Effects of Photovoltaic-Integrated Tea Plantation on Tea Field Productivity and Tea Leaf Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of PVtea Plantation

2.2. Investigation on Ambient Temperature and Humidity

2.3. Observation on Tea Sprouting in Spring

2.4. Investigation on the Yield of Fresh Tea Leaf

2.5. Measurement of Tea Leaf Length, Width, and Leaf Area

2.6. Test of Activity of Leaf Photosystem II (PSII)

2.7. Determination of Quality-Related Chemical Components in Tea

2.7.1. Leaf Extraction

2.7.2. Determination of Amino Acids

2.7.3. Determination of Catechins and Caffeine

2.7.4. Analysis of Photosynthetic Pigments

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of PV Modules on Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR)

3.2. Effects of PV Modules on Ambient Temperature and Humidity

3.3. Effects of PV Modules on the Sprouting of Spring Shoots

3.4. Effects of PV Modules on Fresh Leaf Yield

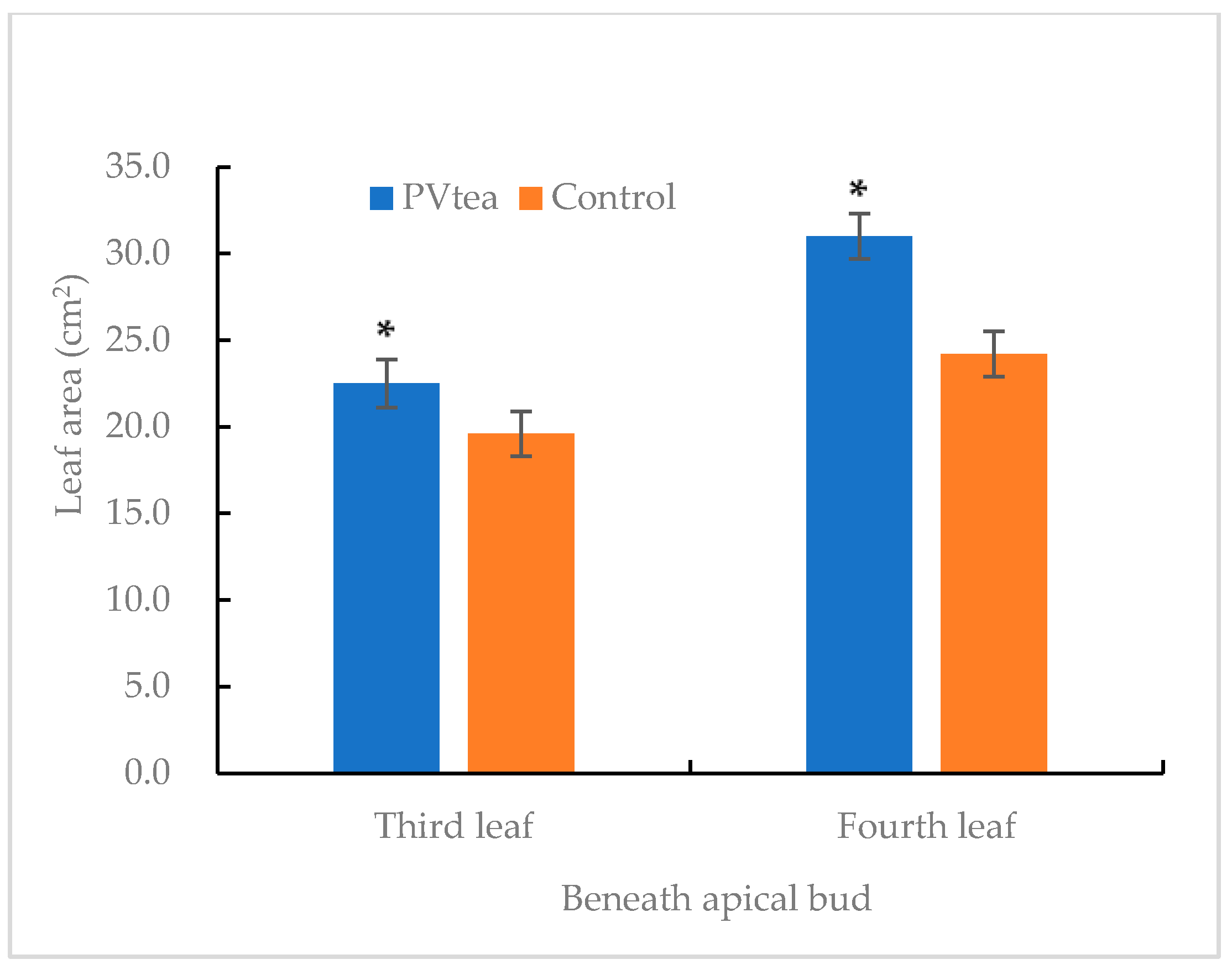

3.5. Effect of PV Modules on Weight of Shoots and Leaf Size

3.6. Effect of PV Modules on Tea Quality-Related Phytochemicals

3.7. Effect of PV Modules on Resistance of Tea Plants to Environmental Stress

3.7.1. Resistance to Frost Damage in the Early Spring

3.7.2. Resistance to Heat Damage in Summer

4. Discussions

4.1. PV Modules Increase Tea Productivity by Mitigating Photodamage to Tea Leaves from Intense Sunlight

4.2. PVtea Is a Sustainable Model to Combat the Negative Impacts of Extreme Weather on Tea

4.2.1. Protecting Tea Plants Against Frost Damage

4.2.2. Protecting Tea Plants Against Heat Damage

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, L.; Tan, Z.F. The potential of renewable energy for the alleviation of climate change in China. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 278–280, 2308–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heremans, G.; Trompoukis, C.; Daems, N.; Bosserez, T.; Vankelecom, I.F.J.; Martens, J.A.; Rongé, J. Vapor-fed solar hydrogen production exceeding 15% efficiency using earth abundant catalysts and anion exchange membrane. Sustain. Energ. Fuels 2017, 1, 2061–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trommsdorff, M.; Kang, J.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S.; Bopp, G.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Högy, P.; Obergfell, T. Combining food and energy production: Design of an agrivoltaic system applied in arable and vegetable farming in Germany. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 140, 110694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeddies, H.H.; Parlasca, M.; Qaim, M. Agrivoltaics increases public acceptance of solar energy production on agricultural land. Land Use Policy 2025, 156, 107604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gong, J.; Xiao, C.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Song, L.; Zhang, W.; Dong, X.; Hu, Y. Bupleurum chinense and Medicago sativa sustain their growth in agrophotovoltaic systems by regulating photosynthetic mechanisms. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2024, 189, 114024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, N.C.; Mohanty, R.C. Turmeric crop farming potential under Agrivoltaic system over open field practice in Odisha, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.P. A digital business model for accelerating distributed renewable energy expansion in rural China. Appl. Energ. 2022, 316, 119084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bi, G.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Xing, Z.; LeCompte, J.; Harkess, R.L. Color shade nets affect plant growth and seasonal leaf quality of Camellia sinensis grown in Mississippi, the United States. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 786421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Banerjee, S.; Sarkar, S. Productivity and radiation use efficiency of tea grown under different shade trees in the plain land of West Bengal. J. Agrometeorol. 2018, 10, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahe, J.; Krahe, M.A. Optimizing the quality and commercial value of gyokuro-styled green tea grown in Australia. Beverages 2022, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Liang, X. Annual Report on China’s Tea Production and Sales in 2023, China Tea Marketing Association, Updated to 16 April 2024. Available online: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/JcL0ww7dHZKaGexvKXoiaA (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Jiang, C.J. Tea Breeding, 2nd ed.; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Ma, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, L. Function of ROC4 in the efficient repair of photodamaged photosystem II in Arabidopsis. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 1343–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-H.; Zheng, X.-Q.; Liang, Y.-R. High-light-induced degradation of photosystem II subunits’ involvement in the albino phenotype in tea plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.R.; Wu, Y.; Lu, J.L.; Zhang, L.Y. Application of chemical composition and infusion colour difference analysis to quality estimation of jasmine-scented tea. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.-Q.; Dong, S.-L.; Li, Z.-Y.; Lu, J.-L.; Ye, J.-H.; Tao, S.-K.; Hu, Y.-P.; Liang, Y.-R. Variation of major chemical composition in seed-propagated population of wild cocoa tea plant Camellia ptilophylla Chang. Foods 2023, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.F.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.Q. Effect of soil water stress on photosynthetic light response curve of tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2008, 16, 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Zhu, Q.; Tukhvatshin, M.; Cheng, B.; Tan, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, S.; Lin, D.; et al. Light control of catechin accumulation is mediated by photosynthetic capacity in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohotti, A.J.; Lawlor, D.W. Diurnal variation of photosynthesis and photoinhibition in tea: Effects of irradiance and nitrogen supply during growth in the field. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, P.; Marat, T.; Huang, J.; Cheng, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Tan, M.; Zhu, Q.; Lin, J. Response of photosynthetic capacity to ecological factors and its relationship with EGCG biosynthesis of tea plant (Camellia sinensis). BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S. Interaction of light and low temperature in depression of photosynthesis in tea leaves. Jpn. J. Crop. Sci. 1986, 55, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.H.; Ma, L.F.; Yang, X.D.; Fang, L. Effects of nitrogen form and weak light stress on tea plant growth and metabolism. J. Tea Sci. 2023, 43, 349–355. Available online: https://www.tea-science.com/EN/10.13305/j.cnki.jts.2023.03.01 (accessed on 30 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Kotikot, S.M.; Flores, A.; Griffin, R.E.; Nyaga, J.; Case, J.L.; Mugo, R.; Sedah, A.; Adams, E.; Limaye, A.; Irwin, D.E. Statistical characterization of frost zones: Case of tea freeze damage in the Kenyan highlands. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 84, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, T.; Yang, M.; Deng, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, S. Frost risk assessment based on the frost-induced injury rate of tea buds: A case study of the Yuezhou Longjing tea production area, China. Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 147, 126839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Ji, Z.; Sun, K.; Zhou, J. Application of remote sensing and GIS for assessing economic loss caused by frost damage to tea plantations. Precis. Agric. 2013, 14, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tang, J.; Ma, Y.; Wu, D.; Yang, J.; Jin, Z.; Huo, Z. Mapping threats of spring frost damage to tea plants using satellite-based minimum temperature estimation in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Ma, Y.; Tang, J.; Wu, D.; Chen, H.; Jin, Z.; Huo, Z. Spring frost damage to tea plants can be identified with daily minimum air temperatures estimated by MODIS land surface temperature products. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omae, H.; Takeda, Y. Selection of early lines without frost damage based on parameters of accumulated temperature for flushing and opening speed of new leaves in tea. JARQ—Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2003, 37, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Yasutake, D.; Nakazono, K.; Kitano, M. Dynamic distribution of thermal effects of an oscillating frost protective fan in a tea field. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 164, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Pan, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liu, W. Vortex characteristics downstream a fan and its effect on the heat transfer of the temperature inversion under late spring coldness. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814017704353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Pan, Q.; Lu, Y. Heat transfer process of the tea plant under the action of air disturbance frost protection. Agronomy 2024, 14, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Lu, Y.; Hu, Y. Influences of sprinkler frost protection on air and soil temperature and chlorophyll fluorescence of tea plants in tea gardens. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Kudo, K.; Maruyama, A. Spatiotemporal distribution of the potential risk of frost damage in tea fields from 1981-2020: A modeling approach considering phenology and meteorology. J. Agric. Meteorol. 2021, 77, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Wu, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Jin, Z.; Huo, Z. Disaster event-based spring frost damage identification indicator for tea plants and its applications over the region north of the Yangtze River, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, P.F.; Amoah, A.E.; Li, P. Sprinkler irrigation system for tea frost protection and the application effect. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2016, 9, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Snyder, R.L. Modification of water application rates and intermittent control for sprinkler frost protection. Trans. ASABE 2018, 61, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Hu, Y. Reasons of sprinkler freezing and rotational irrigation for frost protection in tea plantations. Irrig. Drain. 2025, 74, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gao, Y.; Fan, K.; Shi, Y.; Luo, D.; Shen, J.; Ding, Z.; Wang, Y. Prediction of drought-induced components and evaluation of drought damage of tea plants based on hyperspectral imaging. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 695102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hou, J.; Zhou, B.; Han, X. Effects of water supply mode on nitrogen transformation and ammonia oxidation microorganisms in a tea garden. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, X.; Tang, J.; Wu, D.; Pang, L.; Zhang, Y. Critical threshold-based heat damage evolution monitoring to tea plants with remotely sensed LST over mainland China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, X.; Tang, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, Y.; Wu, D.; Huo, Z. Determining the critical threshold of meteorological heat damage to tea plants based on MODIS LST products for tea planting areas in China. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.; Maritim, T.K.; Parmar, R.; Sharma, R.K. Underpinning the molecular programming attributing heat stress associated thermotolerance in tea (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze). Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaeikar, S.S.; Marzvan, S.; Khiavi, S.J.; Rahimi, M. Changes in growth, biochemical, and chemical characteristics and alteration of the antioxidant defense system in the leaves of tea clones (Camellia sinensis L.) under drought stress. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalina, M.; Saroja, S.; Chakravarthi, M.; Rajkumar, R.; Radhakrishnan, B.; Chandrashekara, K.N. Water deficit-induced oxidative stress and differential response in antioxidant enzymes of tolerant and susceptible tea cultivars under field condition. Acta Physiol. Plant 2021, 43, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Qiu, C.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, L.; Fan, K.; Gai, Z.; Dong, G.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Fulvic acid ameliorates drought stress-induced damage in tea plants by regulating the ascorbate metabolism and flavonoids biosynthesis. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date | Treatment | Number of Shoots with One Leaf and a Bud | Number of Shoots with Two Leaves and a Bud | Number of Shoots with Three Leaves and a Bud | Sprouting Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 April 2018 | PVtea | 18.00 ± 7.57 | 123.00 ± 14.22 | 60.00 ± 13.58 * | 3.21 ± 0.11 * |

| Control | 17.00 ± 7.00 | 120.00 ± 20.81 | 42.00 ± 10.97 | 3.14 ± 0.10 | |

| 26 March 2019 | PVtea | 49.33 ± 15.63 | 18.67 ± 14.22 * | 1.00 ± 1.73 * | 2.22 ± 0.13 * |

| Control | 56.00 ± 15.87 | 12.33 ± 8.08 | 0 | 2.01 ± 0.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, X.-Q.; Zhang, X.-H.; Zhang, J.-G.; Zheng, R.-J.; Lu, J.-L.; Ye, J.-H.; Liang, Y.-R. Effects of Photovoltaic-Integrated Tea Plantation on Tea Field Productivity and Tea Leaf Quality. Agriculture 2026, 16, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010125

Zheng X-Q, Zhang X-H, Zhang J-G, Zheng R-J, Lu J-L, Ye J-H, Liang Y-R. Effects of Photovoltaic-Integrated Tea Plantation on Tea Field Productivity and Tea Leaf Quality. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010125

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Xin-Qiang, Xue-Han Zhang, Jian-Gao Zhang, Rong-Jin Zheng, Jian-Liang Lu, Jian-Hui Ye, and Yue-Rong Liang. 2026. "Effects of Photovoltaic-Integrated Tea Plantation on Tea Field Productivity and Tea Leaf Quality" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010125

APA StyleZheng, X.-Q., Zhang, X.-H., Zhang, J.-G., Zheng, R.-J., Lu, J.-L., Ye, J.-H., & Liang, Y.-R. (2026). Effects of Photovoltaic-Integrated Tea Plantation on Tea Field Productivity and Tea Leaf Quality. Agriculture, 16(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010125