Reduction of Pesticide Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur Residues via Plasma-Activated Water Generated by a Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

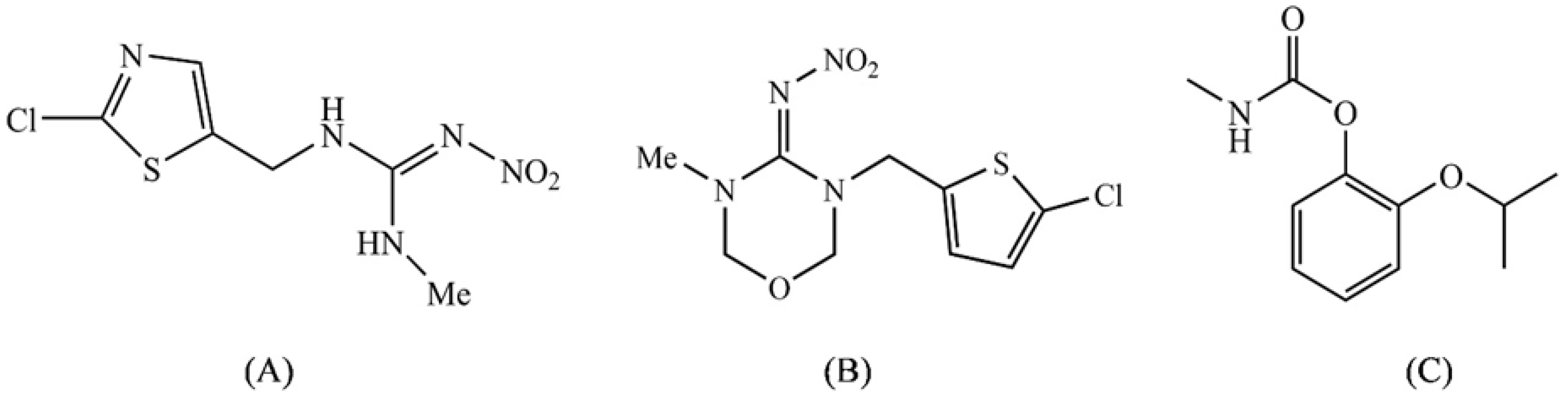

2.1. Chemicals

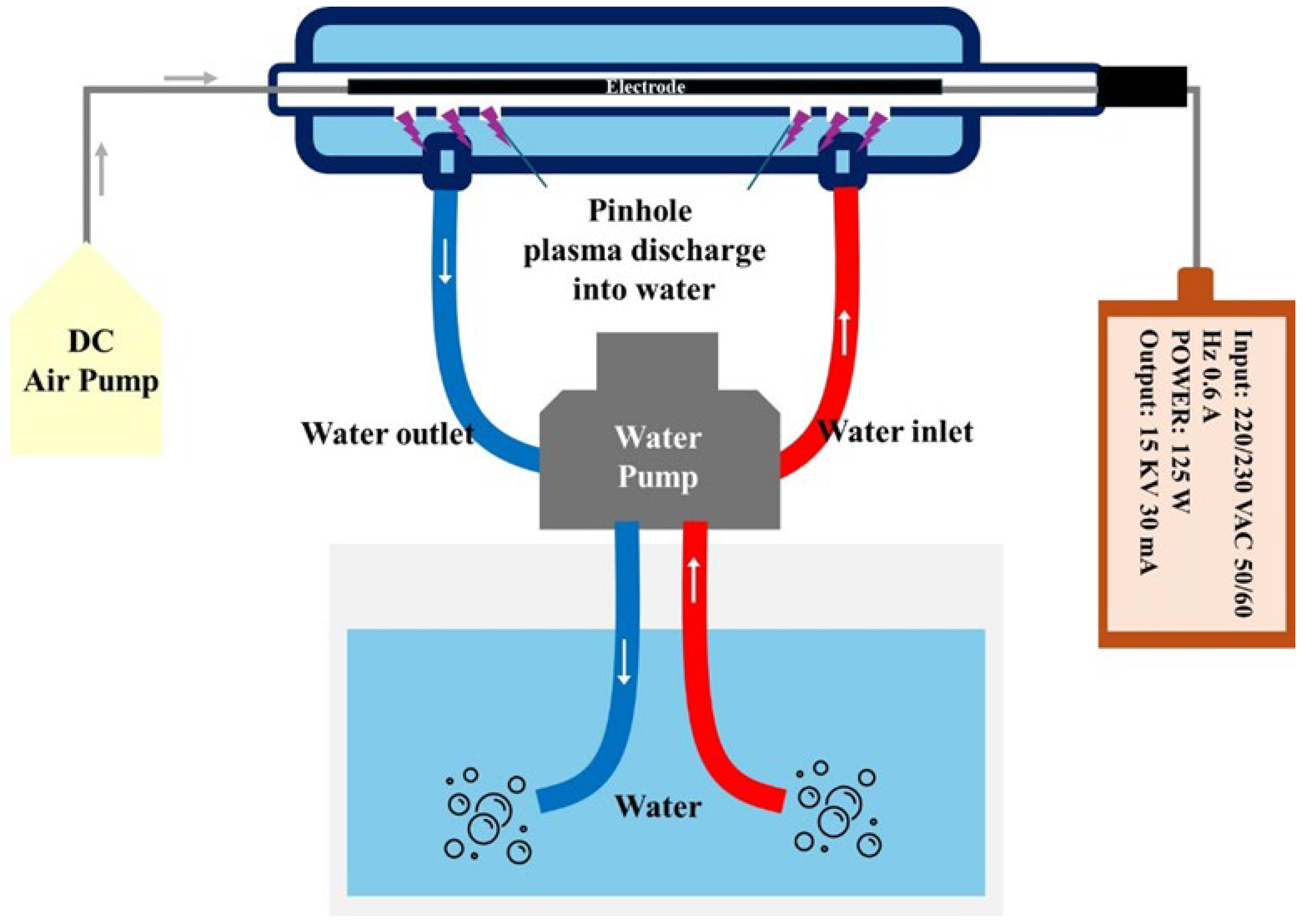

2.2. Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet

2.3. Generation of Plasma in Pesticide Solutions by Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet System

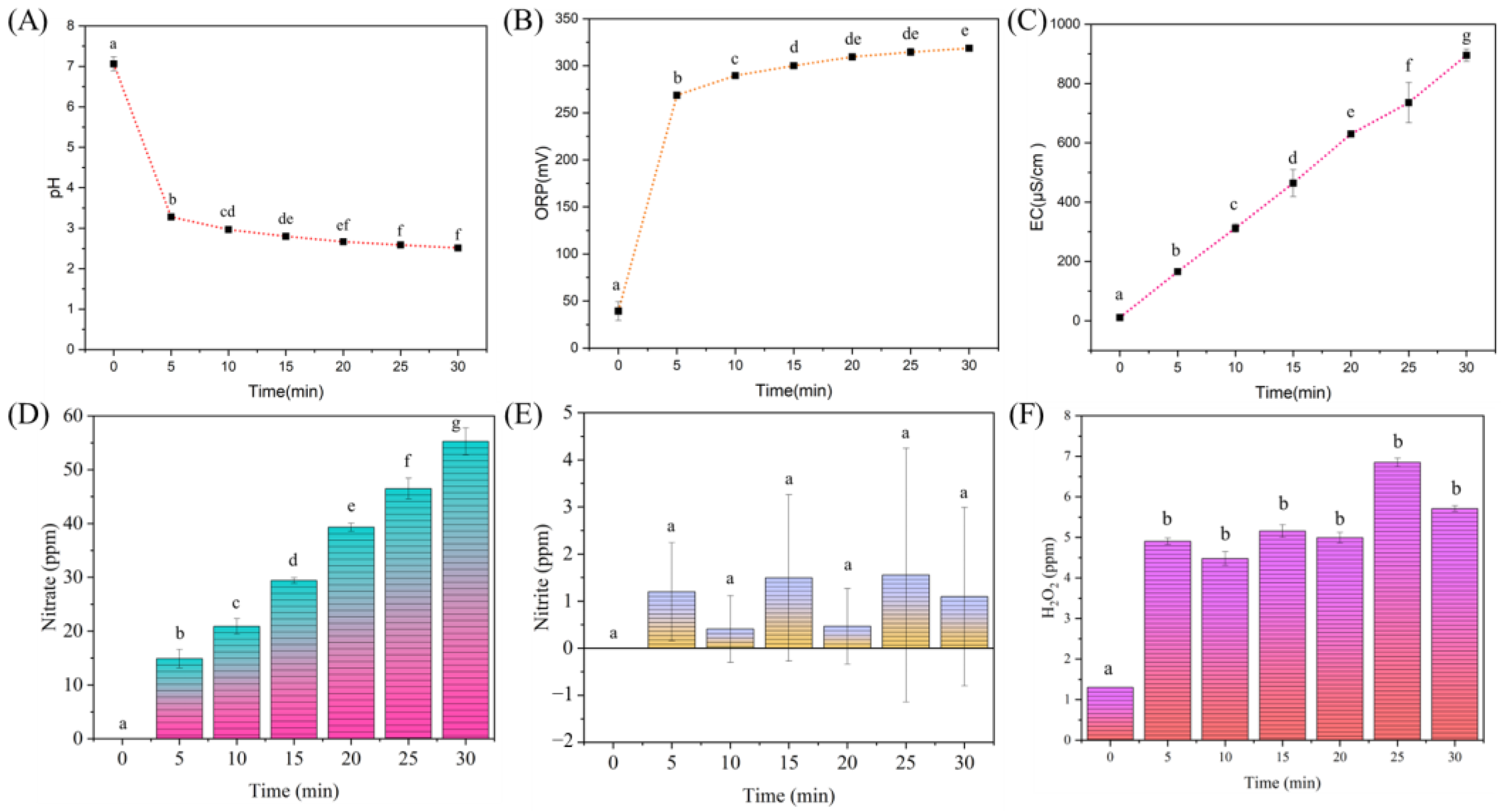

2.4. Physicochemical Properties of PAW

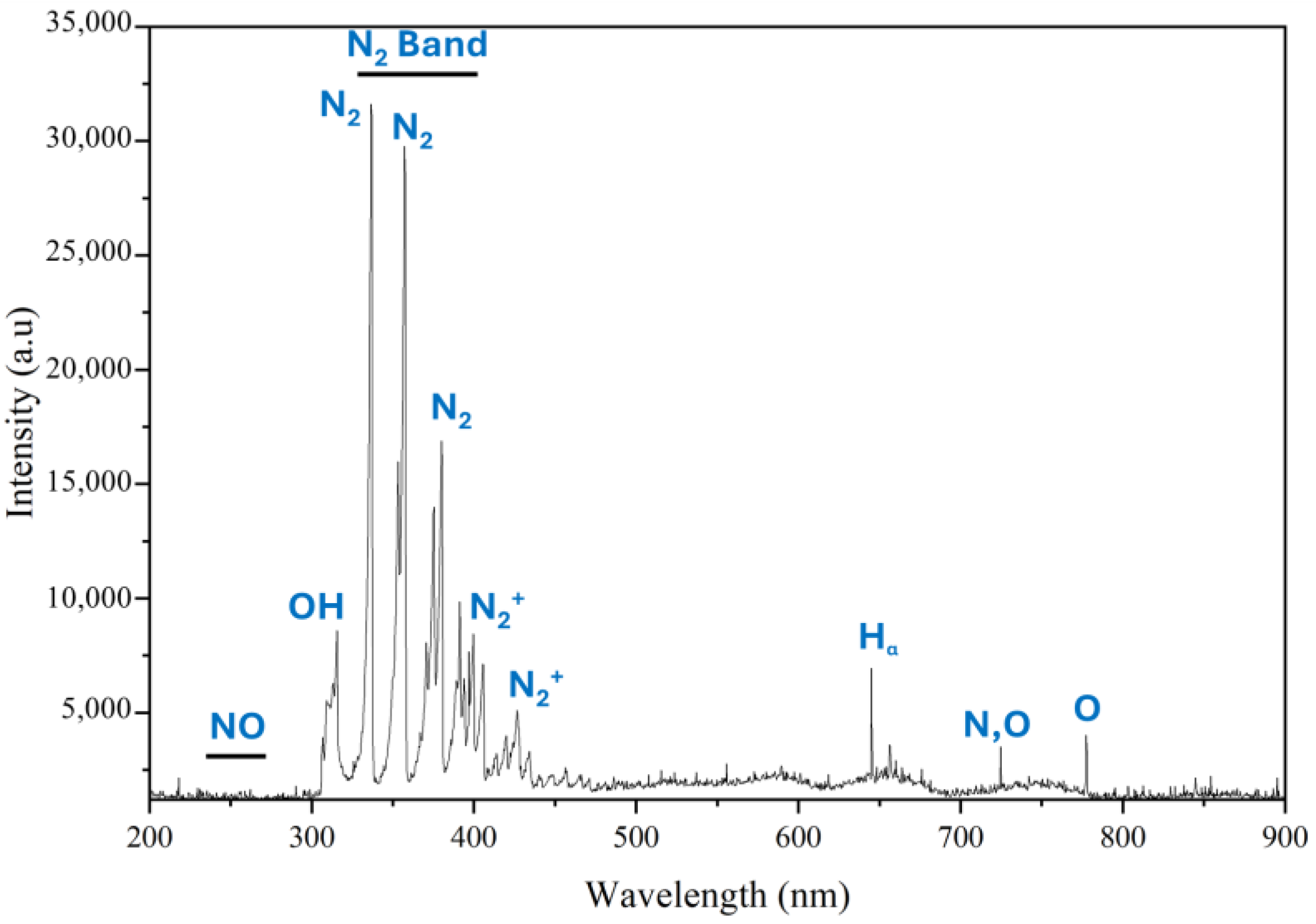

2.5. Optical Emission Spectrometry (OES) Analysis

2.6. HPLC and LC-MS Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of PAW

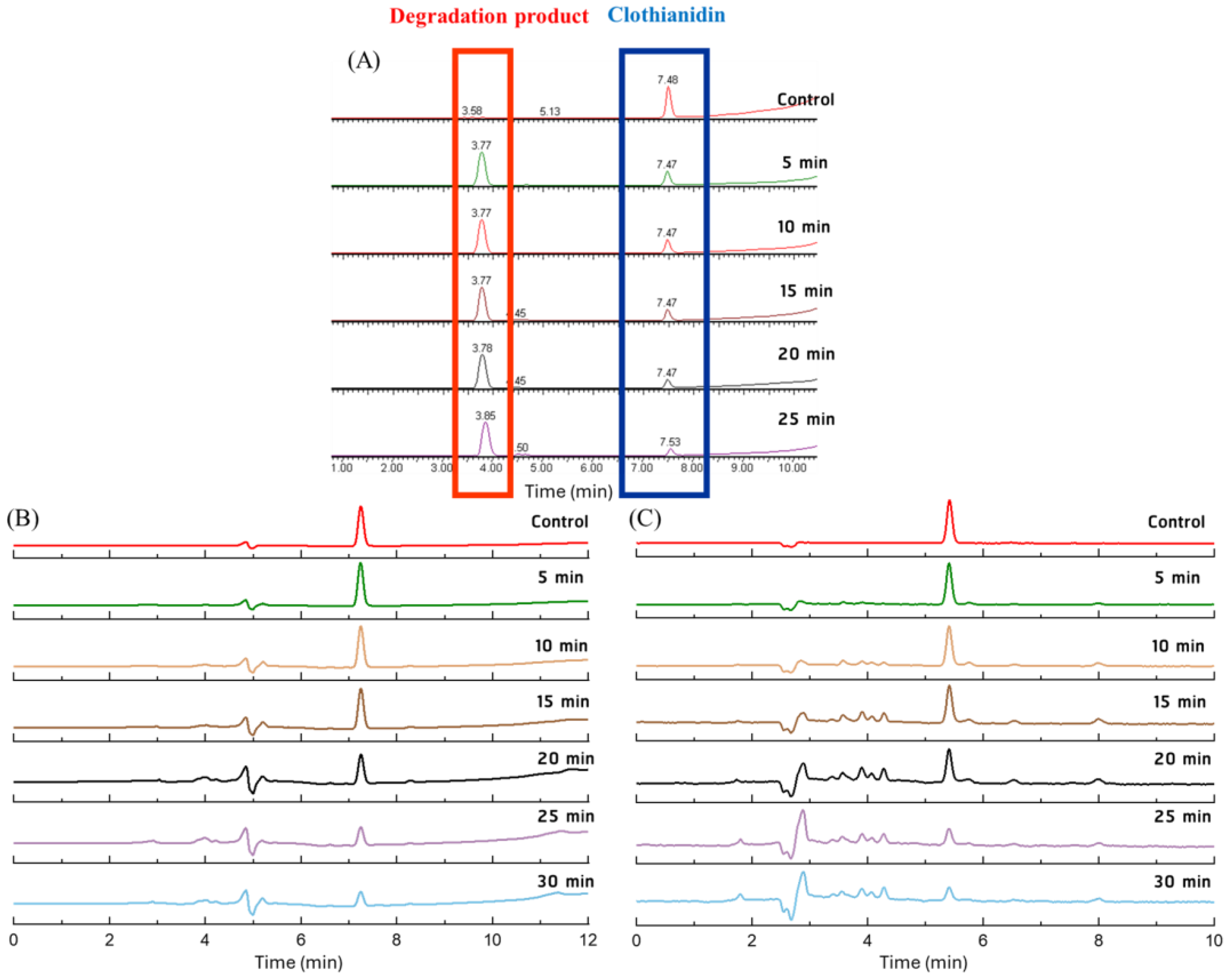

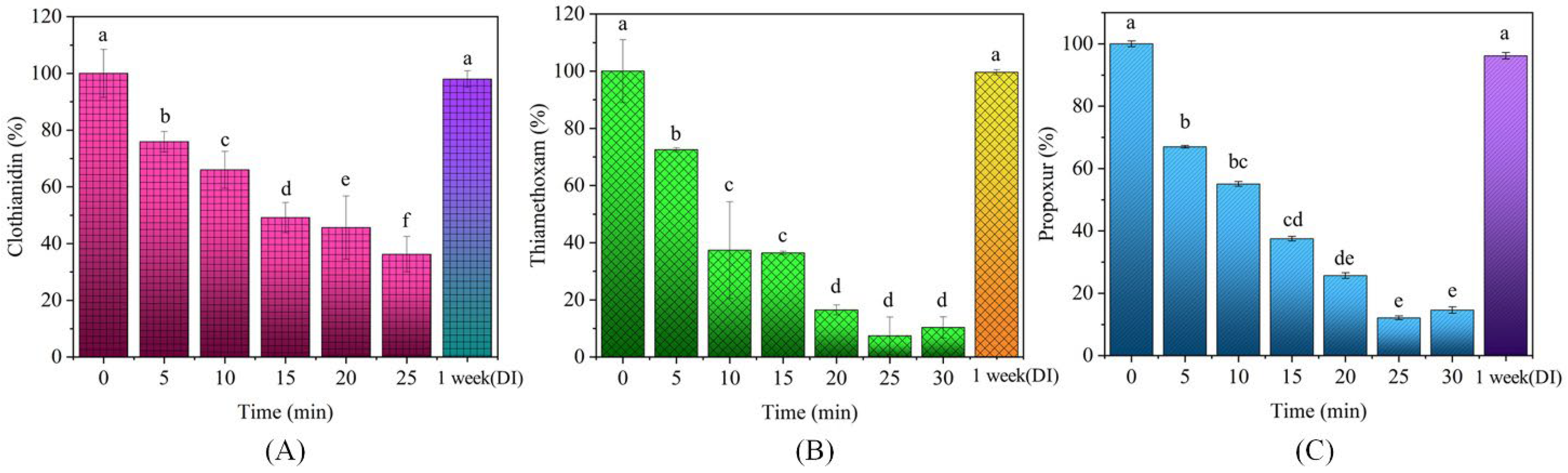

3.2. Effect of PAW on the Degradation of Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur

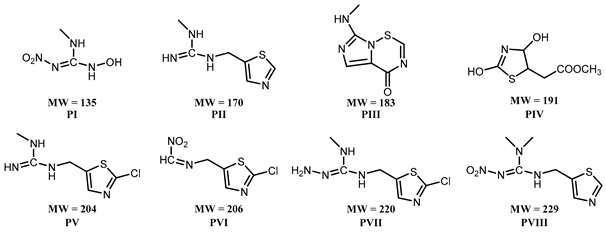

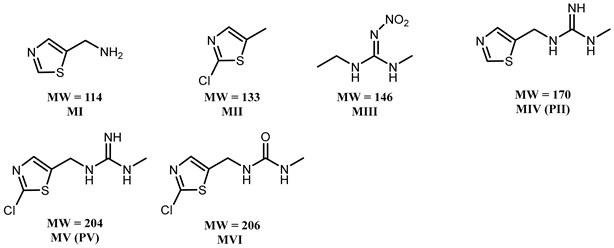

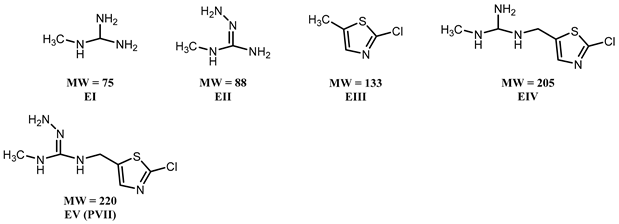

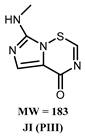

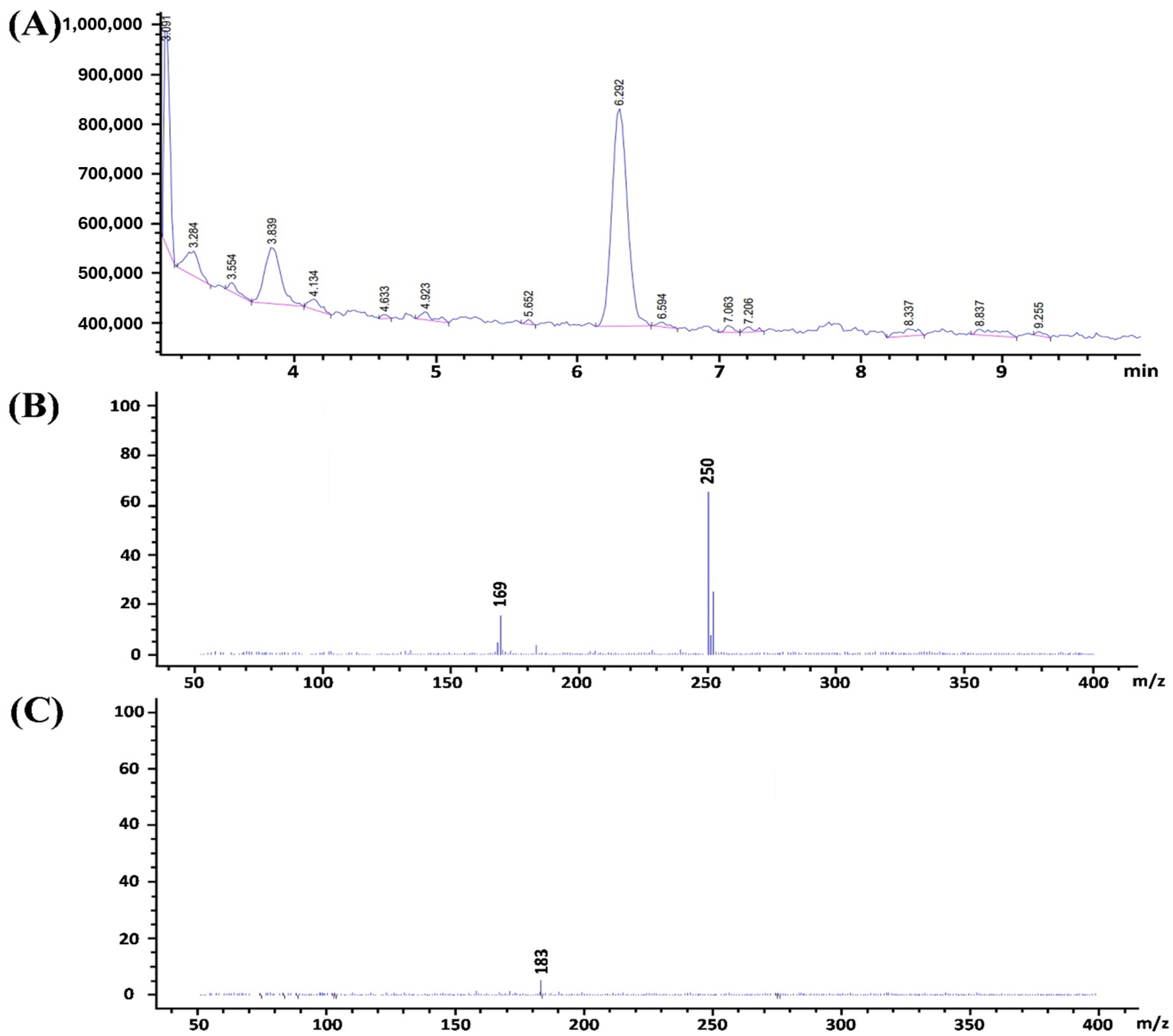

3.3. Proposed Pathway for the Degradation of Pesticides by PAW

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAW | Plasma-Activated Water |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Specie |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Specie |

| ORP | Oxidation–Reduction Potential |

| EC | Electrical Conductivity |

References

- Kaur, R.; Choudhary, D.; Bali, S.; Bandral, S.S.; Singh, V.; Ahmad, M.A.; Rani, N.; Singh, T.G.; Chandrasekaran, B. Pesticides: An alarming detrimental to health and environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 170113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonmatin, J.-M.; Giorio, C.; Girolami, V.; Goulson, D.; Kreutzweiser, D.P.; Krupke, C.; Liess, M.; Long, E.; Marzaro, M.; Mitchell, E.A.D.; et al. Environmental fate and exposure; neonicotinoids and fipronil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Lee, H.K. Stability studies of propoxur herbicide in environmental water samples by liquid chromatography–atmospheric pressure chemical ionization ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1014, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyan, P.; Kandeepan, Y.; Chen, T.-W.; Chen, S.-M.; Binobead, M.A.; Elsadek, M.F.; Elshikh, M.S. Metallic silver-alloyed copper oxide electro-catalyst: A high-sensitivity platform for propoxur insecticide detection in food samples. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 165, 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sojithamporn, P.; Leksakul, K.; Sawangrat, C.; Charoenchai, N.; Boonyawan, D. Degradation of pesticide residues in water, soil, and food products via cold plasma technology. Foods 2023, 12, 4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharini, M.; Jaspin, S.; Mahendran, R. Cold plasma reactive species: Generation, properties, and interaction with food biomolecules. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, L.; Liu, N.; Sun, Z. Effective degradation of lindane and its isomers by dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma: Synergistic effects of various reactive species. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Jin, X.; Hu, S.; Lan, Y.; Xi, W.; Han, W.; Cheng, C. Study on the effective removal of chlorpyrifos from water by dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma: The influence of reactive species and different water components. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 473, 144755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayarangan, V.; Maaroufi, Z.; Rouillard, A.; Gaetan-Zin, S.; Dozias, S.; Escot-Bocanegra, P.; Stancampiano, A.; Grillon, C.; Robert, E. Plasma jet and plasma treated aerosol induced permeation of reconstructed human epidermis. Bioelectrochemistry 2026, 167, 109060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.; Ngamrung, S.; Ano, V.; Umongno, C.; Mahatheeranont, S.; Jakmunee, J.; Nisoa, M.; Leksakul, K.; Sawangrat, C.; Boonyawan, D. Comparison of plasma technology for the study of herbicide degradation. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 14078–14088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimončicová, J.; Kryštofová, S.; Medvecká, V.; Ďurišová, K.; Kaliňáková, B. Technical applications of plasma treatments: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5117–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polukhin, S.N.; Gurei, A.E.; Nikulin, V.Y.; Peregudova, E.N.; Silin, P.V. Studying how plasma jets are generated in a plasma focus. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2020, 46, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosumsupamala, K.; Thana, P.; Palee, N.; Lamasai, K.; Kuensaen, C.; Ngamjarurojana, A.; Yangkhamman, P.; Boonyawan, D. Air to H2-N2 pulse plasma jet for in-vitro plant tissue culture process: Source characteristics. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2022, 42, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawut, N.; Leksakul, K.; Vichiansan, N.; Wichitthanabodee, P.; Boonyawan, D.; Leksakul, S. Impact of plasma-generated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) on apoptosis induction in LN229 cells. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2026, 111, 108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickenson, A.; Walsh, J.L.; Hasan, M.I. Electromechanical coupling mechanisms at a plasma–liquid interface. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 213301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perinban, S.; Orsat, V.; Raghavan, V. Effect of plasma-activated water treatment on physicochemical and functional properties of whey protein isolate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Xie, J.; He, C. Plasma-activated water production and its application in agriculture. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4891–4899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarabová, B.; Lukeš, P.; Janda, M.; Hensel, K.; Šikurová, L.; Machala, Z. Specificity of detection methods of nitrites and ozone in aqueous solutions activated by air plasma. Plasma Process. Polym. 2018, 15, 1800030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Nitrates. European Commission. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/water/nitrates_en (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Femia, J.; Mariani, M.; Zalazar, C.; Tiscornia, I. Photodegradation of chlorpyrifos in water by UV/H2O2 treatment: Toxicity evaluation. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 2279–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelli, F.; Laghi, G.; Laurita, R.; Puač, N.; Gherardi, M. Recommendations and guidelines for the description of cold atmospheric plasma devices in studies of their application in food processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 97, 103818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, M.Y.; Shukrullah, S.; Rehman, S.U.; Khan, Y.; Al-Arainy, A.A.; Meer, R. Optical characterization of non-thermal plasma jet energy carriers for effective catalytic processing of industrial wastewater. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thana, P.; Boonyawan, D.; Jaikua, M.; Promsart, W.; Rueangwong, A.; Ungwiwatkul, S.; Prasertboonyai, K.; Maitip, J. Plasma-activated water (PAW) decontamination of foodborne bacteria in shucked oyster meats using a compact flow-through generator. Foods 2025, 14, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laux, C.O.; Spence, T.G.; Kruger, C.H.; Zare, R.N. Optical diagnostics of atmospheric pressure air plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2013, 12, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.; Judée, F.; Yousfi, M.; Vicendo, P.; Merbahi, N. Analysis of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generated in three liquid media by low temperature helium plasma jet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Gao, P.; Li, S.; Shen, J.; Lan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chu, P.K. Cold atmospheric-pressure air plasma treatment of C6 glioma cells: Effects of reactive oxygen species in the medium produced by the plasma on cell death. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2017, 19, 025503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sarangapani, C.; Scally, L.; Gulan, M.; Cullen, P.J. Dissipation of pesticide residues on grapes and strawberries using plasma-activated water. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Separation and identification of photolysis products of clothianidin by ultra-performance liquid tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Lett. 2012, 45, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Cui, D.; Zhong, G.; Liu, J. Microbial technologies employed for biodegradation of neonicotinoids in the agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 759439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić Visković, B.; Maslač, A.; Dolar, D.; Ašperger, D. Use of simulated sunlight radiation and hydrogen peroxide to remove xenobiotics from aqueous solutions. Processes 2023, 11, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dong, X.; Chen, H.; Li, S. Preparation and electrochemical treatment application of Ti/Sb–SnO2-Eu&rGO electrode in the degradation of clothianidin wastewater. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129126. [Google Scholar]

- Reema, R.; Bedmutha, T.; Kakati, N.; Rayala, V.V.S.P.K.; Radhakrishnanand, P.; Juliya Devi, C.; Thakur, D.; Sankaranarayanan, K. Ethidium bromide degradation by cold atmospheric plasma in water and the assessment of byproduct toxicity for environmental protection. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 48044–48054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Limkoey, S.; Yuenyong, J.; Bennett, C.; Boonyawan, D.; Sookwong, P.; Mahatheeranont, S. Reduction of Pesticide Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur Residues via Plasma-Activated Water Generated by a Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232521

Limkoey S, Yuenyong J, Bennett C, Boonyawan D, Sookwong P, Mahatheeranont S. Reduction of Pesticide Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur Residues via Plasma-Activated Water Generated by a Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232521

Chicago/Turabian StyleLimkoey, Suchintana, Jitkunya Yuenyong, Chonlada Bennett, Dheerawan Boonyawan, Phumon Sookwong, and Sugunya Mahatheeranont. 2025. "Reduction of Pesticide Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur Residues via Plasma-Activated Water Generated by a Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232521

APA StyleLimkoey, S., Yuenyong, J., Bennett, C., Boonyawan, D., Sookwong, P., & Mahatheeranont, S. (2025). Reduction of Pesticide Clothianidin, Thiamethoxam, and Propoxur Residues via Plasma-Activated Water Generated by a Pin-Hole Air Plasma Jet. Agriculture, 15(23), 2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232521