Abstract

Grading of table grapes depends on reliable berry-level phenotyping, yet manual inspection is subjective and slow. A wavelet-guided instance segmentation network named WGMG-Net is introduced for automated assessment of post-harvest grape clusters. A multi-scale feature merging module based on discrete wavelet transform is used to preserve edges under dense occlusion, and a bivariate fusion enhanced attention mechanism is used to strengthen channel and spatial cues. Instance masks are produced for all berries, a regression head estimates the total berry count, and a mask-derived compactness index assigns clusters to three tightness grades. On a Shine Muscat dataset with 252 cluster images acquired on a simulated sorting line, the WGMG-Net variant attains a mean average precision at Intersection over Union (IoU) 0.5 of 98.98 percent and at IoU 0.5 to 0.95 of 87.76 percent, outperforming Mask R-CNN, PointRend and YOLO models with fewer parameters. For berry counting, a mean absolute error of 1.10 berries, root mean square error of 1.48 berries, mean absolute percentage error of 2.82 percent, accuracy within two berries of 92.86 percent and Pearson correlation of 0.986 are achieved. Compactness grading reaches Top-1 accuracy of 98.04 percent and Top-2 accuracy of 100 percent, supporting the use of WGMG-Net for grape quality evaluation.

1. Introduction

In the era of Industry 4.0, the convergence of industrial informatics, artificial intelligence (AI), and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) is fundamentally reshaping manufacturing and processing industries [1,2]. A pivotal element of this transformation lies in deploying intelligent automated quality control (QC) systems [3]. These machine vision-based systems are progressively replacing manual inspection—a process notorious for its subjectivity and labor-intensive nature—which has become a major bottleneck in high-output production [4]. Particularly for the agri-food sector, automated non-destructive quality assessment technologies promise substantial benefits, being crucial for grading-based pricing and optimizing storage and logistics [5,6].

As a globally high-value commodity, grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) present a highly challenging case study for automated quality assessment. Their commercial value directly depends on postharvest phenotypic traits such as berry size, color, number of berries per cluster, and bunch compactness [7,8]. However, the complex three-dimensional structure of grape clusters—including severe berry occlusion, irregular shapes, and subtle inter-berry variations (e.g., unripe vs. ripe berries)—poses significant challenges for computer vision systems [9]. Traditional image processing techniques relying on manually designed features (e.g., color histograms, edge detection, or watershed algorithms) have proven incapable of delivering reliable segmentation results in such cluttered and complex scenes [10,11].

The emergence of deep learning, particularly the application of convolutional neural networks (CNNs), has sparked a paradigm shift in agricultural object detection [12,13]. Instance segmentation models such as Mask R-CNN have been widely applied to pixel-level fruit detection tasks, including grape cluster recognition [14,15]. These methods demonstrate potential when handling moderate occlusion [16]. Despite progress, significant gaps persist that hinder their successful deployment on actual industrial sorting lines.

The core industrial bottleneck lies in the critical trade-off between accuracy and real-time processing speed [17]. While state-of-the-art instance segmentation models like PointRend [18] or the latest YOLOv11 [19] achieve high accuracy, they often demand substantial computational resources. This high overhead renders them unsuitable for “in-line” (real-time) detection on industrial conveyor belts—a scenario demanding high-speed inference (e.g., >30 frames per second) to match sorting equipment throughput [20,21]. Secondly, existing models are predominantly designed for single tasks (e.g., segmentation or counting), whereas industrial grading standards require multi-parameter comprehensive evaluation [22]. Systems providing only segmentation masks are incomplete; industrial viability necessitates quantifying key phenotypic traits like berry count and cluster compactness [23]. Finally, many academic models lack the software architecture required for deployment, data logging, and decision-making, as they were not designed as part of integrated information systems [24].

To address these industrial gaps, this paper proposes a two-stage integrated framework for real-time automated assessment of grape post-harvest quality. The solution comprises two components: First, a high-speed instance segmentation network named Wavelet-Guided Multi-Task Grape Network (WGMG-Net) is developed. WGMG-Net is explicitly designed to balance accuracy and efficiency. It innovatively incorporates discrete wavelet transform technology to effectively preserve high-frequency edges and texture details often lost by standard convolutional algorithms [25,26,27], while integrating a Bivariate Fusion Enhanced Attention Mechanism (BFEAM) to precisely analyze features in densely occluded regions [28]. Trained as a multi-task model, this network simultaneously performs instance segmentation and berry counting. Subsequently, we apply novel morphological post-processing algorithms to precisely quantify complex “compactness” traits using the high-precision masks generated by WGMG-Net. This integrated workflow delivers a complete multi-parameter analysis solution meeting industry standards.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

(1) Replacing a standard FPN-style feature fusion with the proposed DWT-based MSFM preserves high-frequency edge details under dense occlusion and increases mAP@0.5:0.95 on dense grape clusters, under comparable computational complexity.

(2) The proposed BFEAM attention mechanism yields higher mAP@0.5, mAP@0.75 and mAP@0.5:0.95 than representative attention modules, while maintaining a comparable or lower FLOP cost.

(3) The task-specific WGMG-Net architecture achieves a more favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off than strong generic detectors such as YOLOv11/YOLOv12, i.e., higher mAP@0.5:0.95 with fewer parameters and FLOPs on the grape segmentation task.

(4) When integrated into a two-stage phenotyping pipeline, WGMG-Net provides berry-count and compactness estimates that are strongly consistent with manual assessment, as quantified by low RMSE and high Pearson correlation.

2. Related Work

2.1. Instance Segmentation Models for Agricultural Vision

Significant progress has been made in automated segmentation technology for agricultural products. Foundational methods employ traditional image processing techniques such as thresholding, edge detection, and watershed algorithms [29,30]. However, their sensitivity to variations in lighting, color, and texture limits their robustness for deployment in demanding industrial environments [31].

Deep learning, particularly instance segmentation, has emerged as the mainstream paradigm. Models under this paradigm are typically categorized into two-stage and single-stage architectures, each offering distinct advantages and disadvantages for industrial applicability.

Two-stage models: Mask R-CNN [32] and its derivative architectures [33] prioritize segmentation accuracy. These models typically generate region proposals (RoIs) first, then perform classification and mask prediction within each RoI. This approach yields high-quality, accurate segmentation masks. PointRend [18] serves as an optimization technique, achieving sharper object boundaries through edge-adaptive point sampling. Multiple studies have applied Mask R-CNN to grape cluster and berry segmentation, demonstrating encouraging accuracy in controlled laboratory settings [34]. However, a key limitation of such two-stage models lies in inference speed. The sequential processing inherent in the proposal and refinement stages causes significant computational latency. Consequently, models like Mask R-CNN and PointRend often fail to meet the real-time throughput requirements (e.g., >30 frames per second) demanded by industrial sorting conveyor belts [35].

One-Stage Models: To overcome the speed limitations of two-stage models, one-stage architectures like YOLACT [36], SOLOv2 [37], and the segmentation-capable versions of the YOLO family have gained prominence. These models perform object detection and mask generation concurrently in a single forward pass, achieving substantially higher inference speeds suitable for industrial informatics applications [35]. However, this gain in speed frequently entails a compromise in segmentation quality. One-stage models often exhibit difficulties in precisely delineating object boundaries and separating heavily overlapping instances, particularly in cluttered visual fields like dense grape clusters. Common failure modes include mask bleeding between instances, merging of adjacent objects, and inadequate edge fidelity, which can significantly impair the accuracy of subsequent phenotypic analyses.

2.2. Feature Enhancement for Detail Preservation and Occlusion Handling

Addressing the challenge of degraded segmentation quality in high-density scenes requires sophisticated feature representation techniques.

Attention Mechanisms: Attention modules, exemplified by Squeeze-Excite (SE) [38] and Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) [39], are frequently integrated into segmentation networks. These mechanisms enable models to adaptively recalibrate feature responses, emphasizing critical information while suppressing irrelevant background noise [40]. While standard attention mechanisms generally enhance model performance, they do not explicitly preserve the critical high-frequency spatial information required for precise object boundary definition.

Feature Fusion Strategies: Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs) [41] have become standard architectural components in modern object detectors. FPNs integrate low-level high-resolution feature maps with high-level low-resolution feature maps by fusing features from different network levels. While this architecture excels in multi-scale object detection, the repeated application of standard 3 × 3 convolutions and pooling operations within the CNN backbone leads to the attenuation and loss of fine textures and sharp edge details [42].

Applications of Wavelet Transform in Deep Learning: Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) is a mature technical tool in signal processing, capable of decomposing signals into independent frequency bands to separate low-frequency structural information from high-frequency detail information [43]. Integrating DWT into deep learning frameworks enables systematic capture and preservation of high-frequency components often lost in traditional CNN architectures. Despite its significant potential, the application of wavelet transforms in high-speed industrial-grade instance segmentation models remains relatively scarce. This gap presents an opportunity to develop networks that combine the speed advantages of single-stage models with the boundary accuracy conferred by detail retention in the wavelet domain.

2.3. Multi-Parameter Phenotyping and Multi-Task Learning

Industrial grading protocols require quantitative measurements beyond simple object segmentation [44]. Multi-task learning (MTL) approaches have been explored in agricultural applications, such as jointly predicting fruit quality attributes with segmentation [45] or combining detection with counting. However, these tasks often remain loosely coupled. For instance, counting functions are typically applied as post-processing steps to prediction masks, making them highly susceptible to errors when segmentation models incorrectly merge instances. Furthermore, complex morphological features—such as “cluster compactness,” a key indicator in grape grading—are rarely addressed in end-to-end deep learning models. This stems primarily from the difficulty of constructing suitable differentiable loss functions for such abstract structural attributes.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Image Acquisition Setup

The experimental material was acquired on 19 February 2025. All data collection was conducted in a controlled environment. The image acquisition device was a DS77C Pro camera (resolution 1600 × 1200 pixels)(Vzense; Shenzhen, China).

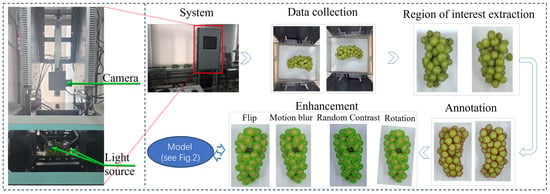

All grape images in this study were collected using a laboratory prototype that simulated an industrial sorting-line environment. The camera, lens, and conveyor belt were fixed, and illumination was provided by a stable LED light source with constant intensity and color temperature. During acquisition, the operator manually rotated each grape cluster on the holder between consecutive frames to expose different sides of the cluster to the camera. This protocol reduces variability in camera–object geometry, eliminates abrupt changes in lighting, and limits unpredictable occlusion patterns, thereby creating a controlled setting that is convenient for algorithm development and benchmarking. As shown in Figure 1, grape samples were placed on a 20 cm high platform. A camera was mounted 60 cm directly above the platform, with two supplementary lights positioned 30 cm on either side to provide uniform, shadow-free illumination.

Figure 1.

Data preprocessing map including region of interest extraction, data labeling and data enhancement modules.

3.1.2. Dataset Curation and Preprocessing

All grape samples were commercial table grapes of the same cultivar, Shine Muscat. In the main acquisition session, 126 distinct grape clusters were collected. Each cluster was manually rotated during image acquisition to obtain multi-angle views, and two RGB images were captured per cluster, resulting in 252 raw images corresponding to 126 unique physical clusters. The clusters covered a range of sizes and compactness levels and exhibited natural variation in berry size and surface appearance as encountered in commercial grading, while severely damaged or moldy clusters were excluded. To further assess cross-batch robustness, an additional batch of 25 “Shine Muscat” clusters was purchased from a different supplier on 10 October 2025 and imaged with the same system; these samples were used only for the transfer experiment described below and were not included in the 252-image main dataset.

Considering the robustness of the Hue–Saturation–Value (HSV) color space to moderate illumination changes, this study employed an HSV-based color thresholding method to automatically extract the grape cluster regions of interest (ROIs) and remove the background. The extracted ROI images were then manually refined and precisely annotated using the LabelMe tool, including instance segmentation masks for individual berries and corresponding class labels. The resulting dataset is specifically designed to emphasize highly dense and overlapping berries, providing a challenging benchmark for testing instance segmentation robustness under strong occlusion.

The 252 images in the main dataset were split at the cluster level into training (176 images), validation (50 images), and test (26 images) subsets following a 7:2:1 ratio, ensuring that all images of the same physical cluster were assigned to a single subset to avoid information leakage. This ratio was chosen as a compromise between (i) providing a sufficiently large training set for deep network optimization, (ii) retaining a validation set large enough for hyper-parameter tuning and early stopping, and (iii) keeping an independent internal test set for unbiased performance evaluation, given the limited total number of clusters. Data augmentation (random rotations, flips, and mild brightness/contrast jittering) was applied only to the training images in order to increase sample diversity; the validation and internal test sets remained unaugmented to provide a fair estimate of generalization.

In addition to the internal 7:2:1 split, a transfer-style experiment was designed to evaluate the model’s robustness to session and batch shifts. The network is trained on images from the main acquisition session (252 images from 126 clusters) and directly tested on the second batch of 5 clusters acquired on 10 October 2025 under slightly different acquisition conditions (different batch and supplier, with inevitable small changes in lighting and camera–sample distance), without any fine-tuning. This protocol simulates a practical deployment scenario in which a model trained on one batch or session must generalize to newly arriving grape batches acquired on another day.

To enhance model generalization and simulate positional and lighting variations in industrial settings, multiple data augmentation techniques were applied. These include image rotation (5°, 10°, 15°), flipping (horizontal and vertical), color space transformations (random adjustments to hue, saturation, and brightness), and blurring (Gaussian blur, motion blur). Following augmentation, the original training set was expanded to 12,652 images.

3.2. The Integrated Phenotyping Pipeline

To address the need for multidimensional phenotypic analysis in industrial sorting, this study proposes an integrated two-stage processing pipeline, as illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3. This framework combines deep learning models with deterministic morphological algorithms:

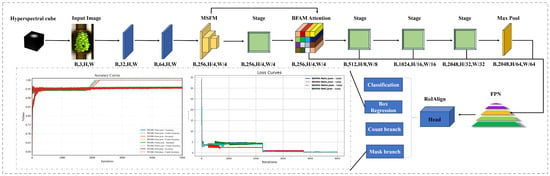

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the proposed WGMG-Net multi-task framework for grape cluster instance segmentation and berry counting, together with its training convergence. Top: starting from images acquired by the in-house imaging system, features are extracted by the backbone network, refined by the MSFM multi-scale feature merging module and the BFEAM dual-branch attention module, and then fed into a unified prediction head to jointly perform classification, bounding-box regression, berry counting, and instance mask prediction. Bottom: training accuracy and loss curves of different WGMG-Net variants, demonstrating fast convergence and stable performance after several thousand iterations.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the proposed grape cluster compactness quantification. (Top row): original RGB images of grape clusters belonging to compactness Types 1–3 defined in this study. (Middle row): binary masks of the clusters obtained from the instance segmentation model, where berries are shown in white and the background in black; large gaps between adjacent berries appear as internal holes in the mask. (Bottom row): results of connected-component analysis on the internal holes, represented by rectangular bounding boxes. Each white box denotes a candidate void region, with the width × height (in pixels) annotated next to it; red boxes highlight the dominant void regions used to compute the compactness index for the corresponding cluster. From left to right, the three columns show representative samples of compactness Types 1, 2, and 3.

(1) WGMG-Net (Segmentation and Counting): The input image is first fed into WGMG-Net. This network is optimized to perform two parallel tasks: high-precision instance segmentation for each visible grape berry; and direct regression of the total number of berries across the entire image.

(2) Morphological Compactness Algorithm: The high-fidelity binary mask generated by WGMG-Net, representing the entire grape cluster, is fed into a deterministic morphological post-processing algorithm. This algorithm classifies the “compactness” of the fruit cluster by analyzing voids and gaps within the mask.

3.3. WGMG-Net Architecture

3.3.1. Multi-Scale Feature Merging Module (MSFM)

Conventional multi-scale feature extraction in instance segmentation mainly relies on feature pyramid networks (FPN) or spatial pyramid pooling, which repeatedly apply 3 × 3 convolutions and pooling to aggregate features at different resolutions [41,42]. While effective for generic object detection, these isotropic operations tend to smooth out high-frequency edge and texture information that is critical for separating densely packed grape berries whose boundaries are often only a few pixels wide. At the same time, previous studies have shown that discrete wavelet transforms (DWT) can explicitly decompose an image into low-frequency structural components and high-frequency detail components, thereby improving edge preservation in agricultural and remote-sensing images [25,26,27].

In the MSFM, the first- and second-level wavelet decompositions are applied in a hierarchical manner. As shown as Figure 4, the first-level DWT is performed directly on the backbone feature map and produces one low-frequency sub-band (LL) and three high-frequency sub-bands . These first-level HF components encode fine local edges and small gaps between neighboring berries at the original spatial resolution. In the second step, we do not decompose the whole feature map again; instead, we apply another DWT only to the first-level low-frequency component . This yields the second-level low-frequency sub-band and the second-level HF sub-bands at a lower spatial resolution. Consequently, the first-level HF features focus on detailed textures, while the second-level HF features capture coarser structural variations such as cluster shape and large inter-berry gaps. By enhancing and fusing the HF features from both levels, MSFM builds a multi-scale representation that jointly models fine details and global structure.

Figure 4.

Overall architecture of the proposed MSFM in WGMG-Net. The backbone features of a grape cluster are first decomposed by multi-level wavelet transforms and fused into a frequency-aware multi-scale representation (MSFM), which is then refined by the bivariate channel–spatial attention mechanism (BFEAM) to produce compact features for precise instance segmentation and phenotypic prediction.

Building on these insights, the proposed MSFM integrates DWT into the backbone and performs direction-sensitive convolutions on the HL, LH and HH wavelet sub-bands. This design enables the network to capture horizontal, vertical and diagonal edges of adjacent berries more effectively than standard FPN-style fusion. In the second wavelet decomposition stage, MSFM further enlarges the receptive field in the low-frequency branch while retaining fine-grained high-frequency details, allowing large-scale cluster structure and local gaps to be modeled simultaneously.

where is the input feature map, LF denotes the low-frequency approximation component, and HL, LH, HH denote the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal high-frequency detail sub-bands, respectively.

Each high-frequency (HF) sub-band produced by the first-level wavelet decomposition is processed by a direction-sensitive convolution. Let denote the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal HF sub-bands, respectively. For the horizontal sub-band , a 1-D dilated convolution is applied along the horizontal direction; for the vertical sub-band , a 1-D dilated convolution is applied along the vertical direction; for the diagonal sub-band , a 3 × 3 convolution followed by a 1 × 1 convolution is used to enhance diagonal details. In index form, the direction-sensitive convolutions can be written as

where and index the spatial position, and are the -th weights of the horizontal and vertical convolution kernels, respectively, and is the dilation rate controlling the sampling stride along the corresponding direction.

The original HF sub-bands and the direction-enhanced HF sub-bands are then concatenated along the channel dimension and fused by a 3 × 3 convolution to obtain the first-level fused HF feature:

where represent the first-level HF sub-band feature maps (horizontal, vertical, diagonal directions), respectively, represent corresponding HF sub-bands after direction-sensitive convolution. , sets of original and enhanced HF sub-bands used for concatenation. fused HF feature from the first-level decomposition.

The low-frequency feature is further processed to capture larger-scale structures. First, a 3 × 3 convolution is applied, and then a second-level wavelet transform is performed:

where is the second-level low-frequency component and are the corresponding second-level HF sub-bands. The same direction-sensitive convolutions and fusion operations as in Equations (2)–(5) are applied to to obtain the second-level fused HF feature .

Finally, the multi-scale HF feature produced by the MSFM is obtained by summing the fused HF features from the two decomposition levels:

In summary, is a multi-scale, direction-aware HF representation that jointly encodes fine local details from the first-level decomposition and coarser structural information from the second-level decomposition.

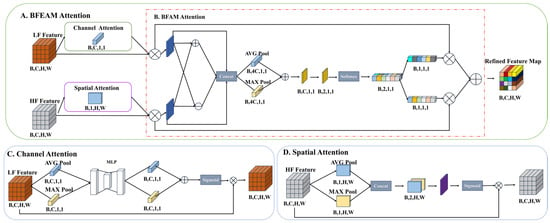

3.3.2. Bivariate Fusion Enhanced Attention Mechanism

Attention mechanisms such as SE and CBAM have been widely used to recalibrate feature responses by modeling channel-wise or spatial importance [38,39]. However, these modules usually process channel and spatial attention sequentially and then fuse them via simple addition or multiplication, without explicitly modeling the complementary and differential information between the two branches. In dense grape clusters, where subtle intensity differences at occlusion boundaries and small gaps are crucial cues for separating adjacent berries, such a naïve fusion can be sub-optimal. Inspired by recent bivariate fusion attention designs for SAR ship detection that leverage both the sum of and difference in multi-branch features to enhance discriminative details [28], we propose the BFEAM module tailored for grape instance segmentation. BFEAM first generates channel-refined and spatial-refined features, and then performs element-wise addition and subtraction between the two branches to explicitly capture their shared information and discrepancies. The concatenated feature is further compressed by global pooling and a lightweight two-layer 1 × 1 convolution, and a Softmax function is used to obtain normalized attention weights for each branch. In this way, the network can adaptively emphasize whichever branch provides more reliable cues for a given region, while maintaining a very small computational overhead.

The channel attention module highlights task-relevant features and suppresses redundant information by dynamically adjusting feature channel weights. The specific implementation method is as follows: the input feature maps are respectively subjected to global average pooling and maximum pooling of spatial dimensions to obtain the channel description vectors, which are then nonlinearly mapped by the shared multilayer perceptron (MLP), and finally normalized using the Sigmoid function to obtain the channel attention map S:

where denotes the nonlinear activation function, here the ReLU function is used, and is the Sigmoid function.

The feature map calibrated by channel attention can be expressed as

where × denotes channel-by-channel multiplication. The spatial attention module reinforces the important regions in the spatial feature maps through aggregation operations and local convolution operations in the spatial dimension. The specific implementation is as follows: the input feature maps are subjected to global average pooling and maximum pooling in the channel dimension, respectively, and subsequently the spatial attention maps are generated using 7 × 7 convolution with Sigmoid function:

where denotes the convolution operation, the feature map enhanced by spatial attention is

where the symbol is element-by-element multiplication.

By combining global pooling with local convolution, the spatial attention mechanism can effectively emphasize the spatial regions of the scene that contribute to the task, suppress background or irrelevant information, and thus enhance the network’s representational and discriminative capabilities.

In deep convolutional neural networks, features extracted from different branches or different levels often contain complementary information, and if they cannot be effectively fused and adaptively weighted, it may be difficult for the network to fully utilize the advantages of multi-scale features. In this paper, we design a Bivariate Fusion Attention Mechanism module as shown in the “BFEAM” block in Figure 5, which dynamically integrates multiple input features through the steps of difference, sum operation, global pooling, and Softmax attention allocation to improve the overall representation. integration, thus improving the overall characterization capability. In the proposed BFEAM, the feature map is first processed by two branches to obtain a channel-refined feature (CF) and a spatial-refined feature(SF). Intuitively, CF encodes what characteristics (channels) are important, whereas SF encodes where these characteristics are activated in the spatial domain. Instead of directly multiplying or simply adding these two maps as in conventional attention modules, we explicitly construct two fusion terms CF − SF() and CF + SF(), to model their relationships. The additive term highlights regions where both branches agree and respond strongly, thus capturing the consistent information between channel and spatial cues. In contrast, the subtractive term emphasizes regions where CF and SF differ, which correspond to complementary or conflicting information, for example, along object boundaries or partially occluded berries where spatial cues are strong but channel cues are ambiguous. By concatenating and feeding them into a lightweight 1 × 1 convolution and Softmax-based weighting, BFEAM learns to adaptively combine the common and complementary information from the two branches. These CF − SF and CF + SF operations are parameter-free, computationally cheap, and allow the network to exploit richer bivariate interactions than a single heuristic fusion, which leads to consistently better segmentation and counting performance in our experiments. The specific implementation process is as follows:

Figure 5.

Attention Mechanism Architecture Diagram. Part (A) is the general flow of the implementation of the attention mechanism, part (B) is the channel attention mechanism, part (C) is the spatial attention mechanism, and part (D) is the bivariate fusion augmented attention mechanism.

(1) Initial modulation of the input features using two convolutional layers with convolutional kernel 3 respectively, after which the convolutional operation can enhance the channel features in the local spatial range and align the baseline outputs of different branches, denoted as

(2) In order to explicitly capture the complementary and difference information between the two input features, pixel-by-pixel addition and subtraction are computed respectively, and finally the four feature maps are stitched together in the channel dimension, which is represented as follows:

(3) Perform global average pooling and global maximum pooling (denoted as GAP and GMP) on the splicing result , respectively, and sum the outputs of both to obtain the attention seed:

(4) is fed into two 1 × 1 convolutional layers for level-by-level extraction and dimensionality reduction. Finally, the attention weight vectors α and β are obtained through the Softmax function, which satisfies

where α + β = 1, α and β measure the relative importance of the input features CFeature and SFeature respectively in the fusion process.

(5) Finally, the two-way features are adaptively weighted and summed by the following form:

3.3.3. Network Task Heads

WGMG-Net employs a multi-head architecture to simultaneously output segmentation and counting results:

Instance Segmentation Head: Utilizes the standard FPN architecture to fuse multi-scale features, which are then fed into the instance segmentation head. This head performs bounding box regression, classification, and mask segmentation.

Instance Counting Head: To enable precise counting for the auxiliary network, a dedicated counting branch was designed. This branch performs global average pooling on the top-level feature maps (or fused feature maps) output by the FPN, compressing spatial information into channel statistics. Subsequently, this feature vector passes through two fully connected (FC) layers (using the ReLU activation function), ultimately mapping to a single output neuron. This neuron directly regresses the total number of all RoIs in the predicted image.

In addition to the proposed global regression branch, two natural alternatives for berry counting are (i) instance-counting directly from the detected masks (i.e., summing the number of predicted instances), and (ii) density-map-based counting, which predicts a continuous density map whose integral yields the final count. These strategies are widely used in object and crowd counting and provide reasonable baselines to disentangle the contribution of segmentation quality from that of the global regression design. A quantitative comparison of these three counting paradigms is presented in Section 4.3.

3.4. Morphological Compactness Classification

In Section 3.2, WGMG-Net provides high-precision instance segmentation masks. These masks are subsequently merged to generate a single binary mask representing the entire grape cluster. This mask is input into the morphological algorithm in Section 3.3 to classify its compactness. The algorithm (as shown in Figure 3) executes according to the following steps:

(1) Background Rejection: The input binary mask first employs a flood fill algorithm to eliminate external black background areas while preserving black holes within the target (white) region.

(2) Connectivity Analysis: The algorithm performs connectivity analysis on internal voids (black regions) to separate and label each distinct internal cavity.

(3) Gap Quantification: For each detected gap (connected region), compute the width w and height h of its axis-aligned bounding box.

(4) Thresholding and Counting: Set a threshold (50 × 50 pixels, based on the average area of the smallest berries in the dataset) to determine whether a gap constitutes a “significant gap.” If both the width (w) and height (h) of a gap exceed this threshold, it is considered a gap caused by one or more missing berries. Calculate the “missing factor C” represented by this gap by dividing its area by a baseline area (e.g., 2500).

(5) Classification: Accumulate all significant missing factors across all gaps to obtain the total count C_total. Based on the value of C_total, compactness is classified into three industrial grades: Type 1: C_total = 0. Indicates extremely dense fruit clusters with no significant particle loss. Type 2: 1 ≤ C_total ≤ 2. Indicates fruit clusters with minor particle loss (1–2 particles). Type 3: C_total ≥ 3. Indicates loose clusters with numerous missing particles.

3.5. Network Loss Function

The training of WGMG-Net is supervised by a composite loss function, which consists of two task-specific loss terms:

Mask Branching Loss: To balance pixel-level accuracy and overall shape overlap quality, the mask branch loss employs a weighted combination of binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss, Dice loss, and Lovász-Softmax loss, BCE focuses on pixel-wise classification, Dice complements it by emphasizing overlap on small objects, and Lovász-Softmax directly optimizes the IoU surrogate. As shown in Equations (20)–(24),

Instance Counting Loss: The training of the counting branch (defined in Section 3.3.3) is supervised by the root mean square error (RMSE) loss, which aims to minimize the discrepancy between the predicted count value and the actual instance count :

Total Loss (L_total): The total network loss L_total is the weighted sum of the two task losses mentioned above, used to jointly optimize segmentation and counting tasks during end-to-end training:

In this study, mAP [46] is adopted as the main evaluation metric for instance segmentation performance, where mAP is defined as the mean of the average accuracy of each category under different IoU thresholds, reflecting the overall accuracy of the model in the target localization and segmentation task. Meanwhile, in order to deeply evaluate the counts and target compactness after instance segmentation, we adopt the metrics of RMSE, MAE, MAPE, ACC, and Pearson r [47]. MAE measures the average deviation between predicted counts and true counts, while RMSE emphasizes the effect of larger errors; MAPE presents the relative error in percentage form, which making comparisons between scales more intuitive; count accuracy (e.g., Acc@1, Acc@2) indicates the proportion of predicted counts that are within the allowed tolerance, while Pearson r is used to measure the linear correlation between predicted and true counts. Taken together, these metrics can comprehensively quantify the performance of the model in terms of instance segmentation, counting, and compactness analysis, providing a strong quantitative basis for further optimization of the model.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Experimental Environment

The experimental platform uses a Lenovo LEGION REN9000K-34IRZ workstation equipped with an Intel® Core™ i7-14700KF processor, 32 GB of memory, an NVIDIA 4080 graphics card, and 10 TB of storage space. The operating system is Ubuntu 22.04. The development environment is based on PyCharm (2022.1.3) using Python 3.9, CUDA 12.1, and the PyTorch 2.1.0 deep learning framework.

4.1.2. Implementation Details

Our WGMG models follow a two-stage training scheme: the detector is first pretrained on COCO for 270 k iterations and then fine-tuned on our grape dataset for 10 k iterations. All experiments on our dataset use the same train/validation/test split, input resolution, and augmentation pipeline (random flip, rotation, Gaussian blur, and random contrast). For baseline methods, we start from the official COCO-pretrained weights and fine-tune them on our dataset using the same split and augmentation. Their optimization hyper-parameters (learning-rate schedule, batch size, total iterations) follow the recommended settings in the original implementations, which leads to slightly different effective training budgets across models.

To accommodate different deployment and research scenarios, we instantiate the proposed network at four scales, denoted WGMG-Net-n/s/m/l. Here, “n”, “s”, “m”, and “l” stand for nano, small, medium, and large, respectively, and indicate increasing model depth, width and computational cost. All four variants share the same macro-architecture, but differ in the number of channels and blocks in each stage. On the one hand, these scaled versions provide flexibility for practical deployment under different hardware constraints: WGMG-Net-n and WGMG-Net-s are suitable for edge devices and real-time grading systems with limited GPU resources, whereas WGMG-Net-m and WGMG-Net-l can be used on more powerful servers when higher accuracy is desired. On the other hand, designing a family of models with gradually increasing capacity makes the framework easier to adapt to future scenarios with more complex data, such as multi-variety, multi-batch and multi-environment grape datasets. In such cases, larger variants can better capture the increased variability, while smaller variants help avoid overfitting and enable fast prototyping on modest hardware. Table 1 lists the parameter settings for each version, while Table 2 shows the number of parameters and computational complexity for each version of the model.

Table 1.

For each model parameter setting, Stage denotes the number of residual structures used in each stage, and in and out denote the number of input feature channels and output feature channels, respectively. channels, in and out represent the number of input and output feature channels, respectively.

Table 2.

Comparison of Instance Segmentation Performance with State-of-the-Art Models. Bold type indicates the optimal result.

4.1.3. Training Settings

The model was trained using a batch size of 8. Each image was randomly cropped to the dimensions [224, 400, 128, 256, 512], with a maximum size of 512 and a minimum size of 128. During training, 270K pre-training iterations were first performed on the CoCo dataset, followed by 10K training iterations on the experimental data. The optimizer uses Adam with default settings. The initial learning rate is set to 2.5 × 10−4, with learning rate decay at 40% and 75% of training.

4.2. Analysis of Experimental Results

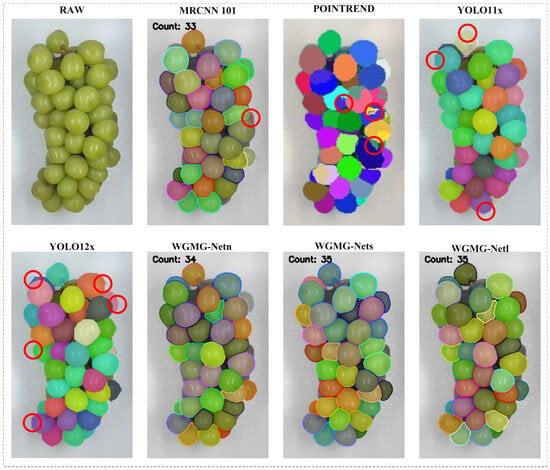

Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the WGMG-Net series with mainstream instance segmentation models, including Mask R-CNN, PointRend, and YOLOv11/v12. These metrics include mAP@50, mAP@75, and mAP@50:95, as well as model parameter scale (Param) and computational complexity (FLOPs), which jointly characterize accuracy and computational efficiency.

In the mAP@50 metric, the WGMG-Net (Ours) model proposed in this study performed outstandingly, achieving an accuracy of 98.98%, which is 0.17% and 0.46% higher than the classic MaskRCNN-ResNet50 (98.81%) and PointRend (98.52%), respectively. It is worth noting that the number of parameters in WGMG-Net is only 36.91 M, which is approximately 41.3% lower than the parameter size of MaskRCNN-ResNet101 (62.92 M). Although its computational complexity (FLOPs) has slightly increased (from 95.20 G to 116.38 G), it remains within a reasonable range.

In the more stringent evaluation metrics of mAP@75 and mAP@50:95, the WGMG-Net series also demonstrates outstanding performance. Specifically, WGMG-Nets achieves 97.88% on mAP@75 and 87.60% on mAP@50:95, significantly outperforming YOLOv12x (97.25% and 86.86%, respectively), striking a superior balance between model accuracy and computational efficiency. For example, compared to YOLOv12x, WGMG-Nets reduces its parameter count by approximately 28% (from 64.39 M down to 46.40 M) and its FLOPs by about 61.7% (from 324.6 G to 124.39 G), while still achieving higher segmentation accuracy.

A detailed analysis of the four variant models shows that WGMG-Netl, while maintaining a comparable mAP@50 (98.94–98.98%), attains the highest mAP@50:95 of 87.76%, making it the best overall performer. Although WGMG-Netl’s parameter size is 53.60 M—slightly above the base version—it remains below that of two-stage models such as Mask R-CNN with ResNet-101 (62.92 M) and YOLOv12x (64.39 M). Moreover, its computational cost is substantially lower than YOLOv12x (133.55 G vs. 324.6 G).

Compared with the strong detector baseline YOLOv12x, WGMG-Net achieves higher segmentation and counting accuracy while requiring substantially fewer parameters and FLOPs. This apparent paradox can be explained by the task-specific design of our network. First, YOLOv12x is a general-purpose object detector optimized for large-scale multi-class benchmarks, and its backbone and heads are configured to cope with diverse object sizes and aspect ratios. In contrast, WGMG-Net is tailored to dense grape clusters: the MSFM provides frequency-aware multi-scale features that preserve fine berry boundaries, and the BFEAM module explicitly enhances channel–spatial cues at occlusion regions, which are critical for accurate berry masks and counts but are not explicitly modeled in YOLO-style architectures. Second, our model is single-task and single-domain in terms of categories (only grape berries and clusters), so the representation capacity is fully devoted to this specific phenotype estimation problem instead of being diluted over many classes. Finally, the lightweight backbone and simplified prediction heads in WGMG-Net are co-designed with these modules to maintain the most informative features while aggressively reducing redundant channels. As a result, WGMG-Net delivers better accuracy than YOLOv12x on this targeted application, despite its significantly lower computational cost.

To further assess fine-grained segmentation performance in high-density scenes, Figure 6 presents a visual comparison on a single grape-cluster region among classic two-stage models (Mask R-CNN-ResNet101, PointRend), one-stage models (YOLOv11x, YOLOv12x), and our proposed WGMG series (WGMG-n, WGMG-s, WGMG-m, WGMG-x). The results clearly show that Mask R-CNN-ResNet101 suffers from blurred boundaries and instance adhesion, making it difficult to accurately delineate occluded regions; PointRend improves boundary precision but still exhibits misaligned edges and merged instances in dense, complex scenes; the YOLO series achieves better instance separation but falls short in boundary smoothness and mask conformity. In contrast, the WGMG series excels at boundary alignment, shape preservation, and instance differentiation, with WGMG-Netl in particular demonstrating strong structural awareness and boundary consistency.

Figure 6.

Comparison of segmentation effects of different instance segmentation methods on grape cluster images, where Detailed is the detail image. The detail graph shows the advantages and disadvantages of different network models, and the red circles in the graph show the problems occurring in the segmentation of different models.

To further validate the effectiveness of the BFEAM attention mechanism, this paper conducted detailed ablation experiments and compared the results with existing mainstream attention mechanisms. The experimental results are shown in Table 3. All attention mechanisms improved the model performance to varying degrees, but the BFEAM module proposed in this paper performed the best. The BFEAM module achieved the best overall performance, obtaining 98.94%, 97.84%, and 87.59% on mAP50, mAP75, and mAP50:95, respectively. Compared with CBAM, BFEAM yields consistently higher gains in overall mAP50:95 under a very similar parameter count and FLOPs. This advantage mainly comes from its bivariate fusion design: by jointly leveraging the sum and difference in channel-aware and spatial-aware features (CF + SF and CF − SF), BFEAM can better capture complementary cues in densely occluded regions, whereas CBAM only applies channel and spatial attention sequentially. Compared to traditional self-attention mechanisms, it not only improves performance but also significantly reduces computational overhead, making it more suitable for high-precision visual tasks.

Table 3.

Ablation Study of Different Attention Mechanisms on WGMG-Net, “/” indicates that no attention mechanism is used. Each attention mechanism is a replacement operation. Bold type indicates the optimal result.

Table 2 reports the performance of four WGMG-Net variants within the same batch, while Table 4 and Figure 7 summarizes batch transfer experiments—models trained on one batch of grape clusters and evaluated on another batch following the same imaging protocol but containing new clusters. Overall, segmentation accuracy under batch transfer remains very close to in-batch baselines. For WGMG-Net-n, mAP@50/75/50:95 from 98.94/97.84/87.59 (Table 2) decreased to 98.14/97.04/86.79 (Table 4), representing a maximum drop of 0.8 percentage points. The larger variant showed greater stability: WGMG-Net-l decreased marginally from 98.98/97.90/87.76 within batch to 98.88/97.84/87.71 across batches, with differences in all three mAP metrics below 0.1–0.2 percentage points.

Table 4.

Batch-to-batch transfer performance of the WGMG-Net variants. Models are trained on one batch of grape clusters and tested on a different batch collected under the same imaging configuration. “WGMG-Net-n/s/m/l” denote the nano, small, medium and large versions of the proposed network. mAP@50, mAP@75 and mAP@50:95 measure instance segmentation accuracy on the target batch, while RMSE(Count) reports the root-mean-square error of the berry-count regression head (lower is better). Bold type indicates the optimal result.

Figure 7.

Examples of grape-berry counting results on the simulated sorting line. Color masks indicate detected grape instances. The red text “Count: N(Δ)” denotes the predicted berry count, where the value in parentheses (Δ) is the difference between prediction and ground truth, and the purple text “TR: M” indicates the true count. Yellow arrows highlight local regions where occlusion or boundary ambiguity leads to small counting errors.

For the berry counting task, the root mean square error (RMSE) under batch transfer settings ranged from 1.96 berries (WGMG-Net-n) to 1.53 berries (WGMG-Net-l). This is only slightly higher than the intra-batch RMSE of 1.48 reported in Section 4.3 and remains well below the ±2 berries tolerance range typically accepted on processing lines. These results indicate that WGMG-Net does not exhibit severe overfitting to specific batches: it generalizes well to new clusters from other batches, with only minor degradation in segmentation and counting accuracy, and the extent of degradation depends on the model capacity. Figure 7 simultaneously displays the perfectly accurate and error images.

4.3. Ablation on Data Augmentation

To validate the effectiveness of the adopted data augmentation strategy, we conducted an ablation study on different combinations of data augmentation techniques (see Table 5 for details). Starting from a baseline model using only basic scaling, the detector achieved performance improvements over the baseline of 84.35 mAP@50:95. Introducing horizontal flipping alone boosted performance to 85.35 mAP. Adding random rotations at specified angles as defined in Section 3.1 further improved results to 85.65 mAP. Incorporating Gaussian blur reached 86.68 mAP, while the full augmentation pipeline combining geometric and photometric transformations ultimately achieved 87.59 mAP. These results demonstrate that both flipping and rotation augmentations are beneficial, with the selected rotation range effectively enriching viewpoint diversity while avoiding introducing unrealistic deformations in post-processing grape images.

Table 5.

Ablation study of different data augmentation strategies on validation mAP@50:95. “√” indicates that the corresponding augmentation is applied, “/” indicates that no augmentation is used, and “-” denotes that the operation is removed in the ablation setting. Bold type indicates the optimal result.

4.4. Phenotypic Analysis Results

As summarized in Table 6, all three approaches achieve high correlation with the ground-truth counts, but their accuracy efficiency trade-offs differ. MaskCount and the proposed WGMG-Regression attain identical overall accuracy, with an MAE of 1.10, an RMSE of 1.48, an MAPE of 2.82%, Acc@2 of 92.86%, and a Pearson correlation of 0.986. The DensityMap baseline is clearly worse across all metrics (MAE = 1.68, RMSE = 2.12, MAPE = 4.01%, Acc@2 = 90.12%, Pearson r = 0.951), indicating that, on this dataset, density-map modelling alone cannot fully compensate for local occlusions and appearance variability. In terms of computational cost, the global regression head is the most efficient, requiring only 0.5 ms per image, compared with 3 ms for MaskCount and 2.6 ms for DensityMap (measured for the counting stage given the same feature inputs). These results show that the strong segmentation quality of WGMG-Net already enables highly accurate instance-based counting, and the global regression head can match this best accuracy while significantly reducing the additional counting overhead. The observed gains in counting performance therefore stem primarily from improved segmentation, whereas the regression head mainly contributes to computational efficiency and integration convenience rather than further accuracy improvements on the current dataset.

Table 6.

Comparison of different counting strategies on the grape test set. “MaskCount” denotes direct instance counting from the detected masks, “DensityMap” denotes a density-map-based counting model, and “Ours” denotes the proposed global regression head. MAE, RMSE, MAPE, Acc@2 and Pearson-r measure counting accuracy, while time-consuming reports the average computation time per image for the counting stage (given the same backbone features).

To comprehensively assess the practical performance of the proposed method in phenotypic trait analysis, we conducted both quantitative and visual evaluations on two regression tasks—grape count prediction and compactness estimation—as illustrated in Figure 8. As summarized in Table 7, for the count prediction task our model achieved an MAE of 1.10%, an RMSE of 1.48%, and an MAPE of 2.82%, with a counting accuracy (Acc@2) of 92.86% and a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.986. In the compactness prediction task, although the MAPE was relatively high at 14.71% reflecting the small numerical range the model still demonstrated strong stability and accuracy, with Acc@1 and Acc@2 reaching 98.04% and 100%, respectively, and a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.844. These results further confirm the model’s reliability for phenotyping analysis.

Figure 8.

Plot of regression analysis and assessment with scatterplot of true and predicted values in the upper left corner, residual plot in the upper right corner, comparison of the distribution of true and predicted values in the lower left corner, and regression fit in the lower right corner.

Table 7.

Evaluation of phenotype.

4.5. Practical Deployment and Evaluation

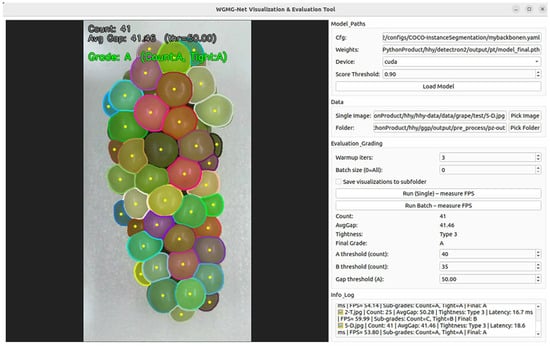

Beyond offline accuracy metrics, the key benchmark for industrial informatics systems is their actual performance in deployment-oriented scenarios. To validate the applicability of the WGMG-Net framework in real-world sorting tasks, this study developed an integrated visualization and grading evaluation tool (WGMG-Net Visualization & Evaluation Tool), as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Example of an instance segmentation and automatic grading visualization tool interface. The left side shows the segmentation results, count, density, and grade evaluation for a single grape cluster, while the right side shows the model configuration, data selection, inference parameters, and FPS testing function panel.

This software tool integrates the WGMG-Net-l model, providing operators with a real-time inference interface that automatically performs berry counting, average gap calculation, and final automated grading.

As shown in Table 8, all runtime measurements were obtained on an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU with an input resolution of 1024 × 1080 and FP32 inference. For the WGMG-Net-l model, single-frame inference (batch size = 1) achieves an average latency of 11.7 ms, corresponding to 53.8 FPS. In batch inference mode (batch size = [16]), the average latency is 26.8 ms per frame, i.e., 37.25 FPS. These values indicate that the model can satisfy real-time requirements for conveyor-based grading lines even under the more conservative batch-inference setting. Given the compact design of WGMG-Net, with only 36.91 M parameters and 116.38 GFLOPs per image (Table 2), the computation scales well to more typical industrial PCs equipped with mid-range GPUs. Assuming roughly one-third to one-half of the compute capability of an RTX 4080, the expected processing speed would still be in the range of about 20–30 FPS, which is sufficient for most conveyor-based grading lines. Even on CPU-only configurations, the lightweight architecture can sustain several frames per second, which is adequate for slower laboratory or sampling setups. These properties indicate that the proposed model is practically deployable beyond the high-end GPU used in our experiments.

Table 8.

Performance indicators and classification results.

5. Discussion

This study proposes an integrated two-stage pipeline designed to address the urgent need for real-time, accurate, and multidimensional phenotypic assessment of grapes in industrial automation sorting. Experimental results confirm that the framework achieves its design objectives in segmentation accuracy, reliability of phenotypic analysis, and real-time processing speed. This chapter will conduct an in-depth discussion of the results from three perspectives: methodological innovation, engineering design choices, and industrial deployment value.

5.1. Performance Advantages

Compared with mainstream approaches such as Mask R-CNN, PointRend, YOLOv11x, and YOLOv12x, WGMG-Net achieves superior segmentation accuracy, particularly under strict IoU thresholds. The integration of the Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Module (MSFM) with wavelet decomposition enables effective extraction of both structural and fine-grained features. Furthermore, the Bivariate Fusion Enhanced Attention Mechanism (BFEAM) adaptively reweights spatial and channel features, resulting in more precise delineation of occluded and densely packed berries. Ablation studies confirm that these modules contribute significantly to both accuracy and efficiency.

From a design perspective, MSFM and BFEAM are complementary: MSFM supplies frequency-aware multi-scale features with well-preserved edges, while BFEAM adaptively selects and reweights the most informative channel–spatial responses for each local region. This combination is particularly beneficial in our dense grape-cluster setting, where fine contour details and small inter-berry gaps must be resolved under strict real-time constraints.

Our results confirm that, even in a scenario where several strong segmentation baselines already perform well, non-trivial challenges remain for dense post-harvest grape clusters. First, grape berries are small, densely packed objects with severe mutual occlusions and only a few pixels separating adjacent instances. In such cases, even a small number of under- or over-segmentations can lead to large errors in downstream traits such as berry count and compactness. Second, commercial grading requires not only visually plausible masks but also stable instance statistics under varying varieties, batches and illumination conditions in industrial environments. However, conventional backbones and attention modules are usually optimized for object-level metrics rather than for fine-grained phenotypic measurements.

To address these issues, our model introduces two dedicated components. The MSFM provides frequency-aware multi-scale features that better preserve high-frequency edges at berry boundaries, while the BFEAM module adaptively emphasizes channel–spatial cues that are most informative for separating tightly occluded berries. In addition, the network is instantiated at four scales (n/s/m/l) to support deployment on devices with very different computational budgets while maintaining competitive accuracy. As demonstrated by the experiments in Section 4, this design yields more reliable berry-level segmentation and counting than existing segmentation baselines, particularly on dense clusters and challenging illumination conditions.

5.2. Practical Acceptance Criteria

From the perspective of an industrial processing line, the reported metrics are only meaningful if they satisfy practical acceptance criteria. For berry counting, line managers are primarily concerned with whether the predicted count leads to a wrong size/weight grade for a cluster or box. In typical commercial settings, grade boundaries differ by more than 10 berries per cluster, and operators tolerate small within-grade fluctuations. Under this regime, our results in Table 4 indicate that WGMG-Net meets a reasonable engineering target: an MAE of 1.10 and an RMSE of 1.48 berries, with Acc@2 = 92.86% and a Pearson correlation of 0.986, mean that in more than 90% of cases the prediction differs from the manual count by at most two berries—well below the margin that would change the assigned grade in routine operation. Thus, the residual counting error is unlikely to materially affect downstream sizing decisions on the processing line.

For compactness, the situation is more asymmetric. Misclassifying a loose cluster as compact leads to over-grading, which increases the risk that visually inferior fruit enters a premium grade, potentially reducing consumer satisfaction and harming brand value. The opposite error, classifying a compact cluster as loose, is economically conservative: it mainly causes a loss of revenue because some high-quality clusters are sold at a lower price tier, but it does not compromise perceived quality. Our compactness model achieves 98.04% Top-1 and 100% Top-2 accuracy with a correlation coefficient of 0.844 (Table 4). The very low Top-1 error rate (<2%) implies that only a small fraction of clusters are misgraded, and inspection of the confusion matrix shows that almost all mistakes occur between adjacent compactness levels rather than between the most compact and most loose classes. This behaviour is acceptable for the current prototype, because the resulting price difference between adjacent grades is moderate and can be absorbed by batch-level averaging. In future deployments, the decision threshold of the compactness classifier can be shifted to bias the system towards under-grading (reducing costly false positives) if a particular market segment places a higher premium on visual compactness.

5.3. Integrated Grading Capability

Unlike models limited to segmentation, WGMG-Net incorporates berry counting and compactness classification within an end-to-end pipeline. The counting module achieves an RMSE of 1.48 and MAPE of 2.82%, with a Pearson correlation of 0.986, while the compactness classification attains 98.04% Top-1 accuracy and 100% Top-2 accuracy. These metrics ensure consistent, objective, and reproducible grading standards, reducing reliance on manual inspection and minimizing operator variability.

From the perspective of commercial sorting lines, the reported counting and compactness metrics can be interpreted directly in terms of acceptance criteria and economic impact. In practice, table-grape grading rules are typically defined on relatively coarse count ranges (e.g., 25–30, 31–35 berries per cluster), and small deviations of ±1–2 berries do not change the assigned grade or consumer perception. In this context, our counting results (RMSE ≈ 1.5 berries and Acc@2 above 90%) imply that, for the vast majority of clusters, the system’s predictions fall within the operational tolerance window of the processing line. Only a small fraction of samples would be routed to a different count class due to prediction errors, so the impact on yield and throughput remains limited.

Compactness decisions are more directly linked to both product integrity and market value, because they determine whether a cluster is considered “too compact”, “moderately compact,” or “sufficiently loose” for premium packaging. In this setting, a false-positive compactness decision leads to conservative downgrading or rejection: the cluster may be diverted to a lower-grade channel or bulk packing, which reduces the unit price and increases rework, but it protects downstream quality. Conversely, a false-negative decision is more critical from a quality-control standpoint, because it allows high-risk clusters into premium packages, potentially increasing bruising, shortening shelf-life, and triggering consumer complaints. Given the high overall compactness accuracy, the expected rate of such high-cost false negatives is low. In practical implementation, the decision threshold for the compactness rule can be adjusted to favor a conservative strategy. This approach sacrifices a slight reduction in average selling price in exchange for a lower probability of problematic batch shipments and a more stable final market value for the product.

5.4. Industrial Applicability

The system’s average processing time of 26.8 ms per frame (~54.4 FPS) meets the requirements for conveyor-based grading lines without specialized high-end hardware. The grading software provides intuitive visual overlays and direct export of grading results, enabling seamless integration into existing production workflows. Its robustness to variations in berry size, orientation, and illumination enhances adaptability to different operational environments.

5.5. Scalability and Deployment Potential

Although optimized for Shine Muscat grapes, WGMG-Net can be retrained for other grape varieties or horticultural crops with minimal adaptation, provided annotated datasets are available. The balance between accuracy and computational efficiency positions the system for deployment not only in static grading lines but also on mobile platforms such as robotic harvesters.

5.6. Limitations and Future Work

In the present study, we restricted the phenotypic analysis to berry count and cluster compactness. These two traits were selected because they are directly related to cluster size and density, which are key factors in current commercial grading practice. Other important attributes such as color uniformity, freshness (e.g., shriveling or stem browning) and surface defects were not explicitly modeled in this work. This is mainly due to the lack of reliable reference labels for these quality dimensions at the single-berry level and the additional sensory or destructive measurements that would be required, which falls outside the scope of the current study. Nevertheless, the proposed instance segmentation and counting framework is inherently extensible: additional task heads can be attached to predict color or defect scores once appropriate annotated datasets become available. In future work, we plan to incorporate color and appearance-based indicators as well as defect detection into the framework to achieve a more comprehensive, commercially oriented grading system for post-harvest grapes.

From an industrial perspective, the current three-level rule based on the summed void area is a pragmatic 2D proxy for “missing berries”: when berries are absent due to shatter, disease, or poor packing, the cluster mask becomes more fragmented and the global void ratio increases, which aligns with how human inspectors penalize visibly loose or “holey” clusters. However, we acknowledge two important limitations of this design. First, the thresholds are defined on a normalized gap ratio and were tuned empirically on our dataset, without explicit calibration to the physical berry diameter or to the expected number of berries per unit area. As a consequence, clusters composed of smaller berries may be penalized differently from clusters with larger berries, even if the underlying missing pattern is similar. Second, the current rule uses a single global missing factor per cluster and thus does not model intra-cluster heterogeneity: it treats a cluster with one large gap and a cluster with many small, dispersed gaps as equivalent if their total void area is similar, and it does not differentiate whether gaps occur at the center or at the periphery of the cluster. In future work, we plan to refine this compactness descriptor in two directions. One is to calibrate the missing-factor thresholds to the estimated berry diameter or average berry area obtained from the instance masks, so that the categories are linked to physically meaningful “number of missing berries”. The other is to complement the global missing factor with heterogeneity-aware indices, such as local compactness maps, statistics of the spatial distribution of gaps (e.g., variance of local gap density), or graph-based measures derived from berry centers. These extensions would allow the compactness classification to better reflect both the scale and the spatial pattern of missing-berry defects that are relevant for industrial grading.

The current dataset was collected under controlled lighting with manual rotation of clusters. Future deployments in uncontrolled environments may require additional robustness enhancements, such as multi-view imaging systems and adaptive exposure control. Moreover, further model compression and lightweight architecture search could enable deployment on low-power embedded devices. Expanding the framework to include single-berry trait estimation (size, weight, sugar content) would create a more comprehensive grading standard aligned with market demands.

6. Conclusions

WGMG-Net achieves a balanced integration of accuracy, efficiency, and deployability in grape grading. In segmentation tasks, it achieves an mAP{50:95} of 87.76% and an mAP{75} of 97.88%, outperforming multiple baseline methods while achieving parameter and computational efficiency. For counting tasks, the system achieves an RMSE of 1.48, MAE of 1.10, and percentage MAE of 2.82%, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.986 compared to manual counting. In firmness classification, it attains a Top-1 accuracy of 98.04%, Top-2 accuracy of 100%, and a correlation coefficient of 0.844. Under current imaging configurations, the system achieves an inference speed of approximately 54.4 frames per second, meeting real-time requirements for conveyor belt grading lines. It has been integrated into visual grading software to enable real-time feedback and batch processing. However, the existing dataset exhibits limitations in diversity across varieties, orchards, and environmental conditions. Before claiming applicability to all industrial scenarios, large-scale multi-variety, multi-season validation and long-term robustness testing remain necessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and J.L.; Methodology, H.H., L.Z., Y.Y., X.Y. and J.L.; Software, H.H., L.Z. and J.L.; Validation, L.Z., X.Y. and J.L.; Formal analysis, H.H., L.Z., X.Y. and J.L.; Investigation, Y.Y., C.Y. and J.L.; Resources, C.Y., X.Y. and J.L.; Data curation, H.H., L.Z., C.Y., X.Y. and J.L.; Writing—original draft, H.H., L.Z., X.Y. and J.L.; Writing—review & editing, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation Ability Construction Project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Science (CZZJ202501), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2412103), and the BAAFS Foundation for Distinguished Scholars (JKZX202405).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| WGMG-Net | Wavelet-Guided Multi-Task Grape Network |

| MSFM | Multi-Scale Feature Fusion Module |

| BFEAM | Bivariate Fusion Enhanced Attention Mechanism |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| ACC | Accuracy |

| Pearson r | Pearson Correlation Coefficient |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| BCE | Binary Cross-Entropy Loss |

| Dice | Dice Loss |

| Lovász-Softmax | Lovász-Softmax Loss |

| mAP | mean Average Precision |

References

- Raheem, F.; Iqbal, N. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for the industrial internet of things (iiot). In Industrial Internet of Things; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Walas, F.; Redchuk, A. IIOT/IOT and Artificial Intelligence/machine learning as a process optimization driver under industry 4.0 model. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2021, 21, e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, S.Z. Introductory Chapter: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and New Trends in Quality Control. In Quality Control-Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and New Trends: Artificial Intelligence, Big Data, and New Trends; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Guo, L.; Xu, S.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J. High-throughput screening technology in industrial biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Lu, H. Research Progress on Methods for Improving the Stability of Non-Destructive Testing of Agricultural Product Quality. Foods 2024, 13, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Liang, X.; Lu, H. Application of nondestructive evaluation (NDE) technologies throughout cold chain logistics of seafood: Classification, innovations and research trends. LWT 2022, 158, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Feroze, M.A.; Malik, S.N.; Zulfiqar, B.; Rafique, R.; Shah, M.H.; Javed, A.; Asif, M.; Ahmad, S.; Ayub, C.M.; et al. Yield and quality assessment of grapevine cultivar sultnina at different geographic locations of Punjab, Pakistan. CABI 2022, 10, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Meneses, M.; Muñoz-Espinoza, C.; Reyes-Impellizzeri, S.; Salazar, E.; Meneses, C.; Herzog, K.; Hinrichsen, P. Characterization of Bunch Compactness in a Diverse Collection of Vitis vinifera L. Genotypes Enriched in Table Grape Cultivars Reveals New Candidate Genes Associated with Berry Number. Plants 2025, 14, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Yan, L.; Liu, S.; Gao, T.; Han, L.; Jiang, X.; Jin, H.; Zhu, Y. Agricultural Image Processing: Challenges, Advances, and Future Trends. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Peng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Cen, J.; Jiang, D.; Xie, L.; Yang, X.; Tian, Q. A survey on label-efficient deep image segmentation: Bridging the gap between weak supervision and dense prediction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 9284–9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Lin, G.; Xia, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y. Video object segmentation and tracking: A survey. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2020, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Chandel, N.S.; Singh, K.P.; Chakraborty, S.K.; Nandede, B.M.; Kumar, M.; Subeesh, A.; Upendar, K.; Salem, A.; Elbeltagi, A. Deep learning and computer vision in plant disease detection: A comprehensive review of techniques, models, and trends in precision agriculture. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakuri, J.P.; Nkundineza, C.; Gatera, O.; Nkurikiyeyezu, K. State-of-the-art deep learning algorithms for internet of things-based detection of crop pests and diseases: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 169824–169849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, N.; Niu, Y.; Yin, X.; Ding, Y.; Ge, X. Accurate segmentation of green fruit based on optimized mask RCNN application in complex orchard. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 955256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Hicks, Y.; Sun, X.; Luo, C. Peach ripeness classification based on a new one-stage instance segmentation model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 214, 108369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, H.; Vatta, S. Occlusion detection and handling: A review. Int. J. Comput. Appl. 2015, 120, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Rathod, V.; Sun, C.; Zhu, M.; Korattikara, A.; Fathi, A.; Fischer, I.; Wojna, Z.; Song, Y.; Guadarrama, S.; et al. Speed/accuracy trade-offs for modern convolutional object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillov, A.; Wu, Y.; He, K.; Girshick, R. Pointrend: Image segmentation as rendering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Xia, L.; Gutierrez, B.; Gagne, I.; Munoz, A.; Eribez, K.; Jagnandan, N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Waller, L.; et al. Low-latency label-free image-activated cell sorting using fast deep learning and AI inferencing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 220, 114865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurtsch, T.; Moryson, J.; Wiczyński, G. Machine vision-based detection of forbidden elements in the high-speed automatic scrap sorting line. Waste Manag. 2024, 189, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, W.; He, Z. Control Algorithms for Intelligent Agriculture: Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Processes 2025, 13, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Lomas, E.; Lado-Bega, J.; Garcia-Zamora, G.; Diaz-Garcia, L. Segment Anything for comprehensive analysis of grapevine cluster architecture and berry properties. Plant Phenomics 2024, 6, 0202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.J.; Schapke, S.-E. A distributed multi-model-based management information system for simulation and decision-making on construction projects. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2011, 25, 582–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, M.; Riomoros, I.; Pajares, G.; Zitinski, P. Discrete wavelets transform for improving greenness image segmentation in agricultural images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 118, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.D. Complex Wavelet Transforms and Their Applications. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Shi, J. HAF-YOLO: Dynamic Feature Aggregation Network for Object Detection in Remote-Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wan, Z.; Zhao, S.; Han, H.; Liu, Y. BFEA: A SAR ship detection model based on attention mechanism and multiscale feature fusion. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 11163–11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Yang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Gou, R.; Li, X. Semantic segmentation of agricultural images: A survey. Inf. Process. Agric. 2024, 11, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yang, Q.; Yang, L.; Shen, T.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Deep learning implementation of image segmentation in agricultural applications: A comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; Rodríguez, Í.; Rodríguez, N.; Usamentiaga, R.; García, D.F. Robot guidance using machine vision techniques in industrial environments: A comparative review. Sensors 2016, 16, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.S.; Lee, S. Low-complexity topological derivative-based segmentation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2014, 24, 734–741. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L.; Su, J.; Huang, R.; Quan, W.; Song, Y.; Fang, Y.; Su, B. Fusing attention mechanism with Mask R-CNN for instance segmentation of grape cluster in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 934450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]