Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding Lines and Registered Varieties Using Multi-Temporal UAV Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

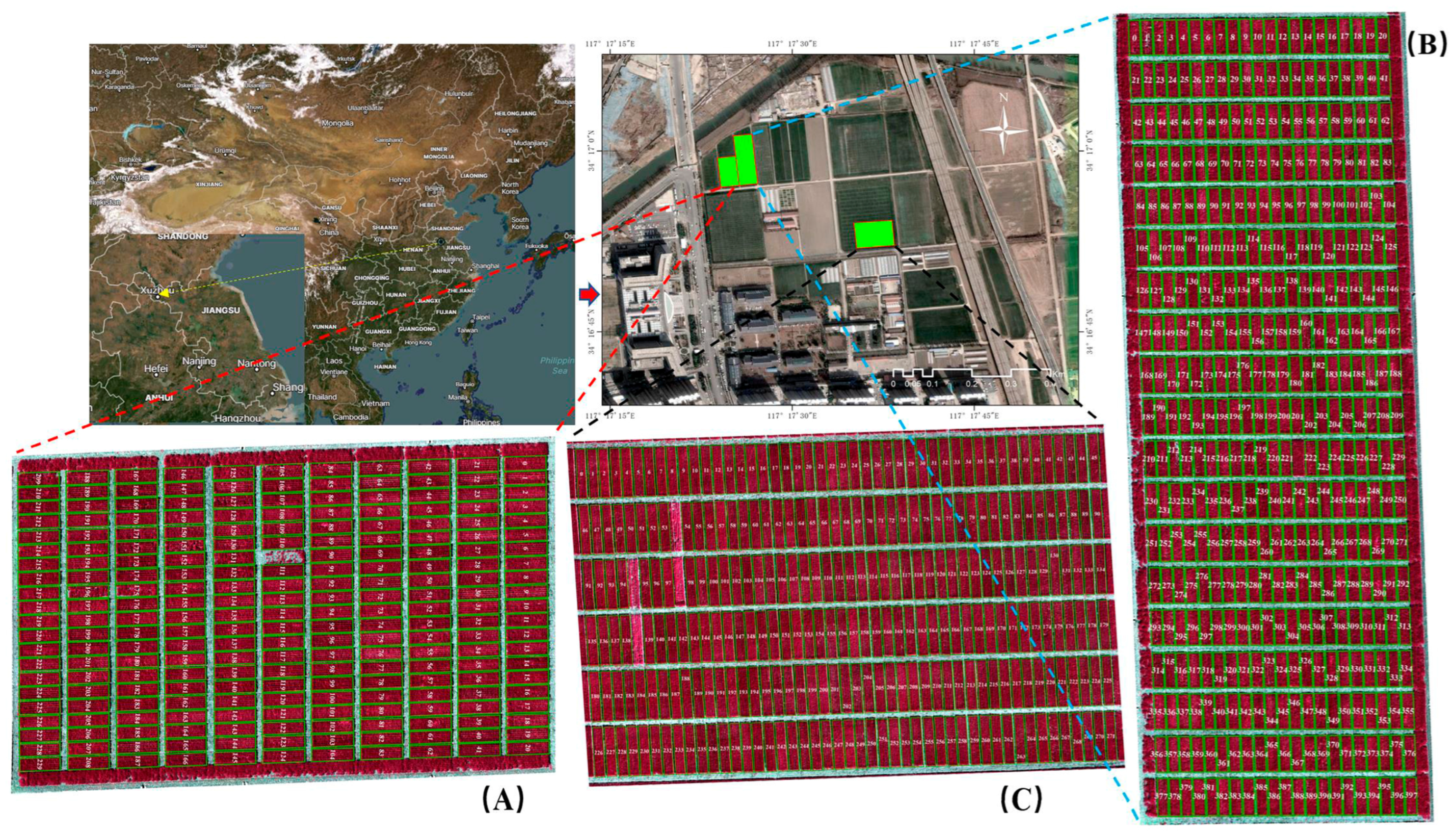

2.1. Study Region Experimental Design

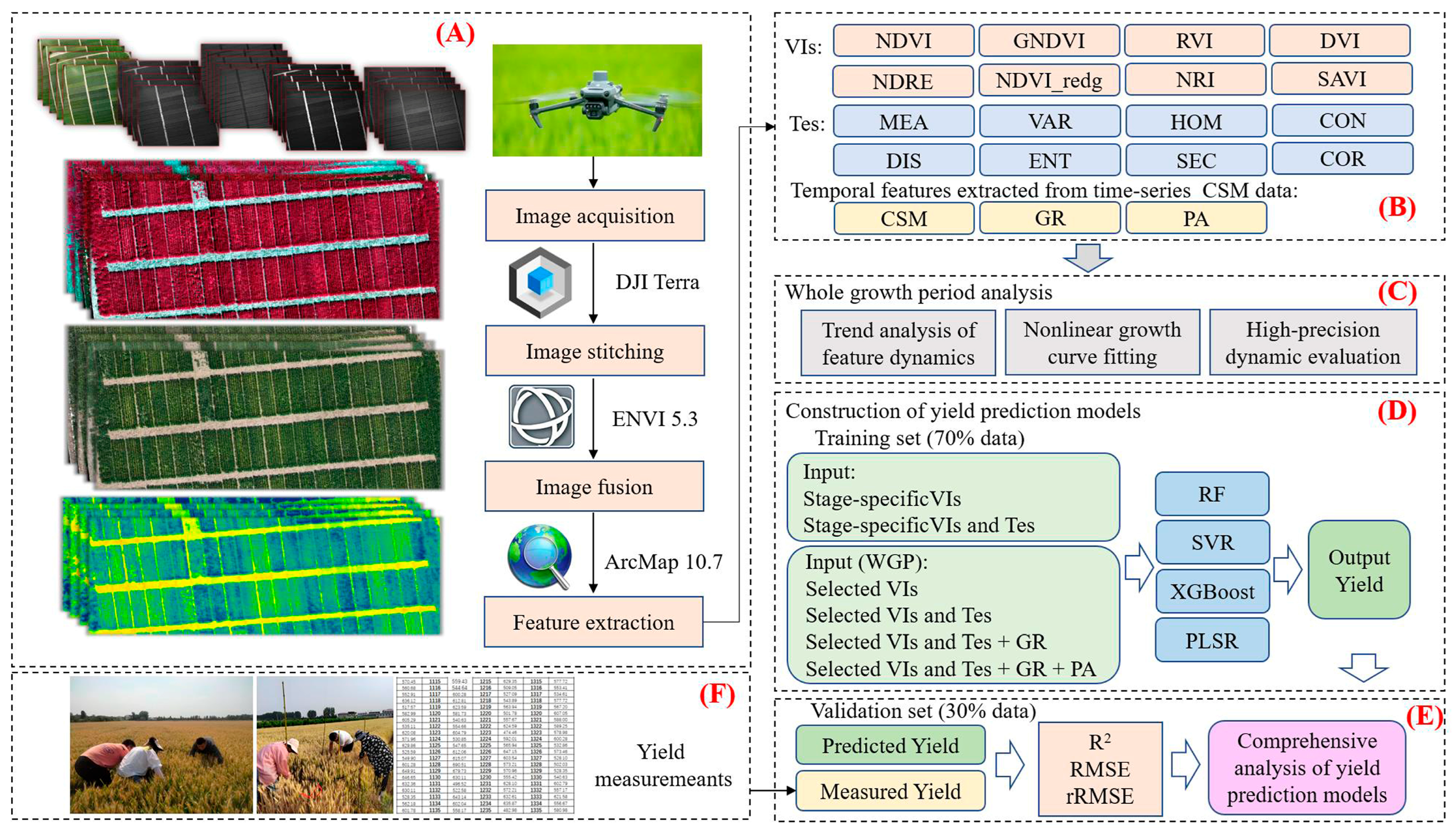

2.2. UAV Data Collection and Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield Workflows

2.3. Data Acquisition

2.3.1. UAV Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.3.2. Measurement of Wheat Yield Data

2.4. Extraction of Multi-Source Features

2.4.1. Spectral Features

2.4.2. Texture Features

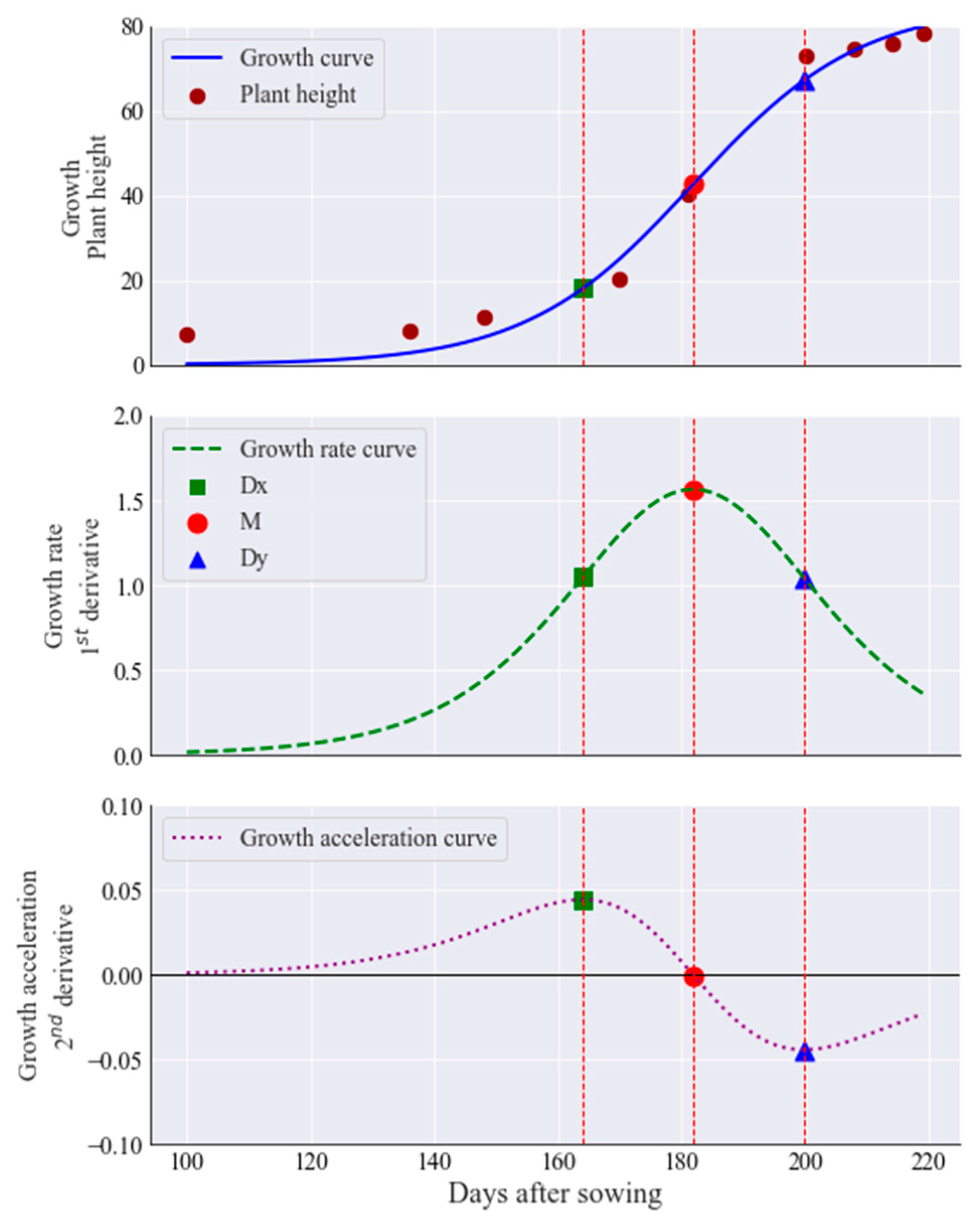

2.4.3. Canopy Height Features

2.5. Yield Estimation Model Development

2.6. Model Evaluation

3. Results

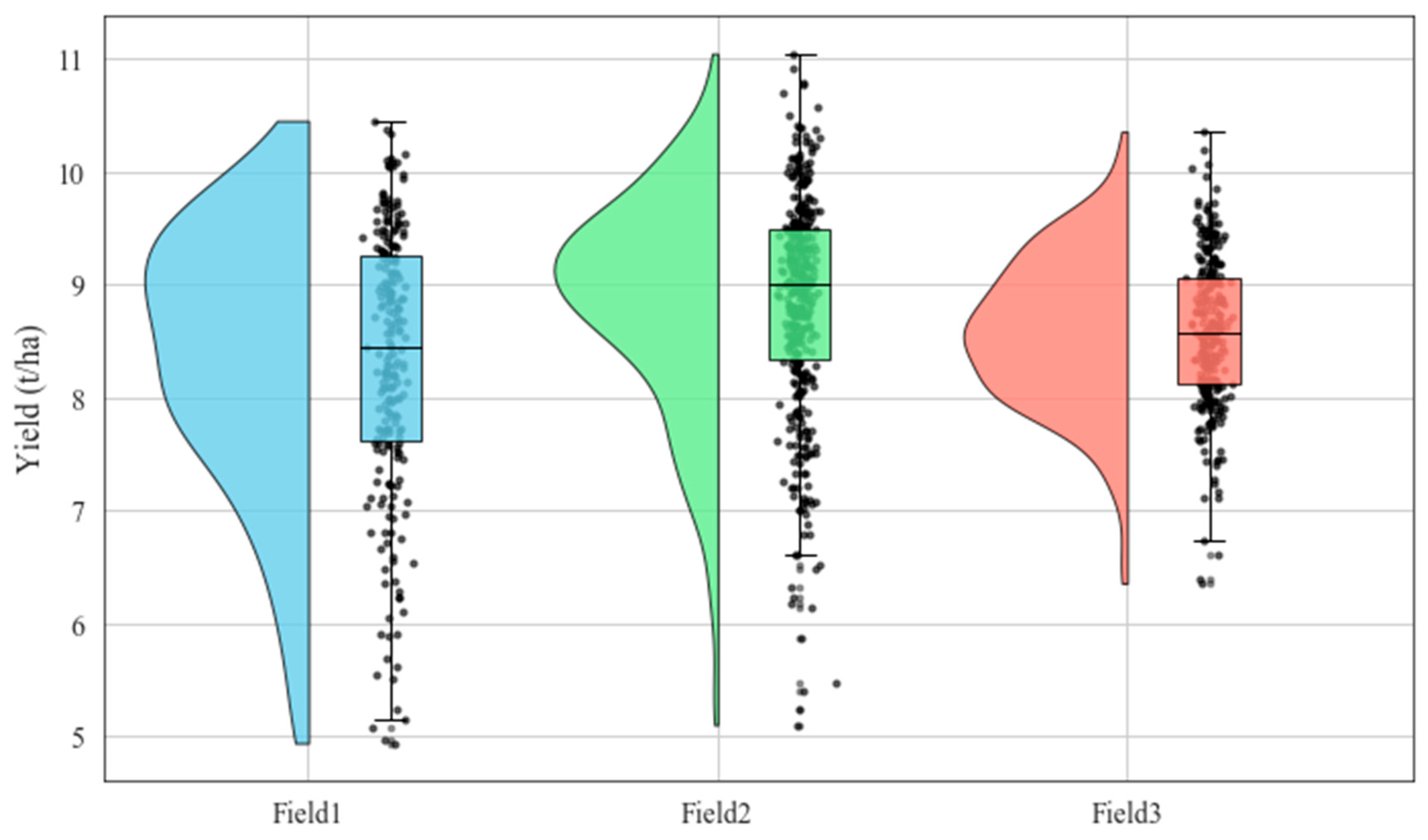

3.1. Distribution of Measured Yield Data

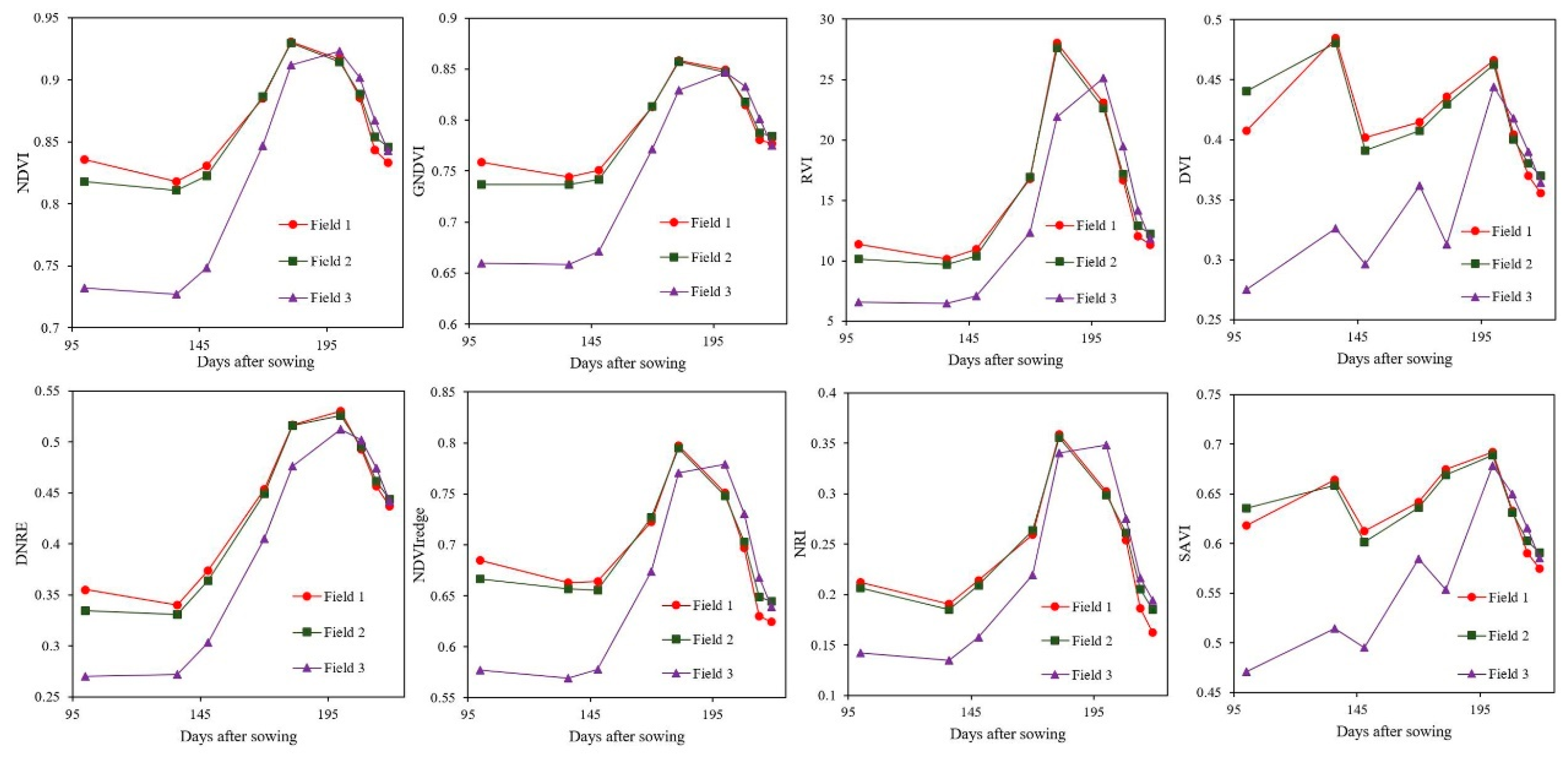

3.2. Analysis of Spectral Features

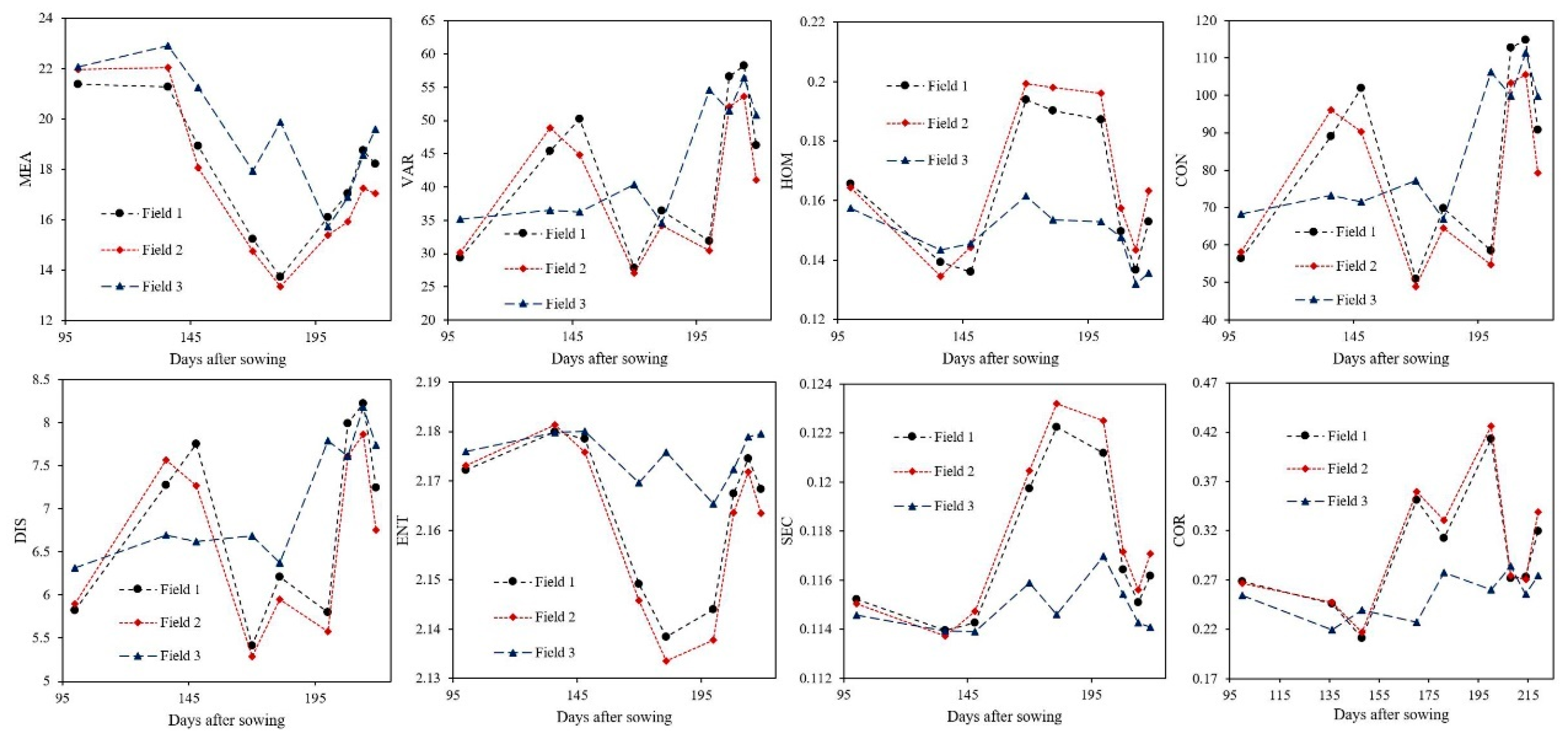

3.3. Analysis of Texture Features

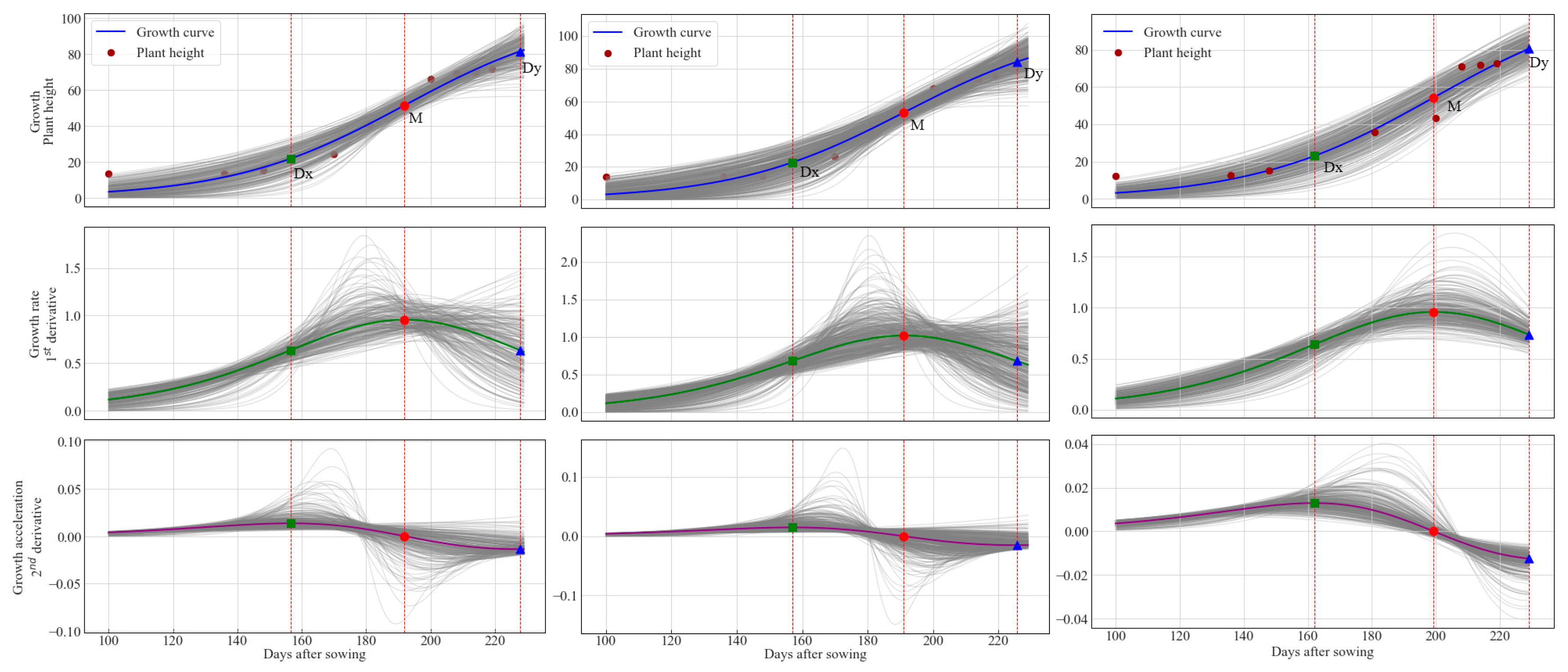

3.4. Analysis of Canopy Height Features

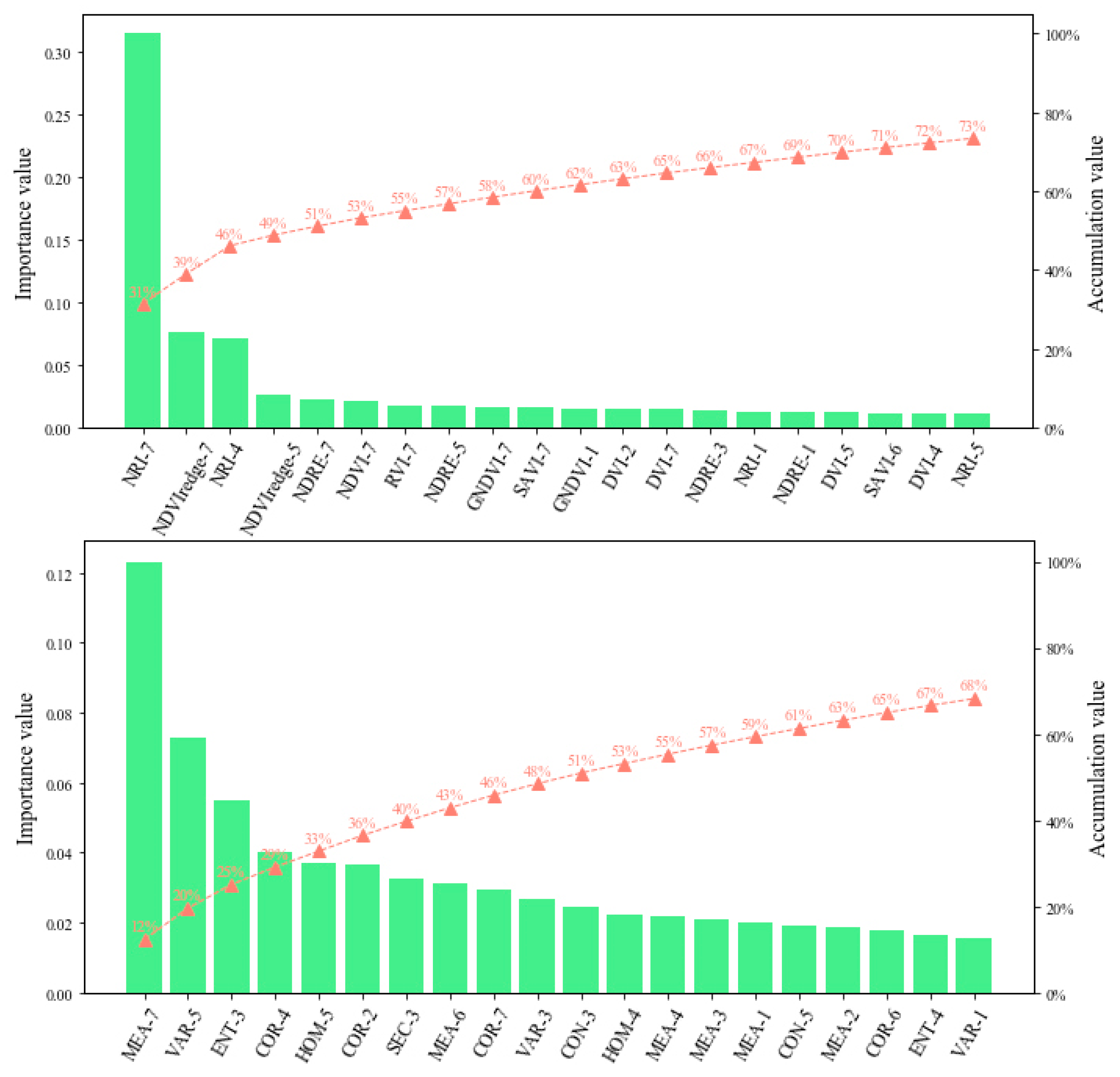

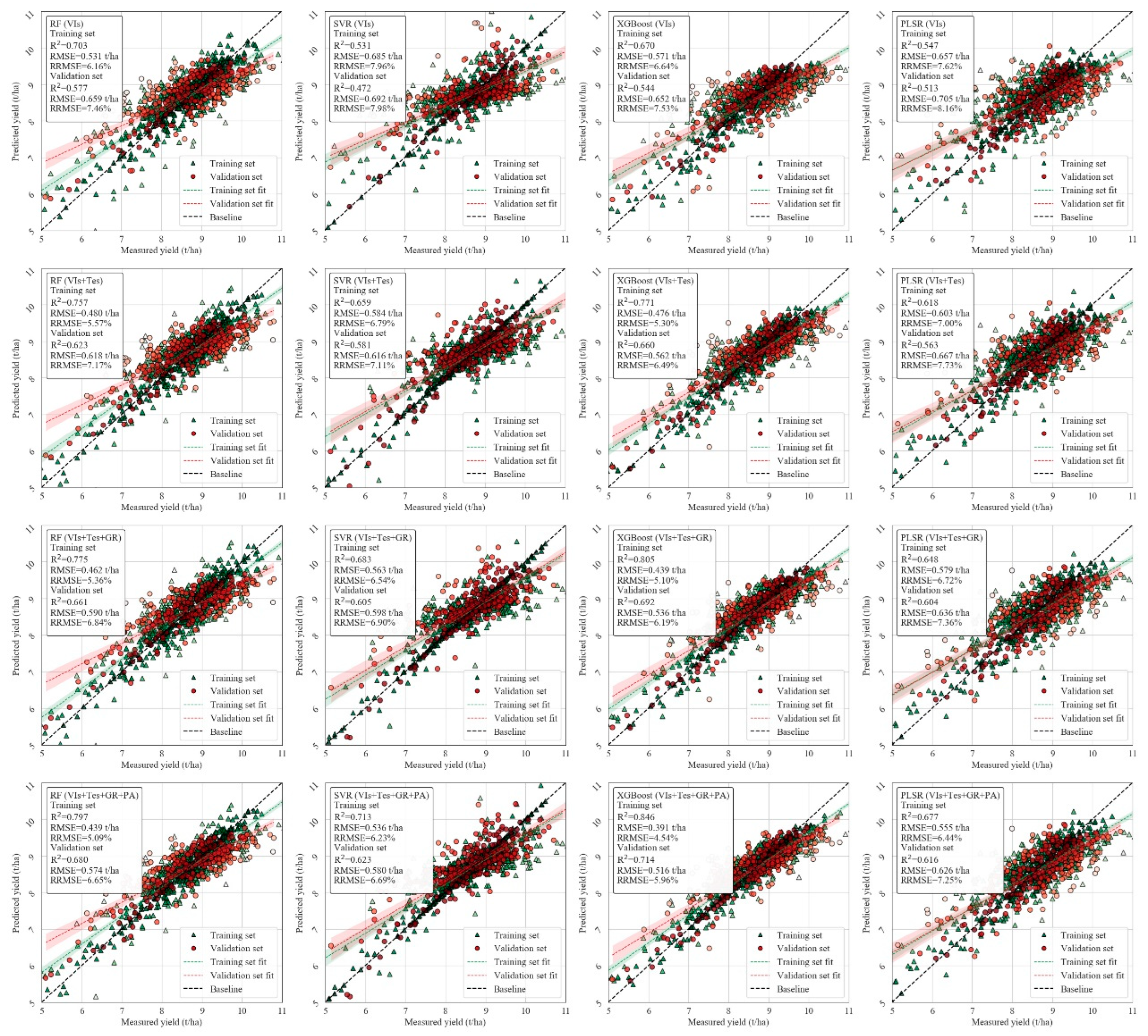

3.5. Optimal Machine Learning Model Selection for Yield Estimation

3.5.1. Stage-Specific Estimation Results

3.5.2. Estimation Results for the Whole Growth Period

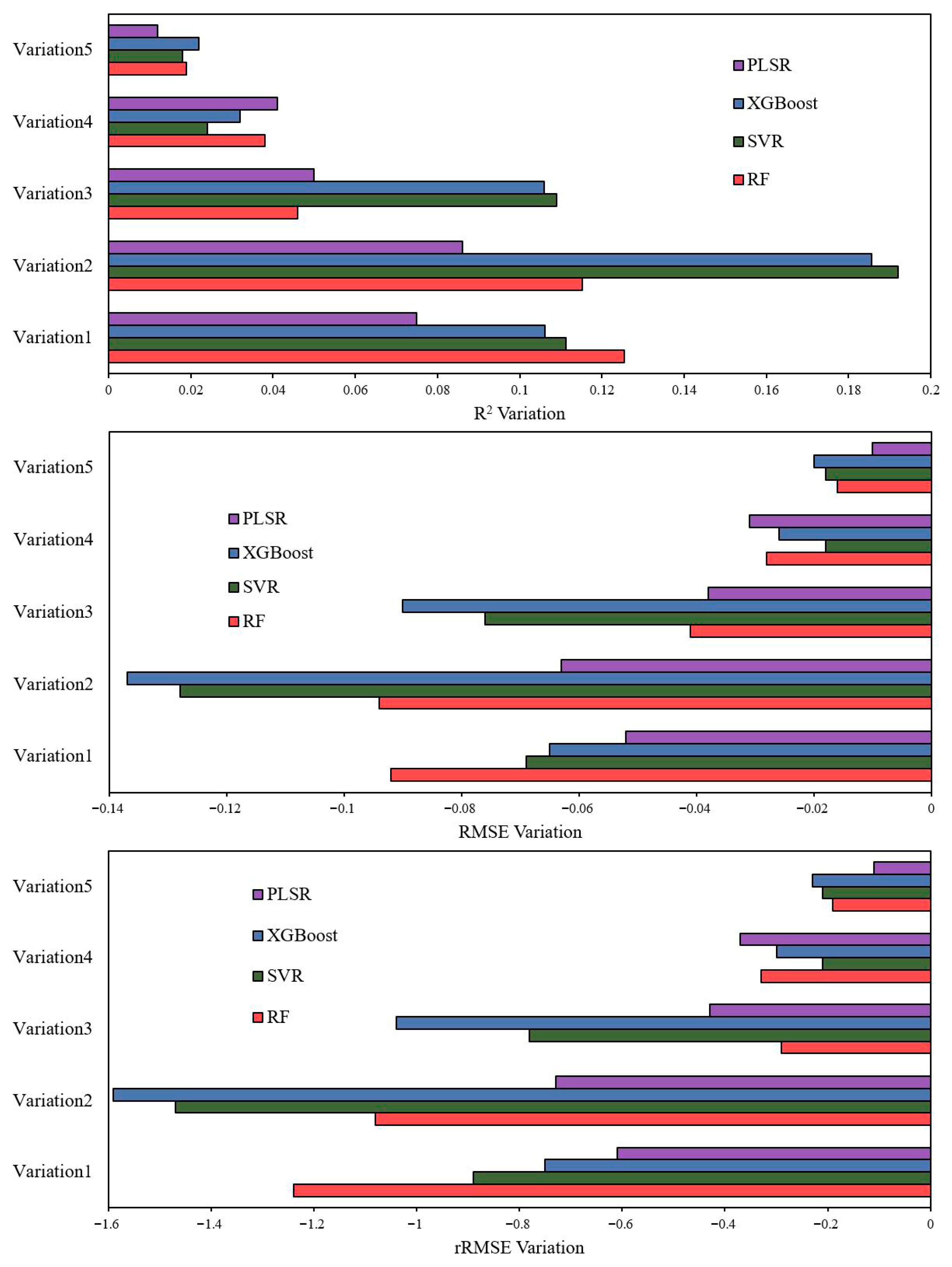

3.5.3. Evaluation of Model Estimation Accuracy

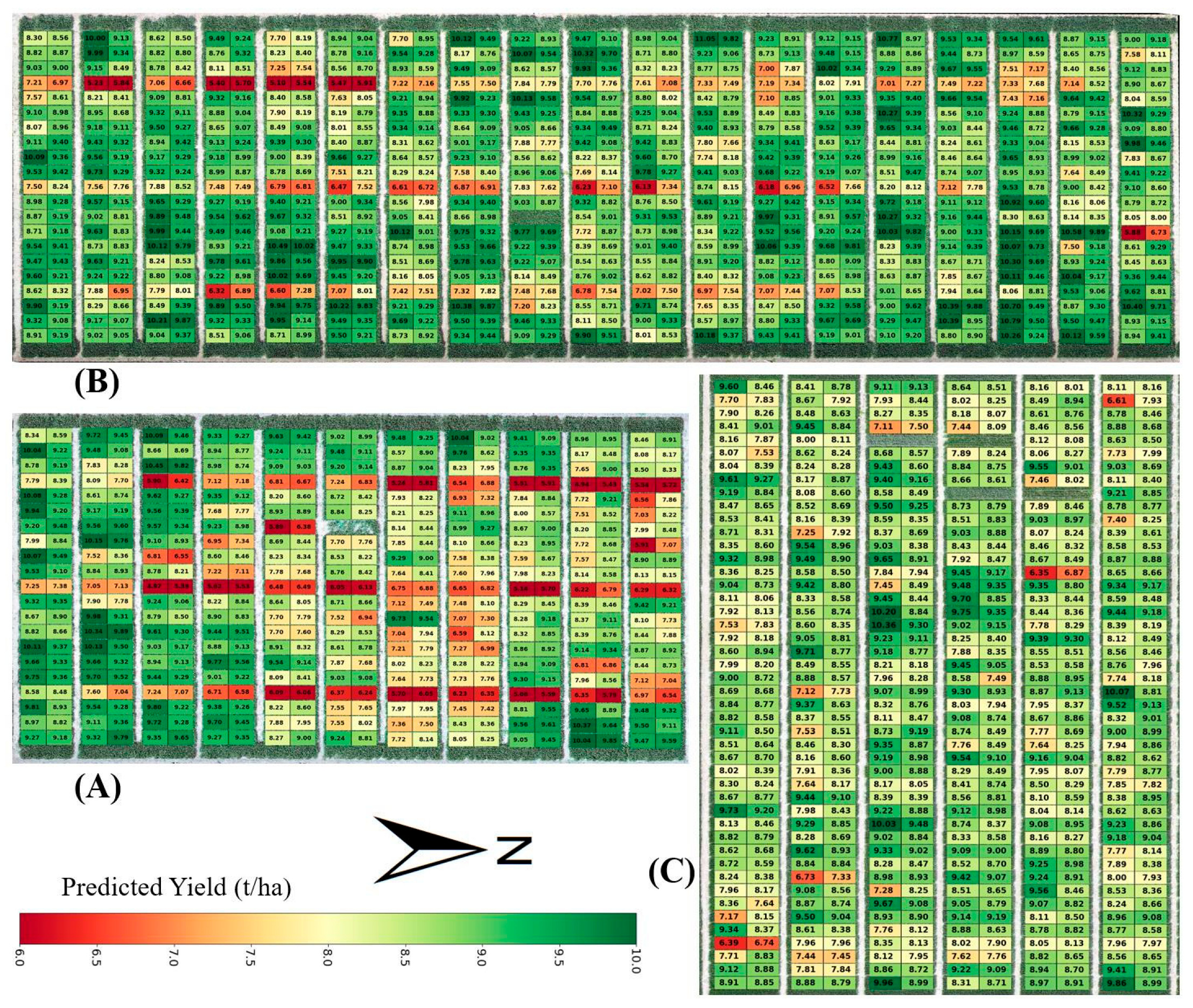

3.6. Yield Estimation Model Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges and Opportunities in Wheat Breeding: The Role of UAV-Based Phenotyping

4.2. Interpretation of Phenotypic Indicators and Growth Dynamics

4.3. Differences in the Model Performance

4.4. Practical Implications and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tester, M.; Langridge, P. Breeding technologies to increase crop production in a changing world. Science 2010, 327, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Li, L.; Schmitz, N.; Tian, L.F.; Greenberg, J.A.; Diers, B.W. Development of methods to improve soybean yield estimation and predict plant maturity with an unmanned aerial vehicle based platform. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 187, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breseghello, F.; Coelho, A.S.G. Traditional and modern plant breeding methods with examples in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2013, 61, 8277–8286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yungbluth, D.; Vong, C.N.; Scaboo, A.; Zhou, J. Estimation of the maturity date of soybean breeding lines using UAV-based multispectral imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, P.; Đorđević, V.; Milić, S.; Balešević-Tubić, S.; Petrović, K.; Miladinović, J.; Đukić, V. Prediction of soybean plant density using a machine learning model and vegetation indices extracted from RGB images taken with a UAV. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, T.; Halford, N.G. Food security: The challenge of increasing wheat yield and the importance of not compromising food safety. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2014, 164, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujeeb-Kazi, A.; Kazi, A.G.; Dundas, I.; Rasheed, A.; Ogbonnaya, F.; Kishii, M.; Bonnett, D.; Wang, R.R.; Xu, S.; Chen, P. Genetic diversity for wheat improvement as a conduit to food security. Adv. Agron. 2013, 122, 179–257. [Google Scholar]

- Novoselović, D.; Drezner, G.; Lalić, A. Contribution of wheat breeding to increased yields in Croatia from 1954. to 1985. Year. Cereal Res. Commun. 2000, 28, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.P.; Slafer, G.A.; Foulkes, J.M.; Griffiths, S.; Murchie, E.H.; Carmo-Silva, E.; Asseng, S.; Chapman, S.C.; Sawkins, M.; Gwyn, J. A wiring diagram to integrate physiological traits of wheat yield potential. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour-Aboughadareh, A.; Kianersi, F.; Poczai, P.; Moradkhani, H. Potential of wild relatives of wheat: Ideal genetic resources for future breeding programs. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Li, R.; Zhang, H. Artificial selection trend of wheat varieties released in Huang-Huai-Hai region in China evaluated using DUS testing characteristics. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 898102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Hernandez, P.; Solis, I.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Using high-resolution hyperspectral and thermal airborne imagery to assess physiological condition in the context of wheat phenotyping. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13586–13605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Schmidhalter, U.; Reynolds, M.P.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Varshney, R.K.; Yang, T.; Nie, C.; Li, Z.; Ming, B. High-throughput estimation of crop traits: A review of ground and aerial phenotyping platforms. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2020, 9, 200–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Feng, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Doonan, J.H.; Batchelor, W.D.; Xiong, L.; Yan, J. Crop phenomics and high-throughput phenotyping: Past decades, current challenges, and future perspectives. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 187–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y. A comprehensive review on recent applications of unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing with various sensors for high-throughput plant phenotyping. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 182, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Jayavelu, S.; Cammarano, D.; Fu, Y. Integrated UAV-based multi-source data for predicting maize grain yield using machine learning approaches. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Yang, C. A review on plant high-throughput phenotyping traits using UAV-based sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 178, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Yi, Y.; Liu, Y. Research on dynamic monitoring of grain filling process of winter wheat from time-series planet imageries. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Yang, H.; Gao, K.; Jin, X.; Li, Z.; Nie, C.; Zhang, G.; Fang, L.; Zhou, L.; Guo, H. Time-series NDVI and greenness spectral indices in mid-to-late growth stages enhance maize yield estimation. Field Crops Res. 2025, 333, 110069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, D.; Zhu, B.; Liu, T.; Sun, C.; Zhang, Z. Estimation of nitrogen content in wheat using indices derived from RGB and thermal infrared imaging. Field Crops Res. 2022, 289, 108735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.H.; Chen, S.; Bryant, C.R.; Li, X.; Senthilnath, J.; Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, Z.; de Beurs, K. Integrating spectral and textural information for identifying the tasseling date of summer maize using UAV based RGB images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lao, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Ning, J.; Yang, N. Diagnosis of winter-wheat water stress based on UAV-borne multispectral image texture and vegetation indices. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, N.; Aasen, H.; Bareth, G. Fusion of plant height and vegetation indices for the estimation of barley biomass. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 11449–11480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, R.; Zhu, B.; Liu, T.; Sun, C.; Guo, W. Estimation of wheat plant height and biomass by combining UAV imagery and elevation data. Agriculture 2022, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Mu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Ninomiya, S.; Jiang, D. UAV-assisted dynamic monitoring of wheat uniformity toward yield and biomass estimation. Plant Phenomics 2024, 6, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Yang, H.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Chai, X. Wheat biomass, yield, and straw-grain ratio estimation from multi-temporal UAV-based RGB and multispectral images. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 234, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borra-Serrano, I.; De Swaef, T.; Quataert, P.; Aper, J.; Saleem, A.; Saeys, W.; Somers, B.; Roldán-Ruiz, I.; Lootens, P. Closing the phenotyping gap: High resolution UAV time series for soybean growth analysis provides objective data from field trials. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, D.; de Oliveira, M.F.; Dos Santos, A.F.; Silva, E.H.C.; de Souza Rolim, G.; Da Silva, R.P. Use of remote sensing to characterize the phenological development and to predict sweet potato yield in two growing seasons. Eur. J. Agron. 2021, 129, 126337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Su, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, X.; Cheng, T.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W.; Tian, Y. Monitoring daily variation of leaf layer photosynthesis in rice using UAV-based multi-spectral imagery and a light response curve model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 291, 108098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Wang, J.; Leblon, B. Using linear regression, random forests, and support vector machine with unmanned aerial vehicle multispectral images to predict canopy nitrogen weight in corn. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Lu, B.; Shang, J.; Tan, C.; Xu, Q.; Shi, L.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y. TKSF-KAN: Transformer-enhanced oat yield modeling and transferability across major oat-producing regions in China using UAV multisource data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 224, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; Shi, H.; Wu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S. Prediction of field-scale wheat yield using machine learning method and multi-spectral UAV data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Hassan, M.A.; Xiao, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, Q.; Duan, F.; Chen, R.; Ma, Y. UAV-based multi-sensor data fusion and machine learning algorithm for yield prediction in wheat. Precis. Agric. 2023, 24, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morlin Carneiro, F.; Angeli Furlani, C.E.; Zerbato, C.; Candida De Menezes, P.; Da Silva Gírio, L.A.; Freire De Oliveira, M. Comparison between vegetation indices for detecting spatial and temporal variabilities in soybean crop using canopy sensors. Precis. Agric. 2020, 21, 979–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asam, S.; Fabritius, H.; Klein, D.; Conrad, C.; Dech, S. Derivation of leaf area index for grassland within alpine upland using multi-temporal RapidEye data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2013, 34, 8628–8652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wu, Y.; He, L.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Guo, T. An optimized non-linear vegetation index for estimating leaf area index in winter wheat. Precis. Agric. 2019, 20, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Beyer, M. Practical guidelines for choosing GLCM textures to use in landscape classification tasks over a range of moderate spatial scales. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 1312–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Yang, Z.; Su, P.; Wei, K.; Wang, Z.; Yang, C.; Wang, C.; Qin, M.; Xiao, L.; Yang, W. Non-destructive monitoring of maize LAI by fusing UAV spectral and textural features. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1158837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanza, R.; Zaman-Allah, M.; Cairns, J.E.; Magorokosho, C.; Tarekegne, A.; Olsen, M.; Prasanna, B.M. High-throughput phenotyping of canopy cover and senescence in maize field trials using aerial digital canopy imaging. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiyuan, H.; Ziqiu, L.; Xiangqian, F.; Jinhua, Q.; Aidong, W.; Shichao, J.; Danying, W.; Song, C. Estimating key phenological dates of multiple rice accessions using unmanned aerial vehicle-based plant height dynamics for breeding. Rice Sci. 2024, 31, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, M.; Hao, F.; Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; de Beurs, K.; Fu, Y.H.; He, Y. Identifying crop phenology using maize height constructed from multi-sources images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 115, 103121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Cheverud, J.M. A mechanistic model for genetic machinery of ontogenetic growth. Genetics 2004, 168, 2383–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, S.; Lied, L.M.; Burud, I.; Dieseth, J.A.; Alsheikh, M.; Lillemo, M. Sequential forward selection and support vector regression in comparison to LASSO regression for spring wheat yield prediction based on UAV imagery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 183, 106036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodjaev, S.; Bobojonov, I.; Kuhn, L.; Glauben, T. Optimizing machine learning models for wheat yield estimation using a comprehensive UAV dataset. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Feng, H.; Xu, L.; Miao, M.; Yang, G.; Yang, X.; Fan, L. Estimation of the yield and plant height of winter wheat using UAV-based hyperspectral images. Sensors 2020, 20, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Z.; Jiang, J.; Gao, Y.; Krienke, B.; Wang, M.; Zhong, K.; Cao, Q.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, W. Wheat growth monitoring and yield estimation based on multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, F.; Ammar, K.; Solís, I. Global changes in cultivated area and breeding activities of durum wheat from 1800 to date: A historical review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.K.; Singh, I.S. Comparative evaluation of maize inbred lines (Zea mays L.) according to DUS testing using morphological, physiological and molecular markers. Agric. Sci. 2010, 1, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ganeva, D.; Roumenina, E.; Dimitrov, P.; Gikov, A.; Jelev, G.; Dragov, R.; Bozhanova, V.; Taneva, K. Phenotypic traits estimation and preliminary yield assessment in different phenophases of wheat breeding experiment based on UAV multispectral images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W.; Yang, T.; Liu, Z.; Rezaei, E.E.; Li, J.; Sun, Z.; Xin, X. Combination of UAV and deep learning to estimate wheat yield at ripening stage: The potential of phenotypic features. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 124, 103494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Deng, Q.; Camenzind, M.; Luca, S.V.; Qin, W.; Hu, Y.; Minceva, M.; Yu, K. High-throughput phenotyping of canopy dynamics of wheat senescence using UAV multispectral imaging. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.T.; Chen, Q.; Massey-Reed, S.R.; Potgieter, A.B.; Chapman, S.C. Prediction accuracy and repeatability of UAV based biomass estimation in wheat variety trials as affected by variable type, modelling strategy and sampling location. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Yang, M.; Rasheed, A.; Tian, X.; Reynolds, M.; Xia, X.; Xiao, Y.; He, Z. Quantifying senescence in bread wheat using multispectral imaging from an unmanned aerial vehicle and QTL mapping. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 2623–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, S.; Reddy, S.K.; Gowda, P.H.; Xue, Q.; Rudd, J.C.; Pradhan, G.; Liu, S.; Stewart, B.A.; Biradar, C.; Jessup, K.E. Spectral reflectance models for characterizing winter wheat genotypes. J. Crop. Improv. 2016, 30, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, T.; Shi, L.; Wang, W.; Niu, Z.; Guo, W.; Ma, X. Combining spectral and texture features of UAV hyperspectral images for leaf nitrogen content monitoring in winter wheat. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2022, 43, 2335–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, X.; Su, P.; Su, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Z.; Gao, C.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, M.; Shafiq, F. Estimation of winter wheat LAI based on color indices and texture features of RGB images taken by UAV. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2025, 105, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, M.; Liu, Y.; Fu, M.; Li, C.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, H.; Xing, E.; Ren, Y. Combining spectral and texture feature of UAV image with plant height to improve LAI estimation of winter wheat at jointing stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1272049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Veeranampalayam-Sivakumar, A.; Bhatta, M.; Garst, N.D.; Stoll, H.; Stephen Baenziger, P.; Belamkar, V.; Howard, R.; Ge, Y.; Shi, Y. Principal variable selection to explain grain yield variation in winter wheat from features extracted from UAV imagery. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, S.B.; Hirsch, C.N.; Springer, N.M. UAV-based imaging platform for monitoring maize growth throughout development. Plant Direct 2020, 4, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Yang, G.; Yang, X.; Song, X.; Xu, B.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Yang, H.; Wu, J. An explainable XGBoost model improved by SMOTE-ENN technique for maize lodging detection based on multi-source unmanned aerial vehicle images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 194, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhues, C.C.; Mahone, G.S.; Da Silva, S.; Thorwarth, P.; Schmidt, M.; Richter, J.; Simianer, H.; Beissinger, T.M. Prediction of maize phenotypic traits with genomic and environmental predictors using gradient boosting frameworks. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, J.C.M.; Mesa, H.G.A.; Espinosa, A.T.; Castilla, S.R.; Lamont, F.G. Improving Wheat Yield Prediction through Variable Selection Using Support Vector Regression, Random Forest, and Extreme Gradient Boosting. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.S.; Wang, J. Evaluation of machine learning regression techniques for estimating winter wheat biomass using biophysical, biochemical, and UAV multispectral data. Drones 2024, 8, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, L.; Duan, J.; Zang, S.; Yang, T.; Schulthess, U.; Guo, T.; Wang, C.; Feng, W. Aboveground wheat biomass estimation from a low-altitude UAV platform based on multimodal remote sensing data fusion with the introduction of terrain factors. Precis. Agric. 2024, 25, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Liu, J.; Shang, J.; Qian, B.; Ma, B.; Kovacs, J.M.; Walters, D.; Jiao, X.; Geng, X.; Shi, Y. Assessment of red-edge vegetation indices for crop leaf area index estimation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 222, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Yang, M.; Rasheed, A.; Yang, G.; Reynolds, M.; Xia, X.; Xiao, Y.; He, Z. A rapid monitoring of NDVI across the wheat growth cycle for grain yield prediction using a multi-spectral UAV platform. Plant Sci. 2019, 282, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wu, F.; Mou, N.; Zhu, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, C. The estimation of wheat yield combined with UAV canopy spectral and volumetric data. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durgun, Y.Ö.; Gobin, A.; Duveiller, G.; Tychon, B. A study on trade-offs between spatial resolution and temporal sampling density for wheat yield estimation using both thermal and calendar time. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 86, 101988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gu, L.; Dai, M.; Bao, X.; Sun, Q.; Qu, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Fan, C.; Gu, X. Estimation of grain filling rate and thousand-grain weight of winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using UAV-based multispectral images. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 159, 127258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, M.; Hu, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Wang, B.; Gou, X. Utilizing UAV-based high-throughput phenotyping and machine learning to evaluate drought resistance in wheat germplasm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Honkavaara, E.; Hayden, M.; Kant, S. UAV remote sensing phenotyping of wheat collection for response to water stress and yield prediction using machine learning. Plant Stress 2024, 12, 100464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, L.V.; Atkinson Amorim, J.G.; Guimarães, L.; Motta Matos, D.; Maciel Da Costa, C.; Parraga, A. Above-ground biomass wheat estimation: Deep learning with UAV-based RGB images. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2055392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Full Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index | (NIR − Red)/(NIR + Red) |

| GNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index | (NIR − Green)/(NIR + Green) |

| RVI | Ratio vegetation index | NIR/Red |

| DVI | Difference vegetation index | NIR − Red |

| NDRE | Normalized difference red edge index | (NIR − Red_edge)/(NIR + Red_edge) |

| NDVI_redg | Normalized difference vegetation index red-edge | (Red_edge − Red)/(Red_edge + Red) |

| NRI | Nitrogen reflectance index | (Green − Red)/(Green + Red) |

| SAVI | Soil adjusted vegetation index | 1.5 (NIR − Red)/(NIR + Red + 0.5) |

| Abbreviation | Full Name | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| MEA | Mean | |

| VAR | Variance | |

| HOM | Homogeneity | |

| CON | Contrast | |

| DIS | Dissimilarity | |

| ENT | Entropy | |

| SEC | Second moment | |

| COR | Correlation |

| Growth Stage | Model | Training Set R2 | Validation Set R2 | Training Set RMSE (t/ha) | Validation Set RMSE (t/ha) | Training Set rRMSE | Validation Set rRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overwintering stage | RF | 0.319 | 0.166 | 0.804 | 0.926 | 9.32% | 10.74% |

| SVR | 0.143 | 0.095 | 0.926 | 0.905 | 10.76% | 10.45% | |

| XGBoost | 0.363 | 0.246 | 0.794 | 0.838 | 9.23% | 9.68% | |

| PLSR | 0.137 | 0.13 | 0.906 | 0.942 | 10.52% | 10.91% | |

| Regreening stage | RF | 0.218 | 0.12 | 0.861 | 0.951 | 9.99% | 11.02% |

| SVR | 0.114 | 0.073 | 0.941 | 0.916 | 10.94% | 10.57% | |

| XGBoost | 0.378 | 0.252 | 0.785 | 0.835 | 9.12% | 9.64% | |

| PLSR | 0.1 | 0.084 | 0.926 | 0.966 | 10.74% | 11.19% | |

| Jointing stage | RF | 0.137 | 0.08 | 0.904 | 0.972 | 10.49% | 11.27% |

| SVR | 0.126 | 0.081 | 0.935 | 0.912 | 10.87% | 10.53% | |

| XGBoost | 0.272 | 0.173 | 0.848 | 0.877 | 9.86% | 10.13% | |

| PLSR | 0.071 | 0.045 | 0.941 | 0.986 | 10.91% | 11.43% | |

| Booting stage | RF | 0.067 | 0.048 | 0.941 | 0.989 | 10.91% | 11.47% |

| SVR | 0.074 | 0.035 | 0.962 | 0.934 | 11.18% | 10.78% | |

| XGBoost | 0.273 | 0.169 | 0.848 | 0.88 | 9.85% | 10.16% | |

| PLSR | 0.075 | 0.053 | 0.938 | 0.983 | 10.89% | 11.38% | |

| Heading stage | RF | 0.299 | 0.169 | 0.815 | 0.924 | 9.46% | 10.71% |

| SVR | 0.17 | 0.111 | 0.911 | 0.897 | 10.59% | 10.35% | |

| XGBoost | 0.367 | 0.271 | 0.791 | 0.824 | 9.19% | 9.51% | |

| PLSR | 0.21 | 0.157 | 0.867 | 0.927 | 10.06% | 10.74% | |

| Flowering stage | RF | 0.447 | 0.327 | 0.724 | 0.832 | 8.40% | 9.64% |

| SVR | 0.23 | 0.182 | 0.877 | 0.86 | 10.20% | 9.93% | |

| XGBoost | 0.454 | 0.334 | 0.735 | 0.787 | 8.54% | 9.09% | |

| PLSR | 0.317 | 0.252 | 0.806 | 0.891 | 9.36% | 10.32% | |

| Grain filling stage | RF | 0.53 | 0.452 | 0.667 | 0.751 | 7.74% | 8.70% |

| SVR | 0.42 | 0.361 | 0.761 | 0.761 | 8.85% | 8.78% | |

| XGBoost | 0.57 | 0.448 | 0.652 | 0.717 | 7.57% | 8.28% | |

| PLSR | 0.4559 | 0.438 | 0.72 | 0.757 | 8.35% | 8.77% |

| Growth Stage | Model | Training Set R2 | Validation Set R2 | Training Set RMSE (t/ha) | Validation Set RMSE (t/ha) | Training Set rRMSE | Validation Set rRMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overwintering stage | RF | 0.346 | 0.2 | 0.788 | 0.907 | 9.14% | 10.51% |

| SVR | 0.185 | 0.157 | 0.903 | 0.874 | 10.49% | 10.08% | |

| XGBoost | 0.391 | 0.262 | 0.776 | 0.829 | 9.02% | 9.57% | |

| PLSR | 0.277 | 0.199 | 0.83 | 0.903 | 9.63% | 10.46% | |

| Regreening stage | RF | 0.324 | 0.184 | 0.801 | 0.916 | 9.29% | 10.62% |

| SVR | 0.142 | 0.121 | 0.926 | 0.892 | 10.77% | 10.30% | |

| XGBoost | 0.4 | 0.277 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 8.95% | 9.48% | |

| PLSR | 0.224 | 0.164 | 0.859 | 0.923 | 9.97% | 10.69% | |

| Jointing stage | RF | 0.364 | 0.21 | 0.777 | 0.901 | 9.01% | 10.44% |

| SVR | 0.179 | 0.116 | 0.906 | 0.894 | 10.53% | 10.32% | |

| XGBoost | 0.355 | 0.207 | 0.799 | 0.859 | 9.28% | 9.92% | |

| PLSR | 0.224 | 0.161 | 0.869 | 0.924 | 10.07% | 10.71% | |

| Booting stage | RF | 0.278 | 0.154 | 0.828 | 0.933 | 9.60% | 10.81% |

| SVR | 0.125 | 0.087 | 0.936 | 0.909 | 10.87% | 10.49% | |

| XGBoost | 0.327 | 0.189 | 0.816 | 0.869 | 9.48% | 10.03% | |

| PLSR | 0.105 | 0.081 | 0.933 | 0.968 | 10.81% | 11.21% | |

| Heading stage | RF | 0.38 | 0.257 | 0.524 | 0.874 | 6.08% | 10.13% |

| SVR | 0.186 | 0.129 | 0.902 | 0.888 | 10.48% | 10.25% | |

| XGBoost | 0.488 | 0.339 | 0.712 | 0.784 | 8.27% | 9.06% | |

| PLSR | 0.279 | 0.202 | 0.829 | 0.902 | 9.61% | 10.45% | |

| Flowering stage | RF | 0.492 | 0.369 | 0.694 | 0.806 | 8.05% | 9.34% |

| SVR | 0.352 | 0.221 | 0.805 | 0.84 | 9.36% | 9.69% | |

| XGBoost | 0.529 | 0.4 | 0.683 | 0.748 | 7.93% | 8.63% | |

| PLSR | 0.391 | 0.314 | 0.761 | 0.836 | 8.84% | 9.68% | |

| Grain filling stage | RF | 0.619 | 0.508 | 0.601 | 0.711 | 6.98% | 8.25% |

| SVR | 0.444 | 0.389 | 0.745 | 0.744 | 8.66% | 8.58% | |

| XGBoost | 0.607 | 0.475 | 0.624 | 0.699 | 7.25% | 8.08% | |

| PLSR | 0.505 | 0.477 | 0.687 | 0.73 | 7.97% | 8.46% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Yi, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H.; et al. Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding Lines and Registered Varieties Using Multi-Temporal UAV Data. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242554

Liu L, Zhou X, Liu T, Liu D, Liu J, Wang J, Yi Y, Zhu X, Zhang N, Zhang H, et al. Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding Lines and Registered Varieties Using Multi-Temporal UAV Data. Agriculture. 2025; 15(24):2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242554

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Liwei, Xinxing Zhou, Tao Liu, Dongtao Liu, Jing Liu, Jing Wang, Yuan Yi, Xuecheng Zhu, Na Zhang, Huiyun Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding Lines and Registered Varieties Using Multi-Temporal UAV Data" Agriculture 15, no. 24: 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242554

APA StyleLiu, L., Zhou, X., Liu, T., Liu, D., Liu, J., Wang, J., Yi, Y., Zhu, X., Zhang, N., Zhang, H., Feng, G., & Ma, H. (2025). Characterizing Growth and Estimating Yield in Winter Wheat Breeding Lines and Registered Varieties Using Multi-Temporal UAV Data. Agriculture, 15(24), 2554. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15242554