Abstract

The production and quality of wheat and maize grain can be significantly affected by various pests and pathogens, with phytoplasmas posing a particular threat due to their rapid spread and potential to cause severe damage to cultivated crops. The objective of this investigation was to evaluate the risk associated with these wall-less bacteria in wheat and maize crops. To achieve this, a survey was conducted in commercial fields located in southwestern Poland. Samples of winter wheat and fodder maize were collected at two distinct developmental stages, including both symptomatic and asymptomatic plants. Symptoms observed in wheat included yellowing, stunting, and excessive tillering, while maize plants showed yellow leaf striping, red discoloration, and stunted growth. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays using phytoplasma-specific primers, followed by Sanger sequencing and sequence analysis, confirmed phytoplasma infections in 2% of wheat and 1.5% of maize samples. Virtual restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis identified the wheat-infecting phytoplasmas as belonging to subgroup 16SrI-C (‘Candidatus Phytoplasma tritici’-related strain)—a pathogen of major concern for wheat, while maize-infecting phytoplasmas were classified into subgroups 16SrI-B and 16SrV-C. Additionally, wheat plants collected during the early elongation phase were tested for Mastrevirus hordei (former wheat dwarf virus, WDV) using double antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (DAS-ELISA), which confirmed the presence of WDV in all tested samples. Preliminary screening of field-collected leafhoppers revealed that 7.5% of Psammotettix alienus, the predominant species in wheat fields, carried 16SrI-C phytoplasmas. In maize fields, Zyginidia scutellaris was the most prevalent species, with 1.7% of individuals carrying 16SrV-C phytoplasma. These findings suggest that these insect species may contribute to the transmission of phytoplasmas in wheat and maize. This study provides the first documented evidence of 16SrI-C phytoplasma infecting wheat in Poland, and of 16SrV-C and 16SrI-B phytoplasmas infecting maize, expanding the known host range of these subgroups in the country and highlighting their potential phytosanitary importance.

1. Introduction

Phytoplasmas represent wall-less bacterial plant pathogens that affect numerous vascular plants globally, including herbaceous and woody fruit crops [1]. These pathogens colonize the sieve cells, wherein they replicate and migrate through plasmodesmata to various source and sink parts of the plant. Consequently, they interfere with plant development and modulate defense responses through the secretion of effector proteins [2]. Phytoplasmas depend on sap-feeding hemipteran insects, comprising leafhoppers, planthoppers, and psyllids (Hemiptera), for the transmission between plant hosts [3]. Phytoplasma detection is commonly carried out by nested PCR or quantitative PCR, while taxonomic identification typically relies on sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene followed by sequence comparison and analysis [4].

Phytoplasmas are taxonomically classified into 37 groups and more than 150 subgroups based on 16S rRNA gene restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) profiles [5]. They are also assigned to the provisional genus Candidatus Phytoplasma, which currently comprises nearly 50 described Candidatus species [6]. Because phytoplasmas possess two rRNA operons (rrnA and rrnB), that may differ in sequence heterogeneity across strains, 16S rRNA sequences alone do not always provide sufficient resolution of their genetic diversity [7,8]. To address this limitation, additional molecular markers—such as ribosomal protein (rp) genes, elongation factor Tu (tuf), and the SecY translocase subunit (secY)—have been employed to investigate phylogenetic relationships among phytoplasma strains [9,10,11].

Wheat and maize—following rice—are among the world’s most widely used grains and are essential sources of energy and dietary fiber for both humans and livestock. In 2024, the European Union (EU) was the world’s second largest wheat producer (122 MT) and the fourth-largest maize producer (59 MT), after the USA (378 MT), China (295 MT), and Brazil (136 MT) (https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0410000 and https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0440000 accessed on 2 December 2025). Poland is a major agricultural contributor, allocating nearly 70% of its arable land to cereal production and ranking third in the EU for both wheat and maize output (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tag00047/default/table and https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/tag00093/default/table accessed on 2 December 2025). Wheat is primarily used by the bakery industry, whereas maize green forage remains an important feed resource for livestock.

The production and quality of wheat and maize grain can be seriously impacted by various pests and pathogens. Among these, phytoplasmas are particularly concerning due to their rapid spread and potential to cause devastating effects on cultivated plants. For example, in northwestern China, a wheat disease caused by wheat blue dwarf (WBD) phytoplasma, transmitted by the Psammotettix striatus leafhopper, often affects wheat production and leads to economic losses [12]. Typical symptoms observed during WBD outbreaks in China include stunted growth, yellowing of leaf tips, and bluish streaks along the leaves [12]. The WBD phytoplasma strain, classified within the 16SrI-C subgroup [13], and recently described as the new species ‘Ca. Phytoplasma tritici’, is also referred to as 16SrI-(R/S)C to denote the heterogeneity between its two 16S rRNA operons [14].

Maize is also susceptible to phytoplasma infections, with at least four distinct phytoplasma strains known to infect maize plants [8,15,16,17]. For instance, maize bushy stunt (MBS) disease—common in Latin America—is caused by 16SrI-B phytoplasmas transmitted by the corn leafhopper Dalbulus maidis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) [18]. MBS symptoms include leaf chlorosis and reddening of the margins, plant stunting, increased lateral branching, and reduced grain yield [17]. Another important disease is maize redness (MR), found in the Balkans, linked to ‘Ca. Phytoplasma solani’ (16SrXII-A) [16]. MR disease manifests with progressive reddening of leaves and stems, leading to plant desiccation and incomplete kernel development, but unlike MBS, overall plant height remains unaffected. Two cixiid species, Reptalus panzeri and Hyalesthes obsoletus (Hemiptera: Fulgoromorpha), have been identified as vectors of ‘Ca. Phytoplasma solani’ [16,19].

Phytoplasma-induced diseases in grains can be easily overlooked because their symptoms are non-specific and resemble those caused by other common pathogens [20]. This makes differential diagnosis essential, particularly in distinguishing phytoplasma infections from viral diseases with similar symptomatology. For instance, Mastrevirus hordei (WDV) causes severe stunting, yellowing, and leaf streaks, symptoms that may be mistaken for those induced by WBD phytoplasma. WDV poses a major threat to wheat and barley across Europe, Asia, and northern Africa, causing substantial economic losses [21]. It is transmitted persistently by Psammotettix alienus (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), a leafhopper frequently found on grasses and winter cereals [22,23]. Importantly, P. alienus was listed among the leafhopper species naturally infected with phytoplasmas, suggesting that it may contribute also to phytoplasma circulation within agroecosystems [24].

Similarly, barley yellow dwarf (BYD) viruses can produce leaf discoloration and growth inhibition that mimic phytoplasma symptoms. BYD is the most economically significant viral disease of cereals globally, with yield losses reaching up to 80% [25]. It is caused by a group of luteoviruses, poleroviruses and solemoviruses which are transmitted by approximately 25 aphid species [25,26]. In Poland, five BYDV species have been reported [27], with Luteovirus pashordei (BYDV-PAS) identified as the predominant agent [28]. Given their overlapping symptom profiles with phytoplasma diseases, both WDV and BYDV must be considered during diagnosis of cereal decline.

Although phytoplasmas are globally distributed, their epidemiology in temperate regions remains insufficiently understood. Climate warming may further elevate the risk of phytoplasma outbreaks by improving survival and increasing the abundance of insect vectors. Ensuring food production security therefore requires effective risk assessment supported by early detection of pathogens and their vectors through systematic field monitoring. To address this need, the present study surveyed wheat and maize fields in the warmest region of Poland (southwestern Poland) to determine the occurrence of phytoplasma infections and identify potential insect vectors. We hypothesized that phytoplasmas and their vectors are already present in this region and may pose an emerging threat to cereal production under changing climatic conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Collection and DNA Templates

In 2019, field surveys were conducted in the Lower Silesia region (southwestern Poland) to detect phytoplasma infections. A total of 200 wheat and 200 maize samples were collected from four winter wheat fields and two fodder maize fields (coordinates in Table 1). Samples were collected during two distinct developmental stages of wheat: the tillering phase (when the main shoot and tillers develop, BBCH stages 24 and 25) and the late stem elongation phase (when the flag leaf ligule becomes just visible, BBCH stage 39).

Table 1.

Wheat and maize fields surveyed for phytoplasma infections.

Comparable collections were conducted in maize fields at two growth stages: the seven unfolded leaf stage (BBCH scale 17) and the nine visible node stage (BBCH scale 39). These time points were determined based on the BBCH scale, a widely recognized reference for the growth stages of cereals (https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/the-growth-stages-of-cereals accessed on 2 December 2025).

Throughout the study, a total of eight field excursions were conducted. At each location, 25 plants showing symptoms potentially indicative of phytoplasma infection—such as leaf yellowing or reddening, reduced plant vigor, and excessive branching, —and 25 asymptomatic plantswere selected arbitrarily from a rectangular area of 100 m2. Each sample consisted of leaf tissue collected from several parts of the same plant to ensure representative material and to improve the detection of low-concentration pathogens such as phytoplasmas. For each sample, 3 grams of freshly ground leaf tissue were used for nucleic acid extraction with a 2% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) buffer [8]. The final nucleic acid pellets were suspended in 500 µL of TE buffer and stored at −20 °C. Healthy wheat seedlings sown and transplanted in greenhouse were used as negative controls for both DNA extraction and subsequent PCR.

2.2. Insect Collection and DNA Templates

Adult Auchenorrhyncha specimens were collected from winter wheat and fodder maize crops in southwestern Poland (Table 2) by performing 50 full sweeps with an entomological net. Sweeping was conducted in two lines over an area of approximately 100 m2. The collected specimens were preserved in 96% ethanol at 4 °C until further analysis. Insect identification was performed based on morphological characteristics under a stereomicroscope [29]. Specimens from maize fields were collected one year prior to plant sampling, while those from wheat fields were collected concurrently with plant sampling in May 2019.

Table 2.

Wheat and maize fields surveyed for phytoplasma infections in insects.

Insect DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin® Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Individual insects were placed in Eppendorf tubes and homogenized with a micro-pestle. Nucleic acids were suspended in 100 µL of sterile, deionized water, and 1 µL of this DNA was used as the template in a nested PCR assay with phytoplasma 16S rDNA-specific primers, as described below.

2.3. Phytoplasma Detection and Identification

To detect phytoplasmas, a nested PCR procedure was performed using universal primers P1/P7, followed by fU5/rU3 primers (Table 3). Each 25 µL reaction mixture contained 1 µL of DNA solution, 0.4 µM of each primer, and 1× GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Thermocycling conditions followed the protocol previously described by Zwolińska and Borodynko-Filas [8]. PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel containing Midori Green dye (NIPPON Genetics Europe, Düren, Germany) and visualized under UV transillumination.

The amplicons were sequenced using the Sanger method in one direction with primer fU5 by Genomed Inc. (Warsaw, Poland). To verify the sequences, initial BLASTn searches were conducted against the NCBI nucleotide database (GenBank), available at https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, accessed on 2 December 2025. Phytoplasma-positive plant samples underwent additional nested PCR assays with the primer pairs P1/M1R and M1/P7 (Table 3), using the P1/P7 amplicons as templates. The resulting PCR products were sequenced on both strands. The 16S rDNA fragments were assembled into consensus sequences using BioEdit software v7.2.5 (https://bioedit.software.informer.com), and the region flanked by primers R16F2n/R16R2 (hereafter referred to as F2n/R2) was subjected to virtual Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (vRFLP) analysis using the iPhyClassifier tool [30] to assign phytoplasma strains to ribosomal subgroups, following the classification described by Lee et al. [31]. The fU5-primed sequences obtained from insect samples were classified into ribosomal subgroups through comparative analysis with reference phytoplasma strain sequences.

Table 3.

Primers used for amplification of the phytoplasmas’ genes.

Table 3.

Primers used for amplification of the phytoplasmas’ genes.

| Primer | Region Amplified | Sequence 5′-3′ | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 16S rDNA | AAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAGGATT | [32] |

| M1R | 16S rDNA | GCCTCAGCGTCAGTAAAGAC | [33] |

| M1 (16R758F) | 16S rDNA | GTCTTTACTGACGCTGAGGC | [33] |

| P7 | 23S rDNA | CGTCCTTCATCGGCTCTT | [34] |

| fU5 | 16S rDNA | CGGCAATGGAGGAAACT | [35] |

| rU3 | 16S rDNA | TTCAGCTACTCTTTGTAACA | |

| R16F2n | 16S rDNA | GAAACGACTGCTAAGACTGG | [36] |

| R16R2 | 16S rDNA | TGACGGGCGGTGTGTACAAACCCCG | |

| fTuf1 | tuf | CACATTGACCACGGTAAAAC | [37] |

| rTuf1 | tuf | CCACCTTCACGAATAGAGAAC | |

| fTuf1n | tuf | CACGTAGACCACGGTAAAAC | [37] |

| rTuf1n | tuf | CCACCTTCACGAATAGAAAAT | modified |

| fTufAY | tuf | GCTAAAAGTAGAGCTTATGA | [37] |

| rTufAY | tuf | CGTTGTCACCTGGCATTACC | |

| RevI-S | ITS | GCAAGTAAGTTAGTTATAATGAAAAAC | This study |

| RevI-R | ITS | AATGCAATTTGCAAGCAAG |

2.4. The Ribosomal RNA Operon-Specific Amplification of rRNA Genes of 16SrI-C Phytoplasma Strains

The ribosomal RNA operon-specific primers were utilized to detect sequence heterogeneity of 16S rRNA genes in 16SrI-C phytoplasma strains. Two distinct reverse primers, RevI-S and RevI-R (Table 3), were designed based on the Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) located between the 16S rRNA and RNA-Ile genes of Clover phyllody phytoplasma strain KV (GenBank Acc. rrnA AB639059 and rrnB AB639060). These primers hybridize operon A (rrnA) and operon B (rrnB), respectively. The two reverse primers were paired with the forward primer fU5 [35] for PCR amplification with the P1/P7 products used as templates. The same reaction mixtures as described above were used. The PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 32 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 45 s, annealing at 50 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 90 s, followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The resulting sequences were integrated into previous assemblies, and consensus sequences of the rrnA and rrnB 16S rRNA genes were subjected to BLASTn search to identify closely related phytoplasmas. Subsequently, the sequences underwent further pairwise sequence comparison using BioEdit, where single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified among the two operon sequences obtained, and 16S rRNA gene sequences from the draft genome of the WBD (NCBI reference NZ AVAO01000003).

2.5. Phylogenetic Tree Based on the 16S rRNA Gene

To assess the evolutionary interrelationships between phytoplasma strains, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on 16S rRNA gene fragment (1482 nt). Sequences of phytoplasma detected in wheat and maize were aligned together with 39 sequences of phytoplasmas representing different ribosomal groups and subgroups, retrieved from the GenBank database. Acholeplasma laidlawii strain was selected as the out-group to root the tree. Multiple sequence alignment was generated using ClustalW program v. 3.1, built-in BioEdit v. 7.2.5 [38]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA12 using the Maximum Likelihood method. The Tamura–Nei substitution model, identified in MEGA as the best-fitting model for the analyzed sequences, was applied [39]. Branch support was assessed by bootstrapping with 1000 replicates.

2.6. The Tuf Gene Comparative Analysis

Further genetic characterization of phytoplasma strains detected in wheat and insects collected from wheat fields was conducted by analyzing the tuf gene, which encodes the translational elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu). The tuf gene fragment was initially amplified using modified fTuf1/rTuf1 primers (Table 3) in the first PCR round with an annealing temperature of 45 °C. Subsequently, nested-PCR was performed using the primers fTufAY/rTufAY, with an annealing step at 52 °C (Schneider et al., 1997 [37]). The resulting PCR products were visualized on agarose gels as described above and sequenced in each direction using fTufAY/rTufAY primers.

The raw sequences were aligned and trimmed to a congruent length of 896 nt. A phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA12, as described above, incorporating reference sequences retrieved from GenBank, with Ureaplasma parvum strain used to root the tree.

2.7. Cereal Viruses Detection in Wheat Using ELISA and PCR

Given that wheat is a host of both WDV and barley yellow dwarf viruses (BYDVs), and to determine whether the symptoms observed in wheat plants were linked to viral infection or a potential co-infection involving both phytoplasmas and viruses, plant samples collected from field W1 showing yellowing and stunted growth at the early elongation developmental phase were tested for the presence of WDV and BYDVs using a double antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (DAS-ELISA). These serological diagnostic tests [40] were performed with specific commercial polyclonal antisera (Loewe Biochemica, Sauerlach, Germany), as described previously [41]. Leaf samples were homogenized with extraction buffer from Bioreba (Reinach, Switzerland) using a Bioreba Homex 6 homogenizer. Negative controls, consisting of healthy wheat plants of the Muszelka variety grown in protected conditions in a greenhouse, and commercial positive controls for WDV and BYDV (Loewe) were used for the analyses. Diagnostic tests were performed according to the manufacturers’ recommended procedure. Results were read in an ELx800 microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA) at a wavelength of 405 nm. Additionally, phytoplasma-positive samples were subjected to a duplex PCR assay designed to detect both wheat- and barley-specific forms of WDV, namely WDV-W and WDV-B. Two primer pairs targeting specific regions of WDV-W and WDV-B were used, WDV-T-F (CGAGTAGTTGATGAATGACTCG)/WDV-T-R (GGCTGTTTCAACTCCAGGTCG) and WDV-H-F (CAAGGGGCGAGATCACACA)/WDV-H-R (CCACAACTACTACAACAGCC), following the method described by Trzmiel and Klejdysz [42]. As positive controls, wheat and barley samples infected with WDV-W and WDV-B strains, respectively, were included.

3. Results

3.1. Symptoms Observed in Wheat and Maize

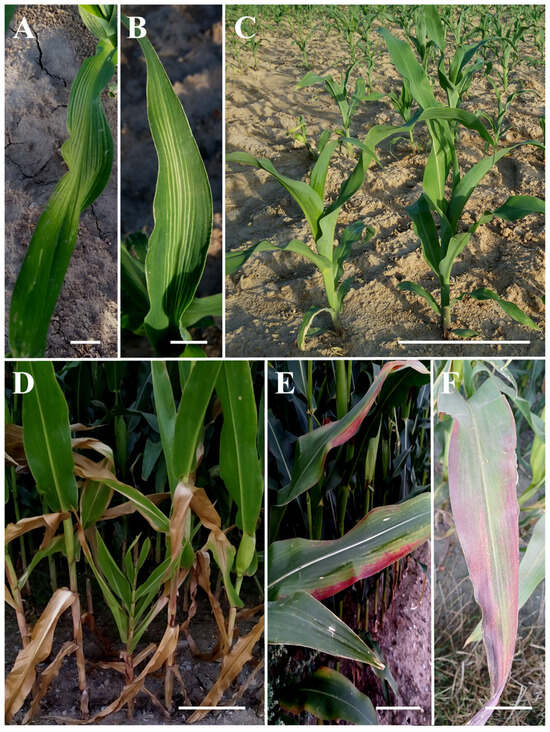

During the tillering phase of wheat (BBCH 24/25), approximately 20% of observed plants in the field displayed small yellow discolorations on the leaves (Figure 1A,B). This was the sole symptom observed at this stage. However, during inspection in the final stem elongation phase (BBCH 39), a significant growth inhibition was noted in 10% of the plants, resulting in dwarfism in wheat (Figure 1C). Additionally, the leaves of these plants exhibited yellow spots, resembling a mosaic pattern. As these spots enlarged over time, the older leaves began to wither and die. Symptomatic plants demonstrated slower development compared to their healthy counterparts and concluded their vegetation cycle in the tillering phase, characterized by excessive growth of basal leaves (Figure 1D). Wheat plants representing asymptomatic samples exhibited normal growth patterns and were found to be in the appropriate developmental phase. These plants showed no discolorations or other changes indicative of the presence of pathogenic organisms.

Figure 1.

Symptoms observed on winter wheat plants: (A,B) yellow discolorations occurring during the tillering phase; (C) growth inhibition; (D) comparison of asymptomatic plant (1) and symptomatic one (2). Scale bar = 2 cm.

During inspection of maize fields at the stage of 7–8 unfolded leaves (BBCH 17/18), approximately 20% of plants showed visible symptoms, with bright, elongated, parallel stripes along the leaf veins (Figure 2A,B). As the maize plants reached the phase of final stem elongation (BBCH 39), red discolorations appeared on the leaves. These discolorations originated from the outer edge of the leaves and intensified as they extended towards the main vein (Figure 2E,F). Additionally, reduced growth was observed in some plants (Figure 2D). Approximately 10% of maize plants exhibited symptoms indicative of phytoplasma disease during this developmental phase.

Figure 2.

Symptoms observed on maize plants: (A,B) bright, long, parallel stripes along the veins at BBCH stage 17–18; (C) asymptomatic plants; (D) reduced growth apparent at BBCH stage 39; (E,F) red discolorations on the outer edges of leaves. Scale bar = 2 cm (in (A,B,E,F)) or 40 cm (in (C,D)).

3.2. Phytoplasma Detection and Identification in Plant Samples

Phytoplasmas were detected in four wheat plants and three maize plants, with no amplicons observed in the negative controls. Assembly of the ribosomal sequence reads (fU5, P1, M1R, M1, P7) yielded 16S-ITS regions, ranging in length from 1752 to 1770 bp across all seven phytoplasma strains. This region includes the 16S rRNA gene (excluding the P1 primer site), the intergenic spacer (ITS), and the tRNA-Ile gene.

The four phytoplasma-infected wheat samples (2%) originated from nearby locations (fields W1 and W7), collected during the late stem elongation and tillering phases, respectively. Among them, plant W1.22 exhibited symptoms such as yellow spots on the leaves, dwarfism, and excessive branching, while W1.36, W1.47, and W7.07 showed no apparent symptoms. Nevertheless, the phytoplasmas detected in all four samples exhibited homologous DNA sequences within the 16S-ITS ribosomal fragment.

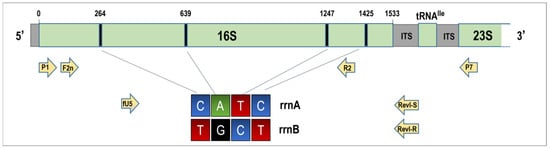

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were observed at several positions in the ribosomal sequences from wheat, indicating inter-operon heterogeneity. To confirm this and differentiate the 16S rRNA sequences from rrnA and rrnB operons, we used the primers RevI-S and RevI-R, which target operon-specific ITS regions. Sequencing of the resulting amplicons confirmed that the wheat-derived phytoplasma strain possesses two heterogeneous 16S rRNA gene copies. Nucleotide differences were detected at positions 264 (C/T), 639 (A/G), 1247 (T/C), and 1425 (C/T) of the P1/P7 region (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of a ribosomal operon fragment illustrating the locations of polymorphic sites within the 16S rRNA genes of 16SrI-C phytoplasmas, along with the positions of primers utilized in this study. The colors green, blue, black, and red represent nucleotides with adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T) nitrogenous bases, respectively.

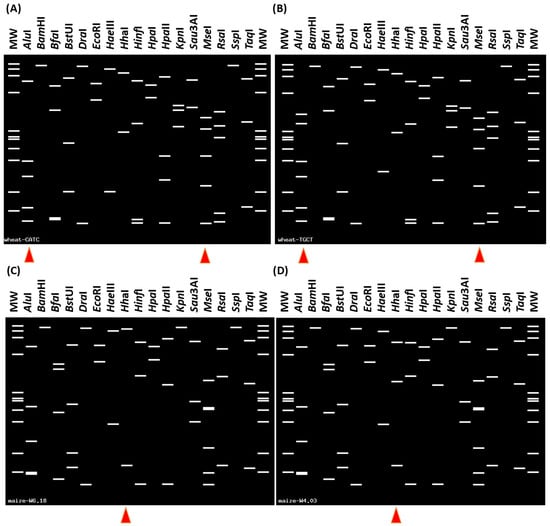

Virtual RFLP analysis revealed that the collective RFLP profiles of rrnA and rrnB 16S rDNA matched those of 16SrI-S and 16SrI-R phytoplasma subgroups, respectively (Figure 4A,B), placing the strain within subgroup 16SrI-(S/R)C.

Figure 4.

Virtual RFLP patterns derived from in silico digestion of 16S rRNA gene F2nR2 fragment of phytoplasma strains amplified from wheat (A,B) and maize (C,D) samples. (A) ‘CATC’ (rrnA) variation pattern is identical (similarity coefficient 1.00) to the reference strain of subgroup 16SrI-S (HM067755) (B) ‘TGCT’ (rrnB) variation pattern is identical to the reference strain pattern of subgroup 16SrI-R (HM067754). (A,B) The enzymes AluI and MseI yielded distinctive digestion profiles, marked by red triangles. The phytoplasma strain infecting wheat belongs to the 16SrI-(S/R)C subgroup. (C) The virtual RFLP pattern is identical to the reference pattern of phytoplasma subgroup 16SrV-C (AY197642). (D) The virtual RFLP pattern derived from the maize W4.03 sample is most similar to the pattern of subgroup 16SrV-C (similarity coefficient 0.97). (C,D) Distinctive digestion profiles of enzyme HhaI were found between maize phytoplasma samples W6.18 and W4.03 (red triangles). The maize phytoplasmas W4.03 and W6.18 are members of 16SrV-C.

Further BLASTn analysis revealed that the 16SrI-S-type sequence (1764 nt) was identical to the rDNA of Clover Phyllody phytoplasmas KV (rrnA, GenBank Acc. AB639059) and CPh (GenBank Acc. AF222066). Whereas the 16SrI-R-type sequence (1752 nt) showed 99.94% similarity to the Potato purple top phytoplasma PPT rrnB (GenBank Acc. AB639062), KV rrnB (GenBank Acc. AB639060), and Echinacea purpurea phyllody phytoplasma (GenBank Acc. EF546778).

Furthermore, pairwise comparison of the 16S rRNA gene variants revealed that the phytoplasma strain isolated from wheat samples in Poland shares identical sequences with the WBD phytoplasma (NCBI reference NZ_AVAO01000003), previously identified in China as subgroup 16SrI-(R/S)C—commonly referred to as the 16SrI-C strain—and recently named ‘Ca. Phytoplasma tritici’ [6]. Although the WBD sequence is not currently retrievable via standard BLAST searches, the similarity between the sequences was confirmed through direct comparison.

Consequently, based on these findings, the phytoplasma strains detected in wheat in Poland belong to subgroup 16SrI-C. Representative sequences of each operon-specific 16S rDNA variant were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers: PX118923 for rrnA 16S rRNA gene (16SrI-S type sequence) and PX118924 for rrnB (16SrI-R type sequence).

Additionally, phytoplasmas were detected in three maize plants, all of which exhibited symptoms indicative of phytoplasma infection, representing 1.5% of the analyzed samples. Two of the phytoplasma-infected maize plants, W3.05 and W4.03 were collected during the 7–8 unfolded leaf stage (BBCH 17/18) and displayed bright leaf discolorations. By the final stem elongation phase (BBCH 39), the phytoplasma-infected maize plant W6.18 exhibited red discoloration of the leaf blade along with restricted growth.

BLASTn searches against the NCBI nucleotide database revealed that the phytoplasma strain W3.05 showed 100% sequence identity with ‘Ca. Phytoplasma asteris’ strains (subgroup 16SrI-B) previously identified in rapeseed, garden pea, and lupine in Poland (CP055264, MK440282, MK440284). Similarly, the virtual RFLP pattern derived from strain W3.05 was identical (similarity coefficient = 1) to the reference pattern of the 16SrI-B subgroup (AP006628).

Based on BLASTn searches, the W4.03 and W6.18 maize phytoplasma strains showed the highest sequence identities of 99.83% and 99.89%, respectively, with the ‘Ulmus laevis’ yellows phytoplasma strain EY4 from Poland (MT859113), representing subgroup 16rV-C. Furthermore, the virtual RFLP pattern derived from strain W6.18 was identical to that of subgroup 16SrV-C (AY197642). Likewise, the virtual RFLP pattern derived from strain W4.03 was most similar to the 16SrV-C pattern (similarity coefficient = 0.97); however, it differed from all previously established 16Sr subgroups and may represent a novel subgroup within group 16SrV (Figure 4D) [30].

The phytoplasma nucleotide sequences—covering nearly the full-length 16S rRNA gene, ITS region, and tRNA-Ile gene (1.77 kb)—from samples W4.03 and W6.18 differed by four SNPs and were submitted to the NCBI database under the accession numbers PX118926 and PX118927. The sequence from phytoplasma strain W3.05 was submitted under the accession number PX118925.

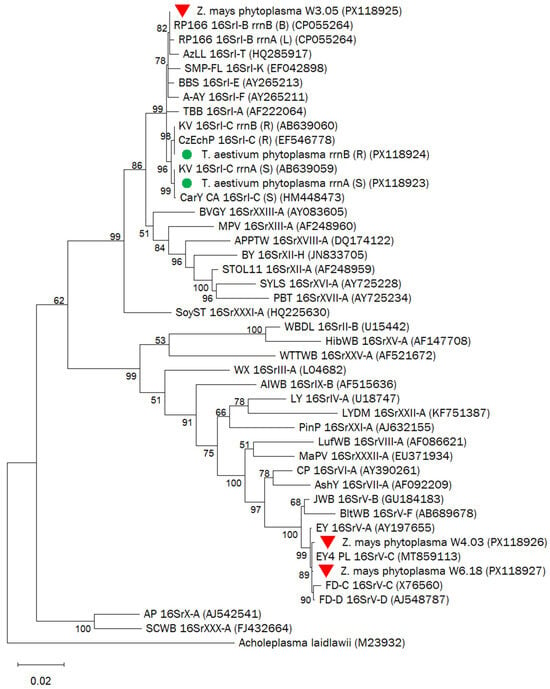

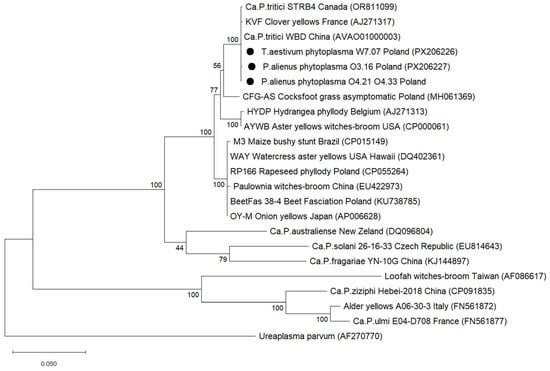

3.3. 16S rRNA Gene Phylogeny

The topology of the phylogenetic tree constructed from the 16S rRNA gene region (1482 nt) confirmed the phytoplasma classifications obtained through vRFLP analysis. Both rRNA gene variants of the phytoplasmas identified in wheat samples (W1.22, W1.36, W1.47, W7.07) formed a single subclade with strains representative of subgroup 16SrI-C(S/R), dividing into two branches that reflect sequence differences between the rrnA and rrnB operons.

In contrast, the maize phytoplasma strains W4.03 and W6.18 clustered with strains representative of subgroup 16SrV-C, including the elm yellows phytoplasma strain EY4_PL. The maize phytoplasma strain W3.05 grouped within the 16SrI-B-related subclade (bootstrap value: 70), sharing a branch with the rapeseed phyllody phytoplasma strain RP166, also belonging to subgroup 16SrI-B (Figure 5). These results are consistent with the vRFLP-based classification.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (1482 nt) of phytoplasma strains identified in wheat (green dots) and in maize (red triangles) and reference strains representing different 16Sr groups and subgroups. The phylogenetic analysis was performed with the Maximum Likelihood method using the Tamura-Nei model. Branch lengths reflect the number of base substitutions per site. The percentage of trees out of 1000 in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches (values > 50). The accession numbers of the sequences are presented in parentheses.

3.4. Insect Collection and Species Identification

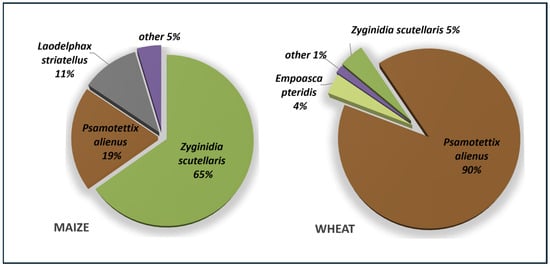

In 2018, a total of 275 insect specimens were collected from maize fields, representing nine species across two genera. Zyginidia scutellaris (Cicadellidae, Typhlocybinae) comprised 65% of the total catch, indicating its emergence as the dominant leafhopper species in Polish maize fields. Psammotettix alienus (19%) and Laodelphax striatellus (11%) were the next most abundant species, while the remaining taxa accounted for only a small proportion of the total catch (Figure 6). Phytoplasmas belonging to groups 16SrV-C and 16SrI-C were identified in three Z. scutellaris individuals and in one P. alienus individual, respectively. In May 2019, leafhoppers of five species were collected from wheat fields. Among the 133 specimens examined, P. alienus was the predominant species, constituting 90% of the catch. Phytoplasmas were detected in 8.3% (10 out of 120) of the P. alienus specimens: 16SrI-C was found in nine individuals, and 16SrI-B in one. Other leafhopper species were less abundant (Figure 6, Table 4).

Figure 6.

Composition of leafhopper and planthopper taxa collected from maize (August 2018) and wheat (May 2019). Low-frequency species detected in maize fields (other 5%) included Empoasca pteridis, Macrosteles laevis, Mocuellus collinus, Streptanus aemulans, Stenocranus sp., Dicranotropis hamata. Low-frequency species detected in wheat fields (other 1%) included: Z. pullula, Zygina flammigera.

Table 4.

Phytoplasmas detected in insects and their identification. Insect samples are coded as OX.YY or OX.YYY, where OX denotes the batch collected during field trip X and YY/YYY is the assigned sample number.

3.5. Tuf Gene Sequences

For further characterization of the phytoplasma strains, the tuf gene sequences from wheat and insect samples were amplified and compared. In silico analysis revealed that strains infecting wheat (W7.07) and P. alienus (O4.21 and O4.33) shared identical tuf gene sequences (896 nt), matching the tuf sequence of the WBD ‘Ca. P. tritici’ strain (NCBI reference NZ AVAO01000003.1), while strain O3.16 (W1 field) differed from the WBD strain by one nucleotide. According to BLASTn analysis, the identical sequences of WBD and the three Polish strains shared the highest sequence similarity of 99.92% with the Canadian STRB20 and STRB4 strains infecting strawberries (OR078470, OR811099). The representative sequence of strain W7.07 was deposited in GenBank under accession PX206226, and the sequence of strain O3.16 was deposited under accession PX206227.

The phylogenetic tree constructed from 19 nucleotide sequences of the tuf gene (896 nt), representative of different phytoplasma 16Sr subgroups, and Ureaplasma parvum as an outgroup, confirmed that phytoplasma strains detected in wheat fields O3.16 (W1), O4.21, O4.33 (W2) and W7.07 (W7) were related to subgroup 16SrI-C (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic relationships of the selected phytoplasma strains detected in wheat fields with reference strains, inferred from 896 nt tuf gene sequences. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method and Jones-Taylor-Thornton model of amino acid substitutions. Bootstrap values are expressed as percentages of 1000 replications. Scale bars indicate the number of base substitutions per site. Sequences of detected phytoplasma isolates are marked with circles.

3.6. WDV Detection in Wheat Samples

DAS-ELISA conducted at wheat growth stage BBCH 39 confirmed WDV infection in all symptomatic samples collected from wheat field W1. BYD viruses were not detected in any of these samples. Furthermore, the presence of WDV in phytoplasma-positive plants was verified by duplex PCR. In three out of four phytoplasma-infected wheat plants (W1.22, W1.36, and W1.47), the wheat-adapted WDV-W form was detected, producing DNA amplicons of the expected size (734 bp). In the remaining plant (W7.07), no form of WDV was detected.

In summary, all symptomatic plants collected from field W1 (W1.01-W1.25) were infected with WDV. The symptoms observed in plant W1.22, such as yellowing, stunting, and excessive tillering, were associated with a mixed infection of 16SrI-C phytoplasma and WDV. Notably, asymptomatic samples W1.36 and W1.47 were also confirmed to be co-infected with 16SrI-C phytoplasma and WDV (Table 5).

Table 5.

Wheat samples testing positive for phytoplasmas.

4. Discussion

Wheat and maize play a fundamental role in global food security and livestock feed, making them key crops for pest and pathogen surveillance. Although fungal infections are well-recognized threats to cereal yields, less is known about the role of phytoplasmas in cereal health—particularly in Central Europe. This study fills that gap by presenting the results of molecular testing conducted on wheat and maize crops in southwest Poland.

Using nested PCR and Sanger sequencing targeting the 16S rRNA and tuf genes, we confirmed phytoplasma infection in both symptomatic and asymptomatic wheat plants. The vRFLP and phylogenetic analyses revealed that the detected phytoplasmas belong to subgroup 16SrI-C (heterogeneous 16SrI-(S/R)C), representing the first confirmed occurrence of this subgroup in wheat in Europe. Notably, this strain shares identical 16S and tuf gene sequences with the ‘Ca. Phytoplasma tritici’ strain associated with Wheat Blue Dwarf (WBD) disease in China [14]. This suggests a broader geographic distribution and genetic consistency of WBD-related phytoplasmas across continents. While one infected wheat sample exhibited typical WBD symptoms, the other three appeared asymptomatic. This may be due to varietal resistance or late-stage infection, which is known to limit symptom development. Similar asymptomatic infections have been previously reported in cereals and wild grasses in other regions [20,43].

Interestingly, all visually symptomatic wheat samples from field W1 tested positive for WDV, highlighting the diagnostic challenge posed by overlapping symptomatology. This underscores the importance of integrated virus and phytoplasma screening in cereal disease management. The co-occurrence of WDV and phytoplasmas also raises questions about possible interactions between these pathogens and their vectors.

The identification of a WBD-related phytoplasma strain in Poland—where wheat accounts for more than half of all cereals grown—emphasizes the importance of tracking its potential insect vector. Psammotettix striatus, the known vector of WBD, has been reported in China, Iran, and Spain [12,44,45], but is rarely documented in temperate regions of Europe. Another species, Psammotettix alienus—a common leafhopper in European grasslands and cereal fields, and often historically misidentified as P. striatus—may play a role in transmission [24,46]. Our detection of 16SrI-C phytoplasma in P. alienus individuals collected from wheat fields supports this hypothesis, warranting further vector competency studies.

Finally, although the 16S rRNA gene remains a cornerstone of phytoplasma taxonomy, the presence of two non-identical operons in many strains, including 16SrI-C, can complicate diagnosis. In this study, we employed novel operon-specific primers (RevI-R and RevI-S), enabling successful discrimination of heterogeneous rRNA gene copies. This methodological improvement enhances resolution for molecular diagnostics in phytoplasma studies.

Moreover, the detection of phytoplasmas belonging to subgroups 16SrI-B and 16SrV-C in maize plants in Poland adds to the growing evidence of the expanding host range and geographic distribution of these pathogens. While ‘Ca. Phytoplasma asteris’ (16SrI-B) is well-documented as a causative agent of maize bushy stunt disease (MBS) in Latin America [15,17], reports from Europe have remained scarce, with a single 16SrI-L strain previously identified in Poland [8]. The symptoms observed in infected plants in this study—including reddening of leaves and stunted growth—correspond to those described for MBS [47,48]. Importantly, this study reports, for the first time, the occurrence of subgroup 16SrV-C phytoplasmas in maize plants, which were previously associated with yellows diseases in grapevine, elm, and alder across Europe [49,50]. Phylogenetic and vRFLP analyses confirmed the close relatedness of the maize 16SrV-C strain to those affecting woody hosts, suggesting a potential host jump or vector-mediated spillover.

The sudden rise in the population of Z. scutellaris in maize fields in southwestern Poland, first documented in 2018, represents a noteworthy shift in the regional entomofauna and raises concerns regarding its potential role in the transmission of phytoplasmas. Previously observed only sporadically in Poland, this typically maize associated leafhopper, had primarily been reported in western European countries such as France and the UK [51,52]. Its massive occurrence in the Polish maize fields may signal a north-eastern range expansion, possibly driven by climate change or changes in agricultural practices. Although Z. scutellaris primarily feeds on mesophyll tissues and is not traditionally considered an efficient phytoplasma vector due to the phloem-restricted nature of these pathogens, its feeding behavior includes brief stylet probes into phloem tissues, during which acquisition could theoretically occur [53]. This possibility is supported by our detection of 16SrV-C subgroup phytoplasmas in four individuals of Z. scutellaris. However, the presence of phytoplasma DNA alone does not confirm vector competence, and transmission studies are required to determine whether Z. scutellaris is capable of transmitting these pathogens. Moreover, the documented ability of this species to harbor ‘Ca. Phytoplasma solani’ (XII-A group) phytoplasmas [51,54] further suggests that Z. scutellaris may act as a secondary or incidental vector under certain conditions, though its actual epidemiological role remains to be experimentally verified.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study provides the first molecular evidence of 16SrI-C phytoplasma strains infecting wheat and 16SrI-B and 16SrV-C strains infecting maize in Poland, expanding current knowledge on the distribution and host range of phytoplasmas in Central Europe. Given that only a small number of phytoplasma-positive plants were identified (four in wheat and three in maize), these findings should be regarded as preliminary, and no conclusions about prevalence can be drawn at this stage. In contrast, Mastrevirus hordei (WDV) was more frequently detected and is likely responsible for the symptoms observed in wheat during the stem elongation phase. The emergence of Zyginidia scutellaris as a common maize-associated leafhopper, coupled with its potential to harbor 16SrV-C phytoplasma strains, underscores the need for further research into the vector competence and host adaptation of these phytoplasmas in non-traditional hosts such as maize. Given the central role of cereals in global food and feed production, these findings highlight the importance of continued monitoring, early pathogen detection, and vector surveillance as key components in safeguarding cereal production against emerging disease threats.

Author Contributions

M.J.-Z. and A.Z. conceived and designed the research; M.J.-Z. collected samples and executed the experiments; M.J.-Z., K.T., T.K. and A.Z. carried out the data analysis; A.Z., M.J.-Z., K.T. and B.H.-J. writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Science Centre, grant number 2021/40/C/NZ8/00151 (A.Z.). Additionally, this research was conducted as part of the PhD research program ‘Innowacyjny Doktorat’ no. B020/0011/19 (M.J.-Z.) funded by the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Rao, G.P.; Bertaccini, A.; Fiore, N.; Liefting, L. Phytoplasmas: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria-I: Characterization and Epidemiology of Phytoplasma—Associated Diseases; Springer: Singapore, 2018; ISBN 978-981-13-0119-3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; MacLean, A.M.; Sugio, A.; Maqbool, A.; Busscher, M.; Cho, S.-T.; Kamoun, S.; Kuo, C.-H.; Immink, R.G.; Hogenhout, S.A. Parasitic Modulation of Host Development by Ubiquitin-Independent Protein Degradation. Cell 2021, 184, 5201–5214.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alma, A.; Lessio, F.; Nickel, H. Insects as Phytoplasma Vectors: Ecological and Epidemiological Aspects. In Phytoplasmas: Plant Pathogenic Bacteria—II: Transmission and Management of Phytoplasma—Associated Diseases; Bertaccini, A., Weintraub, P.G., Rao, G.P., Mori, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-981-13-2832-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bertaccini, A. Phytoplasmas: Diversity, Taxonomy, and Epidemiology. Front. Biosci. 2007, 12, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Lee, I.M.; Davis, R.E.; Suo, X.; Zhao, Y. Automated RFLP Pattern Comparison and Similarity Coefficient Calculation for Rapid Delineation of New and Distinct Phytoplasma 16Sr Subgroup Lineages. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008, 58, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhao, Y. Phytoplasma Taxonomy: Nomenclature, Classification, and Identification. Biology 2022, 11, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.; Miyata, S.I.; Oshima, K.; Kakizawa, S.; Nishigawa, H.; Wei, W.; Suzuki, S.; Ugaki, M.; Hibi, T.; Namba, S. First Complete Nucleotide Sequence and Heterologous Gene Organization of the Two rRNA Operons in the Phytoplasma Genome. DNA Cell Biol. 2003, 22, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwolińska, A.; Borodynko-Filas, N. Intra and Extragenomic Variation between 16S rRNA Genes Found in 16SrI-B-related Phytopathogenic Phytoplasma Strains. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2021, 179, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katanić, Z.; Krstin, L.; Jezić, M.; Zebec, M.; Ćurković-Perica, M. Molecular Characterization of Elm Yellows Phytoplasmas in Croatia and Their Impact on Ulmus spp. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 1430–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, O.; Contaldo, N.; Paltrinieri, S.; Kawube, G.; Bertaccini, A.; Nicolaisen, M. DNA Barcoding for Identification of “Candidatus Phytoplasmas” Using a Fragment of the Elongation Factor Tu Gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Lee, I.M.; Bottner, K.D.; Zhao, Y.; Botti, S.; Bertaccini, A.; Harrison, N.A.; Carraro, L.; Marcone, C.; Khan, A.J.; et al. Ribosomal Protein Gene-Based Phylogeny for Finer Differentiation and Classification of Phytoplasmas. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2037–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.F.; Hao, X.G.; Li, Z.N.; Gu, P.W.; An, F.Q.; Xiang, J.Y.; Wang, H.N.; Luo, Z.P.; Liu, J.J.; Xiang, Y. Identification of the Phytoplasma Associated with Wheat Blue Dwarf Disease in China. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.-T.; Kung, H.-J.; Huang, W.; Hogenhout, S.A.; Kuo, C.-H. Species Boundaries and Molecular Markers for the Classification of 16SrI Phytoplasmas Inferred by Genome Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, W.; Davis, R.E.; Lee, M.; Bottner-Parker, K.D. The Agent Associated with Blue Dwarf Disease in Wheat Represents a New Phytoplasma Taxon,‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Tritici. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, D.G.; Villar, C.M.; Suarez, G.T.; Esteban, W.D.I.; Contaldo, N.; Lozano, E.C.C.; Bertaccini, A. Diverse Phytoplasmas Associated with Maize Bushy Stunt Disease in Peru. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 163, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, J.; Cvrković, T.; Mitrović, M.; Krnjajić, S.; Petrović, A.; Redinbaugh, M.G.; Pratt, R.C.; Hogenhout, S.A.; Toševski, I. Stolbur Phytoplasma Transmission to Maize by Reptalus Panzeri and the Disease Cycle of Maize Redness in Serbia. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlovskis, Z.; Canale, M.C.; Haryono, M.; Lopes, J.R.S.; Kuo, C.H.; Hogenhout, S.A. A Few Sequence Polymorphisms among Isolates of Maize Bushy Stunt Phytoplasma Associate with Organ Proliferation Symptoms of Infected Maize Plants. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.; Esteves, M.B.; Cortés, M.T.B.; Lopes, J.R.S. Maize Bushy Stunt Phytoplasma Favors Its Spread by Changing Host Preference of the Insect Vector. Insects 2020, 11, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosovac, A.; Rekanović, E.; Ćurčić, Ž.; Stepanović, J.; Duduk, B.; Kosovac, A.; Rekanović, E.; Ćurčić, Ž.; Stepanović, J.; Duduk, B. Plants under Siege: Investigating the Relevance of ‘Ca. P. Solani’ Cixiid Vectors through a Multi-Test Study. Plants 2023, 12, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollingsworth, C.R.; Atkinson, L.M.; Samac, D.A.; Larsen, J.E.; Motteberg, C.D.; Abrahamson, M.D.; Glogoza, P.; MacRae, I.V. Region and Field Level Distributions of Aster Yellows Phytoplasma in Small Grain Crops. Plant Dis. 2008, 92, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfrieme, A.-K.; Will, T.; Pillen, K.; Stahl, A. The Past, Present, and Future of Wheat Dwarf Virus Management—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parizipour, M.G.; Behjatnia, S.; Afsharifar, A.; Izadpanah, K. Natural Hosts and Efficiency of Leafhopper Vector in Transmission of Wheat Dwarf Virus. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 98, 483–492. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Liu, L.; Chen, G.; Yang, H.; Huang, L.; Gong, G.; Luo, P.; Zhang, M. Molecular Evolution and Phylogeographic Analysis of Wheat Dwarf Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1314526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, L.; Isidoro, N.; Riolo, P. Natural Phytoplasma Infection of Four Phloem-Feeding Auchenorrhyncha Across Vineyard Agroecosystems in Central-Eastern Italy. J. Econ. Entomol. 2013, 106, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, J., III; Rajotte, E.; Rosa, C. The Past, Present, and Future of Barley Yellow Dwarf Management. Agriculture 2019, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbini, F.M.; Siddell, S.G.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; Mushegian, A.R.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Dempsey, D.M.; Dutilh, B.E.; García, M.L.; Hendrickson, R.C. Changes to Virus Taxonomy and the ICTV Statutes Ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2023). Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzmiel, K. Identification of Barley Yellow Dwarf Viruses in Poland. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 99, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Trzmiel, K.; Hasiów-Jaroszewska, B. Molecular Characteristics of Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus—PAS—The Main Causal Agent of Barley Yellow Dwarf Disease in Poland. Plants 2023, 12, 3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, R.; Niedringhaus, R. Die Zikaden Deutschlands: Bestimmungstafeln Für Alle Arten; Wabv-Fründ: Scheeßel, Germany, 2004; ISBN 3-939202-00-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, W.; Lee, I.-M.; Shao, J.; Suo, X.; Davis, R.E. Construction of an Interactive Online Phytoplasma Classification Tool, iPhyClassifier, and Its Application in Analysis of the Peach X-Disease Phytoplasma Group (16SrIII). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2582–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.M.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E.; Davis, R.E.; Bartoszyk, I.M. Revised Classification Scheme of Phytoplasmas Based on RFLP Analyses of 16S rRNA and Ribosomal Protein Gene Sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998, 48, 1153–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.J.; Hiruki, C. Amplification of 16S Ribosomal-RNA Genes from Culturable and Nonculturable Mollicutes. J. Microbiol. Methods 1991, 14, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, K.S.; Padovan, A.C.; Mogen, B.D. Studies on Sweet-Potato Little-Leaf Phytoplasma Detected in Sweet-Potato and Other Plant-Species Growing in Northern Australia. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Seemüller, E.; Smart, C.D.; Kirkpatrick, B.C. Phylogenic Classification of Plant Pathogenic Mycoplasmalike Organisms or Phytoplasmas. In Molecular and Diagnostic Procedures in Mycoplasmology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K.; Schneider, B.; Ahrens, U.; Seemüller, E. Detection of the Apple Proliferation and Pear Decline Phytoplasmas by PCR Amplification of Ribosomal and Nonribosomal DNA. Phytopathology 1995, 85, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, D.E.; Lee, I.-M. Ultrasensitive Detection of Phytoplasmas by Nested-PCR Assays Using Two Universal Primer Pairs. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 1996, 35, 114–151. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Gibb, K.S.; Seemuller, E. Sequence and RFLP Analysis of the Elongation Factor Tu Gene Used in Differentiation and Classification of Phytoplasmas. Microbiology 1997, 143, 3381–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. Clustal-W—Improving the Sensitivity of Progressive Multiple Sequence Alignment Through Sequence Weighting, Position-Specific Gap Penalties and Weight Matrix Choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Version 12 for Adaptive and Green Computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.F.; Adams, A. Characteristics of the Microplate Method of Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for the Detection of Plant Viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1977, 34, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzmiel, K. Occurrence of Wheat Dwarf Virus and Barley Yellow Dwarf Virus Species in Poland in the Spring of 2019. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2020, 60, 345–350. [Google Scholar]

- Trzmiel, K.; Klejdysz, T. Detection of Barley-and Wheat-Specific Forms of Wheat Dwarf Virus in Their Vector Psammotettix Alienus by Duplex PCR Assay. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2018, 58, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolińska, A.; Krawczyk, K.; Borodynko-Filas, N.; Pospieszny, H. Non-Crop Sources of Rapeseed Phyllody Phytoplasma (“Candidatus Phytoplasma Asteris”: 16SrI-B and 16SrI-(B/L)L), and Closely Related Strains. Crop Prot. 2019, 119, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llácer, G.; Medina, V.; Archelós, D. A Survey of Potential Vectors of Apricot Chlorotic Leaf Roll. Agronomie 1988, 8, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Siampour, M.; Esmailzadeh Hosseini, S.; Bertaccini, A. Characterization and Vector Identification of Phytoplasmas Associated with Cucumber and Squash Phyllody in Iran. Bull. Insectology 2015, 68, 311–319. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.; Stewart, A.; Biedermann, R.; Nickel, H.; Niedringhaus, R. The Planthoppers and Leafhoppers of Britain and Ireland Identification Keys to All Families and Genera and All British and Irish Species Not Recorded from Germany; Wabv-Fründ: Scheeßel, Germany, 2015; ISBN 9783939202066. [Google Scholar]

- Galvão, S.R.; Sabato, E.O.; Bedendo, I.P. Occurrence and Distribution of Single or Mixed Infection of Phytoplasma and Spiroplasma Causing Corn Stunting in Brazil. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 46, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Lopez, E.; Olivier, C.Y.; Luna-Rodriguez, M.; Rodriguez, Y.; Iglesias, L.G.; Castro-Luna, A.; Adame-Garcia, J.; Dumonceaux, T.J. Maize Bushy Stunt Phytoplasma Affects Native Corn at High Elevations in Southeast Mexico. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016, 145, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, J.; Cvrković, T.; Mitrović, M.; Petrović, A.; Krstić, O.; Krnjajić, S.; Toševski, I. Multigene Sequence Data and Genetic Diversity among ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma Ulmi’ Strains Infecting Ulmus spp. in Serbia. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malembic-Maher, S.; Desqué, D.; Khalil, D.; Salar, P.; Bergey, B.; Danet, J.-L.; Duret, S.; Dubrana-Ourabah, M.-P.; Beven, L.; Ember, I.; et al. When a Palearctic Bacterium Meets a Nearctic Insect Vector: Genetic and Ecological Insights into the Emergence of the Grapevine Flavescence Dorée Epidemics in Europe. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1007967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fos, A.; Danet, J.L.; Zreik, L.; Garnier, M.; Bove, J.M. Use of a Monoclonal-Antibody to Detect the Stolbur Mycoplasma-like Organism in Plants and Insects and to Identify a Vector in France. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczey, N.; Masters, G.J.; Hollier, J.A.; Mortimer, S.R.; Brown, V.K. Community Associations of Chalk Grassland Leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha): Conclusions for Habitat Conservation. J. Insect Conserv. 2005, 9, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marion-Poll, F.; Giustina, W.D.; Mauchamp, B. Changes of Electric Patterns Related to Feeding in a Mesophyll Feeding Leafhopper. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1987, 43, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batlle, A.; Martínez, M.A.; Laviña, A. Occurrence, Distribution and Epidemiology of Grapevine Yellows in Spain. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2000, 106, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).