissue segment method, surface-sterilized leaves were aseptically sectioned into 5 mm × 5 mm patches and evenly distributed along the periphery of PDA plates. To release more deeply embedded endophytes, the homogenate method was also used. Briefly, surface-sterilized leaves were ground into a fine homogenate using a sterile pestle and mortar with the addition of sterile distilled water. Appropriate dilutions (e.g., 10−1 and 10−2) of the homogenate were then spread-plated onto PDA plates [22]. For the subsequent dual-culture assays, a 5 mm diameter agar plug of F. oxysporum was inoculated at the center of each plate [16,23]. Three replicates were performed per leaf sample for each isolation method, with pathogen-only cultured plates serving as controls. All plates were incubated at 28 °C for 5 days.

Pathogen inhibition was quantified using the cross-diameter method:

2.4. Endophyte Isolation and Antagonistic Activity Assessment

Bacterial colonies exhibiting clear inhibition zones at the leaf patch margins were selectively transferred to fresh PDA plates using sterile technique. Pure cultures were obtained through streak plating [24] and preserved for subsequent analysis. For antagonism verification, purified endophytes were dual-cultured with F. oxysporum (2 cm separation distance) under identical conditions. After 7 days incubation at 28 °C, fungal colony diameters were measured to determine biocontrol efficacy, with three replicates per endophyte strain and pathogen-only cultured controls [25].

2.5. Molecular Identification of Antagonistic Strains

Genomic DNA was extracted from selected antagonistic bacterial strains using a Bacterial Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China). The 16S rDNA region was amplified via PCR with universal bacterial primers 27-F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492-R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) [26]. This was conducted in a 25 μL PCR system containing 12.5 μL 2 × Taq PCR Mix, 1 μL each forward/reverse primer, 1 μL DNA template, and 9.5 μL ddH2O. Amplification conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min; 32 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 45 s; and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were examined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using a PCR Product Purification Kit (Sangon Biotech), and quantified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Shanghai, China). Purified amplicons were subsequently submitted to Sangon Biotech for bidirectional Sanger sequencing. The forward and reverse sequences were assembled and trimmed using SeqMan (DNASTAR Lasergene v7.1) to obtain consensus sequences. Quality control was performed by removing low-quality bases (Q < 20) and ambiguous reads.

The obtained sequences were analyzed through BLAST against the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 8 August 2024) for preliminary taxonomic identification. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using MEGA 11.0 software, with evolutionary relationships inferred through the neighbor-joining method [27]. Bootstrap values were calculated from 1000 replicates to assess tree topology reliability.

2.6. Application of the TIDRE Method in Screening Endophyte-Based Disease-Resistant Grapevine Clones

To evaluate the potential of the TIDRE method for endophyte-based plant disease resistance breeding, we applied this method to screen grapevine germplasm using leaf samples from the ‘Rose Honey’ cultivar (Vitis vinifera L. × V. labrusca L.). Cutting vine clones were propagated from cuttings harvested from different individual plants and branches within the same vineyard to assess natural variation in disease resistance among these clones.

The experimental design comprised two main phases: (1) Dual-culture of vine leaf discs and 3 phytopathogenic fungi—B. cinerea, F. solani, and F. graminearum. The screening aimed to identify both pathogen-resistant plant lines and those exhibiting broad-spectrum resistance. (2) Endophytic antagonistic strains were subsequently isolated from highly resistant plants and evaluated for their efficacy against the same three pathogens.

All experiments were carried out with at least 3 biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM) (version 26.0). The normality of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was assessed with Levene’s test. For comparisons between two groups, Student’s t-test was applied. For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc tests followed by Dunn’s post hoc test was used. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Data visualization was performed using Microsoft Excel (version 2019) and Origin 2022 (version 2022).

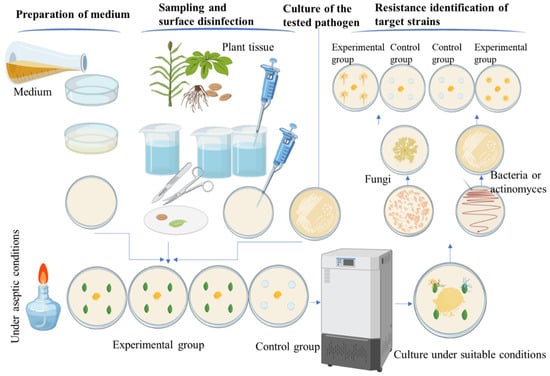

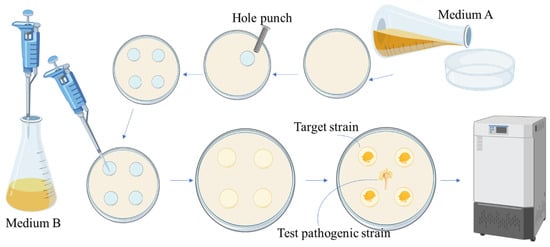

The operation process of the TIDRE protocol is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental operation of the TIDRE protocol (the main content includes two parts: rapid discovery and validation of disease-resistant endophytes).

3. Results

3.1. Rapid Discovery and Isolation of F. oxysporum Antagonistic Endophytes from Pseudo-Ginseng (Pg) Using TIDRE Protocol

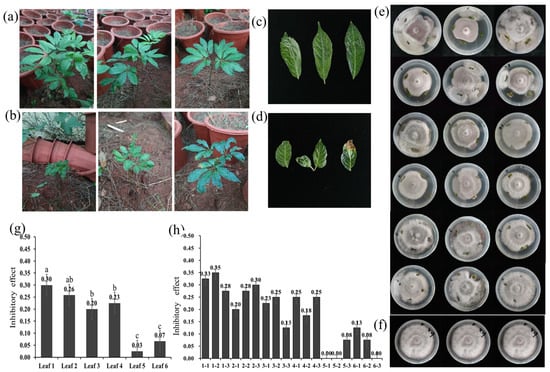

The health status of randomly sampled plants was evaluated, with detailed results presented in Table 1 and visually summarized in Figure 2 (Figure 2a–d). Subsequent dual-culture assays revealed that the majority of Pg leaf patches exhibited varying degrees of antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum (Figure 2e). A significant variation in antifungal efficacy was observed among leaves from different plants. The comprehensive inhibition rates for the tested groups were 30%, 26%, 20%, 23%, 3%, and 7%, respectively, while the inhibition rate for individual leaves ranged from 0% to 35%. The antagonistic potential of leaves appeared to vary with plant health status. Leaves from healthy plants (Leaf 1 and Leaf 2) showed a stronger suppressive effect on pathogen growth relative to leaves from diseased or stunted plants (Leaf 5 and Leaf 6) (Figure 2g,h) suggesting a possible link between plant vigor and leaf-associated antagonistic activity.

Table 1.

Sampling information of pseudo-ginseng leaves from plants with different health statuses.

Figure 2.

Isolation of F. oxysporum antagonistic endophytes from pseudo-ginseng leaves using the TIDRE protocol. (a) Representative healthy Pg plants under field conditions. (b) Representative diseased or stunted plants collected from the same field. (c) A healthy leaf sample selected for TIDRE processing. (d) A diseased or stunted leaf sample selected for comparison. (e) Dual-culture assays showing the interaction between surface-sterilized Pg leaf patches in different health conditions and F. oxysporum on PDA plates after 5 days of incubation at 28 °C (Three independent biological replicates were performed for each leaf.). (f) Control plate with F. oxysporum cultured alone under the same conditions. (g,h): Quantitative analysis of the inhibitory effect of leaf-associated microbes on F. oxysporum mycelial growth. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three biological replicates. Different lowercase letters above the bars denote statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.2. Validation of Antagonistic Effects and Molecular Identification of Candidate Endophytes Against F. oxysporum

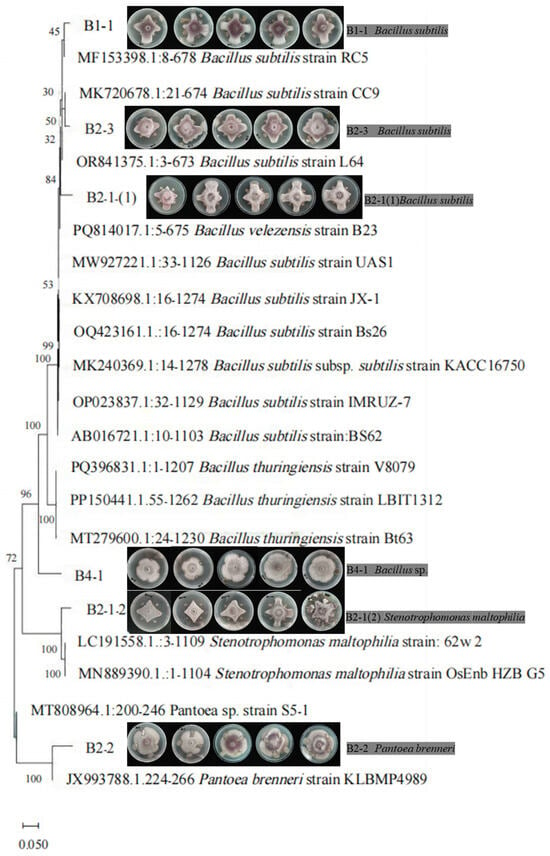

Using the TIDRE method, we isolated and purified 10 candidate bacterial strains that emerged from the marginal zones of resistant Pg leaf patches. Dual-culture assays with F. oxysporum revealed that six strains (60%) exhibited significant antagonistic effects (Figure 3). This high discovery rate demonstrates the efficacy of our method compared to conventional methods. Recent advances in plant endophyte research have established antagonistic endophytes as valuable resources for developing biocontrol agents. However, traditional screening methods show markedly lower efficiency: Ma et al. isolated 1000 endophytic bacteria from five Pg tissues, with only 104 strains (10.4%) showing antagonism against major root rot pathogens (F. oxysporum, Ralstonia sp., or Meloidogyne hapla) [28]. El-Hasan et al. identified just 46 antagonistic strains (12.9%) among 357 fungal endophytes from Solanum plants against Phytophthora infestans [29]. The significantly higher success rate (60%) achieved through TIDRE highlights its superior efficiency and accuracy in discovering functional endophytes for crop protection. This advancement addresses a critical bottleneck in biocontrol research by improving screening efficiency, reducing labor-intensive isolation procedures, and enhancing the discovery of potential endophytic agents. Phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rDNA sequencing revealed that the antagonistic strains comprised three strains of B. subtilis, one of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, one of Pantoea brenneri, and one of Bacillus sp. (Figure 2). Significantly, Bacillus species dominated the antagonistic isolates (4/6), consistent with this genus’s well-documented broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties and environmental adaptability.

Figure 3.

Validating the inhibitory efficacy and taxonomic characterization of candidate bacterial strains isolated from Pg leaves against the growth of F. oxysporum.

3.3. Application of the TIDRE Method in Screening Endophyte-Based Disease-Resistant Grapevine Resources

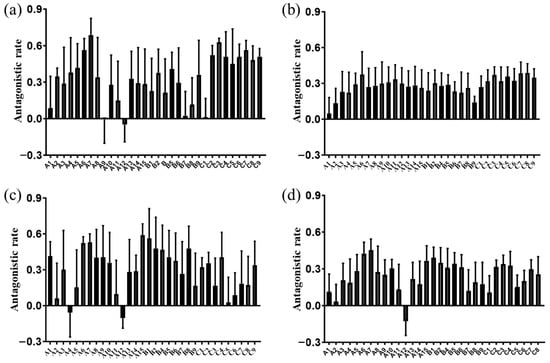

All tested grapevine cutting leaves exhibited antagonistic effects against F. solani, with most showing inhibitory activity against B. cinerea and F. graminearum (Figure 4, Table 2). We successfully identified multiple disease-resistant grapevine cutting clones (A6, A7, A15, B1, and B2) from 2-year-old ‘Rose Honey’ plants, demonstrating significant antagonistic effects against three phytopathogens (B. cinerea, F. solani, and F. graminearum) (Table 2). These vine cutting lines represent valuable plant resources for breeding programs aimed at enhancing resistance to these pathogens. Furthermore, three endophytic bacterial strains with broad-spectrum antagonistic activity were isolated from high-resistance grapevine clones: Bacillus sp. YIM 75779, B. subtilis, and Bacillus sp. (Table 3). These strains exhibit potential for development as biocontrol agents or as sources of antimicrobial compounds. Collectively, these findings provide a foundation for future research into breeding crop lines with endophyte-mediated resistance and for developing broad-spectrum botanical fungicides.

Figure 4.

Screening of disease-resistant grapevine cutting clones against various pathogens using the TIDRE protocol. Antagonistic activity of individual grape leaves on the growth of pathogenic fungi: (a) B. cinerea; (b) F. solani; and (c) F. graminearum. (d) Comparative antagonistic effects against all three pathogens. In the figure, the same letter indicates samples collected from different experimental plots (e.g., A, B, and C), while the numeric suffix denotes distinct individual plants within the same plot (e.g., A1, A2, …, and A15). The same labeling convention applies hereafter.

Table 2.

Average inhibition rates of different grapevine cuttings against three pathogenic fungi and the screening of cuttings with varying resistance.

Table 3.

Inhibition rates of antagonistic strains isolated from disease-resistant grapevine cuttings against three pathogenic fungi.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Widespread Association Between Endophytes and Antipathogen Activity: Underlying Mechanisms in Host Plants

The consistent suppression of pathogenic hyphal growth by Pg leaf materials is likely attributable to the synergistic activity of constitutive plant metabolites with antimicrobial properties—such as phenolics, flavonoids, and alkaloids—and the community of antagonistic endophytes residing within these tissues. Supporting this, Trichoderma gamsii YIM PH30019, isolated from healthy Pg rhizomes, has been shown to effectively control root rot disease through the production of volatile organic compounds, including dimethyl disulfide and dibenzofuran, which exhibit antagonism against several Pg-associated pathogenic fungi [30]. Similarly, the endophyte Arcopilus aureus, obtained from Pg, along with its extracts, demonstrates broad antifungal activity against pathogens such as F. graminearum and B. cinerea. This activity is associated with a diverse suite of bioactive compounds, ranging from alkaloids and flavonoids to organic acids and plant growth regulators, underscoring the potential of such endophytes as resources for developing novel antifungal agents [31].

A further layer of complexity arises from the fact that a substantial proportion of plant endophytes are cultivation-recalcitrant (CR) and thus escape detection by conventional isolation methods. These unculturable endophytes are increasingly recognized as critical players in plant disease resistance, with much of their biosynthetic potential remaining latent under laboratory conditions [32]. Environmental sequencing studies reveal that CR microorganisms dominate natural plant-associated communities, yet fewer than 1% are readily cultivable [33]. Practical evidence further indicates that disease suppression is often more effectively achieved by complex, unculturable microbial consortia—as seen in treatments with crude leaf slurries—than by individual cultured isolates [34]. Additionally, functional metagenomic approaches, such as those applied to Salvia miltiorrhiza root systems, have decoded hidden metabolic pathways and enzymatic repertoires essential for plant–microbe interactions, providing a genetic basis for the activity of non-culturable communities [35]. These insights help explain why, in the present study, certain Pg leaf samples inhibited F. oxysporum hyphal growth in the absence of visible colony formation, pointing to contributions from either plant-derived metabolites or the cryptic activity of non-culturable endophytes.

Bacillus is an important contributor to antagonistic endophyte resources. This observation aligns with previous reports demonstrating Bacillus prevalence among functional endophytes, including (1) Ma et al.’s identification of B. amyloliquefaciens as the dominant antagonistic species against Pg root rot pathogens [28]; (2) B. subtilis R31’s capacity to modulate rhizosphere microbiomes for sustained banana wilt suppression [36]; (3) multiple antagonistic Bacillus species (B. paricheniformis, B. tequilensis, and B. velezensis) isolated from quinoa [23]; and field-validated biocontrol agents like Bacillus K-9 showing 70.39% inhibition against potato common scab while enhancing yield [37]. Particularly noteworthy is B. halotolerans’ dual functionality as both biofertilizer and biocontrol agent in arid ecosystems [38]. These collective findings underscore Bacillus endophytes as ubiquitous phytoprotective resources with exceptional potential for agricultural applications, warranting prioritized investigation in microbial biocontrol development.

4.2. Variation in Disease Resistance Exists Among Individual Plants

The variability in antagonistic effects among leaf samples may be linked to the health status of the host plant. Healthier plants typically harbor more diverse and functionally robust endophytic assemblages, often referred to as the plant microbiome, which enhance host adaptability and pathogen resistance [39]. Comparative metagenomic analyses of resistant versus susceptible tomato plants, for instance, revealed a markedly higher abundance of a protective Flavobacterium strain in the rhizosphere of resistant individuals [40]. By analogy, healthy Pg leaves may sustain richer populations of antagonistic bacteria or fungi—such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, or Trichoderma—that suppress pathogens through mechanisms including niche competition, antibiotic production, or induction of systemic resistance [41]. In contrast, pathogen invasion can disrupt this microbial balance, leading to dysbiosis and a reduction in protective functions. Moreover, sustained pathogen stress may interfere with the plant’s own metabolic homeostasis, impairing the accumulation of key defensive compounds such as phenolics and flavonoids [42]. Finally, the outcome of endophyte–pathogen interactions may depend on specific inhibitory strategies—such as the secretion of cell wall-degrading enzymes like chitinases [43]—employed by dominant endophytes in healthy tissues, whereas in infected leaves, protective microbes may be outcompeted or suppressed by the pathogen. Collectively, these findings point to a potential role of plant health in modulating endophyte-mediated resistance; however, the sample size in this preliminary comparison (three plants per health category) may not fully capture the underlying biological variability. This limitation warrants consideration when interpreting the observed trends, and further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to confirm and generalize the relationship.

The observed variation in disease resistance among cuttings may result from multiple factors. Firstly, natural variations in secondary metabolites (e.g., polyphenols, terpenoids, and defense proteins) have an influence on antimicrobial spectra [44], as demonstrated by Ma et al. regarding organic acid-mediated chemotaxis of antagonistic endophytes in Pg [45]. Secondly, the host-specific adaptation mechanisms may regulate pathogen susceptibility. Kerwin et al. demonstrated that natural polymorphisms in glucosinolate (GSL) genes affect environmental adaptability, though this pattern fluctuates significantly. Genotypes showing high fitness in one trial exhibited reduced performance in others, with no consistently superior GSL genotype [46]. This phenomenon aligns with O’Brien et al.’s findings that distinct root microbiomes develop even in identical soils due to rapid host–microbe co-adaptation [47]. In addition, environmental factors (e.g., light intensity and temperature fluctuations) may modulate the accumulation of plant defense-related compounds, thereby regulating the antimicrobial activity of plant tissues [48]. Collectively, these mechanisms could account for the observed variations in pathogen susceptibility among individual grapevine leaves in this study. The grapevine cuttings originated from a single variety of homogeneous vineyards, minimizing genetic variation and thereby enhancing the likelihood of harboring disease-resistant endophytes. Studies have shown that genetic uniformity promotes consistent root exudate profiles that selectively enrich functional microbiota [49], reducing variability in host–microbe interactions. This effect enables specific beneficial microbe–host combinations to be stably maintained, providing a robust foundation for TIDRE-based screening of disease-resistant plant resources.

4.3. Future Directions: Innovation and Optimization of the TIDRE Method

Conventional methods for screening antagonistic endophytes are often labor-intensive and inefficient, as they require the isolation and cultivation of a broad microbial community prior to bioassay. The TIDRE method presented here addresses these limitations by integrating a preliminary tissue-level antagonistic assay with targeted endophyte isolation. This method offers several key advantages (Table 4): it significantly reduces workload and experimental time by focusing only on tissues exhibiting antagonistic activity; it enhances the specificity of isolated endophytes against the target pathogen; and it provides a direct functional readout of tissue resistance. These features make TIDRE a promising tool for both biocontrol agent discovery and resistance breeding programs. To broaden its application, future work should focus on optimizing culture conditions and validating the method across diverse plant–pathogen systems.

Table 4.

The innovations of this method compared with the existing conventional method.

A recognized constraint in antagonism assays, including the standard TIDRE setup, is the potential bias introduced by differing microbial growth rates on a single medium. To overcome this, we propose an optimized TIDRE system employing a partitioned plate design with multiple tailored media (Figure 5, Table 5). This modification ensures balanced growth for both pathogen and target endophyte types, leading to a more reliable assessment of antagonistic potential. The inherent flexibility of this design also allows for future adaptation to study multi-strain interactions and integration into higher-throughput screening platforms.

Figure 5.

Optimizing the TIDRE technical system through different combinations of culture media. Medium preparation procedure: The prepared optimal medium for the test pathogen was poured into Petri dishes. After solidification, four wells were created at 2 cm from the center using a sterile hole punch, and the removed agar blocks were discarded. The optimal medium for target strains was then pipetted into the wells and allowed to solidify before use.

Table 5.

Culture techniques for isolating different types of endophytes (medium mix).

5. Conclusions

This study developed an innovative TIDRE (Targeted Identification of Plant Disease-resistant Endophytes) method, which integrates culturable endophyte isolation from plant tissues with antagonistic microbe screening against phytopathogens. Using pseudo-ginseng as a model, we successfully identified a group of endophytic bacterial strains exhibiting antagonistic activity against F. oxysporum. Furthermore, this protocol enabled efficient screening of grapevine lines with enhanced disease resistance from cutting-derived populations, suggesting its potential dual applicability in both microbial resource discovery and plant endophytic modification (PEM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-Y.H., P.Z. and M.-Z.Y.; methodology, P.Z., W.S.M., L.-R.G. and Y.-N.Z.; software, S.-C.G. and L.-R.G.; validation, P.Z. and W.S.M.; formal analysis, H.-Y.H. and P.Z.; investigation, P.Z. and W.S.M.; resources, W.S.M. and S.-C.G.; data curation, S.-C.G. and L.-R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-Y.H.; writing—review and editing, H.-Y.H. and M.-Z.Y.; visualization, H.-Y.H. and P.Z.; supervision, X.-H.H. and M.-Z.Y.; project administration, X.-H.H. and M.-Z.Y.; funding acquisition, M.-Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32360255 and 32471746, and Yunnan provincial key S&T special project, grant number 202102AE090042.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TIDRE | Targeted Identification of Disease-resistant Endophytes |

| VTEs | Vertically transmitted endophytes |

| PEM | Plant endophytic modification |

| PDA | Potato dextrose agar medium |

| BEPA | Beef extract peptone agar medium |

| CR | Cultivation-recalcitrant |

| GSL | Glucosinolate |

References

- Gai, Y.; Wang, H. Plant Disease: A Growing Threat to Global Food Security. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The Global Burden of Pathogens and Pests on Major Food Crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The State of Food and Agriculture 2021|FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/1457036/ (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, Environment, and Food Safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Sidhu, G.P.S.; Handa, N.; Kohli, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Bali, A.S.; Parihar, R.D.; et al. Worldwide Pesticide Usage and Its Impacts on Ecosystem. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Hawkins, N.J.; Sanglard, D.; Gurr, S.J. Worldwide Emergence of Resistance to Antifungal Drugs Challenges Human Health and Food Security. Science 2018, 360, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compant, S.; Samad, A.; Faist, H.; Sessitsch, A. A Review on the Plant Microbiome: Ecology, Functions, and Emerging Trends in Microbial Application. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 19, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Geng, S.; Zhu, Y.; He, X.; Pan, X.; Yang, M. Seed-Borne Endophytes and Their Host Effects. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusari, P.; Kusari, S.; Spiteller, M.; Kayser, O. Endophytic Fungi Harbored in Cannabis Sativa L.: Diversity and Potential as Biocontrol Agents against Host Plant-Specific Phytopathogens. Fungal Divers. 2012, 60, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Parmar, S.; Sharma, V.K.; White, J.F. Seed Endophytes and Their Potential Applications. In Seed Endophytes; Verma, S.K., White, J.F., Jr., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Krishnan, G.V.; Thankappan, D.; Bhaskaran Nair Saraswathy Amma, D.K. 4-Endophytic Bacterial Strains Induced Systemic Resistance in Agriculturally Important Crop Plants. In Microbial Endophytes; Kumar, A., Radhakrishnan, E.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 75–105. ISBN 978-0-12-819654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Brettell, L.E.; Qiu, Z.; Singh, B.K. Microbiome-Mediated Stress Resistance in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.E.; Park, J.M. Endophytic Bacteria as Biocontrol Agents against Plant Pathogens: Current State-of-the-Art. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 10, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.X.; Guo, X.; Qin, Y.; Garrido-Oter, R.; Schulze-Lefert, P.; Bai, Y. High-Throughput Cultivation and Identification of Bacteria from the Plant Root Microbiota. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 988–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foo, J.L.; Ling, H.; Lee, Y.S.; Chang, M.W. Microbiome Engineering: Current Applications and Its Future. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 12, 1600099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.X.; Guo, L.R.; Wang, Y.T.; Wen, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.X.; Zhou, P.; Huang, S.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Pan, X.X.; et al. Targeted Manipulation of Vertically Transmitted Endophytes to Confer Beneficial Traits in Grapevines. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Chen, C.X.; Liao, C.M.; Li, T.; Pan, X.X.; Zhu, S.S.; Yang, M.Z. Dominated “Inheritance” of Endophytes in Grapevines from Stock Plants via In Vitro-Cultured Plantlets: The Dawn of Plant Endophytic Modifications. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-N.; Chen, C.-J.; Li, Q.-Q.; Xu, F.-R.; Cheng, Y.-X.; Dong, X. Monitoring Antifungal Agents of Artemisia Annua against Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium solani, Associated with Panax notoginseng Root-Rot Disease. Molecules 2019, 24, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Ran, L.; Ge, B. Effect of Combining Wuyiencin and Pyrimethanil on Controlling Grape Gray Mold and Delaying Resistance Development in Botrytis cinerea. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima Cruz, J.M.F.; de Farias, O.R.; Araújo, B.C.L.; Rivera, A.V.; de Souza, C.R.; de Souza, J.T. A New Root and Trunk Rot Disease of Grapevine Plantlets Caused by Fusarium in Four Species Complexes. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-Y.; Wen, Y.; Geng, S.-C.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Zhao, Y.-B.; Pan, X.-X.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; He, X.-H.; Yang, M.-Z. Diversity and Function Potentials of Seed Endophytic Microbiota in a Chinese Medicinal Herb Panax notoginseng. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juyal, P.; Jabi, S.; Kumar, R.; Thapa, M.; Bijalwanb, A.; Rawat, A.; Rudiyal, U.; Gaurav, N. Isolation and Identification of Bacterial and Fungal Edophytes from Leaves and Stems of H. rosa-sinensis and Production of Secondary Metabolites from Isolated Endophytes. Uttar Pradesh J. Zool. 2023, 44, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Shen, S.; Hu, R.; Li, W.; Wang, J. Screening, Identification, and Growth Promotion of Antagonistic Endophytes Associated with Chenopodium quinoa against Quinoa Pathogens. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 1839–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, M.; Bhatta, B.P.; Malla, S. Isolation and Characterization of Bacteria Associated with Onion and First Report of Onion Diseases Caused by Five Bacterial Pathogens in Texas, USA. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 1721–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, S.; Peng, L.; Fan, G.; Kang, H. Isolation of Antagonistic Endophytic Fungi from Postharvest Chestnuts and Their Biocontrol on Host Fungal Pathogens. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.-H.; Ha, S.-M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing EzBioCloud: A Taxonomically United Database of 16S rRNA Gene Sequences and Whole-Genome Assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, H.; Li, S.; Shang, W.; Jiang, J.; Xu, X.; Liu, D.; Hu, X. Diversity of Fungal Endophytes in American Ginseng Seeds. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2784–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Cao, Y.H.; Cheng, M.H.; Huang, Y.; Mo, M.H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.Z.; Yang, F.X. Phylogenetic Diversity of Bacterial Endophytes of Panax notoginseng with Antagonistic Characteristics towards Pathogens of Root-Rot Disease Complex. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2013, 103, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Hasan, A.; Ngatia, G.; Link, T.I.; Voegele, R.T. Isolation, Identification, and Biocontrol Potential of Root Fungal Endophytes Associated with Solanaceous Plants against Potato Late Blight (Phytophthora infestans). Plants 2022, 11, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-L.; Sun, S.-Z.; Miao, C.-P.; Wu, K.; Chen, Y.-W.; Xu, L.-H.; Guan, H.-L.; Zhao, L.-X. Endophytic Trichoderma gamsii YIM PH30019: A Promising Biocontrol Agent with Hyperosmolar, Mycoparasitism, and Antagonistic Activities of Induced Volatile Organic Compounds on Root-Rot Pathogenic Fungi of Panax notoginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2016, 40, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, R.; Liu, F.; Guo, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, F.; Lei, L. Identification and Application of an Endophytic Fungus Arcopilus aureus from Panax notoginseng against Crop Fungal Disease. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1305376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, S.A.; Brown, A.M.V. Deep Learning Approaches for Natural Product Discovery from Plant Endophytic Microbiomes. Environ. Microbiome 2021, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-G.; Guo, S.-J.; Wang, W.-N.; Wei, G.-X.; Ma, G.-Y.; Ma, X.-D. Diversity and Bioactivity of Endophytes from Angelica sinensis in China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, G.; Amend, A.S. Foliar Microbiome Transplants Confer Disease Resistance in a Critically-Endangered Plant. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.; Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, Z. Different Techniques Reveal the Difference of Community Structure and Function of Fungi from Root and Rhizosphere of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Plant Biol. 2023, 25, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Chen, H.; Huang, A.; Zheng, L.; Li, C.; Qin, D.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z.; Fu, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Modulation of Rhizosphere Microbiota by Bacillus subtilis R31 Enhances Long-term Suppression of Banana Fusarium Wilt. iMetaOmics 2025, 2, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, M.; Wang, Y.; Teng, W.; Jin, G. Isolation and Identification of an Endophytic Bacteria Bacillus sp. K-9 Exhibiting Biocontrol Activity against Potato Common Scab. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, H.B.; Cherif-Silini, H.; Chenari Bouket, A.; Qader, M.; Silini, A.; Yahiaoui, B.; Alenezi, F.N.; Luptakova, L.; Triki, M.A.; Vallat, A.; et al. Screening for Fusarium Antagonistic Bacteria from Contrasting Niches Designated the Endophyte Bacillus halotolerans as Plant Warden against Fusarium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Leach, J.E.; Tringe, S.G.; Sa, T.; Singh, B.K. Plant–Microbiome Interactions: From Community Assembly to Plant Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 607–621, Correction in Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 72. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-00490-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.-J.; Kong, H.G.; Choi, K.; Kwon, S.-K.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, P.A.; Choi, S.Y.; Seo, M.; Lee, H.J.; et al. Rhizosphere Microbiome Structure Alters to Enable Wilt Resistance in Tomato. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1100–1109, Correction in Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 1117. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1118-1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, I.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; Raičević, V.; Jovičić-Petrović, J.; Muller, D. Microbial Diversity in Soils Suppressive to Fusarium Diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1228749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, D.; Pal, S.; Singh, S. Plant Secondary Metabolites in Defense against Phytopathogens: Mechanisms, Biosynthesis, and Applications. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 138, 102639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Yong, B.; He, B. Identification of Chitinase from Bacillus velezensis Strain S161 and Its Antifungal Activity against Penicillium digitatum. Protein Expr. Purif. 2024, 223, 106562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerband, A.C.; Funk, J.L.; Barton, K.E. Intraspecific Trait Variation in Plants: A Renewed Focus on Its Role in Ecological Processes. Ann. Bot. 2021, 127, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, W.-Q.; Shi, R.; Zhang, X.-M.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.-S.; Mo, M.H. Effects of Organic Acids on the Chemotaxis Profiles and Biocontrol Traits of Antagonistic Bacterial Endophytes against Root-Rot Disease in Panax notoginseng. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2021, 114, 1771–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerwin, R.; Feusier, J.; Corwin, J.; Rubin, M.; Lin, C.; Muok, A.; Larson, B.; Li, B.; Joseph, B.; Francisco, M.; et al. Natural Genetic Variation in Arabidopsis thaliana Defense Metabolism Genes Modulates Field Fitness. eLife 2015, 4, e05604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, A.M.; Harrison, T.L. Host Match Improves Root Microbiome Growth. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1103–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-Q.; Dudareva, N. Plant Specialized Metabolism. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R473–R478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalnina, K.; Louie, K.B.; Hao, Z.; Mansoori, N.; da Rocha, U.N.; Shi, S.; Cho, H.; Karaoz, U.; Loqué, D.; Bowen, B.P.; et al. Dynamic Root Exudate Chemistry and Microbial Substrate Preferences Drive Patterns in Rhizosphere Microbial Community Assembly. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.