Abstract

Accurate detection of cattle and sheep is a core task in precision livestock farming. However, the complexity of agricultural settings, where visible light images perform poorly under low-light or occluded conditions and infrared images are limited in resolution, poses significant challenges for current smart monitoring systems. To tackle these challenges, this study aims to develop a robust multimodal fusion detection network for the accurate and reliable detection of cattle and sheep in complex scenes. To achieve this, we propose YOLO-MSLT, a multimodal fusion detection network based on YOLOv10, which leverages the complementary nature of visible light and infrared data. The core of YOLO-MSLT incorporates a Cross Flatten Fusion Transformer (CFFT), composed of the Linear Cross-modal Spatial Transformer (LCST) and Deep-wise Enhancement (DWE), designed to enhance modality collaboration by performing complementary fusion at the feature level. Furthermore, a Content-Guided Attention Feature Pyramid Network (CGA-FPN) is integrated into the neck to improve the representation of multi-scale object features. Validation was conducted on a cattle and sheep dataset built from 5056 pairs of multimodal images (visible light and infrared) collected in the Manas River Basin, Xinjiang. Results demonstrate that YOLO-MSLT performs robustly in complex terrain, low-light, and occlusion scenarios, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 91.8% and a precision of 93.2%, significantly outperforming mainstream detection models. This research provides an impactful and practical solution for cattle and sheep detection in challenging agricultural environments.

1. Introduction

Intelligent precision farming technology is essential for improving farm operations’ efficiency and fostering the superior growth of the livestock sector in the current environment of steady economic expansion and industrial modernization [1,2]. Accurate herd detection facilitates scientific decision-making and improves economic efficiency, while contributing to grassland ecological balance and promoting the sustainable development of the local economy. Livestock production significantly contributes to agricultural GHG emissions [3,4], with livestock respiration, rumen activity and manure decomposition emitting methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) [5]. Under the free-range grazing model, diverse environmental and management conditions hinder accurate monitoring of animal distribution and numbers, introducing uncertainty in GHG emission estimates. With growing population, urbanization, and resource constraints, the livestock sector must adopt precision management to enhance productivity and reduce emissions [6]. Recently, smart devices and AI have become integral to precision animal husbandry, enabling improved productivity and reduced environmental impact [7]. In this context, efficient and accurate access to agricultural animal information is key to promoting precision animal husbandry.

Currently, there are three ways to collect livestock data: through hardware [8], image- or video-based techniques [9], or a combination of both methods [10]. When monitoring with hardware, animals are tagged and equipped with sensors [11] or fitted with a smart collar with GPS capacity [12]. The stress of so-wearing equipment might potentially harm an animal’s health and growth. Also, RFID has a low read range and may suffer data loss or bias in the case of device failures or displacement of collars [13]. Furthermore, in areas of large-scale grazing, the practicality of equipping each animal with hardware is severely hindered due to high cost and intensive maintenance.

Thus, livestock detection using deep learning, suitable for complex grazing environments, has proven to be a practical, non-invasive solution, thus avoiding stress and welfare concerns raised by wearables. Recent advances further optimize vision-based detection. Yang et al. [14] reported on efficient cattle detection by fusing deformable convolution with coordinate attention into the YOLOv8 model. Wang et al. [15] proposed a Faster CNN method for exact detection of dairy goats in video surveillance. Riekert et al. [16] gave a deep learning setup for 2D image-based pose and position identification measures, with an average precision of 87.4%. Shao et al. [17] presented a CNN-based method for livestock identification and tallying with a recall of 0.946. Although deep learning methods have given good results in the detection of animals, it is still challenging to identify livestock in complex grazing environments, especially with multiple subjects, occlusion, and poor lighting conditions [18]. The conventional RGB technique for detection involves deep learning for visual attributes such as shape, size, and color [19,20]. Though RGB images present high resolutions and texture information under good lighting, they are significantly degraded under low light or backlight scenarios. In contrast, infrared images provide steady thermal information in dark conditions [21,22], but they lack color and texture details; therefore, alone they are not sufficient for accurate detection. Accordingly, this study attempted to fuse both RGB and infrared modalities for detection robustness that can operate under various scenarios of lighting and occlusion.

In RGB-infrared multimodal cattle and sheep detection, the crucial issues are information alignment and feature extraction. Considering the mutual benefits that RGB and infrared imagery can lend, three basic combinations are generally observed: fusion at pixel level [23], fusion at feature level [24], and fusion at decision level [25]. If one wishes to maximize the pixel fusion effect, it generally tries to combine image data from different modalities with the information of equipment for the detection [26,27]. Hence, it either serves an estimation purpose or displays the picture with enhanced clarity, although an increase in computational costs will result. Decision-level fusion takes place after separate processing and analysis of each modality with the aim of increasing the overall robustness of decision-making [25,28]. Li et al. [29] proposed a decision-level cattle identification framework based on multi-feature fusion, integrating facial features, muzzle patterns, and ear tags to alleviate misidentification caused by mutual occlusion in complex farming scenarios. Despite its effectiveness, the reliance on decision-level fusion and task-specific feature extraction hinders unified feature learning and real-time end-to-end deployment in complex scenarios. For instance, the Soft Consistency Correlation Filter (SCCF) [30] enhances decision robustness and computational efficiency simultaneously. On the other hand, the decision-level-only operation fails to adequately utilize the cross-modal complementarity and hence limits detection accuracy. In contrast, feature-level fusion shows better performance in multimodal target detection as it builds on the features extracted from each modal data [31,32] to enrich the expressiveness and deepen the features. The major task is the deep learning part of it, with typical models including MCNN [33] and CSRNet [34]. MCNN works with various kernel sizes to extract multiscale features, then merges them by 1 × 1 convolution to enhance livestock detection. CSRNet, conversely, progressively optimizes the target features from low to high resolution through a density map refinement strategy to improve detection accuracy and scale the network. Fan et al. [35] proposed CMFNet, which integrates RGB and near-infrared (NIR) imagery for precise weed and crop mapping, showing that attention-based cross-modal interaction significantly improves segmentation accuracy. Similarly, Hou et al. [36] introduced a dual-branch infrared-visible fusion network based on YOLOv5-s, incorporating modality-specific attention and multi-scale feature fusion, achieving substantial detection accuracy gains on KAIST, FLIR, and GIR datasets. However, these approaches generally rely on high-quality, well-aligned multi-modal image pairs and may face challenges in complex backgrounds, noisy environments, or with small and densely packed targets, highlighting the need for more robust and adaptive multimodal fusion strategies.

With the evolution of Transformer variants [37], such as ViT [38] and many more, processing multimodal data has improved drastically, especially for cross-modal interaction tasks like fusion between RGB and infrared images. Initial early concatenation schemes would concatenate multimodal features and input them into the Transformer encoder [39,40,41]. This approach eases the fusion between different modalities and helps the model to best exploit the synergy that the multimodal elements provide. Cross-attention mechanisms are built upon attention weights to share information from one modality to another [42,43,44], and thus allow richer associations. Despite the good performance of Transformer architectures on multimodal tasks, they can pose essential problems from the computational perspective. These become obvious mainly when it is a matter of large sequence lengths or a large number of modalities, making both training and evaluation a very slow procedure. This is mainly because attention has to be computed at every position, thus resulting in high time complexity. Hence, identifying a more efficient Transformer variant and an optimization method is of great importance in real-world applications. Araújo et al. [45] demonstrated that integrating the CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) mechanism into the YOLOv8 model effectively enhances its generalization ability and detection accuracy, achieving an mAP of 82.6%. The core idea of CBAM, which involves decoupling and separately modeling channel and spatial information, has been adopted by some efficient linear Transformer variants. However, this research was solely based on visible light (RGB) imagery, failing to address the challenges posed by extreme complex environments such as nighttime, dense fog, or low-light conditions.

To overcome the above challenges and achieve the research goal of accurate and reliable detection of cattle and sheep in complex scenarios, we introduce YOLO-MSLT, a novel multimodal fusion architecture based on YOLOv10, aimed at detecting cattle and sheep under various adverse conditions, including low-light environments and dense shrubbery, occlusion among same-type targets, occlusion among different-type targets, inclement weather such as rain or snow, complex mountainous terrains, and long-range small targets. The heart of YOLO-MSLT is the Cross Flatten Fusion Transformer (CFFT), which consists of the Linear Cross-modal Spatial Transformer (LCST) and the Depth-Wise Enhancement (DWE) module. This choice is made to maximize parameter efficiency and to enhance the fusion quality, especially under night dim-lighting. To support small-target perception, a Content-Guided Attention Feature Pyramid Network (CGA-FPN) is proposed to adaptively fuse low-level details with high-level semantics, thereby vastly improving detection accuracy in dense prediction.

Major contributions of this work include the following:

- The work proposes a multimodal fusion network, YOLO-MSLT, based on the spatial linear transformer, which allows efficient collaboration of RGB and infrared modalities to detect cattle and sheep in complex scenes with precision.

- Our prime innovation resides in the CFFT module, which performs efficiently in cross-modal feature interaction and deep feature enhancement, thereby drastically enhancing object detection performance under variably difficult conditions.

- We evaluated our method on the self-constructed multi-modal cattle and sheep dataset MRDS, and compared it with the advanced fusion modules CSCA and CFT.

- Our technique exhibits a high level of both accuracy and efficiency, indicating its efficacy for reliable livestock detection in complex environments within Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

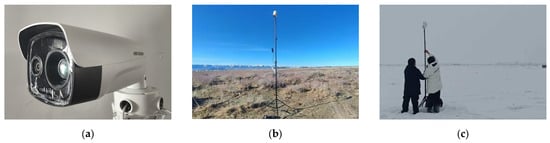

The study’s experimental location is situated within a mountainous terrain near the Manas River in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (latitude 43.96° N–44.58° N, longitude 85.89° E–86.13° E). This region serves as a key grazing area for local herders and is characterized by complex terrain, with abundant shrubs and woodlands that often cause visual occlusions. A Hikvision multi-modal camera (model DS-2TD2667-35/P, Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) was employed for image acquisition, and its detailed specifications are presented in Table 1. Figure 1 provides an overview of the experimental setup and field data collection. A close-up of the Hikvision multi-modal camera is shown in Figure 1a, while Figure 1b illustrates the camera deployed at the experimental site. Figure 1c depicts the research team collecting data in a snow-covered, complex livestock environment, highlighting the challenges posed by low illumination and adverse weather conditions.

Table 1.

Main Specifications of the Hikvision DS-2TD2667-35/P Camera.

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental setup and field data collection. (a) Close-up of the Hikvision multi-modal camera (model DS-2TD2667-35/P) used in the experiments. (b) The Hikvision multi-modal camera deployed at the actual experimental site. (c) The research team collecting the dataset in a snow-covered, complex livestock environment.

The camera has a horizontal field of view of 17.67°, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the target area without blind spots. In terms of thermal imaging, precise sensitivity adjustments were performed, achieving a noise equivalent temperature difference (NETD) of ≤35 mK. This significantly enhanced the system’s ability to detect low-temperature targets during nighttime. The multi-modal cameras were mounted at five different heights—5 m, 9 m, 13 m, 17 m, and 21 m above ground level—in order to capture cattle and sheep features at various spatial scales and viewing angles. Data collection was performed in spring, summer, autumn, and winter to capture varying daylight hours, with an emphasis on low-light data capture. The seasonal variety in the dataset seeks to capture variations in the environment through the entire year so as to make the model versatile for real-world applications.

2.2. Dataset Construction

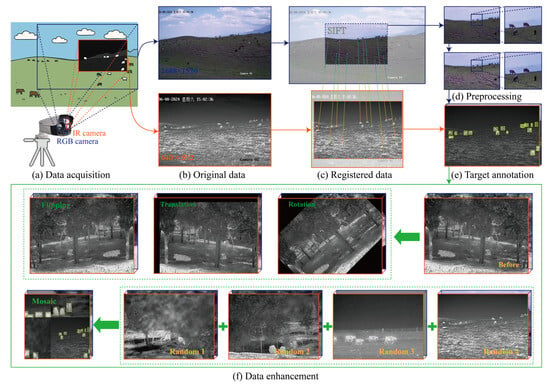

Figure 2 illustrates the entire flow of multimodal image processing. The study prioritizes multi-modal image registration tasks with the SIFT [46] algorithm. SIFT finds extrema in the scale space and then builds feature descriptors with a high degree of invariance, thereby enabling robust matching despite changes in scale, rotation, and illumination. Keeping in view registration efficiency, the complementary technique called Oriented FAST and Rotated BRIEF (ORB) [47] has been used. ORB combines a fast feature detector with binary descriptors and incorporates orientation information to optimize keypoint direction assignment and descriptor generation. With the aid of the alignment technique and the Hikvision platform, this study guarantees that the multi-source pictures have a high level of spatial accuracy before they reach the target detection stage.

Figure 2.

Multimodal Image Processing Flow. (a) Acquisition of RGB–infrared image streams from the multi-modal camera. (b) Pairing of images captured at the same timestamp to ensure temporal correspondence between modalities. (c) Spatial alignment of RGB and infrared images to correct for differences in field of view and imaging geometry. (d) Noise reduction and image cleaning to remove environmental noise. (e) Manual annotation of cattle and sheep targets on paired multimodal images. (f) Through data enhancement strategies, training samples can be enriched and generalization ability can be enhanced.

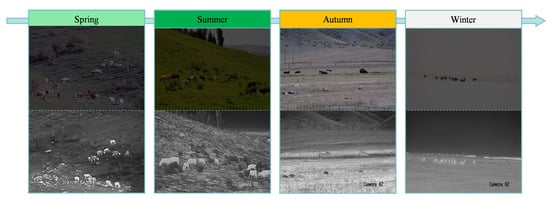

The dataset was manually annotated using LabelImg (v1.8.6), a freely accessible graphical annotation software hosted on GitHub (https://github.com/tzutalin/labelImg (accessed on 10 March 2024)). After completing annotation with LabelImg, pre-processing operations are performed to improve data quality and support subsequent model training. Subsequently, data enhancement strategies such as rotation, translation, flipping, and mosaic are utilized to augment the dataset. These images span all four seasons and were collected under diverse and challenging environmental conditions, spanning diverse practical livestock grazing situations, seen in Figure 3. Figure 4 displays the annotated bounding box size distribution. The resulting dataset is named Multi-modal Ranch Detection Set (MRDS).

Figure 3.

Representative images across four seasons in the grazing environment. The MRDS dataset spans all four seasons to capture the diverse and complex conditions encountered in real-world livestock grazing, including variations in illumination, snow, dense vegetation, and background clutter. This comprehensive seasonal coverage ensures that the proposed YOLO-MSLT network can robustly detect cattle and sheep under a wide range of challenging environmental scenarios.

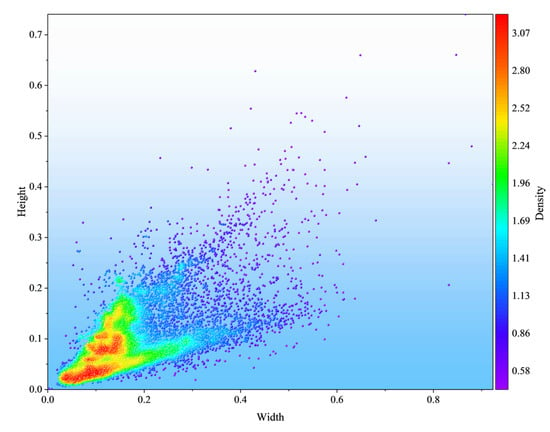

Figure 4.

Visual Representation of the Dataset Distribution. The figure illustrates the size distribution of annotated targets within the MRDS dataset. The aspect ratio (width-to-height) of most targets is approximately 0.5, with the vast majority being medium or small-sized objects. This distribution aligns with the characteristics typically encountered in real-world grazing scenarios.

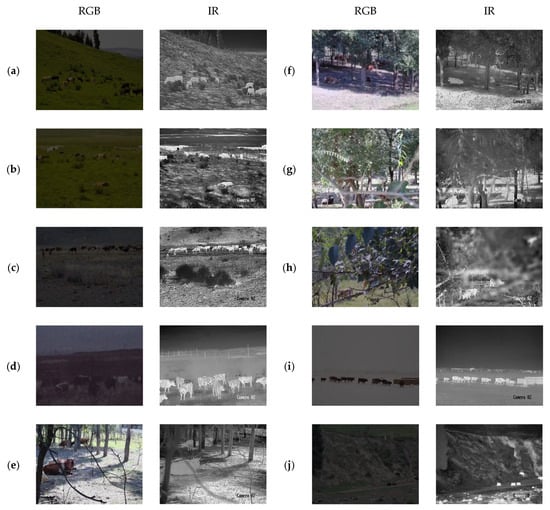

The MRDS dataset is a multimodal cattle and sheep detection dataset collected in complex grazing environments, consisting of 5056 pairs of samples, where each pair includes a visible light (RGB) image and its corresponding infrared thermal (IR) image. According to the captured scenes and the most representative challenging features, the data is categorized as follows: low-light environments and dense shrubbery (1785 pairs, Figure 5a,b), mutual occlusion between animals (1221 pairs, Figure 5c,d), occlusion by foreign objects (722 pairs, Figure 5e–h), inclement weather like rain or snow (598 pairs, Figure 5i), and complex mountainous terrains (730 pairs, Figure 5j). It should be noted that although some samples may possess multiple scene characteristics simultaneously, they are statistically classified according to their most representative category to ensure consistency in categorization.

Figure 5.

Representative Example Images of Medium-Sized Targets across Various Challenging Scenarios in the MRDS Dataset. This figure showcases the synchronized multimodal MRDS dataset (Visible Light and Infrared Thermal pairs) by illustrating medium-sized livestock targets under highly variable real-world grazing conditions. The dataset examples are categorized by their most representative challenges: (a,b) Low-Light and Dense Shrubbery, (c,d) Mutual Occlusion between animals, (e–h) Occlusion by Foreign Objects, (i) Inclement Weather, and (j) Complex Mountainous Terrains.

Regarding object scale, this study clearly defines the division based on the object’s area proportion within the image: objects whose area occupied less than 0.25% are defined as Small Objects; those with an area proportion greater than or equal to 0.25% are defined as Medium Objects. Given that this work primarily focuses on detection tasks in complex husbandry environments, and the identification of large objects is relatively easier, this dataset almost entirely excludes large objects. Therefore, objects are only divided into Small and Medium categories. The statistical results for the 5056 RGB–IR image pairs in the dataset are as follows: 1998 pairs contain Small Objects, and 3058 pairs contain Medium Objects.

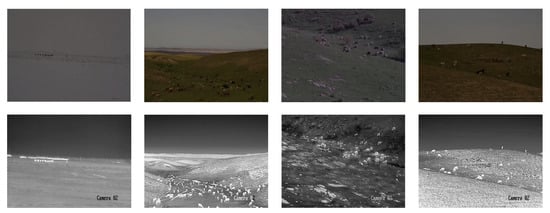

For the experiment, the 5056 image pairs were randomly divided proportionally into the training set (4046 pairs), the validation set (505 pairs), and the test set (505 pairs). Furthermore, to accurately evaluate the model’s performance on long-range small targets (Figure 6), we conducted a secondary screening of the original test set (505 pairs of images) based on the aforementioned scale criterion. This process ultimately yielded a dedicated small-target test set containing 224 pairs of images, which were used for subsequent evaluation.

Figure 6.

Example images of small targets in the MRDS dataset, illustrating distant small objects under challenging conditions such as snowy weather, dense shrubbery, and complex terrain and backgrounds.

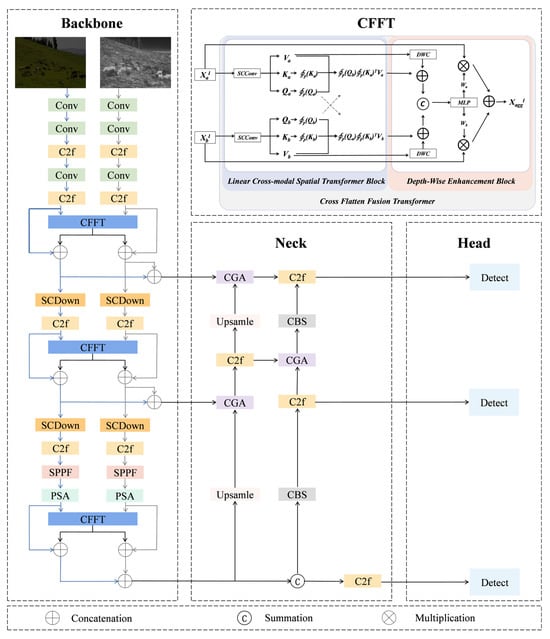

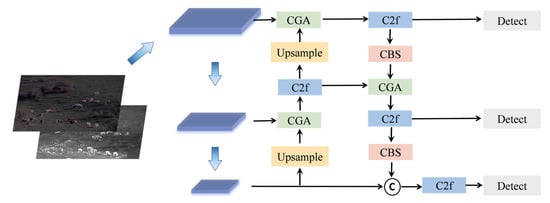

2.3. YOLO-MSLT

Our framework is designed to enhance existing baseline models, broadening their capabilities from single-modality to multi-modal detection for cattle and sheep. As illustrated in Figure 7, the framework is built upon the YOLOv10 architecture. The CFFT framework includes two primary elements: the Linear Cross-modal Spatial Transformer (LCST) module and the Depth-Wise Enhancement (DWE) module, as illustrated in the detailed composition of the CFFT block in Figure 7. Our novel CFFT fusion module is embedded into the C3, C4, and C5 layers of the YOLOv10 backbone. Fusing at the C3–C5 stages ensures that deep coupling and early collaboration of cross-modal information are achieved at the critical periods of feature extraction, preventing information isolation. Moreover, selecting these layers maximizes the complementary benefits of multi-scale features, which aligns with the original design intention of using C3, C4, and C5 as multi-scale detection feature anchors in the YOLO network. In addition, a Content-Guided Attention Feature Pyramid Network CGA-FPN was introduced into the neck [48]. It generates the channel and spatial attention weights dynamically so as to adjust the contribution of different scales of features adaptively concerning the actual content of the input image. With such design, the detection model can precisely locate objects of different sizes—even in cluttered environments or situations with dramatic scale differences.

Figure 7.

The proposed YOLO-MSLT network architecture is built on the dual-stream structure of Yolov10, which contains CFFT blocks on the C3, C4 and C5 layers. Each CFFT block consists of two key modules, the LCST module and the DWE module, with their names clearly labeled within the block. The CGA module is included in the neck section.

2.4. Linear Cross-Modal Spatial Transformer

LCST is designed to operate with the lowest computational resources while exploiting the correlation between the integral features of multimodalities efficiently. Because of the constant improvements brought to the field of computer vision by the derivatives of Transformer, including the Vision Transformer (ViT), it has only slowly emerged that Transformers are in use in fusion of information in multimodal fusion vision tasks. Found at the center of the initial Transformer architecture are three components: Query, Key, and Value. In particular, the derivation of input features X, Q, K, and V is as follows:

The attention mechanism computes similarity scores as dot products between queries and keys, normalized by a Softmax function to yield weights. The values V are then given weights, creating a weighted representation of the input. The scaling factor in the denominator prevents excessively large dot products, which can lead to vanishing gradients in the Softmax function. This scaling ensures training stability, especially when the feature dimension dk is high. This weighted output is critical because it models the global dependencies within the input features, which is a core capability inherited by our LCST module in the multimodal fusion approach. Furthermore, the theoretical foundation of LCST is rooted in this standard attention form.

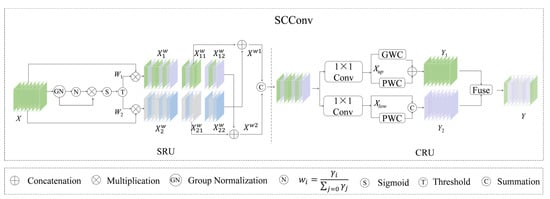

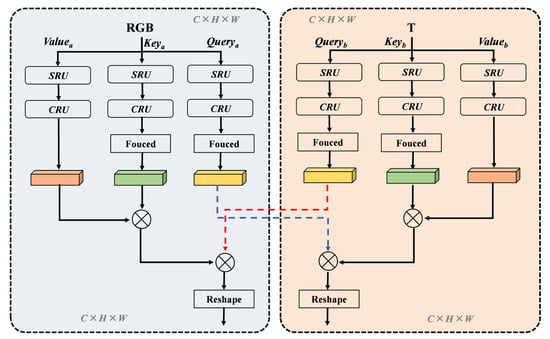

To further enhance the Transformer’s capability in spatially extracting features from different modalities and to alleviate the high complexity introduced by matrix multiplication, this paper introduces the LCST module for multimodal feature fusion. Differing from typical Transformer fusion modules, the LCST module initially employs the SCConv (Spatial and Channel Convolution) module [49] to derive features from RGB and thermal images. SCConv integrates a Spatial Reconstruction Unit (SRU) and a Channel Reconstruction Unit (CRU), aiming to diminish spatial and channel redundancies within CNNs. Figure 8 illustrates the SCConv structure.

Figure 8.

The architecture of Spatial and Channel Convolution. SCConv extracts features from RGB and thermal images using SRU and CRU. It reduces spatial and channel redundancies and is used in the LCST module to enhance multimodal feature fusion. In SRU, green and purple denote informative feature maps with high-activation spatial regions, while grey and blue represent redundant or less informative feature maps. In CRU, green represents the upper stage for extracting rich representative features, while purple denotes the lower stage for generating shallow supplementary features to reduce channel redundancy.

The fundamental equation for SRU is given by:

where X is the input feature map, δ is the learnable scale parameter, GN is the group normalization operation, ⊗ denotes element-wise product, and represents the mapped feature after spatial remodeling.

Similarly, the core formula of CRU can be expressed as:

In the formulation, and are the feature subsets from the split channels. Group-wise convolution GWC and point-wise convolution PWC transform these subsets. Pooling decreases spatial dimensions, and Softmax is subsequently applied to obtain the refined channel-wise attention.

Consequently, the three vectors for a single modality can be represented as:

This implies that the model pays greater attention to the spatial layout of the input data, thereby enhancing the model’s expressiveness when dealing with spatially rich RGB and infrared data, such as images. This approach allows for the effective capture of local contextual information without a substantial rise in parameter count. Subsequently, the LCST utilizes a focus function and linear attention mechanism for feature fusion. Specifically, during the computation of similarity scores within the self-attention mechanism, the Q vector from the RGB modality is point-multiplied with the K vector from the infrared modality, and vice versa. Such a cross-modal query mechanism enables the model to consider information from one modality while processing features of another. The focus function and linear attention mechanism operate as follows:

Herein, Sim(Q,K) denotes the similarity function between the query matrix Q and the key matrix K. denotes the element-wise exponentiation of x to the power p. By adopting a focused function , the computational order of the self-attention mechanism has been optimized. Assuming the dimensionality of image input, the complexity has been reduced from to , where N represents the feature size and d the dimensionality of the features. Within this context, p is an adjustable parameter in the function , which controls the importance of each vector component to enhance feature representation.

Figure 9 outlines the module’s structure. The performance of linear attention techniques is greatly improved by this structural improvement, which also reduces computing overhead. Subsequently, we formulate the cross-modal query as follows:

Figure 9.

The structure of the LCST module.

Consequently, the LCST module, by integrating multimodal information from RGB and infrared images, significantly enhances the accuracy and adaptability of feature recognition in complex environments. Its effectiveness is especially evident under extreme lighting or high-contrast conditions, providing robust support for high-resolution, adaptive image analysis and precise feature detection.

2.5. Depth-Wise Enhancement

The LCST module extracts global features across multimodal images using spatial attention. In traditional Transformer models, the Softmax attention matrix typically has full rank, signifying a high degree of feature diversity. This contributes to a more comprehensive aggregation of features from V. However, when linear attention is employed, the rank of the attention matrix is limited, leading to many rows in the matrix becoming similar and, consequently, the aggregated features also tend towards similarity. This results in a sub-full rank in the LCST, prompting the introduction of the DWE (Depth-Wise Enhancement) module to increase the rank of linear attention. The DWE module includes two DWC (Depth-wise Convolution) functions, and when combined, the formula is as follows:

The DWC module directs each query Q to focus on specific neighboring spatial features, instead of the entire feature set V, enhancing the diversity and spatial relevance of feature representation. This allows even queries with identical weights under linear attention to generate unique outputs based on their respective local features, effectively compensating for the potential information loss associated with linear attention mechanisms. Employing an MLP layer and the Softmax function, we compute weight vectors , , to reassign RGB and infrared channel features. To effectively utilize combined data while minimizing noise and repetition, we integrate cross-modal features with dual adaptive channel weights:

The resultant feature maps are computed as and , and are propagated to the subsequent layers.

The RGB modality supplies ample color and texture clues, while the infrared modality presents indicative thermal patterns and structural contours. Through cross-modal information exchange, the modalities would interact in an integrated manner, enabling better feature fusion and generalization under different scenarios.

2.6. Content-Guided Attention Feature Pyramid Network

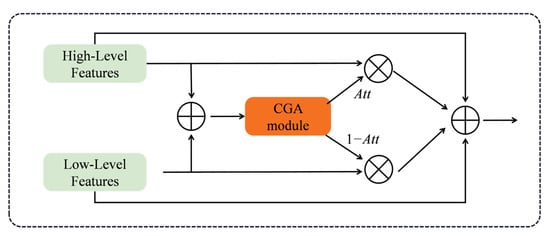

To overcome the limitation of conventional Feature Pyramid in multi-scale integration, this research proposes a fusion module with Content-Guided Attention (CGA) [48], as depicted in Figure 10. The CGA module offers a finer dynamic weighting strategy by generating channel-specific spatial attention maps. Contrarily, the traditional way considers all channels with equal spatial importance, while the CGA method models the spatial importance of each channel independently to enhance the salient region and suppress background clutter. By adaptively adjusting attention based on image content, CGA improves the flexibility and accuracy of feature fusion, particularly in response to variations in target size and distribution.

Figure 10.

CGA fusion module. The CGA module generates channel-specific spatial attention maps to enhance salient regions and suppress background clutter, improving multi-scale feature fusion.

We innovatively embed the fusion module of CGA (CGAFusion) into the PAN-FPN (Path Aggregation Network-Feature Pyramid Network) structure, and introduce CGA-FPN, a novel feature fusion module replacing conventional methods, illustrated in Figure 11. The core of the PAN-FPN architecture lies in its bidirectional fusion mechanism, designed for the efficient integration of features extracted from different backbone network levels. It utilizes the FPN path to transmit deep, high-level semantic information in a top-down manner to shallow features, thereby enhancing semantic context. Simultaneously, the PAN path aggregates shallow, high-resolution localization information into deeper features in a bottom-up fashion. This structure has become a widely adopted standard in multi-scale object detectors. The CGA-FPN proposed in this study adopts the bidirectional topology of PAN-FPN but crucially replaces the core feature fusion module with the innovative CGA module. In this process, the channel and spatial attention weights of the fused features are dynamically generated by the CGA after splicing high-level features and low-level features.

Figure 11.

Structure of CGA-PAN module. CGA-PAN embeds the CGA fusion module into the bidirectional PAN-FPN, dynamically generating channel and spatial attention to enhance multi-scale feature integration.

Specifically, CGA first extracts global channel significance information through the channel attention (CA) mechanism to highlight key feature dimensions. Subsequently, the Spatial Attention (SA) mechanism is introduced to further capture the local salient regions to generate the initial feature weight distribution. To enhance the precision of feature fusion, CGA also combines the pixel attention (PA) mechanism to refine the features to optimize the local details of the features.

On this basis, CGA employs a content-guided mechanism to refine coarse feature weights and dynamically generate channel-specific attention maps for targeted feature enhancement. The weighted features are then fused via convolution to produce the output feature map. By adaptively adjusting the multi-scale fusion strategy, this approach mitigates the information loss of traditional concatenation or summation methods and significantly enhances fusion accuracy and effectiveness.

where is the high-level feature map of the network after up-sampling, is the feature map of this layer, is a weighting coefficient that determines the degree of contribution of the two, stands for the Sigmoid function, and C stands for the splicing operation.

CGA replaces traditional fusion strategies with dynamic channel and spatial attention weights, adaptively balancing multi-scale feature contributions. This improves the model’s flexibility in handling scale and distribution shifts, boosting multi-scale detection precision and resilience in challenging environments.

2.7. Network Training Implementation Details

In these studies, the input size of both modal images in all networks was set to 640 × 640 × 3, and the training used 800 epochs, a batch size of 16, and a learning rate of 0.0015. The optimization was carried out using the SGD optimizer with momentum (Momentum: 0.937) and a Weight Decay of 0.0005. Our codebase was implemented in Python 3.11.8 using the PyTorch 2.8.0 + cu126 deep learning framework. The computational performance was accelerated by the CUDA 12.6 toolkit and the cuDNN 9.10.2 library. The full scientific computing environment utilized standard scientific libraries, including numpy 1.26.4, opencv 4.10.0, matplotlib 3.8.0, tqdm 4.67.1, scipy 1.13.1, and pandas 2.1.4. The experiments were carried out using an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU equipped with 24 GB of RAM, running on the Windows 10 operating system.

2.8. Performance Evaluation

To thoroughly assess YOLO-MSLT’s effectiveness, we utilize four primary indicators: Precision (P), Recall (R), mean Average Precision (mAP), and Frames Per Second (FPS).

Within this research, the True Positive (TP) metric characterizes the total number of detection targets accurately identified by the model in each category, while the number of targets that are misclassified or improperly categorized is represented by the False Positive (FP) metric. The number of genuine targets that were missed is known as the False Negative (FN) metric.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison with Other Methods

Several widely adopted target detection algorithms were implemented on our self-constructed MRDS dataset and selected as comparison methods to evaluate the performance of the proposed model, including Faster R-CNN [50], RetinaNet [51], YOLOv8 [52], and YOLOv10 [53]. Additionally, we compared our method with existing multimodal models and fusion modules, with particular focus on the CSCA [54] and CFT [55] modules, which were integrated into the dual-stream YOLOv10 baseline. Experimental results indicate that our approach achieves competitive performance on most evaluation metrics compared to existing methods.

Table 2 illustrates algorithmic performance contrasts within the MRDS dataset. The YOLO-MSLT model, which integrates RGB and infrared images, demonstrates outstanding performance on this dataset. Specifically, at an IoU threshold of 0.5, it achieves an mAP score of 91.8%, outperforming the Baseline + CFT and Baseline + CSCA modules by 6.3 and 5.1 percentage points, respectively. Moreover, its precision reaches 93.2%, exceeding the Baseline + CFT and Baseline + CSCA modules by 5.4 and 4.7 percentage points, respectively. These findings not only highlight the efficiency and progressive approach of the YOLO-MSLT model in fusing RGB and infrared images but also underscore its substantial improvements in precision and mAP compared to conventional methods.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of different algorithms.

It is clearly observed from Figure 5 and Figure 6 that the sample dataset presents highly complex environmental conditions, including a large number of small cattle and sheep targets. This complexity is likely one of the reasons for the relatively lower accuracies recorded by Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, and YOLOv8. Additionally, a significant share of the data consists of low-light images. In such environments, infrared image features become more prominent, which may partly explain why the mAP scores of Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, YOLOv8, and YOLOv10 are generally higher on the infrared modality dataset compared to the RGB modality dataset.

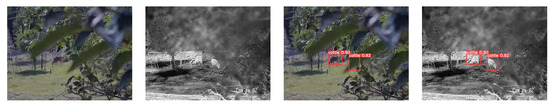

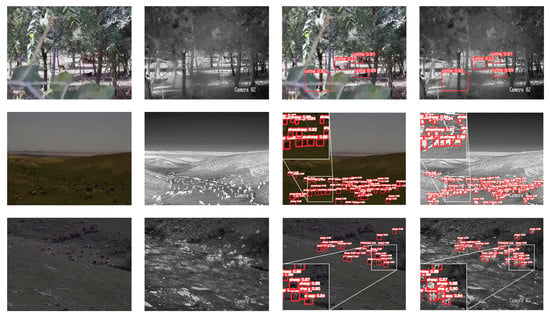

The CFT module consists of eight repeated Transformer blocks and applies global average pooling to downsample the feature maps to a lower resolution, thereby reducing computational costs. However, due to insufficient extraction of complementary information, the loss of high-frequency details during downsampling is exacerbated, which impairs small target detection. The CSCA module, on the other hand, suffers primarily from sensitivity to modality noise, and its feature reassembly mechanism leads to local information loss, which particularly limits fine-grained modeling capabilities in dense scenes. Compared with state-of-the-art methods like CFT and CSCA in the field, our proposed model effectively mitigates the limitations of these modules by preserving high-frequency details during feature fusion and enhancing robustness to modality noise. The LCST module facilitates more precise cross-modal feature alignment, while the CGA module strengthens attention to small-scale and densely distributed targets. As a result, our approach consistently outperforms both CFT and CSCA in terms of detection accuracy, demonstrating superior capability in complex agricultural environments. To assess the generalization capability of YOLO-MSLT, we conducted tests on cattle and sheep images collected from various complex environments. The detection results achieved by our method are shown in Figure 12. As illustrated, the YOLO-MSLT model can reliably identify targets in complicated situations. The findings confirm the robustness of the YOLO-MSLT method.

Figure 12.

Examples of detection results using YOLO-MSLT.

Our YOLO-MSLT model runs at 25 FPS. Although this is lower than the single-stream YOLOv8 (31 FPS), single-stream YOLOv10 (37 FPS), and dual-stream YOLOv10 (35 FPS), its accuracy is significantly superior to these models. Moreover, 25 FPS still meets the real-time requirements for precision livestock monitoring (>20 FPS).

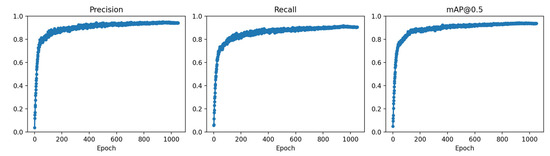

Figure 13 illustrates the performance curves of the YOLO-MSLT model on the validation set, showing the trends of Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5 across training epochs. The curves indicate that the model learns rapidly during the initial phase, and although the improvement slows around the 350th epoch, it continues to increase. This phenomenon is due to the fact that, compared with ordinary single-stream models, the YOLO-MSLT architecture involves complex interactions between RGB and Infrared (IR) modalities as well as deep fusion of feature maps, requiring more time during early training. Consequently, even at the 350th epoch, the model’s performance continues to improve significantly. Ultimately, the metrics begin to stabilize and reach a converged at approximately the 790th epoch.

Figure 13.

The figure shows the performance curves of the YOLO-MSLT model on the validation set across training epochs, illustrating the trends of Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5. The curves clearly reflect the model’s performance improvement during training.

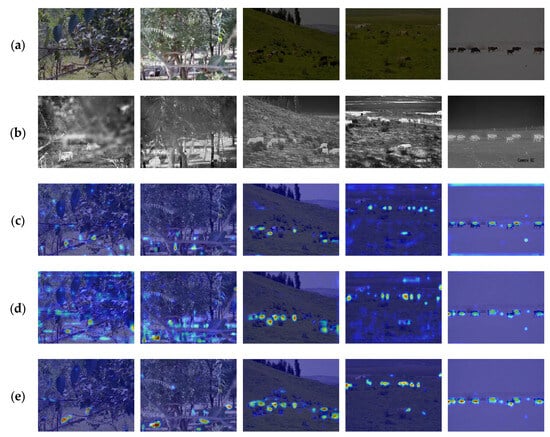

To improve model interpretability, this study presents Grad-CAM [56] visualization method. Grad-CAM generates pseudo-color heatmaps by extracting gradient information from feature maps and mapping it onto the original image space, thereby visualizing the key regions attended to during the prediction process. The highlighted areas in the heatmap represent the main regions of interest of the model in determining the target, while the darker areas represent the parts that the model pays less attention to. Illustrated in Figure 14, the Grad-CAM thermal map visibly reveals how the model focuses on the target region. In contrast to conventional target identification techniques, the suggested model can accurately focus on important aspects, such as the head, body and leg regions, thus locating the target more precisely and generating a tighter bounding box. The findings confirm the model’s efficacy in target detection.

Figure 14.

Comparison findings are shown. (a,b) are the original RGB and infrared images; (c) demonstrated the effect of dual-stream YOLOv10; (d) demonstrates the effect of the dual-stream YOLOv10 model with the introduction of the CSCA module; (e) demonstrates of the effect of the YOLO-MSLT model. The heatmap color gradient indicates spatial importance: red denotes high-activation regions (hotspots) critical for model decisions, while blue signifies low-activation areas with minimal contribution. From the Grad-CAM heatmaps, it can be seen that the proposed YOLO-MSLT method performs better, focusing more clearly on key target regions such as the head, body, and legs, resulting in more precise and tighter bounding boxes.

To further assess the multi-scale fusion module CGA-FPN’s reliability and performance, two improved algorithms, LFPN [57] and FPT [58], were selected for comparison in this experiment, and the dual-stream YOLOv10 model loaded with the CFFT fusion module is used as the baseline model. During the experiment, the relevant parameters were adjusted to ensure that the base conditions of the experiment remained consistent. The results in Table 3 were obtained on the test set of the MRDS dataset, which contains 505 sets of image pairs. On the MRDS dataset, our proposed YOLO-MSLT model, which incorporates the CGA-FPN structure, achieves mAP@0.5 (%) improvements of 3.7%, 1.5%, and 0.4% compared to PAN-FPN, LFPN, and FPT, respectively. These performance gains can be attributed to the CGA module’s multi-level dynamic adjustment mechanism.

Table 3.

Comparative results of multi-scale fusion modules based on dual-stream YOLOv10 with the CFFT module.

CGA-FPN contains far fewer parameters than the FPT module, which leads to better performance without adding computational steric hindrance. In low-light and nighttime surveillance, the CGA module fairly balances fine-grained details with large context information, hereby hugely facilitating small target detection. It keeps its detection credibility by reassigning weight factors between high-level features and low-level ones during occlusions with the clever use of global context while maintaining key information at the local level. Unlike the FPT module, which is barred from fast computing owing to too many parameters dealing with complex operations, the CGA-based approach maintains real-time performance.

To analyze in detail the performance of the YOLO-MSLT framework, in addition to the comparative experiments conducted on the custom MRDS livestock collection, we also evaluated the model using the additional benchmark provided by the widely used multimodal dataset LLVIP [59]. LLVIP is a widely used multimodal dataset designed for low-light pedestrian detection. It contains 15,488 pairs of simultaneously captured visible and infrared images collected under low-light and nighttime conditions. Each image pair is spatially aligned and annotated with pedestrian bounding boxes. Evaluating YOLO-MSLT on LLVIP allows us to examine the model’s stability across different types of scenes, thereby assessing the robustness of its multimodal fusion mechanism. This also further demonstrates that YOLO-MSLT is not limited to a single-domain dataset but can generalize effectively to other multimodal detection tasks. Due to its high-quality annotations and challenging illumination conditions, LLVIP has been extensively employed as a benchmark for evaluating multimodal detection models and their cross-dataset generalization capability. To achieve a fair cross-dataset evaluation, the LLVIP dataset was first split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 8:1:1. The YOLO-MSLT framework was then transferred to the LLVIP dataset and retrained on its training set prior to evaluation, ensuring proper model selection and assessment. All results in Table 4 are therefore based on the LLVIP test set. Table 4 displays the effectiveness of the proposed model’s detection capability, demonstrating how adaptable and robust it is in complex environments and multimodal input situation.

Table 4.

Experimental results on the LLVIP dataset using dual-stream YOLOv10 as the baseline model.

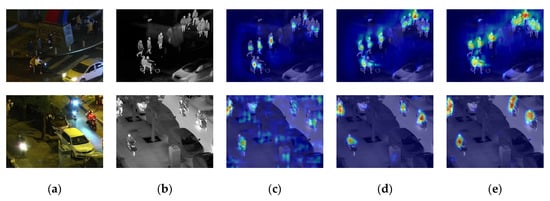

As shown in Figure 15, applying Grad-CAM further reveals that the YOLO-MSLT model displays more human-body-focused attention, with more distinguishable and interpretable activation regions.

Figure 15.

Comparative visualization results on the LLVIP dataset using Grad-CAM. (a) original RGB image; (b) corresponding infrared image; (c) visualization of the baseline dual-stream YOLOv10 model; (d) visualization of the dual-stream YOLOv10 model with the CSCA module; (e) visualization of the proposed YOLO-MSLT model. The heatmap color gradient indicates spatial importance: red denotes high-activation regions (hotspots) critical for model decisions, while blue signifies low-activation areas with minimal contribution. Applying Grad-CAM shows that the YOLO-MSLT model exhibits stronger attention on human body regions, with clearer and more interpretable activation areas.

3.2. Ablation Study

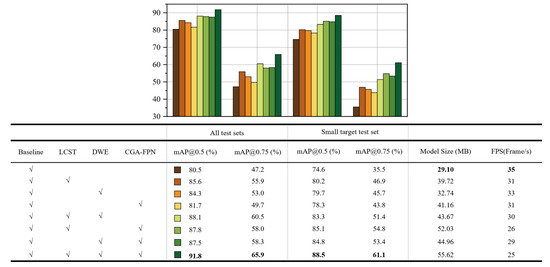

The purpose of our ablation study is to assess the separate and combined implications of the LCST, DWE, and CGA modules to the detection performance of sheep and cattle in challenging settings. As shown in Figure 16, we used the dual-stream YOLOv10 as the baseline and analyzed the impact of LCST, DWE, and CGA on mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.75. To evaluate each module’s effectiveness in detecting small objects, we constructed a dedicated small object test set by selecting images from the original MRDS test set that met the small object criteria. Both the small target test set and the entire test set were evaluated in the ablation experiment. The experimental results proved that each module independently improves the effectiveness of the entire system.

Figure 16.

Comparison of performance in ablation experiments. Bold values indicate the best performance for each metric. The “√” indicates the integration of the corresponding module in the ablation study.

Specifically, on the complete test set, the integration of the DWE module has resulted in an enhancement of 3.8% in mAP@0.5 and 5.8% in mAP@0.75. Even higher improvement in performance has been achieved when the LCST module was independently integrated, with the mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.75 having been improved by 5.1% and 8.7%, respectively. With CGA integration, the mAP@0.5 rose by 1.2%, with the mAP@0.75 going up by 2.5%. It could be that the dual-stream YOLOv10 baseline model may not have been able to perform a good fusion of multimodal features, so the performance is not excellent enough, and hence the mAP@0.5 was not enhanced noticeably after the integration of the CGA module. The LCST + DWE combination deserves to be mentioned for an mAP@0.5 improvement of 7.6% and an mAP@0.75 improvement of 13.3%, which is better than LCST + CGA and DWE + CGA. This attests that our novel CFFT structure is capable of exploiting complementary fine feature information between RGB and infrared images, combining deep perceptual abilities to significantly enhance detection accuracy and improve its adaptability to various environments. Furthermore, as the complete test set contains a high volume of medium-sized targets, this demonstrates the CFFT structure’s outstanding capability in accurately localizing medium-sized objects and refining deep perceptual features. If all three modules are integrated simultaneously into the network, performance gains are maximized, with an 11.3% increase in mAP@0.5 and 18.7% in mAP@0.75.

When conducting experiments on the small target test set, the data pointed toward significant performance gains for every module concerning the small target detection task. The dual-stream YOLOv10 could only manage an mAP@0.5 of 74.6%, which is a degradation of 5.9% compared with its evaluation on the full test set. Basically, it indicates that the dual-stream YOLOv10 was underperforming in both situations; hence, more emphasis was laid on the challenge of identifying small targets with precision in complex backgrounds. Just LCST integration resulted in improvement in mAP@0.5 by 5.6% and mAP@0.75 by 11.4%, showing that the module has truly enhanced the model’s ability to locate small targets. Though the CGA might have been less effective on the complete set, it demonstrated significant improvement on the small targets test set, with an increase of 3.7% in mAP@0.5 and 8.3% in mAP@0.75. This compellingly proves the potential of the CGA module in cross-modal feature fusion, especially for small target detection, also highlighting the advantages of CGA for dense prediction tasks. As shown in Figure 16, the experimental results demonstrate a clear accuracy-efficiency trade-off: integrating the LCST, DWE, and CGA-FPN modules improves mAP but increases Model Size and reduces FPS. While these enhancements significantly boost detection performance, they come at the cost of inference speed. Crucially, our final model achieves the highest accuracy while maintaining a functional real-time capability (25 FPS), affirming its practical utility.

Our novel modules fuse complementary information to maximize the complementary strengths of multimodal features for improving feature map representation. This fusion improves the model’s precision in identifying objects in complicated environments. Integrating both LCST and CGA modules improved mAP@0.5 by 4.9% over using LCST alone. This demonstrates that for small object detection, the CGA module performs much better when multimodal features are fused properly. CGA assigns weight distribution dynamically for feature maps in channel, spatial, or pixel dimensions, making great use of the complementarity of information from multimodal inputs. It helps in mitigating the information loss and degradation in feature quality posed by the classical multiscale feature fusions while enhancing the accuracy of the model for small object detection. These results confirm YOLO-MSLT’s strong performance, offering solid support for cattle and sheep recognition in complex scenes.

4. Discussion

The YOLO-MSLT multi-modal fusion detection network proposed in this study achieves significant breakthroughs in cattle and sheep detection tasks in complex scenes, with an mAP@0.5 of 91.8% and both recall and precision exceeding 89%, marking a substantial improvement over mainstream models. Three major modules were conceived in the model of the research innovation: Linear Cross-modal Spatial Transformer (LCST), Depth-Wise Enhancement (DWE), and Content-Guided Attention Feature Pyramid Network (CGA-FPN). These modules bring together the respective qualities of infrared imagery and the RGB image. Therefore, they can overcome the deficiencies of standard methods in different situations such as low-light conditions, occluded environments, and small target detection. The LCST module employs SCConv to reduce feature redundancy and optimizes cross-modal global feature correlations through a linear attention mechanism, reducing computational complexity from O(N2d) to O(Nd2), significantly enhancing efficiency. Using depth-wise convolution in the DWE module enhances local spatial feature representation. The CGA-FPN module enhances multi-scale detection accuracy, especially on small targets, improving robustness and accuracy in complicated environments. It offers deeper synergistic advantages in feature-level fusion compared to other options: While CSCA relies on channel attention and CFT simply concatenates modalities, the LCST module uses spatial transformation together with linear attention to strengthen cross-modal correlations and decrease the computational cost. Furthermore, the DWE module enhances local features to boost generalization abilities in complex terrains.

YOLO-MSLT provides an efficient solution for Precision Livestock Farming (PLF), enabling real-time monitoring at 25 FPS to support grazing optimization and reduce labor costs. Its non-contact design avoids stress caused by traditional hardware, aligning with animal welfare standards. This approach also offers direct practical value for farmers and ranch management. Based on a multimodal RGB–infrared fusion design, it can robustly detect cattle and sheep under complex conditions, such as low light and occlusion. This capability enables accurate spatial distribution estimation, assisting in grazing planning and resource allocation. Precise real-time detection reduces the need for manual inspections, improving management efficiency, and indirectly aids in recording population changes, thereby minimizing potential losses. Long-term use facilitates the accumulation of data on livestock numbers and activities, enhancing animal safety and supporting remote monitoring, which elevates the management capabilities for large-scale or geographically complex ranches. Livestock farming constitutes a primary source of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions, predominantly through respiratory metabolism, enteric fermentation, and manure management, which emit methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Accurate estimation of livestock distribution facilitates more precise quantification of CH4 and N2O emissions. Field validation in the complex terrain of Xinjiang’s Manas River Basin confirms the model’s robustness.

Despite these strengths, several limitations remain. First, although the model improves small-object detection, performance declines for extremely distant livestock where image resolution becomes severely limited. Second, the method relies on paired RGB–infrared data, which may restrict deployment in scenarios where multimodal sensing is unavailable or imperfectly synchronized. Third, while cross-dataset evaluation on LLVIP confirms a degree of generalization, more systematic validation is still required for other species such as horses, deer, or donkeys in complex natural environments. Collecting such datasets and conducting field experiments will be essential for a comprehensive assessment of robustness. Moreover, compared with lightweight single-modality detectors, the current framework still incurs a relatively high computational cost, which may challenge deployment on low-power edge devices.

Future work will focus on three directions:

- exploring GAN-based [60] image enhancement and super-resolution techniques to further improve ultra-small object detection;

- developing lightweight variants of YOLO-MSLT through pruning, knowledge distillation, and quantization to improve suitability for edge deployment;

- expanding cross-species generalization via transfer learning and adaptive multimodal alignment, particularly for animals such as horses and deer.

Overall, YOLO-MSLT introduces a novel multimodal fusion framework, achieving a balance between precision and speed for livestock detection in challenging settings. This advancement not only drives technological innovation in precision agriculture but also opens new avenues for research in multimodal object detection. Future efforts should focus on model lightweighting, data diversity, and cross-domain applications to maximize its economic and ecological benefits.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents YOLO-MSLT, an advanced multimodal fusion network that addresses low-light RGB visibility limitations. YOLO-MSLT comprises three innovative modules: the LCST module, which employs SCConv and a linear attention mechanism to record correlations between global features in multimodal data in the spatial domain; the DWE module, which supports depth information to mitigate the constraints of linear attention; and the CGA-FPN module, which dynamically generates channel and spatial attention weights for fused features. Extensive evaluation on the MRDS dataset strongly highlights the effectiveness and superiority of YOLO-MSLT in facilitating multimodal cattle and sheep detection under complex conditions. This study advances multimodal livestock detection in challenging environments and introduces an innovative method to improve low-light object detection using infrared–visible data synergy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L., J.L. and P.G.; Methodology, Y.B. and R.D.; Software, Y.B. and R.D.; Validation, Y.B. and Y.L.; Formal analysis, Y.B., R.D., X.W. and C.L.; Investigation, Y.B., X.W. and C.L.; Data curation, Y.L. and X.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.B. and Y.L.; Writing—review and editing, Y.B., Y.L. and J.L.; Visualization, Y.L. and P.G.; Supervision, P.G.; Project administration, P.G.; Funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62265015), the Financial Science and Technology Project of Huyanghe City (Grant No. 2023B15), and the Financial Science and Technology Project of Shihezi City (Grant No. 2024TD01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved only non-invasive observation and photography of animals in a natural pasture environment, without any physical contact with the animals; therefore, ethical approval was not required.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Shihezi University for its support throughout this research. We are also grateful to all the scholars cited in this paper and to the anonymous referees for their constructive comments and valuable suggestions. In addition, we sincerely thank Long Mi, Liang Ren, and Peng Ren from the Science and Technology Informatization Detachment, Public Security Bureau of Huyanghe, Huyanghe 834034, China, for their valuable assistance in field data collection, experimental scene design, data organization, and software support during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bernabucci, G.; Evangelista, C.; Girotti, P.; Viola, P.; Spina, R.; Ronchi, B.; Bernabucci, U.; Basiricò, L.; Turini, L.; Mantino, A. Precision livestock farming: An overview on the application in extensive systems. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 859–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Scott, S.; Mancini, C.; Boivin, X.; Strand, E. Human-computer interactions with farm animals—Enhancing welfare through precision livestock farming and artificial intelligence. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1490851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, F.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ren, F.; Nie, L.; Aodemu; Feng, W. Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions Characteristics and Emissions Reduction Measures of Animal Husbandry in Inner Mongolia. Processes 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesschen, J.P.; van den Berg, M.; Westhoek, H.; Witzke, H.; Oenema, O. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteny, G.; Groenestein, C.; Hilhorst, M. Interactions and coupling between emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from animal husbandry. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems 2001, 60, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Kong, H.; Clark, C.; Lomax, S.; Su, D.; Eiffert, S.; Sukkarieh, S. Intelligent perception for cattle monitoring: A review for cattle identification, body condition score evaluation, and weight estimation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 185, 106143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Syed, D.F.; Ploughe, M.; Zhang, W. Autonomous vision-guided object collection from water surfaces with a customized multirotor. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2021, 26, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanidakis, C.; Tzamaloukas, O.; Simitzis, P.; Panagakis, P. Precision livestock farming applications (PLF) for grazing animals. Agriculture 2023, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chen, K.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. Proc. IEEE 2023, 111, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Shi, C.; Liu, J.; Ma, P.; Ma, J. Behavior recognition and maternal ability evaluation for sows based on triaxial acceleration and video sensors. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 65346–65360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertz, M.; Große-Butenuth, K.; Junge, W.; Maassen-Francke, B.; Renner, C.; Sparenberg, H.; Krieter, J. Using the XGBoost algorithm to classify neck and leg activity sensor data using on-farm health recordings for locomotor-associated diseases. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.; Yubero, R.; Visitación, B.; Navarro-García, J.; Algar, M.J.; Cano, E.L.; Ortega, F. Analysis of accelerometer and GPS data for cattle behaviour identification and anomalous events detection. Entropy 2022, 24, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wu, P.; Cui, H.; Xuan, C.; Su, H. Identification and classification for sheep foraging behavior based on acoustic signal and deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Gao, K.; Du, R.; Wu, Z.; Firkat, E.; Li, D. Deformable convolution and coordinate attention for fast cattle detection. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 108006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Tang, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, H.; Xin, J.; He, D. Dairy goat detection based on Faster R-CNN from surveillance video. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 154, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekert, M.; Klein, A.; Adrion, F.; Hoffmann, C.; Gallmann, E. Automatically detecting pig position and posture by 2D camera imaging and deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Kawakami, R.; Yoshihashi, R.; You, S.; Kawase, H.; Naemura, T. Cattle detection and counting in UAV images based on convolutional neural networks. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.P.; Karn, A.K.; Gola, K.K.; Suyal, P. Advancements in Animal Behaviour Monitoring and Livestock Management: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I), Greater Noida, India, 18–20 September 2024; pp. 1206–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, W.; Ren, C.; Han, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, F.; Liu, Z. Cattle Body Detection Based on YOLOv5-EMA for Precision Livestock Farming. Animals 2023, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Weng, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, C. Algorithm for cattle identification based on locating key area. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 228, 120365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Du, S.; Liu, C.; Cao, Z. Interior attention-aware network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5002013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Huang, Z.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Zhong, W.; Luo, Z. Target-aware dual adversarial learning and a multi-scenario multi-modality benchmark to fuse infrared and visible for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5802–5811. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, P.; Hu, Q. Multi-modal gated mixture of local-to-global experts for dynamic image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 23555–23564. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Kang, Y. Multi-modal gait recognition via effective spatial-temporal feature fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 17949–17957. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Zhao, H.; Xie, H.; Gao, B. Multi-sensor decision-level fusion network based on attention mechanism for object detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 31466–31480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xie, S.; Zhao, F.; He, Y.; Lu, H. Metafusion: Infrared and visible image fusion via meta-feature embedding from object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 13955–13965. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, J.; Cao, Y.; Yang, M.Y. Locality guided cross-modal feature aggregation and pixel-level fusion for multispectral pedestrian detection. Inf. Fusion 2022, 88, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, P.; Leung, H.; Gong, K.; Xiao, G. Object Fusion Tracking Based on Visible and Infrared Images: A Comprehensive Review. Inf. Fusion 2020, 63, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Han, M. Cattle identification based on multiple feature decision layer fusion. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, J. Learning soft-consistent correlation filters for RGB-T object tracking. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision: First Chinese Conference, PRCV 2018, Guangzhou, China, 23–26 November 2018; pp. 295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.Y.; Peng, L.; Zhang, X.X. A complementary and precise vehicle detection approach in RGB-T images via semi-supervised transfer learning and decision-level fusion. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Jing, Y.; Wu, G. Decision-level fusion detection method of visible and infrared images under low light conditions. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2023, 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Chen, S.; Gao, S.; Ma, Y. Single-image crowd counting via multi-column convolutional neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 589–597. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. Csrnet: Dilated convolutional neural networks for understanding the highly congested scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 1091–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Ge, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, W. Cross-modal feature fusion for field weed mapping using RGB and near-infrared imagery. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Yang, C.; Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Yang, X.; Fan, J. An object detection algorithm based on infrared-visible dual modal feature fusion. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 137, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal learning with transformers: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12113–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilyuk, K.; Sanford, R.; Javan, M.; Snoek, C.G. Actor-transformers for group activity recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 839–848. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Ren, S.; Lu, S.; Feng, Z.; Tang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, L.; Duan, N.; Svyatkovskiy, A.; Fu, S. Graphcodebert: Pre-training code representations with data flow. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.08366. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.; Hsu, W.-N.; Lakhotia, K.; Mohamed, A. Learning audio-visual speech representation by masked multimodal cluster prediction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.02184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Batra, D.; Parikh, D.; Lee, S. Vilbert: Pretraining task-agnostic visiolinguistic representations for vision-and-language tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; NIPS: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; Volume 32, pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, H.; Yu, Y.; Yang, W.; Lee, K.; Kim, G. Pano-avqa: Grounded audio-visual question answering on 360deg videos. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2031–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Ding, W.; Wang, Z. Cross on cross attention: Deep fusion transformer for image captioning. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 4257–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, V.M.; Rili, I.; Gisiger, T.; Gambs, S.; Vasseur, E.; Cellier, M.; Diallo, A.B. AI-Powered Cow Detection in Complex Farm Environments. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, W.; Burge, M.J. Scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT). In Digital Image Processing: An Algorithmic Introduction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 709–763. [Google Scholar]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Washington, DC, USA, 6–13 October 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.-M. DEA-Net: Single image dehazing based on detail-enhanced convolution and content-guided attention. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 1002–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wen, Y.; He, L. Scconv: Spatial and channel reconstruction convolution for feature redundancy. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 6153–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, T.-Y.; Dollár, G. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Sohan, M.; Sai Ram, T.; Rami Reddy, C.V. A review on yolov8 and its advancements. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics, Tirunelveli, India, 18–20 November 2024; pp. 529–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; NIPS: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Choi, S.; Hong, S. Spatio-channel attention blocks for cross-modal crowd counting. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Macau, China, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Qingyun, F.; Dapeng, H.; Zhaokui, W. Cross-modality fusion transformer for multispectral object detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; Wang, M.; Hua, X.; Sun, Q. Feature pyramid transformer. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 323–339. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Pang, Y.; Nie, J.; Cao, J.; Han, J. Latent feature pyramid network for object detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, M.; Tang, W.; Zhou, W. LLVIP: A visible-infrared paired dataset for low-light vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 3496–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, D.; Olaniyi, E.; Huang, Y. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) for image augmentation in agriculture: A systematic review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.