Genotype–Environment Interaction in Shaping the Agronomic Performance of Silage Maize Varieties Cultivated in Organic Farming Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Sites and Environmental Conditions

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Experimental Design and Crop Management

2.4. Weed Infestation Assessment

2.5. Plant Height Measurement

2.6. Biomass Yield and Dry Matter Determination

2.6.1. Fresh Matter Yield Determination

2.6.2. Total Dry Matter Content Determination

2.6.3. Dry Matter Yield Determination

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- −

- is the grand mean;

- −

- and are the main effects of cultivar and environment;

- −

- is the eigenvalue of the k-th IPC;

- −

- and are cultivar and environment IPC scores;

- −

- is the residual error.

2.7.1. Stability Analysis

- −

- is the score of the i-th cultivar on the k-th IPC;

- −

- is the variance explained by the k-th IPC.

2.7.2. Adaptability Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Weed Infestation

3.1.1. Environmental Variation in Weed Pressure

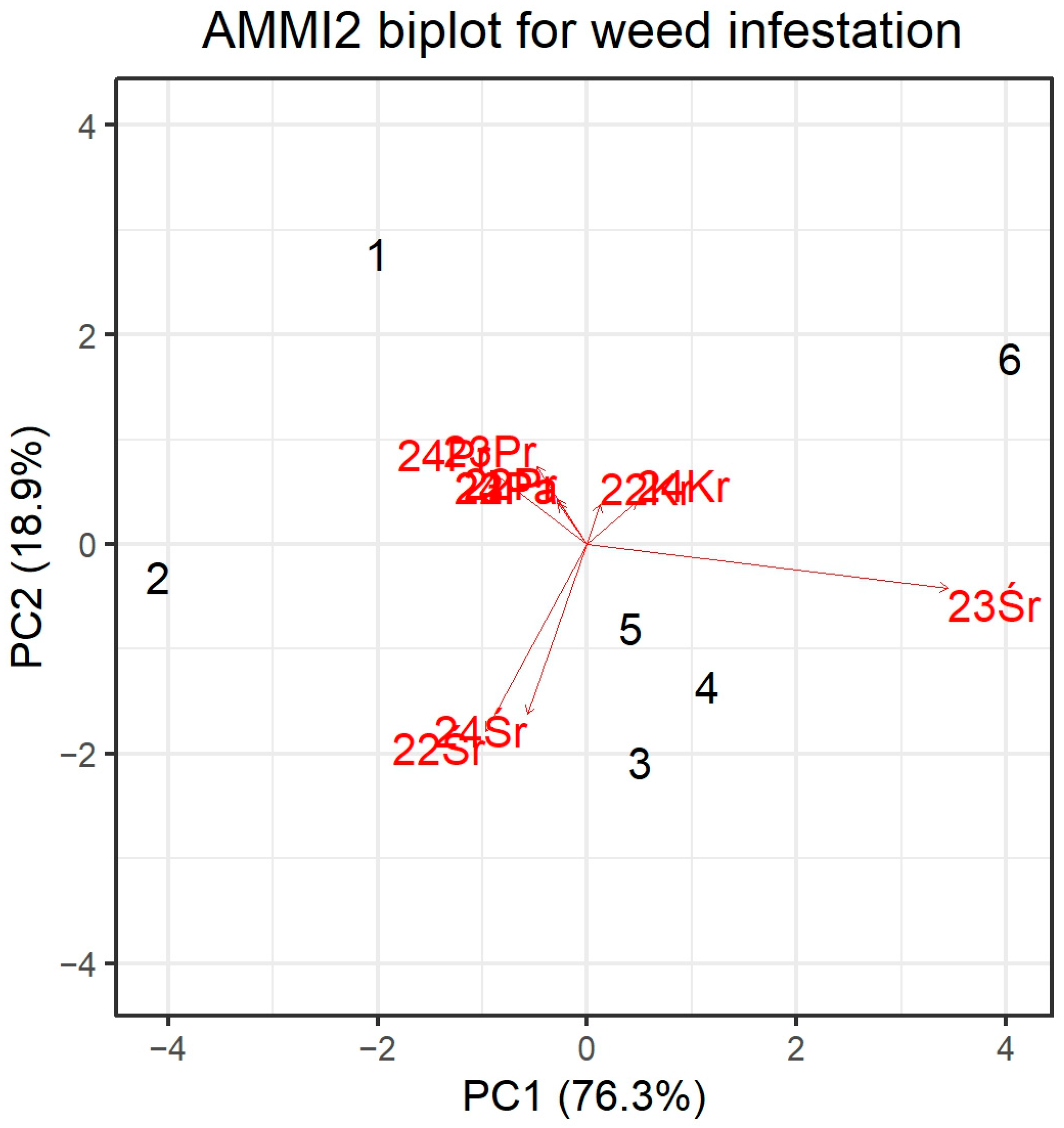

3.1.2. Genotype-Environment Interaction Structure (AMMI) for Weed Infestation

3.1.3. Stability and Adaptability of Cultivars (WAAS, GSI and WTOP2) for Weed Infestation

3.1.4. Identification of Mega-Environments for Weed Infestation

3.2. Plant Height

3.2.1. Environmental Variation in Plant Height

3.2.2. Genotype-Environment Interaction Structure (AMMI) for Plant Height

3.2.3. Stability and Adaptability of Cultivars (WAAS, GSI, WTOP2) for Plant Height

3.2.4. Identification of Mega-Environments for Plant Height

3.3. Fresh Matter Yield

3.3.1. Environmental Variation in Fresh Matter Yield

3.3.2. Genotype-Environment Interaction Structure (AMMI) for Fresh Matter Yield

3.3.3. Stability and Adaptability of Cultivars (WAAS, GSI, WTOP2) for Fresh Matter Yield

3.3.4. Identification of Mega-Environments for Fresh Matter Yield

3.4. Dry Matter Content

3.4.1. Environmental Variation in Dry Matter Content

3.4.2. Genotype-Environment Interaction Structure (AMMI) for Dry Matter Content

3.4.3. Stability and Adaptability of Cultivars (WAAS, GSI, WTOP2) for Dry Matter Content

3.4.4. Identification of Mega-Environments for Dry Matter Content

3.5. Dry Matter Yield

3.5.1. Environmental Variation in Dry Matter Yield

3.5.2. Genotype-Environment Interaction Structure (AMMI) for Dry Matter Yield

3.5.3. Stability and Adaptability of Cultivars (WAAS, GSI, WTOP2) for Dry Matter Yield

3.5.4. Identification of Mega-Environments for Dry Matter Yield

4. Discussion

4.1. Environmental Effects as the Main Driver of Variation and the Role of G × E

4.2. Weed Infestation as a Critical Constraint Under Organic Management

4.3. Plant Height and Architectural Adaptation Across Environments

4.4. Fresh Matter Yield and Dry Matter Yield as Central Indicators of Biomass Productivity

4.5. Dry Matter Content and Implications for Silage Quality and Fermentation

4.6. Cultivar Stability, G × E Interaction and Implications for Organic Maize Breeding

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.A.; Prasanna, B.M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L., Jr. Silage review: Interpretation of chemical, microbial, and organoleptic components of silages. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4020–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Patel, D.P.; Kumar, M.; Ramkrushna, G.I.; Mukherjee, A.; Layek, J.; Buragohain, J. Impact of seven years of organic farming on soil and produce quality and crop yields in Eastern Himalayas, India. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 236, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.; Bocianowski, J.; Nowosad, K.; Zielewicz, W.; Kobus-Cisowska, J. SPAD leaf greenness index: Green mass yield indicator of maize (Zea mays L.), genetic and agriculture practice relationship. Plants 2021, 10, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szulc, P.; Ambroży-Deręgowska, K.; Mejza, I.; Grześ, S.; Zielewicz, W.; Stachowiak, B.; Kardasz, P. Evaluation of nitrogen yield-forming efficiency in the cultivation of maize (Zea mays L.) under different nutrient management systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Kang, M.S.; Ma, B.; Woods, S.; Cornelius, P.L. GGE biplot vs. AMMI analysis of genotype-by-environment data. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauch, H.G., Jr. A simple protocol for AMMI analysis of yield trials. Crop Sci. 2013, 53, 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D.C.; da Silva, J.A.G.; Marchioro, V.S.; de Souza, V.Q.; Jost, E. Mean performance and stability in multi-environment trials I: Combining features of AMMI and BLUP techniques. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2949–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Pan, S.; Zhang, L.; He, X.; Li, R.; Zhang, D.; et al. A study of maize genotype–environment interaction based on deep K-means clustering neural network. Agriculture 2025, 15, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad, A.; Asghari, A.; Moharramnejad, S.; Shiri, M.; Ebadi, A. Integrated analysis of genotype × environment interactions for selecting superior maize genotypes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 41372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozair, F.; Adak, A.; Murray, S.C.; Alpers, R.T.; Aviles, A.C.; Lima, D.C.; Edwards, J.; Ertl, D.; Gore, M.A.; Hirsch, C.N.; et al. Phenotypic plasticity in maize grain yield: Genetic and environmental insights. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Feng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Shen, H.; Hu, H.; Luo, Y.; Xu, L.; Kang, J.; Xing, A.; Wang, S.; et al. Yield and quality properties of silage maize and their influencing factors in China. Sci. China Life Sci. 2022, 65, 1655–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, W.J.; Cherney, D.J.R. Agronomic comparisons of conventional and organic maize during the transition to an organic cropping system. Agronomy 2018, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Áldott-Sipos, Á.; Csepregi-Heilmann, E.; Spitkó, T.; Pintér, J.; Szőke, C.; Berzy, T.; Kovács, A.; Nagy, J.; Marton, C. Evaluation of silage and grain yield of different maize (Zea mays L.) genotypes in organic and conventional conditions. Biologia Plantarum 2024, 68, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 October 2020).

- Bocianowski, J.; Nowosad, K.; Rejek, D. Genotype–environment interaction for grain yield in maize (Zea mays L.) using the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) Model. J. Appl. Genet. 2024, 65, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neves, A.L.; dos Santos, R.D.; Pereira, L.G.; Tabosa, J.N.; de Albuquerque, Í.R.; Neves, A.L.; de Oliveira, G.F.; da Silva Verneque, R. Agronomic characteristics of corn cultivars for silage production. Semina: Ciênc. Agrár. 2015, 36, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandale, P.; Lakaria, B.L.; Aher, S.B.; Singh, A.B.; Gupta, S.C. Performance evaluation of maize cultivars for organic production. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 2433–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Mhlanga, B.; Gama, M.; Museka, R.; Thierfelder, C. Understanding the interactions of genotype with environment and management (G×E×M) to enhance maize productivity in conservation agriculture systems of Malawi. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajoane, T.J. Genotype and Environmental Effects on Maize Grain Yield, Nutritional Value and Milling Quality. Master’s Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2022. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11660/12297 (accessed on 13 October 2023).

- Yue, H.; Olivoto, T.; Bu, J.; Wei, J.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Nardino, M.; Jiang, X. Response of stalk lodging resistance and yield traits of maize to different environments: Dissecting genotype × environment interaction. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjyal, S.; Acharya, R.; Acharya, A.A.; Bohara, S.S. Evaluating the agronomic characteristics and nutritional quality of silage maize varieties. J. Inst. Agric. Anim. Sci. 2024, 38, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Yu, P.; Ali, M.; Cone, J.W.; Hendriks, W.H. Nutritive value of maize silage in relation to dairy cow performance and milk quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Location | GPS Coordinates | Altitude [m a.s.l.] | Voivodeship (Province) | Total Area [ha] | Experimental Crop Rotation [ha] | Main Soil Suitability Complexes | Dominant Soil Quality Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krzyżewo (SDOO 1) | 53.017 N, 22.767 E | 135 | Podlaskie | 209.0 | 160.0 | good wheat, very good rye, good rye, weak rye | II–VI |

| Pawłowice (SDOO) | 50.467 N, 18.483 E | 240 | Silesian | 156.0 | 152.3 | faulty wheat, very good rye, good rye | IIIa–V |

| Przecław (SDOO) | 50.183 N, 21.483 E | 185 | Subcarpathian | 181.5 | 106.1 | very good wheat, good wheat, faulty wheat, very good rye, good rye, weak rye | II–VI |

| Śrem (ZDOO 2) | 52.083 N, 17.033 E | 76 | Greater Poland | 389.0 | 104.3 | very good rye, good rye | II–VI |

| Year | Soil pH (KCl) | Preceding Crop | Sowing Date | Emergence Date | Silking Date | Total Precipitation (April–November) [mm] | Mean Air Temperature (April–November) [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krzyżewo | |||||||

| 2022 | 6.1 | WW | 28 April | 15 May | 27 July | 406 | 14.4 |

| 2023 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2024 | 5.9 | WT | 6 May | 17 May | 13 July | 263 | 17.2 |

| Pawłowice | |||||||

| 2022 | 6.6 | WW | 29 April | 11 May | 24 July | 487 | 14.9 |

| 2023 | 6.4 | FP | 25 April | 15 May | 26 July | 515 | 15.7 |

| 2024 | 6.6 | WR | 26 April | 13 May | 6 July | 425 | 17.9 |

| Przecław | |||||||

| 2022 | 6.1 | OAT | 2 May | 13 May | 17 July | 291 | 15.2 |

| 2023 | 6.1 | WW | 9 May | 27 May | 23 July | 522 | 15.8 |

| 2024 | 7.0 | WW | 18 April | 3 May | 18 July | 371 | 18.0 |

| Śrem | |||||||

| 2022 | 6.1 | WW | 2 May | 10 May | 13 July | 325 | 16.8 |

| 2023 | 6.2 | WW | 2 May | 16 May | 16 July | 314 | 17.1 |

| 2024 | 6.0 | WW | 30 April | 7 May | 6 July | 516 | 18.3 |

| Cultivar | FAO Maturity Group | Hybrid Type | Stay-Green Expression 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Farmoritz | 260 | SC (single-cross) | +++ |

| Geoxx | 240 | SC (single-cross) | ++ |

| SM Grot | 220–230 | TC (three-way cross) | + |

| SM Mieszko | 230 | TC (three-way cross) | ++ |

| SM Perseus | 250 | TC (three-way cross) | ++ |

| SM Varsovia | 250 | TC (three-way cross) | +++ |

| Source of Variation | D.F. | S.S. | M.S. | F | Variability Explained [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | 10 | 30,670.1 | 3067.01 | 147.6538 *** | 96.5 |

| Cultivar | 5 | 88.8 | 17.5 | 0.8547 | 0.3 |

| Interactions | 50 | 1038.6 | 20.77 | 3.3 | |

| PC1 | 14 | 792.9 | 56.64 | 76.3 | |

| PC2 | 12 | 196.3 | 16.36 | 18.9 | |

| Residuals | 24 | 49.3 | 2.06 | 4.8 |

| i | Cultivar | Mean [%] | WAAS | GSI | WTOP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmonitz | 31.13 [1] | 0.3884 [4] | 5 | 0.45 |

| 2 | Geoxx | 31.81 [2] | 0.5416 [5] | 7 | 0.27 |

| 3 | SM Grot | 33.74 [5] | 0.1622 [2] | 7 | 0.54 |

| 4 | SM Mieszko | 34.41 [6] | 0.2112 [3] | 9 | 0.18 |

| 5 | SM Perseus | 33.64 [4] | 0.0911 [1] | 5 | 0 |

| 6 | SM Varsovia | 33.41 [3] | 0.6033 [6] | 9 | 0.54 |

| Source of Variation | D.F. | S.S. | M.S. | F | Variability Explained [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | 10 | 42.797 | 4279.7 | 26.9214 *** | 78.4 |

| Cultivar | 5 | 3857 | 771.4 | 4.8526 ** | 7 |

| Interactions | 50 | 7948 | 159.0 | 14.6 | |

| PC1 | 14 | 3726 | 266.2 | 46.9 | |

| PC2 | 12 | 2438 | 203.1 | 30.7 | |

| PC3 | 10 | 1471 | 147.1 | 18.5 | |

| Residuals | 24 | 314 | 22.4 | 3.9 |

| i | Cultivar | Mean [cm] | WAAS | GSI | WTOP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmonitz | 233.61 [6] | 0.4506 [6] | 12 | 0.09 |

| 2 | Geoxx | 248.82 [3] | 0.3030 [2] | 5 | 0.18 |

| 3 | SM Grot | 236.69 [5] | 0.3378 [3] | 8 | 0.18 |

| 4 | SM Mieszko | 246.19 [4] | 0.3453 [4] | 8 | 0.27 |

| 5 | SM Perseus | 253.57 [1] | 0.3919 [5] | 6 | 0.55 |

| 6 | SM Varsovia | 252.93 [2] | 0.2776 [1] | 3 | 0.73 |

| Source of Variation | D.F. | S.S. | M.S. | F | Variability Explained [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | 10 | 368.682 | 36.868 | 45.6963 *** | 87.1 |

| Cultivar | 5 | 14.569 | 2914 | 3.6116 ** | 3.4 |

| Interactions | 50 | 40.340 | 807 | 9.5 | |

| PC1 | 14 | 23.050 | 1646 | 57.1 | |

| PC2 | 12 | 6328 | 527 | 15.7 | |

| Residuals | 24 | 10.962 | 457 | 27.2 |

| i | Cultivar | Mean [t·ha−1] | WAAS | GSI | WTOP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmonitz | 35.28 [4] | 0.2835 [3] | 7 | 0.27 |

| 2 | Geoxx | 34.93 [5] | 0.1719 [1] | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | SM Grot | 33.71 [6] | 0.5460 [5] | 11 | 0.18 |

| 4 | SM Mieszko | 35.54 [3] | 0.1773 [2] | 5 | 0.18 |

| 5 | SM Perseus | 38.40 [1] | 0.4514 [4] | 5 | 0.64 |

| 6 | SM Varsovia | 36.90 [2] | 0.5474 [6] | 8 | 0.73 |

| Source of Variation | D.F. | S.S. | M.S. | F | Variability Explained [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | 10 | 986.77 | 98.677 | 27.9941 *** | 80.6 |

| Cultivar | 5 | 61.02 | 12.204 | 3.4622 ** | 5 |

| Interactions | 50 | 176.25 | 3.525 | 14.4 | |

| PC1 | 14 | 86.01 | 6.144 | 48.8 | |

| PC2 | 12 | 58.89 | 4.907 | 33.4 | |

| Residuals | 24 | 31.35 | 1.306 | 17.8 |

| i | Cultivar | Mean [%] | WAAS | GSI | WTOP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmonitz | 35.52 [2] | 0.5132 [6] | 8 | 0.27 |

| 2 | Geoxx | 37.50 [3] | 0.1246 [4] | 7 | 0.45 |

| 3 | SM Grot | 37.40 [4] | 0.3809 [2] | 6 | 0.55 |

| 4 | SM Mieszko | 37.73 [1] | 0.3252 [1] | 2 | 0.45 |

| 5 | SM Perseus | 35.37 [6] | 0.3101 [3] | 9 | 0.09 |

| 6 | SM Varsovia | 36.23 [5] | 0.4013 [5] | 10 | 0.18 |

| Source of Variation | D.F. | S.S. | M.S. | F | Variability Explained [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environment | 10 | 65.019 | 6501.9 | 57.3059 *** | 90.8 |

| Cultivar | 5 | 920 | 184 | 1.6214 | 1.3 |

| Interactions | 50 | 5673 | 113.5 | 7.9 | |

| PC1 | 14 | 2201 | 157.2 | 38.8 | |

| PC2 | 12 | 1409 | 117.4 | 24.8 | |

| Residuals | 24 | 2064 | 86 | 36.4 |

| i | Cultivar | Mean [t·ha−1] | WAAS | GSI | WTOP2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmonitz | 12.54 [6] | 0.5730 [6] | 12 | 0.18 |

| 2 | Geoxx | 13.12 [4] | 0.3583 [4] | 8 | 0.18 |

| 3 | SM Grot | 12.66 [5] | 0.2152 [2] | 7 | 0 |

| 4 | SM Mieszko | 13.44 [2] | 0.0895 [1] | 3 | 0.36 |

| 5 | SM Perseus | 13.53 [1] | 0.2594 [3] | 4 | 0.63 |

| 6 | SM Varsovia | 13.29 [3] | 0.5122 [5] | 8 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Marcinkowska, K.; Kolańska, K.; Banaś, K.; Łacka, A.; Lenartowicz, T.; Szulc, P.; Bujak, H. Genotype–Environment Interaction in Shaping the Agronomic Performance of Silage Maize Varieties Cultivated in Organic Farming Systems. Agriculture 2026, 16, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010123

Marcinkowska K, Kolańska K, Banaś K, Łacka A, Lenartowicz T, Szulc P, Bujak H. Genotype–Environment Interaction in Shaping the Agronomic Performance of Silage Maize Varieties Cultivated in Organic Farming Systems. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcinkowska, Katarzyna, Karolina Kolańska, Konrad Banaś, Agnieszka Łacka, Tomasz Lenartowicz, Piotr Szulc, and Henryk Bujak. 2026. "Genotype–Environment Interaction in Shaping the Agronomic Performance of Silage Maize Varieties Cultivated in Organic Farming Systems" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010123

APA StyleMarcinkowska, K., Kolańska, K., Banaś, K., Łacka, A., Lenartowicz, T., Szulc, P., & Bujak, H. (2026). Genotype–Environment Interaction in Shaping the Agronomic Performance of Silage Maize Varieties Cultivated in Organic Farming Systems. Agriculture, 16(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010123