Abstract

Morocco ranked 9th in the 2024 Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI), placing it among the world’s top 10 performers in climate action. Building on this leadership, our review outlines practical and real-world steps to strengthen Morocco’s agricultural efforts to curb greenhouse gases. We base our analysis on a comparison of national communications, updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and findings from peer-reviewed research. We identified four main areas where Morocco can boost its impact: advanced livestock methane reduction, systematic soil carbon monitoring, precision nitrogen management, and integrated renewable energy systems. To inform these levers, we studied best practices from other six high-performing countries in the 2024 CCPI—Denmark, Sweden, India, Estonia, the Netherlands, and the Philippines—and considered how their strategies could be adapted to Morocco’s semi-arid, smallholder-dominated farming context. This study delivers four concrete, multi-phase implementation roadmaps spanning 2025–2035. These roadmaps outline the technical steps, regulatory changes, and financial mechanisms. They also specified emissions reduction targets associated with each pillar: 15–30% for livestock methane, 0.3–0.8 tons of carbon per hectare per year for soil carbon sequestration, 18% for precision nitrogen management, and fossil fuel displacement through five renewable energy initiatives. The roadmaps are designed to inform the next update of Morocco’s Generation Green strategy and support the country’s 2030 NDC goal of a 45.5% emission reduction.

1. Introduction

Global agriculture faces a dual imperative: limiting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and ensuring food security. This challenge is intensified in semi-arid regions, where water scarcity exacerbates the production risks. Agriculture accounts for approximately 18% of global GHG emissions [1,2]. These emissions primarily stem from enteric fermentation in livestock and synthetic fertilizers. Semi-arid agroecosystems cover 40% of the global land. In these regions, intensified practices and soil degradation are driving the transition from carbon sinks to net emission sources [3].

Morocco exemplifies this trend. Agriculture employs 67% of the rural workforce and contributes 16% to the GDP [4,5]. However, this sector faces increasing fragility. Since the 1960s, precipitation has declined by 16%, whereas temperatures have increased by 1.1 °C [6].

A diagnostic based on Morocco’s Fourth National Communication (2021) [4] and Third Biennial Update Report (2022) [7] identified four dominant emission sources: enteric fermentation from livestock, which accounts for 39.6% of sectoral emissions. Soil N2O emissions from synthetic fertilizers constitute over 90% of total soil emissions. Land-use degradation reduces carbon sinks, whereas irrigation and mechanization contribute 13% of emissions.

Based on this diagnosis, this study identifies four key innovation pillars for mitigation: (1) advanced livestock methane mitigation, (2) systematic soil carbon monitoring, (3) precision nitrogen management, and (4) integrated renewable energy systems. To identify best practices for these pillars, the analysis focused on high-performing nations in the 2024 Climate Change Performance Index (CCPI). The key benchmarks include Denmark, Sweden, India, Estonia, the Netherlands, and the Philippines.

These nations provide distinct blueprints for each of the pillars. For livestock methane (Pillar 1), Denmark and Sweden demonstrate how policy-driven feed additives and biogas integration can reduce emissions [8]. For soil carbon (Pillar 2), the Netherlands’ monitoring networks achieved sequestration rates of 0.3–0.8 t C ha−1 yr−1 [9]. For precision nitrogen (Pillar 3), India’s conservation agriculture programs offer a scalable model for semi-arid systems. Similarly, the Philippines’ organic fertilization programs have reduced fertilizer dependency by up to 19% using biochar-compost blends that help lower N2O emissions [10,11]. For renewable energy (Pillar 4), Estonia’s supply chain optimization provides models that are adaptable to different scales [12]. Similarly, the Philippines demonstrates how decentralized renewable microgrids can support irrigation and processing in rural farming communities [13].

These international successes offer promising blueprints; however, transferability remains a central challenge. Many of these mitigation technologies were designed for temperate and capital-intensive farming systems. They are not immediately adapted to the semi-arid conditions of Morocco. The Moroccan agricultural sector is dominated by smallholder farms, typically operating on 1.5–2.5 hectares and facing limited access to capital. Therefore, there is a need for a systematic evaluation of international strategies that are technically feasible, economically viable, and socially acceptable in the Moroccan context [14].

This review addresses this challenge by evaluating the transferability of these international strategies to Morocco. As a primary contribution, it develops four detailed implementation roadmaps (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4). These frameworks specify technical requirements, regulatory reforms, and financing mechanisms and are designed to serve as strategic inputs for future revisions of the Generation Green strategy. Furthermore, they offer actionable pathways to support Morocco’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target of reducing emissions by 45.5% by 2030 [15]. By strengthening agricultural mitigation and renewable energy integration, these roadmaps can help sustain and potentially improve Morocco’s future performance in the Climate Change Performance Index. Crucially, the proposed innovations are designed to benefit the country’s 1.5 million smallholder producers [5].

2. Review Methodology

This study employed a narrative, comparative review of agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) mitigation strategies to assess their transferability to Morocco’s semiarid, smallholder-dominated agricultural context. We first evaluated Morocco’s current mitigation measures and identified four key innovation pillars: (1) advanced livestock methane mitigation, (2) systematic soil carbon monitoring, (3) precision nitrogen management, and (4) integrated renewable energy systems. We then analyzed the best practices of the top 2024 CCPI performers—Denmark, Sweden, Estonia, the Netherlands, India, and the Philippines—to identify transferable strategies. A formal PRISMA protocol was not applied because the evidence base consists primarily of national policy documents, UNFCCC submissions, and strategic planning texts, which are not amenable to conventional trial-oriented systematic review procedures.

2.1. Country Selection and Analytical Framework

The review focused on seven countries: Morocco (the study focus) and six benchmark countries from the top tier of the 2024 CCPI ranking. Benchmark countries were selected to combine strong climate performance with heterogeneous agroecological and institutional contexts. This selection enabled the examination of mitigation options applicable to semi-arid and mixed farming conditions. The comparative analysis was structured around four pre-defined innovation pillars identified in the diagnostic phase.

2.2. Evidence Collection and Sources

Evidence was collected in two tiers to ensure comprehensiveness and relevance of the data. Tier 1 comprises official policy documents submitted to the UNFCCC: Morocco’s Updated NDC, Fourth National Communication, and Third Biennial Update Report, as well as equivalent submissions from the six benchmark countries. National agricultural strategies—including Morocco’s Generation Green 2020–2030—were included when they specified explicit mitigation measures with quantified GHG impacts. Tier 2 comprises peer-reviewed literature indexed in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar. Literature was identified through keyword combinations including “enteric methane mitigation”, “soil carbon monitoring network”, “precision nitrogen management”, “agrivoltaics”, “biogas from manure”, “semiarid agriculture”, and country names.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Documents and articles were eligible if they met three conditions: (i) publication or submission between 2008 and 2024, aligning with Morocco’s Green Morocco Plan and Generation Green period; (ii) explicit focus on agricultural or land-based-mitigation measures; and (iii) provision of quantitative GHG outcomes (for example, change in CH4, N2O, or CO2-eq) or clearly documented implementation mechanisms relevant to one of the four innovation pillars. Sources were excluded if they exclusively addressed non-agricultural sectors, provided only generic climate targets without operational details, or lacked sufficient methodological documentation. Only documents in English or French were retained.

2.4. Data Extraction and Comparative Analysis

For all eligible sources, information was extracted into a standardized matrix that captured the country, document type, innovation pillar, farming system, intervention description, quantitative mitigation effect, enabling policy instruments (e.g., subsidies, regulation, carbon payments), and implementation scale. Within each pillar, the measures were first synthesized at the country level. The measures were then compared across countries to identify recurrent intervention types (e.g., feed additives, manure biogas systems, soil carbon observatories, nutrient advisory schemes, agrivoltaics, and decentralized microgrids) and their associated GHG reduction or sequestration performance ranges. This synthesis informed the identification of “best practice bundles” for each pillar, combining technological innovations with supportive governance and financing mechanisms.

2.5. Transferability Assessment

Operationalization of Transferability Assessment: For each best practice bundle, evidence from UNFCCC communications and peer-reviewed sources was systematically evaluated against the five criteria using qualitative scoring. Measures that scored favorably on at least three of the five criteria—particularly technical feasibility, financial accessibility, and social acceptability—were identified as candidates for roadmap integration. Unfavorable scores for institutional compatibility or monitoring requirements were addressed through design modifications (e.g., capacity-building provisions in roadmap phases) rather than outright rejection. This inclusive approach recognizes that institutional barriers are implementation challenges, not fundamental constraints on transferability. The final selection of measures for Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 implementation roadmaps required demonstrated alignment with Morocco’s NDC commitments and Generation Green strategic objectives, ensuring that all roadmap components directly support the Kingdom’s 2030 climate targets. The Table A5 explains the implementation coordination matrix. Evidence from Moroccan national reports and strategies was used to establish the sectoral emission baseline and current mitigation portfolio, providing a reference against which international practices were evaluated. Measures scoring favorably across these five criteria were integrated into pillar-specific implementation roadmaps spanning: 2025–2035 for Table A1, Table A2 and Table A4 and 2030–2035 for Table A3. These roadmaps outline the sequential technical, regulatory, and financial steps for adapting each pillar and serve as strategic inputs for revising Morocco’s Generation Green strategy.

2.6. Study Limitations

The review is selective rather than exhaustive, focusing on a subset of high-performing 2024 CCPI countries and four predefined innovation pillars. Differences in national inventory methods, reporting depth, and mitigation program maturity may affect the strict comparability of the quantitative outcomes across countries. Language restrictions and the uneven availability of subnational data may have led to the underrepresentation of relevant experiences, particularly in lower-income countries. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

3. Analysis of the Agricultural Mitigation Landscape: Current State and International Innovations

3.1. Greenhouse Gas Profile and Mitigation Pathways for Morocco’s Agricultural Sector

Morocco’s Third Biennial Update Report (2022) [7] and Fourth National Communication (2021) [4] document that the agricultural sector is a critical decarbonization frontier. It contributed 22.8% of the national GHG emissions, approximately 20,729.3 Gg CO2eq in 2018, ranking second only to the energy sector. NonCO2 gases dominated the sectoral emission profile. Agricultural soils constituted the most significant emission source, accounting for 52.5% of the sectoral emissions. They drive N2O emissions through synthetic fertilizer application and soil management practices, accounting for 92.4% of the country’s total anthropogenic N2O emissions. Livestock activities constitute the second primary source, with enteric fermentation (39.6%) and manure management (7.7%) accounting for 62.4% of the national methane (CH4) emissions. Taken together, soil and livestock account for approximately 99.7% of Morocco’s agricultural GHG footprint.

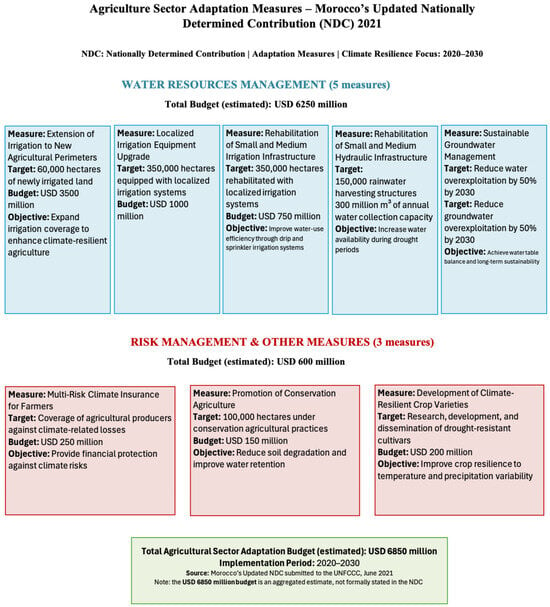

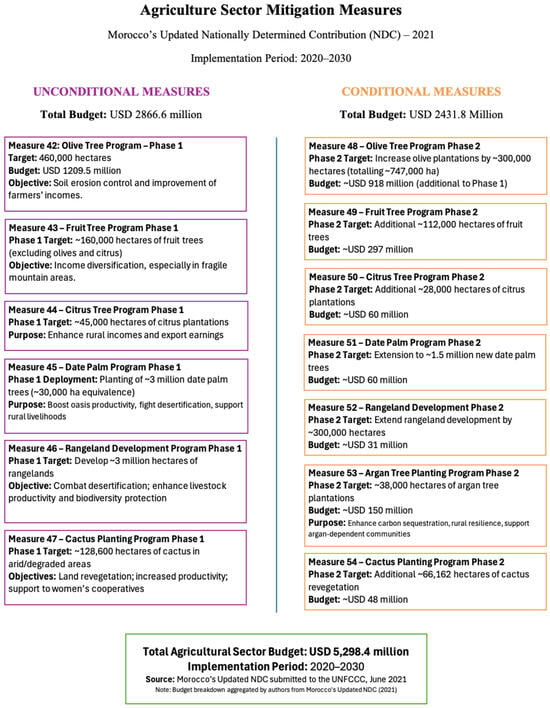

Morocco’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC 2021) [15] outlines a comprehensive framework for addressing these emission hotspots through complementary adaptation and mitigation strategies. Eight adaptation measures prioritize the resilience of water resources. Water resource management comprises five measures with an estimated cost of 6.25 billion USD, and risk management consists of three measures with an estimated cost of 600 million USD, totaling 6.85 billion USD for 2020–2030. Figure 1 and Figure 2 summarize the adaptation and mitigation measures for the agricultural sector in the Updated NDC.

Figure 1.

Agriculture sector adaptation measures outlined in Morocco’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC 2021) [15]. Source: Morocco’s Updated NDC, 2021 [15].

Figure 2.

Agriculture sector mitigation measures outlined in Morocco’s Updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC 2021) [15]. Source: Morocco’s Updated NDC, 2021 [15].

We contend that three strategic mitigation pillars warrant prioritizing implementation to address Morocco’s agricultural emission hotspots. (1) Advanced Livestock Methane Mitigation implements targeted feed and manure management protocols to reduce enteric fermentation emissions. (2) Systematic Soil Carbon Monitoring establishes a transparent and verifiable measurement infrastructure for carbon sequestration validation across Morocco’s agricultural soils. (3) Precision Nitrogen Management optimizes synthetic fertilizer application through spatial targeting methodologies to reduce N2O emissions from soil management.

3.2. Assessment of Morocco’s Climate Performance

Morocco’s 9th position in the 2024 Climate Change Performance Index reflects its strong performance in the GHG Emissions and Energy Use categories, validating its Nationally Determined Contribution and modest per capita emissions profile relative to industrialized economies [16]. However, two critical gaps limit the progress. Renewable energy penetration remains at approximately 12% of the primary energy supply against a 52% target for 2030. This 40-percentage point deficit undermines assessments of Morocco’s alignment with the Paris Agreement trajectory [4,16].

Within the 2020–2030 Generation Green strategy horizon, energy inputs to agriculture account for approximately 13% of sectoral emissions. These emissions arise predominantly from fossil fuels, notably butane and diesel, which are used in irrigation and field operations [4]. Morocco’s 2020–2030 Generation Green [17] includes an expanded solar pumping commitment; however, reliance on fossil fuels persists at scale.

We contend that advancing renewable energy integration, particularly within agricultural systems, represents a strategic mitigation pillar opportunity to address both the national-level renewable energy gap and the sector’s significant fossil-fuel footprint. Implementing decentralized renewable technologies in farming communities—agrivoltaics, biogas recovery, and solar-powered irrigation networks—would simultaneously strengthen Morocco’s renewable energy profile for future CCPI assessments and achieve measurable emission reductions within the agricultural sector.

3.3. International Agricultural Mitigation Innovations

The comparative analysis of agricultural mitigation strategies from leading 2024 CCPI nations reveals distinct implementation pathways across the four innovation pillars. Denmark, Sweden, Estonia, the Netherlands, India, and the Philippines demonstrate specialized expertise in livestock methane reduction, soil carbon monitoring, precision nitrogen management, and renewable energy integration, offering insights for adaptation to Morocco’s semiarid context.

3.3.1. Pillar 1: Advanced Livestock Methane Mitigation

Leading 2024 CCPI nations have achieved significant enteric methane reductions through integrated policies and technologies [16].

Estonia demonstrates the strongest grassland-based performance: selective breeding combined with grassland management reduces methane emissions by 15–20% through improved feed conversion efficiency [12,18]—a low-capital approach aligned with Morocco’s smallholder systems.

Sweden implements circular biogas-digestate systems: digestate utilization replaces approximately 38 kg/ha of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers annually while capturing methane from manure, a strategy supported under the Rural Development Program since 2015 [8,19].

Netherlands achieved an 8.7% dairy herd reduction by 2020 via market-based schemes: voluntary participation was compensated through carbon farming payment mechanisms, as documented in its Eighth National Communication (2023) [9,20].

Sweden’s digestate model and Estonia’s breeding strategies offer immediately transferable pathways for smallholder manure management in Morocco.

3.3.2. Pillar 2: Systematic Soil Carbon Monitoring

Robust monitoring networks verify sequestration outcomes and support NDC carbon targets [4].

Netherlands achieves the highest performance: the National Soil Program monitors 300 sites via the Biological Indicators of Soil Quality (BISQ) protocol, integrating microbial analysis with machine learning-based mapping to achieve 0.3–0.8 t C ha−1 yr−1 sequestration, as documented in its Eighth National Communication (2023) [21,22,23,24].

India demonstrates semi-arid transferability: conservation agriculture programs achieve 19% emissions reduction through zero-tillage practices while sequestering 1.2 t C ha−1 yr−1—outcomes directly applicable to Morocco’s NDC direct seeding target [11,25].

Estonia integrates grassland and agroforestry: rotational grazing achieves 0.8 t C ha−1 yr−1 sequestration, complemented by hedgerow systems realizing 4.2 t C km−1 yr−1 [12,18].

Adopting the Dutch BISQ framework combined with India’s zero-tillage approach—both verified in official national communications—provides Morocco with the monitoring infrastructure to validate carbon sequestration targets.

3.3.3. Pillar 3: Precision Nitrogen Management

Integrating regulatory incentives with technical innovations reduces both emissions and input costs [7,26].

India achieves the strongest smallholder results: the Site-Specific Nutrient Management (SSNM) policy implemented since 2015 reduced synthetic fertilizer use by 18% through Soil Health Cards, documented in India’s Third National Communication (2022) [7]—a low-tech tool ideal for 1.5–2.5 ha farms and directly addressing Morocco’s information gaps [27].

Denmark demonstrates regulatory effectiveness: fertilizer taxation policies (1990–2015) drove a 20% N2O reduction through sustained economic incentives, as documented in Denmark’s Eighth National Communication and Fifth Biennial Report (2023) [28,29].

Sweden achieves productivity-preserving results: precision cereal management using variable-rate technology reduced emissions by 12% while maintaining yields, supported by nutrient advisory services prioritizing GHG emissions reduction since 2001 [19,30].

Philippines implements organic alternatives: biochar-compost blends reduce N2O emissions by 10–30% in rice while increasing yields by 12%, as documented in the Philippines’ Second National Communication (2022) [31].

India’s Soil Health Card model offers the most immediate transferability, whereas Denmark’s regulatory framework provides a policy blueprint endorsed by official national communications.

3.3.4. Pillar 4: Integrated Renewable Energy Systems

Renewable integration addresses agricultural decarbonization and rural energy access, simultaneously supporting climate targets and livelihood security.

Estonia achieves the highest energy efficiency: digitalized supply chain optimization reduces fuel usage by 15–20% via route optimization algorithms, integrated with EU Horizon Europe funding and public–private partnerships [12,18].

Netherlands demonstrates solar potential: agrivoltaic systems optimize land use by combining solar generation with crop production, advancing beyond Morocco’s irrigation-focused renewable applications [20,32].

Philippines addresses rural energy access: decentralized renewable microgrids support irrigation and processing in farming communities, as documented in the Philippines’ Second National Communication (2022) [13,31].

Sweden exemplifies circular principles: agricultural byproduct conversion to bioenergy, with biogas production scaling under the Rural Development Program since 2015, which demonstrates models suitable for Morocco’s biomass resources [8,19].

Implementing decentralized renewable systems aligned with the Philippines model, combined with Estonia’s logistics optimization and Sweden’s biogas integration—all documented in verified national communications—can significantly reduce Morocco’s fossil fuel dependence for irrigation while advancing Generation Green 2020–2030 objectives.

4. Discussion

This review identifies four innovative pillars for agricultural GHG mitigation in Morocco. The transferability assessment evaluates how international best practices from high-performing 2024 CCPI nations can be adapted to Morocco’s institutional, economic, and agroecological constraints. This section synthesizes evidence across the four mitigation pillars, examining technical feasibility, financial accessibility, social acceptability, institutional compatibility, and monitoring requirements for each intervention. The analysis prioritizes low-capital, smallholder-appropriate technologies while identifying regulatory reforms and financing mechanisms necessary for successful implementation.

The primary contribution is four detailed, multi-phase implementation roadmaps spanning 2025–2035 (Table A1, Table A2 and Table A4) and the Sustainable Nitrogen Management Program (Table A3) with 2030–2035 timeline. As presented in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4, these frameworks translate international experiences into phased, institutionally grounded systems. They are tailored to Morocco’s legal, economic, and agroecological settings [15].

The following subsections examine the transferability of the best practices for each pillar. Subsequent analyses address how the corresponding roadmaps operationalize these practices in Morocco. The final subsection synthesizes the synergies, trade-offs, and risks across all four roadmaps.

4.1. Transferability of Advanced Livestock Methane Mitigation and Roadmap (Table A1)

Leading 2024 CCPI countries employ three complementary strategies: feed additives (Denmark), biogas-digestate systems (Sweden), and selective breeding (Estonia). These low-capital approaches align well with Morocco’s smallholder systems.

4.1.1. Morocco’s Livestock Context and Constraints

Morocco’s livestock sector differs markedly from these international models. Herds are predominantly smallholder-based, averaging 2–5 cattle per farm [33]. Law No. 28-07 on Animal Health and Veterinary Inspection prohibits methane-reducing feed additives. This law is administered by the National Office of Food Safety (ONSSA) in Morocco [34].

Removing this constraint requires legal amendments to align with EU additive registration protocols. ONSSA’s regulatory oversight must be adapted accordingly [35]. Financial access is severely constrained. Only 6% of Moroccan farmers have access to formal credit [5]. This limits the investment capacity for new feeds or biogas infrastructure without dedicated financing instruments.

However, Morocco’s Generation Green strategy allocates 5.3 billion USD to agricultural mitigation projects. This provides a potential funding envelope for livestock interventions [17].

4.1.2. Implementation Roadmap Structure

Table A1 structures the livestock methane roadmap into four phases spanning 2025–2035.

- Phase 1 prioritizes technical feasibility: 3-NOP trials on local breeds and baseline emissions quantification.

- Phase 2 develops regulatory frameworks by amending Law No. 28-07 and aligning with EU protocols under the ONSSA administration.

- Phase 3 implements pilots through “Climate Bonus” per-liter milk payments, “Climate Milk” labeling, Crédit Agricole loans at 2% interest, and tiered subsidies.

- Phase 4 consolidates monitoring for 50,000 farmers and 500,000 cattle, targeting a 15–30% sectoral methane reduction.

This design reflects the Danish and Swedish experiences. However, Morocco-specific risks require attention. Regulatory changes may take 18–24 months [35].

Smallholders could face exclusion if credit and subsidy schemes are not tailored to low-collateral producers [5]. Traditional livestock keepers may resist new additives without clear evidence of productivity and animal health co-benefits [33].

Table A1 partially addresses these risks through multi-actor engagement and phased pilot studies. To strengthen resilience, the roadmap should clarify the pathways for contingency planning. These include scaling Sweden-like manure-to-biogas systems and Estonia-style pasture improvements. Such alternatives to high-cost additive deployment reduce regulatory and financial dependencies [12].

4.1.3. Risk Assessment for Table A1

The livestock methane roadmap faces four critical implementation barriers.

- First, regulatory uncertainty poses temporal risk. Law No. 28-07 amendments require 18–24 months of parliamentary approval [35]. This timeline may delay the Phase 2 activities and disrupt the financing schedules.

- Second, financial access constraints threaten equity. Only 6% of Moroccan farmers have access to formal credit [5]. Without tailored low-collateral financing through Crédit Agricole du Maroc, the benefits may be concentrated among larger producers. This undermines the smallholder-focused objectives of Generation Green [17].

- Third, social acceptance barriers represent the risks of implementation. Traditional livestock keepers may resist using novel feed additives. A transparent demonstration of productivity gains and animal welfare co-benefits is essential [33].

- Fourth, technical performance uncertainty remains. 3-NOP trials on local Moroccan cattle breeds may yield lower methane reductions than the 27% observed in Danish Holstein cattle [16]. Adaptive management protocols are required during Phase 1.

To address these risks, the roadmap should integrate contingency pathways that emphasize low-capital alternatives. Sweden’s manure-to-biogas systems and Estonia’s pasture improvement strategies deliver comparable methane reductions. These approaches avoid regulatory dependencies and high financial thresholds [8].

4.1.4. Integration Note on Gender and Traditional Farming

Although the manuscript does not explicitly incorporate gender-disaggregated data, livestock management in Morocco is significantly influenced by gender roles. Traditionally, women manage small ruminants and poultry in many contexts. The roadmap’s emphasis on 2–5 cattle farms with limited access to credit disproportionately affects female-headed households. Future implementation should track the distribution of benefits by gender to ensure equitable co-benefits. Similarly, traditional pastoral communities employ management practices that may either support or conflict with new interventions. Engagement strategies must consider pastoral knowledge systems alongside technology adoption.

4.2. Transferability of Systematic Soil Carbon Monitoring and Roadmap (Table A2)

Robust monitoring networks verify soil carbon sequestration outcomes and support NDC commitments [4].

4.2.1. International Models and Performance Metrics

The Dutch BISQ protocol, India’s zero-tillage programs, and Estonia’s grassland-agroforestry integration provide validated models. Morocco’s monitoring capacity requires substantial infrastructure investment.

4.2.2. Morocco’s Monitoring Capacity Gaps

Morocco currently lacks a comparable national soil-monitoring network. Soil degradation is severe, with erosion exceeding 50 t ha−1 yr−1 in vulnerable areas [36]. Only three laboratories are equipped for advanced soil carbon analysis [37].

Salinity and alkalinity affect approximately 1.6 million hectares of irrigated land. The soil pH often exceeds 8.0 [38]. Despite these constraints, Morocco’s Updated NDC and Generation Green commit to transitioning one million hectares to direct seeding. This transition is supported by 2.9 billion USD domestic and 2.5 billion USD international funding [21].

4.2.3. Implementation Framework: Programme National de Protection des Sols (PNPS)

Table A2 adapts the BISQ into a six-phase PNPS roadmap spanning 2025–2035.

- Phase 1 develops technical infrastructure, including laboratory upgrades, near-infrared spectroscopy, CaCl2 extraction transfer, national soil GIS, and training for scientists and technicians.

- Phase 2 establishes the regulatory and policy framework. Actions include alignment with EU soil protection, stakeholder consultations, and funding mechanisms under Generation Green and the NDC.

- Phase 3 implements pilots involving approximately 500 farmers and cooperatives. Public–private partnerships and carbon credit mechanism testing are central components.

- Phase 4 integrates systems with a full BISQ rollout, real-time satellite and in situ data collection, 200 monitoring technicians and 500 farmer data collectors.

- Phase 5 addresses evaluation and knowledge transfer through the use of international advisory panels. This includes scientific publications, regional training centers, and South-South cooperation [39].

- Phase 6 operationalizes national scaling and carbon finance integration (2034–2035), sustaining monitoring across 12 agroecological zones with 200 technicians, integrating satellite monitoring for soil carbon validation, and leveraging carbon credit revenues for long-term sustainability.

This roadmap is technically consistent with the Dutch and Indian experiences. This aligns with Morocco’s NDC commitments [9,11]. However, the upfront investment is substantial. Human capacity building presents significant challenges [5].

Coordination among research institutes, ministries, and extension services may be complicated by administrative silos [40].

4.2.4. Equity Considerations in Program Design

Equity risk exists if monitoring focuses exclusively on better-resourced regions. Smallholders in degraded areas may not benefit from carbon financing [14]. The PNPS should be presented as a core adaptation-mitigation infrastructure. Priority sampling and support in smallholder-dominated zones address equity and resilience concerns [41].

4.2.5. Risk Assessment for Table A2

The PNPS roadmap faces four interconnected challenges.

- First, institutional capacity deficits pose critical risks. Currently, Morocco operates only three laboratories equipped for advanced soil carbon analysis [37]. Phase 1 investments of $15.6 million and training programs for 50 soil scientists and 15 technicians represent substantial capacity expansion. Recruitment and retention challenges are expected in a context where the extension agent-to-farmer ratio is constrained to 1:1250 [5].

- Second, inter-institutional coordination barriers threaten the coherence of implementation. The PNPS requires seamless collaboration among INRA Morocco, the Ministry of Agriculture, regional extension services, and international partners [42]. Administrative silos documented in Morocco’s Fourth National Communication may fragment data flows and delay decision making [40].

- Third, geographic equity risks emerge in pilot implementation: concentrating Phase 3 monitoring in better-resourced regions with existing agricultural infrastructure would exclude smallholders in erosion-prone, degraded zones. These are precisely the areas that deliver the highest adaptation-mitigation co-benefits [36].

- Fourth, financial sustainability uncertainty persists beyond 2035. The PNPS operational model requires ongoing funding for 200 monitoring technicians, 500 farmer data collectors, and satellite data subscriptions (Table A2, Phase 4). These costs must be integrated into Morocco’s long-term budgets. Alternatively, they must be linked to carbon credit revenues to ensure programmatic continuity [14].

To address these risks, the roadmap should prioritize capacity development in under-resourced areas. Establishing inter-ministerial coordination protocols through the mechanisms listed in Table A5 is essential. Phase 3 pilots should explicitly target smallholder-dominated high-degradation zones. This validates the carbon finance mechanisms that sustain post-2035 operations [41,43].

4.2.6. Integration Note on Gender and Traditional Farming

Soil monitoring frameworks implicitly benefit women farmers who manage smallholder plots. However, the manuscript does not include a gender-disaggregated analysis of soil health monitoring adoption or carbon sequestration outcomes by gender. Traditional farming knowledge, particularly women’s agricultural practices and crop and soil management techniques, are not systematically documented in the referenced sources. Future research should explicitly examine whether soil health cards and monitoring systems are accessible to women and traditional farming communities. This ensures that the benefits accrue equitably across demographic groups.

4.3. Transferability of Precision Nitrogen Management and Roadmap (Table A3)

As established in Section 3.3.3, regulatory and technical integration offers dual benefits for emissions reduction and cost management.

4.3.1. International Evidence: Diverse Regulatory and Technical Approaches

International evidence demonstrates that India’s Soil Health Card model and Denmark’s regulatory framework provide immediately transferable blueprints for Morocco.

4.3.2. Morocco’s Baseline and Constraints

In Morocco, agricultural soils account for 52.5% of sectoral emissions and contribute more than 90% of anthropogenic N2O emissions [7]. Current practices are dominated by conventional fertilizer applications with limited precision tools.

Legal frameworks lack fertilizer taxation or mandatory fertilizer plans [35]. Rural broadband covers only 35% of the agricultural areas. The extension agent-to-farmer ratio remains at 1:1250 [40].

4.3.3. Sustainable Nitrogen Management Program (SNMP) Structure

Table A3 presents the SNMP roadmap spanning 2030–2035 in four phases.

- Phase 1: Foundation Building (2030) includes amending Law 53-18 [44], drafting fertilizer taxation legislation, mapping Nitrate Vulnerable Zones, designing Soil Health Card tools, and planning IoT networks.

- Phase 2: Pilot Testing (2031–2032) implements regional regulations, fertilizer tax trials, deployment of handheld optical sensors (e.g., GreenSeeker) and chlorophyll meters (e.g., SPAD), and organic fertilizer promotion.

- Phase 3: National Rollout (2033–2034) establishes nationwide fertilizer taxation, mandatory plans, nitrogen ceilings, and SSNM scaling, targeting 18% N2O reduction.

- Phase 4: Optimization (2035+) focuses on adaptive regulation, innovation platforms, research and development, and regional knowledge-sharing. This phase aims for 90% farmer participation [10,18]).

This roadmap combines Denmark’s regulatory rigor, India’s diagnostic tools, and Sweden’s precision technology. It operates within the constraints of Morocco. Several risks remain unresolved: Fertilizer taxation may face resistance from smallholders unless revenues are recycled into extension services or through targeted subsidies. Digital tools risk excluding low-connectivity regions. Extension service workloads may constrain enforcement and training [5].

The SNMP should be framed as a structural reform requiring redistributive mechanisms and inclusive digital strategies. SMS-based tools and cooperative intermediaries offer low-technology alternatives. Phased enforcement must align with institutional capacities [27,30].

4.3.4. Risk Assessment for Table A3

The SNMP roadmap confronts five critical implementation risks that require proactive design adjustments.

- First, political economy barriers pose significant risks to implementation. Smallholder resistance documented in similar contexts may derail fertilizer taxation in Phase 3. Unless tax revenues are transparently redistributed into extension services, Soil Health Card programs, or direct subsidies, implementation will fail. Denmark’s successful taxation model demonstrates this redistributive necessity [28].

- Second, the risk of digital exclusion threatens equity. Precision nitrogen tools (GreenSeeker sensors, SPAD meters, IoT networks) require rural broadband coverage, which is currently available in only 35% of Morocco’s agricultural areas [40]. Without inclusive digital strategies, such as SMS-based decision support tools or cooperative-level intermediaries, the roadmap may exacerbate the documented digital divide [45].

- Third, extension service capacity constraints are a critical bottleneck. Morocco’s 1:1250 agent-to-farmer ratio is far below the levels needed for individualized Soil Health Card training and national fertilizer plan enforcement [5]. This capacity gap risks undermining the 90% farmer participation target without substantial investment in extension infrastructure.

- Fourth, regulatory delays may disrupt the roadmap timeline. The Law 53-18 [44] amendments and fertilizer taxation legislation require parliamentary approval, which historically extends 18–24 months [35]. This may compress Phase 2 pilot testing and jeopardize the 2030–2035 implementation timeline.

- Fifth, monitoring and enforcement challenges persist in the industry. Nitrogen ceiling enforcement and mandatory fertilizer plan compliance require robust systems that current institutions may struggle to operationalize. This is particularly acute in remote smallholder regions [14].

To mitigate these risks, the SNMP should integrate revenue-recycling provisions into the Phase 1 legal drafts. Phase 2 pilots should prioritize low-tech digital alternatives, including SMS advisories and radio extensions. Coordination with the PNPS (Table A2) leverages soil monitoring infrastructure. Enforcement mechanisms should be phased sequentially by region, matching the documented extension capacity expansion in Table A5 [27,30].

4.3.5. Integration Note on Political Economy and Gender

The manuscript briefly acknowledges the risk of smallholder resistance but does not systematically analyze political and economic barriers beyond financial constraints. Nitrogen taxation creates winners and losers—large commercial operations may absorb costs, while smallholders bear disproportionate burdens without subsidy design. The reference to “redistributive mechanisms” is appropriate but underspecified in terms of gender implications. Women farmers, who disproportionately operate smallholder plots without formal property rights, may be excluded from subsidy programs unless explicitly designed. Rural broadband “exclusion” also disproportionately affects women and the youth. The manuscript implicitly acknowledges these issues but could strengthen its analysis by explicitly naming the gender and intergenerational dimensions in future revisions.

4.4. Transferability of Integrated Renewable Energy Systems and Roadmap (Table A4)

4.4.1. International Models: Diverse Technology and Policy Approaches

Estonia’s digital optimization, the Netherlands’ agrivoltaics, the Philippines’ microgrids, and Sweden’s biogas systems provide complementary renewable pathways. Morocco’s context requires hybrid approaches.

4.4.2. Morocco’s Renewable Energy Gap and Agricultural Energy Demands

In Morocco, agricultural energy use contributes 13% of the agricultural emissions. This is driven by the use of butane and diesel in irrigation and mechanization [4]. The share of renewable energy remains at 12%, far below the 2030 target of 52% [16].

Generation Green primarily focuses on solar pumping. Agrivoltaics, biogas, and smart energy management remain under-integrated [17,46].

4.4.3. Renewable Energy Implementation Framework

Table A4 translates the international models into five renewable energy initiatives.

- Agrivoltaics: 50 pilots (2025–2027) scaling to 10,000 installations (2034–2035)

- Agricultural biogas: Pilot plants in Gharb and Casablanca scaling to 1000 installations

- Wind-powered irrigation: 20 remote-area pilots scaling to national integration

- Solar cold storage: 30 pilots expanding to national network

- Smart energy management: 100 pilot sites to national digital platform

These measures can reduce fossil fuel dependence and close part of the national renewable energy gap. They strengthen water scarcity resilience [16].

4.4.4. Risks and Barriers

Land-use trade-offs from agrivoltaics may marginalize smallholders if investments are concentrated on larger farms [32]. Biogas and smart systems require regulatory clarity on feed-in tariffs and data governance [4].

Off-grid communities benefit the most from microgrids and wind-powered irrigation. Equitable access depends on financing to ensure smallholder participation [5,13].

4.4.5. Risk Assessment for Table A4

The renewable energy roadmap faces five distinct challenges.

- First, land-use equity risks emerge from agrivoltaic deployment. Capital-intensive photovoltaic installations (estimated $25 M national + $60 M private investment) may concentrate adoption among larger commercial farms. This replicates the inequities observed in other capital-intensive agricultural technologies [5,32]. Without tiered subsidies or cooperative ownership models, Phase 1 pilots risk validating systems that are inaccessible to target beneficiaries.

- Second, regulatory uncertainty constrains biogas and smart-energy initiatives. Morocco currently lacks clear feed-in tariff structures for biogas-to-grid integration (BGI). Data governance protocols for smart energy platforms are absent [40]. These regulatory gaps must be resolved with energy sector authorities to enable Phase 2 scaling (2028–2030).

- Third, financing access barriers threaten off-grid renewable energy deployment. Wind-powered irrigation and solar cold storage in remote areas require equitable access. Current financing (documented in Table A4) may not reach smallholders without dedicated last-mile financial intermediaries [5,13].

- Fourth, technical performance risks persist owing to climate differences. Morocco’s semi-arid agroclimatic conditions differ substantially from the Netherlands’ temperate zones, where agrivoltaic systems were validated [32]. Phase 1 pilots must rigorously assess the effects of crop-panel shading on water-use efficiency and yield stability. This avoids technological maladaptation under Moroccan conditions [46].

- Fifth, grid integration challenges constrain biogas and agrivoltaic scaling capabilities. Morocco’s current electricity grid infrastructure may require upgrades to accommodate decentralized renewable generation [4]. This coordination challenge requires inter-ministerial alignment between agricultural and energy authorities through the mechanisms listed in Table A5.

To mitigate these risks, Table A4 should integrate cooperative ownership provisions for agrivoltaics in Phase 1. The development of a regulatory framework for biogas feed-in tariffs requires coordination with energy ministries during Phases 1–2. Dedicated financing vehicles for off-grid communities should leverage GCF adaptation funding. Rigorous semi-arid technology validation in Phase 1 pilots is essential. Grid integration coordination protocols through Table A5 inter-ministerial mechanisms address systemic risks [8,39].

4.4.6. Integration Note on Equity and Access

While emphasizing smallholder access, the renewable energy framework does not explicitly address gender dimensions or traditional energy use patterns. Women’s limited control over productive assets, including land, constrains their participation in renewable energy systems, particularly capital-intensive technologies such as agrivoltaics. Traditional cooking practices using biomass represent both a climate concern and a source of income and energy security for rural women. The roadmap should explicitly assess whether renewable energy investments complement or compete with existing livelihood strategies, particularly for women’s subsistence and income generation.

4.5. Cross-Cutting Synergies, Trade-Offs, and Implementation Coordination (Table A5)

4.5.1. Interconnected Benefits Across Pillars

The four roadmaps are mutually reinforcing through explicit synergy.

Improved manure management and biogas under Pillar 1 supports Pillar 4’s renewable energy objectives. Biogas systems simultaneously generate digestate by substituting synthetic nitrogen for Pillar 3 [10].

The PNPS (Pillar 2) provides the measurement backbone for the SNMP (Pillar 3). This enables targeted fertilizer regulations and potential carbon and nitrogen credits [24].

Decentralized renewables (Pillar 4) can power digital tools for precision agriculture in off-grid areas [40].

Across all pillars, soil carbon enhancement, reduced fertilizer imports, and reliable renewable irrigation deliver adaptation-mitigation co-benefits. These strengthen resilience to drought and market volatility [6].

4.5.2. Systemic Risks and Implementation Constraints

Systemic risks must be acknowledged, along with synergies.

The implementation of four complex programs concurrently may exceed the institutional capacity. The 1:1250 agent-to-farmer ratio exemplifies structural constraints [5].

Large capital allocations to infrastructure may crowd out funding for social support mechanisms [17]. Without deliberate design, new technologies and policies may exacerbate equity gaps [14].

New monitoring systems raise data governance risks concerning data quality, ownership, and privacy [40].

4.5.3. Implementation Coordination Framework: Table A5

Table A5 (Implementation Coordination Matrix) operationalizes these synergies and addresses systemic risks through three, cross-cutting mechanisms.

- First, inter-ministerial coordination (alignment of agriculture, energy, and interior, 2025–2027) is required to harmonize regulatory reforms across Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 and prevent policy fragmentation. Livestock feed additive regulations (Table A1), soil protection frameworks (Table A2), fertilizer taxation (Table A3), and renewable energy feed-in tariffs (Table A4) advance coherently under the unified Generation Green oversight [4]. This coordination directly addresses the administrative silos documented by Adeli et al. (2024) [40]. These silos fragment climate policy implementation.

- Second, international partnerships (2025–2027) leverage technical cooperation. BISQ partners include the Wageningen University in the Netherlands. SSNM expertise comes from the Soil Health Card program in India. Renewable energy innovators include Sweden’s biogas networks and the Philippines’ microgrids. These collaborations accelerate knowledge transfer and reduce Morocco’s learning curve [17,19]. These partnerships facilitate access to multilateral financing (GCF (Green Climate Fund), GEF (Global Environment Facility), and the World Bank). Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 aggregate an estimated $200+ million in external support for the roadmap implementation [5].

- Third, the monitoring and evaluation frameworks (2025–2030) integrate GHG measurement protocols. Baseline establishment, performance indicator definition, and data collection systems will begin in 2025–2027. Progress tracking, impact assessment, and adaptive management will continue through 2028–2030. These enable unified Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) systems supporting Morocco’s NDC reporting and unlocking carbon finance mechanisms [15].

4.5.4. Phased Implementation and Capacity Management

Table A5 presents the phased implementation of strategies to mitigate institutional capacity risks.

By sequencing roadmap deployment—livestock methane and renewable energy pilots (2025–2027, Table A1 and Table A4) precede soil carbon infrastructure (2025–2031, Table A2) and nitrogen taxation rollout (2030–2035, Table A3)—the coordination matrix prevents simultaneous demands on extension services. This protects the 1:1250 agent-to-farmer ratio and administrative resources [5]

This phased approach allows Phases 1 and 2 in Table A1 and Table A4 to generate early demonstration effects. Farmer engagement occurs before more complex monitoring (Table A2) and regulatory (Table A3) interventions on a national scale.

The 2031–2033 integration optimization phase will focus on maximizing synergy and enhancing efficiency. Digestate from biogas systems (Pillar 1) substitutes nitrogen fertilizers tracked by the PNPS (Pillar 2) and SNMP (Pillar 3). Decentralized renewables (Pillar 4) power precision agriculture sensors in off-grid zones [40].

By 2034–2035, Table A5 transitions to the finalization of the national model, international leadership, and knowledge transfer. Morocco is positioned to disseminate validated roadmaps through South-South cooperation. This benefits semi-arid, smallholder-dominated agricultural systems across Africa and the Global South [43].

4.5.5. Risk Assessment for Table A5: Meta-Level Implementation Challenges

The coordination matrix itself faces three meta-level implementation risks.

- First, inter-ministerial coordination failures remain possible despite formal alignment structures (2025–2027). Moroccan ministries have historically operated with distinct budgetary cycles, procurement procedures, and political priorities [4]. These differences may fragment the unified implementation. This risk requires a high-level political commitment. A dedicated Prime Ministerial coordination unit anchored in Generation Green governance provides the necessary institutional support.

- Second, international partnerships introduce vulnerabilities. Roadmap timelines rely on sustained technical cooperation and financial flows from the Netherlands (BISQ), India (SSNM), Sweden (biogas), and multilateral funds (GCF, GEF, and the World Bank) (Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4). Disruptions from shifting donor priorities or geopolitical factors can delay capacity building and technology transfer. Contingency partnerships with additional high CCPI performers or regional institutions provide mitigation pathways.

- Third, the complexity of monitoring and evaluation systems poses challenges for data governance. Integrating MRV protocols across the four pillars requires harmonizing disparate data streams (livestock emissions, soil carbon stocks, nitrogen balances, and energy consumption) managed by different institutions (ONSSA, INRA Morocco, and the Ministry of Energy). This technical and institutional challenge risks the production of fragmented and incompatible datasets. Unless Table A5 monitoring frameworks mandate standardized protocols, unified data platforms, and clear institutional data-sharing agreements from the 2025 baseline establishment, implementation will fail [40].

To mitigate these risks, Table A5 establishes a high-level inter-ministerial steering committee with Prime Ministerial oversight. International partnerships should diversify beyond current CCPI high performers to include regional institutions (such as the African Union and the Economic Community of West African States). Unified digital data platforms with standardized MRV protocols must be co-designed by all implementing institutions during the 2025–2027 baseline phase.

4.5.6. Integration Note on Gender, Traditional Farming, and Political Economy

While Table A5 emphasizes coordination mechanisms, this manuscript does not explicitly address how inter-ministerial processes affect gender equity outcomes or accommodate traditional farming knowledge. Women’s participation in coordination committees and benefit-sharing arrangements is not specified. Similarly, traditional farming communities’ engagement in monitoring and evaluation frameworks is not systematically planned. A political economy analysis of which stakeholders gain and lose coordination mechanisms would strengthen this section. The roadmap should explicitly acknowledge these tensions and design deliberate mechanisms to ensure that the coordination benefits are equitably distributed.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This review has several limitations.

Quantitative evidence is robust for some measures, including the Danish taxation, Dutch BISQ, and Indian SSNM. However, evidence is sparser for other Moroccan contexts, such as agrivoltaics and 3-NOP efficacy in local breeds [11].

Gender-disaggregated data were mainly absent from the reviewed sources. This constrains the design of gender-responsive roadmaps [14]. The role of traditional farming has not been systematically documented despite its acknowledgment [39,41].

The timelines and budgets in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 are informed estimates that require validation through pilot projects with rigorous monitoring protocols [47].

Future research should prioritize empirical validation across Morocco’s agroecological zones. Socio-economic assessments examining distributional effects by gender and social group are essential [14]. Institutional and political economy analyses can identify feasible reform sequences [35].

As implementation progresses, Morocco’s experience can inform the South-South knowledge exchange. Other semi-arid, smallholder-dominated countries across the Global South can benefit from documented lessons [43]. Explicitly integrating gender analysis and documenting traditional farming knowledge will strengthen future iterations of the roadmaps.

5. Conclusions

This review synthesizes comparative evidence from six top-performing nations in the 2024 Climate Change Performance Index to evaluate the transferability of agricultural GHG mitigation strategies to Morocco’s semi-arid, smallholder-dominated systems. We identified four innovation pillars essential for Morocco’s agricultural decarbonization: advanced livestock methane mitigation, systematic soil carbon monitoring, precision nitrogen management, and integrated renewable energy systems. These pillars directly address Morocco’s agricultural emission profile, dominated by soil N2O emissions (52.5% of sectoral emissions), livestock enteric fermentation (39.6%), and energy use in irrigation (13%) [4,7].

The principal contribution is four detailed implementation roadmaps (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4) with a cross-cutting coordination framework (Table A5). These roadmaps address livestock methane through feed additives and selective breeding (targeting 15–30% reduction), establish soil carbon monitoring via the PNPS framework adapted from the Netherlands’ BISQ protocol (0.3–0.8 t C ha−1 yr−1), implement precision nitrogen management combining Denmark’s taxation model with India’s Soil Health Cards (targeting 18% N2O reduction), and integrate five renewable energy initiatives to reduce fossil fuel dependence [8,24,27]. The roadmaps are tailored to Morocco’s 1.5 million smallholder producers (average farm size 1.5–2.5 ha, with only 6% accessing formal credit), addressing four critical barriers: legislative amendments to permit methane-reducing additives, investment in soil monitoring infrastructure, fertilizer taxation policy reform, and grid-connection protocols for renewable energy [4,5].

Substantial uncertainties persist regarding technology performance under Morocco’s agroecological conditions. Three-nitrooxypropanol efficacy derives from temperate Holstein trials achieving 27% methane reductions; efficacy in smallholder herds remains unvalidated. Agrivoltaic systems are demonstrated in temperate zones; performance under semi-arid water scarcity and alkaline soils (pH > 8.0) is unquantified. Soil carbon sequestration rates depend on heterogeneous conditions potentially limiting temperate benchmarks [32,38].

Critical implementation barriers include regulatory delays (18–24 months), financial access constraints affecting 94% of smallholders, extension capacity gaps (1:1250 agent-to-farmer ratio), digital infrastructure limitations, and inter-ministerial coordination challenges [4,35,40]. Phase 1 pilots (2025–2027) must rigorously validate all four pillars’ performance under authentic Moroccan conditions before scaling.

To maximize roadmap impact, we recommend three strategic priorities. First, establish pilots across representative agroecological zones to generate empirical validation data on GHG reductions and performance under semi-arid conditions, explicitly testing 3-NOP efficacy in local breeds, agrivoltaic shading effects, and soil carbon sequestration in degraded soils [46,47]. Second, conduct institutional capacity assessments to identify phased reform sequences, particularly addressing extension service expansion, laboratory development (currently three facilities), and inter-ministerial coordination mechanisms [4,5,37]. Third, develop gender-disaggregated impact assessments to ensure equitable implementation, addressing smallholder exclusion from credit schemes, geographic disparities in monitoring coverage, and digital tool accessibility [5,14].

Morocco’s Generation Green strategy allocates $5.3 billion to agricultural mitigation, providing substantial implementation funding [17]. By combining international best practices with context-specific adaptation and proactive risk mitigation, Morocco can achieve measurable GHG reductions while strengthening resilience and productivity. Success positions the Kingdom as a regional leader in agricultural climate action, providing lessons for South-South knowledge exchange with other semi-arid, smallholder regions across Africa and the Global South, supporting Morocco’s 2030 emission-reduction targets and contributing to global agricultural transformation pathways that reconcile climate mitigation with food security in water-scarce environments [41,43].

Author Contributions

A.H.: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. M.N.: conceptualization, validation, methodology, formal analysis, supervision, writing—review and editing. M.C.: conceptualization, validation, methodology, supervision, writing, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No financial support or funding was received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the Hassan II Institute of Agronomy and Veterinary Medicine and the Hassan II Academy of Science and Technology for their support in this research (GISEC project).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this study.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

| 3-NOP | 3-Nitrooxypropanol |

| BISQ | Biological Indicators of Soil Quality |

| CCPI | Climate Change Performance Index |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CO2-eq | Carbon Dioxide Equivalent |

| COP | Conference of the Parties |

| EBI | Evidence-Based Intervention |

| EBIs | Evidence-Based Interventions |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FSSC | Food Safety System Certification |

| GCF | Green Climate Fund |

| GEF | Global Environment Facility |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| Gg | Gigagram (unit of mass; 1 Gg = 1000 tons) |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| INRA | Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (Morocco) |

| MRV | Measurement, Reporting, and Verification |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| ONSSA | Office National de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits Alimentaires |

| PNPS | Programme National de Protection des Sols (National Soil Protection Program) |

| RIVM | Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, Netherlands) |

| SNMP | Sustainable Nitrogen Management Program |

| SSNM | Site-Specific Nutrient Management |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| USD | United States Dollar |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Advanced Livestock Methane Mitigation Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

Table A1.

Advanced Livestock Methane Mitigation Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

| Phase | Duration | Key Activities | Institutional Partnerships | Financial Mechanisms | Expected Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Technical Feasibility and Regulatory Preparation | 2025–2027 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 2: Regulatory Framework Development | 2027–2029 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 3: Pilot Implementation and Scale-Up | 2029–2032 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 4: Monitoring and Expansion | 2032–2035 |

|

|

|

|

Table A2.

National Soil Program (PNPS) Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

Table A2.

National Soil Program (PNPS) Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

| Phase | Duration | Core Objectives | Technology Transfer Components | Capacity Building Requirements | Investment Needs (USD Million) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Technical Infrastructure Development | 2025–2027 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 2: Regulatory and Policy Framework | 2027–2028 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 3: Pilot Implementation | 2028–2030 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 4: System Integration and Monitoring | 2030–2032 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 5: Evaluation and Knowledge Transfer | 2032–2034 |

|

|

|

|

| Phase 6: National Scaling and Carbon Finance Integration | 2034–2035 |

|

|

|

|

Table A3.

Sustainable Nitrogen Management Program (SNMP) Implementation Framework for Morocco (2030–2035).

Table A3.

Sustainable Nitrogen Management Program (SNMP) Implementation Framework for Morocco (2030–2035).

| Implementation Phase | Timeline | Regulatory Actions | Technology Deployment | Stakeholder Engagement | Performance Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Foundation Building | Year 1 (2030) |

|

|

|

|

| Phase II: Pilot Testing and Refinement | Years 2–3 (2031–2032) |

|

|

|

|

| Phase III: National Rollout | Years 4–5 (2033–2034) |

|

|

|

|

| Phase IV: Optimization and Expansion | Year 6+ (2035 onwards) |

|

|

|

|

Table A4.

Integrated Renewable Energy Systems Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

Table A4.

Integrated Renewable Energy Systems Implementation Framework for Morocco (2025–2035).

| Technology Initiative | Phase 1 (2025–2027) | Phase 2 (2028–2030) | Phase 3 (2031–2033) | Phase 4 (2034–2035) | Feasibility Assessment | Financing Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrivoltaic Systems Integration |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Agricultural Biogas Development |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Wind-Powered Irrigation Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solar Cold Storage Networks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smart Energy Management Systems |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table A5.

Implementation Coordination Matrix.

Table A5.

Implementation Coordination Matrix.

| Cross-Cutting Elements | 2025–2027 | 2028–2030 | 2031–2033 | 2034–2035 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Ministerial Coordination |

|

|

|

|

| International Partnerships |

|

|

|

|

| Monitoring and Evaluation |

|

|

|

|

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Global GHG Emissions from Agrifood Systems; FAO Statistical Yearbook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Pan, G. Global greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture: Synthesis and projection. Global Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Ghimire, R.; Sainju, U.M.; Acosta-Martinez, V.; Sitaula, B. Net greenhouse gas balance with cover crops in semi-arid irrigated cropping systems. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Morocco. Fourth National Communication of Morocco to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UNFCCC: Rabat, Morocco, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Morocco Green Generation Program-for-Results Project; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/245801608346893390/pdf/Morocco-Green-Generation-Program-for-Results-Project.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Lkammarte, F.Z.; Eddoughri, F.; Karmaoui, A. Analysis of the vulnerability of agriculture to climate and anthropogenic change in Marrakech Safi region, Morocco. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2023, 21, 519–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morocco. Third Biennial Update Report of Morocco Under the UNFCCC (BUR3); Ministry of Energy Transition and Sustainable Development, Department of Sustainable Development: Rabat, Morocco, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hellsten, S.; Dalgaard, T.; Rankinen, K.; Tørseth, K.; Bakken, L.; Bechmann, M.; Kulmala, A.; Moldan, F.; Olofsson, S.; Piil, K.; et al. Abating N in Nordic agriculture-Policy, measures and way forward. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Tiktak, A.; Rougoor, C.W. Evaluation of the Dutch implementation of the nitrates directive, the water framework directive, and the national emission ceilings directive. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 78, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lin, F.; Wu, S.; Ji, C.; Sun, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Zou, J. A meta-analysis of fertilizer-induced soil NO and combined NO+N2O emissions. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 2520–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, T.B.; Aryal, J.P.; Khatri-Chhetri, A.; Shirsath, P.B.; Arumugam, P.; Stirling, C.M. Identifying high-yield low-emission pathways for cereal production in South Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2018, 23, 621–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariva, J.; Viira, A.H. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and LULUCF sectors in Estonia: Current situation and mitigation scenarios. Land Use Policy 2023, 125, 106481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, D.; Werner, C.; Janz, B.; Klatt, S.; Sander, B.O.; Wassmann, R.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Greenhouse gas mitigation potential of alternate wetting and drying for rice production at national scale—A modeling case study for the Philippines. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2022JG006848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hafdaoui, H.; El Alaoui, H.; Mahidat, S.; El Harmouzi, Z.; Khallaayoun, A. Long-term low-carbon strategy of Morocco: A review of future scenarios and energy measures. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Morocco. Morocco-Nationally Determined Contribution Under the Paris Agreement: Updated Submission; UNFCCC: Rabat, Morocco, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burck, J.; Uhlich, T.; Bals, C.; Höhne, N.; Nascimento, L.; Kumar, C.H.; Bosse, J.; Riebandt, M.; Pradipta, G. Climate Change Performance Index 2024: Results; Germanwatch e.V.: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Morocco. Generation Green Strategy 2020–2030; Ministry of Agriculture, Maritime Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests: Rabat, Morocco, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment Estonia. Estonia’s Eighth National Communication Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; UNFCCC: Tallinn, Estonia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sweden. Sweden’s Eighth National Communication on Climate Change Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Ministry of Climate and Enterprise: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023.

- Netherlands. Netherlands’ Eighth National Communication and Fifth Biennial Report Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2022.

- Helfenstein, A.; Mulder, V.L.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Okx, J.P. BIS-4D: Mapping soil properties and their uncertainties at 25 m resolution in the Netherlands. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 2941–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIVM. Soil Ecology: The Dutch Monitoring Programme; RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- RIVM. Soil Ecosystem Profiling in the Netherlands with Ten Years of Monitoring of the Biological Indicator for Soil Quality (BISQ); RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers, M.; Schouten, A.J.; Bloem, J.; Van Eekeren, N.; De Goede, R.G.M.; Jagersop Akkerhuis, G.A.J.M.; Van der Werf, A.; Wijnen, B.; Zondag, J.; Breure, A.M. Biological measurements in a nationwide soil monitoring network. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC). India: Third National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2023.

- Geng, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Hénault, C.; Revellin, C. Decreased nitrous oxide emissions associated with functional microbial genes under bio-organic fertilizer application in vegetable fields. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Chauhan, A.; Ladon, T. Site-specific nutrient management: A review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard, T.; Hansen, B.; Hasler, B.; Hertel, O.; Hutchings, N.J.; Jacobsen, B.H.; Jensen, L.S.; Kronvang, B.; Olesen, J.E.; Schjørring, J.K.; et al. Policies for agricultural nitrogen management—Trends, challenges and prospects for improved efficiency in Denmark. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denmark. Denmark’s Eighth National Communication and Fifth Biennial Report Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Danish Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, R.; Maire, J.; Florence, A.; Cowan, N.; Skiba, U.; van der Weerden, T.; Ju, X. Mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural soils by precision management. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippines. Philippines’ Second National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Climate Change Commission, Government of the Philippines: Manila, Philippines, 2014.

- AgroRES Project. Renewable Energy for Sustainable Agriculture; Interreg Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.interregeurope.eu/find-policy-solutions/stories/renewable-energy-sustainable-agriculture (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Morocco Agricultural Statistics and Profile; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Morocco. Law No. 28-07 on Animal Health and Veterinary Inspection; Official Bulletin: Rabat, Morocco, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdom of Morocco. Parliamentary Procedures Manual; Parliament of Morocco: Rabat, Morocco, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Salhi, A.; Benabdelouahab, T.; Martin-Vide, J.; Okacha, A.; El Hasnaoui, Y.; El Mousaoui, M.; El Morabit, A.; Himi, M.; Benabdelouahab, S.; Lebrini, Y.; et al. Bridging the perception gap is the only way to align soil protection actions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 718, 137421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA Morocco). Soil Analysis Laboratory Capacity Assessment; INRA: Rabat, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Soil Salinity Assessment and Mapping in Morocco; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Ben-Laouane, R.; Anli, M.; Boutasknit, A.; Wahbi, S.; Meddich, A. Potential of mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria as a sustainable solution to mitigate salt stress in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Plants 2021, 10, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeli, M.; Korchi, A.; El Khoury, P.; Zahra, A.; Mansouri, K. Hydrogen production from renewable sources in Morocco: Potential, challenges, and prospects. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhchar, A.; Haworth, M.; El Modafar, C.; Lauteri, M.; Mattioni, C.; Wahbi, S.; Centritto, M. An overview of the responses of the endemic argan tree (Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels) to climate change: Ecophysiological adjustments and biotechnological applications. Plants 2022, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wageningen University & Research. Dutch Soil Information System (SIS); Wageningen University & Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://www.wur.nl/en/research-results/research-institutes/environmental-research/facilities-tools/dutch-soil-information-system-sis.htm (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Zayani, K.; Abadie, L.; Karray, B.; Ben-Hammouda, M. Soil organic carbon storage in olive orchards under different management systems in northern Morocco. Agronomy 2023, 13, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morocco. Law No. 53 18 on Fertilizing Materials and Growing Media, Promulgated by Dahir No. 1 21 68 of 3 Dhu al Hijjah 1442 (14 July 2021); No. 7054; Official Bulletin of the Kingdom of Morocco: Rabat, Morocco, 2022.

- Bhusal, D.; Thakur, D.P. Precision nitrogen management on crop production: A review. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2022, 7, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddoughri, F.; Lkammarte, F.Z.; Ait-El-Mokhtar, M.; Baali, A.; Farssi, A.; Arjdal, Y.; Ait-Errouhi, S.; El-Mouhri, A. Analysis of the vulnerability of agriculture to climate and anthropogenic impacts in the Beni Mellal-Khénifra region, Morocco. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussadek, R.; Mrabet, R.; Zouahri, A.; Laghrour, M.; Oueld Lhaj, M.; Dahan, R.; El Mourid, M. Conservation agriculture in Morocco: Review and analysis for the resilience of the cereal system on 1 million hectares by 2030. Afr. Mediterr. Agric. J. 2024, 143, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.