Abstract

Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods are increasingly applied in modern agriculture to enable the rapid, efficient, and non-invasive evaluation of crops and agricultural products. Among these, polarization spectroscopy analysis (PSA) combines polarization information with spectral data to provide detailed insights into plant and soil properties. This review summarizes the principles and key parameters of polarimetry and highlights PSA applications, including crop health monitoring, pest and disease detection, chlorophyll and nutrient estimation, seed quality assessment, and soil moisture and pollution evaluation. PSA demonstrates advantages over conventional spectroscopy by revealing structural information and maintaining robustness in complex environments. Its ability to support precision agriculture through the real-time monitoring and early detection of stress factors underscores its potential for smart agricultural systems. Future efforts should focus on data fusion, model optimization, equipment miniaturization, and enhanced adaptability to fully realize PSA’s role in intelligent agriculture.

1. Introduction

Agricultural materials, including crops, fruits and vegetables, seeds, and soil, are crucial for both agricultural economy and food safety during production, processing, and storage [1]. In modern agriculture, several key indicators directly influence production efficiency and quality including monitoring crop growth stages, managing water resources effectively [2], assessing the agricultural environment [3], and evaluating the internal and external quality of fruits [4]. By carefully monitoring and managing these key indicators, farmers can enhance productivity, improve resource utilization, and produce high-quality agricultural products. Advancement in precision and smart agriculture relies on the integration of novel technologies with rapid response capabilities, non-destructive testing features [5], and cost-effectiveness across all phases of agricultural production, including cultivation, management, and harvesting. These technologies not only enhance the real-time monitoring of crop growth and improve the efficiency of agricultural resource utilization, but also enable dynamic evaluation and precise control of crop quality. Consequently, such innovations play a critical role in advancing agricultural modernization and promoting sustainable development.

Traditional destructive detection methods pose several challenges in piratical applications, including resource consumption, time efficiency, and scalability. These methods require destructive sampling, rendering the tested samples unusable or unsellable. This practice leads to material waste, and increased costs. Moreover, the testing process is time-consuming, and labor-intensive, involving multiple steps such as sample preparation, laboratory analysis, and data processing [6]. This multi-stage approach results in extended testing cycles that are poorly suited to rapid detection and real-time decision-making [7]. Furthermore, efficiency is further affected by the reliance on manual operations and complex equipment, making it difficult to conduct the large-scale or continuous testing of numerous samples. With the advancement in technology, non-destructive testing (NDT) has gained widespread attention and application due to its real-time capability, low energy consumption, and minimal sample preparation. NDT has significantly improved testing efficiency and reduced costs in various industries such as manufacturing, agriculture, and medical diagnostics. In agriculture, NDT plays a vital role in monitoring crop quality [8], detecting disease at an early stage [9], and assessing plant growth [10]. Among the available NDT methods, computer vision and spectral technologies have gained increasing attention and application due to their low cost, high accuracy, and rapid analysis capabilities [11,12,13]. Computer vision technology enables the fast and accurate detection of pests and diseases through automated image capture and intelligent image analysis, significantly improving the efficiency and reliability of monitoring [14]. Similarly, spectral technology allows the rapid, non-destructive assessment of internal crop attributes such as nitrogen level [15], sugar content [16], and diseased tissues [17], by analyzing how substances reflect, absorb, or scatter light at different wavelengths. The integration of these technologies not only increases the level of automation and intelligence in agricultural testing, but also provides strong technical support for the advancement in precision and smart agriculture.

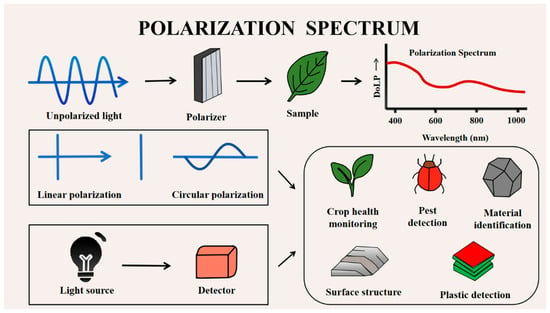

Polarization spectroscopy is an analytical technique that integrates polarization information with spectral measurements, enabling the characterization of how agricultural materials interact with polarized light [18]. In this review, we briefly introduce the basic principles of polarization spectroscopy and summarize its representative applications in agricultural engineering (Figure 1). A detailed comparison of its detection mechanisms and advantages over traditional spectroscopy is presented in Section 2.4.

Figure 1.

Overview of the polarization spectroscopy analysis (PSA) process for agricultural material detection. The workflow includes the following: (1) illumination of the sample with controlled or natural light; (2) interaction of light with the sample’s microstructure, producing characteristic polarization changes; (3) acquisition of reflected or transmitted light using a polarization-resolved sensor or spectrometer (e.g., Stokes parameters, DoLP, and AoP); (4) extraction of polarization features; and (5) application of these features to tasks such as crop stress diagnosis, quality evaluation, and structural characterization. This figure illustrates how polarization information is generated, measured, and analyzed across different agricultural applications.

Although several reviews have discussed polarization remote sensing [19] or canopy-level polarization measurement [20], most of them focus on theoretical radiative transfer, optical models, or atmospheric–vegetation interactions, with limited attention being paid to agricultural engineering applications. Existing reviews seldom cover leaf-level nutrient detection, seed vitality testing, fruit quality assessment, soil moisture estimation, underwater imaging, or the integration of polarization spectroscopy with deep learning, hyperspectral, multispectral, and fluorescence technologies. In contrast, this review provides the first comprehensive overview that systematically connects polarization spectroscopy principles with non-destructive detection tasks across multiple agricultural scenarios, from leaf to fruit, seed, soil, and aquaculture environments, providing a unified framework tailored specifically for precision agriculture.

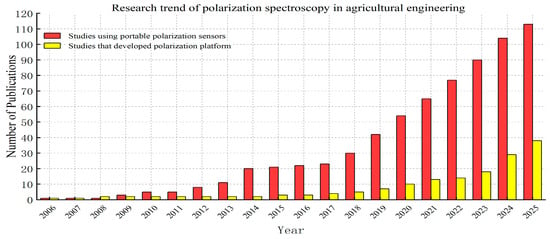

Figure 2 was generated from a reproducible literature search using the Web of Science Core Collection. Publications were retrieved by searching the title, abstract, or keywords for the terms “portable polarization sensors” or “polarization platform”. Only English-language articles published between 2006 and 2025 were included. The figure shows the cumulative number of publications from 2006 to each year, leading to an overall increasing trend. It should be noted that this trend reflects the results obtained using these specific search terms and, therefore, does not represent all polarization-related research in agriculture.

Figure 2.

Research trends in polarization spectroscopy of agricultural engineering (2006–2025).

Since the early 21st century, polarization detection has been widely studied for agricultural information monitoring. In 2017, Gastellu et al. [21] reviewed the theory of discrete anisotropic radiative transfer and its modeling mechanisms, focused on polarized light reflection and chlorophyll fluorescence. Hosseini et al. [22] applied a polarization-based model to estimate biomass and soil moisture in spring wheat fields. The total biomass predication exhibited a root mean square error of 78.834 g/m2 and an average error of 58.438 g/m2. The soil moisture estimation achieved an RMSE of 0.078 m3/m3 and an accuracy of 0.065 m3/m3. Lunagaria et al. [23] used a polarization spectrophotometer to measure the canopy anisotropy in wheat across 54 observation angles under an incident zenith angle of 60°, covering various growth stages. The results showed that, when the polarization detection angle was close to the solar zenith angle, a significant hotspot effect appeared. During the heading to flowering stages, the canopy uniformity and emergence rate were higher, making polarization imaging particularly effective for identifying phenological stages in the later growth period. Furthermore, in 2019, Xu et al. [24] used a polarization hyperspectral imaging system (400–1000 nm) combined with a PLS-DA model to successfully classify the sunflower leaf type, growth stages, and disease conditions. The R-SS index was used for leaf type classification, while R-BS was applied for growth stage identification. The vertical polarization spectra provided the best performance in disease detection, achieving a correct classification rate (CCR) of 0.963.

In 2022, Sun Zhongqiu et al. [25] conducted observations of water surfaces under different solar zenith angles and specular reflection directions in the 450–1000 nm wavelength range. By analyzing the Degree of Linear Polarization (DOLP) of the reflected light and the Fresnel reflection coefficients, they inverted the refractive index of the water. The results showed that polarization measurements could replace traditional reflectance methods, with an average relative difference of less than 3%. The inverted refractive index was highly correlated with salinity and demonstrated a high accuracy, with an uncertainty ranging from 0.9% to 1.8%. Li et al. [26] developed the leaf optical model PROPOLAR, which combines the PROSPECT model with a three-parameter function to simulate both polarized and non-polarized leaf reflectance, while the correlating biochemical and surface structural characteristics. The model was validated using a dataset of 533 samples, demonstrating good simulation performance for light intensity, BPDF, and Dolp with a maximum R2 of 0.98. PROPOLAR showed a strong capability in retrieving biochemical parameters (such as chlorophyll and moisture) and estimating the surface roughness.

In 2014, Huang Wenjiang et al. [27] used the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) derived from polarization detection to monitor the physiological stress in winter wheat leaves. The measurement was taken from the upper canopy layer at an elevation angle of 40° and 50°, the middle layer at 30° and 40°, and the lower layer at 20° and 30°. A regression model was developed based on the nitrogen reflectance index, the normalized chlorophyll index, and a combination of both. Among these, the combined index provided the predication accuracy. Wu Di et al. [28] conducted a systematic analysis of the spectral and angular distribution of polarized reflectance from vegetation canopies using ground-based multi-angle hyperspectral polarization, and also estimated the parameters of two polarization models. The results demonstrated that the polarized reflectance from vegetation canopies is strongly anisotropic and exhibits a weak dependence on the wavelength, with the measured data closely matching the model outputs.

The current polarization detection mainly targets the nitrogen level, chlorophyll concentration, and wheat field biomass. These approaches have shown promising results and have established polarization-based fixed-position canopy detection devices. With the ongoing advancement in computer technology, hardware systems significantly improved in processing large-scale data, which has accelerated the development of deep-learning techniques [29,30,31], particularly in agricultural remote sensing: recent studies [32] have demonstrated the benefits of integrating dual-polarized Sentinel-1 SAR data with multispectral optical imagery for farmland boundary extraction. By employing a cascaded deep-learning framework that combines semantic segmentation and edge detection, the method leverages the polarization-dependent scattering characteristics of SAR to enhance boundary recognition, particularly in complex agricultural landscapes. In terms of vegetation segmentation, Yang et al. [33] constructed Stokes parameters from four directional polarization measurements and calculated three channel DoLP images as model inputs; in addition, the direct input of the 0°/45°/90°/135° four polarization angle images has been tested. By using a dual-input DIR-DeepLabv3plus network to encode the light intensity and polarization features separately, the mIoU performance was improved by 0.18–1.49% under different shading conditions compared to using only the light intensity input. These results clearly demonstrate the encoding method of polarization features in deep learning and their relative performance advantages. In addition, in early season crop recognition [34], researchers used COSMO SkyMed X-band dual polarization (HH/VV) SAR data combined with 1D and 3-D CNN classifiers for crop type recognition. The experiments have shown that the 3-D CNN architecture that integrates HH + VV backscatter signals can achieve a classification accuracy of 80% in the early months and maintain an overall accuracy of over 90% throughout the entire growing season, verifying the potential of combining polarization information with deep learning in crop monitoring (Figure 3).

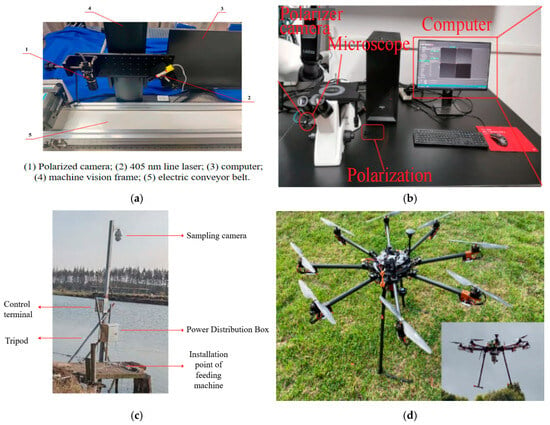

Figure 3.

Different polarization experimental systems: (a) physical image of cotton foreign fiber polarization imaging detection device [35]; (b) disease spores micro polarization image acquisition system [36]; (c) grass carp feeding system based on polarization camera [37]; (d) octocopter drone with polarization camera module [38].

Several prior reviews and key studies have addressed polarization, BRDF modeling, and remote-sensing platforms (e.g., Gastellu-Etchegorry et al. [21], 2017, on radiative transfer and DART modeling; and Sun et al. [39], 2018, on the role of polarized reflectance in vegetation BRDF). These works provide a solid theoretical and modeling foundation for polarimetric remote sensing, especially at the canopy and landscape scales. Other reviews summarize UAV platforms [40], underwater polarization [41], and non-destructive testing methods for food/pesticide screening [42], but they do not focus specifically on polarization spectroscopy for agricultural non-destructive testing.

This review offers several new contributions to the field. First, it integrates laboratory, field, and remote-sensing polarimetric spectral analysis into a unified cross-scale frame-work, linking fundamental optical mechanisms with practical agricultural monitoring scenarios. Second, this review places special emphasis on non-destructive quality monitoring, including nutrient assessment, stress detection, disease identification, seed viability evaluation, fruit and product quality inspection, and soil property estimation. Third, we summarize the advances in multi-modal fusion—combining polarization with hyper-spectral, multispectral, RGB, and fluorescence imaging—and highlight the role of machine learning and deep learning in enhancing detection accuracy. Fourth, an engineering-oriented perspective is provided by reviewing the instrumentation, measurement systems, and deployment platforms ranging from laboratory spectrometers to field polarimeters, UAV payloads, and satellite sensors. Overall, this review establishes a systematic framework that connects principles, instrumentation, data processing, and applications for polarization-based non-destructive testing in agriculture. In addition, this review covers the current trends, key challenges, and potential future research directions of this technology in agriculture [43], with the aim of offering a tutorial review for researchers and beginners in these fields to promote the further development and application of polarization spectroscopy technology in agriculture.

Literature Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

To ensure that this review is comprehensive and methodologically transparent, we performed a structured literature search across multiple scientific databases. The primary databases included Web of Science, Google Scholar, and CNKI, which, together, cover international and Chinese scientific publications. The literature search used combinations of the following keywords and search strings: “polarization spectroscopy”, “polarimetric imaging”, “polarimetric remote sensing”, “Stokes parameters”, “degree of polarization”, “angle of polarization”, “polarized reflectance”, combined with “agriculture”, “crop”, “vegetation”, “leaf”, “canopy”, “seed”, “fruit”, “soil”, “aquaculture”, “quality monitoring”, and “non-destructive testing”.

The search covered the period from 2006 to 2025, while earlier foundational studies were included when relevant to the basic optical mechanisms.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles or conference papers; (2) studies involving agricultural materials or agricultural monitoring scenarios; (3) studies applying polarization spectroscopy, polarimetric imaging, or polarimetric remote sensing; and (4) work relevant to non-destructive detection, vegetation parameter retrieval, or agricultural quality assessment.

This structured search strategy ensures that the present review captures the breadth of the research on polarization-based sensing across the laboratory, field, and remote-sensing scales within agricultural contexts.

2. The Principle and Advantages of Polarization Spectroscopy Analysis Technology

The principle of polarization detection: Polarization refers to the asymmetry between the direction of the light wave vibration and its direction of propagation. All objects on the Earth’s surface or in the atmosphere exhibit specific polarization characteristics during the processes of reflection, scattering, transmission, and emission of electromagnetic radiation. These characteristics are influenced by the physical properties of the objects and the basic principles of optics [44]. Different objects or different states of the same object, such as the roughness, porosity, water content, and physical and chemical properties of the materials, can lead to distinct polarization effects. When light interacts with the object, changes in the surface texture, internal structure, or the angle of observation can alter the polarization state of the light. These changes can enhance certain information, making it possible to extract polarization information for the more effective identification of objects [45]. Based on the vibration behavior of light waves, polarization can be categorized into natural light, linearly polarized light, elliptically polarized light [46], circularly polarized light, and partially polarized light.

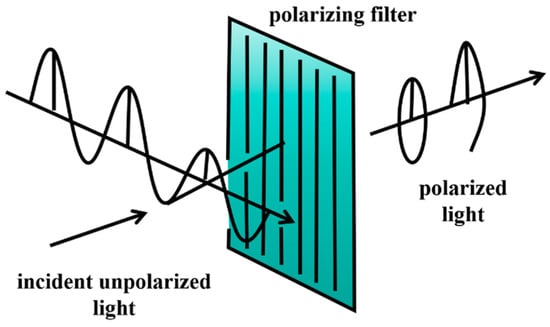

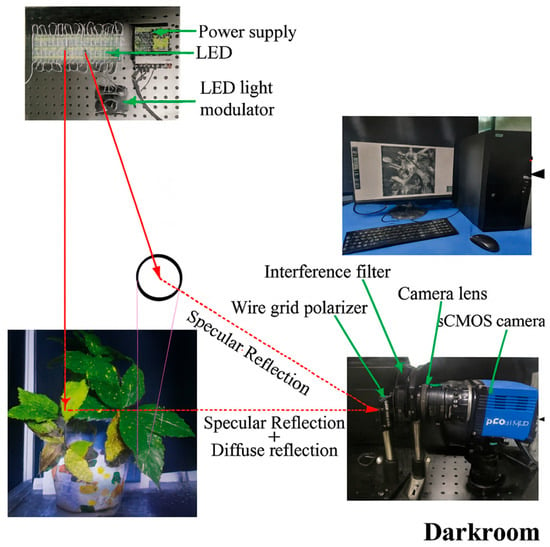

Polarimetric imaging technology captures images by utilizing polarized light that is reflected and scattered from different points on an object’s surface. In simple terms, it uses a polarizer to filter light, allowing only light with a specific polarization angle to pass through and be captured by the camera. This process enhances the visibility of the target by increasing the contrast. Polarization detection devices, such as polarimeters and ellipsometers, measure the polarization state of light and analyze it using parameters like the Stokes parameters, polarization degree, and polarization angle (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Polarization principle diagram.

2.1. Stokes Parameters

In 1852, George Gabriel Stokes proposed a vector containing four parameters to fully describe the polarization state of light. The expression of this vector is as follows [47]:

(General light intensity): The total intensity of the light, regardless of polarization state.

(Horizontal/vertical polarization components): The difference in intensity of the light in the horizontal (0°) and vertical (90°) directions.

(±45° polarization component): The difference in intensity of the light in the +45° and −45° polarization directions.

(Circularly polarized component): The difference in intensity between the left-handed and right-handed circularly polarized light.

Their calculation formula is as follows [48]:

where:

are the light intensity in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively.

are the light intensity of polarization direction +45° and −45°, respectively.

are the intensity of the left and right circularly polarized light.

Based on the principle of polarization, the polarization state of the reflected light can be influenced by factors such as the soil type, the maturity of fruits and vegetables, and the moisture content. This polarization state can be accurately measured using the Stokes parameters. Yi Jia et al. [49] used a polarization spectroscopy imaging system to obtain the multi-angle reflectance data from soybean leaves and established an experimental measurement model using the polarimetric bidirectional reflectance distribution function (pBRDF) to acquire the Stokes vector data. By calculating this, they successfully differentiate healthy leaves from diseased ones. Table 1 summarizes how different polarization parameters correspond to specific agricultural detection tasks. Overall, Stokes parameters are mainly used for structural or biochemical feature identification (e.g., chlorophyll and disease signals), while the DoP is more sensitive to moisture, canopy structure, and maturity, and the AoP is especially useful for distinguishing between orientation-related or surface-induced variations. These results indicate that different polarization descriptors provide complementary sensitivity to crop physiology and surface morphology, supporting their joint use for multi-parameter agricultural sensing.

2.2. Polarization Degree

The polarization degree (DoP) is an indicator for measuring the polarization purity of light, which represents the ratio of the polarization part of the light to the total light intensity [50]. It is defined as follows:

When DoP = 1, the light is completely polarized (such as a laser).

When DoP = 0, the light is completely unpolarized (such as natural light).

When 0 < DoP < 1, the light is partially polarized.

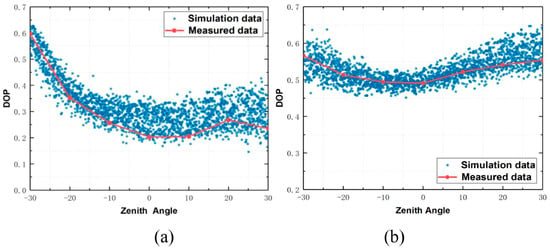

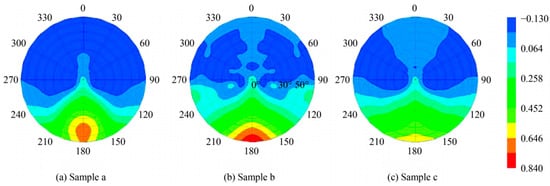

Xu Xiang et al. [51] successfully demonstrated a rapid and non-destructive method for detecting the water content in plant leaves by calculating the degree of linear polariza-tion (DoLP) based on Stokes parameters. Takruri, M et al. [52] generated degree of linear polarization (DoLP) and angle of polarization (AoP) images from captured polarization images, and employed Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models to predict the actual age of apples, achieving an average prediction accuracy of up to 92.57%. Shibayama, M et al. [53] examined the polarization characteristics of wheat canopies by calculating the degree of polarization (DoP) for each image pixel and generating polarization images. Their results revealed a clear correlation between the DoP and factors such as the leaf tilt angle, leaf area index (LAI), and chlorophyll content (SPAD value). In 2024, He, QY et al. [54] developed a pBRDF model for plant canopies, generating fitted images of the polarization degree changes with the zenith angle. Data inversion on the canopies of Christmas blue cabbage and hibiscus resulted in root mean square errors of 2.3% and 1.1%, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Comparison between measured and simulated data for Plant 1 (a) and Plant 2 (b) [54].

2.3. Polarization Angle

The polarization angle (AoP) describes the angle of the polarization direction of light. The calculation formula is as follows:

It indicates the main vibration direction of the polarized light, which is closely related to the structure and orientation of the material. YH Kim et al. [55] proposed a rice paddy extraction method using β, POA, and H.

Table 1.

Application of Stokes parameters, polarization, and polarization angle in agricultural material analysis.

Table 1.

Application of Stokes parameters, polarization, and polarization angle in agricultural material analysis.

| Application Area | Stokes Parameter | Degree of Polarization | Polarizing Angle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop health monitoring | Chlorophyll content [56], Disease identification [57] | Disease detection [36] | Seed germination test [58] |

| Soil quality assessment | Soil moisture content [59] | Soil moisture [60] | Soil pollution [61] |

| Agricultural product maturity testing | Fruit maturity [62] | Maturity, freshness [63] | Surface condition of fruit [64] |

| Food quality testing | Pig’s egg quality [65] | Classification of vegetable oils [66] | Quality inspection [52] |

2.4. Differences and Advantages Between Polarized Spectroscopy and Traditional Spectroscopy (Visible Light, Near-Infrared, Etc.) in Detection Ability

2.4.1. The Difference Between Polarization Spectrum Analysis Technology and Other Typical Non-Destructive Testing Technologies

With the advancement in computer and wireless sensing technologies, various rapid non-destructive testing techniques have become a research focus in agricultural engineering [67,68,69,70,71,72]. Compared with traditional spectral techniques such as visible and near-infrared spectroscopy, polarization spectroscopy offers distinct detection mechanisms. Traditional spectroscopy typically relies on variations in the spectral reflectance at specific wavelengths to extract information [73]; imaging technology mainly relies on macroscopic physical properties such as color and shape [74]; and thermal imaging methods capture temperature-related data from leaves or crop canopies [75]. However, these monitoring methods only capture partial characteristics when crops are affected by disease or stress, leading to incomplete or limited data and poor interference resistance, and they cannot fully represent the rich characteristic information of agricultural materials. Moreover, during image or spectral analysis, challenges such as “different spectra from the same object” and “similar spectra from different objects” frequently occur. These issues introduce uncertainty in determining specific parameters, thereby limiting the reliability and practical application of precise crop monitoring technologies. High-spectral technology, as one of the most advanced detection methods, effectively integrates spatial, radiometric, and spectral information, making it a hotspot in research. For instance, the application of high-spectral technology in detecting crop diseases has resulted in progress [76]. Currently, research on using high-spectral technology for detecting crop diseases primarily focuses on the spectral variations that occur after crops are affected by diseases after infection [77]. This involves identifying the relationship between the disease severity and alterations in both original spectra and derivative spectra, determining the sensitive spectral bands for monitoring different crops and diseases, and evolving from qualitative assessments to quantitative and spatial-based monitoring through mathematical models, achieving preliminary results [78]. However, high-spectral disease detection still faces several pressing issues: first, the theoretical understanding of the luminescence patterns under biological molecular stress in fungal diseases is not yet clear; the theoretical analysis techniques for high-spectral images are not fully developed and require further in-depth research; and it is also necessary to establish characteristic spectra specific to different diseases to facilitate the practical application of high-spectral imaging technology.

The physical and chemical changes in crops caused by growth, reproduction, nutritional deficit, infection, and disease are complicated [79]. During detection, intensity and polarization information often exhibit a negative correlation: when the reflection intensity is high, the polarization degree is low; conversely, when the reflection intensity is not significantly different, the polarization direction may change markedly. This information’s complimentary nature provides new perspectives on crop detection. Effective integration and machine analysis that integrates both intensity and polarization data are still lacking.

2.4.2. Advantages of Polarization Spectrum Analysis Technology

In short, the polarization spectrum analysis technology integrates the dual advantages of spectral analysis and polarization measurement, showing significant technical characteristics and application value in many directions of agricultural material detection. Its core advantages can be summarized as follows:

- High detection sensitivity and revealing microscopic characteristics

By analyzing changes in the polarization state such as the polarization direction and ellipticity, after the interaction between light and the target object, it is possible to detect birefringence, stress distribution, surface roughness, and microstructural heterogeneity in agricultural products, thereby revealing the physical properties that are invisible to conventional imaging methods and undetectable through intensity-based imaging [80].

- Enhance contrast and anti-interference

By separating the polarization state information, background noise (such as greenhouse [36], glass reflection [81], underwater [82], rainy season farmland [83], etc.) can be effectively suppressed, and the recognition accuracy of farmland and fish pond environments can be improved [37]. Moreover, the imaging quality can be maintained even under low-light or complex environmental conditions [84].

- Enhance the ability to form an early diagnosis

By analyzing the polarized reflectance properties of leaves, physiological changes such as water stress and nutrient deficiencies can be detected, and with a significantly higher sensitivity than traditional optical methods. For example, in the early detection of the water content change in holly leaves, the regression index and the coefficient of determination of the water content reached 0.95 [51] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Optical images and corresponding local deflection index images of leaves with different water contents [51].

- Comprehensive information fusion

The integration of polarization spectroscopy with other techniques allows for the combination of multiple data sources. For instance, when combined with high-resolution optical remote sensing images, it can identify crop-planting areas [85] and monitor growth conditions [84] more accurately. When integrated with meteorological data, it can help analyze the water requirements and stress levels of crops [86]; when used together with fluorescence polarization imaging, it can detect plant growth conditions. This complementary use of different data sources significantly improves the accuracy and reliability of agricultural monitoring.

2.4.3. Classification of Polarization Spectroscopy Analysis Technique

Based on the techniques and characteristics of data collection, polarimetric spectroscopy technology can be divided into two primary categories: polarimetric spectrometry and polarimetric imaging spectroscopy. Polarimetric imaging spectroscopy primarily focuses on obtaining polarized information about the spatial distribution and structure of crops, making it suitable for the rapid detection and diagnosis of crop growth conditions [10], and diseases and pests [36]. On the other hand, polarimetric spectrometry focuses on the analysis and extraction of spectral information, using the spectral characteristics of polarized light to obtain information about the biochemical components and physical structure [87] of crops.

The technology of polarization spectroscopy has a lot of potential uses in field crop monitoring. It is expected that polarization spectroscopy technology will become more significant in agricultural production in the future due to its ongoing development and advancement, which will help to increase agricultural production efficiency and guarantee food security.

Existing polarization spectroscopy studies in agriculture vary widely in terms of sensing modality, illumination strategy, measurement scale, and application target. Passive methods are simple and suitable for field monitoring but are highly sensitive to illumination variability, whereas active systems ensure stability but are typically limited to laboratory environments. Spectral PSA offers high spectral fidelity but lacks spatial information, while imaging-based PSA provides structural and spatial features but often with a narrower spectral coverage. Laboratory devices offer high precision for mechanism studies, whereas field and remote-sensing instruments emphasize portability and large-scale monitoring but face challenges such as noise, atmospheric effects, and a reduced resolution. A structured classification of these technologies is, therefore, essential in order to understand their respective strengths, limitations, and appropriate application scenarios. Table 2 provides a comprehensive comparison across the passive/active, spectral/imaging, and laboratory/field categories.

Table 2.

Classification and characteristics of polarization spectroscopy technologies used in agricultural detection.

3. Application in Crop Health and Disease Detection

3.1. Chlorophyll Content Monitoring

Changes in chlorophyll, which is essential to plant photosynthesis, can reveal important information about crop growth and overall health. Accurate nitrogen fertilizer management requires a precise assessment of the photosynthetic capacity and nutritional status, which, in turn, depends on an accurate estimation of the leaf chlorophyll content (LCC) [88]. Polarized light spectroscopy provides enhanced sensitivity to the leaf-surface microstructure and internal optical properties, making it particularly suitable for chlorophyll detection.

The current research on polarization-based chlorophyll monitoring mainly includes three aspects: (1) leaf-level multi-angle polarized spectral measurements, (2) the application of polarization spectroscopy in complex aquatic environments, and (3) the fusion of polarization features with photometric or remote-sensing parameters. Representative studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Application of polarization spectrum analysis technology in the detection of chlorophyll.

At the leaf scale, Meng Xia et al. [56] used apple, ginkgo, and pothos leaves to obtain multi-angle polarized spectra with an ASD FieldSpec Pro FR spectrometer (400–1800 nm). The Stokes vector method was applied to derive multi-angle spectral polarization, and the PROSPECT model was used for chlorophyll inversion. Their results demonstrated that polarized spectra reveal structural and biochemical information not captured by conventional reflectance, thereby improving the LCC estimation accuracy. Compared with traditional spectroscopy, polarized light spectroscopy also offers advantages in aquatic chlorophyll monitoring, where confounding factors such as suspended sediments, scattering background, and dissolved pigments make retrieval difficult. Zhu Jin et al. [89] measured the polarization and reflectance spectra in both Chaohu Lake (a highly complex water body) and a single-leaf green algae suspension. By analyzing the multi-angle polarization spectra (0°, 60°, and 120°), they found that polarization features correlated more strongly with the chlorophyll concentration than reflectance spectra, largely because polarization helps mitigate the interference from other optically active substances.

Further extending the polarization-based water applications, Pang Huifang et al. [90] used polarization discrimination to separate chlorophyll fluorescence from the total scattering spectrum. They examined how inorganic particles (IOPs) and chlorophyll concentrations jointly affect fluorescence extraction. Their results showed that increasing IOP concentrations suppressed the fluorescence peak, highlighting the importance of polarization in fluorescence isolation. This work suggests that polarization methods can improve chlorophyll detection even in highly turbid coastal or inland waters. In addition to leaf- and water-scale studies, several researchers have explored integrating polarization features with photometric and canopy-scale remote-sensing information. Yao Ce et al. [91] proposed a new combined spectral index using the bidirectional reflectance factor (BRF) and the inverse of the degree of linear polarization (1/DOLP). This index explained over 90% of the LCC variation—significantly outperforming indices derived from reflectance alone. Huang et al. [86] used multi-angle polarized remote sensing to acquire the canopy reflectance and polarized spectra together with ground-measured LCC. By employing polarization reflectance models (NB and M models) to separate specular components, they improved the robustness of the vegetation indices used for chlorophyll inversion. Finally, Xu Jiayi et al. [92] investigated near-infrared polarization spectroscopy for non-destructive chlorophyll detection in jujube leaves. Their predictive model showed the best performance under 0° polarization conditions, with a correlation coefficient (Rc) of 0.53646, indicating that polarization retains useful sensitivity for chlorophyll estimation despite its relatively low prediction error.

Overall, these studies demonstrate that polarization spectroscopy enhances chlorophyll monitoring by reducing specular interference, isolating fluorescence signals, improving sensitivity to structural differences, and strengthening the stability of inversion models across angles, environments, and platforms.

3.2. Leaf Moisture Detection

Water deficiency in crops can lead to stomatal closure and reduced photosynthetic efficiency, ultimately limiting growth and productivity [93]. The accurate and stable monitoring of the leaf water content is, therefore, critical for crop stress diagnosis and precision irrigation. Polarization-based methods have recently attracted attention due to their sensitivity to leaf surface structures, internal water distribution, and microstructural changes associated with dehydration. In 2017, Li Xiaolu et al. [94] utilized laser polarization imaging to establish a mapping between the leaf water content and degree of polarization, showing a clear positive trend in the polarization degree for moisture levels ranging from 15% to 75%, particularly at higher water contents, indicating an enhanced sensitivity and stability of measurement in the mid-to-high moisture range (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Measurement of moisture content using laser polarization system: (a) optical path of laser polarization imaging measurement system [94]; (b) optical path of the polarized active imaging system [95].

Similarly, Xie Xin Hao et al. [95] applied polarized active-imaging LiDAR to wintergreen leaves, combining polarization mapping with SURF matching, affine transformation, and iterative filtering to reduce noise. Their study confirmed a strong positive correlation between the polarization degree and leaf water content (45–75%) and demonstrated that an exponential model could reliably represent this relationship for field applications.

However, species, leaf structure, and environmental factors can influence the polarization–water relationship. Xu Xiang et al. [96] investigated leaves subjected to gradient drying across different growth stages, positions, and weather conditions, finding a significant negative correlation between the degree of linear polarization and water content (R = 0.85, MSE = 0.45%), with their predictive model achieving an average relative error of 9.50% and RMSE of 4.53%. These findings suggest that, while polarization-based methods are promising for non-destructive leaf water monitoring, calibration specific to species and environmental conditions is necessary in order to ensure accurate and reliable measurements.

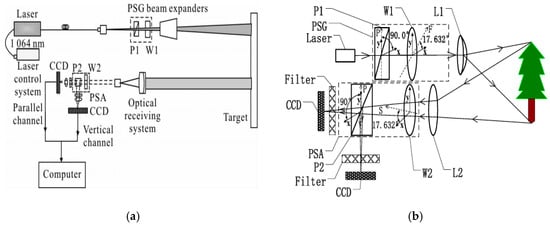

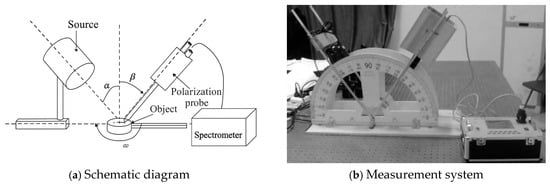

3.3. Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Content Detection

Plants exhibit subtle variations in their optical properties under conditions such as nitrogen deficiency, nutrient imbalance, or temperature stress. The accurate and timely monitoring of the leaf nitrogen content is, therefore, essential for evaluating crop nutritional status and guiding precise fertilization strategies [13]. In recent years, polarization spectroscopy has demonstrated clear advantages in nitrogen estimation by reducing specular-reflection interference and enhancing the sensitivity to structural changes at both the leaf and canopy levels. At the canopy scale, Liu Siyuan et al. [97] demonstrated that polarization information can correct scattering distortions caused by leaf-surface specular reflections—an issue particularly prominent in heterogeneous canopy structures. By refining the scattering coefficient with the polarized reflectance (Rp) and evaluating six BPDF models over 400–2500 nm, they showed that polarization correction significantly improves the estimation accuracy in both the visible and SWIR regions, reducing CNC RMSECV by 1.19%. This represents a clear advantage over non-polarized canopy measurements, where structural effects typically reduce nitrogen sensitivity. In contrast, at the leaf scale, polarization behaves differently: instead of correcting canopy-level scattering, it helps disentangle surface reflectance from biochemical absorption features. Liu Ming et al. [98] captured multi-angle polarized hyperspectral data from six plant species and proposed the non-polarized reflectance factor (NpRF) as a more stable indicator for the leaf nitrogen concentration (LNC). Unlike canopy studies where polarization is retained for correction, here, removing the polarized component actually enhances the biochemical sensitivity. NpRF achieved an R2 of 0.82 in the red-edge region—far higher than the traditional method (R2 = 0.65)—and reduced RMSE to 0.17 N% (Figure 8). This contrast highlights that polarization plays different roles at different biological scales: correction at the canopy level versus purification of biochemical signals at the leaf level.

Figure 8.

(a) Laboratory measurements. (b) System diagram of measurements in the principal plane, where φv = 180° corresponds to the forward scattering direction. SZA and VZA correspond to SZA and VZA, respectively. (c–e) Multiangle photometric and polarimetric measurements under different incident conditions in the principal plane in the field. The two ASD spectrometers are used to measure photometric and polarimetric signals from leaves and to measure the reflected radiance from a Spectralon panel with the same measurement geometry, respectively [98].

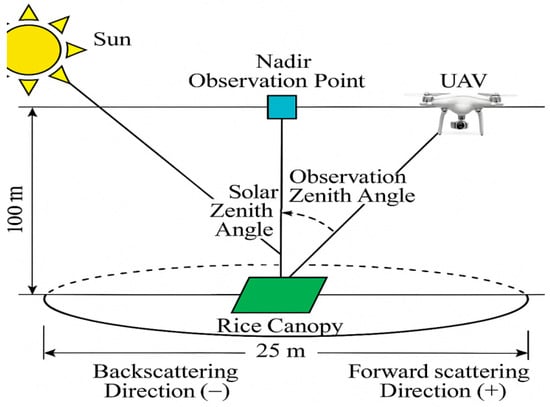

Ground-based hyperspectral imaging further extends this contrast by showing how polarization preprocessing improves algorithmic performance. Zhang, ZH et al. [99], using HySpex data, demonstrated that removing polarized reflection increased the overall nitrogen inversion accuracy by 244%. The random forest model improved by 103% (R2 = 0.803; RMSE = 0.252), outperforming PLSR by 32% and achieving an overall accuracy gain of 440%. Compared with both leaf- and canopy-based analyses, this work emphasizes that polarization correction is not only biologically meaningful but also algorithmically beneficial. Moving from ground to aerial platforms introduces another dimension of contrast—directionality. UAV-based observations can exploit optimal viewing geometries that are not accessible on the ground. Xu Tongyu et al. [100] used a UAV-mounted polarization spectral system to collect rice canopy data at angles from −60° to 60° and found that nitrogen–polarization correlations peaked at a 15° zenith angle. The linear inversion model achieved R2 = 0.7838 with RMSE values of 0.428 mg/g (training) and 0.662 mg/g (validation) (Figure 9). This angular dependence contrasts with leaf-level studies, where angle effects are much weaker, and demonstrates that polarization sensitivity is scale- and geometry-dependent.

Figure 9.

Schematic diagram of multi-angle observation of rice canopy polarization spectrum [100].

Finally, early nutrient-stress detection studies add another layer of contrast by shifting from a quantitative estimation to qualitative physiological diagnosis. In 2014, Zhu Wenjing et al. [101] examined greenhouse tomatoes under different N–P–K deficiency conditions and identified key polarization parameters that respond sensitively to early nutrient stress—long before visible symptoms appear. Similarly, Mao Hanping et al. [102] used a polarization reflectance–light distribution angle system to quantify N and K in fresh tomato leaves, confirming that polarization enables rapid and non-destructive nutrient diagnosis. Compared with canopy and UAV applications, these studies emphasize the diagnostic value of polarization rather than purely quantitative inversion.

3.4. Identification and Monitoring of Pests and Diseases

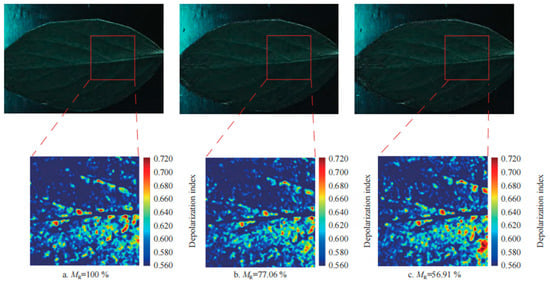

The timely and accurate detection of plant diseases and pests is crucial for reducing crop losses and enabling effective management strategies [103]. Polarized spectroscopy offers unique advantages in this context because both disease infections and insect activities can alter the spectral and polarization properties of leaves and other biological targets, allowing subtle physiological and structural changes to be detected at early stages. At the leaf level, imaging polarimetry techniques such as Mueller matrix polarimeters and combined reflectance-polarization imaging have been successfully used to identify infections before visual symptoms appear. For example, Alireza Pourreza et al. [104] employed weekly polarized imaging to detect pre-symptomatic HLB infection in citrus leaves, while Carla et al. [57] applied depolarization parameters to enhance the contrast in alfalfa and olive leaves infected with mosaic virus or leaf-spot fungus. Similarly, Xu Qian et al. [105] combined 660 nm reflectance imaging with 590 nm polarized transmission imaging and used Stokes parameters to detect internal starch-related abnormalities, achieving classification accuracies of up to 96.67%.

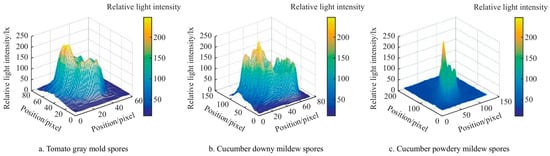

Beyond the leaf-level diagnosis, polarization-based techniques have also been applied to monitor insect pests and airborne pathogens. Zhu et al. [106] demonstrated that a polarization-sensitive LiDAR system could track flying pests in rice fields over several hundred meters, providing high-resolution temporal activity patterns under varying environmental conditions. Wang Yafei et al. [36] developed a polarization imaging approach for classifying greenhouse spores with a back-propagation neural network, achieving an average recognition accuracy of 86.67% for multiple fungal pathogens. Collectively, these studies illustrate that polarized spectroscopy can provide the rapid, non-destructive, and highly sensitive detection of both plant diseases and pest activity, highlighting its potential as a powerful tool for precision agriculture (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Relative light intensity distribution of polarization images of diseased spores [36].

4. Non-Destructive Testing of Quality of Agricultural Products and Seeds

4.1. Quality Testing of Agricultural Products

Polarimetric spectroscopy exploits the polarization properties of light interacting with agricultural products to assess quality attributes such as freshness, crispness, and internal structure. By analyzing how polarized light passes through the skin and flesh of fruits, vegetables, and seeds, subtle details such as the cell arrangement, flesh density, and surface smoothness can be revealed. Early work by Huazhong Agricultural University [107] developed a non-destructive high-incident-angle polarization imaging method to monitor egg freshness. Using images from 200 eggs, they extracted the polarization features and established a model correlating these features with storage time, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.995 and an accuracy of 92%. Similarly, Lin Fenfang et al. [108] employed a field imaging spectrometer with a polarizer (FISS-P) to distinguish corn from five common weeds under laboratory conditions. By capturing spectral images at multiple polarization angles (0°, 60°, 120°, and unpolarized) and performing radiation normalization, their models achieved an overall accuracy and Kappa coefficients above 90%, with the 0° polarization angle yielding the highest accuracy (98.2%, Kappa = 0.98), highlighting polarization’s ability to differentiate crops from weeds based on the leaf surface roughness and waxy layers.

Polarization imaging has also been applied to detect physical defects and the internal quality of seeds and beans. Yu Yang et al. [64] used multi-angle polarization image fusion with a Ghost module-based network to suppress glare and enhance damaged area recognition efficiently. Huang Shizhao et al. [87] collected polarized images of red beans and calculated Stokes vectors (S0, S1, and S2) to characterize the surface properties. Normal beans exhibited a consistent polarization reflection and lower brightness variation, while wrinkled or defective beans showed less variation due to irregular surface roughness, enabling the more accurate identification of shape defects compared to traditional color sorting. More recently, Di et al. [109] applied a spectral inversion correction method based on the BPDF model, collecting multi-angle polarized spectral data (900–1750 nm) and applying CARS-PLS modeling. The approach significantly improved the prediction accuracy for the water content and soluble solid content, with certain models achieving RPIQ values of up to 2.64, demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-polarization fusion combined with BPDF-based correction.

Given the diverse quality attributes and structural characteristics of agricultural products, researchers have explored various polarization-based imaging and spectroscopic approaches to reveal features that are difficult to capture with traditional optical methods. Table 4 summarizes representative applications and key outcomes, demonstrating how polarization information improves defect detection, product grading, and classification accuracy under a range of measurement conditions.

Table 4.

Application of polarization spectrum analysis technology in quality detection of agricultural products.

Investigating the authenticity and classification of edible oils is crucial. Geng Dechun et al. from Jiangsu University [110] used six types of edible oils—rapeseed oil, soybean oil, peanut oil, sunflower seed oil, camellia oil, and sesame oil—to explore the application of polarization-induced two-dimensional correlation fluorescence spectroscopy in the rapid classification of edible oils. By altering the polarization angle to obtain the fluorescence spectra, they used MATLAB (R2018) for the two-dimensional correlation analysis to generate the synchronous and asynchronous spectra. The results showed that this method significantly enhances the spectral resolution, accurately distinguishes different oils, and has high practical value.

These studies illustrate that polarimetric spectroscopy provides a non-destructive, highly sensitive means of evaluating both the external and internal quality attributes of agricultural products, surpassing conventional imaging and spectral methods in accuracy and robustness.

4.2. Seed Non-Destructive Testing

Seed vitality is a crucial aspect of agricultural research [111]. Seed quality is essential for optimizing crop planting costs. Therefore, it is necessary that we develop rapid and non-destructive methods for seed quality testing in the agricultural and seed production sectors [112]. Polarized light detection is a non-contact method that does not cause any physical damage to seeds. The research is shown in Table 5. In 2016, Cheng Yuqiong et al. [58] utilized continuous polarized light spectroscopy to evaluate the rice seed germination rates, selecting three characteristic polarization angles (0°, 5°, and 25°) and wavelengths (576 nm, 620 nm, and 788 nm) to construct a three-dimensional spectral model (polarization angle–wavelength–transmittance). Among three modeling approaches—partial least squares regression, the BP neural network, and the radial basis function neural network—the radial basis function model achieved the highest accuracy, demonstrating the strong sensitivity and modeling capability of polarized spectra for seed germination assessment. Building on this, Wang Xinyu et al. [113] developed a portable rice seed germination detector based on the STM32 microcontroller and polarized light spectra, achieving a prediction accuracy over 90% for various rice varieties.

Table 5.

Application of polarization spectrum analysis technology in seed non-destructive testing.

Recent advances have further enhanced both speed and functionality. Wang et al. [35] combined line laser polarization imaging with an improved YOLOv5 algorithm (integrating ShuffleNetv2, modified PANet, and Coordinate Attention modules) to achieve the real-time detection and classification of foreign fibers in cotton, demonstrating the potential for practical online quality control. Hu et al. [114] applied polarization hyperspectral imaging (PHI) from 396.1 to 1044.1 nm and optimized the polarization components (I, Q, and U) in machine-learning models, achieving prediction accuracies of 97.17%, 98.25%, and 97.55% for seed vitality, highlighting the ability of polarized hyperspectral methods to provide a rapid and reliable non-destructive assessment.

5. Soil and Environmental Monitoring

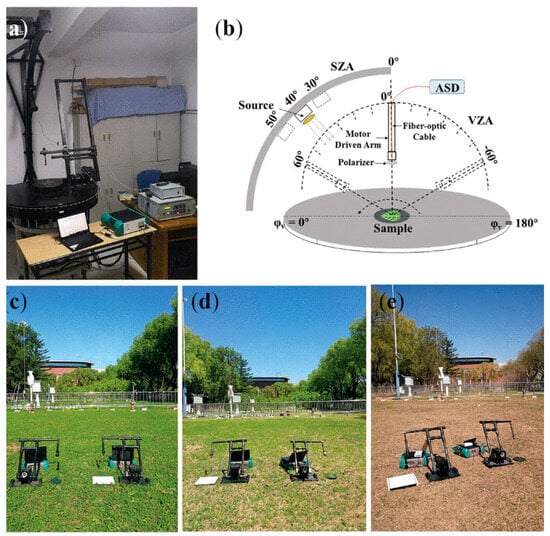

5.1. Soil Moisture

Surface soil moisture is a critical parameter for climate change research and precision agriculture [115]. Advances in remote sensing over the past decades, particularly the integration of multiple spectral bands (visible, and near-infrared) with polarization techniques, have enabled the more accurate and non-destructive estimation of soil moisture (Table 6) [116]. Polarization-based methods exploit changes in light scattering and reflectivity caused by variations in soil dielectric properties and moisture content, providing valuable information for quantitative soil moisture retrieval. Luo et al. [117] developed the Radar Vegetation Index (RVI) and incorporated it into the Water Cloud Model (WCM) to effectively remove vegetation effects from backscattering, deriving a more accurate soil backscattering coefficient, σ0 (soil). Using the Chen model, they established a semi-empirical soil moisture estimation method that performed well even in cloud-covered regions, achieving an RMSE of 0.05 and a correlation coefficient of 0.69. Similarly, McNairn et al. [60] employed Compact Polarimetry (CP) radar data combined with the Integral Equation Model (IEM) to estimate soil dielectric constants and retrieve soil moisture. Validation at Canadian soil monitoring stations yielded correlation coefficients of 0.76 and 0.82 for the 0–5 cm and 5 cm layers, respectively. At the laboratory scale, Wang Xinqiang et al. [118] applied Stokes parameters and the Mueller matrix theory to extract polarization information from red soil samples, identifying the polarization degree (PPP) as a primary parameter for characterizing soil reflectivity. Within the 600–800 nm range, the polarization degree showed a strong sensitivity to soil moisture between 14% and 30%, making it suitable for moisture inversion. (Figure 11).

Table 6.

Application of polarization spectrum analysis technology in soil moisture monitoring.

Figure 11.

Structure diagram of polarization measurement system [118].

In 2016, Ye Song et al. [119] further explored polarized light spectroscopy for soil moisture monitoring, analyzing how observation angles and soil moisture levels affect polarization characteristics. They found that, at high moisture, both the polarization degree and reflectance increase with the water content, whereas, at low moisture, reflectance first decreases and then increases with increasing soil moisture. In 2018, Zhang Ying et al. [120] subsequently developed a semi-empirical polarization reflectance model that accurately describes the soil surface reflectivity, confirming the feasibility and high accuracy of polarization-based soil moisture inversion.

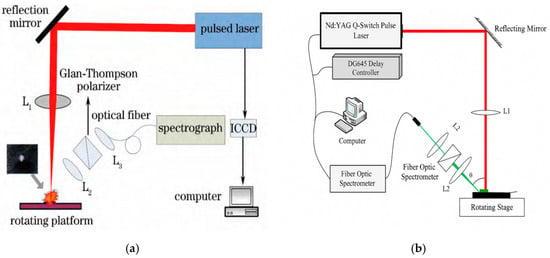

5.2. Farmland Pollution Detection

Heavy metal pollution in farmland soil, driven by human activities and natural factors, has become a critical environmental concern [121]. Pollutants containing heavy metals can alter both the polarization characteristics and optical properties of soil, enabling the detection and preliminary assessment of contamination levels using polarized light techniques. In 2018, Yu Yang et al. [122] applied laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) with polarization analysis to examine four elements (Fe, Pb, Ca, and Mg) in soil. They found that continuous background radiation exhibited higher polarization degrees (0.64–0.70) compared to characteristic spectral lines (0.17–0.27), indicating that polarized LIBS can enhance heavy metal detection by reducing background interference and improving spectral signal quality (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of experimental setups for LIBS and PRLIBS: (a) schematic diagram of LIBS polarization experimental system [122]; and (b) the experimental system of PRLIBS [123].

Building on this, Cheng Dewei [123] investigated polarization-resolved LIBS (PRLIBS) using a nanosecond pulsed laser and optical fiber spectrometer on both aluminum alloy and soil samples. By adjusting parameters such as the energy density, detection angle, wavelength, and delay time, the study revealed their effects on the signal-to-background ratio (SBR) and polarization degree, demonstrating the feasibility of PRLIBS for efficient soil heavy metal monitoring, particularly in challenging conditions such as oil-contaminated soils.

In addition to heavy metal pollution, soil salinization presents significant agricultural challenges. Gu et al. [124] studied saline-alkaline soils by collecting multi-angle polarized reflectance (Rp) spectra under laboratory conditions. They applied semi-empirical BPDF models (Nadal–Bréon, Litvinov, and Xie–Cheng) and machine-learning techniques, including support vector regression (SVR), random forest (RF), and deep neural networks (DNNs), to predict soil reflectance. A comparison with the measured values showed that machine-learning-enhanced BPDF models outperformed traditional semi-empirical models, with the prediction accuracy improved by 3.06% at 670 nm and 19.75% at 865 nm, highlighting the potential of deep learning combined with polarization information for the accurate monitoring of saline-alkaline soils.

In the reviewed literature, a variety of physical models, semi-empirical reflectance models, and machine-learning approaches—including PROSPECT, PROPOLAR, BPDF variants, SVR, PLS-DA, RF, and deep-learning networks—have been applied to agricultural material detection. Overall, the comparison indicates clear trade-offs among interpretability, computational cost, and predictive accuracy across different agricultural conditions.

Physical radiative transfer models such as PROSPECT and PROPOLAR provide strong biophysical interpretability and high simulation accuracy (R2 up to 0.98 for PROPOLAR in moisture retrieval [34]) but require complex parameterization and higher computation. Semi-empirical BPDF models (Litvinov, Xie–Cheng, and Nadal–Bréon) offer more flexibility under outdoor multi-angle conditions and have demonstrated significant performance improvements—e.g., increasing RPIQ from 40% to 60% in multi-polarization inversion tasks [109]—but their accuracy depends strongly on angular configurations. Machine-learning approaches such as SVR, PLS-DA, and RF generally provide faster computation and robustness to noise, achieving a high accuracy in applications like soil salinity prediction [124]. Finally, deep-learning methods (e.g., ResNet-G18, and improved YOLOv5) yield the highest recognition accuracy (up to 96–99%) and strong feature extraction capability but require large datasets and higher computational resources.

These comparisons suggest that no single model is universally optimal; instead, the choice should be tailored to the detection target, sensing environment, available computational resources, and need for interpretability versus performance.

5.3. Underwater Research

Underwater environments in agriculture—such as paddy fields, rice paddies, and other water bodies supporting the growth of rice, lotus, and aquatic organisms—present highly complex optical conditions where the image color, brightness, and contrast are severely degraded [125]. These challenges significantly limit the effectiveness of traditional imaging methods. Polarimetric imaging, however, can enhance the remote sensing capability of water bodies [126] and effectively suppress underwater scattering [127]. To address underwater scattering and image degradation, Guan, JG, et al. [128] developed a polarization differential imaging method utilizing the differences in polarization angles between the background scattered light and target-reflected light. Based on Malus’ law, they established a physical model demonstrating that background scattering can be effectively suppressed when its vibration direction forms a 45° angle with the analyzer’s two orthogonal polarization directions. By introducing the Stokes vector theory, the authors replaced the traditional mechanical rotation with a computational polarization differential imaging system, substantially improving the imaging speed, reducing the scattering-induced blur, and extending the underwater detection range. Building on physical modeling, Qian et al. [129] integrated a degradation model, polarization recovery, and spectral fusion, enabling the simultaneous enhancement in clarity and color reproduction. Their method outperformed traditional enhancement approaches across subjective and objective metrics, showing a strong adaptability to varying materials and imaging distances—highly suitable for complex agricultural underwater scenes.

Polarimetric techniques have also demonstrated value in large-scale aquatic ecosystem monitoring. Wang Xiaobin et al. [82] used a self-developed shipborne polarized marine LiDAR system, validated by video imaging, to analyze the optical and spatial distribution characteristics of jellyfish. Jellyfish were found to exhibit distinct backscattering rate patterns in different waters, clustering within the same water body and exhibiting Gaussian vertical distribution, confirming the effectiveness of polarized LiDAR for biological monitoring.

Further advancements in underwater polarization imaging were reported by Pan et al. [130], who employed a bottom-up imaging strategy using the Underwater Polarization Imaging System (UPIS) equipped with a SALSA camera and attitude sensor. An evaluation under various polarization parameters showed that the angle of polarization achieved the highest detection performance, attributed to differences in the target surface diffuse reflectance to polarized components of the Stokes vector. Gui, Xinyuan et al. [131] expanded polarization imaging to multi-turbidity conditions by constructing underwater polarization datasets at different turbidity levels and proposing a sliding-window superposition method. Combined with deep learning, their approach effectively restored images under multi-turbidity environments, overcoming the limitations of conventional underwater restoration techniques. Addressing additional interference factors, Song Qiang et al. [132] investigated polarization–intensity changes under varying bubble thicknesses and developed a polarization-feature-based fusion method that preserved visual detail while suppressing bubble-induced distortion, significantly improving the recognition and clarity of underwater targets.

In aquaculture applications, polarimetric imaging improves the robustness of behavioral monitoring under natural lighting conditions. Liu Shijing et al. [37] used a polarization camera to capture grass carp feeding behavior under four polarization angles (0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°). By selecting the angle with minimal reflection interference based on brightness and saturation, the method effectively reduced the impact of ambient outdoor light, enhanced image clarity, and improved the reliability of subsequent optical-flow feature extraction and behavior classification.

6. The Combination of Polarized Spectroscopy with Other Technologies

6.1. Polarization and Hyperspectral Combination

High-spectral polarization, integrating hyperspectral and polarization imaging, has become an emerging technology attracting significant interest across various scientific fields [133,134]. By simultaneously capturing spectral signatures and polarization characteristics, it provides a more complete description of material properties, enabling the fine discrimination of microstructural changes on leaf surfaces while offering rich spectral information [135]. This multi-dimensional information considerably improves the nutrient estimation accuracy and enhances the ability to detect plant stress (Table 7).

Early studies demonstrated the feasibility of applying polarization–hyperspectral fusion to nutrient assessment. Zhu Wenjing et al. [136] extracted polarized spectral features and hyperspectral texture information from tomato leaves under different N, P, and K stress treatments and established a quantitative diagnostic model using SVR. Their results confirmed that integrating polarization and hyperspectral data enhances the nutrient stress detection accuracy. Similarly, Pan Qian et al. [137] investigated farmland soils in Northeast China and found that a higher soil fertility corresponds to a lower polarization reflectance, indicating the suitability of polarization information for reflecting soil nutrient conditions. Using a BRDF measurement platform combined with an ASD hyperspectral instrument, they conducted multi-angle polarization experiments and analyzed reflectance–polarization curve variations under different conditions, providing theoretical support for quantitative remote sensing.

Subsequent research continued to validate and expand these findings. Wang Lingzhi et al. [138] analyzed how polarization at different measurement angles affects soil reflectance and used machine learning to build a soil fertility prediction model. Their results showed that integrating hyperspectral spectra with polarization parameters significantly improved the prediction accuracy. Yang Wei et al. [85] further demonstrated the strong discriminative ability of polarization hyperspectral data by collecting multi-angle polarization hyperspectral measurements (350–2500 nm) from five dry plant species and three soil types. By combining Spectral-HOG and Spectral-E features with hierarchical clustering, they achieved the accurate classification of all eight subjects, highlighting the enhanced recognition capability for both vegetation and bare soils.

Research has also expanded to nutrient estimation at different growth stages. In 2020, Zhu Wenjing et al. [139] from Jiangsu University used polarization hyperspectral fusion to predict the soluble sugar (SS), total nitrogen (N), and SS/N ratio in greenhouse tomato leaves across five growth stages and nitrogen treatments. The SS/N model showed the best predictive performance, and SVM models combining polarization and spectral features outperformed single-feature models, demonstrating the effectiveness of multidimensional polarization hyperspectral detection for nutrient stress assessment.

Polarization hyperspectral technology has also supported studies of plant fluorescence and crop canopy remote sensing. Hao Tianyi et al. [140] used a multi-angle indoor fluorescence observation platform equipped with a polarizing lens and spectrometer to measure the fluorescence spectra of spider plants, pothos, and golden-edged tiger lily under various polarization and geometric conditions. Fluorescence polarization calculated via Stokes parameters revealed distinct responses under varying observation settings. Luo Hua et al. [141] applied multi-angle polarization hyperspectral imaging to jujube canopies, extracting multidimensional features (angle, polarization, and spectrum) and constructing parameters such as NDVI and DOLP to characterize canopy spatial heterogeneity. Their polarization hyperspectral quantitative model provided important technical support for intelligent orchard management.

In postharvest and quality detection applications, polarized hyperspectral imaging has shown strong potential. Faqeerzada, Mohammad Akbar et al. [142] installed polarizing filters on both camera lenses and illumination sources to reduce specular highlights and improve the illumination uniformity. Using PLSR with polarized hyperspectral images, they achieved a determination coefficient of 0.89 for moisture prediction and produced a moisture distribution visualization based on selected wavelengths. The study demonstrated the capability of polarized HSI for the rapid, non-destructive quality evaluation of agricultural products.

Table 7.

Combination of polarization and hyperspectral.

Table 7.

Combination of polarization and hyperspectral.

| Sample | Purpose of Research | Key Technology/Parameter | Experimental Equipment and Methods | Main Data Processing | Main Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farmland soil in northeast China | Relationship between polarization reflection and soil fertility | Polarized reflectance ratio, azimuth, zenith angle, multi-angle polarization spectrum measurement | Field sampling + laboratory multi-angle polarization hyperspectral measurement | Polarization reflection ratio calculation and correlation analysis between polarization parameters and fertility index | Polarized reflectance ratio is negatively correlated with fertility | [137] |

| Smooth leaves (mulberry, camellia, photinia) | Relationship between polarization characteristics and chlorophyll content | DOP (polarization degree), Rmax, Rmin, polarization reflectivity | Multi-angle platform + polarizer + ASD spectrometer + SPAD chlorophyll measurement | The relationship between DOP and chlorophyll was modeled and analyzed, and the nonlinear fitting and accuracy were evaluated | The correlation between DOP and chlorophyll was the highest | [138] |

| Dry plants and bare soil (8 species) | Distinguish between dry plants with similar spectra and bare soil | Spectral-HOG, Spectral-E, and hierarchical clustering | NENULGS platform, ASD FS3 hyperspectral instrument, polarizing mirror | EMD denoising, feature extraction and cluster analysis | The combined features can distinguish between all 8 categories of targets | [85] |

| Spider plant, pothos, tiger lily | The variation law of chlorophyll fluorescence and polarization was analyzed | LIF excitation, F685/F740 ratio, and polarization modeling | Multi-angle fluorescence platform, AvaSpec spectrometer, laser | Regression analysis, polar coordinate drawing, correlation modeling | Fluorescence and polarization are significantly affected by the angle, and the modeling effect is good | [140] |

6.2. Polarization and Multispectral Combination

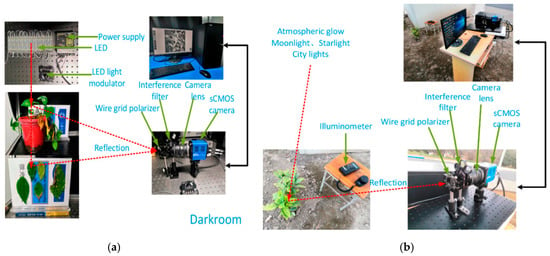

By integrating polarization technology with multispectral remote sensing, the complementary strengths of both have greatly enriched the content of remote sensing data. Hao Jinglei et al. [143] used a three-dimensional reconstruction method based on multi-band polarization to integrate spectral and polarization information, achieving a complete three-dimensional reconstruction of the surface of highly reflective, texture-free targets. This technique aids in obtaining high-precision information about crop surface structures. In 2022, Li Siyuan et al. [144] collected multi-angle polarization images to construct a novel polarization-based vegetation index (NPVI) and compared it with traditional indices such as NDVI and PRI. The results showed that NPVI achieved a correlation coefficient of 0.91 with the chlorophyll content, outperforming NDVI (0.65) and PRI (0.72). Additionally, NPVI significantly reduced the interference from specular reflection, with a coefficient of variation under mirror effects of only 5.62%, much lower than NDVI’s 32.18%. These findings demonstrate that NPVI offers greater stability and accuracy under varying illumination angles, making it suitable for precise vegetation health monitoring (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Polarized multispectral low-light-level imaging system [144].

Shanghai University [84] developed a Polarized Multispectral Low-Light Imaging System (PMSIS), which combines fusion algorithms for nighttime vegetation health monitoring. By calculating the normalized vegetation index (NDVI), linear polarization degree (DoLP), and polarization angle (AOP), they created a new nighttime plant condition detection index (NPSDI). The NPSDI shows significant correlations with the NDVI, SPAD, and nitrogen content, with R2 values of 0.968, 0.882, and 0.916, respectively, effectively distinguishing between different health conditions of vegetation. This method significantly enhances the richness of nighttime vegetation information, providing a new tool for remote sensing monitoring, particularly for assessing the health status of crops and vegetation (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

(a) Indoor polarization multispectral system of low-illumination imaging system. (b) Outdoor polarization multispectral system of low-illumination imaging system [84].

6.3. Polarization and Fluorescence Combination

Polarization–fluorescence-combined detection integrates the advantages of polarized light and fluorescence emission, offering rapid, sensitive, and highly specific analytical capabilities that are particularly valuable in agricultural monitoring. This technology has been widely applied in herbicide residue detection, mycotoxin screening, and agricultural product authenticity testing.

Mukhametova, LI et al. [145] developed a fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA) for the herbicide 2,4-D by synthesizing new tracers and coupling them with monoclonal antibodies. After optimization, the method achieved limits of detection (LODs) of 8 ng/mL for fruit juices and 0.4 ng/mL for water, with a total assay time of only 20 min and recovery rates ranging from 95% to 120%, making it suitable for the rapid monitoring of 2,4-D residues in agricultural commodities. Similarly, Zhou et al. [146] constructed a FPIA based on the IMI-EDF tracer, which shows a significant change in fluorescence polarization upon antibody binding. The assay achieved an LOD of 1.7 μg/L and functioned effectively within the range of 1.7–16.3 μg/L. In agricultural matrices such as paddy water, corn, and cucumber, the recovery rates ranged from 82.4% to 118.5%, with an RSD of 7.0–15.9%, demonstrating both sensitivity and accuracy.

In mycotoxin detection, Lippolis, V et al. [147] established an FPIA for ochratoxin A (OTA) in wheat using a synthetic fluorescent tracer. The method exhibited a strong specificity with an IC50 of 0.48 ng/mL, an LOD of 0.8 μg/kg, a recovery rate of 87%, and an RSD below 6%, requiring less than 20 min per measurement. Its results were highly consistent with HPLC (r = 0.995), indicating suitability for high-throughput OTA screening. Expanding this approach, Zhang et al. [148] reported a dual-wavelength high-throughput FPIA using AFB1 and ZAN labeled with different fluorophores and recognized by broad-spectrum antibodies. The LODs in buffer were 2.68 and 4.08 μg/L, and, in cornmeal samples, 4.98 and 11.03 μg/kg, respectively. The method demonstrated recovery rates of 78.6–103.6%, coefficients of variation below 19.2%, and a detection time under 30 min, with results consistent with HPLC-MS/MS, confirming its efficiency for multi-analyte screening.

Beyond chemical contaminants, polarization fluorescence technology has also been applied to authenticity detection. Li et al. [149] combined fluorescent primer PCR amplification with fluorescence polarization detection by using single-strand binding protein (SSB) to restrict fluorophore rotation and enhance the FP signal. In samples containing chicken DNA, primer incorporation into double-stranded products prevents SSB binding and reduces FP intensity. This strategy merges the specificity of PCR with the sensitivity of FP detection and enables the identification of chicken adulteration as low as 0.035% (wt.%).

7. Other Applications in Agricultural Engineering

7.1. Pesticide Residue Detection

Although pesticides can increase agricultural productivity and harvests, excessive use of them can harm the environment, threaten food safety, and cause ecological harm [42]. These harmful residues can negatively impact consumer health and economic benefits [150]. As a significant chemical pollutant affecting the safety of agricultural products, the on-site efficient detection of pesticide residues has become a global research hotspot and trend [151]. Xin, Z et al. [152] used polarization spectroscopy detection technology, selecting 90 lettuce leaves from five different groups and a total of 450 lettuce samples to collect polarization spectrum information. IRIV, SPA, and CARS were used to determine the ideal wavelengths. A classification model was developed with the help of SVM, KNN, and BP neural networks. With a 100% calibration identification rate and a 97.78% prediction identification rate, the CARS-SVM model was the most effective classification model for the various kinds of pesticide residues found in lettuce leaves. This demonstrates the viability and efficacy of polarization spectroscopy detection technology in identifying various pesticide residues in lettuce leaves. In 2019, Wang Yulong et al. [153] developed a fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA) method using nanoantibodies (Nbs) to detect 3-phenylbenzoic acid (3-PBA), a metabolite of pyrethroid pesticides, which is an important biomarker for assessing pesticide exposure. In practical applications, researchers conducted 3-PBA spiked experiments on urine samples from healthy volunteers, with concentrations of 100 and 400 ng/mL, achieving a recovery rate of 89% and a coefficient of variation of less than 6.7%. In addition, the results of urine samples from people exposed to pesticides were highly consistent with LC-MS, indicating that the Nb-FPIA method was sensitive and stable, and suitable for the rapid screening and biological monitoring of pesticide residues.

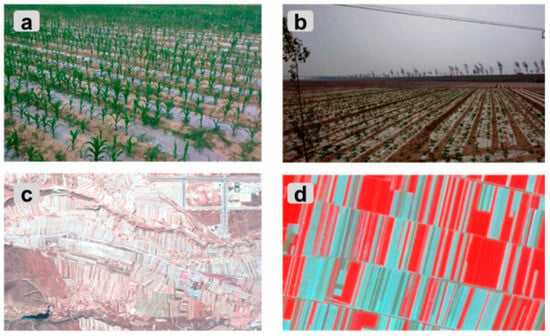

7.2. Application of Polarization Remote Sensing in Agriculture