Abstract

Broiler meat remains an important source of food with immense potential for ending hunger as well as achieving food and nutrition security (SDG 2). We apply the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to time-series data spanning from 2010 to 2021 to ascertain the response of South Africa’s broiler meat supply to changes in imports, exports, and inflation. The results show that broiler supply from local producers is negatively affected by the quantity of broiler meat imported. For every unit increase in broiler meat imports, domestic broiler supply decreases by −0.12% in the long run. However, in the short run, for every 1% increase in the broiler imports, there is an increase of 0.07% in domestic broiler supply. The supply of domestic broiler meat increases by 0.37% for every 1% increase in the consumer price index in the long run, while the unit increase in the consumer price index is associated with a decrease of 2.12 in domestic broiler supply in the short run. In the short run, broiler exports have a positive relationship with domestic broiler supply. A unit increase in broiler exports is associated with a 0.04 increase in the domestic broiler supply. The earlier finding could allow for greater development of the local broiler industry through South Africa’s Poultry Masterplan, by increasing domestic broiler meat supply to discourage imports and to increase broiler exports contributing to the pressing need for job creation and food security, but the latter can exact an inhibiting effect on the accessibility of broiler meat. We concluded that the attainment of SDG 2 in South Africa is possible if policy strikes a balance between food availability and accessibility, particularly when it comes to broiler meat as it is the cheapest source of protein. This could be achieved through increased investment towards expanding domestic broiler production and promoting strategies for reasonable pricing of poultry, while giving priority to consumer health concerns.

1. Introduction

We are now close to a decade since the United Nations (UN) set forth 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) [1], one of which is to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (SDG 2). Despite this, the most recent report on the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the world [2] shows that in 2022, world hunger grew by 122 million more people compared to the previous period. In addition, access to animal sources of food was a huge challenge especially in Africa during the same period. As a result, the investigation of the drivers of broiler meat supply carried out in this study seeks to provide policy insights supportive of resolving food and nutrition insecurity in South Africa.

By the year 2050, the projected annual growth rate is expected to attain 1.8% worldwide and 2.4% in developing nations. Though production will be better as a result of more people eating poultry than other meat, domestic supply is not expected to keep up with demand, with nearly 40% of the extra consumption coming from imports in Sub-Saharan Africa [3]. The demand for poultry products will double due to population growth and socioeconomic shifts, including urbanization, aging demographics, and increasing affluence levels by the same year [4]. Previous research has consistently shown that broiler meat in South Africa remains the cheapest source of protein [5], thus being the most consumed meat [6], and an important contributor to food security [7]. However, the country is not producing enough to meet the local demand for consumption of broiler meat due to the growing competition from imports, which have reduced the return on investment for local producers. For instance, during the first quarter (January-March) of 2023, South Africa imported a total of 122 455 tons of chicken meat compared to 73 590 tons imported in Q4 of 2022, and this represented an increase of 66% [8]. This increase was driven by boneless chicken (other), which rose by 294%, followed by frozen chicken carcasses (53%), frozen chicken thighs (50%), frozen chicken feet (29%), frozen chicken wings (28%), frozen chicken offal (14%), and frozen chicken mechanically deboned meat (MDM) (9%) [8]. It also implies that ongoing monitoring of the drivers of demand and supply in broiler meat is crucial when it comes to the attainment of food security.

The majority of South Africa’s chicken exports go to its neighboring countries, where people generally consume less red meat. Seventy percent of South African chicken meat exports in 2021 went to the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). The main problem for the broiler meat industry in South Africa is its lack of structures established to keep the drivers of supply under surveillance. This has existed for a long time, catching the country off guard and making it less prepared to respond adequately to the threats of food security [9]. This is contrary to the grain sector, as is clear from official bodies such as the crop estimates committee, as well as the supply and demand estimates committee, overseeing the drivers of grain supply for food security. However, since the introduction of the Poultry Masterplan in 2019, this topic has received growing interest, with the National Agricultural Marketing Council launching a Poultry Product Price Monitor, which is published every month. However, the period prior to 2019 is omitted in this report. In addition, it remains generic, with no empirical backing, suggesting that further areas of research still remain with respect to this topic.

Broiler meat, as the cheapest source of protein, can make a meaningful contribution to eradicating poverty, ending hunger and attaining SDG 2. As a nation undergoing urbanization, population growth, and economic transformation, some pressure is being exerted on the poultry industry. To alleviate this pressure, South Africa needs to produce more broilers in order to boost supply and perhaps reduce costs. This would eventually enhance nutrition and food security by making food more accessible and available. This will contribute to the national achievement of SDG 2. According to Tenza et al. [10], backyard-raised hens offer a lot of promise for both consumption and income generation at the family level, particularly for those who are more vulnerable. These tactics will help reach SDG 2, which focuses on ending hunger and guaranteeing that everyone has access to food.

This study examines the effect of imports, exports, and consumer price index, also known as inflation, on domestic broiler supply in South Africa between 2010 and 2021. It applies the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to monthly secondary data acquired from the South African Poultry Association (SAPA) and South Africa Reserve Bank (SARB). The central research question is, “What is the relationship between local broiler supply imports, exports and consumer price index (inflation)?” Furthermore, the following kind of analysis is essential: strategic insights into the implementation of the Poultry Masterplan in South Africa, some answers regarding the recent launch of market investigation by the Competition Commission of South Africa (CCSA) concerning the affairs of the poultry industry, and policy options regarding the availability and accessibility of broiler meat when it comes to the attainment of food security, the SDG 2.

The paper is divided into five sections, of which this is the first. Section 2 deals with methodology, with special emphasis on the study site, variable information, and estimation procedure. The findings of the study are presented in Section 3, followed by discussion in Section 4. The conclusion and list of references are provided in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

2. Literature Review

The economic theory of supply states that, all other things being constant, the amount of goods produced by a firm depends on economic factors such as prices, inputs costs and investment spending, as well as non-economic factors such as technology, population, number of the firm growth patterns of broilers, climate variation, mortality, and disease outbreaks. While both factors are important, of late, considerable emphasis has been placed on the latter (non-economic factors) compared to the former (economic factors). According to Wijesuriya et al. [11], high and fluctuating food cost, particularly for essential food items such as rice, wheat flour, sugar, milk, red meat, and chicken products, can impact significantly on food and nutrition security at the household and national levels. Since South Africa is one of the most unequal societies in the world, these food cost fluctuations can have a serious bearing on those who do not have enough resources. Idowu et al. [12] indicated that, since 2004, there has been a sharp decline in the success of poultry production because of rising production costs, declining consumer income, and consumer demand for imported chicken products in South Africa.

In a study by Mmila [13] on the supply response and elasticities of broilers in South Africa, the results demonstrated a p-value of 0.020, which indicates that a combination of these variables (imports, exports, feed price index and nominal exchange rate) has a substantial short-term impact on the broiler supply. Applying the multiple regression analyses to the household level data in Indonesia, Dewantari et al. [14] found no significant influence of economic factors such as input prices for day-old chicks, feed, and vaccine on the supply of broiler meat. Influential studies around the drivers of supply for broiler meat include Delport et al. [7], who applied the Linear Approximation of an Almost Ideal Demand System (LA/AIDS) on monthly data between January 2008 and September 2014, and Louw et al. [15], who used cross-sectional data from 53 participants in 2011 for both pork and broiler meat in South Africa. The former pays attention to the demand side, while the latter leans on feed supply rather than broiler meat. Although the studies are now old and need to be updated, Taha and Hahn [6] is the only study that lies closer to our topic, and it reports on consumer taste, technology, and market scale as main drivers of import supply for poultry meat. Overall, research on the drivers of supply for broiler meat remains in-exhaustive and inconclusive. This is one of the motivations for our study. Increased domestic production efficiency, destination market income and population growth, exchange rate fluctuations, trade policy and trade disputes, and relative price changes for other meats are some of the factors that have affected the United States (US) exports of broiler meat, according to Davis et al.’s [16] study, which evaluated the growth of US exports of poultry and broiler meat in some key markets in 2013.

A study on import tariff adjustments and broiler domestic production by Nkgadima and Muchopa [17] demonstrates a clear long-term association between domestic broiler output and the number of imported broilers. The amount of broilers produced domestically will rise by 0.036, or 3.6%, for every unit increase in the quantity of broilers imported. There is a wealth of theoretical and empirical data that clarifies how exports contribute to a nation’s economic development and progress. International trade is the main driver of economic growth, according to prominent classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who also stress the need for specialization in achieving higher economic gains [18]. While exporting agricultural goods might result in some financial benefits, there are some obstacles to overcome. Maize and soybeans are the two most variable feed ingredients used in South African broiler production, and producers also deal with fluctuating feed costs. A changing South African exchange rate adds even more volatility to overall feed costs. Thus, South Africa is not performing well internationally and is finding it difficult to maintain its competitiveness due to persistent feed prices on profit. Secondly, producing broiler meat for international markets in a competitive way requires excellent administrative and technological skills [19]. While food safety standards, traceability, product certification, environmental standards, and other regulations are growing in scope and importance as international food trade opens up, traditional trade barriers like tariffs are gradually being reduced within the World Trade Organization (WTO). However, it is unclear how these rules and guidelines affect developing nations [20]. Regulating access is, regrettably, the first significant obstacle. To assist broiler producers in meeting various regulatory requirements of many nations, the South African Department of Agriculture must be more proactive and adaptable. For example, just three domestic poultry factories have been examined and licensed for export to the Middle East by the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment (MOCCAE) in the United Arab Emirates, although a large portion of the market is available for South African imports [21].

The production of broilers dominates the agricultural industry, as it is the cheapest primary source of animal protein, with beef coming second. Given that demand for broilers exceeds supply, South Africa is referred to as a net importer of broiler meat. Concerns have also been expressed by the South African poultry industry over a large number of low-cost broiler imports into the country’s market. In addition, most broiler meat exports only reach South Africa’s neighboring countries, with few quantities leaving the continent. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the short- and long-term effects of changes in the local broiler supply on imports, exports, and the consumer price index. Policy clarity on changes in imports, exports, and the consumer price index, as well as how the local broiler supply responds to these changes, is aided by an understanding of the dynamic link between these factors. A few studies have been conducted to evaluate the dynamic link between supply, imports, exports, and the consumer price index, specifically with regards to broiler meat, based on the reviewed literature. The study’s conclusions will add to the body of knowledge about the dynamics of the local broiler supply and how they relate to reaching SDG 2, which seeks to eradicate hunger.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Information

The study was conducted in South Africa, which is in the southern part of the African continent, and it is known for its diverse landscape and favorable climate. South Africa borders Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. The broiler industry is considered the largest sub-sector of agriculture in South Africa. It grew a total of 1.11 billion broilers using 3.44 million tons of feed, resulting in 22 million slaughterings or ZAR 59 billion in terms of gross value of production in 2022. This production came from nine provinces in the country, with North-West leading at 24%, followed by Mpumalanga (22%), Western Cape (13%), Free State (12%) and Gauteng (11%). However, the study employed national-level time-series data of broiler producers in South Africa, spanning from 2010 to 2021. Much of this data is readily available from the official website of the South African Poultry Association (SAPA). Its collection and availability are made possible through the provisions of the Marketing of Agricultural Products Act, No. 47 of 1996 (MAP Act). This act allows an industry to impose a statutory levy described as a charge per unit of an agricultural commodity at any point in the marketing chain between the producer and the consumer. The levy is collected for specific functions, such as funding for research, information, and transformation.

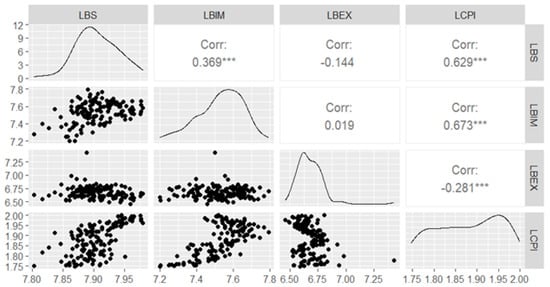

Based on SDG 2 and the focus of the study at the national level, we selected four variables for our analysis, and their descriptive summary is presented in Table 1. The selection of variables for this study was informed by Nkgadima and Muchopa [17]. Supply (LBS) refers to quantities of broiler meat provided for South African consumers. Imports (LBIM) are quantities of broiler meat bought from other countries. Exports (LBEX) are quantities of broiler meat sold to other countries. Inflation is the rate of increase in prices over a given period. This is monthly data from 2010 to 2021, and there are no missing values in the data. All variables are logarithmically transformed. Lbs is the dependent variable, while lbim, lbex and lcpi are independent variables. The p-values indicate a significant difference between these variables. Further details concerning the density-scatter plots and correlations are presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summary of selected variables for the study, 2010–2021.

Figure 1.

The data visualization of variables for the study, 2010-2021. Note: Mean (SD), *** p ≤ 0.001.

3.2. Estimation Procedure

The study was designed to investigate the relationship between three independent variables (broiler imports, broiler exports and inflation) and one dependent variable (broiler supply). Based on Nkoro and Uko [22], and Kadir and Tunggal [23], the Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique with error correction (ECM) model became the most suitable method to attain our research goal. It was applied by Reham et al. [24] in the analysis of selected meat products in Pakistan. Also, Hadi et al. [25] employed ARDL in the meat industry. Using the variables described in the previous section, along with their notation in Table 1, the ARDL model for our study can be expressed as follows:

where l represents logged variable; lbs represent log of domestic broiler supply; lbim denotes log of broiler imports; lbex is the log of broiler exports; lcpi indicates the consumer price index.

Long-term relationship estimation: For long-term estimations when cointegration between the variables has been established. The ARDL model may be described as follows:

However, Equation (1) can be transformed into the Error Correction Model to integrate short- and long-run relationships among the variables of our consideration, where is an error correction term and ▵ represents a differenced variable.

In this equation, is the constant, is the speed of change, and is the error term. The model was estimated using EViews 13, and the results are presented in the next section.

4. Results

4.1. Diagnostic Tests

Table 2 presents the results of various diagnostic tests performed over the study period. The results of the Augmented Dickey Fuller Test depicted in column A show that the null hypothesis stating that variables are non-stationary is rejected at level (except for LBEX). However, the opposite is also true when the series is tested at the first difference for all variables. The latter findings are also observed in the Phillips Perron Test displayed in column B of the same table. A similar study was conducted by Nkgadima and Muchopa [17], where the evaluation was performed to check the sensitivity of broiler domestic production and import volumes to changes. The results of the unit root test from their study do not agree with this study, particularly on the unit root test, as this study has a combination of I (0) and I (1), and in their study, all the variables were integrated at I (1).

Table 2.

Summary of diagnostic test results of selected variables.

4.2. ARDL Cointegration Test

The two-step Engle–Granger method is the single-equation technique for cointegration that is most often recognized. Some drawbacks have led to widespread criticism of this strategy. Firstly, when calculating the cointegrating vector, short-run dynamics are disregarded. Secondly, in finite samples, complicated short-run dynamics frequently introduce bias into the estimation of the long-run connection [26]. The Autoregressive Distributed Lag, or bound test, is an alternative cointegration method that Pesaran et al. [27] devised to overcome these problems. There are many advantages of ARDL over traditional Johansen cointegration methods that have been suggested. Firstly, the Johansen cointegration approaches require large data samples for validity, but the ARDL is a more statistically significant method of identifying cointegrating correlations in small samples. In this study, the ARDL cointegration approach was chosen as the model because these variables were integrated into several orders, combining I (0) and I (1) order. The study used the bounds test approach to examine if variables collectively exhibit a long-run relationship (see Table 3). The model’s computed F-statistics, which are higher than the crucial values at all levels of significance, imply that the null hypothesis that there is no long-term relationship cannot be accepted. The short- and long-term dynamics between the variables are calculated because the study discovered a long-term link between the variables. The model’s computed F-statistics, which are higher than the crucial values at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels of significance, imply that the null hypothesis that there is no long-term relationship cannot be accepted. Given that the investigation discovered a long-term association, estimates are made of the variables’ short- and long-term dynamics. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), the Hannan–Quinn (HQ) and the Final Prediction Error (FPE) can be applied to determine the lag order in the test equation.

Table 3.

The results of ARDL Bound Test.

4.3. Short- and Long-Run Estimates

Table 4 presents the short- and long-run estimates for our model. As shown in the table, broiler imports and consumer price index have a significant impact on the domestic supply of broiler meat in the short run over the study period. This suggests that a unit increase in broiler imports is associated with a 0.12% decrease in domestic broiler supply. On the other hand, a unit increase in the consumer price index leads to a 0.37% increase in domestic broiler supply. The coefficient for variable COINTEQ* suggests that the domestic broiler supply responds moderately to variations in broiler imports, exports, and consumer price index during the short run. In other words, 46% of disequilibrium for the industry is fixed during the first month. Over the same period (short run), we also found that the three variables are significant at the 5% conventional level. For instance, a one per cent increase in the broiler meat imports leads to a 0.07% increase in the domestic supply of broiler meat in the first month, followed by 0.08% in the second. A 1% increase in the broiler exports yields a 0.04% increase in the domestic broiler supply in the first and second months. However, there was a significant negative correlation between domestic broiler supply and consumer price index. The results indicate that a one per cent increase in the consumer price index is associated with a 2.12% decline in the broiler supply. Finally, the adjusted R-squared indicates that 64% variation in the domestic broiler meat supply is explained by broiler imports, exports and consumer price index.

Table 4.

The results of ARDL long- and short-run estimates.

4.4. Estimates for Stability

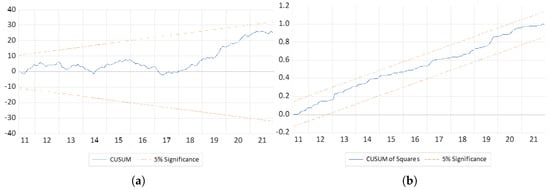

The CUSUM test and CUSUM of squares test were used in the study to test the stability of coefficients. The Figure 2 below indicates that the model is stable, as the residual fluctuates within the 5% bound. This suggests that the parameters of our model were appropriately defined and that the outcomes we acquired are trustworthy for formulating policy suggestions.

Figure 2.

The depiction of CUSUM findings for the study—(a) CUSUM test. (b) CUSUM of squares test.

5. Discussion

The study was designed to evaluate the response of supply variables for broiler meat in South Africa with special emphasis on implications for the attainment of SDG 2. With an adjustment speed of 47%, the model appears to be stable and self-correcting each month when there is a deviation from long-term equilibrium. Domestic broiler supply is responsive to changes in imports, exports and consumer price index. The coefficient of determination (r-squared) is 0.64, indicating that the stochastic disturbance element is responsible for around 36.% of the fluctuation in the broiler supply, while all other explanatory factors account for 64% of the variation. We found that boosting the local industry is associated with a decrease in broiler meat imports for the country in the long run. If domestic broiler supply does not rise quickly over time, the industry will become vulnerable to imports, and this would eventually oversaturate the market and deter local broiler meat supply. This is supported by Davids et al. [28] on the analysis of the impact of planned tariff protection on the South African broiler sector. In addition, the findings support previous research [29]. Assuming no constraints around accessibility, more availability of broiler meat could also serve as a food security strategy aimed at alleviating protein malnutrition [30] in the country. This expected finding suggests that resources should be prioritized towards the implementation of the Poultry Masterplan for the realization of food security. Such efforts are also likely to unlock job creation, thus contributing to economic growth. Another interesting finding is that the international demand for broiler meat can stimulate local production of broiler meat in the short run, thus leading to an increase in broiler exports. Importing broiler meat has a short-term direct impact on local supply because of heightened societal knowledge of the value of broilers, which might lead to a rise in the demand for meat in the economy. Therefore, the growing demand for domestic broilers may incentivize local producers to raise their supply. This result is consistent with research by Kwakwa [31] on Ghanaian rural residents’ preferences for local broiler meat over imports. The survey indicates that local chicken meat is preferred to imported chicken meat because of its quality (safety), patriotism, taste, and tenderness. The choice is also influenced by the participant’s age, marital status, and number of children. This corresponds with Valdes et al. [32], who reported that broiler exports are associated with increased broiler meat supply for international markets. Nonetheless, the import–export activity suggests that international trade plays a huge role in broiler meat supply for South Africa. For instance, the country imported 87 771 tons of chicken meat at the tail end of 2023 [8]. This consisted of whole frozen chicken (9.94%), followed by boneless chicken breasts (395%), frozen chicken carcasses (126%), frozen chicken feet (33%) and frozen chicken leg quarters (29%). According to DALRRD [33], broiler meat exports were estimated at 51,000 tons. While growing the local industry, policymakers must be careful not to introduce interventions that will impede or distort competition in both domestic and international markets. Most importantly, the study demonstrated that boosting agricultural productivity for the broiler industry in South Africa can result in a reduced consumer price index, as supported by Wiebe et al. [34]. This would redress food inaccessibility, which remains a long-standing challenge for the majority of food consumers in the country. This is a critical subject for future research, thus the necessity for a continuing inquiry into the contribution of the industry’s productivity growth to changes in broiler meat prices.

6. Conclusions

The aim of the study was to explore the drivers of broiler meat supply in South Africa for the attainment of SDG 2 using the Autoregressive Distributed Lag model between 2010 and 2021. Time series data were acquired from official websites for the South African Poultry Association and South African Reserve Bank. After performing a series of diagnostic tests, the broiler imports, exports, and consumer price index emerged as reliable predictors of the country’s broiler meat supply. Overall, the results show that SDG 2 can be attained through the adoption of import substitution industrialization policy aimed at strengthening local production to reduce broiler imports in the long run. This has an immediate contribution to SDG 2 in terms of food availability. In addition, it exacts an inhibiting effect on broiler meat price inflation, evident from a significant negative correlation between domestic broiler meat supply and consumer price index in the short run. This latter finding contributes to the attainment of SDG 2 in terms of food accessibility. Broiler meat is rich in protein, which implies that its availability and accessibility can ensure the attainment of SDG in terms of food nutrition (utilization). A key policy priority should therefore be prioritizing and channelling more support on the implementation of the Poultry Masterplan because the findings resonate specifically with pillars 1 (expanding and improving local production), 2 (driving domestic demand) and 5 (trade measures to support the local industry) in this plan. The scope of this study was limited to the national level, which implies that it did not deal with the attainment of SDG 2 at the household level. Thus, future studies can address this gap by investigating the attainment of SDG 2 in terms of food stability, as well as the contribution of industry’s productivity growth to changes in broiler meat prices. Although the study has demonstrated notable findings that call for new policy interventions, it has limitations in terms of exploring cost comparative analysis in poultry production in different countries; thus, future studies should focus on addressing this unique gap.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.; Literature, G.M.; methodology, G.M.; Data curation, G.M.; formal analysis, G.M.; review and editing, L.W.M.; Sourcing publication fee, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing fee for this research was received from Higher Degrees Committee and Food Security and Safety niche area within University of North West.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the lead author, G Mmila.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which have improved the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAPA | South African Poultry Association |

| SARB | South African Reserve Bank |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lags |

References

- Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food security and the 2015–2030 sustainable development goals: From human to planetary health. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e000513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: 2023: Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum; Technical Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/445c9d27-b396-4126-96c9-50b335364d01 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Mottet, A.; Tempio, G. Global poultry production: Current state and future outlook and challenges. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleyn, F.; Ciacciariello, M. Future demands of the poultry industry: Will we meet our commitments sustainably in developed and developing economies? World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queenan, K.; Cuevas, S.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, M.; Slotow, R.; Häsler, B. A Qualitative Analysis of the Commercial Broiler System, and the Links to Consumers’ Nutrition and Health, and to Environmental Sustainability: A South African Case Study. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 650469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, F.A.; Hahn, W.F. Factors driving South African poultry and meat imports. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Delport, M.; Louw, M.; Davids, T.; Vermeulen, H.; Meyer, F. Evaluating the demand for meat in South Africa: An econometric estimation of short term demand elasticities. Agrekon 2017, 56, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NAMC. South African Poultry Products Price Monitor; Technical Report; Markets and Economic Research Center Division: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- SAPA. Industryb Profile: South African Poultry Association; Technical Report; Information Services: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tenza, T.; Mhlongo, L.C.; Ncobela, C.N.; Rani, Z. Village Chickens for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 2 in Resource-Poor Communities: A Literature Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesuriya, W.; Lokuge, L.; Wickramarachchi, A.; Udugama, J.; Herath, H.; Edirisinghe, J.; Jayasinghe-Mudalige, U. An Analysis of Price Behavior of Major Poultry Products in Sri Lanka. J. Agric. Sci. Sri Lanka 2017, 12, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu, P.A.; Zishiri, O.; Nephawe, K.A.; Mtileni, B. Current status and intervention of South Africa chicken production—A review. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmila, G. Estimation of Supply Response and Elasticities of Broiler Meat in South Africa. Master’s Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dewantari, R.Y.; Suparta, N.; Putri, B.R.T. Analysis of supply and demand of broiler chicken meat in Bali province. Agric.-Socio-Econ. J. 2023, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Schoeman, J.; Geyser, M. Pork and broiler industry supply chain study with emphasis on feed and feed-related issues. J. Agric. Econ. Dev. 2013, 2, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C.G.; Harvey, D.; Zahniser, S.; Gale, F.; Liefert, W. Assessing the Growth of US Broiler and Poultry Meat Exports; A Report from the Economic Research Service; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; pp. 1–28.

- Nkgadima, K.; Muchopa, C.L. Do import tariff adjustments bolster domestic production? Analysis of the South African-Brazilian poultry market case. Economies 2022, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, B. An empirical analysis of agricultural exports on economic growth in India. Econ. Aff. 2019, 64, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joubert, J.C.N. A Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of the South African Broiler Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grote, U.; Frohberg, K.; Winter, E.M. EU Food Safety Standards, Traceability and Other Regulations: A Growing Trade Barrier to Developing Countries’ Exports? In Proceedings of the International Association of Agricultural Economists Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 12–18 August 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Movement, F. Why South Africa’s Poultry Exports Have Not Taken Off; Technical Report; Fairplay Movement: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nkoro, E.; Uko, A.K. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: Application and interpretation. J. Stat. Econom. Methods 2016, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kadir, S.; Tunggal, N.Z. The impact of macroeconomic variables toward agricultural productivity in Malaysia. South East Asia J. Contemp. Bus. Econ. Law 2015, 8, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Deyuan, Z.; Chandio, A.A. Contribution of beef, mutton, and poultry meat production to the agricultural gross domestic product of Pakistan using an autoregressive distributed lag bounds testing approach. Sage Open 2019, 9, 2158244019877196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, S.N.; Chung, R.H. Estimation of demand for beef imports in Indonesia: An autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogazi, C.G. Rice output supply response to the changes in real prices in Nigeria: An autoregressive distributed lag model approach. J. Sustain. Dev. Afr. 2009, 11, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Shin, Y.; Smith, R.J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J. Appl. Econom. 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, P.; Meyer, F.H.; Louw, M. Evaluating the effect of proposed tariff protection for the South African broiler industry. Agrekon 2015, 54, 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Can. D’agroecon. 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, R.; Acosta, A. Assessing livestock total factor productivity: A Malmquist Index approach. Afr. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2018, 13, 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Kwakwa, P.A. Local or imported chicken meat: Which is the preference of rural Ghanaians? Int. J. Mark. Bus. Commun. 2013, 2, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Valdes, C.; Hallahan, C.; Harvey, D. Brazil’s broiler industry: Increasing efficiency and trade. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 263–275. [Google Scholar]

- DALRRD. A Profile of the South African Broiler Market Value Chain; Technical Report; Directorate Marketing: Pretoria, South Africa, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe, K.; Sulser, T.B.; Dunston, S.; Rosegrant, M.W.; Fuglie, K.; Willenbockel, D.; Nelson, G.C. Modeling impacts of faster productivity growth to inform the CGIAR initiative on Crops to End Hunger. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).