Abstract

In order to determine the heat and humidity conditions of Igloo-type calf hutches, both in open space and under verandas, an analysis was conducted of the impact of the location of the veranda within the premises of the farm and its orientation in relation to the cardinal compass points and prevailing wind speed, as well as temperature and relative atmospheric humidity. The analysis was conducted based on constant measurement (temperature, relative humidity, air velocity) for climate conditions under the veranda and in the areas between the farm buildings. The 432,432 data points obtained in this way were used for further calculations and analysis of WCT (Wind Chill Temperature) and WCI (Wind Chill Index). Studies have shown that placing the hutch under a shelter allows for more favorable thermal and humidity conditions by reducing wind speed, and consequently increasing the apparent temperature and limiting the rate of heat loss. The analysis has demonstrated that the selection of the location of the hutch or calf enclosure is crucial for calf welfare. It is recommended that environmental studies be conducted individually for farms raising calves, especially dairy cattle breeds. An optimal location and utilisation of existing infrastructure will reduce the financial outlays for implementing new solutions. This analysis, conducted in Eastern Europe, also provides a basis for inferring the impact of climate change on local microclimatic conditions.

1. Introduction

A variety of calf-raising systems are practiced around the world, divided mainly into individual and group housing, in open, semi-open, and closed barns. The choice of raising system has a significant impact on the health and growth of the animal from the first days of its life onwards. A calf that experiences extreme high or low air temperatures is susceptible to cold or heat stress. Incorrect calf raising conditions may result in health problems and even delayed onset of first lactation for heifers [1], thus entailing losses in production, compromised health, welfare, and consequently, economic losses.

Calves are born without a fully functioning immune system, leaving them susceptible to pathogens that occur in their environment. They build up their immunity over several days, obtaining antibodies from the colostrum provided by the mother cows [2]. Holding the calves in calving houses or individual pens for the first four weeks of their life, as opposed to keeping them in barns, decreases the risk of coming into contact with pathogenic microorganisms that may cause diseases of the digestive and respiratory tracts [3,4]. This also limits their contact with disease-resistant adult cattle, which can act as vectors for the transfer of harmful microorganisms, e.g., Salmonella enterica.

When calves achieve a higher immunity to pathogenic agents, they should be brought together into small groups of two to six animals. This is a beneficial solution as calves are herd animals that more quickly learn new skills and behaviours when raised in conditions offering the opportunity for social contacts [5]. At the same time, such a group of animals is small enough to make the effective observation (or inspection) of each calf, individually, possible. Additionally, there are economic benefits to this arrangement; it allows work inputs related to caring for the animals to be reduced [6]. Among the advantages of this system, the fact that the calves have constant access to fresh air and that they build up resistance by being constantly outside are often mentioned. Hutches located outside, however, are highly susceptible to the impact of external factors such as extremely high or low air temperatures or other inclement weather conditions, which can not only negatively affect the health of the calf, but also make caring for the calves more difficult for the employees [4]. Hill et al. [7] also showed that calves raised in hutches had a lower weight gain than calves raised in traditional housing systems, such as barns, because they expend a greater amount of energy on thermoregulatory processes. It can also be stated that raising calves in the outdoors may result in delay of first lactation among heifers [8]. Before their first calving, heifers must attain an appropriate weight, something that is more difficult to achieve for calves who are held outdoors in the first months of their life [8].

The open system for raising calves is becoming increasingly popular in the temperate climate of Poland. Depending on the season, the air temperatures in calf hutches can sometimes be too high in the summer and too low in the winter compared to the thermoneutral air temperature range. This is why, due to the harsh frosts which occur in the winter, calf hutches are more and more often being placed under verandas, which protect them from some negative effects of air temperature and especially from wind.

The use of calf hutches is a relatively new solution, which is why the standards for the microclimate conditions that should be maintained in the hutches have not yet been developed. Based on the research conducted in scientific units in various countries around the world, guidelines for recommended air temperature, relative air humidity, and wind speed have been developed for calving houses, including in Poland. Kaczor et al. [4] gives the temperature range 8.0–25.0 °C as thermoneutral for calves. In addition, the air motion speed in traditional, closed calving houses should not exceed 0.2 m/s in winter or 0.3 m/s in summer, and they should be draft-free [4]. On the other hand, Majchrzak and Mazur [9] distinguished two separate periods in calf raising: one period for calves up to 3 months of age and a second for calves above 3 months of age. Their guidelines are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommended temperatures and relative humidity for calves according to Majchrzak and Mazur [9].

The values of air parameters determined by Majchrzak and Mazur [9] relate to the raising of beef cattle breeds. However, there are differences between the raising methods for beef cattle and dairy calves. Beef cattle calves remain with their mothers from birth to about six months after birth, drawing nutrients from her, while dairy cow calves are traditionally separated from their mothers immediately after birth and fed with milk replacements until they learn to take in solid feed [10].

Davis and Drackley [11] worked out minimum air temperatures for calves depending on their stage of life, and these are presented in Table 2. These values are confirmed by Litherland et al. [12].

Table 2.

Minimum air temperatures recommended for calves by Davis and Drackley [11].

The recommendations given by NASEM [13] also use the division of critical air temperatures in relation to the age of calves, i.e., for calves younger than 21 days of age, it is 15 °C, and for calves older than 21 days, it is 5 °C. The upper limit of the thermoneutral zone, regardless of the age of the calves, is 25 °C. Additionally, NASEM [13] has developed a computational model that allows us to determine how the type and amount of food intake affects the lower critical temperature of calves on individual days of life. For example, a seven-day-old calf with a milk intake of 4 L per day requires at least 17 °C, and with a milk intake of 10 L per day, it requires at least −1.6 °C.

Young [14] gives a lower critical temperature for a newborn dairy calf at 8 °C. They are also confirmed that when air temperature falls below the calf’s lower critical temperature, the calf needs more dietary energy to maintain body temperature [14].

Kaczor [4] states that cold stress among newborn calves begins to occur at temperatures below the lower air temperature. Cold stress entails a greater need for energy used for thermoregulation, and it may also interfere with the REM phase of sleep among calves [15]. Studies conducted in Norway indicated that calves born in the winter suffered from digestive tract illnesses more often than those born at other times of the year [16]. In order to reduce the risk of the occurrence of cold stress among calves, during periods of cold weather care should be taken to ensure that the calves’ coats are dry and that floor surfaces in hutches are covered with dry litter. Draughts should be avoided and heat loss minimised by the use of appropriate ventilation, while simultaneously not allowing for excessive humidity to build up [6]. Sonntag et al. [17] emphasise that the prevention of cold stress among calves is of crucial importance for their welfare, health, and biological functioning, which is confirmed by Fraser et al. [18] and Whalin et al. [19]. In order to obtain the highest gains in heat, the hutch can be situated with its entrance facing south or south-west [20]. It is beneficial for the calves if they are able to rest in-group and to have dry hay on the group pen floors to help calves maintain a suitable body temperature during the winter months [15]. Moreover, properly designed coverings for calf hutches can contribute to the improvement of the indoor environment, even in the winter, by reducing heat losses [21].

Summing up, by definition, calf hutches aid in creating an ideal microclimate for the animals, but nonetheless when they are situated outside, they expose the animals to extremes of air temperature, which may result in cold stress. For these reasons, the aim of this study was to determine the impact of local microclimate conditions on the creation of heat and humidity conditions in Igloo-type calf hutches in the winter season during periods of low temperatures.

2. Materials and Methods

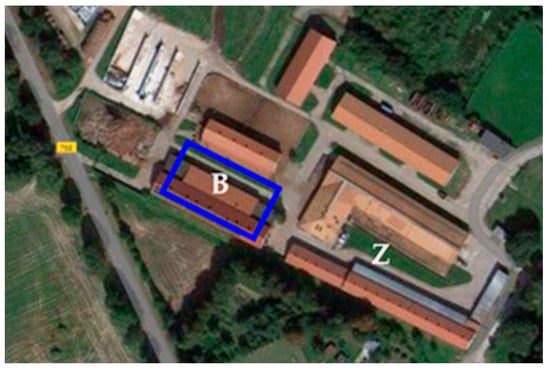

The study was conducted on a farm located in Lubcza (50°28′42″ N 20°20′14″ E) in southern Poland during the three months of the Polish astronomical winter (from 21 December 2018 to 21 March 2019). For the purposes of the study, single-occupancy hutches made of a synthetic material were used. Measurements were performed in empty hutches, without the presence of calves. Five hutches were located under a steel-frame veranda with dimensions of 12.0 × 42.0 × 4.5 m and a roof incline of 15% (marked with the letter B in Figure 1). The location of the veranda is illustrated in Figure 1. On the eastern and western sides, the veranda was adjacent to outbuildings while on the southern side it was adjacent to the cattle shed. Another five hutches were located in the space between buildings (in Figure 1 marked with the letter Z) in order to examine the conditions prevailing in hutches without wind cover.

Figure 1.

View of the farm where the study was conducted. The blue rectangle indicates the location of the veranda (www.google.com/maps 10 November 2025); B—location of hutches under the veranda; Z—location of hutches in the space between buildings.

Temperature and relative humidity monitors were placed in the upper parts of each of the study hutches. A wind speed monitor was placed near the entrance to each hutch. For both cases, further results consist of mean values from each five hutches.

Temperature and relative humidity as well as wind speed monitors were placed on a weather station mast between the farm buildings. Measurements were made every 10 min. The 432,432 data points obtained in this way were used for further calculations and analysis of WCT (Wind Chill Temperature) and WCI (Wind Chill Index) according to the formulas presented below:

- WCT according to the formula of Graunke et al. [22]

WCT = 13.12 + 0.6215·Tair − 13.17·V0.16 + 0.3965·Tair·V0.16

- WCT—wind chill temperature, °C

- Tair—air temperature, °C

- V—wind speed, km·h−1; air velocity, km·h−1

- WCI according to the formula of ASHRAE [23] (cited by Hoshiba [24])

WCI = 1.163·(10.45 + 10√V − V)·(33 − Tair)

- WCI—wind chill index, W·m−2

- Tair—air temperature, °C

- V—wind speed, m·s−1; air velocity, m·s−1

The results of the recorded and calculated parameters characterising heat and humidity conditions in the hutches were subjected to statistical analysis to determine basic descriptive statistics (mean, minimum, maximum, median, standard deviation). In order to test the relationship between selected parameters (air temperature, air velocity, relative air humidity, WCI, WCT), Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (r) were calculated in the Statistica program (Version 12.0, 2013). The Student’s t-test was used to estimate the statistical significance of the obtained values. Data were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

The winter season was varied in terms of the prevailing heat and humidity conditions. Periods when the daytime air temperature was above 0 °C with slight drops below 0 °C in the night were distinguishable as were periods when the air temperature was below 0 °C for the entire 24 h period (astronomical day). This variation persisted for single days or for periods of several days, and even for a dozen days or more. In total, 10 repeatable periods with air temperatures above 0 °C and 8 with temperatures below 0 °C were identified.

Preliminary analyses indicated that the air temperature inside the hutches located outdoors (Z) differed from the air temperatures recorded on the weather station mast by a maximum of 1 °C, which is why this difference is not illustrated in the graphs. The situation was similar with relative humidity; the differences between these measurements were in the range of 0.5 to 2% depending on the time of day.

Representative five-day periods were selected for analysis, one for the warmer periods (with daytime temperature above 0 °C and slight drops below 0 °C), which is further in this paper referred to as a cold period represented by the letter C, and another for colder winter days (with air temperatures below 0 °C for the entire 24 h period), further in this paper referred to as a frosty period represented by the letter F.

3.1. Cold Period

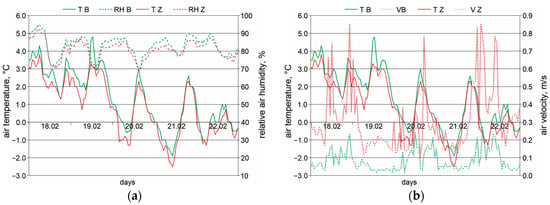

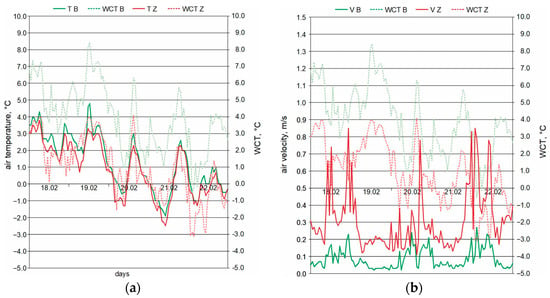

During the cold period, the external temperature sometimes fell below 0.0 °C, but never lower than −2.0 °C. The daily temperature amplitudes and daily humidity amplitudes were 7.7 °C and 23.3%, respectively (Figure 2a). The temperatures in the hutches under the veranda were higher than those in the hutches placed outside the veranda, a difference which was especially visible in the morning hours. The mean air temperature in both cases was higher than 0.0 °C, while the mean humidity exceeded 80% (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Variations in mean hourly air temperatures in the hutches under the veranda and in the space between the buildings for the cold period, in relation to (a) relative humidity and (b) air velocity.

Table 3.

Basic descriptive statistics for the parameters recorded and calculated characterising heat and humidity conditions in the hutches for the cold period.

Wind speeds under the veranda were lower compared to the measurements from outside the veranda (Figure 2b). The graphs indicate a similar course, but the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was only 0.488 (p < 0.05). Thus, it can be stated that the veranda reduced the speed of the airflow. When taking into consideration the north-eastern exposure of the veranda and the prevailing western winds [25], it can be seen that the cow shed building protected the hutches located under the veranda from strong wind speeds, which are common in Poland particularly in the winter.

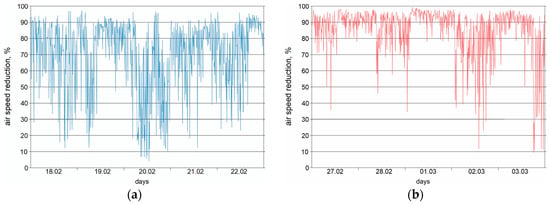

As it can be seen in Figure 3a, the reduction in external wind speed caused by the veranda was on average 70% (median 76.5%), contributing to a decrease in wind speed from 0.33 m/s to 0.31 m/s near the open-space hutches and to 0.06 m/s under the veranda.

Figure 3.

Percent reduction in external air velocity caused by the veranda (a) for the cold period; (b) for the frosty period.

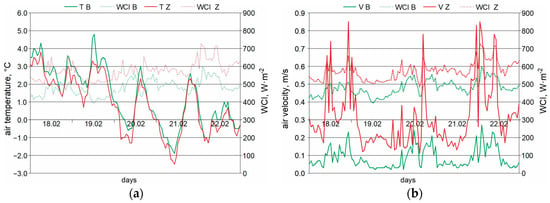

For the analysis of the impact of the veranda on heat and humidity conditions in the hutches, two indicators were used expressing the combined impact of the wind and temperature on the conditions as experienced by the calves.

The first of these is WCI, indicating the rate of heat loss expressed as W/m2. Calculations performed for the hutches under the veranda and for those in the open indicated that the chilling effect in the hutches under the veranda was, on average, 16.4% less (median 16.9%).

A comparison of the graphs showing WCI, air temperature, and wind speed identifies the impact these two parameters had on WCI. The course of the graphs of air temperature indicates specified daily changes with no visible outliers (Figure 4a) The variability of the wind speed graph is close to that of the WCI graph (Figure 4b). WCI does not change drastically, nonetheless all increases in values of WCI overlap with large increases in wind speed. The results shown in Table 4 indicate that the correlation between the wind speeds and WCI, both under the veranda and not under the veranda, was not greater than that between air temperature and WCI.

Figure 4.

Mean hourly WCI and (a) air temperatures; (b) air velocity, in the hutches under the veranda and not under the veranda for the cold period.

Table 4.

Values of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for the parameters analysed for the cold period *.

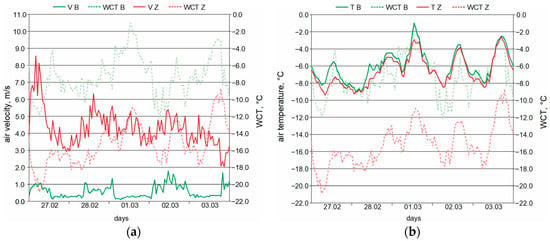

The second indicator used was WCT, which indicates the temperature as it is felt by the calves, expressed in degrees Celsius. Figure 5a shows the courses of both air temperature and WCT, suggesting similar courses. However, the impact of wind speed is visible (Figure 5b) at increases of wind speed above 0.1 m/s and the decrease in WCT was approx. 1.0–1.5 °C. For WCT, the correlations obtained confirm the greater impact of air temperature than wind speed (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Mean hourly WCT and (a) air temperatures; (b) air velocity, in the hutches under the veranda and not under the veranda for the cold period.

3.2. Frosty Period

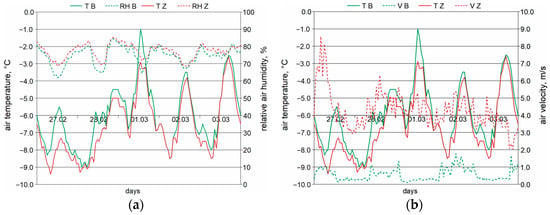

During periods of frost, the outside air temperature remained at a level below 0.0 °C for the entire 24 h period. Daily amplitudes of temperature and relative humidity were 7 °C and 19.5%, respectively (Figure 6a). The temperature in the hutches under the veranda was higher than in those not under the veranda; this difference was especially visible in the morning hours. The mean air temperature in both cases was lower than −6 °C, while the mean relative humidity exceeded 75% (Table 5).

Figure 6.

Variations in air parameters in the hutches under the veranda and in the space between the buildings for the frosty period, in relation to (a) relative humidity and (b) air velocity.

Table 5.

Basic descriptive statistics for the parameters recorded and calculated characterising heat and humidity conditions in the hutches for the frosty period.

Just as in the cold period, wind speed under the veranda was lower with respect to the measurements taken outside. The graphs (Figure 6b) show a similar course, but the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was only 0.15 (p < 0.05) (Table 6). Thus, it can be stated that the veranda reduced the speed of the airflow. When taking into consideration the north-eastern exposure of the veranda and the prevailing western winds [25], it can be seen that the cow shed building protected the hutches located under the veranda from harsh gusts.

Table 6.

Values of the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for the parameters analysed for the frosty period (gray marked p > 0.05).

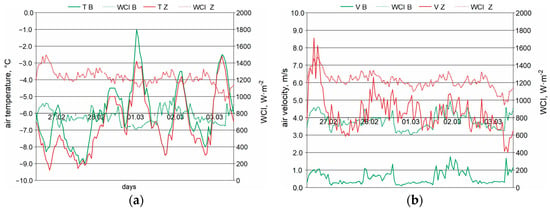

As can be seen in Figure 3b, the reduction in external wind speed caused by the veranda was on average 85.4% (median 90.5%).

A comparison of the graphs showing WCI, air temperature (Figure 7a), and wind speed (Figure 7b) shows specified daily changes with no visible outliers. The variability of the wind speed graph is close to that of the WCI graph. WCI does not change drastically, nonetheless all increases in values of WCI overlap with large increases in wind speed. The results of the correlations shown in Table 6 indicate that the correlation between the wind speeds and WCI, both under the veranda and not under the veranda, was greater than that between air temperature and WCI.

Figure 7.

Mean hourly WCI and (a) air temperatures; (b) air velocity, in the hutches under the veranda and not under the veranda for the frosty period.

Calculations of WCI performed for the hutches under the veranda and for those not under the veranda indicated that the chilling effect in the hutches under the veranda was less on average by 37.2% (median 39.4%).

The graph presents the courses of air temperature and WCT (Figure 8a), which are similar to one another. The impact of wind speed is visible (Figure 8b), yet with large increases in wind speed, the decrease in WCT was approx. 1.0–1.5 °C. For WCT, the correlations obtained confirm the greater impact of air temperature than wind speed (Table 6).

Figure 8.

Mean hourly WCT and (a) air temperatures; (b) air velocity, in the hutches under the veranda and in the space between the buildings for the frosty period.

Keeping calves in outside hutches is a global trend that is supported by the positive opinions of many cattle breeders. Approximately 38% of American dairy farms keep calves in separate exterior hutches [26]. However, in order to make a rational decision regarding the manner in which the calves are housed, it would be wise to pay particular attention to the local microclimate or, in broader terms, to the conditions prevailing in a given climate area. As Reuscher et al. [26] state, depending on the region where the calves are raised, they can be exposed to extreme environmental conditions, including the low air temperatures that occur in most of the United States from autumn to early spring, in which period calves are likely to experience some degree of cold stress.

A verification of academic publications devoted to the subject of raising calves in hutches indicated that a high degree of importance is placed on protecting the animals from heat stress and from the possibility of related negative consequences at further stages of growth, especially at the heifer stage. When it comes to cold stress, there are few studies and these are primarily devoted to nutritional issues, while supplying very terse suggestions regarding greater amounts of straw in hutches [27,28], calf blankets [29], or the use of dietary supplements in feed [30]. There is no information on what exactly a “greater amount of straw” means or in exactly which heat and humidity conditions one should begin to use calf blankets. This is why it is important to develop recommendations that are appropriate for local conditions in order to avoid threats to the calves’ welfare. After all, calves which experience significant fluctuations in temperature [31] or low temperatures in their surroundings have a higher risk of fatality [32], bovine illnesses of the respiratory tract [33], and reduced growth rates [34]. Additionally, calves exposed to cold stress require a greater feed intake due to the larger amount of energy they need to generate body heat [35].

As our study shows, analysis of local heat and humidity conditions can constitute the basis for determining the optimal place to locate hutches and other additional protective technical solutions such as verandas, radiant heaters, tree cover, etc.

Mean air temperatures in the cold period covered by the study were 1.29 °C in hutches under the veranda and 0.86 °C in hutches not under the veranda. In the frosty period, mean air temperatures were −6.09 °C in hutches under the veranda and −6.61 °C in hutches not under the veranda. Compared to all recommendations regarding temperature for calves, these values were too low. Davis and Drackley [11] recommend a temperature for calves in their first month of life above 6.1 °C. According to Reuscher et al. [26], the lower critical temperature for calves up to 8 weeks is approx. 8 to 10 °C, something which was also confirmed by Webster et al. [27] and Gebremedhin et al. [36]. NASEM [13], depending on the age of the calves, give 15 °C or 5 °C. Sonntag et al. [37] indicate that information on thermoneutral temperature ranges for calves is contradictory and exhibits significant differences depending on the age, weight, feed intake, and weather conditions experienced by the calves. The results of a study on outside hutches for calves in a continental climate conducted by Reuscher et al. [26] indicated that 100% and 96% of daily mean and maximum temperature of the surroundings measurements were noted, respectively, as ≤10 °C. For this reason, the calves were exposed to cold stress throughout the entire duration of the experiment, from December to March [26]. The results of our study, conducted in the temperate climate of Poland, confirm these observations.

Referring to the mean WCT, which means felt temperature, these differences for the cold period were 3.97 °C in hutches under the veranda and 0.97 °C in hutches not under the veranda. In the frosty period, mean WCT values were −7.32 °C in hutches under the veranda and −15.12 °C in hutches placed in space between buildings. The differences in the obtained mean WCT values for each period show that the conditions in the hutches between the buildings were very unfavorable for calves, regardless of the source used for comparison. Reference to the NASEM recommendations [13] allows for such low temperatures only for calves that are around 28 days old, with the highest quantity and quality of food provided. It is therefore recommended that, in addition to air temperature, metrics such as WCT be considered to broaden the scope of the analysis of calf welfare conditions.

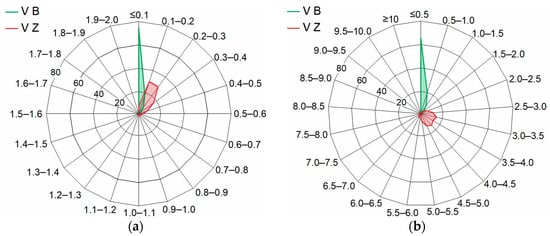

The measurements of wind speeds in the hutches under the veranda indicated that wind speed is too low with respect to the required values for calves, which Roland et al. [38] determined to be for cold periods at the level of 0.2 m/s. In the winter season, wind speeds were at levels as can be seen in Figure 9a. In hutches under a veranda, nearly 74% of the time, the wind speed was within a range below 0.1 m/s, which on the one hand does not lead to excessive chilling of the calves, but on the other hand does not guarantee adequate air exchange, which may present a danger for the calves. In turn, recommended values below 0.2 m/s were obtained in 91% of cases. In hutches not located under a veranda, wind speeds up to 0.2 m/s constituted 35.7% of the measurements, and the dominant role was played by wind speeds in the range of 0.1–0.3 m/s, constituting 57.8% of the measurements. These results are generally in line with the recommendations of Majchrzak and Mazur [9], who determined the optimal wind speed in the winter season as roughly 0.3 m/s.

Figure 9.

Percentage of air velocity in the ranges in the hutches under the veranda and in the space between the buildings (a) for the cold period; (b) for the frosty period.

In the frosty period, wind speed values up to 0.2 m/s in the hutches under the veranda constituted 18.3% of the results. The dominant role was played by wind speeds in the range of 0.2 m/s to 0.5 m/s, constituting 46.7% of the duration of the entire 5-day period in the frosty period (Figure 9b). In a study conducted by Lundborg et al. [39], wind speed above 0.5 m/s was considered to be a draught, which on winter days may exacerbate the chilling effect, particularly if the calf’s coat is wet or the litter is damp. The outcome of this study was the observation that calves in draughty enclosures were nearly four times more likely to exhibit moderate-to-severe amplified breathing sounds in comparison with calves in enclosures without draughts. In the hutches under the veranda that we studied, wind speeds exceeding 0.5 m/s constituted 35%, which, according to the results found by Lundborg et al. [39], pose a serious risk to the health of the calves.

In the hutches not under the veranda, wind speeds below 0.5 m/s constituted merely 0.3% (Figure 9b). One of the factors determined for the provision of comfortable conditions for calves is air exchange through ventilation. Moore et al. [40] give a value for air exchange by ventilation in the winter season at the level of approx. 17 m3/h per calf. However, when high wind speeds occur near hutches that are not shielded by another building or object, the air exchange through ventilation may be greater than recommended, while in the hutches under the veranda it may be difficult to ensure air exchange at the appropriate level. Solutions may be found in the form of an attempt to orientate the building with regard to cardinal compass points and prevailing winds in the region of the study or the provision of a veranda with perforated side walls in order to disperse the stream of airflow while simultaneously forcing air exchange in the hutch.

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- Meeting the recommended values of temperature, humidity, and air movement is particularly challenging in hutches located outdoors. Studies have shown that locating the hutch under a shelter allows for more favorable thermal and humidity conditions by reducing wind speed and consequently increasing the perceived temperature and limiting the rate of heat loss.

- 2.

- The authors are aware that this research should be continued with calves taking into account factors such as the heat released by the animals, behavioral observations, feed intake, and calf coat traits. However, the analysis presented here has already demonstrated that the selection of the location of the hutch or calf enclosure is crucial for calf welfare.

- 3.

- It is recommended that environmental studies be conducted individually for farms raising calves, especially dairy cattle breeds. An optimal location and utilisation of existing infrastructure will reduce the financial outlays for implementing new solutions.

- 4.

- This analysis, conducted in Eastern Europe, also provides a basis for inferring the impact of climate change on local microclimatic conditions. Both study periods presented challenges for calves due to unfavorable thermal and humidity conditions. However, the cold period is atypical for a regular February winter in Eastern Europe. Therefore, further monitoring of local climate changes is recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.A.; methodology, S.A.; software, S.A.; validation, S.A., formal analysis, S.A. and A.K.; investigation, S.A. and A.K.; resources, S.A.; data curation, S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and A.K.; visualisation, S.A.; supervision, S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Poland by statutory activity of the University of Agriculture in Krakow.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this research is available (upon valid request) from the corresponding author of this research article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TB | mean hourly air temperatures in hutches under the veranda |

| RHB | mean hourly relative air humidity in hutches under the veranda |

| TZ | mean hourly air temperatures in hutches outside the veranda |

| RHZ | mean hourly relative air humidity in hutches outside the veranda |

| VB | mean hourly air velocity in hutches under the veranda |

| VZ | mean hourly air velocity in hutches outside the veranda |

References

- Heinrichs, A.J.; Heinrichs, B.S.; Harel, O.; Rogers, G.W.; Place, N.T. A Prospective Study of Calf Factors Affecting Age, Body Size, and Body Condition Score at First Calving of Holstein Dairy Heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2828–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, P. (Warmińsko—Mazurski Ośrodek Doradztwa Rolniczego w Olsztynie, Olsztyn, Poland). Odchów Cieląt w Stadach Mlecznych. Personal communication, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert, L.; Moisa, S. Stress, immunity, and the management of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3199–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczor, A.; Kaczor, U.; Mandecki, A. The behaviour of calves in innovative rooms of open housing. Ann. UMCS. Sect. EE Zootech. 2016, 34, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stull, C.; Reynolds, J. Calf welfare. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2008, 24, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.A.; Duprau, J.L.; Wenz, J.R. Short communication: Effects of dairy calf hutch elevation on heat reduction, carbon dioxide concentration, air circulation, and respiratory rates. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 4050–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, T.M.; Bateman, H.G.; Aldrich, J.M.; Schlotterbeck, R.L. Comparisons of housing, bedding, and cooling options for dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 2138–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, A. Advantages and Disadvantages with Outdoor Hutches as Housing System for Calves and Their Future Effect on the Replacement Heifer. Bachelor’s Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Majchrzak, M.; Mazur, K. Analiza mikroklimatu w oborach dla bydła mięsnego w kontekście spełnienia wymagań dobrostanu zwierząt. Probl. Agric. Eng. 2012, 4, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Karanik, M. Prawidłowy odchów cieląt. Wieś Maz. 2014, 11, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.L.; Drackley, J.K. The Development, Nutrition, and Management of the Young Calf; University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Litherland, N.B.; Da Silva, D.; LaBerge, R.; Schefers, J.; Kertz, A. Supplemental fat for dairy calves during mild cold stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 2980–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASEM. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.A. Cold stress as it affects animal production. J. Anim. Sci. 1981, 52, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanninen, L.; Hepola, H.; Rushen, J.; Passille, A.M.; Pursiainen, P.; Tuure, V.M.; Syrjala Qvist, L.; Pyykkonen, M.; Saloniemi, H. Resting behaviour, growth and diarrhoea incidence rate of young dairy calves housed individually or in groups in warm or cold buildings. Anim. Sci. 2003, 53, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliksen, S.M.; Lie, K.I.; Løken, T.; Østerås, O. Calf mortality in Norwegian dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 2782–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonntag, N.; Sutter, F.; Borchardt, S.; Plenio, J.L.; Heuwieser, W. Temperature preferences of dairy calves for heated calf hutches during winter in a temperate climate. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 4005–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Weary, D.; Pajor, E.A.; Milligan, B.N. A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim. Welf. 1997, 6, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalin, L.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Preweaning dairy calves’ preferences for outdoor access. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 2521–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakony, M.; Kiss, G.; Kovács, L.; Jurkovich, V. The effect of hutch compass direction on primary heat stress responses in dairy calves in a continental region. Anim. Welf. 2021, 30, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kic, P. Influence of External Thermal Conditions on Temperature–Humidity Parameters of Indoor Air in a Czech Dairy Farm during the Summer. Animals 2022, 12, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graunke, K.L.; Schuster, T.; Lidfors, L.M. Influence of weather on the behaviour of outdoor-wintered beef cattle in Scandinavia. Livest. Sci. 2011, 136, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Physiological principles, comfort, and health. In ASHRAE Handbook 1981 Fundamentals; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1981; Chapter 8; p. 8.17. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiba, S. Environmental characteristics of calf hutches. J. Fac. Agric. 1986, 63, 64–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wołoszyn, E. Meteorologia i Klimatologia w Zarysie; Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdańsk, Poland, 2009; ISBN 978-83-7348-282-1. [Google Scholar]

- Reuscher, K.; Willits, A.; Jordan, E.; Jones, B. Calf hutch style effects on temperature humidity index and calf performance. J. Dairy Vet. Anim. Res. 2019, 8, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J. Environmental needs. In Calf Husbandry, Health and Welfare; Collins: London, UK, 1984; pp. 71–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, A.; McGuirk, S.M.; Bennett, T.B.; Cook, N.B.; Nordlund, K.V. Calf respiratory disease and pen microenvironments in naturally ventilated calf barns in winter. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4014–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoley, G.; Gordon, A.; Morrison, S.J. The effect of calf jacket usage on performance, behaviour and physiological responses of group-housed dairy calves. Animal 2019, 13, 2876–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermorel, M.; Vernet, J.; Saido Dardillat, C.; Demigne, C.; Davicco, M.-J. Energy metabolism and thermoregulation in the newborn calf; effect of calving conditions. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1989, 69, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnyder, P.; Schönecker, L.; Schüpbach-Regula, G.; Meylan, M. Effects of management practices, animal transport and barn climate on animal health and antimicrobial use in Swiss veal calf operations. Prev. Vet. Med. 2019, 167, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, R.M.; Green, M.J.; Sherwin, V.E.; Hudson, C.; Gibbons, J.; Forshaw, T.; Vickers, M.; Down, P.M. Quantitative analysis of calf mortality in Great Britain. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 2615–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.F.; Chancellor, N.; Wathes, D.C. A cohort study risk factor analysis for endemic disease in pre-weaned dairy heifer calves. Animals 2021, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.J.; Robertson, J.; Macrae, A.I.; Jennings, A.; Mason, C.S.; Haskell, M.J. The effect of the climatic housing environment on the growth of dairy-bred calves in the first month of life on a Scottish farm. Animals 2021, 11, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnecke, B.J.; Foote, M.R.; Miller, B.L.; Fowler, M.; Johnson, T.E.; Horst, R.L. Effects of chronic environmental cold on growth, health, and select metabolic and immunologic responses of preruminant calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 6134–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremedhin, K.G.; Cramer, C.O.; Porter, W.P. Predictions and measurements of heat production and food and water requirements of Holstein calves in different environments. Trans. Am. Soc. Agric. Eng. 1981, 24, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, N.; Borchardt, S.; Heuwieser, W.; Sutter, F. Association between a pyroelectric infrared sensor monitoring system and a 3-dimensional accelerometer to assess movement in preweaning dairy calves. JDS Commun. 2024, 5, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, L.; Drillich, M.; Klein-Jöbstl, D.; Iwersen, M. Influence of climatic conditions on the development, performance, and health of calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2438–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundborg, G.K.; Svensson, E.C.; Oltenacu, P.A. Herd-level risk factors for infectious diseases in Swedish dairy calves aged 0–90 days. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 68, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.; Heaton, K.; Poisson, S.; Sischo, W.M. Effects of Hutch or Pen Environment on Pre-Weaned Calf Health, Welfare, and Performance. Veterinary Medicine Extension, Washington State University, Pullman. 2011. Available online: http://extension.wsu.edu/vetextension/calfscience/Documents/CalfEnv4-EnvironmentEffects.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.