Abstract

Plant parasitic nematodes cause substantial economic losses in agricultural products worldwide. Chemical control remains the predominant strategy among available approaches for nematode management. In recent years, a new generation of synthetic nematicides with distinct biochemical targets and improved selectivity has emerged. However, our understanding of the mechanisms of action, activity spectra, and safety of these new agents remains fragmented and lacks systematic integration. Clarifying their modes of action is essential for both the rational development and effective application of these compounds. This article reviews the characteristics and modes of action of both traditional and innovative nematicides, including organophosphates, carbamates, avermectins, cyclobutrifluram, fluazaindolizine, tioxazafen, fluensulfone, and fluopyram, following the classification by the Insecticide and Fungicide Resistance. This review addresses this gap by critically examining modern nematicides currently in use or under development, highlighting their molecular targets, toxicological considerations, and potential roles in sustainable nematode management.

1. Overview

Plant-parasitic nematodes (PPNs) represent one of the most destructive groups of agricultural pests [1]. comprising more than 200 genera and over 4100 species, and causing annual global yield losses estimated at USD 157 billion [2,3]. Their cryptic lifestyle, exceptionally broad host range, and rapid population growth make PPNs difficult to detect and manage effectively in field conditions. Among them, root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) and cyst nematodes (Heterodera and Globodera spp.) are particularly damaging and remain persistent challenges in modern crop production [4].

Chemical control has been the backbone of nematode management due to its rapid action and cost-effectiveness [5]. However, the portfolio of available nematicides is narrow and heavily dependent on traditional fumigants (e.g., metam sodium, dazomet) and non-fumigant organophosphates or carbamates (e.g., fosthiazate, carbosulfan) [6]. These compounds face substantial limitations. First, many conventional agents exhibit high acute toxicity, limited selectivity, and broad non-target impacts, affecting beneficial soil fauna and microbial communities [7,8]. Second, extensive use has led to regulatory restrictions or phase-outs in multiple regions due to concerns regarding groundwater contamination, air volatility, worker exposure risks, and ecological toxicity [9]. Third, repeated long-term application has contributed to reduced field efficacy and emerging tolerance in several nematode populations [10,11]. Collectively, these constraints have created an urgent demand for safer, more selective, and more sustainable chemistries. To address these limitations, recent years have seen the emergence of a new generation of non-fumigant nematicides—characterized by novel chemical scaffolds or modes of action and already registered or commercially launched in major countries—such as fluazaindolizine, cyclobutrifluram, and trifluenfuronate, all of which exhibit more favorable toxicological and environmental profiles (Table 1). These reduced-risk chemistries provide greater nematode specificity, lower non-target toxicity, and enhanced suitability for integrated pest management [12,13]. Among them, fluazaindolizine acts by disrupting esophageal gland secretions and impairing nematode feeding, representing a clear departure from conventional mechanisms [14]. Trifluenfuronate—developed independently in China—is expected to enter the commercial market soon [15]. Together, these innovations mark a significant shift in nematicide development and highlight the urgent need to reassess the characteristics, mechanisms, and future potential of both traditional and modern nematicides.

Table 1.

Active Ingredients of Novel Chemical Nematicides.

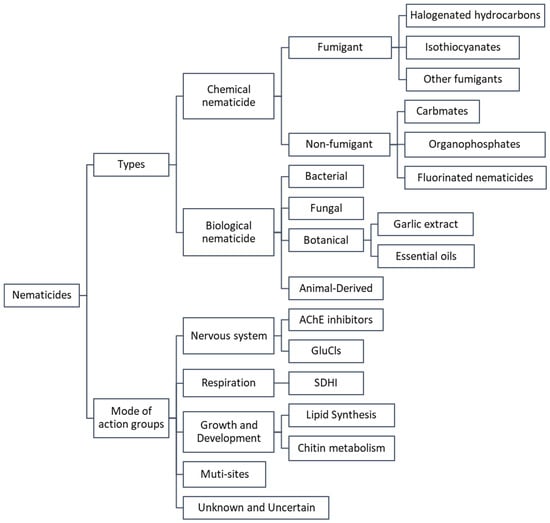

Despite these advancements, the pace of development and research in nematicides continues to lag behind that of fungicides and insecticides. Understanding the mode of action is crucial for the development and effective utilization of new nematicidal compounds. This article aims to review the characteristics and nematicidal mechanisms of both traditional and newly developed nematicides, drawing on the classification principles of the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) and, where applicable, the mode-of-action grouping approaches of the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), and is further informed by a systematic literature review. This classification framework serves as the analytical basis for the subsequent sections, allowing us to systematically compare traditional and modern nematicides in terms of their chemical origin, molecular targets, and toxicological profiles (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The classification of nematicides types and modes of action groups.

Summary based on a systematic literature review, which integrates the classification frameworks of IRAC, FRAC, and EPA with the development trends of novel chemical and biological nematicides over the past decade.

2. Methods

To ensure the scientific rigor, systematic structure, and reproducibility of this review, a structured literature search and screening procedure was conducted. Publications were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection using the keywords “nematicides,” “mode of action,” “plant-parasitic nematodes,” and related terms. The search covered studies published between 1980 and 2024, resulting in 1585 records relevant to nematicides and their mechanisms of action. Only English-language publications were considered.

2.1. Study Selection

An initial screening of titles and abstracts was performed to exclude irrelevant studies. Full texts of the remaining publications were then evaluated in detail. Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- (1)

- peer-reviewed original research or review articles;

- (2)

- clear description of nematicide categories, biochemical or physiological modes of action, field efficacy, or target specificity;

- (3)

- research addressing non-target toxicity, environmental behavior, or applications within integrated pest management (IPM).

Exclusion criteria included studies unrelated to chemical nematicidal action, articles lacking methodological clarity or mechanistic relevance, and reports without primary or structured data. After screening, approximately 90 high-quality studies were retained for detailed synthesis.

2.2. Data Extraction and Synthesis

From each included study, information was extracted regarding nematicide chemical class, target type, biological activity, application methods, activity spectrum, and environmental safety. The synthesis of mechanisms followed classification frameworks established by the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) and the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), and studies were integrated thematically based on mechanistic categories.

Due to substantial heterogeneity across studies in experimental design, metrics of nematicidal activity, and data reporting formats, a quantitative meta-analysis was not performed, and the review is presented as a structured qualitative synthesis.

3. Mode of Action of the Main Nematicide Groups

The development of modern nematicides has shifted from traditional broad-spectrum neurotoxic compounds to structurally defined chemistries with precise molecular targets. Among currently commercialized active ingredients, only a limited number of targets have been rigorously validated, and these fall into several key pathways: (1) neural targets, including acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibited by organophosphates and carbamates, and glutamate-gated chloride channels (GluCls) modulated by avermectins; (2) mitochondrial respiratory complex II (succinate dehydrogenase, SDH), inhibited by fluopyram and cyclobutrifluram, representing one of the most successful newly established modes of action; (3) acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) in lipid biosynthesis, targeted by spirotetramat; and (4) ribosomal function, uniquely disrupted by tioxazafen, which defines a distinct mechanistic class. Advances in omics technologies and functional genomics have highlighted several additional pathways with potential for future nematicide discovery, such as neuropeptide signaling, nematode-specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, and chitin synthase/chitinase systems required for eggshell formation and remodeling. These targets show promise due to their specificity, essential roles in nematode biology, and potential advantages for resistance management, although no commercial active ingredients acting on them have yet been realized. Conversely, other biochemical sites—such as additional complexes of the mitochondrial electron transport chain (e.g., complexes I, III, and IV) or highly conserved enzymes of core metabolism—are unlikely to yield practical nematicides due to insufficient selectivity, narrow toxicological windows, or high homology with non-target organisms. In summary, the success of modern nematicides has been driven by a small number of well-validated targets that combine biological selectivity with chemical tractability. The translation of other potential targets into viable products will require robust functional validation, structural elucidation, and high-throughput screening to establish their suitability for nematicide development (Table 2).

Table 2.

Classification of modes of action (MoA) of nematicides.

3.1. Disruption of Nematode Nervous System

The infection of plant roots by plant-parasitic nematodes and the establishment of their feeding sites are governed by neural regulation of muscle movement [16]. The genes responsible for neurotransmission were first identified in Caenorhabditis elegans (Maupas) (Rhabditidae), which serves as a model organism with the most extensively documented cell lineage and neuronal connections of any animal. The nervous system of C. elegans is composed of 302 neurons, among which 75 are motor neurons, including 56 cholinergic and 19 GABAergic neurons. It produces neurotransmitters like those in mammals, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, and neuropeptides [17]. Nematicides such as organophosphates, carbamates, and avermectins primarily target acetylcholinesterase and glutamate-gated chloride channels.

3.1.1. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors (Organophosphates and Carbamates)

Acetylcholine (ACh) is the principal neurotransmitter involved in the motor functions of many organisms, including nematodes [18]. Plant-parasitic nematodes hydrolyze acetylcholine through the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) to halt nerve impulse transmission and regulate muscle activity [19]. Various AChE genes have been identified in different species of plant-parasitic nematodes, including Mi-ace-1 and Mi-ace-2 in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita; Mj-ace-1 in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne javanica [20,21]; Dd-ace-1, Dd-ace-2, and Dd-ace-3 in the sweet potato stem nematode Ditylenchus destructor [22,23]; Hg-ace-2 in the soybean cyst nematode Heterodera glycines [24]; and Bx-ace-1, Bx-ace-2, and Bx-ace-3 in the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus [25,26].

The mode of action of carbamates and organophosphates resembles their insecticidal counterparts. These nematicides inhibit the nematode acetylcholinesterase by forming covalent bonds with the serine residue at the enzyme active site, thereby preventing the breakdown of acetylcholine [27]. This leads to sustained neural excitation in nematodes, resulting in muscle paralysis, compromised movement, and difficulties in feeding and parasitism, ultimately causing their death [28]. Research demonstrated that simultaneous silencing of the Mi-ace-1, Mi-ace-2, and Mi-ace-3 genes through plant-mediated RNA interference significantly reduced gall formation in the roots of transgenic tobacco, thereby diminishing the nematode’s developmental and parasitic capabilities [23]. Similarly, Stevenson et al. reported that silencing the gene encoding acetylcholinesterase (Gp-ace-2) in the potato cyst nematode resulted in its complete paralysis and prevention of infection and completion of its life cycle in host plants [29].

A notable characteristic of these compounds’ effects on nematodes is paralysis or anesthesia, which is reversible rather than lethal. For instance, when the nematodes Aphelenchus avenae and Panagrellus redivivus (a free-living nematode) were treated with phorate, they exhibited minimal movement and significantly reduced acetylcholinesterase activity. However, when these paralyzed nematodes were transferred from the pesticide solution to water, they fully recovered within 48–72 h [30,31]. Thus, the protection afforded by these pesticides to plants is not through the extermination of nematodes but by impairing their nerve functions, inhibiting their ability to invade and feed on plants, disrupting females’ ability to attract males, and thereby delaying their development and reproduction [30]. Traditional carbamate nematicides include carbofuran, aldicarb, and oxamyl, while traditional organophosphate nematicides include fosthiazate and phorate.

3.1.2. Allosteric Modulators of Glutamate-Gated Chloride Channels (Avermectins)

Glutamate serves as a pivotal excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous systems of both vertebrates and invertebrates, acting on specific glutamate receptors embedded in the cell membrane. In invertebrates, a particular inhibitory glutamate receptor exists, whereby glutamate functions as an inhibitory neurotransmitter, binding to these receptors and subsequently initiating the opening of chloride channels. Hence, these receptors are also known as glutamate-gated chloride channels (GluCls) [32]. Research indicates that glutamate-gated chloride channels are exclusive to the central nervous system and muscle cells of invertebrates, such as nematodes and insects, and are absent in vertebrates. Further studies reveal that these channels, beyond their primary role in neurotransmission, are integral to regulating nematode locomotion, feeding, signal perception, and reproductive functions [33,34].

Avermectins are a class of macrocyclic lactone compounds, exhibiting insecticidal, acaricidal, and nematicidal properties. These compounds were jointly developed by Kitasato Institute in Japan and Merck Company in the United States during the late 1970s [35]. Avermectins interact with glutamate-gated chloride channels in a stereoselective manner, specifically modulating the opening of these channels to facilitate the influx of negatively charged chloride ions. This influx maintains the membrane potential in a hyperpolarized state, impeding the membrane’s ability to depolarize, which in turn inhibits neural transmission, culminating in the paralysis and eventual death of the nematode [36,37,38]. The impact of avermectins on nematodes includes the rapid paralysis of movement and pharyngeal pumping, rendering the nematodes incapacitated and unable to feed, ultimately leading to starvation [39]. Laughton et al. demonstrated that by linking the lacZ gene to the promoter of avr-15, both the α2 and β subunits of the glutamate-gated chloride channel were expressed in the nematode’s pharyngeal muscle cells, with a higher prevalence of the α2 subunit in the motor nervous system, aligning with the observed symptoms of movement and pharyngeal paralysis following nematode exposure to the chemicals [40].

3.2. Inhibition of Nematode Respiration

Nematodes lack specialized respiratory organs; instead, they facilitate gas exchange through their body wall via diffusion. Metabolic studies have elucidated that both free-living and plant-parasitic nematodes engage in energy metabolism predominantly through glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Additionally, the glyoxylate cycle is prevalent across many nematode species [41].

Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors (Fluopyram, Cyclobutrifluram)

Fluopyram, a pyridine ethyl benzamide fungicide and nematicide developed by Bayer CropScience, is utilized to control root-knot nematodes on crops such as tomatoes, cucumbers, watermelons, bananas, and tobacco. It has been previously identified as an inhibitor of succinate dehydrogenase in fungi [42]. Research demonstrated that nematode succinate dehydrogenase knockout mutants were more sensitive to exposure of fluopyram, suggesting a similar mode of action in nematodes and marking it as the first nematicide targeting this enzyme [43]. Further studies revealed that other succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors, including boscalid, flutolanil, penthiopyrad, fluxapyroxad, and solatenol, did not exhibit nematicidal activity against root-knot nematodes [44]. This suggests that fluopyram might impact additional targets within nematodes or possess a chemical structure with greater affinity for nematode succinate dehydrogenase compared to other inhibitors. Additionally, fluopyram was found to show reversible nematicidal activity after short-term exposure [45]. Liu et al. reported that fluopyram not only significantly decreased the activities of target enzyme succinate dehydrogenase and antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione S-transferase in C. elegans, but also influenced expression levels of oxidative stress-related genes. The treatment also caused a pronounced increase in reactive oxygen species, malondialdehyde levels, lipofuscin, and lipid accumulation, reflecting changes in genes associated with intestinal damage, cell apoptosis, and lipid accumulation. Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis indicated multiple toxicity-related effects in C. elegans, including oxidative stress, intestinal damage, and cell apoptosis [46].

Cyclobutrifluram, marketed under the brand Tymirium by Syngenta, was launched as a novel nematicide and fungicide [47]. It features a unique formamide structure and is applied to seed and soil, providing significant control efficacy against both nematodes and fungi, particularly Fusarium. The FRAC classifies it as an SDHI fungicide with a phenyl-cyclobutyl-pyridinyl amide structure, while the IRAC places it in Group N-3 for nematicides. Research suggests that cyclobutrifluram shares a similar mode of action with fluopyram, specifically inhibiting the mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase complex [48,49]. This compound has proven effective in controlling Meloidogyne spp., Heterodera spp. in various crops including tomato, cucumber, corn, and sugar beet through seed and soil treatments. Notably, cyclobutrifluram received its first registration in El Salvador in 2022, followed by registration in Argentina. China also approved its registration in 2023.

3.3. Growth and Development Regulation

3.3.1. Lipid Biosynthesis and Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase Inhibitors (Spirotetramat)

Lipid biosynthesis is an important process in most organisms and plant nematodes. Lipid metabolism is crucial for nematodes because lipids not only serve to store and release energy but are also important components of cell membranes. Spirotetramat is a novel cycloketone derivative insecticide developed by Bayer. It exhibits systemic action, moving within the plant both upward and downward. Spirotetramat functions as a lipid biosynthesis inhibitor by impeding the activity of acetyl-CoA carboxylase in pests. This inhibition blocks normal energy metabolism, leading to pest death [50]. It is also registered for controlling sugar beet cyst nematodes worldwide. Vang et al. demonstrated its potential activity as a nematicide, noting that the development of C. elegans was hindered at spirotetramat-enol concentrations as low as 30 ppm [51]. Further studies confirmed that acetyl-CoA carboxylase is the target site of spirotetramat [52,53]. Enzyme assays utilizing radiolabeled bicarbonate revealed that spirotetramat-enol inhibited nematode acetyl-CoA carboxylase activity. This inhibition was directly correlated with developmental delays, which were attributed to reductions in triacylglycerols containing C18, impacting the nematode storage lipids and fatty acid composition. Additionally, silencing of acetyl-CoA carboxylase by RNAi in sugar beet cyst nematodes induced a phenotype similar to that observed with spirotetramat-enol treatment, corroborating the hypothesis that spirotetramat-enol disrupts nematode growth by inhibiting acetyl-CoA carboxylase. ACCase has demonstrated chemical tractability as an effective insecticidal target; however, the high structural similarity between nematode ACCase and its plant counterpart poses substantial selectivity risks, rendering it less favorable than validated nematicidal targets such as SDH and GluCl [54]. Moreover, the lipid metabolic network in nematodes displays considerable redundancy, which may limit the biological vulnerability of this pathway to chemical inhibition. At present, there are virtually no industrial discovery pipelines centered on ACCase as a primary nematicidal target, underscoring its relatively low priority within contemporary nematicide development programs.

3.3.2. Chitin Biosynthesis and Degradation

Chitin is the essential component of the nematode eggshell and pharynx. The disturbance of chitin synthesis or hydrolysis led to nematode embryonic death, laying defective eggs or moulting failure [55,56]. Chitin synthesis and hydrolysis have been used as a target site for the possible development of nematode controlling products disrupting chitin metabolism. The eggshell of nematodes mainly consists of three layers: the outer uterine layer is derived from the egg membrane formed by the fertilized oocyte, the inner layer is a functional lipid layer that regulates osmosis, and the middle layer is a chitin layer with a certain degree of hardness and the thickest layer. The eggshell of Globodera rostochiensis contains about 9% chitin, while the eggshell of Meloidogyne javanica contains nearly 30% chitin [57].

Chitinases and chitin synthases are the two principal groups of enzymes that have evolved to degrade and synthesize chitin, respectively [58]. Most nematode genomes exhibit a variety of chitin synthase and chitinase genes. Five putative chitin synthase genes have been identified in the genome of M. incognita. Additionally, 22 chitinase-related genes have also been discovered in M. incognita [59]. Chitinase can degrade chitin in nematode eggshells and regulate the development of nematode eggs [60]. Disrupting the expression of chitinase genes in nematodes leads to egg hatching failure [61]. The chitinase gene CeCht1 in Caenorhabditis elegans is highly expressed during egg hatching; RNA interference targeting CeCht1 expression can lead to hatching failures and nematode death [62]. Similarly, interfering with the expression of the chitinase genes BxChi1 and BxChi7 in the pine wood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus can delay and prevent egg hatching [63]. Chitinase is vital for the growth and development of nematodes. Some bacteria, such as Paecilomyces lilacinus, are effective biocontrol agents against plant-parasitic nematodes, primarily through their production of chitinases. This activity has been recognized as a crucial mode of action of Paecilomyces lilacinus in controlling root-knot nematodes [64]. By analyzing nematode chitin synthase and chitinase structures and designing enzyme-specific inhibitors, effective strategies for the prevention and control of nematode infestations can be developed. Unlike insects, chitin plays a much less critical structural role in nematodes, resulting in substantially lower biological vulnerability; consequently, this pathway exhibits low selectivity and limited feasibility, and therefore does not represent a viable direction for current innovation in nematicidal chemistry.

3.4. Multi-Site Activity—Fumigants

3.4.1. Halogenated Hydrocarbons

Halogenated hydrocarbons represent one of the earliest classes of nematicides utilized in agricultural production. This category includes methyl bromide, chloropicrin, 1,3-dichloropropene, and a combination of dichloropropene and dichloropropane. It is widely accepted that halogenated hydrocarbons induce nematode toxicity primarily through alkylation or oxidation processes [65]. Initially, nematodes display hyperactivity, which is followed by anesthesia and subsequent death. As alkylating agents, halogenated hydrocarbons react with essential proteins, particularly enzymes that contain hydroxyl and amino groups. This alkylation reaction can inactivate or inhibit the function of these enzymes, ultimately leading to nematode mortality. Another proposed mechanism involves inhibition of cytochrome oxidase in the mitochondrial electron-transport system, which disrupts nematode respiration and results in their death [66].

3.4.2. Isothiocyanates

Isothiocyanate nematicides function as carbamylating agents. Their nematicidal action is hypothesized to result from carbamylation reactions with nucleophilic sites, such as amino, hydroxyl, and sulfhydryl groups, in enzyme molecules [67,68].

Dazomet and metam sodium are precursors that convert into the active substance methyl isothiocyanate in the soil. Dazomet is recognized as a high efficacy, low-toxicity, broad-spectrum soil fumigant. Currently, seven companies in China have registered dazomet for controlling nematodes in crops such as tomato, ginger, strawberry, and tobacco. Dazomet has also been registered in many other countries, including the United States, Japan, and Europe. Metam sodium is a water-soluble pre-plant fumigant. Five companies in China have registered metam sodium for managing root-knot nematodes in tomatoes and cucumbers. Both fumigants inhibit cell division and the synthesis of nucleic acid, and proteins [69], and impede respiration, thereby effectively eradicating root-knot nematodes, weeds, and other pests.

Allyl isothiocyanate is a compound extracted from cruciferous plants and exhibits similar properties and biological activities to methyl isothiocyanate. In the United States, it is marketed under the trade name Dominus by Isagro, primarily for controlling nematodes, weeds, and fungi in soil used for strawberries, vegetables, ornamental plants, and nurseries. In China, allyl isothiocyanate is registered for managing tomato root-knot nematodes. Research indicates that allyl isothiocyanate inhibits mitochondrial complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) and complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) in the maize weevil, leading to cytoskeletal collapse and mitochondrial dysfunction [70,71]. A further study identified cox1 from cytochrome c oxidase as the binding target of AITC, with a potential binding site of ASN511. It is thus speculated that allyl isothiocyanate also impacts nematode mitochondria, causing energy insufficiency, increased production of reactive oxygen species, and ultimately tissue dysfunction [72].

3.4.3. Other Fumigants

Several other fumigants have demonstrated effective control of plant-parasitic nematodes. Cao et al. observed that sulfuryl fluoride exerted a significant control effect on soil nematodes [73]. Results also confirm that sulfuryl fluoride is an effective quarantine treatment for pinewood nematode [74]. Originally registered as an insecticide, sulfuryl fluoride’s mode of action against insects involves disrupting glycolysis, thereby inhibiting fatty acid metabolism within their bodies [75], and exhibiting low toxicity to insect eggs—the dose required to kill eggs is significantly higher than that needed for larvae and adults. The mechanism by which sulfuryl fluoride kills eggs is believed to involve a reduction in oxygen intake [75]. It is hypothesized that the nematicidal mechanism of sulfuryl fluoride is similar to its insecticidal properties, likely by impeding the lipid metabolism in nematodes and thus depriving them of the energy essential for survival. China is the first country to register sulfuryl fluoride as a soil fumigant to control root-knot nematodes for use on strawberry, cucumber, ginger, and tobacco.

Furthermore, studies have shown that the nematicidal activity of dimethyl disulfide is comparable to that of 1,3-dichloropropene [76]. It is determined that the LC50 values for fumigation and contact activity of root-knot nematodes with dimethyl disulfide were 0.086 mg/L and 29.865 mg/L, respectively, and that field fumigation at a concentration of 10 g/m2 effectively controlled root-knot nematodes. Gómez et al. [77] conducted a fumigation trial using dimethyl disulfide in a greenhouse with a 12-year history of root-knot nematode infection. Before treatment, the root-knot nematode population ranged from 364 to 4044 J2 per 100 cm3 of soil. After treatment no nematode juveniles were detected in the soil. Currently, dimethyl disulfide is registered under the trade names Paladin and Accolade by Arkema in the United States, Israel, and several other countries for controlling root-knot nematodes. Dugravot et al. found that dimethyl disulfide controlled pests by inhibiting the production of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), reducing intracellular ATP concentrations, and consequently activating neuronal K-ATP channels, which mediate membrane hyperpolarization and reduced neuronal activity [78]. Further research revealed that through contact and fumigation experiments on root-knot nematodes, dimethyl disulfide interfered with calcium ion channels and affected various complexes of oxidative phosphorylation in respiration [79]. The modes of action differ between contact and fumigation: in contact, dimethyl disulfide damages the surface structure of nematodes, acts as an uncoupler of ATP synthase, and stimulates nematode respiration; in fumigation, dimethyl disulfide penetrates nematodes through the processes of olfactory perception and oxygen exchange, ultimately impacting the respiratory electron transport chain at complex IV or I, coupled with oxidative damage, leading to nematode death.

Fumigants such as DMDS and methyl isothiocyanate precursors exert nematicidal activity through multi-site reactions and nonspecific disruption of cellular components. Because these modes of action lack defined molecular targets, they are not compatible with target-based pesticide design. Therefore, although fumigants remain of practical importance, their inherently non-specific mechanisms do not provide a chemically feasible foundation for the modern development of new selective small-molecule nematicides.

3.5. Unknown or Uncertain Mode of Action

3.5.1. Fluensulfone

Fluensulfone, a novel, low-toxicity fluoroalkenyl thioether nematicide, was discovered by Adama. It was registered in the United States as a non-fumigant nematicide in 2014, and in 2019, Adama registered fluensulfone in China. The commercial product, marketed as Nimitz, is applied as a soil spray to control root-knot nematodes on vegetables and fruits [13].

Fluensulfone acts primarily through contact, reducing nematode activity and leading to paralysis. Nematode feeding ceases within one hour of exposure, and their ability to infect and lay eggs is significantly diminished. It is effective against a variety of plant-parasitic nematodes, particularly root-knot nematodes, and serves as an environmentally friendly alternative to many traditional carbamate and organophosphate nematicides. Kearn et al. demonstrated that nematode mutants highly resistant to ivermectin and aldicarb remained highly sensitive to fluensulfone. They noted that fluensulfone’s mode of action likely differs from that of ivermectin, which targets glutamate-gated chloride channels, and aldicarb, which inhibits acetylcholinesterase [80]. Further research revealed that the nematicidal effects of fluensulfone evolve over time, beginning with immediate impacts on nematode movement and progressing to extensive metabolic damage, an inability to store lipids, and ultimately death. Long-term exposure to low concentrations of fluensulfone resulted in progressively worsening metabolic impairments. Before death, potato cyst nematodes displayed reduced motility, loss of cell viability markers, increased lipid content, and tissue degeneration. It was observed that nematodes treated with fluensulfone and stained with thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide exhibited a color transition from the head to the posterior, possibly indicating a shift in metabolic activity or alterations in the metabolic processes in the tail. The impaired lipid storage observed in potato cyst nematodes may be due to interference with the β-oxidation of fatty acids. Thus, fluensulfone mode of action in plant-parasitic nematodes likely involves disrupting their lipid storage capabilities [81].

Moreover, Hada et al. discovered that treated with fluensulfone led to a significant downregulation of all nematode neuropeptide-acting genes at various time-concentration combinations [82]. Genes related to acetylcholine (ace-1 and ace-2), FMRFamide-like peptides (flp-12, flp-14, flp-16, flp-18), and neuropeptide-like proteins (nlp-3 and nlp-12), all crucial to neuropeptide action, were inhibited. Concurrently, most genes associated with chemosensation, esophageal gland secretion, parasitism, fatty acid metabolism, and G protein-coupled receptors were also downregulated. Wram et al. also reported that fluensulfone had the most considerable impact on the expression of the 12 enzymes in the citric acid cycle [83]. It is confirmed that fluensulfone broadly affects various metabolic and physiological pathways in nematodes.

3.5.2. Tioxazafen

Tioxazafen, marketed under the trade name NemaStrike, is a disubstituted oxadiazole nematicide developed by Monsanto Company. Initially designed for medicinal purposes, these oxadiazole compounds were later adapted by Bayer for use as nematicides. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approved the registration of tioxazafen in 2017. This approval enabled its application on three major crops—corn, soybeans, and cotton. Tioxazafen mode of action is distinct from that of traditional nematicides. It functions by disrupting the activity of nematode ribosomes, which leads to gene mutations in the target nematodes, thereby exerting its nematicidal effects [84,85]. This product is a broad-spectrum, systemic nematicide that is applied as a seed treatment. It is not a fumigant and has been shown to effectively control a variety of nematodes, including soybean cyst nematodes, root-knot nematodes, reniform nematodes, and corn root rot nematodes [86,87]. The suspension concentrate of tioxazafen has low water solubility, which allows it to remain active in plant roots for an extended period—up to 75 days—potentially controlling up to two generations of nematodes. Furthermore, tioxazafen exhibits low toxicity, minimal environmental impact, and high safety for soil organisms.

3.5.3. Fluazaindolizine

Fluazaindolizine is an innovative sulfonamide non-fumigant nematicide developed by DuPont in 2015. This compound offers a broad spectrum control of plant parasitic nematodes and has applications across a wide range of crops, including fruits, vegetables, root and tuber crops, etc. Experimental studies have confirmed fluazaindolizine is efficacious against various plant-parasitic nematodes, such as root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.), reniform nematodes (Rotylenchulus spp.), dagger nematodes (Xiphinema spp.), and root-lesion nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.) [88,89]. It can be applied by multiple methods, including drip irrigation, spraying, or direct soil incorporation. Fluazaindolizine acts by paralyzing or stunning nematodes, leading to their death. While its actual mode of action remains unclear, studies have shown that it does not affect traditional nematicide targets like acetylcholinesterase, mitochondrial electron transport nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, or glutamate-gated chloride channels, even at concentrations up to 30 μM. Its absence of activity against these established targets and its relative safety for non-target nematodes suggest that fluazaindolizine has a novel mode of action. Registrations have been completed in Australia, Canada, and the United States, with plans to expand into markets such as China, Japan, and the European Union.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Research on plant-parasitic nematodes has a long history, yet progress in this field has lagged behind other plant pathology disciplines. This disparity is largely attributable to the unique biology of nematodes—their minute size, specialized morphology, resilient cuticle, and poorly characterized respiratory system—which collectively constrain experimental accessibility and mechanistic investigation. Consequently, the identification of novel nematicidal targets and the development of innovative chemistries have advanced at a comparatively modest pace. Meanwhile, globally tightened pesticide regulations and growing demands for ecological sustainability have accelerated the phase-out of traditional neurotoxic nematicides such as organophosphates, carbamates, and avermectin derivatives. Although historically effective, these compounds pose substantial non-target hazards, environmental risks, and regulatory burdens. In contrast, succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor (SDHI)-based nematicides have emerged as a pivotal direction in next-generation product development. Their non-neurotoxic modes of action, high target specificity, and favorable systemic mobility enable the establishment of stable rhizosphere activity gradients and enhance the precision of nematode suppression. Their comparatively low acute mammalian toxicity and the evolutionary divergence of SDH across biological groups further reduce ecological disturbance, aligning SDHIs with contemporary demands for safer, more sustainable pest management solutions.

Nonetheless, reliance on a limited number of target-site classes remains a concern. Resistance to classical AChE inhibitors and GluCl modulators is well documented across multiple pest taxa, and although the SDH complex exhibits constrained mutational flexibility, SDHI-resistant variants have already emerged in plant pathogenic fungi. These observations underscore the need for vigilant monitoring of potential resistance pathways in plant-parasitic nematodes and for incorporating SDHIs within robust resistance-management frameworks, including mode-of-action rotation and combination strategies.

Advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and in silico molecular design provide unprecedented opportunities to overcome long-standing barriers in nematicide discovery. Expanding genomic resources now facilitate systematic mining of nematode-specific metabolic pathways, receptors, and enzymes, while high-throughput screening paired with structure-based modeling may accelerate compound optimization and enhance selectivity. These interdisciplinary approaches also offer a rational basis for elucidating the modes of action of recently introduced nematicides—such as trifluenfuronate, cyclobutrifluram, fluazaindolizine, and various fluorine-containing scaffolds—many of which disrupt lipid metabolism, mitochondrial respiration, or other essential energetic processes, highlighting metabolic and respiratory pathways as critical vulnerabilities in nematodes.

Looking ahead, a system-level perspective is essential for guiding future innovation. The development, deployment, and regulation of nematicides inherently involve multiple stakeholder groups whose priorities are interdependent. Agronomists require reliable field efficacy across diverse environments, economic feasibility, and compatibility with integrated pest management (IPM) practices. Chemists and R&D scientists emphasize target selectivity, mechanistic clarity, and strategies to mitigate resistance evolution. Ecologists focus on minimizing non-target toxicity, preserving soil biodiversity, and mitigating long-term risks such as environmental persistence and bioaccumulation. Regulatory agencies prioritize human and environmental safety while imposing strict data requirements—factors that shape industrial investment and influence which chemistries ultimately reach the market. These dimensions interact dynamically: ecological risks influence regulatory decisions; regulatory constraints determine commercial feasibility; and agronomic realities dictate adoption and long-term effectiveness.

Within this broader systems framework, naturally occurring nematicidal substances warrant explicit consideration. Increasing evidence demonstrates that plant secondary metabolites, microbial toxins, volatile organic compounds, and enzyme-based agents possess potent nematicidal activity, rapid environmental degradation, and multi-target modes of action that may reduce resistance risk. Although these substances do not conform to the conventional definition of synthetic pesticides, their ecological safety profile and compatibility with sustainable agricultural systems suggest that they may constitute an emerging class of “natural nematicides.” The development of regulatory pathways tailored for low-risk or biological products could further facilitate their commercialization. From an agronomic perspective, such natural compounds may complement or partially replace synthetic chemistries, particularly in systems prioritizing soil health, reduced chemical inputs, and long-term resilience.

Taken together, these considerations highlight the need to move beyond molecule-centered discovery toward a coordinated, system-oriented strategy for nematode management. Future innovation will depend on integrating advances in molecular target discovery, ecological risk assessment, formulation science, field agronomy, and regulatory adaptation. Respiration-targeting nematicides such as SDHIs exemplify ongoing paradigm shifts, yet their long-term success requires responsible stewardship and diversification. The convergence of omics technologies, computational design, natural product chemistry, and sustainable agricultural practices is expected to accelerate the development of safer, more selective, and more resilient nematicide solutions. Sustained global collaboration will be essential to translate scientific advances into effective, field-ready tools that safeguard crop productivity while protecting environmental integrity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y.; methodology, D.Y.; software, D.Y.; validation, Q.W.; formal analysis, D.Y.; investigation, R.G.; resources, Q.W.; data curation, D.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y.; writing—review and editing, R.G., J.H. and A.C.; visualization, D.Y.; supervision, Q.W.; project administration, Q.W.; funding acquisition, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472615, 32172462) and the China Scholarship Council (202103250040).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable. This is a review article, and no new data were created or analyzed during the writing of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The financial support mentioned in the Funding part is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Blaxter, M.L. Nematoda: Genes, genomes and the evolution of parasitism. Adv. Parasitol. 2003, 54, 101–195. [Google Scholar]

- Abad, P.; Gouzy, J.; Aury, J.-M.; Castagnone-Sereno, P.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Deleury, E.; Perfus-Barbeoch, L.; Anthouard, V.; Artiguenave, F.; Blok, V.C.; et al. Genome sequence of the metazoan plant-parasitic nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, B.; Singh, A.P. Nematodes: A Threat to Sustainability of Agriculture. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 29, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.T.; Haegeman, A.; Danchin, E.G.J.; Gaur, H.S.; Helder, J.; Jones, M.G.K.; Kikuchi, T.; Manzanilla-López, R.; Palomares-Rius, J.E.; Wesemael, W.M.L.; et al. Top 10 plant-parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2013, 14, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Gheysen, G.; Fenoll, C. Genomics and Molecular Genetics of Plant-Nematode Interactions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C.H. Fumigation in the 21st century. Crop Prot. 2000, 19, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, J.; Turner, S.; Coyne, D.L.; Nijs, L.d.; Hockland, S.; Maafi, Z.T. Current nematode threats to world agriculture. In Genomics and Molecular Genetics of Plant-Nematode Interactions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, P.S.; Ehlers, R.-U.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I. Nematodes as Biocontrol Agents; CABI: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ciancio, A.; Mukerji, K.G. Integrated Management and Biocontrol of Vegetable and Grain Crops Nematodes; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, C.M.G.D.; Monteiro, A.R.; Blok, V.C. Morphological and molecular diagnostics for plant-parasitic nematodes: Working together to get the identification done. Tropical Plant Pathology 2011, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, J.; Starr, J.L. Plant Nematodes of Agricultural Importance: A Color Handbook; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Wu, D.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Fu, Z.Q. Bioactivated and selective: A promising new family of nematicides with a novel mode of action. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1106–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umetsu, N.; Shirai, Y. Development of novel pesticides in the 21st century. J. Pestic. Sci. 2020, 45, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahm, G.P.; Desaeger, J.; Smith, B.K.; Pahutski, T.F.; Rivera, M.A.; Meloro, T.; Kucharczyk, R.; Lett, R.M.; Daly, A.; Smith, B.T. The discovery of fluazaindolizine: A new product for the control of plant parasitic nematodes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Cai, S.; Deng, Y.; Cao, S.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, H. Efficacy of cyclobutrifluram in controlling Fusarium crown rot of wheat and resistance risk of three Fusarium species to cyclobutrifluram. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 198, 105723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.; Cho, B.-K. Microbial production of nematicidal agents for controlling plant-parasitic nematodes. Process Biochem. 2021, 108, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargmann, C.I. Neurobiology of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Science 1998, 282, 2028–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, M.C.; Williams, P.L.; Benedetto, A.; Au, C.; Helmcke, K.J.; Aschner, M.; Meyer, J.N. Caenorhabditis elegans: An emerging model in biomedical and environmental toxicology. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 106, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combes, D.; Fedon, Y.; Toutant, J.-P.; Arpagaus, M. Acetylcholinesterase genes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. In International Review of Cytology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 209, pp. 207–239. [Google Scholar]

- Piotte, C.; Arthaud, L.; Abad, P.; Rosso, M.-N. Molecular cloning of an acetylcholinesterase gene from the plant parasitic nematodes, Meloidogyne incognita and Meloidogyne javanica. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999, 99, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, E.; Vovlas, A.; D’Addabbo, T.; De Luca, F. Molecular mechanism of Cinnamomum zeylanicum and Citrus aurantium essential oils against the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; De-liang, P.; Bida, G.; Qi, H. Molecular cloning and characterization of a new acetylcholinesterase gene Dd-ace-1 from Ditylenchus destructor. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. 2010, 36, 437–441. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, W.; Fan, C.; Wu, Q.; Peng, D.; da Silva, W.; Sun, X. Expression and evolutionary analyses of three acetylcholinesterase genes (Mi-ace-1, Mi-ace-2, Mi-ace-3) in the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Exp. Parasitol. 2017, 176, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.C.; Lilley, C.J.; Atkinson, H.J.; Urwin, P.E. Functional characterisation of a cyst nematode acetylcholinesterase gene using Caenorhabditis elegans as a heterologous system. Int. J. Parasitol. 2009, 39, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Lee, D.-W.; Choi, J.Y.; Je, Y.H.; Koh, Y.H.; Lee, S.H. Three acetylcholinesterases of the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus: Insights into distinct physiological functions. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2011, 175, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Lee, D.-W.; Koh, Y.H.; Lee, S.H. A Soluble Acetylcholinesterase Provides Chemical Defense against Xenobiotics in the Pinewood Nematode. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, D.H.; Cha, D.J.; Kim, J.H. Mutation and duplication of arthropod acetylcholinesterase: Implications for pesticide resistance and tolerance. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 120, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, C.H.; Chang, S. Nematode acetylcholinesterases: Molecular forms and their potential role in nematode behavior. Parasitol. Today 1992, 8, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, M.A. RNA Interference as a Tool to Control Plant Parasitic Nematode Infestation in Key Plant Crops. Ph.D. Thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pree, D.J.; Townshend, J.L.; Cole, K.J. Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterases from Aphelenchus avenae by Carbofuran and Fenamiphos. J. Nematol. 1990, 22, 182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Le Patourel, G.N.J.; Wright, D.J. Some factors affecting the susceptibility of two nematode species to phorate. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1976, 6, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, T.A. Inhibitory glutamate receptor channels. Mol. Neurobiol. 1996, 13, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, D.M.; Portillo, V.; Wolstenholme, A.J. The avermectin receptors of Haemonchus contortus and Caenorhabditis elegans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2003, 33, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoop, W.L.; Mrozik, H.; Fisher, M.H. Structure and activity of avermectins and milbemycins in animal health. Vet. Parasitol. 1995, 59, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, A.; Ōmura, S. Ivermectin, ‘wonder drug’ from Japan: The human use perspective. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2011, 87, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, D.F.; Vassilatis, D.K.; Liu, K.K.; Paress, P.S.; Van der Ploeg, L.H.T.; Schaeffer, J.M.; Arena, J.P. Cloning of an avermectin-sensitive glutamate-gated chloride channel from Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1994, 371, 707–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, J.A.; Smith, M.M.; Vassilatis, D.K.; Avery, L. The genetics of ivermectin resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2674–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.P.; Hayashi, J.; Beech, R.N.; Prichard, R.K. Study of the nematode putative GABA type-A receptor subunits: Evidence for modulation by ivermectin. J. Neurochem. 2002, 83, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolstenholme, A.J.; Rogers, A.T. Glutamate-gated chloride channels and the mode of action of the avermectin/milbemycin anthelmintics. Parasitology 2005, 131, S85–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laughton, D.L.; Lunt, G.G.; Wolstenholme, A.J. Reporter gene constructs suggest that the Caenorhabditis elegans avermectin receptor beta-subunit is expressed solely in the pharynx. J. Exp. Biol. 1997, 200, 1509–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashov, F.A.; Koonin, E.V.; Morgunov, I.G.; Finogenova, T.V.; Kondrashova, M.N. Evolution of glyoxylate cycle enzymes in Metazoa: Evidence of multiple horizontal transfer events and pseudogene formation. Biol. Direct 2006, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloukas, T.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Biological activity of the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fluopyram against Botrytis cinerea and fungal baseline sensitivity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, E.; Jordan, D.; Gorny, A.; Dunne, J.; Lux, L.; Shew, B.; Ye, W. Previous Cropping Sequence Affects Plant-Parasitic Nematodes and Yield of Peanut and Cotton More than Continuous Use of Fluopyram. Crops 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faske, T.R.; Hurd, K. Sensitivity of Meloidogyne incognita and Rotylenchulus reniformis to Fluopyram. J. Nematol. 2015, 47, 316–321. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, Y.; Saroya, Y. Effect of fluensulfone and fluopyram on the mobility and infection of second-stage juveniles of Meloidogyne incognita and. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Ji, X.; Qiao, K. Oxidative stress, intestinal damage, and cell apoptosis: Toxicity induced by fluopyram in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, H.; Wang, Q. Fluorine-containing agrochemicals in the last decade and approaches for fluorine incorporation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, F.; Rodriguez-Crespo, D.; Wicky, C. The New Nematicide Cyclobutrifluram Targets the Mitochondrial Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shao, H.; Qi, D.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, L.; Guo, K. The New Nematicide Cyclobutrifluram Targets the Mitochondrial Succinate Dehydrogenase Complex in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lümmen, P.; Khajehali, J.; Luther, K.; Van Leeuwen, T. The cyclic keto-enol insecticide spirotetramat inhibits insect and spider mite acetyl-CoA carboxylases by interfering with the carboxyltransferase partial reaction. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vang, L.E.; Opperman, C.H.; Schwarz, M.R.; Davis, E.L. Spirotetramat causes an arrest of nematode juvenile development. Nematology 2016, 18, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahs, H.Z.; Refai, F.S.; Gopinadhan, S.; Moussa, Y.; Gan, H.H.; Hunashal, Y. A new class of natural anthelmintics targeting lipid metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, M.; Kriek, N.; Flemming, A.J. Studies of an insecticidal inhibitor of acetyl-CoA carboxylase in the nematode C. elegans. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 169, 104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Siddique, S. Parasitic nematodes: Dietary habits and their implications. Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Chitin synthesis and degradation as targets for pesticide action. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1993, 22, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spindler, K.D.; Spindler-Barth, M.; Londershausen, M. Chitin metabolism: A target for drugs against parasites. Parasitol. Res. 1990, 76, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Peng, D. Nematode chitin and application. In Targeting Chitin-Containing Organisms; Yang, Q., Fukamizo, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, E.; Di Vito, M.; Jones, J.T.; De Giorgi, C. Analysis of chitin synthase function in a plant parasitic nematode, Meloidogyne artiellia, using RNAi. Gene 2005, 349, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, C.H.; Bird, D.M.; Williamson, V.M.; Rokhsar, D.S.; Burke, M.; Cohn, J.; Windham, E. Sequence and genetic map of Meloidogyne hapla: A compact nematode genome for plant parasitism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14802–14807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Z.; Yang, J.; Tao, N.; Liang, L.; Mi, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Cloning of the gene Lecanicillium psalliotae chitinase Lpchi1 and identification of its potential role in the biocontrol of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tachu, B.; Pillai, S.; Lucius, R.; Pogonka, T. Essential role of chitinase in the development of the filarial nematode Acanthocheilonema viteae. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, I.; Kohara, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Sugimoto, A. Large-scale analysis of gene function in Caenorhabditis elegans by high-throughput RNAi. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, Y.; Wang, X.; Guan, T.; Peng, D.; Li, H. Versatile glycoside hydrolase family 18 chitinases for fungi ingestion and reproduction in the pinewood nematode Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiewnick, S.; Sikora, R.A. Biological control of the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita by Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251. Biol. Control 2006, 38, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelarends, G.J.; Wilkens, M.; Larkin, M.J.; Elsas, J.D.v.; Janssen, D.B. Degradation of 1,3-Dichloropropene by Pseudomonas cichorii 170. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2931–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, N.R. The mode of action of fumigants. J. Stored Prod. Res. 1985, 21, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-M.; Preston, J.F., III; Wei, C.-I. Antibacterial mechanism of allyl isothiocyanate. J. Food Prot. 2000, 63, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, F.B.; Holley, R.A. Enzymatic inhibition by allyl isothiocyanate and factors affecting its antimicrobial action against Escherichia coli O157: H7. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, P.G.; Slatter, J.G.; Rashed, M.S.; Han, D.H.; Baillie, T.A. Carbamoylation of peptides and proteins in vitro by S-(N-methylcarbamoyl)glutathione and S-(N-methylcarbamoyl)cysteine, two electrophilic S-linked conjugates of methyl isocyanate. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1991, 4, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X. Comparative studies on mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes of Sitophilus zeamais treated with Allyl isothiocyanate and Calcium phosphide. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 126, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wu, H. Transcriptomic alterations in Sitophilus zeamais in response to allyl isothiocyanate fumigation. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 137, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, N.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, C. Function of four mitochondrial genes in fumigation lethal mechanisms of Allyl Isothiocyanate against Sitophilus zeamais adults. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 179, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, A.; Guo, M.; Yan, D.; Mao, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Duan, X.; Wang, P. Evaluation of sulfuryl fluoride as a soil fumigant in China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 70, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifácio, L.F.; Sousa, E.; Naves, P.; Inácio, M.L.; Henriques, J.; Mota, M.; Barbosa, P.; Drinkall, M.J.; Buckley, S. Efficacy of sulfuryl fluoride against the pinewood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Nematoda: Aphelenchidae), in Pinus pinaster boards. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meikle, R.W.; Stewart, D.; Globus, O.A. Fumigant Mode of Action, Drywood Termite Metabolism of Vikane Fumigant as Shown by Labeled Pool Technique. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1963, 11, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Cao, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Canbin, O.; Guo, M.; Guo, X. Dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) as an effective soil fumigant against nematodes in China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Tenorio, M.A.; Tello, J.C.; Zanón, M.J.; de Cara, M. Soil disinfestation with dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) to control Meloidogyne and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici in a tomato greenhouse. Crop Prot. 2018, 112, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugravot, S.; Grolleau, F.; Macherel, D.; Rochetaing, A.; Hue, B.; Stankiewicz, M.; Huignard, J.; Lapied, B. Dimethyl Disulfide Exerts Insecticidal Neurotoxicity Through Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Activation of Insect KATP Channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 90, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Fang, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, A.; Wang, Q.; Yan, D. Transcriptome reveals the toxicity difference of dimethyl disulfide by contact and fumigation on Meloidogyne incognita through calcium channel-mediated oxidative phosphorylation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 460, 132268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearn, J.; Ludlow, E.; Dillon, J.; O’Connor, V.; Holden-Dye, L. Fluensulfone is a nematicide with a mode of action distinct from anticholinesterases and macrocyclic lactones. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 109, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearn, J.; Lilley, C.; Urwin, P.; O’Connor, V.; Holden-Dye, L. Progressive metabolic impairment underlies the novel nematicidal action of fluensulfone on the potato cyst nematode Globodera pallida. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 142, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, A.; Singh, D.; Venkata Satyanarayana, K.K.V.; Chatterjee, M.; Phani, V.; Rao, U. Effect of fluensulfone on different functional genes of root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita. J. Nematol. 2021, 53, e2021-73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wram, C.L.; Hesse, C.N.; Zasada, I.A. Transcriptional changes of biochemical pathways in Meloidogyne incognita in response to non-fumigant nematicides. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeschke, P. Progress of modern agricultural chemistry and future prospects. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, Q.X.; Song, B. Chemical Nematicides: Recent Research Progress and Outlook. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 12175–12188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomczynska, U.; South, M.S.; Bunkers, G.J.; Edgecomb, D.; Wyse-Pester, D.; Selness, S.; Ding, Y.; Christiansen, J.; Ediger, K.; Miller, W.; et al. Tioxazafen: A New Broad-Spectrum Seed Treatment Nematicide. In Discovery and Synthesis of Crop Protection Products; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Volume 1204, pp. 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Faske, T.R.; Brown, K.; Kelly, J. Toxicity of Tioxazafen to Meloidogyne Incognita and Rotylenchulus Reniformis. J. Nematol. 2022, 54, 20220007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzortzakakis, E.A.; Thoden, T.C.; Chatzaki, A. Investigation of fluazaindolizine as a potential novel tool to manage Xiphinema index. Crop Prot. 2024, 180, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of fluazaindolizine, a new nematicide for management of Meloidogyne incognita in squash in calcareous soils. Crop Prot. 2021, 143, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.