Functional Diversity in Trichoderma from Low-Anthropogenic Peruvian Soils Reveals Distinct Antagonistic Strategies Enhancing the Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material

2.2. Soil Sample Collection and Site Characterization

2.3. Trichoderma Isolation and Morphological Identification

2.4. Dual Culture Confrontation Assays

2.5. Mycoparasitism Assessment Using the Adapted Bell Scale

2.6. Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Inhibition Test

2.7. Endophytic Colonization Capacity

2.8. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification of Trichoderma Isolates

2.9. Sequence Analysis and Phylogenetic Identification

2.10. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Isolation and Preliminary Characterization of Trichoderma Strains

3.2. Dual Assay Analysis

3.3. Mycoparasitism Evaluation

3.4. Fungal Growth Response to Volatile Organic Compounds

3.5. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Diversity

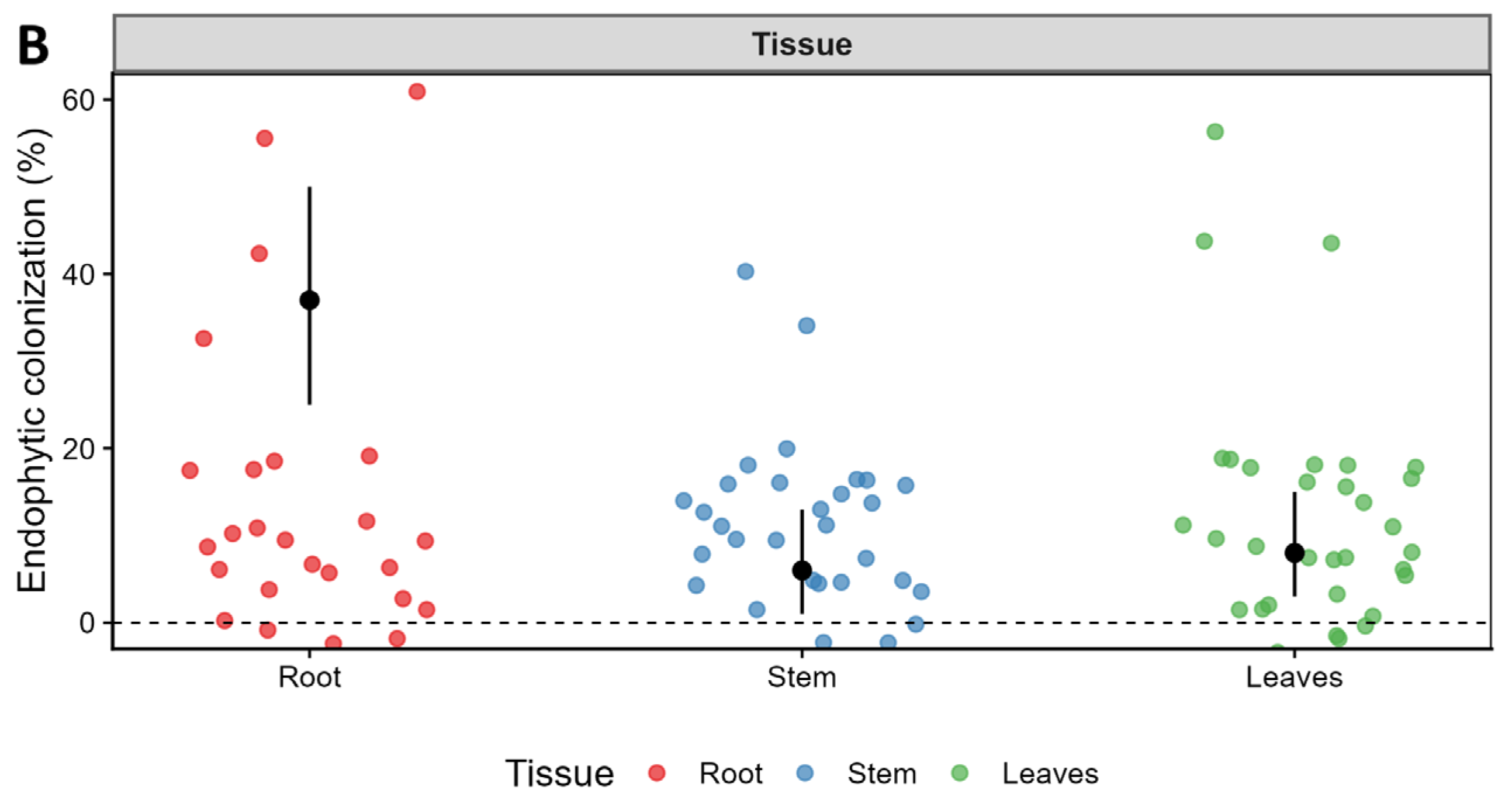

3.6. Endophytic Colonization Levels in Capsicum baccatum

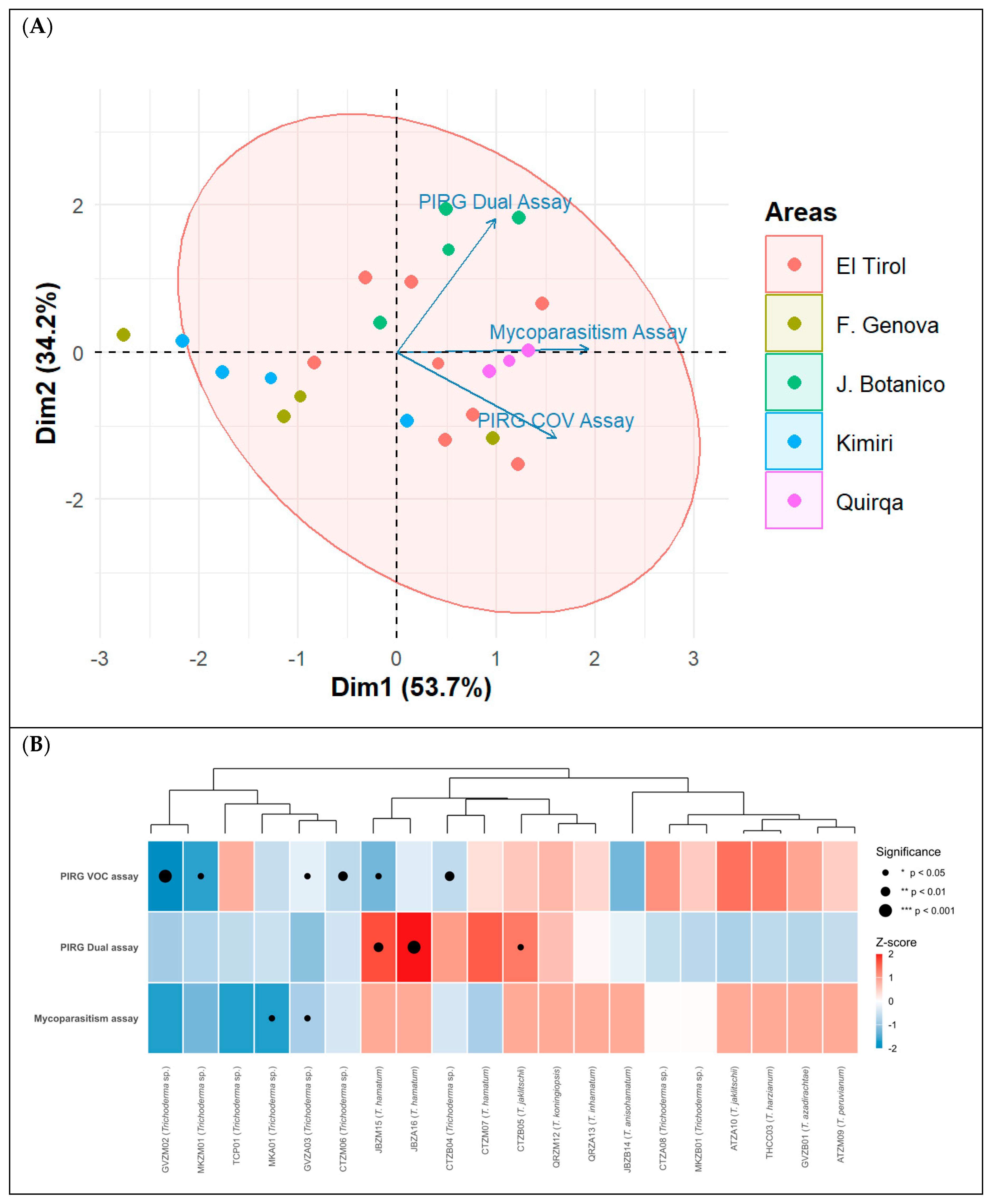

3.7. Multivariate Analysis of Antagonistic Activity of Trichoderma spp. Against Botrytis cinerea

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PIRG | Percentage Inhibition of Radial Growth |

| VOC | Volatile Organic Compound |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacer |

| TEF1α | Translation Elongation Factor 1-alpha |

| RPB2-RNA | Polymerase II second-largest subunit |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| SE | Standard Error |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

References

- Elad, Y.; Pertot, I.; Cotes Prado, A.M.; Stewart, A. Plant Hosts of Botrytis spp. In Botrytis—The Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 413–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Couso, R.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Rivas, R. Mechanisms of Action of Microbial Biocontrol Agents against Botrytis cinerea. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbey, J.A.; Percival, D.; Abbey, L.; Asiedu, S.K.; Prithiviraj, B.; Schilder, A. Biofungicides as Alternative to Synthetic Fungicide Control of Grey Mould (Botrytis cinerea)—Prospects and Challenges. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2019, 29, 241–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Hakimi, Y. Integrated Management of Grape Gray Mold Disease Agent Botrytis cinerea In Vitro and Post-Harvest. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2023, 65, 1955–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, A.; Carpentier, F.; Duplaix, C.; Auger, A.; Pradier, J.M.; Viaud, M.; Gladieux, P.; Walker, A.S. The Polyphagous Plant Pathogenic Fungus Botrytis cinerea Encompasses Host-Specialized and Generalist Populations. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 4808–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyśkiewicz, R.; Nowak, A.; Ozimek, E.; Jaroszuk-ściseł, J. Trichoderma: The Current Status of Its Application in Agriculture for the Biocontrol of Fungal Phytopathogens and Stimulation of Plant Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.L.; Hermosa, R.; Lorito, M.; Monte, E. Trichoderma: A Multipurpose, Plant-Beneficial Microorganism for Eco-Sustainable Agriculture. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez-Lázaro, A.A.; Vázquez-Medina, P.J.; Caro-Degollar, E.M.; García Evangelista, J.V.; Cortez-Lázaro, R.A.; Rojas-Paz, J.L.; Legua-Cardenas, J.A.; Fernandez-Herrera, F.; Pesantes-Rojas, C.R.; Ocrospoma-Dueñas, R.W.; et al. Global Trends in Trichoderma Secondary Metabolites in Sustainable Agricultural Bioprotection. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1595946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Brito, V.; Lana Alves, J.; Sírio Araújo, K.; de Souza Leite, T.; Borges de Queiroz, C.; Liparini Pereira, O.; de Queiroz, M.V. Endophytic Trichoderma Species from Rubber Trees Native to the Brazilian Amazon, Including Four New Species. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1095199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, C.M.F.; De Cremer, K.; Cammue, B.P.A.; De Coninck, B. The toolbox of Trichoderma spp. in the biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea disease. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawati, A.F.C.; Mutaqin, K.H.; Suhartono, M.T.; Widodo, W. The Effect of Application of Endophytic Fungus Trichoderma spp. and Fusarium spp. to Control Bacterial Wilt in Chilli Pepper. Walailak J. Sci. Technol. (WJST) 2020, 17, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M. The Competitive Potential of Different Trichoderma spp. to Control Rhizoctonia Root Rot Disease of Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Egypt. J. Phytopathol. 2021, 49, 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Ashfaq, M.; Rao, M.J.; Khan, K.S.; Malik, A.H.; Mehmood, M.A.; Fawaz, M.S.; Abbas, A.; Shakeel, M.T.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; et al. Trichoderma viride: An Eco-Friendly Biocontrol Solution Against Soil-Borne Pathogens in Vegetables Under Different Soil Conditions. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, A.; Aragón, L.; Casas, A. Space-Time Analysis, Severity of the Wilt Disease in Escabeche Pepper (Capsicum baccatum var. pendulum) and Identification of the Causal Agent (Phytophthora capsici L.) under Subtropical Climate Conditions in Peru. Sci. Agropecu. 2024, 15, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zijll de Jong, E.; Kandula, J.; Rostás, M.; Kandula, D.; Hampton, J.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A. Fungistatic Activity Mediated by Volatile Organic Compounds Is Isolate-Dependent in Trichoderma sp. “Atroviride B”. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcante, A.L.A.; Negreiros, A.M.P.; Melo, N.J.d.A.; Santos, F.J.Q.; Soares Silva, C.S.A.; Pinto, P.S.L.; Khan, S.; Sales, I.M.M.; Sales Júnior, R. Adaptability and Sensitivity of Trichoderma spp. Isolates to Environmental Factors and Fungicides. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismaiel, A.; Lakshman, D.K.; Jambhulkar, P.P.; Roberts, D.P. Trichoderma: Population Structure and Genetic Diversity of Species with High Potential for Biocontrol and Biofertilizer Applications. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhulkar, P.P.; Singh, B.; Raja, M.; Ismaiel, A.; Lakshman, D.K.; Tomar, M.; Sharma, P. Genetic Diversity and Antagonistic Properties of Trichoderma Strains from the Crop Rhizospheres in Southern Rajasthan, India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Tomer, A.; Prasad, D.; Viswanath, H.S.; Singh, R.; Tomer, A.; Prasad, D. Biodiversity of Trichoderma Species in Different Agro-Ecological Habitats. In Trichoderma: Agricultural Applications and Beyond; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Miramontes, J.P.; Olmedo-Monfil, V.; Lara-Banda, M.; Zúñiga-Romo, E.R.; Aréchiga-Carvajal, E.T. Promotion of Plant Growth in Arid Zones by Selected Trichoderma spp. Strains with Adaptation Plasticity to Alkaline PH. Biology 2022, 11, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S.; Roy, M.; Sharma, P.K.; Srivastava, A.K. Exploring Trichoderma Diversity in the Western Ghats of India: Phylogenetic Analysis, Metabolomics Insights and Biocontrol Efficacy against Maydis Leaf Blight Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1493272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnaswami, K.; Mishra, D.; Miriyala, A.; Vellaichamy, P.; Kurubar, B.; Gompa, J.; Madamsetty, S.P.; Raman, M.S. Native Isolates of Trichoderma as Bio-Suppressants against Sheath Blight and Stem Rot Pathogens of Rice. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2021, 31, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Delgado, R.; Brito-López, P.; Jaizme Vega, M.C.; Laich, F. Biodiversity of Trichoderma Species of Healthy and Fusarium Wilt-Infected Banana Rhizosphere Soils in Tenerife (Canary Islands, Spain). Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1376602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreyra, G.; Judith, N. Antagonismo In Vitro de Trichoderma spp. Frente a Botrytis sp. y Fusarium sp., Aislados de Fragaria ananassa “Fresa”. Ayacucho—2022. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional San Cristobal de Huamanga, Ayacucho, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura Grandez, R. Respuesta de Trichoderma harzianum Rafai. en la Prevención de Botrytis cinerea Pers. en el Cultivo de Fresa (Fragaria sp.), Cuelcho, Chachapoyas—2018. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodriguez de Mendoza de Amazonas, Chachapoyas, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 1–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, H.L.; Hunter, B.B. Illustrated Genera of Imperfect Fungi; Burgess Publishing Company: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Ricaldi Guadalupe, R. Acción Antagónica In Vitro de Trichoderma harzianum Rifai. Sobre el Crecimiento de Botrytis cinerea Pers F. en Cultivo de Fragaria vesca L. “Fresa” Procedente del Caserío de Quirihuac—Distrito de Laredo, Provincia de Trujillo. Bachelor’s Thesis, National University of Trujillo, Trujillo, Peru, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.K.; Wells, H.D.; Markham, C.R. In Vitro Antagonism of Trichoderma Species against Six Fungal Plant Pathogens. Phytopathology 1982, 72, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intana, W.; Kheawleng, S.; Sunpapao, A. Trichoderma asperellum T76-14 Released Volatile Organic Compounds against Postharvest Fruit Rot in Muskmelons (Cucumis melo) Caused by Fusarium incarnatum. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra-Bucarei, L.; Iglesias, A.F.; González, M.G.; Aguayo, G.S.; Carrasco-Fernández, J.; Castro, J.F.; Campos, J.O. Antifungal Activity of Beauveria bassiana Endophyte against Botrytis cinerea in Two Solanaceae Crops. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. A Guide Methods Appl. 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A Method for Designing Primer Sets for Speciation Studies in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic Relationships among Ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA Polymerse II Subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Druzhinina, I.S.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M.; Monte, E.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Zeilinger, S.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Kubicek, C.P. Trichoderma: The Genomics of Opportunistic Success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castresana, J. Selection of Conserved Blocks from Multiple Alignments for Their Use in Phylogenetic Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000, 17, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Põlme, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Yorou, N.S.; Wijesundera, R.; Ruiz, L.V.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Suija, A.; et al. Global Diversity and Geography of Soil Fungi. Science 2014, 346, 1256688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, C.; Moya-Ambrosio, F.; Barja, A.; Ottos-Diaz, E.; Aguilar-Tito, C.; Advíncula-Zeballos, O.; Cruz-Luis, J.; Solórzano-Acosta, R. Soil Quality Variation Associated with Land Cover in the Peruvian Jungle of the Junín Region. Soil Secur. 2025, 19, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Lupwayi, N.; Marc, S.A.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Bainard, L.D. Anthropogenic Drivers of Soil Microbial Communities and Impacts on Soil Biological Functions in Agroecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 27, e01521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, S.; Rubio, K.; Díaz-Valderrama, J.R.; Granda-Santos, M.; Mattos, L. Phylogenetic Affinity in the Potential Antagonism of Trichoderma spp. against Moniliophthora roreri. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyos-Carvajal, L.; Orduz, S.; Bissett, J. Genetic and Metabolic Biodiversity of Trichoderma from Colombia and Adjacent Neotropic Regions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peixoto, G.H.S.; da Silva, R.A.F.; Zacaroni, A.B.; Silva, T.F.; Chaverri, P.; Pinho, D.B.; de Mello, S.C.M. Trichoderma Collection from Brazilian Soil Reveals a New Species: T. cerradensis sp. nov. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1279142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Quintero, C.A.; Atanasova, L.; Franco-Molano, A.E.; Gams, W.; Komon-Zelazowska, M.; Theelen, B.; Müller, W.H.; Boekhout, T.; Druzhinina, I. DNA Barcoding Survey of Trichoderma Diversity in Soil and Litter of the Colombian Lowland Amazonian Rainforest Reveals Trichoderma strigosellum sp. nov. and Other Species. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2013, 104, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.L.; Chen, J.; Mao, L.J.; Feng, X.X.; Zhang, C.L.; Lin, F.C. Trichoderma Biodiversity of Agricultural Fields in East China Reveals a Gradient Distribution of Species. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczyk, L.; Popiel, D.; Chełkowski, J.; Koczyk, G.; Samuels, G.J.; Sobieralski, K.; Siwulski, M. Species Diversity of Trichoderma in Poland. J. Appl. Genet. 2011, 52, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Ras, E.; Ferguson, K.B.; Ariëns, S.; Babendreier, D.; Bijma, P.; Bourtzis, K.; Brodeur, J.; Bruins, M.A.; Centurión, A.; et al. Next-Generation Biological Control: The Need for Integrating Genetics and Genomics. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 1838–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, S.; Oliva, M.; Hernández, E.; Chuquibala, B.; Rubio, K.; García, F.; de la Cruz, M.T. Assessment of the Potential of Trichoderma spp. Strains Native to Bagua (Amazonas, Peru) in the Biocontrol of Frosty Pod Rot (Moniliophthora roreri). Agronomy 2020, 10, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, T.A.; Shrestha, H.K.; Gopalakrishnan Meena, M.; Spangler, M.K.; Ellis, J.C.; Labbé, J.L.; Abraham, P.E. Bioprospecting Trichoderma: A Systematic Roadmap to Screen Genomes and Natural Products for Biocontrol Applications. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 716511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.-R.; Senanayake, I.C.; Liu, J.-W.; Chen, W.-J.; Dong, Z.-Y.; Luo, M. Trichoderma azadirachtae sp. nov. from Rhizosphere Soil of Azadirachta indica from Guangdong Province, China. Phytotaxa 2024, 670, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, D.E.; Calderon, M.S.; Leiva, S.; Mendoza, J.E.; Arce, M.; Oliva, M. Three New Species of Trichoderma in the Harzianum and Longibrachiatum Lineages from Peruvian Cacao Crop Soils Based on an Integrative Approach. Mycologia 2021, 113, 1056–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa-Lomba, N.; González-García, V.; Venturini-Crespo, M.E.; Casanova-Gascón, J.; Barriuso-Vargas, J.J.; Martín-Ramos, P. Comparison of the Efficacy of Trichoderma and Bacillus Strains and Commercial Biocontrol Products against Grapevine Botryosphaeria Dieback Pathogens. Agronomy 2023, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, X.; Kuramae, E.E. Insight into Farming Native Microbiome by Bioinoculant in Soil-Plant System. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 285, 127776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onufrak, A.J.; Gazis, R.; Gwinn, K.; Klingeman, W.; Khodaei, S.; Perez Oñate, L.I.; Finnell, A.; Givens, S.; Chen, C.; Holdridge, D.R.; et al. Potential Biological Control Agents of Geosmithia morbida Restrict Fungal Pathogen Growth via Mycoparasitism and Antibiosis. BioControl 2024, 69, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkom, Y.; Yildiz, A. Evaluation of Biocontrol Potential of Native Trichoderma Isolates against Charcoal Rot of Strawberry. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 104, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Razdan, V.K. Potential of Trichoderma Species as Biocontrol Agents of Soil Borne Fungal Propagules. J. Phytol. 2010, 2, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Huh, N.; Hong, J.H.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, G.-H.; Kim, J.-J. The Antagonistic Properties of Trichoderma spp. Inhabiting Woods for Potential Biological Control of Wood-Damaging Fungi. Holzforsch. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Phys. Technol. Wood 2012, 66, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Daly, P.; Anjago, W.M.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhou, D.; Deng, S.; Lin, X.; Voglmeir, J.; et al. Genus-Wide Analysis of Trichoderma Antagonism toward Pythium and Globisporangium Plant Pathogens and the Contribution of Cellulases to the Antagonism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0068124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Shi, H.; Zhang, Z.; Bai, C. Antifungal Effects of Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Trichoderma hamatum against Neocosmospora solani. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 77, ovae063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinale, F.; Sivasithamparam, K. Beneficial effects of Trichoderma secondary metabolites on crops. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.J.; Dodd, S.; Lu, B.S.; Petrini, O.; Schroers, H.J.; Druzhinina, I.S. The Trichoderma koningii Aggregate Species. Stud. Mycol. 2006, 56, 67–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Lang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Chen, J. Designing Synthetic Consortia of Trichoderma Strains That Improve Antagonistic Activities against Pathogens and Cucumber Seedling Growth. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. Trichoderma and Its Role in Biological Control of Plant Fungal and Nematode Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1160551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; López-Bucio, J. The 4-Phosphopantetheinyl Transferase of Trichoderma virens Plays a Role in Plant Protection against Botrytis cinerea through Volatile Organic Compound Emission. Plant Soil 2014, 379, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Hyder, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma Species: Our Best Fungal Allies in the Biocontrol of Plant Diseases—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Avilés, M.N.; García-Álvarez, M.; Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Hernández-Hernández, I.; Bautista-Ortega, P.I.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.I. Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Trichoderma asperellum with Antifungal Properties against Colletotrichum acutatum. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Lu, Y.; Li, B.; Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Bai, R.; Wu, Q.; Fan, Q.; Tang, J.-H.; et al. Biocontrol Activity and Antifungal Mechanisms of Volatile Organic Compounds Produced by Trichoderma asperellum XY101 against Pear Valsa Canker. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 4742–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Esquivel-Naranjo, E.U.; Soth, S.; Whelan, H.; Alizadeh, H.; Echaide-Aquino, J.F.; Kandula, D.; Hampton, J.G. Uncovering the Multifaceted Properties of 6-Pentyl-Alpha-Pyrone for Control of Plant Pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1420068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.H.; Hussein, K.A. Biological Control and Plant Growth Promotion Properties of Volatile Organic Compound-Producing Antagonistic Trichoderma spp. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 897668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Li, G.; Li, C.; Zhu, L.; Yang, H.; Song, R.; Gu, W. Biological Control and Plant Growth Promotion by Volatile Organic Compounds of Trichoderma koningiopsis T-51. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Jud, W.; Weikl, F.; Ghirardo, A.; Junker, R.R.; Polle, A.; Benz, J.P.; Pritsch, K.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Rosenkranz, M. Volatile Organic Compound Patterns Predict Fungal Trophic Mode and Lifestyle. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stange, P.; Kersting, J.; Sivaprakasam Padmanaban, P.B.; Schnitzler, J.P.; Rosenkranz, M.; Karl, T.; Benz, J.P. The Decision for or against Mycoparasitic Attack by Trichoderma spp. Is Taken Already at a Distance in a Prey-Specific Manner and Benefits Plant-Beneficial Interactions. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Z.; Sederoff, R.R.; Sederoff, H.; Chiang, V.L.; Borriss, R. Microbial Interactions Within Multiple-Strain Biological Control Agents Impact Soil-Borne Plant Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kredics, L.; Büchner, R.; Balázs, D.; Allaga, H.; Kedves, O.; Racić, G.; Varga, A.; Nagy, V.D.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Sipos, G. Recent Advances in the Use of Trichoderma-Containing Multicomponent Microbial Inoculants for Pathogen Control and Plant Growth Promotion. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrocco, S.; Esteban, P.; Vicente, I.; Bernardi, R.; Plainchamp, T.; Domenichini, S.; Puntoni, G.; Baroncelli, R.; Vannacci, G.; Dufresne, M. Straw Competition and Wheat Root Endophytism of Trichoderma gamsii T6085 as Useful Traits in the Biological Control of Fusarium Head Blight. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.; Roberts, D.P.; Lim, H.-S.; Strem, M.D.; Park, S.-C.; Ryu, C.-M.; Melnick, R.L.; Bailey, B.A. Endophytic Trichoderma Isolates from Tropical Environments Delay Disease Onset and Induce Resistance Against Phytophthora capsici in Hot Pepper Using Multiple Mechanisms. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011, 24, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, N.; Shams Alizadeh, H.; Bazgir, E.; Darvishnia, M.; Mirzaei Najaofghli, H. The Tripartite Consortium of Serendipita indica, Trichoderma simmonsii, and Bell Pepper (Capsicum annum). Biol. Control 2021, 158, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, R.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Ren, W.; Wei, D.; Ye, W. Biocontrol Potential of Trichoderma asperellum CMT10 against Strawberry Root Rot Disease. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E. Integrated Benefits to Agriculture with Trichoderma and Other Endophytic or Root-Associated Microbes. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.A.A.; Najeeb, S.; Hussain, S.; Xie, B.; Li, Y. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites from Trichoderma spp. against Phytopathogenic Fungi. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Rouina, H.; Groten, K.; Rajani, P.; Furch, A.C.U.; Reichelt, M.; Baldwin, I.T.; Nataraja, K.N.; Uma Shaanker, R.; Oelmüller, R. An Endophytic Trichoderma Strain Promotes Growth of Its Hosts and Defends Against Pathogen Attack. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 573670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lücking, R.; Aime, M.C.; Robbertse, B.; Miller, A.N.; Aoki, T.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Cardinali, G.; Crous, P.W.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Geiser, D.M.; et al. Fungal taxonomy and sequence-based nomenclature. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Hossain, D.M.; Rahman, M.M.E.; Suzuki, K.; Narisawa, T.; Hossain, I.; Meah, M.B.; Nonaka, M.; Harada, N. Native Trichoderma Strains Isolated from Bangladesh with Broad Spectrum Antifungal Action against Fungal Phytopathogens. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2016, 49, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain Code | Collection Site | Elevation Zone | Altitude (m a.s.l.) | Geographic Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GVZB01 | Fundo Génova | Low | 895 | 11°05′50.8″ S 75°20′43.0″ W |

| GVZM02 | Fundo Génova | Medium | 950 | 11°05′48.5″ S 75°20′45.9″ W |

| GVZA03 | Fundo Génova | High | 1000 | 11°05′46.0″ S 75°20′49.3″ W |

| CTZB04 | Catarata El Tirol | Low | 1011 | 11°08′15.0″ S 75°19′54.0″ W |

| CTZB05 | Catarata El Tirol | Low | 1013 | 11°08′15.0″ S 75°19′54.0″ W |

| CTZM06 | Catarata El Tirol | Medium | 1021 | 11°08′14.0″ S 75°19′54.0″ W |

| CTZM07 | Catarata El Tirol | Medium | 1023 | 11°08′14.0″ S 75°19′54.0″ W |

| CTZA08 | Catarata El Tirol | High | 1032 | 11°08′13.0″ S 75°19′54.0″ W |

| ATZM09 | El Tirol | Medium | 1034 | 11°08′16.0″ S 75°19′52.0″ W |

| ATZA10 | El Tirol | High | 1036 | 11°08′16.0″ S 75°19′52.0″ W |

| QRZM12 | Quirca | Medium | 952 | 11°02′23.9″ S 75°19′43.0″ W |

| QRZA13 | Quirca | High | 839 | 11°02′22.5″ S 75°19′46.0″ W |

| JBZB14 | Botanical Garden | Low | 689 | 10°56′35.7″ S 75°17′27.5″ W |

| JBZM15 | Botanical Garden | Medium | 692 | 10°56′37.0″ S 75°17′25.9″ W |

| JBZA16 | Botanical Garden | High | 698 | 10°56′37.0″ S 75°17′28.8″ W |

| MKA01 | Monte Kimiri | High | 1150 | 11°02′34.5″ S 75°17′56.2″ W |

| MKM01 | Monte Kimiri | Medium | 1003 | 11°02′30.2″ S 75°18′20.9″ W |

| MKB01 | Monte Kimiri | Low | 980 | 11°02′27.8″ S 75°18′33.3″ W |

| TCP01 | Lunahuaná | Low | 485 | 12°55′05.7″ S 76°06′03.5″ W |

| THCC03 | Commercial strain | Control | N/A | N/A |

| Strain Code | Taxonomic Identification | Dual Assay PIRG | Mycoparasitism Assay | VOCs Assay PIRG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Strain vs. THCCC03 | Mean ± SD | Strain vs. THCCC03 | Mean ± SD | Strain vs. THCCC03 | ||

| GVZB01 | Trichoderma azadirachtae | 31.2 ± 2.6 fh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 59.6 ± 11.1 ab | ns (p > 0.9999) |

| GVZM02 | Trichoderma sp. | 29.3 ± 1.5 gh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 70 ± 35 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 32.1 ± 5.7 e | *** (p = 0.0005) |

| GVZA03 | Trichoderma sp. | 27.1 ± 1.3 h | ns (p = 0.9958) | 80 ± 0 a | ns (p = 0.1576) | 48.6 ± 2.1 bcd | ns (p = 0.3215) |

| CTZB04 | Trichoderma sp. | 49.0 ± 16.9 ab | * (p = 0.022) | 85 ± 30 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 45.1 ± 2.9 ce | ns (p = 0.1188) |

| CTZB05 | Trichoderma jaklitschii | 52.7 ± 11.2 acd | ** (p = 0.0028) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 56.3 ± 1.8 ac | ns (p = 0.9829) |

| CTZM06 | Trichoderma sp. | 33.9 ± 9.1 bh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 85 ± 30 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 45.0 ± 5.7 ce | ns (p = 0.1134) |

| CTZM07 | Trichoderma hamatum | 55.2 ± 17.2 acde | *** (p = 0.0005) | 80 ± 28 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 54.1 ± 4.8 ac | ns (p = 0.8714) |

| CTZA08 | Trichoderma sp. | 32.5 ± 3.5 bdh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 90 ± 20 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 61.4 ± 5.3 ab | ns (p > 0.9999) |

| ATZM09 | Trichoderma peruvianum | 32.4 ± 3.2 bdh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 55.8 ± 16.7 ac | ns (p = 0.9702) |

| ATZA10 | Trichoderma jaklitschii | 30.1 ± 4.0 gh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 64.2 ± 14.2 a | ns (p > 0.9999) |

| QRZM12 | Trichoderma koningiopsis | 45.5 ± 11.6 ab | ns (p = 0.996) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 57.9 ± 1.3 ac | ns (p = 0.9989) |

| QRZA13 | Trichoderma inhamatum | 39.4 ± 1.1 abf | ns (p = 0.7857) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 54.9 ± 1.0 ac | ns (p = 0.9261) |

| JBZB14 | Trichoderma anisohamatum | 36.3 ± 2.8 abfg | ns (p = 0.996) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 39.3 ± 18.6 de | * (p > 0.0136) |

| JBZM15 | Trichoderma hamatum | 56.4 ± 3.5 ac | *** (p = 0.0002) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 39.2 ± 10.5 de | * (p > 0.0131) |

| JBZA16 | Trichoderma hamatum | 61.6 ± 3.9 a | **** (p < 0.0001) | 100 ± 0 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 48.0 ± 12.6 bcd | ns (p > 0.2755) |

| MKA01 | Trichoderma sp. | 33.0 ± 2.2 bch | ns (p > 0.9999) | 70 ± 12 a | ns (p = 0.0584) | 45.7 ± 12.9 ce | ns (p = 0.1425) |

| MKZM01 | Trichoderma sp. | 30.8 ± 4.2 gh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 75 ± 25 a | ns (p = 0.4836) | 35.7 ± 15.7 de | ** (p = 0.0028) |

| MKZB01 | Trichoderma sp. | 31.6 ± 2.1 bh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 90 ± 12 a | ns (p > 0.9999) | 55.9 ± 3.9 ac | ns (p = 0.9718) |

| TCP01 | Trichoderma sp. | 32.1 ± 4.4 bh | ns (p > 0.9999) | 70 ± 20 a | ns (p = 0.0722) | 58.7 ± 9.1 ac | ns (p = 0.9999) |

| THCC03 | Trichoderma harzianum | 31.8 ± 6.3 beh | _ | 100 ± 0 a | _ | 63.3 ± 6. 7 a | _ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rojas-Villa, N.; Ormeño-Vásquez, P.; Pedrozo, P.; Oré-Asto, B.; Moriano-Camposano, J.; Álvarez, L.A. Functional Diversity in Trichoderma from Low-Anthropogenic Peruvian Soils Reveals Distinct Antagonistic Strategies Enhancing the Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Agriculture 2026, 16, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010112

Rojas-Villa N, Ormeño-Vásquez P, Pedrozo P, Oré-Asto B, Moriano-Camposano J, Álvarez LA. Functional Diversity in Trichoderma from Low-Anthropogenic Peruvian Soils Reveals Distinct Antagonistic Strategies Enhancing the Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Villa, Naysha, Phillip Ormeño-Vásquez, Paula Pedrozo, Betza Oré-Asto, Jherimy Moriano-Camposano, and Luis A. Álvarez. 2026. "Functional Diversity in Trichoderma from Low-Anthropogenic Peruvian Soils Reveals Distinct Antagonistic Strategies Enhancing the Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010112

APA StyleRojas-Villa, N., Ormeño-Vásquez, P., Pedrozo, P., Oré-Asto, B., Moriano-Camposano, J., & Álvarez, L. A. (2026). Functional Diversity in Trichoderma from Low-Anthropogenic Peruvian Soils Reveals Distinct Antagonistic Strategies Enhancing the Biocontrol of Botrytis cinerea. Agriculture, 16(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010112