Abstract

Acyl-CoA-binding proteins (ACBPs) are essential lipid carrier proteins involved in plant lipid metabolism. However, the systematic identification and expression profiles of the ACBP gene family in citrus species remain poorly understood. Here, Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were chosen as model species to examine the biological properties of citrus ACBPs. Using bioinformatics methods, five ACBP gene members were found in each species and named CsACBPs and PtrACBPs, respectively. All obtained ACBP members were divided into four subfamilies based on conserved domains and amino acid sequences. CsACBP and PtrACBP genes exhibited structural variation in motifs and exons. The predicted protein structures of CsACBPs and PtrACBPs exhibited conservation between the two species while displaying distinct variation within each species. Collinearity analysis showed one intraspecific pairing relationship in each of the two citrus species. Furthermore, there were more collinear couplings between citrus species and Arabidopsis thaliana but none between citrus species and Oryza sativa (rice). Notably, the analysis of cis-acting elements in ACBP gene promoters identified a number of motifs associated with light, abiotic stresses, and phytohormones. Expression profiling confirmed tissue-specific expression patterns of CsACBP1~5 and PtrACBP1~5. RT-qPCR analysis revealed that all CsACBP and PtrACBP genes responded to cold and salt stresses, though the magnitude of their responses varied significantly. Specially, although PtrACBP5 did not respond to low temperatures as rapidly as other members, its expression level increased significantly after 24 h of low-temperature treatment. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network predictions indicated tight associations among four of the five CsACBPs, with CsACBP5 excluded from these interactions. Moreover, CsACBP1, CsACBP2, and CsACBP3 were predicted to be potential targets of csi-miR3952, csi-miR396a, and csi-miR477b, respectively. Overall, our research provides a solid foundation for further investigations into the biological functions and regulatory mechanisms of ACBP genes in citrus growth, development, and stress adaptation.

1. Introduction

In plants, lipids are essential for preserving the structural integrity of cell membranes, supplying energy for metabolic processes, and modulating reactions to external stressors. Plant lipid metabolism depends heavily on acyl-CoA-binding proteins (ACBPs), a class of lipid carrier proteins distinguished by the presence of an acyl-CoA-binding domain [1]. To date, the ACBP gene family has been found in a number of plant species. For example, six ACBP members have been reported in Arabidopsis, six in rice, four in cucumbers (Cucumis sativus), ten in sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), and six in grapes (Vitis vinifera) [2]. The majority of the discovered ACBP family members reside in subcellular compartments such as the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, and cell membrane [3,4,5]. They primarily transport and exchange lipids, but they also have a role in physiological processes such as saturated fatty acid metabolism, acyl-CoA homeostasis, fatty acid β-oxidation, and vesicular trafficking. ACBPs play vital roles in plant growth, development, and adaptation to harsh environmental conditions. In agricultural crops, ACBP-mediated lipid metabolism and stress tolerance may directly impact yield and quality, highlighting their potential for crop improvement [6,7,8].

ACBP members can be classified into four categories based on their amino acid composition and structural domains, as shown for ACBPs in Arabidopsis. Small ACBPs (single-domain with small molecular weight), ANK ACBPs (Ankyrin Repeats ACBPs), Large ACBPs (single-domain with large molecular weight), and Kelch-ACBPs (Kelch Motifs ACBPs). Small ACBPs consist of approximately 100 amino acid residues and contain an ACB domain. In addition to the ACB domain, ANK-ACBPs and Kelch-ACBPs possess two ankyrin domains and kelch domains at the carboxyl terminus of the protein, respectively. Large ACBPs typically consist of 215–700 amino acid residues and also contain an ACB domain [9,10]. Plant ACBP genes can respond to various environmental stresses. In Arabidopsis, overexpression of AtACBP1 and AtACBP6 positively regulated plant freezing tolerance through signaling pathways mediated by phospholipase D or ABA [11,12]. Overexpression of AtACBP2 regulated the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in guard cells via the ABA signaling pathway, leading to guard cell closure, reduced water evaporation, and thus enhanced drought tolerance in plants [13]. AtACBP3 was found in the apoplast of phloem, companion cells, and sieve elements in Arabidopsis. By controlling the metabolism of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs), it contributed to plant responses to hypoxia and helped produce jasmonic acid in response to wounding [14,15]. Meanwhile, leaf senescence was accelerated in AtACBP3-overexpressing plants, and this acceleration was dependent on salicylic acid [16]. Moreover, AtACBP3, AtACBP4, and AtACBP6 played crucial roles in cuticle development and defense against microbial pathogens [17]. Recent studies had also shown that AtACBP4 was involved in plant responses to flooding-induced hypoxia stress [18].

Among the rice ACBP family members (OsACBPs), all except OsACBP6, which exhibited no significant response to cold stress, had their gene expression levels suppressed after 12 h of cold treatment. OsACBP1, OsACBP2, and OsACBP3 were not affected by drought or high-salt stress. OsACBP4 and OsACBP5 both responded to salt stress, with their expression peaking at 12 h after salt treatment, whereas OsACBP4 exhibited a rapid response to drought stress [19]. Furthermore, Overexpression of maize (Zea mays) ACBP1 enhanced drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants [20]. PA signaling and alternative splicing inhibited the ligand-dependent interaction between GmACBP3/GmACBP4 and VLXB, thereby triggering lipid peroxidation during salt stress in soybean (Glycine max) [21]. Currently, with the deepening of research on plant ACBPs, people have gained a more profound understanding of the mechanisms of these lipid carrier proteins in stress responses. Nevertheless, most research findings come from model plants, and there is relatively little research on ACBPs in other woody plants, especially fruit tree species.

Citrus is one of the most important fruit crops worldwide, cultivated in more than 140 countries and regions. Brazil, India, and China are the major citrus-producing countries, with China ranking first in both cultivation area and total yield. As one of the native origins of citrus, China boasts a great diversity of citrus varieties. Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck (sweet orange) accounts for approximately 50% of global citrus production and is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions around the world [22]. With juicy pulp and rich nutritional components such as vitamin C, flavonoids, and dietary fiber, it is the most economically important cultivated species in the genus Citrus. In contrast, Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. (synonym is Citrus trifoliata L.) (trifoliate orange), a wild citrus resource native to China, typically has thick, sturdy thorns and exhibits strong tolerance to cold and poor soil conditions, making it widely used as an excellent rootstock for citrus. To date, the ACBP gene family in these two Citrus species has not been systematically identified, and their expression characteristics remain unclear.

Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a systematic identification and genome-wide analysis of the ACBP gene family in the genomes of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. Specifically, we analyzed the phylogenetic tree, gene structure, chromosomal localization, conserved sequences, cis-acting elements, expression patterns in different tissues, and responses to cold and salt stresses of ACBP genes. Our results will lay a foundation for in-depth understanding of the role of ACBP genes in the response of citrus to low-temperature and salt stresses, and provide important theoretical support for further elucidating the biological functions of citrus ACBP genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of ACBP Family Genes in Citrus Sinensis and Poncirus Trifoliata

To precisely identify the ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata, the whole-genome sequence files, protein sequence files, and their corresponding gene annotation data were retrieved from CPBD (http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/index.php (accessed on 9 November 2023)). Meanwhile, the whole-genome sequence files, protein sequence files, and genome annotation data of Arabidopsis and rice were obtained from the Ensembl Plant Reference Genome Database (https://plants.ensembl.org (accessed on 9 November 2023)). This comprehensive data collection step ensures a broad and reliable basis for subsequent analyses. The protein sequences of six ACBP family members from each Arabidopsis and rice species were used to perform a BLAST search against the entire citrus genome using TBtools v2.332. The E-value threshold for the search was set at e-5 to obtain candidate protein sequences. Subsequently, the obtained candidate protein sequences were further screened. The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) files and Pfam identifiers (Pfam IDs) of the ACBP gene family were downloaded from the online Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2023)). Both the Pfam database and the SMART database (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/ (accessed on 14 November 2024)) were applied to identify conserved domains. Proteins containing the ACB domain, the ankyrin (ANK) domain, and the Kelch domain at the C-terminus were determined as the finally identified members of the citrus ACBP gene family.

The TBtools v2.332 and the Expasy website (http://www.expasy.org/ (accessed on 13 November 2023)) were utilized to predict and analyze the physicochemical properties of the proteins in the citrus ACBP family, including the isoelectric point (pI), instability index, amino acid length, and hydrophilicity. The online platforms Plant-mPLoc (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant-multi/ (accessed on 12 November 2023)) and Wolfpsort (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp (accessed on 12 November 2023)) were employed to predict their subcellular localization.

2.2. Chromosomal Locations of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes

The “Gene Location Visualize from GTF/GFF” module of TBtools v2.332was employed. Using the citrus gene annotation file and the ACBP gene ID numbers as input materials, a chromosomal location map of the citrus ACBP family members was generated.

2.3. Construction of Phylogenetic Trees of ACBP Gene Families in Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, Arabidopsis, and Rice

The MEGA 11 software [23] was employed to conduct multiple sequence alignments of the identified ACBP families in Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, Arabidopsis, and rice. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the maximum-likelihood method. The Bootstrap Replications were set to 1000, while other parameters were maintained at their default values. Subsequently, the online platform Evolview (https://www.evolgenius.info/ (accessed on 21 March 2024)) was utilized to edit and enhance the visual appearance of the phylogenetic trees.

2.4. Exon/Intron Structure and Conserved Motifs Analysis

The conserved domains of ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were retrieved through a query on the Prosite online website (https://prosite.expasy.org/ (accessed on 12 November 2023)). Thereafter, the IBS 2.0 software [24] was applied to create the primary-structure diagrams of the proteins.

2.5. Motif Analysis, Conserved Domains, and Gene Structures of the ACBP Gene Family

Motif analysis was carried out via the online platform MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme (accessed on 12 November 2023)). The number of motifs was set to 10, with other parameters remaining at their default values. The TBtools v2.332 was utilized to analyze the gene structures. Moreover, visual graphs were generated for the motif analysis results, conserved domains, and gene structures.

2.6. Prediction of CsACBPs and PtrACBPs Protein Structures

The prediction of secondary and tertiary structures of the CsACBP and PtrACBP were conducted utilizing SOPMA (https://npsa.lyon.inserm.fr/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)) and SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org/interactive (accessed on 20 June 2025)), respectively. Phosphorylation sites were analyzed via CBS-NetPhos 3.1 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos-3.1/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)).

2.7. Collinearity Analysis of the ACBP Gene Family

The protein sequences of Arabidopsis were retrieved from the TAIR website (https://www.Arabidopsis.org/ (accessed on 9 November 2023)). The protein sequences of rice were obtained from the Ensembl Plant Reference Genome Database (https://plants.ensembl.org (accessed on 9 November 2023)). The MCScanX functional module within the TBtools v2.332 was employed to analyze the collinear relationships both within the Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata species, and among Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, Arabidopsis, and rice.

2.8. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the Promoters of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes

The 2000 bp-long sequences upstream of the transcription start sites of ACBP genes in sweet orange and trifoliate orange were selected as the promoter regions. The online tool PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ (accessed on 24 April 2024)) was utilized to retrieve all the cis-acting elements within the promoter regions of ACBP gene family members in sweet orange and trifoliate orange. Subsequently, the TBtools v2.332 was employed to generate heat maps of the identified cis-acting elements.

2.9. Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes

The sequences of ACBP gene family members in sweet orange and trifoliate orange were utilized to retrieve the expression levels of each gene member in different tissues via the online platform http://citrus.hzau.edu.cn/index.php (accessed on 28 April 2024). Subsequently, TBtools was employed to conduct a visual analysis.

2.10. Expression Analysis of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes Under Cold and Salt Stress

The specific details of the cultivation of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata plants, stress treatment procedures, and qRT-PCR experiments used in this study were identical to those described in our previously published article [25]. Seedlings were cultivated in 2 L pots filled with a substrate mixture (soil/vermiculite/perlite = 3:1:1) under controlled growth conditions. For the cold treatment, uniformly grown seedlings were transferred to a 4 °C growth chamber at the onset of the light period, during the treatment, the plants were maintained under a stable light intensity of 200 μmol/m2·s. For salt stress treatment, uniformly growing seedlings were irrigated with 150 mL of 200 mM NaCl solution once daily at a fixed time point. Control seedlings received the same volume of water on the same schedule. For all treatments, leaves were collected as the sampled tissue for subsequent RNA extraction and gene expression analysis [26]. The relative transcriptional expression level of the ACBP gene was calculated using the 2−∆∆CT method. Primers were designed using Primer Premier 5 software (https://www.premierbiosoft.com/ (accessed on 1 June 2025)), with detailed information provided in Supplementary Table S1. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism 9 (https://www.graphpad.com/ (accessed on 11 June 2025)).

2.11. Prediction of the CsACBP Family Proteins Interaction Network

To predict the proteins interaction network of the CsACBP family members, the amino acid sequences of five CsACBP family members were submitted to the STRING database (version 12.0, https://cn.string-db.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)). The analysis was restricted to Citrus sinensis to obtain predictions of species-specific interactions.

2.12. Prediction of the Candidate MiRNAs Targeting CsACBP Genes

All known citrus microRNA sequences were retrieved from miRBase (Release 21) (http://www.mirbase.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)). The CsACBPs were analyzed for the presence of miRNA target sites using the psRNATarget server (2017 Update) (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/ (accessed on 20 June 2025)) under stringent parameters: a maximum expectation value of 5.0 to minimize false positives, and a translation inhibition range set at 10–11 nucleotides.

3. Results

3.1. Identification and Chromosome Localization of the CsACBP and PtrACBP Gene Family Members

Initially, seventeen candidate proteins in Citrus sinensis and thirteen in Poncirus trifoliata were identified via Pfam conserved-domain search. Subsequently, through the BLAST search method using Arabidopsis and rice ACBPs, seventeen and twelve ACBP candidate proteins were finally confirmed in both Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata, respectively. After screening the Ankyrin and Kelch domains of overlapping candidate proteins, five ACBP gene family members were successfully identified in each of the two species. These members were named CsACBP1 to CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 to PtrACBP5 according to their chromosomal positions (Table 1). It was found that the amino acid lengths of CsACBP and PtrACBP gene family members showed a wide range, ranging from 90 to 675 amino acids. Among them, the identical protein sequence length of CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1, CsACBP2 and PtrACBP2, CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5, as well as CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 suggested that ACBPs might exhibit conservation in Citrus. The results of the subcellular localization prediction showed that all CsACBPs and PtrACBPs are localized to the nucleus, while CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 are also present in the peroxisome.

Table 1.

Characteristic Features of the ACBP Gene Family Members in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata.

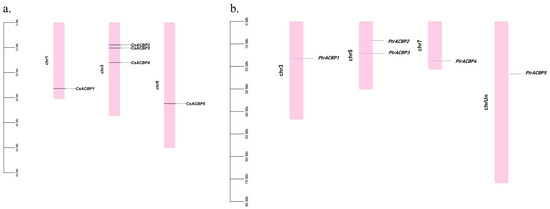

Based on citrus genome information, the distribution of ACBP family genes on chromosomes was analyzed (Figure 1). The results showed that the CsACBP genes were unevenly distributed on 3 known chromosomes. Specifically, CsACBP1 was located on chromosome 1; CsACBP2, CsACBP3, and CsACBP4 were on chromosome 3; and CsACBP5 was on chromosome 5. The PtrACBP genes were distributed on 4 known chromosomes. PtrACBP1 was located on chromosome 3; PtrACBP2 and PtrACBP3 were on chromosome 5; PtrACBP4 was on chromosome 7; and PtrACBP5 was on an unknown chromosome.

Figure 1.

Chromosome localization of the ACBP family genes in Citrus sinensis (a) and Poncirus trifoliata (b). The diagram was drawn using the TBtools software, and the five CsACBP and five PtrACBP genes were located on different chromosomes. The chromosome is depicted in pink.

3.2. The Phylogenetic Analysis of the Citrus ACBP Family Members

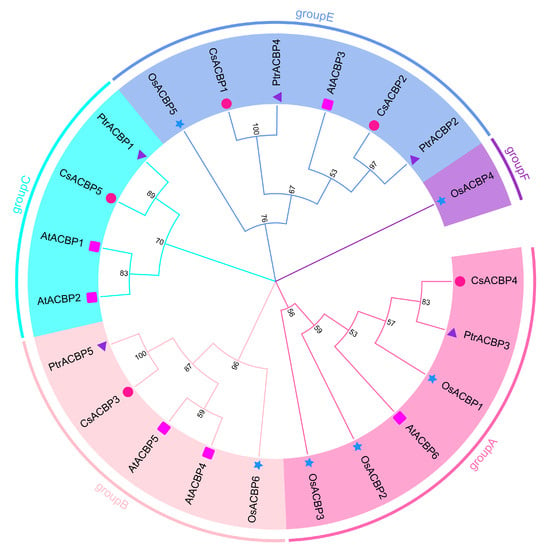

To comprehensively understand the evolutionary relationships among ACBP family members of Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, Arabidopsis, and rice, multiple sequence alignment was performed on the identified ACBP members from these species. A phylogenetic tree was constructed and visualized (Figure 2). Based on the classification criteria of ACBPs in Arabidopsis and rice, combined with the phylogenetic tree results, these genes were divided into 5 subgroups. CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 were clustered in Group A; CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 were placed in Group B; CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 were assigned to Group C; and four ACBPs (CsACBP1, CsACBP2, PtrACBP2, and PtrACBP4) were grouped into Group E. These findings indicate that the ACBP members may exhibit functional diversity in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the ACBP family proteins from Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. The MEGA 11 software was used to generate the unrooted tree using the full-length amino acid sequences of ACBP family members from Arabidopsis thaliana (At), Oryza sativa (Os), Citrus sinensis (Cs), and Poncirus trifoliata (Ptr) by the maximum likelihood method with 1000 replications. The CsACBPs and PtrACBPs were classified into 4 families (Group A–E), with each subfamily indicated by different colors. CsACBPs, PtrACBPs, AtACBPs, and OsACBPs are indicated by red circles, purple triangles, pink squares, and blue stars, respectively.

3.3. Gene Structure and Protein Conserved Motif Analysis of the Citrus ACBP Family Members

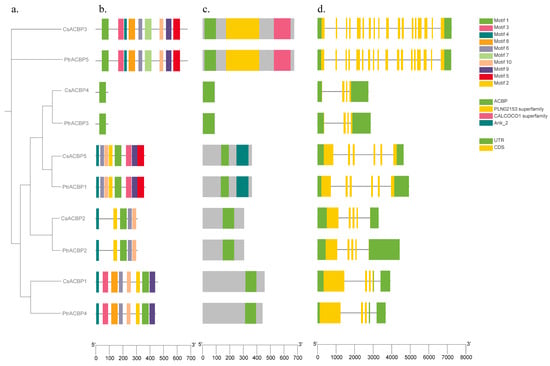

To further investigate the gene structure and evolutionary relationships of the citrus ACBP gene family, the structural characteristics and conserved motifs of the ACBP gene families in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were analyzed using the MEME web server (Figure 3). Motif analysis revealed that the ACBPs of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata contained 1 to 10 motifs. Specifically, CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 harbored only one identical motif, namely Motif 1. CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 contained 8 types of motifs, excluding Motif 7 and Motif 8. CsACBP2 and PtrACBP2 shared 5 identical motifs, which were Motif 1, Motif 2, Motif 4, Motif 6, and Motif 10. CsACBP1 and PtrACBP4 contained 8 types of motifs except Motif 5 and Motif 7, while CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 shared 9 identical motifs excluding Motif 2.

Figure 3.

Gene structure and conserved motifs of the ACBP family members in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. (a) The phylogenetic tree of ACBPs. (b) Conserved motif distributions of ACBPs. (c) Domain’s analysis of ACBPs. (d) Exon-intron distributions of ACBPs.

Examination of the visualization of conserved domains showed that CsACBP1, CsACBP2, CsACBP4, PtrACBP2, PtrACBP3, and PtrACBP4 shared one and the same conserved domain, the ACB domain. In addition, CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 contained two identical conserved domains, whereas CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 possessed three identical conserved domains. Gene structure analysis indicated that members of the ACBP gene family contained 3 to 18 exons, with significant differences in gene structure and exon number. Among them, CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 had the highest number of exons, both containing 18 exons. CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 each contained 6 exons; CsACBP2 and PtrACBP2 each contained 5 exons; and CsACBP1, PtrACBP4, CsACBP4, and PtrACBP3 had the lowest number of exons, with 4 exons each. Meanwhile, the differences observed among introns also suggest that the phylogeny of citrus ACBP family members is closely associated with their gene structures.

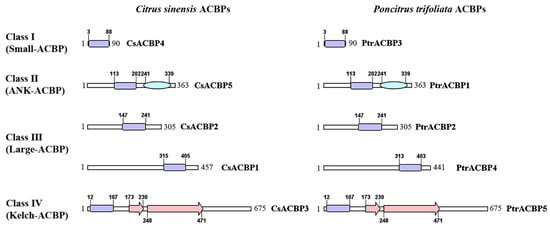

3.4. The Protein Domains Analysis of the Citrus ACBP Family Members

To gain deeper insights into the protein structure of citrus ACBP family members, we generated the primary protein structure diagrams of CsACBPs and PtrACBPs. Based on amino acid sequence length and domain composition, a total of 10 ACBPs from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were classified into 4 subfamilies (Figure 4). All ACBPs contained the ACB domain, while some also possessed Ankyrin domains or Kelch domains. CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 only harbored the ACB domain, with amino acid lengths less than 155 residues, thus being assigned to Small-ACBPs in Class I. In addition to the ACB domain, CsACBP5 and PtrACBP1 had an ankyrin-repeat domain at positions 241–339, leading to their classification into ANK-ACBPs in Class II. CsACBP1, CsACBP2, PtrACBP2, and PtrACBP4 contained only the ACB domain and had amino acid lengths exceeding 215 residues, so they were categorized into Large-ACBPs in Class III. Finally, besides the N-terminal ACB domains, CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 contained a Kelch domain at positions 173–230 and 248–471, respectively, resulting in their assignment to Kelch-ACBPs in Class IV.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the protein domains of ACBP derived from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. Purple represents the acyl-CoA binding domain (ACB), blue represents the ankyrin repeat domain (ANK), and pink represents the Kelch domain (Kelch).

3.5. Secondary Structure Prediction Analysis of the Citrus ACBPs

In addition to the above analysis of primary structures, we also conducted analyses of protein secondary structures, tertiary structures, and phosphorylation sites, revealing that CsACBPs predominantly consist of three secondary structures—alpha-helix (α-helix), extended strands, and random coils—and β-sheets are not observed in their structural composition (Table 2). Except for the CsACBP3 and CsACBP5, which showed a structural distribution pattern of α-helix > random coil > extended strand, the CsACBP3 and CsACBP5 proteins exhibited a consistent pattern: random coil > α-helix > extended strand. Among them, CsACBP5 had the highest proportion of random coils at 55.10%, while CsACBP1 had the lowest at 32.17%. In contrast, CsACBP1 had the highest proportion of α-helices (66.30%), whereas CsACBP3 had the lowest proportion of α-helices (34.96%).

Table 2.

Structural Characteristics of ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata.

The protein secondary structures of the PtrACBP members showed a similar phenomenon to that of the CsACBP members (Table 2). Alpha-helix, extended strands, and random coils constituted the main secondary structural elements of PtrACBPs, whereas β-sheets were absent. Except for the PtrACBP1 and PtrACBP5, which showed a structural distribution pattern of α-helix > random coil > extended strand, the PtrACBP1 and PtrACBP5 proteins exhibited a consistent pattern: random coil > α-helix > extended strand. Among them, PtrACBP5 had the highest proportion of random coils at 54.67%, while PtrACBP4 had the lowest at 28.80%. In contrast, PtrACBP4 had the highest proportion of α-helices (69.84%), whereas PtrACBP5 had the lowest proportion of α-helices (31.85%).

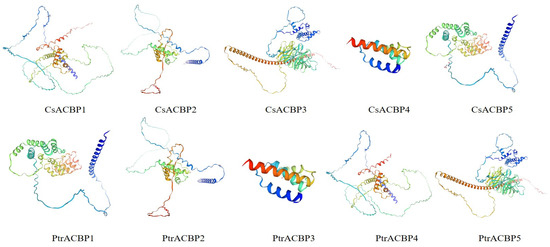

3.6. Phosphorylation Site and Tertiary Structure Prediction Analysis of the Citrus ACBPs

Phosphorylation site prediction for CsACBPs and PtrACBPs indicated that serine and threonine residues were the most frequently phosphorylated, while lysine residues were the least common (Table 2). Tertiary structure analysis indicated that ACBP members exhibited low structural similarity within their respective species (Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata), while conservation was observed between ACBP members of these two species (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tertiary structure of the ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. A blue-to-red color gradient (blue-green-yellow-red) is used to depict the polypeptide chain from the N- to the C-terminus.

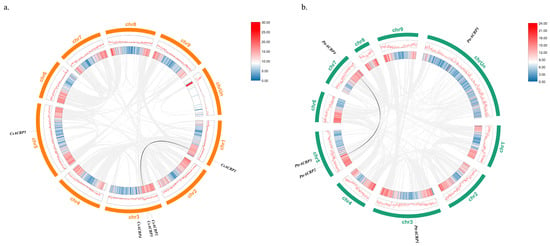

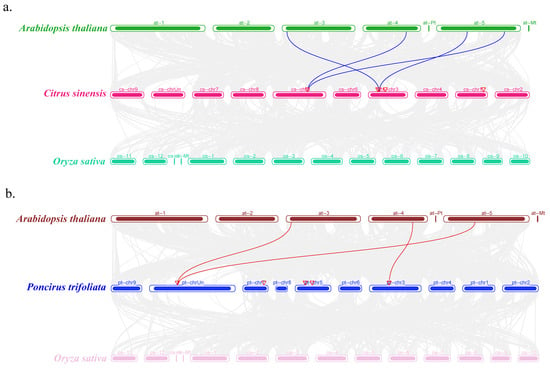

3.7. Intraspecific Collinearity Analysis of the Citrus ACBP Genes

To explore the evolution among genes of the CsACBP and PtrACBP families, collinearity analysis was performed. As shown in Figure 6, the results of intraspecific collinearity analysis revealed that there was one pair of collinear relationships among ACBP genes in both Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata, namely CsACBP1 with CsACBP2, and PtrACBP2 with PtrACBP4.

Figure 6.

Collinearity analysis of ACBP genes within species: Citrus sinensis (a) and Poncirus trifoliata (b). The gray lines represent all collinear gene pairs in the genomes of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. The black lines represent the collinearity relationships among ACBP genes. Chr represents different chromosomes. Red and blue represent the levels of gene distribution density on the chromosomes. The darker the color, the higher the gene density.

3.8. Collinearity Analysis of the ACBP Genes Among Different Species

To further clarify the evolutionary relationships and phylogenetic status of ACBP genes among Citrus sinensis, Poncirus trifoliata, and the model plants Arabidopsis and rice, collinearity analysis was conducted across these species (Figure 7). The results showed that there were 4 pairs of collinear relationships between ACBP genes of Citrus sinensis and Arabidopsis, and 3 pairs of collinear relationships between those of Poncirus trifoliata and Arabidopsis. However, no collinear relationships were observed between ACBP genes of Citrus sinensis or Poncirus trifoliata and rice. These findings indicated that these ACBP genes are more closely related to those in Arabidopsis, and the collinear gene pairs may originate from a common ancestor and thus potentially exhibit similar functions.

Figure 7.

Collinearity analysis of the ACBP genes in Citrus sinensis (a) and Poncirus trifoliata (b), respectively, with those in other species. The gray lines in the background represent the collinear blocks among the genomes of different plants. The two species are Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa, respectively.

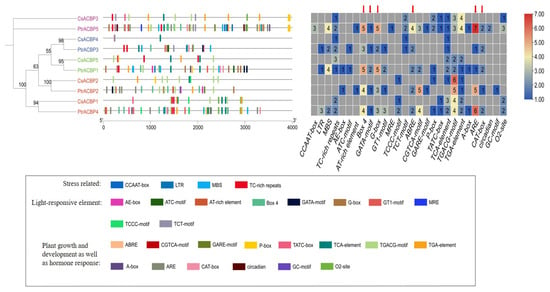

3.9. Cis-Acting Elements Analysis of the Citrus ACBP Gene Promoters

To investigate the biological pathways involving the citrus ACBP gene family, cis-acting elements in the promoter sequences of citrus ACBP genes were predicted (Figure 8). As shown in Figure 8, a total of 28 types of cis-acting elements were predicted in the promoter regions of ACBP genes from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. Based on their functions, these elements were classified into four categories: stress-responsive elements, light-responsive elements, hormone regulation-related elements, and plant growth and development-related elements. Among these ACBP gene members, CsACBP4 contained only 3 cis-acting elements, representing the minimum number of elements among all ACBP members, while PtrACBP5 had the maximum number of cis-acting elements, with a total of 58. Notably, the number of promoter elements in each PtrACBP gene member was higher than that in CsACBP counterparts. Additionally, five specific elements, which are involved in light response, growth and development, and hormone response, were observed to be present only in the promoters of PtrACBP genes, but absent in those of CsACBP genes. These results suggest that CsACBP and PtrACBP genes may be involved in responding to environmental stresses and are regulated to varying degrees during plant growth and development.

Figure 8.

Prediction map of cis-acting elements of ACBP gene promoters in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. Cis-elements were predicted based on the 2000 bp region upstream of the transcription start site. The scale bar at the bottom indicates the length of the promoter sequence. The red arrow points to the regulatory elements that exist only in the ACBP gene promoters of Poncirus trifoliata but are absent from those of Citrus sinensis. In the right-hand image, the color transitions from blue to yellow and then to red, showing the quantity of different types of elements in each gene. The bottom figure shows the functional classification of different cis-regulatory elements. Different colors in the bottom figure represent different cis-regulatory elements.

3.10. Tissue-Specific Expression of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes

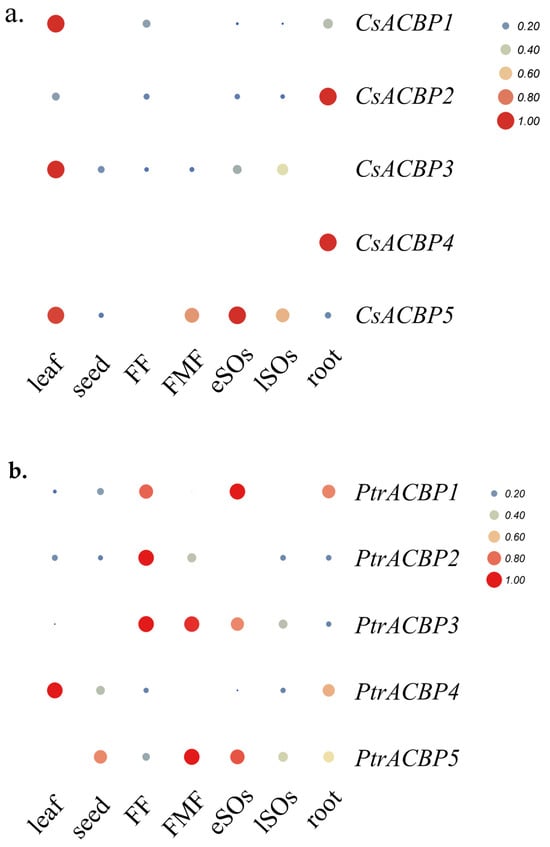

To clarify the tissue-specific expression patterns of citrus ACBP genes, the expression profiles of ACBP gene family members from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were analyzed in leaves, seeds, young fruit pulp, mature fruit pulp, early-stage ovules, late-stage ovules, and roots (Figure 9). In Citrus sinensis, CsACBP1 and CsACBP3 were predominantly highly expressed in leaves, while CsACBP2 and CsACBP4 showed high expression mainly in roots. CsACBP5 was strongly expressed in the early-stage ovules, with secondary high expression in leaves. In Poncirus trifoliata, PtrACBP1 was predominantly highly expressed in the early-stage ovules, and PtrACBP2 exhibited high expression mainly in young fruit pulp. PtrACBP3 was expressed in both young and mature fruit pulp, while PtrACBP4 was highly expressed primarily in leaves. PtrACBP5 was mainly expressed in mature fruit pulp, followed by secondary expression in the early-stage ovules. These differential expression results indicate that members of the citrus ACBP gene family may play important roles at one or several specific stages of plant growth and development. Moreover, the homologous gene pairs of CsACBPs and PtrACBPs exhibited distinct tissue expression patterns, suggesting that they may have certain functional differences in regulating plant development.

Figure 9.

Expression patterns of ACBPs in different tissues and organs of Citrus sinensis (a) and Poncirus trifoliata (b). A color gradient from blue to red indicates a sequential increase in expression levels. FF: flesh of young fruit; FMF: flesh of mature fruit; eSOs: early-stage ovules; lSOs: late-stage ovules.

3.11. Expression Patterns Analysis of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes in Response to Low-Temperature Stress

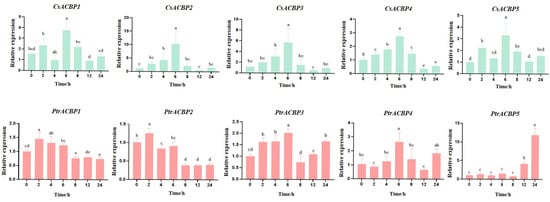

To elucidate the response of citrus ACBP gene members to low-temperature stress, we analyzed the expression patterns of CsACBP and PtrACBP genes under low-temperature treatment using the qRT-PCR method (Figure 10). As shown in Figure 10, all ACBP gene members in Citrus sinensis generally exhibited an expression pattern of first increasing and then decreasing, with their expression levels peaking at 6 h of low-temperature treatment. Among these genes, the expression level of CsACBP3 at 6 h was significantly higher than that of other members. In contrast, there were differences in the expression of ACBP gene members in Poncirus trifoliata. PtrACBP1 and PtrACBP2 showed a significant upregulation in expression at 2 h of low-temperature treatment, followed by a gradual downregulation, and their expression tended to stabilize from 8 h onward. The expression of PtrACBP3 and PtrACBP4 generally showed a trend of first increasing, then decreasing, and then increasing again, with the expression peak at 6 h. For PtrACBP5, it showed no response to low temperature from 0 to 8 h; it began to respond at 12 h, and its expression level increased significantly at 24 h. These findings indicate that citrus ACBPs can all respond to low-temperature stress.

Figure 10.

Expression patterns of ACBP genes in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata under low-temperature stress. Different letters indicate significant difference (ANOVA analysis, p < 0.05).

3.12. Expression Patterns Analysis of CsACBP and PtrACBP Genes in Response to Salt Stress

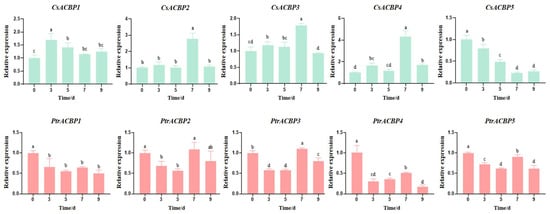

To investigate the role of citrus ACBP gene members in salt stress response, we analyzed their expression patterns under salt stress using the RT-qPCR method (Figure 11). In general, ACBP gene members from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata exhibited opposite expression patterns under salt treatment. In Citrus sinensis, except for CsACBP5, whose expression was inhibited, the other four CsACBP members generally showed an expression trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The expression of CsACBP1 peaked on day 3, while CsACBP2, CsACBP3, and CsACBP4 all reached their expression peaks on day 7; among these, CsACBP4 had the highest expression level on day 7. In contrast, in Poncirus trifoliata, most PtrACBP genes were transcriptionally inhibited under salt stress, with the exception of PtrACBP3. PtrACBP3 displayed an expression pattern of first decreasing, then increasing, and then decreasing again, showing a slight upregulation on day 7. These results collectively indicate that citrus ACBP genes can respond to salt stress to varying extents. Furthermore, most homologous gene pairs between CsACBPs and PtrACBPs may exert distinct, or even opposing, regulatory roles under salt stress conditions.

Figure 11.

Expression patterns of ACBP genes in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata under salt stress. Different letters indicate significant difference (ANOVA analysis, p < 0.05).

3.13. Prediction Analysis of the ACBP Family Proteins Interaction Network in Citrus sinensis

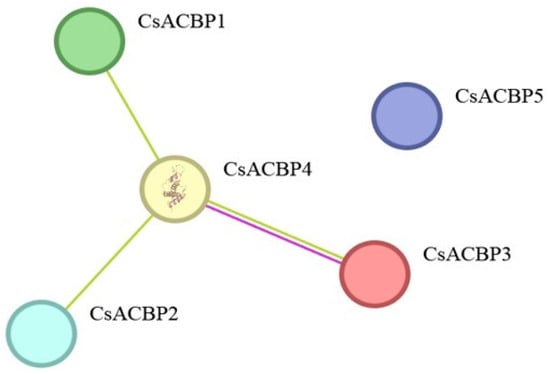

Protein–protein interactions are central to understanding the molecular mechanisms of gene families, as many proteins exert biological functions through dimerization or multimeric complex formation. Therefore, for the purpose of exploring the potential associations between CsACBP members, the protein–protein interaction network was predicted (Figure 12). The prediction results revealed that, with the exception of CsACBP5, tight interactions were predicted among CsACBP1, CsACBP2, CsACBP3, and CsACBP4, suggesting their potential functional cooperation within similar biological pathways.

Figure 12.

Interaction network of the CsACBP family members. Greater line density indicates stronger relationships.

3.14. The Candidate miRNAs Targeting CsACBP Genes

To investigate additional potential regulatory mechanisms of ACBP genes in Citrus sinensis, five transcripts from Citrus sinensis were analyzed for the presence of potential miRNA target sites. All known citrus miRNAs from the miRBase database were used as query sequences to predict target sites on the CsACBP genes. Among the five ACBP transcripts, CsACBP1, CsACBP2, and CsACBP3 were predicted to be targets of csi-miR3952, csi-miR396a, and csimiR477b, respectively (Table 3). No potential miRNA targets were detected for CsACBP4 and CsACBP5 (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of CsACBP Genes with Putative miRNA Target Sites.

4. Discussion

Plant ACBPs are a class of small proteins with a molecular weight of 10 kDa, exhibiting high specificity and affinity for acyl-CoA [27,28]. They are evolutionarily conserved, widely present in eukaryotes [29], and involved in various biological processes. However, genome-wide analysis of the ACBP gene family in citrus, one of the world’s major fruit crops, has not yet been reported.

In this study, a total of 5 ACBP gene members were identified in each of the genomes of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. The small size of the identified ACBP family suggests that gene duplication events of the ACBP family have rarely occurred in the genomes of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. The number of ACBP gene members in these two citrus species is lower than that in soybean [21,30], rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) [31], peanut (Arachis hypogaea) [32], and grape, but higher than that in barrel clover (Medicago truncatula), cocoa (Theobroma cacao), papaya (Carica papaya), cucumber [2,29], and tung tree (Vernicia fordii) [33]. The ACBP gene members of Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata were classified into four subfamilies, which is consistent with the classification of ACBP members in most plant species. However, some species possess an additional fifth subfamily, namely Class 0 [2], which has a structural similarity to Class III but contains fewer amino acid residues.

In Brassica napus, Small-ACBPs and Kelch motif-containing BnACBPs are localized in the cytoplasm, while ankyrin repeat-containing ACBPs and Large-ACBPs are secretory proteins localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [34]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, AtACBP4, AtACBP5, and AtACBP6 are localized in the cytoplasmic solute; they function in transferring oleoyl-CoA esters from plastids to the ER [35]. After translocation, AtACBP6 interacts with membrane-bound PDL8 at the plasma membrane [36]. In rice, OsACBP5 is localized in the apoplast [37], and OsACBP6 interacts with ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters on peroxisomes [38]. Since the subcellular localization of ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata remains unclear, we predicted the localization of all CsACBPs and PtrACBPs using the Plant-mPLoc online tool in this study; the results showed that all these ACBPs are localized in the nucleus. Thus, we hypothesize that they may possess transcriptional regulatory functions [39]. Notably, the Small-ACBPs CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 are also predicted to be present in peroxisomes. Lipids are mostly stored in the form of triacylglycerols (TAGs), and esterified fatty acids (FAs) released from TAGs enter the β-oxidation cycle via peroxisomes, where they are decomposed into acetyl-CoA, which ultimately contributes to carbohydrate formation [40,41]. Based on this, we speculate that Small-ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata may also be involved in the oxidative decomposition of FAs [42]. However, both hypotheses mentioned above require further experimental verification.

The ACBP gene family is unevenly distributed across chromosomes in both Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. CsACBP members are only distributed on Chr1, Chr3, and Chr5, while PtrACBP members are restricted to Chr3, Chr5, Chr7, and one unknown chromosome; no ACBP genes were detected on the remaining six chromosomes in either species. This distribution pattern is similar to that of ACBP genes in cotton, where ACBP genes are also unevenly distributed across chromosomes, with most localized to the terminal regions of chromosomes [43]. The gene structures of CsACBP and PtrACBP are associated with their subfamily classification. CsACBP4 and PtrACBP3 (Class I) and CsACBP1 and PtrACBP4 (Class III) contain 4 exons, representing the subfamilies with the fewest exons. In contrast, CsACBP3 and PtrACBP5 (Class IV) contain 18 exons, making them the subfamily with the most exons. This result is consistent with findings in maize, where Class IV Kelch-ACBPs also contain the highest number of exons, with 18 exons [20].

To further understand the gene functions and regulatory patterns of ACBPs in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata, we predicted the cis-acting elements in the promoters of ACBP genes from these two species. A comparative analysis of these promoter cis-acting elements revealed an interesting phenomenon: five specific elements—those involved in light response, growth and development, and hormone response—were exclusively present in the promoters of PtrACBP genes but absent in those of CsACBP genes. This suggests that ACBPs may have distinct regulatory mechanisms in growth, development, and environmental adaptation between the two citrus species. However, the specific nature of these regulatory mechanisms and whether they are truly divergent require further investigation in future studies. Additionally, we observed that homologous ACBP gene pairs from Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata exhibit distinct tissue-specific expression patterns. This implies that these homologous genes might have specific functional differences in the regulation of plant organ development, which also constitutes a direction that merits in-depth investigation.

Most ACBP genes respond to various abiotic stresses and influence plant stress tolerance. For example, overexpression of ZmACBP1 and ZmACBP3 from maize significantly enhances the tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana to NaCl and mannitol treatments [20]. Overexpression of RpACBP3 from black locust improves tolerance to Plumbum stress by regulating the expression of LOX genes and increasing phosphatidylcholine (PC) content, which in turn enhances the ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) and repair cell membranes under stress [44]. In this study, all identified ACBP genes were found to respond to low-temperature and salt stresses, exhibiting dynamic and member-specific response patterns. Interestingly, although PtrACBP5 did not respond to low temperature as rapidly as other members, its expression level increased significantly after 24 h of low-temperature treatment. This suggests that PtrACBP5 may play an important role under prolonged low-temperature conditions. In future studies, PtrACBP5 could be selected as a key candidate gene to further investigate its biological functions and molecular mechanisms under cold stress. It should be noted that the 200 mM NaCl treatment used in this study (approximately −0.96 MPa osmotic potential) induces both ionic and osmotic stress components. While this approach effectively triggers plant stress responses, it does not allow for clear distinction between the specific effects of Na+ toxicity and general osmotic stress. Future studies incorporating parallel treatments with KCl or osmoticums such as mannitol would be valuable to dissect these distinct stress components.

Currently, the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of ACBPs in stress responses have been reported in several other plant species. For instance, in Arabidopsis thaliana, RAP2.12 interacts with AtACBP1 and AtACBP2 at the plasma membrane under aerobic conditions; upon hypoxia, RAP2.12 is translocated to the nucleus to activate the transcription of hypoxia-responsive genes [45]. However, the molecular mechanisms of citrus ACBPs in stress responses remain unclear. In this study, we explored the potential molecular mechanisms of ACBPs in Citrus sinensis. We found that protein–protein interactions existed among most CsACBP members, with the exception of CsACBP5. Additionally, upstream small RNAs were predicted for three CsACBP gene members. Among the three predicted miRNAs, miR396 is the most extensively studied [46]. Its primary function involves targeting GRF (Growth-Regulating Factor) genes—key regulators of cell proliferation and organ size. Given miR396’s role in GRF-mediated cell proliferation, we infer that CsACBP2 may act as a link between lipid metabolism and organ size control in Citrus. In future studies, we will conduct experimental validation of the predicted protein–protein interactions and the small RNAs targeting ACBP genes, and further investigate other potential molecular regulatory mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a systematic genome-wide identification and analysis of ACBP genes was performed in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata. A total of 5 ACBP members were identified in each species, which were further classified into four subfamilies. We analyzed the protein structure, motifs, conserved domains, gene structure, phylogenetic tree, collinearity, cis-acting elements, and tissue-specific expression differences in these ACBP genes. Among these analyses, cis-acting element analysis indicated that ACBP genes may respond to various hormone signals and environmental stresses, including light responses, methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-mediated regulation, and abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated regulation. The differential expression of ACBP genes across different citrus species and tissues reflects gene diversity and species-specific expression characteristics. The expression profiles under low-temperature and salt stress conditions showed that all ACBP genes could respond to these two stresses, exhibiting dynamic and member-specific response patterns. This suggests that ACBP members may be involved in regulating the cold and salt stress tolerance mechanisms of citrus to varying degrees. Furthermore, we preliminarily predicted the potential protein–protein interaction networks of ACBP gene family members and their potential upstream small RNAs in Citrus sinensis. In conclusion, this study represents the first comprehensive analysis of ACBP genes in Citrus sinensis and Poncirus trifoliata, laying a foundation for further investigations into the biological functions and molecular mechanisms of ACBP genes in these two citrus species.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agriculture15242547/s1, Table S1. Primers for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay.

Author Contributions

Methodology and software, L.J.; collection and analysis of the bibliography, L.J. and X.W.; validation, L.J. and X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, L.J. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and Y.S.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20230571); the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M742962); and the Key Research and Development Program of Jiangsu Province (BE2023328).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hurlock, A.K.; Roston, R.L.; Wang, K.; Benning, C. Lipid Trafficking in Plant Cells. Traffic 2014, 15, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Su, Y.C.; Saunders, R.M.; Chye, M.L. The rice acyl-CoA-binding protein gene family: Phylogeny, expression and functional analysis. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 1170–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Chye, M.L. Membrane localization of Arabidopsis acyl-CoA binding protein ACBP2. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003, 51, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chye, M.L.; Li, H.Y.; Yung, M.H. Single amino acid substitutions at the acyl-CoA-binding domain interrupt 14[C]palmitoyl-CoA binding of ACBP2, an Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein with ankyrin repeats. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 44, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aznar-Moreno, J.A.; Venegas-Calerón, M.; Du, Z.Y.; Garcés, R.; Tanner, J.A.; Chey, M.L.; Martínez-Force, E.; Salas, J.J. Characterization of a small acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) from Helianthus annuus L. and its binding affinities. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikova, D.N.; Finkina, E.I.; Bogdanov, I.V.; Tagaev, A.A.; Ovchinnikova, T.V. Features and Possible Applications of Plant Lipid-Binding and Transfer Proteins. Membranes 2023, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Lung, S.C.; Fadhli Hamdan, M.; Chye, M.L. Interactions between plant lipid-binding proteins and their ligands. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Chan, W.H.Y.; Kong, G.K.W.; Hao, Q.; Chye, M.L. The first plant acyl-CoA-binding protein structures: The close homologues OsACBP1 and OsACBP2 from rice. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2017, 73, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Chye, M.L. An Arabidopsis family of six acyl-CoA-binding proteins has three cytosolic members. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.C.; Li, H.Y.; Mishra, G.; Chye, M.L. ACBP4 and ACBP5, novel Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding proteins with kelch motifs that bind oleoyl-CoA. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 55, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.Y.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.F.; Chey, M.L. Depletion of the membrane-associated acyl-coenzyme A-binding protein ACBP1 enhances the ability of cold acclimation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1585–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Chen, Q.F.; Chye, M.L. Trans genic Arabidopsis flowers overexpressing acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP6 are freezing tolerant. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.Y.; Chen, M.X.; Chen, Q.F.; Xiao, S.; Chye, M.L. Overexpression of Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP2 enhances drought tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2013, 36, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.J.; Yu, L.J.; Chen, Q.F.; Wang, F.Z.; Huang, L.; Xia, F.N.; Zhu, T.R.; Wu, J.X.; Yin, J.; Liao, B.; et al. Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP3 participates in plant response to hypoxia by modulating very-long-chain fatty acid metabolism. Plant J. 2015, 81, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.H.; Lung, S.C.; Ye, Z.W.; Chye, M.L. Depletion of Arabidopsis Acyl-CoA-binding protein 3 affects fatty acid composition in the Phloem. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.; Gao, W.; Chen, Q.F.; Chan, S.W.; Zheng, S.X.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; Welti, R.; Chye, M.L. Overexpression of Arabidopsis acyl-CoA binding protein ACBP3 promotes starvation-induced and age-dependent leaf senescence. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 1463–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yu, K.; Gao, Q.M.; Wilson, E.V.; Navarre, D.; Kachroo, P.; Kachroo, A. Acyl CoA binding proteins are required for cuticle formation and plant responses to microbes. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.Y.; Yao, Y.J.; Yin, K.Q.; Tan, L.N.; Liu, M.; Hou, J.; Zhang, H.; Liang, R.Y.; Zhang, X.R.; Yang, H.; et al. ACBP4-WRKY70-RAP2.12 module positively regulates submergence-induced hypoxia response in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Xu, L.J.; Du, Z.Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, R.; Song, X.S.; Lam, S.M.; Shui, G.H.; Li, Y.H.; Chye, M.L. Rice acyl-CoA-binding protein6 affects acyl-CoA homeostasis and growth in rice. Rice 2020, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.T.; Li, W.J.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Pei, L.M.; Liu, J.J.; Xia, X.Y.; Che, R.H.; Li, H. Molecular characterization, expression and functional analysis of acyl-CoA-binding protein gene family in maize (Zea mays). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, S.C.; Lai, S.H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, A.; Guo, Z.H.; Lam, H.M.; Chye, M.L. Oxylipin signaling in salt-stressed soybean is modulated by ligand-dependent interaction of Class II acyl-CoA-binding proteins with lipoxygenase. Plant Cell. 2022, 34, 1117–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminara, S.; Bennici, S.; Di Guardo, M.; Caruso, M.; Gentile, A.; La Malfa, S.; Distefano, G. Sweet orange: Evolution, Characterization, Varieties, and Breeding Perspectives. Agriculture 2023, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.Z.; Xie, Y.B.; Ma, J.Y.; Luo, X.T.; Nie, P.; Zuo, Z.X.; Lahrmann, U.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Y.Y.; Zhao, Y.; et al. IBS: An illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3359–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.J.; Sheng, Y.; Song, C.Y.; Liu, T.; Sheng, S.Y.; Xu, X.Y. Identification of Chalcone Synthase Genes and Their Responses to Salt and Cold Stress in Poncirus trifoliata. Plants 2025, 14, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Hu, J.; Dahro, B.; Ming, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Alhag, A.; Li, C.; Liu, J.H. ERF108 from Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf. functions in cold tolerance by modulating raffinose synthesis through transcriptional regulation of PtrRafS. Plant J. 2021, 108, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kragelund, B.B.; Poulsen, K.; Andersen, K.V.; Baldursson, T.; Krøll, J.B.; Neergård, T.B.; Jepsen, J.; Roepstorff, P.; Kristiansen, K.; Poulsen, F.M.; et al. Conserved residues and their role in the structure, function, and stability of acyl-coenzyme A binding protein. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 2386–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neess, D.; Bek, S.; Engelsby, H.; Gallego, S.F.; Færgeman, N.J. Long-chain acyl-CoA esters in metabolism and signaling: Role of acyl-CoA binding proteins. Prog. Lipid Res. 2015, 59, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.Y.; Arias, T.; Meng, W.; Chye, M.L. Plant acyl-CoA-binding proteins: An emerging family involved in plant development and stress responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 63, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboanatahiry, N.; Wang, B.S.; Yu, L.J.; Li, M.T. Functional and structural diversity of acyl-CoA binding proteins in oil crops. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Wu, C.T.; Li, Y.; Kang, G.J.; Qin, H.D.; Zeng, R.Z. Acyl-CoA-binding protein family members in laticifers are possibly involved in lipid and latex metabolism of Hevea brasiliensis (the Para rubber tree). BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Li, L.Y.; Lin, L.F.; Xie, H.; Zheng, Y.X.; Wan, X.R. Genome-wide identification of acyl-CoA binding proteins and possible functional prediction in legumes. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1057160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, S.; Sethumadhavan, K.; Ullah, A.H.; Gidda, S.; Cao, H.; Mason, C.; Chapital, D.; Scheffler, B.; Mullen, R.; Dyer, J.; et al. Molecular properties of the class III subfamily of acyl-coenyzme A binding proteins from tung tree (Vernicia fordii). Plant Sci. 2013, 203–204, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raboanatahiry, N.H.; Lu, G.; Li, M. Computational prediction of acyl-CoA binding proteins structure in Brassica napus. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.W.; Chye, M.L. Plant Cytosolic Acyl-CoA-Binding Proteins. Lipids 2016, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.W.; Chen, Q.F.; Chye, M.L. Arabidopsis thaliana Acyl-CoA-binding protein ACBP6 interacts with plasmodesmata-located protein PDLP8. Plant Signal Behav. 2017, 12, e1359365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, P.; Leung, K.P.; Lung, S.C.; Panthapulakkal Narayanan, S.; Jiang, L.; Chye, M.L. Subcellular Localization of Rice Acyl-CoA-Binding Proteins ACBP4 and ACBP5 Supports Their Non-redundant Roles in Lipid Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, L.J.; Gao, Y.; He, M.L.; Bu, Q.Y.; Meng, W. Phylogeny and subcellular localization analyses reveal distinctions in monocot and eudicot class IV acyl-CoA-binding proteins. Planta 2021, 254, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.Y.; Xiao, S.; Chye, M.L. Ethylene-and pathogen-inducible Arabidopsis acyl-CoA-binding protein 4 interacts with an ethylene-responsive element binding protein. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 59, 3997–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li-Beisson, Y.; Shorrosh, B.; Beisson, F.; Andersson, M.X.; Arondel, V.; Bates, P.D.; Baud, S.; Bird, D.; Debono, A.; Durrett, T.P.; et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arab. Book 2013, 11, e0161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, I.A. Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, M.F.; Lung, S.C.; Guo, Z.H.; Chye, M.L. Roles of acyl-CoA-binding proteins in plant reproduction. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2918–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Z.; Fu, M.C.; Li, H.; Wang, L.G.; Liu, R.Z.; Liu, Z.J. Molecular Characterization of the Acyl-CoA-Binding Protein Genes Reveals Their Significant Roles in Oil Accumulation and Abiotic Stress Response in Cotton. Genes 2023, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.y.; Die, P.X. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals the Mechanism by Which RpACBP3 Overexpression Contributes to the Response of Robinia pseudoacacia to Pb Stress. Plants 2024, 13, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.H.; Chye, M.L. Plant Acyl-CoA-Binding Proteins-Their Lipid and Protein Interactors in Abiotic and Biotic Stresses. Cells 2021, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebsch, D.; Palatnik, J.F. MicroRNA miR396, GRF transcription factors and GIF co-regulators: A conserved plant growth regulatory module with potential for breeding and biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2020, 53, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).