Abstract

Agricultural product branding promotes regional economic development by enhancing brand value and market competitiveness, serving as a vital pathway for increasing farmers’ incomes and advancing the transformation of modern agriculture. This paper transcends one-dimensional analysis by examining the dual perspectives of urban-rural income disparities and regional income gaps, thereby revealing the impact of regional agricultural product branding on income inequality. This study employs panel data from 82 counties in Guangdong Province spanning the years 2010 to 2023, comprising a total of 1148 observations, and treats the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs’ designation of “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products as a policy hit. Employing a multi-period difference-in-differences model, it empirically examines the impact of regional agricultural product branding (RAPB) on income inequality. The study found the following: (1) RAPB narrowed the urban-rural income gap by 0.92% and Theil decreased significantly by about 15.3% on average. (2) Mechanism analysis indicates that RAPB mitigates income inequality through resource allocation effects, technological progress effects, and human capital accumulation effects. (3) Heterogeneity tests reveal that the inequality-alleviating effect of RAPB is most robust in regions focused on crop cultivation and areas with lower levels of agribusiness vitality, while its effect is weakened in dynamic entrepreneurial and high-yield regions. This study provides a new value metric for evaluating regional brand policies that balance efficiency and equity, revealing their core potential in promoting social fairness and coordinating urban-rural and regional development.

1. Introduction

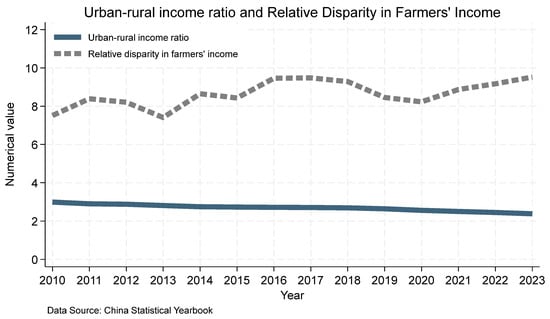

Since the launch of reform and opening-up, China has experienced sustained rapid economic growth, achieving historic leaps in national comprehensive strength and residents’ living standards. However, income inequality within the agricultural sector remains prominent throughout this development process [1]. From the perspective of per capita disposable income, the gap between urban and rural residents’ incomes remains significant. Although the urban-rural income ratio has declined annually, falling to 2.34 in 2024, it still ranks among the higher levels globally [2]. Concurrently, the trend of widening income disparities within rural areas has yet to be curbed [3]. The absolute gap between high- and low-income groups in rural areas expanded from 12,180 yuan in 2010 to 44,872 yuan in 2023. Relatively, the income multiplier between high- and low-income groups in rural areas stood at 7.51 in 2010 and has continued to climb, reaching a historical peak of 9.48 in 2017 (Figure 1). The widening income gap among different rural groups has profoundly impacted all aspects of rural life, particularly placing low-income rural populations in relative hardship and limiting their future development prospects. This stark reality constitutes the traditional perspective on understanding China’s income disparity, yet it is not the full picture. A more complex landscape emerges as development imbalances are equally deeply embedded within urban groups. Intra-urban income differentiation stems from multiple universal factors such as industrial upgrading, skill premiums, and labor market segmentation, becoming a critical dimension constraining social equity and economic growth potential [4]. Data from 2023 shows that the median per capita disposable income of China’s urban residents was only 85.06% of the average, indicating a pronounced right skew in urban income distribution. The income levels of a significant portion of the population have been “averaged out” by the high-income cohort. Intra-urban inequality may stem from more universal macro-level factors rather than solely reflecting the specific conditions of rural areas. Consequently, comprehensively examining China’s income disparity and identifying feasible policy pathways to effectively narrow this gap has become an urgent and critical task.

Figure 1.

Ratio of Urban and Rural Residents’ Income and Relative Gap in Farmers’ Income (2010–2023).

To address these multidimensional challenges, proactive explorations are underway at the national strategic level. The report of the 20th CPC National Congress elevated “improving mechanisms for integrated urban-rural development” to a pivotal position, with county-level economies—as convergence points for urban and rural factors—emerging as key vehicles for implementing this strategy [5]. Against this backdrop, a series of innovative practices aimed at activating endogenous development momentum in rural areas have emerged. Among them, regional agricultural product branding—as an institutional innovation bridging traditional agriculture and the modern market economy—has demonstrated significant potential. The 2025 Central Document No. 1 explicitly emphasizes promoting county revitalization by “cultivating distinctive agricultural industrial clusters” [6]. This policy orientation aligns with the “orange economy” concept, which emphasizes value creation through the creative transformation of cultural assets and intangible heritage [7]. Within this framework, regional agricultural product branding serves as a vital implementation pathway. Its essence lies in establishing an agricultural product identification system anchored in specific geographic regions, integrating local production techniques, historical culture, and other elements [8,9]. Such brands possess distinct public goods attributes. They not only enhance the added value of agricultural products through brand premiums and market expansion effects [10], but also transform regional cultural resources into competitive market advantages via creative value conversion mechanisms. By establishing unique regional linkage mechanisms and building inclusive benefit-sharing models, regional agricultural product branding has evolved into a foundational institutional arrangement connecting smallholder production with modern markets [11].

As a crucial institutional mechanism, regional agricultural branding carries policy expectations of boosting farmers’ incomes and driving county-level economic development [12]. However, its actual impact—particularly on income distribution structures rather than merely average income levels—remains an area of academic debate and uncertainty. In theory, regional agricultural product branding primarily generates income for producers through two mechanisms: brand premium and market expansion. Its core logic involves transforming local natural capital, ecological value, and cultural significance into market-recognized economic value through regional credibility endorsement [13] and standardized production, thereby enhancing the added value of agricultural products and broadening sales channels. However, this optimistic theoretical expectation faces significant challenges in empirical research. Research findings reveal pronounced contradictions: some studies based on cross-sectional farmer survey data confirm that households participating in Agricultural Product Branding schemes experience significant income growth [14]. Conversely, studies employing value chain analysis methods arrive at pessimistic conclusions, revealing that the majority of the surplus profits generated by Agricultural Product Branding are captured by distribution, processing, and marketing segments [15]. Primary producers are often “locked into low-end” positions at the bottom of the value chain, receiving only meager returns for their raw materials [16]. This contradiction highlights a critical issue: the income-generating effects of Regional Agricultural Product Branding are not automatically realized. Their ultimate outcomes depend heavily on the intermediary links connecting ‘potential’ to ‘reality’—namely, governance models and benefit-sharing mechanisms [17].

The public goods attributes of regional agricultural product branding necessitate its development as a multi-stakeholder collaborative governance process [18]. Different governance models shape distinctly divergent patterns of benefit distribution. The government-led model is most prevalent within the Chinese context, offering the advantage of rapid resource consolidation and top-down design [19]. However, a qualitative case study indicates that without effective empowerment of smallholder farmers, this approach may result in brand profits being channeled towards leading enterprises with close government ties [20]. Smallholders’ participation may remain confined to supplying primary products, hindering their ability to share in brand premiums. The producer association-led model serves as the institutional cornerstone of the European Union’s successful Geographical Indications system [21]. Boga & Paül (2023), by employing a cross-national comparative case study approach, found that robust producer-led industry associations are crucial arrangements for ensuring brand premiums flow back to the production end [22]. In contrast, industry associations in some Chinese regions exhibit strong characteristics of ‘administrative absorption,’ lacking sufficient independence and representativeness, thereby weakening their capacity to advocate for smallholder farmers’ interests [23]. The enterprise-driven model, where leading enterprises integrate brands and supply chains, achieves higher market efficiency. However, S. Narayanan’s comparative analysis of contract farming arrangements across five countries reveals an inherent imbalance of market power between corporations and farmers during the transfer of agricultural land. This power disparity manifests in contractual choices, with contract farming potentially undermining farmers’ long-term interests [24]. While securing stable sales channels, they struggle to equitably share the value-added benefits generated by branding.

Most existing research focuses on how regional agricultural brands increase farmers’ average income through “brand premiums” [25] and “market linkage” [26] effects, yet it generally overlooks their potential impact on income distribution structures. A fundamental theoretical and empirical question remains unresolved: Do the premiums and market gains generated by branding benefit smallholder farmers, thereby helping to reduce inequality [27,28], or are they primarily captured by a few elite participants in the value chain, thereby exacerbating existing inequalities [29]? Therefore, clarifying the causal effects of regional agricultural branding on income distribution—whether it reduces or exacerbates inequality—has become a critical prerequisite for formulating targeted policies that balance agricultural development with social equity. Based on this, this study poses the following core questions: Can regional agricultural product branding effectively alleviate income inequality? What are its specific mechanisms of action? To address these questions, this study utilizes the implementation of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs’ “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products certification policy as a quasi-natural experiment. Employing a multi-period double difference method, it conducts empirical analysis on panel data from 82 counties in Guangdong Province spanning 2010–2023. Guangdong Province stands as one of China’s most advanced regions in regional agricultural branding. By 2024, it had cultivated 547 “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products and 166 geographical indication products. This includes benchmark brands like Maoming Lychee, each generating annual output value exceeding 10 billion yuan. Its geographical indication products connect over 770,000 farming households and 13,000 business entities, contributing hundreds of billions of yuan in annual output value. This provides an exceptionally representative research setting for precisely identifying the causal effects of brand policies on income distribution.

The marginal contribution of this study manifests in three aspects. Methodologically, it employs the introduction of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products program as a quasi-natural experiment to provide a quantitative assessment of the poverty reduction and income-enhancing effects of agricultural branding. The county-level evidence offered here is more robust and convincing than analyses conducted at the city level. Conceptually, by deconstructing the dual impact of branding on income gap, the study delineates a clearer “efficiency-equity” trade-off spectrum. This conceptual refinement aids in shifting brand-building strategies from a blanket promotion approach towards more refined and inclusive governance, ultimately serving the practical goals of reducing urban-rural income inequality and fostering inclusive development. Mechanistically, this research identifies and verifies the mediating roles of resource allocation, green technological progress, and human capital accumulation in the policy effects of Agricultural Regional Public Branding, thereby broadening the analytical scope of RAPB policy research.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 1 serves as the introduction, aiming to elucidate the research background and systematically review relevant literature to establish the theoretical foundation for the study. Section 2 details the materials and methods, providing a thorough account of the theoretical framework, research hypotheses, data sources, variable construction, and empirical research methods employed in this investigation. Section 3 presents research findings and discussions, focusing on benchmark regression analysis, Bacon decomposition, validity tests, endogeneity tests, robustness tests, heterogeneity analysis, and mechanism validation to comprehensively present and deeply analyze empirical discoveries. Section 4 concludes by systematically summarizing the study’s principal discoveries, exploring their policy implications, and identifying limitations alongside directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

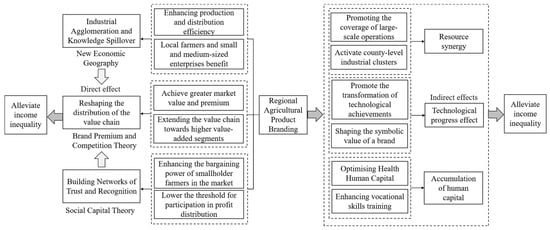

To systematically analyze the pathways through which regional agricultural product branding influences income inequality, this paper constructs an integrated theoretical framework (Figure 2). This framework posits that regional agricultural product branding exerts its effects on income inequality—as represented by urban-rural income disparities and regional income gaps among farmers—through both direct effects and indirect effects mediated by three pathways.

Figure 2.

Mechanism Framework of Regional Agricultural Product Branding on Income Inequality.

2.1.1. Direct Impact of RAPB on Income Inequality

New economic geography posits that industrial agglomeration facilitates the spillover of knowledge and technology [30], whilst Regional Agricultural Product Branding achieves economies of scale by pooling resources, technology and capital, thereby enhancing production and distribution efficiency [31]. This geographical clustering effect not only benefits local farmers and small-to-medium enterprises [32], but more crucially, it reshapes traditional agricultural value distribution through resource sharing and supply chain integration. Brand premium effects elevate the market value of agricultural products [33], while the brand and quality advantages emphasized by Porter’s competitive theory encourage consumers to pay a premium for the intangible value behind the brand [25,34]. This premium is redistributed through close collaboration across the value chain to high-value-added nodes such as processing and sales [9], enabling farmers to extend beyond primary production into diverse, high-value segments and leap from the value chain’s periphery to its premium nodes. Concurrently, regional agricultural product branding constitutes not merely an accumulation of economic resources but also a process of building social trust, cultural identity, and emotional connections [35]. Influential regional brands establish trust in the marketplace, attracting more consumers and investors. Through brand promotion, they strengthen consumers’ emotional ties to the regional brand, thereby reinforcing the region’s social capital [28]. The formation of this social capital helps elevate smallholder farmers’ bargaining position in the market and lowers the threshold for their participation in brand revenue distribution.

In summary, Regional Agricultural Product Branding leverages geographical clustering effects, brand premium effects, and social capital accumulation. It not only drives income growth for residents but also promotes economic opportunity equality and income gap convergence by reshaping value chain distribution structures and enhancing the participation capacity of disadvantaged actors.

2.1.2. Indirect Impact of RAPB on Income Inequality

Regional Agricultural Product Branding not only directly boosts farmers’ incomes but also profoundly influences income distribution structures through three indirect pathways: resource synergy effects, technological advancement effects, and human capital accumulation effects. The core of these mechanisms lies in altering the allocation patterns and accessibility of key economic factors—such as resources, technology, and skills—thereby fundamentally reshaping income distribution patterns.

Specifically, resource synergies achieve economies of scale and optimize factor allocation by systematically integrating regional agricultural resources through centralized procurement of agricultural inputs, technology dissemination, and cold-chain logistics services [36]. This approach not only enables large-scale mechanized operations to enhance regional resource efficiency and overall productivity [37], but also promotes standardized production through integrated advanced technologies, securing premium pricing for high-quality agricultural products [38]. Crucially, regional branding drives the concentration of production factors towards advantageous areas, forming distinctive industrial cluster ecosystems. This brand-driven cluster development model breaks the isolation of traditional agriculture: at the production end, standardized management systems facilitate the transformation of traditional farmers into new professional operators [39]; at the distribution end, digital marketing platforms open high-value-added channels for specialty agricultural products [40]. At the consumption end, brand cultural narratives facilitate two-way flows of resources between urban and rural areas, spurring the vigorous development of new business models such as rural e-commerce and agritourism. This creates a virtuous cycle where ‘industry attracts people, and people drive industry’ [41]. This sequence generates diversified employment and entrepreneurial opportunities for rural residents that far exceed those of traditional agriculture, with its core function being the equalization of economic opportunities between urban and rural areas.

The effect of technological advancement constitutes the core mechanism through which Regional Agricultural Product Branding overcomes diminishing marginal returns in agriculture and achieves sustained income growth [42]. During implementation, brand management bodies collaborate with regional stakeholders to establish platforms for technology adaptation, transformation, and knowledge sharing, providing a unified technical support and service system [43]. This approach to intensive production and technology sharing significantly reduces the cost of technological adaptation [44], enabling small and medium-sized farming households to benefit from technological progress. Moreover, technological innovation systematically enhances the technical sophistication and quality consistency of branded agricultural products through varietal improvement, process optimization, and quality traceability systems [45]. Regional Agricultural Product Branding further institutionalizes these technological advantages into market access barriers via standardized certification systems and geographical indication protection, thereby establishing sustainable product premium potential [46]. This premium essentially represents the value realization process of technological capital [47], and through inclusive distribution mechanisms within the industrial chain, facilitates the transmission and diffusion of economic growth outcomes to primary producers [48]. This mechanism ensures that the benefits of technological progress more broadly benefit farmers participating in regional branding initiatives, thereby mitigating income disparities among farmers within the region caused by uneven access to and application of technology.

The human capital accumulation effect operates at the fundamental level of enhancing farmers’ capabilities. The industrial upgrading and shifts in market demand brought about by Regional Agricultural Product Branding impose higher demands on farmers’ skills [49], driving human capital transformation through dual pathways: the first is endogenous incentive mechanisms, wherein market signals generated by brand premiums motivate farmers to proactively invest in human capital, optimizing time allocation to participate in skills training [50,51]; the second is through exogenous support mechanisms, where governments and enterprises establish collaborative training systems via institutional innovation. Organized training networks reduce the marginal cost of skill acquisition for farmers, facilitating the evolution of traditional experiential skills towards standardized, professional knowledge systems [52]. This not only elevates labor skill levels and total factor productivity but also creates diversified employment opportunities for farmers in areas such as agricultural processing, brand management, and logistics [9]. Concurrently, health—a vital component of human capital—is fortified throughout this process. Regional agricultural branding promotes the adoption of green agriculture and ecological cultivation techniques, improving rural environmental quality. This encourages household resource allocation towards health capital domains [53] and advances farmers’ health awareness towards modern scientific paradigms [54,55]. Such comprehensive capability enhancement not only bolsters farmers’ competitiveness in urban-rural labor markets but also mitigates income disparities within rural communities arising from differing human capital endowments.

Regional agricultural product branding, as a strategic intervention aimed at enhancing agricultural value and restructuring industrial value chains, does not yield uniform outcomes across all contexts. Its income distribution effects are profoundly constrained by structural factors originating from both within the industry and the regional environment. On one hand, distinct agricultural sub-sectors exhibit inherent differences in production technologies, product characteristics, organizational models, and market structures. These sectoral attributes directly determine the difficulty of implementing RAPB, the scale of brand rents, and how these rents are distributed across value chain segments. Industries with high product standardization and short production cycles tend to establish brand identities more readily and manage market risks more effectively, potentially enabling stable and widespread brand premiums that benefit producers. Conversely, industries with lower standardization may see brand gains dominated by a few market actors possessing specific resources and capabilities. Consequently, the income redistributive effect of RAPB inevitably varies across industry types. Meanwhile, New Structural Economics emphasizes that effective policies must account for regional factor endowment structures and their dynamic evolution, as policy outcomes are highly contingent on regional initial endowments. Embedded within specific regional socioeconomic contexts, RAPB’s benefit distribution patterns are profoundly shaped by existing local conditions—such as the vitality of new agricultural operators and production technology levels. These initial conditions define the capacity of different groups (e.g., smallholder farmers, agribusinesses) to participate in and capture brand premiums, thereby steering the distributional effects of branding toward either inclusive growth or structural differentiation.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical framework, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses for testing:

H1:

RAPB can narrow the income gap between urban and rural areas and reduce regional disparities in farmers’ incomes, thereby alleviating income inequality.

H2:

RAPB mitigates income inequality through resource synergies, technological progress effects, and human capital accumulation effects.

H3:

The impact of RAPB on income inequality exhibits systematic variations depending on the type of agricultural industry and regional agricultural conditions.

2.2. Data Sources and Variable Construction

2.2.1. Data Source

This study examines county-level administrative units in Guangdong Province from 2010 to 2023, with an initial sample pool comprising 112 counties. Data on “branded, distinctive, high-quality, and innovative” agricultural products were sourced from the Guangdong Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. County-level socioeconomic data primarily derived from the Guangdong Statistical Yearbook (2011–2024) and the China County Statistical Yearbook, with missing indicators supplemented by corresponding district (county) statistical bulletins. Nighttime light data originated from satellite remote sensing data (NPP-VIIRS and DMSP-OLS) provided by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Total green patent application data was derived from comprehensive patent information in the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) Patent Retrieval and Analysis System, classified and statistically processed according to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) IPC Green List. The foundational data for Digital-to-Reality Integration (DCRI) originates from national and local statistical bureaus; the number of newly registered agricultural enterprises is sourced from the National Industrial and Commercial Enterprise Registration Database. To ensure data quality and research consistency, we implemented a rigorous sample screening process: (1) Counties/districts with complete data gaps in core variables (e.g., urban and rural disposable income) were excluded. (2) Counties undergoing administrative mergers, divisions, or level changes during the sample period were excluded to ensure panel data continuity. (3) Counties where over 50% of explanatory variables remained missing after the above steps were excluded. Following this screening, 82 counties were finalized as the valid research sample. After data cleaning, the resulting balanced panel dataset achieved high integrity, with variable missing rates generally below 1%. Individual missing values were imputed using linear interpolation, ultimately forming a county-year balanced panel dataset comprising 1148 samples.

2.2.2. Benchmark Regression Model

As mentioned above, this paper takes “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products as a quasi-natural experiment, and uses the multi-period difference-in-differences method to analyze the impact of regional agricultural product branding on income gap. The specific model is set as follows:

Among them, subscripts and represent regions and years, respectively; represents the explained variable, which is the variable set of urban-rural income gap and the urban-rural income Theil index; is the dummy variable of whether the district and county identify “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products. is the set of control variables; , and are random error term, county fixed effect and annual fixed effect, respectively.

2.2.3. Dependent Variable: Urban-Rural Income Gap (URIG) and the Urban-Rural Income Theil Index (Theil)

The explained variables are the urban-rural income gap (URIG) and the urban-rural income Theil index (Theil). The urban-rural income gap is measured by the ratio of the per capita disposable income of urban residents to the per capita disposable income of rural residents in each county [49]; the Theil index of urban-rural income gap originated from information theory and was proposed by Theil. It is a classic tool to measure the degree of inequality. This study employs the Taier Total Index at the urban and rural levels, calculated as follows:

Among these, : they represent urban and rural groups, respectively. : represents the total income of group . : represent the total income of all residents. : represents the population of group . : represents the total population. The higher the index value, the greater the income inequality between urban and rural areas. Compared to other indicators such as the Gini coefficient, the Theil index is more sensitive to changes at both ends of the income distribution (high-income and low-income groups), thereby providing a more comprehensive reflection of inequality.

2.2.4. Independent Variable: Regional Agricultural Product Branding (RAPB)

The core explanatory variable is the construction of regional agricultural product branding (RAPB). In this study, RAPB was constructed according to the “list of special and excellent new agricultural products “published by Guangdong Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in 2015, 2017 and 2020, respectively. Based on the measurement method of Qie H et al. [56], this paper takes the specific year in which each county first identifies “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products as the policy implementation time, and assigns the county benchmark year and subsequent years that identify “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products to 1, and assigns 0 to other years, and assigns 0 to all years of counties that do not identify “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products. The identification of “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products requires county RAPB to have a certain scale, significant regional characteristics, unique nutritional quality characteristics, stable supply and consumer market, high public awareness and reputation, so as to explore the effectiveness of RAPB.

2.2.5. Control Variables

Because the urban-rural income gap is also influenced by regional socioeconomic development and policy factors, drawing on established research [33,49,57,58,59], this study incorporates a set of control variables into the regression model. These include the fiscal scale of government (FISG), industrial structure (INSU), commercial market size (COMS), information technology level (INFT), financial development (FIND), and educational resource quality (EDRQ). To mitigate potential estimation bias caused by heteroscedasticity, all control variables are subjected to a logarithmic transformation in the empirical analysis. The specific variable name, description and descriptive statistical results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of main variables.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Benchmark Regression

Table 2 reports the baseline regression results. Among them, the explained variable of models 1 and 2 is URIG, and the explained variable of models 3 and 4 is Theil. Specifically, model 1 and 3 control the county fixed effect and annual fixed effect, and model 2 and 4 further add control variables. The results indicate that Regional Agricultural Product Branding (RAPB) narrowed the urban-rural income gap by 0.92% and Theil decreased significantly by about 15.3% on average. Across all models, the RAPB coefficient exhibited a negative correlation at the 1% significance level and was statistically significant. These findings carry salient implications for understanding urban-rural inequality. The observed decline in the urban-rural income ratio reflects tangible progress in income convergence between urban and rural residents, suggesting that RAPB contributes to rebalancing regional economic structures under the strategy of Rural Revitalization. The simultaneous reduction in the Theil index further reveals a decline in intra-regional stratification, indicating that the benefits of brand-driven agricultural development are broadly shared rather than concentrated among a subset of households.

Table 2.

Results of the Benchmark Regression.

By adding value to rural products, enhancing market access, and strengthening rural industrial competitiveness, RAPB effectively raises earnings at the lower end of the income distribution, thereby mitigating structural disparities. This dual narrowing—both between urban and rural areas and within rural regions—underscores the role of RAPB as not only an engine of rural economic growth but also an instrument for fostering more inclusive and equitable development.

3.2. Goodman-Bacon Decomposition of Multi-Period DID Estimation Bias

To assess the robustness of our staggered difference-in-differences design against potential bias from heterogeneous treatment effects, we conducted a Bacon decomposition [18]. As presented in Table 3, the estimation results for both the URIG and Theil outcome variables are predominantly driven by the most reliable comparison, “Treated vs. Never-treated,” which carries weights of 82% and 85%, respectively. Meanwhile, the comparisons potentially susceptible to bias—namely, “Earlier Treated vs. Later Control” and “Later Treated vs. Earlier Control”—collectively account for less than 20% of the total estimate in both cases. Crucially, the average treatment effect estimates from all three types of comparisons are consistent in sign (negative) and closely aligned in magnitude with the overall TWFE estimate.

Table 3.

Bacon decomposition results.

This pattern of results indicates that the negative treatment effects we observe (−0.009 for URIG and −0.004 for Theil) are not driven by problematic control group constructions. Therefore, we conclude that the baseline TWFE model estimates are highly robust, and the risk of substantial bias from heterogeneous treatment effects is minimal.

3.3. Distribution Effect

Table 4 presents the estimation results from a grouped regression based on income quantiles of farmers and urban residents within districts and counties. The distributional effects of RAPB exhibit significant group heterogeneity. The impact of RAPB on URIG and Theil indices displays a “stepwise” pattern from low to high income groups. For low-income farmers (Q0–Q40), all RAPB coefficients are negative but not statistically significant. For middle- and high-income farmers (Q40–Q100), RAPB coefficients are significantly negative for both URIG and Theil. RAPB has yet to significantly benefit the lowest-income farmer cohort, who may struggle to gain from branding due to barriers in capital, skills, or market access. Moreover, RAPB primarily mitigates income disparities among middle- and high-income farmer groups.

Table 4.

Impact of RAPB on Income Distribution.

The impact of RAPB extends more broadly to urban populations with lower significance thresholds. RAPB significantly reduces URIG for income groups Q20 and above and markedly lowers Theil for urban middle-to-high-income groups (Q40–Q100). Overall, brand economy development significantly narrows income disparities among middle-to-high-income groups but has limited effects on low-income groups, indicating a certain degree of insufficient pro-poor distribution in RAPB’s economic benefits.

Comparing the two groups reveals differing benefit thresholds for RAPB: the threshold for benefiting farmers is higher (Q40 and above), while the threshold for benefiting urban residents is lower (Q20 and above). This confirms urban-rural disparities in the distributional effects of the brand economy, with farmers—particularly low-income farmers—occupying a relatively disadvantaged position in sharing its dividends. Urban groups are more likely to engage in marketing and service segments of the brand economy, thus enjoying broader benefits. Rural groups, however, are predominantly positioned at the production end. Only medium-to-high-income farmers who have achieved a certain scale and market bargaining power can effectively capture brand premiums. While advancing the brand economy, targeted measures should be implemented concurrently. These include enhancing skills training, financial support, and supply chain integration for low-income farmers to lower their barriers to participation in the brand economy. This approach ensures the sharing of growth benefits and prevents existing income disparities from widening due to group heterogeneity.

3.4. Validity Check

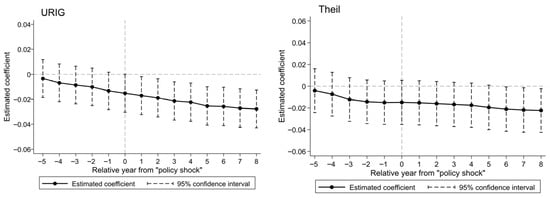

3.4.1. Parallel Trend Test

This study employs an event study approach to conduct parallel trend tests, with the results presented in Figure 3. For both URIG and Theil indices, all estimated coefficients for pre-treatment periods (Period −5 to Period −1) are statistically insignificant, satisfying the parallel trends assumption. Following policy implementation, the RAPB generates significant mitigating effects on both measures, though their dynamic paths differ: the treatment effect on URIG becomes significantly negative immediately in the implementation period (Period 0) and continues to intensify in magnitude, whereas the negative effect on the Theil index strengthens further beginning around Period 6, following a phase of mid-term accumulation. These findings indicate that the RAPB policy has a robust long-term effect in alleviating urban-rural income inequality, albeit with distinct intensification patterns across different measurement indicators. The test results provide valid support for the reliability of our identification strategy.

Figure 3.

Parallel trend chart.

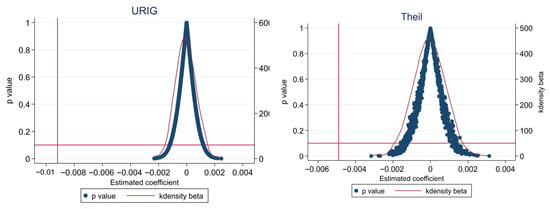

3.4.2. Placebo Test

In order to eliminate the interference of potential unobservable confounding factors on the benchmark results, this paper conducts a placebo test by constructing a randomly generated experimental group: First, 68 districts and counties were randomly selected to simulate the identification of “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural products, and the policy time points were randomly generated; then the core explanatory variables were included in Equation (1) and repeated 1000 times to eliminate the impact of random disturbances. Figure 4 shows the regression coefficient, kernel density and p value of URIG and Theil indices. The results show that the coefficient conforms to the normal distribution and most of them are not significant. At the same time, the baseline regression results were significantly different from the results of the placebo test. It is confirmed that the policy effect Is not caused by other accidental factors, and the regression results are robust.

Figure 4.

Placebo test chart.

3.5. Endogeneity and Robustness Testing

3.5.1. Instrumental Variables Test

To mitigate potential endogenous bias in the model, this study employs terrain slope as an instrumental variable. The rationale for this choice rests on the following considerations: First, there exists a significant causal relationship between terrain slope and RAPB. Moderately sloped areas, due to their soil, sunlight, and water-heat conditions, are more suitable for developing large-scale, standardized specialty agriculture. This is precisely the crucial foundation for building regional public brands with stable quality and unified supply capabilities. Conversely, steep slopes not only hinder mechanized operations but also increase the difficulty and cost of standardized production, thereby suppressing the formation and development of regional agricultural product brands. Thus, terrain slope directly determines a region’s initial endowment for cultivating branded agriculture by influencing the geographical conditions of agricultural production, satisfying the correlation condition for instrumental variables. Second, as a historically formed natural geographical feature, terrain slope is highly likely to satisfy the exclusivity constraint. Within this study’s control variable framework, we systematically incorporated modern economic channels potentially influenced by both topography and income disparities: we controlled for regional economic development levels (FISG, FIND), industrial structure (INSU), commercialization degree (COMS), and informatization level (INFT). This excludes the possibility that slope affects income disparities through general economic growth and structural transformation pathways. We further controlled for public resource allocation (EDRQ), capturing potential indirect effects of slope through its influence on the accessibility of public services like education. After controlling for this series of variables, it is unlikely that natural terrain slope directly influences contemporary urban-rural income disparities through systemic channels beyond RAPB. Its potential impact on income distribution primarily and most directly manifests by shaping local agricultural development pathways and patterns, with branding serving as the core manifestation of this channel in the modern economy. Therefore, using terrain slope as an instrumental variable is theoretically robust. The validity of the instrumental variable is supported by a series of statistical tests: Table 5 shows that the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM test is significant at the 1% level, rejecting the null hypothesis of Insufficient Identification. Both the Kleibergen-Paap Wald F statistic and the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic exceed the critical values at the 10% level of the Stock-Yogo test, indicating no severe instrumental variable weakness. The Anderson-Rubin Wald test is significant at the 1% level, providing robust evidence for the statistical significance of RPAB policies in mitigating income inequality.

Table 5.

Instrumental Variables Estimation Results.

3.5.2. Interleaved Double Differential Test

While the baseline analysis indicates that the RAPB policy significantly alleviates income inequality, recent methodological literature has highlighted potential estimation biases in traditional two-way fixed effects models due to heterogeneous treatment effects in staggered adoption designs. To address this methodological concern, we employ the more robust CSDID approach [60]. for our robustness test. The results presented in Table 6 confirm the robustness of our initial findings: the overall average treatment effect is significantly negative for both the URIG and Theil indices, establishing the policy’s beneficial role in alleviating income inequality. Furthermore, the analysis reveals notable heterogeneity in effect magnitudes across implementation cohorts, with the 2017 cohort showing the strongest reduction in URIG while the 2015 cohort demonstrates the largest effect on the Theil index. These findings not only strengthen the evidence for policy effectiveness but also indicate systematic variation in treatment effects depending on implementation timing, providing crucial empirical insights for future policy optimization.

Table 6.

The estimation results of the heterogeneous treatment effects.

3.5.3. Replace the Explained Variable

To test the robustness of the benchmark regression results, we further replaced the core explanatory variable RAPB with the logarithm of the number of valid “famous, special, excellent, and new” agricultural product certifications within the county. The rationale for selecting this variable is as follows: First, the number of brand certifications measures the depth and cumulative intensity of branding development in the region. A region with multiple well-known brands is likely to exhibit brand economy effects that differ significantly in magnitude from those of a region with only one brand. Second, replacing a binary variable with a continuous variable allows for more precise capture of changes in branding levels, helping mitigate potential measurement errors in policy effect estimation. Table 7 reports the regression results after replacing the explanatory variable. As shown in Models 16 and 17, the coefficient of RAPB_num is significantly negative in both URIG and Theil measures, with values of −0.0053 and −0.0018, respectively, passing significance tests at the 1% and 5% levels. This result is highly consistent with the benchmark regression findings. It indicates that regional agricultural product branding not only contributes to narrowing the urban-rural income gap at the “from zero to one” stage but also exhibits significant cumulative effects: the greater the number of brands a region possesses, the stronger its positive impact on mitigating income inequality. We thus reaffirm the core conclusion of this paper: RAPB serves as an effective pathway for alleviating income inequality.

Table 7.

Replace the explained variable regression results.

3.5.4. Other Robustness Tests

This study also conducts a series of robustness tests from multiple perspectives. The results, reported in Table 8, include the following: (1) PSM-DID with caliper matching (Models 18 and 19); (2) Winsorizing the dependent variable at the 1% level, which does not alter the signs or significance of the key coefficients (Models 20 and 21); double/debiased machine learning (DDML) estimation to address potential model misspecification and nonlinear confounding, with the results confirming our main findings (Models 22 and 23); and (4) controlling for confounding policies, namely the Low-Carbon City, E-Commerce, and Gigabit City policies(Models 24and 25). Collectively, the results from this battery of tests confirm that the effect of RAPB in mitigating income inequality is highly robust.

Table 8.

Other robustness test results.

3.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

Table 9 reports the results of the heterogeneity analysis regarding the impact of RAPB on income inequality. The analysis, conducted primarily along the dimensions of industry type and regional conditions, reveals differences in the effects of branding. The results from Models 27 and 26 indicate significant differences in the effect of branding on alleviating income inequality across various agricultural sectors. The branding effect is most pronounced in the crop cultivation sector, suggesting that promoting brand building in this area has a stable and strong positive effect on reducing both the urban-rural income gap and overall inequality. In contrast, the effects are limited or insignificant in the animal husbandry and aquaculture sectors. We further examined the interactive effects of branding with regional agribusiness vitality and production levels. In Models 28 and 29, the coefficient for the interaction term RAPB × agribusiness is significantly positive. This finding suggests that in regions with a higher number of new agricultural enterprises, the development of branding may exacerbate income inequality. A possible explanation is that the benefits of branding in the initial stages might be captured more by newly entering agribusinesses with greater resources and market capabilities, thereby widening income disparities within the group. The results from Models 30 and 31 show that the coefficient for the interaction term RAPB × high_yield is also positive, but it is only significant for URIG and not significant in the model for overall inequality. This implies that in high-yield regions, the positive effect of branding on alleviating urban-rural income inequality may be partially weakened.

Table 9.

Heterogeneity analysis results.

In summary, the heterogeneity analysis reveals that agricultural product branding is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Its effect on alleviating income inequality exhibits distinct structural characteristics: at the industry level, the effect is primarily driven by branding in the crop cultivation sector; at the regional level, branding may be accompanied by the risk of widening income disparities in areas with strong agribusiness vitality. Therefore, policy formulation should be more targeted. While vigorously promoting branding in the crop cultivation sector, supporting measures are necessary to ensure the inclusive distribution of branding benefits. Particularly in regions with active agricultural entrepreneurship and high yields, it is crucial to guard against the potential negative distributional effects of branding.

3.7. Mechanism Analysis

This section aims to systematically examine the intrinsic transmission mechanisms through which RAPB mitigates income inequality. Based on theoretical analysis, we propose the following three core transmission pathways, resource allocation effects, technological progress effects, and human capital accumulation effects and construct corresponding mediating variables for empirical testing. We employ the following mediation effect model for a three-step regression:

Among them, is the mechanism variable, and the remaining variables are consistent with the benchmark regression model.

- Resource Allocation Channel: Mechanization: Branding necessitates product standardization and economies of scale, compelling agricultural production to adopt more machinery to enhance efficiency and ensure quality. We measure this using total agricultural machinery power per capita [37]. Economic Prosperity: Successful branding elevates the reputation of regional agricultural products, driving development in related industries (e.g., logistics, packaging, rural tourism) and stimulating regional economic activity [61]. We use the average nighttime light intensity as a proxy for regional economic prosperity [62].

- Technological Advancement Channel: Green Innovation: To maintain brand reputation and achieve differentiation, producers gain greater incentives for green and sustainable technological innovation [63]. We use the total volume of green patent applications as the measurement indicator [64]. Digital Integration: Branding strategies often integrate digital marketing, supply chain management, and traceability systems [65]. We measure digital integration through the level of Digital and Real Integration.

- Human Capital Accumulation Channel: Labor Productivity: Branding drives scaled production and higher technical demands, prompting labor to upgrade skills and increase per capita output [66]. We measure this using the ratio of value added to employed personnel [47]. Public Healthcare: Increased local fiscal revenue and economic development from branding may enhance government capacity to improve public services like healthcare [34]. We measure this using hospital beds per 10,000 people [67].

3.7.1. Mechanism Analysis Results

The results of Step 1 regression are shown in Table 2. The results of Step 2 and Step 3 regressions are summarized in Table 10. Based on the results of the mechanism test, this study finds that RAPB primarily mitigates income inequality through three core pathways: Resource Allocation, Technological Progress, and Human Capital Accumulation. Specifically, within the Resource Allocation channel, branding significantly drives agricultural mechanization and regional economic prosperity, both of which have been proven to effectively curb urban-rural income gaps and regional inequality [68]. Within the Technological Progress channel, branding not only incentivizes green technological innovation but also promotes the integration of digital and physical economies. Both of these technological pathways demonstrate a significant mitigating effect on income inequality. Through the Human Capital Accumulation channel, branding enhances labor productivity and improves public healthcare services, thereby effectively boosting workers’ income-generating capacity and social welfare levels [69], exerting a systemic mitigating effect on income inequality. These three pathways collectively form a multidimensional transmission system through which branding alleviates income inequality, confirming its comprehensive governance effects in optimizing resource allocation, driving technological innovation, and accumulating human capital.

Table 10.

Results of the Mechanism Path Analysis.

3.7.2. Bootstrap Mediation Tests

The bootstrap test in Table 11 robustly confirms the significant mediating channels through which RAPB alleviates income inequality. The indirect effects for all six paths (A1–C2) are negative and statistically significant, with 95% confidence intervals excluding zero, validating the three mechanisms of Resource Allocation, Technological Advancement, and Human Capital Accumulation. The strength of these mediating roles varies: the Human Capital channel (C1, C2) shows the largest indirect effect on the URIG index, while Green Innovation (B1) is the most substantial for the Theil index. Concurrently, the persistently significant direct effects indicate that RAPB maintains a strong direct impact on reducing inequality alongside these indirect pathways.

Table 11.

Results from Bootstrap Mediation Tests.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Research Findings

As a key strategy for promoting urban-rural integration in the post-poverty-alleviation era, regional agricultural product branding has pioneered a new institutional paradigm for mitigating income inequality. Utilizing balanced panel data from 82 counties in Guangdong Province (2010–2023), this study employs a multi-period difference-in-differences approach to empirically analyze the mechanisms through which regional agricultural product branding alleviates income inequality. The findings yield robust evidence and nuanced insights with significant policy relevance.

First, RAPB significantly alleviated income inequality between urban and rural areas. Specifically, RAPB narrowed the urban-rural income gap by 0.92% and Theil decreased significantly by about 15.3% on average. The benchmark regression results unequivocally confirm that RAPB serves as an effective tool for mitigating urban-rural income disparities and intra-regional stratification. It not only significantly promotes income convergence between urban and rural areas by enhancing the value and market competitiveness of agricultural products, but also drives inclusive growth, ensuring that the benefits of development are widely shared within rural communities. This demonstrates that agricultural branding strategies transcend mere economic growth objectives, simultaneously serving as a “social equalizer” that advances inclusive development and structural equity.

Second, the mechanism analysis in this study reveals that agricultural branding serves as a crucial driver for propelling rural industries toward “intrinsic growth.” By optimizing resource allocation, stimulating technological innovation, and accumulating human capital, it facilitates a shift from “selling resources” to “selling brands” and from “prioritizing output” to “prioritizing efficiency.” This transformation inherently aligns with the core requirements of high-quality development and narrowing income disparities.

Third, our heterogeneity analysis reveals that the impact of agricultural branding on income inequality exhibits significant sectoral and regional heterogeneity. The income-generating effects of brand building are not universally applicable. They are most pronounced in crop farming but have limited impact in livestock and fisheries. Furthermore, in regions with strong agricultural entrepreneurship or high yields, branding may exacerbate income disparities due to unequal profit distribution. This indicates that branding policies must abandon a “one-size-fits-all” approach and instead be meticulously designed to align with industrial structures and regional characteristics.

4.2. Policy Impact

Based on the above conclusions, this paper proposes the following policy implict:

4.2.1. Implementing a “Targeted Industry Support” Strategy to Move Beyond One-Size-Fits-All Approaches

Shift away from the traditional practice of supporting agricultural branding as a monolithic entity. Instead, allocate resources differentially based on industry characteristics. Prior to rolling out branding initiatives in the agricultural sector, conduct a preemptive “income distribution impact assessment.” Support should prioritize building a tight-knit “company + cooperative + farmer” interest linkage mechanism rather than focusing solely on brand promotion, ensuring farmers at the end of the supply chain share in the benefits.

4.2.2. Establish a “Profit-Sharing and Risk-Prevention” Mechanism to Address Regional Disparities

In regions with strong entrepreneurial vitality and high productivity, brand policies must be accompanied by robust distribution adjustment measures to prevent the “rich getting richer.” On one hand, establish a brand profit-sharing fund by allocating a percentage of profits from branded enterprises or regional brand usage fees into a dedicated fund. This fund supports local smallholder farmers through technological upgrades, market expansion, or direct subsidies, achieving “strengthening the weak through the strong.” On the other hand, cooperative functions should be strengthened by encouraging and supporting farmers to establish or join specialized cooperatives. These cooperatives can serve as unified interfaces with brand markets, enhancing smallholders’ bargaining power and risk resilience to prevent their marginalization in competition with resource-rich emerging agribusinesses.

4.2.3. Implement “Inclusive Entrepreneurship” Incentives to Guide Capital Toward Positive Impact

Incorporate “reducing income inequality” as a core metric in regional agricultural entrepreneurship support policies. This involves reforming subsidy and credit policies: For newly established agricultural enterprises, the amount of government subsidies or low-interest loans they receive should be tied to their contribution to local employment, the proportion of locally sourced agricultural products purchased, and the extent of contractual cooperation established with farmers. Enterprises demonstrating outstanding performance in promoting income equity should receive stronger incentives. Second, promote the “social enterprise” model by encouraging and supporting agricultural social enterprises dedicated to solving societal problems. Such enterprises will inherently prioritize inclusivity and fairness during their branding process.

4.2.4. Implement Monitoring and Dynamic Evaluation of “Brand Social Impact”

Establish a brand effectiveness assessment system that transcends economic metrics, incorporating income distribution effects into core monitoring. On one hand, introduce “inclusive brand” certification by developing standards to accredit brands meeting benchmarks in boosting smallholder farmer incomes, safeguarding employee welfare, and fostering community development. Use this certification as the basis for government priority procurement and promotion. On the other hand, establish a policy exit mechanism. For regions or projects where branding significantly exacerbates internal income disparities and fails to implement effective rectifications, the government should have the authority to suspend or revoke related policy support, ensuring public resources are directed toward areas generating positive social benefits.

Policies should not stop at promoting brands “from nothing to something,” but should also meticulously guide brands “from something to goodness.” This ensures that the economic growth achieved through branding is transformed into broader social welfare, effectively alleviating income inequality.

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. The Shaping of Branding Effects by Industry Characteristics and Initial Conditions

A key finding of this study is that the income distribution effects of RAPB are primarily concentrated in crop cultivation, while showing negligible impact in animal husbandry and aquaculture. This observation indicates that the effectiveness of branding is profoundly dependent on the intrinsic characteristics of the industry. This study attributes this phenomenon to differing constraints shaped by several fundamental industry features:

First, variations in product standardization and controllable quality. Successful regional brands are built upon stable, predictable product quality. Crop products typically lend themselves more readily to achieving uniformity in appearance, taste, and safety standards through cultivation protocols and technology dissemination. Conversely, livestock and aquatic products are more susceptible to variations in individual health, disease risks, and subtle changes in rearing environments. The greater difficulty and cost of standardized production create inherent barriers to establishing and maintaining a highly credible, unified regional brand.

Second, differences in value chain structures and the difficulty of integrating smallholder farmers. Fair distribution of brand benefits requires effective integration of smallholder farmers into the value chain. Crop products generally have longer shelf lives and relatively simple post-harvest handling processes, facilitating centralized procurement, grading, and sales by cooperatives or leading enterprises, thereby passing brand premiums to producers. However, livestock and aquaculture sectors often rely on highly specialized cold chain logistics and immediate processing facilities. These require substantial fixed asset investments, making supply chains highly susceptible to domination by a few large enterprises. This value chain structure creates barriers for resource-constrained small-scale farmers, leading to “elite capture” of brand dividends and hindering inclusive growth.

Third, differences in consumer perception and pathways to brand premium realization. For crop products, consumers can intuitively link specific regional terroir conditions to unique flavors and quality—this “terroir effect” forms the core value of geographical indications and regional brands. Conversely, many livestock and aquatic products function as fresh raw materials or intermediate processed goods, blurring the consumer-perceived connection between origin and quality. This obscures their capacity to command substantial brand premiums.

In summary, this finding reveals the potential limitations and risks of RAPB. In crop agriculture, branding is more likely to serve as an effective tool for promoting equitable development. However, in livestock and aquaculture, without targeted supporting measures to improve small producers’ market access and bargaining power, blindly pushing for branding may yield minimal results due to the inherent structure of the value chain, or even exacerbate income disparities within the group.

4.3.2. Heterogeneity of Brand Value and Measurement Simplification

This study is constrained by the lack of systematic brand strength data (e.g., brand value, market share, consumer recognition). Current models struggle to accurately capture the dynamic spectrum of branding progression from “weak” to “strong,” potentially leading to biased estimates of the true intensity and conditions for policy effects. Future access to more granular commercial data or the development of continuous brand strength indicators through big data technologies could significantly deepen our understanding of this issue. Future research could explore constructing continuous brand strength indicators (e.g., brand value, market share) to more precisely capture the nonlinear impact of branding on income inequality across its dynamic progression from “weak” to “strong.”

4.3.3. Implicit Assumptions in Causal Inference: The Challenge of Spatial Spillover Effects

Successful agricultural brands may generate a “siphon effect” or “demonstration effect” on surrounding areas. The existence of this spatial dependency violates the SUTVA assumption, leading to biased estimates of a policy’s overall effect. Future research should employ spatial econometric models or network analysis methods to formally identify and quantify the spatial spillover effects of RAPB. This would address the question: To what extent does the branding of one county benefit or harm its neighbors? Such insights are crucial for designing regional coordination policies.

4.3.4. Extending External Validity: Building a Universal Policy Knowledge System

This study provides robust internal evidence on the relationship between RAPB and income inequality using Guangdong Province as a case study. As a pioneer demonstration zone, Guangdong’s successful practices reveal the potential of branding policies under ideal conditions. Building on this foundation, a highly valuable future research direction involves conducting systematic replication studies across regions with varying resource endowments and developmental stages. For instance, comparative analyses could be conducted in major agricultural provinces in central and western China to examine how branding policy outcomes vary under relatively weaker market environments and infrastructure conditions. Such research would help construct a knowledge system regarding the applicability conditions of branding policies, clarifying their boundaries and prerequisites for effectiveness. This would provide precise scientific grounds for tailored policy interventions across different regions.

4.3.5. From Average Effects to Heterogeneous Effects: Deepening the Precision of Policy Evaluation

This study employs a binary treatment variable to clearly identify the “average treatment effect” of RAPB, laying a methodological foundation for affirming the policy’s overall value. Future research should progress beyond “whether it works” to “how to make it more effective,” focusing on deconstructing the heterogeneity within branding. This will open the “black box” of the branding process, shifting policy evaluation from merely assessing “presence or absence” to optimizing “dosage.” It will provide policymakers with more direct guidance on how to allocate resources precisely and advance policies in phased steps.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: H.C. and J.Z.; methodology: H.C. and J.Z.; software: H.C.; validation: J.Z. and C.G.; formal analysis: H.C.; writing—original draft prep-ration: J.Z. and C.G.; writing—review and editing: H.C., J.Z. and C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project of National Philosophy and Social Sciences: 22BJY089.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The financial support mentioned in the Funding part is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y. Demystifying the Geography of Income Inequality in Rural China: A Transitional Framework. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y. Global Value Chain Participation, Employment Structure, and Urban–Rural Income Gap in the Context of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Guo, X.; Jiang, H. Rural E-Commerce and Income Inequality: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, E.; Gupta, R.; Meszaros, J. The Impact of Macroeconomic Factors on Income Inequality: Evidence from the BRICS. Econ. Model. 2020, 91, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inwood, S. Agriculture, Health Insurance, Human Capital and Economic Development at the Rural-Urban-Interface. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.A.; Lourenzani, A.E.B.S.; Caldas, M.M.; Bernardo, C.H.C.; Bernardo, R. The Benefits and Barriers of Geographical Indications to Producers: A Review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, S.; Alshyab, N. Orange Economy: Definition and Measurement—The Case of Jordan. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2023, 29, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Su, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Complexity Analysis for Price Competition of Agricultural Products with Regional Brands. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2021, 2021, 5460796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Qiao, G. Can Creating an Agro-Product Regional Public Brand Improve the Ability of Farmers to Sustainably Increase Their Revenue? Sustainability 2024, 16, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, Á.; Jantyik, L.; Maró, Z.M.; Moir, H.V.J. Understanding the Real-World Impact of Geographical Indications: A Critical Review of the Empirical Economic Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, D.; Hatzithomas, L.; Fotiadis, T.; Gasteratos, A. The Impact of Brand Awareness and Country of Origin in the Advertising Effectiveness of Greek Food Products in the United Kingdom: The Case of Greek Yogurt. Foods 2022, 11, 4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glogovețan, A.-I.; Pocol, C.B. The Role of Promoting Agricultural and Food Products Certified with European Union Quality Schemes. Foods 2024, 13, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano, M.; Gaspar, P.; Mesias, F.J. Creating Market Opportunities in Rural Areas through the Development of a Brand That Conveys Sustainable and Environmental Values. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Singh, P.K. Role of Market Participation on Smallholder Vegetable Farmers’ Wellbeing: Evidence from Matching Approach in Eastern India. Agribusiness 2023, 39, 1217–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Yu, X. Profit Distribution Mechanism of Agricultural Supply Chain Based on Fair Entropy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.Z.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Asif, M.; Foster, G. Bringing More Value to Small Farmers: A Study of Potato Farmers in Pakistan. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 829–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Luo, C.; Hu, Z. Can Agricultural Industry Integration Reduce the Rural–Urban Income Gap? Evidence from County-Level Data in China. Land 2024, 13, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Tao, X. A Study on the Evolutionary Game of the Four-Party Agricultural Product Supply Chain Based on Collaborative Governance and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; de Jong, M.; Yun, S.; Zhao, M. The Multi-Level Governance of Formulating Regional Brand Identities: Evidence from Three Mega City Regions in China. Cities 2020, 100, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Li, D.; Qian, H.; Zhong, Z. Political Power and Risk Sharing in an Intermediary-Led Cooperative: Theory and Empirical Observations from China. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2025, 52, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, R. Geographical Indications and Their Relationship with Trade Marks in EU Law. IIC—Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law 2015, 46, 843–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, R.; Paül, V. ‘Because of Its Size, It’s Not Worth It!’: The Viability of Small-Scale Geographical Indication Schemes. Food Policy 2023, 121, 102549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X. From Strong Intervention to Weak Intervention: Research on the Transformation of Developmental Government Behavior under the Background of Rural Revitalization: Case Analysis Based on the Development Process of Watermelon Industry in L Town. J. Jishou Univ. Sci. Ed. 2022, 43, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S. Researching and Theorizing Contract Farming. In Contract Farming in Developing Countries: The Promise and Its Perils; Narayanan, S., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 27–40. ISBN 978-3-031-76487-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, L.; Yang, X. Is Consumers’ Willingness to Pay Premium for Agricultural Brand Labels Sustainable?: Evidence from Chinese Consumers’ Random n-Price Auction Experiment. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Han, M. Addressing Global Challenges: How Does the Integration of Rural Industries in China Enhance Agricultural Resilience? PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Li, G. The Impact of Agricultural Product Branding on Farmers’ Income Inequality: Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1488347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X. The Impact of Brand Trust on Consumers’ Behavior toward Agricultural Products’ Regional Public Brand. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J.; Vicol, M.; Pol, G. Living under Value Chains: The New Distributive Contract and Arguments about Unequal Bargaining Power. J. Agrar. Change 2022, 22, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Lenzi, C. Is Innovation in Cities a Matter of Knowledge-Intensive Services? An Empirical Investigation. Innov.-Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 25, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roest, K.; Ferrari, P.; Knickel, K. Specialisation and Economies of Scale or Diversification and Economies of Scope? Assessing Different Agricultural Development Pathways. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 59, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Xiong, L.; Kong, F. Does Economic Agglomeration Improve Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity? Evidence from China’s Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Prog. 2022, 105, 00368504221135460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, S.; Wen, J. Spatial Distribution Patterns and Sustainable Development Drivers of China’s National Famous, Special, Excellent, and New Agricultural Products. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataineh, M.J.; Sanchez-Sellero, P.; Ayad, F. Green Is the New Black: How Research and Development and Green Innovation Provide Businesses a Competitive Edge. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 1004–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, W. The Impact of Cultural Memory and Cultural Identity in the Brand Value of Agricultural Heritage: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, F.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Sriboonchitta, S. Promotion Effect of Agricultural Production Trusteeship on High-Quality Production of Grain-Evidence from the Perspective of Farm Households. Agriculture 2023, 13, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Rizwan, M.; Abbas, A. Exploring the Role of Agricultural Services in Production Efficiency in Chinese Agriculture: A Case of the Socialized Agricultural Service System. Land 2022, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, J.; Xu, D. The Impact of Agricultural Socialized Service on Grain Production: Evidence from Rural China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, T.; Jia, W.; Quan, T.; Xu, Y. Impact of Farmers’ Participation in the Transformation of the Farmland Transfer Market on the Adoption of Agricultural Green Production Technologies. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, D. Can Agricultural Digital Transformation Help Farmers Increase Income? An Empirical Study Based on Thousands of Farmers in Hubei Province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 14405–14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Sargani, G.R.; Wang, R.; Jing, Y. Unveiling the Spatio-Temporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanism of Rural Industrial Integration Development: A Case of Chengdu-Chongqing Economic Circle, China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.; Qin, G.; Xu, Y.; Fu, C. Sustainable Growth, Input Factors, and Technological Progress in Agriculture: Evidence from 1990 to 2020 in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1040356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lyu, D. Research and Application of Information Service Platform for Agricultural Economic Cooperation Organization Based on Hadoop Cloud Computing Platform Environment: Taking Agricultural and Fresh Products as an Example. Clust. Comput.-J. Netw. Softw. Tools Appl. 2019, 22, 14689–14700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhu, T.; Jia, W. Does Internet Use Promote the Adoption of Agricultural Technology? Evidence from 1 449 Farm Households in 14 Chinese Provinces. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, X.; Li, M. Research on the Influencing Factors of Chinese Agricultural Brand Competitiveness Based on DEMATEL-ISM. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, V.; Falco, C.; Curzi, D.; Olper, A. Trade Effects of Geographical Indication Policy: The EU Case. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Gu, T.; Shi, Y. The Influence of New Quality Productive Forces on High-Quality Agricultural Development in China: Mechanisms and Empirical Testing. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y. Path to Sustainable Development: Does Digital Economy Matter in Manufacturing Green Total Factor Productivity? Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y. Geographical Indication, Agricultural Products Export and Urban-Rural Income Gap. Agriculture 2023, 13, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sarkar, A.; Xia, X.; Memon, W.H. Village Environment, Capital Endowment, and Farmers’ Participation in E-Commerce Sales Behavior: A Demand Observable Bivariate Probit Model Approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, H. Farmers’ Adoption of Agriculture Green Production Technologies: Perceived Value or Policy-Driven? Heliyon 2024, 10, e23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.; Wu, D. New-Type Professional Farmers: How to Make Use of Different Types of Social Capital to Engage in Agriculture Specialization. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L. Livelihood Sustainability of Rural Households in Response to External Shocks, Internal Stressors and Geographical Disadvantages: Empirical Evidence from Rural China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 27, 18221–18250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei, P.; Gholamrezai, S.; Movahedi, R.; Aliabadi, V. An Analysis of Farmers’ Intention to Use Green Pesticides: The Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior and Health Belief Model. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]