Abstract

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has long been applied to industrial systems but is increasingly recognized for its role in evaluating the environmental sustainability of agricultural systems. However, agricultural systems differ significantly from industrial systems in important ways that, if not properly accounted for, would lead to misleading estimates, necessitating modifications in many cases to the traditional LCA framework. This study reviewed several key differences of agricultural systems, including land use constraints, spatial heterogeneity, and multifaceted co-products. Through a systematic literature search conducted in Web of Science (2005–2024), we identified relevant studies on indirect land use change (iLUC), spatial variability, and biogeochemical modeling in agriculture. Our findings reveal that incorporating iLUC into LCA can lead to significant changes in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions estimates, with variations ranging from 19% to over 1000%, depending on the models and assumptions used. We also developed a decision framework for determining when spatial disaggregation is necessary versus when national or regional averages would suffice and discussed the implications of this for LCA conclusions. Our review highlights the importance of accounting for agricultural system variability, particularly with respect to integrating biogeochemical models and temporal dynamics, which have been largely overlooked in traditional LCA models. Furthermore, we address the challenges of allocating environmental impacts in multifunctional agricultural systems, offering recommendations for more transparent and context-specific approaches. These insights provide LCA practitioners with actionable guidance for improving the accuracy and relevance of agricultural sustainability assessments.

1. Introduction

Agriculture serves as the cornerstone of society, providing a vital and reliable source of nutrition for human survival. The human-agriculture-environment system forms an interconnected framework, where the growing demand for agricultural productshas led to increasing environmental pressures, including greenhouse gas emissions, land use changes, biodiversity loss, and issues of water quantity and quality [1]. For instance, the global food system is responsible for 25–30% of anthropogenic GHG emissions [2,3,4], while agricultural expansion remains a primary driver of biodiversity loss [5,6,7]. Further impacts arise from agricultural input use, such as fertilizers and pesticides altering soil properties and damaging aquatic ecosystems [8,9,10,11,12,13], and irrigation contributing to water scarcity [14,15]. Projected growth in global population and food demand [16,17] intensifies these challenges, threatening to exacerbate environmental impacts through further land use change [5] while climate change simultaneously undermines agricultural resilience [18,19,20].

In this context, robust tools are needed to assess and mitigate the environmental impacts of agriculture [21]. Life cycle assessment (LCA) has emerged as a primary method for this purpose, providing a comprehensive framework to quantify impacts from resource extraction to end-of-life [22,23,24,25,26]. It does so by determining greener product, energy, technology, material alternatives [27,28,29,30], and by identifying hotspots in product systems [31] and potential tradeoffs involved in product substitution [32]. Applications in agroecosystems are wide-ranging: from evaluating dietary shifts and food waste valorization [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] to assessing the sustainability of bioenergy systems [40,41,42,43,44,45,46], to analyzing the impacts of agricultural land expansion on carbon storage and biodiversity [47,48] and examining the trade-offs associated with new technologies and climate adaptation strategies [49,50].

However, a critical methodological gap exists. Despite the growing number of agro-LCA studies, the vast majority of them have applied the traditional models (e.g., process and Input–Output (IO)-based) [51]. These are retrospective, linear frameworks that use average data and assume fixed supply chains [52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. While valuable for descriptive purposes, such models have limited predictive capability and often fail to account for the complex, nonlinear, and spatially variable nature of agricultural systems [52,59,60,61]. This interpretation is consistent with how economists have viewed IO models [62,63,64,65]. Consequently, they may fall short in providing robust decision support for policy or management, which requires understanding the consequences of changes within dynamic market and biophysical contexts [52,53,60,66,67,68].

This limitation is particularly acute because agricultural systems differ importantly from the industrial systems for which conventional LCA was developed. Key differences include high spatial and temporal variability, nonlinear input–output relationships (e.g., diminishing returns to fertilizer), coupled crop-livestock interactions, and the production of multiple co-products and ecosystem services. These features mean that the environmental impact of an additional unit of output depends critically on where and how it is produced, and what market or ecological adjustments it triggers. Therefore, this review synthesizes recent advances across agriculture LCA, systems modeling, agronomy, and economics to address these core methodological challenges. We focus explicitly on how agricultural systems respond to changes in demand, and what this implies for accurately assessing their life cycle environmental impacts. Specifically, we examine critical issues such as spatial variability and commodity flows, marginal versus average data, the integration of biogeochemical models, and the challenges of allocation and multi-functionality.

To this end, this review synthesizes recent advances across agricultural LCA, systems modeling, agronomy, and economics. Specifically, we examine the critical methodological challenges arising from the fundamental differences between agricultural and industrial systems. Through a systematic review, we (1) analyze how incorporating indirect land use change (iLUC) and spatial variability (e.g., via commodity flows) can drastically alter impact assessments; (2) develop a decision framework for determining when spatial disaggregation is necessary; (3) evaluate the integration of biogeochemical models and temporal dynamics to better capture field-level processes; and (4) address allocation and multi-functionality challenges inherent to agricultural production. By integrating these often-siloed discussions, our aim is twofold: to advance LCA methodology for agricultural systems, and to provide a coherent framework that helps researchers and practitioners navigate the trade-offs between model complexity, uncertainty, and practical applicability in this critical domain.

2. Materials and Methods

To ensure a comprehensive and reproducible review, a rigorous and systematic approach was employed in selecting the literature that forms the basis of this study. The literature search strategy was designed to capture relevant publications while maintaining a balance between systematic rigor and the flexibility required to include seminal works that may not have been fully covered through standard search strategies. This two-tiered search approach combined a structured framework systematic search with targeted supplementary searches, ensuring that key literature was captured in a manner that is both transparent and comprehensive.

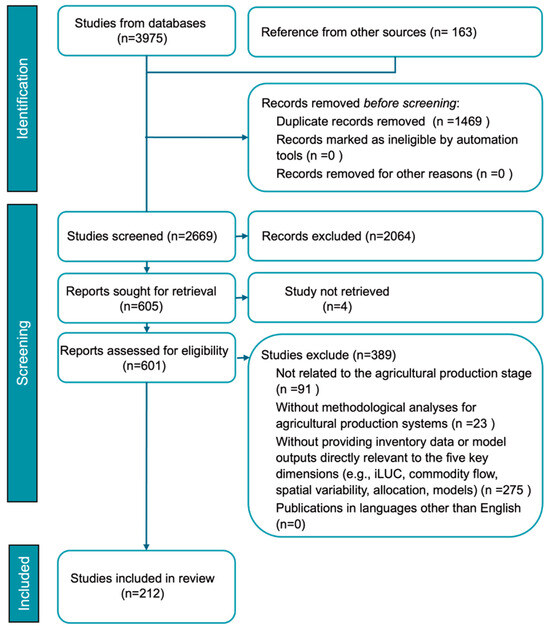

We conducted a systematic literature search in Web of Science (Core Collection) for articles published between 2005 and 2024. Search queries combined terms for life cycle assessment (e.g., “life cycle assessment” OR “LCA”) with keywords related to land use change, spatial analysis, marginality, and biogeochemical models (e.g., “indirect land use”, “iLUC”, “spatial”, “marginal”, “EPIC”, “DNDC”, “DAYCENT”, “APSIM”, “allocation”). We ran separate topic queries focused on (1) iLUC, (2) spatial/commodity flow, (3) variable input/marginal analyses, and (4) biogeochemical modeling, and aggregated results. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied rigorously to ensure the relevance and quality of the studies included in the review, only: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and technical reports that present LCA results or LCA-relevant methodological analyses for agricultural systems; (2) studies that explicitly report greenhouse gas (GHG) results or provide sufficient inventory data to compute GHGs; (3) studies addressing at least one of the target dimensions (iLUC, spatial disaggregation, marginal/attributional issues, allocation/multi-functionality, or biogeochemical modeling) were considered. Studies were excluded if they: (1) were not related to agricultural production (e.g., focusing solely on food processing); (2) were opinion pieces without methodological details or primary data; (3) were non-LCA studies that did not provide inventory data or model outputs relevant to LCA; (4) were duplicates or written in a language other than English. For transparency, we recorded numbers of records identified, screened, full text assessed, and included (Figure 1). If a formal quality appraisal was not possible (e.g., heterogeneous study designs), we applied a simple, consistent judgment protocol. These search terms were carefully constructed to ensure precision and inclusivity, targeting key concepts and methodologies discussed throughout the LCA and agricultural systems literature.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature selection process.

While the systematic search captured a wide range of studies, it became apparent that certain seminal methodological papers and highly specific case studies might not be fully represented by the search strings alone. To address this, we complemented the database search with a targeted supplementary search. This involved citation chasing, both backward and forward snowballing, to identify critical works that may not have appeared through the initial search. Additionally, foundational studies, recognized for their methodological significance or their illustrative case studies, were manually included based on the authors’ knowledge of the field. This step was essential to ensure that the review reflected the breadth of literature, including those studies that established key conceptual frameworks or provided illustrative examples central to the LCA methodology applied to agricultural systems.

The article selection process followed a clear and systematic flow, illustrated in Figure 1. The initial search resulted in a total of 3975 records from the WoS database and 163 from citation chasing. After removing duplicates, 2669 unique records underwent a preliminary title and abstract screening. Following this, 601 full-text articles were reviewed for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After including and excluding articles following the including and excluding rule, 212 articles were included in our analysis. These articles formed the foundation of the review, providing a robust and diverse dataset that supports the conclusions drawn throughout the manuscript.

3. Land Constraints and the Pressure on Land Expansion

Agricultural production requires substantially more land than does industrial production. Agricultural systems occupy over one-third of the world’s land area, far exceeding the approximately 1% used by industrial systems. Globally, crop cultivation and grazing are the largest land users, accounting for about 40% of total land area, 30% of forest land, and 30% of other land types (including deserts, glaciers, barren lands, and built-up areas) [69]. In the United States, approximately 659 million acres (29%) of land are used for rangeland and pastures, 390 million acres (17%) for farmland, while less than 28 million acres (1%) are allocated to industrial development [70]. In China, agriculture and animal husbandry together account for approximately 42.6% of total land use, while industrial use occupies only 1.3% [71]. In Germany, agriculture utilizes 52% of the country’s land surface, whereas all industrial uses occupy just 0.74% [72]. Historically, agriculture has been the main driver of land clearing. Over the past 300 years, ~700 to 1100 million ha of forest around the world were lost, primarily to timber extraction and agricultural expansion [73]. In central North America, only 1% of the tall grass remains in native vegetation, with most converted to intensive agriculture of various forms [74]. The total area of stable crops globally continued to expand between 1965 and 2011, with the rate accelerated in the last decade of the period [75].

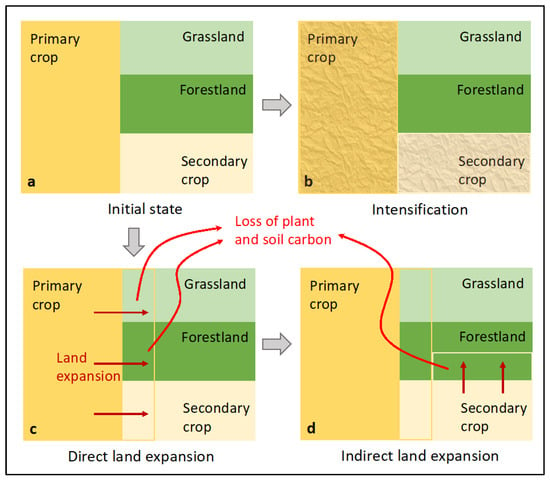

Given the large land requirement and the lack of fertile cropland, an increased demand for any agricultural commodity can potentially lead to land expansion, or extensification (Figure 2). This can occur directly and indirectly. Cropland can expand directly into natural habitats such as grassland or forestland or into semi-natural habitats such as lands set-aside for conservation or recovery purposes (Figure 2c) [76]. The rising demand for agricultural products has driven the expansion of new farmland in Africa, with 49% replacing natural vegetation and forest cover [6]. Or it may expand into other crops first, but this reduces their supply and drives up their prices, which can also lead to new land brought into production (Figure 2d). Empirical studies indicate that for every 1 billion gallons of biofuels produced in the United States, cropland area expands by 0.38 to 0.66 million acres, with the most rapid expansion occurring on lands that are less suitable for agriculture [77,78]. In either case, large amounts of carbon stored in plants and soil can be released to the atmosphere during the process of land conversion and crop cultivation thereafter [79].

Figure 2.

Conceptual illustration of agricultural responses to increased demand, constrained by arable land availability. Subfigure (a) depicts an initial state of land use. Increased demand for agricultural output can be met through (b) intensification (yield increase on existing primary cropland), (c) direct land expansion (conversion of natural habitats like grassland or forest), or (d) indirect land expansion (displacement of a secondary crop, which in turn may drive expansion elsewhere). Colors/patterns denote different land use types. Arrows indicate the pathways of change triggered by demand growth.

In addition to land expansion driven by food demand, other factors contributing to land expansion are also being increasingly acknowledged. The pressure of biofuels development on land expansion has been an area of intense research. Global biofuels production has increased rapidly over the past two decades, from 2023 to 2028, biofuel demand is projected to increase by 38 billion liters, a nearly 30% rise compared to the previous five years. By 2028, the total demand for biofuels is expected to grow by 23%, reaching 200 billion liters [80]. The United States and Brazil are the leading producers of corn and sugarcane ethanol. The rapid growth of food-based biofuels has been a major driver of global land expansion. In the United States, soybean planting area expanded from 30.6 million hectares in 2008 to 33.8 million hectares in 2016. In 2018, land area change due to biodiesel production ranged from 0.78 to 1.5 million acres per billion gallons [81,82]. In Brazil, five states, including São Paulo, are the largest producers of sugarcane ethanol, accounting for 92% of the country’s total production between 2020 and 2021. The total sugarcane crop area reached 7.731 million hectares [83,84]. Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer, has seen its production increase annually, with the cultivation area reaching 11.91 million hectares by 2016 [85].

In the context of agricultural systems, the demand for land expansion driven by both the food and biofuel sectors is expected to result in significant environmental impacts, as discussed earlier. LCA is typically based on historical data spanning a short period of time, usually from 1 to 3 years [58]. This “snapshot” approach falls short of capturing the dynamics of agricultural systems, which is part of the reason that early LCAs of food-based biofuel [86,87,88] failed to account for the land use impacts of biofuel expansion [76,79]. Moreover, LCA is conventionally a supply chain-based model, focusing on the vertical linkages between product systems through use of intermediate inputs [80]. There are inherent limitations with this vertical linkage [58]. It may capture direct land expansion (Figure 2c) if it happened to occur during the time period for which data were collected as land is a direct input. But it cannot capture indirect land expansion (Figure 2d), which occurs through the horizontal linkages between product systems (e.g., via competition for land) [67,89]. For instance, converting land previously used for food or feed production to oil palm cultivation for biofuel and other product production can lead to indirect land expansion [90]. Additionally, the European Commission has highlighted that palm oil poses a high risk of indirect land use change and has proposed legislation to limit and eventually ban the use of palm oil in biofuels within the EU by 2030 [91]. We collected key discussions on biofuels, particularly ethanol, and compared the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of agricultural products before and after incorporating indirect land use change (iLUC). The aim was to highlight the significant GHG emissions resulting from demand growth. The results revealed substantial variability, ranging from 19% to 1002%, as systematically summarized in Table 1. This variability is primarily due to differences in the models used and the methods for quantifying iLUC-related emissions. A more detailed discussion of these discrepancies will be provided in Section 3. Nevertheless, the findings clearly demonstrate that the GHG emissions associated with indirect land use change are considerable, accounting for approximately 16% of total emissions even in the most conservative scenarios within our sample.

Table 1.

The LCA results for key agricultural commodities with and without iLUC considerations.

In summary, to better account for land use impacts of agricultural systems, LCA must take a prospective approach and improve its predicative capability, as is increasingly recognized [60]. This, first, entails a fundamental change to the basis of LCA accounting, namely, the functional unit. It must shift from its conventional definition (e.g., per MJ of biofuel produced), which is static and vague (neglecting to specify whether that MJ was produced in the past or is an additional MJ to be produced in the future?), to something that is change-oriented and unambiguous (e.g., an increase in biofuel production by a certain amount from the current level) [103]. In addition, LCA must also expand beyond its conventional focus on product supply chain to include other important market mechanisms, such as indirect land use change and rebound effect. This can be achieved by integrating economic models, such as partial and general equilibrium analyses, into the conventional LCA framework, as is increasingly done [104,105,106,107].

4. Intensification and Variable Input Structures

To what extent cropland would expand, as a result of higher demand for agricultural commodities, depends partly on yield increase on existing cropland. If demand can be met by increased yield through technological intensification (e.g., greater nitrogen application; Figure 2b), the need for cultivation of new land may be reduced [108]. This brings us to another important difference between industrial and agricultural systems. In other words, by integrating additional factors within the agricultural system, the environmental impacts of land expansion can be mitigated. These factors, such as the environmental consequences of nitrogen fertilizer use, involve variability and uncertainty.

The input structure, or production recipe, in industrial systems is relatively fixed. Consider an example of a personal vehicle. Suppose a new model is well received by the market and demand is projected to grow. The input materials used to make the additional cars will be the same as those used to make the ones already sold. This is partly because this car requires a fixed set of materials (metal, plastics, rubber, leather, etc.) that are un-substitutable for one another [109]. In addition, the production line that makes this car, being a fixed asset, will not change, at least until a new line is installed. As a result, the life cycle environmental impacts of an additional car—including both the direct impacts that occur onsite and the indirect ones that are embodied in input materials—would be similar to those of an existing car.

In contrast, the input structure in agricultural production is far more variable. The agricultural system is a complex, nonlinear system with multiple inputs and is also a coupled system influenced by natural, societal, and economic factors. Crop yield is affected by various factors, including fertilizer application, irrigation water usage, temperature, and pests [20,110,111,112,113]. As a result of the changes and interactions among these input factors, crop yield can experience significant variations. First, there are diminishing returns of yield to nitrogen fertilization [114,115,116]. The last bushel (~25 kg) of corn, for example, can require 6 to 8 times more nitrogen fertilizer than the average bushel [117]. In salt-tolerant red algae aquaculture, a nitrogen to phosphorus ratio of 15:1 results in a 45% increase in growth rate and higher yields compared to a 25:1 ratio [118]. More nitrogen applied also means that more nitrogen will be lost to the environment in various forms [119]. Ruan et al. [120], for example, found an exponential increase in N2O emissions in switchgrass production as fertilization rate increases. This is mainly due to the fact that residual nitrogen is the primary driver of nitrification and denitrification, thereby leading to soil N2O emissions [121]. On the other hand, agricultural inputs, especially between fertilization and irrigation, can complement and compensate for each other [122,123,124]. A farm field with low water input and nitrogen deficiency will have low yields, which can be improved by greater irrigation, or greater nitrogen, or both at lower rates than applied alone [43]. In either case, the life cycle environmental impacts of the additional production could differ considerably from those of the average.

The variable relationships between input use and outputs, including yield and emissions, in agricultural production poses a challenge to the conventional practice of LCA. As reflected in agricultural LCA databases, such as LCA commons and Agri-footprint [73,74], inventory data span a short period of time and reflect a static agriculture system with fixed input–output relationships. Such a snapshot type of data might suffice for industrial systems but falls short for agricultural systems to assess the environmental impacts of the additional output, be it from extensification (Figure 2c,d) or intensification (Figure 2b). To better estimate the responses of input use, which determines upstream emissions, to output (or price) change in agricultural systems requires more field experiments [75,123,125] or longer-term observational data with rigorous statistic modeling [126,127,128].

Another option is to use biogeochemical models (e.g., EPIC, DNDC, DAYCENT, and APSIM), which simulate the carbon and nitrogen dynamics of agroecosystems and are widely used to inform farm-level land management decisions [129]. They have been used, for example, to determine the effects of fertilization and irrigation on yields [130,131], of different tillage practices on soil carbon dynamics [132], and of crop rotation diversification on soil nitrogen retention and N2O emission [133]. At the same time, in the context of escalating climate impacts, it is also widely applied in land use and crop management practices. For example, models are used to assess the impact of land use and land cover changes on soil erosion [134], or to implement climate-smart agricultural management [135]. They have also been incorporated in LCA studies, primarily in the area of bioenergy and biofuel [44,136,137]. Another important issue is addressing the various problems brought about by climate change, particularly balancing the relationship between yield demands, economy, and the environment in the context of climate change. This can be achieved, for example, through exploring climate-adaptive planting strategies using LCA coupled with biogeochemical models [138], or optimizing nitrogen fertilizer and residue management to ensure yield while being as environmentally friendly as possible [139]. Given the substantial resource requirements of field and farm experiments, biogeochemical models are increasingly being used in large-scale analyses to inform policy making [129]. There appears to be a greater potential for the use of these models in agricultural LCA.

However, the application of these models is subject to important limitations that must be considered. Firstly, their predictions carry inherent uncertainties; for instance, even well-calibrated models can exhibit significant errors, as seen in DNDC model validations where simulated values for key variables like nitrous oxide emissions or crop yield may still deviate substantially from observations despite careful parameterization [140,141,142]. These uncertainties often stem from incomplete representation of complex soil microbial processes and climate–soil–plant interactions, and can propagate through LCA results [143,144]. Secondly, the reliable application of these models is contingent upon substantial and high-quality input data regarding soil properties, detailed management practices, and local weather conditions, which are often scarce or costly to obtain, particularly in data-poor regions [145,146,147]. Consequently, and thirdly, the performance of a biogeochemical model is highly context-dependent. A model validated for one cropping system or geographic region cannot be reliably extrapolated to others without local calibration and validation, a step that is crucial yet often overlooked [144,147,148]. Therefore, while powerful, these tools require transparent reporting of their uncertainty, data requirements, and contextual appropriateness to ensure robust and interpretable LCA outcomes.

The inherent variability in agricultural inputs necessitates a critical evaluation of when this variability materially influences the conclusions of an LCA. The choice between using average or marginal data is not merely a technicality but is fundamentally dictated by the decision-context of the study. This alignment between goal and methodology is well-established in LCA theory. According to standard definitions, Attributional LCA (ALCA) describes the environmentally relevant physical flows to and from a life cycle, while Consequential LCA (CLCA) aims to describe how these flows change in response to possible decisions. Consequently, ALCA, often applied in retrospective assessments, typically relies on average data to attribute a share of the global environmental impacts to a product system. In contrast, CLCA, designed for prospective assessments, requires marginal data to model the consequences of decisions, capturing market-mediated and indirect effects [54,149].

Agricultural LCAs must therefore select inventory data that are consistent with the study’s goal and decision context. In practice, we recommend the following rule-of-thumb:

- 1.

- Product labeling, benchmarking, and routine supply chain characterization. For these purposes, we recommend using ALCA with representative average data. This approach provides reproducible and comparable metrics for the typical environmental impact of products. It is important to clarify that the use of average data in ALCA does not necessarily imply that the sum of all product LCAs must equal the total environmental impact of the world (the so-called “100% rule”), a point of ongoing methodological discussion [149]. While this approach offers consistency, it is critical to recognize that it does not capture the market-wide consequences of large-scale changes in demand;

- 2.

- Policy appraisal, program evaluation, and assessments of interventions likely to change production or land use. When the analyzed intervention can plausibly alter production volumes, commodity prices, or trade flows (and thus induce indirect effects like iLUC), CLCA using marginal data is essential. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that CLCA results can be highly uncertain due to the need to model complex market mechanisms and future scenarios [150]. Furthermore, a prevalent issue in uncertainty analysis for LCA is the use of independent probability distributions, which can lead to significant mass imbalances and unrealistic product compositions, thus undermining the reliability of the results [151]. Therefore, when applying CLCA, the scope and assumptions of any supporting economic or biophysical models must be thoroughly documented;

- 3.

- Comparative product or substitution decisions at the firm level. If the comparison concerns small operational changes with negligible market impacts, average data with transparent sensitivity analyses may suffice; for larger substitution scenarios with plausible market impacts, consequential approaches are recommended. The choice between ALCA and CLCA is not always a strict dichotomy, and there are studies that creatively combine elements of both approaches to suit the decision context [150].

Practical guidance, fallbacks, and addressing uncertainty. If full marginal modeling is infeasible, authors should: (1) clearly state the chosen approach and justify it by the decision context [152]; (2) run targeted global sensitivity analysis (GSA) and scenario analyses that approximate plausible marginal outcomes and help identify key sources of uncertainty [153]; and (3) place detailed sensitivity outputs in supplementary materials to preserve transparency. It is noted that uncertainty appraisal is not yet a common practice in all LCA studies, and there is a significant scope for improving the treatment of both stochastic and epistemic uncertainties [152]. Therefore, the choice between attributional and consequential treatments must be accompanied by an explicit discussion of associated uncertainties and limitations.

5. Spatial Variability and Interregional Commodity Flows

Another major difference between agricultural and industrial systems is system variability [154]. Industrial production processes are highly standardized, reflected partly in the relatively fixed input structure as discussed above such that marginal inputs are basically the same as the average, and partly in that the input structure does not vary much across space. For example, a car company with multiple manufacturing facilities in different locations uses essentially the same recipe to produce the same model of car. In contrast, agricultural production is subject to the influence of local environmental factors, from temperature, precipitation, soil properties, topography, to water availability. A field with more abundant rainfall will require less irrigation water, and with more fertile soil will require less fertilizer use. In addition, management practices could vary, depending on the knowledge of farmers [155,156]. Some farmers fertilize their cropland with manure while others prefer to use chemical fertilizers entirely [157]. The two methods have very different environmental implications in terms of reactive nitrogen emissions [158], as well as the degree of pollution to soil and water [159,160]. As the environmental factors and management practices differ from farm to farm, the production recipe, as well as associated environmental emissions, for an agricultural commodity could vary greatly across space.

The spatial variability of agricultural system has been increasingly recognized in LCA literature [161]. This is partly reflected in some of the agricultural LCA databases being at the state scale instead of the national [162]. Furthermore, Chiu and Wu [163] estimated that the county-level blue water footprint of ethanol from wheat straw and biodiesel from soybean in the US was 139 and 313 L of water per liter biofuel, with a standard deviation of 297 and 894 L, respectively. Pelton [164] found that the cradle-to-gate GHG emissions of US corn ranged from 0.2 to 0.7 kg CO2e per kg produced from county to county (for the middle 80 percentile). Yang et al. [165] identified that the ecological toxicity and human health impacts of US corn production could vary 10-fold across states. In a recent survey in China, Zhang et al. [166] found that although nitrogen application rate in corn production generally exceeded 200 kg ha−1, it could vary from 0 to 600 kg ha−1. The carbon footprint of cotton production in China varies significantly across regions, with the northwest reaching as high as 6220.13 kg CO2e ha−1, while the Yangtze River Basin has a much lower value of 2958.56 kg CO2e ha−1 [167]. The main driving factor behind this difference is the regional variation in nitrogen fertilizer application. A study in India shows that, compared to small farms, large farms have a 39% lower carbon footprint per ton of rice [168]. In Sweden, Henryson [169] derived site-dependent impact factors and revealed that the marine eutrophication impact of spring barley and grass ley cultivation could vary 20-fold across the studied sites. Using a global dataset covering ~40,000 farms and 1600 processors, Poore and Nemecek [170] found that impact of an agricultural commodity could vary 50-fold, suggesting a great potential for mitigation. This is also the reason why an increasing number of scholars are calling for and beginning to conduct territorial LCA studies [171,172,173,174].

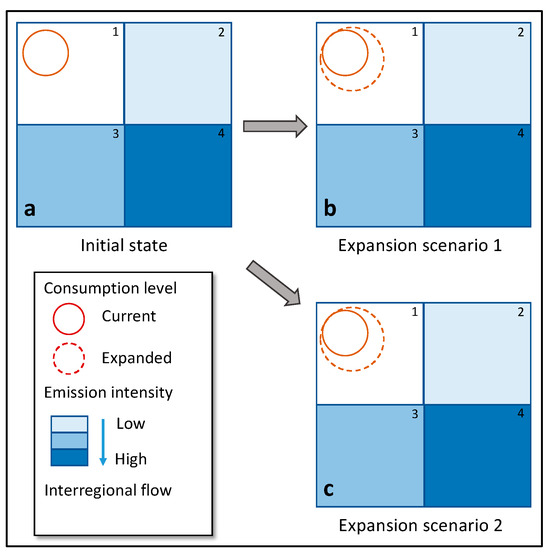

The high spatial variability of agricultural systems makes it difficult to determine the total environmental impacts of changes in production (Figure 3). If the additional production takes place in high-impact regions, the total environmental impacts will be higher than if it takes place in low-impact regions. The key is to understand how agricultural commodities flow between regions, or interregional commodity flows, to meet various demands (e.g., livestock, food processing companies, and bioenergy) [175]. This knowledge is instrumental in determining where downstream industries will likely source or stop sourcing their next unit of agricultural commodity from. And this, given the spatial variation, will further determine the total environmental impacts of the additional production (Figure 3). For example, a study by Yang on interregional commodity flows in the United States found that approximately 50% of agricultural products, manufacturing goods, and mineral products are transported across state lines. The transportation of corn between states accounted for 10% to 50% of the total flow. The study showed that if inter-state corn flows were ignored in state-level estimations, the carbon footprint could be overestimated by 30% to 50% in certain states, and the relative error in irrigation water use could range from 200% to 400% in some cases [176].

Figure 3.

An illustration of the importance of understanding interregional commodity flows in estimating the life cycle environmental impacts of agricultural commodities given regional variability. (a) Region 1 purchases food produced in regions 2–4, each with a different life cycle impact. (b,c) Increasing food consumption in region 1 can be met by purchasing more food primarily from low-impact regions (2 and 3; scenario 1) or from high-impact regions (4; scenario 2). The life cycle impact of the additional food consumption will be higher in scenario 2 than in scenario 1.

Data on interregional commodity flows within a country, however, are not readily available, and thus need to be estimated. This is mainly because commodities flow freely within a country, as opposed to being tracked between countries as imports and exports. In the US, the best public data source is Commodity Flow Survey [177], which collects shipment data from a large sample of businesses in different locations over several reporting weeks. The CFS data are, however, grouped into ~30 broad categories, a level of aggregation that is difficult to be used by LCA. This is also true even for the input–output (IO)-based LCA models, which are at the sector level but, in general, differentiate between 100 and 500 sectors.

Interregional commodities flows, on the other hand, can be reasonably estimated, as they are governed by certain factors such as infrastructure, transportation cost, and geographic locations. A large body of research has developed in the regional science literature, and many methods have been proposed for estimation of interregional commodity flows [178,179,180,181]. There has been a growing effort to better understand how foods flow within a country [134,175,178]. Smith et al. [175], for example, used a cost minimization transport model to determine inter-county corn flows in the US. Zheng et al. [182,183] employed a new method based on entropy theory to construct a provincial single region IO (SRIO) tables for China, and developed a multi-regional input–output (MRIO) model for 2012, 2015, and 2017, covering 42 industries, including the agricultural sector, across 31 provinces and regions in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan). Ye et al. [184] combined the physical agricultural food system with China’s monetary supply chain to develop a symmetric interprovincial multi-regional input–output (MRIO) model. They performed supply/use/input–output analysis for 84 agricultural products and 75 processes and applied it to blue water footprint accounting for each province. Lin et al. [185] downscaled the Commodity Flow Survey based on an array of techniques including machine learning and linear programming, and estimated food flows between ~3000 counties in the US. Building on this, Deniz et al. [186] made three improvements by using a food flow optimization model to analyze the food flows (in kilograms) between all counties for all food commodity groups in the United States from 2007 to 2017. Additionally, Venkatramanan et al. [187] employed a data-driven network approach to model tomato flows in Nepal. Ridley et al. [188] developed a statistical downscaling approach that uses interstate trade data, county-level supply and demand characteristics for grain products, and geographical factors to model the bilateral transport of grains between pairs of counties. Interregional estimates from these studies have been used to identify improvement opportunities and vulnerabilities across food supply chains and to study pest spread.

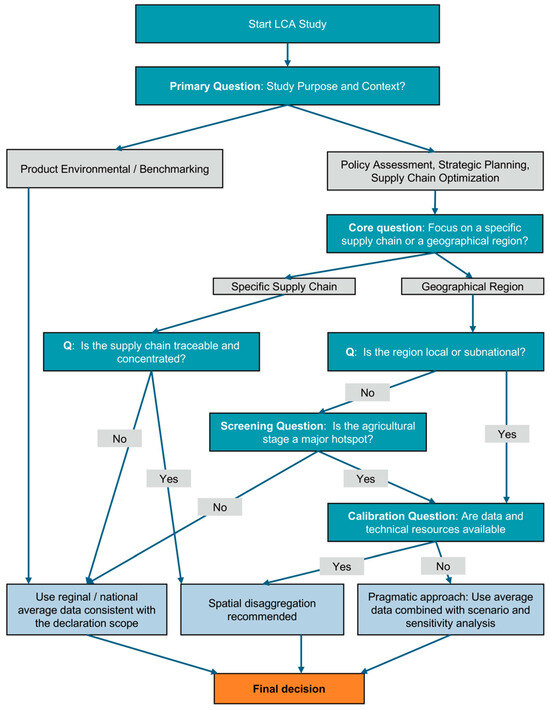

The compelling evidence of spatial variability presented above raises a critical pragmatic question: when is it necessary to undertake the often resource-intensive process of spatial disaggregation? The answer is not universal but depends on the specific goal and scope of the LCA study. To provide clear and actionable guidance, we propose a sequential decision framework structured around four key factors (Figure 4): (1) the goal and purpose of the study, (2) the geographic scope and spatial extent of the supply chain, (3) the relative contribution of agricultural production, and (4) the availability of data and resources.

Figure 4.

A decision framework for determining the necessity of spatial disaggregation in agricultural LCA.

This framework is implemented through the following stepwise considerations:

- Goal and Purpose of the Study: The primary driver is the intended application of the results.

- Attributional LCAs for Product Labeling or Benchmarking: For studies aimed at providing a representative, comparable average footprint of a product (e.g., for an environmental product declaration), the use of regional or national average data is often not only sufficient but preferred for ensuring consistency and fairness.

- Consequential LCAs for Policy or Strategic Decision-Making: When the goal is to assess the impact of a new policy, a large-scale expansion of production, or to identify opportunities for supply chain optimization, spatial disaggregation becomes critical [189,190]. It is essential for understanding geographically specific trade-offs, avoiding burden shifting from one region to another, and pinpointing high-leverage intervention points.

- Geographic Scope and Supply Chain Extent: The scale of the analysis dictates the requisite resolution of the data.

- Local/Regional Studies: Assessments focused on a specific watershed, state, or province almost always require spatially explicit data within that region, as averages from a larger area (e.g., national) may mask critical local variability [191].

- National/Global Studies with Diffuse Supply Chains: For commodities sourced from a wide, non-specific geographic area (e.g., a national average food basket), highly aggregated data may be a pragmatic necessity. However, if the supply chain is traceable to specific production regions, a nested approach using regional data for key contributors is highly recommended [192].

- Relative Contribution of Agricultural Production: The importance of spatial detail is proportional to the significance of the agricultural stage.

- If a preliminary screening-level LCA reveals that the agricultural production phase is a minor contributor to the total life cycle impact, refining its spatial resolution is unlikely to change the overall conclusion.

- Conversely, if agriculture is a dominant hotspot (e.g., contributing >50% to the global warming potential or eutrophication potential), then spatial disaggregation is warranted to ensure the accuracy and actionable nature of the results [193,194].

- Availability of Data and Resources: Practical constraints must be acknowledged.

- The decision to pursue spatial disaggregation is also a function of data availability, model capability, and allocated time and budget. When full spatial modeling is infeasible, targeted sensitivity analysis using high and low-impact scenarios can provide valuable insights into the potential influence of spatial variability [195].

By applying this framework, practitioners can make a transparent and justified choice regarding spatial data, thereby enhancing the credibility and relevance of their agricultural LCA studies.

6. Methodological Challenges and Outlook

As agricultural life cycle assessment (LCA) continues to evolve to support broader sustainability agendas and increasingly policy-relevant questions, the complexity of models used in such studies has grown in parallel. Contemporary applications frequently involve the integration of biogeochemical simulators, multi-regional input–output models, and economic equilibrium frameworks [136,137,138]. While such coupling allows for more dynamic representations of land use, emissions, and commodity flows, it also introduces a cascade of uncertainties that propagate across layers—often without being explicitly tracked or quantified. This concern is substantiated by a systematic review of LCA studies [196], which found that less than 20% of published works conduct any form of uncertainty analysis, and among those, the vast majority focus solely on parameter uncertainty while largely neglecting model and scenario uncertainties. This is particularly problematic for consequential LCAs that integrate economic models, where the uncertainties stemming from identifying marginal technologies and market-mediated substitutions are acknowledged to be substantial yet are rarely quantified due to a lack of standardized methods. For instance, the choice of allocation method in attributional LCA alone can alter results by 10–26%, illustrating the significant impact of structural modeling choices [196]. Therefore, the pursuit of model complexity must be critically weighed against the opacity of the compounded uncertainty it generates. In contexts where baseline data are limited or highly variable, as is frequently the case in agricultural settings, this compounded uncertainty can blur the interpretability of results and compromise the robustness of conclusions. In such cases, simpler models with transparent assumptions and tractable structures may prove not only sufficient but preferable, particularly when used for communication, benchmarking, or preliminary decision support.

Another persistent challenge lies in addressing the multifunctionality of agricultural systems. Unlike industrial systems with clearly defined single outputs, agricultural production frequently yields multiple co-products (e.g., wool and meat, milk and beef), and it also delivers ecosystem services that extend beyond the food system, such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity, and cultural value [197,198]. Selecting an appropriate allocation method—whether mass-based, economic, or system expansion—is seldom a neutral choice, as it can significantly influence calculated impacts [199,200]. The complexity increases when outputs are functionally interdependent or temporally decoupled. While system expansion is often recommended for consequential assessments, its implementation can be data-intensive and methodologically opaque, as illustrated by the challenges in livestock supply chains where manure must be co-accounted for alongside meat or milk [201]. More recently, biophysical or function-driven allocation approaches—e.g., assigning upstream burdens based on metabolic energy requirements of body-tissue growth—have been proposed as alternatives, though their practical application remains limited and sensitive to assumptions about co-product causality [202,203]. As such, methodological pluralism, supported by sensitivity analysis and clear justification, remains essential.

Temporal dynamics represent another under-addressed dimension in many agricultural LCA studies. While land use change is often considered, other temporal aspects—such as crop rotations, seasonality, and long-term soil carbon dynamics—are frequently averaged out or excluded [204]. This simplification risks underestimating both the variability and inertia of agricultural systems, especially in studies involving long-term carbon sequestration, nutrient cycles, or climate adaptation strategies. Dynamic LCA frameworks have been proposed to better represent such changes [205,206], but their adoption has been limited by data and modeling constraints. Nonetheless, the inclusion of temporal variation remains critical for accurately capturing the environmental performance of agricultural systems across both short-term production cycles and long-term ecological transitions.

Finally, many of the above challenges are further amplified in data-scarce contexts, particularly in developing countries where agricultural production is highly significant but standardized environmental data remain scarce [207]. In such cases, practitioners often rely on proxy datasets or adapt foreign emission factors—introducing additional uncertainty and potential bias [208]. While such compromises may be unavoidable, they should be accompanied by rigorous uncertainty analysis and transparent reporting. At the same time, strategic investment in localized data collection—focusing on high-impact processes such as fertilizer use, irrigation, and land conversion—can greatly enhance model reliability [209]. Emerging tools such as remote sensing, citizen science, and digital farm registries offer new opportunities to fill these gaps and should be integrated into LCA capacity-building efforts in these regions [210,211].

7. Conclusions

This review synthesizes the methodological advances and persistent challenges in applying life cycle assessment (LCA) to agricultural systems. A central theme that emerges is the fundamental mismatch between the static, linear, and retrospective framework of conventional LCA and the dynamic, nonlinear, and spatially heterogeneous nature of agroecosystems. We identify three critical areas in which agricultural systems diverge from industrial systems, requiring tailored methodological approaches.

First, agricultural production is inherently land-intensive. Increased demand for agricultural commodities often triggers direct or indirect land use change (iLUC), resulting in substantial greenhouse gas emissions from carbon stock losses—impacts that are frequently overlooked in static LCAs. As demonstrated, the inclusion of iLUC can alter the carbon footprint of biofuels by 19% to over 1000%, highlighting the necessity of prospective, consequential modeling that incorporates economic equilibrium analyses to capture these market-mediated effects.

Second, agricultural systems exhibit highly variable input–output relationships, where key inputs like water and nutrients are interdependent, and their marginal productivity often deviates from the average due to factors such as diminishing returns. Conventional LCA databases, based on static average data, fail to capture the environmental impacts of intensified output. Integrating biogeochemical models (e.g., DNDC, APSIM) and using marginal data in Consequential LCA (CLCA) are crucial for more accurate assessments, but these models introduce inherent uncertainties, require scarce local data, and are context-dependent, necessitating careful calibration and transparent reporting. The choice between average data in Attributional LCA (ALCA) and marginal data in CLCA should be based on the study’s decision context—whether for retrospective accounting (e.g., product labeling) or prospective assessments (e.g., policy changes). Practitioners must justify their methodological choices, conduct uncertainty and sensitivity analyses, and communicate associated limitations to ensure robust and interpretable results.

Third, spatial variability in environmental conditions and management practices leads to substantial differences in the impacts of producing the same commodity across various locations. Therefore, the environmental impact of increased production depends crucially on the location of additional production, which is determined by interregional commodity flows. Advances in multi-regional input–output modeling, transport optimization, and data-driven network analyses now enable the estimation of these flows, allowing for more spatially explicit impact assessments. The decision framework presented in this review provides practical guidance on when such resource-intensive spatial disaggregation is warranted, based on study goals, supply chain scope, and the relative significance of agricultural hotspots.

Looking ahead, advancing agricultural LCA requires a concerted effort to bridge disciplinary silos. The integration of economic models, biogeochemical simulators, and spatially explicit flow analyses into LCA frameworks holds great promise for improving predictive accuracy and decision relevance. However, the increased complexity of these models must be carefully balanced against the compounded uncertainties they introduce, necessitating more rigorous and transparent uncertainty and sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, persistent challenges related to the multifunctionality of agricultural systems and the incorporation of temporal dynamics—such as crop rotations and long-term soil carbon changes—demand continued methodological development and context-specific approaches.

Finally, the successful translation of these methodological advances into robust assessments hinges on the development of supportive infrastructure. There is an urgent need for the creation and curation of LCA databases that incorporate spatially differentiated, marginal, and temporally explicit data for agricultural processes. Harmonizing standards for modeling iLUC, spatial allocation, and multifunctionality in agricultural LCA will enhance comparability and credibility. For policymakers, these methodological refinements are not merely academic; they are essential for crafting effective regulations, incentives, and sustainability certifications that reflect the true systemic consequences of agricultural policies, biofuel mandates, and dietary shifts, thereby steering agrifood systems toward genuine environmental sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and J.X.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and Y.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gallardo, R.K. The environmental impacts of agriculture: A review. Int. Rev. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2024, 18, 165–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, A.; Kaur, G.; Jaeger, J.A.G. A geospatial framework for the assessment and monitoring of environmental impacts of agriculture. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.R.; Skeg, J.; Buendia, E.C.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Zhai, P.; Slade, R.; Connors, S.; Van Diemen, S.; et al. Climate Change and Land: An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Ahammad, H.; Clark, H.; Dong, H.; Elsiddig, E.A.; Haberl, H.; Harper, R.; House, J.; Jafari, M.; et al. Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 811–922. [Google Scholar]

- Forslund, A.; Tibi, A.; Schmitt, B.; Marajo-Petitzon, E.; Debaeke, P.; Durand, J.L.; Faverdin, P.; Guyomard, H. Can healthy diets be achieved worldwide in 2050 without farmland expansion? Glob. Food Secur. 2023, 39, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, P.; Turubanova, S.; Hansen, M.C.; Tyukavina, A.; Zalles, V.; Khan, A.; Song, X.P.; Pickens, A.; Shen, Q.; Cortez, J. Global maps of cropland extent and change show accelerated cropland expansion in the twenty-first century. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; Sayer, J.; Cassman, K.G. Agricultural expansion and its impacts on tropical nature. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbell, F.; Reich, P.B.; Tilman, D.; Hobbie, S.E.; Polasky, S.; Binder, S. Nutrient enrichment, biodiversity loss, and consequent declines in ecosystem productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 11911–11916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Banerjee, S.; Ma, Q.; Liao, G.; Hu, B.; Zhao, H.; Li, T. Organic fertilization drives shifts in microbiome complexity and keystone taxa increase the resistance of microbial mediated functions to biodiversity loss. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2023, 59, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütte, G.; Eckerstorfer, M.; Rastelli, V.; Reichenbecher, W.; Restrepo-Vassalli, S.; Ruohonen-Lehto, M.; Saucy, A.G.W.; Mertens, M. Herbicide resistance and biodiversity: Agronomic and environmental aspects of genetically modified herbicide-resistant plants. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2017, 29, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, H.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Wright, J.S.; Hall, J.W.; Gong, P.; Ni, S.; Qiao, S.; Huang, G.; et al. Managing nitrogen to restore water quality in China. Nature 2019, 567, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, D.; Levitan, L. Pesticides: Amounts applied and amounts reaching pests. BioScience 1986, 36, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.P. Pesticides, environment, and food safety. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermid, S.; Nocco, M.; Lawston-Parker, P.; Keune, J.; Pokhrel, Y.; Jain, M.; Jägermeyr, J.; Brocca, L.; Massari, C.; Jones, A.D.; et al. Irrigation in the Earth system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Hejazi, M.; Tang, Q.; Vernon, C.R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Calvin, K. Global agricultural green and blue water consumption under future climate and land use changes. J. Hydrol. 2019, 574, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2022_wpp_key-messages.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- van Dijk, M.; Morley, T.; Rau, M.L.; Saghai, Y. A meta-analysis of projected global food demand and population at risk of hunger for the period 2010–2050. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.G.; Burney, J.; D’Odorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; et al. Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science 2024, 385, eadn3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, P.; Chen, W.Q.; Smith, T.M. Toward sustainable climate change adaptation. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, B.; Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lobell, D.B.; Huang, Y.; Huang, M.; Yao, Y.; Bassu, S.; Ciais, P.; et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9326–9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The future of food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management-Life Cycle Assessment-Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Brentrup, F.; Küsters, J.; Kuhlmann, H.; Lammel, J. Environmental impact assessment of agricultural production systems using the life cycle assessment methodology: I. Theoretical concept of a LCA method tailored to crop production. Eur. J. Agron. 2004, 20, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bae, J.; Kim, J.; Suh, S. Replacing gasoline with corn ethanol results in significant environmental problem-shifting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 3671–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Life cycle assessment: Past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Schau, E.M.; Lehmann, A.; Traverso, M. Towards life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3309–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Guzmán, V.; García-Cáscales, M.S.; Espinosa, N.; Urbina, A. Life cycle analysis with multi-criteria decision making: A review of approaches for the sustainability evaluation of renewable energy technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 104, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.S.; Cheun, J.Y.; Kumar, P.S.; Mubashir, M.; Majeed, Z.; Banat, F.; Ho, S.H.; Show, P.L. A review on conventional and novel materials towards heavy metal adsorption in wastewater treatment application. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razman, K.K.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Mohammad, A.W. An overview of LCA applied to various membrane technologies: Progress, challenges, and harmonization. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 27, 102803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goglio, P.; Williams, A.G.; Balta-Ozkan, N.; Harris, N.R.; Williamson, P.; Huisingh, D.; Zhang, Z.; Tavoni, M. Advances and challenges of life cycle assessment (LCA) of greenhouse gas removal technologies to fight climate changes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelton, R.E.O.; Smith, T.M. Hotspot scenario analysis: Comparative streamlined LCA approaches for green supply chain and procurement decision making. J. Ind. Ecol. 2015, 19, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byggeth, S.; Hochschorner, E. Handling trade-offs in ecodesign tools for sustainable product development and procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Interrogating greenhouse gas emissions of different dietary structures by using a new food equivalent incorporated in life cycle assessment method. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Börjesson, P. Environmental impact of dietary change: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detzel, A.; Krüger, M.; Busch, M.; Blanco-Gutiérrez, I.; Varela, C.; Manners, R.; Bez, J.; Zannini, E. Life cycle assessment of animal-based foods and plant-based protein-rich alternatives: An environmental perspective. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5098–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiolo, S.; Parisi, G.; Biondi, N.; Lunelli, F.; Tibaldi, E.; Pastres, R. Fishmeal partial substitution within aquafeed formulations: Life cycle assessment of four alternative protein sources. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1455–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermeersch, T.; Alvarenga, R.A.F.; Ragaert, P.; Dewulf, J. Environmental sustainability assessment of food waste valorization options. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 87, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.M.; Iris, K.M.; Hsu, S.C.; Tsang, D.C. Life-cycle assessment on food waste valorisation to value-added products. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Lo, W.; Othman, M.H.D.; Liang, X.; Goh, H.H.; Chew, K.W. Influence of Fe2O3 and bacterial biofilms on Cu(II) distribution in a simulated aqueous solution: A feasibility study to sediments in the Pearl River Estuary (PR China). J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbrandt, K.; Chu, P.L.; Simmonds, A.; Mullins, K.A.; MacLean, H.L.; Griffin, W.M.; Saville, B.A. Life cycle assessment of lignocellulosic ethanol: A review of key factors and methods affecting calculated GHG emissions and energy use. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 38, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Q.; Eckelman, M.; Zimmerman, J. Meta-analysis and harmonization of life cycle assessment studies for algae biofuels. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 9419–9432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, S.N.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Noor, N.M. Rice straw utilisation for bioenergy production: A brief overview. Energies 2022, 15, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Lehman, C.; Trost, J.J. Sustainable intensification of high-diversity biomass production for optimal biofuel benefits. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, I.; Sahajpal, R.; Zhang, X.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Gross, K.L.; Robertson, G.P. Sustainable bioenergy production from marginal lands in the US Midwest. Nature 2013, 493, 514–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Dale, B.E.; Martinez-Feria, R.; Basso, B.; Thelen, K.; Maravelias, C.T.; Landis, D.; Lark, T.J.; Robertson, G.P. Global warming intensity of biofuel derived from switchgrass grown on marginal land in Michigan. GCB Bioenergy 2023, 15, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.L.; Duc, P.A.; Mathimani, T.; Pugazhendhi, A. Evaluating the potential of green alga Chlorella sp. for high biomass and lipid production in biodiesel viewpoint. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.P.; Lee, M.; Chiueh, P.T. Creating ecosystem services assessment models incorporating land use impacts based on soil quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiani, M.; Sinkko, T.; Caldeira, C.; Tosches, D.; Robuchon, M.; Sala, S. Critical review of methods and models for biodiversity impact assessment and their applicability in the LCA context. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Long, S.P.; Smith, P.; Banwart, S.A.; Beerling, D.J. Technologies to deliver food and climate security through agriculture. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, S.M.; Soussana, J.F.; Tubiello, F.N.; Chhetri, N.; Dunlop, M.; Meinke, H. Adapting agriculture to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19691–19696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijungs, R.; Suh, S. The Computational Structure of Life Cycle Assessment; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Plevin, R.J.; Delucchi, M.A.; Creutzig, F. Using attributional life cycle assessment to estimate climate-change mitigation benefits misleads policy makers. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidema, B.P. Market Information in Life Cycle Assessment; Danish Environmental Protection Agency (Miljøstyrelsen): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; Volume 863, p. 365.

- Ekvall, T.; Tillman, A.M.; Molander, S. Normative ethics and methodology for life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zink, T.; Geyer, R.; Suh, S.; Bergesen, J.D. Formalizing Consequential Inventory Modeling: A Quantitative Framework to Facilitate Consistency Between Studies; Les Diablerets: Ormont-Dessus, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson, R.; Kushnir, D.; Molander, S.; Sandén, B.A. Energy and resource use assessment of graphene as a substitute for indium tin oxide in transparent electrodes. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Two sides of the same coin: Consequential life cycle assessment based on the attributional framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Heijungs, R. On the use of different models for consequential life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucurachi, S.; Yang, Y.; Bergesen, J.D.; Qin, Y.; Suh, S. Challenges in assessing the environmental consequences of dietary changes. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2016, 36, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Sim, S.; Hamel, P.; Bryant, B.; Noe, R.; Mueller, C.; Rigarlsford, G.; Kulak, M.; Kowal, V.; Sharp, R.; et al. Life cycle assessment needs predictive spatial modelling for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, M.C.; Taylor, C.M. The changing nature of life cycle assessment. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 82, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.E.; Blair, P.D. Input–Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R. On the structure of linear models. Econometrica 1952, 20, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.R. Comparison of input–output, input–output+ econometric and computable general equilibrium impact models at the regional level. Econ. Syst. Res. 1995, 7, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, A. Input–output economics and computable general equilibrium models. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 1995, 6, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. A unified framework of life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, D. Consequential life cycle assessment of policy vulnerability to price effects. J. Ind. Ecol. 2014, 18, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Chichakli, B.; von Braun, J.; Lang, C.; Barben, D.; Philp, J. Policy: Five cornerstones of a global bioeconomy. Nature 2016, 535, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Land Statistics 2001–2022—Global, Regional and Country Trends; FAOSTAT Analytical Briefs, No. 88; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Winters-Michaud, C.P.; Haro, A.; Callahan, S.; Bigelow, D.P. Major Uses of Land in the United States, 2017 (Report No. EIB-275); U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. Bulletin of Major Data from the Third National Land Survey; Government of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- FANC. Land Use in Germany in 2014–2016. Available online: https://www.bfn.de/en/service/facts-and-figures/the-utilisation-of-nature/land-use-overview/land-use-in-germany.html (accessed on 21 May 2019).

- Tyszler, H.B.M.; Braconi, M.V.P.N.; van Rijn, N.D.J. Agri-Footprint 6 Methodology Report; Blonk Consultants: Gouda, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). LCA Digital Commons: Data and Community for Life Cycle Assessment. Available online: http://www.lcacommons.gov/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Frederick, J.R.; Camberato, J.J. Water and nitrogen effects on winter wheat in the Southeastern Coastal Plain: I. Grain yield and kernel traits. Agron. J. 1995, 87, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fargione, J.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D.; Polasky, S.; Hawthorne, P. Land clearing and the biofuel carbon debt. Science 2008, 319, 1235–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, K.G.; Jones, J.P.H.; Clark, C.M. A review of domestic land use change attributable to U.S. biofuel policy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lark, T.J.; Salmon, J.M.; Gibbs, H.K. Cropland expansion outpaces agricultural and biofuel policies in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 044003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.; Heimlich, R.; Houghton, R.A.; Dong, F.; Elobeid, A.; Fabiosa, J.; Tokgoz, S.; Hayes, D.; Yu, T.H. Use of U.S. croplands for biofuels increases greenhouse gases through emissions from land-use change. Science 2008, 319, 1238–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Renewables 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2023 (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Lark, T.J.; Clark, C.M.; Yuan, Y.; LeDuc, S.D. Grassland-to-cropland conversion increased soil, nutrient, and carbon losses in the U.S. Midwest between 2008 and 2016. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 054018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Khanna, M. Land use effects of biofuel production in the U.S. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 055007. [Google Scholar]

- National Supply Company. Acompanhamento da Safra Brasileira de cana-de-açúcar V.8—Safra 2021/22—N.2—Segundo Levantamento|Agosto 2021 (Monitoring the Brazilian Sugarcane Harvest V.8—2021/22 Crop—N.2—Second Survey. August 2021); National Supply Company: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA. Projeções do Agronegócio: Brasil 2020/21 a 2030/31—Projeções de longo Prazo (Agribusiness Projections: Brazil 2020/21 to 2030/31—Long Term Projections); MAPA: Brasília, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmawan, A.H.; Fauzi, A.; Putri, E.I.; Pacheco, P.; Dermawan, A.; Nuva, N.; Amalia, R.; Sudaryanti, D.A. Bioenergy policy: The biodiesel sustainability dilemma in Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.E.; Plevin, R.J.; Turner, B.T.; Jones, A.D.; O’Hare, M.; Kammen, D.M. Ethanol can contribute to energy and environmental goals. Science 2006, 311, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Nelson, E.; Tilman, D.; Polasky, S.; Tiffany, D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11206–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wu, M.; Huo, H. Life-cycle energy and greenhouse gas emission impacts of different corn ethanol plant types. Environ. Res. Lett. 2007, 2, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daioglou, V.; Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; Müller, C.; Wicke, B.; Faaij, A.; van Vuuren, D.P. Greenhouse gas emission curves for advanced biofuel supply chains. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Takriti, S.; Malins, C.; Searle, S. Understanding options for ILUC mitigation. Int. Counc. Clean Transp. Work. Pap. 2016, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam, V.; Kuntom, A.; Zainal, H.; Loh, S.K.; Aziz, A.A.; Parveez, G.K.A. Analysis of the uncertainties of the inclusion of indirect land use change into the European Union Renewable Energy Sources Directive II. J. Oil Palm Res. 2019, 31, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, T.W.; Golub, A.A.; Jones, A.D.; O’Hare, M.; Plevin, R.J.; Kammen, D.M. Effects of US Maize Ethanol on Global Land Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Estimating Market-Mediated Responses. BioScience 2010, 60, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Elgowainy, A.; Lee, U.; Baek, K.H.; Balchandani, S.; Benavides, P.T.; Burnham, A.; Cai, H.; Chen, P.; Gan, Y.; et al. Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Technologies Model® (2023 Excel); Computer Software; USDOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE): Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Renewable Fuel Standard Program (RFS2) Regulatory Impact Analysis; United States Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Plevin, R.J.; Jones, A.D.; Torn, M.S.; Gibbs, H.K. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Biofuels’ Indirect Land Use Change Are Uncertain but May Be Much Greater than Previously Estimated. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8015–8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyner, W.E.; Taheripour, F.; Zhuang, Q.; Birur, D.; Baldos, U. Land Use Changes and Consequent CO2 Emissions Due to US Corn Ethanol Production: A Comprehensive Analysis; Department of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2010; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M.; Schmidt, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Palm Oil at United Plantations Berhad 2022, Results for 2004–2021. Summary Report; United Plantations Berhad: Teluk Intan, Malaysia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa, M.; Schmidt, J.; Pasang, H. Industry-Driven Mitigation Measures Can Reduce GHG Emissions of Palm Oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Joint Research Centre. Institute for Energy and Transport. Estimates of Indirect Land Use Change from Biofuels Based on Historical Data; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Ou, L.; Li, Y.; Hawkins, T.R.; Wang, M. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Biodiesel and Renewable Diesel Production in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7512–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevin, R.J.; Beckman, J.; Golub, A.A.; Witcover, J.; O’Hare, M. Carbon Accounting and Economic Model Uncertainty of Emissions from Biofuels-Induced Land Use Change. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 2656–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garraín, D.; De La Rúa, C.; Lechón, Y. Consequential Effects of Increased Biofuel Demand in Spain: Global Crop Area and CO2 Emissions from Indirect Land Use Change. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 85, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.V.; Wiedemann, S.G.; Simmons, A.; Clarke, S.J. The Environmental Consequences of a Change in Australian Cotton Lint Production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 2321–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheripour, F.; Mueller, S.; Emery, I.; Karami, O.; Sajedinia, E.; Zhuang, Q.; Wang, M. Biofuels induced land use change emissions: The role of implemented land use emission factors. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimann, T.; Argueyrolles, R.; Reinhardt, M.; Schuenemann, F.; Söder, M.; Delzeit, R. Phasing out palm and soy oil biodiesel in the EU: What is the benefit? GCB Bioenergy 2024, 16, e13115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbelle-Rico, E.; Sánchez-Fernández, P.; López-Iglesias, E.; Lago-Peñas, S.; Da-Rocha, J.M. Putting land to work: An evaluation of the economic effects of recultivating abandoned farmland. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Qin, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, M.; Taheripour, F.; Tyner, W.; O’Connor, D.; Duffield, J. Life cycle energy and greenhouse gas emission effects of biodiesel in the United States with induced land use change impacts. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 251, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, R.M.; Scharlemann, J.P.; Balmford, A.; Green, R.E. Do increases in agricultural yield spare land for nature? Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 1716–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, F.R.; Wallington, T.J.; Everson, M.; Kirchain, R.E. Strategic materials in the automobile: A comprehensive assessment of strategic and minor metals use in passenger cars and light trucks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 14436–14444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, J.W.; McCord, G.C. Fertilizing growth: Agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. J. Dev. Econ. 2017, 127, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, V. Water and agriculture in India. In Background Paper for the South Asia Expert Panel during the Global Forum for Food and Agriculture; Business Association: New Delhi, India, 2017; Volume 28, pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cammarano, D.; Jamshidi, S.; Hoogenboom, G.; Ruane, A.C.; Niyogi, D.; Ronga, D. Processing tomato production is expected to decrease by 2050 due to the projected increase in temperature. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.C.C.; Fortini, R.M.; Neves, M.C.R. Impacts of the use of biological pest control on the technical efficiency of the Brazilian agricultural sector. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassaletta, L.; Billen, G.; Grizzetti, B.; Anglade, J.; Garnier, J. Fifty-year trends in nitrogen use efficiency of world cropping systems: The relationship between yield and nitrogen input to cropland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 105011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]