A Method for Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics: A Case Study of Bishan District

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Pre-Processing

2.2.1. Sample Points Data

2.2.2. Sentinel-2 Data

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Construction of Standard NDVI Time Series for Major Land-Cover Types

2.3.2. Time-Series Curve Similarity Measurement Based on Euclidean Distance

2.3.3. Selection of Curve Similarity Threshold and Determination of Extreme-Value Constraint

2.3.4. Accuracy Assessment Method

3. Results Analysis

3.1. Image Reconstruction After Cloud Removal

3.2. Characteristics of Standard NDVI Time-Series Curves for Typical Land-Cover Types

3.3. Establishment of Extraction Threshold and Extreme-Value Constraint

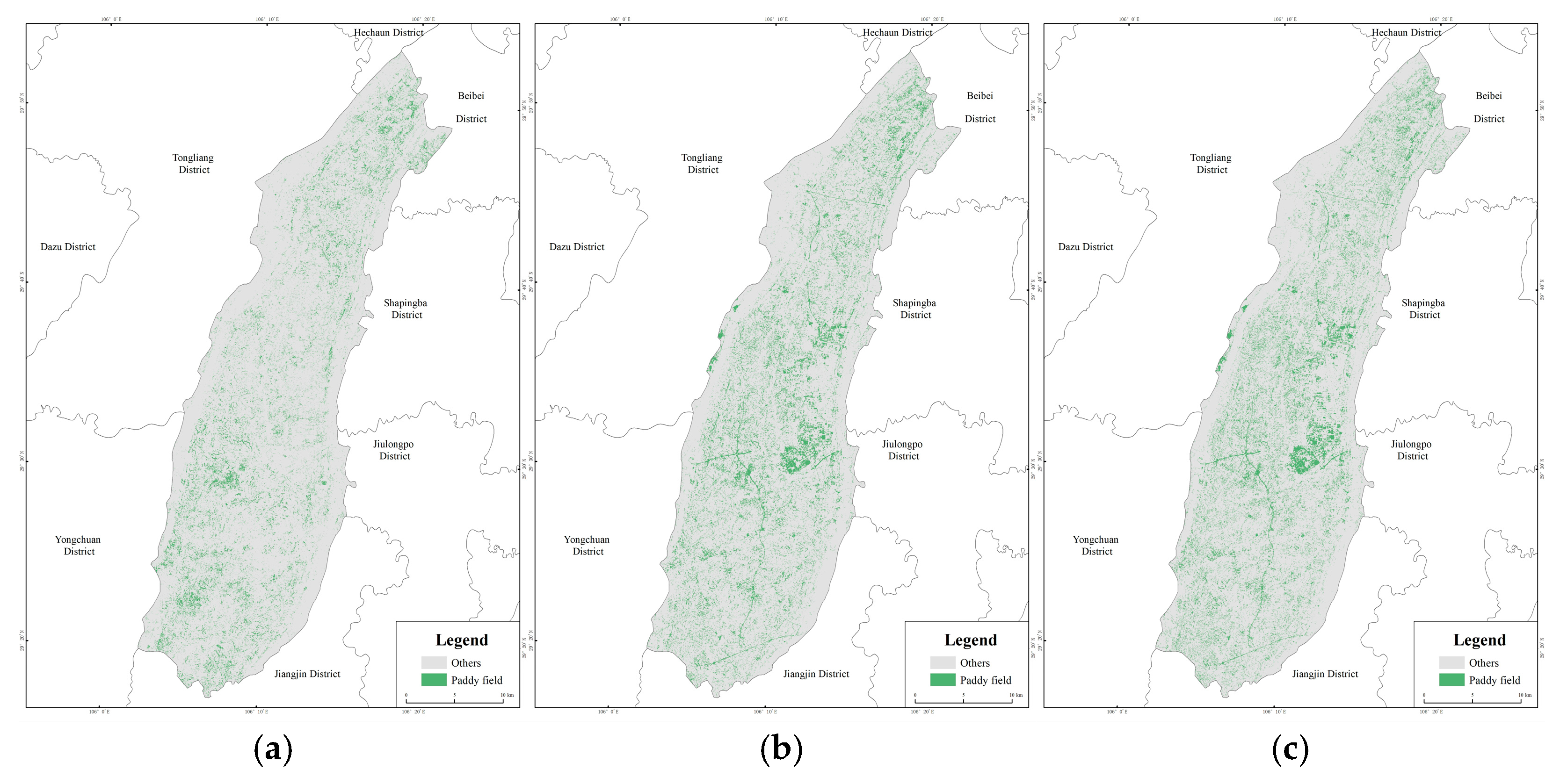

4. Comparison and Analysis of Methods

4.1. Alternative Extraction Methods for Comparison

4.2. Accuracy Assessment

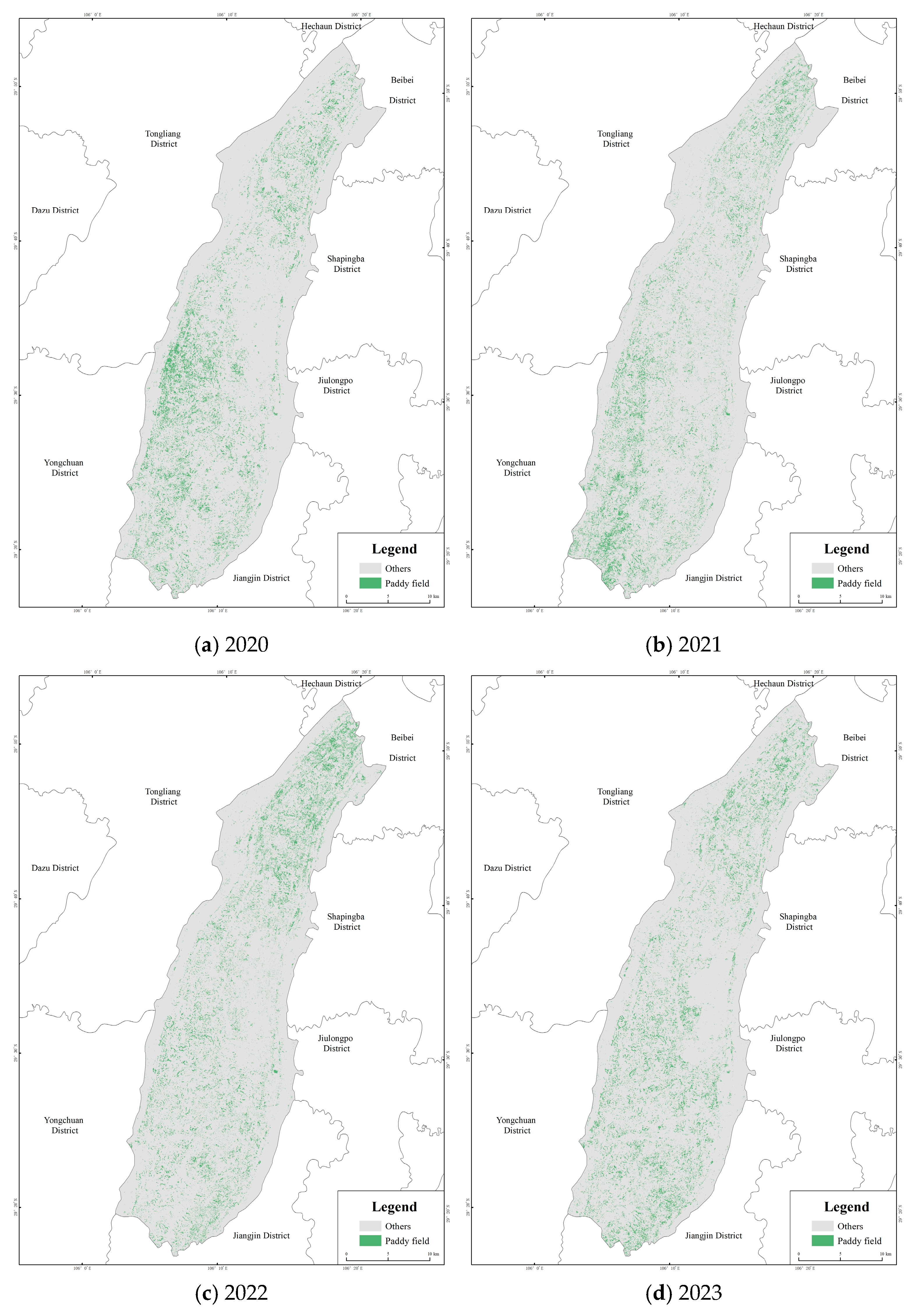

4.3. Multi-Annual Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics (2020–2023)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- (1)

- Influence of External Factors

- (2)

- Influence of Data Sources

- (3)

- Insufficient Accuracy Assessment

- (4)

- Analysis of the Differences Between Remote Sensing Estimates and Statistical Data

- (5)

- Spatial and Temporal Transferability of the Method

- (6)

- Limitations of the Threshold Determination Approach

5.2. Conclusions

- (1)

- Paddy fields exhibit distinct NDVI time-series patterns that differentiate them from other land-cover types. These characteristic temporal dynamics, captured through Euclidean distance analysis, allow for effective identification of paddy fields.

- (2)

- A systematic evaluation of paddy field classification results from 2020 to 2024 was conducted using multiple accuracy metrics. The results showed that the OA and Kappa coefficient consistently remained at high levels, while the F1-score was stable above 0.8, indicating that the classification results achieved a reliable balance between precision and recall. Further bootstrap-based uncertainty analysis revealed that the confidence intervals of all metrics were relatively narrow, confirming the robustness and statistical reliability of the results. Overall, the proposed method demonstrated excellent classification performance for paddy field extraction and significantly outperformed traditional machine learning methods implemented on the GEE platform.

- (3)

- This study proposed a strategy of “threshold interval setting combined with iterative validation within the interval,” further integrated with extreme-range constraints, to address both spatiotemporal variability and mixed-pixel issues in threshold determination. Specifically, the upper threshold ensured effective discrimination between paddy fields and other land-cover types, the lower threshold mitigated the influence of phenological variations and temporal shifts, and the extreme-range constraint further eliminated anomalous pixels with small absolute differences. This combined approach effectively enhanced the robustness and accuracy of paddy field extraction.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, S.; Zhu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Duan, M.; Qiu, B.; Wan, L.; Tan, X.; Xu, Y.N.; Cao, R. A robust index to extract paddy fields in cloudy regions from SAR time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 285, 113374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Food Balance Sheets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, B.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, R.; Ye, T.; Zhao, W.; Dong, J.; Ma, H.; Yuan, W. High-resolution distribution dataset of double-season paddy rice in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnoun Hosseini, M.; Valadan Zoej, M.J.; Taheri Dehkordi, A.; Ghaderpour, E. Cropping intensity mapping using temporal transfer of a stacked ensemble machine learning model within Google Earth Engine. Geocarto Int. 2024, 39, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdali, E.; Valadan Zoej, M.J.; Taheri Dehkordi, A.; Ghaderpour, E. A parallel-cascaded ensemble of machine learning models for crop type classification in Google Earth Engine using multi-temporal Sentinel-1/2 and Landsat-8/9 data. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Li, Y.; Shen, R.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, B.; Yuan, W.; Li, J.; Zhuo, L. Large-scale and high-resolution paddy rice intensity mapping using downscaling and phenology-based algorithms on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Dong, J.; Liao, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z.; You, N.; Li, Z.; Fu, P. Examining rice distribution and cropping intensity in a mixed single- and double-cropping region in South China using all available Sentinel-1/2 images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 101, 102351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, N.; Dong, J.; Huang, J.; Du, G.; Zhang, G.; He, Y.; Yang, T.; Di, Y.; Xiao, X. The 10-m crop type maps in Northeast China during 2017–2019. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, R.; Tian, J.; Li, X.; Yin, D.; Li, J.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Wu, D. An enhanced pixel-based phenological feature for accurate paddy rice mapping with Sentinel-2 imagery in Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; You, S.; Liu, A.; Li, P.; Zhang, J.; Deng, J. High-resolution national-scale mapping of paddy rice based on Sentinel-1/2 data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Remote Sensing Image Identification and Monitoring of Rice Planting Areas in the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau Based on the GEE Platform. Master’s Thesis, Yunnan Normal University, Kunming, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fatchurrachman; Rudiyanto; Che Soh, N.; Mohd Shah, R.; Goh Eng Giap, S.; Indra Setiawan, B.; Minasny, B. High-resolution mapping of paddy rice extent and growth stages across Peninsular Malaysia using a fusion of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 time series data in Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Remote Sensing Classification Mapping of Major Grain Crops in Heilongjiang Province. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, K.R.; Drajat, D. Deep machine learning with Sentinel satellite data to map paddy rice production stages across West Java, Indonesia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 265, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Zhu, W.; Li, N. An automated rice mapping method based on flooding signals in synthetic aperture radar time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 252, 112112. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, L.; Fujita, G.; Kito, K.; Miyashita, T. Historical mapping of rice fields in Japan using phenology and temporally aggregated Landsat images in Google Earth Engine. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2022, 191, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Lou, Y.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, L. Spatial domain transfer: Cross-regional paddy rice mapping with a few samples based on Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 data on GEE. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Li, R.; Qiu, J.; Han, Y.; Han, D.; Chen, M.; Chi, H. Large-scale mapping of new mixed rice cropping patterns in southern China with a phenology-based algorithm and MODIS dataset. Paddy Water Environ. 2023, 21, 243–261. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, X. Large-scale rice mapping based on Google Earth Engine and multi-source remote sensing images. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2023, 51, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Tian, Y.; Wan, W.; Yuan, C.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y. Research on the temporal and spatial changes and driving forces of rice fields based on the NDVI difference method. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, W.; He, T.; Tian, F.; Zhang, F. A comprehensive review of rice mapping from satellite data: Algorithms, product characteristics, and consistency assessment. Sci. Remote Sens. 2024, 10, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickensdörfer, L.; Schwieder, M.; Pflugmacher, D.; Nendel, C.; Erasmi, S.; Hostert, P. Mapping of crop types and crop sequences with combined time series of Sentinel-1, Sentinel-2, and Landsat 8 data for Germany. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, C.; Valero, S.; Inglada, J.; Champion, N.; Marais Sicre, C.; Dedieu, G. Effect of training class label noise on classification performances for land cover mapping with satellite image time series. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tian, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, K. Research on rice fields extraction by NDVI difference method based on Sentinel data. Sensors 2023, 23, 5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S. Study on Pesticide Application Behavior of Vegetable Farmers in Bishan District, Chongqing. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 21010-2017; Current Land Use Classification. Drafting organizations: China Land Surveying and Planning Institute and Department of Surveying and Monitoring, Ministry of Natural Resources: Beijing, China, , 2017.

- Song, M.; Xu, L.; Ge, J.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, L.; Jiang, J.; Ding, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wu, F. EARice10: A 10 m resolution annual rice distribution map of East Asia for 2023. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Peng, B.; Ye, H. An automatic cloud detection model for Sentinel-2 imagery based on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chi, H.; Huang, J.; Han, Y.; Li, Y.; Ling, F. Comparison of cloud-mask algorithms and machine-learning methods using Sentinel-2 imagery for mapping paddy rice in Jianghan Plain. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1305. [Google Scholar]

- Roßberg, T.; Schmitt, M. Comparing the relationship between NDVI and SAR backscatter across different frequency bands in agricultural areas. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 319, 114612. [Google Scholar]

- ESA. Sentinel-2 Product Specification: Level-2A Input/Output Data Definition Document (S2-PDGS-MPC-L2A-IODD-2.9). Eur. Space Agency 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, G.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Q. Extraction of rice remote sensing information using a time-series similarity method based on DTW distance: A case study of Thailand. Resour. Sci. 2014, 36, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S. Phenology-assisted supervised paddy rice mapping with Landsat imagery on Google Earth Engine: Experiments in Heilongjiang Province of China from 1990 to 2020. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Nendel, C.; Hostert, P. Intra-annual reflectance composites from Sentinel-2 and Landsat for national-scale crop and land cover mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 220, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Gao, P.; Tian, B.; Wu, C.; Mu, X. Spatio-temporal patterns of NDVI and its influencing factors based on the ESTARFM in the Loess Plateau of China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Liu, Q. Mapping rice cropping systems in Vietnam using an NDVI-based time-series similarity measurement based on DTW distance. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Li, J. An algorithm for rice information extraction using morphological similarity. Remote Sens. Inf. 2020, 35, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, G. Extraction method of rice planting structure in tropical regions based on Sentinel-1 time-series characteristics. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 177–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Study on Extraction of Rice–Crayfish Fields in Cloudy Southern China Based on the GEE Platform. Master’s Thesis, East China University of Technology, Nanchang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhan, M.A.; Reich, R.M.; Czaplewski, R.L. Variance estimates and confidence intervals for the Kappa measure of classification accuracy. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1997, 23, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, F.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.; Leng, P.; Duan, S.; Ren, J. A new method for winter wheat mapping based on spectral reconstruction technology. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Nishina, K.; Kawaguchi Akitsu, T.; Jiang, L.; Masutomi, Y.; Nishida Nasahara, K. Feature-based algorithm for large-scale rice phenology detection based on satellite images. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 329, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, T.; Chen, S.; Li, Z.; Sun, R. Concurrent precipitation extremes modulate the response of rice transplanting date to preseason temperature extremes in China. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF002888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, W.; Ran, W.; Yang, H.; Liang, Z.; Tong, X.; Sun, B. Effects of natural rainfall characteristics and crop cover on runoff and sediment yield of purple soil sloping farmland in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 137–146. [Google Scholar]

| Forest and Grassland | Dryland | Construction Land | Water Bodies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apr-M | 0.232 | 0.234 | 0.047 | 0.109 |

| Apr-L | 0.273 | 0.253 | 0.022 | 0.091 |

| May-E | 0.190 | 0.180 | 0.058 | 0.107 |

| May-M | 0.234 | 0.166 | 0.144 | 0.256 |

| May-L | 0.135 | 0.098 | 0.241 | 0.349 |

| Jul-L | 0.008 | 0.084 | 0.413 | 0.445 |

| Aug-L | 0.292 | 0.135 | 0.114 | 0.223 |

| Sept-M | 0.219 | 0.094 | 0.110 | 0.187 |

| Sept-L | 0.278 | 0.066 | 0.148 | 0.262 |

| Oct-E | 0.266 | 0.141 | 0.133 | 0.191 |

| Oct-M | 0.230 | 0.146 | 0.183 | 0.225 |

| Oct-L | 0.142 | 0.082 | 0.163 | 0.221 |

| The sum of the differences | 2.499 | 1.679 | 1.776 | 2.666 |

| Time Period | Average Deviation |

|---|---|

| Apr-M | 0.058 |

| Apr-L | 0.016 |

| May-E | 0.013 |

| May-M | 0.075 |

| May-L | 0.06 |

| Jul-L | 0.073 |

| Aug-L | 0.041 |

| Sept-M | 0.042 |

| Sept-L | 0.047 |

| Oct-E | 0.085 |

| Oct-M | 0.089 |

| Oct-L | 0.092 |

| The sum of the differences | 0.691 |

| Method | Overall Accuracy | Kappa Coefficient |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI time-series characteristics | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| RF | 0.9 | 0.69 |

| CART | 0.9 | 0.69 |

| Year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curve Similarity Threshold | 1.5 | 1.24 | 1.55 | 1.03 |

| Extreme-Value Constraint | 0.438 | 0.291 | 0.261 | 0.264 |

| Year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer’s Accuracy | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.98 |

| User’s Accuracy | 0.86 | 0.79 | 0.8 | 0.81 |

| Overall Accuracy | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Kappa Coefficient | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| F1-score | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.89 |

| Year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer’s Accuracy | 0.94–0.99 | 0.92–0.98 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.96–1.00 |

| User’s Accuracy | 0.82–0.90 | 0.75–0.84 | 0.76–0.85 | 0.77–0.86 | 0.73–0.82 |

| Overall Accuracy | 0.93–0.96 | 0.90–0.94 | 0.91–0.94 | 0.92–0.95 | 0.90–0.94 |

| Kappa Coefficient | 0.83–0.91 | 0.76–0.85 | 0.79–0.87 | 0.80–0.88 | 0.77–0.85 |

| F1-score | 0.89–0.94 | 0.83–0.90 | 0.85–0.91 | 0.86–0.92 | 0.83–0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, C.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Tian, J.; Wan, W. A Method for Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics: A Case Study of Bishan District. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222321

Yuan C, Tian Y, Huang Y, Tian J, Wan W. A Method for Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics: A Case Study of Bishan District. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222321

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Chenxi, Yongzhong Tian, Ye Huang, Jinglian Tian, and Wenhao Wan. 2025. "A Method for Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics: A Case Study of Bishan District" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222321

APA StyleYuan, C., Tian, Y., Huang, Y., Tian, J., & Wan, W. (2025). A Method for Paddy Field Extraction Based on NDVI Time-Series Characteristics: A Case Study of Bishan District. Agriculture, 15(22), 2321. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222321