Abstract

Rice plays a pivotal role in global food security, particularly for Asian populations. However, its production is significantly threatened by insect pests, with Chilo suppressalis being a major pest in Asian rice-growing regions. Therefore, developing accurate predictive models for C. suppressalis outbreaks is essential. This study presents a novel time series forecasting model (named ESD-TripleStream) for C. suppressalis population dynamics based on a multi-stream structure, which addresses the limitations of existing approaches, which often omit the further decomposability of and the timestamp information in the time series. This model integrates Exponential Smoothing Decomposition (ESD) to separate the trend and seasonal components of time series data, along with a temporal feature stream to form a three-stream network to capture multi-scale periodic patterns and temporal dependencies. For our evaluation, we collected and constructed a novel dataset, referred to as HNRP-6R, which includes rice pest monitoring data from the past two decades (2000–2022) alongside 13 meteorological factors across six key rice producing regions in Hunan Province, southern China. ESD-TripleStream was evaluated across short-term and medium-term C. suppressalis population prediction scales using HNRP-6R, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance. Specifically, in short-term prediction, ESD-TripleStream achieved a 31.8% reduction in Mean Squared Error (MSE) and 26.55% reduction in Mean Absolute Error (MAE) compared to the PatchMLP model, while outperforming the transformer-based TimeXer by 14.43% in MSE and 9.8% in MAE. For medium-term prediction, ESD-TripleStream has both MSE and MAE significantly lower than those of baseline models such as P-sLSTM and xPatch. Furthermore, generalization tests on Nilaparvata lugens (N. lugens) population prediction demonstrated the model’s adaptability to diverse pest dynamics.

1. Introduction

Rice represents one of the most essential staple food crops worldwide. For more than half of the global population, rice remains fundamental to their survival and livelihoods [1,2]. Insect pest infestations, however, significantly impact rice production. These infestations cause annual declines in global rice yields ranging from 20% to 40% [3]. The Rice Stem Borer (RSB), Chilo suppressalis, represents a major lepidopteran pest threatening rice cultivation across Asia [4]. As a stem-boring insect, it damages rice plants throughout their developmental stages, from vegetative growth to reproductive maturation [5]. The C. suppressalis life cycle comprises four sequential developmental stages: egg (3~7 day), larva (15~25 day), pupa (7~10 day), and adult (5~7 day) [6]. During the egg stage, C. suppressalis eggs are primarily on the undersides of leaves, near the leaf sheaths. In the larval stage, the larvae penetrate rice stems and rhizomes to feed on plant sap, making this the most damaging stage for rice. When temperatures reach 11 °C or higher, larvae pupate either within stems or between leaf sheaths and stems. Adult C. suppressalis emerge when temperatures exceed 15 °C; generally speaking, the male-to-female ratio is approximately 1:1, and a female lays an average of 100~300 eggs. They exhibit nocturnal activity, possess a certain flight capacity (which can affect their local abundance), and remain concealed at the base of rice plants during the day [7]. This developmental pattern makes the comprehensive visual monitoring of C. suppressalis’s destructive activities virtually impossible. Although there are some natural enemies, such as Trichogrammatidae and Apanteles ruficrus, which can significantly reduce species abundance, these natural enemies still need to be artificially released. Therefore, developing accurate predictive models for C. suppressalis population dynamics becomes critically important for guiding integrated pest management strategies [8]. These models focus on (1) enabling early intervention through infestation forecasting, and (2) facilitating precise insecticide application to minimize pest resistance development and environmental contamination [9,10,11].

Artificial intelligence technology has been widely applied, and smart agriculture has also achieved rapid development in recent years [12]. This progress has been accompanied by an important trend: the application of time series analysis and machine learning techniques for accurate pest infestation prediction [13,14,15,16]. Traditional time series prediction models have been widely implemented in agricultural research. The Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model, for example, has proven effective in rice yield prediction and pest infestation forecasting [17]. However, traditional models demonstrate notable limitations in agricultural pest prediction, particularly regarding medium-term forecasting and real-world scenario adaptation. These limitations stem from inherent constraints: (1) sole dependence on univariate time series data, (2) insufficient handling of nonlinear and non-stationary datasets, and (3) inability to incorporate multi-factorial interactions and biological characteristics. Addressing these challenges, researchers increasingly combine traditional time series prediction models with deep neural networks [18,19]. Some researchers have utilized ARIMA and Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) to predict Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner), enhancing prediction accuracy [20]. The integration of ARIMA and grey models has been applied to cocoa yield prediction, showing promising results even with limited data [21]. Additionally, researchers have exploited the advantages of two models for the Yellow Stem Borer (YSB)—a major rice pest [22]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at local feature extraction, while Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is well-suited for time series data. They combined these two models to develop prediction and classification frameworks.

While these advancements have improved model predictive capabilities, they still inadequately address long-term dependencies and nonlinear relationships inherent in time series data [23,24]. In practical agricultural scenarios, pest outbreaks demonstrate strong correlation with weather and climatic factors [25,26,27]. Research indicates that stem-boring pests are particularly vulnerable to climate change in China [28,29]. Building on these insights, researchers increasingly incorporate meteorological factors into predictive frameworks, conducting multivariate time series predictions and interpretability analyses [30]. For instance, bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and LSTM have been used to forecast cotton pest outbreaks [31]. Researchers incorporated climatic variables into the models, which achieved an AUC of 0.95. This result demonstrates the importance of climatic parameters for pest dynamics. Similarly, the BCNN–LSTM model has been applied to tobacco disease prediction [32]. It incorporates bidirectional convolution to capture interactions between meteorological factors. This design substantially improves the model’s ability to characterize nonlinear and dynamic features.

The previously mentioned models have demonstrated effectiveness in predicting agricultural pests and diseases. However, they process time series as uniform inputs, overlooking a fundamental structural property: time series comprise trend components and seasonal components, with potential interference between them. This limitation becomes particularly evident when analyzing agricultural pest data with pronounced seasonality or complex trends, potentially compromising prediction accuracy. Time series forecasting employs established decomposition frameworks to separate and model these components independently [33,34,35]. For example, the Dlinear model obtains trend components using a moving average kernel. Then, it derives seasonal components by calculating the difference between the original time series and the obtained trend components. Finally, each component is processed through a single linear layer, after which they are weighted [36,37]. However, after decomposing the time series, the DLinear model only processes both of the decomposed components through a single simple linear layer. This approach overlooks the high-frequency periodicity inherent in the seasonal component and the weak linearity existing in the trend component. When faced with the respective characteristics of these two decomposed branches, the model fails to conduct targeted modeling for them. Additionally, traditional time series prediction models tend to neglect the inherent cycles of different features during encoding and overlook the significance of timestamps in time series prediction.

To address the aforementioned issues, we propose a novel deep learning-based multiple-stream framework for C. suppressalis population forecasting. Unlike traditional decomposition methods (e.g., the moving average method) that struggle to handle data with dynamic evolution patterns, Exponential Smoothing Decomposition (ESD) uses exponentially decaying weights to prioritize recent observations, thereby better adapting to the dynamic change characteristics of the data [38]. This enables ESD to adapt more rapidly to trend shifts and eliminates the need for data padding. The proposed framework begins by decomposing the input time series into trend and seasonal components using ESD. Additionally, a temporal feature stream is also incorporated to process the original C. suppressalis series along with highly correlated meteorological factors, thereby effectively capturing multi-scale temporal patterns. Within this stream, distinct path lengths are utilized for different temporal features, such as months and seasons [39,40]. The overall architecture thus consists of three streams: a seasonal stream, a trend stream, and a temporal feature stream. We refer to the proposed framework as ESD-TripleStream; to the best of our knowledge, this constitutes the first application of a triple-stream network to time series forecasting:

- We propose a novel deep learning-based framework for C. suppressalis population forecasting. The proposed framework employs a triple-stream network to effectively capture distinct multi-scale patterns, thereby improving prediction accuracy.

- We construct a novel real-world dataset, HNRP-6R. This dataset comprises over two decades (2000–2022) of rice pest monitoring data alongside 13 meteorological factors across six key rice-producing regions in Hunan Province, southern China.

- We conduct extensive experiments on the newly created HNRP-6R dataset, evaluating our framework against several baselines and state-of-the-art methods. The results demonstrate the significant superiority of our proposed framework, achieving state-of-the-art performance in C. suppressalis population forecasting.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset and Preprocessing

2.1.1. Study Area and Data Collection

Study Area. As shown in Figure 1, this research focuses on Hunan Province, China—a major rice-producing region with a subtropical monsoon climate [41], which makes it highly susceptible to seasonal pest outbreaks. Geographically, Hunan spans longitudes to and latitudes to , with an average annual temperature ranging from to . The region experiences hot, humid summers and distinct monsoon seasons, which, combined with its high crop and continuous rice planting cycles, create optimal conditions for pest population surges.

Figure 1.

Locations of study areas: Hunan Province and the six selected regions.

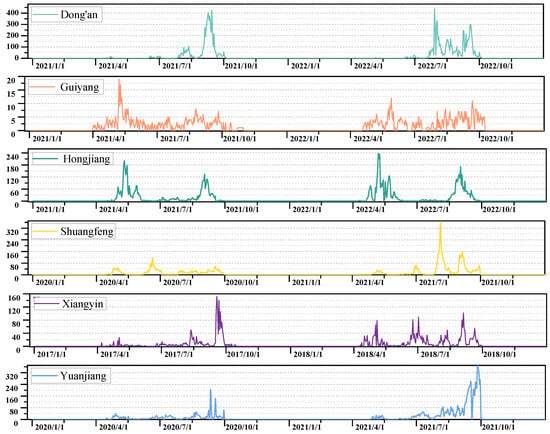

HNRP-6R Dataset. For developing a robust dataset to forecast rice pest populations, we gathered longitudinal pest monitoring data from 93 regions across Hunan Province, sourced via the Hunan Crop Monitoring and Early Warning Information System (https://hn.pestiot.com/#/index/province (accessed on 27 May 2025)). Trained plant protection specialists performed daily data collection using light-trapping devices, with pest counts manually logged at 8:00 AM. Spanning 2000 to 2022, the dataset encompasses 10 key rice pest species (Table 1), including Chilo suppressalis, Rice planthoppers, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis, Sesamia inferens, Tryporyza incertulas, Naranga aenescens Moore, Echinocnemus squameus Billberg, Lissorhoptrus oryzophilus, Orseolia oryzae, and Mythimna separata. Note that the quality of the data is limited due to both subjective and objective factors. Subjectively, it stems from reporting errors made by data collectors. Objectively, these factors include equipment malfunctions of light traps, as well as the light traps’ reliance on a single ultraviolet light source, fixed collection time windows, and the impact of adverse weather conditions (such as heavy rain and strong winds). To guarantee reliability, we filtered out regions with over 40% missing data, ultimately selecting six representative areas—Dong’an, Guiyang, Hongjiang, Shuangfeng, Xiangyin, and Yuanjiang—for our final pest time series dataset. The typical population dynamics of C. suppressalis in these regions are illustrated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Scientific names of ten types of rice pests included in the HNRP-6R dataset and their total statistical quantities.

Figure 2.

Population dynamics of C. suppressalis across five research areas in the HNRP-6R dataset, visualized over a two-year period to improve trend analysis and readability. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis denotes the population size of C. suppressalis (the same below).

Given the significant influence of climatic conditions on rice pest outbreaks, integrating comprehensive meteorological data is vital for enhancing the accuracy of pest population forecasting models. To achieve this, we acquired meteorological records from the China National Meteorological Science Data Center (https://data.cma.cn/), spanning the period from 2000 to 2022. The dataset encompasses 13 key meteorological variables known to influence pest dynamics, including mean daily temperature (°C), mean daily relative humidity (%), mean daily wind speed (m/s), daily sunshine duration (h), daily precipitation (mm), daily evaporation (mm), etc. A detailed list of the selected meteorological factors along with their corresponding units is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The 13 types of meteorological factors included in the HNRP-6R dataset and their corresponding units.

By integrating pest records with corresponding meteorological data, we develop a novel time series dataset for forecasting rice pest population dynamics, named HNRP-6R (HuNan Rice Pest time series from 6 Regions). In this study, given the severe threat of the C. suppressalis to rice production and the critical need for accurate forecasting, we focus on developing accurate predictive models for C. suppressalis outbreaks based on the C. suppressalis relative data in this dataset. Table 3 provides the C. suppressalis statistical overview of the dataset.

Table 3.

Statistics on the population size of C. suppressalis in six research areas within the HNRP-6R dataset. These include the time span of data collection and the total population size of C. suppressalis for each research area.

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

Linear Interpolation. Despite carefully selecting six regions with relatively high-quality data, missing values persist in both pest population and meteorological time series. These gaps arise from inconsistencies in observations, sensor malfunctions, and manual reporting errors. To address data sparsity and maintain temporal continuity, we apply linear interpolation—a widely adopted technique for estimating missing values while preserving the data’s underlying trends. For a missing data point at position x, its interpolated value y is computed using the formula where and are the nearest known data points immediately preceding and following x, and and are their respective y-values. This approach assumes a locally linear relationship between adjacent observations, ensuring seamless transitions in the reconstructed time series.

Outlier Handling. During the collection of C. suppressalis population data, factors such as extreme weather and equipment failures introduce outliers that significantly deviate from the true population dynamics. The Savitzky–Golay Filter (SG filter) is used for preprocessing C. suppressalis data because it effectively smooths data and suppresses noise while preserving high-order statistical features of the signal—making it particularly suitable for time series of biological population dynamics with both periodicity and abrupt change characteristics. The SG filter formula is , where m represents the window half-width, so the window length is set to (meaning 2 data points before and after the target point, plus the target point itself, form a fitting window of 5 points in total); the polynomial order is , and the weighting coefficients are determined via polynomial fitting within the window to achieve outlier removal and minimize signal distortion.

Data Normalization. Time series data often exhibit non-stationary characteristics due to temporal shifts in distribution, which can degrade model performance. To address this challenge, we utilize Reversible Instance Normalization (RevIN) [42], a methodology engineered to boost model adaptability while retaining the original data scale. The normalization workflow comprises two reversible phases. First, each time series instance is standardized through mean subtraction and division by its standard deviation, a process that alleviates the impact of non-stationary fluctuations. Second, post-model inference, predicted outputs undergo rescaling: they are multiplied by the original standard deviation and then the mean is re-added, ensuring that final predictions remain interpretable within the original feature domain. In contrast to traditional normalization approaches, RevIN dynamically adapts to instance-specific distributions, rendering it highly effective for time series forecasting tasks where data distributions evolve over time.

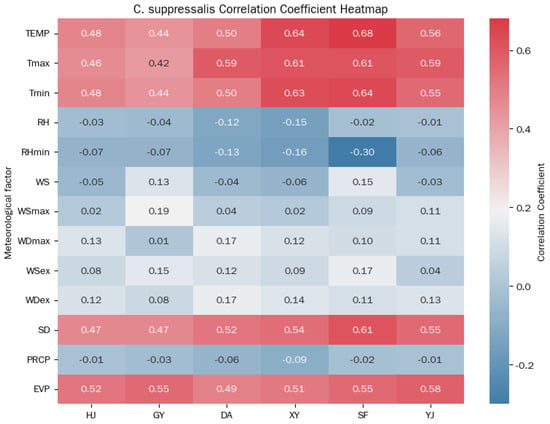

Covariates Selection. Given that the outbreak of C. suppressalis is significantly influenced by meteorological factors, the accurate prediction of C. suppressalis largely depends on the selected covariates. To address this, the study employs a systematic dual-filtering approach that integrates computational statistical analysis with ecological knowledge validation. The selection process begins with calculating the Spearman correlation coefficient (Figure 3), a non-parametric measure specifically chosen for its ability to capture nonlinear dependencies between the C. suppressalis time series and potential covariates. This statistical screening is subsequently complemented by biological rationalization [43], where temperature parameters (TEMP, Tmax, Tmin) are prioritized based on their direct regulatory effects on C. suppressalis developmental rates and reproductive capacity, while evaporation (EVP) is retained as a humidity proxy influencing larval survival. Through this synergistic combination of data-driven analysis and domain expertise, the study identifies five key covariates: average temperature (TEMP), maximum temperature (Tmax), minimum temperature (Tmin), sunshine duration (SD), and evaporation (EVP).

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation heatmap between C. suppressalis population dynamics and meteorological factors. Correlation coefficients range from −1 to 1, with higher absolute values indicating stronger associations.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Problem Formulation

Given an C. suppressalis population time series , c covariate time series and w time-related feature encoding values , our research goal is to construct a time series forecasting framework capable of precisely forecasting the subsequent s-step dynamics of C. suppressalis populations:

Here, and denote the i-th associated covariates and time-related feature values, respectively. Before being input into the model, and are concatenated into a matrix , where is the historical time steps. Time-related features refer to the temporal information recorded alongside C. suppressalis population counts, typically including components such as year, season, month, and day of the week. For example, the timestamp 1 September 2024 can be represented by the categorical features (Autumn, September, Sunday). In practice, these features are numerically encoded as discrete values (e.g., Autumn = 2, September = 9) and then normalized to a common range, such as [−0.5, 0.5]. For instance, the encoding and normalization formula for the “Day Of Month” time-related feature is expressed as . In the following sections, we let denote the matrix of time-related features associated with the historical data. Here, w signifies the number of selected temporal features employed in the analysis.

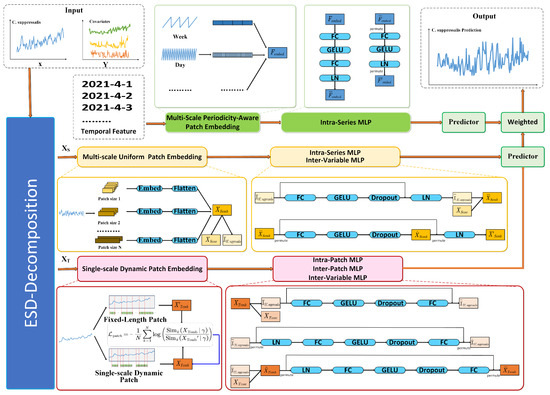

2.2.2. Overview of ESD-TripleStream

The overall architecture of our ESD-TripleStream model, as illustrated in Figure 4, comprises five core modules: an Exponential Smoothing Decomposition (ESD) module, a triple-stream network (including Seasonal Stream, Trend Stream, and Temporal Feature Stream), and a Predictor. The ESD module separates the input C. suppressalis population time series and its covariates into long-term trend components () and high-frequency seasonal components () using exponentially decaying weights, which adaptively emphasize recent data to capture dynamic patterns without padding, addressing the interference between trend and seasonal features in raw time series. The triple-stream network processes these decomposed components and temporal features separately: the Seasonal Stream handles the nonlinear, multi-periodic with a Multi-Scale Uniform Patch Embedding (MUP) module to capture multi-frequency periodic patterns via patches of varying lengths, integrating Intra-Series MLP (modeling within-C. suppressalis temporal dependencies) and Inter-Variable MLP (mining C. suppressalis-covariate interactions); the Trend Stream processes the weakly linear through a Single-Scale Dynamic Patch Embedding (SDP) module that adaptively adjusts patch boundaries based on local trends, using Intra-Patch MLP (short-term trends), Inter-Patch MLP (long-term trends), and Inter-Variable MLP (cross-variable interactions) to model hierarchical dependencies; the Temporal Feature Stream incorporates time-related features (e.g., season, month) via a Multi-Scale Periodicity-Aware Patch Embedding (MPPE) module, which designs exclusive patch lengths for different temporal attributes to capture periodic patterns, with an Intra-Series MLP enhancing temporal feature representation. The Predictor adopts a direct multi-step strategy, integrating outputs from the three streams via weighted summation and using linear projections to generate future C. suppressalis population predictions, optimized end-to-end to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term trends, collectively addressing nonlinearity, multi-scale periodicity, and temporal dependency in C. suppressalis forecasting.

Figure 4.

Framework of the ESD-TripleStream model: It integrates the Exponential Smoothing Decomposition (ESD) module (separating trend and seasonal components), a triple-stream network (Seasonal Stream, Trend Stream, and Temporal Feature Stream) and a Predictor module (integrating streams to forecast C. suppressalis population).

2.2.3. Trend-Seasonal Decomposition

The C. suppressalis population is influenced by multiple factors such as temperature, precipitation, and crops, and its time series often contains both significant seasonal cycles and long-term trends. The trend component reveals the long-term change direction of C. suppressalis populations, often exhibiting weakly non-linear characteristics, while the seasonal component focuses on capturing periodic biological rhythms and tends to show non-linear features. Due to the non-linear and non-stationary nature of C. suppressalis population data, traditional single models struggle to simultaneously characterize the smooth evolution of trends and the high-frequency characteristics of seasonal fluctuations. Decomposing the C. suppressalis and its covariate sequences enables the model to design targeted learning mechanisms for the characteristics of these two components, thereby more accurately modeling the dynamics of the C. suppressalis population and improving the accuracy of predicting future outbreak periods and population peaks.

Inspired by xPatch [38], we adopt the Exponential Smoothing Decomposition (ESD) module, a time-series processing technique that leverages exponentially decaying weights to separate trend and seasonality components. Unlike traditional moving-average methods [36], ESD assigns higher weights to more recent data points, enabling faster adaptation to trend changes without requiring padding operations.

For the C. suppressalis and its covariate sequence X, the ESD process is formally defined as

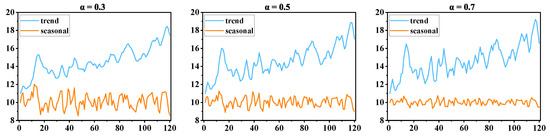

where (0 < < 1) is the smoothing factor controlling the weight decay. By progressing from to , ESD enhances the control over trend and seasonality components, making it more suitable for processing C. suppressalis data with dynamic and evolving patterns, and ensuring more precise feature extraction. The resulting represents the long-term trend, while represents the high-frequency seasonal fluctuations. Figure 5 shows an example of ESD decomposition.

Figure 5.

Example of ESD decomposition with = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7 on a 120-length sample from the GY dataset.

2.2.4. Seasonal Stream

The decomposed seasonal component exhibits nonlinear and multi-periodic characteristics; therefore, our MUP module captures multi-frequency periodic features through patches of different lengths, while Intra-Series MLP models nonlinear dependencies within the C. suppressalis series and Inter-Variable MLP mines cross-variable interactions between C. suppressalis and covariables. The combination of these components enables the precise capture of complex multi-scale temporal relationships and variable associations in seasonal components, enhancing the modeling capability for nonlinear patterns and prediction generalization.

Multi-Scale Uniform Patch Embedding. A single-scale patch fails to effectively identify periodic features at different frequencies, leading to inaccurate or incomplete local feature capture by the model. Inspired by PatchMLP [44], we adopted the MUP (Multi-Scale Uniform Patch Embedding) module. By using patches of different lengths, it can not only capture local high-frequency fluctuations with shorter patches but also explore medium-term seasonal and periodic trends with longer patches. This enables the model to flexibly learn representative features across different time spans, thereby more accurately capturing the complex multi-scale temporal relationships in the seasonal component and enhancing the predictive accuracy and the model’s generalization ability to seasonal patterns.

Specifically, we design a set of different scales (such as ) to perform non-overlapping segmentation on the input sequence . Through the unfold operation, the sequence is divided into patches according to each scale , forming . Then, a single linear layer is used to map it to low-dimensional features (where , K is the number of scales of the patch set P to achieve dimension alignment, and is the final embedding dimension). Finally, the outputs of all scales are flattened and concatenated to obtain the embedding representation that fuses multi-scale information.

Intra-Series MLP. For the feature matrix , we design an Intra-Series MLP module to specifically extract the temporal dependencies of the target C. suppressalis variable. By isolating and focusing on the C. suppressalis variable, this module avoids interference from irrelevant covariates, significantly enhancing the model’s predictive capability for the target variable.

Specifically, we first isolate the C. suppressalis variable from the embedding matrix: Subsequently, the Intra-Series MLP performs nonlinear transformations on the C. suppressalis variable, capturing complex temporal patterns through an MLP architecture with residual connections and layer normalization:

where Linear is a fully connected layer, GELU is an activation function, and LayerNorm maintains feature distribution stability. The processed C. suppressalis feature is re-concatenated with the unprocessed covariate feature to form an augmented embedding matrix: where denotes the enhanced embedding matrix.

Inter-Variable MLP. The Inter-Variable MLP is designed to model the interdependencies between the C. suppressalis variable and covariates. Specifically, the input matrix first undergoes a dimension transposition operation to swap the variable and feature dimensions. The transposed matrix is processed through a fully connected network, then transposed back to the original dimension. Residual connections with the original input are applied to preserve the initial information, and layer normalization is used to stabilize the feature distribution. The overall process can be expressed as

The Inter-Variable MLP effectively captures the interactive influences between the C. suppressalis variable and covariates through shared linear transformations in the feature dimension. Residual connections ensure that the original temporal patterns are not disrupted, while layer normalization enhances training stability and model generalization capability.

2.2.5. Trend Stream

The decomposed trend component exhibits relatively smooth weakly linear characteristics, with a focus on long-term dependencies and local continuity. Therefore, we employ the Single-Scale Dynamic Patch Embedding (SDP) module, which adaptively and dynamically adjusts patch sizes according to the local features of the trend component. This approach preserves the inherent weak linear structure while precisely capturing the gradual information between adjacent patches. Additionally, Intra-Patch MLP and Inter-Patch MLP are used to model the short-term and long-term trends in C. suppressalis, respectively, while Inter-Variable MLP mines the cross-variable interactions between C. suppressalis trend components and covariates.

Single-Scale Dynamic Patch Embedding. Fixed single-scale patch embedding operations [45] fail to adapt to the scale variations of the trend component across different time periods, prone to causing a loss of patch boundary information. In contrast, Multi-Scale Patch Embedding operations increase computational complexity and may introduce redundancy, as the weakly linear nature of the trend component lacks multi-frequency periodicity. Inspired by HDMixer [46], we propose the SDP (Single-Scale Dynamic Patch Embedding) module, which adaptively adjusts patch lengths according to the local features of the trend component. This approach not only preserves complete trend boundary information but also mitigates semantic incoherence caused by fixed patches through dynamic patch length extension, avoiding fragmentation of key trend features.

Given the C. suppressalis trend component , the Single-Scale Dynamic Patching strategy adaptively segments into N patches with flexible lengths, preserving critical temporal patterns while ensuring computational efficiency. For each patch, a fixed number of time points is sampled via bilinear interpolation, followed by learnable linear projection to generate patch-level embeddings .

Specifically, for the i-th patch, its central position is dynamically adjusted by a learnable offset , enabling alignment with key temporal features. The left and right boundaries of the patch are adaptively extended as

where denotes the default number of sampled time steps per patch, and , represent learnable expansion factors. To maintain a fixed number of values per patch, the expanded region is resampled using bilinear interpolation:

where denotes the sampled value at fractional time step i, and is the original value at step j. This ensures smooth transitions and preserves differentiability.

To optimize the parameters based on input characteristics, a patch diversity loss is introduced. This loss encourages informative and diverse patch representations by minimizing redundancy. Given , let denote its dynamic patches and denote fixed-length patches. The loss is defined as

where measures patch similarity, is a threshold, and computes the maximum absolute difference between patches. Minimizing this loss ensures that the model learns representations tailored to the C. suppressalis trend component’s structure.

Intra-Patch MLP. Intra-Patch MLP is designed to capture the short-term trends of the C. suppressalis trend component within each patch. For the embedding matrix , the patch-level embedding of the C. suppressalis variable, , is first isolated from it. Subsequently, we adopt a two-layer fully connected network combined with the GELU activation function, dropout regularization, and residual connections to model the trend features within each patch of :

where are weight matrices.

Inter-Patch MLP. This module models the long-term trends of the C. suppressalis trend component across different patches. The output from the Intra-Patch MLP, , is first transposed to yield a new tensor, whose dimension is , facilitating the subsequent modeling of long-term dependencies in the C. suppressalis trend component. Next, the following operations are applied to :

where are weight matrices, and LN denotes layer normalization. The two Per denote the permutation operation and the operation of transposing back to the original dimensions, respectively, i.e., . This module, while capturing cross-patch long-term dependencies, complements the intra-patch MLP’s ability to capture short-term trends, thereby achieving the joint modeling of long-and-short-term trends.

Inter-Variable MLP. This module aims to model the interaction between the C. suppressalis trend component and its covariates. First, the output of the Inter-Patch MLP module, , is reintegrated into the original embedding matrix to obtain a new matrix . After performing a transpose operation on its dimensions, we obtain a new tensor, whose dimension is , which facilitates cross-variable interaction modeling across the variable dimension. Subsequently, the following operations are performed:

where are weight matrices for cross-variable interaction, and the two Per denote the permutation operation and the operation of transposing back to the original dimensions, respectively, i.e., . Finally, we merge the N and dimensions of the matrix and remap it back to dimensions through a linear layer, resulting in the final output of this module: .

2.2.6. Temporal Feature Stream

As an agricultural pest, the population dynamics of the C. suppressalis exhibit strong temporal dependencies. Time-related features serve as critical carriers for characterizing these dependencies. Therefore, we can employ learnable models to capture the relationship between C. suppressalis’s time-related features and observed population densities. For a specific time point i, its time-related features are denoted as (such as season, month, day of the week, etc., totaling w types of features), and the corresponding C. suppressalis observation is . It is assumed that follows a conditional distribution , i.e., C. suppressalis observations depend on time-related features. For example, the C. suppressalis population count on 1 September is correlated with the two time-related features of “September” and “1st”. We employ a learnable generative model to approximate this distribution:

where the input time-related feature matrix is , and, since we only need to predict the C. suppressalis, the output observation matrix is , representing future predictions based on C. suppressalis historical time-related observations. Due to the strong linear characteristics exhibited by time-related features after encoding, consists of the Multi-Scale Periodicity-Aware Patch Embedding (MPPE) and the Intra-Series MLP. These two modules are introduced in detail next.

Multi-Scale Periodicity-Aware Patch Embedding. The core innovation of this module lies in designing exclusive patch lengths for the periodic characteristics of different time-related features, enabling the more precise capture of periodic patterns at different time scales. This design allows the model to better understand and utilize the implicit information in time-related features, providing richer and more accurate feature representations for C. suppressalis prediction. The MPPE module can be represented as

The time feature matrix is , where denotes the number of time steps and w represents the count of time features. Additionally, stands for a multi-scale periodicity-aware feature-embedding matrix. Specifically, for the , we transpose it to . This transposition ensures that each row corresponds to an independent time feature, facilitating the separate processing of each time feature. For each time feature (), a dedicated patch length is designed according to its inherent periodicity. For instance, the patch length for “Day Of Month” is set to 30. Then, is divided into non-overlapping patches with a step size of . The j-th patch is denoted as . This ensures that each patch captures a complete periodic unit and avoids information mixing across cycles. For each patch , it is embedded into the model’s feature space through a two-stage linear transformation. First, the patch of length is projected into a subspace via a linear layer, changing its dimension to :

This step captures the temporal dependencies within the patch through dimensional transformation, enhancing the feature representation ability. For example, when (Day Of Month), , and , each patch is expanded from 30 dimensions to 128 dimensions. Subsequently, the embedded patches of the same feature are concatenated and then passed through a second-layer linear layer to restore the full model dimension :

Here, . This process integrates all patch information of the feature while preserving the temporal order. Finally, the embeddings of all w time features are concatenated along the feature dimension to form a unified representation : .

Intra-Series MLP. The core objective of this module is to perform non-linear transformations on the embedding vectors of each time feature through a Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to capture the complex temporal dependencies within individual time features, thereby enhancing the semantic representation capability of each time feature. For the input feature matrix , the following operations are performed:

where and are fully connected layers. LN stands for layer normalization. Subsequently, a dimension transposition operation is performed on to facilitate linear combination in the feature dimension. This process is represented as mapping the features to the target prediction dimension through a linear layer:

where , Per denotes the dimension permutation operation, , and LN stands for layer normalization.

2.2.7. Predictor

We adopt direct multi-step forecasting, where the model outputs results for multiple future time points at once. This approach avoids the error accumulation issues caused by single-step forecasting or iterative multi-step forecasting [36]. First, we add the output of the seasonal Stream module and the output of the trend Stream module to obtain . Then, following common practice, we employ two separate linear predictors that take and the temporal feature Stream output as inputs, respectively generating the predicted sequences and , and, finally, perform a weighted summation to generate the final prediction result:

where denotes the predicted value of C. suppressalis, and serves as a tunable parameter that calibrates the contributions from the respective modules.

To quantify the deviation between the predicted values and the ground truth, we adopt the mean squared error (MSE) loss function:

Ultimately, the aggregate loss function is formulated as the combination of the prediction loss and the patch reconstruction loss :

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Settings

Datasets. We conducted comprehensive experiments on the self-constructed HNRP-6R dataset. For training and evaluation purposes, the dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets at ratios of , , and respectively. To ensure experiment reproducibility, the data was randomly split using a fixed random seed.

Implementation Details. To ensure equitable comparisons, we uniformly configure hyperparameters across all models. The patch length and stride are both fixed at 30; the embedding dimension is set to D = 512 and FFN dimension is set to 1024. The encoder consists of L = 2 layers, and a dropout rate of 0.1 is applied to prevent overfitting. Each model undergoes training for a maximum of 30 epochs, incorporating early stopping to balance performance and computational efficiency. Specifically, training halts if the validation loss shows no improvement for five consecutive epochs (patience = 5). Moreover, the learning rate is and batch size is 128. All experimental setups are strictly consistent to ensure reproducibility, with identical configurations maintained across all model runs.

Experimental Environment. All algorithms are implemented with PyTorch 2.0.1 [47] on a workstation with Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-8750H CPU, 8·GB memory, and 1 NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050 Ti GPU.

Baseline Methods. We compare our method with eight state-of-the-art baseline methods, including two transformer-based methods—TimeXer [48], iTransformer [49]; one LSTM-based method—P-sLSTM [50]; two linear-based models—Timelinear [39], DLinear [36]; two MLP-based models—PatchMLP [44], HDMixer [46]; and one MLP-based and CNN-based model—xPatch [38]. The brief introduction of them is listed here:

- TimeXer (NeurIPS’24) innovatively uses a hybrid patch- and variable-level representation. It captures endogenous variables’ temporal dependencies via self-attention and exogenous variables’ global trends through cross-attention.

- iTransformer (ICLR’24) features series-wise representations. It treats each variable as a “variate token” and captures variate correlations via the attention mechanism.

- P-sLSTM (AAAI’25) enhances sLSTM with patching and channel independence, addressing traditional LSTM’s short memory limitations to improve medium-term time series forecasting performance.

- TimeLinear (arXiv’24) introduces the Time Stamp Forecaster (TimeSter) module to encode time-related features (e.g., seasons, hours, weekdays) and integrates them with a linear model for enhanced medium-term forecasting.

- Dlinear (AAAI’23) splits the time series into a trend series and a remainder series. Subsequently, it utilizes two single-layer linear networks to separately model these two sequences.

- PatchMLP (AAAI’25) innovatively employs Multi-Scale Patch Embedding to capture multiscale relationships in sequences, decomposes latent vectors into trend and seasonal components, processes them separately, and enhances variable interactions to improve forecasting accuracy.

- HDMixer (AAAI’24) devises a length-extensible patch module that module serves to enrich the boundary information of patches. Moreover, it makes use of the Hierarchical Dependency Explore module to effectively model hierarchical interactions.

- xPatch (AAAI’25) employs EMA for seasonal-trend decomposition, separates time-series components via an MLP–CNN dual-flow architecture with patching and channel independence, and introduces arctangent loss and sigmoid learning rate schemes to optimize training and boost performance.

Evaluation Protocols. To quantify prediction errors, we use Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). MSE penalizes large errors more due to squaring, making it sensitive to outliers, while MAE sums errors linearly and treats all deviations equally. Both metrics are widely used in regression tasks for their interpretability and effectiveness in measuring absolute errors, with formulas provided below:

where represents the predicted values, denotes the ground truth values, and n is the number of samples. A lower MSE or MAE indicates better predictive accuracy. MSE amplifies large errors due to squaring, making it sensitive to outliers, while MAE provides a linear measure of average error magnitude.

3.2. Results and Analysis

3.2.1. Performance Comparison

We compare and evaluate our proposed method against baseline approaches in both short-term and medium-term forecasting tasks, as these two tasks are critical for predicting and managing C. suppressalis outbreaks. Short-term forecasting enables timely pest control measures to reduce potential yield losses, while medium-term forecasting helps growers to understand medium-term trends in pest populations to facilitate proactive strategy development. An ideal forecasting model should perform well in both quick response and medium-term planning, so evaluating performance across these two tasks provides a comprehensive assessment of the proposed method’s overall effectiveness. The comparative results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, where we report evaluation metrics such as MSE and MAE. The best-performing results are bolded, and the second-best results are underlined to facilitate a clear comparison of different methods’ performances.

Table 4.

Short-term forecasting results. The input sequence length configured as and the forecasting horizon . The best-performing results are highlighted in bold, and the second-best results are underlined (the same below).

Table 5.

Medium-term forecasting results. The input length of all baselines is set to 240, and the forecasting horizons are set respectively.

Short-Term Forecasting.Table 4 illustrates a detailed comparison of 30-day short-term forecasting performance across six regions. Our model demonstrates top-tier performance, achieving 48 first-place and 10 second-place rankings across 60 evaluated scenarios. The MSE and MAE of our model decreased by 31.8% and 26.55% compared to PatchMLP, and by 31.17% and 25.66% compared to xPatch. The main reasons are as follows: while both PatchMLP and xPatch perform seasonal-trend decomposition, PatchMLP fails to handle seasonal and trend components differently, instead using uniform multi-scale embedding and MLP operations. This approach prevents it from accurately capturing the true patterns in the two data types. xPatch, although distinguishing between trend and seasonal components, does not account for cross-variable correlations. Additionally, both models overlook modeling temporal information in their predictions, which our model explicitly incorporates through customized temporal encoding and integration, leading to significant performance improvements. In addition, compared with the transformer-based model TimeXer, our model achieves a 14.43% decrease in MSE and 9.8% decrease in MAE. This is primarily because TimeXer does not separate trend and seasonal components, causing the two to interfere with each other in unified embedding, which makes it difficult for the model to accurately distinguish between trend directions and fluctuation details. Additionally, due to the lack of any explicit encoding of temporal positional features such as dates and weeks, TimeXer fails to leverage temporal information to enhance prediction performance. Notably, compared with TimeLinear, our model achieves a 20.60% decrease in MSE and 14.85% decrease in MAE. The main reasons lie in the fact that, although TimeLinear encodes time-related features, it fails to design dedicated embedding scales for the inherent periods of different temporal attributes. Instead, it employs generic convolution and linear projection operations, leading to the incomplete fitting of periodic patterns in temporal information and reduced sensitivity to temporal positions. Additionally, TimeLinear uses a simple linear model that cannot accurately capture the complex nonlinear relationships in the data.

Medium-Term Forecasting. Table 5 shows that our model demonstrates superior performance in medium-term forecasting (45-, 60-, 75-, and 90-day horizons), achieving 33 first-place and 14 second-place rankings across 48 experimental settings. Compared with the most powerful transformer-based model TimeXer and the LSTM-based model P-sLSTM, our model reduces MSE by 8.83% and 17.5%, and MAE by 7.68% and 24.59%. In contrast, versus PatchMLP, our model achieves significant performance improvements, with MSE and MAE decreasing by 31.18% and 26.87%, respectively. Notably, as the forecasting length increases, the prediction performance of our model on most datasets improves, primarily attributed to the time-encoding prediction component that provides reliable time-reference information for medium-sequence forecasting.

3.2.2. Qualitative Results

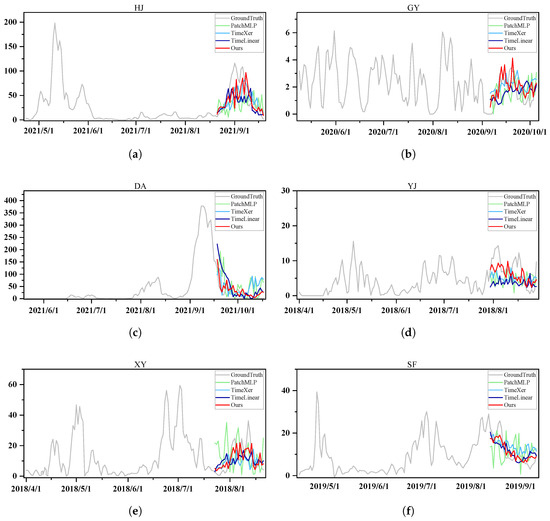

Figure 6 shows the prediction results for six regions, where the model uses 120 days of historical data as input to forecast the next 30 days. We compare our method with three state-of-the-art baseline models: TimeXer, PatchMLP, and TimeLinear. The results indicate that PatchMLP’s predictions exhibit significant fluctuations and instability, primarily because the trend and seasonal components in C. suppressalis data inherently possess distinct characteristics, yet PatchMLP applies identical modeling to both. This prevents the model from capturing true long-term trends and precise seasonal variations, leading to large-scale, irregular fluctuations in predictions. Secondly, although TimeLinear utilizes time-related features for forecasting, it relies on a simple linear model that fails to capture the complex seasonal and trend relationships in C. suppressalis data and does not decompose the data. This results in TimeLinear’s inability to accurately identify seasonal fluctuation patterns or characterize trend changes, leading to poor prediction performance. Additionally, the trend and seasonal components in C. suppressalis data have different temporal scale characteristics. TimeXer divides continuous C. suppressalis sequences into fixed-length patches of a single scale, which may disrupt the natural continuity of trends and seasons at patch boundaries, causing incoherent semantic information and making it difficult for the model to capture complete periodic patterns. Notably, the attention mechanism in TimeXer, which calculates correlations between different sequence positions to capture key information, struggles to adapt to both the long-distance dependencies required for trend modeling and the short-distance periodic repetitions needed for seasonal modeling due to fixed patch lengths. Directly applying attention to patches mixing both features confuses the importance of different characteristics, leaving TimeXer unable to accurately model the medium-term evolution of trends or replicate seasonal cycles, resulting in deviations from real data—especially at critical points of trend shifts or significant seasonal fluctuations.

Figure 6.

Visualization results for six research regions. Specifically, Panel (a) shows the experimental results of the HJ region; Panel (b) shows those of the GY region; Panel (c) shows those of the DA region; Panel (d) shows those of the YJ region; Panel (e) shows those of the XY region; and Panel (f) shows those of the SF region. The input length is set to , and the prediction horizon is . The vertical axis represents the observed C. suppressalis population.

In contrast, our model demonstrates superior visualization performance by designing differentiated patch embedding and MLP strategies tailored to the distinct properties of C. suppressalis data’s trend, seasonal, and time-related features. This enables precise modeling of linear trends, nonlinear seasonal fluctuations, and temporal periodic patterns in C. suppressalis population dynamics, fundamentally avoiding the flaws of other models in feature separation, scale adaptation, and nonlinear processing. As a result, our model’s prediction curves closely match the complex variations in real data, showcasing excellent visualization effectiveness.

3.2.3. Ablation Analysis

To comprehensively and methodically assess the impact of each proposed component, we carry out ablation studies across six distinct regions within a short-term (30-day) forecasting context. In order to gauge the models’ resilience and adaptability across various temporal scales, we test them under a range of input sequence lengths, spanning from 120 to 600. More precisely, we formulate six different ablation model variants. Through these variants, we aim to systematically dissect and understand the specific role that each individual component plays in the overall model performance. This approach allows us to gain in-depth insights into the contribution of every part of the proposed model structure:

- w/o TFS: Remove the Temporal Feature module means that the model does not consider time-related information at all during the prediction process.

- w/o SS: Remove the Seasonal Stream module and replace it with the Trend Stream module.

- w/o TS: Remove the Trend Stream module and replace it with the Seasonal Stream module.

- w/o ESD-S: Remove the ESD module, i.e., do not decompose the original sequence into trend and seasonal components, and use the Seasonal Stream module to process the original sequence.

- w/o ESD-T: Remove the ESD module, i.e., do not decompose the original sequence into trend and seasonal components, and use the Trend Stream module to process the original sequence.

- w/o TFS-Mod: Replace the modules in the temporal feature stream with two nonlinear hidden layers, a 1D convolutional layer, and a linear projection layer from the TimeLinear module.

Table 6 displays the outcomes of our ablation experiments, which fully confirm the subsequent conclusions.

Table 6.

The forecasting results of ablation studies. The input sequence length is configured as and the forecasting horizon .

Removing the temporal feature module (w/o TFS) led to an average increase of 13.07% in MSE and 11.53% in MAE across six regional datasets. This highlights the critical role of time information encoding in capturing periodic patterns of C. suppressalis populations. The absence of this module prevents the model from identifying temporal dimensional features (e.g., day/month positions), causing periodic prediction deviations.

Replacing the Seasonal Stream module (w/o SS) increased MSE/MAE by 4.25%/4.02%, confirming that Multi-Scale Uniform Patch Embedding for seasonal components is essential for extracting nonlinear short-term fluctuations and multi-frequency features. Uniform single-scale processing for trends fails to capture complex seasonal patterns, amplifying prediction errors.

Replacing the Trend Stream module (w/o TS) caused MSE/MAE to rise by 6.86%/4.85%, validating the necessity of dynamic patch splitting embedding for trend components to capture long-term linear dependencies. Multi-scale embedding fragments trends into local fluctuations, misleading the model’s global trend judgment and introducing redundant local analysis errors.

Removing the seasonal decomposition module (w/o ESD-S) and directly applying multi-scale embedding to raw sequences increased MSE/MAE by 8.78%/7.02%. This indicates that separating trend and seasonal components via EMA decomposition is prerequisite for targeted modeling. Mixed processing misinterprets linear trends as nonlinear oscillations, disrupting feature independence between the two components.

Skipping trend decomposition (w/o ESD-T) and using uniform dynamic patch splitting for raw sequences led to MSE/MAE increases of 3.62%/2.79%. The lack of decomposition weakens global trend consistency and local seasonal multi-frequency feature extraction, reducing the model’s ability to distinguish between the two components.

Replacing the temporal feature module structure (w/o TFS-Mod) caused MSE/MAE to rise by 1.93%/2.03%. This demonstrates that designing dedicated embedding scales for temporal attributes outperforms generic convolutional operations in capturing fine-grained temporal position features, avoiding incomplete periodic pattern fitting and reduced temporal sensitivity.

3.2.4. Generalization Analysis

To evaluate the generalization ability of our model, we perform an extra experiment focusing on predicting the population dynamics of N. lugens, a major agricultural pest that poses a significant threat to rice production. N. lugens inflicts crop damage through multiple pathways, such as sap-sucking, viral transmission, and oviposition, which can result in severe plant lodging and even complete crop failure. Although both N. lugens and C. suppressalis cause substantial yield losses, their ecological behaviors and population dynamics exhibit notable differences. N. lugens displays migratory patterns influenced by seasonal climatic conditions, with population surges primarily driven by external environmental factors. In contrast, C. suppressalis follows a relatively stable life cycle that relies more heavily on crop growth stages. Given these fundamental differences, evaluating the reverse forecasting ability of our model serves as a rigorous test of its capacity to generalize across pest species with diverse temporal dynamics.

For a thorough evaluation, this experiment utilizes datasets from four regions—HJ, YJ, DA, and GY—which cover diverse geographical environments. The covariates employed in N. lugens forecasting (TEMP, Tmax, Tmin, SD, and EVP) are set with the same sequence length as those in the C. suppressalis forecasting task, ensuring a consistent experimental framework. Model performance will be measured using MSE and MAE metrics to determine whether it maintains high predictive accuracy despite the different behavioral patterns of N. lugens. We conduct both quantitative and qualitative analyses of the results, providing critical insights into the model’s applicability in real-world scenarios that demand accurate forecasting of multiple pest species with varying ecological.

Quantitative Results.Table 7 displays the 30-day short-term forecasting results of our model when compared against eight advanced baseline models. The input sequence length ranges between 120 and 600 time steps, adhering to the same experimental configurations as previous setups. Experimental outcomes indicate that our model achieves the top performance in 30 out of 40 evaluation cases, while ranking second in the remaining 8 instances. These findings strongly highlight the model’s exceptional forecasting proficiency across diverse input scales. Compared with the state-of-the-art transformer-based model TimeXer, MLP-based model PatchMLP, and LSTM-based model P-sLSTM, the MSE of our model decreased by 2.4%, 42%, and 22.56%, respectively, and the MAE decreased by 4.07%, 33.43%, and 33.39%, respectively. Our model not only maintains high predictive accuracy when applied to pest species with unique ecological behaviors but also outperforms specialized models designed for sequential data. These results underscore its applicability in multi-species forecasting scenarios that demand robust generalization capabilities, demonstrating its ability to excel across diverse pest dynamics and modeling paradigms.

Table 7.

Prediction outcomes for the N. lugens population are presented, with the input sequence length configured as and the forecasting horizon set to .

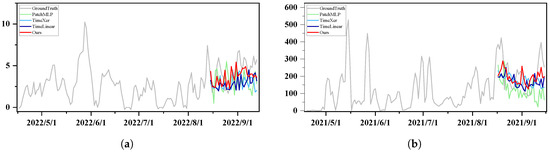

Qualitative Results. To provide an intuitive assessment of the prediction performance, we present visualizations of the N. lugens population dynamics in GY in 2022 and HJ in 2021. Figure 7 shows the prediction curves of our model, TimeXer, PatchMLP, and TimeLinear, as well as the actual data. The left subplot corresponds to GY, and the right subplot represents HJ. The results indicate that, compared with other models, our model more accurately captures the cyclical and seasonal trends of the N. lugens population. These findings further confirm the universality of our model in predicting pest population dynamics under different ecological conditions.

Figure 7.

Visualization of prediction results for GY (a) and HJ (b). GY predicts the next month based on data from mid-April to mid-August 2022, while HJ predicts the next month based on data from mid-April to mid-August 2021. The vertical axis represents the observed N. lugens population.

3.2.5. Model Limitations

Although the proposed ESD-TripleStream model has achieved state-of-the-art performance in forecasting the populations of C. suppressalis and N. lugens, it still has inherent limitations regarding climate sensitivity and variability that warrant further discussion.

Limitations in Climate Sensitivity. The model’s reliance on historical meteorological data (e.g., average temperature, precipitation) results in insufficient sensitivity to abnormal events of an extreme climate nature. For instance, abnormal weather conditions such as consecutive days with temperatures exceeding 35 °C and short-duration heavy rainfall directly disrupt the developmental cycle of C. suppressalis (e.g., larval survival rate, pupation success rate). However, such events are not given special weight consideration in the current model framework.

Limitations in Climate Variability. The HNRP-6R dataset is derived from the subtropical monsoon climate region of Hunan Province. Although data from five regions were used in the experiments, the regional scope is too narrow on a global scale. This means that the model is more optimized for the climate dynamics specific to this region. When the model is extended to areas with vastly different climate types (e.g., tropical rainforests, arid regions), the interaction patterns between climate and pests in these areas differ significantly from those in Hunan, which may lead to a decline in the model’s performance.

These limitations indicate that future research needs to improve the model’s adaptability to complex climate conditions. Examples of such improvements include integrating indicators of extreme climate events, incorporating climate change projection data, and designing region-adaptive modules to address climate variability across different geographical environments.

4. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel multi-stream framework for C. suppressalis population dynamics forecasting in agriculture, which addresses the limitations in existing time series prediction approaches, often omitting the further decomposability and the timestamp information of the time series. During our evaluation, the proposed framework outperformed several baselines and reported excellent performance in C. suppressalis population dynamics forecasting. The proposed forecasting model enables farmers to carry out precise control before the pests cause irreversible damage, thereby minimizing yield loss directly. It is also helpful in effectively preventing arbitrary pesticide use, reducing agricultural non-point source pollution at its source, and is a fundamental step towards developing green agriculture. A novel dataset, which includes rice pest monitoring data from the past two decades (2000–2022) alongside 13 meteorological factors across six key rice-producing regions in Hunan Province, southern China, is constructed for our experimental evaluation. This dataset will serve as a valuable asset for advancing research in predicting rice pest outbreaks.

In our future work, we plan to integrate more fine-grained environmental features (e.g., soil conditions, pesticide application records) and extend the proposed framework to model multi-pest interactions. Furthermore, we also consider integrating real-time monitoring data and developing interpretable prediction mechanisms. These enhancements are expected to increase the model’s practicality, thereby contributing to precision agriculture and sustainable crop protection strategies.

Author Contributions

C.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing; Z.P.: Conceptualization, validation, visualization; L.P.: Resources; Y.L.: Validation, investigation, data curation; C.Z.: Resources; L.Z. (Lei Zhu): Writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition; S.T.: Funding acquisition; L.Z. (Ling Zou): Writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the Hunan Provincial Key Research and Development Program Project under Grant 2023NK2011, the Scientific Research Fund of Hunan Provincial Education Department under Grant 23A0168, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62202163, Grant 62472161 and Grant 62372150, the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province under Grant 2023JJ30169 and 2022JJ30231, the Teaching Reform Research Program of Regular Higher Education Institutions of Hunan Province under Grant HNJG-20230396, and the Yuelu Mountain Laboratory Seed Industry Special Project under Grant YLS-2025-ZY04016.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Gnanamanickam, S.S. Rice and its importance to human life. In Biological Control of Rice Diseases; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tzin, V.; Romeis, J.; Peng, Y.; Li, Y. Combined transcriptome and metabolome analyses to understand the dynamic responses of rice plants to attack by the rice stem borer Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E. Strategies for enhanced crop resistance to insect pests. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 637–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.B.; Chen, M.; Bentur, J.S.; Heong, K.L.; Ye, G. Bt rice in Asia: Potential benefits, impact, and sustainability. In Integration of Insect-Resistant Genetically Modified Crops Within IPM Programs; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Hou, M.; Han, L.; Liu, Y. Research progress in host selection and underlying mechanisms, and factors affecting population dynamics of Chilo suppressalis. Plant Prot. 2008, 34, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Li, F.; Yu, K.L.; Chen, J.M. The morphology and an improvement of breeding efficiency of larval Chilo suppressalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Entomol. News 2025, 132, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Liu, S.H.; Li, H.J.; Danso Ofori, A.; Yi, X.Q.; Zheng, A.P. Defense strategies of rice in response to the attack of the herbivorous insect, Chilo suppressalis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, P.; Krishnamurthy, K.N.; Bakshi, B. Prediction of crop yield and pest-disease infestation. In AI, Edge and IoT-Based Smart Agriculture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 375–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kopton, J.; de Bruin, S.; Schulz, D.; Luedeling, E. Combining spatio-temporal pest risk prediction and decision theory to improve pest management in smallholder agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, X.; Qin, N.N.; Xu, K.F.; Zeng, R.S.; Liu, J.; Song, Y.Y. Nitrogen supply alters rice defense against the striped stem borer Chilo suppressalis. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 691292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Qiao, S.T.; Guo, F.R.; Xie, Y.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, S.Q.; Zhou, L.Q.; He, L.F.; et al. The evolution and mechanisms of multiple-insecticide resistance in rice stem borer, Chilo suppressalis Walker (Lepidoptera: Crambidae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 26475–26490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yuan, Z.C.; Yi, Z.Q.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Boussaid, F.; Bennamoun, M.; Zhang, S.C. Information bottleneck-guided KNN contrastive hashing for unsupervised cross-modal retrieval. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 329, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.J.; Kim, K.H. Determining the minimum data size for the development of artificial neural network-based prediction models for rice pests in Korea. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gu, C.G.; Yang, H.J.; Weng, T.F. Prediction of spatial distribution of invasive alien pests in two-dimensional systems based on a discrete time model. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 143, 105673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.A.; Salifu, D.; Mwalili, S.; Dubois, T.; Collins, R.; Tonnang, H.E.Z. An expert system for insect pest population dynamics prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.J.; Gomez, M.M.; Munch, S.B. Empirical dynamic modeling for prediction and control of pest populations. Ecol. Model. 2025, 504, 111081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushboo, S.S.; Gupta, V.; Pandit, D. Forewarning of stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis) of wheat in Jammu plains. Indian Phytopathol. 2023, 76, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, R.B.; Liu, D.Y.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.C. Textual semantics enhancement adversarial hashing for cross-modal retrieval. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 317, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Li, T. Pest and disease prediction and management for sugarcane using a hybrid autoregressive integrated moving average—a long short-term memory model. Agriculture 2025, 15, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narava, R.; DV, S.R.K.; Jaba, J.; P, A.K.; GV, R.R.; V, S.R.; Mishra, S.P.; Kukanur, V. Development of temporal model for forecasting of Helicoverpa armigera (Noctuidae: Lepidopetra) using Arima and Artificial Neural Networks. J. Insect Sci. 2022, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quartey-Papafio, T.K.; Javed, S.A.; Liu, S.F. Forecasting cocoa production of six major producers through ARIMA and grey models. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2021, 11, 434–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Ramesh, D. AI based hybrid CNN-LSTM model for crop disease prediction: An ML advent for rice crop. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Kharagpur, India, 6–8 July 2021; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.C.; He, Z.F.; Wang, Z.S. Monthly climate prediction using deep convolutional neural network and long short-term memory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.C.; He, Z.F.; Wang, Z.S. Prediction of monthly average and extreme atmospheric temperatures in Zhengzhou based on artificial neural network and deep learning models. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1249300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakarla, S.K.; Schall, E.; Dettweiler, A.; Stohl, J.; Glaser, E.; Adam, H.; Teubler, F.; Ingwersen, J.; Sauer, T.; Piepho, H.P.; et al. Dependence of the abundance of reed glass-winged cicadas (Pentastiridius leporinus (Linnaeus, 1761)) on weather and climate in the upper Rhine Valley, southwest Germany. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulighe, G.; Lupia, F.; Manente, V. Climate-driven invasion risks of Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica Newman) in Europe predicted through species distribution modelling. Agriculture 2025, 15, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neta, A.; Levi, Y.; Morin, E.; Morin, S. Seasonal forecasting of pest population dynamics based on downscaled SEAS5 forecasts. Ecol. Model. 2023, 480, 110326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.P.; Wei, X.J.; Li, Y.P.; Deng, X.Q.; Zhuo, Z.H. Dynamics of Aromia bungii (Faldermann, 1835) (Coleoptera, Cerambycidae) distribution in China amidst climate change: Dual insights from MaxEnt and meta-analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Ali, M.Y.; Li, X.H.; Hu, Y.L.; Li, W.B.; Wang, Z.J.; Shi, S.S.; Zhang, J.P. Impact of temperature on age–stage, two-sex life table analysis of a Chinese population of bean bug, Riptortus pedestris (Hemiptera: Alydidae). Agriculture 2022, 12, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Zhang, D. Intelligent pest forecasting with meteorological data: An explainable deep learning approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xiao, Q.X.; Zhang, J.; Xie, C.J.; Wang, B. Occurrence prediction of cotton pests and diseases by bidirectional long short-term memory networks with climate and atmosphere circulation. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 176, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.C.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.S.; Liu, T.B.; Li, J.Y.; Teng, K.; Cai, H.L.; Xiao, Z.P.; Zhou, H.; et al. The application of integrated deep learning models with the assistance of meteorological factors in forecasting major tobacco diseases. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 236, 110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.X.; Xu, J.H.; Wang, J.M.; Long, M.S. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.Q.; Wen, Q.S.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022; pp. 27268–27286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Jin, X.Y.; Gopalswamy, K.; Gupta, G.; Park, Y.; Shi, X.J.; Wang, H.; Maddix, D.C.; Wang, Y.Y. First de-trend then attend: Rethinking attention for time-series forecasting. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.08151. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.L.; Chen, M.X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are transformers effective for time series forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Wu, R.B.; Zhu, X.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, S.C.; Li, X.L. Bi-direction label-guided semantic enhancement for cross-modal hashing. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 35, 3983–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stitsyuk, A.; Choi, J.S. xPatch: Dual-stream time series forecasting with exponential seasonal-trend decomposition. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 20601–20609. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, C.L.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, G.J.; Gao, Y.J. How much can time-related features enhance time series forecasting? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.01557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yu, W.R.; Zhu, X.H.; Zhang, C.Y.; Li, Y.D.; Zhang, S.C. MvHAAN: Multi-view hierarchical attention adversarial network for person re-identification. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.J.; Wang, Q.N.; Zhu, J.; Cao, J.Z.; Liu, T.; Yi, S.X.; Sun, Q.F.; Cui, J.H.; Li, J.W.; Song, Y.L.; et al. Quantifying climate change impacts on rice chalkiness in southern China: Future trends and spatiotemporal patterns. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Kim, J.H.; Tae, Y.W.; Park, C.B.; Choi, J.H.; Choo, J.G. Reversible instance normalization for accurate time-series forecasting against distribution shift. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Virtual, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, W.J.; Li, Q.; Lu, Z.X.; Ullah, F.; Guo, J.W.; Xu, H.X.; Lu, Y.H. Dynamic monitoring of Chilo suppressalis resistance to insecticides and the potential influencing factors. Plants 2025, 14, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.W.; Zhang, W.T. Unlocking the power of patch: Patch-based MLP for long-term time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 12640–12648. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.Q.; Nguyen, N.H.; Sinthong, P.; Kalagnanam, J. A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.14730. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.H.; Shen, L.; Zhang, R.X.; Cheng, J.H.; Ding, S.H.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Wang, Y. Hdmixer: Hierarchical dependency with extendable patch for multivariate time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 12608–12616. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.M.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8026–8037. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wu, H.X.; Dong, J.X.; Qin, G.; Zhang, H.R.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, Y.Z.; Wang, J.M.; Long, M.S. Timexer: Empowering transformers for time series forecasting with exogenous variables. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 469–498. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, T.G.; Zhang, H.R.; Wu, H.X.; Wang, S.Y.; Ma, L.T.; Long, M.S. itransformer: Inverted transformers are effective for time series forecasting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06625. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.X.; Wang, Z.P.; Nie, Y.Q.; Zhou, T.; Zohren, S.; Liang, Y.X.; Sun, P.; Wen, Q.S. Unlocking the power of lstm for long term time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 11968–11976. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).