1. Introduction

Insect farming for food and feed production is considered a more sustainable alternative to conventional livestock farming [

1,

2]. Insects have the capacity to bioconvert agri-food by-products and potential waste streams into valuable outputs such as proteins, lipids, chitin, and fertilizers, which promotes the resilience of the food system and aligns with the principles of the circular economy [

3,

4,

5]. In particular, the bioconversion of waste by insects represents an ecosystem service that helps close nutrient loops and contributes to resource efficiency [

6]. Despite this potential, the sector still faces legislative obstacles that limit the use of certain by-products as substrate, although significant regulatory advancements have occurred in recent years [

7]. From an economic perspective, the viability of industrial insect farming depends on reducing production costs while improving process knowledge and efficiency, regardless of the intended application, whether for novel food, protein-reach feed, lipids for feed or biofuel, or fertilizer production [

8]. In the case of

Tenebrio molitor L. (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae), several knowledge gaps persist regarding the optimization of large-scale rearing techniques, diet formulations, and the valorization of its by-products, particularly frass as fertilizers [

9]. Diets represent one of the major variable costs in mealworm production and play a central role in determining the economic sustainability of farming systems [

10].

To develop cost-effective diets, numerous studies have tested various feed ingredients, agri-food by-products, either as single components or in multicomponent formulations, often used in mixtures or as alternatives to wheat bran [

11,

12,

13,

14]. Other research efforts have focused on improving the nutritional quality of the larvae through specific diets. In this regard, the fatty acid composition (such as SFA, PUFA percentages, and n-6/n-3 ratio) was found to be more suitable for foods intended for humans [

15,

16,

17]. Similarly, mealworm flours with higher antioxidant content have been obtained from diets of larvae reared on diets based on orange processing residues, distillery by-products, and former foodstuffs [

18,

19,

20]. However, although lower-cost diets may offer economic advantages, they must still ensure larval growth performance at least equivalent to that of the standard reference diet.

Nutritionally efficient diets for insects are often based on multicomponent formulations, in which different ingredients are combined in proportions that satisfy the target nutrient composition. To achieve this, several researchers have applied the nutritional geometry framework to optimize dietary profiles of

T. molitor [

21] and

Gryllodes sigillatus (Walker) [

22]. Other studies have leveraged the self-selection behavior of certain insect species to preliminarily determine the optimal composition of new diets. Self-selection is the ability of the insect to choose and eat its preferred portion within a mixed feed. This behavior is known in

T. molitor [

23,

24],

Grillus bimaculatus (de Geer) [

25], and

Acheta domesticus L. [

26]. However, self-selection also represents a potential methodological limitation when evaluating mixed diets provided ad libitum in bulk form. On the contrary, the administration of new assembled diets reduces self-selection and facilitates the separation of frass and unconsumed feed, which is essential for accurately calculating of diet efficiency indices [

17,

27,

28].

So far, the physical characteristics of Tenebrionidae’s diet have received limited attention, with the few existing studies focusing primarily on the particle size [

29,

30]. Nonetheless, previous observations have demonstrated that a higher proportion of cracked wheat can positively affect the population growth of

Alphitobius diaperinus (Panzer) [

31]. In several studies on Tenebrionidae, pelleted feed was employed for purposes other than nutritional evaluation, such as reducing dust levels in mealworm farming [

32], standardizing fermented diets [

33], and developing formulations containing mycoinsecticides for the control of

A. diaperinus [

34].

To our knowledge, no comparative studies have evaluated the effects of different physical forms of diet administration, particularly in relation to powdered versus assembled feeds.

The pelletization process is widely used in animal feed production; however, it requires access to specialized industrial facilities. Generally, in laboratory tests, the feed is assembled manually and dried at low temperatures to prevent the degradation of thermolabile nutraceutical compounds. Various techniques have been employed to produce assembled feeds, including “extruded” forms [

28], “short, thin strips” [

27], and “cookies” [

17]. The objectives of this study were to (1) evaluate the influence of ground and assembled feeds (pellets and cookies) on adult productivity, larval performance, and feed efficiency; and (2) compare the effects of crumbled versus powdered chicken feed on adult productivity and larval growth under laboratory conditions, simulating a large-scale production system. A deeper understanding of how feed physical form influences performance could support more precise diet formulation and enhance the efficiency of mass-rearing

T. molitor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Diet Preparation

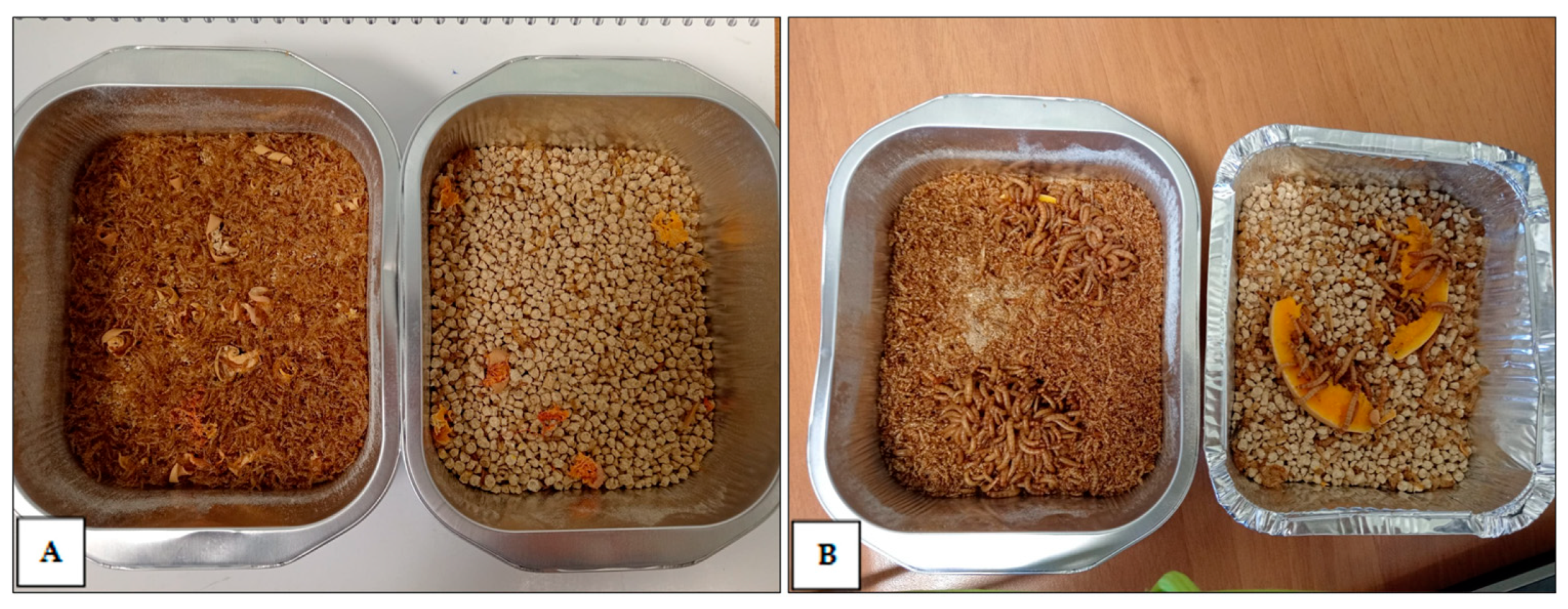

Soft wheat bran (W) and brewer’s spent grain (B) were selected as the two basal substrates tested in two independent trials in the year 2024. Pelleted wheat bran (protein 15.0% on dry matter) was supplied by CESAC s.c.a. (Conselice, RA, Italy), with pellets measuring 8–12 × 6 mm (l × Ø). Pelleted brewer’s spent grain (protein 18.7% on dry matter) was supplied by VIGORI (Kaunas, Lithuania), with pellets measuring 8–15 × 6 mm (l × Ø). For each substrate, four different physical feed forms were prepared by grinding the pellets and sieving them using 2 mm and 0.5 mm mesh manual sieves (Giuliani Tecnologie S.r.l. Torino, TO, Italy). Particles < 0.5 mm (PW) and 0.5–2 mm (GR) were used as ground feed forms, whereas the original unground pellets (PE) represented the assembled feed form. A fourth feed form was obtained by mixing PW and GR in a 50:50 (

w/

w) ratio to produce “cookies” (CO) measuring 10 × 10 × 2 mm (l × w × h), according to the method described by Baldacchino et al. [

17]. The 0.5–2 mm ground fraction was used as a control feed in both the wheat bran and the brewer’s spent grain trials.

A trial was set up in 2025 to test a smaller pellet size. In this trial, crumbled chicken feed (size 2–3 mm; NATURA VERA, Corato, BA, Italy) was used as the assembled feed form, while the same feed was ground and sieved (<0.5 mm) to obtain its powdered form.

2.2. Insect and Experimental Design

Tenebrio molitor L. individuals were obtained from the colony maintained at the insectarium of CIHEAM-Bari (Apulia region, Valenzano, Italy) and reared in a climatic chamber at 28 ± 1 °C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity (RH), and under a 0L:24D photoperiod. The colony was fed ad libitum on wheat bran and yeast (ratio 95:5 w/w), and pumpkin pieces were provided twice a week as a wet source.

Prior to the adult bioassay, pupae were sexed [

35] under a stereoscope (mod. SMZ745T, Nikon Europe B.V., Amstelveen, The Netherlands) and stored separately for sex until adult emergence. Groups of five males and five females (per replicate) were placed in plastic cups (13 × 7 cm, h × Ø) containing 5 g of specific feed form to be tested. Pumpkin was added as a water source two to three times per week. The experimental design included ten replications/feed forms in a completely randomized design. Every ten days for seven consecutive intervals, live adults were counted and transferred to new cups containing fresh feed. Adult productivity was verified on the 30th post-oviposition day by counting the number of live larvae per replicate produced by live females during the specific oviposition time [

36].

Subsequently, the first two oviposition events were used as two blocks to evaluate the performance of the young larvae. For this purpose, four times every 10 days, each replicate was weighed, and the value was divided by the number of live larvae. Additional feed was weighed and provided, when necessary, while 5 g of pumpkin was provided every three days, and any uneaten pumpkin was removed. On the 70th post-oviposition day, the experiment was terminated, and uneaten feed and frass were collected and weighed.

Survival (Equation (1)) and efficiency indices (Equations (2) and (3)) were calculated [

37] using

where FC represent the feed consumption (mg larvae

−1), and WG represents the larval gained weight at the end of the experiment;

For the third test, groups of 100 adults per replicate were placed in trays (9 × 11 cm) containing 100 g of specific feed form. The experimental design consisted of ten replicates per feed form in a completely randomized design. Adults were allowed to oviposit for seven days and then removed from the trays. On the 60th and 90th days after oviposition, the influence of feed form was verified by counting the number of live larvae, the larval weight, and the larval biomass.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to homogeneity and normality tests. When these criteria were satisfied, a one-way ANOVA, repeated-measures ANOVA, and Tukey–Kramer HDS test post hoc were applied. When the criteria were not met, the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by pairwise multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction was used. The t-test was applied to the data from the third trial to compare the two chicken feed forms. Significance was assumed at p < 0.05. Data were statistically analyzed using SSPS software version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft® Excel® for Microsoft 365 MSO.

4. Discussion

One technique for rearing mealworms involves the oviposition of adults into feeding trays where the larvae subsequently develop [

38]. Therefore, our study addressed the practical need to evaluate different feed forms administered during the oviposition phase.

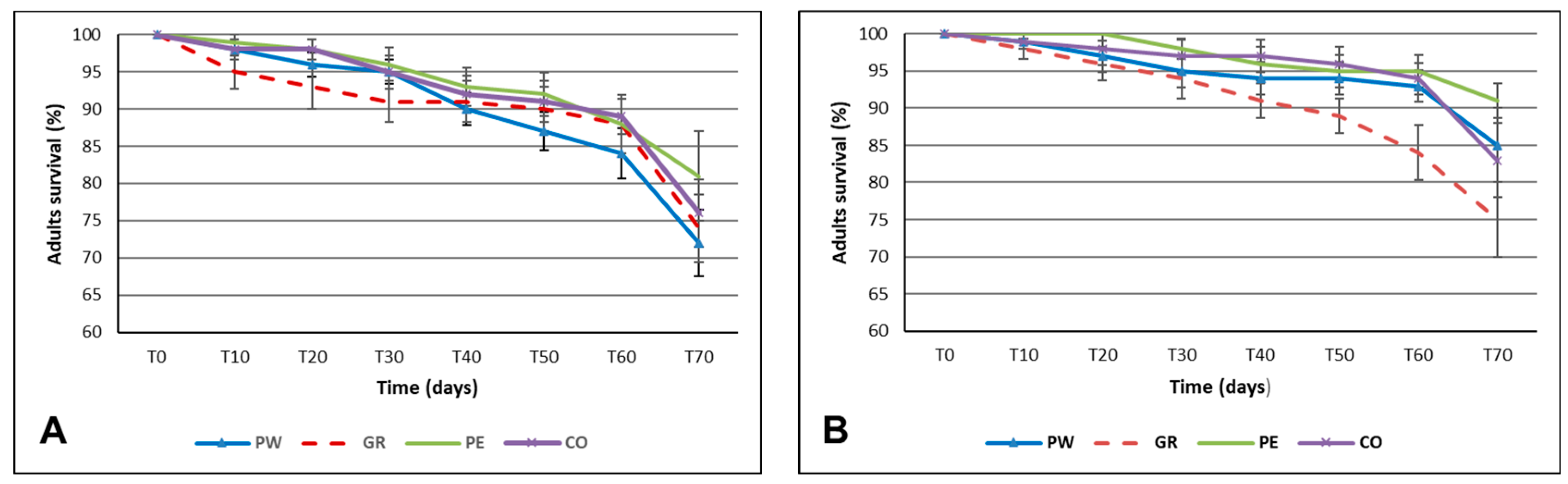

Our results consistently demonstrated that adult survival was not affected by the different feed forms for any of the three feeds tested.

Productivity was higher in ground (PW and GR) than in assembled (PE and CO) feeds, both for wheat bran and brewer’s spent grain. This result was also confirmed by the third test, which compared powdered and crumbled chicken feed.

In previous studies, adult productivity of

T. molitor was investigated by comparing different feeds and their mixtures, whereas evaluations of the influence of the feed forms are lacking [

39,

40,

41].

In our experiments, productivity was assessed as the number of young larvae produced per female. However, this method is based on the direct correlation between the number of eggs produced and the number of larvae [

36]. This represents a practical approach for production purposes but does not allow for the determination of the effects on oviposition or egg-larva survival. Oviposition is known to be negatively affected by low diet quality [

42] and high adult density [

43]. However, these influences should have been absent in our study, since the different feed forms were obtained from the same pelleted feed, and adult density was kept constant across feed forms. Egg loss can be caused by adult cannibalism, which, together with larval cannibalism of pupae, leads to reduced productivity in rearing farms [

44,

45,

46]. Egg cannibalism is favored with high adult density and longer residence times in the oviposition trays [

36]. To reduce egg loss due to cannibalism, density-to-oviposition times ratios were optimized [

44]. Nevertheless, we believe that the number of viable eggs in our study is lower than that under optimal oviposition conditions. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the influence of particle size or feed form on cannibalism, so we can only hypothesize that eggs laid on aggregate feed are more easily identified and consumed by adults, and more susceptible to external environmental conditions and microorganisms. Compared with this hypothesis, we consider it more likely that ground feed enhances the survival of newly hatched larvae, which may have greater difficulty feeding on larger or aggregated feeds. However, this difficulty should occur within the first week of life, since survival did not differ when using 5-day-old larvae on milled bran of different sizes [

30]. The initially lower access to the aggregated feed is supported by our results on the survival and weight of young larvae. Both the number of live larvae and their weight were significantly and consistently lower in aggregate feed than in ground feed. Although our experiments compared feed forms rather than feed types, this result was consistently observed at each oviposition in wheat bran and in brewer’s spent grain (larvae one month old), as well as in chicken feed (larvae two months old). These findings agree with Zhong et al. [

47], who demonstrated greater cumulative consumption of smaller-sized microplastics by one-month-old mealworms compared to larger-sized microplastics.

After 30–70 days from oviposition, the different wheat bran feed forms did not affect larval survival or weight gain, except for the lower performance observed with the feed assembled in “cookie” form. In brewer’s spent grain, survival was unaffected, while larval weight was lower in both assembled forms up to day 50. Subsequently, the results showed a different growth pattern: larvae were lighter in PW and CO than in GR (control), while the weight of those fed PE was not significantly different from that of those fed GR (at day 70). This change in performance between powdered and pelleted feeds was also confirmed by the weight recovery of larvae fed with crumbled chicken feed between the 60

th and 90

th day. The possible different influence of the feed agrees with observations made with equal particle sizes in previous studies on

T. molitor [

29]. Our results confirm the general suitability of ground feed (particle size of 0.5–2 mm) and support the hypothesis that larger larvae can feed on larger particles. This hypothesis is also supported by the better weight gain observed for finer feed in small

A. diaperinus larvae compared to larger

T. molitor larvae [

30]. The relationship between insect size and feed particle size has also been shown in

A. domesticus, with development positively correlated between strains of different sizes and the size of the feed provided [

48]. In

Teleogryllus occipitalis (Audinet-Serville), a granular diet promoted better growth than a powdery one [

49], and in choice tests,

G. sigillatus preferentially consumed particles of 1.0–1.4 mm compared to smaller particles [

50]. Furthermore, previous authors have suggested that these effects are limited to the early growth period, since final results tend to be the same, in agreement with our results for crumbed chicken feed [

30,

50]. Therefore, assembled feeds (pellet, cookie, and crumble) can be initially equated to large particles, although some factors (such as feed type, compactness, and hygroscopicity) and the pelletizing process affect their integrity over time [

51].

The FCR and ECI efficiency indices were similar between wheat bran feed forms and aligned with those detected in milled bran by Bailota et al. [

30]. Conversely, the brewer’s spent grain showed higher FCR values (therefore lower efficiency) when pulverized and assembled into cookies. The cause of this could be the greater presence of raw fiber and lignin (fragments of glumes) in the brewer’s spent grain compared to the wheat bran [

52], which, if ingested, can reduce digestibility [

53]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the larvae do not select but ingest the too small fragments of glume present in the pulverized feed, as already verified with cellulose [

54]. Similarly, the larvae would ingest the small fragments incorporated into the cookies, since these were assembled with 50% feed particles smaller than 0.5 mm. In contrast, larvae can self-select ground feed (0.5–2 mm) and later also select disintegrated pellets.

Unfortunately, the lack of previous studies on assembled feed does not allow for a further comparison of our results, and many knowledge gaps remain.

Thus, our results provide important input for optimizing the feed administration format in T. molitor farming. Hypothetically, a new diet formulation could include a mixed portion of ground and powdered feed (essential during the oviposition and development of newborn larvae) and a portion of assembled feed as pellet/crumble (usable by larvae one to two months old). In this case, specific studies would be necessary to test its effectiveness. The results obtained also contribute to improving experimental methodologies aimed at verifying the efficiency of multicomponent diets, administered in assembled form to avoid self-selection. In this case, assembled diets should be tested on growing larvae (40–60 days old), avoiding the use of younger or newborn larvae.