Abstract

With the advancement of precision agriculture and agriculture 4.0, path tracking control technologies for autonomous agricultural vehicles (AAVs) have become essential for achieving efficient and automated operations. This paper begins by introducing the theoretical framework of AAV path tracking, including its applications across various working scenarios such as dry fields, paddy fields, and orchards, and establishes corresponding vehicle dynamics models suited to these environments. AAVs are classified into wheeled and tracked types based on structural characteristics and specific operational requirements. Subsequently, path tracking control methods are divided into linear and nonlinear approaches according to their system applicability, with detailed discussions on the implementation and adaptations of these strategies in real agricultural settings. Given its strong robustness and extensive adoption, sliding mode control receives particular emphasis in this review. Finally, the paper addresses persistent challenges in complex farmland environments and identifies future research directions aimed at enhancing practicality and adaptability. This review provides a comprehensive and structured analysis of AAV path tracking technologies, with a focus on environmental adaptability and operational feasibility, thereby offering valuable insights for further research and technological development in precision agriculture.

1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of the global population and the increasing scarcity of arable land resources, enhancing the efficiency and precision of agricultural production has become an urgent global challenge. To address these challenges, precision agriculture has become a key approach, utilizing intelligent agricultural equipment to enhance productivity and optimize resource use [1,2]. As the most widely adopted intelligent agricultural equipment, the automation and intelligence development of autonomous agricultural vehicles (AAVs) can provide the expected accuracy, efficiency, and scalability for agricultural operations. Figure 1 illustrates that AAVs are capable of performing autonomous crop rotation, pesticide application, harvesting, and fruit picking without human intervention. The key to effective autonomous operations of AAVs lies in path tracking control technologies, which ensure accurate and reliable path tracking, thereby directly determining the efficiency and quality of farming tasks [3,4]. Consequently, extensive research and considerable efforts have been devoted to improving the performance of path tracking technologies for AAVs.

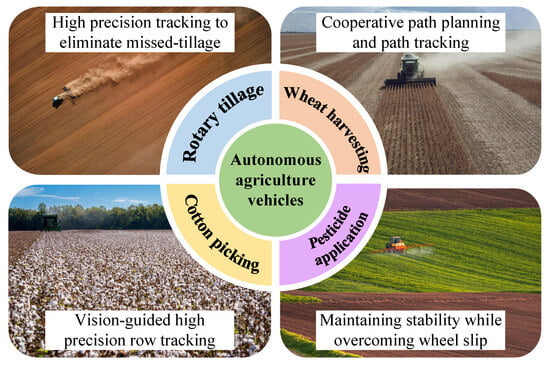

Figure 1.

Path tracking challenges and technological focuses of typical AAVs.

However, operating in a wide variety of environments, such as open fields, structured orchards, dry terrains, and muddy paddies, AAVs face distinctive challenges in each that can significantly impact path tracking accuracy [5,6,7]. For instance, in paddy fields, spatially heterogeneous mud depths result in significant wheel slip. In upland plots, residual ridges and furrows induce structural vibrations and undermine directional stability. Meanwhile, within orchards or structured plantations, narrowly spaced crop rows impose severe constraints on maneuverability [8,9]. These environmental factors have a marked impact on positioning errors and the stability of control systems, suggesting that no single path tracking control technologies is likely to exhibit optimal performance across all operational scenarios [10]. Consequently, there is a pressing need to investigate path tracking control technology specifically adapted to diverse agricultural working conditions, aiming to enhance the robustness and accuracy of AAVs across varied operational contexts.

Notably, AAV path tracking control technologies can be classified into model-free and model-based approaches according to their dependence on system models [11,12,13]. While model-free methods often suffer from limited control accuracy and stability under external disturbances, model-based strategies utilize precise kinematic or dynamic models of AAVs to accurately represent steering and motion, thereby achieving high-performance tracking [14]. Different models are suitable for different operation scenarios, and each model has its own strengths and weaknesses. The kinematic model focuses on the geometric relationships of the vehicle and is suitable for low-speed and relatively flat terrain operational environments, where it can quickly achieve the basic functions of path tracking [15,16]. However, it has poor adaptability to complex dynamic environments. The dynamic model, in contrast, considers complex factors such as inertial characteristics of the vehicle combined with the frictional interaction of tires and surface. It is suitable for complex terrain and high-speed operational scenarios, where it can provide higher tracking accuracy and stability [17]. However, this largely depends on the accuracy of the model parameters, and it is difficult to obtain parameters with sufficient precision in practice. Therefore, it is necessary to select an appropriate model based on the structural characteristics of the AAV and its working environment.

After constructing the vehicle model, the design of the path tracking control strategy becomes a critical factor that exerts a determining influence on the overall path tracking performance. Numerous researchers have conducted thorough investigations into path tracking methods for agriculture vehicles [18,19]. These methods can be categorized as linear or nonlinear control strategies according to the type of system being controlled. This categorization criterion stems from the differences in control design principles: linear control strategies generally prioritize computational efficiency and stability guarantees under specific operating conditions, whereas nonlinear methods account for the inherent coupling and state dependent dynamics characteristic of AAVs. Under the linear control framework, path tracking strategies are typically developed based on linearized vehicle models, which offer considerable advantages in computational efficiency and analytical tractability, where system behavior can be sufficiently approximated as linear. By disregarding higher-order dynamics and nonlinear couplings, linear controllers facilitate straightforward stability analysis and real-time implementation. Several representative linear control methods include PID control, linear quadratic regulator (LQR), neural network control (NNC), and model predictive control (MPC) [20,21,22]. In contrast to linear control strategies, nonlinear control methodologies are intended to manage the complex dynamics inherent in AAVs, which typically involve strong nonlinearities, parameter variations, and external disturbances [23]. By avoiding reliance on linearization approximations, these approaches are capable of maintaining robust path tracking performance across a wider range of operating conditions. Representative nonlinear control techniques include pure pursuit, Stanley control, and fuzzy control [24,25,26]. As agricultural operating environments become increasingly complex, traditional control methods exhibit notable limitations when confronted with nonlinear disturbances, parametric uncertainties and topographic perturbations [27,28]. Sliding mode control (SMC) has received extensive attention in AAV path tracking applications due to its strong invariance to parameter variations and external disturbances, as well as its fast transient response, which can effectively address the above challenges [29]. In challenging field scenarios such as slippery paddy fields or undulating orchards, SMC can effectively mitigate the effects of wheel slip, lateral drift and terrain induced perturbations, thereby substantially improving tracking accuracy and overall system stability [30]. To further enhance control performance, successive research efforts have yielded advanced SMC algorithms including higher order SMC, super twisting sliding mode (STSM) control and composite schemes integrated with disturbance observers, which have made notable advances in chattering attenuation and robustness reinforcement [31,32]. Furthermore, due to its straightforward implementation, low computational overhead, and cost efficiency, SMC has become a key technology in contemporary AAV path tracking control research.

Although path tracking control technologies for AAVs have progressed significantly, numerous unresolved challenges persist. First, the intricate environments and variable working conditions demand higher precision and stability from path tracking control technologies. Second, the accuracy of the AAV model and the presence of multi-source disturbances can influence the performance of control technologies. Additionally, differences in the performance of various computing platforms pose difficulties for the deployment of complex algorithms. Motivated by the foregoing opportunities and challenges, this paper surveys path tracking control technologies across diverse AAVs and operational contexts, focusing on vehicle model construction and the evolution of control methods. Through an in-depth analysis of representative path tracking control technologies, this paper not only provides a comprehensive overview of current applications but also highlights prevailing challenges and future research directions, thereby guiding the sustainable integration of autonomous driving and intelligent agriculture.

From the existing reviews, it can be observed that no systematic review of path tracking control methods for AAV has yet been conducted from the perspectives of discussing different working scenarios for various types of AAV, the establishment of AAV models, classification of control methods, research bottlenecks and enhancement of key performance indicators, and future development directions and trends. The differences between the recent reviews on AAV path tracking technologies and the contributions of this paper are compared in Table 1. Therefore, this review is necessary to deepen the understanding of practitioners regarding the issues in this field.

Table 1.

A comparative analysis of the current and previous review papers.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the application characteristics and challenges in typical scenarios. In addition, the section constructs a theoretical framework for AAV path tracking, offering a detailed examination of the mathematical modeling methods for both kinematic and dynamic models. This includes models for both wheeled and tracked AAV. Section 3 classifies and presents representative path tracking control methods for AAV. Building on this foundation, Section 4 systematically summarizes the key research progress in enhancing path tracking performance. Section 5 discusses the challenges in the field and offers perspectives on future trends. Finally, Section 6 concludes with a synthesis of the state-of-the-art.

To ensure a thorough and structured analysis, the study was conducted in three stages. First, a systematic literature search was performed using authoritative academic databases, primarily Web of Science, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, etc. The search strategy employed core keywords and their synonyms, such as “autonomous agricultural vehicle”, “unmanned agricultural machinery”, “autonomous navigation”, “agricultural mobile robot”, “autonomous tractor”, and “path tracking control”. To capture the latest developments, the search focused mainly on publications from the past five years, while seminal earlier studies were also included to ensure academic rigor. Second, a systematic analysis of the retrieved literature was conducted. By synthesizing the prevailing research focuses and methodologies reported in the publications, we delineated several pivotal dimensions for structuring this review: distinct working scenarios, vehicle modeling, and a comprehensive categorization of control strategies. Particular emphasis was placed on SMC methods, owing to their wide application in recent studies and their demonstrated high-precision path-tracking performance. Third, based on the methods adopted in the most recent state-of-the-art works and by summarizing the insights in the literature, we infer the forward-looking research directions that may shape the future trends of this field.

2. Theoretical Framework and Application of AAV Path Tracking

2.1. Research in Different Application Scenarios

Different agricultural environments present distinct operational requirements and employ varied types of AAV, yet path tracking serves as the fundamental basis for accomplishing complex tasks. This section explores the application and refinement of path tracking methods for AAVs under diverse agricultural conditions that present unique challenges.

2.1.1. Dry Field AAV

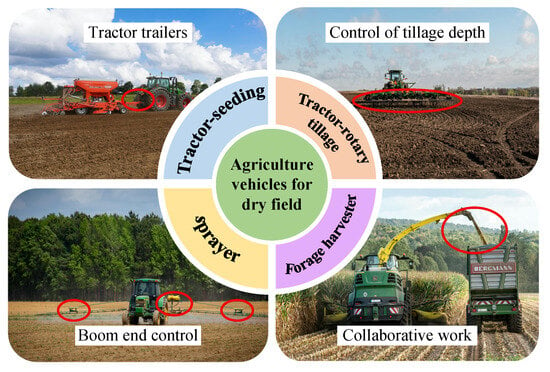

The application of AAV in dry fields encompasses all aspects of agriculture, including plowing, sowing and harvesting [41,42,43,44]. Representative types of AAVs for dry fields are shown in Figure 2. Path tracking systems for dry field agricultural operations have primarily concentrated on maintaining path accuracy across large scale open areas with relatively stable terrain conditions. The research in this domain has emphasized the development of robust control algorithms capable of compensating for gradual terrain variations while ensuring consistent tracking performance during extended operational periods. Significant attention has been given to the trade-offs between tracking precision and operational efficiency [45,46].

Figure 2.

Representative types of AAVs for dry fields.

For instance, Fue et al. [47] developed an improved pure pursuit navigation system for cotton harvesting robots. By innovatively introducing a path error compensation coefficient and dynamic look-ahead distance adjustment, the system successfully resolved control challenges during AAV steering. Field tests demonstrated a straight-line tracking error of 0.04–0.09 m, meeting the operational requirements for cotton harvesting. Moreover, Cui et al. [48] introduced an AAV guidance framework integrating dynamic route planning with a fuzzy Stanley controller, with the corresponding field prototype depicted in Figure 3. The system innovatively employed fuzzy logic to dynamically adjust Stanley model parameters, reducing straight-line tracking error to 10 cm and limiting the maximum operational error to 27 cm. Additionally, Wang et al. [49] addressed path tracking accuracy in autonomous boom sprayers by proposing a pure pursuit algorithm with adaptive preview distance. Through kinematic modeling of the sprayer and an innovative weighted evaluation function incorporating lateral and heading offset, dynamic optimization of the preview distance was realized. Simulation and field tests showed an average lateral offset reduction to 0.072 m in U-shaped path tracking, with maximum turning offset reduced to 0.417 m.

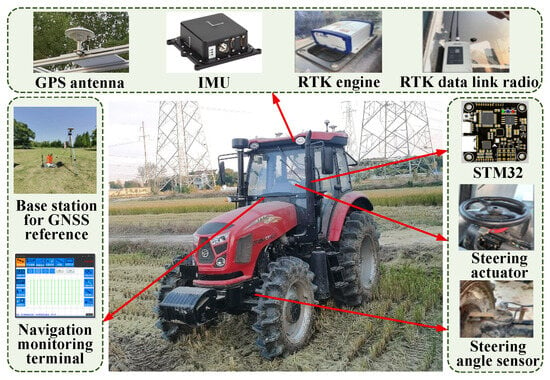

Figure 3.

The main composition of the autonomous navigation system for wheeled tractor.

2.1.2. Paddy Field AAV

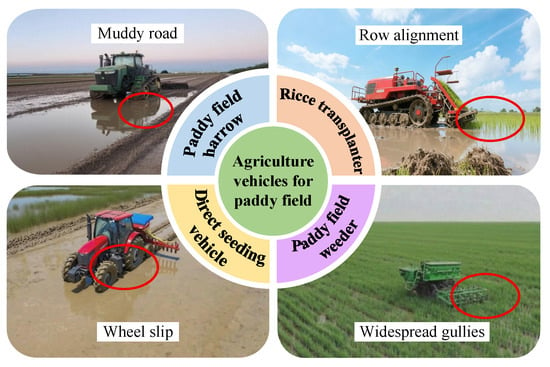

Path tracking systems operating in paddy fields encounter unique challenges arising from the highly dynamic coupling between vehicle platforms and saturated, water-inundated terrain [38,50]. In paddy field operations, AAV like seeders and transplanters are prone to lateral slip and rollover, which considerably raises the control complexity of autonomous navigation systems [51,52,53]. Representative types of AAVs for paddy fields are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Representative types of AAVs for paddy fields.

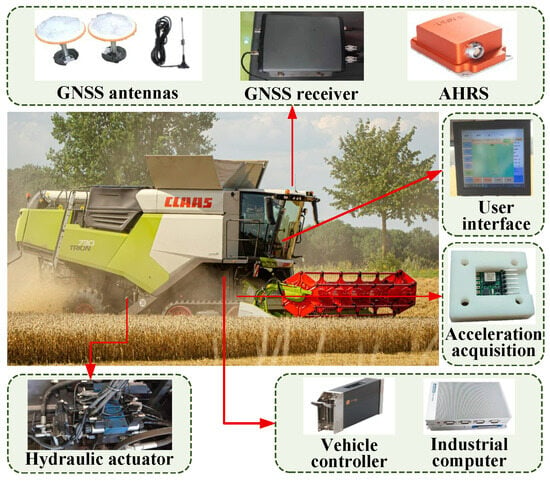

To improve navigation accuracy in the challenging conditions, Han et al. [54] developed a dynamic model-based tractor navigation system adapted to small-scale paddy fields with slippery soils. Field tests achieved centimeter-level accuracy along straight paths in low-moisture paddies, yet exhibited pronounced errors on muddy curved segments under high moisture. Expanding on this work, He et al. [55] innovatively classified three paddy soil states via vibration signals and integrated the results into a steering control model to mitigate track slip. This approach maintained lateral deviation within 5.3 cm across diverse muddy environments, substantially surpassing conventional methods. Furthermore, Figure 5 shows the experimental setup, which consists of an autonomous navigation system for a tracked combine harvester and its key components. Additionally, Wang et al. [56] developed a modified stanley controller by introducing a heading offset integral term and dynamically optimizing its five parameters using a multi-population genetic algorithm. However, it inadequately addressed complex paddy field environments. Consequently, Li et al. [57] presented an adaptive SMC approach combined with radial basis function (RBF) neural networks for unmanned rice transplanter path tracking. They employed a power-reaching law to suppress chattering while utilizing the RBF network to approximate real-time field disturbances. To further improve the path tracking precision and stability of rice transplanters, Zhu et al. [58] put forward a path tracking control method based on variable universe fuzzy control (VUFC) and an improved beetle antennae search algorithm. The study adaptively adjusts the fuzzy universe via VUFC to accommodate real-time error variations, thereby alleviating the burden of real-time computational load. Simulation and field experiments confirmed that, compared to pure pursuit control, this method significantly reduces settling time and overshoot upon reaching steady state.

Figure 5.

The main composition of the autonomous navigation system for tracked harvester.

2.1.3. Orchard AAV

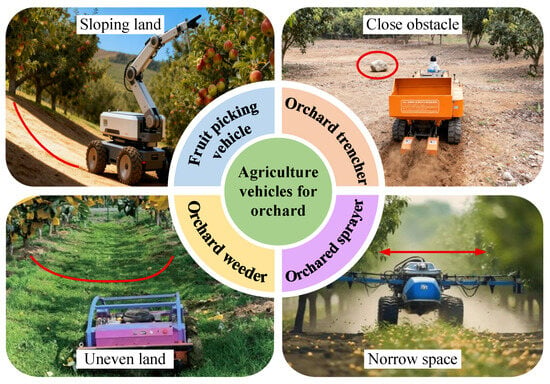

The unique layout of the orchard poses a significant challenge to the path tracking system. Representative types of AAVs for orchards are shown in Figure 6. Orchard AAVs often need to travel in narrow alleys between fruit tree rows, which imposes stringent demands on the accuracy and adaptability of path tracking [59,60,61]. The uneven terrain further increases the complexity of the navigation process, substantially increasing the difficulty of achieving precise and stable autonomous path tracking in such an environment [62]. In this regard, scholars have conducted extensive research and achieved satisfactory results [63,64,65].

Figure 6.

Representative types of AAVs for orchards.

A series of studies have been devoted to improving path tracking accuracy and adaptability in orchards. Thanpattranon et al. [66] addressed the steering accuracy challenge for automated transport in narrow orchard and plantation rows by proposing a single sensor LiDAR-based landmark navigation method, enabling automatic docking for loading or unloading operations through specific landmark pattern recognition. However, adaptability to canopy occlusion scenarios proved limited, and response delays in steering hitch coordination require optimization. Furthermore, Xue et al. [67] employed a linear time-varying MPC approach to design a path tracking controller for orchard tractors. By establishing nonlinear dynamic models followed by discretization and linearization, this method resolved path tracking inaccuracies during straight-line and curved orchard operations. To overcome the aforementioned limitations, Ren et al. [68] developed a double deep Q network-based path tracking method, targeting precise navigation of spray trailers in narrow traditional orchard paths. This solution offers advantages of mathematical model independence and scalability. However, performance gaps between simulation and field deployment were observed, and control latency caused by dynamic factors like hitch angle differences was unaddressed. Consequently, Qu et al. [69] proposed a steering compensation integrated MPC strategy to rectify path deviation caused by lateral gravitational forces during slope traversal. A steering compensator was designed through mechanical analysis and PID coefficient tuning, achieving precise control on slope terrain.

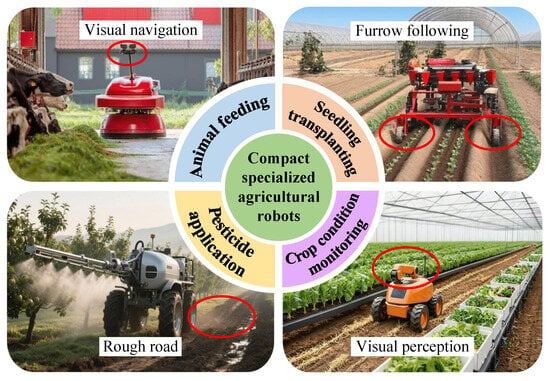

2.1.4. Compact Specialized Agricultural Robots

For special agricultural tasks, the unmanned and intelligent autonomous compact specialized agricultural robots have emerged as a significant trend in agricultural modernization [70,71]. Representative types of agricultural robots are shown in Figure 7. These robots, fitted with advanced sensors and precise control systems, are capable of executing a variety of tasks with high efficiency and accuracy [72,73,74]. However, achieving high-precision path tracking remains a challenge in complex agricultural environments.

Figure 7.

Representative types of compact specialized agricultural robots.

To enhance the accuracy and adaptability of autonomous path tracking for mobile robots operating between crop rows in unstructured agricultural fields, Urrea et al. [75] evaluated a model reference adaptive control strategy. They observed that model reference adaptive control exhibited optimal performance in terms of comprehensive error metrics and torque smoothness, effectively reducing the load fluctuations of the actuation mechanisms. Additionally, Gu et al. [76] addressed path tracking challenges in corn fields during the later growth phases by developing a visual navigation system for a tracked data collection robot. This robot demonstrated high stability in path tracking, with the convolutional neural network model demonstrating strong robustness in low light and occluded scenarios. However, significant path deviations occurred on clay soil due to wheel slippage. To reduce lateral deviations in path tracking, Liu et al. [77] designed an ultrasonic detection-based ridge tracking system for transplanting machines in ridge-cultivated crops such as strawberries and tomatoes. This system improved the accuracy of autonomous path tracking in narrow ridge environments. However, it only supported tracking within the current ridge, and cross-ridge operations still required manual intervention. As a result, Yan et al. [78] devised a path tracking method integrating dynamic pure pursuit with online particle swarm optimization PID for agricultural robots operating in unstructured fields, addressing the nonlinear disturbances faced by these vehicles. Furthermore, Azimi et al. [79] enhanced the robustness of path tracking for Ackermann-steered agricultural robots in orchard and vineyard ridge operations under wheel slippage disturbances.

2.2. Summary of Path Tracking Strategies in Different Scenarios

Table 2 presents a systematic overview of path tracking strategies for AAVs across representative operational scenarios. As shown, this section conducted a comparative analysis of four main environments, namely dry land, paddy fields, orchards, and compact specialized agricultural robots, considering aspects such as scenarios, platforms, control methods, and practical difficulties.

Table 2.

Summary of AAV path tracking strategies in differernt working scenarios.

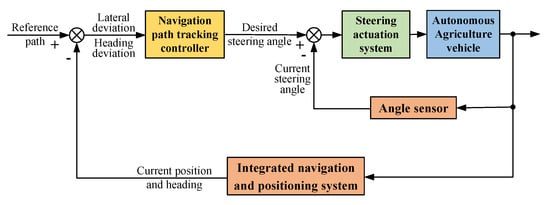

2.3. Construction of the Mathematical Model

Current path tracking strategies for AAVs are generally divided into model-free and model-based paradigms, whose specific techniques are elaborated below. Extensive research has established that an accurate vehicle model is essential for the synthesis of effective path tracking controllers. This section will first introduce two types of AAV models, followed by an exploration of kinematic and dynamic models in diverse operational scenarios and their applicability across various AAVs. The AAV path tracking control technologies achieves precise tracking of predetermined working paths by acquiring real-time vehicle motion state parameters, integrating AAV models, and employing advanced control methods. The corresponding schematic diagram of its tracking principle is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of path tracking principle for AAVs.

2.3.1. Kinematic Model

Path tracking approaches utilizing kinematic models achieve path tracking by establishing geometric relationships between vehicle pose and steering control inputs. This approach takes lateral offset and heading offset as inputs and calculates the front wheel steering angle, with its foundation lying in constructing the vehicle kinematic equations to transform the path tracking problem into solving for desired steering angles [80,81]. Current research has demonstrated that kinematic model-based controllers deliver high tracking accuracy at low speeds.

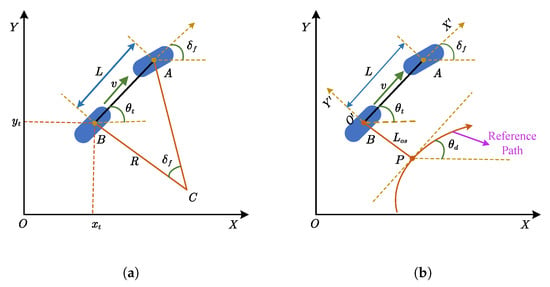

When AAV operates at a low speed, the influence of complex factors such as lateral tire slip between the tires and the ground and ground conditions can be neglected [82]. At present, the prevailing literature routinely reduces a broad range of four-wheeled agricultural platforms, such as tractors, combine harvesters, and rice transplanters, to an equivalent bicycle model, driven by its parsimonious kinematic representation and the experimental accessibility of its geometric and inertial parameters. Illustrated in Figure 9, the widely adopted kinematic model and path tracking offset model for the automatic navigation of AAVs without considering the influence of sideslip are presented. Then the kinematic model of the wheeled AAV without the influence of sideslip can be expressed as follows:

where represents the steering angle, denotes the actual heading angle, L denotes the length of the vehicle, v represents the longitudinal forward speed, m/s, and represents the vehicle coordinate information.

Figure 9.

Models of four-wheeled AAV without the influence of sideslip. (a) Kinematic model. (b) Path tracking offset model.

Additionally, represents the angular rate of the desired heading and can be described as:

where denotes the curvature of the reference path. Owing to and in conjunction with the kinematic model, the dynamics of the heading offset are obtained as follows:

Consequently, the path tracking offset model for AAV without the influence of sideslip is derived as follows:

In actual agricultural environments, spatially variable soil softness and uneven mud depths in paddy fields frequently induce longitudinal slip and lateral drift of AAVs during autonomous works, thereby compromising navigation accuracy and work quality. Addressing this issue, Huynh et al. [83] augments the classical kinematic model by incorporating longitudinal slip speed, lateral slip speed, and slip angle, establishing a kinematic and offset model that directly incorporates slip effects. The corresponding schematic is presented in Figure 10. By fully accounting for lateral slip, a more accurate kinematic model for AAV can be formulated as follows:

where and , respectively denote the lateral and longitudinal sideslip velocities at the center point of the rear wheel B; and denote the actual speed and the sideslip speed of the front wheels, respectively; denotes the front wheel slip angle. It should be noted that the definitions of other parameters in Figure 10 are consistent with those in Figure 9. The introduction of these parameters can more comprehensively characterize the movement state of AAV under the influence of sideslip.

Figure 10.

Models of four-wheeled AAV with the influence of sideslip. (a) Kinematic model. (b) Path tracking offset model.

Since represents the angular rate of the desired heading, it is expressed as follows:

Given that , the dynamic equation of the heading offset is expressed as follows:

The path tracking offset model for AAV with the effect of sideslip is constructed as follows:

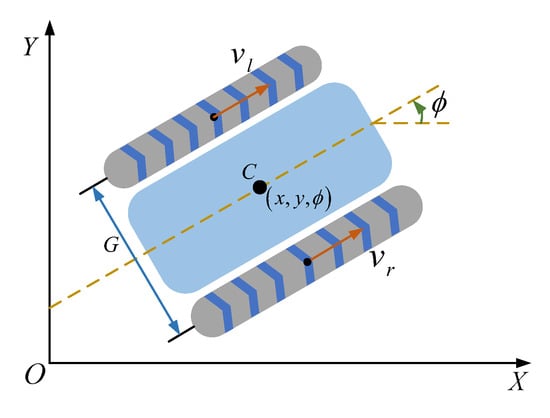

For tracked AAVs, the kinematic model is governed by a differential drive principle, where motion is determined by the left and right track speeds. At low speeds, lateral slippage between tracks and the ground, as well as terrain effects, can be disregarded. Referring to the schematic in Figure 11, C represents the vehicle’s center of mass, represents the yaw angle, denotes its coordinates, G is the track gauge, and the tangential velocities of the left and right tracks are given by and , respectively. Consequently, the kinematic model is formulated as follows:

Figure 11.

Kinematic model of agricultural tracked vehicle.

2.3.2. Dynamic Model

The dynamic model can describe the state evolution during motion and better reveals the internal dynamic coupling characteristics of the system. In real-world agricultural operations, when encountering complex conditions such as high-speed driving scenarios, significant variations in reference path curvature, and large curvature steering requirements, the navigation path tracking control method based on the dynamic model demonstrates enhanced overall performance compared to controllers relying on kinematic models. This advantage arises from the dynamic model’s accurate representation of inertial effects, tire-ground interaction forces, and actuation system dynamic responses. By effectively compensating for nonlinear time-varying behavior under high-speed conditions, the dynamic model considerably improves path tracking precision and system stability. For AAV, path tracking control requires rapid yet stable convergence to the reference trajectory provided by the navigation system. This necessitates a focus on lateral and yaw motions and, therefore, the development of a lateral dynamic model [84].

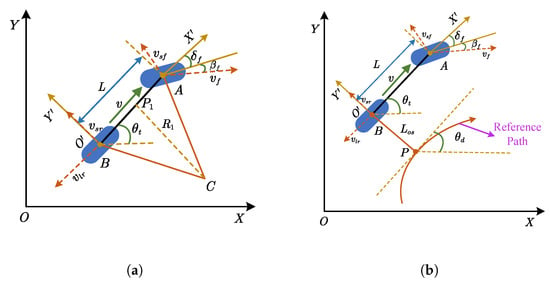

The dynamic model of the wheeled AAV is illustrated in Figure 12. The variables and represent the longitudinal and lateral speeds of the AAV, respectively. The parameter denotes the sideslip angle measured at the vehicle center of mass; it represents the angular deviation between the AAV heading direction and the actual velocity vector. It can be expressed as . The front wheel steering angle is denoted by , while represents the yaw rate. The distances from the center of mass to the front and rear axles are and , respectively. The tire slip angles for the front and rear wheels are and , and the corresponding lateral tire forces acting on the front and rear axles are and . The body-fixed coordinate system is associated with the AAV, with its origin o located at the center of mass. The global inertial coordinate system is denoted as , fixed to the ground.

Figure 12.

Models of four-wheeled agriculture vehicle. (a) Two-degree-of-freedom plane motion model. (b) Path tracking offset model.

Applying Newton’s second law yields the two-degree-of-freedom lateral dynamic equations:

where m denotes the total mass of the AAV, and represents its yaw moment of inertia.

According to [17], the path tracking offset model for AAVs expressed in the Serret–Frenet frame takes the following form:

where denotes the velocity at the projection point T of the AAV on the reference path, while and represent uncertainties resulting from unknown modeling errors and external disturbances.

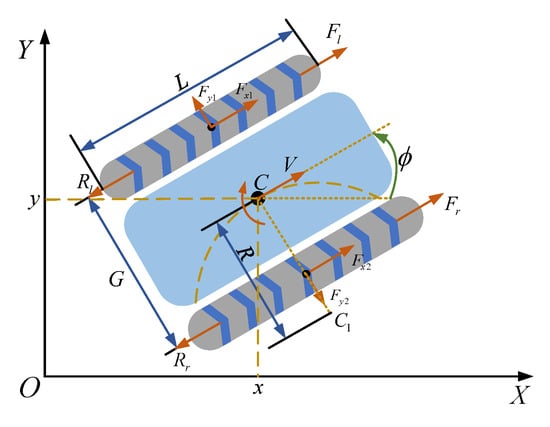

During the development of path tracking methods for tracked AAVs, Li et al. [85] employed dynamics simulation tools to establish a detailed model representing the interactive dynamics between the tracked vehicle and the terrain. Figure 13 illustrates the dynamic representation of the tracked vehicle. Within this schematic, denotes the instantaneous rotation center, C represents the geometric centroid, G and R represent the vehicle width and turning radius, respectively.

Figure 13.

Dynamic model of agricultural tracked vehicle.

2.4. Summary of Agriculture Vehicle Models

As introduced previously and summarized in Table 3, for AAV path tracking, the kinematic model offers simplicity and computational efficiency but neglects dynamic factors such as tire slip, making it appropriate for flat fields at low speeds. Conversely, the dynamics model can more realistically capture terrain mechanics effects, including slip and load transfer, thereby enhancing control accuracy in rugged terrain. However, it suffers from computational complexity, demands precise parameters, and exhibits poor real-time performance. Overall, the kinematic model allows for ease of implementation at the expense of accuracy, while the dynamics model achieves higher precision at a significantly increased engineering cost.

Table 3.

Comparative analysis of vehicle models for AAV path tracking control.

3. Classification of Methods for AAV Path Tracking

This section classifies path tracking control methods based on the category of system model for which they are designed, namely linear and nonlinear systems. Subsequent discussions will examine the principles, applications, and limitations of representative approaches within each category.

3.1. Linear Control

Under the linear control framework, path tracking methods are typically developed based on linearized vehicle models, which offer significant benefits in computational efficiency and analytical tractability, where system behavior can be sufficiently approximated as linear. By ignoring higher-order dynamics and nonlinear couplings, linear controllers facilitate straightforward stability analysis and real-time implementation. This section introduces several representative linear control methods, including PID control, LQR, and MPC.

3.1.1. PID Control

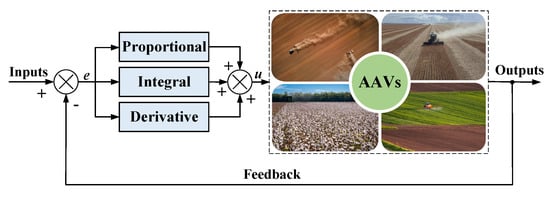

PID control represents a widely adopted closed-loop control algorithm that has occupied a pivotal position in industrial automation and control systems, primarily due to its merits of straightforward implementation, satisfactory stability characteristics, and robust performance [86,87]. The fundamental principle of PID control is to regulate the system based on the error between the desired and actual values, utilizing proportional, integral, and derivative components [88,89]. As depicted in Figure 14, the PID controller generates steering commands by exploiting the discrepancy between the reference path and the instantaneous vehicle state. Then, its calculation formula is as follows:

where denotes the proportional gain coefficient, represents the integral gain coefficient, stands for the derivative gain coefficient, and e corresponds to the tracking offset. According to the kinematic model (1) of wheeled AAVs, the path tracking offset is defined as , where denotes the lateral deviation gain, represents the heading offset gain.

Figure 14.

Block diagram of PID control.

In AAV path tracking control, PID control primarily adjusts the steering angle and speed to ensure precise path tracking. By appropriately tuning the proportional, integral, and derivative parameters of the PID controller, path deviations can be effectively reduced, and the accuracy and stability of path tracking can be improved [90]. Consequently, Cheng et al. [91] introduced an integrated, model-free adaptive predictive–PID control architecture to boost both tracking precision and robustness for tractors navigating intricate agricultural settings. This method avoids the requirement for precise mathematical models and demonstrates strong robustness under low-adhesion terrain and noise interference. Moreover, Qun et al. [92] presented an intelligent guidance scheme for greenhouse robotic platforms that employs a fuzzy PID path tracking strategy. Additionally, Zhang et al. [93] introduced a path tracking framework adapted to large combine harvesters with rear wheel steering. This framework combines feedforward PID control with a preview-based Ackermann steering model to accommodate their distinctive steering behavior. The approach establishes a viable technological route for fully automated, high-precision harvesting in large-scale AAV.

3.1.2. LQR

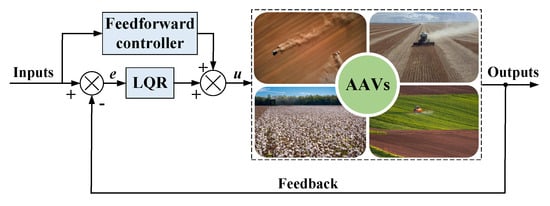

Depicted in Figure 15, the LQR represents a widely adopted optimal linear control strategy for AAVs. The LQR is aimed at finding the optimal control law, which facilitates the smooth transition of the closed loop system from the initial state to the desired state while ensuring the optimality of the quadratic performance index [94]. LQR ensures fast convergence while maintaining design simplicity.

Figure 15.

Block diagram of LQR.

The quadratic cost functional is expressed as

where is chosen symmetric positive semi-definite and symmetric positive definite, thereby weighting state penalties and control effort, respectively.

Within this control strategy, the optimal solution implies solving a quadratic equation to obtain the optimal extremum under the constraints of the AAV state. Moreover, it should be pointed out that although the LQR method is relatively simple in design, its path tracking performance may be compromised when the AAV tracks reference paths with time-varying curvature [95]. Therefore, to achieve the path tracking control objective of AAV, this method is often combined with other control strategies. For example, Meng et al. [96] presented an LQR-GA controller for AAV path tracking in which a genetic algorithm optimizes the LQR weight matrices to accurately regulate the linear and angular speeds at the front axle midpoint of the tractor. Additionally, Xu et al. [97] proposed a path tracking method based on optimal preview control, which integrates the preview approach into the LQR. Research has demonstrated that this method performs excellently in terms of tracking accuracy and steering smoothness.

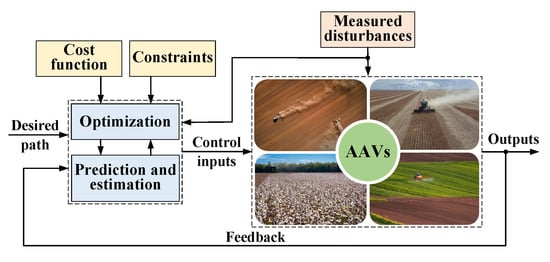

3.1.3. Model Predictive Control

MPC is an advanced methodology that employs a system forecast to compute optimal control inputs across a finite future horizon. Figure 16 illustrates that MPC forecasts forthcoming system dynamics via a predictive model and optimizes control actions across a finite future horizon. At each time step, MPC repeatedly solves an optimization problem while accounting for constraints on system states and control inputs [98]. In the field of AAV path tracking, MPC has been widely applied to improve tracking accuracy and robustness [99].

Figure 16.

Block diagram of MPC control.

The core of the MPC algorithm involves solving the following constrained optimization problem at each time step k:

where Q is positive semi-definite, while R and P are positive definite weighting matrices, denotes the terminal invariant set, and N represents the prediction horizon.

To enhance the robustness of the MPC, Plessen et al. [100] proposed a linear time-varying MPC control method that simultaneously accounts for steering and actuator output constraints. Field tests demonstrated that this approach improves path tracking accuracy and stability. Kayacan et al. [101], taking into account the sideslip effects in AAV navigation, developed a distributed nonlinear MPC path tracking control method. This approach employs a nonlinear moving horizon estimation strategy to observe state parameters in real-time. Furthermore, Backman et al. [102] proposed an agricultural vehicle navigation system based on nonlinear MPC, integrating GPS, laser scanners, and inertial measurement units to achieve high-precision path tracking for tractor trailer systems. However, the system shows high computational complexity and high reliance on sensor accuracy. To address the aforementioned challenges, Wang et al. [103] propose a parameter adaptive MPC framework that synergizes fuzzy logic with particle swarm optimization. Even when subjected to speed disturbances, the proposed strategy limits lateral deviation to 2.44 cm, substantially improving robustness and tracking precision within confined field corridors.

3.2. Nonlinear Control

In contrast to linear control methods, nonlinear control methodologies are designed to handle the complex dynamics inherent in AAVs, which typically involve strong nonlinearities, parameter variations, and external disturbances. By eliminating the need for linearization approximations, these approaches are capable of maintaining robust path tracking performance across a broader range of operating conditions. This section introduces several representative nonlinear control techniques, examining their principles and applicability within agricultural contexts.

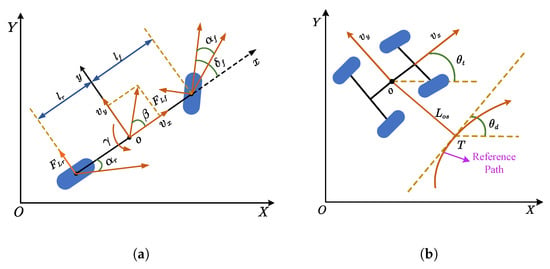

3.2.1. Pure Pursuit

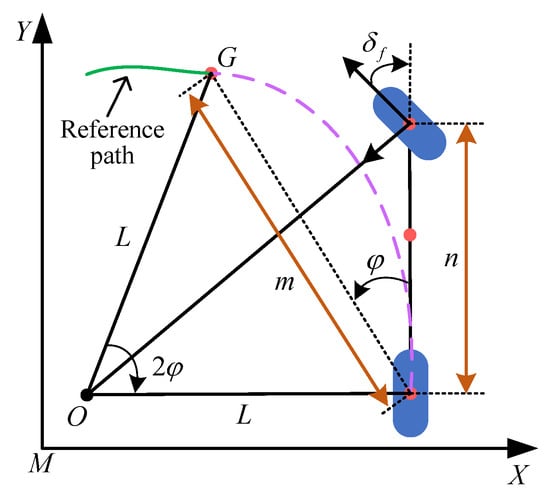

Pure pursuit tracking control has long been used for the lateral control of self-driving vehicles [104]. It takes the center of the rear axle of the AAV as the reference point. After a suitable look-ahead distance is set, the algorithm identifies an appropriate target point along the forward direction of the vehicle [33,105]. As depicted in Figure 17, the pure pursuit method relies on a geometric framework that converts the lateral deviation between the vehicle’s instantaneous position and a target look-ahead point on the reference path into an appropriate steering command. A proportional controller then produces the steering angle required for path tracking.

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of pure pursuit algorithm.

To guarantee tracking of the dashed arc to the reference path target point G located at look ahead distance m by the vehicle rear axle, the corresponding geometric constraint must be satisfied Upon simplification, one obtains Based on the Ackermann steering principle, the required front wheel steering angle can be geometrically determined to achieve a target turning radius L through the following formulation:

where represents the angle between the agriculture vehicle body and the preview point, denotes the target steering angle of the front wheels, and n indicates the wheelbase of the AAV.

By utilizing real-time lateral and heading deviation information, it calculates the feedback control law for the front wheel steering angle, thereby ensuring that the AAV follows the planned reference path along the circular arc trajectory between the reference point and the target point. In fact, due to its benefits of straightforward design, fewer adjustment parameters, and ease of implementation, pure tracking control has been widely used in low-speed unmanned agricultural operations [106]. Additionally, Yang et al. [107] modified the traditional pure pursuit algorithm to meet the navigation requirements of rice transplanters in both straight and curved sections of the field. However, the effectiveness of this method in complex terrains and across a wide range of speeds was not thoroughly evaluated. Moreover, Ge et al. [108] introduced an enhanced pure pursuit algorithm that incorporates fuzzy reasoning to adaptively modulate the preview horizon and speed. This strategy markedly improves path tracking precision for AAVs traversing variable curvature paths.

3.2.2. Stanley Control

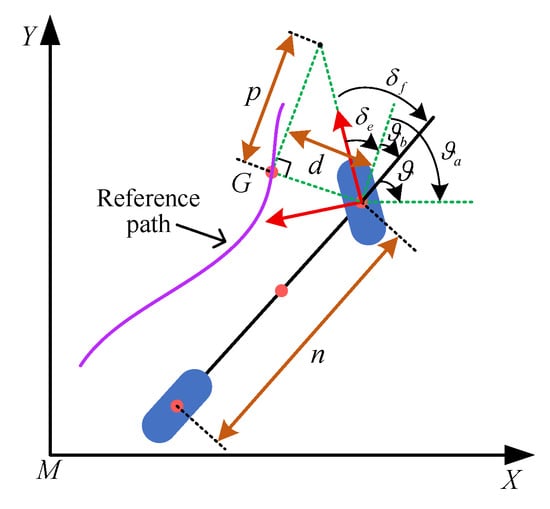

Stanley control is a path tracking control method grounded in the integration of feed-forward and feedback. Its essence is to fuse lateral offset and heading offset into a single command that steers the vehicle [109]. Owing to its compact structure and computational performance, the Stanley controller has become a benchmark in autonomous driving, demonstrating robust performance on intricate routes and under variable conditions [110]. Figure 18 illustrates the principle of the Stanley control algorithm, which is also grounded in geometric considerations.

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of Stanley control algorithm.

The geometric relationship can then be derived as , where represents the heading offset between the vehicle body and the target point, and denotes the angle between the velocity direction of the front wheels and the tangential direction of the target point. From the geometric relationship, it can be observed that satisfies , where p is the look-ahead distance and is positively correlated with the vehicle speed v, with g being the positive coefficient, and it satisfies Therefore, the final expression for the front wheel steering angle control law can be formulated as follows:

Within agricultural robotics, the same approach is widely used to improve tracking precision and stability across challenging field topographies [111]. Moreover, Snider [112] verified through simulation that under high-speed driving conditions, the Stanley method is more effective than the pure tracking algorithm, but this method has higher requirements for the smoothness of the reference path. As s result, Sun et al. [113] designed a fuzzy Stanley model based on particle swarm optimization enhancement for full-field path tracking of AAV. Experiments demonstrate that it notably decreases lateral offset in moving vehicles and combine harvesters.

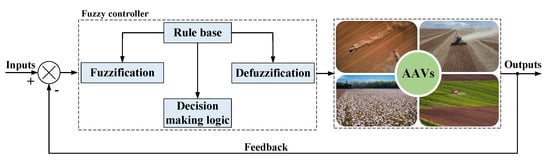

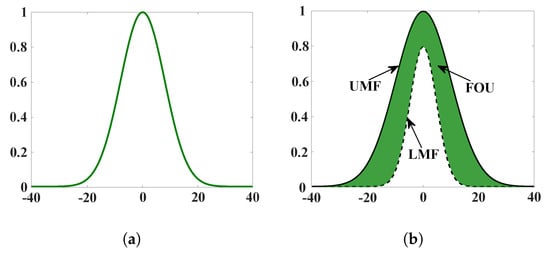

3.2.3. Fuzzy Control

Fuzzy control constitutes an intelligent strategy founded on fuzzy set theory, aimed at emulating the experiential decision-making processes of human experts in handling system uncertainties and ambiguities [114,115]. The fuzzy control block diagram based on the MAMDani model is shown in Figure 19. Its core principle lies in utilizing fuzzy rules and inference mechanisms to transform complex nonlinear relationships and imprecisely quantifiable information into actionable control strategies [116,117,118]. Due to its minimal reliance on system models, high adaptability, and ability to handle complex nonlinear systems, fuzzy control has been widely employed across various domains [119,120,121,122,123,124]. Figure 20 provides a schematic illustration of them.

Figure 19.

Block diagram of fuzzy control.

Figure 20.

(a) MF illustration of an type-1 fuzzy set. (b) MF illustration of an type-2 fuzzy set.

Due to its strong robustness to field uncertainties, fuzzy control has become an important method for path tracking control of AAV. For instance, Zhang et al. [125] devised a path tracking algorithm in which a pure pursuit model adjusted by fuzzy logic satisfies the autonomous navigation requirements of four-wheel steering AAVs. Field validation showed a maximum lateral deviation of only 5.8 cm on straight paths and a steady-state offset of 3.9 cm. In [126], a novel agricultural robot navigation controller was developed through the combination of, machine vision and fuzzy control frameworks, with field tests confirming its operational efficacy. Furthermore, Liu et al. [127] presented fuzzy SMC (FSMC) to simultaneously handle path tracking for tracked AAVs. However, the inherent chattering phenomenon in SMC limits its broader application. In response, Huang et al. [128] devised a straight-line tracking strategy for tractor–trailer combinations that couples fuzzy logic with SMC. A power-reaching sliding surface was used to reduce the chatter inherent in conventional SMC, while adaptive fuzzy rules were implemented for online parameter tuning, yielding faster convergence and improved disturbance rejection.

3.2.4. NNC

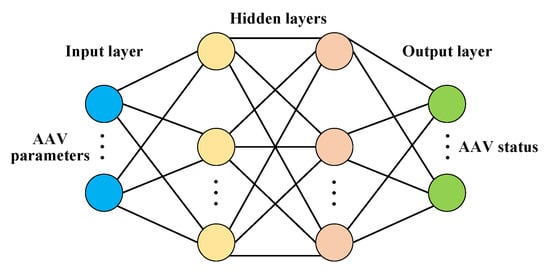

NNC is an advanced intelligent control strategy, the foundation of which lies in employing the self-learning and adaptive capabilities of artificial neural networks to achieve effective control of complex systems [129,130,131]. The principal strengths of NNC are its minimal reliance on system models, its ability to handle system uncertainties and dynamic changes, and its strong robustness and adaptability [132]. In the field of AAV path tracking, NNC has been widely applied to enhance the accuracy and stability of path tracking. Specifically, a neural network controller can receive real-time data from sensors, such as the position, velocity, orientation of the AAV, and the deviation from the desired path. These data are used as inputs to the trained neural network, which processes them to produce corresponding control commands, such as steering angle and speed adjustments [133,134].

As illustrated in Figure 21, neural networks possess the capability to accurately approximate nonlinear functions. This method leverages neural networks to learn the mathematical model of the system, thereby achieving effective control of AAV. For instance, Zhang et al. [135] introduced a path tracking controller for autonomous combine harvesters that employs an adaptive neural network. Simulation and experimental results indicate a reduction in tracking offset exceeding 28% relative to conventional approaches. However, input delay was not taken into account, and the control complexity was notably high. Furthermore, Liu et al. [136] further advanced path tracking for a miniature crawler tractor by employing a virtual radar framework and a deep neural network controller. Their work demonstrates that in complex working environments such as orchards, this method has higher tracking accuracy and driving stability.

Figure 21.

Schematic diagram of neural network.

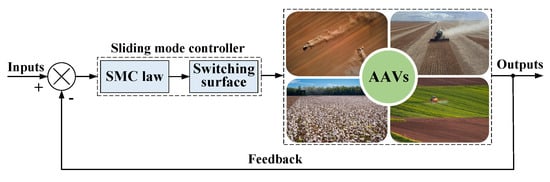

3.2.5. SMC

In recent years, with continuous technological advancements, SMC has been widely applied in the field of AAV automatic navigation control [137]. SMC is a widely adopted nonlinear robust technique noted for its rapid response, tolerance to matched disturbances and parameter variations, absence of online identification requirements, and ease of physical implementation [138,139]. Figure 22 shows a basic SMC configuration. In this control technique, the system states are driven to and maintained on the predefined sliding surface via a suitably designed control law. Particularly in the field of automatic navigation and tracking control for AAV, SMC has demonstrated significant application potential and practical value due to these unique advantages [140,141]. A detailed and systematic introduction to the application of various sliding mode algorithms in AAV path tracking will be presented subsequently.

Figure 22.

Block diagram of SMC.

- (1)

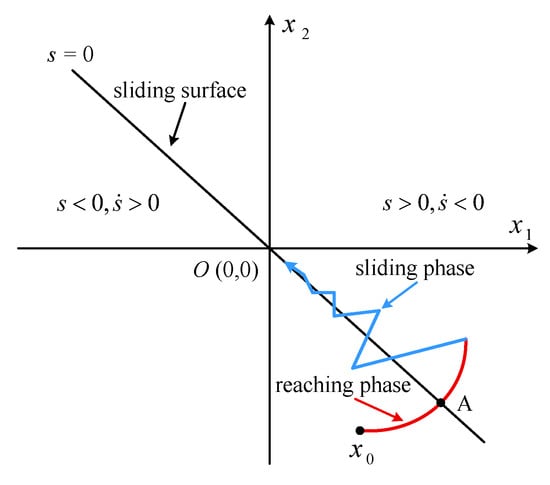

- Conventional first-order SMC

In conventional SMC, the primary and crucial design step is to construct a suitable sliding mold surface. The sliding surface s is designed based on SMC theory, with its specific expression given as , where denotes the weighting coefficient to be designed.

The fundamental concept of SMC lies in designing an appropriate sliding surface and a controller incorporating a switching function, such that the system states can be driven to converge onto the predefined sliding surface and subsequently perform sliding motion along it until reaching the equilibrium point. A schematic diagram showing the state trajectory of SMC is given in Figure 23.

Figure 23.

Schematic diagram of SMC.

By taking the first-order time derivative of the sliding variable, the first-order sliding mode dynamics can be designed as follows:

where , and . Furthermore, the unknown lumped disturbance is bounded, meaning that there exists a positive constant D such that for any , the inequality holds.

Based on this, the conventional first-order sliding mode path tracking controller is designed as follows:

where , and represent the control parameters to be designed.

- (2)

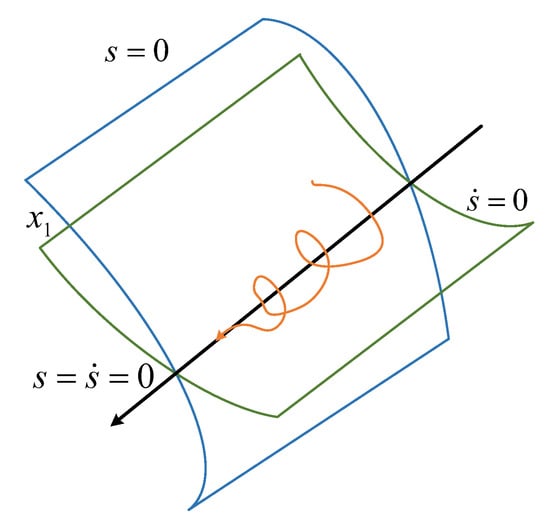

- Second-order SMC

To overcome the inherent chattering problem of the first-order SMC, researchers subsequently introduced the second-order SMC, which significantly reduces the chattering phenomenon while maintaining the robustness of the controller [142,143]. The second-order sliding mode evolution is illustrated in Figure 24, which vividly depicts the dynamic motion process under second-order SMC. The blue and green curves delineate distinct state boundaries, while a prominent black line indicates the sliding surface where . The orange trajectory, representing the system’s state evolution, exhibits a spiral convergence behavior toward the sliding surface. This illustrates how the system quickly approaches and finally stabilizes at the sliding surface, demonstrating the effectiveness and robustness of second-order SMC in achieving precise and stable tracking performance.

Figure 24.

Motion process diagram of second-order SMC.

Based on system (17), the second-order derivative of the sliding variable s is computed, yielding the following:

where . Furthermore, the second-order sliding mode (SOSM) dynamics (19) can be expressed as , where denotes the virtual controller to be designed; represents the lumped uncertainty composed of system states and external disturbances, with its specific expression formulated as Consequently, a SOSM path tracking controller is designed as follows:

where and denote control parameters to be appropriately designed.

- (3)

- Conventional super-twisting SMC

Based on the principles of SOSM described above, the conventional STSM path tracking controller is given by the following expression:

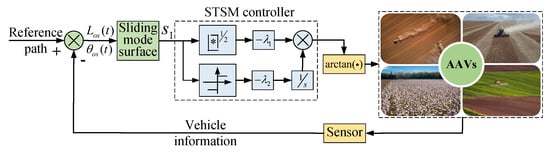

where both and are positive constants. Figure 25 presents a schematic representation of the conventional STSM-based control architecture, which is implemented for agriculture vehicle path tracking.

Figure 25.

Block diagram of super-twisting SMC.

- (4)

- Continuous super-twisting SMC

Furthermore, to tackle the path tracking problem of AAVs under sideslip conditions, Sun et al. [144] proposes a novel fixed-time continuous super-twisting control scheme. Firstly, the research team designed a novel fixed-time sliding surface , where represents an auxiliary dynamics to suppress the adverse sideslip angle. Then, can be expressed as , where , and . Therefore, an innovative continuous super-twisting path tracking controller is constructed as follows:

where and are positive constants. The proposed scheme was validated through theoretical analysis and field experiments, showing notable enhancements in path tracking accuracy and robustness in complex farmland environments, thereby providing key technological support for the implementation of precision agriculture.

- (5)

- Composite continuous super-twisting SMC

Building upon this structure, an extended state observer can be designed to achieve real-time disturbance estimation, with the observed disturbance values being feedforward compensated to the controller. By combining this approach with (22), a composite continuous super-twisting path tracking controller can be derived as follows:

where represents the estimation of disturbance.

Table 4 summarizes different super-twisting SMC methods for AAV path tracking. The comparison highlights a fundamental trade-off between robustness, control smoothness, and system complexity. This framework aids in selecting the optimal controller depending on specific operational requirements.

Table 4.

Comparison of different super-twisting SMC methods.

In addition, Yin et al. [145] presented an adaptive SMC strategy that exploits lateral offset feedback. Incorporating tunable parameters associated with the sliding manifold and system deviation, the scheme enables gain scheduling according to evolving states. Then, Ji et al. [146] present a composite adaptive terminal SMC strategy driven by a finite-time disturbance observer (FDO) to address path tracking of AAVs under unknown disturbances. The FDO precisely reconstructs non-matched perturbations, while an integral terminal sliding surface guarantees finite-time convergence of lateral offset. Subsequently, Salamah et al. [147] introduces an anti-jackknife adaptive sliding mode controller for articulated vehicle reversing. Simulations demonstrate improved reversing safety without compromising computational efficiency, offering a reliable path tracking solution for freight and agricultural autonomous systems. Expanding on this work, Ji et al. [148] developed a path tracking strategy for an unmanned agricultural tractor that integrates an enhanced STSM controller with a disturbance observer. By replacing the traditional SMC sign function with a nonsmooth term and incorporating disturbance feedforward compensation, chattering was effectively reduced while control performance was improved. Moreover, Zhang et al. [149] proposed a novel path tracking control method that integrates nonsingular fast terminal SMC with a finite-time disturbance observer. This approach effectively ensures rapid convergence of tracking errors while suppressing chattering phenomena, significantly enhancing the tracking performance of autonomous navigation systems for agricultural tractors.

3.3. Summary of Methods for AAVs Path Tracking

As the principal content of this section, Table 5 enumerates and contrasts representative path tracking control methods for AAVs, while clearly delineating the working scenarios to which each method is applicable. This table establishes a systematic taxonomy of path tracking control methods, categorizing them into model-free and model-based approaches.

Table 5.

Model-free and model-based classification of path tracking control methods.

Table 6 establishes a systematic comparative framework for path tracking control methods of AAVs, succinctly presenting the governing equations and key assumptions for a range of strategies from classical PID to advanced SMC variants. This table only lists the typical final expressions of the methods related to the model to more intuitively see the characteristics of each method. Moreover, this provides a concise reference for evaluating their theoretical underpinnings and applicability conditions.

Table 6.

Comparative framework of path tracking control methods for AAVs.

Table 7 provides a systematic synthesis and comparative overview of prevailing path tracking methods for AAV. The table presents an explicit comparison of the benefits and drawbacks of various control methods. Overall, these methods exhibit significant trade-offs in terms of performance, complexity, and applicability.

Table 7.

Comparative analysis of path tracking control methods.

This section systematically frames the dominant path tracking paradigms for AAVs, classifying them into linear control and nonlinear control classes. Representative algorithms are examined in terms of their control principles, scenario suitability, key advantages, and main limitations. Current research focuses on enhancing adaptability, robustness, and localization accuracy within unstructured and complex field conditions. The resulting advances establish a solid theoretical and technical foundation for addressing forthcoming practical challenges and solutions in this domain.

4. Research on the Key Performance Improvement of AAV Path Tracking

The methods of AAV path tracking control were introduced in detail in the previous section. However, through a thorough review of the literature, it can be found that most of the existing navigation path tracking algorithms mainly focus on several types of problems for research. The following will analyze the relevant methods from the perspective of research problems.

4.1. Disturbance Rejection Capability Enhancement Under Complex Working Conditions

Accurate path tracking is a fundamental requirement for AAVs when navigating along predefined paths. However, in real-world field operations, these systems often face unknown disturbances, such as uneven terrain, wheel slippage, or sudden changes in soil conditions [151,152,153]. These disturbances can substantially impair tracking accuracy and vehicle stability, leading to inefficient operation or even safety risks. Considering these disturbances is crucial not only for improving tracking precision but also for ensuring stable and reliable vehicle performance under varying operational conditions.

For AAVs subject to sideslip and input saturation, Matveev et al. [154] devised a nonlinear SMC method for path tracking. Additionally, Taghia et al. [155] introduced a traditional SMC scheme combined with a nonlinear disturbance observer, which successfully applied first-order SMC to address path tracking for AAVs from the perspective of disturbance suppression and compensation. Liu et al. [156] developed an AAV path tracking method combining nonlinear MPC, which notably improved tracking accuracy and disturbance rejection through discretized kinematic models and real-time feedback correction. However, due to its high computational complexity, Ding et al. [157] proposed a barrier function adaptive SMC method based on a second-order disturbance observer for AAVs. By simultaneously estimating matched and unmatched disturbances through disturbance observer and integrating adaptive SMC, the method achieved robust tracking with barrier function designs enabling finite-time convergence and chattering elimination without requiring prior knowledge of disturbance bounds. Furthermore, Sun et al. [158] proposed a path tracking scheme for AAVs using an adaptive disturbance observer and fixed-time nonsingular terminal SMC. This approach employs a novel disturbance observer to estimate and compensate composite disturbances in real time, combined with fixed-time SMC to ensure path deviations converge to a neighborhood of the origin within a specified time.

4.2. Stability Enhancement Under Loss of Heading

In precision agriculture applications, dual-antenna RTK technology from GNSS has become essential for modern intelligent AAV navigation. Its broad adoption is motivated by centimeter-level positioning accuracy and reliable performance in challenging field conditions. By resolving phase differences between dual antennas, this technology not only provides planar coordinate positioning for AAV but also calculates the heading angle of the equipment, establishing a spatial pose reference for autonomous navigation systems in AAVs [159]. However, during field operations, dependence solely on satellite navigation can lead to interruptions in pose resolution due to satellite signal blockages and multi-path effects [160]. To address this, integration with IMUs becomes essential for heading estimation [161]. Notably, low-precision IMUs introduce dynamically accumulating errors in heading angles. In continuous operation scenarios, such error drift may result in centimeter-level positional deviations in the navigation system, directly impairing the alignment accuracy of agricultural implements and operational quality.

In practical agricultural working scenes, output feedback control techniques can be applied to the design of path tracking controllers in AAV navigation systems. This approach seeks to achieve high-precision stable control of path tracking systems under conditions of incomplete heading information. Numerous studies have applied output feedback control approaches to solve path tracking challenges in autonomous vehicle navigation [162,163,164,165]. Hu et al. [162] developed a robust H∞ static output feedback controller that achieves path tracking control for autonomous vehicles without using lateral velocity information. Then, Wang et al. [163] developed a dynamic output feedback-based robust shared controller for vehicle path tracking that accounts for different driver characteristics, transforming multi-objective H∞ control into single-objective control to reduce disturbance suppression constraints. Furthermore, Meléndez-Useros et al. [164] introduced a static output feedback-based fault-tolerant path tracking controller for distributed drive electric vehicles to handle steering actuator failures, needing only sensor data for straightforward implementation while greatly reducing tracking offset. However, these output feedback control methods are not suitable for AAVs when heading information is missing or inaccurate. To address this issue, Ding et al. [165] proposed an output feedback SMC-based path tracking method for AAVs. By reconstructing unknown system states and estimating lumped disturbances through a second-order robust exact differentiator, their approach achieves high-precision path tracking using only vehicle position deviation information, with the second-order sliding mode controller significantly reducing chattering while enhancing transient performance.

4.3. Tracking Accuracy Enhancement Under Sideslip Influence

The fundamental importance of AAV navigation technology in precision agriculture lies in its high-precision path tracking control, which directly determines the operational efficiency and quality of autonomous farming [166,167]. While significant achievements have been made under ideal conditions in existing research, practical operations on soft terrains such as grasslands, sandy soils, and paddy fields frequently experience tire slippage that significantly degrades system tracking accuracy and stability [101]. Although methods like heading disturbance compensation can partially mitigate slippage effects, current technologies still cannot completely eliminate their negative impacts. Particularly in challenging terrains, slippage may lead to aggravated path tracking offset or even system instability. Thus, comprehensive research of slippage dynamics and development of control algorithms with strong anti-slip capabilities are crucial for improving vehicle robustness and reliability under complex working conditions.

This issue constitutes a pivotal technical impediment demanding resolution within AAV navigation. Lenain et al. [168] analyzed steady-state control deviations caused by sideslip effects and designed an SMC with a nonlinear disturbance observer, demonstrating robustness through dynamic simulations and field experiments. Further, Han et al. [169] developed a slip estimation-based algorithm, validated through 3D simulations and field tests in paddy fields under low adhesion conditions. However, their method was highly dependent on high precision sensors and exhibited potential instability in extreme conditions. Additionally, Bayar et al. [170] introduced an SMC method for orchard vehicles, combining RTK-GPS and LiDAR for inter-row path tracking, achieving enhanced accuracy in muddy terrain. Lenain et al. [171] incorporated two slip angles into the ideal kinematic model to represent front and rear wheel sideslip and subsequently proposed a sideslip angle estimation strategy.

4.4. Integrated Performance Enhancement Under Model Parameter Perturbations

The path tracking control technologies for AAV can be classified into model-free and model-based approaches based on their dependency on system models. Model-free methods, which depend on data-driven techniques or adaptive mechanisms, demonstrate strong environmental adaptability but suffer from reduced control precision and stability under external disturbances. In contrast, model-based control strategies leverage precise kinematic or dynamic models of AAV to precisely describe steering behavior and motion patterns [172]. These strategies exhibit significant advantages, particularly in high-speed tracking of paths with time-varying curvature [173]. Moreover, model-based methods provide a structured framework for controller design. For instance, MPC dynamically optimizes front wheel steering angles through rolling horizon optimization, and SMC suppresses parameter perturbations and terrain disturbances with its inherent robustness, enabling high precision tracking under complex working conditions [149,174]. However, kinematics-based control schemes overlook the effects of vehicle body parameter perturbations, resulting in reduced performance in practical applications. Furthermore, when AAV tracks paths with time-varying curvature at high speeds, such kinematic control methods struggle to achieve high-precision tracking performance.

To address the model parameter perturbation issues in model-based methods, scholars have carried out extensive research [175]. Aguiar et al. [176] proposed a hybrid control architecture combining adaptive switching supervisory control with nonlinear Lyapunov-based tracking control. By producing state estimates of parameterized model sets through multiple estimators and dynamically selecting the optimal controller via hysteresis switching logic, they achieved global bounded convergence of trajectory tracking offset while effectively handling modeling parameter uncertainties. Then, Zheng et al. [177] developed an identification method integrating an improved optimal bounding ellipsoid algorithm with a multi-time scale recursive higher-order neural network. By introducing two adaptive gain terms into the weight update law, they enhanced the convergence speed and robustness of singularly perturbed systems under parameter uncertainties. Furthermore, Cheng et al. [178] designed an MPC-based path tracking controller for AAVs, focusing on reducing the impact of tire parameter uncertainties and time-varying speeds. By modeling tire cornering stiffness as a time-varying parameter and employing polytopic methods for linear parameter-varying modeling of vehicle speed, they developed a robust MPC controller using linear matrix inequalities (LMIs) to guarantee Lyapunov asymptotic stability and control accuracy under parameter perturbations. Expanding on this, Liu et al. [179] proposed an output feedback H∞ robust path tracking control method. Utilizing a linear parameter varying model to describe parameter uncertainties, they achieved robust control relying solely on partial state observations through LMI optimization, greatly enhancing tracking precision and stability in complex scenarios. Additionally, Ge et al. [180] introduced an adaptive first-order sliding mode path tracking control method, which dynamically adjusts the upper bounds of tire cornering stiffness and demonstrates strong robustness through experimental validation.

4.5. Summary

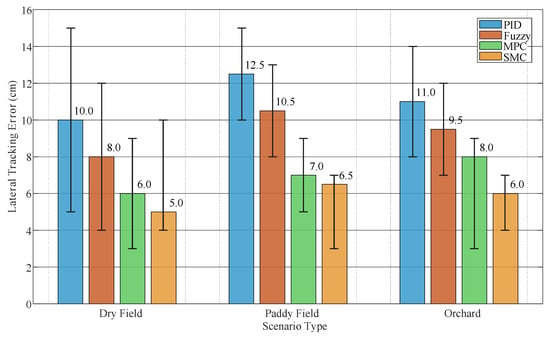

As illustrated in Figure 26, to better analyze how different scenarios quantitatively influence the tracking control accuracy and robustness of AAVs, we have summarized the lateral tracking errors of several typical methods under various working scenarios.

Figure 26.

Lateral tracking error comparison of typical methods in different scenarios.

Furthermore, Table 8 summarizes and compares representative research methods for improving the key performance of AAV path tracking control. The table categorizes the approaches according to four key performance aspects, covering disturbance rejection, stability, tracking accuracy, and integrated performance. Analysis reveals distinct solution trends: disturbance rejection predominantly employs advanced SMC variants and nonlinear MPC; stability issues are addressed through sensor fusion and robust feedback control; tracking accuracy is improved via disturbance observers and slip estimation; while integrated performance relies on adaptive and learning-based methods.

Table 8.

Comparison of methods for improving the performance of AAV path tracking.

5. Challenges and Future Trends

Significant advances have been achieved in AAV path tracking control, spanning kinematic and dynamic modeling, as well as the design of sophisticated control algorithms. This section concentrates on the current challenges and emerging trends in the field, seeking to outline viable directions for future research.

5.1. Challenges

The development and implementation of robust path tracking control for AAVs are confronted with several profound challenges. These challenges include vehicle modeling, controller design, environmental adaptability, and algorithm universality, which impose limitations on achieving high precision and reliable autonomous operation in actual agricultural environments. The following subsections break down each of these challenges in detail.

5.1.1. Vehicle Model

The performance of AAV path tracking control is heavily reliant on the accuracy and applicability of the employed vehicle models [181]. However, establishing a precise unified model capable of comprehensively characterizing the dynamic behavior of AAV operating in realistic, complex field environments poses complex challenges of considerable magnitude. The primary challenge stems from the unstructured nature of agricultural field conditions. During operation, AAVs traverse terrain of varying topography. These changes induce multidegree variations in vehicle attitude and produce complex dynamic interactions between the tires and the soil. These interactions significantly influence tire longitudinal slip, lateral slip characteristics, and traction properties [182]. Furthermore, soil type, moisture content, and surface coverage dynamically modify wheel–terrain contact mechanics, rendering conventional wheeled vehicle models inadequate for precise modeling.

A distinctive characteristic of AAVs, setting them apart from conventional automobiles, lies in their operational dependence on mounted or towed implements. The attached cause major changes to mass distribution, center of gravity position, and moment of inertia of the vehicle. More importantly, they generate complex force and torque coupling effects. As a result, dynamic parameters of the vehicle system show significant variation with operational conditions. In practical operations, AAVs frequently undergo operational mode transitions and velocity variations and implement elevation adjustments. These operational changes lead to continuous dynamic variations in gross vehicle mass, inertial properties, and key dynamic parameters, thereby exacerbating the challenges in developing universally applicable models. Finally, comprehensive modeling typically requires extensive physical parameter inputs. Many key parameters, such as tire–soil interaction coefficients and implement soil force parameters, are challenging to measure or identify accurately under real field conditions. These challenges are intrinsically interconnected, collectively forming a significant modeling problem characterized by strong nonlinearity, high coupling complexity, parameter uncertainty, and significant time-varying characteristics.

5.1.2. Controller Design

Designing path tracking controllers for AAVs involves a set of distinct and demanding challenges. These challenges arise mainly from nonlinearities, strong coupling, and parameter uncertainties that stem from complex field environments, implement vehicle interactions, and inherent system characteristics [148]. A vital requirement is to sustain robustness and precision within unstructured and ever-changing agricultural working conditions. Undulating terrain and soft, slippery soils directly disturb vehicle dynamics and markedly change tire–ground interaction forces, so conventional linear control strategies that rely on simplified models highly limited or even ineffective. This necessitates the development of advanced control algorithms capable of actively compensating for or adapting to these unknown or time-varying external disturbances. Furthermore, the complex dynamic coupling between AAVs and their mounted or towed implements substantially increases control difficulties.

The characteristic low speed, high mass, and high inertia properties of AAV introduce additional difficulties by causing system response delays and complicating precise, smooth tracking of complex paths. This is particularly evident when attempting to simultaneously satisfy tracking accuracy and actuator constraints, where traditional controllers often cannot balance responsiveness with stability. Moreover, high-precision path tracking typically requires reliable real-time vehicle state estimation [183]. However, field conditions pose significant challenges to sensors such as GNSS and IMUs, where sensor noise, data loss, latency, or drift can directly compromise controller input quality. This underscores the critical need for developing intelligent controllers with enhanced robustness. Finally, the pursuit of superior performance often leads to more sophisticated controller architectures, yet their substantial computational demands conflict with the limited processing capabilities of current AAV onboard systems. Such advanced controllers frequently face implementation challenges regarding real-time performance, cost effectiveness, and reliability, requiring careful trade offs between algorithmic performance, computational complexity, and practical engineering feasibility.

5.1.3. Tracking Accuracy in Complex Environments

The path tracking accuracy of AAV encounters substantial challenges in complex field environments, primarily resulting from the intricate disturbances caused by scenario-specific physical conditions on both vehicle kinematics and sensing systems [184,185]. In paddy fields, wheel sinkage depth critically influences tracking accuracy. Deep mud reduces the effective rolling radius, causing systematic discrepancies between the distance inferred from wheel speed and the true displacement. During dry field operations, the geometrically regular arrangement of field ridges considerably influences vehicle trajectories, with mismatches between furrow dimensions and wheelbase frequently inducing lateral oscillations. When operating on sloped terrain, the gravitational force component parallel to the incline generates persistent downhill drift, which is especially difficult to correct in real time due to limitations in slope sensor accuracy and response latency. Furthermore, orchards and other tall crop environments interfere with positioning systems. Dense canopy often blocks satellite signals or degrades accuracy, making centimeter-level real-time positioning unattainable [186]. These challenges mainly arise from the inherent problem in real-time quantification of environmental variables, compounded by the inadequate adaptability of existing control strategies to abrupt environmental variations, ultimately resulting in path tracking systems struggling to maintain both precision and stability under complex operational conditions.

5.1.4. Adaptability of Algorithms to Different Scenarios

The adaptability of AAV path tracking algorithms across diverse operational scenarios poses significant challenges, primarily due to conventional algorithms’ limited capacity to handle the highly time-varying and nonlinear characteristics inherent to agricultural environments. The geometric pure pursuit algorithm performs reliably along straight trajectories on dry land fields. In paddy fields, strong tire–mud interactions cause considerable differences between actual and theoretical turning radius, markedly increasing tracking offset [187,188]. The Stanley method, while effective in suppressing lateral deviations through heading angle correction in orchard navigation, suffers from resonance effects between its inherent heading damping and periodic vehicle oscillations in ridge tillage operations, thereby increasing cross-track offset. MPC delivers clear advantages on sloped terrain by using receding horizon optimization to anticipate and counteract gravity-induced lateral drift. The computational burden of detailed dynamic models, however, prevents real-time deployment on resource-limited controllers in AAVs. Adaptive PID control exhibits improved performance across varying soil conditions through parameter self-tuning mechanisms, yet demonstrates overshoot oscillations during transitional periods when facing abrupt parameter changes caused by implement operations [189,190]. Current algorithm optimizations mainly concentrate on singular performance metrics, whereas practical agricultural operations necessitate simultaneous satisfaction of multiple competing constraints. Multi-objective optimization prevents any single algorithm from performing optimally in all scenarios, necessitating more sophisticated adaptive control for agricultural automation.

5.2. Summary of the Challenges