Abstract

This study aims to compare the transcriptional responses of japonica and indica rice genotypes with contrasting submergence tolerance and to functionally validate the role of OsEXPB3. Flooding is a major abiotic stress limiting stable rice production, and different genotypes show substantial variation in submergence tolerance. However, the transcriptional and molecular regulatory mechanisms underlying subspecies-specific responses remain poorly understood. Here, RNA-seq analysis of japonica and indica accessions with contrasting tolerance levels was performed to construct molecular response networks and identify key tolerance-related genes. Comparative analysis revealed that both subspecies activate biological processes such as stimulus response, redox homeostasis, carbon metabolism, and hormone signaling under submergence. In the analyzed japonica genotypes, plants relied more on integrated hormone-regulated signaling, whereas in the analyzed indica genotypes, metabolic homeostasis was more prominent. Among the identified genes, OsEXPB3, a β-expansin gene, was consistently upregulated in tolerant accessions, whereas osexpb3 mutants displayed suppressed coleoptile and seedling elongation and reduced tolerance. Hormone profiling revealed a 0.1–0.3-fold increase in ethylene (ETH) and a 50–70% reduction in gibberellin (GA) in mutants after submergence. Defense-related hormones, including jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA), were initially higher but declined markedly under stress conditions. Given that the OsEXPB3 promoter contains multiple ETH-, GA-, ABA-, JA- and SA-responsive cis-elements, we propose that OsEXPB3 may coordinate the balance between growth- and defense-related hormones to mediate adaptive responses to flooding. This study reveals conserved and divergent molecular responses between subspecies and suggests that OsEXPB3 may contribute to submergence tolerance in rice, although its regulatory role requires further validation.

1. Introduction

Flooding is among the most severe natural hazards worldwide, and the resulting submergence stress often leads to inhibited rice growth, reduced yield, or even large-scale crop failure, posing a serious threat to global food security [1,2]. It is estimated that approximately 15% of global arable land is affected by flooding to varying degrees, with Southeast and South Asia being the most severely impacted regions [3]. Between 2020 and 2023 alone, due to extreme rainfall and abnormal monsoon patterns, more than 12 million hectares of major rice-growing areas—including the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in China, as well as Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, and Thailand—were submerged, resulting in a reduction of over eight million tons in rice production and direct economic losses exceeding 3.5 billion USD [3,4]. Therefore, identifying and utilizing submergence-tolerant germplasm for rice genetic improvement, as well as elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying their adaptive responses to submergence, holds significant theoretical and practical value.

Submergence stress disrupts gas exchange within plant tissues, resulting in oxygen (O2) deprivation and limited carbon dioxide (CO2) diffusion, which collectively inhibit photosynthesis, suppress energy metabolism, and reduce the efficiency of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis [5,6]. To adapt to the submergence stress, rice has evolved diverse adaptive strategies through long-term evolution and natural selection [7]. For instance, the formation of adventitious roots and aerenchyma enhances O2 acquisition and transport [8,9]; the “quiescence strategy,” characterized by growth suppression during submergence and rapid recovery after removal of submergence, helps conserve energy and improve survival [10,11]; in contrast, the “escape strategy,” which promotes rapid internode elongation to keep leaf tips above the water surface, facilitates gas exchange under deepwater conditions [12,13].

Plant hormone signals and crosstalk play pivotal roles in regulating these adaptive strategies under submergence [14,15]. When plants are submerged, restricted gas diffusion leads to the rapid accumulation of ETH, which in turn activates group VII ethylene response factor (ERF-VII) transcription factors that initiate defense responses related to energy metabolism and hormonal balance [16]. Enhanced ETH signaling can induce the expression of GA biosynthetic genes to promote stem elongation, whereas ABA suppresses GA synthesis to maintain growth inhibition and energy conservation. Thus, the interplay among ETH, GA, and ABA is crucial in determining whether rice adopts an “escape” or “quiescence” strategy [17]. For example, Submergence 1 (Sub1A) suppresses plant elongation by inhibiting ETH–GA signaling interactions to conserve energy [10,18], whereas SNORKEL1/2 (SK1/2) promotes internode elongation through GA activation [19]. These two genotypes represent major regulators of submergence tolerance: Sub1A is primarily found in certain indica varieties, while SK1/2 genes are typical of deepwater rice [19]. In recent years, with advances in mutant screening, whole-genome sequencing, and transcriptomic analysis, several additional submergence-related genes involved in hormonal regulation have been identified, such as ABA 8′-Hydroxylase (OsABA8ox1) [20], GENERAL REGULATORY FACTOR14h (OsGF14h) [7], and Trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (OsTPP7) [21]. However, most existing studies focus on single genes or isolated hormonal pathways and are often limited to individual genotypes. Comparative and integrative analyses across japonica and indica subspecies remain scarce, particularly regarding how hormonal regulatory networks interface with cell wall remodeling processes and expansin-family genes—key components potentially linking hormone signaling to structural adaptation under submergence.

The expansin (EXP) gene family is considered an essential molecular bridge linking growth regulation and stress adaptation. Expansin proteins loosen the cellulose–hemicellulose network in the plant cell wall, thereby facilitating cell elongation, and they play critical roles in both plant development and abiotic stress responses [22,23]. Based on structural characteristics and functional differentials, the expansin family can be divided into four major subfamilies: α-expansin (EXPA), β-expansin (EXPB), expansin-like A (EXLA), and expansin-like B (EXLB) [24]. Among them, EXPB proteins are mainly involved in cell wall loosening in rapidly elongating tissues such as roots and internodes, and several members have been shown to interact closely with hormonal signaling pathways [25,26]. Previous studies reported that OsEXPB3, OsEXPB4, OsEXPB6, and OsEXPB11 are upregulated under submergence or GA treatment [27]. However, comparative transcriptome analysis across japonica and indica genotypes revealed that OsEXPB3 was the only EXPB member consistently and strongly upregulated in all four tolerant accessions, whereas other EXPB genes displayed weaker, genotype- dependent, or inconsistent expression patterns. In addition, the subspecies-dependent expression patterns and hormone-regulatory characteristics of OsEXPB3, as well as their relationship to submergence tolerance, remain insufficiently understood, further highlighting the need to investigate this gene as a priority candidate within the EXPB family.

In this study, four submergence-tolerant rice accessions—Funuo3 (FN3), Huikenuo1701 (HKN1701), Minghui63 (MH63), and Diantun502 (DT502)—and two submergence-intolerant accessions—Longgeng968 (LG968) and Fengbazhan (FBZ) were used as experimental materials [28]. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that (i) japonica and indica rice exhibit both conserved and divergent transcriptional responses under submergence, (ii) tolerant genotypes share a set of co-expressed DEGs that contribute to metabolic reprogramming and hormonal adjustment, and (iii) OsEXPB3 may act as a regulatory component within hormone-mediated submergence adaptation. To test these hypotheses, RNA-seq analysis was performed to systematically compare the transcriptional responses of the six genotypes under submergence stress. Several candidate tolerance-related genes were identified, among which OsEXPB3 was prioritized due to its strong and consistent upregulation in tolerant accessions and the presence of multiple hormone-responsive cis-elements in its promoter region. Through genetic and physiological analyses, we explored the potential role and regulatory mechanisms of OsEXPB3 in submergence adaptation. Our results revealed that OsEXPB3 plays a crucial role in the submergence response of rice, potentially through modulating hormone homeostasis to balance growth and stress adaptation. This study not only elucidates the hormonal regulatory mechanisms underlying submergence tolerance mediated by OsEXPB3 but also provides a key molecular target and theoretical foundation for enhancing rice submergence tolerance through hormone-based regulatory strategies, offering valuable insights for molecular design breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The experimental materials used in this study consisted of six rice accessions exhibiting distinct differences in submergence tolerance, including four tolerant type (T-type) accessions—FN3, HKN1701, MH63, and DT502—and two intolerant type (I-type) accessions—LG968 and FBZ [28]. For the convenience of subsequent analyses and consistent reference, the six accessions were uniformly designated according to their submergence tolerance levels: FN3, HKN1701, MH63, and DT502 were renamed as Tolerant 1 (T1), T2, T3, and T4, respectively, while LG968 and FBZ were designated as Intolerant 1 (I1) and I2. Among them, T1, T2, and I1 belong to the japonica subspecies, while T3, T4, and I2 are indica types. For each germplasm, more than 300 plump and healthy seeds were selected, surface-sterilized with 1.5% NaClO (Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and rinsed thoroughly with sterile water. The seeds were then soaked for 2 d in darkness at 37 °C to promote imbibition, followed by germination and conventional seedling cultivation in the field. After 30 d of growth, 100 uniform, healthy seedlings were selected and transplanted individually into 100 planting holes at a spacing of 15 cm between plants and 20 cm between rows. All materials were grown in the experimental field of Anhui University of Science and Technology (Fengyang County, Chuzhou City, Anhui Province, China, 117°33′15″ E, 32°52′30″ N). These six germplasms were observed throughout the entire growth period. Mature seeds were collected 45 d after heading, air-dried, and used for subsequent experiments.

2.2. Submergence Stress Treatments and Sample Collection

For each of the six rice germplasms, 600 plump and healthy seeds were selected and equally divided into two groups: the control group (CK) and the submergence treatment group (S), resulting in 12 groups in total: T1-CK, T1-S, T2-CK, T2-S, I1-CK, I1-S, T3-CK, T3-S, T4-CK, T4-S, I2-CK, and I2-S (Table S1). Each group included three independent biological replicates, yielding a total of 36 samples (Table S1). Each biological replicate consisted of a pooled sample of 30 seedlings, which were harvested and combined to represent one biological sample. Seeds were surface-sterilized with 1.5% NaClO solution (Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), rinsed thoroughly with sterile water, and soaked for 2 d in darkness at 37 °C. After germination, the seeds were sown in pots (top diameter 70 mm, bottom diameter 50 mm, height 70 mm) filled with 50 mm of soil and covered uniformly with a 5 mm layer of fine sand. The pots were then placed in glass cylinders (diameter 100 mm, height 350 mm) with the initial water level just reaching the seed surface. All samples were incubated in a plant growth chamber under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 25 °C. Water in the cylinders was not renewed during the treatment to maintain stable submergence conditions. After 5 d, the water level for the submergence (Sub) groups was gradually raised to 15 cm above the seed surface, which exceeded the height of the seedlings at this stage, ensuring full submergence. The water level was maintained constant throughout the treatment, while the CK were kept at the original shallow-water condition. After 7 d of submergence treatment, the aboveground tissues of seedlings from each germplasm were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction and gene expression analyses.

2.3. RNA-Seq Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from rice tissues using the Total RNA Extractor (Trizol) kit (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and qualified samples were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China) for cDNA library construction and sequencing using the Illumina platform. Each treatment group included three independent biological replicates, and one cDNA library was constructed and sequenced for each replicate, resulting in a total of 36 biological libraries. No technical replicates were used for sequencing. Raw reads obtained from sequencing were first evaluated for quality using FastQC v0.11.9 (Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK) [29], and adapter sequences and low-quality reads were removed using Trimmomatic to obtain high-quality clean reads. The clean reads were aligned to the rice reference genome IRGSP-1.0 using HISAT2 v2.2.1 (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) [30], and mapping efficiency was evaluated. Read depth per library averaged 47.4 million clean reads, with detailed statistics provided in Table S3. To ensure data reliability, alignment integrity, and uniformity were evaluated using RSeQC v4.0.0 (Python Package, Developed by Wang Lab, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and Qualimap v2.3 (Centro de Regulación Genómica, Barcelona, Spain) [31]. Gene expression levels were quantified using StringTie (Pertea Lab, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) [32] and GffCompare (Pertea Lab, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA) [33] to generate both raw read counts and TPM values. Importantly, DESeq2 was applied exclusively to raw count data for differential expression analysis [34], with |log2FoldChange| ≥ 1 and adjusted p ≤ 0.05 used as the significance thresholds. TPM values were used only for visualization and comparative assessment of relative expression levels, rather than for statistical testing. Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed using the clusterProfiler R package v4.10.0 (Yu Lab, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China)to identify enriched Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [35,36].

2.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Approximately 1 g of rice tissue was used for total RNA extraction with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was verified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and RNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). One microgram of high-quality RNA was treated with MonScript™ RTIII All-in-One Mix with dsDNase (Monad Biotech, Suzhou, China) to remove genomic DNA and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Importantly, the same biological RNA samples used for RNA-seq were also used for qRT-PCR validation to ensure consistency and strengthen the reliability of expression verification. The rice OsActin-1 gene (LOC_Os03g50885) was employed as an internal control. Specific primers for OsActin-1 and target genes were designed based on their coding sequences (CDS) (Table S2). PCR reactions were performed using MonScript™ ChemoHS Specificity Plus qPCR Mix (Low ROX) (Monad Biotech, Suzhou, China) on an ABI ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The thermal cycling program was as follows: 95 °C for 30 s; followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Each sample was analyzed with three biological replicates. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [37].

2.5. Phylogenetic, Gene Structure, and Promoter Cis-Element Analyses of the OsEXPB Gene Family

Protein sequences of the EXPB gene family from Arabidopsis thaliana were used as queries to search against the Oryza sativa protein database using BlastP with an E-value threshold of ≤1 × 10−5. Candidate sequences were further validated for the presence of EXPB-specific domains (PF03330 and PF01357) using PfamScan based on Hidden Markov Models (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/pfa/pfamscan (accessed on 13 June 2025)), and conserved domains were confirmed using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi (accessed on 18 June 2025)). A total of 18 OsEXPB gene were identified, which is fully consistent with previously published EXPB family annotations in rice [24]. Multiple sequence alignments of the 18 OsEXPB protein sequences were performed using the “Align by ClustalW” module in MEGA 11 software with default parameters [38]. Based on the alignment, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Neighbor-Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates, and evolutionary distances were calculated using the Poisson correction model. The exon–intron structures of OsEXPB genes were visualized using GSDS 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/ (accessed on 27 June 2025)). The 2.0 kb upstream sequences from the translational start site (ATG) of each OsEXPB gene were extracted and used as promoter regions. Only non-overlapping upstream intergenic regions were retained when adjacent genes were present. Cis-acting elements were identified using PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ (accessed on 7 July 2025)), and their distribution was visualized with TBtools-II v2.337 (South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China) [39].

2.6. Gene Editing and Analysis of OsEXPB3

The mutant lines used in this study were developed in the genetic background of Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica cv. Zhonghua 11 (ZH11). The OsEXPB3 (LOC_Os10g40720) knockout mutants, osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2, were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system by Biogle Gene Technology Co., Ltd. (Changzhou, China). Two specific single guide RNA (sgRNA) target sites were designed within the first exon of OsEXPB3 using the online tool CRISPR-P 2.0 (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR2/ (accessed on 29 May 2025)), and the sgRNA fragments were cloned into the BGK032 CRISPR/Cas9 vector according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The validated construct was introduced into ZH11 calli via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Transformed calli were selected on hygromycin-containing medium, and PCR-positive plantlets were sequenced to confirm the mutation types. After self-pollination, homozygous lines were identified through genotyping. To ensure the genetic stability of the edited materials, we performed PCR-based detection of the CRISPR/Cas9 cassette in both osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2 lines, and no Cas9 sequence was detected in the homozygous mutant plants used in this study. In addition, basic off-target prediction and verification were conducted for the top-ranked potential off-target sites based on sgRNA sequence similarity, and no off-target mutations were identified in the examined loci. The homozygous seeds were used for subsequent submergence treatments, physiological measurements, and molecular analyses.

2.7. Determination of Endogenous Hormone Levels in Wild-Type and osexpb3 Mutants

Submergence stress treatments were conducted as described in Section 2.2. After 7 d of submergence, the aboveground tissues of rice seedlings were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Hormone measurements were outsourced to Nanjing Ruiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Briefly, approximately 1 g of fresh seedling tissue was homogenized in cold methanol–water (80:20, v/v) containing isotopically labeled internal standards. After overnight extraction at 4 °C, samples were centrifuged, purified using C18 solid-phase extraction, and filtered through 0.22 µm membranes. Quantification of endogenous hormones—including 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), ABA, JA, Methyl salicylate (MeSA), Trans-zeatin (tZ), and several gibberellins (GA1, GA3, GA4)—was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS/MS; triple-quadrupole system) operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode. Hormone levels were calculated based on internal-standard normalization.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10.4.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA), IBM SPSS Statistics 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and Origin 2024 software (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). For phenotypic measurements, each treatment included three independent biological replicates, with 30 seedlings per replicate (n = 3). Hormone quantification was conducted using three biological replicates (n = 3), and qPCR analysis was performed using three biological replicates with three technical replicates each (n = 3 × 3). Significant differences between treatments were determined by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Figures and graphical visualizations were generated using Adobe Photoshop 2024 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), Adobe Illustrator 2024 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), TBtools-II v2.337 (South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China) [39], and RStudio (v4.4.2.).

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of DEGs in Japonica and Indica Rice in Response to Submergence Stress

Given the substantial genetic divergence between the indica and japonica subspecies of rice, independent RNA-seq and comparative analyses were conducted for two sub species. After rigorous quality control and alignment, the sequencing data exhibited high Q30 scores and mapping rates (>92%), with no evidence of adapter contamination or base composition bias, indicating that the data quality was sufficient for subsequent differential analyses (Table S3). Based on this, gene expression levels in each treatment group were normalized using the Transcripts Per Million (TPM) method. The results revealed significant differences in both baseline expression and regulation amplitude between japonica and indica rice. Specifically, the average log2 (TPM) values of japonica samples ranged from −5 to 5 (Figure S1A), whereas those of indica samples were primarily distributed between −15 and 5 (Figure S1B), suggesting that low-expression genes were more prevalent in the indica population. In total, 30,050 expressed genes were detected in japonica rice under control and submergence conditions, of which 28,674 were co-expressed (Figure S1C). For indica rice, 27,468 expressed genes were identified, including 25,937 co-expressed genes (Figure S1D).

Further DEG analysis of japonica and indica genotypes in response to submergence stress revealed that in japonica, the tolerant genotype T1-S compared with its control T1-CK exhibited 1899 upregulated and 898 downregulated genes, while the intolerant genotype I1-S vs. I1-CK showed 3228 upregulated and 3358 downregulated genes (Figure S1E). Cross-genotype comparison between the two tolerant japonica accessions (T1-S vs. T2-S) identified only 1188 upregulated and 645 downregulated DEGs (Figure S1E), indicating that tolerant japonica accessions displayed relatively fewer transcriptional changes under submergence stress.

In indica rice, the tolerant genotype T3-S vs. T3-CK exhibited merely 384 upregulated and 571 downregulated genes (Figure S1F), whereas the intolerant genotype I2-S vs. I2-CK showed 2347 upregulated and 1900 downregulated genes. Comparisons between tolerant indica accessions (T3-S vs. T4-S) detected 1060 upregulated and 901 downregulated genes, while comparisons between tolerant and intolerant accessions (T3-S vs. I2-S, T4-S vs. I2-S) revealed 977/973 and 724/858 DEGs, respectively (Figure S1F). Although the overall DEG numbers within indica were lower than those observed in japonica, such differences may partly reflect baseline expression levels, statistical thresholds, or variations in dynamic transcriptional responsiveness. Therefore, rather than indicating a strictly “more conserved mechanism,” these results suggest that the analyzed indica genotypes may engage a more moderate or constrained transcriptional reprogramming under submergence, compared to the broader transcriptional shifts observed in the analyzed japonica genotypes.

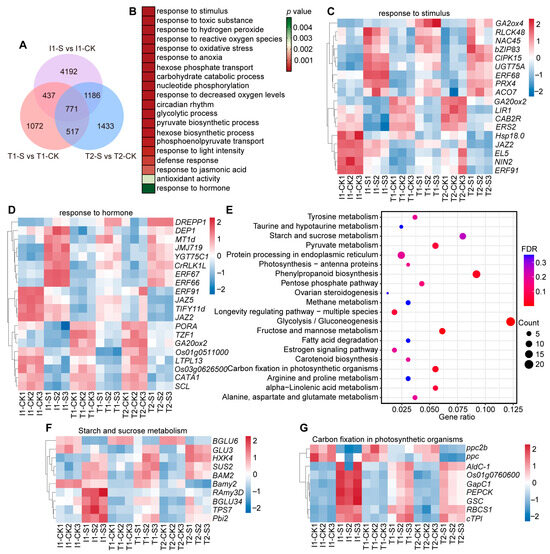

3.2. Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis of DEGs in Japonica Rice

Cross-analysis of DEGs identified among the three japonica rice accessions revealed 771 co-differentially expressed genes (co-DEGs) (Figure 1A). GO enrichment analysis indicated that japonica rice responds to submergence stress primarily through processes such as response to stimulus, response to oxidative stress, carbohydrate catabolic process, and response to hormone (Figure 1B). Within the stimulus-response module, several key genes were identified, including Receptor-Like Cytoplasmic Kinases (RLCK48) involved in regulating mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades [40], the bZIP transcription factor (bZIP83) associated with ABA signaling [41], the LIGHT-INDUCED RICE1 (LIR1) receptor protein mediating ETH responses [42], and the class II small heat shock protein 18.0 (Hsp18.0) [43] that maintains protein homeostasis (Figure 1C). Furthermore, hormone regulatory network analysis revealed a multi-pathway crosstalk hub composed of several key genes, including gibberellin 2-oxidase (GA2ox2) [12], UDP-glucosyltransferase (UGT75A) [44], CBL-interacting protein kinase 15, (OsCIPK15) [45], jasmonate ZIM-domain protein (JAZ2) [46], and group VII ethylene response factor (ERF67) [47], which are involved in the biosynthesis and regulation of GA, ABA, JA, and ETH (Figure 1D). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that the 771 DEGs were mainly enriched in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and carbohydrate metabolism pathways (Figure 1E). To further investigate the expression dynamics of these metabolic genes, heatmaps were generated for DEGs enriched in starch and sucrose metabolism and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms’ pathways. Most DEGs exhibited upregulated expression under submergence treatment, though their expression levels differed significantly between tolerant and intolerant japonica accessions (Figure 1F,G, p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Functional annotation, enrichment analysis, and expression profiles of co-DEGs in japonica rice. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs between tolerant (T) and intolerant (I) japonica accessions under control (CK) and submergence (Sub) treatments; (B) GO enrichment analysis of 771 japonica co-DEGs, where color intensity represents the significance level (p value); (C,D) Heatmaps showing the expression patterns of DEGs enriched in stimulus-response (C) and hormone-response (D) pathways; (E) KEGG enrichment analysis of 771 japonica co-DEGs, with dot size indicating the number of DEGs and color intensity representing the FDR value; (F,G) Heatmaps showing DEGs involved in starch and sucrose metabolism (F) and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (G). T, submergence-tolerant accession; I, submergence-intolerant accession; CK, control treatment; S (Sub), 7 d of submergence.

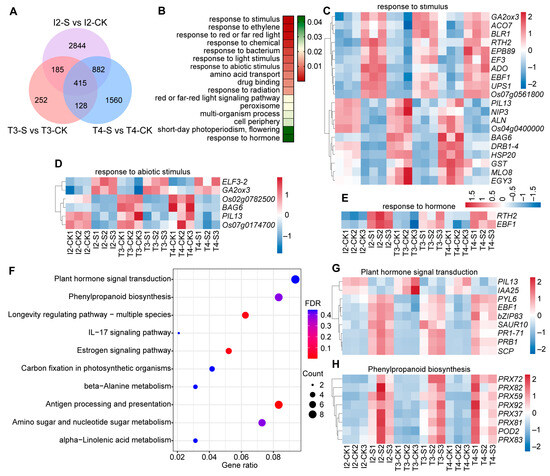

3.3. Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis of DEGs in Indica Rice

Similarly, a cross-group comparative analysis of DEGs among the three indica rice accessions identified 415 co-DEGs (Figure 2A). These 415 co-DEGs were mainly enriched in pathways related to response to stimulus, response to abiotic stimulus, and response to hormone (Figure 2B). Within the stimulus-response module, a transmembrane signal transduction network was established, consisting of the aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase (ACO7) gene encoding a rate-limiting enzyme in ethylene biosynthesis [48], the phytochrome-interacting bHLH factors-LIKE (PIL13) gene regulating hypocotyl elongation [49], and the type II glutathione S-transferase (GSTU1) gene functioning as a key component of the antioxidative defense system [50] (Figure 2C). Further analysis revealed that the early flowering gene (ELF3-2) [51], a circadian rhythm regulator, and the gibberellin catabolic enzyme gene GA2ox3 [52] were specifically activated in the response to abiotic stimulus pathway following submergence (Figure 2D). Additionally, within the hormone response pathway, only two genes were significantly enriched—Reversion-To-ethylene Sensitivity1 (RTH2) [53], which modulates ethylene sensitivity, and EIN3-binding F-box protein 1 (EBF1) [54], a positive regulator of ethylene biosynthesis. Both genes exhibited higher expression levels in submergence-intolerant accessions compared to tolerant ones (Figure 2E). This limited scale of hormonal regulation stands in sharp contrast to the multi-pathway crosstalk network observed in japonica rice.

Figure 2.

Functional annotation, enrichment analysis, and expression profiles of co-DEGs in indica rice. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of DEGs between tolerant (T) and intolerant (I) indica accessions under control (CK) and submergence (Sub) treatments; (B) GO enrichment analysis of 415 indica co-DEGs, with color intensity indicating p value; (C–E) Heatmaps showing expression levels of co-DEGs enriched in stimulus-response (C), abiotic stimulus-response (D), and hormone-response (E) pathways; (F) KEGG enrichment analysis of 415 indica co-DEGs, where dot size represents the number of DEGs and color depth indicates the FDR value; (G,H) Heatmaps of co-DEGs enriched in plant hormone signal transduction (G) and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (H) pathways. T, submergence-tolerant accession; I, submergence-intolerant accession; CK, control treatment; S (Sub), 7 d of submergence.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the 415 co-DEGs revealed that nine genes were enriched in the plant hormone signal transduction pathway (Figure 2F). These included the early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene (OsIAA25) [55], the ABA receptor gene pyrabactin resistance-like abscisic acid receptor (OsPYL6) [56], and the small auxin-up RNA gene (OsSAUR10) [57], which promotes auxin biosynthesis and polar transport (Figure 2F,G). The second most enriched pathway was phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (eight genes), primarily involving members of the class III peroxidase (PRX) gene family that play essential roles in osmotic stress tolerance (Figure 2F,H) [58]. Further expression profiling showed that most co-DEGs were upregulated under submergence stress, though their expression levels differed significantly between submergence-tolerant and -intolerant indica accessions (Figure 2G,H).

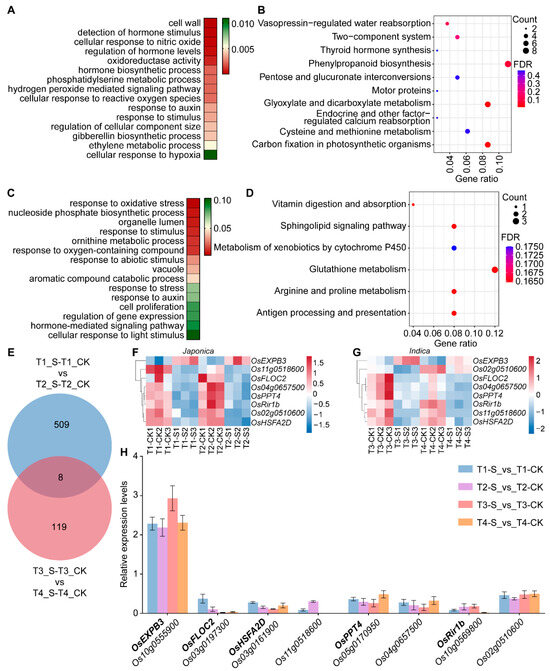

3.4. Identification and Expression Analysis of Candidate Genes for Submergence Tolerance

Analysis of DEGs in T-type japonica and T-type indica rice accessions revealed that submergence stress induced 517 genes uniquely responsive in T-type japonica and 128 genes specifically responsive in T-type indica (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). Among these, the 517 co-DEGs identified in japonica accessions were mainly involved in biological processes such as cell wall organization, hormone biosynthetic process, cellular response to reactive oxygen species, and ethylene metabolic process (Figure 3A). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis further showed that these genes were significantly enriched in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway (nine genes), followed by glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms, each enriched with seven genes (Figure 3B). In contrast, the 128 co-DEGs identified in T-type indica accessions were predominantly associated with response to oxidative stress, response to stimulus, and hormone-mediated signaling pathways (Figure 3C). KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that these 128 co-DEGs were significantly enriched in six KEGG pathways, including glutathione metabolism, antigen processing and presentation, and arginine and proline metabolism (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Analysis and expression validation of candidate submergence-responsive genes. (A) GO enrichment analysis of 517 DEGs expressed exclusively in tolerant (T-type) japonica accessions, with color intensity representing p value; (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of the same 517 DEGs, with dot size indicating the number of DEGs and color intensity representing FDR; (C) GO enrichment analysis of 128 DEGs expressed exclusively in tolerant (T-type) indica accessions; (D) KEGG enrichment analysis of these 128 DEGs, with dot size representing the number of DEGs and color intensity representing FDR; (E) Venn diagram showing the overlap between the 517 japonica-specific and 128 indica-specific DEGs; (F,G) Heatmaps showing expression levels of eight co-DEGs identified in tolerant japonica (F) and indica (G) accessions; (H) Relative expression analysis of eight cross-subspecies candidate genes, with error bars indicating standard errors. T, submergence-tolerant accession; I, submergence-intolerant accession; CK, control treatment; S (Sub), 7 d of submergence.

A cross-comparison between the 517 japonica-specific and 128 indica-specific co-DEGs identified eight co-differentially expressed genes shared between submergence-tolerant japonica and indica accessions (Figure 3E). These included β-expansin (OsEXPB3, Os10g0555900), FLO2-interacting cupin domain protein 1 (OsFLOC2, Os03g0197300), heat shock transcription factor (OsHSFA2D, Os03g0161900), PHOSPHOENOLPYRUVATE/PHOSPHATE TRANSLOCATOR 4 (OsPPT4, Os05g0170950), and Rice Immunity Repressor 1 (OsRir1b, Os10g0569800), among others (Figure 3E; Table S4). Gene expression heatmap analysis showed that OsEXPB3 was upregulated under submergence stress, while the other seven genes exhibited downregulated expression patterns (Figure 3F,G). This trend was further validated by qRT-PCR analysis (Figure 3H). OsEXPB3, a member of the expansin gene family, facilitates cell wall loosening and cell elongation, and its expression is induced by both submergence stress and GA treatment [27,59]. This characteristic aligns well with the typical adaptive strategy of rice under submergence stress—rapid stem elongation to rise above the water surface and restore gas exchange. Therefore, OsEXPB3 is likely involved in submergence tolerance in rice.

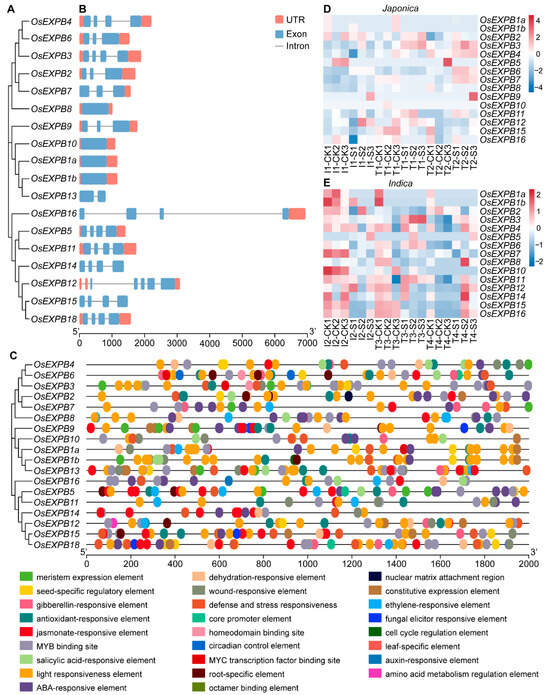

3.5. Gene Structure and Promoter Cis-Element Analysis of OsEXPB Genes

Through whole-genome sequence alignment and domain validation, a total of 18 family members containing complete EXPB domains were identified in the rice genome. To further investigate the evolutionary characteristics and structural conservation of OsEXPB3 and its family members, a phylogenetic analysis was conducted. The results revealed that the 18 members of the rice OsEXPB gene family could be classified into several relatively stable clades, with genes within each clade exhibiting highly consistent exon–intron structures (Figure 4A,B). Most members contained two or more exons, while OsEXPB8, OsEXPB10, OsEXPB1a, and OsEXPB1b were composed of a single exon. In contrast, certain members such as OsEXPB16 displayed evident structural variation (Figure 4B). Cis-acting element analysis indicated that OsEXPB family members were generally enriched in hormone- and stress-responsive elements, suggesting that they are coordinately regulated by multiple signaling pathways (Figure 4C). Notably, the promoter region of OsEXPB3 contains a relatively high density of hormone-responsive cis-elements, including at least thirteen canonical motifs such as four ETH-responsive, four GA-responsive, two ABA-responsive, one SA-responsive, and two JA-associated (MYC and wound-responsive) elements, along with additional environmental response elements related to light, circadian rhythm, and oxidative stress. These findings imply that OsEXPB3 may mediate rice adaptation to submergence stress through the integration of hormone and environmental signaling pathways (Figure 4C). To further validate this hypothesis, we examined the expression patterns of OsEXPB family members under submergence stress. The results showed that submergence generally induced the expression of multiple OsEXPB genes, though the magnitude of induction varied markedly among subfamily members and between subspecies (Figure 4D,E). Among them, OsEXPB3 exhibited a consistently strong and stable upregulation in both submergence-tolerant japonica and indica accessions, whereas no comparable pattern was observed for other family members. While several members are responsive to submergence, the unique and robust upregulation of OsEXPB3 indicates that it may play a primary or specialized role in the submergence response, rather than functioning redundantly with other family members. This finding indicated that OsEXPB3 plays a conserved and pivotal role in regulating submergence tolerance in rice (Figure 4D,E). These features collectively suggest that OsEXPB3 possesses substantial regulatory potential in mediating rice responses to submergence stress.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, and promoter cis-acting element analysis of the OsEXPB gene family. (A,B) Phylogenetic tree (A) and exon–intron organization (B) of OsEXPB genes. UTR, untranslated region; exon, coding exon; intron, noncoding intron. (C) Cis-acting regulatory elements identified in the promoters of OsEXPB genes. (D,E) Expression patterns of the 18 OsEXPB family members in japonica (D) and indica (E) rice accessions. T, submergence-tolerant accession; I, submergence-intolerant accession; CK, control treatment; S (Sub), 7 d of submergence.

3.6. Comparison of Submergence Tolerance Between Wild-Type and osexpb3 Mutants

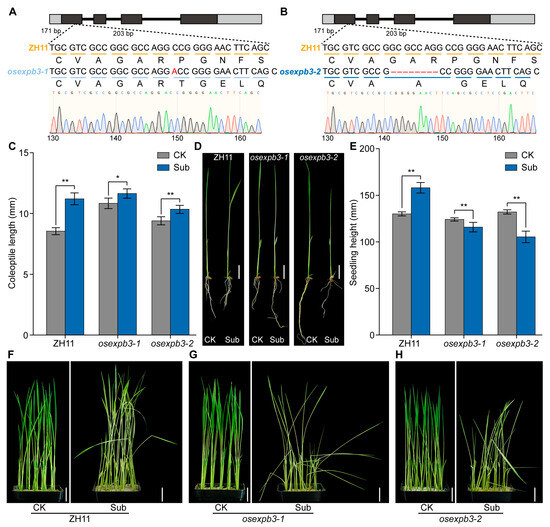

To further elucidate the role of OsEXPB3 in rice responses to submergence stress, two independent mutant lines, osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2, were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system. Sequence alignment of genomic DNA and CDS revealed that osexpb3-1 harbors a single-base insertion (“A”) in the first exon, whereas osexpb3-2 carries an 8 bp deletion in the same exon. Both mutations resulted in frameshifts, thereby disrupting the function of OsEXPB3 (Figure 5A,B and Figure S2). Wild-type (ZH11) and mutant seedlings were subjected to submergence treatment for 7 d. The results showed that submergence stress significantly promoted coleoptile elongation in all genotypes; however, the elongation extent in ZH11 was markedly greater than that in osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2 (Figure 5A,B, p < 0.05). Similarly, submergence induced a significant increase in overall seedling height in ZH11, consistent with a typical “escape” strategy, whereas both osexpb3 mutants exhibited substantially reduced elongation, with osexpb3-2 showing the most pronounced decrease (Figure 5C, p < 0.05). Moreover, wild-type plants displayed prominent stem elongation after submergence, whereas both osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2 showed limited stem elongation (Figure 5D–F). Collectively, these results indicate that submergence stress strongly promotes coleoptile and seedling elongation in wild-type rice, while this response is compromised in osexpb3 mutants, suggesting that OsEXPB3 plays an important role in regulating rice growth response under submergence stress. Based on these results, we further performed a comprehensive analysis of endogenous hormone contents in wild-type and mutant plants under both control and 7 d submergence conditions to elucidate the regulatory mechanism of OsEXPB3 during submergence stress.

Figure 5.

Generation of osexpb3 mutants and phenotypic differences under submergence stress. (A,B) Mutation sites in osexpb3-1 (A) and osexpb3-2 (B) mutants. Inserted or deleted nucleotides are marked in red. Black boxes indicate exons, light gray boxes represent untranslated regions (UTRs), and thick black lines denote introns. (C) Comparison of coleoptile lengths under control and submergence conditions. (D) Changes in coleoptile lengths under different treatments. (E) Comparison of seedling heights under control and submergence conditions. (F–H) Whole-plant morphology of ZH11 (F), osexpb3-1 (G), and osexpb3-2 (H) after 7 d of submergence. CK, control treatment; Sub, 7 d of submergence; Student’s t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01). scale bar = 2 cm.

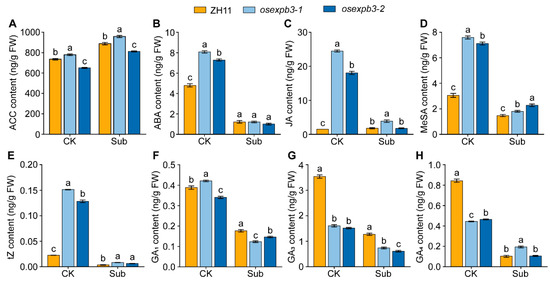

3.7. Comparison of Hormone Levels Between the Wild Type and osexpb3 Mutants

Submergence stress generally promoted the accumulation of ACC, a precursor of ethylene biosynthesis [60]. Among the tested genotypes, osexpb3-1 maintained relatively higher ACC levels under both control and submergence conditions, whereas osexpb3-2 exhibited lower levels, suggesting that differences may exist in the ethylene-related regulatory pathways between the two mutants (Figure 6A). Both osexpb3 mutants showed higher concentrations than ZH11 under control conditions, but their ABA levels markedly declined and converged after submergence, indicating that ABA biosynthesis was suppressed by submergence stress (Figure 6B). The defense-related hormones JA and methyl salicylate (MeSA) were initially present at higher concentrations in the mutants but decreased significantly following submergence treatment (Figure 6C,D). Similarly, the trans-zeatin (tZ) was elevated in the mutants under control conditions yet declined sharply after submergence, suggesting that submergence stress inhibited cytokinin biosynthesis or accumulation (Figure 6E). Furthermore, GAs, including GA1, GA3, and GA4, were consistently higher in the wild type but significantly reduced in both mutants. This reduction was further intensified under submergence, implying that both OsEXPB3 disruption and submergence stress negatively affect GA biosynthesis or metabolism (Figure 6F–H). Overall, both osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2 displayed disturbed hormonal homeostasis even under normal growth conditions, characterized by elevated levels of defense- and signaling-related hormones (ETH, JA, SA, and cytokinin (CTK)) and a marked decrease in growth-promoting GAs. Submergence stress further influenced this hormonal balance, leading to a general decline in defense-related hormones, while the synthesis of growth-regulating hormones such as GA and ABA was also inhibited (Figure 6). Collectively, based on the 7-day time-course results, the mutants appear to suggest a potential role for OsEXPB3 in coordinating the balance between growth and defense under submergence stress.

Figure 6.

Changes in ethylene precursor and multiple hormone contents in wild-type and osexpb3 mutants under control and submergence treatments. (A–H) Contents of the ethylene precursor ACC (A), ABA (B), JA (C), MeSA (D), tZ (E), GA1 (F), GA3 (G), and GA4 (H). The materials analyzed included the ZH11 and mutants osexpb3-1 and osexpb3-2. CK, control treatment; Sub, 7 d of submergence. Bars represent means ± SE (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among genotypes under the same treatment at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA, Duncan’s multiple range test).

4. Discussion

Submergence stress is one of the major abiotic constraints limiting rice production, severely affecting plant growth, development, and yield formation. A clear understanding of the molecular and hormonal mechanisms underlying rice adaptation to submergence is essential for revealing tolerance formation and guiding molecular breeding. In this study, through comparative transcriptomic analyses of submergence-tolerant and submergence-intolerant rice genotypes, combined with functional validation of osexpb3 mutants, we reveal the pivotal role of OsEXPB3 in regulating rice submergence adaptation and maintaining hormonal homeostasis.

Comparative analyses of the transcriptional responses of the submergence-tolerant rice accessions analyzed in this study under submergence stress revealed that the regulatory networks underlying submergence tolerance exhibit both conserved and accession-specific features. Among the genotypes examined, multiple common metabolic and stress-response pathways were activated under submergence. In the analyzed japonica accessions, 771 co-DEGs and in the analyzed indica accessions, 415 co-DEGs were significantly enriched in glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, phenylpropanoid metabolism, and carbohydrate metabolism pathways (Figure 1E and Figure 2F), suggesting that these genotypes maintain energy supply under hypoxic conditions through enhanced anaerobic respiration and carbon metabolic reprogramming. Our study also identified multiple known metabolic or signaling regulators associated with submergence-tolerant phenotypes. For instance, OsCIPK15 participates in sugar signaling regulation (Figure 1C) [61], whereas the OsTPP7 modulates starch metabolism to promote germination and coleoptile elongation, thereby enhancing growth adaptability under hypoxia [62]. These findings highlight the importance of sugar metabolism in the analyzed genotypes’ responses to submergence stress, consistent with short-term hypoxia adaptation strategies recognized in other angiosperms [63,64].

Among the analyzed accessions, apparent differences in response strategies and molecular emphases were observed. In the analyzed japonica accessions, multi-hormone signaling networks, involving GA, ABA, ETH, and JA, to maintain a dynamic balance between growth and energy homeostasis (Figure 1D). Similar multi-hormone regulatory patterns have been observed in other plant species adapting to submergence; for example, in deepwater rice and certain lowland rice varieties, ETH accumulation triggers ABA degradation and activates GA signaling to promote internode elongation, while JA coordinates energy metabolism and defense responses [12,15,19]. This is consistent with the early-phase submergence response model, in which ETH suppresses ABA signaling by regulating OsABA8ox1 expression while promoting GA biosynthesis, enabling multi-hormone-mediated coordination of internode elongation [20]. In contrast, the analyzed indica accessions tend to rely more heavily on metabolic homeostasis and antioxidant systems to maintain energy balance. Specific upregulation of amino acid metabolism and glutathione-related genes may serve as a metabolic buffering mechanism against submergence stress, representing a relatively “hormone-independent” adaptation strategy (Figure 2). However, this apparent independence from hormonal signaling is not universal across all indica varieties; for instance, the submergence-tolerance gene Sub1A in indica exerts its effect by modulating the interaction between ETH and GA signaling, significantly enhancing submergence tolerance [10,65]. In summary, within the genotypes analyzed, japonica accessions tend to achieve a balance between growth and energy conservation through integrated hormone and signaling regulation, whereas indica accessions primarily rely on metabolic plasticity and antioxidant capacity to maintain homeostasis. Despite these differences in response strategies, the genotypes analyzed share a common regulatory foundation underlying submergence tolerance, while also exhibiting pronounced accession-specific rather than subspecies-wide divergence.

OsEXPB3 belongs to the β-expansin gene family and may indirectly influence tissue sensitivity and utilization efficiency of growth-promoting hormones such as GA by regulating cell elongation processes [59]. Cross-subspecies transcriptome comparisons revealed that OsEXPB3 is significantly upregulated in multiple submergence-tolerant accessions. Its upstream promoter region is enriched with various hormone-responsive cis-elements, including those responsive to ETH, GA, ABA, JA, and SA, suggesting that this gene may participate in feedback regulation of hormone metabolism and signaling, thereby mediating adaptive responses to submergence stress (Figure 3F–H and Figure 4C–E). Although promoter-wide polymorphism was not analyzed in this study, potential differences in cis-element composition between japonica and indica may partly contribute to the accession-specific expression patterns of OsEXPB3. Under submergence, osexpb3 mutants exhibited suppressed coleoptile and seedling elongation, while the resulting weaker growth responses suggest compromised adaptation rather than directly demonstrating reduced tolerance (Figure 5). Compared with the wild type, GA levels in osexpb3 mutants were significantly lower under control conditions and declined even further under submergence, indicating a sustained reduction in GA-mediated growth promotion. In contrast, defense-related hormones such as JA and SA were higher in mutants under control conditions but decreased markedly after submergence (Figure 6). This hormone pattern suggests—though does not prove—that osexpb3 mutations may disrupt the dynamic balance between growth-promoting and defense-related hormones, potentially affecting growth recovery capacity under stress. Taken together, we propose a working model in which OsEXPB3 may influence transcriptional regulation of hormone biosynthesis and metabolism genes and modulate GA-mediated elongation responses by altering cellular signaling sensitivity or tissue growth characteristics. This model integrates experimental observations with reasonable inferences but remains speculative and will require further functional validation.

Cross-subspecies RNA-seq comparisons indicated that japonica rice exhibited a higher number of DEGs and broader pathway coverage than indica rice (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure S1). Moreover, in submergence-tolerant indica accessions, a greater proportion of DEGs were associated with metabolic and defense pathways, including phenylpropanoid metabolism, carbon metabolism, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. In contrast, japonica rice displayed stronger regulatory features in hormone signaling pathways, particularly in genes related to ETH, ABA, and GA (Figure 1 and Figure 2). These results indicate that japonica and indica rice exhibit different gene expression and submergence response patterns, likely arising from evolutionary divergence in genome structure and domestication history, leading to different submergence adaptation strategies [66,67,68]. At the level of specific regulatory modules, japonica rice contains OsMPK3-associated signaling modules (Figure 1C), reflecting its long-term directional domestication under artificial selection [69]. Additionally, a co-expression module comprising ERF91 and JAZ2 coordinates ETH and JA signaling in japonica, maintaining a dynamic balance between defense activation and growth suppression (Figure 1C). In contrast, submergence tolerance in indica appears to be more driven by environmental rhythm and metabolic feedback (Figure 2C–E). Significant transcriptional differences were observed between tolerant and intolerant japonica accessions (T1-S vs. I1-S: 5523 DEGs; T2-S vs. I1-S: 5256 DEGs) (Figure S1E), whereas indica exhibited relatively fewer differences (T3-S vs. I2-S: 1950 DEGs; T4-S vs. I2-S: 1582 DEGs) (Figure S1F), suggesting that japonica mounts a more dramatic transcriptional response involving complex regulatory networks and polygenic micro-effect interactions. Given these patterns, we propose that indica tolerance may rely primarily on a few key regulatory factors rather than a broad, highly interconnected network. For example, the core regulator Sub1A enhances submergence tolerance in indica by mediating interactions between ETH and GA signaling, forming a relatively streamlined and efficient regulatory system [70]. However, our dataset—based on a single time point, one tissue type, and a limited number of genotypes—places inherent constraints on drawing broad generalizations about subspecies-level network complexity. Thus, the “simplest network in indica” interpretation remains a tentative proposal requiring validation in future multi-time point and multi-genotype studies.

In the shared submergence response of both subspecies, OsEXPB3 was consistently upregulated in tolerant japonica and indica accessions. Other candidate genes, such as OsHSFA2D, OsRir1b, OsFLOC2, and OsPPT4, displayed substantial differences in expression patterns (Figure 3F–H), further reflecting subspecies-specific variations in stress signaling responses. Consequently, breeding strategies for improving submergence tolerance should account for subspecies-specific traits. In indica, genetic improvement may require a focus on energy metabolism and cell wall/secondary metabolism pathways. In japonica, fine-tuning hormone sensitivity and ETH–GA interaction signaling may be more critical. Notably, OsEXPB3 exhibits stable upregulation in tolerant accessions of both subspecies and correlates with submergence-tolerant phenotypes (Figure 3H), indicating its potential as a cross-subspecies candidate target. Nevertheless, its functional effects may be influenced by background genotypes and trait interactions, and further genetic and molecular validation is required to assess its applicability and stability across diverse genetic backgrounds. Moreover, before proposing OsEXPB3 as a practical breeding target, several limitations should be recognized. Its effects have not yet been tested in elite or high-yield breeding backgrounds, potential trade-offs on agronomic traits such as plant height or lodging resistance remain unknown, and its contribution to submergence tolerance requires confirmation under field or semi-field conditions. Addressing these next steps will be essential for fully evaluating the translational potential of OsEXPB3 in rice improvement.

5. Conclusions

RNA-seq analysis revealed that japonica and indica accessions in this study exhibit distinct submergence response patterns, with japonica relying more on coordinated hormone signaling and indica emphasizing metabolic and redox homeostasis. Conserved response pathways—carbohydrate metabolism, energy supply, and redox regulation—were observed across the genotypes, while OsEXPB3 emerged as a central co-DEG consistently upregulated in tolerant accessions of both groups. Loss-of-function osexpb3 mutants displayed markedly reduced coleoptile and seedling elongation and altered hormone profiles under submergence, which suggests that OsEXPB3 is associated with maintaining the growth–defense balance during stress. Together, these results suggest that OsEXPB3 is a promising candidate for further exploration as a cross-subspecies target to enhance submergence tolerance, although its utility must be validated across elite genetic backgrounds, multiple tissues and time points, and under field conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242556/s1, Table S1: Rice germplasm and RNA-seq sample information used in this study; Table S2: Primers for validating the expression levels of eight candidate submergence-tolerance genes; Table S3: Transcriptomic data profiling and quality assessment; Table S4: Summary of eight co-degs shared by submergence-tolerant japonica and indica rice accessions; Figure S1: Gene expression profiling based on RNA-seq data; Figure S2: Amino acid sequence alignment of ZH11 and osexpb3 mutants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. (Xinyu Huang) and T.F.; Investigation, S.L., Z.S., L.L., X.H. (Xinyu Huang), B.S. and Y.G.; Methodology, S.L., H.F. and M.L.; Software, S.L. and D.X.; validation, H.A.; formal analysis, S.L., L.L. and X.H. (Xinyu Huang); resources, X.H. (Xianzhong Huang), T.F. and S.L.; data curation, S.L. and T.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, T.F. and X.H. (Xianzhong Huang); visualization, S.L., T.F. and X.H. (Xianzhong Huang); supervision, X.H. (Xianzhong Huang) and T.F.; project administration, X.H. (Xianzhong Huang) and T.F.; funding acquisition, X.H. (Xianzhong Huang) and T.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Peak Discipline Construction Funds for Crop Science of Anhui Science and Technology University (XK-XJGF001), the Excellent Scientific Research and Innovation Team of the Education Department of Anhui Province (2022AH010087), the Key Project of Anhui Provincial Education Department (2023AH051886), the Science and technology innovation team of Anhui Sciences and Technology University (2023KJCXTD001), the Talent Introduction Start-up Fund Project of Anhui Science and Technology University (NXYJ202202), and the College Students’ Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Programs (202410879002, 202510879032).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ETH | Ethylene |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| ACC | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid |

| MeSA | Methyl salicylate |

| tZ | Trans-zeatin |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| EXP | Expansin |

| T-type | Tolerant type |

| I-type | Intolerant type |

| CK | Control group |

| Sub | Submergence |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| CDS | Coding sequences |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time PCR |

References

- Chan, F.K.S.; Paszkowski, A.; Wang, Z.L.; Lu, X.H.; Mitchell, G.; Tran, D.D.; Warner, J.; Li, J.F.; Chen, Y.D.; Li, N.; et al. Building resilience in Asian mega-deltas. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.L.; Chen, Y.; Jägermeyr, J.; Cao, J.; Luo, Y.C.; Cheng, F.; Zhuang, H.M.; Wu, H.Q.; et al. Threat of low-frequency high-intensity floods to global cropland and crop yields. Nat. Sustain. 2024, 7, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Impact of Disasters on Agriculture and Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/fao-flagship-publications/the-impact-of-disasters-on-agriculture-and-food-security/en (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Impact of Flooding-Disaster on Agricultural Production; IRRI: Los Baños, Philippines, 2024; Available online: https://www.irri.org (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Winkel, A.; Colmer, T.D..; Ismail, A.M.; Pedersen, O. Internal aeration of paddy field rice (Oryza sativa) during complete submergence---importance of light and floodwater O2. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 1193–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renziehausen, T.; Frings, S.; Schmidt-Schippers, R. ‘Against all floods’: Plant adaptation to flooding stress and combined abiotic stresses. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1836–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Z.; Kong, X.; Yu, X.; Gui, R.; Han, Y.; Li, Z.; Lang, H.; Hua, Y.; et al. Regain flood adaptation in rice through a 14-3-3 protein OsGF14h. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Nakazono, M. Modeling-based age-dependent analysis reveals the net patterns of ethylene-dependent and -independent aerenchyma formation in rice and maize roots. Plant Sci. 2022, 321, 111340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso, M.A.; Borowsky, A.T.; Pauluzzi, G.C.; Yeung, E.; Zhang, J.; Formentin, E.; Velasco, J.; Cabanlit, S.; Duvenjian, C.; Prior, M.J.; et al. Gene regulatory networks shape developmental plasticity of root cell types under water extremes in rice. Dev. Cell 2022, 57, 1177–1192.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xu, X.; Fukao, T.; Canlas, P.; Maghirang-Rodriguez, R.; Heuer, S.; Ismail, A.M.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Ronald, P.C.; Mackill, D.J. Sub1A is an ethylene-response-factor-like gene that confers submergence tolerance to rice. Nature 2006, 442, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, W.; Anumalla, M.; Ismail, A.M.; Walia, H.; Singh, V.K.; Kohli, A.; Bhosale, S.; Bhardwaj, H. Revisiting FR13A for submergence tolerance: Beyond the SUB1A gene. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 5477–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroha, T.; Nagai, K.; Gamuyao, R.; Wang, D.R.; Furuta, T.; Nakamori, M.; Kitaoka, T.; Adachi, K.; Minami, A.; Mori, Y.; et al. Ethylene-gibberellin signaling underlies adaptation of rice to periodic flooding. Science 2018, 361, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, K.; Mori, Y.; Ishikawa, S.; Furuta, T.; Gamuyao, R.; Niimi, Y.; Hobo, T.; Fukuda, M.; Kojima, M.; Takebayashi, Y.; et al. Antagonistic regulation of the gibberellic acid response during stem growth in rice. Nature 2020, 584, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.; Ravindran, P.; Kumar, P.P. Plant hormone-mediated regulation of stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waadt, R.; Seller, C.A.; Hsu, P.K.; Takahashi, Y.; Munemasa, S.; Schroeder, J.I. Plant hormone regulation of abiotic stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Bailey-Serres, J. Flood adaptive traits and processes: An overview. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukao, T.; Bailey-Serres, J. Submergence tolerance conferred by Sub1A is mediated by SLR1 and SLRL1 restriction of gibberellin responses in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16814–16819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dang, T.M.; Singh, N.; Ruzicic, S.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Baumann, U.; Heuer, S. Allelic variants of OsSUB1A cause differential expression of transcription factor genes in response to submergence in rice. Rice 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Nagai, K.; Furukawa, S.; Song, X.J.; Kawano, R.; Sakakibara, H.; Wu, J.; Matsumoto, T.; Yoshimura, A.; Kitano, H.; et al. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature 2009, 460, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saika, H.; Okamoto, M.; Miyoshi, K.; Kushiro, T.; Shinoda, S.; Jikumaru, Y.; Fujimoto, M.; Arikawa, T.; Takahashi, H.; Ando, M.; et al. Ethylene promotes submergence-induced expression of OsABA8ox1, a gene that encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylase in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, T.; Pelayo, M.A.; Trijatmiko, K.R.; Gabunada, L.F.; Alam, R.; Jimenez, R.; Mendioro, M.S.; Slamet-Loedin, I.H.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Bailey-Serres, J.; et al. A trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase enhances anaerobic germination tolerance in rice. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Diffuse Growth of Plant Cell Walls. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasileiro, A.C.M.; Lacorte, C.; Pereira, B.M.; Oliveira, T.N.; Ferreira, D.S.; Mota, A.P.Z.; Saraiva, M.A.P.; Araujo, A.C.G.; Silva, L.P.; Guimaraes, P.M. Ectopic expression of an expansin-like B gene from wild Arachis enhances tolerance to both abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant J. 2021, 107, 1681–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, J.; Lin, N.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Yao, W.; Li, Y. Origin, Evolution, and Diversification of the Expansin Family in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Microbial Expansins. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Mei, J.; Liu, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, Y. Rice Homeobox Protein KNAT7 Integrates the Pathways Regulating Cell Expansion and Wall Stiffness. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Voesenek, L.A. Flooding stress: Acclimations and genetic diversity. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Q.; Ai, H.; Duan, S.M.; Li, R.N.; Owusu, E.A.; Lv, L.L.; Sun, Z.L.; Xu, D.C.; Zhang, M.Z.; Zhou, A.F.; et al. Integrated analysis of laboratory and field experiments to screen rice germplasm for submergence tolerance across various growth stages. Field Crops Res. 2026, 336, 110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sena Brandine, G.; Smith, A.D. Falco: High-speed FastQC emulation for quality control of sequencing data. F1000Research 2019, 8, 1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, N.; Dhillon, B. RNA-seq Data Analysis for Differential Expression. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2391, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Li, W. RSeQC: Quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2184–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, G.; Pertea, M. GFF Utilities: GffRead and GffCompare. F1000Research 2020, 9, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Sato, Y.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids. Res. 2012, 40, D109–D114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Qu, Y.; Wu, C.H.; Vijay-Shanker, K. Automatic gene annotation using GO terms from cellular component domain. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, S.; Giri, J.; Dansana, P.K.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K. The receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase (OsRLCK) gene family in rice: Organization, phylogenetic relationship, and expression during development and stress. Mol. Plant 2008, 1, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijhawan, A.; Jain, M.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Genomic survey and gene expression analysis of the basic leucine zipper transcription factor family in rice. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Hu, H.; Ren, H.; Kong, Y.; Lin, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Ding, X.; Grabsztunowicz, M.; et al. LIGHT-INDUCED RICE1 Regulates Light-Dependent Attachment of LEAF-TYPE FERREDOXIN-NADP+ OXIDOREDUCTASE to the Thylakoid Membrane in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.S.; Rajendran, S.K.; Liu, Y.H.; Wu, S.J.; Lu, C.A.; Yeh, C.H. Overexpression of OsHsp 18.0 in rice enhanced tolerance to heavy metal stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1841–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Z.; Peng, L.; Huang, C.; Tang, Z.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Z. UDP-glucosyltransferase OsUGT75A promotes submergence tolerance during rice seed germination. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, N.H.; Wang, F.Z.; Shi, L.; Chen, M.X.; Cao, Y.Y.; Zhu, F.Y.; Wu, Y.Z.; Xie, L.J.; Liu, T.Y.; Su, Z.Z.; et al. Natural variation in the promoter of rice calcineurin B-like protein10 (OsCBL10) affects flooding tolerance during seed germination among rice subspecies. Plant J. 2018, 94, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Du, H.; Tang, N.; Li, X.; Xiong, L. Identification and expression profiling analysis of TIFY family genes involved in stress and phytohormone responses in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.Y.; Zeng, C.Y.; Shih, M.C. Group VII ethylene response factors forming distinct regulatory loops mediate submergence responses. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 1745–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, T.; Miyasaka, A.; Seo, S.; Ohashi, Y. Contribution of ethylene biosynthesis for resistance to blast fungus infection in young rice plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1202–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todaka, D.; Nakashima, K.; Maruyama, K.; Kidokoro, S.; Osakabe, Y.; Ito, Y.; Matsukura, S.; Fujita, Y.; Yoshiwara, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; et al. Rice phytochrome-interacting factor-like protein OsPIL1 functions as a key regulator of internode elongation and induces a morphological response to drought stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15947–15952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ban, Y.; Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Feng, Z. Toxicity and Glutathione S-Transferase-Catalyzed Metabolism of R-/S-Metolachlor in Rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 25001–25014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, R.; Fan, J.; Park, C.H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Ouyang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, G.L. OsELF3-2, an Ortholog of Arabidopsis ELF3, Interacts with the E3 Ligase APIP6 and Negatively Regulates Immunity against Magnaporthe oryzae in Rice. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 1679–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Gao, S.; Liu, L.; Yin, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qian, Q.; Chu, C. Brassinosteroid regulates cell elongation by modulating gibberellin metabolism in rice. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4376–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Yang, X.; Shi, Z.; Miao, X. Novel crosstalk between ethylene- and jasmonic acid-pathway responses to a piercing-sucking insect in rice. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhong, W.; Zhou, S.; Li, Z.; An, H.; Liu, X.; Wu, R.; Bohora, S.; Wu, Y.; et al. A viral protein orchestrates rice ethylene signaling to coordinate viral infection and insect vector-mediated transmission. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Kaur, N.; Garg, R.; Thakur, J.K.; Tyagi, A.K.; Khurana, J.P. Structure and expression analysis of early auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene family in rice (Oryza sativa). Funct. Integr. Genom. 2006, 6, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Lv, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Niu, H.; Bu, Q. Characterization and Functional Analysis of Pyrabactin Resistance-Like Abscisic Acid Receptor Family in Rice. Rice 2015, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhai, L.; Li, N.; Yan, H. The Small Auxin-Up RNA SAUR10 Is Involved in the Promotion of Seedling Growth in Rice. Plants 2023, 12, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognolli, M.; Penel, C.; Greppin, H.; Simon, P. Analysis and expression of the class III peroxidase large gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 2002, 288, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, D. Biochemical properties and localization of the beta-expansin OsEXPB3 in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Cells 2005, 20, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polko, J.K.; Kieber, J.J. 1-Aminocyclopropane 1-Carboxylic Acid and Its Emerging Role as an Ethylene-Independent Growth Regulator. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, H.K.; Lim, M.N.; Lee, S.E.; Lim, J.; Lee, Y.; Hwang, Y.S. Hexokinase-mediated sugar signaling controls expression of the calcineurin B-like interacting protein kinase 15 gene and is perturbed by oxidative phosphorylation inhibition. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Lv, J.; Tang, C.; Wang, N.; Liang, Z.; Li, H.; Xiang, J.; et al. Identification and Regulation of Hypoxia-Tolerant and Germination-Related Genes in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, A.; Yano, K.; Gamuyao, R.; Nagai, K.; Kuroha, T.; Ayano, M.; Nakamori, M.; Koike, M.; Kondo, Y.; Niimi, Y.; et al. Time-Course Transcriptomics Analysis Reveals Key Responses of Submerged Deepwater Rice to Flooding. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 3081–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreti, E.; Perata, P. The Many Facets of Hypoxia in Plants. Plants 2020, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.C.; Lee, W.J.; Zeng, C.Y.; Chou, M.Y.; Lin, T.J.; Lin, C.S.; Ho, M.C.; Shih, M.C. SUB1A-1 anchors a regulatory cascade for epigenetic and transcriptional controls of submergence tolerance in rice. Pnas Nexus 2023, 2, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Xia, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, K. Comparative proteomic analysis of indica and japonica rice varieties. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2014, 37, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mickelbart, M.V.; Hasegawa, P.M.; Bailey-Serres, J. Genetic mechanisms of abiotic stress tolerance that translate to crop yield stability. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; He, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, M.; Chen, W.; Luo, L.; Luo, L.; et al. Genome evolution and diversity of wild and cultivated rice species. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sinha, A.K. A Positive Feedback Loop Governed by SUB1A1 Interaction with MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE3 Imparts Submergence Tolerance in Rice. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 1127–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.M.; Barding, G.A., Jr.; Sathnur, S.; Larive, C.K.; Bailey-Serres, J. Rice SUB1A constrains remodelling of the transcriptome and metabolome during submergence to facilitate post-submergence recovery. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).