Abstract

The use of convolutional neural networks in nursery production remains limited, emphasizing the need for advanced vision-based approaches to support automation. This study evaluated the feasibility of detecting chip-budding graft sites in apple nurseries using YOLO object detection and segmentation models. A dataset of 3630 RGB images of budding sites was collected under variable field conditions. The models achieved high detection precision and consistent segmentation performance, confirming strong convergence and structural maturity across YOLO generations. The YOLO12s model demonstrated the most balanced performance, combining high precision with superior localization accuracy, particularly under higher Intersection-over-Union threshold conditions. In the segmentation experiments, both architectures achieved nearly equivalent performance, with only minor variations observed across evaluation metrics. The YOLO11s-seg model showed slightly higher Precision and overall stability, whereas YOLOv8s-seg retained a small advantage in Recall. Inference efficiency was assessed on both high-performance (RTX 5080) and embedded (Jetson Orin NX) platforms. YOLOv8s achieved the highest inference efficiency with minimal Latency, while TensorRT optimization further improved throughput and reduced Latency across all YOLO models. These results demonstrate that framework-level optimization can provide substantial practical benefits. The findings confirm the suitability of YOLO-based methods for precise detection of grafting sites in apple nurseries and establish a foundation for developing autonomous systems supporting nursery and orchard automation.

1. Introduction

The apple tree is one of the most widely cultivated fruit tree species in temperate climate zones. Asian countries, particularly China, play the most significant role in global apple production, serving as both the leading producer and consumer of apples and therefore holding a central position in the global fruit market [1,2].

In Europe, apple cultivation is concentrated both within the European Union—in countries such as Poland, Italy, and France—and beyond its borders, including Russia, Serbia, and Ukraine. The United States also remains a major producer, while countries in South America, Africa, and Oceania contribute to a lesser extent [3].

Intensification is an essential prerequisite for achieving high profitability in fruit production and involves the cultivation of a large number of trees characterized by low vegetative vigor [4,5,6]. For this reason, access to high-quality nursery material is essential to enable the dynamic development of fruit-growing plantations [7,8]. This, in turn, allows for improved tree growth and a faster onset of fruiting in newly established orchards [9]. The demand for nursery material in apple cultivation continues to increase and is characterized by considerable diversity. This phenomenon results from changing consumer preferences as well as the introduction of new cultivars and rootstocks to the market [10]. The use of modern production technologies varies significantly among countries, leading to diverse developmental trends in apple production worldwide [11]. Global fruit production is currently undergoing a period of rapid and profound transformation encompassing economic, social, ethical, and environmental dimensions. All analyzed scenarios related to the management of fruit tree cultivation share a common feature—high labor demand, which is characteristic of this type of production. Manual labor remains indispensable for the performance of many cultivation tasks, regardless of the production method employed [12].

An exception to this trend is the nursery production of fruit trees, where manual labor remains essential, leading to high labor costs, particularly during grafting, budding, and the preparation of planting material for sale. For this reason, it is necessary to undertake efforts aimed at mechanizing these stages in order to reduce dependence on human labor, the availability of which is steadily declining while its cost continues to rise. This situation contributes to decreased profitability of nursery enterprises and, at the same time, to increased prices of planting material, which in turn negatively affects the development of farms focused on fruit production.

In fruit tree nursery production, budding involves the vegetative propagation of fruit trees by grafting a single bud a selected cultivar onto a rootstock. The procedure is typically performed during the summer season. The bud, along with a small piece of bark, is inserted into an incision made on the rootstock, after which the grafting site is secured with tape or foil strip [13,14,15].

In practice, one person is typically responsible for inserting the bud, while another follows behind to secure it. The budding procedure involves numerous complex and precise operations, making it extremely challenging given the current state of artificial intelligence and robotics to develop a fully automated solution for this stage. However, unlike the budding process itself, securing the grafted bud is considerably less complex, requiring only the identification of the insertion point and its proper protection.

This concept, however, necessitates the development of two key components. The first involves designing machine vision-based solutions for accurate localization of the budding site, while the second concerns the automation of the bud-securing process using tape or film. Current solutions in this area rely entirely on manual labor and require numerous precise movements. Therefore, it is essential to develop a new method that could utilize materials suitable for heat sealing or self-adhesion.

By integrating these two processes, it would be possible to design a mobile robot capable of replacing one of the two workers performing this task, thereby significantly reducing the time required for budding through increased labor efficiency and simultaneously lowering employment costs.

Agriculture is a labor-intensive sector, and with the growing global population and increasing demand for food, the need for automation of production processes is becoming ever more critical. Artificial intelligence plays a key role in supporting farmers through the application of advanced technologies and tools. The future of global agriculture will largely depend on the effective integration of AI-based solutions [16].

A sustainable and resilient future for agriculture will depend on the pace at which the digital divide can be bridged, the ethical use of technology ensured, and the role of farmers strengthened as active participants in innovation rather than mere recipients. For intelligent agricultural technologies to become practical and effective solutions, well-planned and coordinated actions aimed at their real-world implementation are essential [17].

Agricultural robots have the potential to significantly reduce labor demand, lower production costs, and increase efficiency and yields. The evolution of agriculture from its earliest stages to the current fourth revolution has been inherently transformative, driving continuous modernization of production methods. However, smart farming technologies, including artificial intelligence, are still in the developmental phase and remain applied only to a limited extent [18].

Despite the enormous potential of artificial intelligence-based object detection systems in agriculture, there remain significant limitations to their practical application. Many advanced models require high computational power and extensive, precisely annotated datasets. Real-time inference, particularly on edge devices, faces challenges related to Latency and energy constraints. This highlights the need for further research on lightweight network architectures, domain adaptation techniques, and efficient learning methods that are robust to the variable conditions of agricultural environments [19].

The development of artificial intelligence has led to the emergence of numerous methods that enable the automatic processing and interpretation of visual data. One of the key areas of AI has become machine vision, whose goal is to enable computers to analyze and interpret images and video sequences in a manner resembling human perception.

Computer vision focuses on the analysis of images to reconstruct the properties of a depicted scene, such as shape, lighting, and color distribution [20]. Machine learning systems employ a technique known as deep learning. In deep learning, complex relationships within data are uncovered through backpropagation, which provides information on how to adjust network parameters to improve the representations between successive layers. Architectures of deep convolutional neural networks (CNN) utilizing this technique have become the foundation of modern image processing solutions [21].

The evolution of convolutional neural networks has been marked by significant advancements in architecture design, training methods, performance, and application domains, driven by the need to develop faster and more efficient solutions for image analysis [22]. Convolutional neural networks represent a specialized type of multilayer neural network designed for the analysis of grid-structured data such as images [23]. They employ convolution operations to automatically detect patterns, enabling effective object recognition, localization, and classification. CNNs have become the foundation of most modern computer vision models due to their ability to learn complex visual representations [24]. Based on the architecture of convolutional neural networks, numerous models for object detection have been developed, among which one of the most groundbreaking has been the YOLO (You Only Look Once) algorithm [25], which enabled fast and accurate target detection [26]. In contrast to earlier two-stage detectors such as R-CNN and Fast R-CNN, YOLO performs the entire object detection process within a single convolutional network, treating detection as a regression task that simultaneously predicts bounding box coordinates and class probabilities. This approach enables end-to-end optimization, making YOLO one of the most efficient real-time detection models.

The use of convolutional neural networks in nursery production remains limited, underscoring the need for further research to optimize deep-learning methods for practical applications. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of detecting chip-budding graft sites in apple nurseries using YOLO-based object detection models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

Photographic data were collected during the 2025 growing season at an apple tree nursery located in eastern Poland (51.224726° N, 22.426559° E). Apple rootstocks of the M26 variety, with diameters of 6–8 mm and 8–10 mm, were planted at intervals of 22–25 cm within rows and 85 cm between rows. One-year-old scions were collected from the Golden Delicious cultivar. The rootstocks were budded on the southern side at a height of 22–24 cm. The image dataset was acquired using a Samsung Galaxy S25 smartphone (Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Suwon-si, Republic of Korea) equipped with an RGB camera sensor (1/1.56″, 50 MP) providing a native resolution of 8160 × 6120 pixels [27]. A total of 3630 images were captured before the budding sites were covered with protective foil.

To better support the generalization capability of the object detection models, the image dataset was collected under naturally occurring variability within the nursery environment. Photographs were acquired across multiple days and at different times of day, capturing a range of illumination scenarios including direct sunlight, diffuse overcast lighting, partial shading along the trunk, and mixed-light conditions caused by cloud movement. Additional variability resulted from changes in bark surface moisture after rain or morning dew, as well as natural background differences associated with soil color. Images were taken from multiple viewing angles and maximum distances not exceeding 40 cm to reflect realistic movement during budding task. This level of diversity provides a representative approximation of real field variability, which is essential for evaluating model robustness in outdoor horticultural applications.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

All images were resized to a resolution of 640 × 480 pixels while maintaining the original 4:3 aspect ratio, using a custom Python-based utility designed for image dimension standardization. The complete set of scripts utilized for data preprocessing, training, and performance evaluation is provided in the accompanying online repository associated with this work [28].

For the task of detecting the budding site, annotation was performed using the LabelImg (1.8.6) tool [29], whereas for training models designed for segmentation, labels were assigned using the Labelme (5.10.1) tool [30]. A total of 4848 objects (budding sites) were annotated, with both the detection and segmentation datasets containing the same number of labeled objects. The dataset contained one class assigned to the site of budding.

Both datasets were divided into three subsets (training, validation, and test) in an approximate ratio of 80:10:10. The dataset was split using a Python-based program, and prior to the division, the correctness of the assigned labels was verified. The same set of images was used for each subset, ensuring full consistency between the two main datasets. A detailed division of subsets is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of images and annotated objects for each subset.

2.3. YOLO Models Training

The selection of YOLOv8s, YOLOv9s, YOLOv10s, YOLO11s, and YOLO12s models, along with their segmentation counterparts YOLOv8s-seg and YOLO11s-seg [31], was motivated by the objective of capturing the architectural evolution of the YOLO family across its latest development stages. These models represent consecutive design iterations that introduce progressive refinements in convolutional backbones, feature integration mechanisms, and training strategies, while preserving a unified philosophy centered on real-time visual perception tasks.

Incorporating the lightweight “s” variants ensured a fair comparison under similar parameter scales, enabling direct evaluation of how architectural innovations—rather than model capacity—impact detection and segmentation accuracy, inference speed, and generalization ability. YOLOv8s was adopted as the baseline model due to its maturity and wide adoption in applied computer vision workflows. Subsequent versions, from YOLOv9s through YOLO12s, together with the segmentation models YOLOv8s-seg and YOLO11s-seg, were included to assess how incremental enhancements in feature representation, attention design, and optimization contribute to improvements in detection and segmentation performance under practical conditions. This sequential comparative approach provides a coherent perspective on the evolution of the YOLO architecture family, facilitating the analysis of both performance gains and the diminishing returns that accompany increasingly complex network structures.

The experiments were conducted using two hardware platforms: a primary workstation and an Edge AI computer.

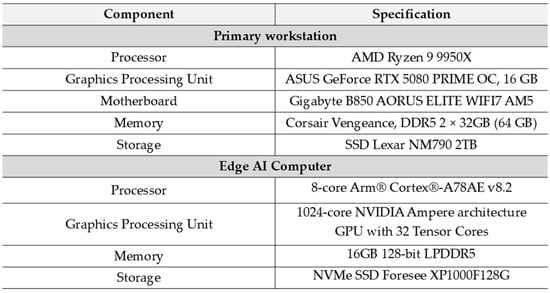

The primary workstation, equipped with an AMD Ryzen 9 9950X CPU (AMD, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an ASUS GeForce RTX 5080 PRIME OC GPU (16 GB VRAM), was employed for data preprocessing, model training, and performance benchmarking. The system was further configured with a Gigabyte B850 AORUS ELITE WIFI7 AM5 motherboard (Gigabyte, Taipei, Taiwan), 64 GB of DDR5 memory (Corsair Vengeance, 2 × 32 GB; Corsair, Milpitas, CA, USA), and a 2 TB Lexar NM790 SSD for high-speed storage. The Edge AI computer, based on the NVIDIA Jetson Orin NX platform, was utilized for inference evaluation of YOLO models. This embedded system integrates an 8-core Arm® Cortex-A78AE v8.2 processor and a 1024-core NVIDIA Ampere GPU with 32 Tensor Cores, supported by 16 GB of 128-bit LPDDR5 memory and an NVMe Foresee XP1000F128G SSD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hardware setup of Primary workstation and Edge AI Computer.

This configuration enabled efficient high-throughput training on the workstation and low-latency inference on the embedded platform, ensuring a representative evaluation of YOLO model performance across both desktop-class and edge-AI computing environments.

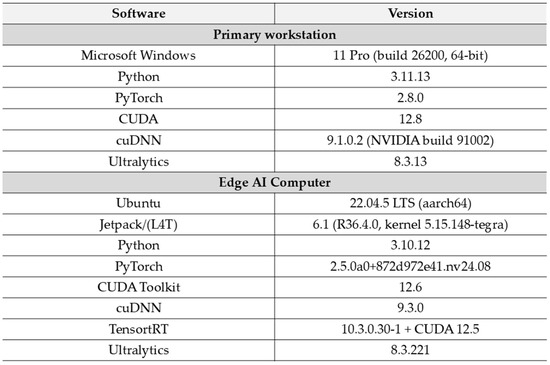

The primary workstation operated on Microsoft Windows 11 Pro (64-bit, build 26200), with a Python 3.11.13 environment and the PyTorch 2.8.0 deep-learning framework. Model training utilized CUDA 12.8 and cuDNN 9.1.0.2 (NVIDIA SDK 12.0.0.002) for GPU acceleration, together with the Ultralytics 8.3.13 library for YOLO model implementation and management. The Edge AI computer ran Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS (aarch64) with NVIDIA JetPack 6.1 (Linux for Tegra R36.4.0, kernel 5.15.148-tegra). The deployment environment included Python 3.10.12, PyTorch 2.5.0 + CUDA 12.6, and cuDNN 9.3.0. TensorRT 10.3.0.30-1 was used for optimized inference, in conjunction with Ultralytics 8.3.221 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Software setup of Primary workstation and Edge AI Computer.

This configuration ensured compatibility between the training and inference environments, while enabling optimized TensorRT acceleration for real-time YOLO performance evaluation on the Jetson Orin NX platform.

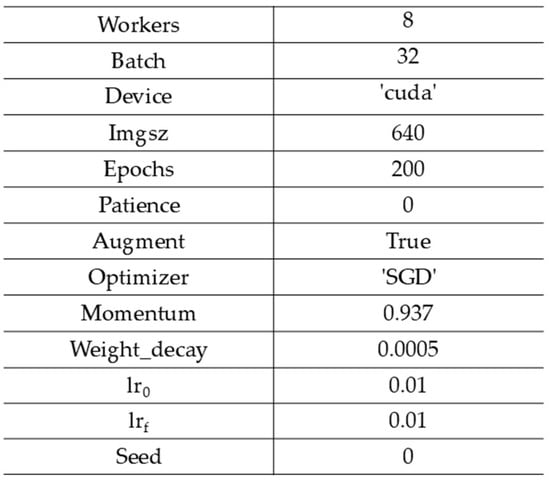

Each model was trained for 200 epochs with a batch size of 32 and an input image resolution of 640 × 640 pixels, which provides a balance between computational efficiency and detection precision. The stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer was employed, configured with a momentum coefficient of 0.937 and a weight decay of 0.0005 to ensure stable convergence and regularization. The initial learning rate was set to 0.01 (lr0), decaying linearly to 0.01 (lrf) over the course of training. A fixed random seed (0) was used to guarantee experimental reproducibility. Data augmentation was enabled (augment = True), allowing the model to generalize better to unseen data through on-the-fly geometric and photometric transformations. The training utilized 8 parallel data-loading workers to optimize throughput on the GPU and was executed entirely on the CUDA device, leveraging the RTX 5080 GPU described previously. The patience parameter was set to 0, ensuring that early stopping was disabled so that all models completed the full 200 epochs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Training hyperparameter settings.

These hyperparameter choices follow the established Ultralytics YOLO optimization guidelines, balancing convergence speed and generalization for object detection tasks while maintaining reproducibility across experimental runs.

Models evaluation was assessed using widely adopted object detection metrics, including Precision, Recall, mean Average Precision at an Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5 (mAP50), mean Average Precision averaged over IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 (mAP50:95), and the F1-score. Metric computation was automated through custom Python-based scripts built upon the official YOLO evaluation framework, ensuring reproducible and consistent results across all models and datasets.

Precision and Recall quantify detection accuracy and completeness, respectively, as defined in Equations (1) and (2), where TP, FP, and FN denote the counts of true positives, false positives, and false negatives. The mean Average Precision (mAP) represents the area under the Precision–Recall curve, summarizing the trade-off between detection confidence and accuracy across threshold variations. The mAP50 metric corresponds to a fixed IoU threshold of 0.5, whereas mAP50:95 denotes the average of mAP values computed over IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 with 0.05 increments, as expressed in Equations (3) and (4). The F1-score (Equation (5)) defines the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, serving as a unified indicator of detection reliability. Together, these measures provide a comprehensive assessment of model performance, capturing localization accuracy, confidence calibration, and robustness across diverse imaging conditions.

Inference performance was evaluated in a controlled benchmarking environment using dummy inputs to isolate computational efficiency from dataset variability. This setup enabled consistent measurement of frame rate and Latency across architectures, independent of model accuracy or dataset characteristics.

Model inference was evaluated on two distinct computing platforms: a high-performance desktop workstation featuring an NVIDIA RTX 5080 GPU (ASUSTek Computer Inc., Taipei, Taiwan), and an embedded system built on the Jetson Orin NX 16 GB module (Seeed Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Both setups followed an identical benchmarking protocol implemented in the Ultralytics YOLO framework, utilizing FP16 precision under CUDA-based inference. All evaluations were performed using the best-performing model checkpoint (best.pt).

For the RTX 5080 environment, inference experiments were executed in PyTorch (CUDA) with input tensors of size (1 × 3 × 640 × 640). Each model underwent three consecutive benchmark sessions, each including 50 warm-up and 200 timed iterations. To ensure robust statistics, every model was measured over five independent trials. Between sessions, a 90-s pause was applied to stabilize GPU thermal conditions and clock frequencies. Throughput and Latency metrics were then averaged after trimming values outside the 10th–90th percentile range to suppress transient variations and produce stable FPS and Latency estimates.

On the Jetson Orin NX platform, the same benchmarking procedure was applied with a shorter iteration scheme—20 warm-up and 60 timed iterations—and an additional 10-s pre-run stabilization delay to ensure GPU readiness. Models were processed in groups of three, separated by a 150-s cooldown interval to avoid thermal throttling. Two inference backends were evaluated under identical conditions: PyTorch (using best.pt) and TensorRT (using best.engine). Each setup was executed in five independent runs, with results post-processed by excluding measurements beyond the 20th–80th percentile range to enhance statistical reliability and measurement stability.

Beyond detection accuracy, the computational efficiency of the models was also examined, an essential factor for deployment on hardware-limited systems. Following the evaluation philosophy established in contemporary YOLO frameworks, three complementary indicators were employed to quantify the trade-off between accuracy and real-time performance. All benchmarking scripts were implemented as custom Python utilities specifically developed for this study.

The Frames Per Second (FPS) metric defines the rate of image processing during model inference. It is calculated as the ratio of the total number of forward passes to the overall inference time . A higher FPS value indicates faster model execution and greater suitability for real-time applications (Equation (6)).

Latency represents the average time required to process a single input image, measured in milliseconds. Conceptually, it is the inverse of the FPS metric and directly reflects the responsiveness of the inference process. Maintaining low Latency is essential for edge and onboard computing scenarios, where rapid decision-making depends on minimal processing delay (Equation (7)).

The Accuracy–Speed Ratio serves as an integrated performance indicator that balances detection precision and computational throughput. It quantifies the detection accuracy (mAP50:95) achieved per unit of inference speed (FPS). Higher values of this ratio indicate a more favorable trade-off between predictive quality and runtime efficiency, providing a concise measure of overall model optimization (Equation (8)).

All performance metrics, including FPS, Latency, and the Accuracy–Speed Ratio, were computed as mean ± standard deviation based on five independent inference repetitions for each model. This methodology captures both the average computational behavior and its variability across repeated trials, enabling a statistically consistent evaluation of model efficiency.

3. Results

For the detection task, all models exhibited uniformly high and stable performance across all evaluation metrics. The YOLO12s model achieved the most balanced overall results, combining leading precision with the strongest localization accuracy, particularly under stricter overlap thresholds. Close behind, the YOLO11s variant demonstrated comparable robustness and marginally greater stability. Earlier generations such as YOLOv8s and YOLOv10s preserved strong predictive accuracy, though with slightly reduced balance between Precision and Recall. Among the tested configurations, YOLOv9s showed the weakest metric uniformity.

In the segmentation task, both architectures delivered nearly identical outcomes, differing only marginally across metrics. The YOLO11s-seg model produced slightly higher precision and overall consistency, whereas YOLOv8s-seg maintained a modest advantage in Recall. The close alignment of their performance reflects a well-calibrated equilibrium between localization accuracy and mask completeness, confirming the robustness of both segmentation pipelines for feature extraction.

When comparing detection and segmentation, overall differences remained minimal. Detection maintained a slight advantage under stricter localization criteria, reflecting the relative simplicity of bounding-box alignment compared to pixel-level mask delineation. Conversely, segmentation exhibited slightly stronger Recall oriented behavior, highlighting its improved capacity to capture the full extent of graft regions. Collectively, both approaches demonstrated high reliability, stability, and generalization, highlighting the strong architectural refinement present in contemporary YOLO models for high precision nursery vision tasks (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of chip-budding graft sites detection and segmentation.

Figure 4 presents examples of grafting-site detection produced by the trained YOLO12s model. Blue bounding boxes indicate the detected budding sites, and the numerical values correspond to the model’s confidence scores. Figure 5 includes examples of chip-budding graft site segmentation generated by the trained YOLO11s-seg model. The overlaid segmentation mask highlights the grafting region. All images were processed at an input resolution of 640 × 480 pixels and padded to 640 × 640 during inference to match the models input requirements.

Figure 4.

Chip-budding graft sites detection example by the trained YOLO12s model.

Figure 5.

Chip-budding graft sites segmentation example by the trained YOLO11s-seg model.

Table 3 summarizes the performance outcomes of the evaluated models obtained on the RTX 5080 GPU using the PyTorch framework.

Table 3.

YOLO models’ performance on RTX 5080 (PyTorch).

The YOLOv8s model achieved the highest frame rate and the lowest Latency and Accuracy–speed ratio, demonstrating its superior computational efficiency on the RTX 5080 platform. In contrast, the most recent YOLO12s model recorded the lowest throughput, accompanied by the highest Latency and accuracy–speed ratio values. The results revealed a clear trend of decreasing frame rate and increasing Latency and accuracy–speed ratio across successive generations. An exception to this hierarchy was observed in the YOLOv9s model, which deviated markedly from the general trend, exhibiting a pronounced drop in frame rate together with higher Latency and a less favorable accuracy–speed ratio.

For segmentation, a similar hierarchy was maintained. The older YOLOv8s-seg variant delivered a higher frame rate and lower Latency as well as a lower accuracy–speed ratio compared to the newer YOLO11s-seg model, confirming a consistent trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency across both detection and segmentation tasks.

Table 4 summarizes the performance metrics of the evaluated models executed on the Jetson Orin NX platform using the PyTorch framework. Under the PyTorch framework, all models demonstrated stable but noticeably lower throughput compared to desktop GPU execution, reflecting the limited computational resources of embedded hardware. Within detection, the smallest YOLOv8s achieved the highest frame rate and the lowest Latency, maintaining the most favorable efficiency ratio. Successive generations exhibited a gradual reduction in processing speed, with the most recent YOLO12s operating considerably slower and showing increased Latency. Similar to the results obtained on the RTX 5080, the YOLOv9s model deviated from this pattern, displaying a pronounced drop in frame rate and a concurrent increase in Latency and accuracy–speed ratio, resulting in the weakest overall performance among the PyTorch-based models.

Table 4.

YOLO models performance on Jetson Orin NX (PyTorch).

For segmentation, the YOLOv8s-seg variant retained a clear advantage in speed and Latency, whereas the newer YOLO11s-seg model exhibited a lower accuracy–speed ratio. TensorRT optimization further improved frame rates and reduced Latency across both segmentation networks. However, unlike in the PyTorch setting, the YOLO11s-seg model achieved a slightly more favorable accuracy–speed ratio, demonstrating that TensorRT optimizations can differentially benefit models depending on their architectural balance between feature extraction and mask generation.

For segmentation, the YOLOv8s-seg variant retained a clear advantage in speed and Latency, whereas the newer YOLO11s-seg model exhibited a lower accuracy–speed ratio.

Table 5 shows the performance of YOLO models on Jetson Orin NX (TensoRT) and comparison with the PyTorch framework.

Table 5.

YOLO models’ performance on Jetson Orin NX (TensoRT) and comparison to the PyTorch framework.

When executed under TensorRT, all models exhibited a clear improvement in inference speed accompanied by a corresponding reduction in Latency. As a result, the performance hierarchy observed under PyTorch remained consistent, but each model shifted toward substantially higher throughput and lower Latency values. Notably, the YOLOv9s model, which had performed significantly worse under PyTorch, achieved a higher frame rate and lower Latency as well as a lower accuracy–speed ratio than YOLO12s once optimized with TensorRT, highlighting the particularly strong impact of optimization for this configuration. Overall, in the detection task, YOLOv8s remained the fastest and most efficient architecture.

TensorRT optimization further improved frame rates and reduced Latency across both segmentation networks. However, unlike in the PyTorch setting, the YOLO11s-seg model achieved a slightly more favorable accuracy–speed ratio, demonstrating that TensorRT optimizations can differentially benefit models depending on their architectural balance between feature extraction and mask generation.

4. Discussion

Chip-budding detection presents several visual challenges that complicate automated analysis. The appearance of the grafting site varies substantially due to changing lighting conditions in the field, including strong direct sunlight, diffuse overcast illumination, and shadow gradients along the trunk. Additionally, the natural heterogeneity of bark texture, such as surface irregularities, lenticels, color variations, and age-related roughness, can obscure the boundaries of the grafting cut. Field-acquired images are also affected by environmental factors, including moisture on the bark, soil reflections, and background clutter such as weeds or nursery infrastructure. These sources of variability increase the difficulty of consistent feature extraction and highlight the need for robust detection and segmentation models.

The results reveal a strong convergence in detection and segmentation performance across all evaluated YOLO architectures. The narrow gaps between models indicate that the series has reached a stage of structural maturity, where design refinements contribute primarily to stability and consistency rather than substantial accuracy gains. The newest variants, particularly YOLO12s and YOLO11s, exhibited slightly improved Precision and localization coherence, confirming the effect of progressive optimization in feature representation.

In segmentation, both architectures yielded comparable results, showing that recent mask-based implementations are well-optimized for fine structural analysis. The marginal Precision–Recall differences suggest that the balance between boundary accuracy and region completeness has been effectively optimized.

The minimal divergence between detection and segmentation tasks further underlines the robustness of the YOLO framework. Detection retained a minor advantage under strict localization criteria, while segmentation demonstrated greater spatial completeness. Together, these findings confirm the reliability of YOLO-based approaches for precise and real-time nursery inspection, emphasizing that future improvements will likely emerge from optimization and adaptation rather than architectural redesign.

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents one of the first attempts to apply convolutional neural networks, specifically the YOLO algorithm, to the detection of budding sites in apple nursery. Therefore, a direct comparison of our results with other studies is not feasible, as no previous research has addressed this specific task. For this reason, we discuss our findings in relation to studies focusing on bud detection and cutting sites in shoots of various fruit trees and shrubs, which share similar visual and methodological characteristics.

Previous research demonstrated that YOLOv8-based vision systems can effectively detect apple buds in unstructured orchard environments, enabling reliable real-time identification [32]. Importantly, studies on apple bud thinning have shown that YOLOv4, YOLOv5, and YOLOv7 can all be effectively applied to flower-bud detection across both stereo-image and mobile-image datasets, demonstrating strong generalization and real-time applicability under orchard conditions [33]. Other investigations highlighted the effectiveness of deep-learning–based RGB-D methods for identifying pruning points in apple trees, demonstrating reliable detection of branch intersections and potential cutting sites suitable for robotic pruning applications [34]. Further related work in apple production has applied depth-augmented CNN frameworks to detect branches in formally trained fruiting-wall orchards, showing that combining pseudo-color and depth inputs improves the reliability of branch localization under natural conditions. These results indicate that integrating complementary sensing modalities can support the development of automation-oriented systems such as shake-and-catch harvesting platforms [35]. Studies on kiwi cultivation demonstrated that YOLO-based models can accurately identify buds under orchard conditions, with YOLOv4 showing strong real-time detection capability applicable [36]. Research on kiwi bud thinning introduced YOLOv8-based detection frameworks capable of distinguishing primary and lateral buds, demonstrating that tailored training and image-partitioning strategies can enhance recognition Precision and support the automation of bud-thinning operations [37]. Investigations into grapevine pruning demonstrated that YOLO-based models can reliably detect cane nodes across varied vineyard environments, with YOLOv7 providing the most stable performance for real-time identification applicable to autonomous pruning systems [38]. These related studies collectively underscore the growing potential of YOLO-based architectures as a robust foundation for developing automated vision systems in precision agriculture, including tasks such as detection of buds and cutting sites.

The evaluation of performance confirmed a consistent computational hierarchy across YOLO generations. YOLOv8s maintained the highest inference efficiency, combining minimal Latency with the best accuracy–speed balance, while successive versions progressively traded speed for architectural complexity. YOLOv9s notably diverged from this pattern, exhibiting disproportionate performance degradation relative to its size. Segmentation models followed the same order, with YOLOv8s-seg outperforming newer variant in runtime efficiency and Latency stability. TensorRT deployment uniformly improved throughput and reduced Latency, preserving the relative hierarchy observed under PyTorch. Optimization effects were model-dependent—particularly beneficial for YOLOv9s, which recovered stable efficiency after conversion—confirming that framework-level tuning can outweigh architectural refinements in practical inference scenarios. But also in the case of models for segmentation tasks, optimization by TensorRT allowed the YOLO11s-seg models to obtain higher FPS and lower Latency than YOLOv8-seg.

Our findings are consistent with previous reports indicating that TensorRT substantially improves inference efficiency without compromising detection accuracy [39]. Also findings are consistent with technical documentation from Ultralytics, which reports that TensorRT optimization can yield up to a five-fold increase in GPU inference speed compared to the native PyTorch runtime while maintaining model accuracy [40,41].

Although the results demonstrate strong performance and robustness of the evaluated YOLO architectures, several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. The experiments focused exclusively on a single budding technique (chip budding), using scions from the ‘Golden Delicious’ cultivar grafted onto M26 rootstocks. As a result, the models were not evaluated across different cultivar–rootstock combinations or alternative propagation methods that may exhibit different morphological features or visual signatures. The data were collected within one nursery environment, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Variability associated with soil type, background structure, and weed pressure was not systematically examined, even though such factors can influence the visual complexity of grafting sites under practical field conditions. The imaging process relied solely on an RGB camera. Other sensing modalities that could potentially improve robustness such as RGB cameras with higher or lower resolution, stereoscopic cameras, or multispectral imaging were not incorporated into the dataset. Polarizing filters were also not used. These technologies may enhance visual discrimination under challenging lighting, occlusions, or cluttered backgrounds. Inference benchmarking was performed on two hardware platforms: a high-performance desktop GPU (RTX 5080) and an embedded Jetson Orin NX module. While these devices represent two distinct computational categories, additional edge-AI accelerators commonly used in agricultural robotics were not evaluated, and their inference characteristics may differ from those reported in this study. In addition, several application-specific risks should be acknowledged for future robot deployment. Although the images in this study were captured before taping and therefore do not include tape-induced occlusion, real nursery conditions may introduce occasional visual ambiguities caused by bud scars, minor bark injuries, or partial shading of the grafting zone. Similarly, camera-viewing angle and operator movement may influence the visible geometry of the budding site, potentially affecting detection confidence in fully autonomous systems. While such conditions were not present in the curated dataset used here, they represent practical challenges that future datasets and integrated robotic workflows may need to account for. These factors delineate the scope of the present work and highlight directions for future research, including broader multi-environment data collection, evaluation across multiple propagation systems, integration of diverse imaging modalities, and benchmarking on a wider range of embedded computer platforms.

Beyond the limitations outlined above, practical deployment in a nursery setting introduces additional challenges that must be considered. Sensor-related issues such as motion blur, image degradation, general camera noise, or temporary lens contamination caused by dust or moisture may also affect segmentation quality during real operation. Moreover, deploying the system on embedded hardware such as Jetson-class edge devices requires careful optimization, as throughput and latency are constrained compared with workstation-grade GPUs. These deployment-related challenges highlight the importance of robust preprocessing pipelines, hardware-aware model selection, and adaptive inference strategies when transitioning from controlled experimental conditions to real nursery applications.

5. Conclusions

The full automation of chip budding remains out of reach for current robotic systems, as the sequence of cutting the bark, preparing the scion, and inserting it into the grafting site requires a chain of high precision manipulations that even trained workers must master through experience. In contrast, the subsequent step of securing the graft with tape or foil is mechanically far simpler and therefore represents a realistic entry point for early-stage automation. However, this step can only be automated if the system is able to reliably and precisely localize the grafting point under real nursery conditions. For this reason, robust detection and segmentation of the budding site constitute the essential perceptual prerequisite for any future robotic solution.

This study demonstrated the feasibility of applying YOLO-based architectures for precise detection of budding sites in apple nurseries, marking one of the first deep-learning approaches dedicated to this task. The results revealed a strong convergence in detection and segmentation performance across recent YOLO generations, indicating architectural maturity where improvements primarily enhance stability and consistency rather than raw accuracy. YOLOv8s maintained the highest inference efficiency, while newer variants such as YOLO11s and YOLO12s achieved marginal gains in Precision through refined feature representation. TensorRT optimization further elevated inference speed and reduced Latency, confirming that framework-level optimization can yield substantial performance benefits. Collectively, these findings position YOLO-based methods as a reliable foundation for future real-time vision systems in precision agriculture, where continued progress will likely arise from adaptive optimization and domain-specific integration rather than new network topologies.

The integration of optimized object-detection and segmentation architectures with lightweight edge devices and robotic platforms represents a promising direction for advancing nursery automation. Future developments may focus on robotic systems capable of using real-time localization of chip-budding graft sites to support targeted operations in apple nurseries. Such integration can bridge the gap between high-performing vision algorithms and autonomous field-ready systems, accelerating the adoption of precision horticulture technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., K.B. and D.I.W.; methodology, M.K., K.B. and D.I.W.; software, K.B.; validation, M.K., K.B. and D.I.W.; formal analysis, K.B. and D.I.W.; investigation, K.B.; resources, M.K., D.I.W. and K.B.; data curation, K.B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K.; visualization, M.K.; supervision, M.K. and K.B.; project administration, K.B.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All preprocessing, training, and evaluation scripts used in this study are available in the associated repository: [https://github.com/kamilczynski/Detection-of-Chip-Budding-Graft-Sites-in-Apple-Nursery-Using-YOLO-Models (accessed on 10 November 2025)]. The original datasets and trained YOLO model weights (best.pt and best.engine) are not publicly available due to their large volume and storage constraints but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Damian I. Wójcik was employed by the company Gospodarstwo Szkółkarsko-Sadownicze Wójcik. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Jin, S.; Li, W.; Cao, Y.; Jones, G.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Chang, Q.; Yang, G.; Frewer, L.J. Identifying Barriers to Sustainable Apple Production: A Stakeholder Perspective. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yu, J.; Tan, D.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Z. Life Cycle Assessment of Apple Production and Consumption under Different Sales Models in China. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/qcl (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Wieczorek, R.; Zydlik, Z.; Zydlik, P. Biofumigation Treatment Using Tagetes Patula, Sinapis Alba and Raphanus Sativus Changes the Biological Properties of Replanted Soil in a Fruit Tree Nursery. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szot, I.; Lipa, T. Apple trees yielding and fruit quality depending on the crop load, branch type and position in the crown. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2019, 18, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapłan, M.; Jurkowski, G.; Krawiec, M.; Borowy, A.; Wójcik, I.; Palonka, S. Wpływ Zabiegów Stymulujących Rozgałęzianie Na Jakość Okulantów Jabłoni. Ann. Hortic. 2018, 27, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapłan, M.; Klimek, K.E.; Buczyński, K. Analysis of the Impact of Treatments Stimulating Branching on the Quality of Maiden Apple Trees. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapłan, M.; Klimek, K.; Borkowska, A.; Buczyński, K. Effect of Growth Regulators on the Quality of Apple Tree Whorls. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, K.L.; Raja, W.H.; Nabi, S.U. Quality of Nursery Trees Is Critical for Optimal Growth and Inducing Precocity in Apple. Appl. Fruit Sci. 2024, 66, 2135–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydlik, Z.; Zydlik, P.; Jarosz, Z.; Wieczorek, R. The Use of Organic Additives for Replanted Soil in Apple Tree Production in a Fruit Tree Nursery. Agriculture 2023, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muder, A.; Garming, H.; Dreisiebner-Lanz, S.; Kerngast, K.; Rosner, F.; Kličková, K.; Kurthy, G.; Cimer, K.; Bertazzoli, A.; Altamura, V.; et al. Apple Production and Apple Value Chains in Europe. Eur. J. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 87, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baima, L.; Nari, L.; Nari, D.; Bossolasco, A.; Blanc, S.; Brun, F. Sustainability Analysis of Apple Orchards: Integrating Environmental and Economic Perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mika, A. Szczepienie i Inne Metody Rozmnażania Roślin Sadowniczych; Powszechne Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Leśne SP. z o.o.: Warszawa, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lipecki, J.; Jacyna, T.; Lipa, T.; Szot, I. The Quality of Apple Nursery Trees of Knip-Boom Type as Affected by the Methods of Propagation. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2013, 12, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lipecki, J.; Szot, I.; Lipa, T. The Effect of Cultivar on the Growth and Relations between Growth Characters in “Knip-Boom” Apple Trees. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2014, 13, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, G.; Kumar Pal, S. Applications of AI in Precision Agriculture. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, M.; Prahadeeswaran, M. Revolutionizing Agriculture: A Review of Smart Farming Technologies for a Sustainable Future. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, S.; Murugaiyan, V.; Ilakkiya, S.; Kumar, V.; Sundaram, R.M.; Kumar, R.M. Opportunities, Challenges, and Interventions for Agriculture 4.0 Adoption. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Shen, Y.; Liu, H. ObjectDetection in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Methods, Applications, Challenges, and Future Directions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliski, R. Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications; Texts in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-34371-2. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navarrete, O.L.; Correa-Guimaraes, A.; Navas-Gracia, L.M. Application of Convolutional Neural Networks in Weed Detection and Identification: A Systematic Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugrul, B.; Elfatimi, E.; Eryigit, R. Convolutional Neural Networks in Detection of Plant Leaf Diseases: A Review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wang, Z.; Kuen, J.; Ma, L.; Shahroudy, A.; Shuai, B.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Cai, J.; et al. Recent Advances in Convolutional Neural Networks. Pattern Recognit. 2018, 77, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Song, C.; Xu, T.; Jiang, R. Precision Weeding in Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Intelligent Laser Robots Leveraging Deep Learning Techniques. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsung. Galaxy S25. Available online: https://www.samsung.com/pl/smartphones/galaxy-s25/specs/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Kamilczynski. GitHub Repository 2025. Available online: https://github.com/kamilczynski/Detection-of-Chip-Budding-Graft-Sites-in-Apple-Nursery-Using-YOLO-Models (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Tzutalin. LabelImg: Image Annotation Tool. Version 1.8.6, GitHub Repository. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/Tzutalin/labelImg (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Wkentaro. Labelme: Image Annotation Tool. Version 5.9.1, GitHub Repository. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/Wkentaro/Labelme (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ultralytics. Models. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/models/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pawikhum, K.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Heinemann, P. Development of a Machine Vision System for Apple Bud Thinning in Precision Crop Load Management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.; He, L. Real-Time Bud Detection Using Yolov4 for Automatic Apple Flower Bud Thinning. In Proceedings of the 2023 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Omaha, NE, USA, 9–12 July 2023; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Kang, F. An Image-Based System for Locating Pruning Points in Apple Trees Using Instance Segmentation and RGB-D Images. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 236, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, L.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Branch Detection for Apple Trees Trained in Fruiting Wall Architecture Using Depth Features and Regions-Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Suo, R.; Zhao, G.; Gao, C.; Fu, L.; Shi, F.; Dhupia, J.; Li, R.; Cui, Y. Real-Time Detection of Kiwifruit Flower and Bud Simultaneously in Orchard Using YOLOv4 for Robotic Pollination. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 193, 106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; He, L.; Shi, Y.; Janneh, L.L.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.; Li, R.; Ye, H.; Chen, J.; Majeed, Y.; et al. Growth Characteristics Based Multi-Class Kiwifruit Bud Detection with Overlap-Partitioning Algorithm for Robotic Thinning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 229, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.; Da Silva, D.Q.; Filipe, V.; Pinho, T.M.; Cunha, M.; Cunha, J.B.; Dos Santos, F.N. Enhancing Grapevine Node Detection to Support Pruning Automation: Leveraging State-of-the-Art YOLO Detection Models for 2D Image Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, K. Exploring TensorRT to Improve Real-Time Inference for Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 24th Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 8th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 20th Int Conf on Smart City; 8th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Hainan, China, 18–20 December 2022; IEEE: Hainan, China, 2022; pp. 2011–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ultralytics. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/integrations/tensorrt/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Ultralytics. Available online: https://docs.ultralytics.com/modes/benchmark/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).