Abstract

The objective of this study is to analyse the challenges and opportunities that Precision Farming (PF) offers for agriculture in Chile, highlighting the possibilities it offers for solving agricultural problems as well as the challenges that hinder its application by small- and medium-sized farmers. A qualitative content analysis was conducted on technical government publications and academic publications focused on precision agriculture, which highlighted the elements that hinder the implementation of PF in smaller agricultural systems, i.e., small farmers. The results show that among the main problems that PF can help solve are spring frosts, low product calibre, fruit rot, low sugar content in fruit, and water stress, among others. The solutions that PA could offer, as outlined in the review, are varied and include frost forecasting, crop monitoring, application of inputs, and selection of more drought-tolerant crops, to name a few. On the other hand, another relevant finding is the fact that small farmers face structural difficulties in accessing PF technologies, due to their high cost (technology transfer) but also to the lack of support from state institutions.

Keywords:

adoption of technologies; digital agriculture; precision agriculture; precision farming; smallholder farmers; smart technologies JEL Classification:

Q15; Q16; Q18; Q24; Q25

1. Introduction

Globally, despite the increase in agri-food production, a significant portion of the population cannot access a healthy diet, resulting in malnutrition problems. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United (FAO) [1], approximately 3,139,500 people suffer from poor nutrition. At the same time, obesity is a current problem that affects nearly 650 million individuals globally [2]. This makes the agricultural sector more demanding and complex, facing multiple challenges. One such challenge is becoming more efficient and sustainable in the face of ever-increasing global food demand. In this scenario, it is essential to establish a sustainable food system to ensure food quality and safety in society [3,4]. This is because agricultural production has a considerable impact on the environment and health [5]. Therefore, increasing efficiency and sustainability in agriculture becomes a priority [6,7].

With the digital revolution, daily life is undergoing significant transformations as it benefits from current technologies [8]. However, to take advantage of this, it is necessary to have the relevant knowledge and tools. In the agricultural sector, one of the current technologies is Precision Farming (PF). This technological advance ranges from basic drones to 5G robots equipped with connected sensors that can accurately anticipate a plant’s water demand in real time. PF involves the use of technologies such as Global Positioning System (GPS), aerial imagery, remote sensors, satellites, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) [9].

At this point, it is vital to distinguish between ‘technology’ and ‘intelligent technologies’. ‘Technology’ refers to any device or machine used to perform a task [10], while ‘smart technologies’, on the other hand, have the ability to learn and adjust their performance independently over time [11]. Although PF arrived in Chile in the 1990s, its large-scale adoption was evident in the 2017 agricultural census. It projected growth of 13.19% for Chile from 2019 to 2025. This brings the country closer to countries such as Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Peru, which have growth rates of 16.1%, 16.86%, 16.8%, and 13.78%, respectively [12].

However, despite the continuous progress of PF worldwide, the literature in Latin America presents significant gaps regarding its implementation among smallholder farmers. Several recent reviews agree that regional research has focused mainly on large producers, technological assessments of PF, or general sectoral diagnoses [13,14]. Likewise, recent studies indicate that the adoption of digital technologies by smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries—such as Chile—is limited by structural inequalities, connectivity gaps, and institutional constraints, factors that reduce their ability to benefit from digital innovation and, in this case, PF [13,14,15]. Recent research has pointed out that the accessibility and affordability of digital technologies, together with limited rural connectivity and technological exclusion, are central obstacles for smallholder farmers [16].

This work assumes that the diffusion of technological innovations depends on the existence of channels through which innovations are communicated. In this regard, Rogers [17] recognises the existence of five relevant elements in diffusion: communication channels, time, adopters, the social system, and the innovation itself. Diffusion, then, is ‘the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system’. Diffusion is also often promoted by change agents who are defined as individuals ‘who influences clients’ innovation decisions in a direction deemed desirable by a change agency’. This perspective has been used by various authors to understand the incorporation of technological innovations in the agricultural sector [18,19,20,21].

However, a significant theoretical gap remains. The literature describes the technologies, benefits, and success stories, but does not explain why smallholder farmers adopt these tools so little, even when the evidence is clear [22,23]. There are likely structural barriers and institutional constraints that deserve examination. Most studies analyse these factors separately, leaving a fundamental question unanswered: how do these barriers combine, and how do they actually affect PF adoption? [24,25]. Furthermore, the literature does not examine the real feasibility of smart technologies in small farms, where minimum conditions of connectivity, training, and financing are often not present [26,27]. For all these reasons, there is still no clear conceptual model to explain PF adoption in small-scale agriculture in Latin America. This study contributes to filling that gap.

In Chile, small farmers perceive the adoption of precision technologies as a high-cost, high-risk innovation, which limits their access to these tools already available on the Chilean market [25]. Although there are documented experiences of PF for specific, high-value sectors—such as dairy farming and some export-oriented fruit crops—scientific evidence on its adoption in family farming remains limited and fragmentary [28,29].

The main objective of this article is to address the challenges and opportunities for Chilean agriculture exploring the importance of PF as a possible solution for improving efficiency, especially in the case of small farmers. This study presents an innovative approach by combining international evidence on digital agriculture with a critical analysis of the Chilean context, where gaps still exist regarding the structural conditions that influence the adoption of these technologies and where state change agents [17] play an important role in disseminating technological innovations among small farmers. By focusing the analysis on smallholder farmers, this research provides fundamental evidence for understanding the interaction of existing barriers and their direct impact on the viability of family farming in Chile.

The article is a contribution to scientific production in this field, given that the literature shows scant evidence of PF developed by small farmers in Latin America. The relevance of this approach lies in the importance of small-scale agriculture in this context. According to FAO data, 80% of all farms are family farms [30]. Meanwhile, globally, more than 90% of farms are of this type [31].

2. Bibliographic Discussion

To understand the situation of small farmers in PF from a more technical perspective and explore it in greater depth, a literature search was conducted in the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus indexed databases. The search criteria and results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search in WoS and Scopus indexed databases.

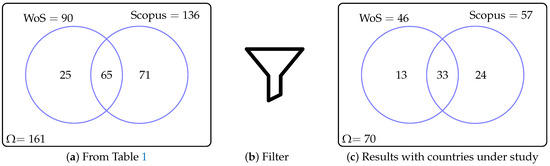

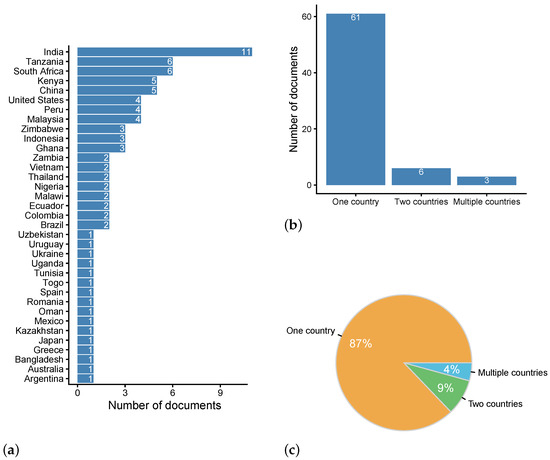

Figure 1a presents a schematic representation of the combined results of the WoS and Scopus databases, according to the search criteria described in Table 1, using a Venn diagram. Subsequently, a filtering process is applied to identify the countries that are the subject of study in the literature, by searching the title, abstract, and keywords. Eighty-six observations per country document were found, distributed across 70 documents (Figure 2a–c). These are represented in the Venn diagram in Figure 1c, which shows a selection of the documents analysed and presented in Table 2. These include Latin American countries such as Mexico, Peru, and Colombia, as well as other countries such as China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Ukraine, and Malaysia. They are mainly focused on adopting PF technologies using different techniques or methods such as Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), SEM based on Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA), Artificial Intelligence (AI), Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Figure 1.

Bibliometric process: (a) Venn chart, showing search results on title, abstract, and keywords with the script (“Knowledge Management” AND “Reverse Logistics”) on WoS and Scopus indexed databases (WoS = 90, Scopus = 136, WoS-Scopus = 25, WoS ∩ Scopus = 65, Scopus-WoS = 71, and WoS = 161). (b) Filter: Countries of study in the title, abstract and keywords. (c) Results after filtering (WoS = 46, Scopus = 57, WoS-Scopus = 13, WoS ∩ Scopus = 33, Scopus-WoS = 24, and WoS = 70).

Figure 2.

Countries as the subject of study in Figure 1c: (a) Number of documents by countries. (b) Number of documents by category according to number of countries. (c) Percentages by category according to number of countries.

Table 2.

Summary of documents with countries under study in WoS and/or Scopus.

This study seeks to highlight the challenges and opportunities that PF poses for the sector among small Chilean farmers, compiling the problems and corresponding solutions identified in various publications.

3. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted through qualitative content analysis applied to institutional technical documents and articles published in scientific journals. The details of the research procedure are shown below.

Research Procedure

These publications focus on agriculture and the acquisition of precision farming technologies, with the aim of identifying the main opportunities and challenges that this brings, particularly for small farmers, with a focus on the Chilean context. This purpose has been summarised in four questions that this investigation seeks to answer:

- What are the main problems and solutions affecting fruit production and agriculture in general?

- Are there significant disparities in access to technologies by smallholder farmers compared to their larger-scale counterparts?

- What are the concrete benefits of using smart technologies in the context of sustainable development?

- What are the specific challenges faced by smallholder farmers in accessing and adopting smart technologies?

Source selection criteria: The selection of documents analysed was diverse, in accordance with the objective of the research.

- Thematic relevance: These are publications produced by government entities and intergovernmental organisations that address smallholder production and the use of precision technologies, highlighting problems or challenges in the sector, as well as solutions offered by precision technologies.Empirical studies and reviews addressing the socio-economic viability of PF, as well as the identification of limiting factors (costs, knowledge, infrastructure) in small- and medium-scale agriculture, both in Chile and in developing countries, were included in the review. Meanwhile, documents focused solely on the technical validation of hardware/software (e.g., sensor programming, imaging algorithms) without considering social or economic implementation were excluded.

- Type of institution: In the case of technical publications produced by Chilean government institutions, a search was conducted among the documents available on the websites of specialised agencies, such as Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias (INIA) and Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (CORFO), among others, which were important for analysing institutional requirements and local impact data. In addition, publications from international organisations were consulted, whether or not the organisations were strictly linked to the agricultural sector.

- Geographical scope: Technical publications produced by governmental and intergovernmental organisations should focus primarily on the experience of Chilean or Latin American farmers. In the case of scientific publications in the Scopus database, this criterion was not applied, with the aim of gathering a greater number of resources.

- Time frame: In the case of governmental and intergovernmental publications, the period covered corresponds to the years 2019 to 2025. In other words, publications appearing within that time frame were considered. Meanwhile, the scientific publications considered are those published in the Scopus database between 2019 and 2025.

- Accessibility and completeness: Both government and intergovernmental technical publications, as well as scientific publications, should be available in their full format for analysis.

Content analysis method: This is a qualitative inquiry, as it involves the analysis and interpretation of reality through the use of instruments that reproduce and compile it, such as reading notes [43]. The qualitative content analysis of documents was based on an analytical circles strategy. This means that consecutive immersions in the documentary sources were carried out to collect data until a point or moment of information saturation was reached. Subsequently, these were analysed to produce working notes, which were described and classified for interpretation. In this context, the analysis followed a process based on coding [44] and in repeated cycles of reading [45].

- General reading: After collection and storage, the documents were read in general terms and then read again in detail, focusing on finding answers to the questions raised above. The reading was accompanied by continuous note-taking.

- Encoding: In a second stage, texts were segmented and coded. Notes were made on ideas. The analysis process was mixed, in the sense that it incorporated the determination of categories deductively, but the coding of text segments allowed subcategories to be defined inductively [45]. These subcategories, in turn, were associated with the previously determined categories.

- Categories: The deductively defined categories are associated with the topics contained in the four questions that guided the research. Given that this is a spiral analysis, the reading and coding exercise was carried out repeatedly, adjusting codes and stabilising the subcategories (Show Table 3). This exercise made it possible to achieve information saturation.

Table 3. Encoding.

Table 3. Encoding. - Interpretation: Finally, an interpretation of the resulting categories and subcategories was carried out, with the aim of finding patterns that would allow us to answer the questions posed as part of the study’s objective.

4. Results

4.1. What Are the Most Significant Problems and Solutions Affecting Fruit Production and Agriculture as a Whole?

Chile stands out on the global stage as a supplier of a wide range of products. Despite this variety, the nation’s agricultural exports focus on fruit and wine production [46]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the factors that impact fruit production and agriculture in general. These factors include frost, fruit quality, soil amendments, diseases, colour, lack of sugar, rot, and water availability, as presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

PF solutions to agricultural problems.

Table 5.

Research associated with solutions to problems in agriculture.

4.2. Are There Significant Disparities in Access to Technologies by Smallholder Farmers Compared to Their Larger-Scale Counterparts?

This raises a substantial challenge related to the cost associated with the acquisition and application of precision technologies, compounded by a partial understanding of these technologies [73]. In response to this problem, various government institutions have implemented policies and programmes to address these issues. Notable examples are the INIA [74] and the Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario (INDAP) [75], both committed to comprehensive research in agriculture and providing important knowledge to farmers. These initiatives aim to promote the adoption of emerging technologies PF and simplify their application on farmers’ land.

In addition to conducting research in the agricultural field, INIA has the support of consultants whose objective is to provide educational advice to farmers. However, this ‘advisor’ can only be useful if the farmer is a member of INDAP and meets the requirements stipulated in Organic Law No. 18,910 INDAP [74]. These requirements include

- Assets not exceeding 3500 Unidades de Fomento (UF).

- Exploitation of an area of land not exceeding 12 hectares with basic irrigation or residing and working in the countryside.

- Income mainly derived from agricultural exploitation or forestry and agricultural activity [76].

The problem is immediately apparent, especially for fruit growers, as most of them own less than 12 hectares of land. According to the 2022 Census [77], this represents 66.3% of Agricultural Production Unit (APU) smaller than 20 hectares. This limitation hinders their access to the markets and resources necessary to achieve success. CORFO [78], a government agency, offers various programmes and services to support farmers in developing their business ideas, providing financing, loans and grants. CORFO also encourages the creation of associations and networks for the adoption of innovative initiatives, contributing to the export of products to international markets and supporting the green and sustainable economy, as well as the development of environmentally friendly agricultural practices.

Despite the efforts of CORFO and other government agricultural institutions, a barrier remains for small farmers. With less than 20 hectares, they face difficulties in interacting with these institutions, leaving them in a kind of limbo, in which agricultural progress in terms of technology in Chile is slow [79].

Farmers with greater resources, on the other hand, can afford to use PF to improve their operations [80]: (1) drones to monitor their crops and detect pests and diseases, (2) sensors to collect data on climate, soil, and crops, (3) software to manage their operations and make more informed decisions, and (4) social media to connect with other farmers and share information.

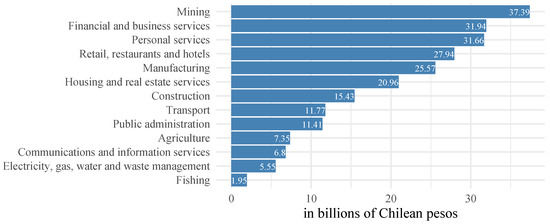

Figure 3 reveals that the agricultural sector contributes 7.35% to the nation’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2022. Given the importance of agriculture to the national economy, it is crucial to consider the benefits of adopting smart technologies, especially for smallholder farmers.

Figure 3.

Distribution of GDP by economic activity in Chile in 2022 [81].

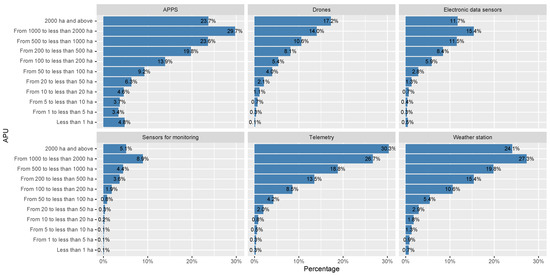

Figure 4 shows the percentages of technology use according to the size of the APU, where it can be seen that as the size of the APU increases, so does the percentage of technology use. This use is considerably low in APUs smaller than 20 hectares for the six technologies evaluated. Only the use of mobile applications is somewhat more widespread among small farmers.

Figure 4.

Technology for APU 1. 2021 Agricultural Census: 1 https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/economia/agricultura-agroindustria-y-pesca/censos-agropecuarios, accessed 5 December 2025.

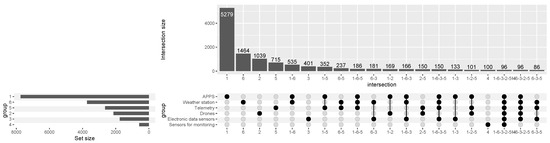

Figure 5 shows the 20 main interactions between the six technologies: ‘APPS’ with 7743, ‘Weather station’ with 3730, ‘Telemetry’ with 2645, “Drones” with 2138, ‘Electronic data sensors’ with 1758, and ‘Monitoring sensors’ with only 585 APU. In terms of the main interactions, ‘APPS’ stands out with 5279, ‘Weather Station’ with 1464, ‘Drones’ with 1039, “Telemetry” with 715 and ‘Electronic Data Sensors’ with 401. In combination, we observe ‘APPS-Weather station’ with 535, ‘APPS-Telemetry’ with 352, ‘Weather station-Telemetry’ with 237, and ‘APPS-Weather station-Telemetry’ with 186, among others.

Figure 5.

Technology Interaction (2021 Agricultural Census).

4.3. What Are the Specific Benefits of Using Smart Technologies in the Context of Sustainable Development?

Frost detection: One concrete benefit is remote sensing, which can help farmers monitor spring and winter frosts in real time, using aeroplanes, satellites, buoys or ships to collect data on the phenomenon. Farmers can use this information to make informed decisions about how to protect their crops. However, to take advantage of remote sensing, farmers must familiarise themselves with the relevant programmes, available on tablets, computers, and mobile phones. This skill will enable them to respond quickly to natural events that could affect their productivity [82].

Support in decision-making: Another benefit is the improvement in the quality of decision-making in agriculture, which is essential to guaranteeing global food supplies. This involves strengthening the quality of communications between the scientific community, the political sphere, and farmers, fruit growers, and livestock breeders themselves [83].

Although solutions are available, in practice they do not reach all smallholder farmers. This is due to a number of factors, such as lack of access to technology, lack of training, and lack of awareness and knowledge about the benefits of remote sensing [84]. It is imperative to take action to address these challenges so that all farmers can benefit from these tools.

Water Resource Management: Efficient water resource management is a complex challenge, exacerbated by the complexity introduced by climate change. Water scarcity poses a threat to all stakeholders involved in agriculture. PF stands as a possible solution, using technologies to collect data on soil, plants, and climate. This information provides essential data for making crucial decisions on irrigation, fertilisation and other agricultural techniques, enabling farmers to use water more efficiently, increase production and improve the quality of their crops [9]. In this regard, INDAP [85] highlights the experience of a small farmer in Valparaíso who has achieved a 50% saving in irrigation water, as well as reducing the use of chemicals. The farmer points out that ‘It is a self-compensating drip irrigation system with an automatic control panel where the same amount of water falls on each plant. It is a precision irrigation system that I recommend to everyone. With normal irrigation, I used to spend two hours a day watering each sector, and with this system, I can water five times a day for ten minutes each time.’ [86]. It is also possible to verify the experience of small farmers in the Metropolitan Region, who have implemented monitoring and irrigation stations that allow them to efficiently manage water use, thanks to one company, which has managed to save 20% of water per hectare each year.

Finally, the agricultural innovation tool called ‘Smartfield’, implemented with small farmers in the Maule, Ñuble and Biobío regions, has enabled some farmers to intelligently monitor and properly manage the frequency of irrigation in berry plantations [87]. One smallholder farmer notes, ‘Thanks to smart monitoring, I knew when and how much to irrigate (…). The changes have been very noticeable (…) In three seasons, we went from 15,000 to 20,000 kilos per hectare.’

4.4. What Are the Specific Challenges Faced by Smallholder Farmers in Accessing and Adopting Smart Technologies?

One of the challenges is the implementation of PF, which entails considerable costs, given that the sensors and technology required are very expensive. In addition, training is essential for farmers to be able to use this technology efficiently, which could result in PF not being accessible to all farmers [56]. For example, the Fundación para la Innovación Agraria carried out an innovation project in the O’Higgins and Maule regions consisting of the use of real-time multispectral images for apple and peach production by small farmers. However, they ultimately did not adopt the technology, as it is still in the process of being perfected and also due to the constrained economic situation facing the fruit production business [88].

Sustainability and accessibility to water continue to be two of the most significant challenges for agriculture as a whole. This problem presents other technological solutions beyond PF:

Wastewater Treatment From Regenerative Agriculture: Uses unique biological processes to clean wastewater, making it suitable for irrigation or industrial use. This technology helps reduce the environmental impact of agriculture and save water [89].

Water Management: This involves the design, construction, and operation of irrigation and drainage systems, helping farmers use water more efficiently and protecting the environment [90].

Water Efficiency: Develops techniques for farmers to save water, such as the use of drip irrigation, high-efficiency sprinkler irrigation systems, and smart drip irrigation, among others [91,92].

Water Footprint: Defines the total amount of fresh water used to produce a product in a specific place and time, and is a vital indicator for assessing water use in agriculture [93] There are numerous additional technological solutions, such as the Watergen machine [94], capable of creating water from the air, rainwater harvesting [95], desalination [96] and water conservation [97]. However, access to these solutions depends on the tools and knowledge necessary for their implementation.

5. Discussion

PF is important when it comes to optimising agricultural sustainability [98]. However, small farmers in Chile face challenges in adopting it, such as the high cost of implementation, maintenance, and specialised knowledge in the field. Profit margins are limited and access to financing is restricted due to bureaucratic obstacles [99]. These factors hinder the acquisition of PF tools.

Small-scale farmers in Chile tend to use plots of land that are considerably small in size. As a result, the fragmentation of agricultural land is high. This factor restricts the effective implementation of PF technologies, given that many of these tools are designed for larger farms [100].

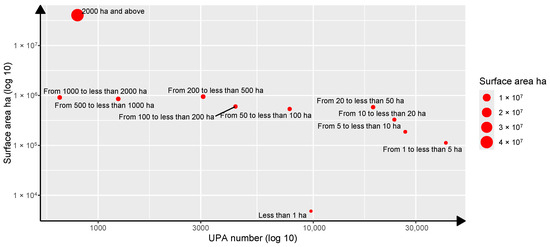

According to Wegerif and Guereña [101], land inequality is a central component of current social inequality. Globally, land is concentrated in large estates, while small farmers and communities have less access. In the context of Chile, there is significant land concentration, with a small number of farmers owning most of the hectares, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

APU (Number, Surface Area) (2021 Agricultural Census: https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/economia/agricultura-agroindustria-y-pesca/censos-agropecuarios, accessed on 5 December 2025): Less than 1 ha (9760, 4813); From 1 to less than 5 ha (41364, 112372); from 5 to less than 10 ha (26782, 187204); from 10 to less than 20 ha (23827, 328165); from 20 to less than 50 ha (18987, 583233); from 50 to less than 100 ha (7771, 535992); from 100 to less than 200 ha (4352, 600644); from 200 to less than 500 ha (3079, 946854); from 500 to less than 1000 ha (1241, 854083); from 1000 to less than 2000 ha (663, 911699); 2000 ha and above (802, 40677507).

Smallholder farmers face not only inequality in land ownership. They also face other structural disadvantages that limit their access to infrastructure, networks and technologies [102]. It is important to note that access to digital agricultural technologies is often more difficult for smallholder farmers, given the financial constraints they typically face [103]. In this context, smallholder farmers are at a disadvantage compared to large-scale farmers. There is significant inequality between large and small farmers, as well as between developed and developing countries [104].

In line with the above, the widespread adoption of technologies among farmers is limited to large agricultural enterprises. They have greater resources and capabilities to invest in digitisation processes, which gives them a significant advantage in terms of efficiency and expansion. Salgado et al. [80] states that “Large-scale farms have the capacity to implement PF and Artificial Intelligence systems (…) that optimise crop planning, supply management (…) and distribution logistics. (…) In contrast, small producers face significant barriers stemming from financial constraints and lack of access to adequate digital infrastructure”.

Technologies designed for rural areas, such as remote sensing, must be adapted so that small farmers can effectively meet their needs, adjusting to their requirements [105].

Among the most innovative precision farming technologies are soil and plant sensors for nutrient and water management, as well as satellite imagery and GIS for targeted management. These tools support the sustainable development of agriculture on commercial farms [106]. In addition, they offer customised solutions for smallholder farmers, demonstrating the potential of artificial intelligence systems to revolutionise agriculture with limited resources globally [107].

From an economic perspective, Law 18910 [108] establishing INDAP only supports ‘small agricultural producers and farmers’. This leaves out an important group: intermediate farmers. From the point of view of some small farmers, for example, in the dairy sector, innovation seems risky and costly [28]. That is why they adopt less technology than large farms. This aspect extends to Latin America. The cost of technology is one of the most frequently cited barriers by producers in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Chile [109,110]. According to FAO [111], the cost of sensors, gateways, drones, and network connections are ongoing expenses that many small farm owners cannot sustain.

From an institutional perspective, Chile’s Law 18910 [108] defines that ‘small producers’ are eligible for state support. In practice, this means having less than 12 hectares of basic irrigation or less than 3500 UF in assets [112,113]. Exceeding these limits means being exempt from the benefit. Thus, it is possible to find producers who are not ‘small’ but who also do not have the financial resources to innovate.

From a structural perspective, PF improves efficiency, but its implementation depends on the availability of water resources [91,114]. Water scarcity limits investment due to increased uncertainty and fear of economic losses [115]. Furthermore, the need for digital technologies to develop this type of agriculture could exacerbate existing inequalities [116]. In response to this situation, so-called ‘regenerative agriculture’ has emerged, which seeks to improve infiltration and increase water retention [117].

To overcome the obstacles faced by small farmers, strategies such as promoting cooperatives, providing subsidies, providing training and improving rural infrastructure, as well as researching appropriate technologies for small farms, are proposed. Additionally, it is worth considering some practical policy recommendations to strengthen small farmers’ access to PF technologies:

- Creation of a revolving fund: Facilitating the rotation of loans made by private or government institutions.

- State incentives for financing technological innovation projects in small-scale agriculture.

- Increase training programmes that integrate precision technologies with the principles of regenerative agriculture, emphasising integrated pest management through the conservation of functional biodiversity.

However, proposals of different kinds require an appropriate context in order to be implemented in such a way that they are sustainable over time. In this regard, from a political and environmental point of view, it is interesting to pay attention to circular economy plans that contribute to reducing production waste and reusing it [118]. However, this implies the existence of a political culture aligned with such objectives, capable of forging ad hoc institutions, as in the case of the European Green Deal [119,120]. And, certainly, from an institutional point of view, it is essential to improve the focus of state agencies (such as INDAP, CORFO, or other agents of change) on small farmers. Although this is also a major challenge, as it requires reducing existing levels of inequality [121,122], which mitigates the heterophilia of agents of change.

In this context, the originality of this work lies in showing that structural elements exist in Chile that make it difficult for small farmers to access precision technologies, which are effective for sustainable production. This is relevant because agriculture accounts for a significant proportion of the country’s production and, furthermore, small farmers make up a large portion of the country’s population.

Limitations

This work does not consider the use of interviews with relevant actors. Another limitation of this study is that it does not offer an in-depth discussion of the environmental and ethical aspects related to PF. This is an issue that deserves further investigation.

The study was conducted exclusively with qualitative data. It could be strengthened in the future by considering quantitative data in order to address, for example, the economic impacts of the use of precision technologies among small Chilean farmers facing environments with high Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA) [123].

6. Conclusions

PF is confirmed as a technologically feasible and environmentally necessary strategy for Chile’s agricultural sector in the context of the climate emergency and the need for water optimisation. However, the main finding of this research is the identification of a structural failure in governance and technology transfer that prevents PF from benefiting small-scale agriculture.

This work highlights the relationship between structural deficiencies in Chilean agriculture and access to PF technologies among small local farmers. It draws attention to issues such as lack of access to financial resources and institutional support, which hinder access to and effective use of technological tools, despite their proven results.

Chilean smallholder farmers are willing to adopt some more accessible technologies (such as technified irrigation and mobile big data), but this does not generate significant benefits, showing that technology alone is not enough. The problem is not one of technology adoption, but rather of access to capital to acquire these technologies and specialised knowledge.

Barriers in government support programmes continue to exclude smallholder farmers. This exclusion makes it difficult for farmers to invest in more comprehensive measures to address priority threats such as water scarcity and extreme events such as frost. This could be consistent with the criticism raised by Rogers [17]: due to the homophily present in change agents, they communicate better with users of higher status. Therefore, users of lower status are not the focus of change agents’ assistance. In terms of public policy, this creates an implementation bottleneck that should be addressed as a matter of priority with more agile financing mechanisms whose risk recognises the nature of small-scale agriculture.

In this regard, a recent regional study in the Valparaíso Region, Chile, conducted by the Undersecretary of Labour [124], highlights the structural deficiencies in governance and technology transfer that prevent small entrepreneurs from taking advantage of technologies. This identifies the following empirical barriers to technological adoption:

- Digitalisation gap and lack of access to basic equipment. There is a significant technological gap between large and small producers.

- Water scarcity is not only a driver for PF (technified irrigation) but also an economic brake that discourages investment.

- The lack of job training and technical support turns human capital into a bottleneck for the use of precision technologies that involve, among other things, data analysis.

- Socio-economic effects due to low technology adoption and the water crisis, which causes the sector to contract and reduces investment capacity.

- Increased costs: The lack of mechanisation and automation of processes among small farmers results in low productivity and high production costs.

Along with establishing the various difficulties involved in PF among small farmers, one area for future study could be the implementation of regenerative agriculture, which promotes an increase in organic matter and biodiversity in order to retain water resources and reduce some of the effects of climate change. On the other hand, it is suggested that future research consider conducting interviews with both small and large farmers regarding the adoption of PF technologies [125,126].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; methodology, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; software, R.C.; validation, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; formal analysis, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; investigation, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; resources, C.F.-C.; data curation, E.O., M.M. and R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, E.O., T.G., A.Á., C.F.-C., M.M. and R.C.; visualization, E.O., M.M. and R.C.; supervision, E.O., M.M. and R.C.; project administration, E.O., M.M. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the team at the Laboratorio Interdisciplinario de Comercio, Información y Tecnología (LICIT) at the Universidad Tecnológica Metropolitana for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in the publication of this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| APU | Agricultural Production Unit |

| CORFO | Corporación de Fomento de la Producción |

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| fsQCA | fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| INDAP | Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario |

| INIA | Instituto de Investigaciones Agropecuarias |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PF | Precision Farming |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modelling |

| UF | Unidades de Fomento |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| VUCA | Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United (FAO). The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges; The Future of Food and Agriculture, No. 4; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Obesidad y Sobrepeso. 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Munirah, A.; Norfarizan-Hanoon, N. Interrelated of food safety, food security and sustainable food production. Food Res. 2022, 6, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Strassner, C.; Ben Hassen, T. Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: Environment, Economy, Society, and Policy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuma, M.; Arthur, G.; Coopoosamy, R.; Naidoo, K. Incorporating cropping systems with eco-friendly strategies and solutions to mitigate the effects of climate change on crop production. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieliczko, B.; Floriańczyk, Z. Priorities for Research on Sustainable Agriculture: The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 15, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movilla-Pateiro, L.; Mahou-Lago, X.M.; Doval, M.I.; Simal-Gandara, J. Toward a sustainable metric and indicators for the goal of sustainability in agricultural and food production. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 1108–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Digital Technologies for a New Future (LC/TS.2021/43); United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2021; p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Real-Moreno, S.; Aragón-Rodríguez, F.; Castro-García, S.; Agüera-Vega, J. Aplicación del Aprendizaje Basado en Retos en la Agricultura de Precisión para una agricultura sostenible. Rev. Innovación Buenas Prácticas Docentes 2022, 11, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P. The Next Wave of Technologies: Opportunities from Chaos, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardamalia, M.; Bereiter, C. Smart technology for self-organizing processes. Smart Learn. Environ. 2014, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Villa, P. Latin America: Precision Agriculture CAGR 2019–2025. by Country. 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1184401/latin-america-precision-agriculture-cagr-country/ (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Dibbern, T.; Romani, L.; Massruhá, S. Drivers and Barriers to Digital Agriculture Adoption: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Challenges and Opportunities in Latin American. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Siraj, M.; Lu, X.; Qiyang, G. Digital agriculture technology adoption in low and middle-income countries—A review of contemporary literature. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1621851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbi, N.; Gumbi, L.; Twinomurinzi, H. Towards Sustainable Digital Agriculture for Smallholder Farmers: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioutas, E.D.; Charatsari, C.; De Rosa, M. Digitalization of agriculture: A way to solve the food problem or a trolley dilemma? Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Zec Vojinović, M.; Čehić Marić, A.; Oplanić, M. Factors influencing farmers’ adoption and willingness to accept sustainable production practices in Istria County, Croatia. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2025, 26, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermiliana, H.; Tupas, G.A.; Maksiri, W. Is Smart Farming the Future of Sustainable Agriculture? Insights from a Village-Level Innovation Adoption. J. Educ. Technol. Learn. Creat. 2025, 3, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colclasure, B.; Caldwell, J.; Granberry, T.; Rost, C.; Gasseling, B. First-year hemp farmers’ motives and resources to cultivate hemp. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2025, 14, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denashurya, N.I.; Nurliza; Dolorosa, E.; Kurniati, D.; Suswati, D. Overcoming Barriers to ISPO Certification: Analyzing the Drivers of Sustainable Agricultural Adoption among Farmers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lioutas, E.D.; Charatsari, C.; La Rocca, G.; De Rosa, M. Key questions on the use of big data in farming: An activity theory approach. NJAS Wageningen J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K.; Knezevic, I. Big Data in food and agriculture. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Chilvers, J. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening Responsible Innovation in an Era of Smart Farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Rose, D. Dealing with the game-changing technologies of Agriculture 4.0: How do we manage diversity and responsibility in food system transition pathways? Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 24, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; Klerkx, L.; Ayre, M.; Dela Rue, B. Managing Socio-Ethical Challenges in the Development of Smart Farming: From a Fragmented to a Comprehensive Approach for Responsible Research and Innovation. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotz, S.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Martin, R.C. Situating tenure, capital and finance in farmland relations: Implications for stewardship and agroecological health in Ontario, Canada. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 46, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisier, G.; Hahn, K.; Geldes, C.; Klerkx, L. Unpacking the Precision Technologies for Adaptation of the Chilean Dairy Sector. A Structural-functional Innovation System Analysis. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2021, 16, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Yparraguirre, C.D.; Rodríguez Yparraguirre, A.J.; Olivares Espino, I.M.; Maco Vásquez, W.A. Aportes de agricultura de precisión en la productividad sostenible: Una revisión sistemática. RIVAR 2025, 12, 238–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, S.; Guzmán, L. (Eds.) Agricultura Familiar en América Latina y el Caribe: Recomendaciones de Política; Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura: Santiago, Chile, 2014; p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Lowder, S.K.; Sánchez, M.V.; Bertini, R. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Dev. 2021, 142, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Clark, B.; Taylor, J.A.; Kendall, H.; Jones, G.; Li, Z.; Jin, S.; Zhao, C.; Yang, G.; Shuai, C.; et al. A hybrid modelling approach to understanding adoption of precision agriculture technologies in Chinese cropping systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 172, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Maturano, J.; Verhulst, N.; Tur-Cardona, J.; Güereña, D.T.; Gardeazábal-Monsalve, A.; Govaerts, B.; Speelman, S. Understanding Smallholder Farmers’ Intention to Adopt Agricultural Apps: The Role of Mastery Approach and Innovation Hubs in Mexico. Agronomy 2021, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A.B.; Ulina, E.S.; Batubara, S.F.; Chairuman, N.; Sudarmaji; Indrasari, S.D.; Pustika, A.B.; Sutrisna, N.; Surdianto, Y.; Rahmini; et al. Are Indonesian rice farmers ready to adopt precision agricultural technologies? Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 2113–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.L.H.; Halibas, A.; Nguyen, T.Q. Cooperative performance and lead firm support in cleaner production adoption: SEM-fsQCA analysis of precision agriculture acceptance in Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 475, 143724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Chavez, Z.B.; Porcaro, A.; De Simone, M.C.; Guida, D. A Scalable Robotic Approach for Sustainable Viticulture in Developing Regions. In New Technologies, Development and Application VIII; Karabegović, I., Kovačević, A., Mandžuka, S., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1482, pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Chavez, Z.B.; Porcaro, A.; De Simone, M.C.; Guida, D. Improving Sustainable Viticulture in Developing Countries: A Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Arias, J.F.; Branch-Bedoya, J.W.; Arregocés-Guerra, P. OnionFoliageSET: Labeled dataset for small onion and foliage flower crop detection. Data Br. 2024, 55, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazebnyk, L.; Voitenko, V. Digital technologies in agricultural enterprise management. Financ. Credit Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2022, 6, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, R.F.A. An Intelligent Fertilizer Dosing System Using a Random Forest Model for Precision Agriculture. J. Robot. Control 2025, 6, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwadabe, U.M.; Arumugam, N.; Amirah, N.A. An exploratory factor analysis to develop measurement Items for small farmers’ proactiveness and risk-taking in precision farming. Biosci. Res. 2021, 18, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Gwadabe, U.M.; Arumugam, N.; Amirah, N.A. Exploration and Development of Measurement Items of Innovation for New Technology Adoption among Small Farmers. Univers. J. Agric. Res. 2022, 10, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc: London, UK, 2024; p. 552. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2022; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Jukema, G.; Ramaekers, P.; Berkhout, P. De Nederlandse Agrarische Sector in Internationaal Verband: Editie 2023; Number 2023-004; Wageningen Economic Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2023; p. 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, I.; Doh, H.W.; Kim, S.O.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, S.; Lee, S.J. Machine Learning-Based Hourly Frost-Prediction System Optimized for Orchards Using Automatic Weather Station and Digital Camera Image Data. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Monitoring and estimation of late spring frost and its impact on winter wheat through multi-temporal GF-1 remotely sensed imagery. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference Agro-Geoinformatics, Shenzhen, China, 26–29 July 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marote, M.L. Agricultura de precisión. Rev. Cienc. Tecnol. 2010, 10, 143–166. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze, S.R.; Campbell, M.N.; Walley, S.; Pfeiffer, K.; Wilkins, B. Exploration of sub-field microclimates and winter temperatures: Implications for precision agriculture. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2021, 65, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Sun, Q.; Hu, B.; Zhang, S. A Framework for Agricultural Pest and Disease Monitoring Based on Internet-of-Things and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Sensors 2020, 20, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of Remote Sensing in Precision Agriculture: A Review. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, T.; Brandão, T.; Ferreira, J.C. Machine Learning for Detection and Prediction of Crop Diseases and Pests: A Comprehensive Survey. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbers, R.; Adamchuk, V.I. Precision Agriculture and Food Security. Science 2010, 327, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sajwan, A.; Kamboj, A.D.; Joshi, G.; Gautam, R.; Kumar, M.; Mani, G.; Lal, S.; Kaur, J. Advances in precision nutrient management of fruit crops. J. Plant Nutr. 2024, 47, 3251–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Mir, Z.A.; Ali, S. Revisiting the Role of Sensors for Shaping Plant Research: Applications and Future Perspectives. Sensors 2024, 24, 3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Zhao, W.; Ahmad, N.; Zhao, L. Beyond green and red: Unlocking the genetic orchestration of tomato fruit color and pigmentation. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2023, 23, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoorvogel, J.J.; Kooistra, L.; Bouma, J. Managing soil variability at different spatial scales as a basis for precision agriculture. In Soil-Specific Farming: Precision Agriculture; Lal, R., Stewart, B., Eds.; Advances in Soil Science; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, B. Perspectives of Precision Agriculture in Conservation Agriculture. In Conservation Agriculture: Environment, Farmers Experiences, Innovations, Socio-Economy, Policy; García-Torres, L., Benites, J., Martínez-Vilela, A., Holgado-Cabrera, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöneberg, T.; Lewis, M.T.; Burrack, H.J.; Grieshop, M.; Isaacs, R.; Rendon, D.; Rogers, M.; Rothwell, N.; Sial, A.A.; Walton, V.M.; et al. Cultural control of drosophila suzukii in small fruit—Current and pending tactics in the U.S. Insects 2021, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammanpila, H.W.; Sashika, M.A.N.; Priyadarshani, S.V.G.N. Advancing Horticultural Crop Loss Reduction Through Robotic and AI Technologies: Innovations, Applications, and Practical Implications. Adv. Agric. 2024, 2024, 2472111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithiyanantham, K.K.; Venusamy, K.; Ashok, P.; Hussain, M.J.M.; Chitra, S.; Anandaram, H. Crop Health Monitoring for Precision Agriculture Using IoT-Based Sensors in Drones. In Proceedings of International Conference on Recent Innovations in Computing; Illés, Z., Verma, C., Gonçalves, P.J.S., Singh, P.K., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2024; Volume 1195, pp. 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.; Purkaystha, S.; Ghosh, T.; Ghosh, S.C.; Hayat, A. Application of Precision Farming in Horticulture: A Comprehensive Review. J. Sci. Res. Reports 2024, 30, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabato, D.; Esteras, C.; Grillo, O.; Peña-Chocarro, L.; Leida, C.; Ucchesu, M.; Usai, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Picó, B. Molecular and morphological characterisation of the oldest Cucumis melo L. seeds found in the Western Mediterranean Basin. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’hamdi, O.; Takács, S.; Palotás, G.; Ilahy, R.; Helyes, L.; Pék, Z. A Comparative Analysis of XGBoost and Neural Network Models for Predicting Some Tomato Fruit Quality Traits from Environmental and Meteorological Data. Plants 2024, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Perez, C.; Marino, A.; Cameron, I. Learning-Based Tracking of Crop Biophysical Variables and Key Dates Estimation From Fusion of SAR and Optical Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 7444–7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Félix, J.D.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Meirinho, S.; Nunes, A.R.; Alves, G.; Garcia-Viguera, C.; Moreno, D.A.; Silva, L.R. Differential response of blueberry to the application of bacterial inoculants to improve yield, organoleptic qualities and concentration of bioactive compounds. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 278, 127544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullany, M. Biostimulants are Variably Effective at Preserving Field Crop Yield Under Water Stress: A Global Meta-Analysis. SSRN 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, N.; Yu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Y.; Hu, X. Monitoring soil moisture in winter wheat with crop water stress index based on canopy-air temperature time lag effect. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Jin, M.; Tang, Z.; Sun, T.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y. Monitoring Soybean Soil Moisture Content Based on UAV Multispectral and Thermal-Infrared Remote-Sensing Information Fusion. Plants 2024, 13, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, L.; Erin, B.; Z., M.A.; Jason, K. Deep Infiltration Model to Quantify Water Use Efficiency of Center-Pivot Irrigated Alfalfa. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2024, 150, 4024021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, M.A.J.; Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Prospects for crop production under drought: Research priorities and future directions. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2005, 147, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, B.A.; Schroeder, A.; Grimaudo, J. IT as enabler of sustainable farming: An empirical analysis of farmers’ adoption decision of precision agriculture technology. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 54, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura. LEY-18910: Sustituye Ley Organica del Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario, Chile. 1990. Available online: https://www.ecolex.org/es/details/legislation/ley-no-18910-sustituye-ley-organica-del-instituto-de-desarrollo-agropecuario-lex-faoc021998/ (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- INDAP. Requisitos Para ser Usuario/a de Indap. 2023. Available online: http://www.indap.gob.cl/requisitos-para-ser-usuarioa-de-indap (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Muñoz, N.; Sagredo, M.P.; Paredes, M. Organizaciones Campesinas en Chile: Caracterización, Contribuciones y Desafíos; Centro de Políticas Públicas UC, INDAP: Santiago, Chile, 2020; p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Resultados del Censo Nacional Agropecuario y Forestal Revelan Que la Ganadería, Cultivos y Frutales Son Las Principales Fuentes de Ingresos Para Los Productores. 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/sala-de-prensa/prensa/general/noticia/2022/01/20/resultados-del-censo-nacional-agropecuario-y-forestal-revelan-que-la-ganadería-cultivos-y-frutales-son-las-principales-fuentes-de-ingresos-para-los-productores (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Ministerio de Economía Fomento y Turismo. Ministerio de Economía Constituyó Comité de Ministros para el Desarrollo Productivo Sostenible. 2023. Available online: https://www.economia.gob.cl/2023/01/06/ministerio-de-economia-constituyo-comite-de-ministros-para-el-desarrollo-productivo-sostenible.htm (accessed on 31 August 2023).

- Valdés, A.; Foster, W.; Ortega, J.; Pérez, R.; Vargas, G. Desafíos de la Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural en Chile; Technical Report; Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias del Ministerio de Agricultura, Gobierno de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, E.E.; Cabezas, Y.D.R.; Alvear, M.Á. Transformación digital en la comercialización agroempresarial: Oportunidades y desafíos para los pequeños productores. Código Científico Rev. Investig. 2024, 5, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Research Department. Participación de las Actividades Económicas en el PIB de Chile 2022. 2023. Available online: https://es.statista.com/estadisticas/1285944/participacion-de-las-actividades-economicas-en-el-pib-de-chile (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Villalobos, P.; Manriquez, R.; Acevedo, C.; Ortega, S. Alcance de la Agricultura de Precisión en Chile: Estado del Arte, Ámbito de Aplicación y Perspectivas; Technical Report; Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias: Santiago, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lencucha, R.; Pal, N.E.; Appau, A.; Thow, A.M.; Drope, J. Government policy and agricultural production: A scoping review to inform research and policy on healthy agricultural commodities. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apey Guzmán, A.; Barrera Pedraza, D.; Rivas Sius, T. (Eds.) Agricultura Chilena: Reflexiones y Desafíos al 2030, 1st ed.; Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias (ODEPA): Santiago, Chile, 2017; p. 293. [Google Scholar]

- INDAP. Agricultor de Limache Ahorra la Mitad del Agua Gracias a Innovador Sistema de Riego de alta Precisión. 2014. Available online: https://www.indap.gob.cl/noticias/agricultor-de-limache-ahorra-la-mitad-del-agua-gracias-innovador-sistema-de-riego-de-alta (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- INDAP. 114 Pequeños Agricultores de Melipilla Acceden a Tecnología de Punta Gracias a Alianza Público-Privada. 2021. Available online: https://www.indap.gob.cl/noticias/114-pequenos-agricultores-de-melipilla-acceden-tecnologia-de-punta-gracias-alianza-publico (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- INIA Quilamapu. INIA Impulsa Uso Eficiente del Agua de Riego Entre Agricultores Mediante Sistema Smartfield o “Campo Inteligente”. 2025. Available online: https://www.inia.cl/2025/04/20/inia-impulsa-uso-eficiente-del-agua-de-riego-entre-agricultores-mediante-sistema-smartfield-o-campo-inteligente/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Cruzat, R.; Bellolio, C. Resultados y Lecciones en Agricultura de Precisión en Frutales: Proyecto de Innovación en Regiones de O’Higgins y del Maule; Experiencias de Innovación para el Emprendimiento Agrario; Fundación para la Innovación Agraria: Santiago, Chile, 2010; Volume 101, p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Shi, W.; Fang, F.; Guo, J.; Lu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Jiang, X. Exploring the feasibility of sewage treatment by algal–bacterial consortia. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chan, F.K.S.; Thorne, C.; O’donnell, E.; Quagliolo, C.; Comino, E.; Pezzoli, A.; Li, L.; Griffiths, J.; Sang, Y.; et al. Addressing challenges of urban water management in Chinese sponge cities via nature-based solutions. Water 2020, 12, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, R.; Lagos, C.; Viera, E.; Banguera, L.; Millán, G.; Vargas, M.; González, Á. Design, Simulation and Comparison of Controllers that Estimate an Hydric Balance in Strawberry Plantations in San Pedro. In Advances in Emerging Trends and Technologies; Botto-Tobar, M., Leon-Acurio, J., Diaz Cadena, A., Montiel Diaz, P., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1066, pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Dold, C. Water-use efficiency: Advances and challenges in a changing climate. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Chapagain, A.K.; Aldaya, M.M.; Mekonnen, M.M. The Water Footprint Assessment Manual: Setting the Global Standard, 1st ed.; Water Footprint Network: London, UK, 2011; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Özcan, G.; Çelebi, N.G.; Arpacıoğlu, Ü. Portable Irrigation System Producing Water from Air for Sustainable Living: “ECO-WATER-GEN”. J. Arch. Sci. Appl. 2022, 7, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues de Sá Silva, A.C.; Mendonça Bimbato, A.; Perrella Balestieri, J.A.; Nogueira Vilanova, M.R. Exploring environmental, economic and social aspects of rainwater harvesting systems: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Trincado, A.; Duran, C.; Lagos, C.; Parodi, C.; Banguera, L.; Carrasco, R. Identification of critical water stress factors that impact mining: Technical solution. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE CHILEAN Conference on Electrical, Electronics Engineering, Information and Communication Technologies (CHILECON), Valparaiso, Chile, 13–17 November 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Blanco, C.D.; Hrast-Essenfelder, A.; Perry, C. Irrigation Technology and Water Conservation: A Review of the Theory and Evidence. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2020, 14, 216–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, F.J.; Nowak, P. Aspects of Precision Agriculture. In Advances in Agronomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 67, pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODEPA. Caracterización de la Pequeña Agricultura en Chile, Descripción de Sus Necesidades y Sus Subsectores, Evaluación de Los Servicios Prestados por ODEPA a Este Segmento, y Propuestas de Mejoramientos y Nuevos Servicios e Instrumentos Informe; Technical Report; Oficina de Estudios y Políticas Agrarias: Santiago, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Chile 2022; OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, M.C.A.; Guereña, A. Land Inequality Trends and Drivers. Land 2020, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olabanji, M.F.; Chitakira, M. The Adoption and Scaling of Climate-Smart Agriculture Innovation by Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: A Review of Institutional Mechanisms, Policy Frameworks and Market Dynamics. World 2025, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, G.S.; Chauke, H. Challenges and opportunities in smallholder agriculture digitization in South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1583224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendov, N.M.; Varas, S.; Zeng, M. Digital Technologies: In Agriculture and Rural Areas; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberger, M.; Shacham-Diamand, Y.; Krishnan, S.; Sapur, S.; Dodiya, M.; Bhadaliya, P.; Fishman, R. The Challenges of Using Remote Sensing Based Irrigation Recommendation Technology on Smallholder Farms in India. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 2nd Conference on AgriFood Electronics (CAFE), Xanthi, Greece, 26–28 September 2024; pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, C.M.; Nyaga, J.M.; Wetterlind, J.; Söderström, M.; Piikki, K. Precision Agriculture for Resource Use Efficiency in Smallholder Farming Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaya, T.K.; Kiwa, F.J.; Hapanyengwi, G.; Murungweni, C. AI—Driven Decision Support System for Optimizing Soil Analysis and Crop Management in Zimbabwe. In Proceedings of the 2024 3rd Zimbabwe Conference of Information and Communication Technologies (ZCICT), Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, 28–29 November 2024; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law 18910. Sustituye Ley Orgánica del Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario; Government of Chile: Santiago, Chile, 1990.

- Puntel, L.A.; Bolfe, É.L.; Melchiori, R.J.M.; Ortega, R.; Tiscornia, G.; Roel, A.; Scaramuzza, F.; Best, S.; Berger, A.G.; Hansel, D.S.S.; et al. How digital is agriculture in a subset of countries from South America? Adoption and limitations. Crop Pasture Sci. 2022, 74, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Gutiérrez, Á.V.; Méndez-Morales, A.; Herrera, M.M. Barreras a la innovación: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Trilogía Cienc. Tecnol. Soc. 2023, 15, e2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture 2021—Systems at Breaking Point. Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; p. 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, R.; Gómez, D.; Barrantes, L. Enhancing agricultural value chains through technology adoption: A case study in the horticultural sector of a developing country. Agric. Food Secur. 2023, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adasme-Berríos, C.; Valdes, R.; Roco, L.; Gómez, D.; Carvajal, E.; Herrera, C.; Espinoza, J.; Rivera, K. Segmentation of Consumer Preferences for Vegetables Produced in Areas Depressed by Drought. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muharomah, R.; Setiawan, B.I.; Sands, G.R.; Juliana, I.C.; Gunawan, T.A. A review on enhancing water productivities adaptive to the climate change. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2025, 16, 860–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Economics of Water Scarcity and Efficiency. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackfort, S. Patterns of Inequalities in Digital Agriculture: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, R.; Ashraf, S.; Javeed, H.M.R.; ur Rehman, A.; Yaseen, M.; Khan, B.A.; Abbas, T.; Saeed, F.; Ali, M. Regenerative Organic Farming for Encouraging Innovation and Improvement of Environmental, Social, and Economic Sustainability. In Regenerative Agriculture for Sustainable Food Systems; Kumar, S., Meena, R.S., Sheoran, P., Jhariya, M.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 175–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpou, A.; Arvaniti, O.; Afratis, N.; Zahariadis, T. Sustainability challenges in the bovine sector and the implementation of waste management policies within the EU framework. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 9, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugganig, M. Fixing sustainability through technoscience and diversity: The case of EU agriculture policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 171, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailova, M.; Tsvyatkova, D.; Kabadzhova, M.; Atanasova, S. Micro and small farms—Element from the model for revitalizing of rural areas. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 28, 959–971. [Google Scholar]

- Tawse-Garcia, C.; Valdez, R.; Gustine, R.; Tracy, E.E.; Larsen, W.; Auerbach, D.; Pertuzé V., M.; Mukerji, R.; Fremier, A.; Warner, B.; et al. “To Irrigate or Not?” Is the Wrong Question: Exploring the Triple Bottom Line of Climate Adaptation for Dairy Farmers in Los Lagos, Chile. Case Stud. Environ. 2025, 9, 2470531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Silva, R.; Castillo, M. Droughts, Drought Mitigation Policy and Income Concentration Among Agricultural Producers. The Case of Chile. Water Econ. Policy 2025, 2550007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba, D.; Flores-Fernández, C.; Carrasco, R. Análisis bibliométrico y de contenido sobre VUCA. Rev. Española Doc. Científica 2023, 46, e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso; Observatorío Laboral Valparaíso. Necesidades de Adaptación en la Fuerza Laboral del Sector Agrícola; Technical Report; Subsecretaría del Trabajo, Gobierno de Chile: Valparaíso, Chile, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, P.; Bai, A.; Czibere, I.; Kovách, I.; Fodor, L.; Bujdos, Á.; Sulyok, D.; Gabnai, Z.; Birkner, Z. Economic and Social Barriers of Precision Farming in Hungary. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Clark, B.; Li, W.; Jin, S.; Jones, G.D.; Chen, J.; Taylor, J.; Li, Z.; Frewer, L.J. Precision agriculture technology adoption: A qualitative study of small-scale commercial “family farms” located in the North China Plain. Precis. Agric. 2021, 23, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).