Abstract

To address the challenges of inefficient Camellia oleifera fruits harvesting in hilly and mountainous regions due to the difficulty of using large machinery, a handheld vibration harvesting device for Camellia oleifera fruits was designed. Based on the vibration-induced detachment process of Camellia oleifera fruits, a single-pendulum dynamic model of the “fruit-branch” system was established and solved to calculate the tangential acceleration required for fruit detachment. The key factors influencing harvesting efficiency were identified as vibration frequency, amplitude, height, and duration. Using ANSYS, modal response and harmonic response analyses were conducted on a 3D model of the Camellia oleifera tree to determine the operational parameters ensuring branch acceleration meets the fruit detachment. Furthermore, a rigid-flexible coupling simulation system integrating the harvesting device and Camellia oleifera tree was developed on the ADAMS. This analysis revealed the variation patterns of branch acceleration with respect to vibration frequency and clamping height, thereby validating the rationality of the dynamic model and the feasibility of the device. Finally, an orthogonal experiment was designed using Design-Expert 13, and multi-objective optimization analysis was performed on the device’s working parameters based on the experimental data. The aforementioned research identified the optimal working parameter combination and actual harvesting performance of the handheld vibration harvesting device: when the vibration frequency is 14 Hz, vibration height is 980 mm, and vibration duration is 13 s, the fruit picking rate reaches 95.22%. The harvesting efficiency of this device is significantly higher than manual picking methods, fully meeting the requirements for efficient Camellia oleifera fruit harvesting.

1. Introduction

In China, Guangxi is one of the provinces with the largest Camellia oleifera (henceforth CO) planting areas. Located in the subtropical zone and characterized by hilly terrain, Guangxi benefits from a favorable climate, abundant water resources, and a superior ecological environment, making the CO industry an important component of the regional economy. A wide variety of CO are grown in Guangxi, including ‘Cenruan’ CO, ‘Xiaoguo’ CO, ‘Guangning’ CO, and ‘Xianghua’ CO, among others [1]. CO is rich in natural vitamins and trace elements beneficial to human health, and it has been reported to help lower blood lipids, regulate blood sugar, resist aging, and improve skin health [2]. However, most CO plantations are located in hilly and mountainous areas, where manual management is limited, the growing environment is complex, and row spacing is narrow. These factors result in limited operational space for agricultural machinery, and the challenging field conditions impose stringent requirements on the mechanization of CO harvesting. With the development of the CO industry, there is an urgent need for mechanized harvesting. Currently, CO harvesting faces significant challenges, including difficulties in accessing orchards, low harvesting efficiency, and high labor intensity [3,4]. Therefore, it is crucial for the development of the CO industry to conduct research on the harvesting mechanism of ‘Xianghua’ CO and design suitable harvesting devices in the text.

At present, academic exploration into the vibration harvesting mechanism of CO and its corresponding harvesting equipment remains insufficient, with relatively limited systematic research. Due to its unique growth characteristics, relevant studies on the vibration harvesting of other forest and fruit crops can serve as valuable references [5,6,7]. Liu et al. constructed a multi-degree-of-freedom vibration model derived from the morphological features of goji berry stems and berries. In their investigation, they evaluated how excitation position, vibration frequency, force magnitude, and phase angle affected the rates of fruit separation, impurity incorporation, and mechanical damage. Based on these findings, they determined an optimal set of operating conditions, which delivered a fruit harvesting efficiency of 97.58%, an impurity proportion of 5.12%, and a breakage ratio of 7.66% [8]. Bu et al. established a finite element model of the apple branch–stem–fruit system for the purpose of predicting the fracture process occurring in branches and stems when exposed to various loads. Results from the experiments showed tangential loading outperformed other methods in fruit detachment, offering a robust finite element model useful for apple harvest tasks [9]. Zhou et al. applied dynamic finite element models together with modal analysis to assess vibration responses in jujube branches, precisely mimicking fruit loss under multifaceted circumstances. [10]. Du et al. created a portable harvester incorporating adjustable comb fingers, and via ADAMS simulation and field evaluations obtained 80% efficiency at 480 rpm while keeping floral debris to a minimum [11]. Lyu et al. looked into the transmission clearance parameters of a blueberry harvester, derived an optimized setup from force and load studies, and proved its effectiveness in field tests [12]. Hu et al. advanced a low-expense three-dimensional reconstruction methodology for building digital models of jujube trees, and through the integration of finite element analysis and vibration testing they characterized the vibration response properties, delineated an advantageous range of vibration variables, thereby furnishing a valuable reference for the engineering of jujube harvesting machinery [13]. Cao et al. established a local vibration model to analyze the dynamic behaviors of stems and stem-fruit systems under different vibration modes, deriving fruit detachment ratios under various vibration parameters. Their findings offer guidance for the design of vibration-based harvesting devices [14]. Yu et al. created a handheld vibrating coffee harvester and studied how fruit detachment varied with operating parameters. Results showed maximum performance at 62 Hz, 9 mm amplitude, and 0.4 m excitation location, giving mature-coffee harvest rates of 92.22%, immature rates of 8.33%, and a damage rate of 5.23% [15]. Zhang et al. explored the forces on olive fruits, ran vibration tests and simulations on olive trees, and built a quadratic polynomial regression model to predict the best vibration frequency and force, providing a reference for vibration harvester design [16]. S. Castro-García et al. explored how varying vibration parameters like frequency, duration, and vibration cycles affected mechanized pine cone harvesting. They identified optimal harvesting efficiency while minimizing damage to tree branches and bark [17].

As summarized above, scholars both domestically and internationally have conducted systematic investigations into vibration harvesting mechanisms, equipment design and optimization, and the adaptability of harvesting parameters. However, due to variations in the vibration characteristics of CO trees compared to other fruit trees, as well as variations in fruit-stem attachment strength and fruit physical properties, existing harvesting devices struggle to achieve efficient harvesting of mature CO fruits [18]. This study designs a handheld CO vibration harvesting device that features low manufacturing cost, compact structure, flexibility, and portability. In this study: (1) Through the measurement of mechanical property parameters related to CO fruit harvesting, the detachment forces of the fruits and buds were determined; (2) A single-pendulum dynamic model is established to solve the dynamics model and analyze the detachment conditions of CO fruits. The influencing factors are then translated into operational parameters of the vibration harvesting device; (3) Modal and harmonic response analyses of the CO tree model are performed using ANSYS, so as to identify the optimal vibration frequency and amplitude for the harvesting device; (4) The ADAMS software is employed to perform rigid-flexible coupling simulations on the tree-device vibration harvesting system, analyzing the influence of various excitation parameters on the acceleration of key points; (5) Using Design-Expert 13, an orthogonal experiment is designed to establish a mathematical regression model relating the CO fruit picking rate to the influencing factors. Through analysis and optimization of the experimental data and response surfaces, the most suitable combination of working parameters for the harvesting device is established.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study on the Mechanical Characteristics of CO Fruit Picking

2.1.1. Materials and Equipment

When harvesting CO fruits from the branches, parameters such as fruit diameter, mass, and pedicel detachment force determine the operational parameters of the vibration harvesting device. Parameters such as the binding force between buds and pedicels can be used to analyze the damage rate of buds caused by the vibration harvesting device. The research object of this study is ‘Xianghua’ CO, a major cultivated variety of high-quality CO in Guangxi, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

‘Xianghua’ CO.

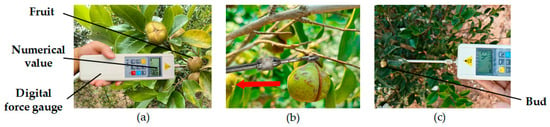

To obtain the mechanical property parameters related to the harvesting of CO fruits, measurements of the diameter, mass, and tangential detachment force of both the fruits and flower buds were conducted in November 2024 at the National CO Improved Variety Base in Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Within this investigation, a random sampling strategy was adopted to acquire samples from a CO improved-variety plantation, selecting CO fruits and buds directly from the trees for use as experimental units. During the measurement process, samples are randomly taken, with a total of 100 samples each. The testing equipment included a digital force gauge (range: 0~100 N, accuracy: ±0.005 N), an electronic balance (range: 0~2 kg, accuracy: 0.1 g), and a vernier caliper (range: 0~200 mm, accuracy: 0.02 mm). As shown in Figure 2, the tangential detachment forces of the CO fruits and buds were measured using the force gauge, and the diameter and mass of each detached fruit or bud were recorded.

Figure 2.

Detachment force measurement. (a) Fruit shedding force. (b) Tangential force measurement. (c) Bud shedding force.

2.1.2. Analysis of Picking Characteristic Parameters

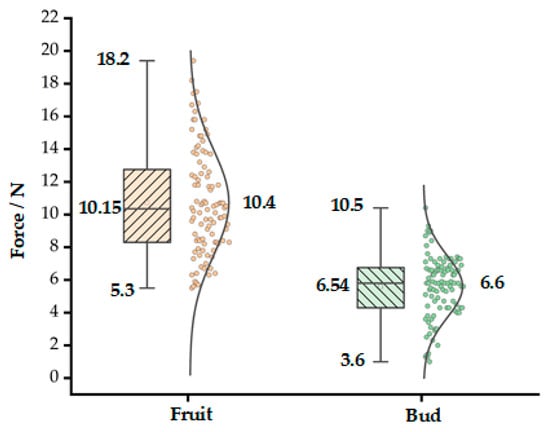

Figure 3 shows the distribution of detachment forces for CO fruits and their flower buds as measured in this study. The analysis indicates that there is minimal overlap between the distribution ranges of fruit and flower bud detachment forces. The average tangential detachment force of CO fruits is 10.40 N, with a median of 10.15 N, which is close to the mean value. The data are relatively uniformly distributed and concentrated near the median line, suggesting that the detachment forces of the fruits are relatively centralized without extreme values. In contrast, the average detachment force of flower buds is 6.60 N, with a median of 6.55 N. The data are concentrated and mostly located below the median line, indicating that the detachment forces of the flower buds are relatively lower. Compared with those of the fruits, the detachment forces of the flower buds exhibit a more concentrated distribution and are significantly smaller. Therefore, efficient harvesting can be achieved by increasing the tangential force applied to the CO fruit.

Figure 3.

Measurement data of detachment force.

As analyzed in Table 1, the mean diameter and mass of CO fruits are greater than those of flower buds. Furthermore, due to differences in mass and volume, the inertial force exerted on CO fruits when subjected to excitation vibration is significantly larger than that on flower buds [19]. Therefore, the design of the vibration harvesting device can be based on the differences in size and mass between the two, selecting an appropriate harvesting method.

Table 1.

Physical characteristic parameters of CO fruits and flower buds.

2.2. Analysis of Factors Affecting Forced Vibration Shedding of CO Fruits

2.2.1. Establishment of a Single-Pendulum Dynamic Model for Fruit-Branch System

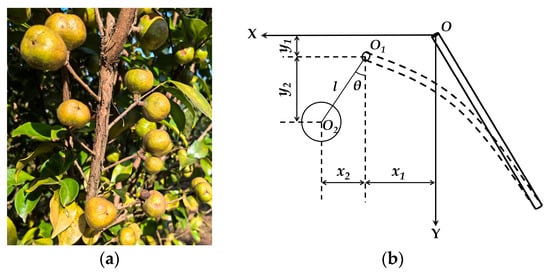

Under natural conditions, the fruit branches of the CO tree naturally droop along the direction of the fruit stalk due to gravity, as shown in Figure 4a. When applying harmonic excitation to the branches, the fruit swings with the branches. After maturation, the moisture content in the pedicel decreases, and the pedicel has relatively low mass; therefore, the pedicel mass can be disregarded, allowing the CO fruit to be treated as a fruit without a pedicel [20]. This can be simplified into a fruit-branch single-pendulum dynamic model [21,22].

Figure 4.

Single-pendulum dynamic model of CO fruit. (a) growth status of CO fruit; (b) simplified model.

By choosing the fruiting branch’s suspension point O as the coordinate origin, the X-axis is oriented along the branch’s horizontal motion and the Y-axis along its vertical motion, resulting in the XOY Cartesian system. The CO fruit is equivalently modeled as a solid sphere with its center of mass located at O2. With the vibration time denoted as t, the fruit-branch single-pendulum dynamic model of the CO is established [23], as shown in Figure 4b.

The motion of the fruit is treated as a single pendulum problem under harmonic displacement excitation, as shown in Equation (1).

where X0 is the overall horizontal position of the CO fruit, mm. Y0 is the overall vertical position of the CO fruit, mm. x1 is the horizontal position of the suspension point O, mm. y1 is the vertical position of the suspension point, mm. x2 is the horizontal position of the CO fruit, mm. y2 is the vertical position of the CO fruit, mm. l is the distance from the center of mass of the CO fruit to the suspension point, mm. θ is the angle between the line connecting the center of mass of the CO fruit to the suspension point and the vertical direction, °.

Based on the kinetic energy theorem, when the CO fruit is subjected to excitation and begins to swing, the kinetic energy T of the system model is given by Equation (2).

where T is the kinetic energy of the CO fruit, J. is the horizontal velocity of the suspension point, . is the vertical velocity of the suspension point, . is the angular velocity of the CO fruit relative to the suspension point, rad/s. m is the CO fruit quality, kg. I is the rotational inertia of the CO fruit, .

Taking the suspension point O2 as the zero potential energy reference, the potential energy equation of the model is given by Equation (3).

where U is the potential energy of the CO fruit, J. k is the equivalent elastic coefficient. g is the gravitational acceleration, 9.8 .

By combining Equations (2) and (3), the Lagrangian function is obtained, as shown in Equation (4).

where L is the Lagrangian function of the system under excitation of the CO fruit.

The fruits are not subjected to external forces during the vibration process. The Lagrange equation is used for solving, as shown in Equation (5).

Solving Equation (5) yields the dynamic differential equation of the fruit-branch single-pendulum model system under vibration.

The dynamic modeling framework focuses on an individual CO fruit as the subject of study, omitting secondary influences such as friction and impacts arising from neighboring fruits and branches. During the forced vibration process, the CO fruit undergoes small-amplitude oscillations [24]. It can be assumed that , , and are all first-order small quantities. The functions sin and cos are expanded into series with respect to , and terms of second order and higher are neglected, taking and . Moreover, the fruit tends more to swing collectively with the branch rather than to rotate on its own. Without considering the rotational inertia of the CO fruit, Equation (7) is obtained.

2.2.2. Solution of the Single-Pendulum Dynamic Model for CO Fruit

In the single-pendulum dynamic model of the CO fruit, when the harvesting device transmits vibrational inertial forces to the fruit-bearing lateral branch, the motion pattern of the branch at the fruit suspension point is consistent with the vibration pattern of the harvesting device [25]. Since the applied force is perpendicular to the direction of the fruit-bearing lateral branch and the branch naturally droops, the amplitude of vibration in the Y-direction can be approximated as zero. Therefore, the motion pattern of the branch is described by Equation (8).

where A0 is the amplitude of branch vibration, mm. φ is the branch vibration frequency, Hz.

By substituting Equation (8) into Equation (7), Equation (9) is obtained.

where is the torsional angular acceleration of the CO fruit relative to the hanging point of the branch,.

Equation (9) represents a second-order linear nonhomogeneous ordinary differential equation with constant coefficients, and solving it yields the general solution presented in Equation (10).

where c1 and c2 is constant.

Assuming, as shown in Equation (11),

where is natural frequency of fruit vibration, Hz.

When the initial condition is τ = 0, as shown in Equation (12),

By substituting Equations (11) and (12) into Equation (10), Equation (13) is obtained.

From the above calculation process and results, it can be seen that when the CO tree is subjected to harmonic excitation force, the forced vibration of the tree is also a harmonic vibration, and it moves back and forth in a straight line along the X-direction.

2.2.3. Analysis of Vibrational Shedding of the CO Fruits

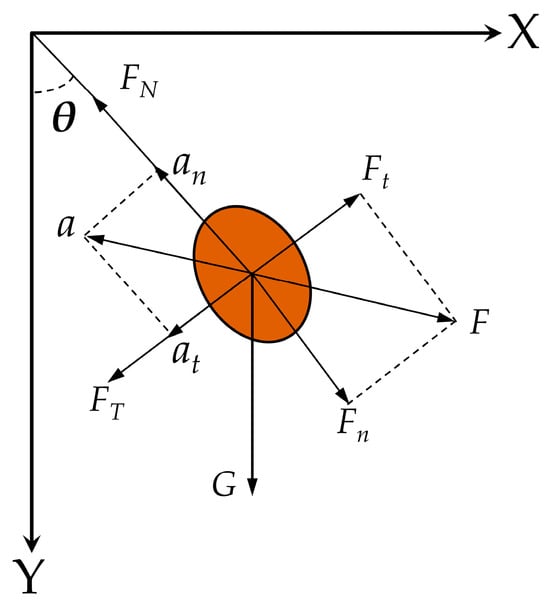

Under the action of excitation force, the CO tree absorbs the vibrational energy and transmits it to the fruit through the branches, inducing forced motion of the CO fruit relative to its suspension point. During this motion, the fruit is subjected to the combined effects of its own weight (G), the pedicel binding force (FN), and the inertial force (F). The F can be decomposed into a normal component (Fn) and a tangential component (Ft). Fruit detachment is achieved when either the normal inertial force (Fn) exceeds the normal binding force (FN) between the fruit and the pedicel, or the tangential inertial force (Ft) exceeds the tangential binding force (FT). The force analysis of the CO fruit is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Stress analysis of the CO fruit.

In Figure 5, G is the gravity of the CO fruit, N. F is the inertia force, N. FN is the pedicel binding force, N. FT is the tangential binding force, N. Fn is the normal inertial force, N. Ft is the tangential inertial force, N. is the acceleration generated by forced motion, . is the normal acceleration of the CO fruit relative to the branch, . is the relative tangential acceleration of the CO fruit to branches, .

Neglecting the self-weight of the CO fruit, the fruit detachment conditions in the radial and normal directions are given by Equation (14).

Since the excitation force is perpendicular to the branch growth direction, the actual vibration of the fruit can be regarded as a tangential reciprocating oscillation. According to the measurement data of the tangential detachment force of CO fruits presented in Section 2.1.2 (above), the average tangential detachment force of the CO fruit in the direction perpendicular to their growth is 10.4 N, i.e., FT = 10.4 N. Therefore, the detachment acceleration of the CO fruit is given by Equation (15).

Among the 100 test samples, it was statistically found that the average mass of the CO fruit during the optimal harvesting period is approximately 20.5 g. By substituting this value into Equation (15), it can be determined that the tangential acceleration of the CO fruit must exceed 507.5 for detachment to occur.

Without considering the influence of other factors, in practical vibration harvesting, due to the relatively low natural vibration frequency of the CO fruit, the natural frequency of the fruit can be neglected. In Equation (15), the vibration frequency , amplitude A0, and vibration duration of the fruiting branch are the main factors affecting fruit detachment. When the clamping position of the harvesting device is fixed, both the vibration frequency and amplitude exhibit a positive correlation with the vibration harvesting efficiency of the CO fruit.

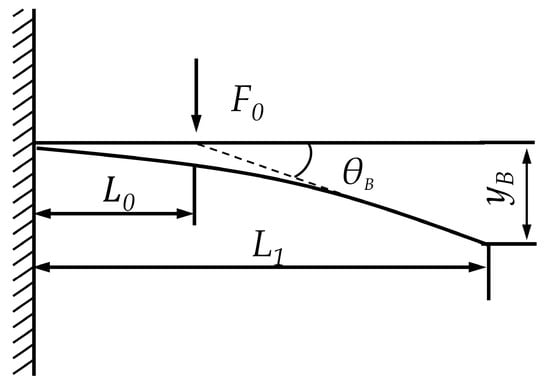

The branches of the CO tree are simplified into a cantilever beam model, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Cantilever beam model of fruiting branches.

The maximum deflection of the fruiting branch is shown in Equation (16).

The rotation angle of its end section is shown in Equation (17).

where is the maximum deflection of the fruiting branch, mm. F0 is the applied excitation force, N. L1 is the length of the fruiting branch, mm. L0 is the location of applied force, mm. E is the elastic modulus of the fruiting branch, . is the moment of inertia of the fruiting branch cross-section, . is the rotation angle at the end section of the fruiting branch, °.

By analyzing Equations (16) and (17), it can be concluded that the vibration position is also an important influencing factor on the detachment of CO fruits.

2.3. Selection of Vibration Harvesting Parameters for CO Fruits

2.3.1. Finite Element Modeling of the CO Tree

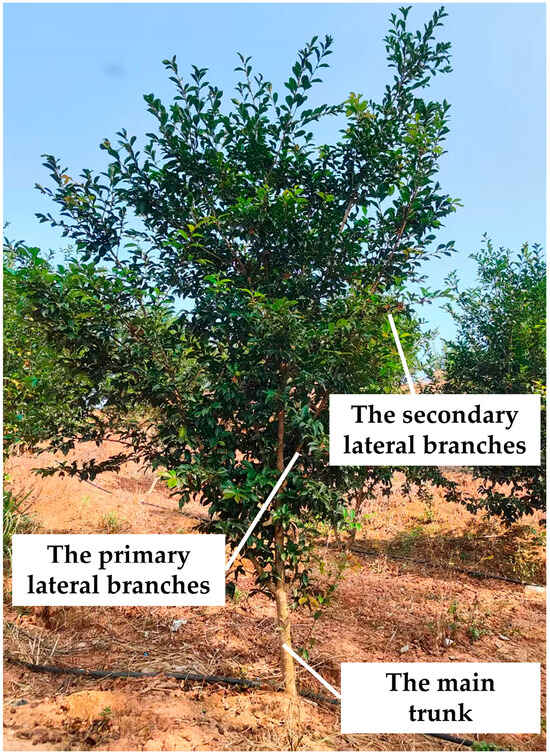

For the construction of 3D model of fruit trees, many researchers, both domestically and internationally, have conducted in-depth studies [26,27]. In the present work, a three-dimensional model of the CO tree is developed to carry out dynamic analysis in the course of vibration harvesting. The focus is placed on the position, structure, and mechanical properties of the branches and trunk [28]. Through investigation of the growth characteristics of the CO tree, the following structural features were identified: (1) The overall structure of the CO tree is approximately symmetrical; (2) The primary lateral branches exhibit a layered arrangement along the growth direction of the main trunk, with the branching angle between the lateral branches and the main trunk gradually decreasing along the trunk and ranging between 30° and 55°; (3) The length and diameter of the secondary lateral branches are significantly smaller than those of the primary lateral branches. The hierarchical structure of the CO tree is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Hierarchical structure of the CO tree.

Randomly selected samples of eight CO trees were measured, focusing on the diameter and height of the main trunk, as well as the diameter, length, and canopy spread of the primary and secondary lateral branches. The measurement results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measured dimensions of CO tree branches and trunk (Unit: mm).

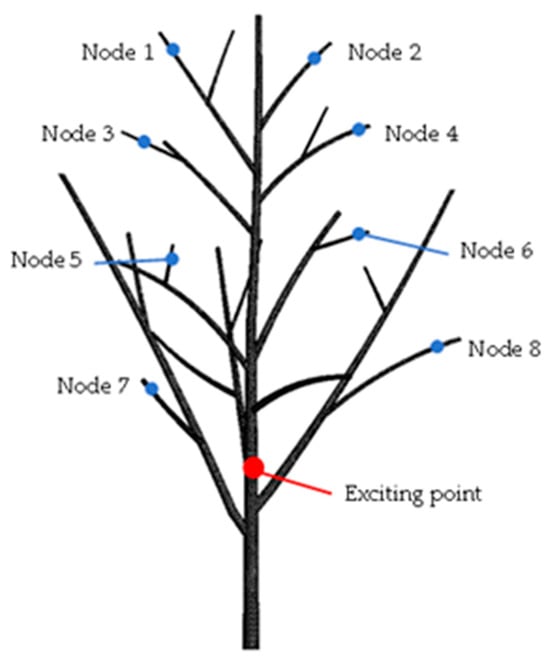

Using the parameters mentioned earlier, a three-dimensional model of the CO tree was created in SolidWorks (2020) and then transferred to ANSYS (2021 R1) for further analysis. According to previous research by our research group, the mechanical properties of the CO tree material were defined as follows: elastic modulus of 8900 MPa, Poisson’s ratio of 0.3, material density of 1082 , and damping coefficient of 0.0083 [4]. An irregular 3D solid mesh was generated using the Solid186 element type, with a predefined mesh size of 8 mm. The Solid186 element is an 8-node structural solid element, where each node has three translational degrees of freedom along the X, Y, and Z directions. This element type is capable of simulating hyperelasticity, creep, large deformations, and large strains, making it well-suited for analyzing the vibration response characteristics of woody materials such as those found in fruit tree branches. Due to the large overall size of the established model, aiming to reduce computation time and meet the requirements of computational accuracy, the size of the finite element mesh elements is set to 6mm. The resulting meshed model and key nodal elements are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The 3D model of the CO tree.

2.3.2. Finite Element Analysis

Vibration manifests as displacement, but fundamentally involves the flow of energy. Resonance, as a special form of vibration, is induced by small periodic excitations and leads to structural deformation and dynamic stresses. Mature fruits have the weakest connection with the tree, and the destructive effect of resonance can result in relatively ideal separation [29,30].

In accordance with the CO tree’s growth traits, a fixed constraint was imposed at the main trunk’s base, and the crown was regarded as a free extremity. Because high-frequency vibrations often induce considerable energy loss as they propagate, the energy utilization efficiency tends to be low and the tree structure may suffer damage [31]. Moreover, the excitation frequency of typical vibration devices is generally below 40 Hz. Therefore, only natural frequencies below 40 Hz were considered.

In this study: (1) Modal analysis enables relatively accurate identification of the natural frequencies and mode shapes of a 3D model of CO trees. By analyzing the mode shapes, an optimal frequency range for vibration-based harvesting can be selected, thus providing a rational basis for determining the vibration frequency of the harvesting device [32]. (2) Harmonic response analysis was performed with the external excitation prescribed as displacement, to examine the response of the CO tree under various frequencies and to identify the corresponding optimal vibration frequency. By varying the displacement amplitude, the acceleration response at the key nodal elements was increased until it reached the detachment acceleration of CO fruits, thereby determining the vibration amplitude of the harvesting device.

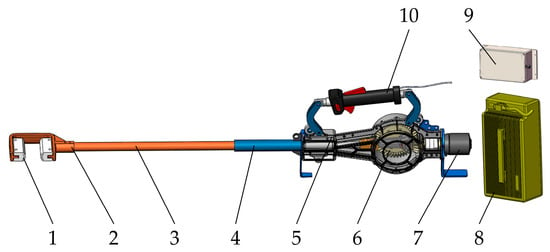

2.4. Design of the CO Vibration Harvesting Device

2.4.1. Structure and Working Principle of the Vibration Harvesting Device

Based on the analysis results of the CO fruit vibration abscission and the vibration characteristics of the CO tree, a handheld shaking-type CO vibration harvesting device was designed. The device consists of a picking hook, gripping handle, vibration rod, shaking mechanism, motor, battery, controller, and speed control handle, as shown in Figure 9. The excitation mechanism is located inside the housing. The motor transmits power to the bevel gear in the vibrating mechanism, where the orthogonal bevel gear set converts the motor’s rotational motion into linear reciprocating motion of the vibration rod, thereby generating vibrations. The vibration frequency of the device can be adjusted by regulating the motor speed through the speed control handle and the controller. A rubber block and a picking hook are mounted on the vibration rod. The main operational parameters of the handheld CO vibration harvesting device are listed in Table 3.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of the structure of handheld CO vibration harvesting device. (1) rubber block; (2) picking hook; (3) vibration rod; (4) hand lever; (5) Housing; (6) vibrating mechanism; (7) motor; (8) battery; (9) controller; (10) speed control handle.

Table 3.

Main operating parameters of handheld CO vibration harvesting device.

During operation, the power is turned on, and the speed control handle is used to adjust the vibration frequency of the device. The picking hook is placed against the tree branch, and its contact surface is equipped with a polyurethane rubber pad to reduce damage to the branch during gripping. The eccentric rotational force output by the excitation mechanism is transmitted to the CO tree branch through the picking hook and the vibration rod, causing the branch to undergo forced vibration under the excitation force. As the vibration frequency of the branch increases, the CO fruit accelerates along with the branch. When the vibration frequency reaches a certain value, the inertial force generated by the excitation applied to the tree by the harvesting device exceeds the binding force between the fruit and the branch. As a result, the fruit detaches from the branch, completing the harvesting process.

2.4.2. Design of Vibrating Mechanism

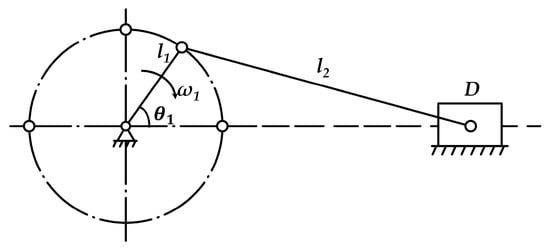

Different vibration harvesting methods provide various forms of excitation forces, resulting in distinctly different vibration responses in CO trees and harvesting outcomes. The mechanical system design of various vibration harvesting technologies must take into account different factors and design procedures. The handheld CO vibration harvesting device employs a centralized crank-slider mechanism as the excitation mechanism, as shown in Figure 10. This mechanism features high motion stability, symmetrical force distribution, and no quick-return effect, resulting in minimal impact on both the machine and the operator. It is therefore well suited for high-speed operation scenarios.

Figure 10.

Mathematical model of crank vibration mechanism.

In Figure 10, is the angular velocity, . is the crank length, mm. is the connecting rod length, mm.

Assuming the motor rotates at a constant speed with an angular velocity of , the vibration device moves horizontally, and its motion equation is given as Equation (18).

When , Equation (18) can be simplified to . By letting , it can be further simplified to Equation (19).

where (with being the initial phase), which is substituted into Equation (19). By letting , Equation (20) is obtained.

where the amplitude . Equation (20) thus represents the branch motion equation described in Section 2.2.2, thereby achieving simple harmonic vibration of the branch.

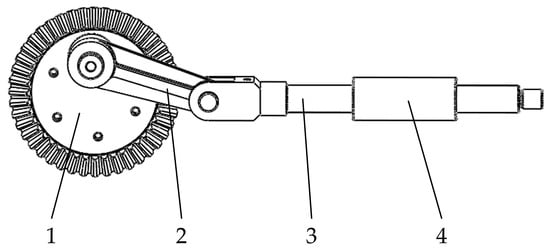

The vibrating mechanism consists of bevel gears, a connecting rod, a reciprocating rod, and a linear bearing, as shown in Figure 11. During operation, the mechanism converts the rotational motion of the motor into linear motion of the vibration rod, thereby applying variable-frequency excitation to the fruit-bearing branch and achieving fruit harvesting.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of the vibrating mechanism. (1) bevel gear; (2) connecting rod; (3) reciprocating rod; (4) linear bearing.

2.4.3. Selection and Design of Related Devices

To ensure the normal operation of the harvesting device, the motor, speed control system, and other related components were selected and designed accordingly. A permanent magnet synchronous motor with a rated power of 1 kW and a maximum speed of 3000 was chosen for the harvesting device. A brushless controller was adopted to regulate the real-time rotational speed of the motor, thereby adjusting the output vibration frequency of the device. The power supply is composed of a lithium-ion battery pack that provides benefits including elevated energy density, minimal self-discharge, and extended operational lifespan. The battery has an output voltage of 48 V, a capacity of 20 Ah, a mass of 3 kg, and provides an operating time of 8 h.

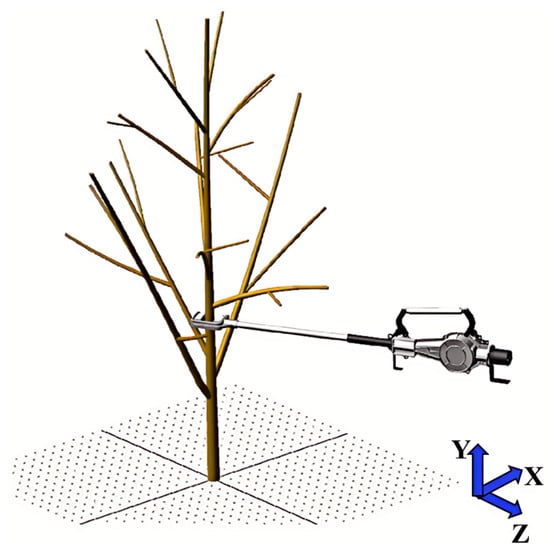

2.5. Rigid-Flexible Coupling Simulation of the CO Tree-Vibration Harvesting Device

For a deeper investigation of the lateral branches’ response behavior in the CO tree, to confirm the dynamic model’s precision, and to evaluate the viability of the harvesting actuation mechanism, this section performs a rigid-flexible coupling simulation of the vibration system using ANSYS and ADAMS (2020) [33,34]. In ANSYS, four interface interaction nodes between ADAMS and ANSYS were established: one at the interaction point between the CO tree and the ground, and three at the interaction points between the tree trunk and the gripping mechanism, located at heights of 600 mm, 900 mm, and 1200 mm, respectively. Forty-five modes of the model were extracted, and an MNF (Modal Neutral File) was generated. The generated MNF was then imported into the ADAMS. The inherent frequencies of each mode before and after the import process were compared, and no significant changes were observed, confirming the successful import of the modal neutral file for the flexible body model of the CO tree. Meanwhile, the vibration harvesting device model, previously created in SolidWorks, was imported into ADAMS to establish the rigid-flexible coupling model. The configuration is illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Rigid-flexible coupling model of the CO tree vibration harvesting device.

Following the functional principle of the vibration harvesting device, specific constraints were established for the simulation. Revolute joints were added between the excitation mechanism and the housing, prismatic joints were added between the vibration rod and the housing, and fixed joints were added between the housing and the ground. A contact force was defined between the rubber block and the CO tree. To simulate the contact effect between the CO tree and the soil, a linear bushing was used as a substitute. Referring to relevant literature [35,36,37], the translational properties of the linear bushing were defined with a stiffness of N/m and a damping coefficient of N·s/m, while the rotational properties were defined with a stiffness of 2500 N·m/rad and a damping coefficient of 1000 N·m·s/rad.

A driving torque was applied. A rotational drive was added to the revolute joint on the gear shaft.

2.6. Field Experiment

Based on the simulation results, it is concluded that the handheld CO vibration harvesting device meets the fruit-drop requirements. The key factors influencing fruit detachment and harvesting efficiency were identified as the vibration frequency, amplitude, vibration duration, and vibration height. Vibration harvesting experiments were conducted in October 2025 at a CO cultivation demonstration garden in Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China. Different vibration frequencies, vibration heights, and vibration durations were selected for the harvesting operations. The number of CO fruits on the fruit-bearing branches was counted before and after each operation. The field setup of the harvesting experiment is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

CO vibration harvesting test site.

On the day of the experiment, the air temperature was 24 °C, relative humidity was 76%, and the weather was sunny with occasional gusty winds. The experimental site was located in a mountainous area with red soil, and the soil moisture content was 32%. The sample trees were 3 years old, with a height ranging from 2.0 to 2.7 meters and a crown spread of 2.6 to 3.5 , exhibiting an open canopy structure. The CO fruits were at the mature stage and mainly distributed in the outer part of the canopy, which is consistent with actual harvesting conditions for CO.

The picking rate of CO fruits refers to the proportion of the number of CO fruits detached during the harvesting operation relative to the total number of CO fruits on the fruit-bearing branches. The total number of CO fruits is equal to the sum of the number of fruits detached and the number of fruits remaining on the branches during the harvesting operation. In the present experiment, the picking rate served as the main evaluation index, and its computation formula is given in Equation (21).

where P is the fruit picking rate, %. N1 is the number of detached CO fruits, pieces. N2 is the number of undetached CO fruits, pieces.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Modal Analysis of CO Tree

Using the Modal module, the first 45 natural frequencies of the CO tree model were calculated. The main modal frequencies of the CO tree are listed in Table 4. The modal frequency range spans from 2.3 to 40.2 Hz, which largely covers the design range of the vibration harvesting device. Figure 14 shows the modal cloud diagram corresponding to the optimal vibration mode shape of the CO tree model. It is indicated by the results that desirable response characteristics occur in the 8th, 12th, 13th, 15th, 18th, and 20th modes of the tree. These modes are marked by consistent vibration response patterns among branches and relatively large amplitudes, leading to the determination of an optimal vibration harvesting frequency band of 10~18 Hz for the CO tree.

Table 4.

Main modal frequencies table of the finite element model of CO tree.

Figure 14.

Modal cloud chart of the CO tree model under optimal vibration mode. (a) Order 8, frequency 10.6 Hz; (b) Order 12, frequency 12.2 Hz; (c) Order 13, frequency 13.7 Hz; (d) Order 15, frequency 14.5 Hz; (e) Order 18, frequency 15.4 Hz; (f) Order 20, frequency 17.2 Hz.

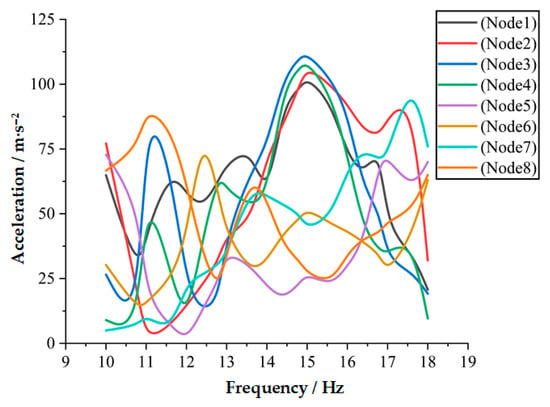

3.2. Harmonic Response Analysis of CO Tree

By performing harmonic response analysis, the dynamic response of the CO tree was examined at different frequencies, and the optimal corresponding vibration frequency was identified. Based on the modal analysis results, the optimal vibration frequency range for the vibration harvesting of CO fruits was determined to be 10~18 Hz. Therefore, the frequency range for harmonic response analysis was set from 10 to 18 Hz. As shown in Figure 8, the excitation point (Point P) was located 900 mm above the ground. When a displacement load of 10 mm was applied, the acceleration responses of eight key nodes were recorded, as shown in Figure 15. The response spectrum contains multiple peaks, among which four prominent peaks are clearly identifiable. Notably, the peak acceleration values vary across different branches. Detection Points 3 and 4 exhibited relatively high acceleration responses of 112.2 and 109.5 , respectively, at 15 Hz. On the CO tree, fruits are predominantly distributed in the middle to upper regions of the tree canopy. At 15 Hz, Detection Points 1, 2, 3, and 4, located in the upper part of the canopy, demonstrated larger and more concentrated response values. Therefore, an appropriate excitation amplitude should be applied to ensure that the acceleration at Detection Point 1 exceeds 507.5 , thereby facilitating effective separation of the CO fruits.

Figure 15.

The acceleration responses at eight detection points under a 10 mm displacement load applied to the canopy.

It can be considered that harmonic response analysis belongs to the category of linear analyses, as exemplified by Equation (22).

where A1 is applied excitation amplitude of 10 mm. is the acceleration response value of the detection point under the 10 mm amplitude excitation, . A2 is optimal excitation amplitude, mm. is the acceleration required to detach the fruit from the branch, .

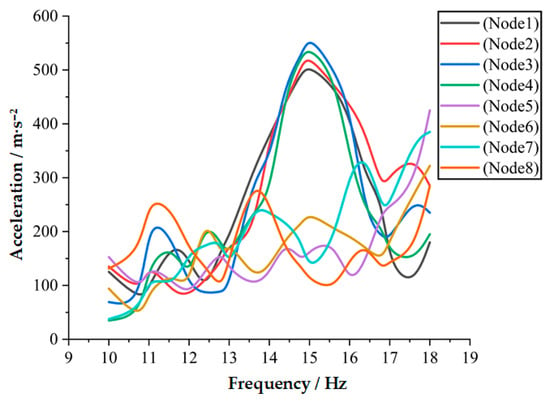

As shown in Figure 15, when a displacement amplitude of 10 mm is applied, the acceleration at Detection Point 1 is 96.8 . Based on the linear characteristics of harmonic response analysis, the displacement load required at excitation Point P to achieve an acceleration response of 507.5 at Detection Point 1 is calculated to be 52.4 mm. As illustrated in Figure 16, the acceleration responses of all detection points are presented when a displacement load of 52.4 mm is applied at Point P. Comparing Figure 10 with Figure 11 reveals that the acceleration responses at every detection point rise as the displacement load at Point P increases, and the general tendency stays uniform throughout. At an excitation frequency of 15 Hz, the acceleration responses of detection points 1, 2, 3, and 4 all exceed 507.5 , reaching the acceleration required for CO fruit detachment.

Figure 16.

The acceleration responses at eight detection points under a 52.4 mm displacement load applied to the canopy.

Through harmonic response analysis of the CO tree model, the optimal vibration amplitude for vibration harvesting was determined to be 52.4 mm, providing accurate design parameters for the harvesting device.

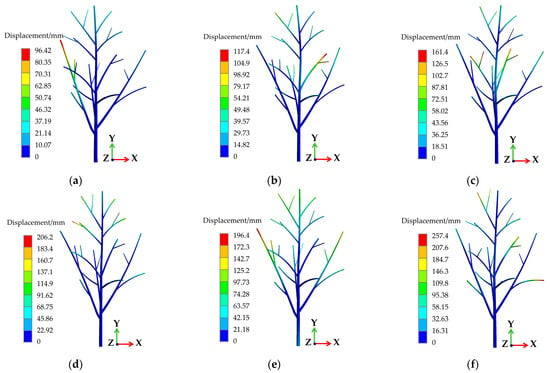

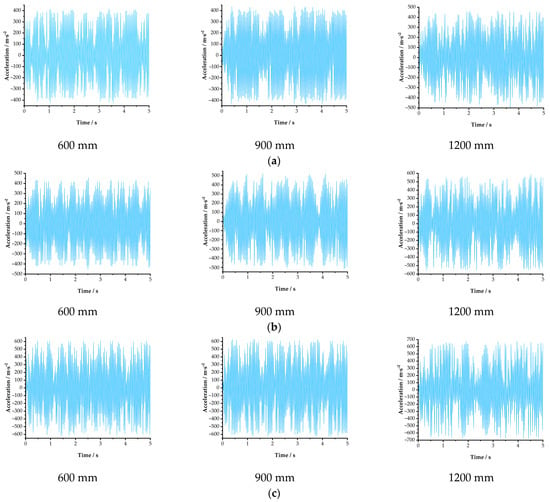

3.3. Rigid-Flexible Coupling Simulation Based on ADAMS

To analyze the acceleration response of the lateral branches of the CO tree at different vibration heights, and based on field operation conditions, excitations were applied at heights of 600, 900, and 1200 mm above the ground. Vibration frequencies of 12, 15, and 18 Hz were selected, with a simulation duration of 5 s and 350 times steps. The Z-direction was chosen as the excitation direction, with the excitation force applied perpendicularly to the branch. The uppermost part of the second lateral branch within the tree canopy was chosen as the measurement location, and the corresponding simulation outcomes are presented in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Results of lateral branch acceleration response at different vibration heights. (a) Z-direction acceleration of lateral branches at different vibration heights at 12 Hz. (b) Z-direction acceleration of lateral branches at different vibration heights at 15 Hz. (c) Z-direction acceleration of lateral branches at different vibration heights at 18 Hz.

In the rigid-flexible coupling vibration model, the CO vibration harvesting device applies an excitation force to the CO tree along the Z-axis direction. As shown in Figure 17, under the same vibration frequency, the lateral branch acceleration increases with increasing vibration height; under the same vibration height, the lateral branch acceleration increases with increasing vibration frequency. When the vibration frequency is 15 Hz and the vibration height is 900 mm, the maximum lateral branch acceleration reaches 514.5 , which is greater than the theoretical fruit-abscission acceleration of 507.5 . When the vibration frequency is 18 Hz and the vibration height is 1200 mm, the maximum lateral branch acceleration reaches 677.3 , indicating the expected optimal harvesting performance. From the results discussed above, it can be inferred that the forced vibration of CO trees is of a periodic character, and the acceleration response escalates with increasing vibration frequency and height, a trend that aligns with theoretical expectations.

3.4. Field Experiment Results and Analysis

3.4.1. Experimental Results

The experimental factor coding was designed based on the vibration frequency (A), the vibration height (B), the vibration duration (C), and the fruit picking rate (P), as shown in Table 5. Based on preliminary experiments, the vibration durations were set to 10, 15, and 20 s. An orthogonal experiment with three factors and three levels was conducted using the Box–Behnken module in Design-Expert 13 to determine the optimal operational parameter combination that achieved the highest CO fruit picking rate [38,39,40].

Table 5.

Experimental factors and level coding.

The total number of experiments, as shown in Formula (23).

where K is the total number of independent variables, taken as K = 3, and M0 is the number of center-point replicate trials, taken as M0 = 5.

Therefore, a total of 17 experimental trials were designed. Each trial was repeated three times, and the average value of the three repetitions was taken as the result for that trial. The difference in results is within the expected error range, indicating that the experiment has good reproducibility. The experimental results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Test results.

3.4.2. Analysis of Experimental Results

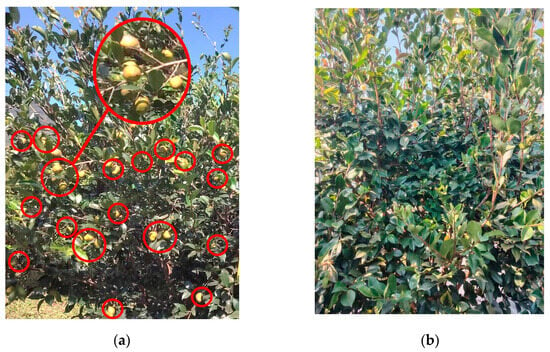

The operation effect before and after vibration harvesting is shown in Figure 18. In Figure 18a, the red circle marks the fruit on the CO tree before harvesting. Figure 18b shows the situation after vibration harvesting, where the CO fruit has mostly fallen off. The data from Table 6 underwent multiple quadratic regression analysis in Design-Expert 13, and the subsequent ANOVA results for the fruit picking rate in vibration harvesting are given in Table 7.

Figure 18.

Comparison before and after picking CO. (a) Before vibration. (b) After vibration.

Table 7.

Analysis of variance in CO fruits picking rate.

According to the ANOVA results for the fruit picking rate, the model significance test yielded a p-value 0.0001, indicating that the regression model with P as the response variable is highly significant. The lack-of-fit p-value was 0.9692, which was not significant, suggesting that the model is relatively stable and exhibits a high degree of goodness-of-fit. The vibration frequency, vibration height, vibration duration, as well as the interaction terms AB, AC, BC, and the quadratic terms A2, B2, and C2, had highly significant effects on the fruit picking rate. A quadratic polynomial regression model was established to describe the relationship between the fruit picking rate and the vibration frequency, vibration height, and vibration duration during vibration harvesting, as shown in Equation (24).

3.4.3. Contribution Rate Analysis

The contribution rate can intuitively reflect the influence of each factor on the constructed quadratic polynomial regression model. A higher contribution rate indicates a greater influence. The contribution rate (Δj) is calculated using Equation (25).

The expression for the reference value (δ) is given in Equation (26).

where is the contribution rate of the first-order term of factor j. is the contribution rate of the second-order term of factor j. is the contribution rate of the interaction between factor i and factor j.

Based on the F-values from the above analysis of variance and Equations (25) and (26), the Δj of the various factors to CO fruits detachment were calculated, as shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Contribution rates of various factors to different indicators.

As presented in Table 8, every factor plays a statistically significant role in determining the fruit picking rate. The contribution rates of the factors in descending order are: A B C.

3.4.4. Response Surface Analysis

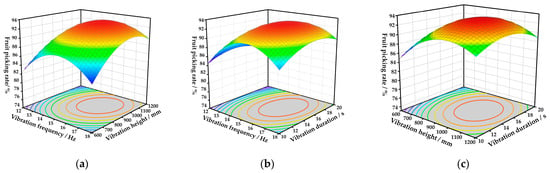

In order to visually assess the impact of the three factors on the evaluation index, the experiment maintained one factor at the 0 level, simultaneously investigating the interactive effect of the other two factors. Based on the established quadratic polynomial regression model, interaction response surfaces depicting the pairwise effects of vibration frequency vs. vibration height, vibration frequency vs. vibration duration, and vibration height vs. vibration duration on the fruit picking rate during harvesting were plotted using Origin software, as shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

The influence of experimental factors on the fruit picking rate. (a) Vibration duration is 15 s. (b) Vibration height is 900 mm. (c) Vibration frequency is 15 Hz.

When the vibration duration was 15 s, the interaction effect between vibration frequency and height on the fruit picking rate of CO is shown in Figure 19a. At a constant height, the fruit picking rate increased slowly with increasing vibration frequency and then gradually decreased. Under any given vibration frequency, the picking rate initially increased and then gradually declined with increasing vibration height. The maximum picking rate of 92.87% was achieved at a vibration frequency of 15 Hz, a height of 900 mm, and a vibration duration of 15 s. When the vibration height was 900 mm, the interaction effect between vibration frequency and duration on the picking rate is shown in Figure 19b. At a constant vibration duration, the picking rate increased with increasing vibration frequency, showing a trend of initial rise followed by gradual decline. When the vibration frequency was held constant, the picking rate increased slowly with increasing vibration duration. Due to the fact that a lower clamping position can negatively affect the vibration displacement of the main branches and fruit branches, while a higher clamping position may cause damage to the CO tree, setting the clamping position of the harvesting device near the middle part of the main branch is beneficial for improving the picking rate. When the vibration frequency was 15 Hz, the interaction effect between vibration height and duration on the picking rate is shown in Figure 19c. At a constant vibration duration, the picking rate initially increased and then gradually stabilized with increasing vibration height. When the vibration height was constant, the picking rate exhibited a relatively stable trend with increasing vibration duration.

3.4.5. Parameter Optimization

The results of the experimental analysis reveal that distinct considerations produce considerable variation in their influence on CO’s mechanized harvesting efficiency. Therefore, determining the optimal vibration parameters is of great importance. The optimization adjustment function in Design-Expert 13 was utilized to optimize the quadratic polynomial regression model. The constraints of the objective function are defined by Equation (27).

The optimization of the objective function yielded the optimal working parameter combination for the handheld CO vibration harvesting device: a vibration frequency of 14 Hz, a vibration height of 980 mm, and a vibration duration of 13 s. To verify the reliability of the optimized parameter combination, a harvesting operation was conducted using these parameters, resulting in the picking rate of 95.22%, which met the expected outcome.

4. Conclusions

Based on the investigation of the mechanical properties of CO fruits, a handheld vibration harvesting device was developed. This paper describes the overall structure and working principle of the device, and presents a study on its vibration parameters.

- (1)

- By solving the dynamic model of a simple pendulum, the tangential acceleration required for fruit detachment was determined to be 507.5 . The main factors influencing fruit shedding were identified as vibration frequency, amplitude, vibration duration, and vibration height.

- (2)

- Finite element analysis indicated that the optimal vibration frequency range for the CO tree lies between 10 Hz and 18 Hz. It was further found that an amplitude of 52.4 mm combined with a frequency of 15 Hz can generate the acceleration necessary for fruit detachment.

- (3)

- Rigid–flexible coupling simulations were conducted to verify the validity of the dynamic model and to assess the feasibility of the harvesting device; these simulations also revealed variations in lateral branch acceleration under different parameter settings.

- (4)

- The experimental results were optimized using the Response Optimization module in Design-Expert. The optimal parameter combination for the handheld CO vibration harvesting device was determined to be: vibration frequency of 14 Hz, vibration height of 980 mm, and vibration duration of 13 s. Under these conditions, the fruit-picking efficiency reached 95.22%, demonstrating an ideal harvesting performance that meets the requirements for CO fruit harvesting.

At present, the handheld vibration harvesting device remains in the experimental stage. Due to a lack of practical experience, there are still numerous shortcomings that need to be improved and refined, indicating a certain gap from achieving truly mechanized CO harvesting. In the future, we will focus on key objectives including high efficiency, low load, and user-friendly operation for the vibration harvesting device. Research efforts will concentrate on structural optimization, lightweight materials, and real-time sensing technologies to achieve significant breakthroughs. The forthcoming work aims to enhance operational performance, ergonomics, and applicability of the device, thereby better meeting the practical needs of CO growers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.G. and H.Z.; methodology, Q.G. and H.Z.; software, H.Z.; validation, Q.G., H.Z., Q.X. and D.W.; formal analysis, H.Z. and Q.X.; investigation, H.Z., D.W. and Z.D.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.G., H.Z., Q.X., D.W., J.H., Y.C., Y.L., Z.J. and Z.D.; visualization, Q.G.; supervision, Q.G. and Q.X.; project administration, Q.G.; funding acquisition, Q.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC was funded by the Camellia oleifera Suitable for Machine Harvesting Variety Screening and Harvesting Technology Equipment Research and Application (Guike AA24263023).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, J.Z. Current Status and Countermeasures of Oil Tea Industry Development in Guangxi. Rural Sci. Exp. 2024, 12, 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W. Research on the Value of Camellia Oil Planting and the Plantation Technology. For. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2025, 57, 181–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.P.; Tang, Q.J.; Zhang, D.Q.; Luo, H.J. Research on Mechanized Planting of Camellia oleifera in Hilly and Mountainous Areas of China. South Forum 2025, 56, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Han, J.; Zeng, S.; Wang, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, D.; Ye, H.; Lu, J.; Zeng, H. Performance Analysis and Operation Parameter Optimization of Shaker-Type Harvesting for Camellia Fruits. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, F.; Xing, H.; Yan, L.; Yang, J. Kinematic Analysis of the Vibration Harvesting Process of Lycium barbarum L. Fruit. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Tsuchikawa, S.; Ma, T.; Hu, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gao, Z.; Chen, J. Modal Analysis and Experiment of a Lycium barbarum L. Shrub for Efficient Vibration Harvesting of Fruit. Agriculture 2021, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, C.; Polat, R.; Ozalp, A.F. Investigation of the Vibration Effect of Using Single or Double Eccentric Mass in the Trunk Shakers Used in Fruit Harvesting. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 35, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Su, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Effects of Different Excitation Parameters on Mechanized Harvesting Performance and Postharvest Quality of First-Crop Organic Goji Berries in Saline-Alkali Land. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, L.; Chen, C.; Hu, G.; Zhou, J.; Sugirbay, A.; Chen, J. Investigating the Dynamic Behavior of an Apple Branch-Stem-Fruit Model Using Experimental and Simulation Analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 186, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, A.; Hang, X. Finite Element Explicit Dynamics Simulation of Motion and Shedding of Jujube Fruits Under Forced Vibration. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Shen, T.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, G.; Hu, A.; Fang, S.; Cao, Y.; Yao, X. Design and Experiment of the Comb-Brush Harvesting Machine with Variable Spacing for Oil-Tea Camellia Fruit. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, G.; Chu, C. Research on Fruit Picking Test of Blueberry Harvesting Machinery Under Transmission Clearance. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Yu, C.; Feng, J.; Qiao, Y. Vibration Response Characteristics of Jujube Trees Based on Finite Element Method and Structure-from-Motion. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 331, 113125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Bai, X.; Xu, D.; Li, W.; Chen, C. Experiment and Analysis on Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Shedding Force Based on Low-Frequency Vibration Response. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 204, 117242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Lai, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, S.; Song, D. Design and Operation Parameters of Vibrating Harvester for Coffea arabica L. Agriculture 2023, 13, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Niu, Z.; Deng, J.; Mu, H.; Cui, Y. Vibration Simulation and Experiment of Three Open-Center Shape Olive Trees. Vibroeng. Procedia 2022, 41, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-García, S.; Blanco-Roldán, G.L.; Gil-Ribes, J.A.; Agüera-Vega, J. Dynamic Analysis of Olive Trees in Intensive Orchards Under Forced Vibration. Trees 2008, 22, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Fang, D.; Wu, C.; Wang, B.; Zhu, H.; Hu, T.; Wu, D. Dynamic Response of Camellia Oleifera Fruit-Branch Based on Mathematical Model and High-Speed Photography. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 237, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Q.; Luo, T.; Li, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J. Effects of Different Picking Patterns and Sequences on the Vibration of Apples on the Same Branch. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 237, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, T.; Inagaki, T.; Chen, Q.; Gao, Z.; Sun, L.; Cai, H.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Finite Element Method Simulations and Experiments of Detachments of Lycium barbarum L. Forests 2021, 12, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, D. Motion Trajectory of Different Fruiting Types of Camellia Oleifera Fruit Under Vibration: Theoretical and Experimental Studies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 231, 121173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dairi, M.; Pathare, P.B.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Al-Mahdouri, A. Effect on Physiological Properties of Banana Fruit Based on Pendulum Impact Test and Storage. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Wang, J.; Song, Z.; Tang, D.; Shen, C. Mechanism and Experimental Study on the Fruit Detachment of Chinese Wolfberry Through Reciprocating Vibration. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2024, 17, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Cui, J.; Ding, K.; Zhang, H. Simulation Experiment in Lab on Force Transfer Effect of Jujube Under Vibration Excitation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2017, 33, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cui, W.; Zhang, A. Study of Vibration Patterns and Response Transfer Relationships in Walnut Tree Trunks. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Han, X.; Shen, T.; Meng, Z.; Chen, K.; Yao, X.; Cao, Y.; Castro-García, S. Natural Frequency Identification Model Based on BP Neural Network for Camellia Oleifera Fruit Harvesting. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 237, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravčík, Ľ.; Vincúr, R.; Rózová, Z. Analysis of the Static Behavior of a Single Tree on a Finite Element Model. Plants 2021, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaher, H.; Haddar, M.; Fakhfakh, T.; Mâalej, A. Finite Elements Modeling of Olive Tree Mechanical Harvesting Using Different Shakers. Trees 2013, 27, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcham, D.C.; Au, S.-K. Identifying Modal Properties of Trees with Bayesian Inference. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 316, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Garcia, S.; Sola-Guirado, R.R.; Gil-Ribes, J.A. Vibration Analysis of the Fruit Detachment Process in Late-Season ‘Valencia’ Orange with Canopy Shaker Technology. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 170, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-García, S.; Blanco-Roldán, G.L.; Gil-Ribes, J.A. Vibrational and Operational Parameters in Mechanical Cone Harvesting of Stone Pine (Pinus pinea L.). Biosyst. Eng. 2012, 112, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Láng, Z.; Csorba, L. A Two Degree of Freedom Damped Fruit Tree Model. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2015, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, K.; Niu, Z.; Mu, H.; Lan, W.; Zhang, X.; Xin, D.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Y. Vibration Harvesting Process of Olive Trees Based on Response Surface Methodology and Rigid-Flexible Coupling Simulation. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2025, 18, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, J. New Method for Multibody Dynamics Based on Unknown Constraint Force. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2024, 67, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, L.X.; Fourcaud, T.; Lac, P.; Stokes, A. A Generic 3D Finite Element Model of Tree Anchorage Integrating Soil Mechanics and Real Root System Architecture. Am. J. Bot. 2007, 94, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Rahardjo, H.; Tsen-Tieng, D.L. Stability Analysis of Laterally Loaded Trees Based on Tree-Root-Soil Interaction. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanahama, T.; Chalermsin, C.L.; Sato, M. Mechanical Instability of Heavy Column with Rotational Spring. J. Mech. 2023, 39, 480–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, P.; Yan, B.; Wang, M.; Lei, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, F. Three-Finger Grasp Planning and Experimental Analysis of Picking Patterns for Robotic Apple Harvesting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Kang, L.; Rao, H.; Liu, M. Design and experiment of multichannel camellia-fruit-picking device. Eng. Agríc. 2023, 43, e20220038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ding, D.; Cui, B.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, E.; Liu, Y.; Cao, C. Design and Experiment of Vibration Plate Type Camellia Fruit Picking Machine. Biol. Eng. 2022, 15, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).