Abstract

Reproductive traits are essential in dairy cattle breeding, and improving body conformation is considered beneficial for reproductive performance. This study systematically analyzed the genetic relationships between six key conformation traits—stature (ST), body depth (BD), loin strength (LS), rump angle (RA), rump width (RW), bone quality (BQ)—and reproductive performance in 1631 Jersey cattle from China. Heritability estimates for conformation traits ranged from 0.05 to 0.62. We identified significant phenotypic and genetic correlations between conformation and reproductive traits, and regression analyses confirmed the predictive value of conformation traits for reproductive outcomes. Genome-wide association studies detected 24 significant SNPs associated with ST, RW, RA, and BQ. Subsequent bioinformatics analysis revealed seven candidate genes (AZIN1, OR2H1, HS6ST3, ERCC4, KCNH5, KRT19, KRT35) involved in embryonic development and estrous cycle regulation. Notably, incorporating six SNPs, which are linked to these candidate genes, into genomic prediction models significantly improved the accuracy for predicting Age at First Calving (AFC) and Gestation Length (GL). These results elucidate the shared genetic basis of conformation and reproduction, providing theoretical support for using conformation traits in marker-assisted selection to enhance reproductive efficiency in Jersey cattle.

1. Introduction

In modern dairy farming, Jersey cattle are highly valued for their distinct production performance and superior milk quality [1]. Reproductive traits rank among the most critical functional traits in dairy cattle, directly impacting herd productivity and economic sustainability. However, in recent years, intense selection for milk production traits, coupled with the negative genetic correlation between reproductive and milk production traits, has resulted in a decline in the reproductive performance of Jersey cows [2]. Adding to the complexity of genetic improvement is the intricate genetic architecture of reproductive traits themselves, characterized by low heritability (typically less than 5%) and high susceptibility to environmental influences [3]. Furthermore, recording reproductive data is often hampered by subjectivity and missing records, complicating accurate phenotypic and genetic evaluation. Therefore, identifying effective strategies to enhance reproductive capability is crucial. Identifying readily measurable traits with favorable genetic correlations to reproduction offers a crucial indirect strategy for genetic improvement [4,5].

Body conformation traits are vital for dairy cattle genetic improvement, serving not only as direct selection criteria but also as tools for evaluating economically important traits like reproduction [6]. This utility stems from the physiological links between specific conformation traits and key reproductive processes, including estrus expression, ovulation, and calving ease (CE) [7], supporting their role as supplementary fertility indicators. Substantial evidence supports this link: for instance, rump angle (RA) shows genetic correlations with calving interval (0.32) [8], CE (−0.28) [9] and retained placenta incidence (0.38) [10]. Rump width (RW) is correlated with CE (0.15), commencement of luteal activity (−0.25) [11], and early ovulation (EO, 0.55) [9]. Similarly, stature demonstrates correlations with age at puberty (0.28) and pelvic dimensions [12,13], and both loin strength (LS) and body depth (BD) have been connected to CE and embryonic loss, respectively [8,9,14]. While these findings highlight the broad relevance of conformation traits, their relationships with reproductive traits in Jersey cattle remain underexplored.

While phenotypic and genetic correlations provide valuable insights into the relationships between conformation and reproductive traits, uncovering the underlying genetic mechanisms requires genome-level investigation. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) provides a powerful approach for mapping genetic variants underlying complex traits [15]. Prior GWAS in cattle have identified loci influencing both conformation and reproduction, suggesting shared genetic control. For example, the PLAG1 gene affects ST and body weight, and is also associated with fertility traits like AFC [16,17,18]. Similarly, variants near LCORL and NCAPG impact ST, calf size, and CE [19]. However, GWAS specifically targeting both reproduction and conformation traits in Jersey cattle are rarely reported.

This study systematically evaluates six conformation traits (LS, RA, BD, RW, ST, bone quality-BQ) and six reproductive traits (Age at First Service—AFS, AFC, GL, Number of Artificial Inseminations per Successful Conception—AIS, Calf Birth Weight—BiW, and CE) in Jersey cattle to achieve three main objectives: to estimate their genetic parameters and correlations, to assess the utility of conformation in predicting reproduction, and to identify associated genomic regions via GWAS. Through this integrated approach, we seek to elucidate the genetic architecture linking conformation to reproduction and explore its application for marker-assisted selection in Jersey cattle.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The collection of hair follicle samples and phenotypic measurements in this study were conducted under the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University (SYXK (SU) 2022-0044, 15 July 2022) and in compliance with China’s national guidelines for experimental animal welfare (Ministry of Science and Technology).

2.2. Animals and Phenotypic Data

The experimental population comprised 5423 Jersey cattle from three standardized farms: Jiangsu Yinbao Guangming Farm (Farm 1), Zhejiang Taishun Yunlan Farm (Farm 2), and Shanghai Chongming Aoshan Dairy Farm (Farm 3). From this population, 1631 healthy Jersey cows in early lactation (parity 1) were selected for linear type trait evaluation and genome resequencing, based on the availability of complete three-generation pedigrees and reproductive records. All conformation traits were assessed after milking in accordance with the Code of Technology of Type Classification in Jersey cows (Standard No. T/JAASS 143–2024 [20] https://www.ttbz.org.cn/StandardManage/Detail/110067/ (accessed on 13 April 2025)). Specifically, ST, RA, RW, BD, and BQ were directly measured using a measuring tape, digital goniometer, and measuring stick, whereas LS was subjectively scored on a 1–9 scale. To ensure data accuracy and consistency, all cows were simultaneously evaluated by the same three trained evaluators under uniform conditions. The phenotypic value for each trait was calculated as the mean of the three scores, and records deviating from the overall mean by more than 3 standard deviations were excluded.

To investigate the relationship between these conformation traits and reproductive performance, 13,892 reproductive records spanning 2018 to 2024 were collected for these cows. The analyzed reproductive traits included AFS, AFC, GL, AIS, BiW, and CE. CE was scored as follows: 1 (Unassisted), 2 (Easy pull without instruments, requiring no more than two persons), 3 (Difficult pull requiring instruments, more than two persons, internal manipulation, or obstetrical examination), or 4 (Surgical intervention). Phenotypic quality control was applied based on the following criteria: AFS (270 to 900 days), AFC (500 to 1100 days), GL (240 to 310 days), AIS (1 to 9 services), BiW (15 to 50 kg); values exceeding the mean ± 3 SD for each trait were also removed. After phenotypic quality control, data from 4442 Jersey cows and their 8711 reproductive records were retained for subsequent analysis. Reproductive trait descriptive statistics and genetic parameter estimates are provided in Tables S1 and S2, respectively. To ensure the reliability of genetic parameter estimates, all pedigree information was traced back at least five generations, resulting in a comprehensive pedigree file with an average depth of 6.25 generations that included 12,263 individuals (174 bulls and 12,089 cows).

2.3. Genotypic Data and Within-Population Sequence-Based Imputation

Tail hair follicle samples from 1631 Jersey cows were collected and submitted to Tianjin Compson Testing & Inspection Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) for DNA extraction and 1× genome resequencing (DNBSEQ-T7 platform, BGI, Shenzhen, China). Raw reads were filtered for low-quality sequences using fastp (v0.23.2) [21] with default parameters. Cleaned reads were then mapped to the ARS-UCD1.2 bovine reference genome using BWA-MEM (v0.7.17) [22]. Subsequently, BAM files were converted and sorted using SAMtools (v1.6) [23], and duplicate reads were removed with the MarkDuplicates module of PICARD (v3.2.0 https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (accessed on 16 May 2025)). Finally, SNP calling was performed using GATK (v4.4.0.0) [24] HaplotypeCaller. Post-calling filtering employed GATK’s Variant Quality Score Recalibration to eliminate low-quality SNPs, yielding a high-confidence SNP panel for downstream analyses.

The whole-genome sequencing (WGS)-level imputation reference panel used in this study was obtained from CattleGTEx [25]. The genomic imputation process was implemented using the GLIMPSE2 [26] toolset. Specifically, the chunk, split_reference, phase, and ligate modules of GLIMPSE2 were employed sequentially for haplotype phasing and genotype imputation. All software was executed using default parameters. Standard quality control (QC) was applied to the data. Samples were first filtered based on a call rate threshold of >95%. Subsequently, SNPs were filtered using the following criteria: Exclude SNPs with a call rate < 90%; Exclude SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.05; Exclude SNPs showing significant deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE, p-value < 1.0 × 10−6) within the entire cohort. Following QC, a final dataset comprising 10,509,673 SNPs in 1578 Jersey cows were retained for subsequent association analysis.

2.4. Genetic Parameter Estimation and Phenotypic Adjustment

Genetic parameters for Jersey cattle traits were estimated using the Average Information Restricted Maximum Likelihood (AI-REML) algorithm implemented in the DMU software package (https://dmu.ghpc.au.dk/dmu/ (accessed on 26 May 2025)). Analyses were performed employing a single-trait animal model based on the single-step genomic best linear unbiased prediction (ssGBLUP [26]) approach. The model is specified as:

Y is the vector of phenotypic observations, X is the design matrix for fixed effects (Farm, parity, stage of lactation, AFC, test season), is the vector of fixed effect solutions. Z is the incidence matrix relating to observations, is the vector of additive genetic effect, assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution: , where H is a combination of additive genetic relationship matrices based on lineage (12,263 individuals) and genome (1631 individuals), and is the additive genetic variance. is the vector of random residual effects, assumed to follow: , where I is an identity matrix and is the residual variance. Heritability () for each trait was calculated as:.

Additionally, bivariate animal models were fitted to estimate genetic correlations between trait pairs. The general form of the model is specified as follows:

where and are the vectors of observations for traits i and j; and are the vectors of solutions for the fixed effects; and are the vectors of random additive genetic effects, and are the vectors of random residual effects, / and / are the corresponding incidence matrices for the fixed and random effects, respectively.

Genetic correlation between traits i and j is calculated as:

Trait phenotypes were adjusted for significant fixed environmental effects using the following formula:

where is the vector of adjusted phenotypic values, is the original vector of phenotypic observations, X is the design matrix for fixed effects, and is the vector of estimated solutions for the fixed effects obtained from the respective statistical model.

2.5. Construction and Validation of Multiple Linear Regression Models

To analyze the influence of conformation traits on reproductive performance in Jersey cattle, a multiple linear regression model was constructed for reproductive traits that approximate continuous distributions (AFS, AFC, GL and BiW):

where denotes the adjusted phenotypic values of reproductive performance; is the overall mean; represents the regression coefficient for the -th conformation trait; is the adjusted phenotypic vector for the corresponding trait; and e is the vector of random residuals. Trait selection was performed using the leaps package in R, simultaneously optimizing three criteria: maximizing the adjusted R2, minimizing the Bayesian Information Criterion, and minimizing Mallows’Cp statistic (Figure S1).

For the ordinal reproductive traits CE and AIS, we applied ordinal mixed models, which appropriately accommodate the ordered categorical structure and underlying threshold nature of these phenotypes (the ordinal package in R):

where denotes the ordinal phenotypic values of CE or AIS; represents the threshold parameters; is the adjusted phenotypic values of the i-th conformation trait with corresponding regression coefficients , represents the vector of other fixed effects as defined in Equation (1); and denotes the random effects. Conformation effects from ordinal mixed models were reported on the log-odds scale with corresponding standard errors and test statistics. Model selection for CE and AIS was performed by evaluating all subsets of the six conformation traits, with the optimal models determined primarily by minimizing BIC. The best AIC, BIC, and pseudo-R2 values across competing models are summarized in Figure S1.

2.6. Population Structure and Genetic Diversity Analyses

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) decay analysis was performed using PLINK software [27] (version 1.07) to characterize the decline in LD with increasing physical distance between SNP pairs. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on the Jersey cattle population genotype data using GCTA [28] software to visualize population structure and assess genetic relatedness among individuals. Results from both the LD decay analysis and the PCA were visualized using the ggplot2 package (https://github.com/tidyverse/ggplot2 (accessed on 6 June 2025)) within the R statistical computing environment (version 4.0.4).

2.7. Genome-Wide Association Studies

GWAS was performed using Fixed and random model Circulating Probability Unification (FarmCPU) model [29] implemented in the rMVP package for R. The fixed effect model is specified as:

where is the phenotypic observation for the i-th individual, is the genotypes of t pseudo quantitative trait nucleotides (QTNs), is the corresponding effects of the pseudo QTNs, is the genotype of the i-th individual and j-th genetic marker, is the corresponding effect size, is the random residual error for the i-th individual, follow a normal distribution .

The random effect model was used to select an optimal set of pseudo-QTNs as covariates to control for background genetic effects:

where and stay the same as in Equation (7), is the genetic effect of the i-th individual. The variance-covariance matrix of the individuals’ total genetic effects is , where K is the kinship matrix derived from the pseudo-QTNs, and represents the unknown additive genetic variance component.

The Bonferroni correction [30] was applied to account for multiple testing, setting the genome-wide significance threshold to 4.76 × 10−9 (α = 0.05/10,509,673 SNPs). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) surpassing this threshold were considered significantly associated with the trait. The genomic inflation factor (λ) was calculated according to the method described by Yang et al. [31]. to assess potential population stratification or model misspecification and minimize false positives. The proportion of phenotypic variance explained (PVE) by each significant SNP was estimated using the following formula [32]:

where is the estimated effect size of the SNP from the GWAS model, is the minor allele frequency of the SNP, is the standard error of the estimated effect size , N is the number of individuals included in the GWAS analysis.

2.8. Functional Annotation of Candidate Genes

We defined candidate genes as those located within 200 kb upstream and downstream of significant SNPs based on the ARS-UCD1.2 reference genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_002263795.1/ (accessed on 8 June 2025)). The gene symbols were batch-converted to Entrez IDs using the bitr function in the R package clusterProfiler [33] with the org.Bt.eg.db annotation database to facilitate downstream functional annotation.

2.9. Genomic Prediction Accuracy and Bias Assessment

To evaluate the influence of significant SNPs associated with conformation traits identified through GWAS on reproductive performance, we implemented a marker-assisted animal model. Building upon the base model (1), we incorporated significant SNPs that reached genome-wide significance level for rump traits as fixed effects:

where s is the vector of fixed effects for the selected SNP genotypes (coded as 0, 1, 2 based on allele copy number), and W is the incidence matrix relating genotypes to the observations. The remaining components of the model were consistent with those in model (1).

A 5-fold cross-validation scheme with 50 independent replicates was applied to evaluate prediction accuracy under both models. Predictive ability was assessed as the Pearson correlation coefficient between the genomic estimated breeding values (GEBVs) and the corrected phenotypic values. Prediction bias was quantified by the regression coefficient of the corrected phenotypes on the GEBVs [34].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Heritability of Conformation Traits in Jersey Cows

Phenotypic data for six reproduction-related conformation traits were obtained from 1631 Jersey cattle. Following the removal of outliers and missing values, descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Overall, most traits exhibited skewness and kurtosis values near zero, indicating distributions that were approximately normal. However, BD displayed notably high kurtosis (2.24) and positive skewness (0.48), reflecting a leptokurtic and right-skewed distribution. Heritability estimates for the conformation traits varied from low to moderate, ranging between 0.05 and 0.62. Specifically, BD showed the lowest heritability (0.05 ± 0.02), while ST exhibited the highest (0.62 ± 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for six conformation traits of Jersey Cattle.

3.2. Genetic and Phenotypic Correlations Among Conformation Traits

Table 2 presents the estimated genetic and phenotypic correlations among the six conformation traits. Phenotypically, the strongest positive correlation was observed between BQ and RW (0.208), whereas the strongest negative correlation was between RW and BD (−0.263). Genetically, BQ and RW also showed the strongest positive correlation (0.575), while the strongest negative correlation was identified between RA and BD (−0.533). Overall, genetic correlations were generally consistent with phenotypic correlations in both direction and magnitude. However, a notable exception was the association between BD and RW, which was negative phenotypically (r = −0.263) but positive genetically (r = 0.359). Furthermore, LS demonstrated consistently weak correlations with most other traits at both the genetic and phenotypic levels.

Table 2.

Genetic correlations (upper diagonal) and pairwise Pearson phenotypic correlations (lower diagonal) of conformation traits.

3.3. Impact of Conformation Traits on Reproductive Performance in Jersey Cows

The effects of conformation traits on reproductive performance in Jersey cattle are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4. For reproductive traits approximating continuous distributions (AFS, AFC, GL and BiW), multiple linear regression models based on adjusted phenotypes revealed significant and trait-specific associations with conformation traits (Table 3). In the model for AFS, both BD and RW exhibited positive regression coefficients, whereas ST showed a negative association. Similarly, for AFC, ST, BD and RW were all highly significant predictors (p < 0.001). GL was significantly influenced by ST (p < 0.01), BD (p < 0.001) and RW (p < 0.001). Regarding BiW, significant positive effects were observed for ST (p < 0.001), LS (p < 0.05), and BQ (p < 0.001), while BD and RW were not retained as significant in the final model. For the ordinal reproductive traits CE and AIS, we further applied ordinal mixed models to assess conformation effects (Table 4). The final models identified RA as a significant predictors of CE, while BD and RW were retained as significant predictors of AIS. Overall, these findings indicate that functional type provides informative predictors of reproductive performance in this Jersey population.

Table 3.

T-test and F-test of regression coefficient (reproductive performance).

Table 4.

Effects of conformation traits on CE and AIS evaluated by ordinal mixed models.

The correlation analyses further elucidated these relationships (Figure S2). Phenotypically, ST was negatively correlated with AFS and AFC, but positively correlated with GL and BiW. Both BD and RW were associated with multiple reproductive traits: BD positively with AFS, AFC and AIS but negatively with GL and CE, while RW showed positive correlations with AFS, AFC, AIS and BiW (Figure S2A). Genetically, most correlations were low to moderate, with the strongest association being a negative correlation between BD and AFC (Figure S2B).

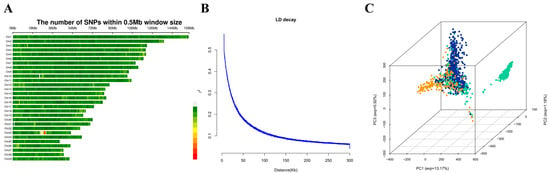

3.4. Marker Information and Population Structure

Following quality control, 10,509,673 SNPs spanning 29 autosomes were retained for subsequent association analyses. These SNPs were relatively evenly distributed across the Jersey cattle chromosomes, although gaps devoid of genotypic data were observed on chromosomes 10, 12, 21, and 23 (Figure 1A). LD decay analysis revealed a decline in mean r2 values with increasing inter-marker distance, reaching approximately 0.08 at an average SNP interval of 200 kb (Figure 1B). The results of the PCA are shown in Figure 1C. The first three principal components (PCs) accounted for 13.17%, 1.18%, and 0.92% of the total genetic variation, respectively, and were subsequently incorporated as covariates in the FarmCPU model for GWAS.

Figure 1.

Genomic characteristics and population structure of the Jersey cattle. (A) Genome-wide SNP distribution across 29 autosomes. The SNP density was calculated per 0.2 Mbp window. (B) LD decay, Mean r2 reached 0.08 at ~200 kb. (C) Principal component analysis was performed on 1578 genotyped Jersey cattle. The green, blue, and orange dots represent individuals from Farm 1, Farm 2, and Farm 3, respectively. The first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3) accounted for 13.17%, 1.18%, and 0.92% of the total genetic variance.

3.5. Genome-Wide Association Study Results

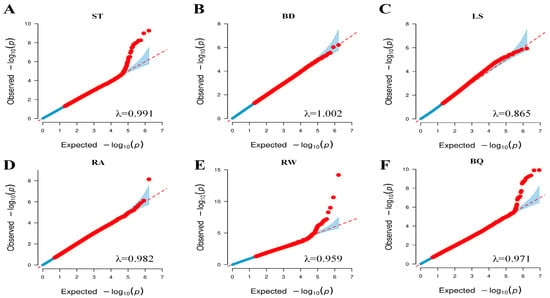

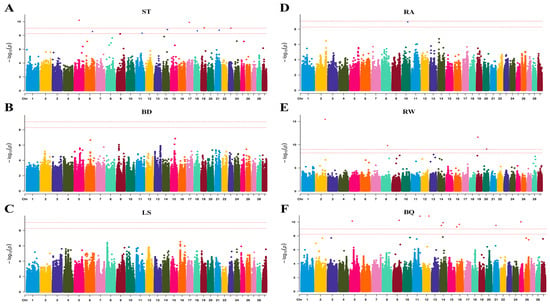

To assess the goodness-of-fit of our association model, quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots showed that the majority of variants had p-values aligning with expectations (genomic inflation λ = 0.865–1.002) (Figure 2). This indicates that the model and methods used in our FarmCPU-based GWAS were appropriate. In this study, 24 SNPs passed the Bonferroni-corrected threshold (0.05/10,509,673) and were significantly associated with four body size traits (Figure 3). In the association analysis, 17 significant SNPs were identified, corresponding to effective candidate genes (Table 5). Two of these SNPs could not be matched to Reference SNP IDs (rsIDs). Six SNPs located on chromosomes 6, 11, 14, 18, 19, and 23 were significantly associated with trait ST. The nearest genes to these SNPs were ANXA3 (81.69 kb), TDRD15 (−106.33 kb), AZIN1 (−55.75 kb), PKD1L3 (within), KRT33A (−14.10 kb), and OR2H1 (0.15 kb). Two SNPs on chromosomes 8 and 19 were associated with trait RW, with the nearest genes being bta-mir-2285br (10.66 kb) and TMEM132E (114.59 kb). One SNP on chromosome 10 was associated with trait BQ and was near the gene KCNH5 (0.39 kb). Additionally, eight SNPs associated with trait BQ were detected on chromosomes 5, 12, 14, 16, 18, 21, and 25. The closest genes to these eight SNPs were LARP4 (13.04), HS6ST3 (within), TBC1D31 (within), U6 (−84.98 kb), TMEM183A (−34.33 kb), PLD5 (−13.92 kb), RCN2 (−43.49 kb), and ERCC4 (7.24 kb). However, no effective candidate genes were identified for the significant SNP loci rs111029085 (BQ), rs208661222m (BQ), rs384114841 (RW), rs110171643 (RW), rs110485738 (ST), rs382718894 (ST), and rs13734261 (ST) in Jersey cattle.

Figure 2.

Q-Q plots for six conformation traits. Panels (A–F) represent ST, BD, LS, RA, RW, and BQ, respectively. Axes display the negative log10 of expected versus observed p-values for all SNPs. Genomic inflation factors (λ) are indicated for each trait.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plots for six conformation traits. Panels (A–F) display results for ST, BD, LS, RA, RW, and BQ, respectively. The x-axis represents chromosomal positions, while the y-axis shows the negative log10 of association p-values. Dashed horizontal lines indicate genome-wide significance thresholds, namely 0.01 and 0.05.

Table 5.

Information on 17 significant SNPs identified in GWAS.

We additionally repeated the GWAS with MAF > 0.01 as a sensitivity analysis (12,452,882 SNPs). Compared with the primary analysis (MAF > 0.05), fewer significant signals were detected (15 SNPs across three traits), with four reproduction-associated candidate genes, two of which overlapped with the main results (Tables S4 and S5 and Figure S3). We therefore retained MAF > 0.05 as the primary threshold and reported the MAF > 0.01 findings in Supplementary Materials.

3.6. Predictive Accuracy and Bias Analysis

To evaluate the potential utility of the identified SNPs in genomic prediction, we integrated six significant SNPs (rs381043519, rs110918513, rs467947475, rs377909538, rs209589627, rs110462030) into a marker-assisted model. These SNPs were selected based on the potential reproductive functions of genes within their 200 kb flanking regions, which are implicated in embryonic development and estrus cycle regulation.

Comparative analysis of prediction accuracy revealed that the marker-assisted model outperformed the single-trait animal model for AFS, AFC, AIS, and GL, whereas it underperformed for BiW (Table 6). Both models showed poor predictive ability for CE, with high bias estimates for AIS and CE indicating suboptimal fit. These results demonstrate that the inclusion of conformation trait-associated SNPs can enhance prediction for specific reproductive traits, although the overall benefit remains limited.

Table 6.

Prediction accuracy and bias of each traits under different models.

4. Discussion

Reproductive efficiency directly influences herd productivity and is therefore crucial for farm profitability and sustainable development. Although integrating fertility traits into breeding goals is a well-established strategy, direct selection for reproductive traits remains challenging due to their low heritability and difficulties in data recording. [35]. Jersey cattle, known for their small size, high milk quality, early sexual maturity, high conception rate, and offspring survival, represent a valuable genetic resource [36]. Understanding the genetic basis of their favorable reproductive characteristics is essential for breed improvement and may also provide insights applicable to other dairy breeds. Presently, China’s Jersey population remains in the early stages of introduction and local breeding programs, where limited pedigree and reproductive records impede direct genetic selection for fertility traits. Notably, accumulating evidence supports significant genetic correlations between specific conformation traits and reproductive performance [37]. These objectively measurable conformation traits may offer potential supplementary selection criteria for enhancing genetic evaluations of fertility in data-limited contexts [38]. Therefore, this study aimed to systematically evaluate the potential of conformation traits as predictors for reproductive performance. We estimated genetic parameters, performed GWAS, and evaluated the practical utility of significant variants via genomic prediction, thereby establishing an integrated genetic foundation for future selection strategies.

Currently, among conformation traits, the rump traitsexert the most significant influence on reproductive performance, including lumbar strength, RA, and RW [37]. In China’s dairy cattle classification system, rump traits constitute 10% of the total score, while LS accounts for 8% within the body capacity category (18% weighting) [39]. This study estimated heritability of LS in Jersey cattle at 0.20, which aligns with Wiggans et al.’s reported estimate (0.21) [40] for Jersey cattle but is lower than Chinese Holstein values (0.25–0.38) [37,41]. LS evaluates structural soundness of the loin through vertebral depression or arching, which affects visceral suspension and birth canal stability, thereby influencing CE and calf survival. However, we detected no significant genetic correlation between LS and CE in Jersey cattle, contrasting with the moderate negative correlation (approximately −0.11) observed in Holsteins [41]. This discrepancy may stem from Jersey cattle’s inherently compact conformation and well-developed hindquarter structure, where LS scores may not fully reflect functional support capacity. Moreover, Jersey cattle’s generally favorable CE likely the contribute to nonsignificant correlations. Notably, LS showed a genetic correlation of −0.24 with AIS, indicating Jersey cattle with stronger LS require fewer inseminations. A robust loin structure also facilitates body condition maintenance in higher lactations, enhancing durability and longevity [42]. RA and RW reflect pelvic architecture, which plays a critical role in calving ease and calf viability [43]. Optimal pelvic conformation (broad with moderate slope) promotes unassisted calving, reduces dystocia risk, and facilitates postpartum fluid expulsion, thereby decreasing reproductive disorders and metritis incidence [44]. In this study, heritability estimates for RA (0.16) and RW (0.33) in Jersey cattle were moderate to low, consistent with ranges reported in Holsteins [39], though slightly differing from some previous Jersey-specific estimates [40]. Genetically, both RW and RA were negatively correlated with CE, while RA showed no significant association with BiW. Notably, RW and RA were also correlated with AFC and AFS, and RW exhibited a negative genetic correlation with GL.These findings align with Royal et al. [11] and Carthy et al. [9], who reported genetic correlations between RW and both the onset of luteal activity (−0.25) and early ovulation (0.55). Together, these results demonstrate intrinsic links between pelvic development and reproductive maturation processes in Jersey cattle.

Beyond rump traits, this study revealed genetic correlations between ST, BD, BQ and reproductive performance, particularly with AFC. Multiple regression further confirmed these conformation traits as significant predictors of reproductive outcomes, with RW consistently influencing multiple traits. Phenotypically, Jersey cattle with greater stature, deeper body depth, and stouter skeletal structure exhibited advanced development, leading to earlier insemination and higher calf birth weights. These observations aligned well with the phenotypic associations identified for AFC, AFS, and BiW. Heritability estimates for ST (0.62) and BQ (0.31) were higher than typical dairy cattle ranges (ST: 0.32–0.53; BQ: 0.05–0.30), whereas BD (0.05) was lower (0.10–0.17) [39]. Most of the six conformation traits analyzed exhibited moderate-to-strong genetic correlations and highly significant phenotypic correlations, with largely consistent directional trends. Given that the conformation traits were assessed primarily in primiparous Jersey cattle, ST, BD, and BQ are considered particularly relevant for selecting well-developed individuals with early breeding potential [45]. In contrast, in mature cows, body development should be moderated, particularly in BD and BQ, to prevent oversized conformation and associated health risks such as metabolic and reproductive disorders [46].

The accuracy of GWAS is influenced by adequate control of population structure and characterization of LD patterns [47]. Our analysis identified three genetic subpopulations reflecting the diverse origins of the cattle, and the first three principal components (collectively explaining 15.27% of genetic variation) were included as covariates to control for stratification. LD decayed rapidly in this Jersey population, with mean r2 dropping to approximately 0.08 at 200 kb—a faster rate than reported in Holstein cattle [48] and Iranian water buffalo [49], suggesting greater genetic diversity or distinct demographic history [50]. This rapid decay highlights the value of using high-density SNP data, such as the 10.5 million imputed markers analyzed here. We employed the FarmCPU model, which iteratively combines fixed and random effect models to improve detection power and control false positives in structured populations [51]. Its efficacy in handling complex architectures has been demonstrated in crops and other species [52,53], supporting its use in this study.

With these methodological foundations laid, the GWAS identified 24 significant SNPs associated with four conformation traits. Functional candidate genes were subsequently screened within 200 kb upstream and downstream of these SNPs, leading to the identification of 14 candidate genes in proximity to the significant loci. Functional characterization revealed that the identified genes predominantly cluster into two categories: those implicated in reproductive processes and those associated with metabolic regulation. Among these, genes with reproductive functions are of particular interest. The reproductive candidate genes associated with ST include AZIN1, which influences bovine endometrial microenvironments during ovulation via polyamine metabolism pathways [54,55]. Also linked to ST is KRT19, which is highly expressed in the epididymis and sperm of fertile bulls and is associated with sperm acrosomal integrity and membrane function [56,57]; it is also implicated in placental development post-fertilization [56,58]. In females, it serves as a marker for key gonadal development cells (e.g., GREL cells and ovarian surface epithelia) [59], participating in ovarian development, folliculogenesis [60], reproductive tract formation [61], and endometrial function [62], with its expression levels varying across reproductive stages [60]. It is also downregulated in bovine blastocysts derived from vitrified morulae [63]. KRT35, reported to be upregulated in non-obstructive azoospermia [64], also functions in estrogen-mediated hair follicle development [65] and is downregulated in the bovine endometrium during the mid-luteal phase [66]. The association of these reproductive genes with ST may point to pleiotropic effects where genetic variants influencing skeletal frame size also co-regulate reproductive tissue development or function. Regarding RW, bta-mir-2285br was identified and is known to associate with early follicular development in the bovine estrous cycle [67], suggesting a possible genetic link between pelvic width and ovarian physiology. For RA, the significant SNP lay within KCNH5, a gene specifically expressed in human placenta [68] whose protein family participates in multiple physiological processes including cell cycle regulation, proliferation control and hormone release from endocrine cells [69]; this provides a plausible molecular basis for how pelvic angle might influence calving ease. Finally, multiple genes related to BQ have direct reproductive roles. OR2H1, enriched in testis-derived cells, mediates sperm chemotaxis [70]. HS6ST3 shows significant correlations with reproductive traits including mating-to-conception intervals and AFS [71]; its biological functions in heparan sulfate biosynthesis [71] are essential for embryogenesis, growth factor signaling [72] and mesoderm formation. ERCC4 maintains genomic stability in early embryos [73] and exhibits reduced expression in infertile human sperm [74]. Together, these genes influence key reproductive processes including sperm quality, ovarian function, endometrial receptivity, and embryonic development.

Another group of genes is associated with lipid metabolism, adipogenesis, and related physiological processes. several metabolism-related genes were identified for ST. ANXA3 regulates adipogenesis and metabolic processes [75,76,77], directly influencing body weight dynamics [78]. PKD1L3 participates in glucose and lipid metabolism, where missense variants alter triglyceride levels [79]. TDRD15 modulates adipose function and spermatogenesis [80,81], with documented upregulation in mature equine testes [82]. KRT33A, a keratin gene, influences claw disorders in Holsteins [83,84]. This cluster of associations may reflect a herd-specific phenomenon where individuals with high ST were more prone to over-conditioning under the prevailing management. For RW, TMEM132E may associate with metabolic disorders [85]. Genes associated with BQ include the putative obesity gene PLD5 [86] and RCN2, which contributes to osteogenesis [87] and suppresses appetite-mediated obesity through circadian rhythm modulation [88]. The detection of these metabolic genes, particularly for ST and BQ, aligns with the documented susceptibility of Jersey cattle to energy imbalance and metabolic disorders. This suggests that these conformation traits also capture meaningful genetic variation in energy balance and fat deposition within this breed.

Lower MAF thresholds may help capture low-frequency variants with potentially larger effects [89], and previous studies have reported additional loci when applying less stringent MAF filters. To evaluate whether such signals could also be informative in our Jersey population, we compared GWAS results using MAF > 0.01 and MAF > 0.05. The MAF > 0.01 analysis identified several additional candidate genes, including NTRK2 [90] and CEP152 [91], both of which have plausible links to reproductive biology. However, the overlap of key genes between the two thresholds was limited, and the lower cutoff did not increase the number of robust, consistently interpretable signals across traits. Given that our primary objective is to identify stable and biologically meaningful loci that connect conformation with reproduction, we therefore retained MAF > 0.05 as the main threshold and present the MAF > 0.01 results as supportive evidence highlighting potential low-frequency candidates that warrant further validation.

This study systematically demonstrates, through both genetic correlation analysis and regression analyses, that conformation traits possess significant predictive value for reproductive performance. More importantly, by utilizing these objectively measurable conformation traits as a bridge, we successfully identified multiple reproduction-related SNPs and candidate genes via GWAS, highlighting the pivotal role of conformation traits in elucidating the genetic basis of reproduction. However, several limitations must be acknowledged: subjectivity in scoring and moderate-to-low genetic correlations introduce noise and constrain predictive accuracy [92], and SNPs identified primarily affect conformation with limited direct impact on reproduction. While these considerations temper expectations and warrant cautious implementation, they do not diminish the important status of conformation traits in breeding practice. Therefore, conformation traits should be regarded as valuable supplementary indicators in genetic evaluations of reproductive performance, particularly offering unique value in populations with incomplete reproductive records [37]. In summary, this research not only establishes reliable associations between conformation traits and reproductive efficiency, but more significantly, through this strategy, identifies several genomic regions and candidate genes of considerable biological importance, providing new targets for marker-assisted selection in Jersey cattle and laying the groundwork for balanced breeding strategies that integrate high productivity with superior fertility.

5. Conclusions

This study provides substantial evidence that selective breeding for improved body conformation could contribute to enhanced reproductive performance in Jersey cattle. Beyond traditional rump traits (LS, RA, RW), ST, BQ, and BD were identified as potential indicators for assessing reproductive efficiency, particularly early reproductive potential. Our analyses revealed significant phenotypic and genetic correlations between conformation and reproductive traits, supporting their functional linkage. The estimated heritabilities for conformation traits ranged from low (BD, RA) to high (ST), indicating their potential for genetic improvement. Through GWAS, we identified 24 significant SNPs associated with four key conformation traits, and functional characterization of nearby genes revealed two distinct groups of candidates: seven genes (AZIN1, OR2H1, HS6ST3, ERCC4, KCNH5, KRT19, KRT35) implicated in reproductive processes, and five genes (ANXA3, TDRD15, PKD1L3, TMEM132E, PLD5) associated with metabolic regulation. These findings collectively provide insights into the shared genetic architecture between conformation and reproduction. Collectively, these findings offer a genetic basis for exploring marker-assisted selection to enhance reproductive efficiency in Jersey cattle breeding.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture16010031/s1, Figure S1: Model selection for reproductive traits based on multiple linear regression and ordinal mixed models; Figure S2: Phenotypic correlations between conformation traits and reproductive performance; Figure S3: Manhattan plots for six conformation traits (MAF > 0.01); Table S1: Descriptive statistics for 6 reproduction traits of Jersey Cattle; Table S2: Genetic correlations, phenotypic correlations and heritability estimations of reproduction traits; Table S3: Genes within 200 kb of SNPS significantly associated with conformation traits; Table S4: Information on 15 significant SNPs identified in GWAS (MAF > 0.01); Table S5: Genomic inflation factors for the Genome-Wide Association Study Sensitivity Analysis (MAF > 0.01).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and X.L.; Methodology, T.Z.; Software, H.J.; Validation, T.Z., H.J. and H.Z.; Formal Analysis, T.Z.; Investigation, M.N., Z.Z., Z.H. and Z.S.; Resources, Z.Y.; Data Curation, T.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, Z.Y. and X.L.; Visualization, T.Z.; Supervision, Z.Y.; Project Administration, T.Z. and X.L.; Funding Acquisition, Z.Y. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following funding sources: the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1300102-05), the Jiangsu Province Seed Industry Revitalization “Unveiling and Leading” Project (JBGS [2021]115), the Jiangsu Province Key Research and Development Project (BE2023329), the Jiangsu Province Graduate Research and Practice Innovation Program (KYCX24_3806), the Natural Science Foundation of China (32402712), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240914).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yangzhou University (SYXK (SU)2022-0044 15 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author as they are currently being used in ongoing research projects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ST | stature |

| BD | body depth |

| LS | loin strength |

| RA | rump angle |

| RW | rump width |

| BQ | bone quality |

| AFC | Age at First Calving |

| GL | Gestation Length |

| CE | calving ease |

| EO | early ovulation |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| AFS | Age at First Service |

| AIS | Number of Artificial Inseminations per Successful Conception |

| BiW | Calf Birth Weight |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

| QC | quality control |

| MAF | minor allele frequency |

| HWE | Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium |

| AI-REML | Average Information Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| ssGBLUP | single-step genomic best linear unbiased prediction |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| FarmCPU | Fixed and random model Circulating Probability Unification |

| QTNs | quantitative trait nucleotides |

| PVE | phenotypic variance explained |

| GEBVs | genomic estimated breeding values |

| rsIDs | Reference SNP IDs |

References

- Gonzalez-Pena, D.; Vukasinovic, N.; Brooker, J.J.; Przybyla, C.A.; Baktula, A.; DeNise, S.K. Genomic evaluation for wellness traits in US Jersey cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1735–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, I.; Rahman, M.; Karunakaran, M.; Gayari, I.; Baneh, H.; Mandal, A. Genetic relationships between reproductive and production traits in Jersey crossbred cattle. Gene 2024, 894, 147982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Sun, H.; Ahmad, M.J.; Ghanem, N.; Abdel-Shafy, H.; Du, C.; Deng, T.; Mansoor, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Genetic Features of Reproductive Traits in Bovine and Buffalo: Lessons From Bovine to Buffalo. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 617128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Zotto, R.; De Marchi, M.; Dalvit, C.; Cassandro, M.; Gallo, L.; Carnier, P.; Bittante, G. Heritabilities and genetic correlations of body condition score and calving interval with yield, somatic cell score, and linear type traits in Brown Swiss cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 5737–5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagusiak, W.; Ptak, E.; Otwinowska-Mindur, A.; Zarnecki, A. Genetic relationships of body condition score and locomotion with production, type and fertility traits in Holstein-Friesian cows. Animal 2023, 17, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglior, F.; Fleming, A.; Malchiodi, F.; Brito, L.F.; Martin, P.; Baes, C.F. A 100-Year Review: Identification and genetic selection of economically important traits in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10251–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anas, M.; Zhao, B.; Yu, H.; Dahlen, C.R.; Swanson, K.C.; Ringwall, K.A.; Hulsman Hanna, L.L. Multi-trait phenotypic modeling through factor analysis and bayesian network learning to develop latent reproductive, body conformational, and carcass-associated traits in admixed beef heifers. Front. Genet. 2025, 16, 1551967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makgahlela, M.L.; Mostert, B.E.; Banga, C.B. Genetic relationships between calving interval and linear type traits in South African Holstein and Jersey cattle. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 39, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthy, T.R.; Ryan, D.P.; Fitzgerald, A.M.; Evans, R.D.; Berry, D.P. Genetic relationships between detailed reproductive traits and performance traits in Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dorp, T.E.; Dekkers, J.C.; Martin, S.W.; Noordhuizen, J.P. Genetic parameters of health disorders, and relationships with 305-day milk yield and conformation traits of registered Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 2264–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal, M.D.; Pryce, J.E.; Woolliams, J.A.; Flint, A.P.F. The genetic relationship between commencement of luteal activity and calving interval, body condition score, production, and linear type traits in Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 3071–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, M.A.; Burke, C.R.; Steele, N.; Pryce, J.E.; Meier, S.; Amer, P.R.; Phyn, C.V.C.; Garrick, D.J. Genome-wide association study of age at puberty and its (co)variances with fertility and stature in growing and lactating Holstein-Friesian dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 3700–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernooij, J.; de Munck, F.; van Nieuwenhuizen, E.; Webb, E.; Jonker, H.; Vos, P.; Holm, D. Reliability of pelvimetry is affected by observer experience but not by breed and sex: A cross-sectional study in beef cattle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2020, 55, 1592–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadati, E.; Kennedy, B.W.; Burnside, E.B. Relationships Between Conformation and Reproduction in Holstein Cows: Type and Calving Performance. J. Dairy Sci. 1985, 68, 2639–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbs Cortes, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J. Status and prospects of genome-wide association studies in plants. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, L.; Takeda, H.; Lin, L.; Druet, T.; Arias, J.A.; Baurain, D.; Cambisano, N.; Davis, S.R.; Farnir, F.; Grisart, B.; et al. Variants modulating the expression of a chromosome domain encompassing PLAG1 influence bovine stature. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, T.; Tiplady, K.; Lopdell, T.; Johnson, T.; Snell, R.G.; Spelman, R.J.; Davis, S.R.; Littlejohn, M.D. Functional confirmation of PLAG1 as the candidate causative gene underlying major pleiotropic effects on body weight and milk characteristics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, M.R.; Nguyen, L.T.; Porto Neto, L.R.; Reverter, A.; Moore, S.S.; Lehnert, S.A.; Thomas, M.G. Polymorphisms and genes associated with puberty in heifers. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, G.; Hoglund, J.K.; Guldbrandtsen, B.; Lund, M.S. Loci associated with adult stature also affect calf birth survival in cattle. BMC Genet. 2015, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No. T/JAASS 143–2024; Code of Technology of Type Classification in Jersey Cow. Jiangsu Association of Agricultural Sciences: Nanjing, China, 2024.

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Gao, Y.; Canela-Xandri, O.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Cai, W.; Li, B.; Xiang, R.; Chamberlain, A.J.; Pairo-Castineira, E.; et al. A multi-tissue atlas of regulatory variants in cattle. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 1438–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinacci, S.; Ribeiro, D.M.; Hofmeister, R.J.; Delaneau, O. Efficient phasing and imputation of low-coverage sequencing data using large reference panels. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, P.G. Correction: Iterative Usage of Fixed and Random Effect Models for Powerful and Efficient Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1005957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Multiple significance tests: The Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995, 310, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Weedon, M.N.; Purcell, S.; Lettre, G.; Estrada, K.; Willer, C.J.; Smith, A.V.; Ingelsson, E.; O’Connell, J.R.; Mangino, M.; et al. Genomic inflation factors under polygenic inheritance. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 19, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Chasman, D.I.; Smith, J.D.; Mora, S.; Ridker, P.M.; Nickerson, D.A.; Krauss, R.M.; Stephens, M. A multivariate genome-wide association analysis of 10 LDL subfractions, and their response to statin treatment, in 1868 Caucasians. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.S.; Porto-Neto, L.R.; Reverter-Gomez, T.; Olasege, B.S.; Sajid, M.R.; Wockner, K.B.; Tan, A.W.L.; Fortes, M.R.S. Utility of multi-omics data to inform genomic prediction of heifer fertility traits. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaglen, S.A.E.; Coffey, M.P.; Woolliams, J.A.; Wall, E. Direct and maternal genetic relationships between calving ease, gestation length, milk production, fertility, type, and lifespan of Holstein-Friesian primiparous cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 4015–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yan, F.; Mi, H.; Lv, X.; Wang, K.; Li, B.; Jin, T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Huang, X.; et al. N-Carbamoylglutamate Supplementation on the Digestibility, Rumen Fermentation, Milk Quality, Antioxidant Parameters, and Metabolites of Jersey Cattle in High-Altitude Areas. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 848912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Abdalla, I.M.; Nazar, M.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, T.; Yang, Z. Genome-Wide Association Study on Reproduction-Related Body-Shape Traits of Chinese Holstein Cows. Animals 2021, 11, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walser, F.; Sauter-Louis, C.; Nuss, K. Measurement of joint angles for the objective assessment of limb conformation in dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 9694–9705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, M.; Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; Lu, X. Genome-Wide Association Study as an Efficacious Approach to Discover Candidate Genes Associated with Body Linear Type Traits in Dairy Cattle. Animals 2024, 14, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggans, G.R.; Gengler, N.; Wright, J.R. Type trait (Co)variance components for five dairy breeds. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 2324–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Ismail, M.K.; Brito, L.F.; Miller, S.P.; Sargolzaei, M.; Grossi, D.A.; Moore, S.S.; Plastow, G.; Stothard, P.; Nayeri, S.; Schenkel, F.S. Genome-wide association studies and genomic prediction of breeding values for calving performance and body conformation traits in Holstein cattle. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2017, 49, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, B.M.; Wolfe, C.W.; Weigel, K.A.; Peñagaricano, F. Effects of type traits, inbreeding, and production on survival in US Jersey cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 4825–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein-Zadeh, N.G. Effects of main reproductive and health problems on the performance of dairy cows: A review. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 11, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogalski, Z.; Piwczynski, D.; Nogalska, A. Clinical applicability of external and internal body dimensions in predicting dystocia in late-gestation Holstein-Friesian heifers. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2024, 59, e14506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, S.; Albuquerque, L.G. Estimates of genetic correlations between days to calving and reproductive and weight traits in Nelore cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 1511–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manafiazar, G.; Goonewardene, L.; Miglior, F.; Crews, D.H.; Basarab, J.A.; Okine, E.; Wang, Z. Genetic and phenotypic correlations among feed efficiency, production and selected conformation traits in dairy cows. Animal 2016, 10, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, Z.; Gao, H.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y. PCA-Based Multiple-Trait GWAS Analysis: A Powerful Model for Exploring Pleiotropy. Animals 2018, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargolzaei, M.; Schenkel, F.S.; Jansen, G.B.; Schaeffer, L.R. Extent of linkage disequilibrium in Holstein cattle in North America. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 2106–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhber, M.; Shahrbabak, M.M.; Sadeghi, M.; Shahrbabak, H.M.; Stella, A.; Nicolzzi, E.; Williams, J.L. Study of whole genome linkage disequilibrium patterns of Iranian water buffalo breeds using the Axiom Buffalo Genotyping 90K Array. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, G.M.; Barria, A.; Correa, K.; Caceres, G.; Jedlicki, A.; Cadiz, M.I.; Lhorente, J.P.; Yanez, J.M. Genome-Wide Patterns of Population Structure and Linkage Disequilibrium in Farmed Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusmec, A.; Schnable, P.S. FarmCPUpp: Efficient large-scale genomewide association studies. Plant Direct 2018, 2, e00053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Yang, J.; Schnable, J.C. Optimising the identification of causal variants across varying genetic architectures in crops. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwell, J.W.; Mergoum, M.; Subedi, M.; Sapkota, S.; Ghimire, B.; Lopez, B.; Buck, J.W.; Bahri, B.A. Discovering leaf and stripe rust resistance in soft red winter wheat through genome-wide association studies. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Contreras, A.J.; Ramos-Molina, B.; Cremades, A.; Penafiel, R. Antizyme inhibitor 2: Molecular, cellular and physiological aspects. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos Rdos, S.; Mesquita, F.S.; D’Alexandri, F.L.; Gonella-Diaza, A.M.; Papa Pde, C.; Binelli, M. Regulation of the polyamine metabolic pathway in the endometrium of cows during early diestrus. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2014, 81, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrachina, F.; Battistone, M.A.; Castillo, J.; Mallofre, C.; Jodar, M.; Breton, S.; Oliva, R. Sperm acquire epididymis-derived proteins through epididymosomes. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Xiong, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, S.; Cao, M.; Kang, Y.; Bao, P.; Pei, J.; Guo, X. Comparative Analysis of Epididymis Cauda of Yak before and after Sexual Maturity. Animals 2023, 13, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, S.; Ramya, L.; Parthipan, S.; Swathi, D.; Binsila, B.K.; Kolte, A.P. Deciphering the complexity of sperm transcriptome reveals genes governing functional membrane and acrosome integrities potentially influence fertility. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 385, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hummitzsch, K.; Bastian, N.A.; Hartanti, M.D.; Wan, Q.; Irving-Rodgers, H.F.; Anderson, R.A.; Rodgers, R.J. Isolation, culture, and characterisation of bovine ovarian fetal fibroblasts and gonadal ridge epithelial-like cells and comparison to their adult counterparts. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummitzsch, K.; Hatzirodos, N.; Irving-Rodgers, H.F.; Hartanti, M.D.; Perry, V.E.A.; Anderson, R.A.; Rodgers, R.J. Morphometric analyses and gene expression related to germ cells, gonadal ridge epithelial-like cells and granulosa cells during development of the bovine fetal ovary. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, G.R.; Kurita, T.; Cao, M.; Shen, J.; Robboy, S.; Baskin, L. Molecular mechanisms of development of the human fetal female reproductive tract. Differentiation 2017, 97, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, G.; Tian, Y.; Kang, S. Identification of Key Differentially Methylated/Expressed Genes and Pathways for Ovarian Endometriosis by Bioinformatics Analysis. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 1630–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Singh, J.; Dufort, I.; Robert, C.; Dias, F.C.F.; Anzar, M. Transcriptomic difference in bovine blastocysts following vitrification and slow freezing at morula stage. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi Karoii, D.; Azizi, H.; Darvari, M.; Qorbanee, A.; Hawezy, D.J. Identification of novel cytoskeleton protein involved in spermatogenic cells and sertoli cells of non-obstructive azoospermia based on microarray and bioinformatics analysis. BMC Med. Genom. 2025, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Lu, Q.; Ma, S.; Mamat, N.; Tang, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Anwar, A.; Lu, Y.; Ma, Q.; et al. Proteomics Reveals the Role of PLIN2 in Regulating the Secondary Hair Follicle Cycle in Cashmere Goats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.G.; Hosoe, M.; Kizaki, K.; Fujii, S.; Kanahara, H.; Takahashi, T.; Sakumoto, R. Differential gene expression profiling of endometrium during the mid-luteal phase of the estrous cycle between a repeat breeder (RB) and non-RB cows. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2017, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salilew-Wondim, D.; Ahmad, I.; Gebremedhn, S.; Sahadevan, S.; Hossain, M.D.; Rings, F.; Hoelker, M.; Tholen, E.; Neuhoff, C.; Looft, C.; et al. The expression pattern of microRNAs in granulosa cells of subordinate and dominant follicles during the early luteal phase of the bovine estrous cycle. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaulay, E.C.; Roberts, H.E.; Cheng, X.; Jeffs, A.R.; Baguley, B.C.; Morison, I.M. Retrotransposon hypomethylation in melanoma and expression of a placenta-specific gene. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shan, Y.; Pei, D. Mechanism underlying delayed rectifying in human voltage-mediated activation Eag2 channel. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicuolo, F.; Teveroni, E.; Devigili, A.; Gasparini, C.; Urbani, A.; Ghi, T.; Pontecorvi, A.; Milardi, D.; Mancini, F. Exploring OR2H1-Mediated Sperm Chemotaxis: Development and Application of a Novel Microfluidic Device. Cells 2025, 14, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardana, J.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; McNaughton, L.R.; Hickson, R.E. Genomic Regions Associated with Milk Composition and Fertility Traits in Spring-Calved Dairy Cows in New Zealand. Genes 2023, 14, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirn-Safran, C.B.; D’Souza, S.S.; Carson, D.D. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans and their binding proteins in embryo implantation and placentation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2008, 19, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, K.Y.; Saenen, N.D.; Tarantini, L.; Janssen, B.G.; Lefebvre, W.; Vanpoucke, C.; Bollati, V.; Nawrot, T.S. Placental promoter methylation of DNA repair genes and prenatal exposure to particulate air pollution: An ENVIRONAGE cohort study. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e174–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, S.; Parrella, A.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Palermo, G.D. Genetic and epigenetic profiling of the infertile male. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.C.; Lin, Y.L.; Kuo, C.F. Effect of high-fat diet on hepatic proteomics of hamsters. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1869–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Ito, Y.; Sato, A.; Hosono, T.; Niimi, S.; Ariga, T.; Seki, T. Annexin A3 as a negative regulator of adipocyte differentiation. J. Biochem. 2012, 152, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, T.; Enrich, C.; Rentero, C.; Buechler, C. Annexins in Adipose Tissue: Novel Players in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Shin, C.H.; Choi, M.; Ko, J.M.; Lee, Y.A.; Shim, K.S.; Lee, J.; Yoo, S.D.; Kim, M.; Yu, Y.; et al. Prader-Willi syndrome gene expression profiling of obese and non-obese patients reveals transcriptional changes in CLEC4D and ANXA3. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 38, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.; Zhang, H.; Cheung, C.Y.; Xu, M.; Ho, J.C.; Zhou, W.; Cherny, S.S.; Zhang, Y.; Holmen, O.; Au, K.W.; et al. Exome-wide association analysis reveals novel coding sequence variants associated with lipid traits in Chinese. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, J.; Peng, Z.; Guo, X.; Gao, J. Transcriptomics profiling reveal the heterogeneity of white and brown adipocyte. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2023, 55, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godia, M.; Casellas, J.; Ruiz-Herrera, A.; Rodriguez-Gil, J.E.; Castello, A.; Sanchez, A.; Clop, A. Whole genome sequencing identifies allelic ratio distortion in sperm involving genes related to spermatogenesis in a swine model. DNA Res. 2020, 27, dsaa019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; He, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, D.; Bou, G.; Zhang, X.; Su, S.; Dao, L.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; et al. Identification of piRNAs and piRNA clusters in the testes of the Mongolian horse. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wildermoth, J.E.; Wallace, O.A.; Gordon, S.W.; Maqbool, N.J.; Maclean, P.H.; Nixon, A.J.; Pearson, A.J. Annotation of sheep keratin intermediate filament genes and their patterns of expression. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 20, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solzer, N.; May, K.; Yin, T.; Konig, S. Genomic analyses of claw disorders in Holstein cows: Genetic parameters, trait associations, and genome-wide associations considering interactions of SNP and heat stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 8218–8236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottmann, P.; Ouni, M.; Zellner, L.; Jahnert, M.; Rittig, K.; Walther, D.; Schurmann, A. Polymorphisms in miRNA binding sites involved in metabolic diseases in mice and humans. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aissani, B.; Zhang, K.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Menko, F.H.; Wiener, H.W. Fine mapping of the uterine leiomyoma locus on 1q43 close to a lncRNA in the RGS7-FH interval. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2015, 22, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Hu, B.; Xie, L.Q.; Su, T.; Li, C.J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, X.; Zhou, R.; et al. A mechanosensitive lipolytic factor in the bone marrow promotes osteogenesis and lymphopoiesis. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1168–1182.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.Q.; Hu, B.; Lu, R.B.; Cheng, Y.L.; Chen, X.; Wen, J.; Xiao, Y.; An, Y.Z.; Peng, N.; Dai, Y.; et al. Author Correction: Raptin, a sleep-induced hypothalamic hormone, suppresses appetite and obesity. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, H.; Alliey-Rodriguez, N.; Keedy, S.; Tamminga, C.A.; Sweeney, J.A.; Pearlson, G.; Clementz, B.A.; Keshavan, M.S.; Buckley, P.; Liu, C.; et al. GWAS significance thresholds for deep phenotyping studies can depend upon minor allele frequencies and sample size. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.; Garcia-Rudaz, C.; Dorfman, M.; Paredes, A.; Ojeda, S.R. NTRK1 and NTRK2 receptors facilitate follicle assembly and early follicular development in the mouse ovary. Reproduction 2009, 138, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.A.; Bury, L.; Sharif, B.; Riparbelli, M.G.; Fu, J.; Callaini, G.; Glover, D.M.; Zernicka-Goetz, M. Spindle formation in the mouse embryo requires Plk4 in the absence of centrioles. Dev. Cell 2013, 27, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, V.; Stípková, M.; Lassen, J. Genetic parameters for female fertility, locomotion, body condition score, and linear type traits in Czech Holstein cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 5176–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.