1. Introduction

With the scale development of agriculture in China, the demand for automatic navigation operations of agricultural machinery is increasing, and the multi-machine collaboration mode has become a key focus in agricultural machinery navigation research [

1]. Tractors are central power machinery in modern agriculture, utilized in various operations such as plowing, sowing, harvesting, and plant protection. Compared to traditional single-tractor operations, multi-machine collaborative navigation requires less time to complete the same workload, resulting in higher operational efficiency. Additionally, it enables simultaneous execution of multiple tasks, significantly reducing the demand for labor and alleviating the problem of declining rural workforce.

At present, most multi-machine collaborative navigation systems for agricultural machinery rely on satellite navigation systems. However, the high costs associated with base stations for high-precision RTK, centimeter-level satellite navigation modules, and multi-machine communication modules, coupled with the inability of absolute satellite positioning to meet the obstacle avoidance requirements in field operations, pose significant challenges. This study focuses on a vision-based relative positioning method for agricultural machinery, enabling real-time recognition and positioning of the leader tractor in the operating queue, thereby providing perceptual information for the autonomous following of the rear tractor.

1.1. Related Work

1.1.1. Vision-Based Agricultural Object Recognition

Object recognition based on traditional vision has been widely applied in agriculture [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Cubero et al. utilized machine vision for sorting and grading citrus fruits. By using RGB images, they segmented the citrus from the background and calculated the area of the oranges to determine their size, then graded them based on citrus color indices [

6]. Campos et al. captured video of the cornfield environment using cameras mounted on a tractor and proposed an automatic obstacle analysis strategy based on spatiotemporal analysis. The method first detects obstacles using spatial information derived from spectral analysis and textural data, then employs temporal information to identify moving objects in the field. Experiments demonstrated that this strategy can effectively detect both static and dynamic obstacles in agricultural environments [

7]. Peng et al. addressed the issue of slow recognition speed and low accuracy for litchi identification in outdoor environments by proposing a multi-target rapid identification method based on dual Otsu algorithm. This approach separately segments the background, fruit stems, and fruits in field environment images. Field experiments demonstrated that the recognition time of this method is less than 0.2 s, meeting the rapid identification requirements for harvesting robots [

8]. Lv et al. studied a rapid tracking and identification method for apples. They combined the R-G color difference feature with the Otsu dynamic threshold segmentation method to segment apples in the first frame image, and applied template matching to track and identify apple targets in subsequent frames [

9]. Traditional vision extracts limited object feature information, especially in complex field environments where factors such as variations in lighting, object morphology, and crop occlusion can affect feature extraction, resulting in relatively low accuracy in object recognition.

Deep learning algorithms can effectively address the limitations of traditional visual object recognition and have gradually become a research focus for many scholars [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Kang et al. proposed an improved deep neural network named DaSNet-v2, capable of performing apple recognition and instance segmentation, as well as semantic segmentation of branches. Field experiments demonstrated that DaSNet-v2 achieved a model size of 8.1 M and an inference time of 54 ms on a GTX-1080ti GPU, with fruit and branch segmentation accuracies reaching 86.6% and 75.7%, respectively [

16]. Yu et al. proposed a visual recognition method for strawberries, utilizing ResNet50 as the backbone network combined with a feature pyramid network (FPN) architecture for feature extraction. Test results demonstrated an average accuracy of 95.78%, a recall rate of 95.41%, and a mean intersection over union (mIoU) of 89.85% for instance segmentation [

17]. Wang et al. proposed a blueberry recognition network incorporating an attention module (I-YOLOv4-Tiny), which integrates a convolutional attention module into the feature pyramid of YOLOv4-Tiny. Validation results demonstrated a mean recognition accuracy of 96.24%, with a model size of only 24.20 MB [

18]. Tang et al. targeted multiple pests during the growth of tomato plants and proposed an enhanced insect detection model named S-YOLOv5m. This model integrates the SPD-Conv module, Ghost module, CBAM attention mechanism and AEM module. Experimental results demonstrated that S-YOLOv5m improved the mean average precision (mAP) by 4.73%, reduced parameters by 31% and shortened inference time by 1.3 ms compared to the original YOLOv5m [

19]. Li et al. aiming to achieve accurate detection of tea buds under limited computational capacity and complex environments, proposed an improved object detection model named Tea-YOLO based on YOLOv4. This model adopts GhostNet as the backbone network, incorporates depthwise separable convolution and adds the CBAM attention module. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model reduces the number of parameters by 82.36% and decreases computational complexity by 89.11% compared to YOLOv4, while maintaining comparable accuracy [

20].

1.1.2. Vision-Based Agricultural Object Positioning

After vision-based object recognition is completed, accurate positioning of agricultural objects becomes necessary. Commonly used visual positioning methods include monocular cameras [

21,

22], binocular stereo matching [

23,

24] and RGB-D cameras [

25,

26]. Only by combining object recognition and positioning can practical applications in agricultural production be achieved. Some scholars have conducted investigations on this integration [

27,

28]. Zhang et al. developed a field target recognition and following system based on a 48 V electric vehicle platform. By utilizing a 3D camera to capture depth and grayscale information of the target ahead, and employing a pure pursuit strategy for tracking specific objects, experimental results demonstrated that the system could successfully recognize and follow the target ahead [

29]. Arad et al. developed a greenhouse sweet pepper harvesting robot that utilizes a vision-based recognition algorithm leveraging color and shape features to detect sweet peppers. The system acquires positional data of the peppers and stems via an RGB-D camera, then executes motion control for picking actions. Experiments demonstrated that the robot could successfully harvest sweet peppers with an average harvest cycle of 24 s [

30]. Zhang et al. studied a recognition and localization method for tomato cluster picking points. Utilizing a trained YOLOv4 model, the system rapidly identifies tomato clusters and fruit calyx ROIs. The spatial position information of picking points is acquired using a D435i depth camera and converted into coordinates within the robotic arm coordinate system. Field experiments demonstrated that the average image recognition time of this method is 54 ms, with a picking point recognition accuracy of 93.83% and a depth error of ±3 mm [

31]. Yang et al. developed a crawler-type pumpkin harvesting robot, which utilizes an object detection model trained on the YOLO algorithm to identify pumpkins in the field and acquires their 3D coordinates via an RGB-D camera. Field tests in pumpkin fields demonstrated that the robot achieved a pumpkin detection accuracy exceeding 99% and a harvesting success rate of over 90% [

32]. Liu et al. developed a low-cost automated apple harvesting and sorting system. The system first segments apples in different growth positions under orchard environments using the YOLO algorithm, and then employs a RealSense D435i camera to localize the apples in the segmented images. Field test results demonstrated an automated apple harvesting success rate of 52.5%, with an average picking cycle of 4.3 s [

33].

In the field of agricultural machinery master-slave following positioning, Zhang et al. investigated a master-slave following navigation system for tractors in field operations, proposed a control framework for master-slave tractor coordination, and acquired tractor position data via GPS. Adjacent-path tests and turning experiments demonstrated that two tractors could collaboratively complete field tasks safely and efficiently, with the master-slave navigation system improving operational efficiency by 95.1% compared to traditional single-tractor operations [

34]. Li et al. developed an agricultural machinery master-slave following navigation system where the leader tractor is human-operated and the follower tractor autonomously tracks the leader during field operations. Both tractors were equipped with GNSS devices. The controller calculated lateral and heading deviations of the follower relative to the leader based on positional data and employed fuzzy control to determine the desired front-wheel steering angle. The follower was then controlled via PLC to track the leader. Experimental results indicated a lateral root mean square (RMS) error of 6.76 cm during steady following at 0.5 m/s [

35].

In summary, existing vision-based agricultural object recognition and positioning methods are predominantly focused on static objects such as fruits, vegetables, flowers, and obstacles. Agricultural machinery master-slave following systems primarily adopt GNSS for positioning. Research on real-time visual recognition and positioning of agricultural machinery, such as operating tractors in fields, remains scarce and urgently requires further investigation.

1.2. Research Objectives

In response to the above problems, this research proposes a real-time tractor recognition and positioning method based on machine vision, which includes the following components: (1) Tractor images under different weather conditions, viewing angles, and distances were collected and annotated to form a dataset; (2) An improved YOLOv4-based tractor recognition and positioning method was proposed, involving sparse training, pruning, and knowledge distillation applied to the baseline model, followed by testing and evaluation of the optimized lightweight model. The spatial position information of the leader tractor was further acquired through the ZED 2 camera SDK; (3) A field test hardware platform was constructed, and an experimental plan was designed to validate the recognition speed and positioning accuracy of the proposed method via real-vehicle field tests.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Experimental Hardware Platform Construction

The experimental hardware platform consists of two tractors: a leader tractor and a follower tractor. Two tractors were modified to meet the needs of this research, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The red tractor serves as the follower, a Wuzheng TS404 model (Wuzheng Group, Rizhao, China). Custom mounting brackets were designed to securely install the RGB-D camera ZED 2 (StereoLabs, San Francisco, CA, USA) on the front of the follower tractor. This installation method allows the follower tractor to capture real-time images of the leader tractor ahead. The follower tractor is also equipped with a Beiyun GNSS (Bynav, Changsha, China) device and an embedded host computer. The installation effect is demonstrated in

Figure 1. The position information output in real time by the GNSS rover represents the coordinates of the left antenna relative to the base station antenna. The blue tractor acts as the leader vehicle ahead, a Lovol Euroleopard TG1254 model (Lovol, Weifang, China). It is equipped with a integrated satellite navigation system XW-GI5651 (StarNeto, Beijing, China) produced by StarNeto. The host GNSS base station is positioned at the edge of the field.

2.1.2. Main Recognition and Positioning Sensors

The RGB-D camera used in this paper is the ZED 2 (manufactured by Stereolabs), primarily employed for robot navigation perception, 3D mapping, and stereo spatial reconstruction. Compared to other depth cameras, the ZED 2 features a wide field of view with 110° horizontally and 70° vertically. It offers an image resolution of 1280 × 720, a frame rate of 60 FPS and a USB 3.0 interface. By utilizing a novel lightweight neural network for stereo matching, it enhances measurement accuracy with a depth sensing range of up to 20 m. The camera demonstrates excellent outdoor performance, employing an f/1.8 aperture and an improved ISP to enhance low-light vision, ensuring reliable visual quality even on cloudy days. Its aluminum housing facilitates effective thermal management, and an operating temperature range of −10 °C to 50 °C meets the requirements for field operation environments.

The XW-GI5651 integrates GNSS, a three-axis gyroscope, a three-axis accelerometer, and a receiver. It employs multi-sensor fusion technology to combine satellite positioning with inertial measurements and supports three systems: BDS, GPS and GLONASS. The main technical parameters of the XW-GI5651 are as follows: position accuracy of 0.02 + 1 ppm (CEP), heading accuracy of 0.1°, attitude accuracy of 0.1°, interface options of RS232 or RS422, baud rate of 115,200, power supply voltage of 9–36 V.

2.1.3. Tractor Sample Construction and Annotation

Tractor images were collected at the Shangzhuang experiment station of China Agricultural University. The RGB-D camera ZED 2 was used to capture images of tractors from various angles and distances under both sunny and overcast conditions, with images saved in PNG format. To enrich the dataset and increase the variety of identifiable tractors, additional tractor images were downloaded from the internet for supplementation. After preprocessing and filtering, a dataset of 1200 tractor images was compiled. A subset of the dataset is shown in

Figure 2.

From the 1200 tractor images, 960 were randomly selected as the training set, while the remaining 240 images were used as the test set. The test set samples did not participate in the training process. All images were manually annotated using LabelImg software (v1.8.0), with the tractor cabin designated as the recognition target. The annotation process automatically generated corresponding XML result files for each image. To meet the dataset label format requirements of YOLOv4, a program was written to convert all XML files into TXT files. Each TXT file contains the coordinates of the top-left and bottom-right vertices of the bounding box.

2.1.4. Model Training Server and Embedded Host Computer

The deep learning framework based on PyTorch was trained on the server in the laboratory. The hardware included Intel(R) Core(TM) i9-10900X CPU, NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080-10 G GPU, and 64 GB RAM. The software environment included Windows 10, CUDA 11.1, cuDNN 8.1.1, Python 3.8.3 and PyTorch 1.8.1.

The embedded host computer utilized in this study is an NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier. The software environment consists of Ubuntu 18.04, JetPack 4.4, Jetson SDK, and Python 3.8.3. Other software packages employed are as follows: pip is used for installing and uninstalling software packages, pyzed serves as the Python API package for the ZED 2 camera, python-can and cantools facilitate CAN communication for millimeter-wave radar, pyserial enables serial communication, and xlwt is utilized for writing and saving data to Excel files.

2.2. Tractor Recognition Method Based on Improved YOLOv4

2.2.1. Overall Technical Route

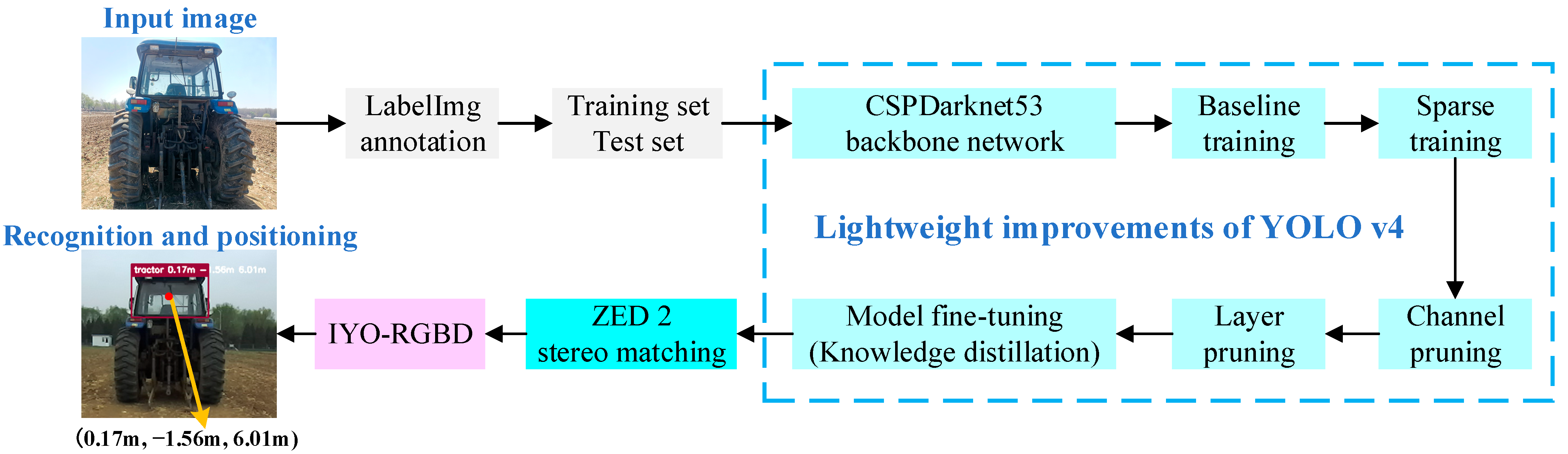

The technical approach to be adopted in this paper for achieving real-time recognition and positioning of tractors in field environments is illustrated in

Figure 3. Recognizing and positioning the leader tractor is a prerequisite for implementing master-slave following control. This study employs deep learning for tractor recognition and utilizes an RGB-D camera for positioning, enabling direct acquisition of the spatial coordinates of the leader tractor. Model pruning and knowledge distillation techniques are applied to optimize YOLOv4 for lightweight performance. Based on the enhanced YOLOv4 and RGB-D camera, a real-time tractor recognition and positioning method (IYO-RGBD) capable of operating on actual vehicles is proposed.

2.2.2. Baseline Training

YOLOv4 uses CSPDarknet53 as its backbone network and employs mosaic data augmentation. It primarily consists of five basic components: CBL (Convolution, Batch Normalization, and Leaky ReLU activation function), CBM (Convolution, Batch Normalization, and MISH activation function), Res unit (Residual unit), CSP (Center and Scale Prediction), and SPP (Spatial Pyramid Pooling), as illustrated in

Figure 4.

The loss function serves as an important metric for monitoring the training progress. The loss function of YOLOv4 consists of the predicted bounding box regression loss (

LCIoU), confidence loss (

Lconfidence), and classification loss (

Lclass), which is described as.

The

CIoU loss regression function takes into account the influence of overlap area, aspect ratio, and center point distance on the loss, enabling faster and more accurate bounding box regression in YOLOv4. The

CIoU loss is defined as:

where

ρAB denotes the distance between the center points of the ground truth box A

gt and the predicted box B

pr.

cAB represents the diagonal length of the minimum bounding box enclosing both A

gt and B

pr.

αLC is a positive trade-off parameter.

vLC represents the measure of aspect ratio consistency.

wgt and

hgt denote the width and height of the ground truth box, respectively.

wpr and

hpr denote the width and height of the predicted box, respectively.

The confidence loss is defined as.

where

Sbt represents the number of divided grids.

Bbt represents the number of bounding boxes predicted by each grid cell.

indicates whether the

j-th bounding box in the

i-th grid contains the recognition target, with a value of 1 if it does and 0 otherwise.

Ci denotes the confidence of the ground truth bounding box for the identified target.

denotes the confidence of the predicted bounding box for the identified target.

indicates that the

j-th bounding box in the

i-th grid does not contain the recognition target.

λnoobj is a hyperparameter, and an appropriate value is selected to adjust the confidence prediction loss.

The classification loss is defined as.

where

ccla represents the category of the recognition target.

pi(

ccla) represents the confidence of the known target category.

denotes the confidence of the predicted target category.

2.2.3. Sparse Training

After completing the baseline training with the YOLOv4 network and the tractor dataset, a high-precision tractor recognition model weight file is obtained. However, due to the excessive number of parameters and computational load, it cannot meet the real-time recognition requirements specified in this study. Therefore, lightweight improvements to the recognition model are necessary. The first step is to perform sparse training on the tractor recognition model weight file generated from the baseline training.

Regularization techniques are primarily used to control the complexity of the trained model and reduce overfitting. This is achieved by adding a penalty term to the original cost function, expressed as [

36].

where

Xsr represents the training samples.

ysr represents the corresponding training labels.

wsr is the weight coefficient vector.

J(·) is the cost function. Ω(

wsr) is the penalty term.

areg is the regularization strength adjustment coefficient.

The primary function of regularization is to prevent model overfitting.

L2 regularization employs the

l2 norm, which uniformly shrinks all weights and yields a dense solution. In contrast,

L1 regularization can drive unimportant weights precisely to zero, producing a sparse solution that better aligns with the requirements of this study. Therefore, the

l1 norm is adopted as the penalty term function, specifically

L1 regularization.

L1 regularization is applied to adjust the γ coefficients of the BN (Batch Normalization) layers in the YOLOv4 tractor recognition model, thereby sparsifying the model obtained from baseline training.

2.2.4. Channel Pruning and Layer Pruning

After sparse training is completed, channel pruning and layer pruning need to be performed on the tractor recognition model to reduce its size. As illustrated in

Figure 5, channel pruning evaluates the contribution of each input channel based on the γ values from the BN layers. Using a channel pruning algorithm, low-contribution channels are removed while retaining only high-contribution channels. Given that each model varies in size and application, multiple model pruning experiments with different channel pruning ratios are required to identify the optimal channel pruning method suitable for the tractor recognition model.

Layer pruning is developed on the basis of channel pruning. While channel pruning primarily reduces model size, layer pruning mainly impacts the inference speed of the model. Each CBM layer preceding a shortcut layer is evaluated, and the mean γ values of each layer are ranked. Subsequently, the shortcut layer with the smallest mean value is pruned using a layer pruning algorithm. To preserve the structural integrity of the YOLOv4 network, this study applies pruning only to the backbone structure. Each pruned shortcut layer results in the removal of the two preceding convolutional layers as well.

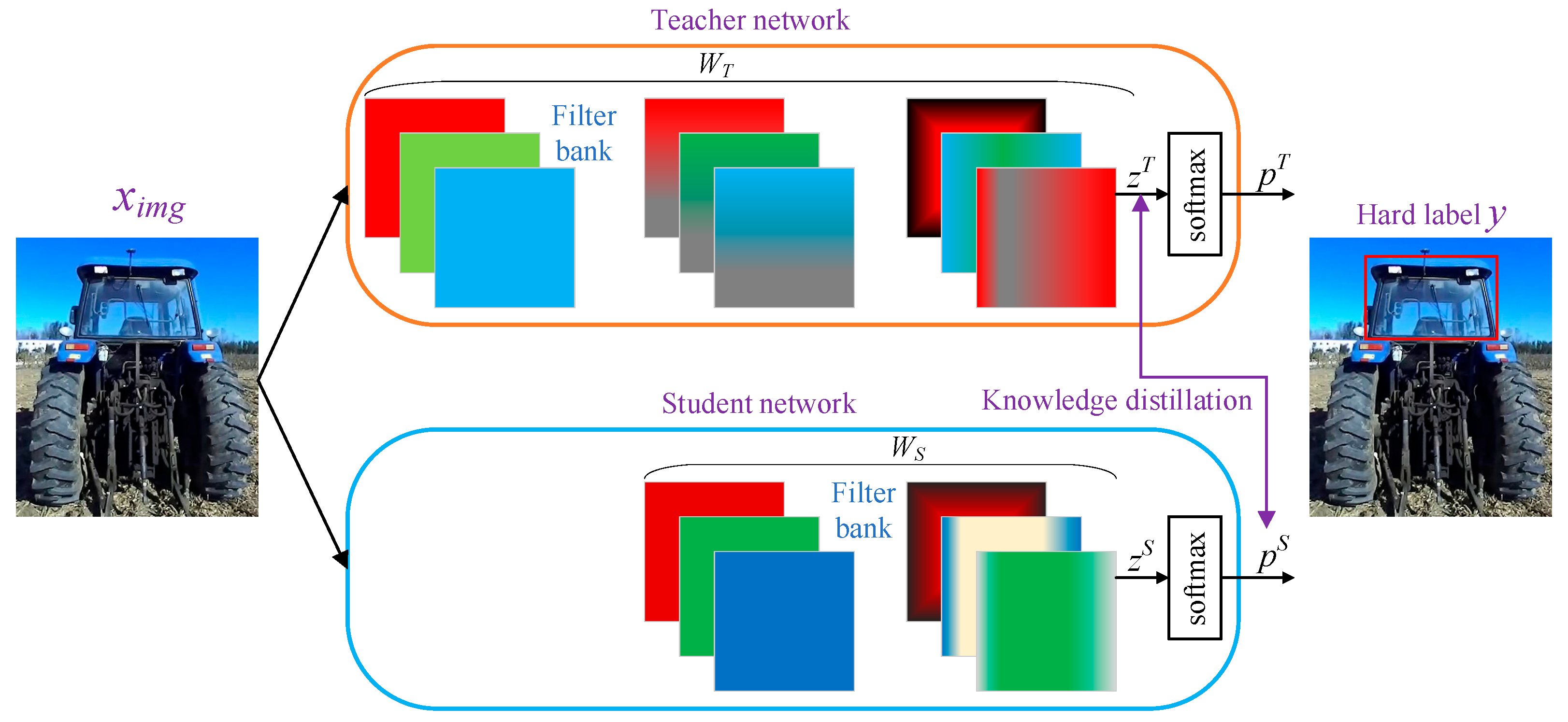

2.2.5. Model Fine-Tuning Based on Knowledge Distillation

After pruning, both the structure and quality of the tractor recognition model undergo significant changes, particularly with a decline in accuracy. Fine-tuning based on knowledge distillation can effectively restore accuracy. The fundamental approach of knowledge distillation employs a teacher-student strategy: for the same task, a small, low-precision network (the student) learns from a large, high-precision network (the teacher) to facilitate knowledge transfer, thereby improving the accuracy of the student network [

37]. This enables the model to simultaneously meet the requirements for both accuracy and speed in the task.

Figure 6 illustrates the fundamental principle of knowledge distillation. When a tractor image

ximg is input, the teacher network maps it to prediction

pT, utilizing the softmax function to classify the unnormalized logits

z,

. The same image is then fed into the student network,

. The loss function for fine-tuning training based on knowledge distillation is defined as.

where

WT is the parameter of the teacher network.

WS is the parameter of the student network.

ykd represents the label after knowledge distillation.

H(·) is a loss function.

αkd,

βkd and

γkd are weight coefficients.

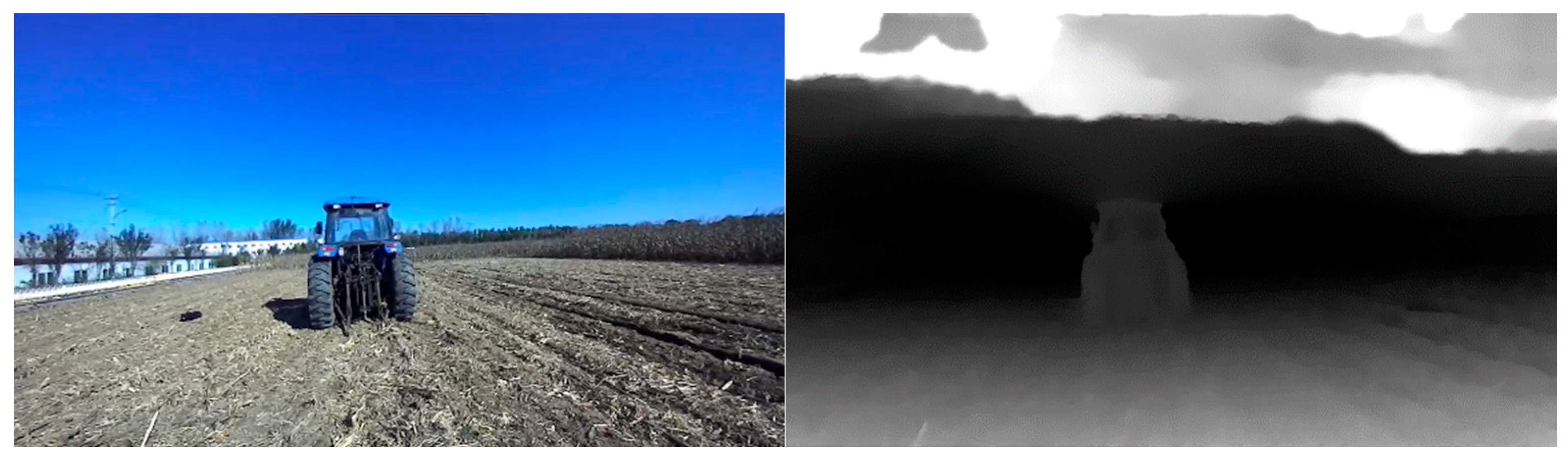

2.3. Tractor Positioning Method Based on RGB-D Camera

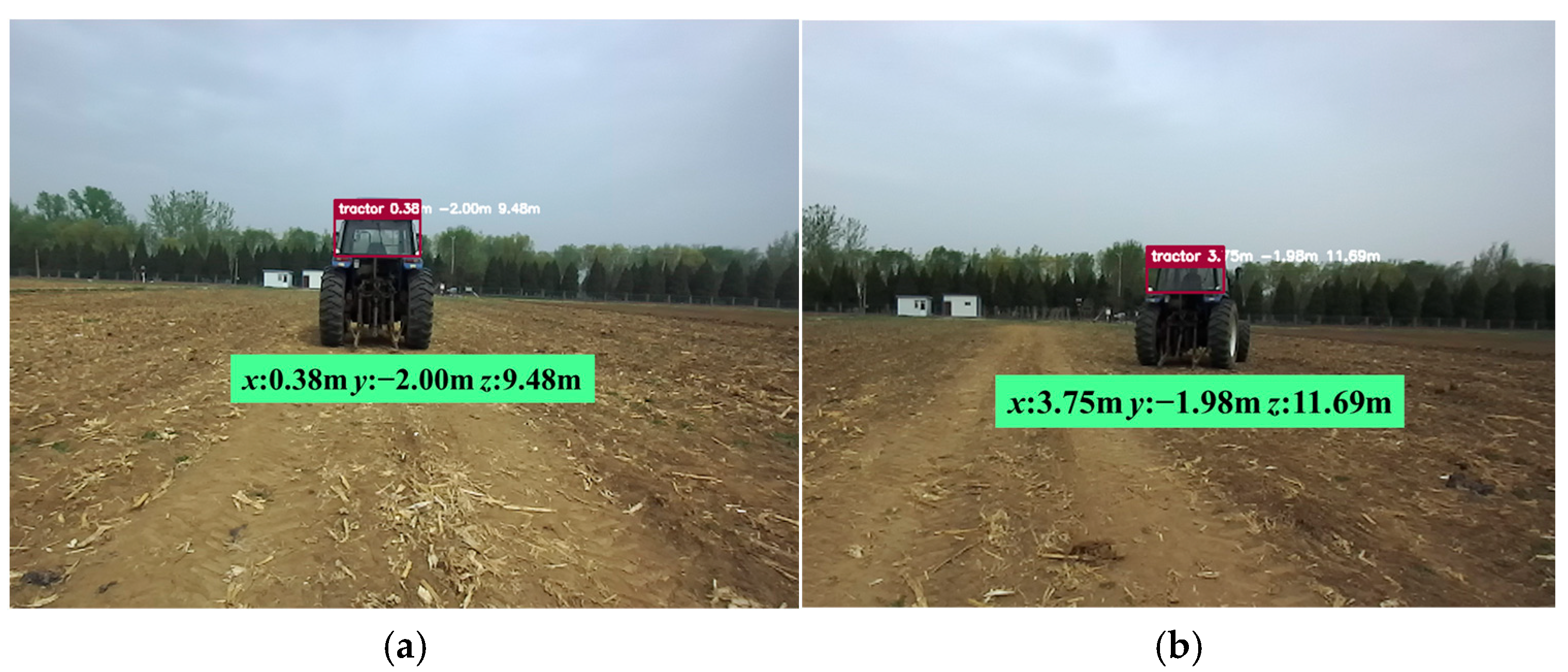

The RGB-D camera ZED 2 employs a lightweight neural network for stereo image matching, simultaneously meeting the requirements for both accuracy and real-time performance in stereo matching. It can be utilized by calling the camera SDK within the program. Parameters such as resolution, camera frame rate, and depth mode are configured using the InitParameters function. The depth mode offers three options: PERFORMANCE prioritizes stereo matching speed. QUALITY delivers high-quality matching results. ULTRA produces sharper edges and enhanced detail but requires more GPU memory and computational power. The sensing mode has two settings: STANDARD preserves edge details and depth accuracy, commonly used for autonomous navigation, obstacle detection, and pedestrian detection. FILL mode outputs smooth and dense depth maps, typically applied in AR/VR, mixed reality capture, and image post-processing. After configuring the relevant parameters, the camera is activated using the open function. The retrieve_measure function is called to acquire the depth point cloud of the tractor image, while the retrieve_image function enables real-time capture of both the tractor image and its corresponding depth map, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

The tractor recognition method based on improved YOLOv4 and positioning method based on RGB-D camera were fused together to build the IYO-RGBD model. Therefore, the IYO-RGBD model could calculate the longitudinal and lateral distances of the leader tractor relative to the follower tractor in real time.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tractor Recognition Model Test

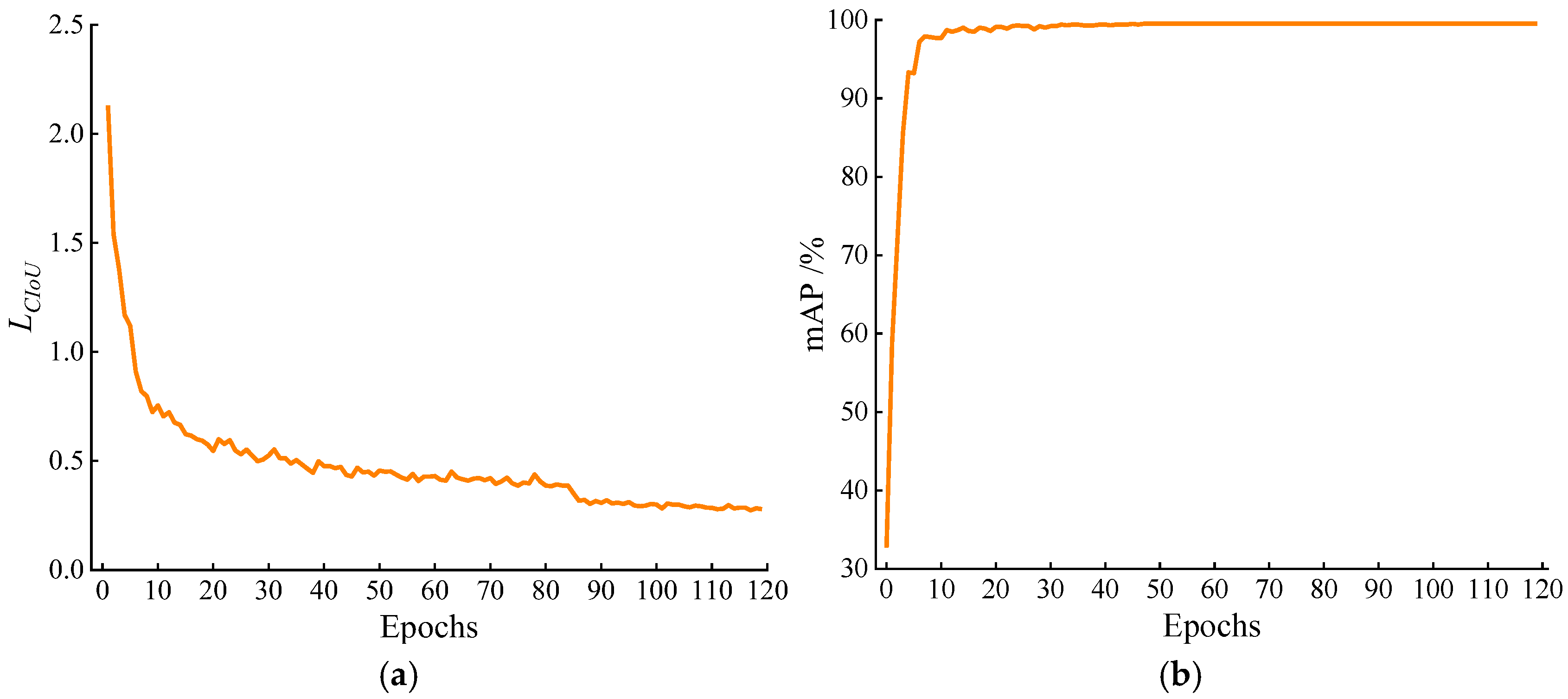

3.1.1. Baseline Training Results

The training parameter settings are as follows: the batch size is 64, classes is 1, subdivisions is 16, learning rate is 0.00261, mosaic is 1 and epochs is 120. The training duration for the tractor recognition model was 2.392 h. The variation curve of

LCIoU during the entire training process is shown in

Figure 8a. In the early stages of training, the iterative loss decreased rapidly and then gradually declined. When the training reached 106 epochs, the iterative loss showed no significant further reduction, fluctuating slightly around 0.28. As illustrated in

Figure 8b, the mean average precision (mAP) for all classes increased quickly, followed by minor fluctuations, eventually stabilizing at 99.5%. The size of the high-precision model is 244.41 MB.

3.1.2. Sparse Training Results

The number of epochs for sparse training was set to 300, with a sparsity factor s set to 0.001. The γ coefficients of the BN layers in the baseline model followed a normal distribution (

Figure 9a). The sparse training process is illustrated in

Figure 9b, where the γ coefficients of some BN layers gradually approached zero, though not all BN layers were compressed to zero, indicating progressive sparsification of the weight model. When sparse training reached the 128th epoch, the γ values stabilized with minimal changes, indicating that the sparse training had reached saturation and the tractor recognition model had achieved significant compression.

3.1.3. Channel Pruning and Layer Pruning Results

The channel retention ratio was set to 1%, with global pruning ratios configured at 95%, 90%, 85%, and 80%, respectively. The results of the four different channel pruning experiments are shown in

Table 1. Experiment 1 achieved the highest pruning ratio with an mAP of 88.84%, the fewest parameters, the smallest model size, and the fastest inference time. Experiment 2 yielded an mAP of 92.12%, reducing parameter count by 98.78%, model size by 98.76%, and inference time by 16.85% compared to the sparse model before channel pruning. Experiment 3, with an 85% pruning ratio, nearly doubled the parameter count and model size, but its mAP was lower than that of Experiment 2. This may be because, at this ratio, some channels with moderate γ coefficients but structurally important for the class were pruned, partially damaging the recognition model’s structure and leading to reduced accuracy. Experiment 4 resulted in a parameter count and model size more than three times larger than Experiment 2, while achieving a similar mAP. Based on the results of the four experiments, a 90% channel pruning ratio was ultimately selected. A comparison of channel counts before and after pruning is shown in

Figure 10. Each BN layer was pruned of 5 to 1014 channels, with a total of 28,842 channels removed throughout the process, validating the effectiveness of the channel pruning algorithm.

YOLOv4 contains 23 shortcut layers. The numbers of pruned shortcut layers were set to 20, 16, and 12, respectively, with the experimental results shown in

Table 2. Layer pruning has a relatively minor impact on the model but significantly affects inference speed. In Experiment 1, where 20 shortcut layers were pruned, the mAP was 92.08%, with a 2.15% reduction in parameter count, a 2.64% decrease in model size, and a 37.25% reduction in inference time compared to the channel-pruned model. Experiment 2 pruned fewer layers but resulted in lower accuracy than Experiment 1. Experiment 3 pruned 12 shortcut layers but exhibited the largest parameter count and model size, along with the longest inference time. After comparative analysis, pruning 20 shortcut layers was selected, resulting in a 7.42 percentage point decrease in mAP compared to the baseline trained model.

3.1.4. Model Fine-Tuning Results

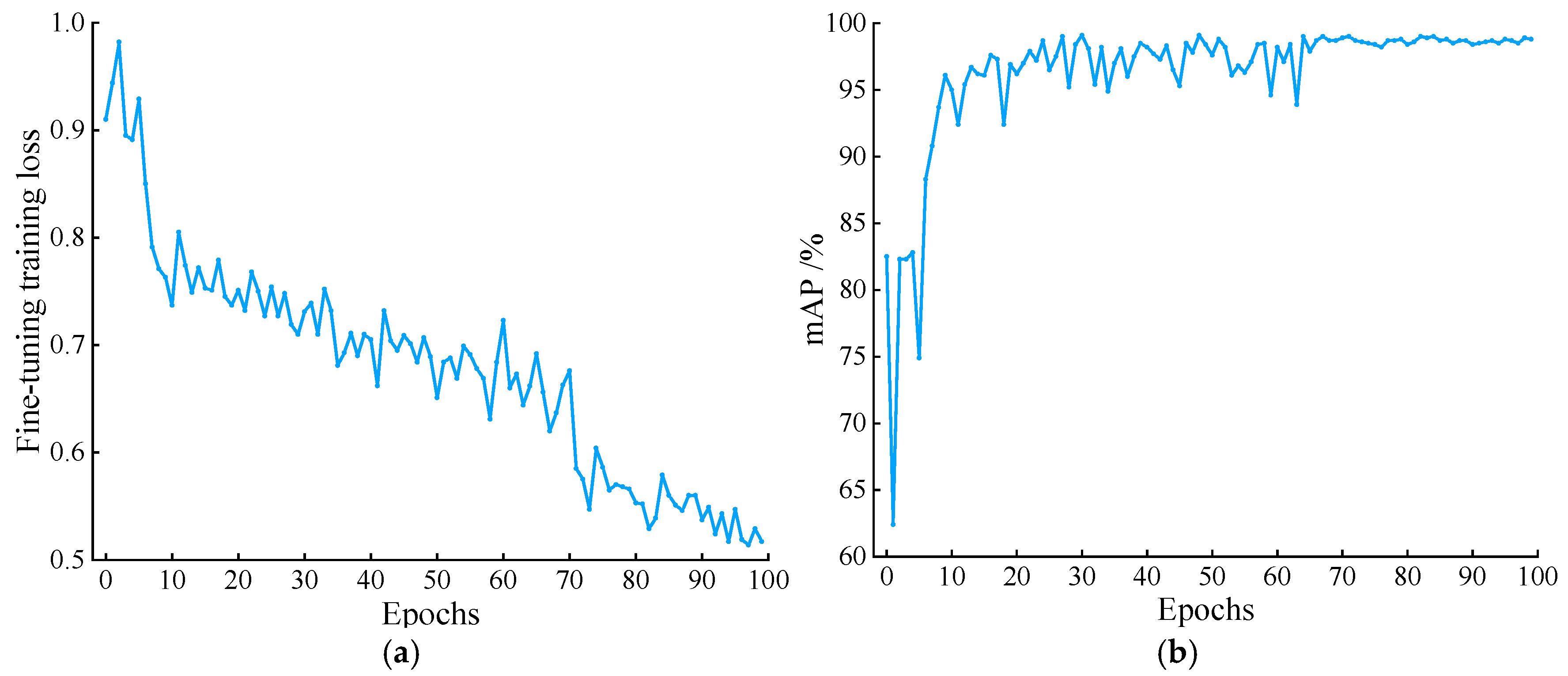

The fine-tuning training based on knowledge distillation was set to 100 epochs. The changes in iterative loss and mAP are shown in

Figure 11. The fine-tuning training loss gradually decreased to 0.52 and then fluctuated slightly. During the process of the student network learning from the teacher network, the mAP initially exhibited sharp fluctuations at the beginning of fine-tuning, followed by a steady increase. After a period of minor fluctuations, it stabilized, eventually reaching a final mAP of 98.80%. Compared to the pre-fine-tuning value of 92.08%, this represents an improvement of 6.72 percentage points, demonstrating the effectiveness of knowledge distillation.

3.1.5. Lightweight Model Testing and Result Analysis

Precision (

P), Recall (

R), mean Average Precision (mAP), Intersection over Union (

IoU), and recognition speed were used as evaluation metrics for testing the target recognition model.

where

TP denotes the number of true positives.

FN denotes the number of false negatives.

FP denotes the number of false positives

The AP (Average Precision) value represents the average precision of the model in recognizing a single class, while the mAP is the average AP value across all classes recognized by the model. In the recognition test of the tractor dataset in this chapter, the recognition target consists of only one class—the tractor cabin—so the mAP value equals the AP value. Recognition speed is a critical indicator of whether the model can be applied to real-time recognition of the host vehicle by the follower. Only when this requirement is met can the follower’s motion control for tracking be further implemented.

To evaluate the accuracy and real-time performance of the lightweight tractor recognition model, independent tests were conducted on the test set, with the results shown in

Table 3. Compared to the high-precision model from baseline training, the mAP of the lightweight model differed by only 0.7 percentage points. Although precision (

P), mean

IoU, and recall (

R) slightly decreased, these changes had minimal impact on the overall recognition performance of the model. The recognition speed reached 62.50 fps, representing a 43.74% improvement, while the size of the lightweight model was reduced to 3.11 MB, a 98.73% reduction compared to the high-precision baseline model.

The target detection results of the lightweight tractor recognition model are shown in

Figure 12. The model accurately identifies tractor cabins in images captured from various angles and distances, further demonstrating the effectiveness of the improved YOLOv4 algorithm.

3.2. Field Experiments

3.2.1. Design of Experimental Scheme

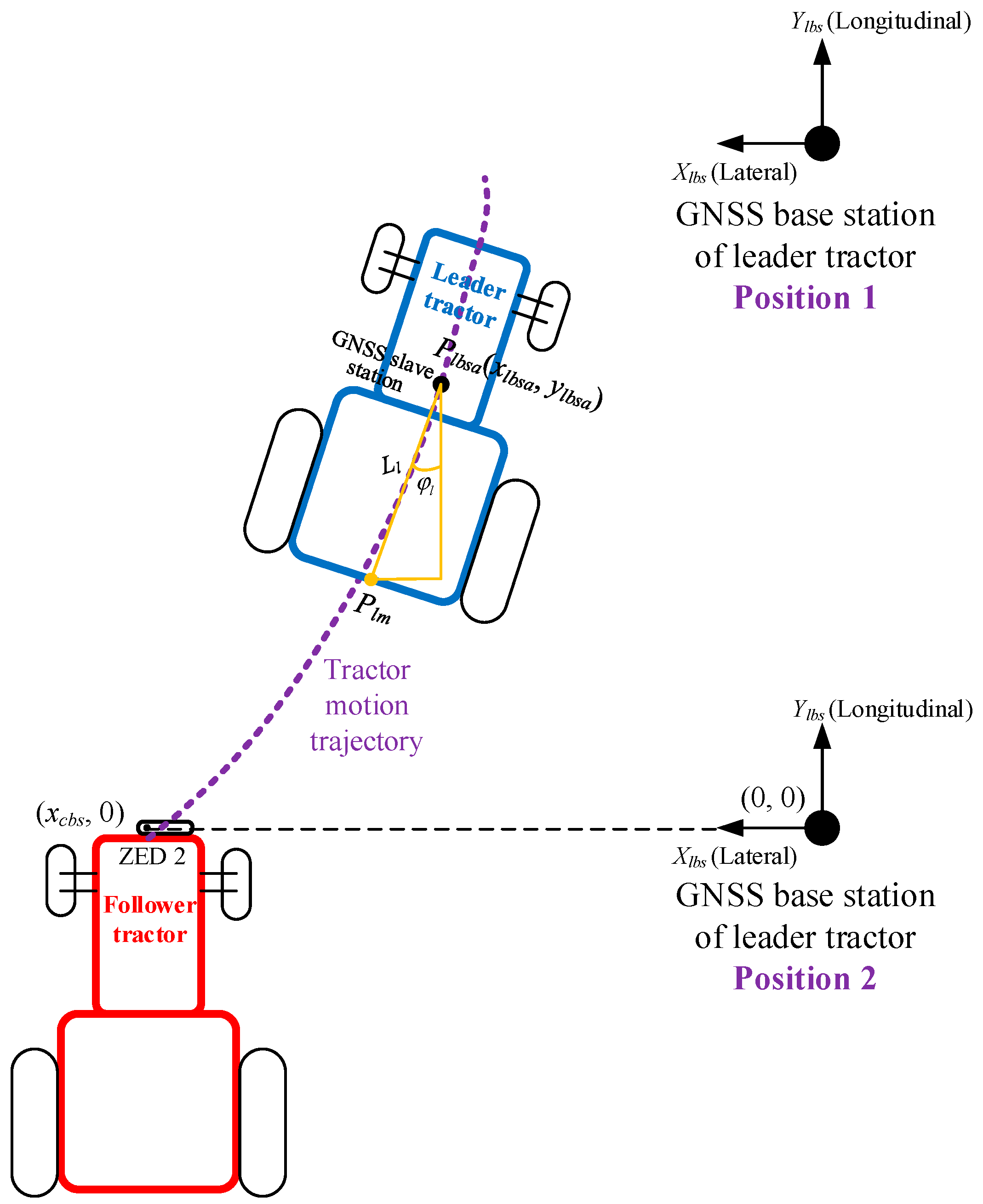

The hardware equipment required for the experiment is shown in

Figure 1, and their relative positions are illustrated in

Figure 13. Due to constraints in the field test environment, the GNSS base station of leader tractor needed to be positioned at the edge of the field, as indicated by base station position 1. To facilitate data analysis, coordinate transformation was applied to align the horizontal axis of the base station coordinate system with the horizontal axis of the camera coordinate system, as shown in base station position 2. This position was defined as the coordinate origin (0, 0), where the Y-axis of the base station coordinate system corresponds to the

Z-axis of the ZED 2 camera coordinate system.

The heading angle

and spatial position

Plbsa (

xlbsa,

ylbsa) of the leader tractor in the base station coordinate system can be acquired in real-time by the XW-GI5651 and transmitted to the portable computer. When the leader tractor is oriented toward the positive

Y-axis of the base station coordinate system, the heading angle

is 0°, with left turns defined as positive and right turns as negative. When the leader tractor turns left or right, the coordinates of the center point

Plm of the tractor cabin’s rear window in the base station coordinate system can be obtained using Equation (10).

The IYO-RGBD tractor recognition model was deployed on the follower tractor’s embedded host computer, Jetson AGX Xavier, to acquire real-time longitudinal and lateral positions of the leader tractor ahead. The lateral distance of the RGB-D camera’s left lens on the follower tractor relative to the base station is denoted as xcbs. The coordinates (xlbc, ylbc) of the center point Plm of the leader tractor cabin’s rear window, obtained in real-time via IYO-RGBD, can be converted to its position coordinates Plm (xcbs − xlbc, ylbc) in the base station coordinate system. The coordinates of point Plm can also be acquired in real-time through the leader tractor’s GNSS rover.

The longitudinal and lateral distances of the leader tractor measured by the GNSS are denoted as Dygnss and Dxgnss, respectively, while those obtained by IYO-RGBD are denoted as Dyzed and Dxzed. Based on the leader tractor position data from these two measurement methods, the longitudinal and lateral errors between the positions acquired by IYO-RGBD and the GNSS were calculated.

3.2.2. Field Experimental Results and Analysis

The field experiment was conducted under sunny weather conditions, with the tractor moving at a constant speed in first gear (approximately 0.88 m/s). The leader tractor’s GNSS data acquisition frequency was 20 Hz, while the IYO-RGBD recognition and positioning speed reached 62.5 f/s. During the experiment, the leader tractor remained stationary for 5 s before moving forward. The initial moment of movement was selected as the starting point to ensure the timestamps of the GNSS data and IYO-RGBD data were as closely aligned as possible. The leader tractor traveled at first gear speed (approximately 0.88 m/s) along straight-line and S-curve paths, respectively. IYO-RGBD performed real-time recognition and tracking, outputting data accordingly. The positions obtained by the leader tractor’s GNSS rover were used as reference and compared with the tracking positions from IYO-RGBD. The tracking results for the leader tractor’s straight-line and S-curve paths are shown in

Figure 14a and

Figure 14b, respectively.

As shown in

Figure 15a, the leader tractor moved in a straight line from point A

sl (3.6309 m, 3.0119 m) to point B

sl (3.5605 m, 18.9917 m). Simultaneously, the leader’s position coordinates were acquired in real-time through IYO-RGBD, with straight line C

slD

sl representing the recognition and tracking trajectory. The longitudinal error, denoted as

Ey =

Dyzed −

Dygnss, is illustrated in

Figure 15b. The maximum absolute longitudinal error was 0.3474 m, with a mean error of 0.1231 m and a root mean square (RMS) longitudinal error of 0.1524 m. The lateral error, denoted as

Ex =

Dxzed −

Dxgnss, is shown in

Figure 15c. The maximum absolute lateral error was 0.1642 m, with a mean error of 0.0674 m and an RMS lateral error of 0.0871 m.

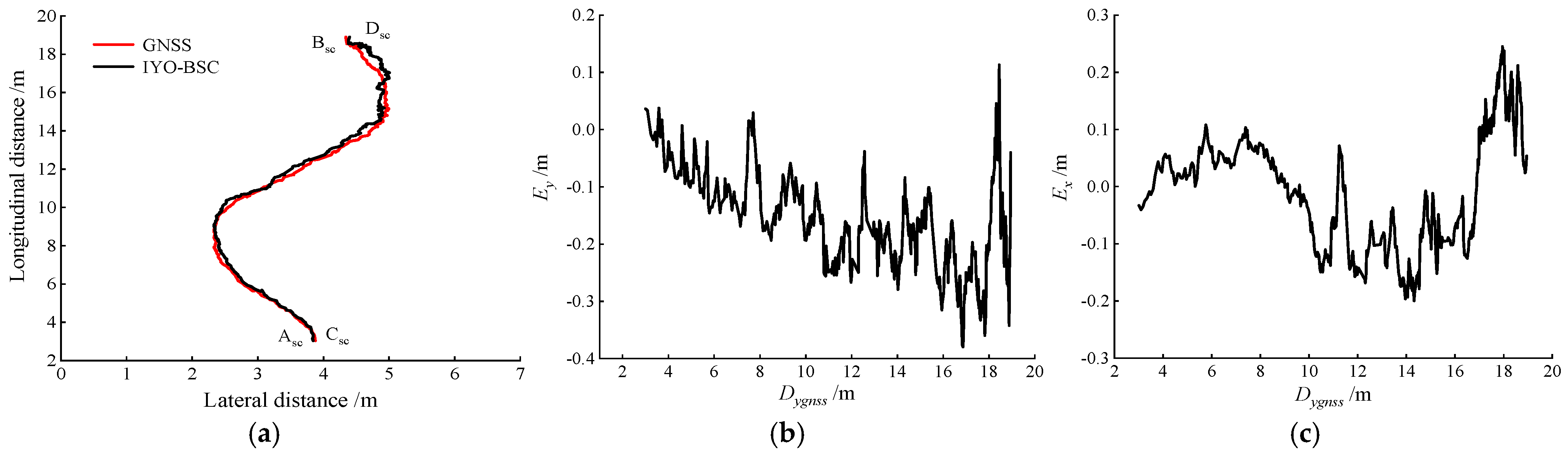

As shown in

Figure 16a, the leader tractor traveled along an S-curve from point A

sc (3.8763 m, 3.0101 m) to point B

sc (4.3434 m, 18.9434 m). Curve C

scD

sc represents the recognition and tracking trajectory of the leader tractor by IYO-RGBD. As shown in

Figure 16b, the maximum absolute longitudinal error was 0.3798 m, with a mean longitudinal error of −0.1679 m and an RMS error of 0.1874 m. As illustrated in

Figure 16c, the maximum lateral error was 0.2449 m, with a mean lateral error of −0.0125 m and an RMS error of 0.1043 m.

When IYO-RGBD performs recognition and tracking of the leader tractor, as the measurement distance approaches the maximum depth sensing range of 20 m for the ZED 2 camera, the fluctuations and error margins in the longitudinal and lateral distances of the leader tractor obtained by the stereo camera gradually increase. However, even at the maximum range of 20 m, the absolute value of the maximum longitudinal error does not exceed 0.4 m. It is noteworthy that as the recognition distance increases, particularly when the inter-tractor distance exceeds 12 m, the leader tractor cabin occupies a progressively smaller area in the recognition image. This can lead to slight jitter in the recognition frames, a decrease in real-time IoU values, and a gradual increase in lateral error. The lateral tracking accuracy for S-curves is lower than that for straight lines because steering maneuvers cause the feature recognition bounding box to shift left or right, thereby amplifying lateral tracking errors.

In practical field operations, the follower typically maintains a distance of within 10 m from the leader tractor. Therefore, this chapter further analyzes the recognition and positioning data of IYO-RGBD within this 10 m range. The results, presented in

Table 4, show that for leader tractors moving along straight lines and S-curves within 10 m, the RMS of the longitudinal errors are 0.0687 m and 0.1101 m, respectively, while the RMS of the lateral errors are 0.025 m and 0.0481 m, respectively. Both the longitudinal and lateral tracking accuracies meet the precision requirements for practical leader-follower coordination in field operations.

The maximum perception range of the RGB-D camera ZED 2 is 20 m. When the distance to the front tractor exceeds 10 m, both lateral and longitudinal measurement errors gradually increase with distance. Therefore, the errors in tractor recognition and positioning accuracy under such conditions are primarily influenced by the measurement precision of the depth camera.

4. Conclusions

To address the challenge of recognizing and positioning the leader tractor by follower tractors in multi-machine collaborative navigation for agricultural machinery in field environments, a real-time tractor recognition and positioning method based on machine vision was proposed. A tractor sample dataset was constructed, and a recognition model was trained. The YOLOv4 object detection algorithm was optimized for lightweight deployment through model pruning and knowledge distillation. Test results demonstrated that, compared to the high-precision baseline model, the lightweight model achieved a size of 3.11 MB, representing a reduction of 98.73%. The lightweight model attained performance metrics of 98.80% mAP, 90.12% precision (P), 98.16% recall (R), and 85.26% mean IoU. While these values experienced slight decreases, the overall recognition performance remained largely unaffected. The recognition speed reached 62.50 fps, marking a 43.74% improvement. On this foundation, the positioning of the leader tractor was accomplished using an RGB-D camera.

A hardware platform for real-vehicle recognition and positioning experiments was established, and an experimental plan was designed. The results indicated that during straight-line travel, IYO-RGBD achieved longitudinal and lateral RMS errors of 0.1524 m and 0.0871 m, respectively. During S-curve travel, the longitudinal and lateral RMS errors were 0.1874 m and 0.1043 m, respectively. When IYO-RGBD performed recognition and positioning within a 10 m range, the longitudinal and lateral RMS errors for straight-line travel were 0.0687 m and 0.0250 m, while for S-curve travel, they were 0.1101 m and 0.0481 m, respectively. The longitudinal and lateral tracking accuracy of IYO-RGBD for the leader tractor moving in both straight lines and S-curves met the precision requirements for practical leader–follower collaborative field operations.

In conclusion, the proposed method enables real-time, rapid, and accurate recognition and positioning of tractors in field environments. It provides perceptual information of the leader tractor to the follower, thereby offering a new solution for automated multi-machine collaborative navigation in agricultural field operations.

In future work, we can enhance the diversity of the dataset by incorporating additional types of tractors. Then, we plan to integrate an object tracking mechanism into our tractor recognition and positioning approach, thereby further enhancing the robustness of object detection. Obstacle avoidance and coordinating multiple tractors are also considered potential directions for our future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; methodology, L.W.; software, L.W.; validation, L.W. and D.Z.; resources, L.W. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and D.Z.; supervision, Z.Z.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Fund, grant number 32501796, the Research Start-up Fund Project of Changzhou University, grant number ZMF23020191, and the Changzhou Science and Technology Project, grant number CJ20240053.

Data Availability Statement

All research data supporting this study are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, M.; Ji, Y.; Li, S.; Cao, R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z. Research progress of agricultural machinery navigation technology. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Gong, L.; Zhou, B.; Huang, Y.; Liu, C. Detecting tomatoes in greenhouse scenes by combining AdaBoost classifier and colour analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 148, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, W.; Payne, A.; Walsh, K.; Linker, R.; Cohen, O.; Dailey, M. Machine vision for counting fruit on mango tree canopies. Precis. Agric. 2017, 18, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, P.; Zou, X. A vision methodology for harvesting robot to detect cutting points on peduncles of double overlapping grape clusters in a vineyard. Comput. Ind. 2018, 99, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Sheng, Z.; Gu, B.; Tian, G.; Zhang, J. Obstacle Detection based on point clouds in application of agricultural navigation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2015, 31, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cubero, S.; Aleixos, N.; Albert, F.; Torregrosa, A.; Ortiz, C.; García-Navarrete, O.; Blasco, J. Optimised computer vision system for automatic pre-grading of citrus fruit in the field using a mobile platform. Precis. Agric. 2014, 15, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, Y.; Sossa, H.; Pajares, G. Spatio-temporal analysis for obstacle detection in agricultural videos. Appl. Soft Comput. 2016, 45, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zou, X.; Chen, L.; Xiong, J.; Chen, K.; Lin, G. Fast Recognition of multiple color targets of litchi image in field environment based on double Otsu algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Zhao, D.; Ji, W. Fast tracing recognition method of target fruit for apple harvesting robot. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2014, 45, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Chen, P.; Pang, J.; Yang, X.; Chen, C.; Tu, S.; Xue, Y. A mango picking vision algorithm on instance segmentation and key point detection from RGB images in an open orchard. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 206, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, L.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Branch detection for apple trees trained in fruiting wall architecture using depth features and Regions-Convolutional Neural Network (R-CNN). Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 155, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xiong, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, G.; Kuremot, T.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Y. Integrated detection of citrus fruits and branches using a convolutional neural network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, D. Potato detection in complex environment based on improved YoloV4 model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Z.; Luo, L.; Liao, J.; Wen, H.; Wei, H.; Lu, Q. Recognition and the optimal picking point location of grape stems based on deep learning. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 222–229. [Google Scholar]

- Padhiary, M.; Roy, P.; Dey, P.; Sahu, B. Harnessing AI for automated decision-making in farm machinery and operations: Optimizing agriculture. In Enhancing Automated Decision-Making Through AI; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 249–282. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.; Chen, C. Fruit detection, segmentation and 3D visualisation of environments in apple orchards. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 171, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Fruit detection for strawberry harvesting robot in non-structural environment based on Mask-RCNN. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 163, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, M.; Lei, J.; Wang, X.; Tan, K. Blueberry maturity recognition method based on improved YOLOv4-Tiny. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Luo, F.; Wu, P.; Tan, J.; Wang, L.; Niu, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, P. An improved YOLO network for small target insects detection in tomato fields. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Su, X.; Wu, W. Lightweight detection networks for tea bud on complex agricultural environment via improved YOLO v4. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 211, 107955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Tang, Y.; Zou, X.; Ye, M.; Feng, W.; Li, G. Vision-based extraction of spatial information in grape clusters for harvesting robots. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 151, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, Y.; Liu, G.; Feng, J. Location of apples in trees using stereoscopic vision. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2015, 112, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, C.; Tan, Y.; Li, W. A method for broccoli seedling recognition in natural environment based on binocular stereo vision and gaussian mixture model. Sensors 2019, 19, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Tang, Y.; Zou, X.; Huang, K.; Huang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Lian, G. Three-dimensional perception of orchard banana central stock enhanced by adaptive multi-vision technology. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 174, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Zou, X.; Lin, G.; Wang, H. Detection of fruit-bearing branches and localization of litchi clusters for vision-based harvesting robots. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 117746–117758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumam, K.; Krajnik, T.; Pearson, S.; Duckett, T.; Cielniak, G. 3D-vision based detection, localization, and sizing of broccoli heads in the field. J. Field Robot. 2017, 34, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Tang, Y.; Zou, X.; Li, J.; Xiong, J. In-field citrus detection and localisation based on RGB-D image analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 186, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y. Orchard pedestrian detection and location based on binocular camera and improved YOLOv3 algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Noguchi, N. Development of robot tractor associating with human-drive tractor for farm work. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2013, 46, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arad, B.; Balendonck, J.; Barth, R.; Ben-Shahar, O.; Edan, Y.; Hellström, T.; Hemming, J.; Kurtser, P.; Ringdahl, O.; Tielen, T.; et al. Development of a sweet pepper harvesting robot. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Xu, C. Method for recognizing and locating tomato cluster picking points based on RGB-D information fusion and target detection. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Noguchi, N.; Hoshino, Y. Development of a pumpkin fruits pick-and-place robot using an RGB-D camera and a YOLO based object detection AI model. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, J.; Hua, W.; Li, X.; Azizi, A.; Mhamed, M.; Abid, F.; Abdelhamid, M. Design, integration, and evaluation of a low-cost system for automatic apple picking and infield sorting. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 110933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Noguchi, N.; Yang, L. Leader-follower system using two robot tractors to improve work efficiency. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 121, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xu, H.; Ji, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, M.; Li, H. Development of a following agricultural machinery automatic navigation system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 158, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O. Recurrent neural network regularization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1409.2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Experimental hardware platform.

Figure 1.

Experimental hardware platform.

Figure 2.

Partial tractor dataset: (a–e) are sunny images and (f–h) are overcast images.

Figure 2.

Partial tractor dataset: (a–e) are sunny images and (f–h) are overcast images.

Figure 3.

Overall technical route.

Figure 3.

Overall technical route.

Figure 4.

YOLO v4 architecture diagram.

Figure 4.

YOLO v4 architecture diagram.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of channel pruning.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of channel pruning.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the basic principle of knowledge distillation.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the basic principle of knowledge distillation.

Figure 7.

Tractor image and its depth map.

Figure 7.

Tractor image and its depth map.

Figure 8.

Baseline training results: (a) iterative loss curve; (b) mAP curve.

Figure 8.

Baseline training results: (a) iterative loss curve; (b) mAP curve.

Figure 9.

γ coefficient distribution: (a) baseline training; (b) sparse training.

Figure 9.

γ coefficient distribution: (a) baseline training; (b) sparse training.

Figure 10.

Comparison of channel counts before and after pruning.

Figure 10.

Comparison of channel counts before and after pruning.

Figure 11.

Fine-tuning training results: (a) iterative loss curve; (b) mAP curve.

Figure 11.

Fine-tuning training results: (a) iterative loss curve; (b) mAP curve.

Figure 12.

Tractor recognition results.

Figure 12.

Tractor recognition results.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of relative hardware positions.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of relative hardware positions.

Figure 14.

Straight-line and S-curve tracking results of IYO-RGBD: (a) straight-line; (b) S curve.

Figure 14.

Straight-line and S-curve tracking results of IYO-RGBD: (a) straight-line; (b) S curve.

Figure 15.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD during straight-line travel of the leader tractor: (a) tracking trajectories of GNSS and IYO-RGBD; (b) the longitudinal error curve; (c) the lateral error curve.

Figure 15.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD during straight-line travel of the leader tractor: (a) tracking trajectories of GNSS and IYO-RGBD; (b) the longitudinal error curve; (c) the lateral error curve.

Figure 16.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD during S-curve travel of the leader tractor: (a) tracking trajectories of GNSS and IYO-RGBD; (b) the longitudinal error curve; (c) the lateral error curve.

Figure 16.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD during S-curve travel of the leader tractor: (a) tracking trajectories of GNSS and IYO-RGBD; (b) the longitudinal error curve; (c) the lateral error curve.

Table 1.

Channel pruning experimental results.

Table 1.

Channel pruning experimental results.

| Channel Pruning Experiment | Global Pruning Ratio/% | Channel Retention Ratio/% | mAP/% | Parameter Count | Model Size/M | Inference Time/s |

|---|

| Sparse model | 0 | 100 | 95.99 | 63,937,686 | 244.44 | 0.0184 |

| Experiment 1 | 95 | 1 | 88.84 | 305,164 | 1.19 | 0.0140 |

| Experiment 2 | 90 | 1 | 92.12 | 782,467 | 3.03 | 0.0153 |

| Experiment 3 | 85 | 1 | 90.76 | 1,448,070 | 5.58 | 0.0164 |

| Experiment 4 | 80 | 1 | 92.99 | 2,650,438 | 10.18 | 0.0166 |

Table 2.

Layer pruning experimental results.

Table 2.

Layer pruning experimental results.

| Layer Pruning Experiment | Number of Pruned Shortcut Layers | mAP/% | Parameter Count | Model Size/M | Inference Time/s |

|---|

| Channel-pruned model | 0 | 92.12 | 782,467 | 3.03 | 0.0153 |

| Experiment 1 | 20 | 92.08 | 765,641 | 2.95 | 0.0096 |

| Experiment 2 | 16 | 91.90 | 770,737 | 2.98 | 0.0109 |

| Experiment 3 | 12 | 92.13 | 774,597 | 2.99 | 0.0123 |

Table 3.

Comparison of model test results.

Table 3.

Comparison of model test results.

| Evaluation Metric | P/% | R/% | Average IoU/% | mAP/% | Recognition Speed/(f/s) |

|---|

| Baseline model | 91.45 | 99.24 | 89.31 | 99.50 | 43.48 |

| Lightweight model | 90.12 | 98.16 | 85.26 | 98.80 | 62.50 |

Table 4.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD within 10 m.

Table 4.

Tracking results of IYO-RGBD within 10 m.

| | Max Absolute Longitudinal Error/m | Mean Longitudinal Error/m | Longitudinal Error RMS/m | Max Absolute Lateral Error/m | Mean Lateral Error/m | Lateral Error RMS/m |

|---|

| Straight line | 0.1493 | 0.0512 | 0.0687 | 0.0610 | 0.0100 | 0.0250 |

| S-curve | 0.1933 | −0.0956 | 0.1101 | 0.1078 | 0.0308 | 0.0481 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).