Transcriptomic and Physiological Insights into the Role of Nano-Silicon Dioxide in Alleviating Salt Stress During Soybean Germination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Preliminary Screening and Biostimulant Selection

| Product | Concentration | Company (City, Country) | Particle Size | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano-scale zinc oxide (NP-ZnO) | 100 mg/L | Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) | <50 nm | [21,22,23] |

| Nano-scale silicon dioxide (NP-SiO2) | 100 mg/L | Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) | 10–20 nm | [24,25] |

| Micro-scale silicon dioxide (SiO2) | 100 mg/L | Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) | 0.5–10 μm | [26] |

| Glucose (Glu) | 2.5 mM | Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA) | - | [27,28] |

| Humic acid (HA) | 2.5 mM | Daejung (Siheung, Republic of Korea) | - | [29,30] |

| Fulvic acid (FA) | 2.5 mM | RNM (Busan, Republic of Korea) | - | [31] |

2.3. Germination Parameters

- (a)

- GP was calculated in accordance with the process outlined by Alsaeedi et al. using Equation (1) [32]:

- (b)

- GI was computed to reflect both the speed and uniformity of seed germination based on daily germination data using Equation (2) [33]:where ni indicates the number of seeds that germinated on a given day i and di corresponds to the number of days since sowing.

- (c)

- Radicle length was determined by selecting five germinated seeds with similar growth conditions and calculating the average radicle length.

2.4. Antioxidant Enzyme Activity Analysis

2.5. Lipid Peroxidation Assays

2.6. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effects of the Biostimulants on Germination Under Control (0 mM NaCl) and Salt-Stress (150 mM NaCl) Conditions

3.2. Effects of NP-SiO2 Dosage on Soybean Germination Under Control (0 mM NaCl) and Salt-Stress (150 mM NaCl) Conditions

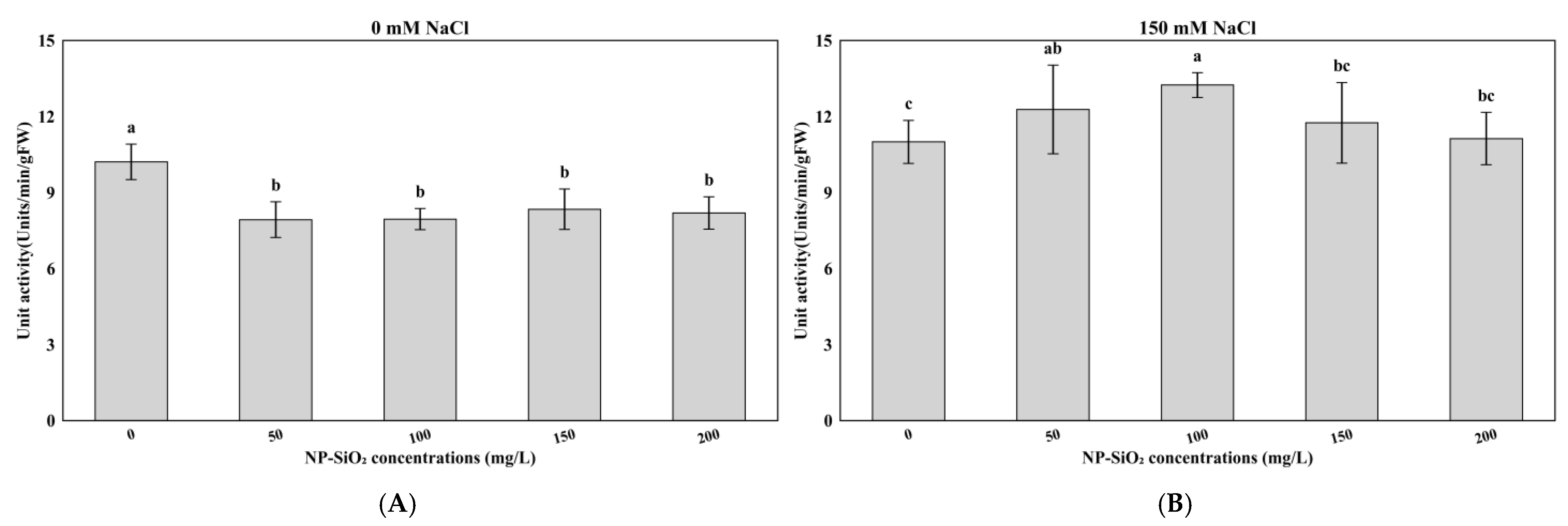

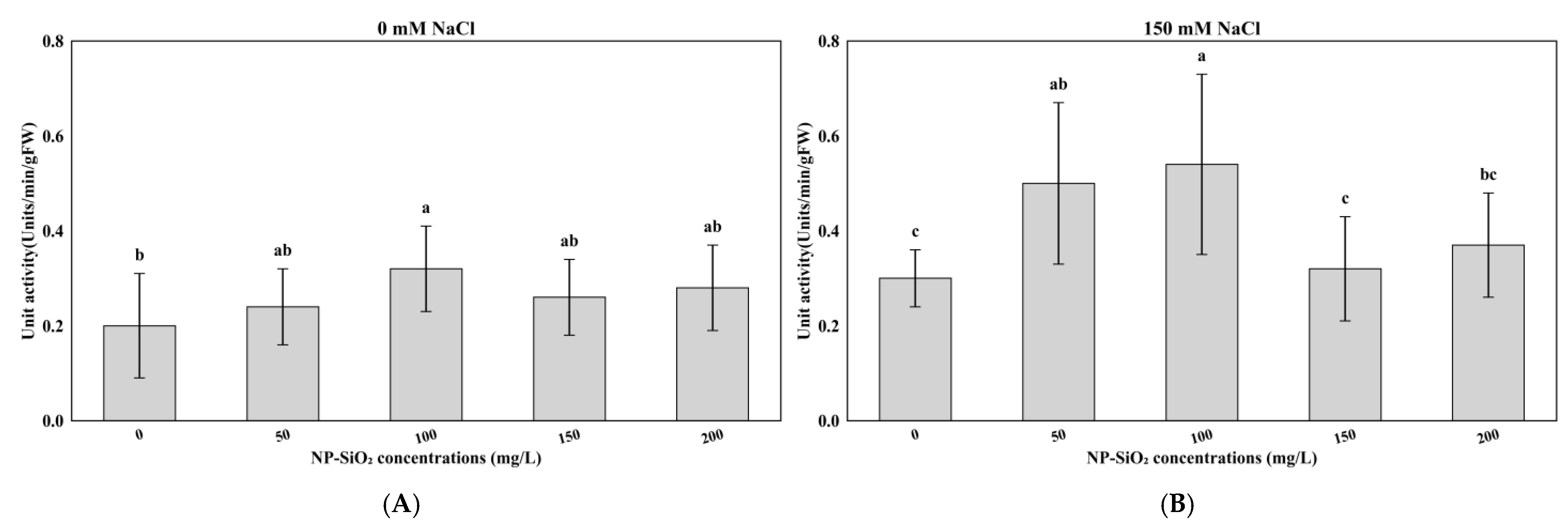

3.3. Effects of NP-SiO2 on POD, APX, and CAT Activity Under Control and Salt-Stress Conditions

3.4. Effects of NP-SiO2 on Malondialdehyde (MDA) Levels Under Control and Salt-Stress Conditions

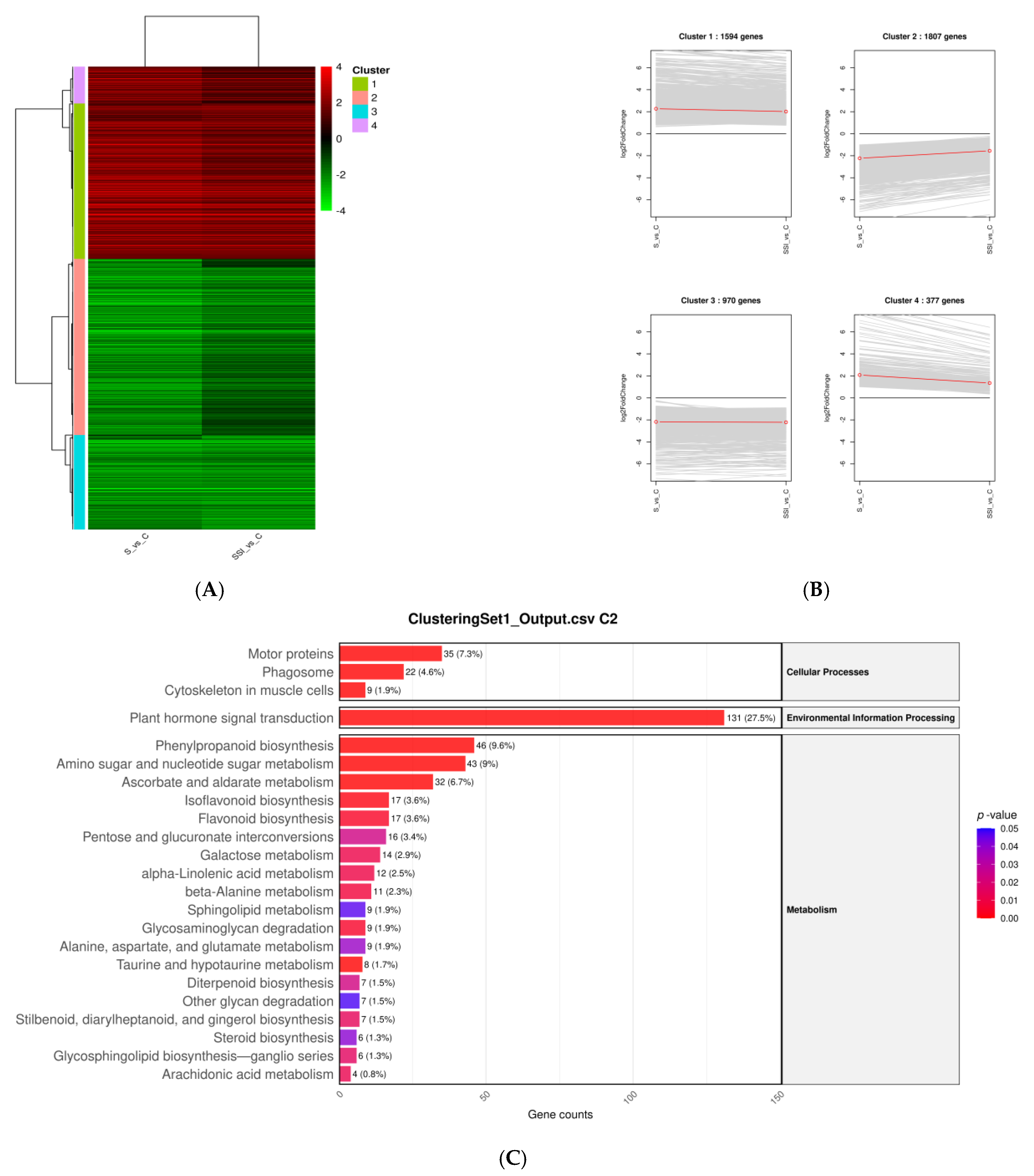

3.5. Overview of Transcriptome Profiling and Functional Analysis

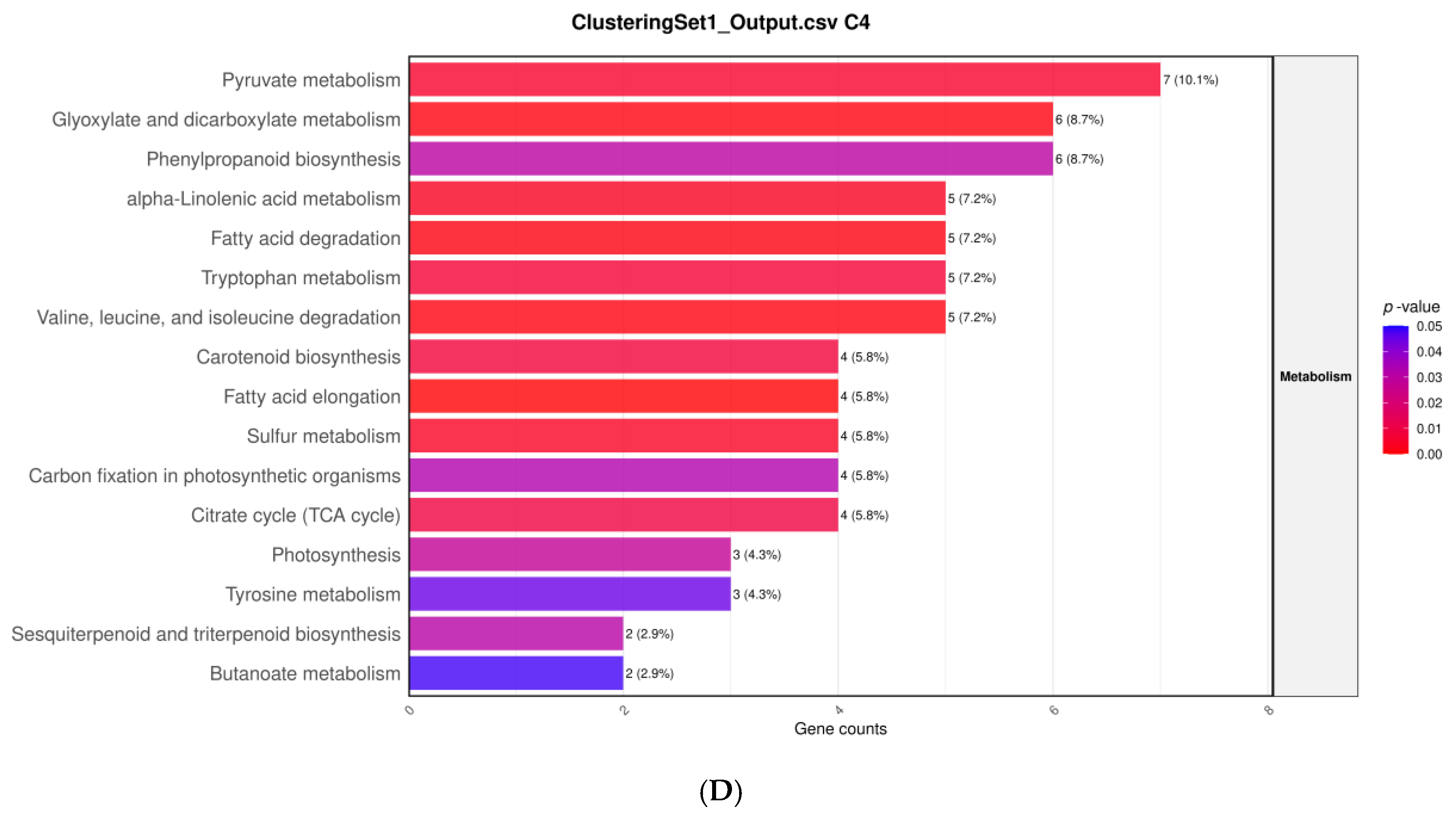

3.6. Hierarchical Clustering of DEGs Under Salt Stress and NP-SiO2 Treatment

3.7. Differential Expression of Hormone-Related Genes and Their Roles in Salt Tolerance Under NP-SiO2 Treatment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| CK | Cytokinin |

| BR | Brassinosteroid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| GP | Germination percentage |

| GI | Germination index |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| Glu | Glucose |

| HA | Humic acid |

| FA | Fulvic acid |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

References

- FAO. FAO Launches First Major Global Assessment of Salt-Affected Soils in 50 Years. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/fao-launches-first-major-global-assessment-of-salt-affected-soils-in-50-years/en (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Balasubramaniam, T.; Shen, G.; Esmaeili, N.; Zhang, H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants 2023, 12, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, X.; Bo, X.; Li, S.; Shang, M.; Chen, F.; Chu, Q. Modeling climatically suitable areas for soybean and their shifts across China. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Sun, L.; Jiang, S.; Ren, H.; Sun, R.; Wei, Z.; Hong, H.; Luan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Soybean genetic resources contributing to sustainable protein production. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 4095–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidian, P.; Ghorbani, H.R.; Farajpour, M. Achieving agricultural sustainability through soybean production in Iran: Potential and challenges. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awan, S.A.; Khan, I.; Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Tan, X.; Yang, F. Pre-treatment of melatonin enhances the seed germination responses and physiological mechanisms of soybean (Glycine max L.) under abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1149873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yang, Y. How Plants Tolerate Salt Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5914–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, K.; Mondal, S.; Gorai, S.; Singh, A.P.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, T.; Roy, A.; Hembram, S.; Gaikwad, D.J.; Mondal, S.; et al. Impacts of salinity stress on crop plants: Improving salt tolerance through genetic and molecular dissection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1241736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shani, M.Y.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Butt, A.K.; Abbas, S.; Nasif, M.; Khan, Z.; Mauro, R.P.; Cannata, C.; Gul, N.; Ghaffar, M.; et al. Potassium Nutrition Induced Salinity Mitigation in Mungbean [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] by Altering Biomass and Physio-Biochemical Processes. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Rashmi, R.; Surya Ulhas, R.; Sudheer, W.N.; Banadka, A.; Nagella, P.; Aldaej, M.I.; Rezk, A.A.-S.; Shehata, W.F.; Almaghasla, M.I. The role of nanoparticles in response of plants to abiotic stress at physiological, biochemical, and molecular levels. Plants 2023, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, H.; Waqas, M.; Nawaz, A.; Naz, S.; Ali, S.; Ejaz, S.; Ahmad, R.; Ghfar, A.A.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Abou Fayssal, S. Amendment of Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) Grown in Calcareous Soil with Spent Mushroom Substrate-derived Biochar: Improvement of Morphological, Biochemical, Qualitative Attributes, and Antioxidant Activities. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2025, 25, 2244–2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Raihan, M.R.H.; Masud, A.A.C.; Rahman, K.; Nowroz, F.; Rahman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and antioxidant defense in plants under salinity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesawat, M.S.; Satheesh, N.; Kherawat, B.S.; Kumar, A.; Kim, H.-U.; Chung, S.-M.; Kumar, M. Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species during Salt Stress in Plants and Their Crosstalk with Other Signaling Molecules—Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Plants 2023, 12, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, U. Plant biostimulants: Definition and overview of categories and effects: HS1330, 5/2019; Horticultural Sciences Department, UF/IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Saeed, K.; Khan, I. Nanoparticles: Properties, applications and toxicities. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Anayatullah, S.; Irfan, E.; Hussain, S.M.; Rizwan, M.; Sohail, M.I.; Jafir, M.; Ahmad, T.; Usman, M.; Alharby, H.F. Nanoparticles assisted regulation of oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme system in plants under salt stress: A review. Chemosphere 2023, 314, 137649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Širić, I.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Al-Shahari, E.A.; Alsudays, I.M.; Bachheti, A.; Goala, M.; Abou Fayssal, S.; Kumar, P.; et al. Impact of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle and liquid leachate of mushroom compost on agronomic and biochemical response of marigold (Tagetes erecta L.) under saline stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 43731–43742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lorente, S.E.; Martí-Guillén, J.M.; Pedreño, M.Á.; Almagro, L.; Sabater-Jara, A.B. Higher Plant-Derived Biostimulants: Mechanisms of Action and Their Role in Mitigating Plant Abiotic Stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Lee, D.H.; Choi, S.; Yang, J.-Y.; Jung, K.; Jeong, J.; Oh, J.H.; Lee, J.H. Skin Sensitization Potential and Cellular ROS-Induced Cytotoxicity of Silica Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdiglesias, V.; Touzani, A.; Ramos-Pan, L.; Alba-González, A.; Folgueira, M.; Moreda-Piñeiro, J.; Méndez, J.; Pásaro, E.; Fernández-Bertólez, N.; Laffon, B. Cytotoxic Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Human Glial Cells. Mater. Proc. 2023, 14, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Asmat-Campos, D.; López-Medina, E.; Montes de Oca-Vásquez, G.; Gil-Rivero, E.; Delfín-Narciso, D.; Juárez-Cortijo, L.; Villena-Zapata, L.; Gurreonero-Fernández, J.; Rafael-Amaya, R. ZnO Nanoparticles Obtained by Green Synthesis as an Alternative to Improve the Germination Characteristics of L. esculentum. Molecules 2022, 27, 2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stałanowska, K.; Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Okorski, A.; Lahuta, L.B. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Affect Early Seedlings’ Growth and Polar Metabolite Profiles of Pea (Pisum sativum L.) and Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bharati, R.; Kubes, J.; Popelkova, D.; Praus, L.; Yang, X.; Severova, L.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles application alleviates salinity stress by modulating plant growth, biochemical attributes and nutrient homeostasis in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Long, H.; Mao, S.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yan, G. Silicon Nanoparticles Improve Tomato Seed Germination More Effectively than Conventional Silicon under Salt Stress via Regulating Antioxidant System and Hormone Metabolism. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avestan, S.; Ghasemnezhad, M.; Esfahani, M.; Byrt, C.S. Application of Nano-Silicon Dioxide Improves Salt Stress Tolerance in Strawberry Plants. Agronomy 2019, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, R.A.; Hazem, M.M.; El-Assar, A.E.-M.; Saudy, H.S.; El-Sayed, S.M. Efficacy of nano-silicon extracted from rice husk to modulate the physio-biochemical constituents of wheat for ameliorating drought tolerance without causing cytotoxicity. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 13, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Guo, S.; Chen, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Shu, S. Enhancement of salt-stressed cucumber tolerance by application of glucose for regulating antioxidant capacity and nitrogen metabolism. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2019, 100, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, G.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Ma, D.; Zhang, D.; Hao, D.; Hu, Z.; Yu, D. Association mapping of soybean seed germination under salt stress. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 290, 2147–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçtürk, R.; Maıwan, N.; Tunçtürk, M. Effect of Humic Acid Applications on Physiological and Biochemical Properties of Soybean (Glycine max L.) Grown under Salt Stress Conditions. Yuz. Yıl Univ. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Saidimoradi, D.; Ghaderi, N.; Javadi, T. Salinity stress mitigation by humic acid application in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.). Sci. Hortic. 2019, 256, 108594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesmin, A.; Anh, L.H.; Mai, N.P.; Khanh, T.D.; Xuan, T.D. Fulvic acid improves salinity tolerance of rice seedlings: Evidence from phenotypic performance, relevant phenolic acids, and momilactones. Plants 2023, 12, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaeedi, A.; Elgarawany, M.; El-Ramady, H.; Alshaal, T.; Al-Otaibi, A. Application of silica nanoparticles induces seed germination and growth of cucumber (Cucumis sativus). Met. Environ. Arid. Land Agric. Sci 2019, 28, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mudaris, M. Notes on various parameters recording the speed of seed germination. Der Tropenlandwirt-J. Agric. Trop. Subtrop. 1998, 99, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Maehly, A.C. The Assay of Catalases and Peroxidases. In Methods of Biochemical Analysis; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1954; pp. 357–424. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen Peroxide is Scavenged by Ascorbate-specific Peroxidase in Spinach Chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts: I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taulavuori, E.; Hellström, E.K.; Taulavuori, K.; Laine, K. Comparison of two methods used to analyse lipid peroxidation from Vaccinium myrtillus (L.) during snow removal, reacclimation and cold acclimation. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2375–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, P.; Nelson, L.; Kloepper, J.W. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 3–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.; Ali, M.; Qadir, M.; Karthikeyan, R.; Singh, Z.; Khangura, R.; Di Gioia, F.; Ahmed, Z.F.R. Enhancing crop resilience by harnessing the synergistic effects of biostimulants against abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1276117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zan, T.; Li, K.; Hu, H.; Yang, T.; Yin, J.; Zhu, Y. Silica nanoparticles promote the germination of salt-stressed pepper seeds and improve growth and yield of field pepper. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.M.; Soliman, M.I.; Abd El-Aziz, M.H.; Abdel-Aziz, H.M.M. Impact of Silica Ions and Nano Silica on Growth and Productivity of Pea Plants under Salinity Stress. Plants 2022, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Mathur, J.; Srivastava, N. Silica nanoparticles as novel sustainable approach for plant growth and crop protection. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Hou, Y.; Chen, L.; Qiu, Y. Advances in silica nanoparticles for agricultural applications and biosynthesis. Adv. Biotechnol. 2025, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hormone | Gene ID | Symbol | Category | Cluster | Log2 Fold Change | Likely Role in Salt-Stress Tolerance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_vs_C | SSI_vs_C | ||||||

| ABA | Glyma.01G225100.1 | HAI2 | ABA_Signaling | C4 | 7.69 | 6.36 | Reduces ABA hypersignaling, contributing to stomatal regulation |

| Glyma.01G018800.1 | PYL12|RCAR6 | ABA_Signaling | C2 | −3.10 | −1.86 | Restores ABA receptor activity, maintaining appropriate signaling | |

| Glyma.07G017300.1 | ABI4 | ABA_Signaling | C2 | −3.74 | −2.21 | Recovery of ABA signaling promotes balanced stress response | |

| Glyma.11G095100.1 | BG2|PR2 | ABA_Biosynthesis | C4 | 5.6 | 4.31 | Suppresses ABA-induced PR proteins, preventing unnecessary defense | |

| Glyma.19G194500.1 | ABF4 | ABA_Signaling | C4 | 3.14 | 1.69 | Attenuates ABA overactivation, preventing growth arrest | |

| Glyma.19G224400.1 | AIT1|NRT1.2 | ABA_Transport | C2 | −3.08 | −1.60 | Restores ABA transport, supporting hormone homeostasis | |

| GA | Glyma.09G183500.1 | PIF1|PIL5 | GA_Signaling | C2 | −3.40 | −2.24 | GA–light crosstalk recovery supports photosynthesis and ROS defense |

| Glyma.10G190200.1 | GAI | GA_Signaling | C4 | 2.2 | 1.91 | Reduces DELLA overactivation, restoring cell elongation | |

| Glyma.13G218200.1 | GA2ox1 | GA_Biosynthesis | C4 | 2.71 | 2.06 | Moderates GA catabolism induction, balancing GA levels | |

| Glyma.16G089000.1 | DXR | GA_Biosynthesis | C2 | −3.64 | −2.26 | Recovers GA biosynthesis, supporting elongation | |

| Glyma.16G200800.3 | GA20ox1|GA5 | GA_Biosynthesis | C2 | −3.19 | −1.94 | Promotes GA biosynthesis, enhancing growth recovery | |

| SA | Glyma.02G023400.1 | TRX5 | SA_Signaling | C2 | −5.03 | −3.05 | Restores redox balance, enhancing ROS detoxification |

| Glyma.02G063500.1 | MES7 | SA_Synthesis | C2 | −2.67 | −1.33 | Recovery of SA homeostasis → maintenance of ABA/ROS crosstalk | |

| Glyma.18G238900.1 | BSMT1 | SA_Synthesis | C4 | 2.86 | 1.75 | Attenuates SA overactivation, stabilizing signaling crosstalk | |

| JA | Glyma.02G142200.1 | DAD1 | JA_Biosynthesis | C2 | −2.62 | −1.40 | Enhances JA-mediated lipid signaling, contributing to ROS defense |

| Glyma.03G159000.1 | DGL | JA_Biosynthesis | C4 | 3.51 | 2.3 | Reduces JA overactivation, saving energy under salt stress | |

| Glyma.13G030300.1 | LOX2 | JA_Biosynthesis | C4 | 2.68 | 1.64 | Suppresses excessive JA/ROS induction, preventing cell damage | |

| CK | Glyma.13G324700.1 | LOG4 | CK_Biosynthesis | C4 | 5.67 | 4.48 | Suppresses CK overactivation, maintaining growth–defense balance |

| Glyma.14G175100.1 | UGT85A1 | CK_Biosynthesis | C2 | −4.60 | −2.19 | Restores cytokinin biosynthesis, enhancing growth | |

| Glyma.20G057500.1 | UGT85A1 | CK_Biosynthesis | C2 | −1.64 | −0.60 | Restores cytokinin biosynthesis, enhancing growth | |

| BR | Glyma.02G256800.1 | CPD|CBB3|DWF3 | BR_Biosynthesis | C2 | −2.55 | −1.08 | Recovers BR biosynthesis, supporting elongation |

| Glyma.03G002900.1 | CDG1 | BR_Signaling | C2 | −2.16 | −0.95 | Restores BR signaling, supporting development | |

| Glyma.11G204700.1 | BRI1|CBB2|DWF2 | BR_Signaling | C2 | −4.31 | −3.15 | Restores BR receptor function, maintaining developmental control | |

| Glyma.13G352800.1 | CDG1 | BR_Signaling | C2 | −3.98 | −2.67 | Recovers BR kinase signaling, regulating growth | |

| AUX | Glyma.03G063900.1 | AUX1 | AUX_Transport | C2 | −3.14 | −1.67 | Restores auxin transport, supporting directional radicle growth |

| Glyma.07G164600.4 | PIN4 | AUX_Transport | C2 | −2.58 | −1.34 | Recovers auxin efflux, enhancing radicle development | |

| Glyma.17G139400.1 | NRT1.1 | AUX_Transport | C2 | −2.74 | −1.22 | Restores nitrate/auxin transport, maintaining growth | |

| ETH | Glyma.07G017300.1 | EREBP|ERF13 | ETH_Signaling | C2 | −3.74 | −2.21 | Recovery of ERF13 supports ROS detoxification and ion homeostasis |

| Glyma.09G008400.1 | ACO1 | ETH_Biosynthesis | C2 | −2.29 | −1.64 | Recovery of ACC oxidase maintains ethylene biosynthesis under salt stress | |

| Glyma.18G059700.1 | ETO1 | ETH_Biosynthesis | C2 | −2.50 | −1.75 | Moderation of ethylene overproduction helps maintain the hormonal balance | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, S.-Y.; Lee, W.-H.; Kang, B.H.; Chowdhury, S.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, H.-S.; Ha, B.-K. Transcriptomic and Physiological Insights into the Role of Nano-Silicon Dioxide in Alleviating Salt Stress During Soybean Germination. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222320

Shin S-Y, Lee W-H, Kang BH, Chowdhury S, Kim D-Y, Lee H-S, Ha B-K. Transcriptomic and Physiological Insights into the Role of Nano-Silicon Dioxide in Alleviating Salt Stress During Soybean Germination. Agriculture. 2025; 15(22):2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222320

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Seo-Young, Won-Ho Lee, Byeong Hee Kang, Sreeparna Chowdhury, Da-Yeon Kim, Hyeon-Seok Lee, and Bo-Keun Ha. 2025. "Transcriptomic and Physiological Insights into the Role of Nano-Silicon Dioxide in Alleviating Salt Stress During Soybean Germination" Agriculture 15, no. 22: 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222320

APA StyleShin, S.-Y., Lee, W.-H., Kang, B. H., Chowdhury, S., Kim, D.-Y., Lee, H.-S., & Ha, B.-K. (2025). Transcriptomic and Physiological Insights into the Role of Nano-Silicon Dioxide in Alleviating Salt Stress During Soybean Germination. Agriculture, 15(22), 2320. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15222320