Abstract

Photosynthesis (PS) is the cornerstone of crop productivity, directly influencing yield potential. Photosynthesis remains an underexploited target in soybean breeding, partly because field-based photosynthetic traits are difficult to measure at scale. Also, it is unclear which reproductive stage(s) provide the most informative physiological signals for yield. Few studies have evaluated soybean PS in elite germplasm under field conditions, and the integration of chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) with UAV imaging for PS traits remains largely unexplored. This study evaluated genotypic variation in photosynthetic and canopy traits among elite soybean germplasm across environments and developmental stages using CF and UAV imaging. Linear mixed-model analysis revealed significant genotypic and G×E effects for yield, canopy and several photosynthetic parameters. Broad-sense heritability (H2) estimates indicated dynamic genetic control, ranging from 0.12 to 0.77 at the early stage (S1) and 0.20–0.81 at the mid-reproductive stage (S2). Phi2, SPAD and FvP/FmP exhibited the highest heritability, suggesting their potential as stable selection targets. Correlation analyses showed that while FvP/FmP and SPAD were modestly associated with yield at S1, stronger positive relationships with Phi2, PAR and FvP/FmP emerged during S2, underscoring the importance of sustained photosynthetic efficiency during pod formation. Principal component analysis identified photosynthetic efficiency and leaf structural traits as key axes of physiological variation. UAV-derived indices such as NDRE, MTCI, SARE, MExG and CIRE were significantly correlated with CF-based traits and yield, highlighting their utility as high-throughput proxies for canopy performance. These findings demonstrate the potential of integrating CF and UAV phenotyping to enhance physiological selection and yield improvement in soybean breeding.

1. Introduction

Soybean is a globally important food crop, ranking behind wheat, rice, maize and sugarcane in global production [1]. It serves as a crucial source of vegetable protein and oil. To meet the growing global demand for soybean, the rate of yield improvement must double to avoid further expansion of production areas [2]. Photosynthesis is the fundamental physiological process driving plant growth and development. Photosynthetic efficiency is one of the main determinants for nutrient biomass and seed yield [2,3]. Crop yield overall is an output of complex biotic and abiotic factors and their interactions [4,5]. Although practical yield improvement can also arise from advances in areas such as disease resistance, drought tolerance and nutrient-use efficiency, enhancing the efficiency of light energy conversion remains a fundamental route to increasing potential yield ceilings. Future gains in crop productivity will substantially depend on enhancing net photosynthesis and energy transduction efficiency. Leveraging natural variation in photosynthetic capacity offers an opportunity to breed genotypes with enhanced carbon assimilation and yield potential under variable environments [4,5,6].

Soybean, as a typical C3 crop, has a relatively low photosynthetic efficiency compared to C4 crops, hence limiting its seed yield [7]. Multiple studies have shown that improving photosynthetic efficiency is a promising strategy for increasing soybean yield potential, especially in the context of climate change [8,9]. Other than genetic characteristics of the plant (genotype), photosynthesis also depends upon the influence and constraints of environmental parameters including light, temperature, CO2, moisture, etc. Thus, it is important to evaluate the variation in photosynthetic performance in natural and breeding populations to utilize this variability to improve seed yield in soybean [10,11,12,13]. Soybean has ample genetic variability for multiple photosynthetic traits such as net photosynthetic rate [14], transpiration rate [15], stomatal conductance [16], chlorophyll content (SPAD) [14,17], PSII efficiency [18], etc. There have been limited studies which evaluated such relationships under field conditions and most have shown low to moderate correlation with seed yield due to complexity of yield formation in agricultural settings. Many studies have focused on the reproductive (R) stage, provided its stronger association with final productivity [10,11,12,13]. Furthermore, it is important to study the photosynthesis-related parameters during different growth stages within the reproductive phase (i.e., early reproductive to mid-reproductive and late reproductive stages) to explore their dynamic relationships with seed yield under field conditions [19]. Such comparative evaluations can give insights into temporal relationships between the allocation of photosynthetic energy and final yield.

Chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) is a powerful non-destructive approach to assess photosynthetic performance as related to light energy capture, distribution and photosystem II (PSII) efficiency in both controlled and field conditions [20,21]. Screening diverse and elite soybean germplasm for photosynthetic traits is critical for capturing valuable physiological variation that can be utilized to improve photosynthetic efficiency and, ultimately, yield potential [13,16]. However, while canopy photosynthetic performance during R-stages is generally associated with final yield, the expression and stability of these traits are strongly modulated by environmental conditions and specific developmental stages. Consequently, the strength and consistency of trait–yield relationships can vary substantially across locations and growth phases. However, identifying the growth stages and physiological traits that are most informative for predicting yield performance across environments is crucial for developing effective trait-based selection strategies in modern soybean breeding [19,22,23]. In recent years, advances in high-throughput phenotyping (HTP) have enabled rapid, plot-scale assessment of canopy level physiological traits including those related to photosynthesis [24]. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) using RGB and multispectral sensors allow indirect quantification of vegetation indices related to canopy photosynthetic capacity, pigment content and structural attributes [24,25,26]. Integrating UAV-derived indices with ground based physiological and agronomic measurements can enhance yield prediction accuracy and support the development of scalable selection pipelines in soybean breeding [27]. For the breeding context, it is critical to determine which growth stages in soybean are most strongly associated with final yield and which physiological traits best reflect those valuable relationships. Physiological parameters that consistently correlate with yield can serve as proxies for complex productivity traits enabling early yield prediction and targeted parent selection [28,29,30]. The combined use of physiological traits, UAV-derived canopy features and yield data across environments and growth stages provides a novel opportunity to dissect the physiological determinants of yield potential in soybean.

Despite the central role of PS in yield formation, several critical gaps remain. Most field studies on soybean focus on a single reproductive stage, mostly R4-R6 [12,14,15,16]. It limits the understanding of how PS traits expressed earlier in the reproductive phase (R1 to R4) contribute to yield potential across environments. Moreover, relatively few studies have evaluated PS in elite germplasm, where physiological variation is narrower and more environment-sensitive [23,31,32,33]. Similarly, the integration of CF traits with UAV-based canopy indices for scalable, field-based phenotyping has not been systematically assessed in soybean [28,34]. Consequently, the heritability, stability and stage dependent predictive value of key PS traits under field environments remain poorly characterized in soybean. It is critical to address these questions for developing practical frameworks that connect photosynthetic efficiency with breeding for high and more resilient soybean varieties. The key objectives of this study are to (i) quantify phenotypic variation and heritability for agronomic, photosynthetic and canopy traits across environments and growth stages; (ii) identify stage-specific relationships between chlorophyll fluorescence and other physiological parameters with seed yield; (iii) assess the utility of UAV-derived vegetation indices in capturing variation in photosynthetic and yield related traits; and (iv) explore the multivariate structure of traits inter-relationships to identify physiologically meaningful targets for soybean breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Experimental Design

A total of 108 advanced soybean breeding lines, including maturity group (MG) III late (36 lines), MG IV early (22 lines) and MG IV late (50 lines), were selected from advanced yield trials at the University of Missouri-Fisher Delta Research, Extension, and Education Center, Portageville (MU-FDREEC). The field trials were conducted at two distinct locations (environments) in Southeast Missouri, namely LEE and FISK in 2024 (Figure 1). These two environments differ in their soil nutrition profiles and weather parameters. The experimental design was a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with two replications per location. Each plot consisted of 4 rows (2.1 m length and 0.76 m spacing). The seed rate used was 300,000 seeds per hectare.

Figure 1.

Location of Missouri, USA and two Missouri field environments used in this study—LEE (36.403 N, 89.595 W) in Pemiscot County and FISK (36.802 N, 90.211 W) in Butler County.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Physiological Data Collection

The photosynthetic data was collected at two different reproductive growth stages, i.e., R1-R2 (early reproductive stage—S1) and R3-R4 (mid-reproductive stage—S2). These stages were selected due to their relevance to yield formation [12,25] and potential for genotype–environment (G×E) interaction effects on photosynthetic efficiency. Measurements were performed using MultispeQ V 2.0 [35] on clear days between 10.00 a.m. and 2.00 p.m. Measurements were taken on upper canopy leaves using standardized protocol ‘Photosynthetic RIDES 2.0’. Three representative plants from each plot were measured from the middle two rows to avoid the border effect from adjacent plots. The photosynthesis and canopy related parameters used for further analyses are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of multiple traits including photosynthesis-related parameters measured using MultispeQ V2.0 in the study.

2.2.2. Agronomic Data Collection

At each location, the final Seed Yield (kg/ha) was recorded for each plot by harvesting the middle two rows of the plot to avoid the border effect on seed yield performance. Final yield was normalized to 13% moisture to enable cross-location comparisons. Plant Height (PH) was measured at R6-R7 growth stage from base to the tip of the main stem (cm), averaging three plants per plot. Lodging was assessed at the R7-R8 stage using a scale of 1–5 (1: fully upright, 5: completely lodged). Hundred seed weight was recorded after harvest and cleaning seed using weight of random hundred seed samples in grams for each plot.

2.2.3. UAV Data Collection

UAV data were collected using a DJI Mavic 3M system (DJI, Shenzhen, China), equipped with both RGB and multispectral imaging sensors (UAV flights and CF data collection details provided in Supplementary Table S1). The RGB sensor captures visible imagery at high spatial resolution. The multispectral camera includes four spectral bands- green, red, red edge and near-infrared (Table 2). A built-in sunlight sensor records real-time irradiance for radiometric calibration and consistency across flight sessions. Flights were conducted on the same days as chlorophyll fluorescence measurements at both locations. The flight paths followed an overlapping grid pattern to ensure complete plot coverage and accurate 3D surface reconstruction. All flights were performed under uniform lighting conditions around solar noon to minimize shadow effects and variation in reflectance. Image datasets were processed in Pix4DMapper (Pix4D, Lausanne, Switzerland) to generate georeferenced orthomosaics for both RGB and multispectral data. Default settings were applied for most processing parameters, with minimum adjustments to ensure comparable ground sampling resolution across datasets. The resulting orthomosaics were exported for further analysis. Subsequently, Quantum GIS v.3.44.3 software (QGIS Development Team, Open-Source Geospatial Foundation, GNU GPLv2+, Switzerland) was used to delineate experimental plots, grid the imagery and extract spectral reflectance values for each band. From this data, multiple vegetation indices were computed for each plot across both locations, including those related to canopy greenness, pigment content and photosynthetic activity (formulas and references provided in Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

UAV platform and multispectral sensor specifications.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

We deployed linear mixed-effects models (LMM) using the lmer() function from lme4 package [36] in R software [version 4.5.2] to assess the significance of genotype, location, growth stage and their interactions on the traits [37]. Fixed effects included genotype (G), growth stage (S), environment (E) and maturity group (MG). Random effects accounted for variability due to G×E interaction, maturity group-by-environment interaction (MG×E) and replication (R) nested within environment. Residual variance (e) captured unexplained variation.

The linear mixed-effects model can be expressed as follows:

where

Yijkl = μ + Gi + Sj + MGk + El + (G×E)il + (MG×E)kl + Rm(El) + eijkl

- Yijkl: Yield for the ith genotype in the jth stage, kth maturity group and mth replication in lth environment.

- μ: Overall mean.

- Gi: Effect of the ith genotype.

- Sj: Effect of the jth growth stage (only for physiological traits).

- MGk: Effect of the kth maturity group.

- El: Effect of the lth environment.

- (G×E)il: Effect of ith genotype and lth environment interaction.

- (MG×E)kl: Effect of kth maturity group and lth environment interaction.

- Rk(El): Effect of the mth replication within lth environment.

- eijk: Residual error.

Prior to statistical analyses, parametric assumptions were evaluated by testing normality of residuals using the Shapiro–Wilk test and a visual assessment. Biologically implausible outlier values were carefully removed before analysis to ensure valid inference from the linear mix-effects framework.

Broad-sense heritability (H2) was calculated using the variance components derived from the LMM analysis [38], when genotype (G) was treated as random. The estimation represents the proportion of total phenotypic variation attributable to genotypic variation. For the agronomic traits (yield, HSW, plant height), H2 was calculated separately for each environment using the following formula:

For the physiological traits, stage-specific heritability was calculated for each stage (S1 and S2) within each environment to capture the dynamic genetic control observed [39]:

where

- is the genotypic variance extracted from the LMM when G is treated as a random effect

- is the residual variance (or error variance)

- is the number of replications

To quantify the relationships between physiological and agronomic traits, Pearson pairwise correlation analysis was performed. The analysis was conducted in two distinct steps to evaluate the stage-dependent associations. First, we performed pairwise correlations analysis for all ground-measured photosynthetic and morpho-physiological traits for both the S1 and S2 stages with seed yield. This comparison was essential to identify if the impact of photosynthetic performance on yield potential varied across developmental stages. Later, we conducted an integrated phenotypic correlation analysis for the S2 stage to quantify the associations among all three datasets: UAV-derived indices, ground-measured photosynthetic traits and key agronomic traits (including yield). Correlation matrices were visualized using heatmaps generated with the ggplot2 package [40] and the corrplot R package [41], enabling clear representation of the magnitude and direction of all relationships.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was utilized to explore the structure of the phenotypic variation, reduce data dimensionality and identify major axes of variation within the high-throughput datasets. PCA was conducted using the factoextra R package [42] in three distinct analyses. For ground-based traits, separate PCAs were performed on the full set of physiological and photosynthetic traits for each developmental stage (S1 and S2). These analyses identified the primary components driving variation in canopy function at specific growth periods. Moreover, a dedicated PCA was conducted on all UAV-derived vegetation indices and physiological traits collected at the S2 stage. Then, a variable circle biplot was generated to determine their contributions. This analysis was used to understand the main sources of variability among the indices and their collective relationship with photosynthetic traits and seed yield. For all PCA analyses, the resulting components were visualized using variable circle plots (biplots) to illustrate the contribution and loading of each original trait onto the newly defined axes of variation.

3. Results

3.1. Phenotypic Variation and Heritability of Agronomic and Physiological Traits

Agronomic traits like seed yield, hundred seed weight (HSW), plant height and lodging showed highly significant genotypic variation (p < 0.0001) in MU-FDREEC breeding lines (Table 3 and Table 4), indicating a strong genetic control for each trait. G×E interactions were also significant for yield, plant height and lodging, indicating that the performance of breeding lines varied across LEE and FISK environments. LEE showed higher mean yield (4306.4 kg/ha) compared to FISK (3794.8 kg/ha). Distribution of yield among elite experimental lines was also bigger at LEE (1993 to 5908 kg/ha), whereas relatively less variability was observed at FISK (2616 to 4973 kg/ha). For HSW (only in Fisk), we observed significant genetic variability (p < 0.0001), which ranged from 12.1 to 18.1 g overall. Plant height overall ranging from 21 to 52 cm showed more variability in LEE (CV of 15.9) compared to FISK (CV of 12.9) (Table 3). Additionally, the maturity group (MG) and its interactions with the environment (MG×E) were also significant for yield, HSW and plant height.

Table 3.

Summary statistics (Mean, range, CV and H2) for all the traits studied, presented by environment (location) and development stage.

Table 4.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for Agronomic and Physiological Traits showing main effects of Genotype (G), Developmental Stage (STAGE) and Maturity Group (MG), and interactions effects of G and MG with environment (E).

Considerable variations for various chlorophyll fluorescence, environmental and canopy parameters were observed in our experiments across locations and developmental stages (Table 3, Figure S2). Phi2, PAR and leaf thickness showed significant genotypic variability (p < 0.05). The environment had a significant effect on almost all photosynthetic and canopy traits (p < 0.05) including FvP/FmP, NPQt, PAR, Phi2, SPAD, leaf thickness and LEF (Table 4). Strong G×E interactions were observed for key photosynthetic and canopy traits including FvP/FmP, PAR, SPAD and LEF (p < 0.05). Developmental stage (S1 and S2) effects were highly significant (p < 0.01) for several photosynthetic and canopy traits such as FvP/FmP, NPQt, PAR, Phi2, qL and leaf thickness (Table 4). Surprisingly, Phi2 and PAR were the only photosynthetic and canopy traits, respectively, that showed significant impact of maturity group (p < 0.05) in our experiment (Table 4).

Yield exhibited moderate to high broad-sense heritability (H2 = 0.62–0.77), with higher values observed in FISK, suggesting strong genetic control. In physiological traits, SPAD showed high heritability (H2 = 0.67–0.69) at the S1 stage, whereas Phi2 exhibited highest heritability (H2 = 0.70–0.81) during the S2 stage. Among other photosynthetic traits, maximum quantum yield of PSII (FvP/FmP) and linear electron flow (LEF), demonstrated moderate to high heritability, particularly at the S1 stage (0.63–0.76 and 0.61–0.66, respectively). NPQt and PAR showed varied heritability across stages and environments. Notably, PAR heritability was higher in LEE during both stages (H2 = 0.77–0.80), however it dropped significantly at the S2 stage in FISK (H2 = 0.20). The effective quantum yield of PSII (Phi2) exhibited higher heritability at both stages, especially the S2 stage (H2 = 0.70–0.81). Leaf thickness also showed substantial heritability overall (H2 = 0.63–0.74). It underscores their potential as stable selection targets. The coefficient of variation (CV) was generally higher for traits like NPQt, gH+ and leaf thickness indicating substantial phenotypic variability among genotypes and strong environmental sensitivity. Conversely, traits such as FvP/FmP and SPAD showed lowest CVs, reflecting more uniform expression.

3.2. Stage-Dependent Relationships Between Photosynthetic Traits and Seed Yield

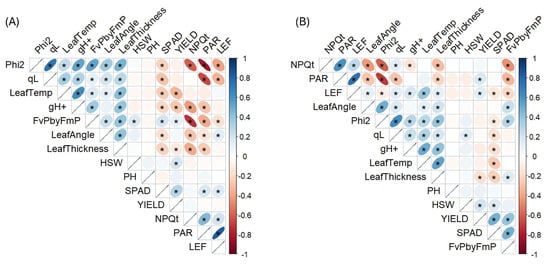

We next investigated the correlations between CF parameters with seed yield, since photosynthesis is one of the major determinants of yield. Pearson correlation was calculated among yield and photosynthetic traits during both developmental stages (S1 and S2) (Figure 2). During the S1 stage (Figure 2A), several photosynthetic traits showed significant (p < 0.05) correlation with yield including FvP/FmP (r = 0.19), gH+ (r = −0.24) and SPAD (r = 0.34). FvP/FmP was also significantly correlated with HSW (r = 0.22, p < 0.05). Additionally, leaf temperature (r = −0.31) and thickness (r = −0.17) also demonstrated significantly negative correlations with yield (p < 0.05). SPAD showed a significant positive relationship with FvP/FmP (r = 0.25), PAR (r = 0.21) and LEF (r = 0.19). NPQt showed highly negative relationships with most of photosynthetic and leaf morphological traits, except for PAR (r = 0.49) and LEF (r = 0.98). Phi2 also showed very high correlation with qL (r = 0.81).

Figure 2.

Stage-specific Pearson correlation plots between photosynthetic and morpho-physioloigcal traits with yield-related traits. (A) Early reproductive stage (S1 stage) and (B) Mid-reproductive stage (S2 stage). Narrower and more elongated ellipses represent stronger correlations, while wider and more circular ellipses represent weaker correlations. Blue and red colors indicate positive and negative relationships, respectively. Asterisks (*) indicate statistically significant correlations at p < 0.05.

During the S2 stage, several photosynthetic traits were strongly correlated with yield (Figure 2B). These include positive relationship with FvP/FmP (r = 0.40), SPAD (r = 0.48), LEF (r = 0.15), PAR (r = 0.18) and a significant negative correlation with leaf thickness (r = −0.22). Interestingly, qL showed a significant positive association with HSW (r = 0.14), an important seed yield component in soybean. Light intensity (PAR) showed consistent negative relationships with photosynthetic traits (FvP/FmP, Phi2, qL), with r = −0.44 to −0.98 and leaf thickness (r = −0.18, p < 0.05). NPQt exhibited strong negative correlations with FvP/FmP (r = −0.35) and Phi2 (r = −0.52). Leaf thickness showed positive correlations with Phi2, FvP/FmP, qL and gH+ (r = 0.15 to 0.42), whereas significantly negative associations with SPAD, NPQt and PAR (r = −0.22 to −0.35).

3.3. Multivariate Analysis of Physiological and Spectral Trait Variation

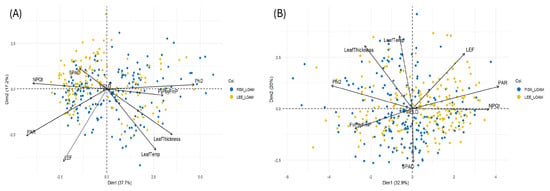

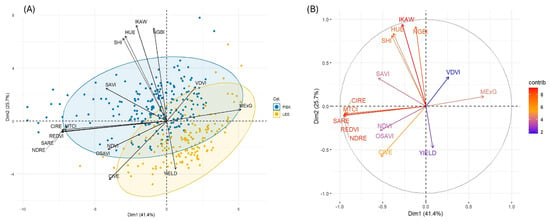

To understand how different trait combinations drive physiological varations during different reproductive stages, multivariate PCA was performed (Figure 3). The PCA of physiological and canopy traits at the S1 stage across our elite soybean germplasm evaluated across two environments revealed that the first two components captured over 55% of the total variation (PC1: 37.7%; PC2: 17.2%). PC1 was primarily associated with Phi2, PAR, NPQt and leaf thickness (Figure 3A). Lines with higher PC1 scores exhibited enhanced photosynthetic performance and efficient energy management. PC2 influenced mainly by LEF, PAR and leaf thickness, appeared to capture variation in electron transport capacity and thermal regulation (Figure 3B). PCA for photosynthetic and other physiological traits at the S2 stage revealed two dominant axes of variation. PC1 (~33% variance explained) was primarily driven by traits associated with light interception, photochemical efficiency and photoprotection, including PAR, Phi2, NPQt and FvP/FmP. In contrast, PC2 (20% variance explained) was characterized by strong contributions from leaf thickness and temperature, LEF and SPAD. Together PC1 and PC2 explained ~53% of total variations observed.

Figure 3.

Principal component analysis (PCA) comparing variations in photosynthetic and morpho-physiological traits at (A) stage S1 and, (B) stage S2.

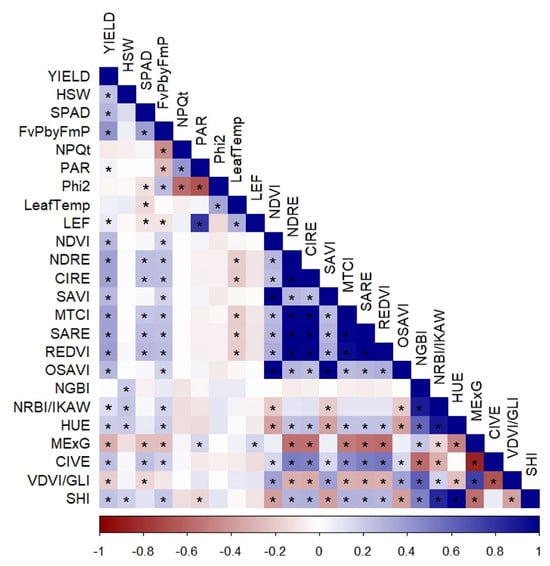

As we observed more significant associations of morpho-physiological traits with yield and its components, we conducted multi-level scale correlation analysis (Figure 4) to understand overall relationships at this crucial R-stage. It includes UAV-derived vegetation indices in addition to agronomic (yield, HSW), photosynthetic and morpho-physiological parameters. Correlation analysis further supported these associations, revealing significant positive relationships between UAV-derived indices and ground-measured photosynthetic traits and yield (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation heatmap among yield, photosynthetic traits and UAV-derived vegetation indices (both Multispectral and RGB) at the S2 stage. Asterisks (*) indicate significant correlations at p < 0.05.

Next, we deployed PCA to understand patterns of variation in UAV-derived indices observed at the S2 stage (Figure 5). PCA revealed the first two components captured 67.1% of the total variation (PC1: 41.4% and PC2: 25.7%). PC1 was primarily influenced by SARE, NDRE, REDVI, CIRE, MTCI and MExG. In contrast, PC2 was mainly dominated by vegetation indices such as IKAW, NGBI, HUE, SHI and CIVE. Overall, indices like MTCI, NDRE, SARE, CIRE and IKAW showed the highest variability contribution in our study dataset.

Figure 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of UAV-derived indices (A) at the S2 stage, and (B) corresponding variable contribution plot.

4. Discussion

4.1. Genetic Control and Developmental Variation in Photosynthetic Traits

Photosynthesis is one of the most important and fundamental physiological processes. It directly impacts plant growth, development, energy conversion efficiency and ultimately, seed yield potential. Enhancing the efficiency of light energy utilization is recognized as a key avenue for boosting crop productivity [43,44]. As a C3 species, soybean’s photosynthetic capacity is believed to possess substantial untapped potential for improvement in conversion efficiency, a key constraint on final yield potential. Therefore, improving photosynthetic efficiency has emerged as a primary breeding objective to unlock higher yield potential, especially in C3 crops like soybean [29,31,45]. The chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) parameters can reflect the light energy absorption, utilization and dissipation processes of PSI and PSII [46]. CF parameters have been widely used in research of plant photosynthesis and crop improvement in many species including soybean [18,47,48,49].

Wide phenotypic variation in agronomic, photosynthetic and canopy traits analyzed in this study was primarily attributable to four major factors: genotype (G), environment (E), developmental stage (S) and significant interactions (G×E and MG×E). Across two field environments, seed yield exhibited relatively higher broad-sense heritability (H2 = 0.62–0.77), with higher values in the FISK environment. Other agronomic traits like HSW and plant height also showed high heritability (H2 = 0.93 and 0.67–0.80, respectively). We observed highly significant genotypic effects (p < 0.0001) for yield, HSW, plant height and lodging, confirming that these agronomic traits are largely under genetic control [50]. However, significant G×E interactions for yield, plant height and lodging indicate that performance of MU-FDREEC elite breeding lines varies across environments, underscoring the need for multi-environment testing in breeding programs [51,52]. The evaluated lines represented three different maturity groups (MG), III late, IV early and IV late. We observed that the effects of both MG and its interactions with environment (MG×E) were significant for yield, HSW and plant height. This highlights the well-established importance of tailoring breeding strategies to specific maturity groups and target environments [51,53,54].

For photosynthetic and canopy traits, stage (developmental) effects were highly significant (p < 0.005) for FvP/FmP, NPQt, PAR and Phi2 and leaf thickness, while qL also varied significantly (p < 0.05) across stages. A higher qL value means a larger fraction of open PSII reaction centers, which is crucial for electron transport and rate of CO2 assimilation. It reflects the dynamic nature of photosynthetic regulation across reproductive stages [19,55,56]. Environmental effects were significant for nearly all photosynthetic and canopy traits (Table 4), underscoring their strong environmental sensitivity. Among the photosynthetic and canopy traits, Phi2 and PAR showed significant genotypic variation (p < 0.05), while SPAD and LEF exhibited highly significant G×E and environmental effects. Notably, we did not observe significant genotypic effects for other photosynthetic traits including FvP/FmP, NPQt and LEF, suggesting that these traits may be more strongly influenced by environmental or developmental factors than by genetic differences among the tested germplasm [30,33,57,58]. These results look plausible due to possible limited genetic diversity among elite breeding lines for physiological traits, as they have been selected for yield and agronomic performance. This finding provides unique field-based evidence that PSII-related photosynthetic traits in elite germplasm are largely environmentally driven, helping explain why results from diversity association panels do not always translate directly to breeding populations. Therefore, this outcome collectively emphasized the importance of considering both genetic and environmental factors, as well as developmental timing, when targeting improved photosynthetic performance and yield stability in soybean breeding program [19].

To identify effective physiological targets for breeding and to assess the genetic potential of elite soybean lines for improved photosynthesis and canopy architecture, it is essential to quantify the heritability (the relative contribution of genetic effects versus non-genetic effects) of the relevant traits [59,60]. In our study, broad-sense heritability (H2) for morpho-physiological traits ranged from 0.12 to 0.77 during the S1 stage and 0.20 to 0.81 during the S2 stage. The genetic control of photosynthetic traits appeared to be both dynamic and stage-dependent in this elite soybean germplasm. In general, we observed lower H2 values at the S1 stage compared to the S2 stage, indicating that environmental influence was relatively stronger in the early reproductive phase [19]. This developmental pattern suggested that the relative contributions of genetic background and environment to trait expression shifts over the crop growth stages [33,55,56]. In contrast, the heritability of leaf thickness remained consistently high across both developmental stages and environments, suggesting a stable genetic basis with limited environmental modulation [61,62]. Among photosynthetic parameters, FvP/FmP, NPQt, Phi2 and LEF demonstrated moderate to high heritability, particularly at the S2 stage. These findings highlighted that later developmental stages may provide more reliable windows for evaluating soybean photosynthetic efficiency under field conditions [30,55,56]. This stage-dependent shift in genetic control represents a novel insight, highlighting that S2 is a more genetically informative window for photosynthesis-based selection in elite soybean germplasm. By contrast, canopy light interception (PAR) showed greater environmental sensitivity, showing high heritability in LEE (H2 = 0.77–0.80) but dropped significantly at the S2 stage in FISK (H2 = 0.20). It underscores the context-dependent regulation of light interception under variable field conditions. Several other photosynthetic and canopy-related traits including qL, FvP/FmP, gH+ and PAR exhibited lower or variable heritability across growth stages, which is to be expected given the strong influence of fluctuating environmental and microclimatic factors on these dynamic processes. Similar trends have been widely reported in other studies, where G×E interactions substantially reduced the heritability of photosynthetic parameters measured under field conditions [15,56,57]. The observed temporal shift or variation in heritability highlights the importance of selecting optimal phenotyping windows for complex photosynthesis-related traits [19,34,56]. Measuring these traits during phases of low H2 may compromise the selection efficiency. Therefore, targeting stages where genetic effects predominantly drive physiological trait variation can improve the traits’ repeatability and breeding precision [56,63]. The relatively high H2 and significant genetic variability (p < 0.05) observed for Phi2, PAR and leaf thickness indicated that these parameters may serve as promising physiological indicators in breeding programs aiming to enhance photosynthetic efficiency and yield potential in soybean.

4.2. Trait Interactions and Multivariate Physiological Patterns Across Stages

Building on the observed genetic variability and stage-dependent H2 patterns, we next examined how morpho-physiological traits were associated with seed yield across developmental stages. Understanding these relationships is critical for identifying physiological and canopy morphological indicators that can reliably predict yield performance in breeding populations [56,57,62]. Interestingly, the strength of various trait associations varied between the S1 and S2 stages (Table 5), suggesting that the physiological determinants of yield may shift as plants transition from flowering to pod development [19,55]. During the S1 stage, we observed modest but significant positive associations (p < 0.05) of yield with FvP/FmP and SPAD and a negative relationship with gH+. This suggests that canopy photosynthetic capacity and chlorophyll status during flowering can influence subsequent biomass accumulation and sink establishment [44]. The negative association of leaf thickness and temperature with yield further implies that excessive heat load/thicker leaves may limit early canopy photosynthetic capacity under field conditions [64,65]. In contrast, during the S2 stage, several traits, particularly FvP/FmP, Phi2, SPAD, LEF and PAR, demonstrated stronger positive correlations with seed yield. This pattern indicates that maintenance of photochemical efficiency and light utilization during active pod formation/filling plays a more decisive role in determining final yield potential [46,56,57]. Notably, qL also displayed a positive relationship with HSW, linking sustained PSII openness with reproductive sink development [49,59]. These findings, in combination with observed moderate to high H2 of Phi2 and PAR, reinforce their potential as physiologically meaningful and genetically tractable selection targets. Collectively, this developmental divergence in trait–yield relationships highlights the importance of temporal context in evaluating photosynthesis-related traits. A key insight from this study is the clear physiological transition between S1 and S2, showing that mid-reproductive PS performance, rather than early flowering physiology, is the more decisive determinant of final yield in elite lines [19,55].

Table 5.

Summary of key significant correlations (p < 0.05) of physiological and canopy traits with yield and hundred seed weight (HSW) at two reproductive stages (S1 and S2).

PCA further clarified the major sources of physiological variability among the MU-FDREEC elite breeding lines across both reproductive stages. At the S1 stage variation along PC1 was driven largely by Phi2, PAR, NPQt and leaf thickness, reflecting differences in photochemical efficiency, energy dissipation and leaf morphology. Lines with higher PC1 tend to exhibit greater photosynthetic efficiency and energy use balance. These traits may support early canopy establishment and assimilate supply for reproductive initiation. The PC2 axis, shaped by LEF, leaf temperature and PAR, captured variation in electron transport and thermal regulation, underscoring genotypic differences in the capacity to maintain photosynthetic efficiency under fluctuating field conditions. During the S2 stage, PCA revealed a shift in trait coordination. PC1, dominated by PAR, Phi2, NPQt and FvP/FmP, representing variation in light interception and photoprotective efficiency. However, PC2 was influenced by leaf thickness, temperature, LEF and SPAD, reflecting a balance between structural-thermal resilience and chlorophyll content. These components distinguished genotypes by their contrasting strategies for light-use efficiency and canopy microclimate regulation. This shift in multivariate structure between stages provides novel evidence that elite soybean lines reorganize their photosynthetic and canopy strategies dynamically during the reproductive period, which has rarely been quantified in field breeding material for these soybean traits. Notably, seed yield contributed minimally to the primary components. This observation was consistent with modest correlation patterns, highlighting a fundamental challenge in field phenotyping—yield is an outcome of cumulative, whole-season processes. Factors beyond single time point leaf-level photosynthesis, such as stand establishment (germination) and plant density in each plot, biomass partitioning and overarching influence of soil, management and localized weather micro-variability, all act as major determinants of final yield [12,22,51,66]. These integrative, non-photosynthetic processes often mask the direct physiological signal from a single time point. Together, these multivariate patterns suggested that elite soybean germplasm harbors considerable physiological diversity in how genotypes manage light energy and canopy structure across field environments.

4.3. UAV-Based Phenotyping and Implications for Soybean Breeding

The UAV-based analysis provided complementary insights into canopy-level physiological variation among elite soybean lines during the S2 stage (R3-R4). The first two principal components of the UAV-derived vegetation indices explained a substantial proportion of variation (67.2%). This underscores the capacity of high-resolution spectral imaging to capture meaningful physiological and structural diversity under field conditions [66]. PC1 was dominated by indices such as SARE, NDRE, REDVI, CIRE, MTCI, MExG, reflected variation in canopy greenness, chlorophyll concentration and photosynthetic activity (Figure 5 and Figure S3). These parameters are closely related to source strength and pigment variation, suggesting their relevance as proxies for overall canopy photosynthetic efficiency. PC2 was characterized by IKAW, NGBI, HUE, SHI and CIVE, which were oriented orthogonally to PC1 (Figure 5A,B), indicating capture of major independent variation related to canopy structure, coloration and reflectance. This likely reflects genotypic differences in canopy architecture and light use strategies among breeding lines. Notably, yield aligned moderately with a couple of indices (VDVI and MExG), indicating that the spectral features related to canopy greenness and pigment intensity were modestly associated with final productivity (Figure S3) [67]. A notable outcome is that these multispectral indices captured physiologically relevant canopy variation more effectively than leaf-level CF traits during S2. It indicates that canopy scale imaging may provide stronger stage-specific predictive power in elite breeding germplasm [68].

Consistent with the multivariate patterns, the correlation analysis (Figure 3) revealed significant associations between UAV-derived indices and ground-measured physiological traits. Indices sensitive to chlorophyll and canopy greenness (NDRE, MTCI, CIRE and HUE) showed strong positive correlations with both SPAD and FvP/FmP and critically with yield. This suggests that UAV imaging can effectively capture canopy features linked to photosynthetic performance and productivity [67,68]. Furthermore, indices reflecting canopy color and structural variation demonstrated informative relationships with physiological parameters—IKAW correlated positively with yield, HSW and FvP/FmP; MExG exhibited negative associations with yield, SPAD and FvP/FmP but was positively linked to light interception (PAR, LEF); MExG may be related to canopy structure or density in a way that hinders optimal efficiency; and SHI was positively related to yield, HSW and FvP/FmP, while negatively associated with PAR. Together, these patterns demonstrate that UAV imaging provides a scalable means to quantify canopy-level proxies for photosynthetic performance and yield related traits in soybean [68,69,70]. Importantly, the ability of UAV indices to discriminate physiological variation even within genetically narrow germplasm reflects a novel contribution, highlighting that aerial imaging can detect subtle, breeding-relevant trait variations previously challenging to capture.

The ability to detect genotypic variation in both canopy vigor and colorimetric attributes during critical reproductive stages has the potential to complement direct physiological measurements [68,69]. While promising, the present study was conducted using elite breeding lines, which may have constrained the observed genetic diversity in physiological and canopy traits as we discussed above. Moreover, UAV data were collected from only one growth stage, due to logistic constraints. Future efforts combining multi-environmental time-series UAV datasets (complementary hyperspectral/thermal information), diverse germplasm panels and environmental covariates (soil and weather data) will be critical to enhance the robustness and applicability of these phenotypic associations. Overall, these findings demonstrate that UAV imaging can substantially enhance selection efficiency in soybean breeding programs. When integrated with genomic and environmental data, these UAV-derived traits could enable earlier, non-destructive identification of superior genotypes exhibiting optimal canopy performance and sustained photosynthetic activity under dynamic field conditions [71]. Collectively, this study delivers a novel stage-resolved framework showing when and how leaf-level CF and UAV canopy indices offer stronger biological signals for yield evaluation in elite soybean material.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that photosynthetic and canopy traits vary substantially across reproductive stages and environments in elite soybean germplasm, and their relevance to yield is strongly stage and environment dependent. Early reproductive measurements (S1) showed limited physiological variation and weak associations with yield, whereas the mid-reproductive stage (S2) revealed substantial genetic variation, higher heritability and stronger relationships with yield. UAV-derived multispectral indices (NDRE, MTCI, SARE) emerged as robust canopy level indicators of vigor and were more strongly aligned with yield at S2. It underscores their potential as scalable high-throughput proxies for physiological performance. By integrating CF with UAV multispectral imaging across multiple environments, this work identified the stages’ specific physiological windows and canopy indices that are most informative for yield evaluation in elite soybean germplasm. We acknowledge that measurements were restricted to two reproductive stages across two environments; additional timepoints (e.g., R5-R6) may capture late season dynamics in source–sink relationships. Future work incorporating multi-environment CF measurements, multiple UAV flights and more diverse germplasm could strengthen predictive ability and refine trait-based selection. Overall, this study advances the understanding of stage-specific photosynthetic variation in soybean and highlights the complementary value of CF and UAV phenotyping for improving physiology-driven selection in modern breeding programs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242576/s1, Figure S1: Field Layout illustrating the experimental design for (A) MG III, (B) MG IV early and (C) MG IV late entries. Each cell displays plot number (top) and corresponding entry number (bottom) arranged across two replicated blocks; Figure S2: Trait distributions including agronomic and photosynthetic and other morpho-physiological traits at both environments (LEE and FISK); Figure S3: Circle variable plots showing variable contribution of photosynthetic and morpho-physiological traits at (A) S1 stage and (B) S2 stage; Table S1: Summary of chlorophyll fluorescence (CF) sampling dates, growth stages and UAV imaging across environments and maturity groups (MG); Table S2: Description of vegetation indices used in this study [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L., H.S.-B. and F.R.; methodology, H.S.-B. and F.R.; software, H.S.-B. and F.R.; validation, H.S.-B. and F.R.; formal analysis, H.S.-B.; investigation, H.S.-B., F.R. and F.L.; resources, F.L.; data curation, H.S.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.-B.; writing—review and editing, H.S.-B., F.R., J.D.W., R.Z., G.S. and F.L.; visualization, H.S.-B.; supervision, G.S. and F.L.; project administration, F.L.; funding acquisition, F.L. and H.S.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Mid-South Soybean Board (MSSB, project # 00089558) and CAFNR dissertation research improvement grant by College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources (CAFNR), University of Missouri-Columbia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Mid-South Soybean Board (MSSB, project # 00089558) and CAFNR dissertation research improvement grant by University of Missouri for the funding support. The authors also want to thank our technical staff at MU-FDREEC for their immense support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GxE | Genotype x Environment interactions |

| CF | Chlorophyll Fluorescence |

| MG | Maturity Group |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| SPAD | Soil-Plant Analysis and Development |

| PS | Photosynthesis |

| RGB | Red-Green-Blue |

| MU-FDREEC | University of Missouri-Fisher Delta Research, Extension and Education Center |

References

- Graham, P.H.; Vance, C.P. Legumes: Importance and Constraints to Greater Use. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 872–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield Trends Are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, A.; Gaju, O.; Bowerman, A.F.; Buck, S.A.; Evans, J.R.; Furbank, R.T.; Gilliham, M.; Millar, A.H.; Pogson, B.J.; Reynolds, M.P.; et al. Enhancing Crop Yields through Improvements in the Efficiency of Photosynthesis and Respiration. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie-Gopsill, A.G.; Amirsadeghi, S.; Fillmore, S.; Swanton, C.J. Duration of Weed Presence Influences the Recovery of Photosynthetic Efficiency and Yield in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Front. Agron. 2020, 2, 593570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, E.E.; Webber, H.; Asseng, S.; Boote, K.; Durand, J.L.; Ewert, F.; Martre, P.; MacCarthy, D.S. Climate Change Impacts on Crop Yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralli, M.; Lawson, T. Natural Genetic Variation in Photosynthesis: An Untapped Resource to Increase Crop Yield Potential? Plant J. 2020, 101, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croce, R.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Cho, Y.B.; Ermakova, M.; Harbinson, J.; Lawson, T.; McCormick, A.J.; Niyogi, K.K.; Ort, D.R.; Patel-Tupper, D.; et al. Perspectives on Improving Photosynthesis to Increase Crop Yield. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 3944–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.T.; Parry, M.A.J. Shining Light on Photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 3243–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Che, Z.; Yuan, W.; Yu, D. GWAS Reveals Two Novel Loci for Photosynthesis-Related Traits in Soybean. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2020, 295, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suboktagin, S.; Khurshid, G.; Bilal, M.; Abbassi, A.Z.; Kwon, S.-Y.; Ahmad, R. Improvement of Photosynthesis in Changing Environment: Approaches, Achievements and Prospects. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 18, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.P.; Zhu, X.-G.; Naidu, S.L.; Ort, D.R. Can Improvement in Photosynthesis Increase Crop Yields? Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 29, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, C.M.; Fox, C.; Sanz-Sáez, Á.; Serbin, S.P.; Kumagai, E.; Krause, M.D.; Xavier, A.; Specht, J.E.; Beavis, W.D.; Bernacchi, C.J.; et al. High-Throughput Characterization, Correlation, and Mapping of Leaf Photosynthetic and Functional Traits in the Soybean (Glycine max) Nested Association Mapping Population. Genetics 2022, 221, iyac065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.A.; Freitas Moreira, F.; Rainey, K.M. Genetic Relationships Among Physiological Processes, Phenology, and Grain Yield Offer an Insight Into the Development of New Cultivars in Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 651241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakoda, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Long, S.P.; Shiraiwa, T. Genetic and Physiological Diversity in the Leaf Photosynthetic Capacity of Soybean. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamori, W. Genetic Diversity in Leaf Photosynthesis among Soybeans under the Field Environment. In Handbook of Plant and Crop Physiology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Li, W.; Hao, D.; Yang, Z.; Wu, F.; et al. Genetic Dissection of Ten Photosynthesis-Related Traits Based on InDel- and SNP-GWAS in Soybean. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaler, A.S.; Abdel-Haleem, H.; Fritschi, F.B.; Gillman, J.D.; Ray, J.D.; Smith, J.R.; Purcell, L.C. Genome-Wide Association Mapping of Dark Green Color Index Using a Diverse Panel of Soybean Accessions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herritt, M.; Dhanapal, A.P.; Purcell, L.C.; Fritschi, F.B. Identification of Genomic Loci Associated with 21chlorophyll Fluorescence Phenotypes by Genome-Wide Association Analysis in Soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Stein, M.; Oshana, L.; Zhao, W.; Matsubara, S.; Stich, B. Exploring Natural Genetic Variation in Photosynthesis-Related Traits of Barley in the Field. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 4904–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, U.; Bilger, W.; Neubauer, C. Chlorophyll Fluorescence as a Nonintrusive Indicator for Rapid Assessment of In Vivo Photosynthesis. In Ecophysiology of Photosynthesis; Schulze, E.-D., Caldwell, M.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 49–70. ISBN 978-3-642-79354-7. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, N.R. Chlorophyll Fluorescence: A Probe of Photosynthesis in Vivo. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, W.; Feng, Z.; Xiu, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W. Long Term Co-application of Biochar and Fertilizer Could Increase Soybean Yield under Continuous Cropping: Insights from Photosynthetic Physiology. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 3113–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, R.; Schulze, L.L.; Ashley, D.A.; Boerma, H.R.; Brown, R.H. Cultivar Differences in Canopy Apparent Photosynthesis and Their Relationship to Seed Yield in Soybeans. Crop Sci. 1982, 22, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virdi, K.S.; Sreekanta, S.; Dobbels, A.; Haaning, A.; Jarquin, D.; Stupar, R.M.; Lorenz, A.J.; Muehlbauer, G.J. Branch Angle and Leaflet Shape Are Associated with Canopy Coverage in Soybean. Plant Genome 2023, 16, e20304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Ma, J.; Lyu, M.; Shen, J.; Ying, J.; Ali, S.; Ali, B.; Lan, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. Monitoring Chlorophyll Content of Brassica napus L. Based on UAV Multispectral and RGB Feature Fusion. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Qi, Q.; Zheng, G.; Eitel, J.U.H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, F.; Fang, W.; Guan, Z.; et al. High-Throughput Field Phenotyping Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for Rapid Estimation of Photosynthetic Traits. Plant Phenomics 2025, 7, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhu, X.-G. Techniques for Photosynthesis Phenomics: Gas Exchange, Fluorescence, and Reflectance Spectrums. Crop Environ. 2024, 3, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, C. High-Throughput Phenotyping: Breaking through the Bottleneck in Future Crop Breeding. Crop J. 2021, 9, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, A.J.; López-Calcagno, P.E.; Raines, C.A. Feeding the World: Improving Photosynthetic Efficiency for Sustainable Crop Production. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 1119–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guan, K.; Wang, S.; Bailey, B.N.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Jiang, Z.; Li, K. Impact of Vertical and Seasonal Variation in Leaf Traits on Simulating Soybean Canopy Photosynthesis via 1D and 3D Modeling. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2026, 377, 110941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, R.P.; Nohl, B.M.; Diers, B.W.; Ainsworth, E.A. Has Photosynthetic Capacity Increased with 80 Years of Soybean Breeding? An Examination of Historical Soybean Cultivars. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1058–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruin, J.L.; Singer, J.W.; Pedersen, P.; Rotundo, J.L. Soybean Photosynthetic Rate and Carbon Fixation at Early and Late Planting Dates. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 2516–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczek, J.; Bobrecka-Jamro, D.; Jańczak-Pieniążek, M. Photosynthesis, Yield and Quality of Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) under Different Soil-Tillage Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bezouw, R.F.H.M.; Keurentjes, J.J.B.; Harbinson, J.; Aarts, M.G.M. Converging Phenomics and Genomics to Study Natural Variation in Plant Photosynthetic Efficiency. Plant J. 2019, 97, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlgert, S.; Austic, G.; Zegarac, R.; Osei-Bonsu, I.; Hoh, D.; Chilvers, M.I.; Roth, M.G.; Bi, K.; TerAvest, D.; Weebadde, P.; et al. MultispeQ Beta: A Tool for Large-Scale Plant Phenotyping Connected to the Open PhotosynQ Network. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 160592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Resende, M.D.V.; Alves, R.S. Linear, generalized, hierarchical, bayesian and random regression mixed models in genetics/genomics in plant breeding. Funct. Plant Breed. J. 2020, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Hartung, J.; Rath, J.; Piepho, H.-P. Estimating Broad-Sense Heritability with Unbalanced Data from Agricultural Cultivar Trials. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Cullis, B.R.; Thompson, R. The Analysis of Crop Cultivar Breeding and Evaluation Trials: An Overview of Current Mixed Model Approaches. J. Agric. Sci. 2005, 143, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2. In Use R! Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24275-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V.; Levy, M.; Xie, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zemla, J.; Freidank, M.; Cai, J.; Protivinsky, T. Corrplot: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix 2024; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses 2020; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Siebers, M.H.; Gomez-Casanovas, N.; Fu, P.; Meacham-Hensold, K.; Moore, C.E.; Bernacchi, C.J. Emerging Approaches to Measure Photosynthesis from the Leaf to the Ecosystem. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2021, 5, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Che, Z.; Wang, R.; Cui, R.; Xu, H.; Chu, S.; Jiao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, D.; et al. Novel Target Sites for Soybean Yield Enhancement by Photosynthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 268, 153580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kromdijk, J.; McCormick, A.J. Genetic Variation in Photosynthesis: Many Variants Make Light Work. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 3053–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoša Kočar, M.; Josipović, A.; Sudarić, A.; Duvnjak, T.; Viljevac Vuletić, M.; Marković, M.; Markulj Kulundžić, A. Chlorophyll a Fluorescence as Tool in Breeding Drought Stress-Tolerant Soybean. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2022, 23, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, S.; Seo, B.; Jajoo, A.; Reddy, K.R.; Reddy, V.R. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Is a Potential Indicator to Measure Photochemical Efficiency in Early to Late Soybean Maturity Groups under Changing Day Lengths and Temperatures. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1228464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, C.; Luis, C. Detection of Water and Nutritional Stress Through Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Radiative Transfer Models from Hyperspectral and Thermal Imagery (Detección de Estrés Hídrico y Nutricional Mediante Fluorescencia Clorofílica y Modelos de Transferencia Radiativa a Partir de Imágenes Hiperespectrales y Térmicas); UCOPress: Cordoba, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Grzybowski, M.; Torres-Rodríguez, J.V.; Li, F.; Shrestha, N.; Mathivanan, R.K.; de Bernardeaux, G.; Hoang, K.; Mural, R.V.; Roston, R.L.; et al. Quantitative Genetics of Photosynthetic Trait Variation in Maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 4141–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, A.; Jarquin, D.; Howard, R.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Specht, J.E.; Graef, G.L.; Beavis, W.D.; Diers, B.W.; Song, Q.; Cregan, P.B.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Grain Yield Stability and Environmental Interactions in a Multiparental Soybean Population. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2018, 8, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diers, B.W.; Specht, J.; Rainey, K.M.; Cregan, P.; Song, Q.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Graef, G.; Nelson, R.; Schapaugh, W.; Wang, D.; et al. Genetic Architecture of Soybean Yield and Agronomic Traits. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2018, 8, 3367–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaipho-Burch, M.; Cooper, M.; Crossa, J.; de Leon, N.; Holland, J.; Lewis, R.; McCouch, S.; Murray, S.C.; Rabbi, I.; Ronald, P.; et al. Scale up Trials to Validate Modified Crops’ Benefits. Nature 2023, 621, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.; Rainey, K.M. Quantitative Genomic Dissection of Soybean Yield Components. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, C.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Wu, Z.; Chen, Z. Development of Yield and Some Photosynthetic Characteristics during 82 Years of Genetic Improvement of Soybean Genotypes in Northeast China. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 1416–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Maity, S.; Srinivasan, V.; Dutta, P.; Roy, S.K.; Das, S. Natural Variation in Photosynthetic Traits Measured at Pre and Post Anthesis Stages for 36 Field Grown Wheat Genotypes. Int. J. Bio-Resour. Stress Manag. 2024, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, C.N.; Tiwari, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.; Singh, G.; Singh, G.P. Physiological Differences at Different Growth Stages of Wheat and Their Effect on Yield and Yield Attributing Traits. J. Cereal Res. 2020, 12, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M.A.; Xavier, A.; Rainey, K.M. Phenotypic Variation and Genetic Architecture for Photosynthesis and Water Use Efficiency in Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr). Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, R.A.; VanLoocke, A.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Zhu, X.-G.; Ort, D.R. Photosynthesis, Light Use Efficiency, and Yield of Reduced-Chlorophyll Soybean Mutants in Field Conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 00549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, T.; Mo, L.; Zhang, J.; Ren, H.; Zhao, N.; Gao, Y. Variation and Heritability of Morphological and Physiological Traits among Leymus chinensis Genotypes under Different Environmental Conditions. J. Arid. Land 2019, 11, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W. A Systematic Narration of Some Key Concepts and Procedures in Plant Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 724517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, D.; White, J.W.; Andrade-Sanchez, P.; Conley, M.M.; Heun, J.; Thorp, K.R.; French, A.N.; Hunsaker, D.J.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Wang, G.; et al. Investigation of the Influence of Leaf Thickness on Canopy Reflectance and Physiological Traits in Upland and Pima Cotton Populations. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 01405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Hu, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, H.; Luo, W.; Kage, U.; Liu, C.; Jia, J. Leaf Thickness of Barley: Genetic Dissection, Candidate Genes Identification and Its Relationship with Yield-Related Traits 2021. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1843–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Powell, O.; Gho, C.; Tang, T.; Messina, C. Extending the Breeder’s Equation to Take Aim at the Target Population of Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1129591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Bakala, H.; Ravelombola, F.; Adeva, C.; Oliveira, M.; Zhang, R.; Argenta, J.; Shannon, G.; Lin, F. Harnessing Photosynthetic and Morpho-Physiological Traits for Drought-Resilient Soybean: Integrating Field Phenotyping and Predictive Approaches. Front. Plant Physiol. 2025, 3, 1591146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiozza, M.V.; Parmley, K.; Schapaugh, W.T.; Asebedo, A.R.; Singh, A.K.; Miguez, F.E. Changes in the Leaf Area-Seed Yield Relationship in Soybean Driven by Genetic, Management and Environments: Implications for High-Throughput Phenotyping. Silico Plants 2024, 6, diae012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, A.; Hall, B.; Hearst, A.A.; Cherkauer, K.A.; Rainey, K.M. Genetic Architecture of Phenomic-Enabled Canopy Coverage in Glycine max. Genetics 2017, 206, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, C.R.; Sant’ana, G.C.; Meda, A.R.; Garcia, A.; Souza Carneiro, P.C.; Nardino, M.; Borem, A. Association between Unmanned Aerial Vehicle High-throughput Canopy Phenotyping and Soybean Yield. Agron. J. 2022, 114, 1581–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.K.S.; Araújo, M.S.; Chaves, S.F.S.; Dias, L.A.S.; Corrêdo, L.P.; Pessoa, G.G.F.A.; Bezerra, A.R.G. High Throughput Phenotyping in Soybean Breeding Using RGB Image Vegetation Indices Based on Drone. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Bai, D.; Tian, Y.; Li, Y.-H.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S.; Gu, Y.; Luan, X.; Wang, R.; et al. Time Series Canopy Phenotyping Enables the Identification of Genetic Variants Controlling Dynamic Phenotypes in Soybean. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, B.P.; Xavier, A.; Moreira, F.; Casteel, S.; Rainey, K.M. Quantitative Characterization of Proximate Sensing Canopy Traits in the SoyNAM Population. Crop Sci. 2021, 61, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajjarpoor, A.; Nelson, W.C.D.; Vadez, V. How Process-Based Modeling Can Help Plant Breeding Deal with G x E x M Interactions. Field Crops Res. 2022, 283, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. 1974; pp. 309–317. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/19740022614 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Barnes, E.; Clarke, T.R.; Richards, S.E.; Colaizzi, P.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T.L. Coincident Detection of Crop Water Stress, Nitrogen Status, and Canopy Density Using Ground Based Multispectral Data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16–19 July 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote Estimation of Canopy Chlorophyll Content in Crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L08403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.R. A Soil-Adjusted Vegetation Index (SAVI). Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 25, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, J.; Curran, P.J. The MERIS Terrestrial Chlorophyll Index. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 5403–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Montzka, C.; Stadler, A.; Menz, G.; Thonfeld, F.; Vereecken, H. Estimation and Validation of RapidEye-Based Time-Series of Leaf Area Index for Winter Wheat in the Rur Catchment (Germany). Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 2808–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and Photographic Infrared Linear Combinations for Monitoring Vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, M.D. The Sensitivity of the OSAVI Vegetation Index to Observational Parameters. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 63, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wen, M.; Lu, Y.; Ma, F. Accuracy Comparison of Estimation on Cotton Leaf and Plant Nitrogen Content Based on UAV Digital Image under Different Nutrition Treatments. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KAWASHIMA, S.; NAKATANI, M. An Algorithm for Estimating Chlorophyll Content in Leaves Using a Video Camera. Ann. Bot. 1998, 81, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, R.; Pouget, M.; Cervelle, B.; Escadafal, R. Relationships between Satellite-Based Radiometric Indices Simulated Using Laboratory Reflectance Data and Typic Soil Color of an Arid Environment. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Artizzu, X.P.; Ribeiro, A.; Guijarro, M.; Pajares, G. Real-Time Image Processing for Crop/Weed Discrimination in Maize Fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2011, 75, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, T.; Kaneko, T.; Okamoto, H.; Hata, S. Crop Growth Estimation System Using Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2003 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM 2003), Kobe, Japan, 20–24 July 2003; Volume 2, pp. b1079–b1083. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoqin, W.; Miaomiao, W.; Shaoqiang, W.; Yundong, W. Extraction of Vegetation Information from Visible Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images. Nongye Gongcheng Xuebao 2015, 31, 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Escadafal, R.; Belghit, A.; Ben-Moussa, A. Indices Spectraux pour la Télédétection de la Dégradation des Milieux Naturels en Tunisie Aride. In Proceedings of the 6eme Symposium International sur les Mesures Physiques et Signatures en Télédétection, Val d’Isère, France, 17–24 January 1994; Guyot, G., Ed.; pp. 253–259. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1933253 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).