Abstract

Chickpeas are a pulse crop that originated in Eurasia and are a source of protein for many people. The objective of this research is to select stable, high-yielding chickpea genotypes using uni- and multivariate methods of adaptability and stability analysis. Fifteen genotypes were tested in the 2020 and 2021 agricultural years. The experimental design was a completely randomized block design with three replications. The collected data were yield (kg/ha) values, and the stability analyses were performed using Eberhart and Russell’s, Lin and Binns’s modified by Carneiro’s, additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI), and weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) methods. The average sum of ranks (ASR) was then calculated by ranking genotypes according to their yield and stability indices. The AMMI analysis of variance showed significant effects (p < 0.05) for environments, genotypes, and the interaction between genotypes and environments. From AMMI, the first three principal components (PCs) had significant effects, and the cumulative variance on the PC1 and PC2 axes was 86%. FLIP02-23C, FLIP03-109C, and Jamu 96 had the lowest ASR, indicating that these genotypes are the most stable and productive chickpea genotypes. According to AMMI2, genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C could be adapted to irrigated environments.

1. Introduction

The word “pulse” originates from the Latin “puls”, which means thick soup or thick slurry [1]. In agronomy, pulses refer to the dry, edible seeds of leguminous plants [2]. Crop pulses include bambara beans, dry beans, faba beans, chickpeas, cowpeas, dry peas, pigeon peas, lentils, lupins, and vetches [3]. Among those crops, chickpea (CP) (Cicer arietinum L.) is the most important pulse species [4] and is a good source of proteins and carbohydrates, fiber, essential minerals, and vitamins, which are all properties related to the maintenance of good health [5].

CP is produced worldwide in more than 50 countries, and the five largest producers are India, Australia, Turkey, Ethiopia, and Russia [6]. Regarding their grain characteristics, CPs can be divided into two types: “Desi” and “Kabuli”. The “Desi” type has pigmented plants, light purple flowers, and darker seeds, while the “Kabuli” type typically has white flowers and beige seeds [7]. The most significant production is from Desi types, which are grown in South Asia, East Africa, and Australia, whereas Kabuli types are grown in the Mediterranean Basin, the Near East, and East Asia [8]. Regarding biotic stresses, the principal component of loss production is fungal diseases, highlighting the importance of Fusarium wilt and Ascochyta blight [9]. On the other hand, the effects of heat, cold, drought, and salinity could be detrimental to yield [10]. In this context, the most effective way to address these concerns is to develop new cultivars of CP [11].

Crops, including CP, are significantly influenced by the environment, and the performance of a cultivar is not solely determined by its genotype. Instead, it is often more influenced by the complex interaction between the genotype and environment (GEI) [12]. To estimate the effects of GEI, elite lines are commonly evaluated in multi-environment trials (METs), which aid in making genotype recommendations. Pour-Aboughadareh et al. [13] define METs as experiments in which a set of genotypes is evaluated across different environments, such as years, locations, planting dates, or combinations of these. Various statistical methods are employed to estimate adaptability and stability. These methods serve the crucial purpose of providing a quantitative understanding of how cultivars respond to different environments, each with its own set of assumptions [13].

Genotype stability is studied using several methods, and these methods have distinct assumptions, such as those of analysis of variance (ANOVA) [14] and simple linear regression [15,16]. However, these methods have some weaknesses [13]. Firstly, ANOVA is based on an additive model, which may not accurately reflect how genotypes and environments interact to influence GEI. The complex nature of these interactions needs a more advanced statistical approach than ANOVA for a better understanding of the phenomena. Secondly, linear regression analysis loses its efficiency when the assumption of linearity is missed. Furthermore, these analyses are highly influenced by the tested genotypes and environments, and attempting to fit the effects of interactions in a single dimension thereby reduces the effectiveness of the response models [17].

Alternative methods to ANOVA and linear regression analyses are additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) [18] and the weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) [19]. In addition, nonparametric methods, like those developed by Annicchiarico [20] and Huehn [21], provide viable options. Another choice is Lin and Binns’s method [22], modified by Carneiro [23], where the statistic Pi is partitioned into suitable (Pi+) and unsuitable (Pi−) environments.

The AMMI model uses analysis of variance (ANOVA) for additive or main effects, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) for multiplicative or interactive effects [24]. It makes AMMI a powerful method for analyzing GEI in multi-environment trials (METs), as it estimates the effect of GEI for each genotype and environment [18]. Currently, a new approach defined as WAASB has been introduced, which merges the strengths of AMMI with the mixed model BLUP (best linear unbiased predictor) techniques. In addition to the benefits of utilizing random effects, WAASB accounts for the whole variability, rendering a biplot highly comprehensive [19]. It is important to consider that the selection of the methodology is influenced by the number of available environments, the level of required precision, and the nature of the data [17].

In the last five years, several studies have been conducted concerning GEI in chickpeas. In this sense, Karimizadeh et al. [25] found significant effects of E, G, and GEI on grain yield. Similar findings were observed in [26] for yield and drought tolerance, in [27] for yield and seed size, in [28] for yield and heat tolerance, in [29] for yield, protein concentration, and seed weight, and in [30] for yield components in lineages from interspecific crosses. In addition, the majority of them analyzed GEI using AMMI, genotype-plus-genotype × environment (GGE), and WAASB [25,26,27,28,29,30].

In this context, this research aims to select stable, high-yielding chickpea genotypes using uni- and multivariate methods of analysis and to study their adaptation to various environmental conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Conditions

The trials were conducted in the fall and winter of two agricultural years: 2020 and 2021. The 2020 essays were conducted at Embrapa Hortaliças, Rodovia BR-060, Km 9, DF, Brazil, on four different planting dates. These planting dates were chosen based on chickpea cultivation and soil moisture from the previous rainfall season. Moreover, the 2021 trials were conducted at Futurama Farm, located on Rodovia BR 251, km 13, Cristalina—GO, Brazil, on three different planting dates. In this case, the planting dates were selected based on the viability of the maize, chickpea, and cotton crop arrangement. The environments were a combination of locations and planting dates, and their main characteristics are shown in Table 1. The experimental areas were prepared by plowing and furrowing, and the fertilization of environments E1 to E3 was 15 kg per hectare of nitrogen, 75 kg per hectare of phosphorus, and 45 kg per hectare of potassium. A top-dressing application of 100 kg per hectare of nitrogen was performed thirty days after sowing. Regarding E4–E7, basal fertilization was 25 kg per hectare of nitrogen, 60 kg per hectare of phosphorus, and 35 kg per hectare of potassium. The same amount of top dressing was applied to these fields. In all environments, weeds were managed with 1920 g of glyphosate (Bayer Crop Science, Belford Roxo, Brazil) + 480 g of metribuzin per hectare (Syngenta, Paulinia, Brazil), followed by 100 g of carfentrazone-ethyl (FMC, Uberaba, Brazil) per hectare for pre-planting desiccation and 1920 g per hectare of S-metolachlor (Syngenta, Paulinia, Brazil) in post-emergence. Cotton bollworm infestation was managed by spraying 600 g per hectare of methamidophos (Arysta, Salto do Pirapora, Brazil), followed by 20 g per hectare of lufenuron (Syngenta, Paulinia, Brazil).

Table 1.

Environments (E), planting dates, locations, and water management of the experimental trials.

Treatments were composed of seven cultivars: Astro, Blanco Sinaloa, Cícero, IAC Marrocos, Joly, Jamu 96, and Nacional 29; six homozygous lines from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA): ILC 1929, FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, FLIP06-155C, and FLIP06-34C; and two homozygous lines from the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT): ICCV 10 and BG1392. Genotype details used in this research are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Details of chickpea genotypes studied in this research.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experimental design was completely randomized with three replications. The experimental plots consisted of four lines of each genotype, each 5 m in length. The spacing was 0.10 m between plants and 0.50 m between rows of plants. The sowing density was 40 seeds per square meter. To determine yield, grain from the plots was harvested, cleaned, and weighed. As the results were expressed in g/7.5 m2, the yield was finally converted to kg/ha.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical model for Eberhardt and Russell’s [15] analysis is as follows:

where is observed mean of genotype i in environment j; is general mean of genotype i; is coefficient of regression of genotype i and is environmental index j; is deviation of the regression of genotype i in environment j; and is mean error associated with the average. In addition, is calculated as follows:

where n is the number of environments.

In Lin and Binns’s [22] procedure the index Pi is calculated as follows:

where Pi is the superiority index of genotype i; Xij is the number of days to anthesis of genotype i in environment j; Mj is the number of days to anthesis of the genotype with the maximum response among all genotypes in environment j; and n is the number of environments.

In additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) [18] method is as follows:

where = mean response of genotype i (i = 1, 2,…, g genotypes) in environment j (j = 1, 2,…, e environments); = general mean of the experiments; = fixed effect of genotype i; n = number of principal axes (principal components) needed to describe the pattern of the interaction between the i-eth genotype with the j-eth environment; = fixed effect of environment j; = k-eth single value of the original interactions matrix (called G X E matrix); = is the value corresponding to the i-eth genotype in the k-eth single vector column of G X E matrix; = value corresponding to the j-eth environment in the k-eth single vector (row vector) of G X E matrix; noise associated with the (ga)ij term of classic interaction of i-eth genotype with j-eth environment; and = mean experimental error.

The weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) [19] method comprises the following:

where WAASBG is the weighted average of absolute scores of the genotype g, IPCAgn is the score of the genotype g in the nth interaction principal component axis (IPCA), and EPn is the amount of the variance explained by the nth IPCA.

Individual and joint analyses of variance were performed using SAS PROC GLM (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [31] at p < 0.05. The individual effects of genotype/environment and environment were analyzed using Scott and Knott’s [32] method at p < 0.05. Details of the calculation of degrees of freedom for the AMMI analysis of variance are presented in Table S1 (Supplementary Material). Once the genotype-by-environment interaction was significant (p < 0.05), stability analyses were performed according to the protocols of AMMI [18], Eberhardt and Russell [15], Lin and Binns [22], and WAASB from the singular value decomposition of the matrix of the best linear unbiased predictor (BLUP) for the genotype x environmental (GxE) effects generated by a linear mixed model [19]. AMMI and WAASB analyses were run with the R 3.5.2 package metan [33] using the statistical program R Core Team. Eberhardt and Russell’s and Lin and Binns’s analyses were performed in Genes statistical software (version 1990. 2023. 92, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, Viçosa, Brazil) [34].

3. Results

The results of the combined analysis of variance are shown in Table 3. From this analysis, highly significant effects (p < 0.01) were observed for environment (E), genotype (G), and the genotype-by-environment interaction (GEI). Moreover, the partitioning of the total square sum (SST) accounted for 86.25% of the effects due to E, G, and GEI. Hence, E corresponded to 24.55%, G to 34.87%, and GEI to 26.93% of SST (Table 3). Yields of genotypes in the studied environments are presented in Table 4. In four of seven environments (E1, E3, E5, and E6), genotypes were divided into three groups, with Astro, Blanco Sinaloa 92, BG 1392, and Cícero showing the lowest yields. The remaining genotypes did not show a clear trend and changed positions in yield performance (Table 4). It is also possible to note the composition of four clusters of environments, with E6 and E7 showing the highest mean yields, whereas E2 and E4 showed the lowest (Table 4). The significance of GEI is evident in the differences between genotypes across environments, ranging from 20.67 kg/ha in environment E2 (ICCV 10) to 1161.33 kg/ha in environment E6 (FLIP03-109C). Regarding Eberhardt and Russell’s environmental index, E1, E5, E6, and E7 were considered favorable environments, whereas E2, E3, and E4 were in an unfavorable cluster (Table 4).

Table 3.

Additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) analysis of variance for chickpea yield during the 2020–2021 agricultural years.

Table 4.

Yield (Kg/ha) of 15 chickpea genotypes across seven environments during the 2020–2021 agricultural years.

As shown in Table 5, FLIP03-109C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C exhibited the highest yields. The genotypes were separated into three categories according to regression coefficients (. Hence, FLIP06-34C, IAC Marrocos, ICCV 10, ILC 1929, and Jamu 96 had ; FLIP03-35C, FLIP06-155C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP03-109C had ; and Astro, Blanco Sinaloa 92, BG 1392, Cícero, IAC Marrocos, Joly, and Nacional 29 had . Astro, Blanco Sinaloa 92, BG 1392, Cícero, FLIP03-109C, Jamu 96, Joly, and Nacional 29 did not have significant variance of regression deviation () (p < 0.05). Only FLIP03-35C, FLIP06-155C, FLIP02-23C, FLIP03-109C, and Jamu 96 had a coefficient of determination (R2) superior to 80%. The lowest Pi’s were found in FLIP02-23C and FLIP03-109C, and these cultivars did not exhibit the same trend for weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB Index), as the lowest estimates were observed in IAC Marrocos, ICCV 10, and Jamu 96. Finally, genotypes with the lowest average sum of ranks (ASR) were FLIP02-23C, FLIP03-109C, and Jamu 96. The advantage of using the ASR is the integration of yield and several methods of stability analysis in a single number. Thus, it facilitates the interpretation of adaptability and stability indices and the selection of stable genotypes.

Table 5.

Stability and adaptability statistics for chickpea yield estimated in seven environments during the 2020–2021 agricultural years.

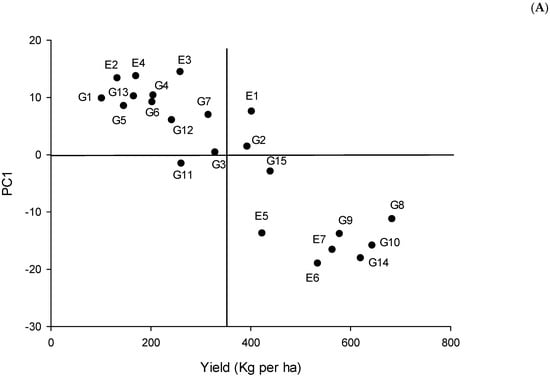

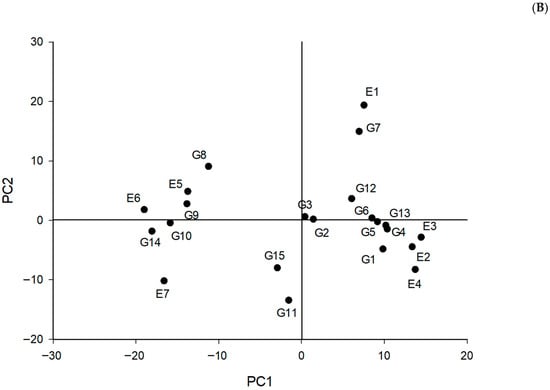

Regarding additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) analysis of variance, the GEI was split into six principal components (PCs). The first three PCs had significant effects—at least p < 0.05—and the remaining PCs were not significant. In this sense, PC1 accounted for 74% of the total variation, PC2 for 12.6%, PC3 for 5.8%, PC4 for 4.3%, PC5 for 2.4%, and finally PC6 for 0.9% (Table 3). In AMMI 1, the abscissa describes the yield means, while the ordinate represents the IPCA1 scores of each chickpea genotype. The graph’s origin indicates an average yield and no genotype-by-environment interaction. Coordinates on the right yielded greater results than those on the left. The farther the coordinate is from the abscissa, the less stable it is (Figure 1A). Environment E6 had the greatest influence on yield because it is the farthest from the origin, followed by environments 2 and 4. On the other hand, E1 is the closest environment to the origin, meaning it had little influence on yield. Similarly, genotype Jamu 96 (G3) is the closest to the origin, followed by IAC Marrocos (G2), ICCV 10 (G11), and FLIP06-34C (G15) (Figure 1A). Genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C showed yields greater than the general mean. On the other hand, the environments with the lowest yield were E2, E3, and E4.

Figure 1.

Chickpea yield, and stability analysis based on (A) the AMMI1 biplot and (B) the environmental stability GGE biplot. The genotypes codes are G1: Cícero, G2: IAC Marrocos, G3: Jamu 96, G4: Nacional 29, G5: Astro, G6: Joly, G7: ILC 1929, G8: FLIP03-109C, G9: FLIP03-35C, G10: FLIP02-23C, G11: ICCV 10, G12: Blanco Sinaloa 92, G13: BG 1392, G14: FLIP06-155C, and G15: FLIP06-34C.

The AMMI2 biplot shows the effects of genotype-by-environment interaction on genotype ranking. In this case, genotypes farther from the origin exhibit greater genotype-by-environment interaction and thus lower stability. From the biplot AMMI 2 (Figure 1B), a great divergence can be observed between environments E4 and E7, and similarly between genotypes FLIP06-155C (G14) and Nacional 29 (G4). Moreover, the coordinates based on environments and genotypes are shown on AMMI2 (Figure 1B). In this sense, cultivars IAC Marrocos and Jamu 96 were close to the origin. Additionally, FLIP03-35C was close to E5, and Cícero, Nacional 29, and BG 1392 were plotted next to E2, E3, and E4 (Figure 1B).

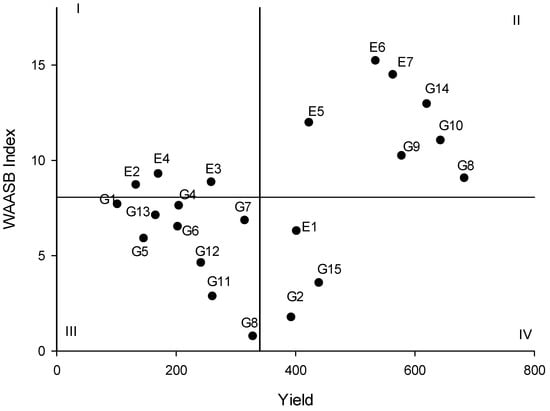

Genotypes and environments were plotted in a weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) statistics dispersion graph based on their mean yield and stability values. As proposed by Yue et al. [24], the coordinates of environments and genotypes were plotted on a dispersion graph across four regions. Environments E2, E3, and E4 were placed in the first quadrant, and the second quadrant contained enclosed environments E5, E6, and E7, along with genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C. Following the analysis, Cícero, Nacional 29, Astro, Joly, ILC 1929, FLIP03-109C, ICCV 10, Blanco Sinaloa 92, and BG 1392 belonged to the third quadrant. In the last quadrant, environment E1 and the genotypes FLIP06-34C and IAC Marrocos were identified (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Biplot of chickpea yield vs. weighted average of the absolute scores (WAASB Index). The genotype codes are G1: Cícero, G2: IAC Marrocos, G3: Jamu 96, G4: Nacional 29, G5: Astro, G6: Joly, G7: ILC 1929, G8: FLIP03-109C, G9: FLIP 3-35C, G10: FLIP02-23C, G11: ICCV 10, G12: Blanco Sinaloa 92, G13: BG 1392, G14: FLIP06-155C, and G15: FLIP06-34C.

4. Discussion

As found in the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) analysis of variance, the highly significant effect of genotype-by-environment interaction (GEI) (linear) indicates low similarity among genotypes in the studied environments [35]. The effects of GEI on genotype performance, in the present case estimated by yield, make the selection of broadly adapted genotypes difficult [36]. One of these effects is the reduction in the yield heritability. In addition, significant GEI for complex traits, such as yield, poses a challenge to selection, making it difficult to develop newly adapted chickpea cultivars [8].

Considering that the effects of the linear environment were significant (p < 0.01), environmental variations can promote shifts in genotype yields [17]. It is also observed that, when a linear environment is significant, the regression coefficients (obtained from Eberhardt and Russel [15]) among genotypes differ [37]. Furthermore, the yield stability can be influenced by both linear and non-linear effects, as evidenced by the significant pooled deviation. Considering these aspects, analyzing the data using multivariate and nonparametric approaches could enrich the research [38].

Differences among the environmental indexes (p < 0.05) were analyzed from −222.12 to +208.50, reflecting an average yield in the environments ranging from 563.29 Kg/ha to 132.67 Kg/ha. In this case, Molina et al. [39,40] and Istanbuli et al. [41] highlighted the importance of water supply to chickpeas, and these authors also observed reductions in yield up to 70%. Hence, a comprehensive study of the influence of water supply on chickpea yield in an experiment with fewer genotypes could be a follow-up to this study. Environments E2 and E7 had the highest and lowest mean yields, respectively, and the difference between them was 430 Kg/ha. This result could be particularly helpful for chickpea growers, especially in cultivation under unfavorable environments. In this case, considering the following aspects—high variation in the trait per se, stability, and adaptability—could help develop high-yield chickpea genotypes and improve yield stability performance [42].

As mentioned by Pour-Aboughadareh et al. [42], considering the GEI effect on the breeding programs increases the efficiency of selection processes and identifies genotypes with high adaptability and stability. Hence, estimates of adaptability and stability are important for selecting superior genotypes. According to Eberhardt and Russell’s methodology [19], genotypes are classified using criteria based on regression coefficients, the variance of the regression deviations, and the magnitude of the coefficient of determination. FLIP03-35C, FLIP06-155C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP03-109C tend to be adapted to favorable environments, as they have > 1 and yield superior to the general mean. On the other hand, an important observation should be made regarding IAC Marrocos’s specific adaptation to unfavorable environments and its performance in terms of yield, despite the low regression coefficient. None of the evaluated genotypes has broad adaptability ( = 1) and predictable responses ( = 0) according to Eberhardt and Russell’s recommendations. However, this concept might be redesigned to select genotypes with high expression of the trait under unfavorable environments, which is more efficient than searching for genotypes with = 1 [43]. These authors also pointed out that these genotypes ( = 1) can perform less under unfavorable environments than those with < 1, for example. Another option is to associate highly predictable genotypes with high trait performance using an R2 greater than 80% as the criterion, instead of the original = 0 [44].

Regarding the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction 1 (AMMI1) biplot, the genotypes Cícero, Jamu 96, Nacional 29, Astro, Joly, ILC 1929, ICCV 10, Blanco Sinaloa 92, and BG 1392 had the lowest yields. This finding can be attributed to the fact that these genotypes are not well adapted to the edaphic conditions of the Brazilian Cerrado region. Considering the AMMI2 model, cultivars IAC Marrocos and Jamu 96, according to Zobel et al. [18], are stable. However, a remark posted by Danakumara [28] should be considered, which suggests that the selection process should consider not only stability aspects but also yield.

Regarding the weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) analysis, only environments were located in the first quadrant of the biplot, indicating that they have a greater influence on GEI [13]. In the following quadrant (II), genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C could be considered unstable, although they exhibit high performance in yield [45]. Moreover, environments 5 through 7 are the most suitable for selecting chickpeas based on yield. The third quadrant encompasses the majority of tested genotypes, and these are characterized as low-performance and widely adapted genotypes due to their lower values of WAASB [19]. Also, no environments were placed in the third quadrant. In the last quadrant (IV), the cultivars IAC Marrocos and FLIP06-34C could be considered stable with yields above the general mean, and environment E1 is favorable but with low discrimination power [45]. Moreover, environments E2 to E4 were classified as unsuitable environments based on Eberhardt and Russell, AMMI, and WAASB protocols.

According to Wicaksana et al. [46], one way to overcome genotype selection based on a single statistic is to use the average sum of ranks (ASR), in which lower values indicate greater stability. In the present case, the advantage of using ASR is that it involves yield values and stability, facilitating the selection of high-yielding, stable genotypes. In this sense, FLIP02-23C, FLIP03-109C, and Jamu 96 were the most stable genotypes found in this research. Also, genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C appear to be better adapted to irrigated environments (E5 to E7), achieving the highest yields in these sites.

5. Conclusions

In this research, the stability of the yield of 15 chickpea genotypes was evaluated in multi-environment trials using additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI), Eberhart and Russell’s, Lin and Binns’s, and weighted average of absolute scores (WAASB) techniques. From the AMMI analysis of variance, it was observed that yield was influenced by genotype, environment, and the interaction between genotype and environment (GEI). Using the average sum of ranks is an interesting approach to combine the results of several methodologies for GEI estimation. Based on this, FLIP02-23C, FLIP03-109C, and Jamu 96 were found to be the most stable genotypes in this research. According to AMMI2, genotypes FLIP03-109C, FLIP03-35C, FLIP02-23C, and FLIP06-155C are adapted to irrigated environments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242572/s1, Table S1: Equations for degrees of freedom of AMMI analysis of variance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A. and F.A.S.; methodology, G.O.S., F.A.S., and C.R.S.; formal analysis G.O.S., F.A.S., N.R.Q. and O.A.; investigation, O.A., N.R.Q. and F.A.S.; resources, F.A.S.; data curation, G.O.S., F.A.S., N.R.Q. and O.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.O.S. and F.A.S.; writing—review and editing, G.O.S. and F.A.S.; supervision, W.M.N. and F.A.S.; project administration, F.A.S.; funding acquisition, F.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charges were funded by Fundação De Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAP-DF), grant number SEI 00193-00002045/2025-29.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Fábio Akiyoshi Suinaga, Giovani Olegário da Silva, and Warley Marcos Nascimento were employed by Embrapa Hortaliças (CNPH). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted without commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Asif, M.; Rooney, L.W.; Ali, R.; Riaz, M.N. Application and Opportunities of Pulses in Food System: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, G.; Jesus, E.; Dias, A.; Coelho, M.; Molina, Y.; Rumjanek, N. Contribution of Biofertilizers to Pulse Crops: From Single-Strain Inoculants to New Technologies Based on Microbiomes Strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, A.; Liu, K. A Global Meta-Analysis of Pulse Crop Effect on Yield, Resource Use, and Soil Organic Carbon in Cereal- and Oilseed-Based Cropping Systems. Field Crops Res. 2023, 294, 108857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, A. Impact of Climate Change on Pulse Production and It’s Mitigation Strategies. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2021, 15, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Khan, Q.U.; Liu, L.G.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Haq, I.U. Nutritional Composition, Health Benefits and Bio-Active Compounds of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1218468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Xiao, S.; Li, Z.; Zhou, K.; Fu, Y. Chemical Composition of Kabuli and Desi Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Cultivars Grown in Xinjiang, China. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eker, T.; Sari, D.; Sari, H.; Tosun, H.S.; Toker, C. A Kabuli Chickpea Ideotype. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.K.; Jain, S.K.; Dubey, A.K.; Kumar, J.; Sharma, M.; Gupta, K.C.; Sharma, L.D.; Prakash, V.; Kumar, S. Conventional and Molecular Breeding for Disease Resistance in Chickpea: Status and Strategies. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2023, 39, 193–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriagada, O.; Cacciuttolo, F.; Cabeza, R.A.; Carrasco, B.; Schwember, A.R. A Comprehensive Review on Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Breeding for Abiotic Stress Tolerance and Climate Change Resilience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurumurthy, S.; Ashu, A.; Kruthika, S.; Solanke, A.P.; Basavaraja, T.; Soren, K.R.; Rane, J.; Pathak, H.; Prasad, P.V.V. An Innovative Natural Speed Breeding Technique for Accelerated Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Generation Turnover. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavo, A.; Mauromicale, G.; Ierna, A. Dissecting the Genotype × Environment Interaction for Potato Tuber Yield and Components. Agronomy 2022, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Khalili, M.; Poczai, P.; Olivoto, T. Stability Indices to Deciphering the Genotype-by-Environment Interaction (GEI) Effect: An Applicable Review for Use in Plant Breeding Programs. Plants 2022, 11, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wricke, G. Uber Eine Methode Zur Erfassung Der Okologischen Streubreite in Feldversucen. Z. Pflanzenzucht. 1962, 47, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, S.T.; Russell, W.A. Stability Parameters for Comparing Varieties 1. Crop Sci. 1966, 6, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, K.W.; Wilkinson, G.N. The Analysis of Adaptation in a Plant-Breeding Programme. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1963, 14, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.D. Modelos Biometricos Aplicados Ao Melhoramento Geneticos; Editora UFV: Viçosa, Brazil, 2002; ISBN 978-85-7269-151-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zobel, R.W.; Wright, M.J.; Gauch, H.G. Statistical Analysis of a Yield Trial. Agron. J. 1988, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D.C.; Da Silva, J.A.G.; Marchioro, V.S.; De Souza, V.Q.; Jost, E. Mean Performance and Stability in Multi-Environment Trials I: Combining Features of AMMI and BLUP Techniques. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2949–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annicchiarico, P. Cultivar Adaptation and Recommendation from Alfalfa Trials in Northern Italy. J. Genet. Breed. 1992, 46, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Huehn, M. Nonparametric Measures of Phenotypic Stability. Part 2: Applications. Euphytica 1990, 47, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.S.; Binns, M.R. A Superiority Measure of Cultivar Performance for Cultivar × Location Data. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1988, 68, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, P.C.S. Novas Metodologias de Análise da Adaptabilidade e Estabilidade de Comportamento; Universidade Federal de Viçosa: Viçosa, Brazil, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, H.; Gauch, H.G.; Wei, J.; Xie, J.; Chen, S.; Peng, H.; Bu, J.; Jiang, X. Genotype by Environment Interaction Analysis for Grain Yield and Yield Components of Summer Maize Hybrids across the Huanghuaihai Region in China. Agriculture 2022, 12, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimizadeh, R.; Pezeshkpour, P.; Mirzaee, A.; Barzali, M.; Sharifi, P.; Safari Motlagh, M.R. Stability Analysis for Seed Yield of Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Genotypes by Experimental and Biological Approaches. Vestn. VOGiS 2023, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Akram, Z.; Shabbir, G.; Manaf, A.; Ahmed, M. Identification of Drought Tolerant Chickpea Genotypes through Multi Trait Stability Index. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 6818–6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houasli, C.; Sahri, A.; Nsarellah, N.; Idrissi, O. Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Breeding in Morocco: Genetic Gain and Stability of Grain Yield and Seed Size under Winter Planting Conditions. Euphytica 2021, 217, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danakumara, T.; Kumar, T.; Kumar, N.; Patil, B.S.; Bharadwaj, C.; Patel, U.; Joshi, N.; Bindra, S.; Tripathi, S.; Varshney, R.K.; et al. A Multi-Model Based Stability Analysis Employing Multi-Environmental Trials (METs) Data for Discerning Heat Tolerance in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Landraces. Plants 2023, 12, 3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Vandemark, G. AMMI and GGE Biplot Analysis of Seed Protein Concentration, Yield, and 100-seed Weight for Chickpea Cultivars and Breeding Lines in the US Pacific Northwest. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadithya, A.S.; Bindra, S.; Sharma, N.; Sanwal, S.K.; Shanmugavadivel, S.P.; Singh, I.; Bharadwaj, C.; Singh, M. Multi-Model Statistical Approaches for Assessing the Stability of Cicer Interspecific Derivatives in the Trans and Upper Gangetic Regions of India. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS. SAS System, version 9.1.3; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2008.

- Scott, A.J.; Knott, M. A Cluster Analysis Method for Grouping Means in the Analysis of Variance. Biometrics 1974, 30, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D. Metan: An R Package for Multi-environment Trial Analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.D. Programa Genes-Ampliado e Integrado Aos Aplicativos R, Matlab e Selegen. Acta Scientiarum. Agron. 2016, 38, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oroian, C.; Ugruțan, F.; Mureșan, I.C.; Oroian, I.; Odagiu, A.; Petrescu-Mag, I.V.; Burduhos, P. AMMI Analysis of Genotype × Environment Interaction on Sugar Beet (Beta vulgaris L.) Yield, Sugar Content and Production in Romania. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya, J.P.; Bhartiya, P.; Bhartiya, A. Genetic Variability, Heritability and Character Association for Yield and Component Characters in Soybean (G. max (L.) Merrill). J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2011, 12, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, M.C.; Sediyama, T.; Cruz, C.D.; Nascimento, M.; Matsuo, É. Adaptability and Yield Stability of Soybean Genotypes by Mean Eberhart and Russell Methods, Artificial Neural Networks and Centroid. ASB J. 2021, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, R.; Reslow, F.; Huicho, J.; Vetukuri, R.; Crossa, J. Adaptability, Stability, and Productivity of Potato Breeding Clones and Cultivars at High Latitudes in Europe. Discov. Life 2024, 54, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, C.; Rotter, B.; Horres, R.; Udupa, S.M.; Besser, B.; Bellarmino, L.; Baum, M.; Matsumura, H.; Terauchi, R.; Kahl, G.; et al. SuperSAGE: The Drought Stress-Responsive Transcriptome of Chickpea Roots. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.; Thudi, M.; Roorkiwal, M.; He, W.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Yang, W.; Bajaj, P.; Cubry, P.; Rathore, A.; Jian, J.; et al. Resequencing of 429 Chickpea Accessions from 45 Countries Provides Insights into Genome Diversity, Domestication and Agronomic Traits. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istanbuli, T.; Alsamman, A.M.; Al-Shamaa, K.; Abu Assar, A.; Adlan, M.; Kumar, T.; Tawkaz, S.; Hamwieh, A. Selection of High Nitrogen Fixation Chickpea Genotypes under Drought Stress Conditions Using Multi-Environment Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1490080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Barati, A.; Koohkan, S.A.; Jabari, M.; Marzoghian, A.; Gholipoor, A.; Shahbazi-Homonloo, K.; Zali, H.; Poodineh, O.; Kheirgo, M. Dissection of Genotype-by-Environment Interaction and Yield Stability Analysis in Barley Using AMMI Model and Stability Statistics. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapim, C.A.; Pacheco, C.A.P.; do Amaral Júnior, A.T.; Vieira, R.A.; Pinto, R.J.B.; Conrado, T.V. Correlations between the Stability and Adaptability Statistics of Popcorn Cultivars. Euphytica 2010, 174, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmildt, E.R.; Cruz, C.D. Adaptability and Stability of Maize Using Eberhart and Russell and Annicchiarico Methods. Ceres 2005, 52, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D.C.; Da Silva, J.A.G.; Sari, B.G.; Diel, M.I. Mean Performance and Stability in Multi-Environment Trials II: Selection Based on Multiple Traits. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicaksana, N.; Maulana, H.; Yuwariah, Y.; Ismail, A.; Ruswandi, Y.A.R.; Ruswandi, D. Selection of High Yield and Stable Maize Hybrids in Mega-Environments of Java Island, Indonesia. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).